Abstract

Osteopontin (OPN) is an integrin-binding inflammatory cytokine that undergoes polymerization catalyzed by transglutaminase 2. We have previously reported that polymeric OPN (polyOPN), but not unpolymerized OPN (OPN*), attracts neutrophils in vitro by presenting an acquired binding site for integrin α9β1. Among many in vitro substrates for transglutaminase 2, only a few have evidence for in vivo polymerization and concomitant function. Although polyOPN has been identified in bone and aorta, the in vivo functional significance of polyOPN is unknown. To determine whether OPN polymerization contributes to neutrophil recruitment in vivo, we injected OPN* into the peritoneal space of mice. Polymeric OPN was detected by immunoblotting in the peritoneal wash of mice injected with OPN*, and both intraperitoneal and plasma OPN* levels were higher in mice injected with a polymerization-incompetent mutant, confirming that OPN* polymerizes in vivo. OPN* injection induced neutrophil accumulation, which was significantly less following injection of a mutant OPN that was incapable of polymerization. The importance of in vivo polymerization was further confirmed with cystamine, a transglutaminase inhibitor, which blocked the polymerization and attenuated OPN*-mediated neutrophil recruitment. The thrombin-cleaved N-terminal fragment of OPN, another ligand for α9β1, was not responsible for neutrophil accumulation because a thrombin cleavage-incompetent mutant recruited similar numbers of neutrophils as wild type OPN*. Neutrophil accumulation in response to both wild type and thrombin cleavage-incompetent OPN* was reduced in mice lacking the integrin α9 subunit in leukocytes, indicating that α9β1 is required for polymerization-induced recruitment. We have illustrated a physiological role of molecular polymerization by demonstrating acquired chemotactic properties for OPN.

Keywords: Cell Adhesion, Cell Migration, Extracellular Matrix, Integrin, Neutrophil, Oligomer, Osteopontin, Polymer, Transglutaminase

Introduction

Osteopontin (OPN),3 an integrin-binding cytokine, plays critical roles in physiological and pathological processes, including inflammation, immunomodulation, tissue remodeling, fibrosis, mineralization (1), stem cell retention (2), and tumor metastasis (3). These functions are exerted through interactions with nine integrins and CD44 (4). OPN undergoes many types of post-translational modification, including phosphorylation (5), glycosylation, transglutamination (6), and proteolytic cleavage. Among these post-translational modifications, transglutamination (7) and thrombin-cleavage (8, 9) enhance interactions with integrins. Thrombin-cleaved N-terminal fragment of OPN (nOPN) has been found to play roles in rheumatoid arthritis (10, 11), autoimmune hepatitis (12), and stem cell retention in the bone marrow niche (2). Although OPN was found as a substrate for transglutaminase 2 (TG2; EC 2.3.2.13) earlier than thrombin, little is known about the functional role of the product of transglutamination, polymeric OPN. TG2 is a cross-linking enzyme that catalyzes isopeptide bonding between Gln and Lys residues (13) with specificity for amino acid sequences containing Gln (14). Nearly 100 proteins, including several amyloid proteins, such as amyloid β-protein and α-synuclein, are known to form multimers catalyzed by TG2 (15). Among these substrate proteins, however, only a few proteins have been demonstrated to be polymerized in vivo, and physiological and pathological meaning of the polymerization remains to be elucidated. OPN serves as a substrate for TG2 and forms polymers (polyOPN) in vivo and in vitro. The presence of polyOPN in vivo has been illustrated in bone (16) and aortic tissue of matrix Gla protein-null mice (17). Although polyOPN was functionally characterized in vitro (7, 18–20), in vivo functions of polyOPN are largely unknown. OPN is rapidly polymerized in vitro by TG2. Because TG2 is highly concentrated on cell surfaces, especially at sites of inflammation, it is likely that OPN polymerization in vivo is dynamically regulated and could contribute to regulation of tissue inflammation. OPN attracts lymphocytes (4, 21), macrophages (22, 23), and neutrophils (12, 24–26). However, neutrophil migration in response to OPN* has only been demonstrated in vivo. We and others have independently found that OPN* had no effect on neutrophil migration in vitro (12, 20), whereas polyOPN and nOPN have both been shown to be chemotactic for neutrophils. Both polyOPN and nOPN, but not OPN*, are ligands for the integrin α9β1, although the amino acid interaction sequences in polyOPN (20) or nOPN (27) are distinct. Integrin α9β1 is one of the neutrophil integrins that has been shown to contribute to chemotaxis (28).

We thus hypothesized that the chemotactic activity of OPN* observed selectively in vivo would be explained by extracellular post-translational modification, polymerization, and/or thrombin cleavage. Here we demonstrate by using two OPN mutants incompetent in polymerization or thrombin cleavage that OPN* polymerizes in vivo and that polymerization plays a critical role in the chemotactic activity of OPN for neutrophils. Further, by administering WT and mutant OPN to mice lacking the α9β1 integrin on leukocytes, we show that this effect depends on interactions of this integrin with polyOPN.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cells, Antibodies, and Reagents

Human colon cancer cell line SW480 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. FreeStyle 293F was from Invitrogen. mAb HUC750 used as a primary antibody in Western blotting for human polyOPN was described previously (20). HRP-conjugated antibody against chicken IgY was from Bethyl. The mouse OPN ELISA kit, anti-OPN mAb 34E3, and rabbit anti-mouse OPN polyclonal antibody O-17 raised against LPVKVTDSGSSEEKLY peptide were from IBL. Anti-mouse mAb Gr-1 was from BD Biosciences, and F4/80 was from Invitrogen. TG2 was prepared and provided by Dr. Yuji Saito (Tokyo Institute of Technology, Yokohama, Japan) from guinea pig livers (29). Cystamine and thrombin purified from bovine placenta were obtained form Sigma. Endotoxin was measured with Pyrogent single test vials (0.06 enzyme unit/ml sensitivity) with Escherichia coli (055:B5) endotoxin as a standard (Lonza). Polyinositic/polycytodylic acid (pIpC) was from Invitrogen.

