Abstract

In the fetus, leptin in the circulation increases at late gestation and likely influences fetal organ development. Increased surfactant by leptin was previously demonstrated in vitro using fetal lung explant. We hypothesized that leptin treatment given to fetal sheep and pregnant mice might increase surfactant synthesis in the fetal lung in vivo. At 122–124 days gestational age (term: 150 days), fetal sheep were injected with 5 mg of leptin or vehicle using ultrasound guidance. Three and a half days after injection, preterm lambs were delivered, and lung function was studied during 30-min ventilation, followed by pulmonary surfactant components analyses. Pregnant A/J mice were given 30 or 300 mg of leptin or vehicle by intraperitoneal injection according to five study protocols with different doses, number of treatments, and gestational ages to treat. Surfactant components were analyzed in fetal lung 24 h after the last maternal treatment. Leptin injection given to fetal sheep increased fetal body weight. Control and leptin-treated groups were similar in lung function (preterm newborn lamb), surfactant components pool sizes (lamb and fetal mice), and expression of genes related to surfactant synthesis in the lung (fetal mice). Likewise, saturated phosphatidylcholine and phospholipid were normal in mice lungs with absence of circulating leptin (ob/ob mice) at all ages. These studies coincided in findings that neither exogenously given leptin nor deficiency of leptin influenced fetal lung maturation or surfactant pool sizes in vivo. Furthermore, the key genes critically required for surfactant synthesis were not affected by leptin treatment.

Keywords: respiratory distress syndrome, phospholipid, ob/ob mice, surfactant protein B, Slc34a2

alveolar surface is overlaid with a pulmonary surfactant film, which reduces surface tension occurring on the alveolar surface (48). Low surface tension is critical for gas exchange, alveolar capillary blood flow (25), and alveolar macrophage function of phagocytosis (1). In the fetal lung, the synthesis of pulmonary surfactant dramatically increases at late gestation to prepare for transition to air breathing at birth. Increases in surfactant saturated phosphatidylcholine (Sat PC) pool size correlate with the increase in dynamic lung compliance in the developing lung (23), and deficiency of surfactant causes respiratory distress syndrome in the preterm newborn infant. Maternal corticosteroid treatment has been used to induce fetal lung maturation for high-risk pregnancies of premature delivery, and preterm newborn infants are routinely treated with surfactant, yet mortality rate of the preterm newborn infants still remains high. New therapy to induce fetal lung maturation and surfactant synthesis has been sought.

Leptin is a 16-kDa polypeptide hormone that is principally synthesized and secreted by adipose tissue in a number of organs, including lipofibroblast in the lung (18, 45, 46). Leptin has a wide range of physiological function, such as regulation of satiety, energy metabolism, bone formation, and reproduction. In the human and sheep fetus, leptin is secreted mainly by fetal adipose tissue (43) into the circulation that increases at late gestation (7, 12) and likely influences fetal organ development (18, 46). Increase in synthesis of surfactant lipid and surfactant proteins by the addition of leptin was demonstrated in vitro using fetal lung explant in culture (27, 44, 45). The only in vivo study of maternal leptin treatment for fetal lung maturation was on the rat, in which 14% increase in fetal lung weight relative to body weight was stated. Surfactant components were not quantitatively analyzed in this previous study (27). The efficacy of leptin treatment to increase surfactant lipid synthesis in the fetal lung is presently unknown.

Although the ob/ob mouse has a point mutation in the ob gene that results in the total absence of circulating leptin, ob/ob mice do not have any respiratory problems at birth. If leptin plays a critical role in fetal lung development in the mouse, deficiency of the leptin would cause lung development disorder and would have problems in a transition to air breathing at birth. It has been explained that fetal plasma contains enough leptin from the maternal heterozygous ob/+ mouse side (42) to induce normal lung maturation in ob/ob mice fetus. On the contrary, according to other studies, synthesis of leptin in placenta was minimal in mice (16), and the level of leptin in the ob/ob mouse fetal plasma was low or not detectable (13). The leptin in fetal plasma was higher in humans and sheep than mice, suggesting that there might be species differences in influence of leptin to surfactant synthesis and lung maturation in the fetal lung. The adult ob/ob mice showed depressed pulmonary function, such as hypercapnia, altered pressure-volume curve, and decreased alveolar space (36). Interestingly, these pulmonary abnormalities in adult ob/ob mice appeared before pronounced obesity and were partially restored by exogenous leptin treatment (34, 42). It is presently unknown whether pulmonary abnormalities in adult ob/ob mice are, at least in part, associated with altered surfactant homeostasis.

In the present study, we will evaluate the influence of leptin on lung maturation and surfactant synthesis in sheep and mice by the following experiments: 1) study the efficacy of fetal leptin treatment to induce preterm lamb lung maturation, 2) study the influence of maternal leptin treatment in mice on fetal pulmonary surfactant lipid pool size and expression of genes critical for surfactant synthesis, and 3) study whether surfactant homeostasis is altered in ob/ob mice.

METHODS

Protocols were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Cincinnati Children's Research Foundation.

Fetal leptin treatment of sheep.

