Abstract

Normal hearts have increased contractility in response to catecholamines. Because several lipids activate PKCs, we hypothesized that excess cellular lipids would inhibit cardiomyocyte responsiveness to adrenergic stimuli. Cardiomyocytes treated with saturated free fatty acids, ceramide, and diacylglycerol had reduced cellular cAMP response to isoproterenol. This was associated with increased PKC activation and reduction of β-adrenergic receptor (β-AR) density. Pharmacological and genetic PKC inhibition prevented both palmitate-induced β-AR insensitivity and the accompanying reduction in cell surface β-ARs. Mice with excess lipid uptake due to either cardiac-specific overexpression of anchored lipoprotein lipase, PPARγ, or acyl-CoA synthetase-1 or high-fat diet showed reduced inotropic responsiveness to dobutamine. This was associated with activation of protein kinase C (PKC)α or PKCδ. Thus, several lipids that are increased in the setting of lipotoxicity can produce abnormalities in β-AR responsiveness. This can be attributed to PKC activation and reduced β-AR levels.

Keywords: heart, fatty acids, lipotoxicity

disorders associated with greater accumulation of triglycerides (TGs) in nonadipose tissues have become increasingly common and are termed lipotoxicities. These disorders include nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), which is due to skeletal muscle and liver insulin resistance and reduced islet cell insulin secretion (61). The heart is also a site of lipid-induced dysfunction (27, 66). Studies in obesity (1), T2DM (4), and metabolic syndrome (52) confirm a relationship between greater cardiac TG content and reduced heart function. Aside from reduced contractile function, these patients also develop abnormalities of cardiac rhythm and are more likely to die from arrhythmias (62).

The causes of organ dysfunction in lipotoxicities are unclear. Saturated long-chain fatty acids (LCFA), particularly palmitic acid (PA; 16:0), are considered to be a more potent cause of lipotoxicity than unsaturated LCFA such as oleic acid (OA; 18:1) (10, 42, 68).

A central process that allows for normal cardiac function is its response to catecholamines that are secreted by the sympathetic nervous system. β-adrenergic receptor (β-AR) stimulation by catecholamines increases cardiac contractile force and rate (16). This process can be blocked by activation of protein kinase Cs (PKCs) (23). PKCs constitute a lipid-sensitive Ser/Thr kinase family that shares a common structural motif. Activation of PKC either directly or via G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 (GRK2) leads to phosphorylation of the β-AR, both inactivating the receptor and increasing its internalization (29). Moreover, PKCα activation has been associated with impaired cardiac contractility (6), whereas genetic (24, 35) and pharmacological (12, 24, 35) inhibition of PKCs improves cardiac responsiveness to catecholamines and heart function in cardiomyopathic mice.

PKC activation by intracellular lipids involves initial phosphorylation of the enzyme followed by calcium and diacylglycerol (DAG) or ceramide binding to the enzyme and translocation from the cytosol to the membrane. Activation of several PKC isoforms has been linked to pathological mechanisms such as insulin resistance (17, 28), apoptosis (20), endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress (49), and inflammation (43).

Here we show that treatment of cardiomyocytes with saturated lipids led to impaired response to adrenergic stimulation. This was associated with PKC activation and reduced β-AR density. Moreover, a similar defect in adrenergic signaling was documented in several genetic and dietary models of cardiac lipotoxicity. Notably, this defect was observed prior to the development of overt cardiac dysfunction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

All chemical reagents used were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Cells.

A human ventricular cardiomyocyte-derived cell line, designated AC-16, was kindly provided by M. M. Davidson (14). Cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium-nutrient mixture F-12 (DMEM-F-12; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Human embryonic kidney (HEK)-293 cells that are stably transfected with green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged β2-AR cDNA (GFP-β2AR cells) were provided by Dr. Graeme Milligan (University of Glasgow, Scotland, UK) (39). Adult rat primary cardiomyocytes (RPCM) were provided by Dr. Steven O. Marx (Columbia University).

Cell treatments with lipids.

AC16 cells were grown in DMEM-F-12 medium containing FBS (10%) and antibiotics (1%) and were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2-95% air until 85–90% confluent. GFP-β2AR cells were grown in DMEM containing FBS (10%) and antibiotics (1%). RPCM were grown as described elsewhere (41). RPCM were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 2% CO2-98% air. After washing, each cell type was incubated in 1% FBS-containing medium, in which 1% BSA was added, along with LCFA, ceramide, or DAG, and cells were incubated for 14 h.

Cellular neutral lipid staining.

Intracellular neutral lipids were stained with Oil Red O, as described previously (55).

DAG and ceramide measurement.

LCFA-treated AC-16 cells were harvested, and pellets were weighed and assayed for DAG and ceramide levels, using the diacylglycerol kinase method as described (45).

RNA purification and gene expression analysis.

Total RNA was purified from cells using the TRIzol reagent according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Invitrogen). cDNA was synthesized using the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis SuperMix (Invitrogen). cDNA was analyzed with quantitative real-time PCR that was performed with SYBR Green PCR Core Reagents (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Incorporation of the SYBR green dye into the PCR products was monitored in real time with an Mx3000 sequence detection system (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Samples were normalized against β-actin. The sequences of the primers are provided in Supplemental Table S1 (Supplemental Material for this article is available online at the AJP-Endocrinology and Metabolism web site).

Cyclic AMP assay.

Control and LCFA-treated cells were washed with Krebs-Ringer buffer and stimulated with 100 nM isoproterenol in PBS. The concentration of cyclic AMP (cAMP) was determined with the CatchPoint Cyclic-AMP Fluorescent Assay Kit according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Control treatments were performed with either PBS or 100 nM forskolin in PBS. Obtained values were normalized with total protein concentration as determined with the Modified Lowry Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific, Fremont, CA).

Protein analysis.

Isolated heart tissues or cells were homogenized in PBS containing protease inhibitors and phosphatase inhibitors (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). Membrane and cytosolic fractions were separated by ultracentrifugation. Twenty micrograms from each fraction was applied to SDS-PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. Antibodies were obtained from the following suppliers: PKCα, Millipore (Billerica, MA); PKCβ, -δ, -ϵ, and -ζ, Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA).

Immunoprecipitation.

Immunoprecipitation of specific PKC isoforms was done with protein A/G Plus UltraLink resin (Thermo Scientific) according to the instructions of the manufacturer.

PKC activity assay.

PKC activity was assessed with the nonradioactive PKC Kinase Activity Assay Kit according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Assay Designs, Ann Arbor, MI). Obtained values were normalized with total protein concentration.

Confocal laser-scanning microscopy.

GFP-β2AR cells were observed using a laser-scanning confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss Laser Scanning System LSM 510; Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) with a Zeiss Plan-Apo 40 × 1.3 NA oil immersion objective, pinhole of 1 airy unit, and scan zoom 1. The GFP was excited using a 488-nm argon laser and detected with a 515- to 540-nm band pass filter. The images were manipulated with Zeiss LSM Image Browser version 4.2.0.121 (Zeiss) software. When examining the distribution of the receptors, live cells were used. The cells were grown on 35-mm glass bottom dishes at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2-95% air and mounted on the imaging chamber. The cells were maintained at room temperature during monitoring.

Transfection with small interfering RNA oligonucleotides.

