Abstract

Internalization of the Na+/H+ exchanger NHE5 into recycling endosomes is enhanced by the endocytic adaptor proteins β-arrestin1 and -2, best known for their preferential recognition of ligand-activated G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). However, the mechanism underlying their atypical association with non-GPCRs, such as NHE5, is unknown. In this study, we identified a highly acidic, serine/threonine-rich, di-isoleucine motif (amino acids 697–723) in the cytoplasmic C terminus of NHE5 that is recognized by β-arrestin2. Gross deletions of this site decreased the state of phosphorylation of NHE5 as well as its binding and responsiveness to β-arrestin2 in intact cells. More refined in vitro analyses showed that this site was robustly phosphorylated by the acidotropic protein kinase CK2, whereas other kinases, such as CK1 or the GPCR kinase GRK2, were considerably less potent. Simultaneous mutation of five Ser/Thr residues within 702–714 to Ala (702ST/AA714) abolished phosphorylation and binding of β-arrestin2. In transfected cells, the CK2 catalytic α subunit formed a complex with NHE5 and decreased wild-type but not 702ST/AA714 NHE5 activity, further supporting a regulatory role for this kinase. The rate of internalization of 702ST/AA714 was also diminished and relatively insensitive to overexpression of β-arrestin2. However, unlike in vitro, this mutant retained its ability to form a complex with β-arrestin2 despite its lack of responsiveness. Additional mutations of two di-isoleucine-based motifs (I697A/L698A and I722A/I723A) that immediately flank the acidic cluster, either separately or together, were required to disrupt their association. These data demonstrate that discrete elements of an elaborate sorting signal in NHE5 contribute to β-arrestin2 binding and trafficking along the recycling endosomal pathway.

Keywords: Endocytosis, G Protein-coupled Receptors (GPCR), Membrane Trafficking, Protein Motifs, Protein Phosphorylation, Protein Sorting, Serine Threonine Protein Kinase, Sodium Proton Exchange

Introduction

Mammalian Na+/H+ exchangers (NHEs2; also known as NHAs) constitute a family of at least 11 genes that are expressed in a ubiquitous or tissue-specific manner (1, 2), although other more distantly related transporters that remain poorly characterized could add to their heterogeneity (3, 4). Within cells, they are sorted differentially to various membrane compartments, including discrete microdomains of the plasma membrane (e.g. lamellipodia of fibroblasts, apical or basolateral surface of epithelia), trans-Golgi network, and endosomes, where they play fundamental roles in cellular as well as systemic pH, electrolyte, and fluid volume homeostasis. In so doing, they modulate a myriad of physiological processes, including cell shape, growth, proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis (1, 2, 5). Despite knowledge of their structural and functional diversity, little is known about the molecular mechanisms that selectively target these transporters to distinct membrane compartments.

Among the NHEs, NHE5 is intriguing because of its abundant expression in the central nervous system (6, 7). Studies of its subcellular distribution in transfected neurons and non-neuronal cells show that it is sorted not only to the plasma membrane but also to recycling endosomes via a clathrin-dependent mechanism (8). Subsequent analyses have uncovered a direct role for the secretory carrier membrane protein SCAMP2 in shuttling NHE5 to the cell surface (9), whereas the monomeric clathrin-associated sorting proteins β-arrestin1 and β-arrestin2 (β-Arr1 and β-Arr2) have been implicated in its internalization (10). This latter finding was initially surprising because β-arrestins were generally regarded as specialized adaptors that bound preferentially to agonist-activated seven-transmembrane G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) (11), although certain single-transmembrane receptors, such as insulin-like growth factor I (12), transforming growth factor-β (13), and low density lipoprotein (14), were also found to be targets. However, increasing evidence has revealed that β-arrestins are capable of interacting with other types of integral membrane proteins. Aside from NHE5, β-arrestins also recognize voltage-dependent calcium channels (15, 16) and the Na+/K+-ATPase pump (17). However, the molecular mechanisms that enable β-arrestins to interact with such diverse membrane cargo and the regulatory relevance of these atypical associations have yet to be fully elucidated.

The current model for high affinity β-arrestin-GPCR interactions posits that β-arrestins recognize agonist-activated GPCRs after the receptors have been phosphorylated at clusters of Ser/Thr residues located mainly within their cytoplasmic C terminus and/or third intracellular loop by a family of specialized G protein-coupled receptor kinases (GRK1 to -7) (18–22). Although less prominent, other Ser/Thr protein kinases, such as protein kinase A (23), PKC (24–27), CK1 (28–30), and CK2 (31, 32) (formerly called casein kinase 1 and 2, respectively), can also phosphorylate GPCRs and, operating either independently or jointly with other kinases, contribute to their desensitization, internalization, and/or signaling. Despite general acceptance of this model, a number of exceptions to the classical paradigm of β-arrestin-mediated endocytosis of GPCRs have emerged over the last few years. β-Arrestins are capable of binding and promoting the internalization of a number of unphosphorylated receptors (33–38). Although the mechanisms are not fully understood, in some cases, the presence of accessible acidic residues is thought to be sufficient for interaction with β-arrestin and subsequent internalization (33, 37). Whether the association of β-arrestins with NHE5 conforms to any of these described mechanisms or involves an entirely different mode of interaction is unknown.

In the present study, we have identified an unusually acidic Ser/Thr-rich di-isoleucine motif in the cytoplasmic C terminus of NHE5 that is recognized by β-arrestin2, sharing some likeness to canonical acidic dileucine sorting signals. Phosphorylation of this signal sequence by protein kinase CK2 and functioning in concert with the di-isoleucine sequences confer avid binding of β-arrestin2 and enhance NHE5 trafficking along the recycling endosomal pathway.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Antibodies were obtained from the following sources. Mouse monoclonal anti-HA antibody (16B12) was purchased from Covance Inc. (Richmond, CA); rabbit polyclonal anti-HA antibody (ab9110) was from Abcam (Cambridge, MA); goat anti-mouse and anti-rabbit secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 and 568 were obtained from Invitrogen; mouse monoclonal anti-FLAG antibody (F3165) was purchased from Sigma; horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-mouse and anti-rabbit IgG were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Rabbit polyclonal anti-NHE5 (#3568, recognizing residues 789–896 of the cytoplasmic C terminus) was developed in our laboratory. Hoechst 33342, wheat germ agglutinin coupled to Alexa Fluor 594, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI), and fibronectin (F0895) were purchased from Sigma. The pGEX-2T expression vector was obtained from GE Healthcare. Purified protein kinases CK1 and CK2 were purchased from New England Biolabs (Pickering, Canada). Purified G protein receptor kinase GRK2 was a generous gift from Dr. R. J. Lefkowitz (Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC). The TNT®-coupled reticulocyte lysate system was from Promega (Madison, WI). FuGene 6 transfection reagent was from Roche Applied Science. Amplex Red reagent, Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; high glucose), α-minimal essential medium (α-MEM), fetal bovine serum, goat serum, penicillin/streptomycin, Lipofectamine, and trypsin-EDTA were purchased from Invitrogen. Proteinase inhibitor mixture was obtained from Roche Applied Science. All other chemicals and reagents used in these experiments were obtained from BioShop Canada (Burlington, Canada) or Fisher and were of the highest grade.

Plasmids and Gene Constructs

During the course of this work, some constructs were tagged in identical positions with different epitopes and used interchangeably, depending on the nature of the experiment and quality of the commercially available antibodies at any given time. A mammalian expression plasmid containing the human NHE5 cDNA tagged with a triple influenza virus hemagglutinin (HA) epitope in its first exomembranous loop (NHE5HA3) was described previously (10). An analogous FLAG-tagged variant of NHE5 was also constructed by replacing the triple HA tag with a corresponding triple FLAG tag. Construction of β-Arr2myc was described previously (10). An expression plasmid containing β-Arr2FLAG was kindly provided by Dr. S. Laporte (McGill University, Montreal, Canada). Expression plasmids containing the catalytic α and α′ subunit isoforms of protein kinase CK2 were modified by the addition of an HA tag at their amino termini (CK2αHA and CK2α′HA), as described previously (39). Site-directed mutagenesis of NHE5 was conducted using the QuikChangeTM site-directed mutagenesis protocol and Pfu Turbo DNA polymerase (Stratagene) or by standard polymerase chain reaction (PCR) mutagenesis using specific pairs of oligonucleotides containing the desired mutations. Glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins encoding different parts of the C terminus of NHE5 were generated by PCR and inserted in-frame with GST using the bacterial pGEX-2T expression vector. The fidelity of all sequences was verified by automated DNA sequencing.

Cell Culture

Parental Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells and a chemically mutagenized CHO cell line devoid of endogenous plasmalemmal Na+/H+ exchange activity (AP-1 cells) (40) were maintained in complete α-MEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 units/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 25 mm NaHCO3 (pH 7.4) and incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2. GripTiteTM 293 MSR cells, a derivative of the human embryonic kidney HEK-293 cell line that adheres more strongly to tissue culture dishes (Invitrogen), were maintained in DMEM (high glucose) supplemented with 10% FBS and 500 μg/ml G418 and incubated in a humidified atmosphere at 37 °C and 5% CO2.