Antibody Generation

A chicken mAb, IBM-1, was generated essentially as described previously (30). Briefly, after 2-month-old H-B15 inbred chickens were immunized, a phage-displayed library expressing immunoglobulin Fab fragments was constructed from each spleen of the chickens by fusing PCR-amplified immunoglobulin VH and VL regions. After the positive Fab phage clones were concentrated by a few rounds of panning, the Fab clone was finally reconstructed into the mouse IgG form. IBM-1 was used as a primary antibody in Western blotting for mouse polyOPN. Immunogen was a peptide including the integrin-binding site in mouse OPN, VDVPNGRGDSLAYGLR.

Recombinant OPN Proteins

As described previously (27), human OPN proteins, including two variants used for in vitro experiments, were expressed as glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion protein in E. coli with pGEX6P plasmid and affinity-purified and then cleaved from GST with PreScission protease (GE Healthcare). Human polymeric OPN was generated as described previously (20) by incubation with guinea pig TG2 and purified by anion-exchange chromatography. Purity of the product was confirmed by SDS-PAGE followed by silver staining and immunoblotting. Mouse WT and mutant OPN proteins used for in vivo injection were expressed by FreeStyle293 mammalian cells transfected with pcDNA4-myc-HisA plasmid containing each cDNA. The cells were grown in a spinner flask, and secreted OPN in culture medium was purified using a His tag at the C terminus of proteins with an Ni2+-NTA-agarose (Qiagen) column followed by elution with imidazole (Nakalai). Mouse OPN proteins were found to have endotoxin at a concentration of 0.48–0.64 enzyme unit/mg of OPN, which did not induce significant neutrophil recruitment (supplemental Fig. S1). Human and mouse polyOPN were generated by incubation with guinea pig TG2 and purified by anion-exchange chromatography (Applied Biosystems) (20).

Detection of PolyOPN

For in vitro polymerized OPN, 50 ng of human or mouse polyOPN was subjected to SDS-PAGE with a 5–20% gradient gel. After being electrotransferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, human polyOPN was probed with mAb HUC750 and mouse polyOPN was probed with mAb IBM-1 and then visualized by ECL with HRP-labeled anti-chicken IgY. For polymeric OPN in peritoneal wash, recovered PBS was first subjected to precipitation with barium citrate as described previously (31).

Migration of Neutrophils in Vitro

Human neutrophils were isolated from peripheral blood by Ficoll-Hypaque density gradient centrifugation followed by 3% dextran sedimentation. Migration was assessed using μ-slide chamber (Ibidi) in a stage top incubator (Tokai Hit) mounted onto a stage of an inverted microscope (TE2000, Nikon). 30 μl of neutrophils adjusted to 5 × 105/ml in an HBSS buffer with 0.1% BSA, 1 mm CaCl2 and MgCl2 were loaded through the cell inlet. After the reservoir was filled with 50 μl of the buffer, 10 μl of OPN*, nOPN, polyOPN, or formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (fMLP) was added at a final concentration of 1 μg/ml, 0.6 μg/ml, 2 μg/ml, and 10−6 m, respectively. Following the equilibration of the chamber for 5 min, chemokinesis of neutrophils were time lapse-captured every 20 s for 20 min by a charge-coupled device camera (Qi1, Nikon) with real-time focus correction (Perfect Focus system, Nikon), and tracks of neutrophils were traced and measured by a computer with NIS-Elements software (Nikon).

Migration of Neutrophils in Vivo

To assess chemotactic activity for neutrophils of various forms of OPN, we injected OPN proteins (20 μg/200 μl of PBS) into the peritoneal space of 8-week female C57BL6 mice followed by abdominal massage to distribute OPNs. From 1 to 24 h after injection, mice were killed under diethyl ether anesthesia, and the peritoneal space was gently washed with 3 ml of PBS by a 22-gauge needle. After RBC in the wash were lysed with NHCl3, the total cell number was counted, and neutrophil counts were enumerated from the percentage of neutrophils determined with DiffQuick-stained smears or by flow cytometry with anti-Gr-1 and -F4/80 (for evaluation of integrin subunit α9-null mice). These experimental protocols were approved by the Hiroshima University Animal Experiment Committee and by the University of California San Francisco Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Measurement of nOPN

Levels of nOPN were measured by a sandwich ELISA with mAb 34E3 immobilized on wells of an ELISA plate (Nunc) and O-17 for detection. O-17 was labeled with HRP by a labeling kit (Dojindo). Absorbance was measured at 490 nm with a reference at 590 nm.

Site-directed Mutagenesis

The QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) was used as described (32). To generate polymerization-incompetent mutant, Gln-49, -51, -57, and -70 in mouse OPN were replaced with Ala as described under “Results.” To make a thrombin cleavage-incompetent mutant, Ser-163, in the thrombin cleavage site in mouse OPN, was replaced with Asp (33).

Neutrophil Integrin Subunit α9-null Mice

Itga9Fl (34) and Mx1Cre (35) mice have been described previously. All of the mice (α9-knock-out (ITGA9Fl/Fl, Mx1Cre+) and littermate controls (ITGA9Fl/Fl), 6–8 weeks old) were treated by pIpC to induce the expression of Cre recombinase under the control of the Mx1 promoter. All mice were given pIpC (150 μg/mouse, three times, every other day) by intraperitoneal injection. Mice were available for neutrophil recruitment experiments 7 days after pIpC treatment, which was determined by the decrease of integrin α9 subunit mRNA and protein expression (supplemental Fig. S2, A and B).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were preformed by Student's t test. p values less than 0.05 were regarded as significant.