Small interfering (si)RNA oligonucleotides for PKCα and PKCδ were obtained from Applied Biosystems (Carlsbad, CA). The sequences are provided in Supplemental Table S2. siRNA oligos were transfected in the cells with the siPORT NeoFX Transfection Agent according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Applied Biosystems). Cells were assayed 24–48 h posttransfection.

Animals.

All procedures involving animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Columbia University. Mice were maintained under appropriate barrier conditions in a 12:12-h light-dark cycle and received food and water ad libitum. The animals that were used for this study were C57BL/6 mice and mice expressing specifically in cardiomyocytes a GPI-anchored lipoprotein lipase [α-myosin heavy chain (MHC)-LpLGPI], peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (α-MHC-PPARγ), or acyl-CoA synthetase (α-MHC-ACS). All mice were on the C57BL/6 background, except for the α-MHC-ACS mouse model that was on the FVB background. All studies were performed on the different genotypes with littermates as controls. Male C57BL/6 mice were fed either a high-fat diet containing 60% kcal as fat (Diet no. 12492; Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ) or regular chow diet for 23 wk, at the end of which they were catheterized to assess heart function as described below. Hearts from these mice were harvested, flash-frozen, and stored at −80°C until further use. These hearts were then analyzed for PKCα and PKCδ protein expression in the membrane and cytosolic fractions, as described above. All analyses involving animals were performed with at least four mice per experimental group.

Echocardiography.

Two-dimensional echocardiography was performed on 10- to 12-wk-old male mice (n = 6–7/group) anesthetized with isofluorane (Sonos 5500 system; Philips Medical Systems, Andover, MA) (59). Echocardiographic images were recorded in a digital format. Images were then analyzed offline by a single observer blinded to the murine genotype (64).

In vivo cardiac function measurements.

Mice from the different groups were anesthetized using pentobarbital sodium (50–100 mg/kg ip). The right carotid artery was cannulated with a 1.4-F Millar MIKRO-TIP catheter/pressure transducer (SPR-671) (Millar Instruments, Houston, TX), and the catheter was advanced into the left ventricle. Another catheter (an 0.012-in. silicone tubing attached to a 30-gauge needle) was inserted into the femoral vein for administration of drugs. After completion of all the surgical procedures, the animal was allowed to stabilize for ∼15 min, followed by recording of basal hemodynamic parameters. Myocardial responses to increasing doses of dobutamine (1, 3, 10, and 30 μg/kg) administered at 1- to 2-min intervals were determined. Data calculation was achieved using the PowerLab software (AD Instruments, Colorado Springs, CO).

Saturation ligand binding.

Plasma membranes from excised mouse hearts or from AC-16 cells were prepared, and saturation ligand binding was performed as described previously (36), using 125I-CYP (iodocyanopindolol; PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) for β-AR density measurement. Data were analyzed by nonlinear regression analysis using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

Plasma catecholamine measurements.

Plasma epinephrine (Epi) and norepinephrine (NE) levels were determined by ELISA and performed on mouse plasma samples with the BI-CAT EIA kit (ALPCO Diagnostics, Salem, NH), as described previously (36, 63). For these analyses, mice were anesthetized by inhalation of isofluorane.

Lipid extraction and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry analyses.

Lipid extraction was performed as described previously (38), with minor modifications.

All experiments were carried out on a Waters Xevo TQ MS Acquity UPLC system (Waters, Milford, MA). The system was controlled by Mass Lynx Software 4.1. The sample was maintained at 6°C in the autosampler, and 7.5 μl was loaded onto a Waters Acquity UPLC BEH Phenyl column (3 mm inner diameter × 100 mm with 1.7 μm particles), preceded by a 2.1 × 5 mm guard column containing the same packing material. The column was maintained at 40°C throughout the analysis. The UPLC flow rate was continuously 300 μl/min in a binary gradient mode with the following mobile phase: initial flow conditions were 85.5% solvent A [H2O, containing 0.05% triethylamine (TEA)] and 14.5% solvent B (acetonitrile, containing 0.05% TEA); solvent B was increased linearly to 42.5% over a 7-min period, and this was followed by a reduction of solvent B starting at 7.5 min and continuing through 8 min. Fatty acyl-CoAs of interest eluted between 3.5 and 6.5 min. Positive ESI-MS/MS was performed using the following parameters: capillary voltage, 3.8 kV; source temperature, 150°C; desolvation temperature, 500°C; desolvation gas flow, 1,000 l/h; and collision gas flow, 0.15 ml/min. The optimized cone voltage was 58 V, and collision energy for neutral loss and multiple reactions monitoring mode was 34 eV. For multiple reactions monitoring analysis, the following transitions were employed: myristoyl-CoA 978.4→471.4 m/z, palmitoleoyl-CoA 1,004.3→497.3 m/z, palmitoyl-CoA 1,006.4→499.5 m/z, heptadecanoyl-CoA 1,020.4→513.5 m/z, linolenoyl-CoA 1,028.4→521.4 m/z, linoleoyl-CoA 1,030.4→523.4 m/z, oleoyl-CoA 1,032.4→525.5 m/z, stearoyl-CoA 1,034.4→527.5 m/z, arachidonoyl-CoA 1,054.4→547.4 m/z, eicosanoyl-CoA 1,062.4→555.4 m/z, and docosahexaenoyl-CoA 1,078.4→571.4 m/z.

Statistical analysis.

All data on cardiac function assessed by in vivo catheter were analyzed by repeated-measures two-way ANOVA. Comparisons between two groups were performed using unpaired two-tailed Student's t-tests. All values are presented as means ± SE. Differences between groups were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

PA reduced β-AR responsiveness in cardiomyocytes.

To determine whether lipids could directly affect β-AR responsiveness in cardiomyocytes, we treated AC-16 cells with 0.4 mM PA or OA along with 1% BSA (molecular ratio LCFA/BSA = 2.64). Both LCFA increased intracellular TG content (Fig. 1A); PA increased TG eightfold, and OA increased TG 10.4-fold (Fig. 1B). Intracellular nonesterified fatty acids increased 5.9-fold with both PA and OA (Fig. 1C). As expected, PA addition increased palmitoyl-CoA, and OA increased oleoyl-CoA levels in the cells, whereas combination of PA and OA increased both palmitoyl- and oleoyl-CoA levels (Supplemental Fig. S1).

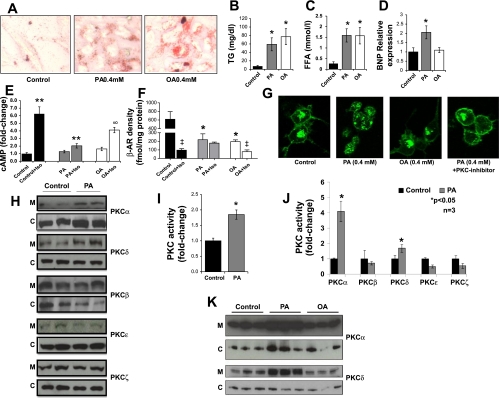

Fig. 1.

