Abstract

The tolQRAB-pal operon is conserved in Gram-negative genomes. The TolQRA proteins of Escherichia coli form an inner membrane complex in which TolQR uses the proton-motive force to regulate TolA conformation and the in vivo interaction of TolA C-terminal region with the outer membrane Pal lipoprotein. The stoichiometry of the TolQ, TolR, and TolA has been estimated and suggests that 4–6 TolQ molecules are associated in the complex, thus involving interactions between the transmembrane helices (TMHs) of TolQ, TolR, and TolA. It has been proposed that an ion channel forms at the interface between two TolQ and one TolR TMHs involving the TolR-Asp23, TolQ-Thr145, and TolQ-Thr178 residues. To define the organization of the three TMHs of TolQ, we constructed epitope-tagged versions of TolQ. Immunodetection of in vivo and in vitro chemically cross-linked TolQ proteins showed that TolQ exists as multimers in the complex. To understand how TolQ multimerizes, we initiated a cysteine-scanning study. Results of single and tandem cysteine substitution suggest a dynamic model of helix interactions in which the hairpin formed by the two last TMHs of TolQ change conformation, whereas the first TMH of TolQ forms intramolecular interactions.

Keywords: Bacteria, Cysteine-mediated Cross-linking, Ion Channels, Membrane Proteins, Protein Assembly

Introduction

The Tol-Pal proteins of the Escherichia coli cell envelope are critical to maintain outer membrane stability (1, 2). In many bacteria, including pathogenic strains, mutations within the genes encoding these proteins display a lethal phenotype, suggesting that the Tol-Pal proteins fulfill an essential function in the bacterial cell (1). Several observations suggested an important function of the Tol-Pal proteins in cell division or outer membrane biogenesis and stability. A role of this system in the late stages of cell division has been proposed (3). The Pal lipoprotein has been shown to interact with the β-barrel assembly machinery complex in Caulobacter crescentus and has been suggested to anchor it to the peptidoglycan layer (4). Recently, Yeh et al. (5) showed that the Tol-Pal proteins of C. crescentus regulate the localization of the TipN polar factor and are therefore key components of the cell envelope structure and of polar development. Finally, tol-pal mutant cells have been shown to release outer membrane vesicles and present important outer membrane defects such as increased susceptibility to toxic compounds and leakage of periplasmic content (1, 6).

Two proteins, TolB and Pal, form a complex associated to the outer membrane (7–9). TolQ, TolR, and TolA locate in the inner membrane. TolR and TolA possess one transmembrane helix (TMH)2 with the bulk of the protein protruding in the periplasm (10, 11). TolQ has three TMHs (12). The three inner membrane proteins TolQ, TolR, and TolA interact through their TMHs with a respective stoichiometry of 4–6:2:1 (12, 13). Pairwise interactions between these three proteins have been detected using chemical cross-linking or isolation of suppressive mutations (12, 14–18). Taken together, these results enabled the building of a first model of organization of the Tol TMHs in the inner membrane.

Sequence comparison showed that the TolAQR complex shares similarities with two other systems using the transmembrane ion potential or proton motive force (PMF). The TonB-ExbB-ExbD and MotA-MotB energy-driven protein complexes use the PMF for the import of iron siderophore or vitamin B12 through the outer membrane and for propelling the flagella, respectively. Parallel studies on the TolQR, ExbBD, and MotAB complexes have suggested the existence of an ion channel delimited by three helices: TolR-TMH and TolQ-TMH2 and -TMH3 (or corresponding TMHs in ExbBD and MotAB (13, 15–18)). Ion channel activity has been proposed to lie on hydrophilic residues conserved in these helices: the aspartate residue in TolR/ExbD/MotB and two threonine residues in TolQ/ExbB/MotA TMHs (13, 17–22). Further targeted mutagenesis demonstrated the importance of these residues in TolQR, ExbBD, and MotAB function (13, 17, 18, 21).

The observation that TolR and TolQ TMHs share residue conservation with those of ExbBD and MotAB suggested that these couples provoke energy-driven mechanisms (13, 19, 20). ExbBD and MotAB convert the chemical energy from the ion or proton gradient of the inner membrane to mechanical movements that lead to import of siderophores and to flagellar rotation, respectively (21, 23). Conformational changes in response to PMF have been demonstrated in these different complexes: rotation of the MotB and TolR transmembrane helices (19, 24) and structural transition of the MotA cytoplasmic domain and of the TolR, ExbD, TonB, and TolA periplasmic domains (21, 22, 25, 26). In addition to PMF, the structural modifications of TonB and TolA have been shown to be dependent upon the ExbBD and TolQR proteins, respectively (25, 26). These conformational changes regulate protein-protein interactions. Upon PMF sensing, the ExbD periplasmic domain interacts with TonB, whereas the TolA C-terminal domain interacts with the Pal outer membrane lipoprotein (13, 27, 28). Despite intensive targeted mutagenesis, cross-linking, and genetic suppressive approaches, no structural information is currently available for the TolQ-TolR, ExbB-ExbD, or MotA-MotB membrane complexes. However, the three-dimensional structures of the soluble periplasmic regions of ExbD and TolR have been solved (29, 30). To gain insights on the organization of the TM segments within the complex, we recently initiated a systematic cysteine-scanning approach. This technique has been widely used, mainly to understand how inner membrane complexes organize in the membrane bilayer and how they work at a mechanistic level. This has been particularly useful for bacterial chemoreceptors, the Sec machinery, ATP/ADP translocases, efflux pump components, and the lactose permease (31–35). Herein, we report the characterization of the TolQ TMHs. First, using functional epitope-tagged versions of TolQ, we provide evidence that TolQ forms dimers and confirm the interaction of TolQ with both TolR and TolA. We then characterized individual cysteine mutants to understand the contribution of the TolQ TMHs residues for intra- and intermolecular interactions.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Strain, Plasmid Construction, and Growth Conditions

