Abstract

P2X7 receptors have emerged as potential drug targets for the treatment of medical conditions such as e.g. rheumatoid arthritis and neuropathic pain. To assess the impact of pharmaceuticals on P2X7, we screened a compound library comprising approved or clinically tested drugs and identified several compounds that augment the ATP-triggered P2X7 activity in a stably transfected HEK293 cell line. Of these, clemastine markedly sensitized Ca2+ entry through P2X7 to lower ATP concentrations. Extracellularly but not intracellularly applied clemastine rapidly and reversibly augmented P2X7-mediated whole-cell currents evoked by non-saturating ATP concentrations. Clemastine also accelerated the ATP-induced pore formation and Yo-Pro-1 uptake, increased the fractional NMDG+ permeability, and stabilized the open channel conformation of P2X7. Thus, clemastine is an extracellularly binding allosteric modulator of P2X7 that sensitizes P2X7 to lower ATP concentrations and facilitates its pore dilation. The activity of clemastine on native P2X7 receptors, Ca2+ entry, and whole-cell currents was confirmed in human monocyte-derived macrophages. Similar effects were observed in murine bone marrow-derived macrophages. Consistent with the data on recombinant P2X7, clemastine augmented the ATP-induced cation entry and Yo-Pro-1 uptake. In accordance with the observation that P2X7 controls the cytokine release from LPS-primed macrophages, we found that clemastine augmented the IL-1β release from LPS-primed human macrophages. Collectively, these data point to a sensitization of the recombinantly or natively expressed human P2X7 receptor toward its physiological activator, ATP, possibly leading to a modulation of macrophage-dependent immune responses.

Keywords: Allosteric Regulation, ATP, Interleukin, Ion Channels, Macrophage, Purinergic Receptor

Introduction

ATP-gated ion channels of the P2X receptor family comprise seven members, P2X1–P2X7, that exhibit a marked diversity with respect to their activation and inactivation kinetics, ATP affinity, and modulator sensitivity (1, 2). P2X7 is a low affinity ATP receptor that is expressed in many tissues and cell types. In the central nervous system, P2X7 expression has been detected mainly in glia cells, including astrocytes, microglia, and oligodendrocytes (3). A neuronal expression has been reported but may be restricted to the presynaptic terminals (4). In the periphery, the strongest P2X7 expression is found in various cell types of the immune system. Functionally relevant activities have been demonstrated in many cellular systems, including macrophages, monocytes, and mast cells (e.g. Refs. 5 and 6).

When challenged with the physiological agonist ATP or with the more potent synthetic agonist 2′,3′-O-(4-benzoyl-benzoyl)-ATP (1), P2X7 channel opening gives rise to poorly selective and slowly inactivating cation currents. When stimulated repetitively, P2X7 current amplitudes increase over time (7). In the continuous presence of ATP, P2X7 channels develop or recruit a “dilated” pore, which allows permeation of large organic cations such as NMDG+,3 Yo-Pro-1, and ethidium (8, 9). Although several mechanisms have been proposed, the pore dilation or recruitment of other pore-forming proteins by the activated P2X7 is not yet fully understood. When P2X7 stimulation is continued over long time periods, the long lasting channel activity, the Ca2+ permeability, and the pore dilation may eventually trigger membrane blebbing and cell death (10).

Because P2X7 is reportedly involved in many pathophysiological processes, including macrophage and microglia activation (11, 12), astrocyte proliferation, and gliotransmitter release (3), P2X7 has been suggested as a promising target for pharmacological modulation. From studies in genetically engineered mouse models that are lacking P2X7 receptor expression in distinct tissues, it was shown that osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis (e.g. Ref. 13), and neuropathic pain (e.g. Ref. 14) are pathophysiological settings in which P2X7 blockade may be desirable. Consequently, significant effort has been undertaken by pharmaceutical companies to develop and approve selective P2X7 blockers (for a review, see Ref. 15).

In an attempt to identify P2X receptor-modulating drugs, we screened a compound library that comprises 1040 approved low molecular weight drugs or drugs that have reached phase II/III clinical trials. To our surprise, we identified a marked potentiation of human P2X7 by the H1 antihistaminic clemastine. In this study, we provide evidence for an as yet unidentified positive allosteric modulation of P2X7 by clemastine. The mode of action was independent of H1 receptors but relied on a sensitization of P2X7 to lower ATP concentrations. In addition, the relative NMDG+ permeability was increased, and Yo-Pro-1 uptake was accelerated, indicating a facilitated dilation of the P2X7 pore. In human blood-derived macrophages, clemastine potentiated P2X7-mediated Ca2+ entry, cation currents, and IL-1β secretion. We conclude that clemastine is a positive allosteric modulator of recombinant and natively expressed human P2X7.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture and Reagents

Human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells stably transfected with the human P2X7 (hP2X7) receptor (HEKhP2X7) were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 4.5 mm d-glucose and supplemented with 10% FCS (Biochrom, Berlin, Germany), 2 mm l-glutamine, and 0.05 mg/ml Geneticin (Invitrogen) at 37 °C in a humidified 7% CO2 incubator. Human monocyte-derived macrophages were prepared and cultured as described (16) with some modifications. Briefly, human blood samples were taken from healthy volunteers (procedure approved by the local ethical committee). Monocytes were isolated from buffy coat fractions by one-step density gradient centrifugation (Histopaque 1077, Sigma-Aldrich). After washing with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing no Ca2+ and Mg2+, cells were resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium (PAA Laboratories, Pasching, Austria) with 10% autologous fibrin-depleted plasma, 2 mm l-glutamine, non-essential amino acids, 1 mm sodium pyruvate, 100 mg/ml streptomycin, and 100 units/ml penicillin (complete RPMI medium). Murine macrophages were isolated and differentiated from sacrificed adult C57BL/6 mice by flushing the bone marrow of lower limb bones with PBS. Cell suspensions were centrifuged and resuspended in Iscove's modified DMEM (PAA Laboratories) supplemented with 10% FCS, 50 μm mercaptoethanol, 100 mg/ml streptomycin, 100 units/ml penicillin, 2 ng/ml murine SCF-1, and 5 ng/ml murine IL-3 (both from Peprotech, Hamburg, Germany). Cells were seeded like human macrophages, and medium was changed after 24 h. Iscove's modified DMEM without SCF-1 and IL-3 was added. Murine splenocytes were acutely dissociated as described (17). Tissue extraction from mice was notified and conducted under protocols in accordance with the governmental animal care committee of Saxony, Germany. For single cell [Ca2+]i analysis and Yo-Pro-1 fluorescence measurements, 5 × 105 cells were plated on 25-mm glass coverslips. The same number of cells was seeded in 35-mm cell culture dishes (Greiner, Kremsmünster, Austria) for electrophysiological patch clamp or IL-1β release experiments. Cells were allowed to adhere for 2 h, and non-adhesive cells were discarded. Adherent cells were maintained in complete RPMI medium for 5–7 days to promote the spontaneous differentiation of monocytes to macrophages. 12–24 h before measurement, the medium was changed, and 100 ng/ml LPS was added to the medium.

Clemastine fumarate and A-438079 hydrochloride were purchased from Tocris (Bristol, UK). Adenosine 5′-triphosphate disodium salt (ATP), carbenoxolone disodium salt, nigericin sodium salt, Triton X-100, and ivermectin were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Stock solutions were prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (100 mm A-438079), in water (500 mm ATP and 100 mm carbenoxolone), or in ethanol (5 mg ml−1 nigericin) or freshly prepared in the respective buffers (5 mm clemastine). Aliquots thereof were stored at −20 °C, and the ultimate dilutions were made daily with the appropriate bath solutions. ATP- and clemastine-containing solutions were readjusted to pH 7.3–7.4.

Intracellular Ca2+ Analysis and Yo-Pro-1 Accumulation Assay in Cell Suspensions

All fluorometric assays in cell suspensions were conducted in a 384-well microtiter plate format. HEK cells were grown to confluent monolayers in 75-cm2 cell culture flasks, harvested with trypsin, and resuspended in DMEM. For [Ca2+]i measurements, cells were incubated with fluo-4/AM (4 μm; Invitrogen) for 30 min at 37 °C, washed (5 min at 100 × g), and resuspended in HBS buffer (standard divalent cations (DIC)) containing 130 mm NaCl, 6 mm KCl, 1 mm CaCl2, 1 mm MgCl2, 5.5 mm d-glucose, and 10 mm HEPES adjusted to pH 7.4 with NaOH. Cells were dispensed into 384-well low-binding, pigmented clear bottom microplates (Corning, Lowell, MA), and modulators were added to obtain final concentrations as indicated. For the primary screening, wells were prefilled with individual compounds of the Spectrum Collection compound library (MicroSource Discovery Systems, Gaylordsville, CT) or with the solvent (0.25% dimethyl sulfoxide) to reach a final compound concentration of 20 μm upon addition of the fluo-4-loaded cell suspension. Measurement was executed with a filter-based plate reader device (Polarstar Omega, BMG Labtech, Offenburg, Germany), applying 485 ± 6- and 520 ± 10-nm band pass filters for excitation and emission, respectively. Microtiter plates were repetitively scanned every 16 s in the fast scanning mode of the device. After 10 base-line cycles, ATP was injected into each well, and fluorescence intensities were followed for 10 min after agonist injection (40 cycles). Data were extracted, exported, and normalized to the initial intensities before viewing them and annotating hit lists. Data of compounds that exhibit a strong fluorescence were identified and discarded. Compounds that were found to be positive or toxic in previous screenings on other target molecules were discarded from the initial hit list. To obtain concentration-response functions, various ATP and modulator concentrations were added, and data were subjected to nonlinear curve fitting applying a four-parameter Hill equation (Emin, Emax, EC50, and Hill coefficient).

The procedure for Yo-Pro-1 accumulation assays was similar, but an HBS buffer with low concentrations of divalent cations (low DIC) was used (HBS with only 0.1 mm CaCl2 and no MgCl2). The large cationic fluorescent DNA dye Yo-Pro-1 (1 μm; iodide salt; Invitrogen) was added directly before starting the experiment. Yo-Pro-1 fluorescence developing after ATP stimulation was followed for 90 min.