RESULTS

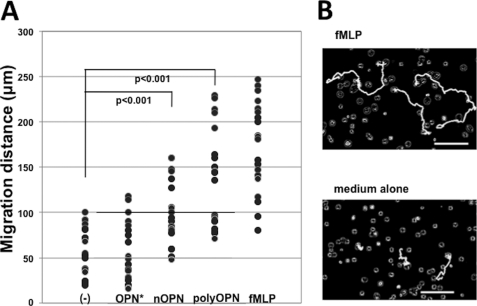

OPN* Does Not Induce Neutrophil Migration in Vitro

We have previously used the Taxiscan assay to show that polyOPN, but not OPN*, induced neutrophil migration in vitro (20). To validate the difference in neutrophil migration in vitro, we now evaluated random neutrophil migration, chemokinesis (36), on either OPN*, polyOPN, or nOPN. The magnitude of chemokinesis is shown in Fig. 1A. Each plot represents a distance of migration of ∼20 randomly selected neutrophils on OPN*, polyOPN, and nOPN in the presence of negative and positive controls (Fig. 1A). Consistent with our previous observation for directional migration, polyOPN significantly induced non-directional neutrophil migration (p < 0.001), and OPN* did not. nOPN, another ligand for integrin α9β1, was also chemotactic for neutrophils, but the magnitude of this response was less. Fig. 1B shows representative tracks of three neutrophils for positive and negative controls. Videos of the cell kinesis induced by PBS, OPN*, nOPN, polyOPN, and fMLP are presented as supplemental Movies Fig1Bvideo1.mov to Fig1Bvideo5.mov.

FIGURE 1.

Chemokinesis of neutrophils induced by three different forms of osteopontin. A, each dot represents the distance of human neutrophil migration induced by OPN* (n = 20), nOPN (n = 22), or polyOPN (n = 20) with negative (medium alone; n = 20) and positive control (fMLP; n = 21). Migrations of 20 or more randomly selected neutrophils were video-captured, and cell tracks were traced for 20 min. Cells that did not migrate were excluded as non-viable. Cells were kept at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 during the migration. B, representative computer-traced cell tracks for three cells induced by fMLP or medium alone. Bars, 100 μm. Videos of the cell kinesis induced by PBS, OPN*, nOPN, polyOPN, and fMLP are presented as supplemental Movies Fig1Bvideo1.mov to Fig1Bvideo5.mov.

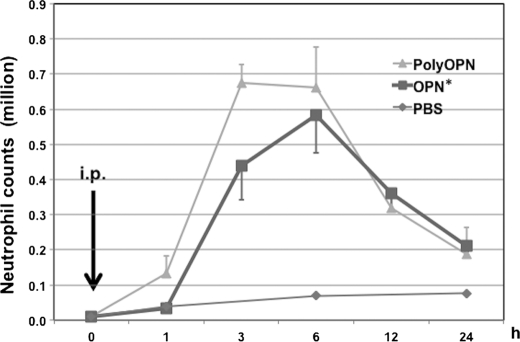

OPN* Induces Neutrophil Recruitment in Vivo

OPN has been previously shown to be chemotactic for neutrophils in vivo (24, 26). We confirmed these results by injecting OPN* into the peritoneal space of mice. After injecting 20 μg of OPN* or polyOPN, the peritoneal space was washed at 0, 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 h after injection (Fig. 2). Peritoneal neutrophil counts began to increase 3 h after injection with OPN* and peaked at 6 h. Neutrophil counts also increased after injection of polyOPN, with an earlier response, beginning at 1 h and peaking at 3 h. The minimal response of control mice confirms that our injection alone did not cause neutrophil recruitment.

FIGURE 2.

Accumulation of neutrophils after intraperitoneal injection of osteopontin. Mice were injected (i.p.) with 20 μg/200 μl of OPN* or polyOPN, and neutrophil accumulation was evaluated at 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 h after injection (n = 4, 7, 7, 4, and 4, respectively, in each group). PBS-injected control mice were evaluated 1, 6, and 24 h after injection (n = 3 at each time point). As a base line value, mice were washed without injection (n = 3). Numbers of neutrophils were calculated from total cell number, and the percentage neutrophils was determined by DiffQuick staining. Values represent the mean ± S.E. (error bars) collected in eight independent experiments.

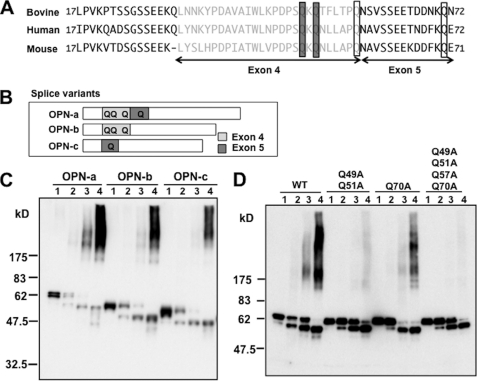

Generation of Polymerization-incompetent Mutant

TG2 catalyzes OPN polymerization by cross-linking Gln to Lys residues (13). In this process, TG2 preferentially binds to a substrate protein depending on primary structures containing reactive Gln (14). Because two Gln residues in bovine OPN have been identified as reactive for TG2 (37) and these Gln residues are within exon 4 in the OPN gene (Fig. 3A), we first performed a polymerization reaction of human splice variant product OPN-c (38), whose cDNA lacks exon 4, and compared polymerization with that of human OPN-a containing all exons and human OPN-b lacking exon 5 (Fig. 3B). Unexpectedly, although polymerization of OPN-c was attenuated compared with OPN-a, considerable polymer intensity was still seen at a TG2 concentration of 20 μg/ml (Fig. 3C). Polymerization of OPN-b was also partially attenuated compared with OPN-a, which was most apparent at 10 μg/ml TG2. We therefore thought the Gln in exon 5 was also involved in transglutamination and polymerization. To confirm importance of these Gln residues for polymerization, we next generated three mutant human OPNs and subjected them to a polymerization reaction with TG2. A mutant OPN in which Gln-51 and -53 are replaced with Ala appeared to be polymerized because of less but apparent intensity in lane 4. Next we mutated Gln-71 with Ala to observe the contribution of Gln-71 to polymerization. Attenuated intensity in lanes 3 and 4 showed involvement of Gln-71 in the polymerization. From the results of splice variants and mutants, we finally generated a mutant in which all of four Gln residues in exons 4 and 5 are mutated to Ala. As shown in Fig. 3D, this mutant showed no polymerization. We made mouse mutant OPN corresponding to this human Q51A/Q53A/Q59A/Q71A mutant and used it in further experiments of in vivo injection as a polymerization-incompetent mutant, OPN*. The polymerization incompetence of mouse mutant OPN was verified with Western blotting in supplemental Fig. S3. Incidentally, in the absence of TG2 (lane 1), Fig. 3C shows bands of OPN* of each OPN-a, OPN-b, and OPN-c with different molecular weights. Below the OPN* another band appears in the presence of TG2 (lanes 2–4), which becomes intense as the concentration of TG2 increases. Presumably, the lower bands represent intramolecularly cross-linked species (39). This tendency is more clearly seen in Fig. 3D. The difference in the intensity of the lower bands between Fig. 3C and Fig. 3D could be explained by differences in the affinity of antibodies used in each blot. mAb HUC750 used in Fig. 3C is not as efficient in recognizing the intramolecularly cross-linked species.

