Abstract

Lymphoid enhancer-binding factor (Lef) 1 is a high mobility group protein best known as a Wnt-responsive transcription factor that associates with β-catenin. Lef1ΔN is a short isoform of Lef1 that lacks the first 113 amino acids and a well characterized high affinity β-catenin binding domain present in the full-length protein. Both Lef1 isoforms bind DNA and regulate gene expression. We previously reported that Lef1 is expressed in proliferating osteoblasts and blocks osteocalcin expression. In contrast, Lef1ΔN is only detectable in the later stages of osteoblast differentiation and promotes osteogenesis in vitro. Here, we show that Lef1ΔN retains the ability to interact physically and functionally with β-catenin. Unlike what has been reported in T cells and colon cancer cell lines, Lef1ΔN activated gene transcription in the absence of exogenous β-catenin and cooperated with constitutively active β-catenin to stimulate gene transcription in mesenchymal and osteoblastic cells. Residues at the N terminus of Lef1ΔN were required for β-catenin binding and the expression of osteoblast differentiation genes. To determine the role of Lef1ΔN on bone formation in vivo, a Lef1ΔN transgene was expressed in committed osteoblasts using the 2.3-kb fragment of the type 1 collagen promoter. The Lef1ΔN transgenic mice had higher trabecular bone volume in the proximal tibias and L5 vertebrae. Histological analyses of tibial sections revealed no differences in osteoblast, osteoid, or osteoclast surface areas. However, bone formation and mineral apposition rates as well as osteocalcin levels were increased in Lef1ΔN transgenic mice. Together, our data indicate that Lef1ΔN binds β-catenin, stimulates Lef/Tcf reporter activity, and promotes terminal osteoblast differentiation.

Keywords: β-Catenin, Gene Transcription, Transcription Factors, Transcription Regulation, Wnt Pathway, Bone Formation, Osteoblast, Osteocalcin, Runx2

Introduction

Canonical Wnt signaling has emerged as a crucial pathway regulating skeletal development, bone mass maintenance, and bone repair (1–3). Several new anabolic therapies for bone diseases are being explored because they enhance canonical Wnt signaling in osteoblasts (4). Wnts stimulate a variety of responses in osteoblast lineage cells, including progenitor cell proliferation and commitment to the osteoblast lineage and survival of mature osteoblasts, but they also inhibit terminal differentiation (5–8). It is still unclear how these distinct responses to Wnts are induced at different times during osteoblast maturation, but evidence suggests that receptor profiles (9) as well as both direct stimulation and exposure to secondary endocrine factors contribute to optimal matrix production (10). Further complicating the picture is that the major intracellular amplifier of canonical Wnt signaling, β-catenin, is responsive to other stimuli and induces responses unique from those of Lrp5 (a Wnt co-receptor) in osteoblast lineage cells (5, 11–15). Many of the direct effects of canonical Wnt signaling and β-catenin activation are mediated by four transcription factors: lymphoid enhancer-binding factor 1 (Lef1),3 T cell factor 7 (Tcf7, previously called Tcf1), Tcf7-like1 (Tcf7L1, Tcf3) and Tcf7L2 (Tcf4). In this report, the role of a short Lef1 isoform, Lef1ΔN, in osteoblast maturation and bone formation is described.

Lef1 binds DNA sequences to either activate or repress gene transcription. In the absence of canonical Wnt signaling, Lef1 associates with transcriptional co-repressors (e.g. TLE and histone deacetylases) to suppress gene expression (for review, see Refs. 16, 17). When β-catenin is stabilized by canonical Wnts, it translocates to the nucleus where it replaces these co-repressors with co-activators (e.g. p300) to augment chromatin binding and induce gene transcription (for review, see 16, 17). Interestingly, Lef1 mRNA is induced by canonical Wnt signaling (18–20) and is often considered to be an indicator of Wnt activity. Lef1 activity is increased in bone at remodeling and regeneration sites and in proliferating preosteoblasts (3, 21–27). Lef1 protein levels subsequently decline during the course of osteoblast differentiation as proliferation ceases (28).

Like most genes in higher organisms, Lef1 and Tcf7 encode several transcripts and isoforms by utilizing multiple promoters and through alternative splicing (18, 20, 29, 30). Some Lef1/Tcf7 isoforms lack the N-terminal high affinity β-catenin binding domain but retain the DNA binding domain and act as competitive inhibitors of full-length Lef1/Tcf7 proteins (17, 31). Lef1ΔN is a 38-kDa protein that lacks the first 113 amino acids found in Lef1 (18, 32). It is transcribed from a second promoter located within intron 2 of Lef1 and is subject to transcriptional repression by YY1 (18, 33). Lef1 and Lef1ΔN are expressed in normal cells within hematopoietic tissues, skin, and gut; however, such expression is limited to discrete stages of maturation. This delicate balance of Lef1 to Lef1ΔN levels is disturbed in some tumors (34–38). We recently reported that bone morphogenic protein (Bmp) 2 induces Lef1ΔN expression in osteoblasts, and that Runx2 binds directly to and positively regulates the alternative promoter driving Lef1ΔN expression (39). Lef1ΔN was only detected in later stages of osteoblast differentiation. Stable expression of Lef1ΔN in multipotent mesenchymal cells increased production of osteocalcin transcripts (39). This is in contrast to full-length Lef1, which was nearly undetectable in differentiated osteoblasts and inhibited osteoblast maturation when expressed in preosteoblasts (28).

In this study, the role of Lef1ΔN during skeletal development was examined. Lef1-deficient mice do not express either Lef1 or Lef1ΔN because a 3′ exon encoding the DNA binding domain was inactivated by homologous recombination (40). These Lef1 knock-out mice are smaller than normal littermates, lack tissues formed by epithelial and mesenchymal interactions, and die shortly after birth. Because of this short lifespan, the effects of Lef1 deficiency on skeletal maturation could not be determined; however, female Lef1-haploinsufficient mice are osteopenic due to decreased bone formation rates (41). The contributions of Lef1 isoforms to these phenotypes have not been distinguished because Lef1ΔN does not contain any unique coding sequences that distinguish it from Lef1, which has made specific deletion challenging. Given the temporal and inducible expression pattern of Lef1ΔN and its ability to induce certain key markers of osteoblast differentiation in vitro (39), we were interested in the role this isoform may play in the skeleton in vivo. We created transgenic mice in which Lef1ΔN is expressed in mature osteoblasts under the control of the (2.3)Col1a1 promoter. Consistent with our in vitro findings (39), these Lef1ΔN transgenic mice exhibited increased trabecular bone volume compared with their wild-type littermates. Interestingly, Lef1ΔN did not act as a competitive inhibitor of β-catenin-mediated activation of a Lef1-responsive promoter, but rather enhanced activation in osteogenic cells. Our results suggest that Lef1ΔN interacts with β-catenin through a second β-catenin binding domain to promote bone formation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture

C2C12 and COS-7 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; 5 mm glucose) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Invitrogen), 200 mm l-glutamine, 50 units/ml penicillin, and 50 mg/ml streptomycin. C3H10T1/2 and MC3T3-E1 cells were expanded in minimal essential medium (MEM; 5 mm glucose) containing 10% FBS, 1× nonessential amino acids, 200 mm l-glutamine, 50 units/ml penicillin, and 50 mg/ml streptomycin. U2OS osteosarcoma cells were maintained in DMEM/Ham's F12 medium (5 mm glucose) supplemented with 10% FBS, 50 units/ml penicillin, and 50 mg/ml streptomycin. Jurkat cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (12.5 mm glucose) containing 10% FBS, 50 units/ml penicillin, and 50 mg/ml streptomycin. To induce osteogenic differentiation, confluent C2C12 cell cultures were incubated in DMEM with 10% FBS, 50 μg/ml ascorbic acid, 10 mm β-glycerolphosphate, and 300 ng/ml Bmp2 for the indicated number of days.

