Abstract

Arterial smooth muscle cells enter the cell cycle and proliferate in conditions of disease and injury, leading to adverse vessel remodeling. In the pulmonary vasculature, diverse stimuli cause proliferation of pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (PASMCs), pulmonary artery remodeling, and the clinical condition of pulmonary hypertension associated with significant health consequences. PASMC proliferation requires extracellular Ca2+ influx that is intimately linked with intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis. Among the primary sources of Ca2+ influx in PASMCs is the low-voltage-activated family of T-type Ca2+ channels; however, up to now, mechanisms for the action of T-type channels in vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation have not been addressed. The Cav3.1 T-type Ca2+ channel mRNA is upregulated in cultured PASMCs stimulated to proliferate with insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I), and this upregulation depends on phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling. Multiple stimuli that trigger an acute rise in intracellular Ca2+ in PASMCs, including IGF-I, also require the expression of Cav3.1 Ca2+ channels for their action. IGF-I also led to cell cycle initiation and proliferation of PASMCs, and, when expression of the Cav3.1 Ca2+ channel was knocked down by RNA interference, so were the expression and activation of cyclin D, which are necessary steps for cell cycle progression. These results confirm the importance of T-type Ca2+ channels in proper progression of the cell cycle in PASMCs stimulated to proliferate by IGF-I and suggest that Ca2+ entry through Cav3.1 T-type channels in particular interacts with Ca2+-dependent steps of the mitogenic signaling cascade as a central component of vascular remodeling in disease.

Keywords: channel, insulin-like growth factor-I

intracellular calcium plays a key role in specialized functions of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), ranging from the regulation of gene expression to the maintenance of vascular tone. Voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (Cav) are a primary source of calcium influx in VSMC; however, the precise roles of the different classes of Ca2+ channels have not been fully defined. The voltage-activated L- and T-type calcium channels are present in numerous VSMC preparations, and, whereas the high-voltage-activated L-type channels are an established target for antihypertensive agents, the functional role of T-type Ca2+ channels is largely unknown. In the cardiovascular system, two T-type Ca2+ channels are present referred to as Cav3.1 and Cav3.2 (26). Although T-type channels may have a minimal contribution in normal VSMCs, it is becoming increasingly clear that this novel class of Ca2+ channels is regulated in pathological conditions in the heart and vascular system (5, 16, 18, 20, 23, 24, 33).

Previously, T-type Ca2+ channels were identified in pulmonary arteries and pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell (PASMC) preparations (30), where the Cav3.1 channel was shown to influence PASMC proliferation in culture, and the same study implicated Cav3.1 channels in cell cycle progression. Early studies measuring low-voltage-activated (LVA) T-type Ca2+ currents from developing mouse oocytes (10) or sea urchin embryos (9) also suggested that these channels are uniquely involved in cell cycle progression. Similar observations were made in myocytes from newborn ventricular muscle (14) and VSMCs cultured from rat aorta (21). Additional studies in cultured VSMCs have confirmed that cell cycle progression and proliferation require calcium influx through multiple mechanisms that are not yet fully understood (2).

The proliferation of PASMCs is a key factor in the pathogenesis of diseases that involve vessel remodeling, such as pulmonary hypertension. In pathological conditions, growth factors, cytokines, and chemokines signal PASMC apoptosis, migration, and proliferation (15). Insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) is one such factor produced both in vascular endothelial cells and VSMCs, where, via interactions with its receptor or IGF binding protein, it activates multiple signal transduction pathways. IGF-I has been implicated in the development of atherosclerotic lesions via its effects on VSMC proliferation and migration (11), and beneficial effects of IGF-I inhibitors have been observed in animal models of vascular restenosis (37). In addition, IGF-I is a known cell cycle regulator in diverse cell types, and its effects are mediated by signal transduction, primarily via phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt or mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways.

Because of the putative role of T-type Ca2+ channels in cell cycle and cell proliferation and the importance of understanding the underlying mechanisms of PASMC proliferation in diseases that involve vessel remodeling, we investigated the regulation of T-type Ca2+ channels in cultured PASMCs stimulated to proliferate with IGF-I. IGF-I leads to increased levels of the Cav3.1 T-type channel mRNA that are largely influenced by the PI3K/Akt signal transduction pathway. Moreover, RNA interference studies showed that cell cycle stimulation, as evidenced by indexes of PASMC proliferation and the production and activation of cyclins, is dependent on the expression of Cav3.1 Ca2+ channels. Acutely stimulated rises in intracellular Ca2+ by membrane depolarization, angiotensin II (ANG II), or IGF-I were also dependent on the expression of Cav3.1 channels. These results suggest that, in PASMCs, T-type Ca2+ channel expression could be upregulated in pathological conditions and play a regulatory role in pulmonary artery remodeling and pulmonary hypertension.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

IGF-I was purchased either from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN) or Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA); ANG II was from Tocris (Ellisville, MO); and inhibitors PD-98059 and LY-294002 were from Ascent Scientific (Princeton, NJ). Constitutively active (caMEK1) and dominant-negative MAPK/ERK kinase (MEK1) (3) and Akt adenoviruses were provided by Dr. Jody Martin, and fura-2 AM was from Invitrogen/Molecular Probes.

PASMC culture.

PASMCs were prepared from pulmonary arteries of young adult Sprague-Dawley rats. Animals were anesthetized, and the heart and lung were removed and kept in low-calcium physiological saline solution on ice. Intralobular arterioles (3rd and 4th branches) were dissected, cleaned of adventitia, and enzymatically dissociated in two steps: one incubation in 1 mg/ml collagenase D (Roche) to remove the remaining adventitia and endothelial cells, followed by a second digestion with 2 mg/ml collagenase and 0.5 mg/ml elastase (Roche) for 60 min, 37°C. Arteries were mechanically triturated with a polished Pasteur pipette, centrifuged, and suspended in smooth muscle cell basal medium (Lonza). After 3–5 days, the medium was changed to 0.1% serum to eliminate fibroblasts, and after 3 days serum was added back. When confluent, the cells were passaged and expanded for freezing. Upon thawing, PASMCs were used for experiments from passage 3 to 9.

RNA interference.

