Abstract

It has previously been known that transcription of the PGC-1α gene can be either inhibited or stimulated by p38 MAP kinase (p38 MAPK). To determine whether p38 MAPK plays an inhibitory or stimulatory role in PGC-1α gene transcription, we further investigated the role of p38 MAPK in this study. Our results showed that the basal level of p38 MAPK phosphorylation was increased in gastrocnemius of mice under HFD and that p38 MAPK stimulated PGC-1α gene transcription in C2C12 myotubes. Our results also provided new mechanisms in myotubes that the p38 MAPK-induced PGC-1α gene transcription was mediated by CREB. In exploring the role of the Akt-dependent insulin signaling on PGC-1α gene transcription, we found that the basal Akt-dependent signaling was increased in gastrocnemius of mice under HFD. The p38 MAPK-induced PGC-1α gene transcription was prevented by insulin. Insulin suppression of PGC-1α gene transcription was neutralized by overexpression of the constitutively nuclear form of FoxO1. Finally, we located three insulin response elements (IREs) in the PGC-1α promoter, and mutations of these IREs abolish or blunt activity of the PGC-1α promoter. Together, our results show that transcription of the PGC-1α gene is balanced by different intracellular signaling pathways.

Keywords: p38, Akt, insulin, insulin signaling, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1α

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1α (PGC-1α) is a multifaceted transcriptional coactivator. It is expressed in all major tissues/organs that are involved in metabolism, such as brown adipose tissue, liver, and skeletal muscles. In the brown adipose tissue, PGC-1α promotes energy dissipation through upregulating expression of the uncoupling protein-1 gene (35). In the liver, PGC-1α stimulates de novo synthesis of glucose via gluconeogenesis to provide a fuel source for cells (neurons and red blood cells) that can only use glucose as their fuel source (32). In the skeletal muscle, PGC-1α converts the low energy-consuming white muscles into the high energy-consuming red muscles (18, 42). In all these tissues, PGC-1α promotes the production of new mitochondria, the “power house” of a cell (34). Thus, the main function of PGC-1α in metabolism is to burn off the stored energy. Excess energy storage due to overeating and/or lack of physical activity is an equivalent to obesity, which is almost always associated with insulin resistance/hyperinsulinemia. Insulin resistance/hyperinsulinemia in turn is either a precursor or key component of numerous modern health problems such as metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disorders, nonalcoholic fatty liver, Alzheimer's disease, depression, asthma, some cancers, and aging (1, 4, 6, 9, 10, 25, 26, 31, 38). Therefore, a full understanding of PGC-1α gene transcription will certainly help find new ways to prevent and eliminate the excess energy storage and its numerous associated diseases.

It is known that p38 MAPK can stimulate the activity of PGC-1α (8, 33, 41). Additionally, p38 MAPK plays a role in PGC-1α expression. It has been shown that p38 MAPK may mediate the reduced expression of PGC-1α-induced free fatty acids (FFA) in skeletal muscles (11). In contrast, activation of p38 MAPK has been shown to be involved in the exercise-induced expression of the PGC-1α gene in skeletal muscles (2, 40). Furthermore, we have shown previously that both p38 MAPK activity and PGC-1α expression are increased in the brown adipose tissue by cold exposure (8). Considering these opposing results, whether p38 MAPK plays a positive or negative role in PGC-1α gene transcription is still being debated. Besides, the exact mechanism by which p38 MAPK regulates PGC-1α expression has not been fully established.

It is known that the Akt-dependent signaling may inhibit the activity of PGC-1α protein (17). There are indications that the Akt-dependent classical insulin signaling may play an inhibitory role in PGC-1α expression. For example, PGC-1α expression is decreased in skeletal muscles of subjects with insulin resistance/hyperinsulinemia (11, 29). The cold-induced expression of PGC-1α is accompanied by reduced insulin signaling (27). We have shown recently that PGC-1α expression is increased significantly when insulin production is prevented by streptozotocin (24). Our sequence analysis of the PGC-1α promoter identified several putative insulin response elements (IREs) or FoxO binding sites. In this study, we examined roles of the p38 MAPK- and Akt/FoxO1-dependent intracellular signaling pathways in transcription of the PGC-1α gene.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

Antibodies against total/phospho-Akt (Ser473), phospho-FoxO1 (Thr24), phospho-ATF2 (Thr71), phospho-cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB; Ser133), total/phospho-p38 (Thr180/Tyr182), and total/phospho Erk1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204) were from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). The antibodies against PGC-1α (H-300) and α-tubulin (AA12) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). The antibody against laminin receptor (COOH terminus, L1293) was from Sigma-Aldrich (Milwaukee, WI). LY-294002 was from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). Protein assay kits were from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA). Other materials were all obtained commercially and are of analytical quality. The constitutively nuclear form of FoxO1 encoded by adenovirus and the adenoviral vector encoding green fluorescent protein (GFP) were kind gifts from Drs. Domenico Accili and Christopher Newgard, respectively (5, 13). The constitutively activated form of MKK6 (MKK6E) encoded by adenovirus was a gift from Dr. Jiahua Han.

Animal experiments.

C57BL/6 (B6) were housed under the usual day (12 h of daylight) and night (12 h of darkness) circadian and fed ad libitum. Mice were fed with either the normal rodent chow diet (ND) or high-fat diet (HFD) (Research Diets D12330, 58.0 kcal/100 kcal fat, 16.0 kcal/100 kcal proteins, and 26 kcal/100 kcal carbohydrates) for 4 wk. All animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of The Hamner Institutes for Health Sciences and fully complied with the guidelines from the National Institutes of Health. Insulin sensitivity was evaluated by measuring fasting levels of blood glucose and plasma insulin and then calculated by homeostasis model assessment (HOMA), as described previously (20, 21).