In Vitro Kinase and Protein Binding Assays

Plasmids encoding different segments of the cytoplasmic C terminus of NHE5 fused to GST were transformed into the Escherichia coli BL21 strain. Cultures of clonal BL21 cells were grown overnight and then diluted 10-fold. Protein expression was induced by further incubation in the presence of 0.4 mm isopropyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside at 30 °C for 2 h. Cells were lysed in 0.5% Nonidet P-40 buffer (0.5% Nonidet P-40, 1 mm EDTA, and complete proteinase inhibitor mixture in phosphate-buffered saline), and the GST fusion proteins were purified as described (41). Equal amounts (∼1 μg) of purified GST fusion proteins bound to Sepharose beads were washed once in the corresponding 1× reaction buffer (as indicated for each kinase) and then phosphorylated in vitro in a 50-μl volume containing either CK1 (400 units; 50 mm Tris-HCl, 10 mm MgCl2, 5 mm dithiothreitol (DTT), pH 7.5), CK2 (100 units; 20 mm Tris-HCl, 50 mm KCl, 10 mm MgCl2, pH 7.5), or GRK2 (0.8 μg, 20 mm Tris-HCl, 10 mm MgCl2, 2 mm EDTA, 1 mm DTT, pH 8.0) plus 200 μm ATP and 1 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP and incubated at 30 °C for 20 min. The reactions were stopped by washing several times with ice-cold 0.5% Nonidet P-40 buffer. The phosphorylated proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and the radiolabeled protein bands were visualized using a PhosphorImager (Amersham Biosciences).

To assess the binding β-arrestin2 to NHE5, GST-NHE5 fusion proteins were phosphorylated in vitro using non-radiolabeled ATP (200 μm), and the phosphorylated proteins were then incubated overnight at 4 °C with either full-length radiolabeled β-Arr2myc that was transcribed and translated in vitro in the presence of [35S]methionine using the TNT® coupled reticulocyte lysate system (Promega) ([35S]β-Arr2myc; 2–3 μl of the TNT reaction mixture) or with CHO cell lysates (50 μg of protein/GST construct) prepared from cells that had been transiently transfected (24 h) with an expression plasmid containing β-Arr2myc (5 μg/10-cm dish; cells were lysed in 2 ml of PBS). After six washes with 0.5% Nonidet P-40 buffer, proteins were eluted in SDS sample buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 1% SDS, 50 mm dithiothreitol, 10% glycerol, and 0.1% bromphenol blue) and fractionated by SDS-PAGE. To measure binding of β-Arr2myc, the gels containing radiolabeled β-Arr2myc were dried, and the signals were detected using a PhosphorImager (Amersham Biosciences), whereas those containing non-radioactive β-Arr2myc were subject to immunoblotting with a monoclonal anti-myc antibody.

Phosphorylation in Intact Cells

Cells were grown to near confluence in 10-cm dishes. After 30 min of phosphate-free chasing, cells were labeled in vivo for 2 h at 37 °C in phosphate-free α-MEM containing 0.25 mCi/ml [32P]orthophosphate. Following extensive washes, cells were processed for immunoprecipitation by monoclonal anti-HA antibody as described below.

Measurement of Na+/H+ Exchanger Activity

NHE activity was assessed by radioisotopic flux methods. Briefly, AP-1 cells were grown to confluence in 24-well plates. Prior to 22Na+ influx, the cells were either at rest or acidified using the NH4Cl prepulse technique, as indicated (42). The assays were initiated by incubating the cell monolayers in isotonic choline chloride solution (125 mm choline chloride, 1 mm MgCl2, 2 mm CaCl2, 5 mm glucose, 20 mm HEPES-Tris, pH 7.4) containing 1 mm ouabain and carrier-free 22Na+ (1 μCi/ml) in the absence or presence of the NHE inhibitor amiloride (1 mm). The lack of K+ and the presence of ouabain minimized transport of Na+ catalyzed by the Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter and the Na+,K+-ATPase. The influx of 22Na+ was terminated by rapidly washing the cells three times with four volumes of ice-cold NaCl stop solution (130 mm NaCl, 1 mm MgCl2, 2 mm CaCl2, 20 mm HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.4). To extract the radiolabel, the monolayers were solubilized with 0.25 ml of 0.5 n NaOH, and the wells were washed with 0.25 ml of 0.5 n HCl. Both the NaOH cell extract and the HCl wash solution were combined in 5 ml of scintillation fluid and transferred to scintillation vials. The radioactivity was assayed by liquid scintillation spectroscopy. Protein content was determined using the Bio-Rad DC protein assay kit according to the manufacturer's protocol. Under these conditions, the uptake of 22Na+ at nominal Na+ concentrations was linear over a 10-min period at room temperature. Therefore, a time course of 5 min was chosen for the experiments. All experiments represent the average of three or four experiments, each performed in quadruplicate. The data are presented as the mean ± S.E.

Immunoprecipitation

AP-1 cells were transiently transfected with wild-type or mutant NHE5 (HA-tagged or untagged) constructs either singly or in combination with β-Arr2myc (or β-Arr2FLAG), CK2αHA, or CK2α′HA (DNA ratio of 1:1, 8 μg of DNA total). Following transfection (24 h), cells were lysed with ice-cold buffer (150 mm NaCl, 10 mm EDTA, 0.5% Triton X-100, 0.2% sodium deoxycholate, 20 mm Tris·HCl, pH 7.5, and protease inhibitors). For immunoprecipitation, cell lysates (∼250 μg of protein) were incubated with either rabbit polyclonal anti-HA (1:250 dilution) or NHE5 isoform-specific (anti-NHE5 #3568) antibodies (1:200 dilution) at 4 °C overnight, followed by incubation with protein G-Sepharose beads for 2 h. After washing the beads in buffer four times, immune complexes were eluted in 2× SDS sample buffer for 10 min at 55 °C and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. Membranes were blocked in PBS containing 5% nonfat milk for 1 h and then incubated with either the primary mouse monoclonal anti-HA antibody (1:2000 dilution), monoclonal anti-FLAG (1:5000 dilution), or polyclonal anti-NHE5 (1:2000) followed by the HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (1:5000 dilution) or anti-rabbit IgG-HRP (1:5000 dilution). The immunoreactive bands were visualized by an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Amersham Biosciences).

Measurement of Cell Surface Abundance of NHE5

AP-1 cells were cultured in 10-cm dishes to 50% confluence and then transiently cotransfected with a fixed amount (2 μg) of wild-type or mutant NHE5HA3 cDNAs and increasing amounts of β-Arr2myc (0–8 μg). In all cases, the total DNA/transfection was constant at 10 μg/dish by adjusting with empty parental vector pCMV. Following transfection (24 h), the cells were placed on ice and washed three times with ice-cold PBS buffer containing 0.1 mm CaCl2 and 1 mm MgCl2, pH 8.0 (PBS-CM). Plasma membrane proteins were isolated using a cell surface biotinylation assay as described previously (10, 43). Briefly, plasmalemmal proteins were indiscriminately labeled with membrane-impermeable N-hydroxysulfosuccinimydyl-SS-biotin (sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin (0.5 mg/ml); Pierce) for 30 min at 4 °C. The solution was then discarded, and unreacted biotin was quenched three times with ice-cold PBS-CM containing 20 mm glycine. The cells were then lysed in PBS buffer containing 0.2% deoxycholic acid, 0.5% Triton X-100, and proteinase inhibitor mixture for 30 min on ice and then centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C to remove insoluble cellular debris. A portion of the resulting supernatant was removed and represents the “total fraction.” The remaining supernatant was incubated overnight with streptavidin-Sepharose beads to extract biotinylated “surface membrane proteins” according to the manufacturer's instructions. The proteins were then resolved by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting. The intensities of the bands were quantified by densitometry of films exposed in the linear range and then digitally imaged and analyzed with the FluorChemTM system (Alpha Innotech Corp.).

Measurement of Rates of Endocytosis of NHE5 Variants

Internalization of plasmalemmal NHE5 as a function of time was measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (44). Briefly, HEK-293 GripTiteTM MSR cells were transfected at 50–60% confluence with expression plasmids containing wild-type or mutant NHE5FLAG3 variants and at 18–24 h post-transfection were transferred to fibronectin-coated (1 μg/ml) 12-well plates. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells (80% confluence) were washed with cold PBS-CM (pH 7.4) and blocked on ice in PBS-CM plus 10% goat serum for 30 min. Cells were incubated with an anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody (1:3000 dilution) on ice for 1 h, washed twice with PBS-CM to remove unbound antibody, and then incubated in serum-free culture medium (pH 7.4) for the indicated periods of time to allow endocytosis to proceed. Cells were then placed back on ice, washed three times with PBS-CM plus 10% goat serum, and incubated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:1000 dilution) for 1 h. After six washes with PBS-CM, HRP activity was measured using 10 mm Amplex Red in 1× reaction buffer (0.05 m NaH2PO4, pH 7.4, 20 mm H2O2) for 15 min at 4 °C, and the fluorescence intensity was determined by a POLARstar (BMG Labtech, Durham, NC) plate reader. Nonspecific binding of the antibodies was measured in mock-transfected cells. After two washes, cells were lysed in RIPA buffer, and protein concentrations were measured by a BCA assay. Specific signals were obtained by subtracting the nonspecific background fluorescence and then normalizing the signals to total cellular protein. Each experiment was repeated at least four times and performed in triplicate.