The effects of fetal leptin treatment on lung maturation were studied using date-mated pregnant ewes. Ewes carrying singletons at 122–124 days gestational age (GA; term: 150 days GA) were gently restrained in the shearing position. Recombinant human leptin (BioVision, Mountain View, CA), 5 mg in 1 ml of 0.9% NaCl, suspended according to the manufacturer's instructions or 1 ml of vehicle, was injected into the shoulder of the fetus using 20-gauge spinal needle with ultrasound guidance (24). Endotoxin level in recombinant human leptin was low and <0.1 ng/μg protein. Three and a half days after injection, preterm lambs were delivered by cesarean section and tracheostomized (24, 38). To induce surfactant secretion at birth and evaluate lung function, preterm newborn lambs were ventilated for 30 min with 100% O2, 4-cmH2O positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP), and 40/min respiratory rate, and tidal volume (VT) was regulated at 6 ml/kg by changing peak inspiratory pressure (PIP) with maximum PIP set at 38 cmH2O, using pressure-limited infant ventilator (Sechrist Industries, Anaheim, CA). VT was monitored (BiCore Monitoring Systems, Anaheim, CA) continuously. A modified ventilation index (MVI) was calculated as (PIP × Pco2 × respiratory rate) ÷ 1,000 (38). Umbilical cord catheter was inserted into the aorta for blood gas, blood pressure, and heart rate recordings and 10% dextrose infusion. At 30 min of age, lambs were given 100 mg of pentobarbital intravascularly, after which the endotracheal tube was clamped to permit oxygen absorption atelectasis. After the thorax was opened, the deflation limb of pressure-volume curve was measured (24, 38). Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) was recovered from the left lung (28), and lung tissue after BAL was homogenized for analysis of surfactant Sat PC, total phospholipid, and total protein. Sat PC was isolated from aliquot of BALF and lung homogenates using osmium tetroxide and neutral alumina (22, 29), followed by phosphorus measurement (17), and Sat PC in the total lung was calculated. Phosphorus in extracted lipid from BALF and lung homogenate was analyzed (17) for total phospholipid. Surfactant proteins (SP) in BALF containing 50 μg of protein was quantified by Western blot analyses using rabbit anti-bovine SP-A, SP-B, and SP-C (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA) and normalized to β-actin in the sample (25). The right upper lobe was inflation-fixed at 30 cmH2O for morphology. Lung tissue of the right lower lobe was frozen in liquid nitrogen for RNA isolation to evaluate surfactant protein mRNAs by quantitative RT-PCR (22).

Maternal leptin treatment of mice.

In the fetal mouse lung, leptin and leptin receptor mRNAs, as well as most genes known to regulate surfactant synthesis, were detectable from embryonic day (E) 14.5 (4, 18, 22). In A/J strain mice, surfactant Sat PC increase dramatically in the fetal lung at late gestation from E18.5, and their term is E21.5. As indicated in Table 1, the pregnant A/J mice were divided into 5 studies by dose of leptin, number of leptin treatment, and gestation age to treat. The protocol of the study 1 (2-dose study) was similar to the previous rat study (27) of maternal leptin treatment, which demonstrated increased fetal lung weight relative to body weight. Recombinant mouse leptin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was suspended in 0.9% NaCl as suggested by the manufacturer, and 30 μg of leptin in 200 μl or same volume of vehicle was injected intraperitoneally to ∼30-g body wt pregnant mouse at the preset gestational age. For high-dose study (study 2), 300 μg of leptin in 240 μl was used. The fetal mouse was delivered by cesarean section under anesthesia with isoflurane inhalation followed by exsanguination by cutting the abdominal aorta of the fetus, and lungs were harvested at the preset gestational ages. Body weight, lung weight, and sex were recorded. The fetal mouse lung was too small for BAL. The lungs were frozen in liquid nitrogen for surfactant Sat PC, total phospholipid analyses, and validation of mRNAs. Quantitative RT-PCR was used to validate surfactant protein mRNAs and several mRNAs related to pulmonary surfactant phospholipid synthesis using TaqMan gene expression assays (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) (22).

Table 1.

Mice maternal leptin treatment studies

| Study Groups | ↓ - Leptin I.P. | ο - Kill | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1) 2-Dose | ↓ | ↓ | ο | ||

| 2) High-dose | ↓ | ↓ | ο | ||

| 3) 3-Dose | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ο | |

| 4) E17.5 | ↓ | ↓ | ο | ||

| 5) E16.5 | ↓ | ↓ | ο | ||

| E14.5 | E15.5 | E16.5 | E17.5 | E18.5 | |

I.P., intraperitoneal injection; E17.5, embryonic day 17.5.

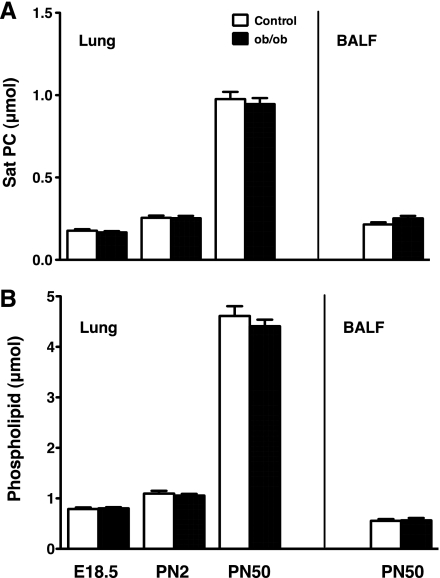

Surfactant lipid in ob/ob mice.

To clarify whether absence of circulating leptin in ob/ob mice influenced surfactant homeostasis, surfactant Sat PC and total phospholipid were analyzed as described above in the lung from fetal (E18.5), postnatal day 2 newborn (PN2), and 7-wk-old (PN50) ob/ob and littermate control mice. BALF were recovered from PN50 mice for surfactant lipid analyses. Ten to twenty-one mice from four litters were studied for each study group.