A 29-nucleotide target for short hairpin RNA (shRNA) knockdown of the rat Cav3.1 T-type Ca2+ channel was identified (5′-TGCTTGTCTACGGTCCCTTTGGCTACATT-3′) and incorporated into complementary shRNA oligonucleotides (Integrated DNA Technologies), which were cloned into RNAi-Ready pSIREN-DNR-DsRed-Express shuttle vector, and the recombinant shuttle vector was then used to construct the “AdX-Cav3.1sh” adenovirus using the Knockout Adenoviral RNAi System 2 (BD Clontech). Adenoviral stocks were amplified in human embryonic kidney-293 cells, and lysates were purified on cesium chloride gradients. Purified adenovirus was used to infect PASMCs with a multiplicity of infection of 100, which resulted in >90% infection.

Real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction.

Quantitative real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was used to quantify mRNA expression in PASMCs. Following various treatments, DNase-free RNA was prepared using RNeasy Mini Kit, according to the manufacturer's protocol (Qiagen), and 1 μg was used for cDNA synthesized using iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (BioRad). cDNA was used as a template for PCR in a reaction containing SYBR Green Master Mix (Fermentas) and 10 μM of each primer, on a 7300 Sequence Detection System (ABI). Relative quantification was done according to the ΔΔCt (comparative threshold cycle) method, where input was normalized to 18s rRNA. Statistical analyses were carried out based on dCt values using Student's t-test as specified. Primer pairs were synthesized (Integrated DNA Technologies) (rat Cav3.1: 5′-CTGTGACCAGGAGTCCACCT-3′; 5′-TGGGGGCTGAGCGTCTTCAT-3′; rat Cav3.2: 5′-GGAACTATGTGCTCTTCAACCTGC-3′; 5′-ATACATCTTCATCTCTGTGGCTCG-3′). Primer assays for 18s RNA, IGF receptor, cyclin D1, cyclin E1, and cyclin A2 were purchased from SA Biosciences.

Immunostaining.

PASMCs were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100, and blocked with 1% normal goat serum before incubation with primary antibodies: anti-Cav3.1 polyclonal antiserum (Bethyl Laboratories) or anti-bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) (Invitrogen) or α-smooth muscle actin SM-22 (Sigma). Secondary antibody was labeled with Alexa Fluor 488 or Alexa Fluor 568 (Invitrogen), and coverslips were mounted using ProLong Gold antifade reagent with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Invitrogen) for nuclear counterstain. To quantify staining for Cav3.1, fluorescence intensity measurements were done using Image J software.

Intracellular calcium measurements.

PASMCs were plated on 15-mm glass coverslips coated with gelatin and loaded with 4 μM fura-2 AM (Invitrogen), for 30 min at 37°C in 0.1% BSA Krebs solution (in mM: 135 NaCl, 5.9 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 10 d-glucose, pH 7.4), followed by 30 min of unloading in the same solution, which allows the hydrolysis of AM group. After unloading, cells are mounted in a microscope chamber and perfused with Krebs solution at room temperature at 1 ml/min. Cells are visualized with a Nikon inverted microscope, excitation wavelength is appropriately controlled by a monochromator (Photonics, LPS-150), and images are captured with a Hamamatsu camera at 1 frame/s, both controlled by SimplePCI software (Compix). The application system was positioned close to the recording field, so that the solution exchange occurred within 10 s. PASMCs were perfused with high K+ Krebs solution (in mM: 82 NaCl, 59 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 10 d-glucose, pH 7.4), or Ca2+-free Krebs solution (in mM: 135 NaCl, 5.9 KCl, 3 MgCl2, 1 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 10 d-glucose, pH 7.4). The recording protocol consisted of 30-s perfusion with normal Krebs (to record the baseline calcium), 30-s high K+ Krebs (to estimate the response to depolarizing pulses), wash with Krebs for 2 min, and then either 30-s application of ANG II (1 μM in normal Krebs) or 8-min application of IGF-I (100 ng/ml in normal Krebs). For experiments in Ca2+-free Krebs, both ANG II and IGF-I were prepared in Ca2+-free Krebs, and their application was preceded by 1–3 min of Ca2+-free Krebs. ANG II or IGF-I were applied only once per dish. Only cells that have shown positive response to high K+ Krebs were included in the analysis. Results are expressed as 340- to 380-nm fluorescence ratio, corrected for the background.

Construction of fluorescent-tagged cyclin D adenovirus.

The human cyclin D1 cDNA clone was purchased from Origene and subcloned into the pEGFP-N1 vector (BD Clontech) to encode a cyclin d-green fluorescent protein (GFP) fusion protein. The sequence was then subcloned into the shuttle vector pShuttle-CMV for construction of an adenovirus using the AdEasy system (Stratagene). Recombinant Ad-cycD-GFP adenovirus was amplified in human embryonic kidney-293 cells and purified by CsCl gradient sedimentation.

RESULTS

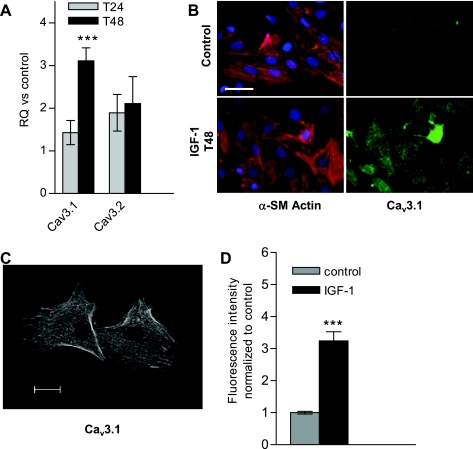

Vascular remodeling is a clinically relevant pathological response, extensive pulmonary artery remodeling due to PASMC proliferation is a hallmark of pulmonary hypertension, and IGF-I is a known mediator of VSMC proliferation via its action on cell cycle progression and mitogenesis (32). When cultured rat PASMCs were synchronized in serum-free medium and then stimulated to proliferate with IGF-I, an approximate threefold increase of the T-type Ca2+ channel Cav3.1 mRNA was observed after 48 h (Fig. 1A), with no effect on Cav3.2 mRNA. Immunostaining for Cav3.1 showed predominant cytoplasmic staining (Fig. 1B; although membrane staining was also visible in confocal images, Fig. 1C), and cytoplasmic fluorescence intensity was also elevated approximately threefold after 48 h of IGF-I treatment (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

Insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) upregulates T-type channels in cultured rat pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (PASMCs). A: rat PASMCs were serum starved for 2–3 days before IGF-I stimulation. After 24 and 48 h in IGF-I, PASMCs were harvested for RNA purification and quantitative RT-PCR. RQ represents the relative quantification vs. time-matched control, unstimulated cells and is calculated based on the ΔΔCt (comparative threshold cycle) method, using 18S rRNA as endogenous control. Values are means ± SE. Statistical significance is calculated using paired t-test on dCt values. ***P < 0.001. B: immunostain of α-smooth muscle (α-SM) actin (SM-22, red), voltage-gated calcium channel (Cav) 3.1 (green), and nuclei counterstained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; blue) in unstimulated (control) and 48-h IGF-I stimulated PASMCs. Scale bar = 50 μM. C: confocal image of Cav3.1 immunostain in 48-h IGF-I-treated PASMCs (as in B); scale bar represents 20 μm. D: averaged fluorescence intensity of Cav3.1-immunostained PASMCs with 48-h IGF-I treatment, normalized to control untreated PASMCs (as in B). Values are means ± SE. ***P < 0.001 for IGF-I (n = 61) vs. control (n = 41).

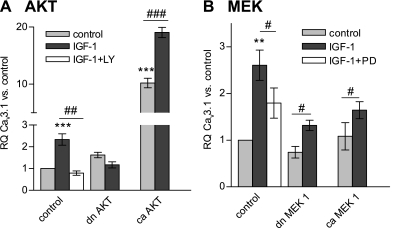

Mitogenic signaling by IGF-I can involve the activation of numerous signal transduction pathways in the cell. Therefore, we investigated whether the stimulation of T-type channel Cav3.1 transcription is downstream from PI3K/Akt or MAPK pathways that are known to be activated by IGF-I. Quiescent, synchronized PASMC cultures were treated with IGF-I and in the presence of the inhibitor LY-294002, the upregulation of Cav3.1 mRNA was completely abolished at 48 h, and, similarly, infection with a dominant-negative Akt adenovirus fully blocked Cav3.1 upregulation. On the other hand, constitutively active myristoylated Akt adenovirus led to a 10-fold increase in basal Cav3.1 mRNA levels that was stimulated even further by IGF-I (Fig. 2A). Effects of ERK1/2-MAPK pathway signaling on the expression of Cav3.1 were tested in a similar fashion by interfering with the activation of MEK1 (MAPK kinase, Fig. 2B). Treatment with IGF-I led to the typical two- to threefold increase in Cav3.1 mRNA in PASMCs after 48 h, and this increase was partially but significantly blocked by the ERK1/2 inhibitor PD-98059. In the presence of either caMEK1 or dominant-negative MEK1 adenovirus, IGF-I stimulation resulted in modest upregulation of Cav3.1 mRNA levels. Taken together, these experiments suggest that, in PASMCs, IGF-I affects the upregulation of the Cav3.1 T-type Ca2+ channel largely via Akt signaling.

Fig. 2.

Effect of signaling pathways activated by IGF-I on Cav3.1 upregulation. A: constitutively active (ca, n = 4) and dominant-negative (dn, n = 4) protein kinase B (Akt) isoforms were overexpressed in cultured rat PASMCs using adenovirus constructs. Forty-eight hours after infection, PASMCs were stimulated with 100 ng/ml IGF-I for another 48 h and then harvested for RNA purification (n = 3). RQ of Cav3.1 mRNA was calculated vs. control (β-galactosidase adenovirus infected, unstimulated) cells. The role of Akt activation in IGF-I-induced Cav3.1 upregulation was also tested by blocking the pathway with 10 μM LY-294002 (n = 4). B: ca (n = 4) and dn (n = 4) MEK1 isoforms were overexpressed in cultured rat PASMCs, which were then exposed to 100 ng/ml IGF-I for an additional 48 h. The role of ERK1/2 activation in IGF-I-induced Cav3.1 mRNA upregulation was also tested by blocking ERK1/2 with 10 μM PD-98059 (n = 4). Values are means ± SE. Statistical significance is calculated using paired t-test on dCt values. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. control (infected, unstimulated) PASMCs. #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 reflect the effect of the inhibitory action on IGF-I stimulation.