Construction of PGC-1α promoter expression vectors.

The plasmids with a 2.6-kb fragment of the mouse PGC-1α promoter in the pGL3-basic vector containing the luciferase reporter gene and cAMP response element (CRE) or myocyte enhancer factor 2 (MEF2) response element (MEF2RE) deletion were purchased from Addgene (Cambridge, MA). The constructs with mutated IREs were constructed by site-directed mutagenesis with QuikChange Site-Directed II Mutagenesis Kit from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA). Primers used for mutagenesis were listed in Supplemental Table S1 (Supplemental Material for this article can be found online at the AJP-Endocrinology and Metabolism web site). Sequences of all constructs were verified by DNA sequencing.

Transient DNA transfections, luciferase assays, and adenoviral infections.

Plasmid DNAs were introduced into cells by lipofectamine 2000 transfection agents. Promoter activities were measured by a luciferase assay system (Promega) with a Wallac 1420 Multilabel Counter (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) and normalized to the activity of pGL3-basic empty vector under the same treatments. Recombinant adenoviruses encoding the nuclear form of FoxO1 (Ad-FoxO1) or the constitutively active form of MKK6 (MKK6E) or GFP (Ad-GFP) were introduced into cells in six-well plates, as described previously (7, 22, 23). The typical infection rate of C2C12 cells under our conditions is 70–80%.

Cell culture and treatments.

C2C12 cells were cultured and differentiated as described previously (15). Briefly, cells were maintained in DMEM containing 10% FBS and 1× antibiotic-antimycotic. When cells reached 90% confluence, recombinant adenoviruses or plasmids were introduced into cells via standard infections or transient transfections. Six hours later, they were switched to DMEM containing 2% horse serum and 1× antibiotic-antimycotic and treated for 24–36 h with either vehicle or target reagents (insulin, SB-203580, or LY294002 as noted).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were conducted using the EZ ChIP Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Kit from Upstate (Lake Placid, NY) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, cells in three 150-mm plates per condition were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature. The reaction was stopped with the addition of glycine solution and then washed with ice-cold 1× PBS. Cells were pooled, precipitated, and then resuspended in cold 1× SDS lysis buffer supplemented with the protease inhibitor cocktail mixture. Cells were then sonicated (6 pulses, 10 s/pulse at 40% power) to break DNA into fragments in the range of 200–1,000 bp. Sheared chromatin samples (100 μl) were incubated with protein G agarose on ice for 1 h and then incubated with anti-acetyl histone H3 antibody (positive control), IgG (negative control), or anti-CREB antisera (P16220; Millipore) and anti-MEF2 antisera (sc-13266x; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) overnight at 4°C. Aliquots of chromatin that was not incubated with an antibody were used as the input sample control. Antibody-bound protein/DNA complexes were washed, eluted, reverse-cross-linked, and treated with proteinase K to digest proteins. The chromatin samples were then used in PCR analyses. Primers amplifying the mouse PGC-1α promoter fragment containing CRE were 5′-AAG CGT TAC TTC ACT GAG GCA GAG G-3′ (forward) and 5′-ACG GCA CACACT CAT GCA GGC AAC C-3′ (reverse), generating a 206-bp product. Primers amplifying the mouse PGC-1α promoter fragment containing MEF2RE were 5′-CGC TGC ATT TCT TTC TTT CAC TTT A-3′ (forward) and 5′-AAC CAG CTC ATT TCC TTT ACT TGA C-3′ (reverse), generating a 229-bp product. PCR products were visualized in 4% agarose gels.

Immunoblotting.

Cells were lysed in Nonidet P-40 (NP-40) lysis buffer [1% NP-40, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 2 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 2 μg/ml leupeptin, and 10 μg/ml aprotinin]. Cell lysates (15 μg/lane total protein or 30 μg/lane for nuclear extracts) were resolved in 4–20% Tris-glycine gels (Invitrogen) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad). After blocking with 5% skim milk (catalog no. 25010602; GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ), the membranes were incubated overnight with primary antibodies. Target proteins were detected by immunoblotting with specific antisera as indicated and alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary antisera. Fluorescent bands were visualized with a Typhoon 9410 variable mode Imager from GE Healthcare and then quantified by densitometry analysis using Image-Quant 5.2 software from Molecular Dynamics (Piscataway, NJ).

RNA extraction and real-time PCR.

Total RNAs were extracted from cells or tissues with an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) and reverse-transcribed into cDNAs, which were then quantified by real-time PCR with specific probes and primers and normalized to levels of 36B4. The oligo sequence for PGC-1α quantification is forward: 5′-AATCAGACC TGACACAACGC-3′; reverse: 5′- GCATTCCTCAATTTCACCAA-3′. The oligo sequence for 36B4 quantification is forward: 5′-GCAGACAACGTGGGCTCCAAGCA GAT-3′; reverse: 5′-GGTCCTCCTTGGTGAACACGAAGCCC-3′.

Statistical analysis.