Data analysis.

Results were given as means ± SE. Comparisons between control and leptin-treated (+Leptin) groups were made with two-tailed unpaired t-tests. Significance was accepted at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Fetal leptin treatment of sheep.

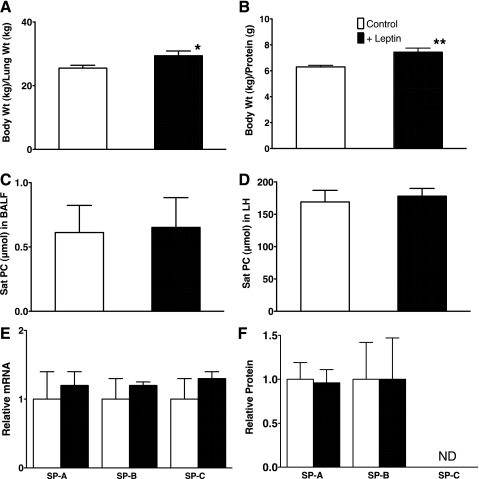

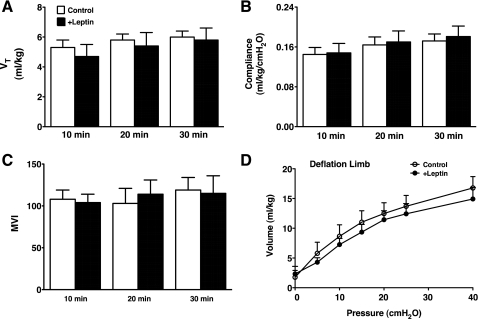

Seven control (4 male, 3 female) and 5 fetal +Leptin lambs (3 male, 2 female) were studied. Cord blood pH of the preterm newborn lambs was normal (control 7.36 ± 0.04, +Leptin 7.35 ± 0.02), and the body weight and lung weight were not different between control and +Leptin groups with some variations among the lambs (body weight: control 3.1 ± 0.3 kg, +Leptin 3.5 ± 0.1 kg, lung weight: control 123 ± 12 g, +Leptin 120 ± 7 g). Total protein in the lung tissue homogenates was similar between groups (control 493 ± 41 mg, +Leptin 471 ± 20 mg). Nevertheless, fetal leptin treatment increased body weight-to-lung weight ratio compared with control (P < 0.03; Fig. 1A). Although total protein (milligrams) in lung homogenate relative to lung weight (grams) was not influenced by leptin treatment (control 4.0 ± 0.1, +Leptin 4.0 ± 0.2), ratio of body weight to protein in lung homogenate was significantly increased by leptin treatment (P < 0.05; Fig. 1B), suggesting increase in body weight by fetal leptin treatment given 3.5 days before delivery. Surfactant Sat PC in BALF and lung homogenate after BALF from control and +Leptin lambs were similarly low (Fig. 1, C and D) and were 1/10 of that of the term fetus. The Sat PC pool size was typical of extremely immature 125–128 days GA preterm lamb lung with surfactant deficiency. The expression of surfactant protein mRNAs was similar for control and +Leptin mice (Fig. 1E). There were no significant differences in SP-A and mature SP-B proteins in BALF between control and +Leptin groups by Western blot (Fig. 1F). Because of the lung immaturity, SP-C was not detectable in BALF from both control and +Leptin groups. Thirty-minute ventilation was regulated according to the study protocol. To maintain target VT of 6 ml/kg (Fig. 2A), high PIP was required for these preterm newborn lambs. PIP was 37 ± 0.5 cmH2O (control) and 37 ± 0.9 cmH2O (+Leptin) at 10 min and 36 ± 0.7 cmH2O (control) and 36 ± 1.1 cmH2O (+Leptin) at 30 min of age, at which time lambs were killed. The lung compliance was extremely low for both control and +Leptin groups (Fig. 2B). The Pco2 was high for both groups throughout 30 min of ventilation, and the final Pco2 was 81 ± 9 mmHg (control) and 83 ± 15 mmHg (+Leptin) and resulted in very high MVI for both groups (Fig. 2C). The Po2 at 30 min were 74 ± 26 mmHg (control) and 64 ± 26 mmHg (+Leptin) with fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) = 1 and were not different between groups. Lung morphology was typical of preterm newborn lambs for both groups with patchy atelectasis and did not show any changes by leptin treatment (data not shown). Deflation limb of pressure-volume curve was similarly low for control and +Leptin groups, and volume at 40 cmH2O was only 15 ml/kg (Fig. 2D). Fetal body weight was increased by leptin treatment, although there was no influence of leptin treatment on pulmonary surfactant synthesis and lung function.

Fig. 1.

A and B: increased body weight by fetal leptin injection of sheep. Body weight-to-lung weight ratio (A) and body weight-to-protein in lung tissue ratio (B) in preterm newborn lamb were increased by fetal leptin injection, suggesting that fetal body weight was increased in leptin-treated (+Leptin) group compared with control. C and D: surfactant-saturated phosphatidylcholine (Sat PC) in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) (C) and lung homogenate after BAL (D) were similarly low for both control and +Leptin groups. Treatment of fetus with leptin did not influence surfactant lipid pool sizes. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005. E: relative expression of surfactant proteins SP-A mRNA, SP-B mRNA, and SP-C mRNA for control and +Leptin groups analyzed by RT-PCR. No changes were demonstrated in surfactant protein mRNAs by fetal treatment with leptin. F: likewise, SP-A and SP-B proteins in BALF analyzed by Western blot were similar between control and +Leptin groups. SP-C in this immature lamb lung of both groups was low and not detectable (ND).

