Abstract

A case of Fasciola gigantica-induced biliary obstruction and cholestasis is reported in Turkey. The patient was a 37- year-old woman, and suffered from icterus, ascites, and pain in her right upper abdominal region. A total of 7 living adult flukes were recovered during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). A single dose of triclabendazole was administered to treat possible remaining worms. She was living in a village of southeast of Anatolia region and had sheeps and cows. She had the history of eating lettuce, mallow, dill, and parsley without washing. This is the first case of fascioliasis which was treated via endoscopic biliary extraction during ERCP in Turkey.

Keywords: Fasciola gigantica, fascioliasis, bile duct, Turkey

INTRODUCTION

Fascioliasis is caused by trematodes belonging to the genus Fasciola (F. hepatica and F. gigantica) [1,2]. Its infection is known to cause bile duct inflammation and biliary obstruction [3,4]. Infection with Fasciola spp. occurs when metacercariae are accidentally ingested through raw vegetation. The metacercariae exist in the small intestine, and move through the intestinal wall and peritoneal cavity to the liver where adults mature in the biliary ducts of the liver. The acute phase is characterized by migration of immature worms through the liver. Clinical symptoms are related to hemorrhage and inflammation, and are usually severe, including fever, abdominal pain, respiratory disturbances, and skin rashes. The chronic phase starts when the worms reach the bile ducts. Symptoms are non-specific and usually mild to moderate [5].

We present here a case of F. gigantica-induced biliary obstruction and cholestasis that was diagnosed and treated via endoscopy and triclabendazole treatment. This is the first case which was treated via endoscopic biliary extraction during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and drug in Turkey.

CASE REPORT

In January 2010, a 37-year-old woman complained of icterus, ascites, and pain in her right upper abdominal region. She was living in a village of southeast of Anatolia region, and she had sheeps and cows. She had the eating history of lettuce, mallow, dill, and parsley without washing. She had no history of using hepatotoxic drugs. On admission to our department, her temperature was 37.9℃, and she had icterus, hepatomegaly, and ascites. Over the 3-month period, her weight dropped from 70 kg to 58 kg. Laboratory findings revealed an increase in leukocytes, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and bilirubin levels. CT scans revealed reticular patterns at all segments of the liver parenchyme, and in affinity with each other about 6 cm in greatest diameter, lobulated contours in multiple views with some cystic lesions were de-tected. After contrast agent injection, mild peripheral enhancement of the lesions were seen in the majority (abscess-phleg-mon was considered). She had yellow color ascites and splenomegaly. ERCP was addressed at F. gigantica because of their different appearance. Her eosinophilia was about 26.4%. The IgE level was 1,170 IU/ml (normal: 0-350 IU/ml). The serum collected when the fluke emerged yielded a titer of 1:20,480 by a standard ELISA protocol (reference: <1,160). In the ascites, serum ascites albumine gradient (SAAG) was under 1.1. We applied ERCP procedure to the patient. We removed 7 live F. gigantica worms during the ERCP (Fig. 1). On the basis of its morphology and shape, the fluke was diagnosed as F. gigantica, and a portion was kept in 70% ethanol (Fig. 2). The eggs of F. gigantica are seen in Fig. 3. A single dose of triclabendazole (3 tablets, oral) was administered. After these therapy, clinical symptoms disappeared and the patient remained completely healthy.

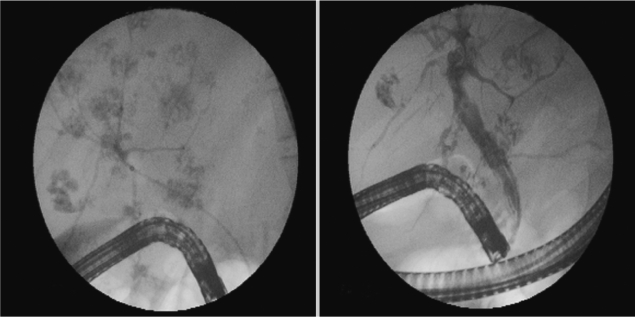

Fig. 1.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) findings of the patient, footprints of parasites.

Fig. 2.

Fasciola gigantica (A, alcohol-fixed worms; B, a whole worm) recovered during ERCP of the patient.

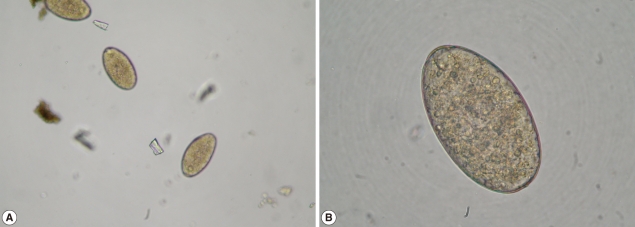

Fig. 3.

Low (A, ×100) and dry high power (B, ×400) views of F. gigantica eggs.