Statistical Analysis

Experiments were repeated at least three times or as indicated. Data are means ± S.E. Significance was calculated by using the two-tailed p value at a 95% confidence level with an unpaired t test.

RESULTS

Delineation of the β-Arrestin-binding Domain of NHE5

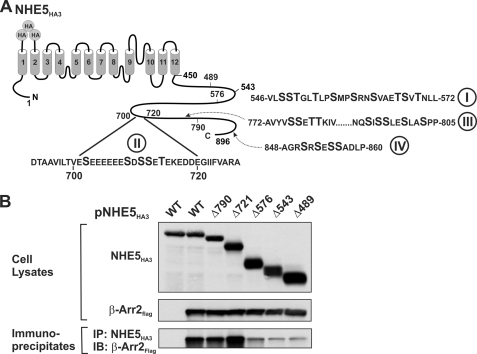

A large body of evidence has demonstrated that high affinity binding of β-arrestins to GPCRs involves multiple sites (phosphorylation-dependent Ser/Thr clusters and phosphorylation-independent motifs) within the cytoplasmic C terminus and/or third intracellular loop of the receptors (20, 22, 45). Examination of the primary structure of NHE5 reveals several Ser/Thr clusters within its cytoplasmic C terminus that could serve as potential phospho-recognition sites for β-arrestins (shown in Fig. 1A). To delimit potential elements within this region that are crucial for β-arrestin binding, several sequential C-terminal truncation mutations of an external triple HA epitope-tagged form of NHE5 (NHE5HA3-Δ790, -Δ721, -Δ576, -Δ543, and -Δ489) were constructed and then tested for their ability to bind a FLAG epitope-tagged construct of β-arrestin2 (β-Arr2FLAG) in transiently cotransfected CHO cells. Following 48 h of transfection, cell lysates were prepared and then incubated with a polyclonal anti-HA antibody to immunoprecipitate NHE5HA3. The resultant protein complexes were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. As illustrated in Fig. 1B, all of the NHE5HA3 constructs and β-Arr2FLAG were well expressed in the transfected cells. Examination of the immunoprecipitates showed that the bulk of β-Arr2FLAG binding was lost upon truncation at position amino acid 576, suggesting that the region between residues 576 and 721 is important for interaction with β-Arr2FLAG. However, even the NHE5-Δ489 mutant that lacked almost the entire C terminus retained some residual binding of β-Arr2FLAG. This could represent nonspecific binding or, alternatively, might reflect low affinity binding to the remaining C terminus and/or intracellular loops of NHE5HA3. As a negative control, a signal for β-Arr2FLAG was not detected in transfected cells expressing only NHE5HA3.

FIGURE 1.

Delineation of the β-arrestin2-binding domain in the C terminus of NHE5. A, schematic representation of the topological organization of NHE5 and locations of clusters of putative Ser/Thr phosphoacceptor sites in its cytoplasmic C terminus. B, full-length and C-terminal truncations of NHE5HA3 were transiently co-transfected with β-Arr2FLAG in CHO cells. NHE5HA3 was immunoprecipitated (IP) with a monoclonal anti-HA antibody, and the immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting (IB) with a polyclonal anti-FLAG antibody to detect β-Arr2FLAG. Data shown are representative of at least three independent experiments.

Identification of the β-Arrestin Recognition Motif and Role of Phosphorylation

Within the region between 576 and 721, one sequence that had the potential to confer responsiveness to β-Arr2 was a highly acidic Ser/Thr-rich cluster (692DTAAVILTVESEEEEEESDSSETEKEDDEGIIFVARA728). This negatively charged region, which is relatively unique among the NHE isoforms, contains multiple serine and threonine residues that could be potential targets of the acidotropic protein kinases CK1 and CK2, which, despite sharing the same nomenclature, are structurally unrelated and recognize subtly distinct canonical sequences (46–49). Aside from CK1 and CK2, this sequence could also be a target for G protein-coupled receptor kinases (GRKs), which do not appear to recognize a specific consensus motif, but mutagenesis and phosphorylation studies using synthetic peptides have revealed that they display a preference for pairs of acidic amino acids in proximity to three or four phosphorylatable Ser/Thr residues (50–54).

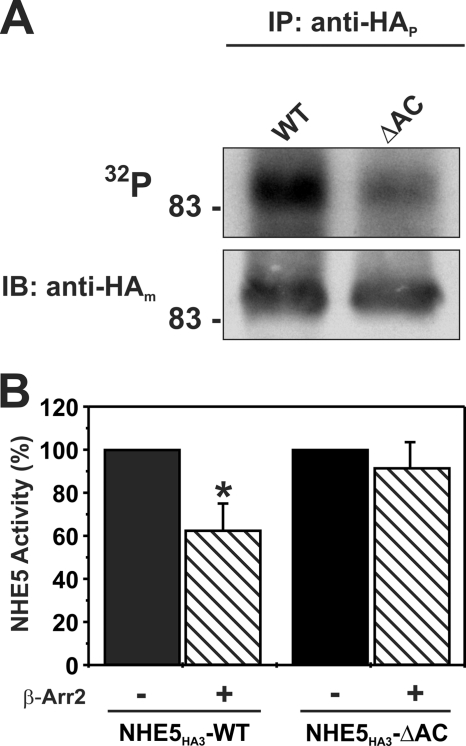

The potential relevance of this acidic Ser/Thr motif to the phosphorylation status of the full-length exchanger was evaluated by creating an NHE5HA3 deletion mutant lacking the acidic Ser/Thr-rich cluster encompassing residues 700–720 (NHE5HA3-ΔAC), followed by metabolic labeling with [32P]orthophosphate in transfected AP-1 cells, a CHO-derived cell line that lacks endogenous NHE activity at its cell surface. As shown in Fig. 2, the amount of 32P incorporated into the ΔAC mutant was significantly reduced compared with wild type (WT), suggesting that this motif is constitutively phosphorylated in intact AP-1 cells. Although it is possible that the deletion mutation caused secondary conformational changes in the protein that attenuated basal phosphorylation at more distal sites, the simplest interpretation is that this motif contains one or more sites for phosphorylation by Ser/Thr kinases. To determine whether the deletion of the acidic cluster had any functional consequences, AP-1 cells were transiently cotransfected with the NHE5 WT or ΔAC mutant in the absence or presence of β-Arr2 and then assayed 24 h later for plasmalemmal NHE5 activity as described previously (10). As shown in Fig. 2B, overexpression of β-Arr2 significantly decreased WT NHE5 activity by ∼40% but had little effect on the ΔAC mutant. These data are suggestive of an important role for the acidic Ser/Thr cluster in β-Arr2-mediated down-regulation of cell surface NHE5 activity.

FIGURE 2.

An acidic Ser/Thr cluster in NHE5 confers responsiveness to β-Arr2 in intact cells. A, AP-1 cells stably expressing WT or mutant NHE5HA3 lacking the acidic cluster (amino acids 700–720; ΔAC) were metabolically labeled with [32P]orthophosphate, immunoprecipitated (IP) with a rabbit polyclonal anti-HA antibody (anti-HAp), and separated by SDS-PAGE. A representative autoradiograph is shown (top). Whole cell extracts were blotted (IB) with a mouse monoclonal anti-HA antibody (anti-HAm) (bottom). B, AP-1 cells were transiently co-transfected with NHE5HA3 WT or NHE5HA3-AC and β-Arr2myc (1:2 DNA ratio), and plasmalemmal NHE5 activity was measured 24 h post-transfection as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Values are the means ± S.D. (error bars) of at least three or four independent experiments (*, p < 0.05).

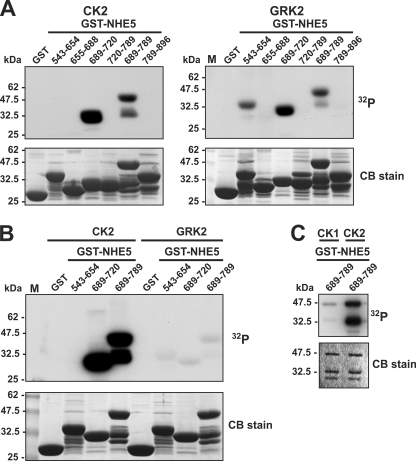

To further examine the potential of this motif to serve as a target for acidotropic protein kinases, recombinant GST fusion proteins containing segments of NHE5 that span almost its entire C terminus were tested for their ability to be phosphorylated in vitro by purified CK2 and GRK2 under optimal assay conditions for each kinase. The GRK2 isoform was chosen from among the GRK family members because it phosphorylates a wide variety of GPCRs and is particularly abundant in the brain, where NHE5 is expressed (18, 21). As shown in Fig. 3A, two overlapping fragments from the middle portion of the cytoplasmic tail embracing the acidic cluster (amino acids 689–720 and 689–789) were phosphorylated by both CK2 and GRK2. The larger GST-NHE5(689–789) fragment migrated as two phosphorylated bands; the size of the faster migrating band suggests that it most likely represents a GST-NHE5 proteolytic product that retains the phosphorylation site(s). In addition, GRK2 phosphorylated another unique site between amino acids 543–654. However, detection of the radioisotopic signals generated by GRK2 required considerably longer exposure times than those produced by CK2. When the signals of the various fragments generated by both kinases were compared on the same gel (Fig. 3B), those catalyzed by CK2 were far more intense than those produced by GRK2. Likewise, GST-NHE5(689–789) was preferentially phosphorylated by CK2 relative to CK1 (Fig. 3C), further highlighting the relative specificity of this phosphoacceptor site for CK2.