Single Cell Imaging of [Ca2+]i and of Yo-Pro-1 Uptake in Human Macrophages

The intracellular concentration of free ionized calcium ([Ca2+]i) in single cells was measured using the fluorescent indicator fura-2/AM (Invitrogen). Human monocyte-derived macrophages (hMDM) were loaded with fura-2/AM (3 μm) for 30 min at 37 °C in HBS buffer containing standard DIC and supplemented with 0.5% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA). Subsequently, coverslips were rinsed with HBS (standard DIC) without BSA, mounted in a bath chamber, and viewed in an inverted epifluorescence microscope (Fluar 10×/0.5 or F-Fluar 40×/1.3; Axiovert 100 microscope, Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany). Fluorescence was excited with a fiber-coupled monochromator device (Polychrome V, Till-Photonics, Gräfelfing, Germany) at alternating wavelengths of 340, 358, and 380 nm, respectively. Fluorescence emission was imaged (Sensicam HR, PCO, Kehlheim, Germany) through a dichroic beam splitter (DCXR-510, Chroma, Rockingham, VT) and a 515-nm long pass filter (OG 515, Schott, Jena, Germany). Fluorescence intensities were averaged over regions of interest that covered single cells. Background signals were obtained after detaching cells from the glass coverslip and subtracted from the data. The [Ca2+]i was calculated with a spectral fingerprinting method as described elsewhere (18). In each imaging experiment, 30–50 cells with macrophage-like morphology (spread, flat cells with round or oval circumference) were measured and averaged. 4–12 measurements from different donors were performed to calculate mean peak amplitudes and to test for statistical significance by applying an unpaired Student's t test.

Yo-Pro-1 fluorescence was imaged in the same setup with an excitation wavelength of 480 nm. hMDM were kept in HBS with low DIC, Yo-Pro-1 was added at a final concentration of 1 μm, and the uptake was followed in 5-s intervals. The slope of the Yo-Pro-1 fluorescence increase was determined before and after addition of clemastine (30 μm) in the presence of 0.3 mm ATP. In some experiments, hMDM were preincubated with the pannexin inhibitor carbenoxolone (100 μm) for 30 min prior to stimulation with ATP. To visualize all cells and for defining regions of interest for subsequent quantitative analysis, Triton X-100 (0.1%, w/v) was added.

Electrophysiological Procedures

Whole-cell Recording

HEKhP2X7 cells or human LPS-primed monocyte-derived macrophages were seeded in poly-l-lysine-coated (Sigma-Aldrich) culture dishes. Whole-cell recordings were made at room temperature and at a holding potential of −60 mV using an EPC9 amplifier and Pulse software (HEKA, Lambrecht, Germany). The extracellular solution for seal formation (standard divalent cation concentration-containing bath = standard DIC), also used during some of the experiments, was made up of 147 mm NaCl, 2 mm KCl, 2 mm CaCl2, 1 mm MgCl2, 13 mm d-glucose, and 10 mm HEPES (∼305 mosmol liter−1; pH 7.3 with NaOH). For most of the trials, cells were superfused after the whole-cell configuration had been achieved with a low divalent cation-containing bath (low DIC) prepared thereof by omitting MgCl2 and lowering the CaCl2 content to 0.1 mm. The pipette solution comprised in both cases 147 mm KCl, 10 mm HEPES, and 10 mm EGTA (∼300 mosmol liter−1; pH 7.3 with KOH). Effects of clemastine on P2X7 pore dilation were assessed with a bath solution containing the large monovalent cation N-methyl-d-glucamine (NMDG+; 154 mm), HEPES (10 mm), and d-glucose (13 mm; ∼310 mosmol liter−1; pH 7.3 with HCl). The respective pipette solution included 147 mm NaCl, 10 mm HEPES, and 10 mm EGTA (∼310 mosmol liter−1; pH 7.3 with NaOH). When filled with one of the above pipette solutions, patch pipettes for whole-cell recordings had a resistance of 2–4 megaohms.

Drugs were focally delivered by means of the application cannula (100-μm inner diameter) of a solenoid valve-driven pressurized superfusion system (DAD-12, Adams and List) placed in vicinity (∼50 μm) of the cell under investigation. Solution exchange was thereby completed within ∼200 ms as estimated from the 20–80% rise time (167 ± 18 ms; n = 15) of the peak response to a 30% dilution of the standard bath applied to the open tip of the patch pipette.

Series resistance (8–20 megaohms) was compensated by 60–80%. Experiments during which series resistance changed by more than 20% were not further analyzed. ATP-induced currents, sampled at 5 kHz and filtered at 1.7 kHz, were measured as peak responses with respect to the holding current level. They were normalized for differences in cell size (membrane capacitance), and current densities (pA pF−1) are reported.

The time constant for the onset (τon) of clemastine action on ATP-induced currents (IATP) was extracted by a monoexponential function,

where t is time and A0 and A1 represent the starting and end amplitudes of the function, respectively. This function was also used to describe the time course of ATP-induced changes in hP2X7 permeability. The offset of clemastine action was better described by the biexponential function,

where τoff1 and τoff2 and A1 and A2 indicate the time constants and relative amplitude contributions for the fast and slow recoveries from the clemastine effect, respectively.

Sets of ATP concentration response data were fitted to a three-parameter Hill function using SigmaPlot 9.0 (Systat Software, Point Richmond, CA),

|

where I is the experimentally observed current in response to agonist concentration [A], Imax is the extrapolated maximum current, EC50 is the agonist concentration producing 50% of Imax, and nH is a slope factor (Hill coefficient).

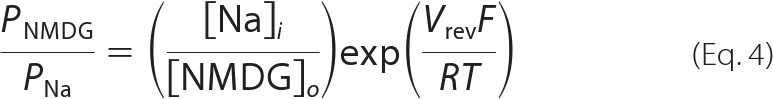

Time- and activation-dependent changes in the relative permeability (P) of NMDG+ with respect to Na+ of P2X7 were computed from changes in the reversal potential (Vrev) of ATP-induced currents, assuming ion activities of 0.75 for both cations (19), by a transform of the Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz equation for bi-ionic conditions,

|

where [Na]i and [NMDG]o are the concentrations of Na+ and NMDG+ in the intracellular and extracellular solutions, respectively; F is the Faraday constant; R is the universal gas constant; and T is the absolute temperature.

Single Channel Recording

P2X7-mediated single channel currents were, in some preliminary experiments, recorded in the outside-out patch configuration and later on in the inside-out mode of the patch clamp technique. Given that the conductance of hP2X7 is relatively small (20), patches were clamped at a strong negative holding potential of −120 mV to increase cation driving force. The cell-attached recording configuration served eventually to probe for possible P2X7-associated large conductance (∼400 pS) Z pores (21). In these experiments, the patch underlying the pipette was clamped to −40 mV.

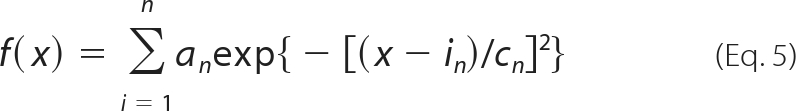

The bath containing low DIC and the KCl pipette solution for outside-out recordings were the same as those used during the whole-cell experiments (see above). In cell-attached experiments, low DIC served as bath as well as pipette filling solution. Inside-out patches were excised in an intracellular solution containing 147 mm KCl, 10 mm HEPES, and 1 mm EGTA (adjusted to ∼305 mosmol liter−1 with sucrose; pH 7.3 with KOH). The pipette (extracellular) solution comprised 147 mm NaCl, 10 mm HEPES, and 1 mm EGTA (adjusted to ∼305 mosmol liter−1 with sucrose; pH 7.3 with NaOH). When filled with one of the above pipette solutions, patch pipettes for single channel recordings had a resistance of 10–15 megaohms. Drugs (ATP and clemastine) were either superfused (∼2 ml min−1) in outside-out or cell-attached recordings or added to the pipette solution for inside-out recordings. Single channel data were sampled at a bandwidth of 10 kHz, low pass-filtered at 5 kHz (Bessel, −3 decibels), and digitized at 12.5 kHz. For analysis, recordings were filtered at 1 kHz, resulting in an effective cutoff frequency of 0.98 kHz and an associated dead time of 182 μs. Base-line correction, artifact removal, and data idealization were performed by means of the QuB software suite, which uses a recursive Viterbi algorithm known as “segmental k-means” for event detection (22). The mean amplitude of unitary hP2X7 channel currents was derived from all-point amplitude histograms of the idealized data containing 3,613–15,124 dwell opening events that were fitted to a sum of multiple Gaussian distributions,

|

where x is current amplitude and for the nth Gaussian distribution, an is the maximum number of events and in and cn are the mean amplitude and its variance, respectively. The hP2X7 single channel conductance (γ) was calculated from the mean unitary current amplitudes by

|

in which V denotes the holding potential. Vrev was thereby taken from whole-cell experiments. Because exclusively multichannel patches were encountered during this study, we calculated, as an index of channel activity, the open probability of hP2X7 channels as NPo according to

|

by using the average current of the multichannel record (I), the single channel amplitude from the amplitude histogram, and the number (N) of active channels in the patch. We determined N based on the maximum number of channels that were simultaneously open in the presence of 0.3 mm ATP, a procedure that may, however, underestimate the actual quantity of the P2X7 receptors available in the patch.

In multichannel patches of uncertain N, knowing NPo and the number of openings (#o) during a prolonged period of observation (T; usually 4–5 min) allowed the estimation of a mean open time (τo, mean) from the following relationship (23).

|

A more profound analysis was precluded by the uncertainties in N as well as by overlapping openings in the multichannel patches.

Results are expressed throughout as means ± S.E. obtained in n cells. Differences in means were tested for significance by the Mann-Whitney U test and by the Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance on ranks followed by a modified t test (Bonferroni-Dunn) in the case of single and multiple comparisons, respectively. p < 0.05 was the accepted minimum level of significance.