Construction of Lef1ΔN Deletion Plasmids

Expression plasmids producing truncated Lef1 proteins (Lef1 (128–397), (150–397), (175–397), (252–397), and (282–397)) were generated by PCR from pCMV-Lef1ΔN. Restriction sites and an ATG start codon were introduced using PCR. The resulting products were digested with KpnI and EcoRI and ligated into a pCMV-FLAG plasmid. Note that the residue numbers coincide with amino acids within Lef1. Within this numbering scheme, Lef1ΔN is Lef1 (114–397).

Transcription Assays

C2C12 cells were transfected with Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) in 12-well plates with the Top-Flash luciferase reporter plasmid (200 ng) and pRL-null (10 ng). Lef1ΔN and constitutively active β-catenin expression plasmids (300 ng unless specified otherwise) were added as indicated. U2OS osteosarcoma cells were plated at a density of 6.5 × 104 cells/well in 12-well plates, incubated overnight in growth medium, and then transfected using a 3:1 ratio (μl:μg) of FuGENE 6 (Roche Applied Science) to DNA. Each well received Top-Flash (200 ng) and pRL-null (5 ng) in the presence or absence of pCMV-Lef1ΔN (300 ng). pcDNA3.1 was added to all transfections to normalize DNA concentrations. Following a 24–48-h incubation at 37 °C, luciferase activity in 20 μl of cell lysate was measured using the dual luciferase assay system (Promega) and a Glomax 96 microplate luminometer. All transfections were performed in triplicate, and data were normalized to the activity of Renilla luciferase.

Retroviral Subcloning and Transduction

To produce retroviruses, HEK 293T cells were co-transfected with 5 μg of pCL2 and 5 μg of pMSCV-puro-Lef1ΔN, pMSCV-puro-Lef1 (175–397), pMSCV-puro-Lef1 (252–397), or empty pMSCV-puro vector using calcium phosphate precipitation. Transduction and stable selection of puromycin-resistant C2C12 cells were performed as reported previously (39).

Immunoblotting and Immunoprecipitation

Immunoblotting was performed with Lef1 (catalog no. C18A7, 1:1,000 dilution; Cell Signaling Technology), FLAG (catalog no. F3165, 1:10,000; Sigma-Aldrich), or lamin B (catalog no. sc-6216, 1:2,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) antibodies. For immunoprecipitations, transfected COS-7 cells were lysed in extraction buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, 75 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 0.25% Triton X-100, 1 mm DTT, and 10% glycerol) containing protease inhibitors (Roche Applied Science). Equal fractions of the lysates were incubated with Lef1 antibody (1 μg) overnight at 4 °C. The immune complexes were collected with protein G Dynabeads (Invitrogen). Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membrane (Immobilon-P, Millipore), and immunoblotted with Myc tag antibody (clone 9B11; Cell Signaling Technology) to detect constitutively active β-catenin. Fractions of whole cell lysates were also immunoblotted with anti-Myc and anti-Lef1 to detect overall expression levels of constitutively active β-catenin and Lef1 proteins.

RNA Isolation and Reverse Transcription (RT)-Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

Total RNA was harvested from cell lines using TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen). To isolate RNA from mouse long bones, bone marrow was first removed by aspiration using a 27-gauge syringe. Following three washes with serum-free α-MEM, bones were placed directly in TRIzol for 45 min at 4 °C and then for 15 min at room temperature without pulverization. Total RNA was isolated from other mouse organs after pulverizing the frozen samples with a mortar and pestle and lysing cells with TRIzol. Extracted RNA was treated with RNase-free DNase (Qiagen) and purified with RNeasy/QIAamp columns (Qiagen). qPCR was performed using the QuantiTech SYBR Green RT-PCR kit (Qiagen) per the manufacturer's instructions. Thus, RNA (10–25 ng) was added to 20-μl reactions with QuantiTech SYBR Green RT master mix, QuantiTech RT mix, and 0.5 pmol/μl of each of the oligonucleotide primers. To detect specifically Lef1ΔN-FLAG transgene expression in tissues, primers corresponding to exon 10 of Lef1 (5′-AGC ACG GAA AGA GAG ACA GC and FLAG (5′-GCC CTT GTC ATC ATC GTC CTT GTA G) were used. Total Lef1ΔN levels were measured as described previously (39). The primer pairs used were Lef1 (forward, 5′-GAT CCC CTT CAA GGA CGA AG; reverse, 5′-GGC TTG TCT GAC CAC CTC AT) and Lef1 FL/ΔN (forward, 5′-TCA CTG TCA GGC GAC ACT TC; reverse, 5′-TGA GGC TTC ACG TGC ATT AG). Other primer pairs detected type I collagen (forward, 5′-GAA ACC CGA GGT ATG CTT GA; reverse, 5′-GGG TCC CTC GAC TCC TAC AT) or actin (forward, 5′-AAG GAA GGC TGG AAA AGA GC; reverse, 5′-GCT ACA GCT TCA CCA CCA CA) in primary osteoblasts and C2C12 cells. Osteocalcin was detected in C2C12 cells with the following primers: forward, AAG CAG GAG GGC AAT AAG GT; reverse, TTT GTA GGC GGT CTT CAA GC. In primary osteoblasts, osteocalcin was amplified with these primers: forward, 5′-CCT GAG TCT GAC AAA GCC TTC A; reverse, 5′-GCC GGA GTC TGT TCA CTA CCT T. In the reactions, reverse transcription was performed at 50 °C for 30 min. An initial denaturation step was performed at 95 °C for 15 min followed by 40 cycles of three-step PCR: 95 °C denaturation for 30 s, 57 °C annealing for 30 s, and 72 °C elongation for 30 s. All reactions were run on an iCycler (Bio-Rad). Data were normalized to mouse actin levels as described previously (39).

Development of Lef1ΔN Transgenic Mouse

A Lef1ΔN cDNA construct beginning with the translation-initiating methionine in exon 3 and extending through the end of the murine Lef1 coding region was fused to a C-terminal FLAG epitope tag and inserted into a pGL3-(2.3)Col1a1 expression vector. The resulting (2.3)Col1a1-Lef1ΔN construct was subcloned into a pTYR-3′IN2b expression vector (kindly provided by Dr. Brendan Lee (42)), which encodes the coat-color gene tyrosinase, along with a 3′ WPRE that facilitates mRNA transport from the nucleus to the cytoplasm. The pTYR-(2.3)Col1a1-Lef1ΔN expression vector was injected into FVB embryos in the Mayo Clinic Transgenic and Gene Knock-out Core Facility. Mice used in this study (heretofore called Lef1ΔN transgenic mice) were derived from a founder containing a single copy of the transgene (data not shown). All data in this report were obtained from first generation mice on a mixed FVB/C57BL/6 background. Mice were housed in a temperature- and humidity-controlled barrier room with a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle, had free access to water, and were fed a controlled diet (AIM 93M Diets, Bethlehem, PA). The Mayo Clinic Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved the experimental protocol.