FIGURE 3.

In vitro polymerization of OPN variants and two polymerization-incompetent mutant OPNs. A, alignment of bovine, human, and mouse OPN matured peptides encoded by exon 3, exon 4 (gray), and exon 5. Two bovine Gln residues critical for polymerization and corresponding residues in human and murine peptides are shown by shaded boxes. In addition to the two critical Gln residues, two other Gln residues in murine OPN were mutated to generate a polymerization-incompetent mutant; they are open boxed with corresponding bovine and human residues. B, a schematic diagram of splice variants of OPN. OPN-b lacks residues coded by exon 5, and OPN-c lacks residues coded by exon 4. Gln residues in these exons are shown as Q. C and D, Western blotting of the transglutaminase 2-catalyzed polymerization reaction of human OPN. Lanes 1 of each OPN show a reaction with no transglutaminase 2; lanes 2, 5 μg/ml; lanes 3, 10 μg/ml; lanes 4, 20 μg/ml. C, splice variants OPN-a, -b, and -c (human recombinant) were subjected to the polymerization and probed with HUC750. D, WT and three mutant OPNs (mouse recombinant), in which one, two, or four Gln residues, as indicated above, are replaced with Ala were polymerized and probed with IBM-1.

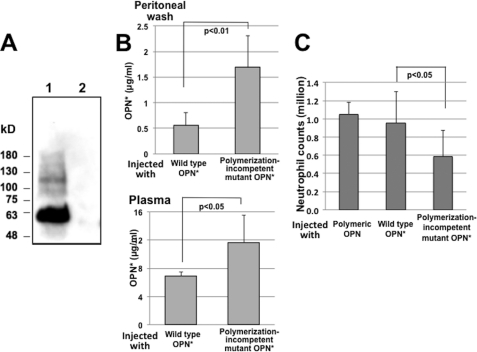

In Vivo Conversion of OPN* into PolyOPN

OPN* exerted chemotactic activity for neutrophils in vivo but not in vitro. In vivo, there are diverse cells that could produce a variety of secondary chemotactic factors in response to OPN*. However, because we demonstrated that polyOPN is chemotactic for neutrophils both in vitro and in vivo, we considered the possibility that OPN* induced neutrophil recruitment through conversion to polyOPN in vivo. As expected, Western blotting of barium citrate-precipitated peritoneal wash 3 h after injection with mAb IBM-1 revealed OPN* and polyOPN with a molecular mass of ∼60 and 80–200 kDa, respectively (Fig. 4A). Further, we measured levels of OPN* and nOPN in peritoneal wash or plasma of the mice 3 h after injection of OPN* and compared the levels of OPN* and nOPN with those of mice injected with polymerization-incompetent mutant OPN. Because some mAbs against OPN recognize polyOPN, we tested several ELISA systems developed in our hands or in commercial laboratories. An ELISA kit that does not recognize either polymeric or nOPN but detects OPN* and a polymerization-incompetent mutant with equal sensitivity (supplemental Fig. S4) was employed in this experiment. For specific detection of nOPN, we developed an ELISA system by using antibodies O-17 for detection and 34E3 for capture that bind the SVVYGLR sequence in OPN, which is exposed only in nOPN and not in OPN* or polyOPN. The specificity and standard curve of the ELISA are shown in supplemental Fig. S5A. If injected OPN* is converted into polyOPN, levels of OPN* should decrease in comparison with levels after injection of a polymerization-incompetent mutant. We found that levels of OPN* were significantly higher in both the peritoneal wash and plasma after injection of polymerization-incompetent OPN* than after injection of WT OPN* (Fig. 4B). In addition, levels of nOPN in peritoneal wash or plasma after OPN* injection were detectable but were lower by two digits than OPN* (supplemental Fig. S5B), which would have negligibly small effects compared with OPN*. Overall, these results indicate that OPN* is converted into polyOPN but not into nOPN after injection into the peritoneal cavity of mice.

FIGURE 4.

In vivo polymerization of injected OPN and decrease in neutrophil recruitment after injection of polymerization-incompetent mutant OPN. A, Western blotting of osteopontin in the peritoneal wash of mice 3 h after injection with non-polymerized OPN. Samples were precipitated with barium citrate from a 5-ml pool of peritoneal wash of each of the three mice. Lane 1, injected with OPN; lane 2, injected with PBS. B, concentration of intact non-polymerized OPN in the peritoneal space (n = 3 in each group) and the circulation (n = 3 in each group) after intraperitoneal injection of wild type or mutant OPN (20 μg/200 μl of PBS) measured by an ELISA that detects intact non-polymerized OPN but does not detect the N-terminal fragment of thrombin-cleaved OPN or polymeric OPN. C, neutrophil counts in the peritoneal space 3 h after injection (n = 5, polymeric OPN; n = 9, WT and the mutant OPN). Values represent the mean ± S.D. (error bars) collected in two (polymeric) or three (WT and mutant) independent experiments.

Reduced Neutrophil Recruitment by Polymerization-incompetent Mutant OPN* in Vivo

We next directly examined whether the ability of OPN* to polymerize in vivo contributes to OPN-induced neutrophil recruitment by comparing recruitment in response to polyOPN, WT OPN*, or polymerization-incompetent OPN. Significantly fewer neutrophils were recruited in response to polymerization-incompetent OPN (Fig. 4C). To exclude the possibility that attenuation of neutrophil recruitment was due to impaired interaction with integrins due to conformational change of the integrin binding sites, we compared integrin-mediated cell adhesion to this mutant and WT OPN*. Adhesion of SW480 cells to this mutant was comparable with adhesion to WT OPN* (supplemental Fig. S6).