IL-1β Release

Supernatants were obtained from resting and stimulated LPS-primed monocyte-derived macrophages in HBS buffer with low divalent cation concentrations. 1 ml of buffer supplemented with the indicated stimuli was added to 35-mm cell culture dishes. Upon incubation for 30 min at 37 °C, supernatants were collected and centrifuged to remove residual cells, and cleared supernatants were stored at −20 °C until assayed. IL-1β was measured using an ELISA kit (Quantikine IL-1β kit, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

RESULTS

Screening for Small Molecules That Modulate P2X7 Activity

To test for a possible modulation of hP2X7 by drugs and druglike small molecules, we decided to conduct a medium throughput screen applying a compound library comprising 1040 drugs or druglike molecules, 800 natural compounds, and 160 toxins at a final compound concentration of 20 μm. The detection of ATP-induced Ca2+ entry into stably P2X7-expressing, fluo-4-loaded HEK293 cells (HEKhP2X7) was established and scaled to the 384-well format. Contaminating P2Y receptor-triggered responses were eliminated by depleting intracellular Ca2+ stores with the sarcoendoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase inhibitor thapsigargin (200 nm for 15 min). We then monitored the long lasting increase in [Ca2+]i, which is typical for the non-inactivating, Ca2+-permeable P2X7 receptor. As a result of the primary screen and subsequent hit verification, we identified 12 compounds that potentiate the responses in HEKhP2X7 cells to stimulation with 1 mm ATP (Table 1). Two already known P2X7-potentiating compounds, the cyclopeptide antibiotics polymyxin B and colistin (also referred to as polymyxin E; Ref. 24), could be reidentified in the screening process, thereby confirming the reliability of the assay. The remaining 10 compounds group into antihistaminic drugs, neuropharmacological agents, anti-infectives, and natural products from various sources (Table 1). The majority of these compounds caused hP2X7 potentiation at concentrations that were close to their respective toxic concentrations as assessed by microscopic analysis of cellular integrity, high basal [Ca2+]i concentrations, and leakage of the intracellularly loaded Ca2+ indicator dye, the latter indicating membrane disruption. Clemastine, an H1 antihistaminic drug, however, strongly potentiated the ATP-induced increases in [Ca2+]i in HEKhP2X7 cells without eliciting a discernible toxicity. In addition, among the identified hP2X7-potentiating compounds, clemastine displayed the highest potency (see Table 1). Of note, the screening procedure also identified inhibitors of hP2X7 that are currently being characterized. Here, we focus on the mechanism and possible significance of the clemastine-induced P2X7 modulation. Because the HEKhP2X7 cell line does not display increases in [Ca2+]i upon histamine stimulation and because other H1 antihistaminic drugs that were contained in the compound collection or tested separately (e.g. diphenhydramine, doxylamine, promethazine, loratadine, and others) did not augment P2X7 responses to ATP, we conclude that HEKhP2X7 cells do not functionally express H1 receptors and that the mechanism of clemastine-induced P2X7 potentiation does not rely on histamine receptor modulation. When tested on recombinantly expressed human P2X4 or rat P2X2, clemastine did not elicit stronger [Ca2+]i signals upon stimulation with either saturating (1 mm) or half-maximally effective ATP concentrations (3 μm for P2X4 or 1 μm for P2X2; data not shown). Thus, P2X7 was the only slowly or non-inactivating member of the P2X receptor family that is modulated by clemastine.

TABLE 1.

Potentiation of human P2X7 by drugs, natural compounds, and toxins: preliminary characterization of verified P2X7-potentiating compounds

Concentration-response relationships were measured by assaying the [Ca2+]i in fluo-4-loaded stably transfected HEKhP2X7 cells incubated with various concentrations of the indicated modulators and stimulated with 1 mm ATP. ND, not detectable due to toxic effects at higher concentrations. Acute toxicity was assessed microscopically by judging the cell morphology and monitoring for a leakage of the intracellularly loaded fluorescent [Ca2+]i indicator dye. App., apparent; Neuropharm., neuropharmaceuticals; comp., compounds; rec., receptor; Isol., isolated.

| Compound | Biological activity | App. EC10 | App. EC50 | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| μm | μm | |||

| Antihistamines | ||||

| Clemastine | Antipruritic, H1 rec. antagonist | 2 | 10 | |

| Alimemazine | Antipruritic, H1 rec. antagonist | 25 | ND | Phenothiazine compound toxic at 100 μm |

| Cyclopeptides | ||||

| Polymyxin B | Cyclopeptide antibiotic | 8 | ∼25 | Known P2X7 modulator (24) |

| Colistin sulfate | Cyclopeptide antibiotic | 12 | >30 | Polymyxin E |

| Neuropharm. | ||||

| Thiotixene | Antipsychotic | 9 | >30 | Toxic at 50 μm |

| Trimipramine | Antidepressant | 30 | >100 | Weak potentiation (<20% ) |

| Anti-infectives | ||||

| Alexidine | Bisbiguanide antiseptic | 3 | ND | Toxic at 15 μm |

| Benzalkonium chloride | Surface-acting biocide | 12 | ND | Toxic at 25 μm |

| Benzethonium chloride | Surface-acting antiseptic | 12 | ND | Toxic at 100 μm |

| Natural comp. | ||||

| Garcinoic acid | Garcinia spp. lactone | 6 | ND | Isol. from Garcinia spp.; toxic at 100 μm |

| Agelasine | Antineoplastic diterpene | 12 | >30 | Isol. from Agelas dispar |

| Caperatic acid | Tuberculostatic | 25 | ND | Isol. from Parmelia spp.; toxic at 100 μm |

Analysis of Concentration Dependence of Clemastine-mediated P2X7 Potentiation

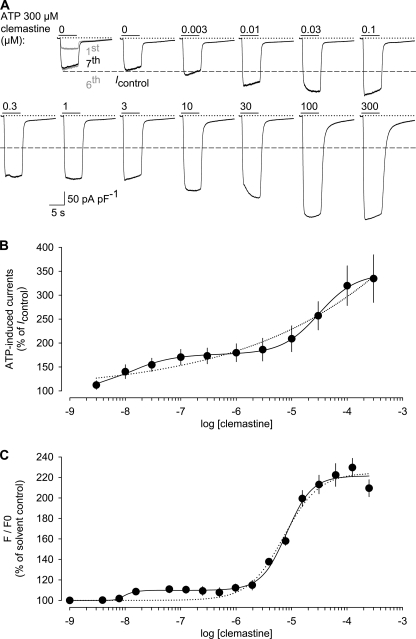

To construct concentration-response curves of clemastine-induced hP2X7 potentiation, whole cell currents in HEKhP2X7 cells were recorded during repetitive stimulation with 0.3 mm ATP and various clemastine concentrations. First, the characteristic run-up of hP2X7 was allowed to develop and reach a steady state after five to seven repeated ATP applications. Then, various clemastine concentrations were tested as co-stimulants together with a constant ATP concentration (Fig. 1A). In independent sets of experiments, we verified (i) that clemastine applied without ATP had no effect on hP2X7 currents and (ii) that the augmentation of ATP-triggered hP2X7 currents by clemastine did not require a preincubation period (see supplemental Figs. 1 and 2). The clemastine-induced potentiation of ATP-activated currents in HEKhP2X7 cells was concentration-dependent and was best described with the sum of two Hill functions, indicating the presence of high and low affinity binding sites for clemastine. A minor fraction of current potentiation developed with an apparent EC50(high) of 11 nm, and a second, more pronounced increase in current densities was observed with an apparent EC50(low) of 31 μm (Fig. 1B). This complex concentration dependence was further corroborated by measuring increases in [Ca2+]i in fluo-4-loaded HEKhP2X7 cells that were stimulated with 1 mm ATP in the absence or presence of various clemastine concentrations (Fig. 1C). Here, clemastine exerted a minor P2X7 potentiation (about 10–15% increase in F/F0 compared with ATP addition in the absence of clemastine) at nanomolar clemastine concentrations with an apparent EC50(high) of 11 nm and a major part of the potentiation exhibiting a lower potency with an EC50(low) of 8 μm (n = 19 determined in five independent experiments). As in electrophysiological experiments, clemastine given alone (up to 100 μm) failed to elicit increases in [Ca2+]i in HEKhP2X7 cells (data not shown).

FIGURE 1.

Concentration dependence of clemastine-induced hP2X7 potentiation. A, representative whole-cell recording from a HEKhP2X7 cell showing currents in response to either ATP (0.3 mm) alone or ATP co-applied together with increasing concentrations of clemastine (0.003–300 μm). ATP and clemastine were applied in low DIC and at a holding potential of −60 mV for 6 s at 2-min intervals. The recording of actual clemastine concentration-response data started after current run-up was induced by seven preapplications of ATP (superimposed responses to the first, sixth, and seventh ATP applications are shown at the left). The peak level (indicated by the dashed line) of the eighth response to ATP alone (Icontrol) served as base line for the calculation of clemastine effects. Dotted lines and bars above the current traces indicate in this and subsequent electrophysiological figures the zero current level and the times and duration of drug application, respectively. B, ratio of the additional current induced by co-applied clemastine as a percentage of Icontrol. Continuous line, best fit of the cohort data points from 13 experiments (similar to that shown in A) to the sum of two Hill equations (Equation 3). The fit minimum was constrained to 100%. Dotted line, best fit to a single Hill equation for comparison. C, ATP (1 mm)-triggered [Ca2+]i signals were assessed in fluo-4/AM-loaded HEKhP2X7 cell suspensions in HBS buffer containing 1 mm MgCl2 and 1 mm CaCl2. The fluo-4 fluorescence intensity F compared with the initial intensity F0 was determined in the absence and presence of various clemastine concentrations. After normalization to the peaks observed in the absence of clemastine, concentration-response curves were constructed in analogy to those in B. Data represent means and S.E. of 19 determinations obtained in five independent experiments.