Microcomputed Tomography Analyses

Trabecular bone architecture and mineralization were analyzed by microcomputed tomography (μCT) using a SCANCO Medical μCT 35 (Scanco USA, Wayne, PA). Scans were performed at 7-μm resolution on both tibias and L5 vertebrae. Data regarding the proximal tibias were collected from a 0.7-mm-deep region of the secondary spongiosa, beginning 0.9 mm distal to the growth plate. Data collected from the L5 vertebrae corresponded to a 0.7-mm-deep region in the longitudinal center of each vertebra.

Static and Dynamic Histology

Following μCT analyses, the proximal tibias were embedded in glycolmethacrylate, sectioned into 5-μm slices, and stained with McNeal's/von Kossa or tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP). Sections were analyzed with OsteoMeasure 2.1.01 software (OsteoMetrics, Decatur, GA) for quantification of osteoblast and osteoclast surface areas, respectively. Osteoblasts were identified as cuboidal-shaped cells lining a trabecular bone surface on McNeal's/von Kossa-stained sections. Osteoclasts were defined as TRAP-positive multinuclear cells lining a trabecular surface. Eroded surface was quantified as TRAP-positive bone surface with scalloped edges indicative of resorptive activity. Osteoid surface and thickness were measured from McNeal's/von Kossa-stained sections. All static measurements were taken at 400×.

For dynamic measures, mice were double-labeled by two subcutaneous calcein injections (10 mg/kg in 1× PBS, 2% NaHCO3). The time between calcein injections in 4-week-old mice was 48 h with the last injection administered 24 h prior to euthanasia. Mineral apposition and bone formation rates as well as double- and single-labeled trabecular bone surface areas were measured on unstained sections using OsteoMeasure 2.1.01 software. All dynamic measurements were taken at 400×.

Quantification of Serum Osteocalcin Levels

Whole blood was collected from 8-week-old male mice at the time of sacrifice, placed into serum separator tubes (B&D, Franklin Lakes, NJ), and incubated at room temperature for 1 h. Coagulated blood was centrifuged for 15 min at 4 °C at 2,000 × g. Serum was transferred to new tubes and stored at −80 °C. The collected serum was analyzed with a Milliplex Mouse Osteocalcin Single Plex kit (Millipore) and a Bio Plex 200 system (Bio-Rad).

Statistical Analyses

Significance between means was determined by Student's t tests.

RESULTS

Lef1ΔN Binds and Cooperates with β-Catenin in Mesenchymal Cells

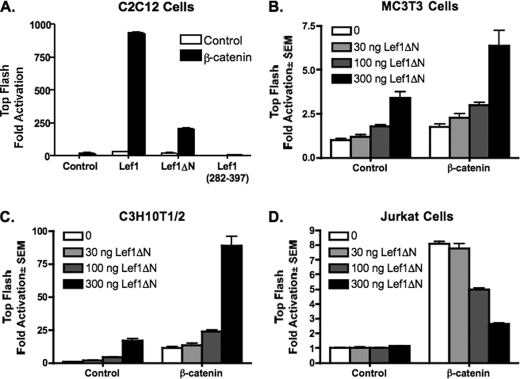

We recently reported that Lef1ΔN expression is induced during late stages of osteoblast differentiation and that stable expression of Lef1ΔN in C2C12 myo-osteoblast progenitor cells correlates with increased osteocalcin production (39). Lef1ΔN lacks the well characterized β-catenin domain present in the full-length isoform of Lef1 but retains the DNA binding domain; therefore, it may mechanistically induce terminal differentiation by competitively inhibiting β-catenin and Lef1/Tcf7-mediated expression of genes involved in osteoblast proliferation. To test Lef1ΔN transcriptional activity in mesenchymal cells, C2C12 cells were transfected with the Lef1-responsive reporter, Top-Flash, in the presence or absence of constitutively active β-catenin and Lef1, Lef1ΔN, or Lef1 (282–397), which retains the DNA binding domain and nuclear localization signal. As expected, Lef1 and β-catenin were potent co-stimulators of transcription (Fig. 1A). Lef1ΔN also cooperated with β-catenin synergistically to activate the Top-Flash reporter. Although Lef1ΔN was not as effective as Lef1, it still augmented transcription in the presence of constitutively active β-catenin. However, Lef1 (282–397) did not activate the Lef1-responsive promoter and modestly repressed basal activity in the presence of β-catenin (Fig. 1A). Lef1ΔN similarly activated this reporter in two other mesenchymal cell lines (MC3T3 and C3H10T1/2) in a concentration-dependent manner both in the absence or presence of constitutively active β-catenin (Fig. 1, B and C). In contrast, Lef1ΔN repressed constitutively active β-catenin-induced activation in the Jurkat human T cell lymphoma cell line (Fig. 1D) and in murine EL4 lymphoma cells (data not shown). These results are consistent with previously reported data and conclusions that Lef1ΔN is a competitive inhibitor of Lef1 in T lymphocytes (18). Thus, the ability of Lef1ΔN to activate gene transcription is tissue-dependent.

FIGURE 1.

Lef1ΔN enhances β-catenin-mediated activation in osteogenic cells but represses activation in T lymphocytes. C2C12 (A), MC3T3 (B), CH310T1/2 (C), and Jurkat (D) cells were transfected with the Lef1/Tcf7-luciferase reporter plasmid Top-Flash, Lef1ΔN constructs, and constitutively active β-catenin as indicated. Luciferase activity was measured 24 h after transfection. Firefly luciferase values were normalized to Renilla controls. Reactions were performed in triplicate, and data are representative of at least three experiments.

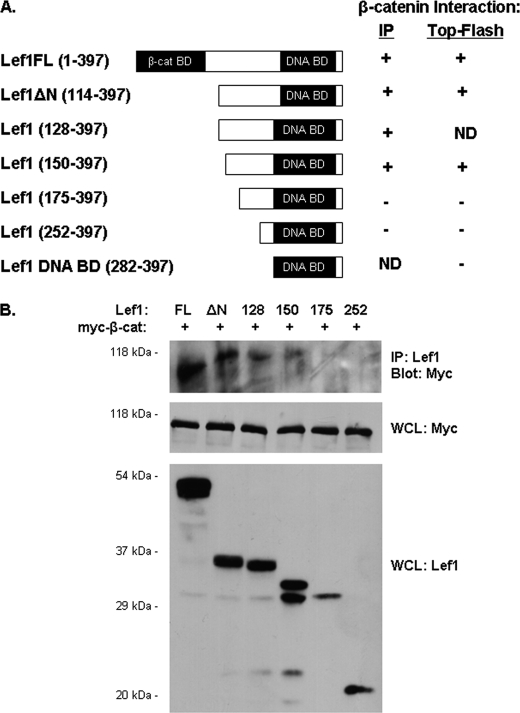

To determine whether Lef1ΔN binds β-catenin directly, we created a series of Lef1ΔN deletion constructs by progressively truncating Lef1ΔN from the N terminus (Fig. 2A). In immunoprecipitation assays, both Lef1 and Lef1ΔN interacted with constitutively active, Myc-tagged β-catenin (Fig. 2B). Lef1 (128–397) and (150–397) also associated with β-catenin, whereas Lef1 (175–397) and (252–397) did not. These results suggest that Lef1 residues 150–175 are necessary for Lef1ΔN to interact with β-catenin.