Inhibition of OPN* Polymerization by Transglutaminase Inhibitor, Cystamine, Attenuated Neutrophil Recruitment after Injection of OPN*

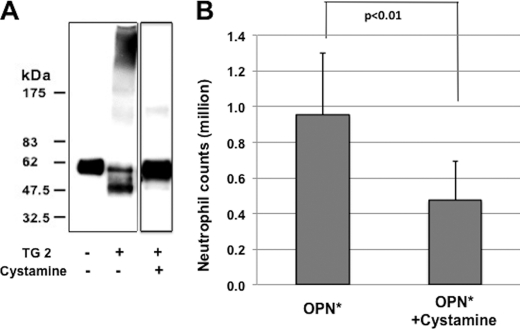

To further confirm the role of polymerization in OPN-induced neutrophil recruitment, we examined the effects of blocking polymerization by the TG2 inhibitor, cystamine (40). Cystamine was found to inhibit OPN* polymerization by Western blotting (Fig. 5A). Cystamine reduced OPN-mediated neutrophil recruitment by ∼50% (Fig. 5B). To avoid possible unwanted effects of cystamine in vivo, we incubated OPN* with cystamine and TG2 in vitro followed by filtration centrifugation to remove free cystamine before injection. Therefore, it is not likely that the inhibitory effect was due to unwanted effects derived from bioactivity of cystamine.

FIGURE 5.

Reduction of OPN-induced neutrophil accumulation by inhibition of in vivo polymerization of OPN. A, Western blotting of transglutaminase 2 (20 μg/ml)-induced OPN polymerization reaction in the presence or absence of cystamine (560 μg/ml). Mouse recombinant OPN was used and probed with IBM-1. The reaction with cystamine was loaded in a different gel from those without cystamine. B, reduction of neutrophil counts in the peritoneal space of mice 3 h after injection in the absence (n = 9) or presence of the polymerization blocker, cystamine (n = 12). Values represent the mean ± S.D. (error bars) collected in three (no blocker) or four (cystamine) independent experiments.

Inhibition of Thrombin Cleavage of OPN Does Not Reduce Neutrophil Recruitment

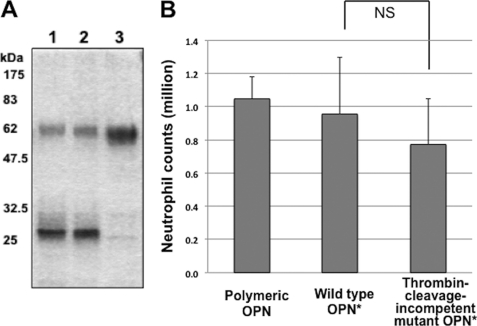

In this study, besides polyOPN, nOPN induced neutrophil migration in vitro (Fig. 1A), as has been previously reported (12). As presented above, this active fragment was minimally but measurably present in the peritoneal space and plasma after OPN* injection. To exclude the possibility that nOPN was responsible for the neutrophil accumulation following OPN* injection, we generated another mutant OPN that is protected against thrombin cleavage (Fig. 6A) (33). This cleavage-incompetent mutant induced neutrophil recruitment comparable with that induced by WT OPN* or polyOPN (Fig. 6B). Thus, both the minimal amount of nOPN generated and the normal neutrophil recruitment by this cleavage-incompetent mutant suggest that neutrophil recruitment in response to injection of OPN* is not dependent on thrombin cleavage.

FIGURE 6.

Thrombin resistance of thrombin cleavage-incompetent mutant and neutrophil accumulation after injection of the thrombin cleavage-incompetent mutant OPN. A, SDS-PAGE of digestion reactions with thrombin (0.4 unit/μg of OPN) stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. WT (lane 1), polymerization-incompetent mutant (lane 2), or thrombin cleavage-incompetent mutant OPN (lane 3) was subjected to the reaction, and 1 μg of OPNs were loaded onto lanes. B, neutrophil counts in the peritoneal space of mice 3 h after injection of 20 μg/200 μl of polymeric (n = 5), WT (n = 9), or thrombin cleavage-incompetent mutant OPN (n = 12). Values represent the mean ± S.D. (error bars) collected in two (polymeric), three (WT), or four (mutant) independent experiments. Mouse recombinant proteins were used. NS, not significant.

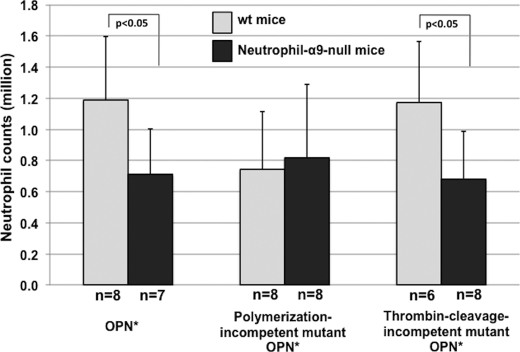

Neutrophil Accumulation by Injection of WT OPN or Thrombin Cleavage-incompetent Mutant Was Reduced in Mice Lacking Integrin α9 Subunit on Leukocytes

To determine whether in vivo neutrophil recruitment by polymerized OPN is mediated by interaction with the α9β1 integrin, we generated mice lacking integrin subunit α9 expression on all leukocytes. OPN*-induced neutrophil recruitment into the peritoneal space was significantly reduced in mice lacking the integrin α9 subunit on leukocytes (Fig. 7). Similar results were obtained after injection of the thrombin cleavage-incompetent mutant. In contrast, recruitment in response to the polymerization-incompetent mutant was reduced in WT mice but unaffected by the loss of integrin α9 subunit on leukocytes. These results indicate that the OPN*-induced migration is at least in part mediated by α9β1 and further confirm the importance of polymerization but not thrombin cleavage in this response.

FIGURE 7.