Clemastine Increases Potency but Not Efficacy of ATP

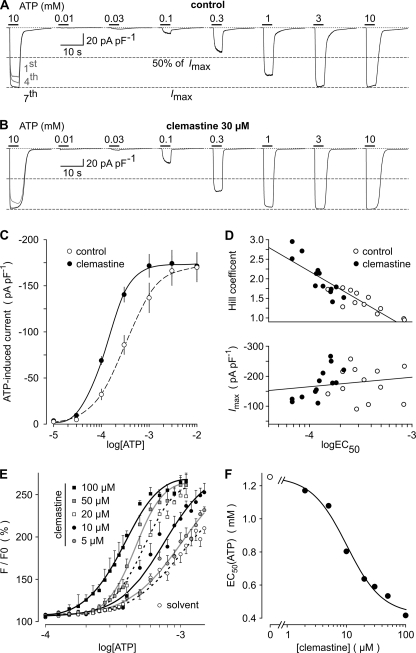

To assess a possible mutual interaction of ATP and the potentiating effects of clemastine, various ATP concentrations were tested in the absence and presence of clemastine in electrophysiological and fluorometric experiments. To this end, we constructed concentration-response relationships for ATP (0.01–10 mm) under steady-state conditions. Fig. 2, A and B, shows representative currents recordings obtained in the absence and presence of clemastine (30 μm), respectively. In the absence of clemastine, the concentration-response curve for ATP leveled off to an extrapolated maximum of −172.7 pA pF−1 at about 3 mm. It had an EC50 of ATP of 319 μm, and the Hill coefficient was 1.28. In the presence of 30 μm clemastine, the maximal current densities remained essentially unchanged (−173.7 pA pF−1), but the EC50 of ATP was significantly lower (129 μm; p < 0.05), and the concentration-dependent activation by ATP was already saturated at 1 mm ATP (Fig. 2C). The sensitization toward ATP and the higher Hill coefficient of 1.79 in the presence of clemastine indicate that clemastine may act by increasing the cooperativity of ATP binding. In support of this view, we noticed a strong correlation (r = 0.89) only when the Hill coefficients but not the maximum currents (r = 0.05) extrapolated from individual experiments by non-linear curve fitting (Hill equation) were plotted as a function of their respective EC50 (Fig. 2D).

FIGURE 2.

Impact of clemastine on ATP concentration-response relationship in HEKhP2X7 cells. A and B, representative whole-cell recordings from two cells showing currents in response to increasing concentrations of ATP obtained either in the absence (A) or presence of 30 μm clemastine (B). ATP was applied in low DIC and at a holding potential of −60 mV for 4 s at 2-min intervals. Shown are recordings of the actual concentration-response data after allowing currents to run-up during seven preapplications of a maximally effective ATP concentration (superimposed responses to the first, fourth, and seventh ATP applications are shown at the left). Dashed lines indicate the 50 and 100% levels of the maximally achievable response. C, ATP concentration-response curve in the absence (dashed line; n = 12) or presence of 30 μm clemastine (solid line; n = 13). The curves represent best fits of the cohort data points to the Hill equation (Equation 3). D, plot of Hill coefficients (upper panel) or maximum currents (lower panel) as a function of log EC50 values from individual experiments. Straight lines were obtained by linear regression fitting. Note the lack of correlation between log EC50 and Imax. E and F, fluo-4-loaded HEKhP2X7 cell suspensions were incubated with the indicated clemastine concentrations, and increases in fluorescence intensities were measured during stimulation with various ATP concentrations (n = 6 in three independent experiments). Resulting concentration-response curves for ATP were fitted to a Hill equation (E), and resulting EC50 values for ATP were drawn as a function of the clemastine concentration (F). The EC50 of clemastine (10.5 μm) to half-maximally shift the EC50 of ATP to lower concentrations was extracted from these data by applying an inverted four-parameter Hill equation. Error bars, S.E.

As shown in Fig. 2E, increasing concentrations of clemastine shifted the ATP-induced [Ca2+]i signals in HEKhP2X7 cell suspensions to lower ATP concentrations. Thus, the fluorometric [Ca2+]i assay supported the electrophysiological data. A shift of the sensitivity to lower ATP concentrations was clearly observed and significant with 5 μm clemastine. The concentration-dependent leftward shift of the ATP sensitivity ranged from an EC50(ATP) of 1.2 mm in the absence of the modulator to 0.4 mm in the presence of 100 μm clemastine (see Fig. 2F). The apparent EC50(clemastine) of the clemastine-induced ATP sensitization was 10.5 μm. Preliminary experiments applying the more potent P2X7 agonist 2′,3′-O-(4-benzoyl-benzoyl)-ATP (1) instead of ATP confirmed the leftward shift of concentration-response curves in the presence of clemastine (data not shown).

The hypothesis that clemastine increases the ATP sensitivity of hP2X7 without affecting its maximal activity was directly tested by recording current densities at saturating (10 mm) ATP concentrations and acutely applying clemastine (30 μm). Indeed, under these conditions, clemastine displayed only a minor and statistically not significant further increase in current densities (supplemental Fig. 3; n = 12). Therefore, we assume that clemastine acts as a positive allosteric modulator of human P2X7 rather than occupying the ATP-binding pocket.

Clemastine Effects on hP2X7 Are Independent of Divalent Block and Pannexin Recruitment

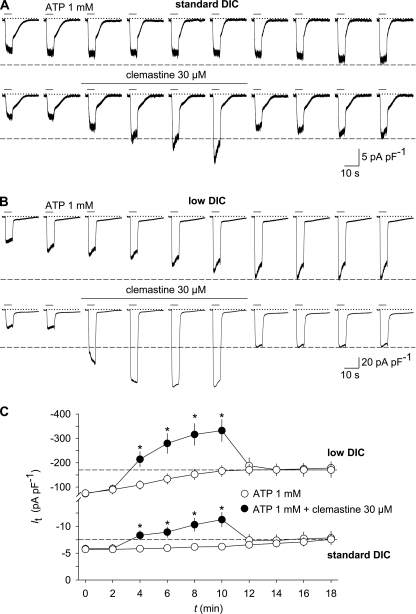

Fig. 3 shows currents in response to repeated applications of 1 mm ATP that were recorded in the presence of standard concentrations of extracellular divalent cations (2 mm Ca2+ and 1 mm Mg2+; standard DIC). In control experiments without clemastine, ATP-evoked currents continuously increased from −5.7 ± 0.65 to −7.6 ± 0.90 pA pF−1 in response to the first and tenth application, respectively (n = 15; Fig. 3, A and C). Clemastine (30 μm), however, markedly potentiated the ATP response (p < 0.5, n = 16). After 6 min of clemastine incubation, potentiation was to 209 ± 41% of the respective time-matched controls. Upon washout of clemastine, ATP-induced currents rapidly returned to the control levels, confirming the reversible mode of action. To investigate whether clemastine may interfere with functional inhibition by ambient Mg2+ and Ca2+ (25), we repeated the experiments in a low divalent cation-containing bath solution (low DIC) containing 0.1 mm Ca2+ and no added Mg2+. As expected, low DIC on its own produced a huge, ∼13-fold augmentation of the ATP response (Fig. 3, B and C). Repeated challenges with the nucleotide again induced a run-up of current amplitudes from −74.6 ± 15.1 pA pF−1 during the first challenge to −170 ± 23.5 pA pF−1 at the seventh pulse of ATP (n = 13, p < 0.05). Unless otherwise stated, all following experiments were executed in low DIC to attain steady-state ATP effects. Because potentiation of ATP-induced currents by clemastine was still observed under low DIC conditions (231 ± 35.5% of controls; n = 13, p < 0.05) and the degree of current augmentation was not significantly different from potentiation observed in standard DIC, clemastine does not act by overcoming the divalent block of P2X7.

FIGURE 3.

Effects of clemastine and extracellular DIC on P2X7 receptor-mediated membrane currents in HEKhP2X7 cells. A, representative whole-cell recordings from two cells showing the run-up (top) and the additional potentiation by clemastine (bottom) of currents in response to repetitive stimulation with ATP in standard DIC (2 mm Ca2+ and 1 mm Mg2+). B, experiments similar to those in A but performed in low DIC (0.1 mm Ca2+ and no added Mg2+). Currents were in response to 10 subsequent 4-s applications of ATP that were spaced by 2-min intervals. Clemastine was present in the superfusion medium for the 2 min before and during the third to sixth challenges with ATP. The holding potential was −60 mV. C, statistical analysis of the effects of clemastine. Shown are means of peak amplitudes (It) evoked by repetitive ATP stimulation at time t. *, p < 0.05, significant differences between time-matched controls in standard and low DIC (n = 13–16). Dashed lines designate the stage to which ATP-induced current amplitudes grew in the absence of clemastine. Note that this run-up reached steady state in low DIC upon the sixth application of ATP. Error bars, S.E.

The point of attack of clemastine may furthermore be intrinsic to P2X7 or reside at associated proteins. Possible candidates include pannexin 1 (Panx1) channels, which are present in HEK293 cells and co-immunoprecipitate with P2X7 (26). This interaction has previously been proposed to provide the P2X7-activated permeation conduit for large cationic dyes (26). Carbenoxolone (100 μm), although blocking Panx1 channels with an IC50 of 2 μm (27), did not prevent the action of clemastine (potentiation to 171 ± 13% of controls; n = 14 each, p > 0.05; supplemental Fig. 4, A and B). Although Panx1 was not the site of action of clemastine, an unanticipated observation should be mentioned: carbenoxolone potentiated by itself ATP-induced P2X7 currents. In medium containing low DIC, the initial current amplitudes obtained in carbenoxolone-pretreated HEKhP2X7 cells were about 1.5-fold higher compared with corresponding experiments without carbenoxolone treatment (n = 14 each, p < 0.05). Considering these data together with the rapid reversibility of clemastine effects, we have not obtained evidence that clemastine-dependent augmentation of hP2X7 currents involves recruitment and/or opening of pannexin-like hemichannels.

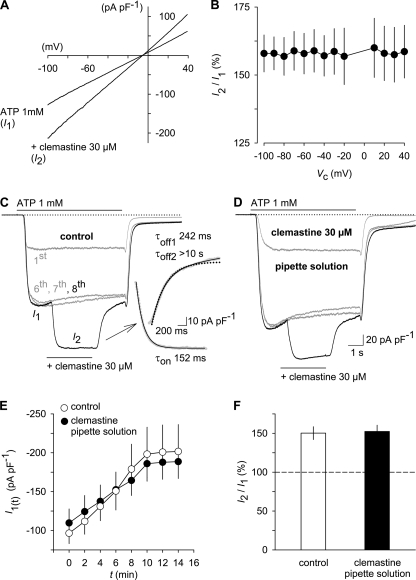

Potentiating Effect of Clemastine on hP2X7 Is Voltage-independent, Fast, and Mediated by Binding to Extracellularly Exposed Site

Next, we tested for voltage dependence of the effects of clemastine as would be expected if the site of action of the cationic ethanolamine derivative (28) were within the electric field of the cell membrane, i.e. somewhere along the pore. However, the clemastine potentiation occurred at all membrane potentials tested (−100 mV to +40 mV) and lacked any overt sign of voltage dependence (Fig. 4, A and B). The antihistaminic did not cause shifts in the reversal potential of P2X7 (see Fig. 4A). Respective values were −0.6 ± 3.29 and −0.7 ± 3.07 mV in the absence and presence of the compound, respectively (n = 14, p > 0.05) and hence in both cases close to the equilibrium potential (0 mV) commonly assumed for non-selective cation channels under the chosen buffer conditions.