Fig. 2.

Three and a half days after leptin or vehicle injection to the fetus, preterm lambs at 125–128 days were delivered by cesarean section and ventilated for 30 min to evaluate lung function. A: tidal volume (VT) was well-regulated at target of 6 ml/kg by changing peak inspiratory pressure (PIP) and was similar between +Leptin and control groups. B: lung compliance during ventilation was low for both groups. Fetal leptin treatment did not improve lung function of the preterm newborn lamb. C: modified ventilation index (MVI) was calculated as [VT × PIP × respiratory rate (fixed at 40/min)] ÷ 1,000. MVI were similarly high for both control and +Leptin groups, demonstrating the lung immaturity at 125–128 days gestational age. D: the deflation limbs of pressure-volume curves were similarly low for both groups.

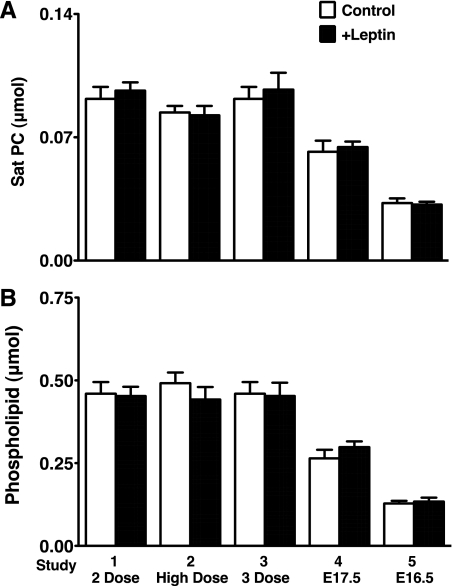

Maternal leptin treatment of mice.

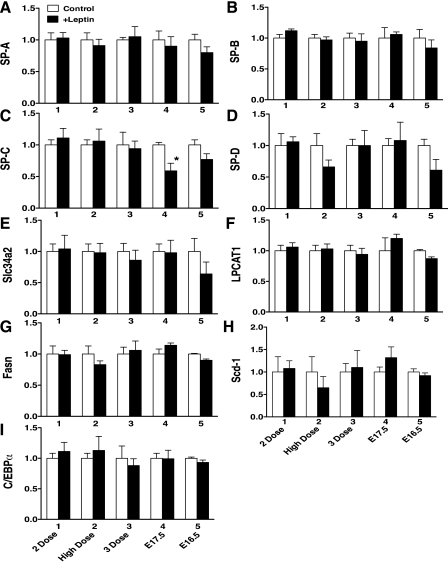

The pregnant mice were given leptin by intraperitoneal injection and studied according to the 5 protocols (Table 1). In our preliminary study of A/J strain mice, Sat PC pool size increased >2-fold from E18.5 to E19.5 and were born around E21.5 without any further changes in Sat PC. To detect the increase in surfactant pool size after leptin treatment, mice were studied on E18.5 or younger before surfactant pool size reached the maximum in the developing mouse lung. The number of preterm mice studied for each group, body weight, and lung weight are shown in Table 2. The body weight and lung weight were slightly increased for +Leptin group mice in study 4 that were given maternal leptin treatment twice on E15.5 and E16.5 and studied on E17.5 (P < 0.05 vs. control). Leptin treatment did not influence surfactant Sat PC synthesis in all 5 studies regardless of gestational age and dose of leptin for treatment (Fig. 3A). Likewise, total phospholipids were similar in control and +Leptin groups for all 5 studies (Fig. 3B). In addition to the surfactant protein mRNAs (Fig. 4, A–D), the selected 5 genes, which were highly expressed in alveolar type II cells and are critically involved in surfactant synthesis, were analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR. Expression of mRNAs in +Leptin mice lungs relative to control mice were presented for each study. Slc34a2 (Fig. 4E) influenced phosphate transport associated with surfactant phospholipid synthesis (17, 22), LPCAT1 (Fig. 4F) had high affinity for palmitoyl-CoA and preferentially acylated lysoPC (5), Fasn (Fig. 4G) and Scd-1 (Fig. 4H) were fatty acid synthase (3), and C/EBPα (Fig. 6I) regulated many genes involved in surfactant biosynthesis. Leptin treatment did not show any influences on SP-A, SP-B, and SP-D mRNAs as well as the expression of mRNAs related to surfactant synthesis. For reasons presently unknown, SP-C mRNA was lower in +Leptin group of study 4, which was analyzed on E17.5.

Table 2.

Maternal leptin treatment to pregnant mice: body weight and lung weight of fetus

|

n |

Body Weight, g |

Lung Weight, mg |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Groups | Control | Leptin | Control | Leptin | Control | Leptin |

| 1) 2-Dose | 18 | 27 | 0.86 ± 0.02 | 0.88 ± 0.01 | 29 ± 2 | 27 ± 4 |

| 2) High-dose | 19 | 20 | 0.84 ± 0.02 | 0.83 ± 0.03 | 30 ± 2 | 30 ± 3 |

| 3) 3-Dose | 18 | 13 | 0.86 ± 0.02 | 0.88 ± 0.04 | 29 ± 2 | 29 ± 2 |

| 4) E17.5 | 22 | 24 | 0.62 ± 0.01 | 0.66 ± 0.02* | 18 ± 1 | 23 ± 1† |

| 5) E16.5 | 22 | 25 | 0.43 ± 0.01 | 0.40 ± 0.02 | 10 ± 1 | 10 ± 1 |

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01.