Data are presented as means ± SE. Data were compared by Student's t-test with GraphPad Prism version 4.0 for Windows (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). Differences at values of P ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

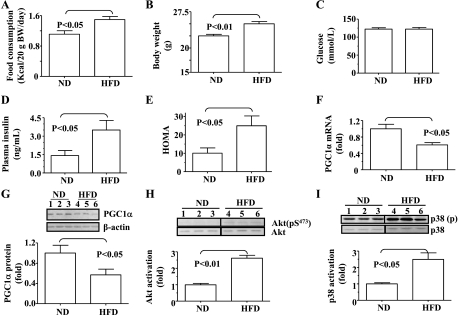

Decreased expression of PGC-1α in the skeletal muscle is associated with increased basal levels of Akt- and p38 MAPK-dependent signalings in mice on HFD. It has previously been shown that expression of PGC-1α is decreased in skeletal muscles in subjects with insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia (29). In contrast, PGC-1α expression is increased in both liver and skeletal muscle when insulin secretion is deleted by streptozotocin (24). We have shown recently that the basal level of Akt phosphorylation is increased in both liver and skeletal muscle in mice with HFD-induced insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia (20). Furthermore, the basal p38 MAPK activity may be also increased in skeletal muscles in subjects with insulin resistance/hyperinsulinemia (16). To further investigate the mechanism of the decreased PGC-1α expression in subjects with insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia, C57BL/6 (B6) mice were fed either ND or HFD for 4 wk, followed by evaluations of PGC-1α level and basal levels of p38 MAPK and Akt phosphorylation. Food consumption and body weight were increased by HFD feeding for 4 wk (Fig. 1, A and B). Fasting plasma insulin level was significantly increased by HFD, whereas fasting blood glucose level was not yet altered (Fig. 1, C and D). As a result, insulin sensitivity evaluated by HOMA was significantly decreased by HFD (Fig. 1E). As shown in Fig. 1, F and G, levels of both mRNA and protein of the PGC-1α gene in gastrocnemius were reduced by the 4-wk HFD. Basal levels of both Akt and p38 MAPK phosphorylations were also increased in gastrocnemius by HFD (Fig. 1, H and I). Together, these results imply that PGC-1α expression may be balanced by the p38 MAPK- and Akt-dependent intracellular signaling pathways.

Fig. 1.

Decreased peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1α (PGC-1α) expression is associated with increased basal levels of both Akt- and p38 MAPK-dependent signaling pathways in skeletal muscle of mice under high-fat diet (HFD). C57BL/6 (B6) mice were fed either the normal chow diet (ND; n = 8) or HFD (n = 7) for 4 wk. After an overnight fast, the following measurements were performed. A: food consumption. B: body weight. C: blood glucose. D: plasma insulin. E: evaluation of insulin sensitivity by HOMA. F: PGC-1α mRNAs in gastrocnemius were quantified by real-time PCR and normalized to 36B4. G: PGC-1α proteins in gastrocnemius were quantified by immunoblotting and normalized to β-actin. H: levels of phosphorylated and total Akt in gastrocnemius were determined by immunoblotting. I: levels of phosphorylated and total p38 MAPK (p38) in gastrocnemius were measured by immunoblotting.

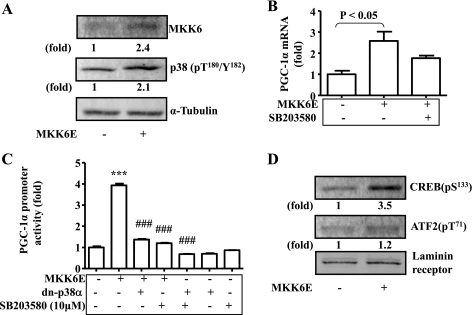

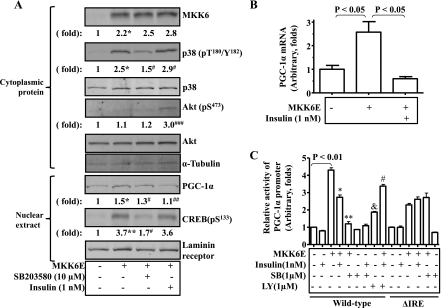

Optimal transcription of the PGC-1α gene requires both p38 MAPK signaling and FoxO transcription factor(s). To further define the mechanism by which p38 MAPK regulates transcription of the PGC-1α gene, p38 MAPK was activated by the constitutively active MKK6 (MKK6E) encoded by recombinant adenoviruses in C2C12 myotubes for 24 h, followed by evaluation of PGC-1α mRNA. Introduction of MKK6E increased the level of MKK6 proteins more than twofold (Fig. 2A). Overexpression of MKK6E activated p38 MAPK as predicted (Fig. 2A). The level of PGC-1α transcripts was increased by the overexpression of MKK6E, and the increase was largely prevented by the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB-203580 (Fig. 2B). To examine the effect of p38 activation on the PGC-1α promoter, p38 MAPK was activated by MKK6E or blocked in C2C12 myotube cells by dominant negative p38 MAPKα (dn-p38α) encoded by recombinant adenoviruses or SB-203580. Overexpression of MKK6E stimulated the PGC-1α promoter, and the stimulation was blocked by either dn-p38α or SB-203580 (Fig. 2C). To examine activation of the CRE-binding transcription factors activated by p38 MAPK, phosphorylations of CREB and activating transcription factor-2 (ATF-2) were measured by immunoblotting. Overexpression of MKK6E stimulated CREB phosphorylation very obviously with a very mild effect on ATF-2 phosphorylation. These results imply that p38 MAPK stimulation of PGC-1α transcription in C2C12 myotube cells may be mediated by CREB under this condition.