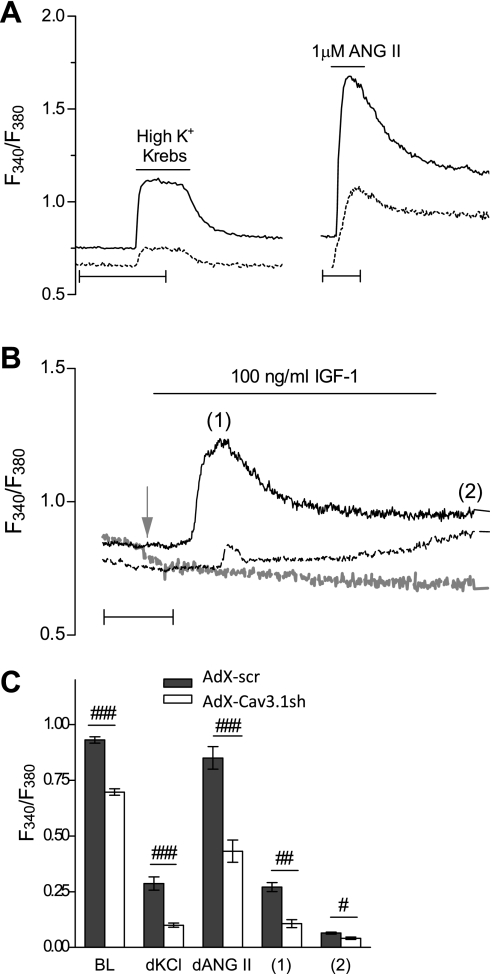

The relative contribution of T-type Ca2+ channels to calcium homeostasis in VSMCs remains questionable in normal conditions, but it may be relevant for quiescent and pathological events that require Ca2+ influx, such as cell cycle progression. For these experiments, efficient and specific knockdown of Cav3.1 was accomplished in PASMCs, which are relatively resistant to conventional transfection methods, using adenovirus-based RNA interference (Supplemental Figs. S1 and S2; the online version of this article contains supplemental data). When PASMCs were preinfected with the AdX-Cav3.1sh adenovirus and allowed a sufficient time for Cav3.1 knockdown, resting intracellular Ca2+ levels were significantly decreased compared with control (scrambled insert) “AdX-scr” adenovirus (Fig. 3). Furthermore, either membrane depolarization in high K+ Krebs solution or treatment with ANG II, a potent vasoconstrictor that also signals VSMC proliferation and growth (8), resulted in a rise in intracellular Ca2+ that was significantly decreased in AdX-Cav3.1sh-infected PASMCs (Fig. 3A). The Ca2+ responses to ANG II were also reduced when mibefradil was used as a selective blocker of T-type Ca2+ channels, further suggesting at least a partial contribution of T-type channels to Ca2+ influx (Supplemental Fig. S4). The acute effects of IGF-I on cytosolic Ca2+ in PASMCs were also tested in control and Cav3.1 knockdown conditions, and Fig. 3B shows that, in control AdX-scr-infected PASMCs, IGF-I led to elevated Ca2+ levels within 2 min following exposure. Out of the total of PASMCs infected with either AdX-scr (101 cells) or AdX-Cav3.1-sh (152 cells), 68.3% of AdX-scr-infected cells showed a Ca2+ response to IGF-I, while only 11.2% of AdX-Cav3.1sh-infected cells responded. A gradual increase in intracellular Ca2+ during the 8-min IGF-I exposure was present in 74% of AdX-scr vs. 37% of AdX-Cav3.1sh-infected PASMCs. Importantly, when Ca2+ was omitted from the extracellular solution, no cytosolic Ca2+ increase was measurable in response to 100 ng/ml IGF-I (shaded line in Fig. 3B). Baseline resting Ca2+ before IGF-I application was reduced when Cav3.1 was knocked down, as was the peak Ca2+ response to acute IGF-I stimulation. Experiments in 0 mM Ca2+ confirmed that these acute effects of IGF-I are dependent on extracellular Ca2+ influx. Results of the above experiments are summarized in Fig. 3C.

Fig. 3.

Effect of Cav3.1 knockdown on calcium influx in rat PASMCs. A: intracellular Ca2+ levels measured with fura-2 AM in both AdX-scr- and AdX-Cav3.1sh-infected PASMCs, at least 5 days after infection, expressed as ratio of fluorescence intensity at 340 and 380 nm (F340/F380). Representative traces are for resting levels of Ca2+ and the response to high K+ (60 mM) Krebs or 1 μM angiotensin (ANG) II in AdX-scr- (solid line) and AdX-Cav3.1sh-infected (dotted line) PASMCs. Scale bars represent 50 s. B: representative traces for Ca2+ levels in response to 100 ng/ml IGF-I in 2 mM Ca2+ Krebs solution of AdX-scr- (solid line) or AdX-Cav3.1sh-infected (dashed line) PASMCs, or the response to IGF-I in 0 mM Ca2+ Krebs of AdX-scr-infected PASMCs (dashed shaded line). Time scale represents 2 min. Shaded arrow denotes point of application of Ca2+-free Krebs solution interrupted during preapplication of Ca2+-free Krebs solution. C: quantification of resting baseline (BL) intracellular Ca2+ levels (98 and 72 cells for AdX-scr and AdX-Cav3.1sh) expressed as F340/F380, while high KCl (67 and 65 cells) and ANG II response (72 and 39 cells) are expressed as difference between the peak and the BL (dKCl, dAngII). Ratio is shown for IGF-I-treated cells at peak (1) and at 8 min after IGF-I application (2) in AdX-scr- (n = 61 of 81) or AdX-Cav3.1sh-infected (9 of 18) PASMCs. Values are means ± SE. Statistical significance is calculated using unpaired t-test. ###P < 0.001, ##P < 0.01, and #P < 0.01 for AdX-Cav3.1sh vs. AdX-scr.

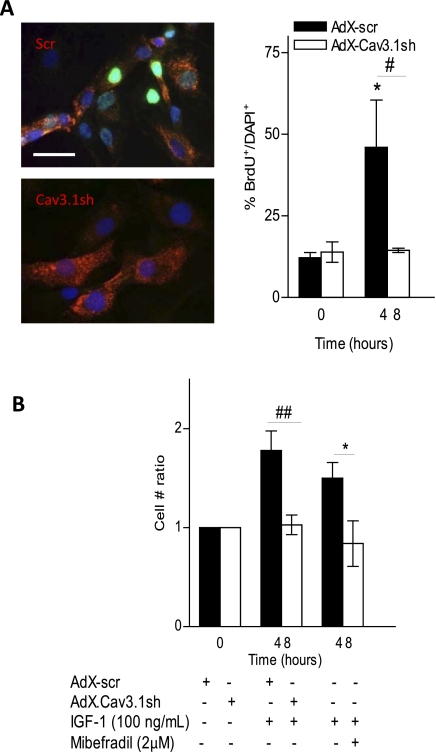

Considering the known mitogenic effect of IGF-I and its observed effects on Cav3.1 expression, we tested the hypothesis that, in pathology, the upregulation of Cav3.1 is part of a positive feedback mechanism that potentiates proliferation induced by growth factors such as IGF-I. Proliferation of PASMCs was examined following IGF-I stimulation, by both BrdU incorporation and cell counting. Nuclear incorporation of BrdU increased significantly following 48 h of IGF-I treatment, and, when the Cav3.1 T-type Ca2+ channel was knocked down with AdX-Cav3.1sh, IGF-I-stimulated proliferation was significantly reduced (Fig. 4A). A similar effect of Cav3.1 shRNA-mediated knockdown was seen when PASMC proliferation was assessed by cell counting (Fig. 4B), and the inclusion of 3 μM mibefradil during IGF-I stimulation also abolished the increase in cell number ratio (Fig. 4B), suggesting that IGF-I-stimulated proliferation of PASMCs is dependent on the Cav3.1 T-type Ca2+ channel.

Fig. 4.