FIGURE 3.

Comparison of in vitro phosphorylation of C-terminal segments of NHE5 by protein kinases CK1, CK2 and GRK2. A–C, purified GST and GST-NHE5 fusion proteins encoding peptide segments that span the cytoplasmic C terminus of NHE5 were incubated in vitro with 200 μm ATP and 1 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP and purified protein kinase CK1, CK2, or GRK2 as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The proteins in the reaction solution were resolved by SDS-PAGE. Radioactivity was detected using a PhosphorImager, and protein loading was visualized by staining with Coomassie Blue (CB) dye. Data shown are representative of at least three independent experiments.

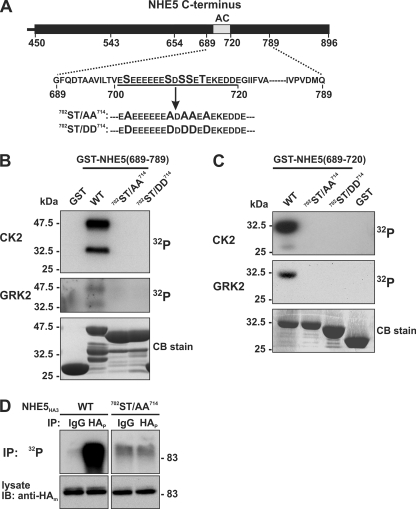

Because this sequence contains multiple Ser and Thr residues that could be potential phosphoacceptor sites for CK2, five Ser/Thr residues within the acidic cluster (Ser702, Ser709, Ser711, Ser712, and Thr714) were mutated simultaneously to either Ala (702ST/AA714) or Asp (702ST/DD714); these substitutions are predicted to imitate the dephosphorylated and phosphorylated states of the signal, respectively (shown in Fig. 4A). As expected, these mutations completely blocked phosphorylation of the larger GST-NHE5(689–789) (Fig. 4B) as well as the smaller GST-NHE5(689–720) (Fig. 4C) construct by CK2 and GRK2, indicating that both kinases phosphorylate one or more residues within this motif. Similar results were also obtained for CK1 (data not shown). The significance of these Ser/Thr residues as phosphoacceptor sites was further examined in the full-length NHE5 WT and mutant (702ST/AA714) transporter transfected into intact AP-1 cells. As shown in Fig. 4D, the amount of 32P incorporated into the NHE5HA3-702ST/AA714 mutant was dramatically reduced compared with WT, corroborating prior findings (Fig. 2A) that this motif is constitutively phosphorylated in whole cells.

FIGURE 4.

Mutation of the acidic cluster abolishes NHE5 phosphorylation in vitro and in intact cells. A, schematic representation of the Ser and Thr residues in the acidic cluster (AC) that were mutated to either Ala (ST/AA) or Asp (ST/DD). B and C, purified GST-NHE5 fusion proteins containing amino acids 689–789 (B) or 689–720 (C) were phosphorylated in vitro by purified CK2 or GRK2 in the presence of 200 μm ATP and 1 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The reaction mixtures were fractionated by SDS-PAGE, and radioactivity and protein levels were detected using a PhosphorImager and Coomassie Blue (CB) dye, respectively. D, AP-1 cells stably expressing full-length NHE5HA3 WT or 702ST/AA714 mutant were metabolically labeled with [32P]orthophosphate, immunoprecipitated (IP) with control rabbit serum IgG or with a rabbit polyclonal anti-HA antibody (anti-HAp), and separated by SDS-PAGE. A representative autoradiograph is shown (top). Whole cell extracts were blotted (IB) with a mouse monoclonal anti-HA antibody (anti-HAm) (bottom). Data shown are representative of at least three independent experiments.

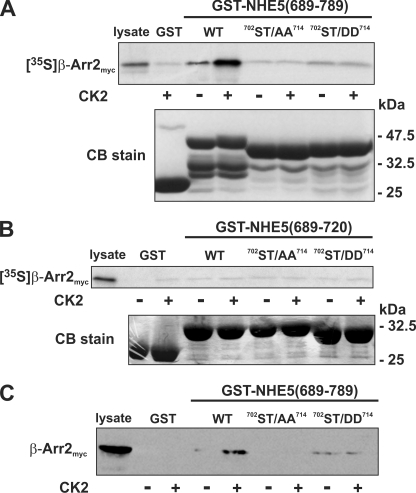

To assess the relevance of phosphorylation of the NHE5 C terminus in relation to β-Arr2 binding, in vitro protein binding pull-down assays were performed. Recombinant GST fusion proteins containing WT or mutant (702ST/AA714 and 702ST/DD714) NHE5(689–789) fragments were either untreated or phosphorylated in vitro by the more potent kinase CK2 and then incubated with 35S-radiolabeled β-Arr2 protein synthesized using rabbit reticulocyte lysates. Complexes of GST-NHE5(689–789) and [35S]β-Arr2 were purified, subjected to SDS-PAGE, and analyzed using a PhosphorImager. As shown in Fig. 5A, whereas [35S]β-Arr2 bound to a minor extent to unphosphorylated wild-type GST-NHE5(689–789) compared with GST alone, its association was significantly enhanced upon CK2 phosphorylation of GST-NHE5(689–789). By contrast, the 702ST/AA714 mutant showed negligible binding in the absence or presence of CK2. Likewise, the binding of β-Arr2 to the 702ST/DD714 mutant was unchanged upon CK2 treatment, although the observed binding in the absence or presence of CK2 appeared slightly higher than that of either GST alone or the 702ST/AA714 mutant but well below levels obtained for CK2-phosphorylated wild-type GST-NHE5(689–789). Interestingly, the smaller GST-NHE5(689–720) fusion protein containing just the acidic cluster was unable to bind [35S]β-Arr2 regardless of its state of phosphorylation (Fig. 5B), suggesting that sequences flanking the phospho-recognition site are also required for high affinity binding of β-Arr2.

FIGURE 5.

Role of phosphorylation in the in vitro binding of β-arrestin2 to the C terminus of NHE5. A–C, purified WT and mutant (ST/AA and ST/DD) constructs of GST-NHE5(689–789) (A and C) and GST-NHE5(689–720) (B) were preincubated in the absence or presence of purified CK2 and ATP (200 μm). The GST-NHE5 fusion proteins were then incubated in the presence of in vitro synthesized 35S-labeled β-Arr2myc (A and B) or CHO cell lysates containing β-Arr2myc (C). The GST complexes were purified using glutathione-agarose beads and resolved by SDS-PAGE. To measure binding of β-Arr2myc, the gels containing radiolabeled β-Arr2myc were dried, and the signals were detected using a PhosphorImager, whereas those containing non-radioactive β-Arr2myc were subject to immunoblotting. Parallel gels were stained with Coomassie Blue (CB) dye to assess protein loading. Data shown are representative of at least three independent experiments.

A caveat to the above findings is that β-Arr2 was synthesized in vitro, and its conformational state(s) and binding capabilities under these conditions might not faithfully mimic those that occur in whole cells. As well, β-Arr2 is subject to covalent modifications, such as phosphorylation (55, 56) and ubiquitination (57–59), although these alterations do not seem to affect the affinity of β-Arr2 for GPCRs but rather to regulate subsequent downstream events. Whether such posttranslational modifications influence the formation of a NHE5·β-Arr2 complex is unknown. Hence, to further validate the binding results obtained with in vitro synthesized [35S]β-Arr2 protein, we repeated the pull-down assay of the different GST-NHE5(689–789) constructs by incubating them with whole cell lysates of transfected CHO cells expressing a myc-tagged form of β-Arr2 (β-Arr2myc). Consistent with our previous findings, CK2 phosphorylation of wild-type GST-NHE5(689–789) significantly increased the binding of β-Arr2myc, whereas the interaction was not detected with the 702ST/AA714 mutant (Fig. 5C). Similarly, β-Arr2myc bound constitutively to the 702ST/DD714 mutant but only to a minimal extent. Although GRK2 and CK1 were able to weakly phosphorylate the same acidic Ser/Thr cluster (see Fig. 3), we were unable to detect significant binding of β-Arr2 under these conditions (data not shown).