Fig. 2.

p38 MAPK-stimulated transcription of the PGC-1α gene is associated with activated cAMP response element (CRE)-binding proteins (CREB). A: levels of MKK6 protein, phosphorylated p38, and α-tubulin in cytoplasm of cells described above were detected by immunoblotting. B: constitutively active MKK6 (MKK6E) was introduced into C2C12 myotube cells via recombinant adenoviral vectors for 24 h, followed by measurements of PGC-1α transcripts with real-time RT-PCR, and normalized to β-actin. Some cells were treated with SB-203680 (10 μM) simultaneously. C: PGC-1α promoter constructs were introduced into C2C12 cells via transient transfection for 24 h together with constitutively active MKK6E encoded by recombinant adenoviruses, followed by measurements of promoter activity with luciferase assays and normalization to β-galactosidase. Some cells were treated with either overexpression of the dominant negative p38 MAPKα (dn-p38α) encoded by recombinant adenoviruses or SB-203580 (1 μM). D: levels of PGC-1α protein, phosphorylated CREB, phosphorylated activating transcription factor-2 (ATF-2), and laminin receptor in the nuclear lysates were determined by immunoblotting with specific antibodies. ***P < 0.001 compared with control (1st bar in C); ###P < 0.001 compared with MKK6E-treated (2nd bar in C). Results represent means ± SD of 3 independent experiments.

To determine the potential role of CREB in PGC-1α gene transcription in C2C12 myotube cells, interactions between transcription factors CREB and myocyte enhancer factor 2C (MEF2C) and PGC-1α prompter elements were examined by ChIP assays with specific antibodies against either CREB or MEF2C, which is known to regulate the PGC-1α promoter (3). As shown in Fig. 3, CREB bound the CRE and the PGC-1α promoter upon p38 MAPK activation. The interaction between MEF2C and MEF2RE was slightly influenced by p38 MAPK activation. These results further show that p38 MAPK promotes PGC-1α gene transcription primarily through CREB instead of MEF2C.

Fig. 3.

CREB binds to the CRE region of the PGC-1α promoter upon p38 MAPK activation. The p38 MAPK in C2C12 myotube cells was activated for 24 h by overexpression of MKK6E encoded by recombinant adenoviruses. The dn-p38α encoded by recombinant adenoviruses was introduced into some cells as indicated via transient cotransfection. Some cells were treated with SB-203580 (10 μM) simultaneously, as indicated. Cells were then fixed by formaldehyde to cross-link proteins to DNA. Sheared chromatin fragments were immunoprecipitated by antisera against either CREB or myocyte enhancer factor 2C (MEF2C). Finally, the DNA fragments bound to either CREB or MEF2C were amplified by PCR and visualized in argarose gels. Results represent 3 independent experiments.

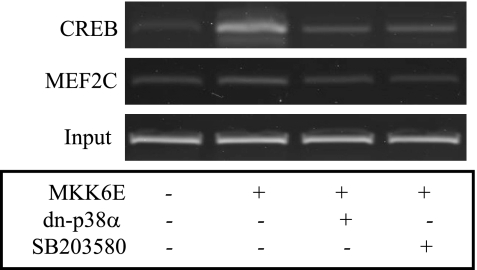

To further investigate the mechanism of p38 MAPK stimulation of the PGC-1α gene transcription, CRE, MEF2RE, and three putative IREs (IRE1: −204tattttt−198; IRE2: −366tgttttg−360; IRE3: −1869atgtttg−1863; see Supplemental Table S1 for details) were mutated one by one, followed by evaluation of p38 MAPK activation of the PGC-1α promoter. As shown in Fig. 4A, mutation of either the CRE or IREs decreased the promoter activity significantly, whereas mutation of MEF2RE reduced the promoter activity less dramatically. Next, the combined effects of p38 MAPK and IRE-binding transcription factors (FoxO) were examined. As shown in Fig. 4B, overexpression of either MKK6E or Ad-FoxO1 stimulated the PGC-1α promoter activity moderately. However, coexpression of MKK6E and Ad-FoxO1 activated PGC-1α promoter dramatically. Together, these results indicate that full activation of the PGC-1α gene transcription requires both the p38 MAPK-mediated activation of transcription factors like CREB and the presence of FoxO transcription factor(s).

Fig. 4.

Full activation of the PGC-1α promoter by p38 MAPK requires both CRE and insulin response elements (IREs). A: the wild-type or mutant PGC-1α promoter with deletion of the CRE, MEF2RE, or IRE was introduced into C2C12 myotube cells via transient transfection. MKK6E encoded by recombinant adenoviruses was introduced into the cells for 48 h, as indicated. Promoter activities were measured by luciferase assays and normalized to β-galactosidase activity. **P < 0.01 vs. 2nd bar; ***P < 0.001 vs. 2nd bar. B: the PGC-1α promoter was introduced into C2C12 myocytes via transient transfection together with either MKK6E or constitutively active FoxO1 (Ad-FoxO1) encoded by recombinant adenoviruses for 24 h. Promoter activity was measured by luciferase assays and normalized to β-galactosidase. Results represent means ± SD of 3 independent experiments. ##P < 0.01 vs. control (1st bar); **P < 0.01.