Treatment of cardiomyocytes with long-chain fatty acids (LCFA) alters β-adrenergic receptor (β-AR) function, heart failure marker gene expression, and PKC activity. A: Oil Red O staining of AC-16 cells treated with 0.4 mM palmitic acid (PA) or oleic acid (OA) for 14 h. B and C: triglyceride (TG; B) and free fatty acid (FFA; C) levels in OA- and PA-treated AC-16 cells. D: brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) mRNA levels determined by quantitative real-time (qRT)-PCR analysis; n = 7. *P < 0.01 compared with cells that were not treated with LCFA. E: cAMP levels in LCFA-treated cells stimulated with 100 nM isoproterenol for 15 min; n = 6. **P < 0.005 compared with cells that were not stimulated with isoproterenol. ∞P < 0.001 compared with cells that were treated with PA and stimulated with isoproterenol; 1-fold corresponds to 5.4 nM cAMP. F: β-AR density on plasma membrane preparations in baseline and stimulated conditions (100 nM isoproterenol, 15 min); n = 3, *P < 0.05 compared with cells that were not treated with LCFA; ‡P < 0.05 compared with cells that were not stimulated with isoproterenol. G: β-AR distribution in OA- and PA- ± PKC inhibitor-treated (Ro-31-8220, 5 μM, 14 h) GFP-β2AR cells as monitored by confocal microscopy. H: Western blots of PKCα, PKCβ, PKCδ, PKCϵ, and PKCζ protein levels in membrane (M) and cytosolic (C) fractions obtained from PA-treated AC-16 cells. I and J: total (I) and isoform-specific (J) PKC activity in AC-16 cells treated with 0.4 mM PA for 14 h; n = 3, P < 0.05 compared with control cells. K: Western blots of PKCα and PKCδ protein in membrane (M) and cytosolic (C) fractions obtained from PA- or OA-treated AC-16 cells.

Although both LCFA increased neutral lipid accumulation within the cells, only PA increased the expression of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), a marker of heart failure, by 94% (Fig. 1D). Similarly, only PA treatment reduced isoproterenol-stimulated cell lysate cAMP production by 67% (Fig. 1E). This observation indicates that the PA-induced defect in β-AR function did not correlate with TG accumulation. Stimulation of the AC-16 cells with forskolin, an adenyl cyclase activator, for 15 min profoundly increased cAMP levels in PA-treated and untreated cells (Supplemental Fig. S2), attributing reduced β-AR responsiveness to a defect of the receptor rather than downstream signaling molecules.

PA treatment alters β-AR cell surface density and leads to abnormal receptor distribution.

Treatment of AC-16 cells with PA and OA reduced basal β-AR density by 59 and 68%, respectively (Fig. 1F). Ligand-dependent internalization of β-AR following isoproterenol stimulation markedly decreased β-AR density in control AC-16 cells (84%). Isoproterenol treatment also decreased β-AR density in OA-treated cells (60%). In contrast, isoproterenol did not decrease β-AR density in PA-treated AC-16 cells. Thus, receptor trafficking was defective with PA but not OA.

Because β-ARs cannot be visualized in cardiomyocytes, we studied HEK-293 cells with GFP-tagged β2-ARs. Consistent with the radioligand binding assay, both PA and OA treatments reduced cell surface β-ARs. However, only PA treatment compromised intracellular sequestration of the GFP-tagged β-AR (Fig. 1G).

PKCα and PKCδ are activated in PA-treated AC-16 cells.

Western blots of membrane fractions from PA-treated AC-16 cells showed that PKCα and PKCδ, but not PKCβ, PKCϵ, or PKCζ, were increased (Fig. 1H and Supplemental Fig. S3). Total PKC activity increased 70% in PA-treated cells (Fig. 1I). As expected, increased membrane-bound PKCα and PKCδ protein levels were associated with greater PKCα and PKCδ activity (Fig. 1J). On the other hand, membrane-bound PKCα and PKCδ levels were not affected in OA-treated AC-16 cells (Fig. 1K).

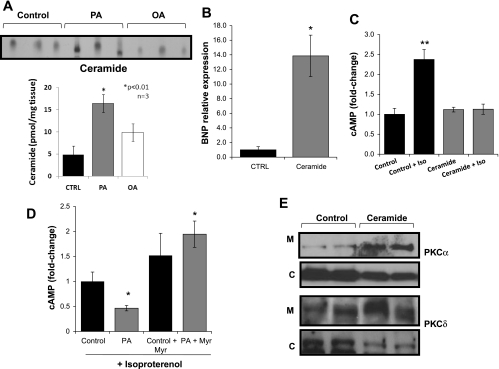

Ceramide inhibits β-AR responsiveness to isoproterenol and triggers PKCα and PKCδ translocation to the membrane.

Treatment of AC-16 cells with PA increased ceramide levels 3.4-fold, whereas OA treatment caused a smaller increase (2-fold) (Fig. 2A). These levels of ceramide (Fig. 2A) do not exceed those found in lipotoxic hearts (34, 44). Treatment of AC-16 cells with 10 μM C6 ceramide (N-hexanoyl-d-erythro-sphingosine) increased BNP expression levels 13.9-fold (Fig. 2B) and eliminated the cellular cAMP response to isoproterenol (Fig. 2C). Myriocin, an inhibitor of serine palmitoyltransferase that catalyzes the rate-limiting step of de novo ceramide biosynthesis (26), improved β-AR responsiveness to isoproterenol in PA-treated cells (Fig. 2D). cAMP levels also tended to increase in cells treated with myriocin alone. Western blots of membrane and cytosolic fractions from ceramide-treated AC-16 cells showed that translocation of both PKCα and PKCδ was increased, as were the membrane/cytosolic PKCα and PKCδ ratios (Fig. 2E and Supplemental Fig. S4).

Fig. 2.

Role of ceramide in PA-mediated lipotoxicity in AC-16 cells. A: ceramide levels determined by diacylglycerol kinase assay in lipid extracts from control (CTRL) and 0.4 mM PA- and 0.4 mM OA-treated cells for 14 h. Control cells were treated with methanol. B: BNP mRNA levels determined by qRT-PCR analysis in cells treated with 10 μM of C6 ceramide for 14 h; n = 4. *P < 0.05. C: intracellular cAMP levels in AC-16 cells treated with 10 μM of C6 ceramide for 14 h and stimulated with 100 nM isoproterenol for 15 min; n = 6. **P < 0.01; 1-fold corresponds to 15.5 nM cAMP. D: intracellular cAMP levels in isoproterenol-stimulated AC-16 cells treated with 0.4 mM PA + 0.2 μM myriocin for 14 h and stimulated with 100 nM isoproterenol for 15 min; n = 6. *P < 0.05 compared with control cells that were not treated with LCFA and myriocin; 1-fold corresponds to 23.0 nM cAMP. E: Western blots of PKCα and PKCδ in membrane and cytosolic fractions of AC-16 cells treated with 10 μM C6 ceramide.

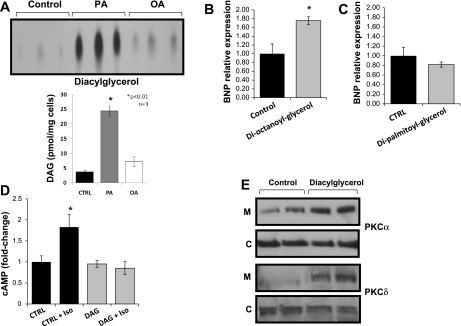

DAG also compromised β-AR sensitivity.