Neutrophil accumulation in WT and neutrophil α9-null mice by injection of WT, polymerization-incompetent mutant, or thrombin cleavage-incompetent OPN. WT OPN, polymerization-incompetent mutant OPN, or thrombin cleavage-incompetent OPN was injected in the peritoneal space of mice that lack the integrin α9 subunit on neutrophils. Neutrophils in the peritoneal space were counted 4 h after injection. The numbers of the mice are indicated below each bar. Values represent the mean ± S.D. (error bars).

DISCUSSION

We have previously reported that polyOPN utilizes integrin α9β1 to attract neutrophils in vitro. In this study, we have provided in vivo evidence for OPN* polymerization and concomitant neutrophil recruitment mediated by integrin α9β1. We also confirmed the chemotactic activity of nOPN for neutrophils in vitro but showed that thrombin cleavage is minimal in response to intraperitoneal injection of OPN* and is not required for neutrophil recruitment in vivo.

The in vivo presence of polymeric OPN has previously been shown in bone (16) and calcified aorta of matrix Gla protein-null mice (17). The immunoreactivity of polymeric OPN identified in the peritoneal wash shows that OPN* undergoes polymerization in vivo within 3 h. The majority of the polymers in the blot range from 80 to 200 kDa, which may differ depending on polymerizing conditions, because the previously reported in vivo polyOPNs (16, 17) are 200 kDa. The decrease in levels of OPN* in the peritoneal wash or the plasma by ELISA supports the in vivo conversion of OPN* into polyOPN. OPN is an inflammatory cytokine that exerts chemotactic activity for leukocytes (41), including neutrophils (26). We (20) and others (12) have recently reported, however, that unprocessed OPN* does not induce neutrophil chemotaxis in vitro, whereas we showed that polyOPN is a potent neutrophil chemoattractant (20). We now show that non-directional migration of neutrophils in vitro also requires polymerization or thrombin cleavage. Two other reports described chemotactic activity of OPN* for neutrophils, but both relied on injecting OPN* into the peritoneal space of mice (26) or rats (24). The injection of OPN* in mice in the present study confirmed the in vivo chemotactic effects on neutrophils and also showed that polyOPN induced the same response with shorter latency. Collectively, these results appear to definitively rule out direct effects of unprocessed OPN* on neutrophil migration, despite its ability to induce neutrophil recruitment in vivo. We have demonstrated the OPN* polymerization-induced in vivo accumulation of neutrophils based on the observations that this response was significantly inhibited by genetic or pharmacologic interference with OPN* polymerization. In addition to this polymerization-dependent mechanism, OPN* itself attracts neutrophils in non-polymeric form, because there was residual neutrophil recruitment even after polymerization was inhibited. The polymerization-independent migration could be explained by cellular responses to OPN* injection in the peritoneal space. Because OPN is a potent macrophage activator (22, 23), peritoneal resident macrophages of the OPN*-injected mice were activated to produce inflammatory mediators that cause acute peritoneal inflammation. The mesothelium, a barrier against bacterial insults or injury, actively participates in peritoneal immune defense, synthesizing a plethora of cytokines, including IL-8 (42); mesothelial cells could therefore be a huge source of chemoattractants in response to intraperitoneal injection of OPN*.

OPN* can also be cleaved by thrombin to generate nOPN with enhanced interaction with integrins (8, 9), including α9β1 (27, 43), similar to the effects of polymerization (7, 20). In vitro, we found that nOPN induced neutrophil kinesis, in accordance with a previous report showing nOPN-induced chemotaxis of neutrophils from the liver of concanavalin A hepatitis mice (12). However, the lack of effect of inhibition of thrombin cleavage on neutrophil accumulation in the present study suggests that thrombin cleavage is not required for OPN*-induced chemotaxis in vivo into the peritoneal space of mice. Nonetheless, the relative in vivo importance of thrombin cleavage still remains to be elucidated under other various conditions. Recently, higher levels of expression of nOPN have been detected in synovial fluid (11) and urine (44) from patients with rheumatoid arthritis than in healthy subjects. Pathological roles of nOPN have also been demonstrated in models of rheumatoid arthritis (10) and autoimmune hepatitis (12), and a physiological role has been suggested in regulation of retention of hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow niche (2). Importantly, polyOPN is able to bind to α9β1 and initiate signals independently from nOPN. Cross-linked polymers are resistant to proteolytic enzymes, as has been well described for amyloid β-protein (45, 46). In contrast, OPN* is susceptible to cleavage by several proteases, including thrombin (8), matrix metalloproteinases (47), plasmin, or cathepsin D (48), with at least 20 cleavage sites known. Thrombin-cleaved nOPN contains further cleavage sites for matrix metalloproteinase-3, matrix metalloproteinase-7, or cathepsin D. Thus, the enhanced interaction with integrins (7) and prolonged half-life of polyOPN might lead to consistent and sustained signaling through integrins. Integrin α9β1 engagement on neutrophils has been reported to inhibit apoptosis (49, 50). The relatively long lived, non-proteolyzed polyOPN could thus play a role in chronicity of inflammatory response.

There are three forms of OPN that attract neutrophils: polyOPN, OPN* (in vivo), and nOPN (in vitro). nOPN appeared not to be involved in the neutrophil migration into the peritoneal space because generation of nOPN was minimal after OPN* injection. The migratory effect of OPN* may not be reproduced by the site of action because the in vivo neutrophil migratory effect of OPN* requires secondary mediators, such as from peritoneal macrophages and mesothelium. On the other hand, polyOPN is produced from OPN* in vivo and has a direct chemotactic effect. PolyOPN thus appears to dominantly contribute to neutrophil recruitment. However, it is possible that locally and temporally, nOPN could be selectively concentrated at sites where thrombin is highly expressed and activated because specific roles of nOPN have been reported (2, 11, 12). Therefore, the effects of these three forms on neutrophil recruitment depend greatly on environments of OPN that regulate the post-translational modifications. In addition, the polymerizing modification is catalyzed by blood coagulation factor XIII, a member of the transglutaminase family. In contrast to the ubiquitous distribution of TG2, the coagulation reaction is strictly controlled to limit hemostasis within spatial and temporal requirements. At the site where factor XIII is activated, the polymerization may also be catalyzed by this enzyme.