Fig. 3.

Sat PC (A) and phospholipid (B) in the preterm mouse lung for 5 maternal leptin injection studies (see Table 1). There were no changes in Sat PC and phospholipid by maternal leptin injection to mice given different doses, gestational ages, and number of injections. E17.5, embryonic day 17.5.

Fig. 4.

Expression of surfactant protein genes SP-A (A), SP-B (B), SP-C (C), and SP-D (D) and genes associated with synthesis of surfactant phospholipids in lung from control and +Leptin mice were analyzed by RT-PCR: Slc34a2 (E), LPCAT1 (F), Fasn (G), Scd-1 (H), and C/EBPα (I). No differences were detected between control and +Leptin groups in any of the genes studied except SP-C, which was decreased by leptin treatment in study 4 (*P < 0.05).

Surfactant lipid in ob/ob mice.

Sat PC was analyzed on ob/ob and control mice at the ages of E18.5, PN2, and PN50. The number of mice, body weight, and lung weight are shown in Table 3. The ob/ob mice at E18.5 and PN2 did not show any difference in body weight and lung weight compared with control mice. The increase in body weight of PN50 ob/ob mice was 35% over that of control, whereas the lung weight was only 10% heavier for ob/ob mice than control. Sat PC and phospholipid in the lung (all age groups) and BALF (PN50 group only) were similar between control and ob/ob mice (Fig. 5, A and B). Deficiency of leptin did not influence surfactant Sat PC pool size. Altered lung functions of ob/ob mice were unrelated to surfactant.

Table 3.

Body weight and lung weight of control and ob/ob mice

| E18.5 |

PN2 |

PN50 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | ob/ob | Control | ob/ob | Control | ob/ob | |

| n | 12 | 19 | 11 | 21 | 10 | 15 |

| Body weight, g | 1.31 ± 0.02 | 1.30 ± 0.02 | 1.61 ± 0.06 | 1.62 ± 0.06 | 22.72 ± 0.69 | 35.83 ± 1.13** |

| Lung weight, mg | 42 ± 2 | 43 ± 1 | 33 ± 1 | 32 ± 1 | 313 ± 12 | 346 ± 9* |

P < 0.05. PN2, postnatal day 2 newborn.

P < 0.0001.

Fig. 5.

Sat PC (A) and phospholipid (B) in the lung and BALF [for postnatal day 50 mice (PN50) only] were analyzed for ob/ob and control mice at E18.5, PN2, and PN50 of age. Surfactant lipids were similar between ob/ob and control mice regardless of increased body weight in ob/ob mice (Table 3) at PN50.

DISCUSSION

Pulmonary surfactant is synthesized in alveolar epithelial type II cells and increases as fetal lung matures to prepare for transition to air breathing at birth. Leptin, an adipose tissue-derived peptide hormone (50), regulates multiple physiological functions such as food intake, lipid metabolism, and energy metabolism (6, 15, 35, 47). Leptin was also thought to be one of the promoters of lung development and surfactant production because leptin in fetal plasma (human and sheep) and expression of leptin mRNA in placenta (human and rat) were increased with advancing gestation (7, 16, 18, 40, 49). Leptin increases surfactant proteins (SP-A, -B, and -C mRNAs and SP-A and -B proteins) in E17 fetal rat lung explants in vitro (45). Leptin was secreted from fibroblasts bound to its receptor on the alveolar type II cells and stimulates surfactant phospholipid de novo synthesis in fetal rat lung explants and type II cells in culture (44). The effects of exogenous leptin treatment to increase surfactant lipid synthesis in fetal lung have been proposed but are as yet unknown. We intended to demonstrate beneficial effects of leptin treatment on fetal lung maturation, however, the results of all the in vivo studies were negative. The responses of fetal lung to the leptin treatment might vary by dose, duration, dosing interval, route, gestation age, and species. The doses of leptin used for the present studies were its physiological concentration (1 mg/kg) (20, 27), and these dose ranges of exogenous leptin restored phenotypes of ob/ob mice (8, 11). We carefully designed five studies of maternal leptin treatment to pregnant mice as well as direct fetal leptin injection to sheep. Furthermore, surfactant pool sizes were analyzed on fetus, newborn, and adult ob/ob mice. Neither exogenously given leptin under six treatment protocols for sheep and mice nor deficiency of leptin in ob/ob mice influenced fetal lung maturation or surfactant pool sizes. The key genes highly expressed in alveolar type II cells and critically required for surfactant synthesis were not affected by leptin treatment. This is the first study to demonstrate manifestly that there is no influence of leptin on surfactant synthesis in vivo, at least under our treatment protocols.