FIGURE 4.

Properties of clemastine-potentiated hP2X7 channel currents. A, representative leak-subtracted current-voltage relationship for the ATP-induced current in the absence (I1) and presence of clemastine (I2). Currents were in response to two voltage ramps (1 s in duration) from −100 mV to +40 mV imposed after 4 s in ATP alone and after another 4 s in the additional presence of clemastine. Leak subtraction was done by subtracting the ensemble current from four voltage ramps recorded prior to ATP application. B, averaged data from experiments like that shown in A (n = 14). The ratio of the clemastine-potentiated current (I2) to that of the current evoked by ATP alone (I1) is expressed as a percentage of I1 and plotted versus the ramp command potential (Vc), revealing the lack of voltage dependence of the clemastine effect. C, time course of the potentiation by clemastine. ATP was applied repetitively to allow channel run-up to occur. Superimposed responses to the first, sixth, and seventh ATP applications are shown in gray . Clemastine (for 3 s) was then acutely added 2 s after the onset of the eighth stimulation with ATP (black). Insets show the rising (bottom) and decaying phase (top) of the clemastine-induced extra current. Continuous lines represent monoexponential (bottom; Equation 1) and biexponential (top; Equation 2) functions fitted to the data to extract time constants for the onset (τon) and offset (τoff) of the clemastine-potentiated current. Monoexponential curve fitting to the decaying current phase (top; dotted line) gave worse results. D, experiments similar to those in C but performed in cells internally perfused with a clemastine-containing pipette solution. E and F, lack of effect of intracellular clemastine on P2X7-mediated currents as assessed from experiments similar to those in C and D. E, peak amplitudes in response to the repetitive application of ATP alone (labeled I1 in C) at time t recorded under control conditions and with internal clemastine. F, ratio of the additional current induced by extracellular clemastine (labeled I2 in C) as a percentage of I1 from control cells and cells dialyzed with clemastine (n = 12 each). All experiments were performed in low DIC and at a holding potential of −60 mV. Error bars, S.E.

To gather more information about the mode of action of clemastine, we analyzed the time scale of hP2X7 current potentiation. To this end, the compound was acutely added when the channels were already opened by non-saturating ATP concentrations and had reached a steady state by repeated exposure to the nucleotide (Fig. 4C). The onset of the extra current in the presence of clemastine was fast and followed a monoexponential time course with a time constant (τon) of 155 ± 15 ms. This time constant was similar to the τon of the current evoked by ATP alone (134 ± 17 ms; n = 12, p > 0.05) and is apparently limited by the exchange times of the application system (see “Experimental Procedures”). Thus, the true on-kinetic of clemastine is expected to be faster than 100 ms. The decay of the clemastine-dependent current augmentation upon washout of clemastine in the continued presence of ATP was better approximated by a biexponential function (see Fig. 4C, inset). The fast component had a time constant (τoff1) of 240 ± 33 ms and contributed by 81.2 ± 3.5% to the total amplitude. No reliable values for the slower decay phase of the current could be extracted from the present experiments because τoff2 was extrapolated to >5 s and was thus beyond the recorded washout period of clemastine (2 s). The offset time constants for ATP alone were extracted from currents during the sixth challenge with ATP. The τoff1 of ATP (203.7 ± 37.8 ms, 85.7 ± 2.8% amplitude contribution) was not significantly different from the τoff1 for the clemastine effect. The slow τoff2 for ATP was 10.5 ± 2.6 s. Overall, it was apparent that the deactivation of ATP-induced currents was considerably slower than their activation (p < 0.05) irrespective of the presence or absence of clemastine. We did not investigate for possible reasons, but ongoing P2X7 pore dilation, supposed to be only gradually reversible upon agonist removal, has been suggested to constitute a cause for that (8).

The immediacy of the clemastine potentiation suggested an action from outside the cell. However, the lipophilicity of clemastine (log p = 5.57; Ref. 29) results in penetration of the blood-brain barrier, then causing sedative side effects of the drug (30). Thus, an intracellular binding site could not be excluded a priori. When directly dialyzed to the cell interior via the patch pipette, the intracellularly applied clemastine failed to increase the current densities observed upon ATP stimulation (Fig. 4, D and E) and did not prevent the potentiation evoked by additional application of clemastine from the extracellular side (Fig. 4, D and F; n = 12). We conclude that clemastine modulates hP2X7 activity by binding to the extracellular side of the transmembrane channel. Given that the clemastine potentiation developed with a velocity similar to that of the activation of the ATP-induced current itself, an involvement of intracellular signaling cascades in the transmission of this effect is rather unlikely, and we assume the existence of an allosteric binding site on the ectodomain of hP2X7.

Clemastine Potentiates and Accelerates Pore Dilation of Recombinant hP2X7

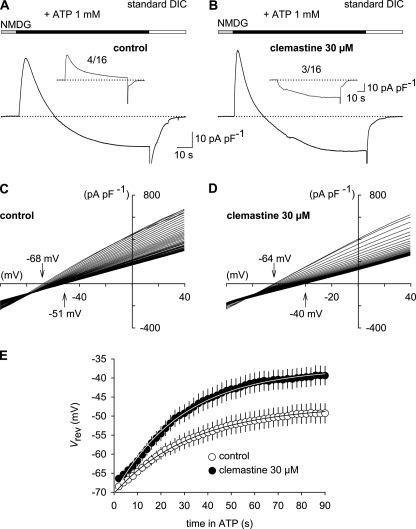

Like P2X2 and P2X4, P2X7 undergoes a time- and activity-dependent change in its permeation path, a process often referred to as pore dilation or I2 state that is accompanied by an increased permeability to large organic cations such as NMDG+ and Yo-Pro-1 (31). To investigate whether clemastine interferes with this behavior, we recorded ATP (1 mm)-induced currents with NMDG+ and Na+ as the only charge carriers in the extra- and intracellular solutions, respectively. In agreement with previous data from rat P2X7 (10, 32), the immediate current through the activated hP2X7 was outward at a holding potential of −60 mV, indicating a low NMDG+ permeability. During the prolonged application of ATP (90 s), currents in HEKhP2X7 cells gradually declined and eventually became inward currents in 12 of the 16 cells tested (Fig. 5A). In clemastine (30 μm), the sequence of events was similar in most cells investigated (Fig. 5B). In three of 16 cells, however, inward currents carried by NMDG+ were discernible right from the start of ATP application (Fig. 5B, inset). Consistently, the mean NMDG+ inward current density was higher in the presence of clemastine (−34.8 ± 3.9 pA pF−1; n = 13) compared with the experiments without clemastine (−19.8 ± 5.3 pA pF−1; n = 12, p < 0.05).

FIGURE 5.

Clemastine enhances NMDG+ permeability of hP2X7. A, representative whole-cell recording during a 90-s application of ATP in bi-ionic conditions (extracellular NMDG+ and intracellular Na+). At a holding potential of −60 mV, the ATP-induced current is initially outward (Na+ efflux) and then gradually becomes inward as NMDG+ permeability increases. Note that four of 16 cells showed a slowly decaying outward current only (inset). B, experiments similar to those as in A but performed in the presence of clemastine. In three of 16 cells, the current was inward right from the start of ATP application. C and D, the time course of reversal potentials (Vrev) of hP2X7 currents in the continuous presence of ATP without (C) and with addition of 30 μm clemastine (D). Experiments were performed as in A and B but repetitively applying voltage ramps (−100 mV to +40 mV; 1 s in duration) at 2-s intervals. Resulting ramp currents were leak-corrected by subtracting the ensemble current from four voltage ramps recorded prior to ATP application and superimposed. Vrev shifted from −68 and −64 mV to steady-state values of −51 and −40 mV (arrows) in the absence and presence of clemastine, respectively. E, plot of Vrev versus time in ATP for experiments similar to those shown in C and D. Data points are fitted to a single exponential (Equation 1; superimposed lines), the time constant of which decreased in clemastine (n = 11 and 13). Error bars, S.E.

To calculate time-dependent changes of the permeability ratio PNMDG/PNa, voltage ramp experiments were performed. During the first ATP application in the absence of clemastine, the reversal potential (Vrev) was −68.5 ± 0.6 mV, corresponding to a permeability ratio of 0.065 ± 0.001 (n = 13; Fig. 5, C and E). In the continued presence of ATP, Vrev became less negative with a time constant of 42.6 ± 4.6 s and with steady-state values for Vrev and PNMDG/PNa of −49.3 ± 2.6 mV and 0.146 ± 0.015, respectively. In the presence of clemastine, the reversal potential shifted more rapidly (25.9 ± 1.9 s; n = 11) and more extensively (from −66.4 ± 0.9 to −39.4 ± 2.5 mV), resulting in higher values for initial and final PNMDG/PNa of 0.071 ± 0.002 and 0.214 ± 0.025, respectively (Fig. 5, D and E). Thus, clemastine significantly accelerates and increases the fractional NMDG+ permeability upon long lasting stimulation with ATP.