Besides α9β1, there are two other β1 integrins, α5β1 and α6β1 (51), expressed on neutrophils. β2 integrins have been known as primary leukocyte integrins playing critical roles in neutrophil rolling and tethering on vascular endothelial cells. Under resting conditions, expression levels of α9β1 and α5β1 are comparable, but α9β1 is up-regulated 2–3-fold upon stimulation of neutrophils, whereas α5β1 levels remain unchanged (28). Furthermore, α9β1 synergizes with β2 integrins under flow conditions (28). Therefore, the contribution of α9β1 to neutrophil accumulation in response to polymerized OPN is not surprising.

In the process of generating the polymerization-incompetent mutant, we demonstrated that the variations of splicing of OPN are closely related to polymerization competence. OPN-c, which lacks exon 4, has been reported to be expressed selectively in tumor tissues and correlated with tumor grade (52–56). Whereas OPN-a aggregates and enhances cell adhesion and therefore attenuates dissemination of tumor cells, OPN-c supports tumor invasion because of its lack of aggregation (52). The non-aggregative nature of OPN-c is in concert with the relative resistance to polymerization we showed in this paper. The mutations for the polymerization-incompetent mutant showed that Gln residues in exon 4 are critical for TG2-induced polymerization. As we have shown in this paper, however, OPN-c could polymerize in the presence of a high concentration of TG2.

For a number of substrates for TG2-catalyzed polymerization (15), biological functions of the resultant polymers are still obscure. An emerging body of evidence, however, indicates critical roles of TG2-induced polymerization in neurodegenerative diseases (57). A pathologic feature of Parkinson disease, the Lewy body, is the result of transglutamination of α-synuclein (58). TG2 is required for amyloid β-protein to form polymers at the physiological concentration (46). About 20 distinct proteins that form amyloid develop a common structure reacting to the same antibody (59). Neurotoxicity of amyloid β-protein in Alzheimer disease is likely to be acquired upon polymerization (46). The present study along with our previous work (20) illustrates that polymerization of a protein can form a new active site that is involved in a protein-protein interaction.

In the present study, we have demonstrated that OPN* rapidly converts into polyOPN by post-translational modification and gains a new function, chemotactic activity for neutrophils. We suggest that elucidating in vivo responses to this polymer may have emerging importance in understanding the functions of osteopontin in vivo. This gain of function based on new protein-protein interactions (20) might provide clues to the in vivo roles of other important protein polymers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Drs. Kiyotaka Hitomi (Nagoya University) and Soichi Kojima (RIKEN) for discussions on the functions of polymers upon transglutamination and on Western detection of the polymer and Eiko Kawamoto and Miho Imoto for technical assistance. We also thank the Research Center for Molecular Medicine and the Analysis Center of Life Science (Hiroshima University) for the use of facilities.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant HL64353 (to D. S.). This work was also supported by a grant-in-aid from the Japanese Ministry of Science, Sports, and Culture (to H. M. and Y. Y.), by a grant from the Japan New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (to N. N., H. M., and Y. Y.), and by a grant from the Tsuchiya Memorial Medical Foundation (to Y. Y.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S6 and Movies Fig1Bvideo1.mov to Fig1Bvideo5.mov.

- OPN

- osteopontin

- OPN*

- intact non-polymerized osteopontin

- polyOPN

- polymeric OPN

- nOPN

- N-terminal fragment of thrombin-cleaved osteopontin

- TG2

- transglutaminase 2

- fMLP

- formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine

- pIpC

- polyinositic/polycytodylic acid.