Effect of Cav3.1 downregulation on rat PASMC proliferation. A: PASMCs were infected for 5 days and maintained in 0.1% FBS to block further proliferation, then pulsed with bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) and stimulated with IGF-I for 48 h. Representative immunostaining for BrdU incorporation at 48-h IGF-I stimulation is shown, with BrdU nuclear staining (green), counterstained with DAPI (blue). DsRed fluorescence was present in all Cav3.1sh-infected cells, confirming the presence of the short hairpin RNA (shRNA). BrdU-positive nuclei (BrdU+) were counted and expressed as percentage of total number of nuclei (DAPI+) (n = 4 experiments). *P < 0.05 vs. time (T) = 0 control. Scale bar = 20 μM. B: cell counts after IGF-I stimulation, in AdX-Cav3.1sh- vs. AdX-scr-infected PASMCs. Cell number was normalized to time-matched control (infected, unstimulated) PASMCs, and statistical significance is calculated using paired t-test. *P < 0.05 vs. control PASMCs at T = 0 (n = 7). Also shown are cell counts in IGF-I-stimulated PASMCs at T = 48 ± 3 μM mibefradil (n = 4 experiments, cell no. ratio = 0.84 ± 0.23 vs. unstimulated control, not significant). *P < 0.05 for minus vs. plus mibefradil. #P < 0.05 (A) and ##P < 0.01 (B) for AdX-Cav3.1sh vs. AdX-scr at T = 48 h IGF-I stimulation. Values are means ± SE.

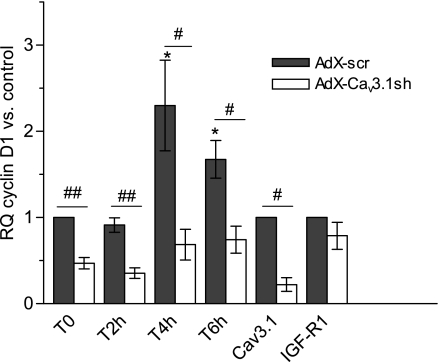

The mitogenic action of IGF-I is also closely associated with cell proliferation via the activation of cyclins. Production and activation of cyclins associated with the G1 phase (cyclins D, E, and A) provide checkpoints of early cell proliferation signaling (31). Considering that cyclin D is an early regulator of cell cycle initiation, and Ca2+ regulation is critical for cell cycle progression, we examined IGF-I-stimulated cyclin D activation and its possible association with the Cav3.1 T-type Ca2+ channel. Preliminary fluorescence-activated cell sorting cell cycle analyses on IGF-I stimulated PASMCs indicated that, within the first 24 h, ∼25% of the cells progress through the S phase (not shown). We found that exposure to IGF-I led to upregulation of cyclin D mRNA at 4 and 6 h (Fig. 5). When the Cav3.1 Ca2+ channel was first knocked down with AdX-Cav3.1sh, cyclin D expression was significantly reduced at time 0, before IGF-I application, and, furthermore, knockdown of the Cav3.1 channel prevented the IGF-I stimulation of cyclin D mRNA. Notably, in the same cultures, Cav3.1 knockdown had no significant effect on expression of IGF receptor mRNA (also shown in Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Effect of Cav3.1 downregulation on cyclin D1 transcription. PASMCs were infected for 5 days with AdX-scr or AdX-Cav3.1sh and maintained in 0.1% FBS to block further proliferation and then stimulated with 100 ng/ml IGF-I. Cells were harvested at 2 h (n = 4), 4 h (n = 5), and 6 h (n = 4), and RQ of cyclin D1 was calculated vs. control (T = 0, AdX-scr infected) PASMC. Relative levels of Cav3.1 and IGF receptor (IGF-R1) mRNAs were assayed in the same samples. Values are means ± SE. Statistical significance is calculated on dCt values using paired t-test. *P < 0.05 vs. T = 0, AdX-scr control PASMCs. #P < 0.05, ##P < .01 vs. time-matched Adx-scr.

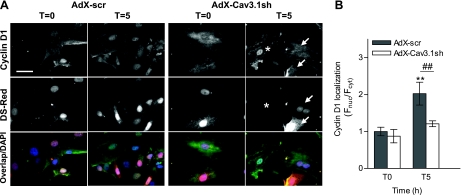

When endogenous cyclin D1 was examined by immunostaining, nuclear translocation was observed within 5 h of treatment with IGF-I, and this effect was reduced when Cav3.1 T-type channels were knocked down with AdX-Cav3.1sh (Fig. 6). For additional studies on cyclin D translocation in PASMCs, a fluorescent GFP-tagged cyclin D1 was incorporated into an adenoviral vector (“Ad-CycD-GFP”), PASMCs were infected, and the ratio of nuclear to cytoplasmic GFP was examined as an indicator of cyclin D activation (see Supplemental Fig. S5).

Fig. 6.

Effect of Cav3.1 knockdown on endogenous cyclin D1 nuclear translocation in PASMCs. A: PASMC were infected for 5 days with AdX-scr or AdX-Cav3.1sh and maintained in 0.1% FBS to block further proliferation and then stimulated with 100 ng/ml IGF-I and fixed for cyclin D1 immunostaining (top row). Ds-Red representing infection with AdX-Cav3.1sh is shown in the middle row, and color overlap images with nuclear DAPI are shown (bottom row). Arrows point to shRNA-infected PASMCs, where nuclear translocation is blocked, and in the same field, * denotes an uninfected cell with cyclin D nuclear translocation. B: quantification of cyclin D1 nuclear localization based on ratio of the fluorescence intensity in the nucleus (Fnuc) and cytoplasm (Fcyt). Values are means ± SE. Values are normalized to AdX-scr infected at T = 0. **P < 0.01 for AdX-scr-infected cells at T = 5 h post-IGF-I treatment (n = 16) vs. T = 0 (n = 18). ##P < 0.01 for AdX-Cav3.1sh-infected cells at T = 5 h vs. AdX-scr at T = 5 h (n = 25).

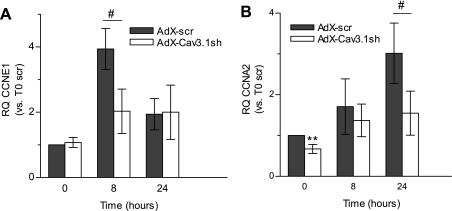

The transcription of cyclins D, E, and A is regulated in sequence as the cell cycle progresses from the G1 through the S phase, and, consistent with this, in PASMCs treated with IGF-I, we observed significant increases in cyclin E1 mRNA after 8 h, and for cyclin A2 mRNA at 24 h (Fig. 7). Similar to the impaired activation of cyclin D1 at early time points, knockdown of the Cav3.1 T-type Ca2+ channel with AdX-Cav3.1sh also interfered with the production of these downstream cyclins.

Fig. 7.