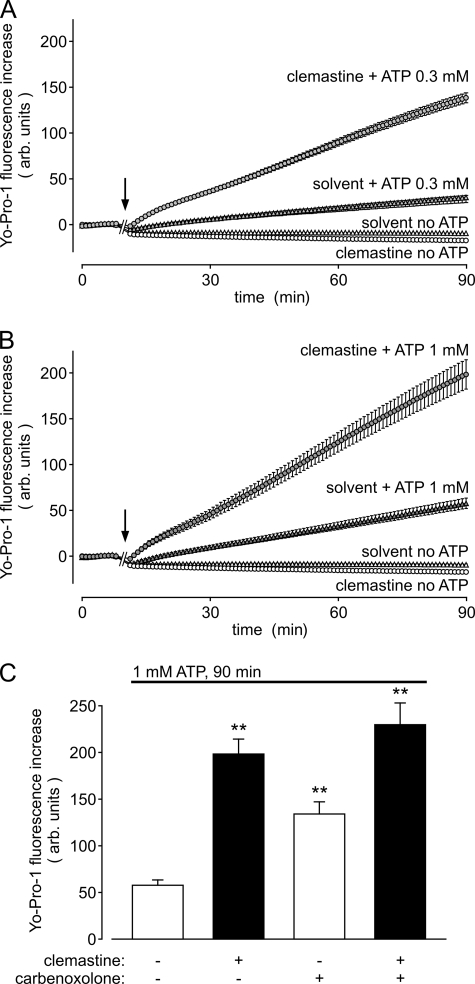

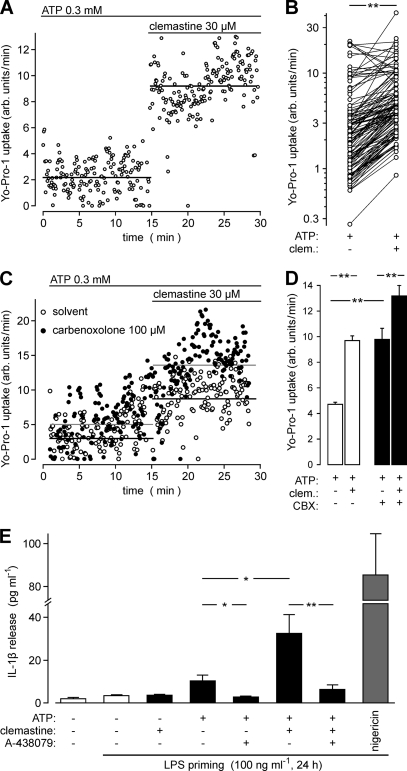

The permeation of large cationic dyes such as ethidium or Yo-Pro-1 is another hallmark of P2X7 pores (10). We therefore tested the clemastine effects on the ATP-induced Yo-Pro-1 uptake in HEKhP2X7 cells. As shown in Fig. 6, clemastine accelerated the Yo-Pro-1 uptake rates in the presence of 0.3 or 1 mm ATP without exerting an effect in the absence of ATP. The potentiation of Yo-Pro-1 uptake by 30 μm clemastine was about 4-fold in the presence of 1 mm ATP (Fig. 6C). In carbenoxolone-pretreated and ATP-stimulated HEKhP2X7 cells, the clemastine-dependent acceleration of Yo-Pro-1 was essentially unchanged, again excluding a role of pannexins in the mechanism of clemastine. Intriguingly, but consistent with the electrophysiological data, carbenoxolone by itself induced a potentiation of Yo-Pro-1 accumulation (see Fig. 6C). This, together with the recently reported block by ATP itself of Panx1 (27), obviously excludes Panx1 channels or hemichannels being the P2X7-recruited permeation pathway for the uptake of Yo-Pro-1 at least in the recombinant HEK cell system.

FIGURE 6.

Clemastine accelerates P2X7 receptor-mediated Yo-Pro-1 accumulation. A and B, time course of Yo-Pro-1 (1 μm) uptake in HEKhP2X7 cells in the presence of ATP and clemastine (30 μm). Solvent (“no ATP”) or ATP, applied at a final concentration of 0.3 (A) or 1 mm (B), was added to HEKhP2X7 cell suspensions as indicated by the arrows. C, statistical analysis of the clemastine (30 μm) effects on Yo-Pro-1 (1 μm) uptake determined as shown in B. Shown is the fluorescence increase after 90 min of ATP (1 mm) stimulation. The action of the connexin and pannexin blocker carbenoxolone (100 μm; preincubated for 30 min) and the combination of carbenoxolone and clemastine on P2X7-mediated Yo-Pro-1 uptake was also examined. **, significant (p < 0.01) difference to ATP effects observed in the absence of clemastine and carbenoxolone. Error bars, S.E.

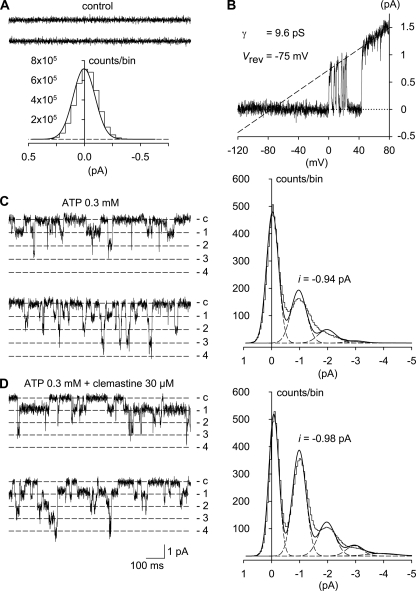

Effects of Clemastine on P2X7 Single Channel Properties

To resolve, on the single channel level, the mechanisms by which clemastine allosterically increases the potency of ATP, we tried initially to detect P2X7 receptor-mediated unitary currents in outside-out patches prepared from HEKhP2X7 cells. However, ATP (0.3 mm) evoked, at a holding potential of −120 mV, in all these trials (n = 5) large current fluctuations, resulting in macroscopic current amplitudes of −37.6 ± 5.0 pA. From our single channel data (see below), we estimated that about 30 hP2X7 channels were simultaneously active in the excised outside-out vesicles, obscuring the resolution of unitary events. Nevertheless, clemastine (30 μm) potentiated the ATP-evoked currents by 1.70 ± 0.24-fold to −58.8 ± 4.4 pA even under these experimental conditions. We then hypothesized that minimizing the membrane area under the patch pipette membrane would reduce the number of P2X7 channels available for activation by ATP. To this end, we proceeded with inside-out recordings, which also allowed tight control of the applied transmembrane potential.

Without ATP in the pipette solution and at a holding potential of −120 mV, no channel activity could be observed in four control patches during a 5-min recording period (Fig. 7A). Merely one of these showed, in response to voltage ramps, outwardly directed channel openings at potentials positive to −40 mV (Fig. 7B). Judged from their negative reversal potential (−76 ± 2 mV) and their slope conductance (10.1 ± 0.7 pS; averaged from 10 consecutive ramp currents), the underlying channels presumably belong to the delayed rectifier K+ channel class (33) from which several subunits are endogenously expressed in HEK293 cells (34). We next tested the effects of ATP (0.3 mm) alone. Fig. 7C shows typical multiple channel currents activated by the nucleotide. Estimated from the number of open levels observed during the entire recording, we think that the patch contained at least N = 4 hP2X7 channels. For the whole of six similar experiments, N ranged between three and seven channels per patch. We then assessed the single channel amplitude by fitting five Gaussian distributions to the all-point amplitude histogram (Fig. 7C), which represented the closed, first, second, third, and fourth open level. The mean unitary current obtained in this way was −0.94 pA for this particular patch and −1.10 ± 0.08 pA on average, corresponding to an hP2X7 single channel conductance (γ) of 9.25 ± 0.68 pS. The channel activity index (NPo) and channel mean open time (τo, mean) were 0.133 ± 0.024 and 3.96 ± 0.65 ms, respectively (n = 6). Fig. 7D illustrates a typical recording and the corresponding amplitude histogram from a four-hP2X7 channel inside-out patch exposed to the combination of ATP plus 30 μm clemastine. The modulator did not influence N, which was between three and six channels per patch. As already apparent from the figure, clemastine lacked any effect on the single channel amplitude (−1.17 ± 0.10 pA) and hence on γ (9.80 ± 0.83 pS). The current traces in Fig. 7D suggested, however, that the channel open time might have been increased in the presence of clemastine. Indeed, clemastine prolonged τo, mean to 19.14 ± 5.54 ms (p < 0.05) and increased channel activity by 2.2 ± 0.7-fold, resulting in an NPo of 0.240 ± 0.055 (n = 6). Thus, clemastine modulates the P2X7 gating by stabilizing the open conformation without affecting the single channel conductance.

FIGURE 7.

Effects of clemastine on P2X7 receptor-mediated single channel currents in HEKhP2X7 cells. A, representative current traces (upper panel) and all-point amplitude histogram (lower panel) from an inside-out patch recorded in the absence of ATP, revealing a lack of channel activity at the holding potential of −120 mV. B, membrane response, after correction for linear leak, to a 1-s voltage ramp from −120 to 80 mV from the same patch as in A. Outward currents are shown as upward deflections. Note that the voltage-dependent channels opened only in response to strong membrane depolarization. The linear curve fitted to the channel amplitudes (broken line) revealed a slope conductance of 9.6 pS and a reversal potential of −75 mV. C, inside-out patch currents (left) recorded at −120 mV with 0.3 mm ATP in the patch pipette. There are at least four channels active in the patch. Inward currents are shown as downward deflections. The closed (c) and four open levels are indicated. The amplitude distribution (right panel) derived from this patch was fit with the sum of five Gaussian distributions (lines). Mean hP2X7 single channel amplitude was 0.94 pA. D, inside-out patch currents (left) and amplitude histogram (right) from another four-channel patch recorded under similar conditions but with 0.3 mm ATP plus 30 μm clemastine in the patch pipette. Note the longer openings in the presence of clemastine. The mean single channel amplitude at −120 mV was −0.98 pA. The current traces in A, C, and D represent 2 s of consecutive recording, although the corresponding histograms (bin width, 0.05 pA) were constructed from continuous 5-min sampling periods in each case.

The single channel data provide no insight into possible mechanism by which clemastine supports P2X7 pore dilation (see Figs. 5 and 6). Based on kinetic modeling of whole-cell data, it has been suggested that the occupancy of all three binding pockets of P2X7 may sensitize the receptor toward a dilated, highly conductive state (35). By contrast but in agreement with previous data derived from outside-out patches (20), we could not substantiate such high conductance channel openings. In addition, cell-attached patch recordings (supplemental Fig. 5) did not reveal large (∼400-pS) and long lived channel events that are also referred to as Z pores (21).