FIGURE 2.

Lef1ΔN contains a β-catenin binding domain. A, schematic illustrates the Lef1 constructs used in this study. On the right is a summary of how each Lef1 construct enhanced β-catenin-mediated activation of Top-Flash and interacted with β-catenin in immunoprecipitation assays. Note that the numbers in parentheses coincide with amino acids within Lef1. Within this numbering scheme, Lef1ΔN is Lef1 (114–397). ND (not determined) indicates that a particular construct was not tested in the indicated assay. B, β-catenin immunoprecipitates with full-length Lef1 (positive control), Lef1ΔN (114–397), Lef1 (128–397), and Lef1 (150–397), but not with Lef1 (175–397) and Lef1 (252–397). COS-7 cells were transfected with Myc-tagged constitutively active β-catenin and each of the Lef1 constructs indicated. Whole cell lysates (WCL) were immunoprecipitated with anti-Lef1. Proteins were transferred to membranes and detected by immunoblotting with anti-Myc. Whole cell lysate fractions were immunoblotted with anti-Myc or anti-Lef1 to demonstrate expression levels of β-catenin and the various Lef1 constructs, respectively.

We next asked whether amino acids 150–175 of Lef1 were necessary for Lef1ΔN and β-catenin-mediated activation of Top-Flash. As expected on the basis of results shown in Fig. 1, Lef1ΔN enhanced reporter expression and augmented β-catenin-dependent activation of Top-Flash (Fig. 3A). Lef1 (150–397) also stimulated gene transcription and cooperated with β-catenin to enhance reporter expression. However, Lef1 (175–397) and Lef1 (252–397) had modest effects on basal Top-Flash activity and failed to augment Top-Flash activation significantly beyond that observed with β-catenin alone (Fig. 3A). To determine whether Lef1 (175–397) and Lef1 (252–397) were competitive inhibitors of β-catenin-mediated activation of the Lef1-responsive promoter, we transfected cells with increasing amounts (100, 300, or 600 ng) of Lef1 (175–397) or Lef1 (252–397). Similar to results shown in Fig. 1, Lef1ΔN activated Top-Flash in a concentration-dependent manner. Neither Lef1 (175–397) nor Lef1 (252–397) augmented β-catenin activation; rather, both repressed β-catenin-dependent activation of Top-Flash, with Lef1 (252–397) acting as a competitive inhibitor at high concentrations (Fig. 3B). Thus, as summarized in Fig. 2A, β-catenin responsiveness of these Lef1 constructs corresponded to their ability to bind β-catenin. Additionally, the Lef1 C-terminal constructs that did not co-precipitate with β-catenin competitively inhibited reporter activity.

FIGURE 3.

Lef1ΔN β-catenin binding domain is required for β-catenin-mediated gene transcription in osteogenic cells. A, C2C12 cells were transfected with the Lef1 luciferase reporter plasmid Top-Flash, constitutively active β-catenin (300 ng), pcDNA3.1 (control), and Lef1ΔN (114–397), Lef1 (150–397), Lef1 (175–397), or Lef1 (252–397) as indicated. B, C2C12 cells were transfected as in A but with increasing amounts (100, 300, and 600 ng) of Lef1ΔN (114–397), Lef1 (175–397), or Lef1 (252–397). Luciferase activity was measured 24 h after transfection.

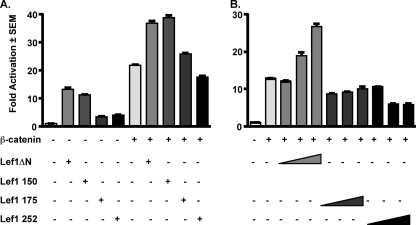

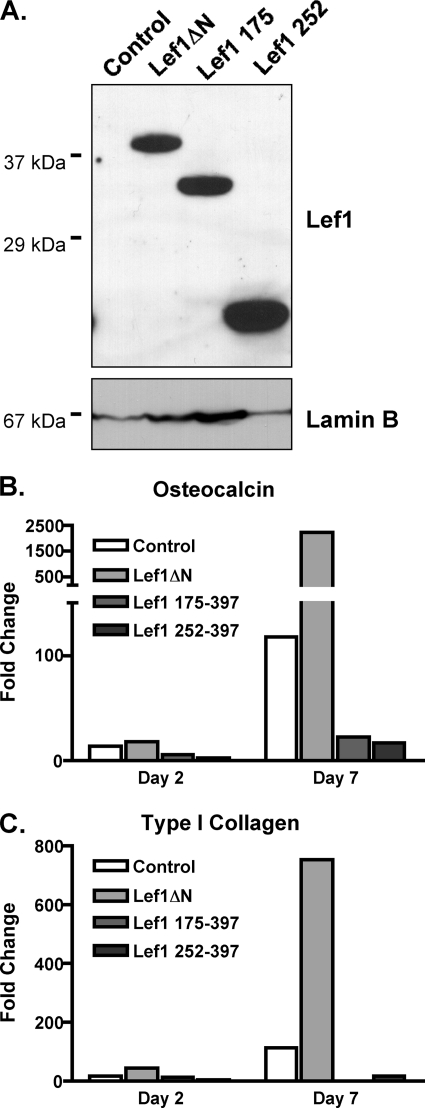

β-Catenin Binding Is Necessary for Lef1ΔN to Induce Genes Involved in Osteoblast Maturation

We demonstrated previously that stable expression of Lef1ΔN in osteoprogenitors accelerated expression of osteocalcin and type I collagen, genes associated with osteoblast differentiation (39). To determine whether the β-catenin binding region of Lef1ΔN contributed to this phenotype, we stably transduced C2C12 cells with Lef1ΔN, Lef1 (175–397), Lef1 (252–397), or a control retrovirus. The stably transduced cells were differentiated in osteogenic medium for 7 days. All of these Lef1 proteins were detected in the C2C12 cells before differentiation was induced (Fig. 4A). Their expression remained high throughout 7 days in culture (data not shown). Whereas Lef1ΔN enhanced osteocalcin and type I collagen mRNA levels as reported previously (39), Lef1 (175–397) and Lef1 (252–397) failed to induce their expression and in fact repressed expression of these late osteoblast differentiation genes below that observed in control cells transduced with the empty retrovirus (Fig. 4, B and C). Together, these results demonstrate that Lef1ΔN interacts with β-catenin in mesenchymal precursor and osteoblast lineage cells, but deletion of the internal β-catenin binding domain converts Lef1ΔN into a competitive inhibitor of β-catenin.

FIGURE 4.