Treatment of AC-16 cells with PA also increased DAG accumulation 6.3-fold (Fig. 3A); the levels of DAG (Fig. 3A) do not exceed those found in lipotoxic hearts (34, 44). Treatment of cells with 1,2-dioctanoyl-sn-glycerol increased BNP mRNA 76% (Fig. 3B), whereas similar treatment with 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycerol, which does not enter the cells (15, 46), did not affect BNP levels (Fig. 3C). 1,2-Dioctanoyl-sn-glycerol treatment resulted in complete lack of responsiveness of the β-AR to isoproterenol (Fig. 3D) and increased membrane-bound PKCα and PKCδ (Fig. 3E and Supplemental Fig. S5).

Fig. 3.

Role of diacylglycerol (DAG) in PA-mediated lipotoxicity in AC-16 cells. A: DAG levels determined by DAG kinase assay in lipid extracts from cells treated with 0.4 mM PA or OA for 14 h. Control cells were treated with methanol. B and C: BNP mRNA levels in AC-16 cells treated with 100 μM dioctanoylglycerol for 14 h; n = 4. P < 0.05 (B) or dipalmitoylglycerol; n = 4 (C). Control cells were treated with DMSO. D: intracellular cAMP levels in AC-16 cells treated with 100 μM dioctanoylglycerol for 14 h and stimulated with 100 nM isoproterenol for 15 min. Control cells were treated with DMSO; n = 6. P < 0.05 compared with cells that were not stimulated with isoproterenol; 1-fold corresponds to 14.0 M cAMP. E: Western blots of PKCα and PKCδ protein levels in membrane and cytosolic fractions obtained from AC-16 cells treated with 100 μM dioctanoylglycerol. Control cells were treated with DMSO. *P < 0.01.

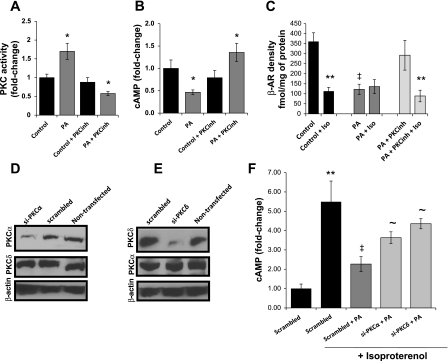

PKC pathway mediates the effects of lipotoxicity on β-AR function.

PKC activation was inhibited when AC16 cells were incubated with a combination of PA and Ro-31-8220, a general PKC-inhibitor (Fig. 4A). The PKC inhibitor treatment of PA-treated cells increased isoproterenol-stimulated intracellular cAMP 2.9-fold (Fig. 4B), reduced membrane-associated PKCs, and normalized cell surface levels and distribution of β-ARs (Figs. 1G and 4C). siRNA inhibition of PKCα or PKCδ expression increased cAMP levels by 59 and 92%, respectively (Fig. 4, D–F).

Fig. 4.

Role of PKCs in the lipid-driven impairment of β-AR function in AC-16 cells A: total PKC activity in AC-16 cells treated with 0.4 mM PA for 14 h and 5 μM Ro-31-8220 [PKC inhibitor (PKCinh)]; n = 6. P < 0.05 compared with control cells that were treated neither with PA nor with PKCinh. B and C: cAMP levels (B) and membrane β-AR density (C) in AC-16 cells treated with 0.4 mM PA and 5 μM PKCinh for 14 h and then stimulated with 100 nM isoproterenol for 15 min; n = 6. P < 0.05 compared with cells that were not treated with PA; n = 3. **P < 0.05 compared with cells that were not stimulated with isoproterenol and ‡P < 0.05 compared with cells that were not treated with LCFA; 1-fold corresponds to 23.0 nM cAMP. D and E: Western blots of PKCα, PKCδ, and β-actin total protein levels obtained from AC-16 cells treated with 50 nM siRNA oligos that target PKCα (D) or PKCδ (E). Nontransfected cells and cells treated with scrambled siRNA oligos were used as controls. F: intracellular cAMP levels in AC-16 cells transfected with 50 nM siRNA oligos that target PKCα or PKCδ, treated with 0.4 mM PA for 14 h and then stimulated with 100 nM isoproterenol for 15 min. Control cells were treated with methanol and scrambled siRNA; n = 6. *P < 0.05 compared with control cells; **P < 0.05 compared with cells that were not stimulated with isoproterenol; ‡P < 0.05 compared with cells that were not treated with LCFA; ∼P < 0.05 compared with cells treated with scrambled siRNA and PA; 1-fold corresponds to 4.8 nM cAMP.

PA inhibits cAMP production in primary cardiomyocytes.

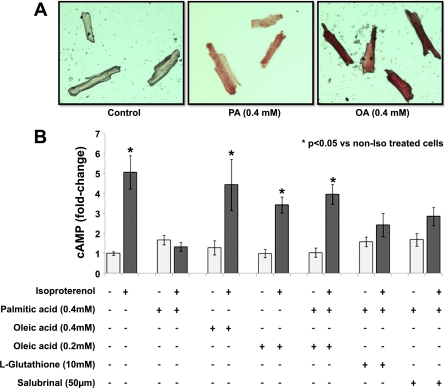

Treatment of adult rat primary cardiomyocytes with either 0.4 mM PA or 0.4 mM OA increased neutral lipid accumulation, as shown by Oil Red O staining (Fig. 5A). However, PA but not OA reduced β-AR responsiveness to isoproterenol, as shown by cAMP production (Fig. 5B). This was not altered by supplementation of PA with either glutathione or salubrinal, inhibitors of oxidative stress (40) and ER stress-mediated apoptosis (5), respectively (Fig. 5B). However, combined treatment of the cells with 0.4 mM of PA and 0.2 mM of OA restored β-AR responsiveness to isoproterenol (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Impaired β-AR responsiveness in isolated adult rat primary cardiomyocytes. A: rat primary cardiomyocytes were treated for 14 h with 0.4 mM PA or OA and then stained with Oil Red O. Control cells were treated with methanol. B: intracellular cAMP levels in primary cardiomyocytes treated with LCFA, 10 mM l-glutathione, or 50 μM salubrinal and stimulated with 100 nM isoproterenol for 15 min; n = 6. *P < 0.05 compared with cells that were not treated with LCFA; 1-fold corresponds to 1.5 nM cAMP.

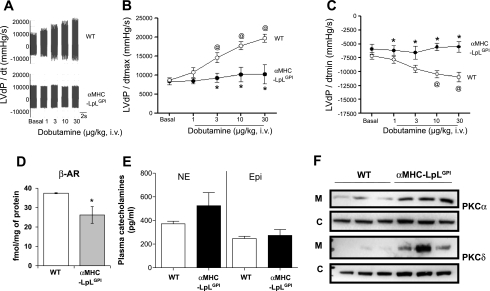

α-MHC-LpLGPI hearts show reduced response to β-AR agonist.

Hearts from α-MHC-LpLGPI mice were studied at baseline and after stimulation with increasing doses of the β-AR agonist dobutamine. These mice accumulate lipids in their hearts, whereas plasma lipids are normal (67). Cardiac fatty acyl-CoAs measured by LC-MS/MS in these mice compared with littermate controls showed similar fatty acyl-CoA distribution (Supplemental Fig. S6). Cardiac performance in a wild-type (WT) and α-MHC-LpLGPI mouse is shown as LVdP/dt [the 1st-order derivative of the left ventricular pressure (LVP) waveform] in Fig. 6. Surprisingly, 4-mo-old α-MHC-LpLGPI mice with no baseline heart dysfunction by either echocardiography (Supplemental Fig. S6) or direct catheterization (baseline data in Fig. 6, A and B) failed to respond to increasing doses of dobutamine (Fig. 6, A and B). Moreover, lusitropic response, the ability of the myocardium to relax in response to dobutamine, was impaired in those mice (Fig. 6C) compared with the WT mouse. Nine-month-old α-MHC-LpLGPI mice with heart dysfunction, as expected, failed to respond to the dobutamine (Supplemental Fig. S7).