Characterization of Clemastine Effects on Natively Expressed P2X7 Macrophages

To investigate whether clemastine also acts on endogenously expressed human P2X7 receptors, we isolated and differentiated LPS-primed human monocyte-derived macrophages, which express P2X7 together with P2X4 and P2Y receptors. Consistent with earlier reports (36), maturated hMDM responded to strong depolarization pulses with oscillating outward currents characteristic of large conductance K+ channels (supplemental Fig. 6, A and B). At a holding potential of −60 mV, stimulation with ATP (1 mm) evoked a two-component current response. The first large and rapidly decaying component disappeared upon repeated application of ATP. The second, sustained component showed a significant run-up from −3.5 ± 0.7 to −6.7 ± 0.9 pA pF−1 in response to a repeated challenge with ATP (n = 9; supplemental Fig. 6C), suggesting the involvement of P2X7 in the ATP response. Clemastine potentiated the non-inactivating currents induced by 1 mm ATP by about 2-fold (n = 10; Fig. 8, A and B). As expected, the effect of clemastine was abrogated in the presence of the P2X7 blocker A-438079 (37), although the inhibition of ATP-induced currents was only partial (35.4 ± 7.9%). Upon washout of A-438079, both the partial inhibition of the ATP-induced current and its strong potentiation by clemastine were fully restored (see Fig. 8, A and B). The A-438079-insensitive current in hMDM presumably reflects a contribution of P2X4 (38). The assumption that clemastine does not potentiate the P2X4-like current in hMDM was fostered by the observation that the ATP (3 μm)-induced Ca2+ influx into HEK cells transfected with an expression plasmid encoding the human P2X4 receptor was not influenced by clemastine (data not shown).

FIGURE 8.

Potentiation of native P2X7 currents by clemastine in hMDM. A, whole-cell recording showing the acute effect of clemastine on ATP-induced currents before, during, and after washout of the selective P2X7 receptor antagonist A-438079 (10 μm). ATP was repetitively applied at 2-min intervals, three times for 7 s, in low DIC and at a holding potential of −60 mV. Clemastine was added for 3 s, beginning 2 s after the onset of the stimulation with ATP. A-438079 was present in the superfusion medium for the 2 min before and during the second cycle with ATP/clemastine. Two preceding applications of ATP, used to desensitize transient ATP-induced currents, are omitted (compare supplemental Fig. 6). B, summary of the effects of clemastine and A-438079 on the current amplitudes induced by ATP alone (labeled as I1 in A) as well as potentiation of the ATP-induced currents by clemastine in the absence, in the presence, and after washout of A-438079 (labeled as I2 in A). *, p < 0.05, significant differences between I1 and I2; **, p < 0.05, significant differences from I1 and I2 obtained before application of A-438079 (control; n = 10). Error bars, S.E.

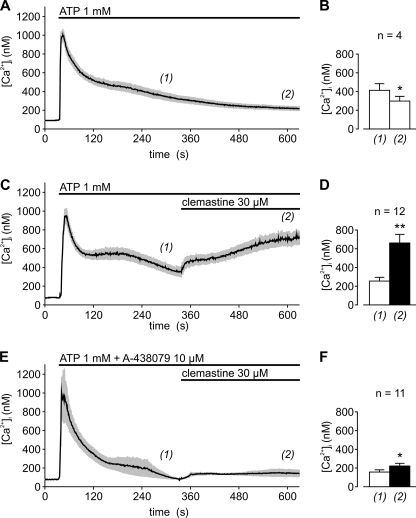

In single cell [Ca2+]i imaging experiments on LPS-primed hMDM, stimulation with 1 mm ATP induced a transient increase in [Ca2+]i followed by a slowly decaying plateau phase (Fig. 9, A and B). Because a P2X7-mediated sustained Ca2+ influx was expected to be a component of the plateau phase, clemastine (30 μm) was added 5 min after stimulation with ATP. As shown in Fig. 9, C and D, clemastine induced a highly significant (p < 0.01) second increase in [Ca2+]i in hMDM that was almost completely suppressed when cells were preincubated with the P2X7-specific blocker A-438079 (Fig. 9, E and F). Similar results were obtained in murine bone marrow-derived and LPS-primed macrophages (supplemental Fig. 7) and in acutely dissociated murine splenocytes (data not shown) in which P2X7-mediated Ca2+ signaling has been reported (17). From these data, we conclude that clemastine potentiates endogenously expressed human and murine P2X7 receptors in LPS-primed macrophages and presumably also in splenic T cells.

FIGURE 9.

Potentiation of ATP-triggered, sustained [Ca2+]i signals in LPS-primed hMDM by clemastine. A, C, and E show representative tracings of the intracellular Ca2+ concentration during stimulation with 1 mm ATP. Depicted are means (black line) and S.E. (gray shading) of 30–50 LPS-primed hMDM measured per experiment. B, D, and F, statistical analysis of mean intracellular Ca2+ concentrations 5 (1) and 10 min (2) after stimulation with ATP with or without subsequent addition of 30 μm clemastine. Data represent means and S.E. of the indicated number of independent experiments. Experiments shown in E and F were performed in the presence of the specific P2X7 blocker A-438079 (10 μm; preincubated for 10 min). Significant (*, p < 0.05) and highly significant (**, p < 0.01) changes between the 5- and 10-min values are indicated.

As shown for the recombinantly expressed hP2X7, clemastine also accelerated the ATP-triggered cellular uptake of Yo-Pro-1 in hMDM by 2.29 ± 0.09-fold (n = 121 cells in five independent experiments from different donors, p < 0.01 with paired two-sample t test; Fig. 10, A and B), indicating potentiation of the permeability of large organic cations and facilitation of pore formation by clemastine. In an independent set of experiments, we again verified that carbenoxolone by itself augmented the ATP-triggered Yo-Pro-1 uptake in hMDM and failed to block its augmentation by clemastine (Fig. 10, C and D). Because the long lasting activity of P2X7 has been shown to trigger release of the proinflammatory cytokine IL-1β in LPS-primed hMDM, we tested the effect of clemastine on IL-1β secretion from hMDM. As reported earlier (39), LPS treatment by itself was not sufficient to trigger a strong IL-1β release (Fig. 10E). When additionally challenged with ATP (0.3 mm), IL-1β release was triggered in an A-438079-sensitive fashion. Clemastine given alone had no effect on IL-1β secretion (Fig. 10E). Upon co-stimulation with ATP and clemastine, however, the IL-1β release increased by 1.9-fold (p < 0.05) compared with the ATP stimulation alone. Again, A-438079 strongly inhibited this response (p < 0.01; see Fig. 10E). Thus, clemastine increases the ATP-triggered IL-1β release from hMDM presumably by augmenting the signaling of natively expressed P2X7 receptors.

FIGURE 10.

Clemastine accelerates ATP-induced Yo-Pro-1 uptake and augments the IL-1β release in human monocyte-derived macrophages. A, representative track of the fluorescence increase (arbitrary (arb.) units per minute) in a single cell in response to ATP (0.3 mm) stimulation followed by addition of clemastine (30 μm). The averaged Yo-Pro-1 fluorescence accumulation rate is indicated by the black lines. B, Yo-Pro-1 uptake in multiple single cells analyzed as shown in A. Fluorescence increases were determined in the same cells in the presence of ATP (open circles; 12.5-min time interval) and upon addition of clemastine (clem.; filled circles). Shown are data from single human LPS-primed monocyte-derived macrophages measured in five independent experiments. 21–25 cells were analyzed in each experiment. C depicts data from experiments performed as in A but either without (open symbols) or after preincubation with 100 μm carbenoxolone for 30 min (CBX; filled symbols). D, aggregated data of all experiments (150 cells in five to six independent experiments each) after evaluation as shown in B. Differences in the Yo-Pro-1 uptake were significant (p < 0.01) as tested with a Wilcoxon paired (prior versus post-clemastine addition) or unpaired (with and without carbenoxolone) rank test. E, IL-1β released into the medium from unprimed or LPS-primed (100 ng ml−1 for 24 h) hMDM was determined in cleared supernatants by ELISA. hMDM were incubated with A-438079 (10 μm) for 30 min before addition of ATP (0.3 mm) in the absence or presence of clemastine (30 μm) as indicated. The H+/K+ ionophore nigericin (20 μg/ml) was used to determine a maximal IL-1β release. Depicted are means and S.E. of four to six (unprimed control and clemastine alone) or 10–13 independent experiments (other conditions).

DISCUSSION

Here we present evidence for an as yet unrecognized positive allosteric modulation of P2X7 by clemastine. From the experimental data, we conclude that clemastine binds to a still undefined site on the ectodomain of human P2X7 and thereby facilitates the binding of ATP to the ligand-gated cation channel. Both the binding affinity and the apparent cooperativity of ATP binding increased in the presence of clemastine. In the absence of ATP, even the highest clemastine concentrations tested did not elicit a discernible P2X7 activation, and at saturating ATP concentrations, clemastine induced no further current increase. These data argue for an allosteric sensitization of the receptor by clemastine. In addition, the formation, recruitment, and dilation of the P2X7 pore were accelerated and augmented in the presence of clemastine as demonstrated by the increase in the fractional NMDG+ permeability and the acceleration of cellular uptake of the large cationic dye molecule Yo-Pro-1. The marked potentiation of human P2X7 activity in the presence of non-saturating ATP concentrations was also evident with the endogenously expressed receptor in human macrophages. Increases in [Ca2+]i signaling, current potentiation, and acceleration of Yo-Pro-1 influx confirmed the potentiating effect of clemastine on native P2X7 receptors. Consequently, the P2X7-controlled secretion of the proinflammatory cytokine IL-1β from LPS-primed and ATP-stimulated human macrophages was further increased by clemastine, and the essential role of P2X7 in this event was confirmed by applying the selective P2X7 blocker A-438079 (37).