Insulin blunts the p38 MAPK-mediated expression of the PGC-1α gene. As described above, PGC-1α expression was decreased in the skeletal muscle when the basal phosphorylation levels of both Akt and p38 MAPK were increased (Fig. 1). Since Akt phosphorylation is a key step of insulin signaling and the mice under HFD always have hyperinsulinemia, we examined the role of insulin in the decreased PGC-1α expression. As shown in Fig. 5A, overexpression of MKK6E stimulated phosphorylation of both p38 MAPK and CREB while elevating PGC-1α protein level. The elevated PGC-1α protein level was reduced by the treatment with insulin, which stimulated Akt phosphorylation. Similarly, overexpression of MKK6E enhanced PGC-1α mRNA level, but the enhancement was blocked by insulin (Fig. 5B). To determine the mechanism of insulin suppression of PGC-1α expression, all three putative IREs of the PGC-1α promoter were mutated, followed by evaluations of the wild-type and mutant PGC-1α promoters. As shown in Fig. 5C, both insulin and the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB-203580 blunted the p38 MAPK-mediated activation of the PGC-1α promoter, and insulin suppression was largely prevented by LY-294002. SB-203580 did not affect the basal level of the promoter activity, whereas LY-294002 increased it. When the IREs were mutated, the overall activity of the PGC-1α promoter was decreased, and insulin failed to further decrease the activity of the PGC-1α promoter. Together, these results demonstrate that p38 MAPK-mediated activation of PGC-1α gene transcription is suppressed by insulin signaling.

Fig. 5.

Insulin blunts p38 MAPK-mediated expression of the PGC-1α gene. A: p38 was activated by MKK6E encoded by recombinant adenoviruses in C2C12 myotube cells for 24 h. Some cells were treated with either SB-203580 or insulin simultaneously. Protein levels of phosphorylated and total p38, phosphorylated and total Akt, and tubulin in cytoplasm were measured by immunoblotting. PGC-1α, phospho-CREB, and laminin receptor in the nuclear lysates were determined by immunoblotting. Results represent means ± SD of 2 independent experiments. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 vs. vehicle (−); #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, and ###P < 0.001 vs. MKK6E alone. B: p38 was activated by overexpression of MKK6E encoded by recombinant adenoviruses in C2C12 myotube cells for 24 h. Some cells were treated with either SB-203580 or insulin simultaneously, followed by measurements of PGC-1α mRNA with real-time RT-PCR. C: the PGC-1α promoter was introduced into C2C12 myotube cells via transient transfection together with MKK6E encoded by recombinant adenoviruses as indicated for 24 h. Some cells were treated with insulin (1 nM) or SB-203580 (SB; 1 μM) simultaneously. The promoter activity was then evaluated by luciferase assays and normalized to β-galactosidase activity. Results represent means ± SD of 3 independent experiments. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 vs. MKK6E alone; #P < 0.05 vs. MKK6E + insulin (4th bar); &P < 0.05 vs. negative control (1st bar).

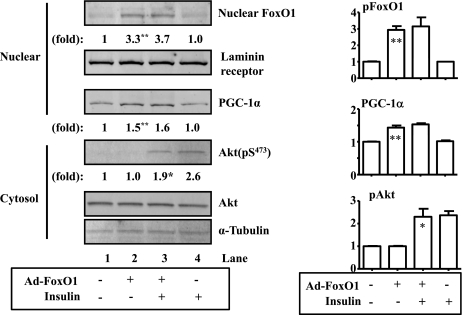

Insulin suppression of the PGC-1α gene transcription is FoxO dependent. Insulin usually inhibits transcription of target genes by phosphorylating and excluding FoxO transcription factors from the nucleus (30). To determine the role of FoxO transcription factors in insulin suppression of the PGC-1α gene, the constitutive nuclear form of FoxO1 encoded by adenoviruses was introduced into C2C12 myotube cells. Ad-FoxO adenovirus infected C2C12 cells effectively (Fig. 6, top). Some cells were treated with insulin as noted. As shown in Fig. 6, insulin did not alter basal levels of PGC-1α and nuclear FoxO1 (compare lanes 1 and 4). Overexpression of Ad-FoxO1 increased levels of both nuclear FoxO1 and PGC-1α proteins. Importantly, insulin failed to suppress the expression of PGC-1α driven by the constitutive nuclear form of FoxO1. These results suggest that insulin suppresses PGC-1α gene expression by excluding FoxO transcription factors from the nucleus.

Fig. 6.

Insulin suppresses expression of the PGC-1α gene through FoxO1. Ad-FoxO1 was introduced into C2C12 myotube cells. Some cells were treated with insulin (1 nM) for 24 h. Protein levels of phospho-FoxO1, PGC-1α, and phospho-Akt were measured by immunoblotting, quantified, and normalized to laminin receptor, α-tubulin, or total Akt, respectively, in the nuclear or cytoplasm lysates. Results represent 3 independent experiments. *P < 0.05 vs. lane 1; **P < 0.01 vs. lane 1.