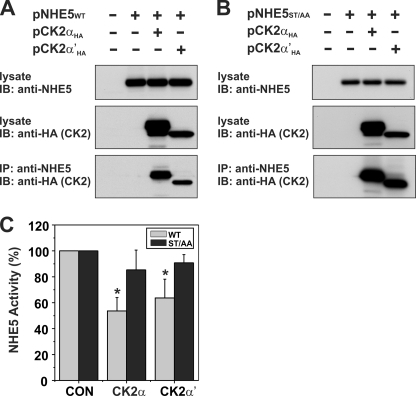

Given the relative avidity of NHE5 for phosphorylation by CK2 in vitro, we next explored whether NHE5 and CK2 could also physically associate in intact cells. To this end, AP-1 cells were transiently transfected with untagged WT or 702ST/AA714 mutant forms of NHE5, either alone or in combination with HA-tagged constructs of the catalytic α or α′ subunits of CK2, two closely related isoforms that are encoded by different genes but have very similar catalytic properties (60). As shown in Fig. 6, both CK2αHA and CK2α′HA were detected in immunoprecipitates of NHE5 WT (Fig. 6A) or 702ST/AA714 mutant (Fig. 6B) proteins produced with a rabbit polyclonal antibody that specifically recognizes a unique epitope within the C terminus (residues 789–896) of NHE5. Likewise, in the reciprocal experiment, NHE5 WT and 702ST/AA714 mutant proteins were detected in anti-HA generated immunoprecipitates of both CK2αHA and CK2α′HA (supplemental Fig. 1). These data indicate that NHE5 and CK2 can form a macromolecular complex in whole cells but that their association is not dependent on an intact phosphorylatable acidic Ser/Thr motif. To determine whether overexpression of CK2αHA and CK2α′HA had any functional consequences, AP-1 cells were transiently cotransfected with the NHE5 WT or 702ST/AA714 mutant and then assayed 48 h later for plasmalemmal NHE5 activity. Preliminary experiments demonstrated that the ST/AA mutation had no discernible effect on the H+ affinity of the transporter (supplemental Fig. 2). As shown in Fig. 6C, overexpression of CK2αHA and CK2α′HA significantly decreased the activity of NHE5 WT by ∼40% but had only a marginal effect on NHE5-702ST/AA714. Collectively, these data support a role for CK2 in phosphorylation and down-regulation of NHE5.

FIGURE 6.

Catalytic α/α′ subunits of protein kinase CK2 form a complex with NHE5 and regulate its activity. Full-length NHE5 WT (A) and mutant (ST/AA) (B) constructs were transiently transfected alone or together with CK2αHA or CK2α′HA in Chinese hamster ovary AP-1 cells. Cells were lysed after 24 h of transfection. Aliquots of the lysates were removed for Western blot analysis of total cellular expression of NHE5 and CK2αHA or CK2α′HA, whereas the remainder was incubated with a rabbit polyclonal anti-NHE5 antibody to precipitate NHE5-containing protein complexes. The immunoprecipitates (IP) were fractionated by SDS-PAGE, followed by immunoblotting (IB) with a monoclonal anti-HA antibody to detect CK2αHA or CK2α′HA. C, AP-1 cells stably expressing NHE5WT or NHE5ST/AA were transiently transfected with CK2αHA or CK2α′HA. Twenty-four h post-transfection, plasmalemmal NHE5 activity was measured as the rate of amiloride-inhibitable, H+-activated 22Na+ influx, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Values are the means ± S.D. (error bars) of four independent experiments (*, p < 0.05).

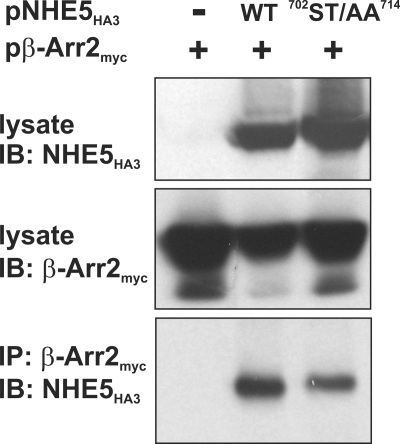

To further examine the importance of the acidic Ser/Thr-rich cluster in the binding of β-Arr2 in intact cells, full-length WT and 702ST/AA714 mutant NHE5HA3 were transiently cotransfected with β-Arr2myc into CHO cells. As expected, β-Arr2myc formed an immunoprecipitable complex with NHE5HA3 WT, but, contrary to the in vitro analyses, β-Arr2myc also interacted with the 702ST/AA714 mutant transporter (Fig. 7). Thus, other regions of NHE5 most likely contribute to high affinity binding of β-Arr2. This inference would be consistent with data presented in Fig. 1, where minor binding of β-Arr2 was retained in the NHE5 mutant lacking almost the entire cytoplasmic C terminus, and with results shown in Fig. 5, where the minimal acidic phospho-Ser/Thr segment (residues 689–720) alone was not sufficient for β-Arr2 binding.

FIGURE 7.

β-Arrestin2 forms a complex with wild-type and ST/AA mutant NHE5 in transfected cells. Chinese hamster ovary AP-1 cells were transiently transfected with expression plasmids containing β-Arr2myc alone or in combination with WT or mutant (ST/AA) NHE5HA3. After 24 h of transfection, cells were lysed, and β-Arr2myc was immunoprecipitated (IP) using a polyclonal anti-myc antibody. The immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting (IB) with a monoclonal anti-HA antibody.

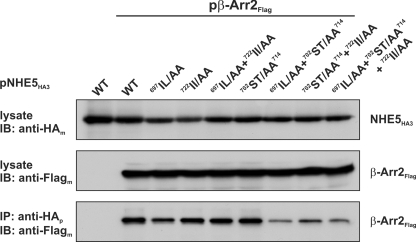

In consideration of the above results, we noted the presence of two di-isoleucine-based sequences (697IL and 722II) that immediately flank the acidic sequence (see Fig. 1). Earlier studies have delineated a significant role for dihydrophobic motifs in the internalization of various agonist-activated GPCRs (61–64). Hence, to examine possible contributions of either of these di-isoleucine sequences to the binding of β-Arr2, each pair was mutated to alanine residues (697IL/AA and 722II/AA), either separately or in combination, in both the NHE5HA3 WT and 702ST/AA714 mutant. These constructs were then co-expressed transiently with β-Arr2FLAG in CHO cells and assessed for their ability to form an immunoprecipitable protein complex. As shown in Fig. 8, all of the mutants were expressed to comparable levels. The association of β-Arr2FLAG with NHE5HA3 was not noticeably affected by mutations to the proximal or distal di-isoleucine sequences, either individually or jointly, but was dramatically reduced (>70%) when combined with the 702ST/AA714 mutation. These data suggest that these di-isoleucine motifs, although not essential for β-Arr2 binding, are nevertheless important elements of a longer β-Arr2 recognition motif in full-length NHE5 when expressed in intact cells.

FIGURE 8.

Role of di-isoleucine motifs in β-Arr2 binding to NHE5. Chinese hamster ovary AP-1 cells were transiently cotransfected with expression plasmids containing β-Arr2FLAG or empty vector combined with WT or mutant variants of NHE5HA3. After transfection (24 h), cells were lysed, and aliquots were removed for Western blot analysis of total cellular expression of NHE5HA3 and β-Arr2FLAG. The remainder of the lysates were incubated with a rabbit polyclonal anti-HA antibody to precipitate NHE5-containing protein complexes. The immunoprecipitates (IP) were resolved by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting (IB) with a monoclonal anti-FLAG antibody. Data shown are representative of at least three separate experiments.

Although the above experiments showed that NHE5 can form complexes with CK2 and β-Arr2 in intact cells, they were reliant on transient overexpression assays, which may not necessarily reflect conditions in native tissues. Unfortunately, established neuronal cell lines that endogenously express all three proteins have yet to be identified, and attempts to immunoprecipitate these complexes from whole brain lysates were not informative due to high background signals. Hence, to simulate a more native environment, we generated an AP-1 cell line that stably expresses NHE5HA3 at levels comparable with that found in whole human brain lysates and then assessed the ability of NHE5HA3 to form a complex with endogenous CK2 and β-arrestins. As demonstrated in supplemental Fig. 3, anti-HA immunoprecipitates of exogenous NHE5HA3 contained both CK2α and β-Arr2. This finding provides further support for the biological veracity of these interactions.

Assessment of the β-Arrestin-binding Motif in Promoting Endocytosis of NHE5

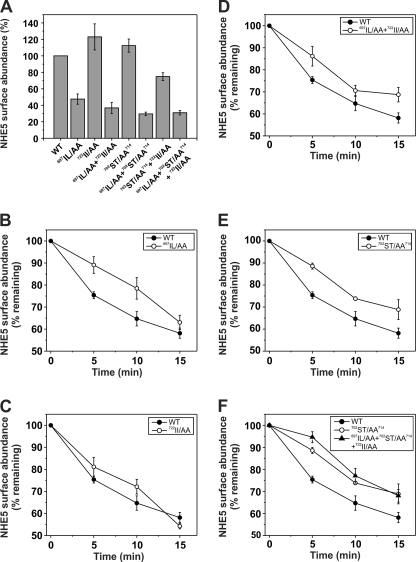

To evaluate the functional relevance of the acidic Ser/Thr di-isoleucine motif in regulating the trafficking of NHE5, the rates of endocytosis of wild-type and mutant NHE5 constructs were quantified by an ELISA using an antibody against the extracellular epitope tag on the transporter. Preliminary studies were performed in transiently transfected AP-1 cells, but the resulting signals were extremely low (signal/noise ratio of ∼2:1) due to low transfection efficiency (∼30–40%). Hence, for these experiments, we used GripTiteTM 293 MSR cells, a subclone of human HEK-293 cells that exhibits a much higher transfection efficiency (>90%) and has the additional advantage of adhering very strongly to tissue culture plates, which minimizes uncontrolled cell loss that can occur following repeated cell washes during the assay procedure. Detection sensitivity was further enhanced by replacing the external triple HA epitope in NHE5 with a triple FLAG tag. Replacement of the HA epitope with the FLAG sequence did not affect the total cellular expression of the various NHE5 constructs (data not shown). Under these conditions, the ability to detect cell surface NHE5FLAG3 was greatly enhanced (signal/noise ratio of ∼10:1). As shown in Fig. 9A, the cell surface densities of NHE5FLAG3 variants containing the 702ST/AA714 or 722II/AA mutations were slightly higher than wild type, although this effect was not additive. By contrast, variants containing the 697IL/AA mutation showed noticeably reduced surface abundance (∼30–40% of control).