DISCUSSION

F. gigantica is a parasitic flatworm of the class Trematoda, which causes tropical fascioliasis. It is regarded as one of the most important single platyhelminth infections of ruminants in Asia and Africa. Estimates of infection rates are as high as 80-100% in some countries [1-5]. Despite the importance to differentiate between the infection by fasciolid species, due to their distinct epidemiological, pathological, and control characteristics, there is, unfortunately, neither a direct coprological (excretion-related) nor an indirect immunological test is available for their diagnosis [6,7]. The quantification of the different sizes and shapes of F. hepatica and F. gigantica from bovines has been achieved for the first time in natural allopatric populations [8]. Linear measurements, areas and ratios of gravid adults and eggs of F. hepatica (from France and Spain) and F. gigantica (from Burkina Faso) can be analyzed using a com-puter image analysis system and an allometric model: (y2m-y2)/y2=c[(y1m-y1)/y1](b), where y1=body area or body length, y2=one of the measurements analyzed, y1m, y2m=maximum values towards which y1 and y2, respectively, and c, b=constants [8]. All the measurements overlap in the 2 fasciolids, apart from the distance between the ventral sucker and the posterior end of the body, body roundness, and body length/body width ratio. This method is useful for Fasciola species identification in countries where both species coexist. In trematodiases, size and shape of the fluke eggs shed with feces are crucial diagnostic features because of their typically little intraspecific variability. In fascioliasis, the usual diagnosis during the biliary stage of infection is based on the classification of eggs found in the stool, duodenal content, or bile [9]. According to these studies we can say that our case is a F. gigantica infection.

The specific differentiation of trematodiases in general can be made by either a morphological study of adult flukes or by molecular tools. In the case of liver fluke infections, cholangiograms are useful, and biliary fascioliasis is characterized by nonspecific biliary dilatation and single or multiple small filling defects, which represent flukes themselves. However, the conclusive diagnosis of biliary facioliasis can be made by direct identification of flukes obtained from endoscopic or surgical removal, or detection of typical eggs in bile from the duodenal tube.

Symptoms of the hepatic phase, which begin about 1 month after the exposure to metacercariae, are fever, general malaise, fatigue, hepatomegaly, anorexia, weight loss, urticaria with dermatographism, and peripheral blood eosinophilia. The symptoms may be absent in the case of light infections. The biliary phase may be asymptomatic or there may be symptoms related to cholangitis and obstruction of the biliary tract due to the enlarging flukes. The biliary phase may last for months or years. Peripheral blood eosinophilia during this interval suggests hepatobiliary fascioliases [10].

Parasite removal during ERCP is a therapeutic option in patients with acute obstructive cholangitis due to F. gigantica [11]. Triclabendazole at a single dose of 10 mg/kg is the chemotherapeutic regimen of choice against fascioliasis [12]. The drug is active against both immature and adult parasites, with high cure rates. Our case had chronic and hepatobiliary phase of fascioliasis. ERCP findings of parasites was very interesting (such as foodprints of parasites) (Fig. 1). We think this is a highly specific appearance for fascioliasis. The present F. gigantica patient is the first case which was treated via endoscopic biliary extraction during ERCP and drug in Turkey.

References

- 1.Soliman MF. Epidemiological review of human and animal fascioliasis in Egypt. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2008;2:182–189. doi: 10.3855/jidc.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mas-Coma S, Bargues MD, Valero MA. Fascioliasis and other plant-borne trematode zoonoses. Int J Parasitol. 2005;35:1255–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dias LM, Silva R, Viana HL, Palhinhas M, Viana RL. Biliary fascioliasis: diagnosis, treatment and follow-up by ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;43:616–620. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(96)70203-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haseeb AN, el-Shazly AM, Arafa MA, Morsy AT. A review on fascioliasis in Egypt. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 2002;32:317–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rana SS, Bhasin DK, Nanda M, Singh K. Parasitic infestations of the biliary tract. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2007;9:156–164. doi: 10.1007/s11894-007-0011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anuracpreeda P, Wanichanon C, Chawengkirtikul R, Chaithirayanon K, Sobhon P. Fasciola gigantica: immunodiagnosis of fasciolosis by detection of circulating 28.5 kDa tegumental antigen. Exp Parasitol. 2009;123:334–340. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2009.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chunchob S, Grams R, Viyanant V, Smooker PM, Vichasri-Grams S. Comparative analysis of two fatty acid binding proteins from Fasciola gigantica. Parasitology. 2010;137:1805–1817. doi: 10.1017/S003118201000079X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Periago MV, Valero MA, Panova M, Mas-Coma S. Phenotypic comparison of allopatric populations of Fasciola hepatica and Fasciola gigantica from European and African bovines using a computer image analysis system (CIAS) Parasitol Res. 2006;99:368–378. doi: 10.1007/s00436-006-0174-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valero MA, Perez-Crespo I, Periago MV, Khoubbane M, Mas-Coma S. Fluke egg characteristics for the diagnosis of human and animal fascioliasis by Fasciola hepatica and F. gigantica. Acta Trop. 2009;111:150–159. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kanoksil W, Wattanatranon D, Wilasrusmee C, Mingphruedh S, Bunyaratvej S. Endoscopic removal of one live biliary Fasciola gigantica. J Med Assoc Thai. 2006;89:2150–2154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwacha H, Keuchel M, Gagesch G, Hagenmüller F. Fasciola gigantica in the common bile duct: diagnosis by ERCP. Endoscopy. 1996;28:323. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1005465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khandelwal N, Shaw J, Jain MK. Biliary parasites: diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2008;11:85–95. doi: 10.1007/s11938-008-0020-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]