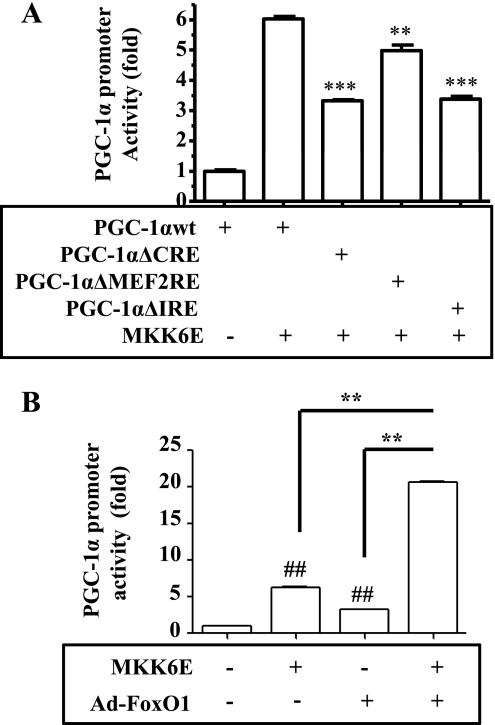

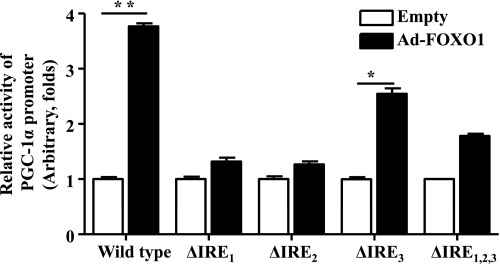

Insulin suppression of PGC-1α gene transcription is mediated mainly by IRE1 and IRE2. To determine the promoter elements that are involved in insulin inhibition of the PGC-1α gene, three putative insulin response elements (IRE1, -2, and -3) were mutated one at a time or all together. Activities of these mutant promoters were then examined in C2C12 myotube cells. As shown in Fig. 7, mutation of either IRE1 or IRE2 abolished the promoter activity completely, whereas mutation of IRE3 reduced the promoter activity less dramatically. Mutations of all three IREs together reduced the promoter activity significantly, but apparently less dramatically than mutations of either IRE1 or IRE2 alone. These results suggest that IRE1 and IRE2 are necessary for PGC-1α promoter activation, and IRE3 may be required for the optimal activation of PGC-1α gene transcription.

Fig. 7.

FoxO1-promoted transcription of the PGC-1α promoter is mediated primarily by IRE1 and -2. The wild-type or mutant PGC-1α promoter was introduced into C2C12 myotube cells via transient transfection. Ad-FoxO1 was introduced into C2C12 myotube cells as noted for 24 h. The promoter activity was then measured by luciferase assays and normalized to β-galactosidase activity. Results represent 3 independent experiments. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

Since its discovery by Puigserver et al. (35), PGC-1α has been shown to be involved in many different fundamental processes, such as thermogenesis, gluconeogenesis, maintaining the architecture and functions of skeletal muscles, central control of metabolism, antioxidation, cholesterol metabolism, and aging (14, 18, 19, 28, 32, 35–37, 39, 42). Overall, PGC-1α appears to be a master transcriptional coactivator that promotes the combustion of stored energy primarily by enhancing mitochondrial production and consequently influences other fundamental processes such as oxidative stress and aging. In this study, we have found that PGC-1α gene transcription is balanced by different intracellular signaling pathways.

Expression of PGC-1α is increased under different situations. First, PGC-1α expression is increased in the brown adipose tissue after cold exposure, during which insulin signaling is reduced (27). Second, PGC-1α expression is increased in the liver when plasma insulin level is low during fasting and when insulin secretion is deficient in diabetes (7, 24). Third, PGC-1α expression is increased in skeletal muscles after physical exercise (2, 41). In all of these situations, the increased PGC-1α expression is accompanied by the elevated activity of p38 MAPK. In some cases, it has been shown that blockade of p38 MAPK can prevent the increased expression of PGC-1α. Results from this study also show that p38 MAPK plays a stimulatory role in PGC-1α in myotubes. The stimulatory effect of p38 MAPK has previously been shown to be mediated by ATF-2 (2). Our results in this study show that CREB plays a primary role of p38 activation of PGC-1α promoter. The reason for the difference is currently unknown.

Expression of PGC-1α is at a low level during the fed and unprovoked state (7, 35). A lot of attention has been paid to why PGC-1α expression is increased under various conditions whereas little attention has been paid to the question of why PGC-1α expression is low under the fed and unprovoked states. It can be due to lack of stimulators such as adrenelines, glucagon, p38 MAPK, or others. But it can certainly be due to the presence of an inhibitor(s). One such likely candidate is insulin. Insulin is increased in the blood during the fed state and is the single most dominant inhibitor of energy spending, which is contrary to the master effect of PGC-1α in promoting fuel combustion. Decreased insulin signaling is accompanied by cold-induced increase of PGC-1α expression (27). Deletion of insulin secretion leads to increased PGC-1α expression (24). Here we have found that addition of insulin can prevent p38 MAPK-mediated expression of PGC-1α. Insulin suppression of PGC-1α expression is neutralized by the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitor LY-294002 or overexpression of the constitutively nuclear form of FoxO1. Furthermore, our results demonstrate that the optimal activation of the PGC-1α promoter requires both p38 MAPK- and FoxO-mediated activities. Thus, the low FoxO activity in the presence of insulin signaling may contribute to the low level of PGC-1α expression during the fed and unprovoked states. This may help explain why PGC-1α expression in skeletal muscles is decreased in subjects with insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia (11, 29). Since both PGC-1α and FoxO transcription factors are known to be required for maintaining muscle mass, our results may also help explain why subjects with insulin resistance/hyperinsulinemia generally lose their muscle mass while gaining fat mass.

The functions of FoxO transcription factors are carried out through their interactions with various IREs. Previous studies identified three IREs in the PGC-1α promoter (12). They are located at −976 to −970, −586 to −580, and −354 to −348 (12). In this study, we also identified three IREs, but they are located at −1,869 to −1,863 (IRE1), −366 to −360 (IRE2), and −204 to −198 (IRE3). Mutations of either IRE1 or IRE2 almost abolished the promoter activity, whereas mutations of IRE3 only slightly diminished the promoter activity. Unexpectedly, mutations of all three IREs appear to have less effect than mutations of either IRE1 or IRE2 alone. The reason is unclear now. It is possible that the three-dimensional structure of the PGC-1α promoter is altered by mutations of all three IREs, and the alteration may increase the access of other transcriptional stimulators such as CREB, leading to more promoter activity.