The GM1 E. coli TPS13 (tolQR (36)) and Tuner (DE3) (Novagen) strains were used. TPS13 strain contains an amber mutation that decreases the production of TolR to less than 10% (37). Routinely, cells were grown aerobically in LB medium at 37 °C supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg/ml) and/or kanamycin (50 μg/ml) when required. Plasmid pOK-QHA and pQ8R encoding functional TolQ proteins containing a C-terminal hemagglutinin (HA) and a C-terminal 8-histidine tag, respectively, and pUC-R encoding TolR, have been described elsewhere (24, 38). pOK-T7Q8R was constructed using pOK-QR (24) as template by two sequential PCRs: (i) insertion of the sequence encoding the 8-histidine tag to tolQ (using the same primers as previously used for pQ8R) and (ii) the addition of the sequence of the T7 promoter at the XbaI site upstream of the lac operator sequence using primers: 5′-CCTATAGTGAGTCGTATTAAtctagaATACACAACATACGAGCCGCG-3′ and 5′-ATtctagaTTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGGAATTGTGAGCGGATAACAATTTCACACAGG-3′ (XbaI site in lowercase letters, T7 promoter underlined). The tolQ-8his gene was amplified using primers 5′-CCTCTAGAAATAATTTTGTTTAACTTTAAGAAGGAGATATACATATGACTGACATGAATATCCTTGATTTGTTCC-3′ and 5′-GGCTTTGTTAGCAGCCGGATCTCAGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGATGATGGGCGCCCTTGTTGCTCTCGCTAAC-3′ and inserted into the pET28 vector (Novagen) by restriction-free cloning (39) to create pET-Q. TolQ cysteine mutants were obtained by PCR mutagenesis using specific pairs of oligonucleotides (list available on request) using pOK-QHA as template. The pOK-T7Q8R plasmid was used as template to construct the tolQ157C-169C mutant. All constructs were verified by restriction analyses and DNA sequencing. Expression from pET-Q was induced by the addition of 200 μm isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside for 1 h at 30 °C, whereas expressions from pOK-QHA and pQ8R were constitutive.

Phenotypic Analyses

Outer membrane defects were assessed by measuring the level of detergent susceptibility. Serial dilutions of bacteria were spotted onto 1% deoxycholate (DOC)-supplemented LB plates. Survival was reported as the highest dilution of strain able to form colonies. Colicin activities were checked by the presence of halos on a lawn of the strain to be tested, as described previously (18). Data are reported as the maximal dilution of the colicin stock sufficient to inhibit cell growth. (colicin dilutions between 10−6 and 10−9 m).

In Vivo Disulfide Bond Formation and Immunodetection

Cysteine scanning was essentially carried out as described previously (22, 24) with slight modifications. 8 × 108 exponentially growing cells were harvested and resuspended in 1 ml of 20 mm sodium phosphate buffer (PBS), pH 6.8, and then treated for 10 min with 2.5 mm N-ethylmaleimide (NEM; Sigma) to block reduced thiol groups. When required, cells were treated for 20 min with 0.3 mm copper (II) orthophenanthroline (CuoP; Sigma) prior to blocking with NEM. After centrifugation, cell pellets were resuspended in Laemmli loading buffer in the presence or absence of the reducing agent β-mercaptoethanol. To ensure oxidized environmental conditions at the periplasmic and cytoplasmic sides of the TMH, cysteine mutants were also analyzed from membrane preparations; cells were broken by four freeze and thaw cycles, and the suspension was further treated with 2.5 mm NEM. Membranes recovered upon ultracentrifugation were suspended in PBS buffer.

In Vivo Cross-linking and Immunodetection

Formaldehyde cross-linking was performed as described previously (40). In vivo cross-linking with ethylene glycol-bis(succinimidylsuccinate) (Pierce), dithiobis(succinimidyl) propionate (Pierce), and dimethyl adipimidate (Pierce) were performed as described previously (41). Proteins were separated on SDS-PAGE gels and immunodetected with the anti-HA (Roche Applied Science) or the anti-Penta-his (Qiagen) monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) and secondary antibodies coupled to alkaline phosphatase using 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate (Sigma) and nitroblue tetrazolium (Sigma). For co-immunoprecipitations, cells were treated with formaldehyde and disrupted by sonication. Membranes were recovered by ultracentrifugation (45 min at 90,000 × g) and solubilized in TES buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 5 mm EDTA, 1% SDS) for 30 min at 37 °C in the presence of protease inhibitors (Complete, Roche Applied Science). Samples were diluted 15-fold in TNE (10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 5 mm EDTA, 250 mm NaCl) supplemented with 1% Triton X-100. Solubilized samples were then subjected to immunoprecipitation using anti-HA mAb coupled to protein G-agarose beads (Amersham Biosciences) as described previously (22).

Protein Purifications

TolQ8H and TolQ8H-G157C were purified from membrane fractions. Membrane proteins were extracted using 1% n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside in 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mm NaCl buffer in the presence of protease inhibitors (Complete, Roche Applied Science). TolQ8H was purified by ion metal affinity chromatography using nickel resin (Qiagen) equilibrated in 20 mm Tris-HCl, 100 mm NaCl, pH 8.0, buffer supplemented with 0.1% n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside. Eluted material was analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and imidazole was removed by anion exchange chromatography (ResourceQ column, GE Healthcare).

RESULTS

Tagged TolQ Is Functional

Because of the lack of availability of specific anti-sera, the TolQ protein has never been immunodetected using Western blot, precluding any characterization. Interactions involving TolQ have been identified through cross-linking and immunodetection using anti-TolR or anti-TolA polyclonal antibodies (40, 42). We therefore constructed plasmids pOK-QHA and pQ8R that encode the TolQ protein fused to a C-terminal HA epitope and a histidine tag, respectively. Immunoblot analyzes were performed on cell extracts of strains expressing TolQHA from pOK-QHA or TolQ8H from pQ8R using monoclonal antibodies. We detected a protein of ∼30 kDa, consistent with the predicted TolQ molecular mass. To determine whether the addition of the C-terminal tags affected TolQ function, we checked two phenotypes that correlated with a functional TolQ protein; outer membrane stability was assayed by the level of periplasmic release and of DOC sensitivity, whereas colicin import was assayed by the level of sensitivity to the TolQ-dependent colicins A, E3, and E9. Both constructions (pOK-QHA (co-transformed with the compatible TolR-producing pUC-R plasmid) and pQ8R) restored the outer membrane stability and the colicin susceptibility of tolQR cells to wild-type levels (data not shown).