Effect of Cav3.1 knockdown on the IGF-I-stimulated transcription of cyclins. RQ of cyclin E1 (CCNE1; A) and cyclin A2 (CCNA2; B) mRNA in PASMCs at 8 and 24 h after 100 ng/ml IGF-I stimulation are shown. RQ is calculated vs. control (T = 0, AdX-scr infected). Values are means ± SE. Statistical significance is calculated using paired t-test. **P < 0.01 vs. time-matched AdX-scr-infected PASMCs. #P < 0.05 for AdX-scr vs. AdX-Cav3.1sh. For cyclin E, n = 4. For cyclin A, n = 6.

DISCUSSION

In pathological conditions that invoke structural and functional vessel remodeling, cellular components of the arterial wall undergo numerous phenotypic changes. An important aspect of vascular remodeling processes, such as atherosclerosis and restenosis, is the transformation of VSMCs from a differentiated to a proliferative state. Increases in cytosolic Ca2+ by the concerted action of extracellular and intracellular Ca2+ sources can then contribute to changes in gene expression, cell cycle regulation, VSMC migration, and proliferation. Our results suggest that LVA T-type Ca2+ channels may play a unique role in cell cycle/proliferation signaling in the vascular response to injury. Using RNA interference, we demonstrate that the Cav3.1 Ca2+ channel contributes to resting intracellular Ca2+ levels in PASMCs, as well as to intracellular Ca2+ increases stimulated with high K+, ANG II, or IGF-I. In addition to the acute effects of IGF-I on cytosolic Ca2+ that require Cav3.1 channel expression, more prolonged exposure of PASMCs to IGF-I stimulates cell proliferation and also leads to an increase in Cav3.1 mRNA levels that is largely influenced by PI3K/Akt signaling. When Cav3.1 expression was blocked, so was early cell cycle signaling by cyclin D, and the mitogenic action of IGF-I. Taken together, these results suggest a mechanism by which IGF-I can influence the proliferation of PASMCs via Akt-mediated increases in Cav3.1 T-type channels, and their interaction with cell cycle signaling cascades.

Contribution of the Cav3.1 T-type channel to intracellular calcium.

Our laboratory's earlier studies in the A7r5 aortic VSMC line using relatively selective concentrations of mibefradil implicated a role for T-type Ca2+ channels in the generation of arginine vasopressin-stimulated Ca2+ spiking, which may relate to the maintenance of peripheral resistance and blood pressure (4). However, up to now, the functional contributions of T-type Ca2+ channels in VSMCs are poorly understood (6, 7), and they have not been investigated in conditions of vascular injury, where they could potentially be a therapeutic target. Here we present IGF-I as one mitogenic stimulus that may potentiate the effects of Cav3.1 T-type Ca2+ channels in cultured PASMCs.

We determined that infection with the AdX-Cav3.1sh adenovirus leads to specific knockdown of Cav3.1 T-type channels, with no effect on transient receptor potential channel 1 (TrpC1) and TrpC6 mRNA expression or on L-type Ca2+ currents (supplemental data). Therefore, we conclude that the reduction of induced Ca2+ responses in AdX-Cav3.1sh-infected PASMCs is linked to the knockdown of T-type channels, as opposed to other known sources of Ca2+ influx. We hypothesize that, in the disease setting in which growth factors and cytokines are activated, T-type Ca2+ channels become a significant source of Ca2+ as effectors of downstream signaling processes important for VSMC proliferation (see below). The upregulation of Cav3.1 mRNA expression by IGF-I may represent a potentiating effect of IGF-I on T-type Ca2+ channel influx that further enhances its putative signaling capabilities.

The RNA interference studies show that IGF-I-stimulated Ca2+ influx through Cav3.1 channels in PASMCs has a crucial, as yet undefined role in regulating intracellular Ca2+ and, hence, cellular function. Because of their transient nature and relatively small conductance, T-type Ca2+ channels are not likely to contribute directly to the observed cytosolic Ca2+ increases in VSMCs, but, rather, they may influence calcium homeostasis indirectly by interacting with other extracellular Ca2+ sources, such as voltage-gated L-type Ca2+ channels or canonical TRPCs (e.g., TRPC1 or TRPC6) (13, 36). T-type Ca2+ channels could also affect cytosolic Ca2+ levels in PASMCs by influencing Ca2+ release from the intracellular stores, an important component of Ca2+ regulation in VSMCs (1).

Our experiments did not address acute effects of IGF-I on T-type Ca2+ channel activity, which could be either direct or indirect (e.g., channel modulation by Akt or other kinases, phosphatases, or G proteins). Most of the known modulatory effects on T-type channels are on the Cav3.2 isotype (25), which was relatively unaffected in PASMCs by IGF-I treatment and does not seem to be a significant source of Ca2+ during cell proliferation, since knocking down Cav3.1 alone in our experiments was sufficient to block the activation of cyclins. This emphasizes that the Cav3.1 and Cav3.2 T-type channel isotypes have distinct functional roles in the cell, as our laboratory has observed previously in cultured neonatal rat ventricular myocytes (29).

Growth factor stimulation of PASMC proliferation.

In diseased, injured, and hypoxic blood vessels, the release of numerous growth factors and cytokines provides a signal for medial smooth muscle cell proliferation and vascular remodeling. We initially tested the effects of known mitogens (PDGF, IGF-I, and basic fibroblast growth factor) on Cav3.1 expression in both human and rat PASMCs, and chose IGF-I for further study based on its reproducible effects (Fig. 1). Although >90% of cultured PASMCs were smooth muscle cells based on positive immunostain for α-smooth muscle actin, we observed nonuniform responses to IGF-I. According to our results with FACS and BrdU incorporation only, a subset of the arrested cells responded by entering the cell cycle. This may be a reflection of previous reports, where the proliferation response of PASMCs differed, depending on their site of origin within the vessel (proximal or distal to the main branch pulmonary artery, and inner, middle vs. outer media) (12). In the latter study, heterogeneity in the response was at least partially attributed to alternative usage of cell signaling pathways (namely, PKC) by the different subpopulations of PASMCs, which underscores the need to further investigate the interactions between T-type Ca2+ channel activity and growth factor-mediated signaling.

Role of T-type Ca2+ channels in IGF-I signaling pathways.