REFERENCES

- 1. Denhardt D. T., Noda M., O'Regan A. W., Pavlin D., Berman J. S. (2001) J. Clin. Invest. 107, 1055–1061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Grassinger J., Haylock D. N., Storan M. J., Haines G. O., Williams B., Whitty G. A., Vinson A. R., Be C. L., Li S., Sørensen E. S., Tam P. P., Denhardt D. T., Sheppard D., Choong P. F., Nilsson S. K. (2009) Blood 114, 49–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McAllister S. S., Gifford A. M., Greiner A. L., Kelleher S. P., Saelzler M. P., Ince T. A., Reinhardt F., Harris L. N., Hylander B. L., Repasky E. A., Weinberg R. A. (2008) Cell 133, 994–1005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Weber G. F., Ashkar S., Glimcher M. J., Cantor H. (1996) Science 271, 509–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Christensen B., Kazanecki C. C., Petersen T. E., Rittling S. R., Denhardt D. T., Sørensen E. S. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 19463–19472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Prince C. W., Dickie D., Krumdieck C. L. (1991) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 177, 1205–1210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Higashikawa F., Eboshida A., Yokosaki Y. (2007) FEBS Lett. 581, 2697–26701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Senger D. R., Perruzzi C. A., Papadopoulos-Sergiou A., Van de Water L. (1994) Mol. Biol. Cell. 5, 565–574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yokosaki Y., Tanaka K., Higashikawa F., Yamashita K., Eboshida A. (2005) Matrix Biol. 24, 418–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yamamoto N., Sakai F., Kon S., Morimoto J., Kimura C., Yamazaki H., Okazaki I., Seki N., Fujii T., Uede T. (2003) J. Clin. Invest. 112, 181–188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hasegawa M., Nakoshi Y., Iino T., Sudo A., Segawa T., Maeda M., Yoshida T., Uchida A. (2009) J. Rheumatol. 36, 240–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Diao H., Kon S., Iwabuchi K., Kimura C., Morimoto J., Ito D., Segawa T., Maeda M., Hamuro J., Nakayama T., Taniguchi M., Yagita H., Van Kaer L., Onóe K., Denhardt D., Rittling S., Uede T. (2004) Immunity 21, 539–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lorand L., Graham R. M. (2003) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 4, 140–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sugimura Y., Hosono M., Wada F., Yoshimura T., Maki M., Hitomi K. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 17699–17706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Esposito C., Caputo I. (2005) FEBS J. 272, 615–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kaartinen M. T., El-Maadawy S., Räsänen N. H., McKee M. D. (2002) J. Bone Miner. Res. 17, 2161–2173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kaartinen M. T., Murshed M., Karsenty G., McKee M. D. (2007) J. Histochem. Cytochem. 55, 375–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kaartinen M. T., Pirhonen A., Linnala-Kankkunen A., Mäenpää P. H. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 22736–22741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kaartinen M. T., Pirhonen A., Linnala-Kankkunen A., Mäenpää P. H. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 1729–1735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nishimichi N., Higashikawa F., Kinoh H. H., Tateishi Y., Matsuda H., Yokosaki Y. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 14769–14776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. O'Regan A. W., Chupp G. L., Lowry J. A., Goetschkes M., Mulligan N., Berman J. S. (1999) J. Immunol. 162, 1024–1031 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Singh R. P., Patarca R., Schwartz J., Singh P., Cantor H. (1990) J. Exp. Med. 171, 1931–1942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Giachelli C. M., Lombardi D., Johnson R. J., Murry C. E., Almeida M. (1998) Am. J. Pathol. 152, 353–358 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Apte U. M., Banerjee A., McRee R., Wellberg E., Ramaiah S. K. (2005) Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 207, 25–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Banerjee A., Apte U. M., Smith R., Ramaiah S. K. (2006) J. Pathol. 208, 473–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Koh A., da Silva A. P., Bansal A. K., Bansal M., Sun C., Lee H., Glogauer M., Sodek J., Zohar R. (2007) Immunology 122, 466–475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yokosaki Y., Matsuura N., Sasaki T., Murakami I., Schneider H., Higashiyama S., Saitoh Y., Yamakido M., Taooka Y., Sheppard D. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 36328–36334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mambole A., Bigot S., Baruch D., Lesavre P., Halbwachs-Mecarelli L. (2010) J. Leukoc. Biol. 88, 321–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Takahashi H., Isobe T., Horibe S., Takagi J., Yokosaki Y., Sheppard D., Saito Y. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 23589–23595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sato Y., Nishimichi N., Nakano A., Takikawa K., Inoue N., Matsuda H., Sawamura T. (2008) Atherosclerosis 200, 303–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rittling S. R., Chen Y., Feng F., Wu Y. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 9175–9182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yokosaki Y., Matsuura N., Higashiyama S., Murakami I., Obara M., Yamakido M., Shigeto N., Chen J., Sheppard D. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 11423–11428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chang J. Y. (1985) Eur. J. Biochem. 151, 217–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Singh P., Chen C., Pal-Ghosh S., Stepp M. A., Sheppard D., Van De Water L. (2009) J. Invest Dermatol. 129, 217–228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kühn R., Schwenk F., Aguet M., Rajewsky K. (1995) Science 269, 1427–1429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Petrie R. J., Doyle A. D., Yamada K. M. (2009) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10, 538–549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sørensen E. S., Rasmussen L. K., Møller L., Jensen P. H., Højrup P., Petersen T. E. (1994) Biochem. J. 304, 13–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Saitoh Y., Kuratsu J., Takeshima H., Yamamoto S., Ushio Y. (1995) Lab. Invest. 72, 55–63 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yamaguchi Y., Hanashima S., Yagi H., Takahashi Y., Sasakawa H., Kurimoto E., Iguchi T., Kon S., Uede T., Kato K. (2010) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 393, 487–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lorand L., Siefring G. E., Jr., Lowe-Krentz L. (1978) J. Supramol. Struct. 9, 427–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. O'Regan A., Berman J. S. (2000) Int. J. Exp. Path. 81, 373–390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yung S., Chan T. M. (2009) Perit. Dial. Int. 29, S21–S27 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Smith L. L., Cheung H. K., Ling L. E., Chen J., Sheppard D., Pytela R., Giachelli C. M. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 28485–28491 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Shio K., Kobayashi H., Asano T., Saito R., Iwadate H., Watanabe H., Sakuma H., Segawa T., Maeda M., Ohira H. (2010) J. Rheumatol. 37, 704–710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zemskov E. A., Janiak A., Hang J., Waghray A., Belkin A. M. (2006) Front. Biosci. 11, 1057–1076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hartley D. M., Zhao C., Speier A. C., Woodard G. A., Li S., Li Z., Walz T. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 16790–16800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Agnihotri R., Crawford H. C., Haro H., Matrisian L. M., Havrda M. C., Liaw L. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 28261–28267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Christensen B., Schack L., Kläning E., Sørensen E. S. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 7929–7937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ross E. A., Douglas M. R., Wong S. H., Ross E. J., Curnow S. J., Nash G. B., Rainger E., Scheel-Toellner D., Lord J. M., Salmon M., Buckley C. D. (2006) Blood 107, 1178–1183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Saldanha-Gama R. F., Moraes J. A., Mariano-Oliveira A., Coelho A. L., Walsh E. M., Marcinkiewicz C., Barja-Fidalgo C. (2010) Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1803, 848–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Shang T., Yednock T., Issekutz A. C. (1999) J. Leukoc. Biol. 66, 809–816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. He B., Mirza M., Weber G. F. (2006) Oncogene 25, 2192–2202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Mirza M., Shaughnessy E., Hurley J. K., Vanpatten K. A., Pestano G. A., He B., Weber G. F. (2008) Int. J. Cancer 122, 889–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sullivan J., Blair L., Alnajar A., Aziz T., Ng C. Y., Chipitsyna G., Gong Q., Witkiewicz A., Weber G. F., Denhardt D. T., Yeo C. J., Arafat H. A. (2009) Surgery 146, 232–240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Chae S., Jun H. O., Lee E. G., Yang S. J., Lee D. C., Jung J. K., Park K. C., Yeom Y. I., Kim K. W. (2009) Int. J. Oncol. 35, 1409–1416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Yan W., Qian C., Zhao P., Zhang J., Shi L., Qian J., Liu N., Fu Z., Kang C., Pu P., You Y. (2010) Neuro. Oncol. 12, 765–775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Caccamo D., Currò M., Condello S., Ferlazzo N., Ientile R. (2010) Amino Acids 38, 653–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Nemes Z., Petrovski G., Aerts M., Sergeant K., Devreese B., Fésüs L. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 27252–27264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kayed R., Head E., Thompson J. L., McIntire T. M., Milton S. C., Cotman C. W., Glabe C. G. (2003) Science 300, 486–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.