Amino acids 114–175 of Lef1 are required for induction of osteocalcin and type 1 in differentiating osteoblasts. C2C12 cells were transduced with MSCV retroviruses producing Lef1ΔN, Lef1 (175–397), Lef1 (252–397), or no Lef1 (control). The various transduced C2C12 cell lines were differentiated in osteogenic media in the presence of BMP2. A, protein lysates were collected from undifferentiated cells, separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to Immobilon-P membrane, probed with anti-Lef1, and reprobed with anti-LaminB. B and C, RNA was collected after 2 and 7 days of osteogenic differentiation for qPCR. All data were normalized to murine actin. Fold change was calculated by normalizing values from each differentiated cell line to values from the corresponding cells prior to induction of differentiation.

Lef1ΔN Transgenic Mice Have Increased Trabecular Bone Mass

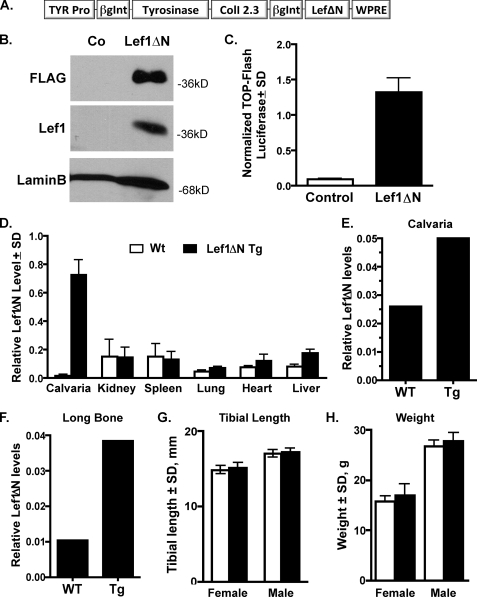

To verify that Lef1ΔN has a positive influence on osteoblast differentiation, we created a transgenic mouse in which Lef1ΔN was placed under the control of the 2.3-kb fragment of the type 1 collagen promoter (Fig. 5A). The (2.3)Col1-Lef1ΔN-FLAG construct produced the expected 38-kDa transgene product (Fig. 5B) and activated a Lef/Tcf reporter (Top-Flash), demonstrating that it is transcriptionally active (Fig. 5C). qPCR assays performed on RNA isolated from several organs of wild-type or transgenic mice with a FLAG-specific primer indicate that transgenic FLAG-Lef1ΔN mRNA was produced at high levels in bone but not in the kidney, spleen, lung, heart, or liver (Fig. 5D). Using gene-specific primers that detect total (i.e. endogenous plus exogenous) Lef1ΔN levels, we found that 2-fold more Lef1ΔN mRNA was present in the calvaria of transgenic animals (Fig. 5E), and 4-fold more was found in marrow-flushed long bones (Fig. 5F). Lef1ΔN transgenic mice had normal gross phenotypes, normal tibial lengths (Fig. 5G), and weighed the same as their nontransgenic littermates (Fig. 5H).

FIGURE 5.

Lef1ΔN transgenic mice. A, expression construct designed to place Lef1ΔN under the control of the 2.3-kb collagen type I promoter. TYR Pro is the promoter for tyrosinase, a mouse coat color gene, which aids in the detection of the transgene. The woodchuck hepatitis virus posttranscriptional regulatory element (WPRE) promotes the transport of RNA into the nucleus, thus increasing transgene expression. β-Globin intron sequences maintain proper orientation between promoter regions and open reading frames and promote transgene expression. B, immunoblot analyses demonstrating that U2OS osteosarcoma cells transfected with the (2.3)Col1a1-Lef1ΔN (Lef1ΔN) expression construct have high levels of exogenous C-terminal FLAG-tagged Lef1ΔN protein. A Lef1 antibody recognizing an endogenous C-terminal epitope also detects the exogenous Lef1ΔN. Untransfected U2OS cells were used as controls (Co). The lamin B immunoblot demonstrates relative protein levels in the two samples. C, Lef1ΔN transgene construct ((2.3)Col1a1-Lef1ΔN) activating Top-Flash in MC3T3 cells. Error bars, S.D. D, RT-PCRs on RNA isolated from various tissues of wild-type (Wt) or Lef1ΔN transgenic (Tg) mice demonstrating high exogenous Lef1ΔN mRNA levels in bone. E, total Lef1ΔN (endogenous + exogenous) mRNA levels in calvaria. F, total Lef1ΔN (endogenous + exogenous) mRNA levels in demarrowed long bones. G, tibia lengths of wild-type (female, n = 25; male, n = 15) and transgenic (female, n = 18; male, n = 9) mice were similar. H, weights of wild-type (female, n = 20; male, n = 13) and transgenic (female, n = 14; male, n = 7) mice were similar at sacrifice.

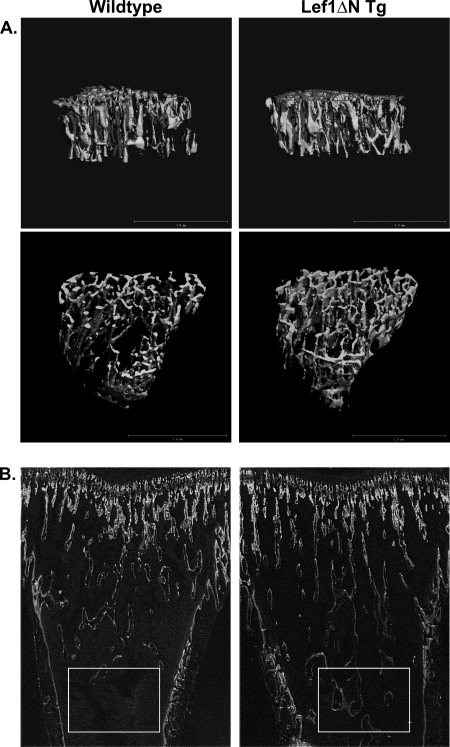

Analyses of bone structural parameters in 4-week-old female mice by μCT revealed significant increases in trabecular bone volume in transgenic animals. Trabecular bone volume was increased 17% in proximal tibias and 15% in the L5 vertebrae (Fig. 6A and Table 1). In proximal tibias, the increased bone volume corresponded to a 9% increase in trabecular number, and cancellous bone extended farther into the diaphysis of Lef1ΔN transgenic animals (Fig. 6B). Interestingly, no significant differences were observed in trabecular number in L5 vertebrae; however, trabecular thickness was increased 5% in transgenic mice (Table 1). The structure model index (SMI) represents the ratio of plates to rods in trabecular bone and is used to assess bone architecture qualitatively. SMI was decreased 5% in proximal tibias and 14% in L5 vertebrae, indicative of a more plate-like structure in trabecular bone in Lef1ΔN transgenic animals.

FIGURE 6.

Structural and histological analyses of tibial trabecular bone. A, tibias isolated from 4-week-old female mice and proximal regions analyzed by μCT scanning. Data were collected from a 0.7-mm-deep region of the secondary spongiosa, beginning 0.9 mm distal to the growth plate. These lateral (top) and caudal (bottom) cross-sectional views of left tibias are representative of animals in each group. B, fluorescent images of longitudinal sections from tibias of calcein-injected wild-type and Lef1ΔN transgenic mice. Trabecular bone extends farther into the diaphysis of the Lef1ΔN transgenic animals (boxed areas).

TABLE 1.