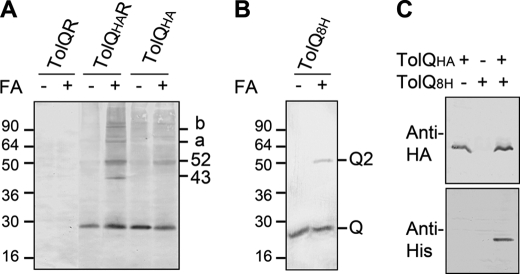

In Vivo Cross-linking Identifies Specific TolQ Complexes

To determine whether the previously described TolQ-TolR interaction might be visualized upon chemical cross-linking, we treated living cells expressing TolQHA with formaldehyde as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Two major complexes containing the TolQHA protein were observed, with relative migrations of ∼43 and ∼52 kDa (Fig. 1A). According to their apparent molecular masses, the 43- and 52-kDa complexes correspond to TolQHA-TolR heterodimer and TolQHA homodimer, respectively (Fig. 1A). The composition of the complexes was further validated by the observation that the 43-kDa complex disappeared in cells that do not produce the TolR protein (Fig. 1A) and displayed a shifted mobility in the presence of TolR variants (supplemental Fig. S1). These complexes involve transmembrane or cytoplasmic segments because utilization of the inner membrane-impermeant chemical cross-linkers ethylene glycol-bis(succinimidylsuccinate), dithiobis(succinimidyl) propionate, and dimethyl adipimidate did not allow complex formation (data not shown). All these complexes were not observed when TolQ was expressed instead of TolQHA. Identical experiments in tol-pal mutant strains indicated that none of these complexes contained the TolA, TolB, or Pal subunits (data not shown). Two additional high molecular mass complexes (a, ∼70 kDa; b, ∼100 kDa) were also observed and likely involved TolQ multimers associated with TolR because they disappeared in cells that do not produce TolR (Fig. 1A). To further confirm that TolQ interacts with itself, we purified TolQ8H from n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside-solubilized membranes of Tuner (DE3) cells overproducing TolQ8H from pQ8R. The purified protein was then tested for its ability to form multimers in vitro upon formaldehyde cross-linking and Western blot immunodetections. Results displayed in Fig. 1B showed that TolQ8H dimerizes. This result was further confirmed by co-precipitation experiments using extracts of cells producing both TolQ8H and TolQHA. Immunoprecipitation using anti-HA beads showed that TolQ8H specifically co-purified with TolQHA (Fig. 1C), whereas TolQHA co-purified with TolQ8H on metal affinity beads (data not shown).

FIGURE 1.

TolQ forms multimers. A, in vivo formaldehyde (FA) cross-linking of TPS13 (tolQR) cells producing the indicated Tol proteins (TolQR, TolQ, and TolR; TolQHAR, TolQHA, and TolR; TolQHA, TolQHA, and no TolR). 0.4 × 108 cells treated (+) or not (−) by the chemical cross-linked formaldehyde were loaded on 12.5% acrylamide SDS-PAGE gel, and TolQHA and TolQHA-containing complexes were immunodetected using anti-HA mAb. The ∼43-, ∼52-kDa, a and b complexes are indicated. B, ∼0.5 μg of the purified TolQ8H protein was treated (+) or not (−) with formaldehyde, loaded on a 12.5% acrylamide SDS-PAGE gel, and immunodetected using anti-His5 mAb. The monomeric (Q) and dimeric (Q2) forms are indicated. C, TPS13 (tolQR) cells producing TolQHA (TPS13 pOK-QHA, lane 1), TolQ8H (TPS13 pQ8R, lane 2), or both proteins simultaneously (TPS13 pQ8R pOK-QHA, lane 3) treated with formaldehyde were solubilized. The TolQHA proteins were immunoprecipitated from detergent-solubilized membrane extracts using the anti-HA mAb, and the TolQHA and TolQ8H proteins were immunodetected using anti-HA (upper panel) and anti-His (lower panel) mAbs. Prestained molecular mass markers (in kDa) are indicated.

Cysteine Scanning of TolQ TMHs

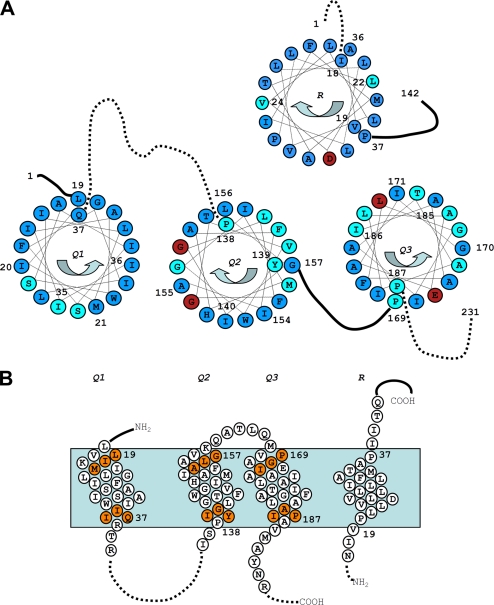

To gain further insight into TolQ multimerization, we constructed single cysteine variants encompassing the three TolQ TMHs (TMH1, amino-acids 19–37; TMH2, amino acids 138–157; and TMH3, amino acids 169–187) (see the topological model in Fig. 2B). Immunodetection indicated that all the TolQ mutant proteins accumulated at comparable levels. We first carried out a phenotypic analysis of cells expressing these tolQ variants by testing (i) the sensitivity to colicins A and E2 (Tol-dependent) and colicin D (TonB-dependent, used as negative control) and (ii) the outer membrane integrity following bacterial growth on DOC plates. Detailed phenotypic analyses for these 58 single substitutions are presented Table 1 and summarized in Fig. 2. Most cysteine substitutions that conferred tol and discriminative phenotypes gather on one discrete face of TMH1 close to the cytoplasm (Ser28-Ser31-Ile35), two discrete faces of TMH2 (Gly141-Gly144-Gly148 and Tyr139-Leu142-Val146), and also close to the cytoplasm and distribute all along TMH3 (Fig. 2A). The results of this cysteine-scanning study were compared with those of TolQ site-directed mutagenesis, which specifically modified small lateral chains, Pro, and hydrophilic residues (18). Comparable phenotypes were obtained for substitutions except for some mutations for which the bulk or the charge of the lateral chains differ from that of a cysteine and two substitutions (Gly157 and Glu173; supplemental Fig. S2).

FIGURE 2.

Summary of the TolQ cysteine substitution phenotypes. A, TolQ TMHs residues shown on a helical wheel projection from the periplasmic to the cytoplasmic side. The color code summarizes the result of the phenotypic analyses of the cysteine substitutions (Table 1): WT phenotype (blue, colicin-sensitive and DOC-resistant), tol phenotype (red, colicin-resistant and DOC-sensitive), and discriminative phenotype (cyan, colicin- and DOC-sensitive). The residues used in the tandem cysteine scanning and Ile154 are numbered. Residues numbered on the outside of the wheel locate at the periplasmic side of the TMH, whereas residues numbered on the inside locate at the cytoplasmic side. Periplasmic and cytoplasmic segments are indicated by unbroken and dashed lines, respectively. The phenotypic analysis of TolR TMH cysteine substitutions (30) is also reported using the same color code. B, schematic lateral view of TolQ and TolR TMHs in which the residues used for the tandem cysteine mutagenesis are indicated by orange balls. The residues locating at the boundaries of each TMH are numbered.

TABLE 1.