Fig. 6.

Impaired β-AR responsiveness to dobutamine in lipotoxic hearts of mice expressing specifically in cardiomyocytes a GPI-anchored lipoprotein lipase [α-myosin heavy chain (MHC)-LpLGPI]. A: LVdP/dt (1st-order derivative of the left ventricular pressure waveform) recording in response to increasing doses of dobutamine in 4-mo-old wild type (WT) and α-MHC-LpLGPI mice. Dobutamine was injected via the femoral vein every 1–2 min, and the LVP waveform was recorded via a pressure transducer/catheter in the left ventricle; n = 4/genotype. B: LVdP/dt max as an index of cardiac contractility to increasing doses of dobutamine in 4-mo-old WT and α-MHC-LpLGPI mice. Data computation was achieved using the PowerLab Software; n = 4/genotype. C: LVdP/dt min as an index of myocardial relaxation to increasing doses of dobutamine in 4-mo-old WT control and α-MHC-LpLGPI mice; n = 4/genotype. D: membrane β-AR density in 4-mo-old WT and α-MHC-LpLGPI hearts measured by saturation-ligand binding assay; n = 4–5/genotype. E: mouse plasma norepinephrine (NE) and epinephrine (Epi) levels measured by ELISA after a 4-h fast; n = 6–7. F: Western blots of PKCα and PKCδ in the membrane and cytosolic fractions of hearts of 4-mo-old WT and α-MHC-LpLGPI mice; n = 3/genotype.

α-MHC-LpLGPI mouse hearts have reduced β-AR density.

Saturation ligand-binding assay in membrane fractions isolated from hearts of 4-mo-old α-MHC-LpLGPI mice showed that β-ARs were reduced by 30% compared with littermate control mice (Fig. 6D). Plasma Epi and NE levels were not increased in α-MHC-LpLGPI mice (Fig. 6E).

α-MHC-LpLGPI hearts have increased membrane-bound PKCα and PKCδ levels.

We found increased membrane-associated PKCα and PKCδ in the α-MHC-LpLGPI hearts compared with WT (Fig. 6F and Supplemental Fig. S8). Cytosolic PKCα was not significantly altered in α-MHC-LpLGPI hearts, whereas cytosolic PKCδ was increased (Fig. 6F and Supplemental Fig. S8). Thus, cardiac lipotoxicity is associated with limited responsiveness to catecholamines that is accompanied by reduced β-AR density and increased membrane-bound PKCα and PKCδ, indicating PKC activation.

Other lipotoxic models also exhibit defective responses to β-AR agonist.

Cardiac-specific overexpression of nuclear receptor PPARγ (55) or ACS (11) results in significant cardiac lipid accumulation, left ventricular dysfunction, and premature death. Since we observed defective β-adrenergic response in the α-MHC-LpLGPI hearts, we next determined whether this defect occurs in other cardiac lipotoxic models. Impairment in the contractile response to increasing doses of dobutamine was found in both the α-MHC-PPARγ (Fig. 7A) and α-MHC-ACS (Fig. 7B) models. The difference was not as profound in the α-MHC-ACS mice (FVB) compared with the α-MHC-LpLGPI and α-MHC-PPARγ (C57BL/6) mice, which may be attributable to differences between the C57BL/6 and FVB background strains (32). Moreover, high-fat-fed mice also exhibited a blunted response to increasing doses of dobutamine similar to the genetic models of cardiac lipotoxicity compared with the chow-fed controls (Fig. 7C).

Fig. 7.

Impaired β-AR responsiveness in in hearts of mice expressing specifically in cardiomyocytes a GPI-anchored peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (α-MHC-PPARγ) or acyl-CoA synthetase (α-MHC-ACS) and high-fat-fed C57BL/6 mice. A–C: LVdP/dt max as an index of cardiac contractility to increasing doses of dobutamine, 1–30 μg/kg, α-MHC-PPARγ and control C57BL/6 littermate mice (A), α-MHC-ACS and control FVB littermate mice (B), or high-fat- and chow-fed C57BL/6 mice (chow: 32.5 ± 0.6 g, HFD: 53.7 ± 1.1 g; C). PowerLab Software was used for data computation; n = 4/genotype. *P < 0.05 compared with WT, P < 0.05 compared with WT basal. D–F: Western blots of PKCα and PKCδ protein levels in the membrane and cytosolic fractions obtained from cardiac tissue of WT and α-MHC-PPARγ (D), α-MHC-ACS (E), or high-fat-fed mice (F).

Western blots of proteins isolated from cardiac tissue showed activation of PKC in α-MHC-PPARγ, α-MHC-ACS, and high-fat-fed mouse hearts. However, they differed in that membrane PKCδ was increased in the α-MHC-PPARγ (Fig. 7D and Supplemental Fig. S9), whereas membrane-associated PKCα was increased in α-MHC-ACS hearts (Fig. 7E and Supplemental Fig. S9). Protein analysis for hearts obtained from high-fat-fed mice showed significant activation of PKCα (Fig. 7F and Supplemental Fig. S9).

DISCUSSION

Intracellular lipid accumulation leads to a number of detrimental effects, such as alterations in insulin signaling (10, 50), endopasmic reticulum stress (3, 60), apoptosis (11, 25, 57), and mitochondrial dysfunction (51). Hearts are the most energy-requiring organ of the body and normally rely on lipids for their major source of energy (58). However, when lipids accumulate in the heart they can lead to heart dysfunction and premature death (27, 66). The causes of cardiac dysfunction in lipotoxicities are unclear. LCFA, particularly PA, are considered to be a more potent cause of lipotoxicity than unsaturated LCFA, such as OA. This has been attributed to the accumulation of either DAG (10, 68) or ceramide (10, 42) and/or other lipids (56). We hypothesized that lipid-mediated abnormalities in cellular pathways would alter the normal physiological responses to stress. Indeed, our data show that intracellular lipid accumulation inhibits normal β-AR signaling. This appears to be via stimulation of PKCs, leading to reduced numbers and defective internalization of β-ARs. Moreover, these abnormal cellular processes were found in several models of lipotoxic heart disease.

We used cardiomyocytes to prove that β-AR function is compromised by lipids and that this occurs via activation of PKCs. PA treatment of AC-16 cells, derived from human ventricular cardiomyocytes (14), and adult rat primary cardiomyocytes reduced isoproterenol-induced cAMP production, the downstream read out of β-AR activation. OA addition prevented PA-induced β-AR insensitivity. This is thought to be due to greater incorporation of PA into TG rather than its conversion to other more toxic lipids (33, 37). Ligand-binding assays in AC-16 cells and confocal microscopy of GFP-tagged β2-AR HEK-293 cells (39) showed that PA-treated cells had reduced cell surface β-AR density and defective ligand-dependent internalization.