The maternal leptin treatment did not show any effects on surfactant pool size in preterm newborn mice, regardless of the 5 conditions under which we studied, including 10-fold higher dose, multiple treatments, and different durations of treatments. There are possible explanations why leptin does not influence surfactant synthesis in vivo. The following mechanisms did not occur in vitro, and surfactant synthesis in rat lung explants and type II cells in culture were increased by leptin (44, 45). One mechanism is the leptin level in fetal serum is controlled by placenta, and increase in maternal plasma leptin by maternal leptin treatment may not increase leptin in fetal plasma and may not induce fetal lung maturation. For example, well-feeding increased maternal plasma leptin in pregnant sheep, whereas fetal leptin concentration was unchanged and not influenced by high level of maternal plasma leptin (31). Another possible factor is that exogenously given leptin to the pregnant mice may be inhibited by soluble leptin-binding proteins (19). Soluble leptin receptor was considered to be one of the key leptin-binding proteins in humans and rodents. Circulating leptin-binding proteins were known to increase in maternal plasma after second trimester and bind to high-level leptin, which altered bioactivity and transport of leptin. Leptin-binding proteins also inhibited clearance of leptin from plasma by filtration in the kidney that resulted in 20-fold increase in both free and bound leptin in plasma (13, 32). High leptin inhibition at near-term increases maternal metabolic efficacy and food intake that was important for delivery and nursing. The majority of exogenously given leptin to pregnant mice may bind with leptin-binding proteins and lose its biological function in vivo. To avoid the above factors that might occur for maternal administration of leptin, we injected leptin directly to the fetus in sheep. Fetal leptin treatment also resulted in no changes in lung maturation or surfactant pool sizes.

Kirwin et al. (27) demonstrated increase in SP-A, -B, and -C mRNA as well as SP-A and -B protein by physiological concentration of leptin (1 and 10 ng/ml) in vitro using E17 fetal rat lung explant. In the same paper, they described additional in vivo study of maternal leptin treatment to pregnant rat with the major finding of a 14% increase in fetal lung weight relative to body weight. In our present study, the lung weight was increased only for E17.5 study (study 4) mice. Fetal lung weight is considerably influenced by fetal lung fluid volume remaining in the airways, and conclusions cannot be drawn on lung maturation from increased lung weight alone. Although increased immunohistochemistry of fetal rat lung for SP-B was included in the rat study, morphological lung maturation, especially larger alveolar space, was not seen in +Leptin group. In addition, lung weight, body weight, lung weight-to-body weight ratio, total protein in the lung tissue, surfactant phospholipids, and surfactant proteins were not presented or analyzed in their in vivo study.

Maternal glucocorticoid treatment has been routinely used for pregnant women with high-risk of preterm delivery. Maternal glucocorticoid treatment slightly increased surfactant phospholipid in rabbit and sheep fetuses, induced lung structural maturation, decreased protein leak, and improved preterm newborn lung function (26). Glucocorticoid response element was identified in the promoter region of the human leptin gene (14), and glucocorticoid was likely to target leptin gene transcription directly in utero. Increased leptin synthesis and secretion by glucocorticoid was demonstrated in fetal adipose tissue in vivo and in vitro. Antenatal glucocorticoid treatment of 130 days GA sheep fetus increased leptin >1.5-fold in fetal circulation, whereas exposure to triiodothyronine did not influence fetal plasma leptin (33). The present study suggested that increased leptin by glucocorticoid treatment may not be the mechanism of induction of lung maturation. On the other hand, increased leptin by glucocorticoid treatment played a role in regulation of body temperature of the preterm newborn (10). In contrast to the single treatment, prolonged multiple maternal glucocorticoid treatment had the opposite effect on fetal plasma leptin level, and whereas maternal plasma leptin was increased, leptin was decreased in fetal plasma (39, 41). Since leptin influenced fetal body weight, decreased leptin in fetus after multiple doses of maternal glucocorticoid treatment caused retarded fetal growth (9, 41). Likewise, in the present study, body weight of preterm newborn lamb was significantly increased by antenatal fetal leptin treatment.

Newborn ob/ob mice do not have any respiratory problems in the transition to air breathing at birth. The explanation was that although ob/ob mice fetuses were unable to produce leptin, these fetuses were exposed to leptin by placental blood flow and lactational sources from the heterozygous ob/+ dams (2, 18, 37, 44). This explanation may be inappropriate because, unlike in humans, the source of the hyperleptinemia of late-gestation in the mouse fetus is mainly from adipose tissue, and the leptin produced by placenta is minimal in mice (16). Leptin levels in ob/ob mice fetuses were very low and not detectable in fetal serum and lung homogenate (13). We also could not detect any leptin by ELISA (Millipore, Billerica, MA) in E18.5 ob/ob fetal mice plasma (data not shown). Nevertheless, surfactant homeostasis was not influenced by deficiency of leptin in fetal and adult ob/ob mice lungs. Homozygous ob/ob mice exhibited subfertility. To make the complete absence of leptin in both the mother and fetus, homozygous ob/ob male and female mice were treated with exogenous leptin to mate in the previous study. The fetus in homozygous ob/ob dam developed normally and delivered with no signs of respiratory problems (30), suggesting that leptin deficiency does not influence fetal lung development. These homozygous ob/ob newborn mice did not survive over a day after delivery due to failure of the dam's lactation. The adult ob/ob mice have depressed respiratory function before pronounced obesity, which was thought to be caused by decreased central respiratory control mechanisms and obesity as well (21, 34, 36). These respiratory problems in ob/ob mice were partially restored by exogenous leptin treatment (34, 42). Whether surfactant synthesis was altered in adult ob/ob mice and, at least partially, contributed to their abnormal pulmonary function is not currently known. The present study demonstrated that Sat PC pool sizes were normal in ob/ob mice at all ages studied, suggesting that leptin was not required for surfactant lipid homeostasis in mice. We conclude from this study that leptin alone does not play a critical role in surfactant synthesis, and exogenously given leptin does not influence fetal lung surfactant synthesis or preterm newborn lung function in vivo.

GRANTS

This work was supported by March of Dimes Foundation Grant 6FY09 235 (M. Ikegami) and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant HL-095464 (M. Ikegami).