Phenotypic analysis of TolQ cysteine mutations

TPS13 (tolQR) cells expressing both the wild-type (WT) tolR from the pUCR plasmid and the tolQ derivatives from the pOK-QHA plasmid were tested for their susceptibility to the Tol-dependent colicins A and E2 and Tol-independent colicin D (Ton-dependent) and their susceptibility to DOC. Only the TolQ mutation is indicated, WT and tolQ corresponding to the TPS13 pUCR pOK-QHA and TPS13 pUCR pOK12 strains, respectively. Colicin sensitivities were tested on bacterial lawns by the spot dilution assay. The number indicated represents the maximal 10-fold dilution of the colicin stock (∼1 mg/ml) still able to kill the strain (R, resistant; 4, sensitive to the 104 dilution). Underlined numbers correspond to turbid halo. Deoxycholate resistance was tested by spotting 10-fold dilutions of the strain on 1% DOC LB plates. The number indicated represents the maximal dilution able to form colonies (R, resistant; S, sensitive; numbers, 10n dilution). A summary is indicated in the Phenotype column using the color code shown in Figure 2A: B (blue, WT phenotype, colicin-sensitive and DOC-resistant), R (red; tol phenotype, colicin-resistant and DOC-sensitive), and C (cyan; discriminative phenotype, colicin- and DOC-sensitive). The ability of the TolQ cysteine variants to form homodimer (see supplemental Fig. S3) is indicated by + in the “complex formation” column. OM, outer membrane.

| Mutation | Colicin activities |

OM stability (DOC) | Complex formation | Phenotype | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | E2 | D | ||||

| WT | 4 | 4 | 4 | R | − | B |

| tolQ | R | R | 4 | S | − | R |

| TMH1 | ||||||

| L19C | 4 | 4 | 4 | R | − | B |

| I20C | 4 | 4 | 4 | R | − | B |

| M21C | 4 | 4 | 4 | R | − | B |

| L22C | 4 | 4 | 4 | R | − | B |

| I23C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | − | B |

| L24C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | − | B |

| I25C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | − | B |

| G26C | 4 | 4 | 4 | R | − | B |

| F27C | 4 | 4 | 4 | R | − | B |

| S28C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 | − | C |

| I29C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | − | B |

| A30C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | − | B |

| S31C | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 | − | C |

| W32C | 4 | 4 | 4 | R | − | B |

| A33C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | − | B |

| I34C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | − | B |

| I35C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 | − | C |

| I36C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | − | B |

| Q37C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | − | B |

| TMH2 | ||||||

| P138C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 | − | C |

| Y139C | 4 | 4 | 4 | S | − | C |

| I140C | 4 | 4 | 4 | R | − | B |

| G141C | R | R | 4 | S | − | R |

| L142C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 | − | C |

| F143C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | − | B |

| G144C | R | R | 4 | S | − | R |

| T145C | 4 | 4 | 4 | R | − | B |

| V146C | 3 | 4 | 4 | 1 | − | C |

| W147C | 3 | 4 | 4 | R | − | B |

| G148C | 2 | 2 | 4 | S | − | C |

| I149C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | − | B |

| M150C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 | − | C |

| H151C | 4 | 4 | 4 | R | − | B |

| A152C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | − | B |

| F153C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | − | C |

| I154C | 4 | 4 | 4 | R | + | B |

| A155C | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | − | B |

| L156C | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | − | B |

| G157C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | + | B |

| TMH3 | ||||||

| P169C | 3 | 4 | 4 | 1 | − | C |

| G170C | 4 | 4 | 4 | R | − | B |

| I171C | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | − | B |

| A172C | 4 | 4 | 4 | R | − | B |

| E173C | R | R | 4 | 1 | − | R |

| A174C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 | − | C |

| L175C | 3 | 4 | 4 | S | − | C |

| I176C | 4 | 4 | 4 | R | − | B |

| A177C | 3 | 3 | 4 | S | − | C |

| T178C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 | − | C |

| A179C | 4 | 4 | 4 | R | − | B |

| I180C | 4 | 4 | 4 | R | − | B |

| G181C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 | − | C |

| L182C | R | R | 4 | S | − | R |

| F183C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | − | B |

| A184C | 4 | 4 | 4 | R | − | B |

| A185C | 4 | 4 | 4 | R | − | B |

| I186C | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 | − | C |

| P187C | 4 | 4 | 4 | S | − | C |

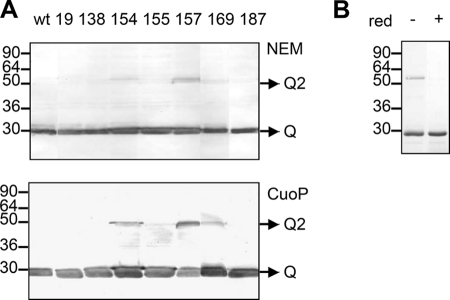

We then tested whether the single cysteine substitutions might induce intermolecular disulfide bonds. Total membrane extracts were treated with the thiol-blocking agent NEM and analyzed using non-reducing SDS-PAGE conditions. Two TolQ cysteine mutants, I154C and G157C, formed homodimers (supplemental Fig. S3). Interestingly, these two residues are present on the same face of TMH2, separated by one helix turn, and close to the periplasmic side. These dimers were not observed in the presence of reducing agent (data not shown). Because the experiments were performed with membrane preparations and could reflect artifactual cysteine oxidization, the experiments were repeated with whole cells producing TolQHA or overproducing TolQ8H that were directly treated by NEM. Identical results to those with membrane preparations were obtained for the TolQHA variant-producing cells (data not shown). The TolQ8H variants that were overexpressed included the residues shown to dimerize (TolQ154C and TolQ157C), the residues flanking the TolQ TMHs, and the TMH2 A155C as control. The results of disulfide bond formation on intact cells overproducing the TolQ8H variants confirmed that TolQ154C and TolQ157C formed homodimers, whereas TolQ155C remained as a monomer (Fig. 3A, upper panel). The addition of the oxidizing agent CuoP on intact (Fig. 3A, lower panel) or disrupted cells (not shown) resulted in an increase of TolQ154C and TolQ157C dimer levels and the apparition of a weak TolQ169C dimer. Coomassie Blue staining of purified TolQ157C further indicated that the dimer accumulated in significant amount even in the absence of CuoP (Fig. 3B).

FIGURE 3.

TolQ dimerizes through TMH2-TMH2 contacts. A, 0.4 × 108 Tuner (DE3) pET-Q cells producing the indicated TolQ8H variant were incubated (lower panel) or not (upper panel) with 0.3 mm CuoP before treatment with the thiol-blocking agent NEM. Heat-denatured samples were loaded on a non-reducing 12% acrylamide SDS-PAGE gel and analyzed by Western blot immunodetections using anti-His5 mAb. Prestained molecular mass markers (in kDa) and TolQ monomers (Q) and dimers (Q2) are indicated. B, about 3 μg of n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside purified TolQ8H157C treated (+) or not (−) with the reducing agent β-mercaptoethanol (red) was loaded on a 12.5% acrylamide SDS-PAGE gel and analyzed by Coomassie Blue staining.