β-ARs are members of the G protein-coupled receptor family. Reduced β-AR activity can occur due to a reduction in β-ARs or reduced signaling because the receptors are inactivated by phosphorylation. GRK2 phosphorylates the β-AR to ignite the homologous desensitization of the receptor. Phosphorylated β-AR dissociates from the G protein complex and undergoes internalization (18, 19, 21, 69). This is a key step required either for β-AR dephosphorylation and resensitization (31) or for its proteasomal degradation (53). Failing hearts demonstrate reduced cardiac β-AR-mediated responsiveness to catecholamines and abnormal myocardial β-AR signaling (8), which coincides with increased production of catecholamines (36). Because α-MHC-LpLGPI mice used for this study did not have increased plasma catecholamines, we questioned whether the β-AR desensitization involved a second process. β-ARs can be desensitized by a ligand-independent cascade that is called heterologous desensitization and is triggered by direct phosphorylation of the receptor by several protein kinases, including PKCs (54). Membrane-associated PKCs were increased in both in vitro and in vivo lipotoxic environments, with reduced β-AR numbers on the membrane and impaired β-AR responsiveness. Furthermore, inhibition of PKC signaling by pharmacological or genetic means restored the presence of the receptor on the membrane and its function. The exact molecule(s) that causes cellular lipotoxicity has not been determined. Saturated FA-induced toxicity may be mediated by intracellular accumulation of either DAG (10, 68) or ceramide (10, 42). Treatment of the AC-16 cells with DAG reproduced the inhibitory effect of PA on β-AR responsiveness to isoproterenol. Treatment of the AC-16 cells with ceramide also reproduced the PA-mediated inhibition of β-AR responsiveness to isoproterenol. Unexpectedly, incubation of PA-treated AC-16 cells with myriocin, a de novo ceramide biosynthesis inhibitor, totally restored the function of the β-AR, as shown by cAMP levels following isoproterenol stimulation. Previous data from our group have shown that myriocin does not reduce DAG levels in lipotoxic hearts (44). The observed complete restoration of β-AR function upon myriocin treatment may be due to inhibitory effects of myriocin on PKC translocation to the membrane, as has been shown by others (22). Nonetheless, our data suggest that either DAG or ceramide has the potential to disrupt normal β-AR function.

PKCs have been implicated as pathogenic intermediates in lipotoxicity and T2DM. PKCβ is activated in hyperglycemia and might be responsible for several diabetes complications (2). PKCϵ has been associated with proapoptotic signaling when upregulated in cardiomyocytes (13). The most analogous defect to that in the heart is skeletal muscle insulin signaling inhibition by PKCθ, a process initiated by excess myocellular DAG (28). PKCα, PKCδ, PKCϵ, PKCζ, and PKCη are expressed in cardiomyocytes (30). Among these isoforms, PKCα and PKCδ were activated in PA-treated AC-16 cells. Using a nonspecific PKC inhibitor, we abrogated the PA-mediated reduction in β-ARs and the defective isoproterenol-induced cAMP production. Moreover, siRNA inhibition of either PKCα or PKCδ ameliorated the defect. Thus, both PKCα and PKCδ are mediators of lipid-induced impairment of β-AR responsiveness to catecholamines.

To assess whether cardiac lipid-mediated inhibition of β-AR function occurs in vivo, responsiveness to dobutamine was studied in three genetically engineered cardiolipotoxic mice, α-MHC-LpLGPI, α-MHC-PPARγ, and α-MHC-ACS. These mouse models have been shown to have elevated cardiac ceramide and DAG levels (34, 44, 55). These genetic animal models of normal, or almost normal in the case of the α-MHC-ACS mice, basal heart function as well as high-fat-fed C57BL/6 mice reproduced defective contractility following increasing dobutamine doses. The activated PKC isoform differed in these models. Thus, the type of lipid or its intracellular localization might lead to defects via different members of the PKC family.

T2DM and obesity are associated with increased lipid accumulation in the heart and reduced cardiac function, which eventually results in heart failure (61, 66). In addition to defective heart mechanics, abnormalities in regulation of heart rhythms are a major risk factor for adverse outcomes (62). Failing hearts demonstrate reduced cardiac β-AR-mediated responsiveness to catecholamines and abnormal myocardial β-AR signaling (9, 65). This defect is mitigated by the use of β-blockers, which prevent catecholamine-mediated β-AR desensitization in heart failure patients. We found another cause of cardiac adrenergic dysfunction that might be present in patients with T2DM and metabolic syndrome. Lipotoxic hearts from several models have increased PKCα and PKCδ activation and defective β-AR responsiveness that predates the development of heart failure.

Defective β-adrenergic signaling alone causes cardiomyopathy (47). β-AR function is crucial in cardiac contractility and response to normal physiological stress, such as during exercise (48). Moreover, human studies suggest that patients with T2DM who are likely to have lipotoxic injury have abnormalities of cardiac rhythm (62). Our data show that cardiac lipid accumulation compromised β-AR responsiveness to catecholamines. This effect may be mediated by both ceramide and DAG. Activation of PKCα and PKCδ is associated with defective β-AR function, and inhibition of PKCs improved the responsiveness of the receptor. These data implicate PKCs as suitable targets for the treatment of cardiac dysfunction in obese and diabetic individuals. Moreover, our studies suggest a common pathological process, lipid induction of PKCs, as a cause of cellular dysfunction in lipotoxicity.

GRANTS

This study was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants HL-45095 and HL-73029 (I. J. Goldberg) and HL-085503, HL-061690, and P01-HL-075443 (Project 2; W. J. Koch). K. Drosatos was supported by an American Diabetes Association-mentored postdoctoral grant and a postdoctoral grant of the American Heart Association (AHA No. 10POST4440032). A. Lymperopoulos was supported by a Scientist Development Grant from the American Heart Association (AHA No. 09SDG2010138, National Center).

DISCLOSURES

The authors have no conflicts of interest related to the work in this article.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. John P. Morrow and Chad Trent for providing us with adult rat primary cardiomyocytes, Dr. Mercy M. Davidson for the AC-16 cells, and Dr. Graeme Milligan for giving us the GFP-β2AR cells.