Our results support the idea that calcium entry through T-type channels in particular is targeted to specific cellular signaling mechanisms, which, in this case, are related to cell cycle and proliferation signaling. IGF-I can have mitogenic effects through two main signal transduction pathways: PI3K/Akt or MAPK/ERK1/2, which are activated in VSMCs and are relevant for proliferation and vascular remodeling. The same pathways may be activated by other growth factors and cytokines, and cross talk between these parallel signaling pathways can also occur to further affect cellular functions. Our experiments made use of adenoviruses encoding caMEK1 or dominant-negative variants of pathway components Akt or MEK1 (upstream from ERK1/2). The activation of Akt led to remarkable upregulation of Cav3.1 mRNA that was further increased by IGF-I stimulation, and blocking the PI3K pathway either with LY-294002 or dominant-negative Akt completely abolished the IGF-I effects. Therefore, PI3K/Akt signaling is an important intermediary of the upregulation of Cav3.1 mRNA in PASMCs by IGF-I and possibly other effectors that activate Akt.

In similar experiments to investigate MAPK signaling, caMEK1 showed no stimulation of Cav3.1 mRNA in the absence of IGF-I, and blocking ERK1/2 with PD-98059 only partially inhibited IGF-I-mediated stimulation of Cav3.1. Also, interfering with MEK1 activity had minimal effects on the regulation of Cav3.1 mRNA levels by IGF-I, suggesting that MAPK signaling plays a minimal role relative to Akt in the IGF-I stimulation of Cav3.1. An unexpected observation was that the presence of caMEK1 interfered with the stimulatory effect of IGF-I on Cav3.1 expression (Fig. 2B). While IGF-I can activate both Akt and MEK1 signaling pathways, it is possible that, in these experiments, caMEK1 competes for a shared upstream activator, thereby diminishing the effects of Akt. Clearly, these two growth factor signaling mechanisms are utilized to different extents by VSMCs and can depend on cell type, stimulus, developmental stage, and pathological state (27). In aortic smooth muscle cells, both pathways are activated by IGF-I, and, whereas PI3K/Akt signaling primarily mediates cell migration (also an important aspect of vascular remodeling), MAPK signaling is more related to the proliferation response (17). Although we focused on the impact of IGF-I on proliferation, other consequences of Ca2+ influx via Cav3.1 channels in IGF-I-stimulated PASMCs warrant further investigation.

Role of Cav3.1 channels in cell cycle signaling.

Since proliferation of VSMCs is a key underlying factor in multiple diseases involving vascular remodeling, inhibition of cell cycle signaling in VSMCs can be considered as a therapeutic target (2). Studies on experimental models of vascular injury have revealed complex, temporally regulated responses involving growth factor release, activation of protooncogenes, and cell cycle signal transduction cascades as potential sites of therapeutic intervention. Calcium is required during two main phases of the mammalian cell cycle: 1) during early G1, and 2) in the G1-to-S phase transition (19, 34). Consistent with this, proliferating PASMCs display more depolarized membrane potentials and elevated cytosolic Ca2+ (28). Still, the pathways of Ca2+ influx are not fully defined, and there is incomplete information about the Ca2+-dependent mechanisms that control cell cycle and VSMC proliferation during vessel remodeling. Multiple lines of evidence have suggested that the LVA T-type Ca2+ channels are involved in cell cycle control, and our results suggest that, in PASMCs, T-type Ca2+ channels interact with cyclin D signaling to affect cell cycle activation during the early G1 phase. We observed elevated levels of cyclin D1 transcription in the initial hours following IGF-I stimulation of serum-deprived PASMCs, along with cyclin D nuclear translocation that was dependent on expression of the Cav3.1 Ca2+ channel (Figs. 5 and 6). These experiments clearly implicate LVA Ca2+ entry through Cav3.1 T-type channels as an essential component of cyclin D signaling and cell cycle progression, in keeping with the observed inhibition of proliferation in AdX-Cav3.1-infected PASMCs. The knockdown of Cav3.1 channels also had a negative influence on the expression of downstream cyclins A and E, which can involve Ca2+/calmodulin and calcineurin as Ca2+-dependent signaling intermediaries (35). While these observations support the importance of T-type Ca2+ channels in proper cell cycle progression, it remains unclear whether reduction of these downstream cyclins is an effect of the observed inhibition of cyclin D, or, alternatively, additional Ca2+-dependent processes rely on T-type Ca2+ channel activity.

T-type Ca2+ channels have been previously implicated in cell proliferation (22), and this is the first study to suggest a possible mechanism for T-type interaction in regulation of the cell cycle. The ability of Ca2+ entry through T-type channels to carry out such specified signaling roles (as opposed to other known sources of Ca2+ entry) suggests temporal or spatial compartmentalization of these channels in PASMCs, as has been suggested recently for T-type Ca2+ channels in cardiomyocytes (23), and should be the subject of future investigations aimed toward understanding their relevance in VSMC pathology.