To broaden the results on TolQ TMH2 intermolecular disulfide bond formation, we constructed ExbB cysteine substitutions, targeting the ExbB-Ile157, -Gly158, and -Ala160 residues. These residues correspond to the TolQ-Ile154, -Ala155, and -Gly157 positions, respectively. As observed for TolQ, ExbB-I157C and -A160C formed disulfide bond dimers, whereas no thiol-linked product was observed with ExbB-G158C (data not shown).

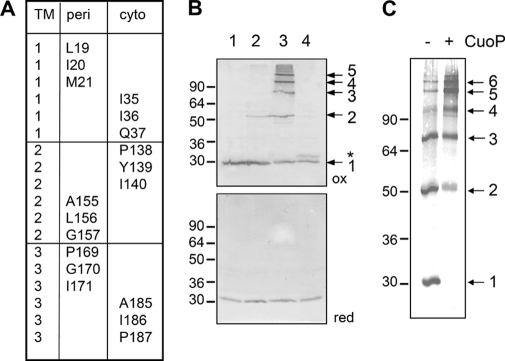

Tandem Cysteine Cross-linking Identifies Intra- and Intermolecular Interactions between TolQ TM Segments

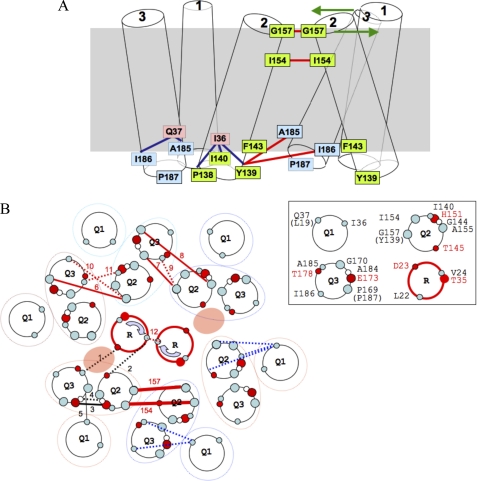

To further define the overall organization of TolQ multimers, we performed a tandem cysteine scanning (Fig. 4A). We targeted residues from two different TMHs and present on the first and last helix turns of the TMH. Combinations between three residues located at the cytoplasmic side and three at the periplasmic side were constructed, leading to 54 double mutants.

FIGURE 4.

Tandem cysteine scanning of TolQ TMHs. A, summary of the residues present at the cytoplasmic (cyto) and periplasmic (peri) extremities of the TolQ TMHs targeted for the tandem cysteine scanning. All tandem combinations at the cytoplasmic or periplasmic side were tested for their phenotypes (Table 2) and their ability to form disulfide bridges (see supplemental Fig. S4). B, representative profiles obtained for TolQ double cysteine mutants. Membrane extracts from 0.4 × 108 TPS13 (tolQR) cells producing TolR and the WT TolQHA protein (class i, lane 1) or the TolQHA-G157C (class ii, lane 2), -G157C/P169C (class iii, lane 3), or -Q37C/I186C (class iv, lane 4) cysteine mutants were loaded on a 12% SDS-PAGE gel and analyzed by Western blot immunodetections using anti-HA mAb (upper panel, non-reducing conditions (ox); lower panel, β-mercaptoethanol-treated samples (red)). The TolQ monomer and multimers are indicated by arrows on the left. The asterisk indicates a TolQ mobility shift associated with an intramolecular disulfide bond. C, 0.4 × 108 Tuner (DE3) cells producing the TolQ8H-G157C/P169C double mutant, treated (+) or not (−) with the oxidative agent CuoP, were heat-denatured in Laemmli buffer and analyzed by non-reducing 12% acrylamide SDS-PAGE gel and Western blot immunodetection using anti-His5 mAb. Prestained molecular mass markers (in kDa) are indicated on the left.

The tandem tolQ mutants were tested for colicin susceptibility and outer membrane defects (Table 2). In general, combining mutations resulted in the phenotype of the less tolerant mutant or to additive effects. It is noteworthy that we did not observe compensatory mutations (i.e. a second Cys mutation compensating the effect of the primary mutation). As an example, although the single G157C and P169C mutations conferred few membrane defects and little colicin tolerance (see Table 1), the double G157C/P169C substitution induced strong effects for both phenotypes. The TolQ double mutants were then tested for their ability to form disulfide bonds. Membrane extracts were treated with NEM and separated on non-reducing SDS-PAGE gels. The results of TolQHA immunodetection revealed four profiles: (i) monomer; (ii) dimer (intermolecular S–S bridge); (iii) high order multimers; and (iv) slight aberrant shift mobility of monomer (supplemental Fig. S4). A representative example of each of the four classes is shown in Fig. 4B (upper panel). Migration of these samples in reducing conditions led to the immunodetection of TolQHA monomers; interestingly, class iv mutants recovered a wild-type mobility (Fig. 4B, lower panel), suggesting that the slight mobility defect of these mutant proteins in non-reducing conditions reflects intramolecular disulfide bond formation.

TABLE 2.

Phenotypic analysis of TolQ double cysteine mutations

Same legend as Table I except that additional complexes (see supplemental Fig. S4) are indicated in the Complex formation column (di, dimer; (di), weak dimer; in, intramolecular bond; x, multimer).

| Mutation | Colicin activities |

DOC | Complex formation | Phenotype | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | E2 | D | ||||

| WT | 4 | 4 | 4 | R | − | B |

| tolQ | R | R | 4 | S | − | R |

| Periplasmic side | ||||||

| L19C/A155C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | − | B |

| L19C/L156C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | − | B |

| L19C/G157C | 4 | 4 | 4 | R | (di) | B |

| L19C/P169C | 3 | 3 | 4 | S | − | C |

| L19C/G170C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | − | B |

| L19C/I171C | 4 | 4 | 4 | R | − | B |

| I20C/A155C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | (di) | B |

| I20C/L156C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 | − | C |

| I20C/G157C | 4 | 3 | 4 | S | di | C |

| I20C/P169C | 3 | 3 | 4 | S | − | C |

| I20C/G170C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | − | C |

| I20C/I171C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | − | B |

| M21C/A155C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | − | B |

| M21C/L156C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | − | B |

| M21C/G157C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 | di | C |

| M21C/P169C | R | R | 4 | S | − | R |

| M21C/G170C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 | − | C |

| M21C/I171C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | − | B |

| A155C/P169C | 3 | 3 | 4 | S | x | C |

| A155C/G170C | 4 | 4 | 4 | S | (di) | C |

| A155C/I171C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 | (di) | C |

| L156C/P169C | 3 | 3 | 4 | S | (di) | C |

| L156C/G170C | 2 | 2 | 4 | S | (di) | C |

| L156C/I171C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 | (di) | C |

| G157C/P169C | R | R | 4 | S | x | R |

| G157C/G170C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 | x | C |

| G157C/I171C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 | (di) | C |

| Cytoplasmic side | ||||||

| I35C/P138C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 | − | C |

| I35C/Y139C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 | − | C |

| I35C/I140C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | − | C |

| I35C/A185C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 | − | C |

| I35C/I186C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 | − | C |

| I35C/P187C | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 | − | C |

| I36C/P138C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | in-(di) | C |

| I36C/Y139C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 | in-(di) | C |