REFERENCES

- 1. Alpert MA. Obesity cardiomyopathy: pathophysiology and evolution of the clinical syndrome. Am J Med Sci 321: 225–236, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arikawa E, Ma RC, Isshiki K, Luptak I, He Z, Yasuda Y, Maeno Y, Patti ME, Weir GC, Harris RA, Zammit VA, Tian R, King GL. Effects of insulin replacements, inhibitors of angiotensin, and PKCbeta's actions to normalize cardiac gene expression and fuel metabolism in diabetic rats. Diabetes 56: 1410–1420, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Borradaile NM, Buhman KK, Listenberger LL, Magee CJ, Morimoto ET, Ory DS, Schaffer JE. A critical role for eukaryotic elongation factor 1A-1 in lipotoxic cell death. Mol Biol Cell 17: 770–778, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Boudina S, Abel ED. Diabetic cardiomyopathy revisited. Circulation 115: 3213–3223, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Boyce M, Bryant KF, Jousse C, Long K, Harding HP, Scheuner D, Kaufman RJ, Ma D, Coen DM, Ron D, Yuan J. A selective inhibitor of eIF2alpha dephosphorylation protects cells from ER stress. Science 307: 935–939, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Braz JC, Gregory K, Pathak A, Zhao W, Sahin B, Klevitsky R, Kimball TF, Lorenz JN, Nairn AC, Liggett SB, Bodi I, Wang S, Schwartz A, Lakatta EG, DePaoli-Roach AA, Robbins J, Hewett TE, Bibb JA, Westfall MV, Kranias EG, Molkentin JD. PKC-alpha regulates cardiac contractility and propensity toward heart failure. Nat Med 10: 248–254, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brehm A, Krssak M, Schmid AI, Nowotny P, Waldhausl W, Roden M. Acute elevation of plasma lipids does not affect ATP synthesis in human skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 299: E33–E38, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bristow MR, Ginsburg R, Minobe W, Cubicciotti RS, Sageman WS, Lurie K, Billingham ME, Harrison DC, Stinson EB. Decreased catecholamine sensitivity and beta-adrenergic-receptor density in failing human hearts. N Engl J Med 307: 205–211, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bristow MR, Hershberger RE, Port JD, Gilbert EM, Sandoval A, Rasmussen R, Cates AE, Feldman AM. Beta-adrenergic pathways in nonfailing and failing human ventricular myocardium. Circulation 82: I12–I25, 1990 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chavez JA, Summers SA. Characterizing the effects of saturated fatty acids on insulin signaling and ceramide and diacylglycerol accumulation in 3T3-L1 adipocytes and C2C12 myotubes. Arch Biochem Biophys 419: 101–109, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chiu HC, Kovacs A, Ford DA, Hsu FF, Garcia R, Herrero P, Saffitz JE, Schaffer JE. A novel mouse model of lipotoxic cardiomyopathy. J Clin Invest 107: 813–822, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Connelly KA, Kelly DJ, Zhang Y, Prior DL, Advani A, Cox AJ, Thai K, Krum H, Gilbert RE. Inhibition of protein kinase C-beta by ruboxistaurin preserves cardiac function and reduces extracellular matrix production in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Circ Heart Fail 2: 129–137, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Crow MT. Beta-adrenergic receptor signaling pathways mediating cell survival in cardiomyocytes: a role for PKC epsilon inhibition? J Mol Cell Cardiol 34: 1121–1125, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Davidson MM, Nesti C, Palenzuela L, Walker WF, Hernandez E, Protas L, Hirano M, Isaac ND. Novel cell lines derived from adult human ventricular cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol 39: 133–147, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Davis RJ, Ganong BR, Bell RM, Czech MP. sn-1,2-Dioctanoylglycerol. A cell-permeable diacylglycerol that mimics phorbol diester action on the epidermal growth factor receptor and mitogenesis. J Biol Chem 260: 1562–1566, 1985 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dorn GW, 2nd, Molkentin JD. Manipulating cardiac contractility in heart failure: data from mice and men. Circulation 109: 150–158, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Farese RV, Sajan MP, Yang H, Li P, Mastorides S, Gower WR, Jr, Nimal S, Choi CS, Kim S, Shulman GI, Kahn CR, Braun U, Leitges M. Muscle-specific knockout of PKC-lambda impairs glucose transport and induces metabolic and diabetic syndromes. J Clin Invest 117: 2289–2301, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ferguson SS, Downey WE, 3rd, Colapietro AM, Barak LS, Ménard L, Caron MG. Role of beta-arrestin in mediating agonist-promoted G protein-coupled receptor internalization. Science 271: 363–366, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gagnon AW, Kallal L, Benovic JL. Role of clathrin-mediated endocytosis in agonist-induced down-regulation of the beta2-adrenergic receptor. J Biol Chem 273: 6976–6981, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Geraldes P, Hiraoka-Yamamoto J, Matsumoto M, Clermont A, Leitges M, Marette A, Aiello LP, Kern TS, King GL. Activation of PKC-delta and SHP-1 by hyperglycemia causes vascular cell apoptosis and diabetic retinopathy. Nat Med 15: 1298–1306, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Goodman OB, Jr, Krupnick JG, Santini F, Gurevich VV, Penn RB, Gagnon AW, Keen JH, Benovic JL. Beta-arrestin acts as a clathrin adaptor in endocytosis of the beta2-adrenergic receptor. Nature 383: 447–450, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gopee NV, Sharma RP. Selective and transient activation of protein kinase C alpha by fumonisin B1, a ceramide synthase inhibitor mycotoxin, in cultured porcine renal cells. Life Sci 74: 1541–1559, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Guimond J, Mamarbachi AM, Allen BG, Rindt H, Hebert TE. Role of specific protein kinase C isoforms in modulation of beta1- and beta2-adrenergic receptors. Cell Signal 17: 49–58, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hambleton M, Hahn H, Pleger ST, Kuhn MC, Klevitsky R, Carr AN, Kimball TF, Hewett TE, Dorn GW, 2nd, Koch WJ, Molkentin JD. Pharmacological- and gene therapy-based inhibition of protein kinase Calpha/beta enhances cardiac contractility and attenuates heart failure. Circulation 114: 574–582, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hickson-Bick DL, Buja ML, McMillin JB. Palmitate-mediated alterations in the fatty acid metabolism of rat neonatal cardiac myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol 32: 511–519, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Horvath A, Sutterlin C, Manning-Krieg U, Movva NR, Riezman H. Ceramide synthesis enhances transport of GPI-anchored proteins to the Golgi apparatus in yeast. EMBO J 13: 3687–3695, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Khan RS, Drosatos K, Goldberg IJ. Creating and curing fatty hearts. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 13: 145–149, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kim JK, Fillmore JJ, Sunshine MJ, Albrecht B, Higashimori T, Kim DW, Liu ZX, Soos TJ, Cline GW, O'Brien WR, Littman DR, Shulman GI. PKC-theta knockout mice are protected from fat-induced insulin resistance. J Clin Invest 114: 823–827, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kohout TA, Lefkowitz RJ. Regulation of G protein-coupled receptor kinases and arrestins during receptor desensitization. Mol Pharmacol 63: 9–18, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kohout TA, Rogers TB. Use of a PCR-based method to characterize protein kinase C isoform expression in cardiac cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 264: C1350–C1359, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Krueger KM, Daaka Y, Pitcher JA, Lefkowitz RJ. The role of sequestration in G protein-coupled receptor resensitization. Regulation of beta2-adrenergic receptor dephosphorylation by vesicular acidification. J Biol Chem 272: 5–8, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Li Q, Fang CX, Nunn JM, Zhang J, LaCour KH, Ren J. Characterization of cardiomyocyte excitation-contraction coupling in the FVB/N-C57BL/6 intercrossed “chocolate” brown mice. Life Sci 80: 187–192, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Listenberger LL, Han X, Lewis SE, Cases S, Farese RV, Jr, Ory DS, Schaffer JE. Triglyceride accumulation protects against fatty acid-induced lipotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 3077–3082, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liu L, Shi X, Bharadwaj KG, Ikeda S, Yamashita H, Yagyu H, Schaffer JE, Yu YH, Goldberg IJ. DGAT1 expression increases heart triglyceride