Structural parameters of trabecular bone in proximal tibia and L5 vertebrae

Results represent the mean ± S.D. Data with p < 0.05 are highlighted in boldface. Abbreviations: BV/TV, bone volume/tissue volume; TbN, trabecular number; TbTh, trabecular thickness; TbSp, trabecular spacing; ConnD, connectivity density; Tg, transgenic.

| Parameter | Tibia |

L5 vertebrae |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type (n = 8) | Lef1ΔN Tg (n = 8) | p value | Wild type (n = 19) | Lef1ΔN Tg (n = 13) | p value | |

| BV/TV, % | 9.26 ± 1.4 | 10.9 ± 1.3 | 0.029 | 13.5 ± 1.3 | 15.5 ± 1.9 | 0.0050 |

| TbN, 1/mm | 5.22 ± 0.320 | 5.68 ± 0.350 | 0.047 | 5.42 ± 0.502 | 5.49 ± 0.469 | 0.6073 |

| TbTh, mm | 0.031 ± 0.002 | 0.032 ± 0.002 | 0.502 | 0.030 ± 0.001 | 0.04 ± 0.002 | 0.032 |

| TbSp, mm | 0.192 ± 0.012 | 0.176 ± 0.011 | 0.584 | 0.187 ± 0.017 | 0.183 ± 0.016 | 0.5178 |

| ConnD, 1/mm3 | 210 ± 42 | 278 ± 93 | 0.085 | 499 ± 80 | 536 ± 121 | 0.1430 |

| SMI | 2.35 ±.14 | 2.24 ± 0.132 | 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.18 | 1.4 ± 0.223 | 0.0411 |

Transgene Expression of Lef1ΔN Enhances Osteoblast Activity

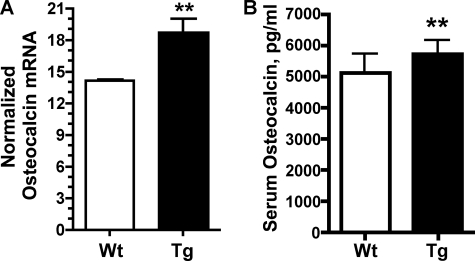

To determine the cellular mechanism responsible for increased bone mass in Lef1 transgenic animals, quantitative histomorphometry was performed on longitudinal sections of proximal tibias. Changes in the amount of osteoblast, osteoid, or osteoclast surface areas or the activities of these cells could explain the Lef1ΔN-dependent increases in bone mass. TRAP-stained trabecular bone revealed that osteoclast surface was not significantly altered in Lef1ΔN transgenic animals of either gender compared with wild-type littermates (Table 2). Osteoclast surface area is not necessarily indicative of osteoclast activity; therefore, the amount of eroded surface was also measured from TRAP-stained sections. Again, no difference in the amount of eroded surface was observed in transgenic animals compared with wild-type mice (Table 2). Thus, transgenic expression of Lef1ΔN in osteoblasts does not appear to affect osteoclast surface or activity. Osteoblast surface area, osteoid surface area, and osteoid thickness in trabecular bone sections were also unchanged in Lef1ΔN transgenic animals (Table 2); however, Lef1ΔN transgenic mice exhibited increased osteoblast activity (Fig. 6B). The amount of mineralizing surface per bone surface was increased 9% in Lef1ΔN transgenic mice, and mineral apposition rates were increased 14%. Bone formation rates (BFRs) were markedly increased in the Lef1ΔN transgenic mice, showing a 26% increase in BFR per bone surface and a 2.4-fold increase in BFR per tissue volume (Table 2). Osteocalcin mRNA levels were also elevated in cortical bones of Lef1ΔN transgenic animals (Fig. 7A), and serum osteocalcin levels were increased in 8-week-old Lef1ΔN transgenic mice (Fig. 7B). These data are consistent with increased osteoblast activity in the Lef1ΔN transgenic animals and with osteocalcin expression levels in our in vitro studies (Fig. 4B). The expression levels of other osteoblast and osteocyte genes (e.g. Runx2, Sp7 (osterix), alkaline phosphatase, Rankl, Opg, Dmp1, and sclerostin) were not changed in marrow-flushed long bones (data not shown). Together, our results indicate that Lef1ΔN is a promoter of osteoblast differentiation and bone formation.

TABLE 2.

Histomorphometry data from trabecular bone in proximal tibia

Results represent the mean ± S.D. Data with p < 0.05 are highlighted in boldface. Abbreviations: OcS, osteoclast surface; BS, bone surface; OS, osteoid surface; O Th, osteoid thickness; ES, eroded surface; BS, bone surface; MS, mineralized surface; MAR, matrix apposition rate; TV, tissue volume; BV, bone volume.

| Parameter | Wild type (n = 7–11) | Lef1ΔN Tg (n = 7–10) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| OcS/BS, % | 25.4 ± 6.08 | 23.7 ± 5.27 | 0.422 |

| ObS/BS, % | 11.9 ± 4.25 | 15.4 ± 5.06 | 0.160 |

| OS/BS, % | 12.2 ± 4.49 | 15.4 ± 5.10 | 0.210 |

| O Th., μm | 1.80 ± 0.378 | 1.68 ± 0.373 | 0.550 |

| ES/BS, % | 5.65 ± 1.91 | 5.08 ± 2.16 | 0.612 |

| Wild type (n = 12) | Lef1ΔNTg (n = 12) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MS/BS, % | 49.4 ± 6.04 | 53.7 ± 5.25 | 0.052 |

| MAR, μm/d | 3.8 ± .98 | 4.34 ± 0.86 | 0.1044 |

| BFR/BS, μm3/μm2/y | 677 ± 146 | 854 ± 201 | 0.0112 |

| BFR/TV, %/y | 269 ± 103 | 597 ± 245 | 0.0001 |

| BFR/BV, %/y | 4,844 ± 779 | 5,389 ± 1,056 | 0.1490 |

FIGURE 7.

Lef1ΔN transgenic mice have increased osteocalcin levels. A, osteocalcin mRNA expression ratios were increased in 8-week-old male transgenic (Tg) animals. Results represent the mean of three independent experiments ± S.D. (error bars). **, p = 0.01. B, osteocalcin serum protein levels were increased by 13% in male transgenic animals (wild-type (Wt): n = 5; Tg, n = 6). **, p ≤ 0.1.