FIGURE 9.

Measurement of cell surface abundance and rates of endocytosis of wild-type and mutant variants of NHE5. Cell surface abundance (A) and internalization of plasmalemmal wild-type and mutant variants of NHE5FLAG3 (B–F) as a function of time were measured using an ELISA as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The turnover of plasma membrane NHE5FLAG3 was monitored by the disappearance of cell surface bound anti-FLAG antibody in transiently transfected HEK-293 GripTiteTM MSR cells. Briefly, cells were labeled with a monoclonal anti-FLAG antibody on ice for 1 h and then chased over a 15-min period at 37 °C. The anti-FLAG antibody remaining at the cell surface was measured by fluorescence in the presence of a mouse HRP-conjugated secondary antibody and Amplex Red, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The fluorescence was normalized for cellular proteins. The values are expressed as a percentage of the initial amount of NHE5 at the cell surface at time 0 min and represent the mean ± S.E. (error bars) of 4–6 independent experiments.

To measure rates of internalization of the NHE5FLAG3 variants, surface transporters were marked with the primary mouse monoclonal anti-FLAG antibody on ice for 1 h, followed by various chase times extending over 15 min at 37 °C to allow endocytosis to proceed. Cells were then placed on ice, washed, and incubated with the secondary HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody for 1 h to detect the amount of anti-FLAG-labeled NHE5FLAG3 remaining at the surface. As shown in Fig. 9, the initial rates of endocytosis of 697IL/AA (Fig. 9B) and 702ST/AA714 (Fig. 9E) were reduced to similar extents (∼60%) relative to WT, whereas the distal 722II/AA mutant was only marginally affected (Fig. 9C). Rates of internalization of the double mutants 697IL/AA + 722II/AA (Fig. 9D), 697IL/AA + 702ST/AA714, and 702ST/AA714 + 722II/AA (data not shown) were similar to each other and to the rates observed for the individual 697IL/AA and 702ST/AA714 mutants, whereas internalization of the triple mutant (697IL/AA + 702ST/AA714 + 722II/AA) was slightly more attenuated (Fig. 9F). Thus, mutations to different segments of the β-Arr2 recognition site, notably the proximal di-isoleucine and central Ser/Thr amino acids, significantly decreased the rates of endocytosis of NHE5FLAG3. Control experiments indicated that the addition of the primary anti-FLAG antibody did not impair the catalytic activity of NHE5 (data not shown).

Although the above mutagenesis analyses clearly revealed an important role for the acidic Ser/Thr di-isoleucine motif in the internalization of NHE5, the causal linkage to β-arrestin binding in intact cells appeared less certain because the impaired internalization of some mutants, such as 702ST/AA714, did not strictly correlate with the loss of β-Arr2 binding to NHE5. This result could be explained by a reduction in the affinity of β-Arr2 for the same site in the 702ST/AA714 mutant or perhaps by low affinity binding to an alternate site that, in either case, was sufficient to maintain a physical association but not strong enough to optimally activate and engage β-Arr2 in recruitment of the endocytic machinery. Hence, to further establish a functional relationship between the acidic Ser/Thr di-isoleucine motif and β-arrestin-mediated endocytosis, we examined whether mutations of this site altered the cell surface density of NHE5 as a function of β-Arr2 overexpression. To this end, AP-1 cells were transiently cotransfected (48 h) with a fixed amount of DNA containing different NHE5HA3 constructs (WT, 702ST/AA714, or 697IL/AA + 702ST/AA714 + 722II/AA) in the presence of increasing amounts of β-Arr2FLAG, and the steady-state abundance of plasmalemmal NHE5HA3 was measured using a cell surface biotinylation assay as described previously (10). As illustrated in Fig. 10A, the levels of wild-type NHE5HA3 at the cell surface relative to its total cellular expression decreased significantly as a function of increasing levels of β-Arr2FLAG. Quantitation of the band intensities of surface to total NHE5HA3 showed a maximal decrease of ∼40% (Fig. 10B), consistent with earlier findings (10). Significantly, this down-regulation was noticeably diminished for the 702ST/AA714 mutant (maximal decrease of ∼20%) and abolished for the 697IL/AA + 702ST/AA714 + 722II/AA mutant. Thus, these data support a role for the acidic Ser/Thr-rich di-isoleucine motif in β-arrestin2-mediated endocytosis of NHE5.

FIGURE 10.

Phosphorylation of the C-terminal acidic Ser/Thr cluster is important for β-arrestin2-mediated internalization of NHE5. A, AP-1 cells in 10-cm dishes were transiently cotransfected (24 h) with 10 μg of cDNA containing a fixed amount (2 μg) of WT or mutant (702ST/AA714 or 697IL/AA + 702ST/AA714 + 722II/AA) NHE5HA3 and increasing amounts (0–8 μg) of β-Arr2FLAG. The total DNA/transfection was held constant at 10 μg/dish by adjusting with empty parental vector pCMV. Cell surface NHE5 protein was isolated using a cell surface biotinylation assay (see “Experimental Procedures”) and compared with total cellular levels of NHE5 (10% of lysate). The fractions were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted using antibodies to the respective epitope tags, and the intensities of the bands were quantified by densitometry. B, for comparative purposes, the ratio of surface/total NHE5 for cells expressing NHE5HA alone (control) was normalized to a value of 1. Values are the means ± S.E. (error bars) of at least four independent experiments (*, p < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

Previous studies revealed an unexpected role for the specialized GPCR endocytic adaptors β-arrestin1/2 in promoting the internalization of the pH-regulating transporter NHE5 (10). The dissimilarity in structure and function between GPCRs and NHE5 prompted us to investigate the underlying molecular basis for the unusual association of NHE5 with β-arrestins, using the β-Arr2 isoform as a prototype for study.

Using deletion and site-directed mutagenesis in combination with biochemical and immunological assays conducted in vitro and in whole cells, we have identified an elaborate 27-amino acid sorting signal (692DTAAVILTVESEEEEEESDSSETEKEDDEGIIFVARA728) in the cytoplasmic C terminus of NHE5 that confers sensitivity to β-arrestins. Internal deletion of the acidic Ser/Thr segment (Δ700–720) abolished NHE5 responsiveness to β-Arr2 overexpression and correlated with a reduction in basal phosphorylation of the exchanger, suggesting that this interaction might be regulated by kinases.

Examination of this signal revealed the presence of putative elements that conform to minimal consensus sequences for different protein kinases, notably the acidotropic kinases CK1 and CK2, and possibly members of the G protein-coupled receptor kinase family, such as GRK2. This observation was enticing because all three kinases are known to directly phosphorylate and regulate one or more aspects of GPCR function (i.e. desensitization, internalization, and/or signaling) (22, 31, 32, 65). Further testing using in vitro kinase assays demonstrated that only C-terminal segments containing the acidic Ser/Thr cluster served as preferred substrates for robust phosphorylation by CK2, whereas the phosphosignals generated by CK1 or GRK2 were considerably less intense, at least in vitro. GRK2 was also able to weakly phosphorylate another unique segment within the C terminus of NHE5 (amino acids 543–654), although the functional significance of this covalent modification was not explored further in this study. Interestingly, CK2 and GRK2 have also been found to phosphorylate the same or overlapping sites within the thyrotropin-releasing hormone receptor (31, 66), although their relative potencies and functional effects were not directly compared.

One of the interesting properties of CK2 is that it can operate in a hierarchical fashion by phosphorylating one site that, in turn, creates a new site for subsequent phosphorylation by either itself or another kinase (48). With regard to the thyrotropin-releasing hormone receptor, CK2 was found to phosphorylate three neighboring sites in its C terminus, and mutation of all three sites was required to block phosphorylation and β-arrestin-dependent endocytosis (31). Likewise, multiple rather than single phosphoacceptor sites are required for GRK regulation of other GPCRs (50, 67–69). Hence, to further validate a role for CK2, we mutated five of the hydroxyl residues (i.e. Ser702, Ser709, Ser711, Ser712, and Thr714) in tandem within the acidic cluster to either Ala (702ST/AA714) or Asp (702ST/DD714); the latter substitution was chosen to serve as a potential phosphomimetic to create a constitutively active recognition site. Both cluster mutations effectively blocked phosphorylation by CK2. Interestingly, these substitutions also eliminated weak phosphorylation by GRK2, suggesting that both kinases may phosphorylate identical or possibly overlapping sites. However, more significantly, CK2-mediated phosphorylation of the GST-NHE5(689–789) fragment enhanced the in vitro binding of β-Arr2, whereas this effect was not detected for the other kinases within the sensitivity limits of the assay. As anticipated, the 702ST/AA714 substitutions also effectively abolished CK2-mediated binding of β-Arr2. By comparison, the 702ST/DD714 phosphomimetic construct bound β-Arr2 constitutively. However, contrary to expectations, the levels were relatively minor and considerably less than that observed for the CK2-phosphorylated wild type. One interpretation of this result is that the introduction of five additional negatively charged residues did not faithfully mimic the native phosphorylated state of this signal, thereby hindering optimal interactions with β-Arr2. By inference, this suggests that perhaps only a subset of the Ser/Thr amino acids are phosphorylated and required for recognition by β-Arr2. More extensive analyses will be required to delineate the precise arrangement of CK2 phosphoacceptor sites.