content but ameliorates lipotoxicity. J Biol Chem 284: 36312–36323, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Liu Q, Chen X, Macdonnell SM, Kranias EG, Lorenz JN, Leitges M, Houser SR, Molkentin JD. Protein kinase C{alpha}, but not PKC{beta} or PKC{gamma}, regulates contractility and heart failure susceptibility: implications for ruboxistaurin as a novel therapeutic approach. Circ Res 105: 194–200, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lymperopoulos A, Rengo G, Funakoshi H, Eckhart AD, Koch WJ. Adrenal GRK2 upregulation mediates sympathetic overdrive in heart failure. Nat Med 13: 315–323, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Maedler K, Oberholzer J, Bucher P, Spinas GA, Donath MY. Monounsaturated fatty acids prevent the deleterious effects of palmitate and high glucose on human pancreatic beta-cell turnover and function. Diabetes 52: 726–733, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Magnes C, Suppan M, Pieber TR, Moustafa T, Trauner M, Haemmerle G, Sinner FM. Validated comprehensive analytical method for quantification of coenzyme A activated compounds in biological tissues by online solid-phase extraction LC/MS/MS. Anal Chem 80: 5736–5742, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. McLean AJ, Milligan G. Ligand regulation of green fluorescent protein-tagged forms of the human beta(1)- and beta(2)-adrenoceptors; comparisons with the unmodified receptors. Br J Pharmacol 130: 1825–1832, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Meister A, Anderson ME. Glutathione. Annu Rev Biochem 52: 711–760, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. O'Connell TD, Rodrigo MC, Simpson PC. Isolation and culture of adult mouse cardiac myocytes. Methods Mol Biol 357: 271–296, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Okere IC, Chandler MP, McElfresh TA, Rennison JH, Sharov V, Sabbah HN, Tserng KY, Hoit BD, Ernsberger P, Young ME, Stanley WC. Differential effects of saturated and unsaturated fatty acid diets on cardiomyocyte apoptosis, adipose distribution, and serum leptin. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291: H38–H44, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Palaniyandi SS, Inagaki K, Mochly-Rosen D. Mast cells and epsilonPKC: a role in cardiac remodeling in hypertension-induced heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol 45: 779–786, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Park TS, Hu Y, Noh HL, Drosatos K, Okajima K, Buchanan J, Tuinei J, Homma S, Jiang XC, Abel ED, Goldberg IJ. Ceramide is a cardiotoxin in lipotoxic cardiomyopathy. J Lipid Res 49: 2101–2112, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Perry DK, Bielawska A, Hannun YA. Quantitative determination of ceramide using diglyceride kinase. Methods Enzymol 312: 22–31, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pessin MS, Raben DM. Molecular species analysis of 1,2-diglycerides stimulated by alpha-thrombin in cultured fibroblasts. J Biol Chem 264: 8729–8738, 1989 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Port JD, Bristow MR. Altered beta-adrenergic receptor gene regulation and signaling in chronic heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol 33: 887–905, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ross J, Jr, Miura T, Kambayashi M, Eising GP, Ryu KH. Adrenergic control of the force-frequency relation. Circulation 92: 2327–2332, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sakaki K, Wu J, Kaufman RJ. Protein kinase Ctheta is required for autophagy in response to stress in the endoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem 283: 15370–15380, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Samuel VT, Petersen KF, Shulman GI. Lipid-induced insulin resistance: unravelling the mechanism. Lancet 375: 2267–2277, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Schrauwen P, Schrauwen-Hinderling V, Hoeks J, Hesselink MK. Mitochondrial dysfunction and lipotoxicity. Biochim Biophys Acta 1801: 266–271, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Sharma S, Adrogue JV, Golfman L, Uray I, Lemm J, Youker K, Noon GP, Frazier OH, Taegtmeyer H. Intramyocardial lipid accumulation in the failing human heart resembles the lipotoxic rat heart. FASEB J 18: 1692–1700, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Shenoy SK, McDonald PH, Kohout TA, Lefkowitz RJ. Regulation of receptor fate by ubiquitination of activated beta 2-adrenergic receptor and beta-arrestin. Science 294: 1307–1313, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sibley DR, Lefkowitz RJ. Beta-adrenergic receptor-coupled adenylate cyclase. Biochemical mechanisms of regulation. Mol Neurobiol 1: 121–154, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Son NH, Park TS, Yamashita H, Yokoyama M, Huggins LA, Okajima K, Homma S, Szabolcs MJ, Huang LS, Goldberg IJ. Cardiomyocyte expression of PPARgamma leads to cardiac dysfunction in mice. J Clin Invest 117: 2791–2801, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Son NH, Yu S, Tuinei J, Arai K, Hamai H, Homma S, Shulman GI, Abel ED, Goldberg IJ. PPARgamma-induced cardiolipotoxicity in mice is ameliorated by PPARalpha deficiency despite increases in fatty acid oxidation. J Clin Invest 120: 3443–3454, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Sparagna GC, Hickson-Bick DL, Buja LM, McMillin JB. A metabolic role for mitochondria in palmitate-induced cardiac myocyte apoptosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 279: H2124–H2132, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Taegtmeyer H, McNulty P, Young ME. Adaptation and maladaptation of the heart in diabetes: Part I: general concepts. Circulation 105: 1727–1733, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Takuma S, Suehiro K, Cardinale C, Hozumi T, Yano H, Shimizu J, Mullis-Jansson S, Sciacca R, Wang J, Burkhoff D, Di Tullio MR, Homma S. Anesthetic inhibition in ischemic and nonischemic murine heart: comparison with conscious echocardiographic approach. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 280: H2364–H2370, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Turner MD. Fatty acyl CoA-mediated inhibition of endoplasmic reticulum assembly. Biochim Biophys Acta 1693: 1–4, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Unger RH. Lipotoxic diseases. Annu Rev Med 53: 319–336, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Wackers FJ, Young LH, Inzucchi SE, Chyun DA, Davey JA, Barrett EJ, Taillefer R, Wittlin SD, Heller GV, Filipchuk N, Engel S, Ratner RE, Iskandrian AE. Detection of silent myocardial ischemia in asymptomatic diabetic subjects: the DIAD study. Diabetes Care 27: 1954–1961, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wan W, Powers AS, Li J, Ji L, Erikson JM, Zhang JQ. Effect of post-myocardial infarction exercise training on the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and cardiac function. Am J Med Sci 334: 265–273, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Wang CY, Mazer SP, Minamoto K, Takuma S, Homma S, Yellin M, Chess L, Fard A, Kalled SL, Oz MC, Pinsky DJ. Suppression of murine cardiac allograft arteriopathy by long-term blockade of CD40-CD154 interactions. Circulation 105: 1609–1614, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Wang X, Dhalla NS. Modification of beta-adrenoceptor signal transduction pathway by genetic manipulation and heart failure. Mol Cell Biochem 214: 131–155, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Wende AR, Abel ED. Lipotoxicity in the heart. Biochim Biophys Acta 1801: 311–319, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Yagyu H, Chen G, Yokoyama M, Hirata K, Augustus A, Kako Y, Seo T, Hu Y, Lutz EP, Merkel M, Bensadoun A, Homma S, Goldberg IJ. Lipoprotein lipase (LpL) on the surface of cardiomyocytes increases lipid uptake and produces a cardiomyopathy. J Clin Invest 111: 419–426, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Yu C, Chen Y, Cline GW, Zhang D, Zong H, Wang Y, Bergeron R, Kim JK, Cushman SW, Cooney GJ, Atcheson B, White MF, Kraegen EW, Shulman GI. Mechanism by which fatty acids inhibit insulin activation of insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1)-associated phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity in muscle. J Biol Chem 277: 50230–50236, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Zhang J, Ferguson SS, Barak LS, Ménard L, Caron MG. Dynamin and beta-arrestin reveal distinct mechanisms for G protein-coupled receptor internalization. J Biol Chem 271: 18302–18305, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.