GRANTS

These studies were supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant R01 HL075115 and a Cardiovascular Research Fellowship from the Ralph and Marian Falk Foundation to F. Pluteanu.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Abigail Prier for construction of the cyclin d-GFP adenovirus, and Chris Hill for excellent technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berridge MJ, Bootman MD, Lipp P. Calcium–a life and death signal (news). Nature 395: 645–648, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braun-Dullaeus RC, Mann MJ, Dzau VJ. Cell cycle progression : new therapeutic target for vascular proliferative disease. Circulation 98: 82–89, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braz J, Bueno O, De Windt LJ, Molkentin JD. PKC alpha regulates the hypertrophic growth of cardiomyocytes through extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2). J Cell Biol 156: 905–919, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brueggemann LI, Martin BL, Barakat J, Byron KL, Cribbs LL. Low voltage-activated calcium channels in vascular smooth muscle: T-type channels and AVP-stimulated calcium spiking. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288: H923–H935, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chiang CS, Huang CH, Chieng H, Chang YT, Chang D, Chen JJ, Chen YC, Chen YH, Shin HS, Campbell KP, Chen CC. The Cav3.2 T-type Ca2+ channel is required for pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy in mice. Circ Res 104: 522–530, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cribbs LL. T-type Ca2+ channels in vascular smooth muscle: multiple functions. Cell Calcium 40: 221–230, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cribbs LL. Vascular smooth muscle calcium channels: could “T” be a target? Circ Res 89: 560–562, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daemen M, Lombardi D, Bosman F, Schwartz S. Angiotensin II induces smooth muscle cell proliferation in the normal and injured rat arterial wall. Circ Res 68: 450–456, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dale B, Yazaki I, Tosti E. Polarized distribution of L-type calcium channels in early sea urchin embryos. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 273: C822–C825, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Day ML, Johnson MH, Cook DI. Cell cycle regulation of a T-type calcium current in early mouse embryos. Pflugers Arch 436: 834–842, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delafontaine P, Song YH, Li Y. Expression, regulation, and function of IGF-1, IGF-1R, and IGF-1 binding proteins in blood vessels. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 24: 435–444, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dempsey EC, Frid MG, Aldashev AA, Das M, Stenmark K. Heterogeneity in the proliferative response of bovine pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells to mitogens and hypoxia: importance of protein kinase C. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 75: 936–944, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Golovina VA, Platoshyn O, Bailey CL, Wang J, Limsuwan A, Sweeney M, Rubin LJ, Yuan JX. Upregulated TRP and enhanced capacitative Ca2+ entry in human pulmonary artery myocytes during proliferation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 280: H746–H755, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo W, Kamiya K, Kodama I, Toyama J. Cell cycle-related changes in the voltage-gated Ca2+ currents in cultured newborn rat ventricular myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol 30: 1095–1103, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hassoun PM, Mouthon L, Barbera JA, Eddahibi S, Flores SC, Grimminger F, Jones PL, Maitland ML, Michelakis ED, Morrell NW, Newman JH, Rabinovitch M, Schermuly R, Stenmark KR, Voelkel NF, Yuan JX, Humbert M. Inflammation, growth factors, and pulmonary vascular remodeling. J Am Coll Cardiol 54: S10–S19, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horiba M, Muto T, Ueda N, Opthof T, Miwa K, Hojo M, Lee JK, Kamiya K, Kodama I, Yasui K. T-type Ca2+ channel blockers prevent cardiac cell hypertrophy through an inhibition of calcineurin-NFAT3 activation as well as L-type Ca2+ channel blockers. Life Sci 82: 554–560, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Imai Y, Clemmons D. Roles of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in stimulation of vascular smooth muscle cell migration and deoxyribonucleic acid synthesis by insulin-like growth factor-I. Endocrinology 140: 4228–4235, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Izumi T, Kihara Y, Sarai N, Yoneda T, Iwanaga Y, Inagaki K, Onozawa Y, Takenaka H, Kita T, Noma A. Reinduction of T-type calcium channels by endothelin-1 in failing hearts in vivo and in adult rat ventricular myocytes in vitro. Circulation 108: 2530–2535, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kahl CR, Means AR. Regulation of cell cycle progression by calcium/calmodulin-dependent pathways. Endocr Rev 24: 719–736, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koyama T, Ono K, Watanabe H, Ohba T, Murakami M, Iino K, Ito H. Molecular and electrical remodeling of L- and T-type Ca2+ channels in rat right atrium with monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension. Circ J 73: 256–263, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuga T, Kobayashi S, Hirakawa Y, Kanaide H, Takeshita A. Cell cycle-dependent expression of L- and T-type Ca2+ currents in rat aortic smooth muscle cells in primary culture. Circ Res 79: 14–19, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lory P, Bidaud I, Chemin J. T-type calcium channels in differentiation and proliferation. Cell Calcium 40: 135–146, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakayama H, Bodi I, Correll RN, Chen X, Lorenz J, Houser SR, Robbins J, Schwartz A, Molkentin JD. α1G-dependent T-type Ca2+ current antagonizes cardiac hypertrophy through a NOS3-dependent mechanism in mice. Journal of Clinical Investigation 119: 3787–3796, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nuss HB, Houser SR. T-type Ca2+ current is expressed in hypertrophied adult feline left ventricular myocytes. Circ Res 73: 777–782, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perez-Reyes E. G Protein-mediated inhibition of Cav3.2 T-type channels revisited. Mol Pharmacol 77: 136–138, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perez-Reyes E. Molecular characterization of T-type calcium channels. Cell Calcium 40: 89–96, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petley T, Graff K, Jiang W, Yang H, Florini J. Variation among cell types in the signaling pathways by which IGF-I stimulates specific cellular responses. Horm Metab Res 31: 70–76, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Platoshyn O, Golovina VA, Bailey CL, Limsuwan A, Krick S, Juhaszova M, Seiden JE, Rubin LJ, Yuan JX. Sustained membrane depolarization and pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell proliferation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 279: C1540–C1549, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pluteanu F, Cribbs LL. T-type calcium channels are regulated by hypoxia/reoxygenation in ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 297: H1304–H1313, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodman DM, Reese K, Harral J, Fouty B, Wu S, West J, Hoedt-Miller M, Tada Y, Li KX, Cool C, Fagan K, Cribbs L. Low-voltage-activated (T-type) calcium channels control proliferation of human pulmonary artery myocytes. Circ Res 96: 864–872, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sherr CJ, Roberts JM. CDK inhibitors: positive and negative regulators of G1-phase progression. Genes Dev 13: 1501–1512, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stiles CD, Capone GT, Scher CD, Antoniades HN, Van Wyk JJ, Pledger WJ. Dual control of cell growth by somatomedins and platelet-derived growth factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 76: 1279–1283, 1979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takebayashi S, Li Y, Kaku T, Inagaki S, Hashimoto Y, Kimura K, Miyamoto S, Hadama T, Ono K. Remodeling excitation-contraction coupling of hypertrophied ventricular myocytes is dependent on T-type calcium channels expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 345: 766–773, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takuwa N, Zhou W, Takuwa Y. Calcium, calmodulin and cell cycle progression. Cell Signalling 7: 93–104, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tomono M, Toyoshima K, Ito M, Amano H, Kiss Z. Inhibitors of calcineurin block expression of cyclins A and E induced by fibroblast growth factor in Swiss 3T3 fibroblasts. Arch Biochem Biophys 353: 374–378, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu Y, Sweeney M, Zhang S, Platoshyn O, Landsberg J, Rothman A, Yuan JX. PDGF stimulates pulmonary vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation by upregulating TRPC6 expression. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 284: C316–C330, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yumi K, Fagin JA, Yamashita M, Fishbein MC, Shah PK, Kaul S, Niu W, Nilsson J, Cercek B. Direct effects of somatostatin analog octreotide on insulin-like growth factor-I in the arterial wall. Lab Invest 76: 329–338, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]