| I36C/I140C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | in | B |

| I36C/A185C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 | − | C |

| I36C/I186C | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 | − | C |

| I36C/P187C | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | − | C |

| Q37C/P138C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | − | C |

| Q37C/Y139C | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 | (di) | C |

| Q37C/I140C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | (di) | C |

| Q37C/A185C | 4 | 4 | 4 | R | in | B |

| Q37C/I186C | 3 | 2 | 4 | 2 | in-(di) | C |

| Q37C/P187C | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | (di) | C |

| P138C/A185C | 3 | 3 | 4 | 2 | − | C |

| P138C/I186C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 | − | C |

| P138C/P187C | R | R | 4 | S | − | R |

| Y139C/A185C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 | di | C |

| Y139C/I186C | 3 | 2 | 4 | S | di | C |

| Y139C/P187C | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 | − | C |

| I140C/A185C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 | di | C |

| I140C/I186C | 3 | 2 | 4 | S | − | C |

| I140C/P187C | 4 | 3 | 4 | S | − | C |

Analysis of the TolQHA double cysteine mutant collection revealed intermolecular interactions between TMH2 and TMH3 residues located at the cytoplasmic (Tyr139-Ala185, Tyr139-Ile186, and Ile140-Ala185) or at the periplasmic side (Ala155-Pro169, Gly157-Pro169, and Gly157-Gly170) (supplemental Fig. S4). Cysteine residues at positions 155 and 157 form weak dimers with cysteine residues present on TMH3 (Ala155-Gly170, Ala155-Ile171; Gly157-Ile171). Weak dimers were also observed at the cytoplasmic and periplasmic interfaces (Gln37-Tyr139 and Gln37-Ile140; Leu156-Pro169, Leu156-Gly170, and Leu156-Ile171; Ile20-Ala155). More interestingly, it is noteworthy that disulfide bridges occurred between TMH2 and TMH3 residues but only rarely between TMH1 and TMH2 or TMH3. TMH1 is likely involved in intramolecular interactions because class iv combinations were detected between TMH1 and TMH2 (Ile36-Pro138, Ile36-Tyr139, and Ile36-Ile140), as well as between TMH1 and TMH3 (Gln37-Ala185 and Gln37-Ile186) (supplemental Fig. S3). Importantly, no intramolecular disulfide bridge between TMH2 and TMH3 was detected. Because G157C substitution alone resulted in homodimer formation, the dimers that contain the G157C substitution were not considered except when double substitutions allowed the formation of multimers of higher multiplicity than dimer.

To avoid oxidation artifacts due to membrane preparation before the alkylation of thiol groups, we reproduced the experiments with intact cells directly treated by NEM. In these conditions, cysteine residues located at the periplasmic side were still able to cross-link as observed in supplemental Fig. S4, whereas no cross-link was detected for cysteines located at the cytoplasmic side (data not shown). This is in agreement with the reducing environment of the cytoplasm. To verify that multimer formation was not an artifact due to the HA tag, we introduced the G157C and P169C substitutions into the pOK-T7Q8R plasmid. Cells overproducing TolQ8H-G157C/P169C were treated by NEM prior to SDS-PAGE analysis. Immunodetections using the anti-His mAb revealed that TolQ8H-G157C/P169C formed multimers. Although multimers containing up to five TolQ proteins can be detected under low TolQHA production (Fig. 4B), an additional higher TolQ multimer was obtained under TolQ8H-overproduced conditions (Fig. 4C). Treatment of intact cells overproducing the TolQ8H variant with CuoP resulted in decreased amounts of the TolQ8H monomer and dimer and increased multimeric forms of higher molecular weight (Fig. 4C).

DISCUSSION

TolQ Multimerizes

The TolQRA proteins of the Tol-Pal system form a complex in the inner membrane. Genetic and biochemical studies have evidenced pairwise interactions between the transmembrane segments of these three subunits. Using formaldehyde cross-linking, TolR has been shown to form dimers and to interact with both TolQ and TolA (42). TolA has been shown to interact with both TolQ and TolR using similar approaches (40). Isolation of suppressive mutations also brought information on heterodimer formation. Suppressive mutations of the non-functional TolQ mutants, A177V (TMH3) (43) or T145A (TMH2), were identified in the TolR anchor, whereas a suppressive mutation of the TolR D23A mutant was isolated in TolQ TMH3 (18). The TolA TMH interacts with the TolQ TMH1, as shown by the suppressive mutation of the conserved His22 (H22P and H22R) residue of TolA found in TolQ TMH1 (44). Within TolQ, two other intragenic suppressive mutations were identified, including the couples Gly144 (TMH2)/Ala184 (TMH3) and Ala177 (TMH3)/Leu19 (TMH1) (18, 43). However, the lack of reliable anti-TolQ antibody prevented further studies on this protein. In this work, using functional tagged TolQ proteins, we demonstrated that TolQ interacts with TolR and with itself. Formation of TolQ multimers was confirmed by co-immunoprecipitation and in vitro cross-linking experiments using the purified His-tagged TolQ protein. Our results correlate with previous studies on the homologous ExbB and MotA proteins. Chemical cross-linking showed that ExbB forms homodimers and homotrimers (45), and a recent study demonstrated that ExbB assembles as a stable oligomer containing 4–6 molecules (46). Although no biochemical evidence had demonstrated MotA dimerization, intermolecular disulfide bonds were identified using a cysteine-scanning approach (16, 47). These latter studies also identified MotA TMH residues that face each other.

Organization of TolQ TMHs

The cysteine-scanning approach reported in our work also provides important information on the overall organization of the TolQ helices. We showed that two residues, Ile154 and Gly157, located on the same face at the periplasmic side of TMH2, are at the interface of two TolQ molecules. Identical results were obtained using membrane preparations or intact cells producing TolQ variants or both TolQ variants and TolR. The TolQ homodimerization is therefore independent of the TolR protein and may reflect an interaction of TolQ TMH2 either within the same TolQR complex or between two adjacent TolQR complexes. Although Tyr139 and Phe143 locates on the same face of TolQ TMH2 but on the cytoplasmic side, we did not observe intermolecular disulfide bonds between TolQ-Y139C or TolQ-F143C even upon oxidized conditions in membrane extracts. This result suggests that the two adjacent TMH2 helices are either twisted or kinked, with closer contacts at the periplasmic side (Fig. 5A). An alternative hypothesis is that the two bulky Tyr139 and Phe143 residues pull out the two helices at the cytoplasmic side.