Because intracellularly applied clemastine was ineffective, a binding site on the intracellularly exposed domain or on a P2X7-interacting protein was ruled out. Likewise, the remaining effect of clemastine in inside-out patches excludes the involvement of a soluble intracellular second messenger in its mode of action. Yet, processes to trigger the pore dilation or to form or recruit a pore that allows dyes to permeate through the cell membrane seem to be positively influenced by clemastine. Of them, recruitment of pannexin hemichannels (26) was unlikely to control the P2X7-triggered Yo-Pro-1 uptake as inferred from the failure of carbenoxolone to block the effect in HEKhP2X7 cells. The reported geldanamycin-dependent dephosphorylation of P2X7-bound HSP90 (40) can also hardly explain the very rapid onset and reversibility of clemastine-mediated current augmentation. Only recently, nonmuscle myosin has been identified as an intracellular interaction partner of P2X7 in HEK293 cells and in monocytes that stabilizes the P2X7 pore and prevents its dilation. Interestingly, after stimulation with ATP, nonmuscle myosin dissociates from the channel, then allowing the pore to dilate (41). Accessibility studies within the permeation pathway of P2X2 have demonstrated that pore opening may be due to an intrinsic property of the channel to undergo dramatic restructuring of the transmembrane helix bundle (42). According to this model, the channel gate itself expands and allows changes of the ion selectivity if continually activated with ATP. Because clemastine sensitized the ATP binding to hP2X7, these mechanisms possibly serve as an explanation for the accelerated pore dilation and dye permeability in clemastine-treated HEKhP2X7 cells and monocyte-derived macrophages.

Other potential mechanisms of P2X7-associated pore formation have been proposed from cell-attached recordings in macrophages. Here, ATP evoked activation of so-called Z pores, which show a conductance of ∼400 pS and long lived openings of ∼2 s (21). Although Z pores are reportedly absent in HEK293 cells and require temperatures >30 °C (43), the clemastine-mediated increase in dye uptake and NMDG+ permeability might rely on a similar, second messenger-operated pore. We therefore repeated these experiments in HEKhP2X7 cells although at room temperature. Our data confirm the lack of Z pores in ATP-treated HEK293 cells irrespective of the absence or presence of clemastine. These cells can, however, in response to ATP express all the hallmarks commonly associated with P2X7 pore dilation, including permeability increases toward large cations and cationic dyes, membrane blebbing, and eventually cell lysis (e.g. Ref. 10 and this study). Hence, the mechanisms of P2X7 pore dilation as well as the impact of clemastine thereon remain enigmatic.

The single channel data corroborated those from whole-cell recordings where clemastine increased the potency of ATP (reflected by the effect on NPo and the related τo, mean) without changing its efficacy (lack of effect on γ). Interestingly, two different gating modes, associated with either short or long openings, have already been described for hP2X7 (20). Moreover, the occupancy by ATP of one or two of its three binding sites may introduce some degree of conformational asymmetry within the P2X7 trimer, leading to negative cooperativity for further agonist binding (35). Our data support a model that clemastine binding may overcome the conformational hindrances under conditions of partial agonist occupancy and thereby promotes the long opening gating mode.

Directly acting P2X7 modulators include a growing number of competitive or non-competitive receptor antagonists or blockers, some of which exhibiting a remarkable isotype specificity toward P2X7 (for a review, see Ref. 1). The group of activators and positive modulators is considerably smaller but includes endogenously available mechanisms. Extracellularly applied NAD, for example, ADP-ribosylates P2X7 at Arg-125, leading to a covalently linked agonist, which presumably pokes into the ATP-binding pocket (44, 45). This irreversible and orthosteric mechanism clearly differs from that of clemastine, which acts reversibly and cooperatively with ATP. Likewise, clemastine does not act by overcoming the divalent block of P2X7, which is thought to be mediated by specific metal binding sites in the extracellular loop of P2X7 (46) and introduces a negative allosteric modulation of agonist binding (25) and/or prevents the gating of the channel pore (47).

Other P2X7-potentiating ligands include lipids and lipophilic compounds such as arachidonic acid (48), lysophosphatidylcholine, sphingosyl- and hexadecyl-phosphorylcholine conjugates (49), and possibly the lipopeptide antibiotic polymyxin B, which requires the lipid moiety for its effect on P2X7 (24). Direct binding of these lipophilic modulators to the channel protein appears possible but has not been demonstrated. Interestingly, these modulators act by shifting the agonist sensitivity to lower concentrations. Thus, they share a similar mode of action with clemastine. Future studies will, therefore, address the question whether clemastine actions overlap or cooperate with those of the lipophilic P2X7 modulators and possibly shift the ATP sensitivity to low micromolar concentrations, which are typically expected to be reached in physiological signaling processes. Alternatively, if clemastine shares a common binding site with the other modulators, synergism would not be expected. In this context, the possible existence of two binding sites for clemastine, one with a nanomolar affinity and the other with a micromolar affinity, as inferred from the functional data, hints to the existence of more than one modulatory site on the channel protein. Therefore, it will be an upcoming task to identify the binding pockets on the surface of the P2X7 protein, an attempt that is further fueled by the solved structure of the extracellular and transmembrane domains of zebrafish P2X4 (50) by providing a reliable structural template for modeling and docking analyses.

P2X7 activation cooperates with LPS and toll-like receptor agonists to trigger IL-1β processing and release in a number of immune cells, including monocytes (5), hMDM (11), and microglia (12). This proinflammatory action of P2X7 appears to contribute to many pathological processes. Neuropathic pain, inflammatory hyperalgesia, and immune cell infiltration in the CNS represent only a selection of pathologies that have been linked to P2X7 activity (51). Therefore, it was deemed worthwhile to assess the relevance of P2X7 potentiation by clemastine with respect to the cytokine release. The approximately 1.9-fold increase in IL-1β secretion in the presence of submaximally activating ATP concentrations was sufficient to release about half of the maximally releasable pool in the presence of the K+ ionophore nigericin. Of course, the clemastine concentration of 30 μm applied in these experiments is far beyond the plasma concentrations upon systemic application of the antihistaminic drug and may bear relevance only for topically applied clemastine. However, the sensitization already started at much lower concentrations as inferred from the shift of the EC50 of ATP in the [Ca2+]i assay. Possibly, clemastine is already effective in the nanomolar range in which inward currents were potentiated about 1.5-fold, whereas [Ca2+]i levels displayed a discernible but only minor potentiation of P2X7. The reason for this discrepancy presumably reflects non-linearity of channel currents and resulting changes in the steady-state [Ca2+]i, which is kept low by potent buffering and extrusion mechanisms to prevent cellular damage. One should also consider that plasma concentrations of clemastine do not necessarily reflect the concentration of the drug in a susceptible tissue. Because clinical data do not hint to severe or obvious clemastine-induced adverse drug responses that may involve P2X7 potentiation, augmentation of P2X7 activity in the presence of therapeutic concentrations of the antihistamine possibly exert more subtle changes that require a more thorough and focused evaluation. In addition, although we demonstrated release of the proinflammatory cytokine IL-1β from hMDM, P2X7 activation also gives rise to production and secretion of IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra), which is in turn expected to exert anti-inflammatory activity (52–54). Hence, the pro- or anti-inflammatory net effect of a clemastine-induced P2X7 potentiation may additionally depend on the targeted cell type, local availability of ATP, and pathophysiological background. An accumulating body of evidence points to a beneficial role of P2X7 activation in monocytes and macrophages to contribute to elimination of intracellularly located parasites and mycobacteria (55, 56). Even more strikingly, P2X7 activation in dendritic cells chiefly contributes to the orchestration of the adaptive antitumor immunity by triggering the caspase-1-dependent inflammasome activation in dendritic cells followed by IL-1β secretion and priming of interferon γ-producing CD8+ T cells (57). Therefore, selective P2X7 activators or positive allosteric modulators are intensely sought. In addition, the use of P2X7 activators, by triggering apoptotic cell death, has been put forward as a concept to treat several malignancies (Ref. 58 and references therein). Thus, the approved drug clemastine may serve as an interesting and immediately available starting point to explore these mechanisms in clinical settings.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported by funding from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft within the framework of the Forschergruppe 748.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1–7.

- NMDG

- N-methyl-d-glucamine

- hP2X7

- human P2X7

- hMDM

- human monocyte-derived macrophages

- HBS

- HEPES-buffered saline

- DIC

- divalent cations

- pF

- picofarads

- pS

- picosiemens

- Panx1

- pannexin 1.

REFERENCES

- 1. Jarvis M. F., Khakh B. S. (2009) Neuropharmacology 56, 208–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Egan T. M., Samways D. S., Li Z. (2006) Pflugers Arch. 452, 501–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Verkhratsky A., Verkhrasky A., Krishtal O. A., Burnstock G. (2009) Mol. Neurobiol. 39, 190–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Anderson C. M., Nedergaard M. (2006) Trends Neurosci. 29, 257–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ward J. R., West P. W., Ariaans M. P., Parker L. C., Francis S. E., Crossman D. C., Sabroe I., Wilson H. L. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 23147–23158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wareham K., Vial C., Wykes R. C., Bradding P., Seward E. P. (2009) Br. J. Pharmacol. 157, 1215–1224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chessell I. P., Michel A. D., Humphrey P. P. A. (1997) Br. J. Pharmacol. 121, 1429–1437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rassendren F., Buell G. N., Virginio C., Collo G., North R. A., Surprenant A. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 5482–5486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Virginio C., MacKenzie A., Rassendren F. A., North R. A., Surprenant A. (1999) Nat. Neurosci. 2, 315–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Virginio C., MacKenzie A., North R. A., Surprenant A. (1999) J. Physiol. 519, 335–346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Di Virgilio F. (2007) Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 28, 465–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Takenouchi T., Sugama S., Iwamaru Y., Hashimoto M., Kitani H. (2009) Crit. Rev. Immunol. 29, 335–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lopez-Castejon G., Theaker J., Pelegrin P., Clifton A. D., Braddock M., Surprenant A. (2010) J. Immunol. 185, 2611–2619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Honore P., Donnelly-Roberts D., Namovic M., Zhong C., Wade C., Chandran P., Zhu C., Carroll W., Perez-Medrano A., Iwakura Y., Jarvis M. F. (2009) Behav. Brain Res. 204, 77–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Guile S. D., Alcaraz L., Birkinshaw T. N., Bowers K. C., Ebden M. R., Furber M., Stocks M. J. (2009) J. Med. Chem. 52, 3123–3141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]