DISCUSSION

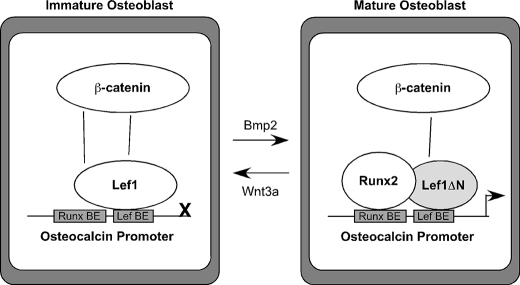

The canonical Wnt pathway has emerged as a major target for new anabolic therapies, including those aimed at repairing fractures and treating osteoporosis (1, 3, 4). Canonical Wnt signaling ultimately alters gene transcription to control cell survival, proliferation, and differentiation. Members of the Lef1/Tcf7 family of transcription factors are terminal effectors in specifying these changes in gene expression, but the roles of these important mediators of the Wnt and β-catenin response throughout osteoblast maturation are incompletely understood. We observed previously that the full-length Lef1 protein is expressed early but then disappears as osteoblast differentiation proceeds (28), whereas the ΔN isoform is undetectable in undifferentiated cells, but is expressed during osteoblast maturation (39) (Fig. 8). Stable expression of Lef1 in osteoblast cells prevented mineralization (28), whereas retroviral expression of Lef1ΔN in multipotent progenitor cells accelerated the production of osteocalcin and type I collagen (39). In this study we sought to identify the mechanism whereby Lef1ΔN induces terminal differentiation in osseous cells during the late stages of differentiation and to verify a role for Lef1ΔN in bone formation in vivo. Lef1ΔN interacted with β-catenin through an internal binding domain resulting in the expression of genes involved in osteoblast terminal differentiation. Tissue-directed expression of the Lef1ΔN transgene in osteoblast cells increased trabecular bone volume density by promoting osteoblast maturation and bone formation rates. These data suggest that temporal and regulated expression of Lef1 isoforms contribute to bone formation and β-catenin responsiveness.

FIGURE 8.

Model of Lef1 and Lef1ΔN activities in osteoblasts. Immature osteoblasts express Lef1 but not Lef1ΔN. Lef1 blocks Runx2-dependent trans-activation of osteocalcin promoter. Bmp2 facilitates osteoblast maturation and increases Lef1ΔN expression, whereas Wnt3a prevents osteoblast maturation and Lef1ΔN production. In mature cells, Lef1 levels decline and are replaced by Lef1ΔN, which binds the osteocalcin promoter but does not inhibit Runx2 trans-activation of the osteocalcin promoter.

Transgenic expression of Lef1ΔN increased trabecular bone volume in the proximal tibia and L5 vertebrae. Moreover, Lef1ΔN transgenic mice had lower SMI scores, demonstrating that the Lef1ΔN transgene improved trabecular bone architecture in addition to increasing bone volume. Lef1ΔN-dependent elevations in bone mass resulted from enhanced osteoblast activity, as evidenced by higher bone formation rates and mineralized surface areas, as well as elevated osteocalcin production. We showed previously that Lef1, but not Lef1ΔN, represses Runx2-induced transcription of the osteocalcin promoter (43). The Lef1 and Runx2 binding sites in the osteocalcin promoter are separated by just 4 bp. Lef1 interferes with the ability of Runx2 to bind to its proximal site within the osteocalcin promoter; but Lef1ΔN does not (39). Thus, we favor the hypothesis that Lef1ΔN increases osteocalcin gene expression by allowing Runx2 greater access to its binding site in the osteocalcin promoter and integrating β-catenin co-activation (Fig. 8). Other well described osteoblast genes (e.g. Runx2, Sp7, alkaline phosphatase) were not significantly or consistently altered in bones of the Lef1ΔN transgenic mice.

Our data show that an alternative β-catenin binding site lies within a region encompassing residues 114 and 175 of Lef1, with amino acids 150–175 being required for the interaction with Lef1ΔN. Lef1ΔN interacted with β-catenin via it first 61 amino acids in osteoblasts and enhanced terminal differentiation. Lef1ΔN did not co-immunoprecipitate with as much β-catenin as Lef1 did (Fig. 2B); thus, it is tempting to speculate that Lef1ΔN binds β-catenin with lower affinity. This region was described previously as a context-dependent regulatory domain of Lef1 because it facilitates interactions with numerous transcriptional co-factors (17). Daniels and Weis showed that β-catenin binds the central region of Lef1 in vitro and displaces Groucho/TLE co-repressors from Lef1 (252–397) in GST affinity purification assays; however, they did not perform any transcription assays to demonstrate functional activity or verify the interactions in cellular lysates (44). In our experimental models, constructs (Lef1 (175–397) and (252–397)) that are similar but not identical to those used by Daniels and Weis had modest effects on basal Top-Flash activity and failed to bind β-catenin or significantly augment transcription beyond that observed with β-catenin alone. In contrast, a slightly longer Lef1 protein, Lef1 (150–397), associated with β-catenin in cellular lysates and cooperated with β-catenin to induce gene expression. A significant difference between these experiments is that our studies were conducted in osteogenic cells where adapter molecules and cofactors are available. Interestingly, Lef1ΔN and β-catenin had different effects on a Lef1-responsive promoter in osteoblasts than in T lymphocytes (18) (Fig. 3). These results suggest that cell type-specific factors contribute to Lef1ΔN/β-catenin interactions in vivo.

Lef1 and Tcf7 genes use alterative promoters within noncoding regions to transcribe ΔN isoforms that lack the primary β-catenin binding domain (18, 29, 30). Differential expression of the full-length and short ΔN isoforms was described previously in several tissues (34–38, 45). In some cells (e.g. T cells, tumors, epidermal stem cells) Lef1ΔN inhibits proliferation and differentiation signals emanating from the canonical Wnt pathway. In other cells (e.g. granulocytes) Lef1ΔN is sufficient to rescue defects caused by Lef1 deficiency (34–38, 45). In this report, we demonstrate that Lef1ΔN is not a competitive inhibitor of β-catenin-dependent transcription in mesenchymal cells, but retains the ability to bind β-catenin and induce terminal differentiation of osteoblasts. We recently showed that Bmp2 and Runx2 stimulate Lef1ΔN expression at the same time as Lef1 levels decline (28, 39). Interestingly, Wnt3a suppressed basal and Bmp2-induced Lef1ΔN transcripts in osteoblasts (28, 39), consistent with the Wnt3a ability to inhibit osteoblast differentiation (6, 46). It was shown recently that YY1 is a repressor of Lef1ΔN transcription (33), but whether or not it controls Lef1ΔN expression in osteoblasts remains to be determined. Together our data indicate that Lef1ΔN may replace Lef1 in differentiating osteoblasts to fine-tune or modify β-catenin-dependent gene regulation.

The Wnt pathway exerts direct and indirect regulatory control over proliferation and differentiation of cells in bone and most other renewable tissues. Such regulation relies upon the activity of transcription factors, including Lef1 and Tcf7 proteins. Previous work by our laboratory demonstrated that Lef1 is expressed in proliferating osteoblasts and acts to block osteoblast differentiation by down-regulating osteocalcin (28). Conversely, expression of Lef1ΔN is only detectable in mature osteoblasts, and stable expression of Lef1ΔN in C2C12 myo-osteoprogenitor cells increased osteocalcin expression (39). This paper adds in vivo support for the prodifferentiation role that Lef1ΔN exerts on osteoblasts and for the first time demonstrates that Lef1ΔN promotes bone formation. We also found Lef1ΔN associated with β-catenin and enhanced activation of a Wnt-responsive promoter in osseous cells. Taken together, we conclude that Lef1ΔN physically and functionally interacts with β-catenin in mature osteoblasts, and this interaction regulates the transcription of osteoblast differentiation genes to promote bone formation. Additional studies are needed to define the role of Lef1ΔN in augmenting the responses of emerging anabolic therapies targeting the canonical Wnt pathway.