FIGURE 5.

Schematic model of the TolQ and TolR TMH interactions. A, putative model of TolQ TMH arrangement emphasizing side-specific contacts. Two adjacent TolQ molecules are depicted. TMH1, -2, and -3 are indicated. Residues of TMH1 (light pink), TMH2 (light green), and TMH3 (light blue) involved in intermolecular (symbolized by red sticks) and intramolecular (symbolized by the blue sticks) interactions are indicated. Putative TMH rearrangements are indicated by green arrows. B, putative model of TolQ-TolR TMHs organization. TolQ-TolR residues in contact are shown in a model containing six TolQ molecules, two TolR molecules, and two putative ionic channels. TolQ TMH organization defined by genetic suppressive data was kept identical in each TolQ molecule. Balls represent cysteine-substituted positions involved in disulfide bond formation (large balls, residues at the periplasmic side of TMHs; small balls, residues at the cytoplasmic side of TMHs). Disulfide interactions are symbolized by red (intermolecular) or blue (intramolecular) sticks, whereas suppressor pairs are indicated by black sticks (unbroken, periplasmic side; dotted, cytoplasmic side). Numbers above the sticks indicate the following TMH intermolecular interactions: i) suppressors, (1) TolR-D23A/TolQ-A185D; (2) TolR-M33Q/TolQ-T145A; (3) TolQ-H151E/TolQ-E173Q; (4) TolQ-G144A/TolQ-A184G; (5) TolQ-A177V/TolQ-L19P; ii) cysteine substitutions, (6) TolQ-Gly157/TolQ-Pro169; (7) TolQ-Gly157/TolQ-Gly170; (8) TolQ-Ala155/TolQ-Pro169; (9) TolQ-Tyr139/TolQ-Ala185; (10) TolQ-Tyr139/TolQ-Ile186; (11) TolQ-Ile140/TolQ-Ala185; (12) TolR-Leu22/TolR-Leu22; (arrow) TolR-Val24/TolR-Val24; (157) TolQ-Gly157/TolQ-Gly157; (154) TolQ-Gly154/TolQ-Gly154. The intramolecular TMH1-TMH2 and TMH1-TMH3 interactions indicated by blue sticks are shown without numbering (TolQ-Ile36/TolQ-Pro138/Tyr139/Ile140 and TolQ-Gln37/TolQ-Ale185/Ile186). The different TMHs of the TolQ and TolR proteins are shown in the inset with residues shown to be involved in dimer formation in this work (represented by gray balls). Polar (red balls) and small lateral chain residues (white balls) characterized in previous studies (18, 24) are also indicated.

With the limited information obtained with single cysteine substitutions, we constructed tandem cysteine mutants. We restricted our study to one helix turn (three residues) located at the cytoplasmic or periplasmic side of the TMHs. The 54 mutants were analyzed for their ability to form inter- and intramolecular interactions (Fig. 5). Overall, our results demonstrated TMH1-TMH2 and TMH1-TMH3 intramolecular interactions (Fig. 5A, blue sticks). This result supports previously published data identifying the TMH1 L19P mutation as a suppressor of the TMH3 A177V substitution (43). Intramolecular interactions have been obtained with tandem substitutions located at the cytoplasmic side, suggesting that TMH1-TMH2 and TMH1-TMH3 contacts are closer at the cytoplasm boundaries (Fig. 5A). It is important to note that no intramolecular interaction has been identified between TMH2 and TMH3. Although this first seems contradictory with recent results that identified suppressive and compensatory effects between TMH2 and TMH3 mutations (18), it remains possible that suppression occurred between two adjacent TolQ molecules or that the lack of disulfide bond might be due to misorientation of the cysteine side chains. Indeed, a number of intermolecular bridges between TMH2 and TMH3 were observed (Fig. 5A, red sticks). We also observed intermolecular contacts between two adjacent TMH2 helices. Taking into account these results, the first hypothesis is that adjacent TolQ molecules are mirrored, contacting each other through a TMH2-TMH2 and consequently a TMH3-TMH3 interface. For example, whereas G157C alone forms dimers, the introduction of an additional second mutation (either P169C or G170C) within TMH3 will induce the formation of multimers. By contrast, the cysteine-scanning of the MotA protein indicated intermolecular contacts between the TMHs homologous to TolQ TMH2 and TMH3 (16). Although it remains possible that TolQ and MotA do not share identical organizations, Braun et al. (16) reported the observation of MotA multimers by combining the V181C and F210C cysteine substitutions. Our results also demonstrate formation of intermolecular TMH2-TMH3 contacts at the cytoplasmic side. The absence of dimerization of the single cysteine substitutions (Y139C, A185C, and I186C) and the dimer formation of the tandem cysteine substitutions argue in favor of TMH2-TMH3 interactions in which disulfide bridges result from heterocysteine contacts at the cytoplasmic side (Fig. 5A, red sticks). It is thus difficult to reconcile TMH2-TMH2 contacts at the periplasmic side and TMH2-TMH3 contacts at the cytoplasmic side. An exciting and interesting possibility will be that broad rearrangements occur between the TMH2 and TMH3, allowing cyclic transitions between TMH2-TMH2 contacts through the periplasmic side to TMH2-TMH3 contacts at the cytoplasmic side (Fig. 5A, green arrows). We are currently investigating the different possibilities by mass spectrometry analyses of purified thiol-linked multimers.

Interestingly, we broadened our results on the TolQ protein to the homologous ExbB protein of the ExbB-D complex. As expected from the strong conservation of the TMHs of TolQ and ExbB proteins, we observed intermolecular bonds between ExbB TMH2 cysteine mutants.

A putative model of TMH organization in the TolQR complex is shown in Fig. 5B. The large number of helices involved in TolQ-TolR complex assembly renders it difficult to draw a tentative model of TolQR TMH organization based on our cysteine scanning and on previously published genetic data. This is even more complicated if we complete the model with the ExbBD and MotAB data. We therefore restricted the model to the cysteine-scanning and genetic data on the TolQR complex. Although we can accommodate most of the intra- and intermolecular interactions, several identified contacts are difficult to reconcile with the current model. The difficulty to draw a clear and comprehensible static model can be inferred from the facts that (i) several of these TMHs might be twisted, kinked, or arranged in a non-parallel organization and (ii) these proteins are probably involved in a highly dynamic process involving periodical TMH rearrangements. Indeed, the TolR anchor (and the corresponding TM segment of MotB) has been previously shown to rotate (19, 24), whereas large conformational modifications of MotA have been evidenced by limited proteolysis (21).