A biologically relevant role for CK2 in the internalization of NHE5 was further established in intact cells. CK2 is thought to exit largely as a tetrameric complex composed of two catalytic α subunits (α and/or α′ isoforms) and two regulatory β subunits and, although subject to intricate regulation, displays high constitutive activity (70, 71). However, additional evidence indicates that the holoenzyme is a highly dynamic and transient structure and that the catalytic α/α′ subunits are active irrespective of their association with the regulatory β subunits (72–75). To exploit this feature, full-length wild-type and 702ST/AA714 mutant NHE5 were transiently co-expressed with either CK2α or CK2α′ in AP-1 cells. Interestingly, both catalytic subunits formed an immunoprecipitable complex with either wild-type or 702ST/AA714 NHE5, suggesting that the kinase associates with the exchanger at a site (direct or indirect) that is distinct from the phosphoacceptor sites. Significantly, CK2 overexpression down-regulated (∼40%) the activity of wild-type NHE5 but had a negligible effect on the phosphorylation-deficient 702ST/AA714 mutant, supporting an important functional role for CK2. The lack of responsiveness of the 702ST/AA714 mutant to CK2 also correlated with a marked reduction in its constitutive rate of endocytosis and its relative insensitivity to overexpression of β-Arr2 compared with wild type. Together, these data are consistent with a direct regulatory role for CK2 in modulating the endocytosis of NHE5. Furthermore, the high constitutive activity of CK2 could account for the apparent steady association between NHE5 and β-Arr2, at least in transfected cell systems.

The indication that CK2 is a major kinase responsible for regulating β-arrestin-mediated internalization of NHE5 is appealing not only because of its aforementioned analogous role in the phosphorylation and internalization of the thyrotropin-releasing hormone receptor (31) but also because it has been implicated in the endocytosis of other non-GPCR cargo, including the transferrin receptor (76), the membrane endoprotease furin (77), and the L1 cell adhesion molecule (78). Interestingly, CK2 has also been shown to regulate the cell surface abundance of the epithelial Na+/H+ exchanger NHE3 isoform, although in this instance, direct phosphorylation of the transporter selectively increased its insertion into the plasma membrane without affecting its rate of internalization (79). Aside from cargo, CK2 also phosphorylates numerous ancillary proteins associated with clathrin-coated vesicles (80, 81), including β-Arr2 (55, 56). The consequences on β-Arr2 function, however, are controversial and not fully resolved. Notwithstanding, together these observations support an increasingly significant role for CK2 in the cycling dynamics of clathrin-associated cargo and endocytic machinery.

Intriguingly, despite the diminished responsiveness of the full-length, phosphorylation-deficient NHE5-702ST/AA714 mutant to β-Arr2 overexpression in intact cells, it retained its ability to assemble with β-Arr2; a result that was not obtained in the in vitro protein pull-down assays using the smaller isolated NHE5(689–789)-702ST/AA714 fragment. Indeed, weak binding of β-Arr2 was also detected when almost the entire C terminus of NHE5 was removed. Conversely, the smaller NHE5(689–720) fragment containing mainly the acidic Ser/Thr cluster, although readily phosphorylated by CK2, was unable to bind β-Arr2. These data suggest that neighboring and possibly more distal sequences contribute to stable NHE5-β-Arr2 interactions but that the phosphoacceptor sites in the acidic cluster, although important for β-Arr2-directed internalization, are neither obligatory nor sufficient for β-Arr2 binding. This pattern is compatible with the known heterogeneity of different GPCR-β-arrestin interactions that involve different domains of the receptor (multiple phosphorylation-dependent and -independent sites) as well as the adaptor to effect one or more steps of the receptor's biological cycle (20, 69, 82).

Consistent with the above notion, we discovered that two dihydrophobic motifs (697IL and 722II) that immediately border the acidic cluster are involved in β-Arr2 binding and internalization of NHE5. Double replacements of the di-Ile/Leu amino acids to Ala (697IL/AA or 722II/AA), when inserted either separately or together, did not disrupt the binding of β-Arr2. However, the NHE5-β-Arr2 interaction was largely abrogated when these mutations were combined with the phosphorylation-deficient 702ST/AA714 mutation. The minor residual binding was comparable with the truncated NHE5-Δ489 construct, which lacked the bulk of its C terminus. Significantly, the triple mutation (i.e. 697IL/AA + 702ST/AA714 + 722II/AA) was completely insensitive to overexpression of β-Arr2 and exhibited a slower initial rate of internalization compared with the 702ST/AA714 mutation alone. Interestingly, the individual dihydrophobic mutations, particularly the proximal 697IL/AA, also impaired endocytosis of NHE5 without disrupting the binding of β-Arr2. The presence of this mutation, either alone or in combination with other mutations of the acidic Ser/Thr di-isoleucine signal, also correlated with a marked reduction in cell surface abundance (determined by ELISA) of the transporter without affecting total cellular expression. This suggests that mutations to the 697IL motif may have an effect on endocytosis and/or exocytosis of NHE5 independent of its contributions to β-Arr2 binding. Indeed, the 697IL motif within the context of its surrounding amino acids (692DTAAVILTVESEE) exhibits similarity to classical acidic dileucine-based sorting signals (i.e. (D/E)XXXL(L/I)) (83–86) as well as more atypical acidic dileucine motifs (i.e. LLXXEE) (87), where the negatively charged amino acids are positioned downstream rather than upstream of the hydrophobic residues. Aside from dileucine signals, di-isoleucine motifs (i.e. II) have also been found to serve as unique signals for endocytosis (88, 89). Thus, our data suggest that phosphorylation of Ser/Thr clusters recognized by β-arrestins and acidic dihydrophobic signals, operating either independently or jointly, are involved in the endocytosis of NHE5. However, further studies will be required to finely dissect their relative contributions and underlying mechanisms. In this regard, such dual, often overlapping, pathways for internalization (i.e. phosphorylation/β-arrestin and dileucine signals) have also been reported for various agonist-activated GPCRs (61–64).

In conclusion, NHE5 contains an elaborate endocytic sorting signal composed of multiple elements that confer high affinity binding to β-arrestin2 and possibly other endocytic adapters that remain to be elucidated. Although the sequence of the motif is unusual, many of its features are reminiscent of the regulatory mechanisms that have been reported to underlie endocytosis of GPCRs.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported by Canadian Institutes for Health Research Grant MOP-11221 (to J. O.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1–3.

- NHE

- Na+/H+ exchanger

- β-Arr1 and β-Arr2

- β-arrestin1 and -2, respectively

- GPCR

- G protein-coupled receptor

- GRK

- G protein-coupled receptor kinase

- CK1

- protein kinase CK1

- CK2

- protein kinase CK2

- AP-1

- chemically mutagenized CHO cell line devoid of plasma membrane NHE activity

- α-MEM

- α-minimum essential medium

- 697IL/AA

- I697A/L698A

- 722II/AA

- I722A/I723A

- 702ST/AA714 and 702ST/DD714

- simultaneous mutation of five Ser/Thr residues within 702–714 to Ala and Asp, respectively.