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the Mayo Clinic Biomaterials and Quantitative Histomorphometry Core Laboratory for sharing their expertise. We specifically thank Glenda Evans, Dr. Farhan Syed, Dr. Theresa Hefferan, and Dr. Meghan McGee-Lawrence for help in assessing the histological data; Dr. Marian Waterman for insightful discussions; and Dr. Brendan Lee for sharing plasmids.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants AR050074 and AR048147-S1.

- Lef

- lymphoid enhancer-binding factor

- BFR

- bone formation rate

- Bmp

- bone morphogenic protein

- Lef1ΔN

- Lef1 deleted amino terminus

- μCT

- microcomputed tomography

- MEM

- minimal essential medium

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR

- SMI

- structure model index

- Tcf

- T cell factor

- Tcf7L

- Tcf7-like

- TRAP

- tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase.

REFERENCES

- 1. Khosla S., Westendorf J. J., Oursler M. J. (2008) J. Clin. Invest. 118, 421–428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Williams B. O., Insogna K. L. (2009) J. Bone Miner. Res. 24, 171–178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Secreto F. J., Hoeppner L. H., Westendorf J. J. (2009) Curr. Osteoporosis Rep. 7, 64–69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hoeppner L. H., Secreto F. J., Westendorf J. J. (2009) Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 13, 485–496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Almeida M., Han L., Bellido T., Manolagas S. C., Kousteni S. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 41342–41351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Boland G. M., Perkins G., Hall D. J., Tuan R. S. (2004) J. Cell Biochem. 93, 1210–1230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kang S., Bennett C. N., Gerin I., Rapp L. A., Hankenson K. D., Macdougald O. A. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 14515–14524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bennett C. N., Ouyang H., Ma Y. L., Zeng Q., Gerin I., Sousa K. M., Lane T. F., Krishnan V., Hankenson K. D., MacDougald O. A. (2007) J. Bone Miner. Res. 22, 1924–1932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mikels A. J., Nusse R. (2006) PLoS Biol. 4, e115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yadav V. K., Ryu J. H., Suda N., Tanaka K. F., Gingrich J. A., Schütz G., Glorieux F. H., Chiang C. Y., Zajac J. D., Insogna K. L., Mann J. J., Hen R., Ducy P., Karsenty G. (2008) Cell 135, 825–837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Smith E., Frenkel B. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 2388–2394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Day T. F., Guo X., Garrett-Beal L., Yang Y. (2005) Dev. Cell 8, 739–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hill T. P., Später D., Taketo M. M., Birchmeier W., Hartmann C. (2005) Dev. Cell 8, 727–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Holmen S. L., Zylstra C. R., Mukherjee A., Sigler R. E., Faugere M. C., Bouxsein M. L., Deng L., Clemens T. L., Williams B. O. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 21162–21168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Glass D. A., 2nd, Bialek P., Ahn J. D., Starbuck M., Patel M. S., Clevers H., Taketo M. M., Long F., McMahon A. P., Lang R. A., Karsenty G. (2005) Dev. Cell 8, 751–764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Westendorf J. J., Kahler R. A., Schroeder T. M. (2004) Gene 341, 19–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Arce L., Yokoyama N. N., Waterman M. L. (2006) Oncogene 25, 7492–7504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hovanes K., Li T. W., Munguia J. E., Truong T., Milovanovic T., Lawrence Marsh J., Holcombe R. F., Waterman M. L. (2001) Nat. Genet. 28, 53–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Filali M., Cheng N., Abbott D., Leontiev V., Engelhardt J. F. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 33398–33410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Atcha F. A., Munguia J. E., Li T. W., Hovanes K., Waterman M. L. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 16169–16175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Travis A., Amsterdam A., Belanger C., Grosschedl R. (1991) Genes Dev. 5, 880–894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Oosterwegel M., van de Wetering M., Clevers H. (1993) Thymus 22, 67–81 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhou P., Byrne C., Jacobs J., Fuchs E. (1995) Genes Dev. 9, 700–713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kratochwil K., Dull M., Farinas I., Galceran J., Grosschedl R. (1996) Genes Dev. 10, 1382–1394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mariadason J. M., Bordonaro M., Aslam F., Shi L., Kuraguchi M., Velcich A., Augenlicht L. H. (2001) Cancer Res. 61, 3465–3471 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hadjiargyrou M., Lombardo F., Zhao S., Ahrens W., Joo J., Ahn H., Jurman M., White D. W., Rubin C. T. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 30177–30182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shibamoto S., Winer J., Williams M., Polakis P. (2004) Exp. Cell Res. 292, 11–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kahler R. A., Galindo M., Lian J., Stein G. S., van Wijnen A. J., Westendorf J. J. (2006) J. Cell. Biochem. 97, 969–983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Van de Wetering M., Castrop J., Korinek V., Clevers H. (1996) Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 745–752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hovanes K., Li T. W., Waterman M. L. (2000) Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 1994–2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hoppler S., Kavanagh C. L. (2007) J. Cell Sci. 120, 385–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Li T. W., Ting J. H., Yokoyama N. N., Bernstein A., van de Wetering M., Waterman M. L. (2006) Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 5284–5299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yokoyama N. N., Pate K. T., Sprowl S., Waterman M. L. (2010) Nucleic Acids Res. 38, 6375–6388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Merrill B. J., Gat U., DasGupta R., Fuchs E. (2001) Genes Dev. 15, 1688–1705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Niemann C., Owens D. M., Hülsken J., Birchmeier W., Watt F. M. (2002) Development 129, 95–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wang W., Ji P., Steffen B., Metzger R., Schneider P. M., Halfter H., Schrader M., Berdel W. E., Serve H., Müller-Tidow C. (2005) Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 37, 173–180 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Skokowa J., Cario G., Uenalan M., Schambach A., Germeshausen M., Battmer K., Zeidler C., Lehmann U., Eder M., Baum C., Grosschedl R., Stanulla M., Scherr M., Welte K. (2006) Nat. Med. 12, 1191–1197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Takeda H., Lyle S., Lazar A. J., Zouboulis C. C., Smyth I., Watt F. M. (2006) Nat. Med. 12, 395–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hoeppner L. H., Secreto F., Jensen E. D., Li X., Kahler R. A., Westendorf J. J. (2009) J. Cell. Physiol. 221, 480–489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. van Genderen C., Okamura R. M., Fariñas I., Quo R. G., Parslow T. G., Bruhn L., Grosschedl R. (1994) Genes Dev. 8, 2691–2703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Noh T., Gabet Y., Cogan J., Shi Y., Tank A., Sasaki T., Criswell B., Dixon A., Lee C., Tam J., Kohler T., Segev E., Kockeritz L., Woodgett J., Müller R., Chai Y., Smith E., Bab I., Frenkel B. (2009) PLoS ONE 4, e5438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zhou G., Zheng Q., Engin F., Munivez E., Chen Y., Sebald E., Krakow D., Lee B. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 19004–19009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kahler R. A., Westendorf J. J. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 11937–11944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Daniels D. L., Weis W. I. (2005) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12, 364–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Willinger T., Freeman T., Herbert M., Hasegawa H., McMichael A. J., Callan M. F. (2006) J. Immunol. 176, 1439–1446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. de Boer J., Siddappa R., Gaspar C., van Apeldoorn A., Fodde R., van Blitterswijk C. (2004) Bone 34, 818–826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]