The cysteine-scanning study of the TolQ TMHs gave significant results to address the TolQ organization within the TolQR complex. However, a number of questions remain unanswered such as the dynamic of TolQR TMH interactions and conformations, as well as the regulation of these structural modifications by the PMF.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Denis Duché, James Sturgis, and Jean-Pierre Duneau for helpful discussions and Denis Bars for encouragement.

This work was supported by the CNRS and a grant from the Agence National de la Recherche (SODATOL (ANR-07-BLAN-67)), by a grant from SODATOL (to X. Y.-Z. Z.), and a one-year fellowship from the Fondation pour la Recherche Medicale (FRM) (to E. L. G.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S4.

- TMH

- transmembrane helix

- TM

- transmembrane

- PMF

- proton-motive force

- DOC

- deoxycholate

- NEM

- N-ethyl maleimide

- CuoP

- copper (II) orthophenanthroline.

REFERENCES

- 1. Lloubès R., Cascales E., Walburger A., Bouveret E., Lazdunski C., Bernadac A., Journet L. (2001) Res. Microbiol. 152, 523–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lazzaroni J. C., Germon P., Ray M. C., Vianney A. (1999) FEMS Microbiol. Lett 177, 191–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gerding M. A., Ogata Y., Pecora N. D., Niki H., de Boer P. A. (2007) Mol. Microbiol. 63, 1008–1025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Anwari K., Poggio S., Perry A., Gatsos X., Ramarathinam S. H., Williamson N. A., Noinaj N., Buchanan S., Gabriel K., Purcell A. W., Jacobs-Wagner C., Lithgow T. (2010) PLoS ONE 5, e8619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yeh Y. C., Comolli L. R., Downing K. H., Shapiro L., McAdams H. H. (2010) J. Bacteriol. 192, 4847–4858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Deatherage B. L., Lara J. C., Bergsbaken T., Rassoulian Barrett S. L., Lara S., Cookson B. T. (2009) Mol. Microbiol. 72, 1395–1407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bouveret E., Derouiche R., Rigal A., Lloubès R., Lazdunski C., Bénédetti H. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 11071–11077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cascales E., Lloubès R. (2004) Mol. Microbiol. 51, 873–885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bonsor D. A., Hecht O., Vankemmelbeke M., Sharma A., Krachler A. M., Housden N. G., Lilly K. J., James R., Moore G. R., Kleanthous C. (2009) EMBO J. 28, 2846–2857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Levengood-Freyermuth S. K., Click E. M., Webster R. E. (1993) J. Bacteriol. 175, 222–228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Muller M. M., Vianney A., Lazzaroni J. C., Webster R. E., Portalier R. (1993) J. Bacteriol. 175, 6059–6061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vianney A., Lewin T. M., Beyer W. F., Jr., Lazzaroni J. C., Portalier R., Webster R. E. (1994) J. Bacteriol. 176, 822–829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cascales E., Lloubès R., Sturgis J. N. (2001) Mol. Microbiol. 42, 795–807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Guihard G., Boulanger P., Bénédetti H., Lloubés R., Besnard M., Letellier L. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 5874–5880 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Blair D. F., Berg H. C. (1991) J. Mol. Biol. 221, 1433–1442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Braun T. F., Al-Mawsawi L. Q., Kojima S., Blair D. F. (2004) Biochemistry. 43, 35–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Braun V., Herrmann C. (2004) J. Bacteriol. 186, 4402–4406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Goemaere E. L., Cascales E., Lloubès R. (2007) J. Mol. Biol. 366, 1424–1436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Braun T. F., Blair D. F. (2001) Biochemistry. 40, 13051–13059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhai Y. F., Heijne W., Saier M. H., Jr. (2003) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1614, 201–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kojima S., Blair D. F. (2004) Biochemistry 43, 26–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Goemaere E. L., Devert A., Lloubès R., Cascales E. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 17749–17757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Postle K., Kadner R. J. (2003) Mol. Microbiol. 49, 869–882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhang X. Y., Goemaere E. L., Thomé R., Gavioli M., Cascales E., Lloubès R. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 4275–4282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Larsen R. A., Thomas M. G., Postle K. (1999) Mol. Microbiol. 31, 1809–1824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Germon P., Ray M. C., Vianney A., Lazzaroni J. C. (2001) J. Bacteriol. 183, 4110–4114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cascales E., Gavioli M., Sturgis J. N., Lloubès R. (2000) Mol. Microbiol. 38, 904–915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ollis A. A., Manning M., Held K. G., Postle K. (2009) Mol. Microbiol. 73, 466–481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Garcia-Herrero A., Peacock R. S., Howard S. P., Vogel H. J. (2007) Mol. Microbiol. 66, 872–889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Parsons L. M., Grishaev A., Bax A. (2008) Biochemistry. 47, 3131–3142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Abramson J., Smirnova I., Kasho V., Verner G., Kaback H. R., Iwata S. (2003) Science 301, 610–615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ding P. Z., Weissborn A. C., Wilson T. H. (2001) J. Membr. Biol. 183, 33–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hermolin J., Dmitriev O. Y., Zhang Y., Fillingame R. H. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 17011–17016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lee G. F., Dutton D. P., Hazelbauer G. L. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 5416–5420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Seeger M. A., von Ballmoos C., Eicher T., Brandstätter L., Verrey F., Diederichs K., Pos K. M. (2008) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15, 199–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sun T. P., Webster R. E. (1986) J. Bacteriol. 165, 107–115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Vianney A., Muller M. M., Clavel T., Lazzaroni J. C., Portalier R., Webster R. E. (1996) J. Bacteriol. 178, 4031–4038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Barnéoud-Arnoulet A., Gavioli M., Lloubès R., Cascales E. (2010) J. Bacteriol. 192, 5934–5942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. van den Ent F., Löwe J. (2006) J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods 67, 67–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Derouiche R., Bénédetti H., Lazzaroni J. C., Lazdunski C., Lloubès R. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 11078–11084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cascales E., Bernadac A., Gavioli M., Lazzaroni J. C., Lloubes R. (2002) J. Bacteriol. 184, 754–759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Journet L., Rigal A., Lazdunski C., Bénédetti H. (1999) J. Bacteriol. 181, 4476–4484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lazzaroni J. C., Vianney A., Popot J. L., Bénédetti H., Samatey F., Lazdunski C., Portalier R., Géli V. (1995) J. Mol. Biol. 246, 1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Germon P., Clavel T., Vianney A., Portalier R., Lazzaroni J. C. (1998) J. Bacteriol. 180, 6433–6439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Higgs P. I., Myers P. S., Postle K. (1998) J. Bacteriol. 180, 6031–6038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pramanik A., Zhang F., Schwarz H., Schreiber F., Braun V. (2010) Biochemistry 49, 8721–8728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kim E. A., Price-Carter M., Carlquist W. C., Blair D. F. (2008) Biochemistry 47, 11332–11339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.