DISCLOSURES

None of the authors has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Shawn Grant and Michael Minnick for excellent technical support.

REFERENCES

- 1. Akei H, Whitsett JA, Buroker M, Ninomiya T, Tatsumi H, Weaver TE, Ikegami M. Surface tension influences cell shape and phagocytosis in alveolar macrophages. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 291: L572–L579, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aoki N, Kawamura M, Matsuda T. Lactation-dependent down regulation of leptin production in mouse mammary gland. Biochim Biophys Acta 1427: 298–306, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Besnard V, Wert SE, Kaestner KH, Whitsett JA. Stage-specific regulation of respiratory epithelial cell differentiation by Foxa1. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 289: L750–L759, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Besnard V, Wert SE, Stahlman MT, Postle AD, Xu Y, Ikegami M, Whitsett JA. Deletion of Scap in alveolar type II cells influences lung lipid homeostasis and identifies a compensatory role for pulmonary lipofibroblasts. J Biol Chem 284: 4018–4030, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bridges JP, Ikegami M, Brilli LL, Chen X, Mason RJ, Shannon JM. LPCAT1 regulates surfactant phospholipid synthesis and is required for transitioning to air breathing in mice. J Clin Invest 120: 1736–1748, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Campfield LA, Smith FJ, Guisez Y, Devos R, Burn P. Recombinant mouse OB protein: evidence for a peripheral signal linking adiposity and central neural networks. Science 269: 546–549, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cetin I, Morpurgo PS, Radaelli T, Taricco E, Cortelazzi D, Bellotti M, Pardi G, Beck-Peccoz P. Fetal plasma leptin concentrations: relationship with different intrauterine growth patterns from 19 weeks to term. Pediatr Res 48: 646–651, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chehab FF, Lim ME, Lu R. Correction of the sterility defect in homozygous obese female mice by treatment with the human recombinant leptin. Nat Genet 12: 318–320, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Christou H, Connors JM, Ziotopoulou M, Hatzidakis V, Papathanassoglou E, Ringer SA, Mantzoros CS. Cord blood leptin and insulin-like growth factor levels are independent predictors of fetal growth. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86: 935–938, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Clarke I, Heasman L, Symonds ME. Influence of maternal dexamethasone administration on thermoregulation in lambs delivered by caesarean section. J Endocrinol 156: 307–314, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cleary MP, Bergstrom HM, Dodge TL, Getzin SC, Jacobson MK, Phillips FC. Restoration of fertility in young obese (Lep(ob) Lep(ob)) male mice with low dose recombinant mouse leptin treatment. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 25: 95–97, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ehrhardt RA, Bell AW, Boisclair YR. Spatial and developmental regulation of leptin in fetal sheep. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 282: R1628–R1635, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gavrilova O, Barr V, Marcus-Samuels B, Reitman M. Hyperleptinemia of pregnancy associated with the appearance of a circulating form of the leptin receptor. J Biol Chem 272: 30546–30551, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gong DW, Bi S, Pratley RE, Weintraub BD. Genomic structure and promoter analysis of the human obese gene. J Biol Chem 271: 3971–3974, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Halaas JL, Gajiwala KS, Maffei M, Cohen SL, Chait BT, Rabinowitz D, Lallone RL, Burley SK, Friedman JM. Weight-reducing effects of the plasma protein encoded by the obese gene. Science 269: 543–546, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hassink SG, de Lancey E, Sheslow DV, Smith-Kirwin SM, O'Connor DM, Considine RV, Opentanova I, Dostal K, Spear ML, Leef K, Ash M, Spitzer AR, Funanage VL. Placental leptin: an important new growth factor in intrauterine and neonatal development? Pediatrics 100: E1, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hess HH, Derr JE. Assay of inorganic and organic phosphorus in the 0.1–5 nanomole range. Anal Biochem 63: 607–613, 1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hoggard N, Hunter L, Duncan JS, Williams LM, Trayhurn P, Mercer JG. Leptin and leptin receptor mRNA and protein expression in the murine fetus and placenta. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 11073–11078, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Houseknecht KL, Mantzoros CS, Kuliawat R, Hadro E, Flier JS, Kahn BB. Evidence for leptin binding to proteins in serum of rodents and humans: modulation with obesity. Diabetes 45: 1638–1643, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hsu A, Aronoff DM, Phipps J, Goel D, Mancuso P. Leptin improves pulmonary bacterial clearance and survival in ob/ob mice during pneumococcal pneumonia. Clin Exp Immunol 150: 332–339, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Huang K, Rabold R, Abston E, Schofield B, Misra V, Galdzicka E, Lee H, Biswal S, Mitzner W, Tankersley CG. Effects of leptin deficiency on postnatal lung development in mice. J Appl Physiol 105: 249–259, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ikegami M, Falcone A, Whitsett JA. STAT-3 regulates surfactant phospholipid homeostasis in normal lung and during endotoxin-mediated lung injury. J Appl Physiol 104: 1753–1760, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ikegami M, Jobe AH, Yamada T, Seidner S. Relationship between alveolar saturated phosphatidylcholine pool sizes and compliance of preterm rabbit lungs. The effect of maternal corticosteroid treatment. Am Rev Respir Dis 139: 367–369, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ikegami M, Polk DH, Jobe AH, Newnham J, Sly P, Kohen R, Kelly R. Postnatal lung function in lambs after fetal hormone treatment. Effects of gestational age. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 152: 1256–1261, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ikegami M, Weaver TE, Grant SN, Whitsett JA. Pulmonary surfactant surface tension influences alveolar capillary shape and oxygenation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 41: 433–439, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jobe AH, Ikegami M. Fetal responses to glucocorticoids. In: Endocrinology of the Lung, edited by Mendelson CR. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press, 2000, p. 45–57 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kirwin SM, Bhandari V, Dimatteo D, Barone C, Johnson L, Paul S, Spitzer AR, Chander A, Hassink SG, Funanage VL. Leptin enhances lung maturity in the fetal rat. Pediatr Res 60: 200–204, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem 193: 265–275, 1951 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mason RJ, Nellenbogen J, Clements JA. Isolation of disaturated phosphatidylcholine with osmium tetroxide. J Lipid Res 17: 281–284, 1976 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mounzih K, Qiu J, Ewart-Toland A, Chehab FF. Leptin is not necessary for gestation and parturition but regulates maternal nutrition via a leptin resistance state. Endocrinology 139: 5259–5262, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Muhlhausler BS, Roberts CT, McFarlane JR, Kauter KG, McMillen IC. Fetal leptin is a signal of fat mass independent of maternal nutrition in ewes fed at or above maintenance energy requirements. Biol Reprod 67: 493–499, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nuamah MA, Sagawa N, Yura S, Mise H, Itoh H, Ogawa Y, Nakao K, Fujii S. Free-to-total leptin ratio in maternal plasma is constant throughout human pregnancy. Endocr J 50: 421–428, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. O'Connor DM, Blache D, Hoggard N, Brookes E, Wooding FB, Fowden AL, Forhead AJ. Developmental control of plasma leptin and adipose leptin messenger ribonucleic acid in the ovine fetus during late gestation: role of glucocorticoids and thyroid hormones. Endocrinology 148: 3750–3757, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. O'Donnell CP, Schaub CD, Haines AS, Berkowitz DE, Tankersley CG, Schwartz AR, Smith PL. Leptin prevents respiratory depression in obesity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 159: 1477–1484, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pelleymounter MA, Cullen MJ, Baker MB, Hecht R, Winters D, Boone T, Collins F. Effects of the obese gene product on body weight regulation in ob/ob mice. Science 269: 540–543, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Polotsky VY, Wilson JA, Smaldone MC, Haines AS, Hurn PD, Tankersley CG, Smith PL, Schwartz AR, O'Donnell CP. Female gender exacerbates respiratory depression in leptin-deficient obesity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 164: 1470–1475, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sagawa N, Yura S, Itoh H, Kakui K, Takemura M, Nuamah MA, Ogawa Y, Masuzaki H, Nakao K, Fujii S. Possible role of placental leptin in pregnancy: a review. Endocrine 19: 65–71, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sato A, Whitsett JA, Scheule RK, Ikegami M. Surfactant protein-D inhibits lung inflammation caused by ventilation in premature newborn lambs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 181: 1098–1105, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Smith JT, Waddell BJ. Leptin receptor expression in the rat placenta: changes in ob-ra, ob-rb, and ob-re with gestational age and suppression by glucocorticoids. Biol Reprod 67: 1204–1210, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Spear ML, Hassink SG, Leef K, O'Connor DM, Kirwin SM, Locke R, Gorman R, Funanage VL. Immaturity or starvation? Longitudinal study of leptin levels in premature infants. Biol Neonate 80: 35–40, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sugden MC, Langdown ML, Munns MJ, Holness MJ. Maternal glucocorticoid treatment modulates placental leptin and leptin receptor expression and materno-fetal leptin physiology during late pregnancy, and elicits hypertension associated with hyperleptinaemia in the early-growth-retarded adult offspring. Eur J Endocrinol 145: 529–539, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tankersley CG, O'Donnell C, Daood MJ, Watchko JF, Mitzner W, Schwartz A, Smith P. Leptin attenuates respiratory complications associated with the obese phenotype. J Appl Physiol 85: 2261–2269, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Thomas L, Wallace JM, Aitken RP, Mercer JG, Trayhurn P, Hoggard N. Circulating leptin during ovine pregnancy in relation to maternal nutrition, body composition and pregnancy outcome. J Endocrinol 169: 465–476, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Torday JS, Rehan VK. Stretch-stimulated surfactant synthesis is coordinated by the paracrine actions of PTHrP and leptin. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 283: L130–L135, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Torday JS, Sun H, Wang L, Torres E, Sunday ME, Rubin LP. Leptin mediates the parathyroid hormone-related protein paracrine stimulation of fetal lung maturation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 282: L405–L410, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tsuchiya T, Shimizu H, Horie T, Mori M. Expression of leptin receptor in lung: leptin as a growth factor. Eur J Pharmacol 365: 273–279, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Weigle DS, Bukowski TR, Foster DC, Holderman S, Kramer JM, Lasser G, Lofton-Day CE, Prunkard DE, Raymond C, Kuijper JL. Recombinant ob protein reduces feeding and body weight in the ob/ob mouse. J Clin Invest 96: 2065–2070, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Whitsett JA, Weaver TE. Hydrophobic surfactant proteins in lung function and disease. N Engl J Med 347: 2141–2148, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yuen BS, McMillen IC, Symonds ME, Owens PC. Abundance of leptin mRNA in fetal adipose tissue is related to fetal body weight. J Endocrinol 163: R11–R14, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zhang Y, Proenca R, Maffei M, Barone M, Leopold L, Friedman JM. Positional cloning of the mouse obese gene and its human homologue. Nature 372: 425–432, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]