REFERENCES

- 1. Brett C. L., Donowitz M., Rao R. (2005) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 288, C223–C239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Casey J. R., Grinstein S., Orlowski J. (2010) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 50–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wang D., King S. M., Quill T. A., Doolittle L. K., Garbers D. L. (2003) Nat. Cell Biol. 5, 1117–1122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wang D., Hu J., Bobulescu I. A., Quill T. A., McLeroy P., Moe O. W., Garbers D. L. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 9325–9330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bobulescu I. A., Moe O. W. (2006) Semin. Nephrol. 26, 334–344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Baird N. R., Orlowski J., Szabó E. Z., Zaun H. C., Schultheis P. J., Menon A. G., Shull G. E. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 4377–4382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Attaphitaya S., Park K., Melvin J. E. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 4383–4388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Szaszi K., Paulsen A., Szabo E. Z., Numata M., Grinstein S., Orlowski J. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 42623–42632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Diering G. H., Church J., Numata M. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 13892–13903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Szabó E. Z., Numata M., Lukashova V., Iannuzzi P., Orlowski J. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 2790–2795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pierce K. L., Premont R. T., Lefkowitz R. J. (2002) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3, 639–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lin F. T., Daaka Y., Lefkowitz R. J. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 31640–31643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chen W., Kirkbride K. C., How T., Nelson C. D., Mo J., Frederick J. P., Wang X. F., Lefkowitz R. J., Blobe G. C. (2003) Science 301, 1394–1397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wu J. H., Peppel K., Nelson C. D., Lin F. T., Kohout T. A., Miller W. E., Exum S. T., Freedman N. J. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 44238–44245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Puckerin A., Liu L., Permaul N., Carman P., Lee J., Diversé-Pierluissi M. A. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 31131–31141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lipsky R., Potts E. M., Tarzami S. T., Puckerin A. A., Stocks J., Schecter A. D., Sobie E. A., Akar F. G., Diversé-Pierluissi M. A. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 17221–17226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 17. Kimura T., Allen P. B., Nairn A. C., Caplan M. J. (2007) Mol. Biol. Cell 18, 4508–4518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Claing A., Laporte S. A., Caron M. G., Lefkowitz R. J. (2002) Prog. Neurobiol. 66, 61–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gainetdinov R. R., Premont R. T., Bohn L. M., Lefkowitz R. J., Caron M. G. (2004) Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 27, 107–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gurevich V. V., Gurevich E. V. (2006) Pharmacol. Ther. 110, 465–502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Premont R. T., Gainetdinov R. R. (2007) Annu. Rev. Physiol. 69, 511–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Moore C. A., Milano S. K., Benovic J. L. (2007) Annu. Rev. Physiol. 69, 451–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yuan N., Friedman J., Whaley B. S., Clark R. B. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 23032–23038 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Diviani D., Lattion A. L., Cotecchia S. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 28712–28719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liang M., Eason M. G., Jewell-Motz E. A., Williams M. A., Theiss C. T., Dorn G. W., 2nd, Liggett S. B. (1998) Mol. Pharmacol. 54, 44–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Namkung Y., Sibley D. R. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 49533–49541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mundell S. J., Jones M. L., Hardy A. R., Barton J. F., Beaucourt S. M., Conley P. B., Poole A. W. (2006) Mol. Pharmacol. 70, 1132–1142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tobin A. B., Totty N. F., Sterlin A. E., Nahorski S. R. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 20844–20849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Waugh M. G., Challiss R. A., Berstein G., Nahorski S. R., Tobin A. B. (1999) Biochem. J. 338, 175–183 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Budd D. C., McDonald J. E., Tobin A. B. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 19667–19675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hanyaloglu A. C., Vrecl M., Kroeger K. M., Miles L. E., Qian H., Thomas W. G., Eidne K. A. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 18066–18074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Torrecilla I., Spragg E. J., Poulin B., McWilliams P. J., Mistry S. C., Blaukat A., Tobin A. B. (2007) J. Cell Biol. 177, 127–137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mukherjee S., Gurevich V. V., Preninger A., Hamm H. E., Bader M. F., Fazleabas A. T., Birnbaumer L., Hunzicker-Dunn M. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 17916–17927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Min L., Galet C., Ascoli M. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 702–710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Richardson M. D., Balius A. M., Yamaguchi K., Freilich E. R., Barak L. S., Kwatra M. M. (2003) J. Neurochem. 84, 854–863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chen C. H., Paing M. M., Trejo J. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 10020–10031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Galliera E., Jala V. R., Trent J. O., Bonecchi R., Signorelli P., Lefkowitz R. J., Mantovani A., Locati M., Haribabu B. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 25590–25597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jala V. R., Shao W. H., Haribabu B. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 4880–4887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Penner C. G., Wang Z., Litchfield D. W. (1997) J. Cell. Biochem. 64, 525–537 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rotin D., Grinstein S. (1989) Am. J. Physiol. 257, C1158–C1165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Smith D. B., Corcoran L. M. (1994) in Current Protocols in Molecular Biology ((Ausubel F. M., Brent R., Kingston R. E., Moore D. D., Seidman J. G., Smith J. A., Struhl K. eds) pp. 16.7.1–16.7.7, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York [Google Scholar]

- 42. Szabó E. Z., Numata M., Shull G. E., Orlowski J. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 6302–6307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Le Bivic A., Real F. X., Rodriguez-Boulan E. (1989) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 86, 9313–9317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Barriere H., Nemes C., Lechardeur D., Khan-Mohammad M., Fruh K., Lukacs G. L. (2006) Traffic 7, 282–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Reiter E., Lefkowitz R. J. (2006) Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 17, 159–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Flotow H., Graves P. R., Wang A. Q., Fiol C. J., Roeske R. W., Roach P. J. (1990) J. Biol. Chem. 265, 14264–14269 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Flotow H., Roach P. J. (1991) J. Biol. Chem. 266, 3724–3727 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Meggio F., Pinna L. A. (2003) FASEB J. 17, 349–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Litchfield D. W. (2003) Biochem. J. 369, 1–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Fredericks Z. L., Pitcher J. A., Lefkowitz R. J. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 13796–13803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lee K. B., Ptasienski J. A., Bunemann M., Hosey M. M. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 35767–35777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Oakley R. H., Laporte S. A., Holt J. A., Barak L. S., Caron M. G. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 19452–19460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Pitcher J. A., Freedman N. J., Lefkowitz R. J. (1998) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67, 653–692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Vaughan D. J., Millman E. E., Godines V., Friedman J., Tran T. M., Dai W., Knoll B. J., Clark R. B., Moore R. H. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 7684–7692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kim Y. M., Barak L. S., Caron M. G., Benovic J. L. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 16837–16846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lin F. T., Chen W., Shenoy S., Cong M., Exum S. T., Lefkowitz R. J. (2002) Biochemistry 41, 10692–10699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Shenoy S. K., Lefkowitz R. J. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 14498–14506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Shenoy S. K., Lefkowitz R. J. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 15315–15324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Shenoy S. K., Barak L. S., Xiao K., Ahn S., Berthouze M., Shukla A. K., Luttrell L. M., Lefkowitz R. J. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 29549–29562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Litchfield D. W., Bosc D. G., Canton D. A., Saulnier R. B., Vilk G., Zhang C. (2001) Mol. Cell. Biochem. 227, 21–29 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Gabilondo A. M., Hegler J., Krasel C., Boivin-Jahns V., Hein L., Lohse M. J. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 12285–12290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Preisser L., Ancellin N., Michaelis L., Creminon C., Morel A., Corman B. (1999) FEBS Lett. 460, 303–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Orsini M. J., Parent J. L., Mundell S. J., Marchese A., Benovic J. L. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 31076–31086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Orsini M. J., Parent J. L., Mundell S. J., Marchese A., Benovic J. L. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 25876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Tobin A. B. (2002) Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 23, 337–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Jones B. W., Song G. J., Greuber E. K., Hinkle P. M. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 12893–12906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Hammes S. R., Shapiro M. J., Coughlin S. R. (1999) Biochemistry 38, 9308–9316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Kara E., Crépieux P., Gauthier C., Martinat N., Piketty V., Guillou F., Reiter E. (2006) Mol. Endocrinol. 20, 3014–3026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Krasel C., Zabel U., Lorenz K., Reiner S., Al-Sabah S., Lohse M. J. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 31840–31848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Niefind K., Guerra B., Ermakowa I., Issinger O. G. (2001) EMBO J. 20, 5320–5331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Olsten M. E., Weber J. E., Litchfield D. W. (2005) Mol. Cell Biochem. 274, 115–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Allende C. C., Allende J. E. (1998) J. Cell. Biochem. Suppl. 30–31, 129–136 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Marin O., Meggio F., Pinna L. A. (1999) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 256, 442–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Korn I., Jacob G., Allende C. C., Allende J. E. (2001) Mol. Cell Biochem. 227, 37–44 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Filhol O., Nueda A., Martel V., Gerber-Scokaert D., Benitez M. J., Souchier C., Saoudi Y., Cochet C. (2003) Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 975–987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Cotlin L. F., Siddiqui M. A., Simpson F., Collawn J. F. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 30550–30556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Teuchert M., Berghöfer S., Klenk H. D., Garten W. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 36781–36789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Nakata A., Kamiguchi H. (2007) J. Neurosci. Res. 85, 723–734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Sarker R., Grønborg M., Cha B., Mohan S., Chen Y., Pandey A., Litchfield D., Donowitz M., Li X. (2008) Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 3859–3870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Korolchuk V. I., Banting G. (2002) Traffic 3, 428–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Döring M., Loos A., Schrader N., Pfander B., Bauerfeind R. (2006) J. Neurochem. 98, 2013–2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Gurevich V. V., Gurevich E. V. (2004) Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 25, 105–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Bonifacino J. S., Traub L. M. (2003) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 72, 395–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Maxfield F. R., McGraw T. E. (2004) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5, 121–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. von Zastrow M., Sorkin A. (2007) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 19, 436–445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Pandey K. N. (2009) Front. Biosci. 14, 5339–5360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Zhao B., Wong A. Y., Murshid A., Bowie D., Presley J. F., Bedford F. K. (2008) Cell. Signal. 20, 1769–1779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Mason A. K., Jacobs B. E., Welling P. A. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 5973–5984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Feliciangeli S., Tardy M. P., Sandoz G., Chatelain F. C., Warth R., Barhanin J., Bendahhou S., Lesage F. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 4798–4805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.