In summary, results from this study provide new understanding about p38 MAPK-mediated transcription of PGC-1α. More importantly, our results provide explanations about the low expression level of PGC-1α gene under various physiological and pathophysiological situations. Therefore, results from this study may provide new strategies to prevent and reverse many modern health problems associated with the positive energy imbalance caused by overeating and/or lack of physical activity.

GRANTS

This work was supported by the Investigator Development Fund from the Hamner Institutes for Health Sciences (to W. Cao), American Diabetes Association Grant 7-09-BS-27 (to W. Cao), and National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant R01-DK-076039 (to W. Cao).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- 1. Accili D. Lilly lecture 2003: the struggle for mastery in insulin action: from triumvirate to republic. Diabetes 53: 1633–1642, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Akimoto T, Pohnert SC, Li P, Zhang M, Gumbs C, Rosenberg PB, Williams RS, Yan Z. Exercise stimulates Pgc-1alpha transcription in skeletal muscle through activation of the p38 MAPK pathway. J Biol Chem 280: 19587–19593, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Akimoto T, Sorg BS, Yan Z. Real-time imaging of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1α promoter activity in skeletal muscles of living mice. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 287: C790–C796, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Al-Shawwa BA, Al-Huniti NH, DeMattia L, Gershan W. Asthma and insulin resistance in morbidly obese children and adolescents. J Asthma 44: 469–473, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. An J, Muoio DM, Shiota M, Fujimoto Y, Cline GW, Shulman GI, Koves TR, Stevens R, Millington D, Newgard CB. Hepatic expression of malonyl-CoA decarboxylase reverses muscle, liver and whole-animal insulin resistance. Nat Med 10: 268–274, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Burns JM, Donnelly JE, Anderson HS, Mayo MS, Spencer-Gardner L, Thomas G, Cronk BB, Haddad Z, Klima D, Hansen D, Brooks WM. Peripheral insulin and brain structure in early Alzheimer disease. Neurology 69: 1094–1104, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cao W, Collins QF, Becker TC, Robidoux J, Lupo J, Xiong Y, Daniel K, Floering L, Collins S. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase plays a stimulatory role in hepatic gluconeogenesis. J Biol Chem 280: 42731–42737, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cao W, Daniel KW, Robidoux J, Puigserver P, Medvedev AV, Bai X, Floering LM, Spiegelman BM, Collins S. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase is the central regulator of cyclic AMP-dependent transcription of the brown fat uncoupling protein 1 gene. Mol Cell Biol 24: 3057–3067, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cole GM, Frautschy SA. The role of insulin and neurotrophic factor signaling in brain aging and Alzheimer's Disease. Exp Gerontol 42: 10–21, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Crowell JA, Steele VE, Fay JR. Targeting the AKT protein kinase for cancer chemoprevention. Mol Cancer Ther 6: 2139–2148, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Crunkhorn S, Dearie F, Mantzoros C, Gami H, da Silva WS, Espinoza D, Faucette R, Barry K, Bianco AC, Patti ME. Peroxisome proliferator activator receptor gamma coactivator-1 expression is reduced in obesity: potential pathogenic role of saturated fatty acids and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation. J Biol Chem 282: 15439–15450, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Daitoku H, Yamagata K, Matsuzaki H, Hatta M, Fukamizu A. Regulation of PGC-1 promoter activity by protein kinase B and the forkhead transcription factor FKHR. Diabetes 52: 642–649, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Frescas D, Valenti L, Accili D. Nuclear trapping of the forkhead transcription factor FoxO1 via Sirt-dependent deacetylation promotes expression of glucogenetic genes. J Biol Chem 280: 20589–20595, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Handschin C, Chin S, Li P, Liu F, Maratos-Flier E, Lebrasseur NK, Yan Z, Spiegelman BM. Skeletal muscle fiber-type switching, exercise intolerance, and myopathy in PGC-1alpha muscle-specific knock-out animals. J Biol Chem 282: 30014–30021, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Irrcher I, Adhihetty PJ, Sheehan T, Joseph AM, Hood DA. PPARγ coactivator-1α expression during thyroid hormone- and contractile activity-induced mitochondrial adaptations. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 284: C1669–C1677, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Koistinen HA, Chibalin AV, Zierath JR. Aberrant p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase signalling in skeletal muscle from Type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetologia 46: 1324–1328, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Li X, Monks B, Ge Q, Birnbaum MJ. Akt/PKB regulates hepatic metabolism by directly inhibiting PGC-1alpha transcription coactivator. Nature 447: 1012–1016, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lin J, Wu H, Tarr PT, Zhang CY, Wu Z, Boss O, Michael LF, Puigserver P, Isotani E, Olson EN, Lowell BB, Bassel-Duby R, Spiegelman BM. Transcriptional co-activator PGC-1 alpha drives the formation of slow-twitch muscle fibres. Nature 418: 797–801, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Liu C, Li S, Liu T, Borjigin J, Lin JD. Transcriptional coactivator PGC-1alpha integrates the mammalian clock and energy metabolism. Nature 447: 477–481, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liu H, Hong T, Wen GB, Han J, Zhuo D, Liu Z, Cao W. Increased basal level of Akt-dependent insulin signaling may be responsible for the development of insulin resistance. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 297: E898–E906, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liu HY, Cao SY, Han J, Hong T, Zhuo D, Liu Z, Cao W. Insulin is a stronger inducer of insulin resistance than hyperglycemia in mice with Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM). J Biol Chem 284: 27090–27100, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liu HY, Collins QF, Xiong Y, Moukdar F, Lupo J, Liu Z, Cao W. Prolonged treatment of primary hepatocytes with oleate induces insulin resistance through p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem 282: 14205–14212, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Liu HY, Wen GB, Han J, Hong T, Zhuo D, Liu Z, Cao W. Inhibition of hepatic gluconeogenesis in primary hepatocytes by stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1) through a c-Src/Akt-dependent signaling pathway. J Biol Chem 283: 30642–30649, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Liu HY, Yehuda-Shnaidman E, Hong T, Han J, Pi J, Liu Z, Cao W. Prolonged exposure to insulin suppresses mitochondrial production in primary hepatocytes. J Biol Chem 284: 14087–14095, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Moreira PI, Santos MS, Seica R, Oliveira CR. Brain mitochondrial dysfunction as a link between Alzheimer's disease and diabetes. J Neurol Sci 257: 206–214, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Okazaki R. [Links between osteoporosis and atherosclerosis; beyond insulin resistance]. Clin Calcium 18: 638–643, 2008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Oliveira RL, Ueno M, de Souza CT, Pereira-da-Silva M, Gasparetti AL, Bezzera RM, Alberici LC, Vercesi AE, Saad MJ, Velloso LA. Cold-induced PGC-1α expression modulates muscle glucose uptake through an insulin receptor/Akt-independent, AMPK-dependent pathway. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 287: E686–E695, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Olmos Y, Valle I, Borniquel S, Tierrez A, Soria E, Lamas S, Monsalve M. Mutual dependence of Foxo3a and PGC-1alpha in the induction of oxidative stress genes. J Biol Chem 284: 14476–14484, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Patti ME, Butte AJ, Crunkhorn S, Cusi K, Berria R, Kashyap S, Miyazaki Y, Kohane I, Costello M, Saccone R, Landaker EJ, Goldfine AB, Mun E, DeFronzo R, Finlayson J, Kahn CR, Mandarino LJ. Coordinated reduction of genes of oxidative metabolism in humans with insulin resistance and diabetes: Potential role of PGC1 and NRF1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 8466–8471, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pierrou S, Hellqvist M, Samuelsson L, Enerback S, Carlsson P. Cloning and characterization of seven human forkhead proteins: binding site specificity and DNA bending. EMBO J 13: 5002–5012, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Popa C, Netea MG, van Riel PL, van der Meer JW, Stalenhoef AF. The role of TNF-alpha in chronic inflammatory conditions, intermediary metabolism, and cardiovascular risk. J Lipid Res 48: 751–762, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Puigserver P, Rhee J, Donovan J, Walkey CJ, Yoon JC, Oriente F, Kitamura Y, Altomonte J, Dong H, Accili D, Spiegelman BM. Insulin-regulated hepatic gluconeogenesis through FOXO1-PGC-1alpha interaction. Nature 423: 550–555, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Puigserver P, Rhee J, Lin J, Wu Z, Yoon JC, Zhang CY, Krauss S, Mootha VK, Lowell BB, Spiegelman BM. Cytokine stimulation of energy expenditure through p38 MAP kinase activation of PPARgamma coactivator-1. Mol Cell 8: 971, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Puigserver P, Spiegelman BM. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator 1 alpha (PGC-1 alpha): transcriptional coactivator and metabolic regulator. Endocr Rev 24: 78–90, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Puigserver P, Wu Z, Park CW, Graves R, Wright M, Spiegelman BM. A cold-inducible coactivator of nuclear receptors linked to adaptive thermogenesis. Cell 92: 829–839, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shin DJ, Campos JA, Gil G, Osborne TF. PGC-1alpha activates CYP7A1 and bile acid biosynthesis. J Biol Chem 278: 50047–50052, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Song KH, Ellis E, Strom S, Chiang JY. Hepatocyte growth factor signaling pathway inhibits cholesterol 7alpha-hydroxylase and bile acid synthesis in human hepatocytes. Hepatology 46: 1993–2002, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sterry W, Strober BE, Menter A. Obesity in psoriasis: the metabolic, clinical and therapeutic implications. Report of an interdisciplinary conference and review. Br J Dermatol 157: 649–655, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wenz T, Rossi SG, Rotundo RL, Spiegelman BM, Moraes CT. Increased muscle PGC-1alpha expression protects from sarcopenia and metabolic disease during aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 20405–20410, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 40. Wright DC, Geiger PC, Han DH, Jones TE, Holloszy JO. Calcium induces increases in peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1alpha and mitochondrial biogenesis by a pathway leading to p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation. J Biol Chem 282: 18793–18799, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wright DC, Han DH, Garcia-Roves PM, Geiger PC, Jones TE, Holloszy JO. Exercise-induced mitochondrial biogenesis begins before the increase in muscle PGC-1alpha expression. J Biol Chem 282: 194–199, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wu Z, Puigserver P, Andersson U, Zhang C, Adelmant G, Mootha V, Troy A, Cinti S, Lowell B, Scarpulla RC, Spiegelman BM. Mechanisms controlling mitochondrial biogenesis and respiration through the thermogenic coactivator PGC-1. Cell 98: 115–124, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.