Abstract

Secretoglobin (SCGB) 1A1, also called Clara cell secretor protein (CCSP) or Clara cell-specific 10-kDa protein (CC10), is a small molecular weight secreted protein mainly expressed in lung, with anti-inflammatory/immunomodulatory properties. Previous in vitro studies demonstrated that CCAAT/enhancer-binding proteins (C/EBPs) are the major transcription factors for the regulation of Scbg1a1 gene expression, whereas FOXA1 had a minimum effect on the transcription. To determine the in vivo role of C/EBPs in the regulation of SCGB1A1 expression, experiments were performed in which A-C/EBP, a dominant-negative form of C/EBP that interferes with DNA binding activities of all C/EBPs, was specifically expressed in lung. Surprisingly, despite the in vitro findings, expression of SCGB1A1 mRNA was not decreased in vivo in the absence of C/EBPs. This may be due to a compensatory role assumed by FOXA1 in the regulation of Scgb1a1 gene expression in lung in the absence of active C/EBPs. This disconnect between in vitro and in vivo results underscores the importance of studies using animal models to determine the role of specific transcription factors in the regulation of gene expression in intact multicellular complex organs such as lung.

Keywords: cc10, lung specific, tetracycline regulation, CCSP, dominant-negative

lung epithelial cells express a number of genes that are critical for the function and homeostasis of the lung. Among them are secretoglobin (SCGB) 1A1, previously called uteroglobin, Clara cell secretory protein (CCSP), or Clara cell specific 10-kDa protein (CC10), and SCGB3A2, previously called uteroglobin-related protein (UGRP) 1. These proteins are the members of the SCGB gene superfamily, comprising secretory proteins of small molecular weight of ∼10 kDa. SCGB1A1 is the most studied among the SCGB family members and serves as an anti-inflammatory agent in lung (18, 20). SCGB3A2 has anti-inflammatory activity and plays a role in lung development (11, 14). Both SCGB1A1 and SCGB3A2 are mainly expressed in airway epithelial Clara cells (10, 22, 28). Their expression is detected at minimum levels during early embryonic days of mouse lung development and markedly increases toward the end of gestation (8, 28). The increase of their expression as development proceeds coincides with increased expression of several transcription factors such as CCAAT/enhancer binding proteins (C/EBP) α/δ, NK2 homeobox 1 (NKX2–1), and/or Forkhead protein (FOX) A1/2, previously called HNF3α/β (5, 8, 28). These transcription factors are expressed in lung epithelial cells and are known to control specific genes preferentially expressed in lung, including SCGB1A1 and SCGB3A2 (22, 28).

The C/EBPs are a family of basic leucine zipper (B-ZIP) transcription factors, consisting of a basic amino acid-containing region at the NH2-terminal half that is necessary for DNA binding and a COOH-terminal leucine zipper region that is required for dimerization (29). Six members of the C/EBP family share similarity in the B-ZIP domain and can homo- and/or heterodimerize with each other to bind specific DNA sequences (21, 29). The C/EBPs are involved in many aspects of cell growth, differentiation, metabolism, and inflammation in a variety of cell types (13, 24). In lung, C/EBPα, C/EBPβ, and C/EBPδ are highly expressed in alveolar Type II and bronchiolar epithelial cells with the different degree of expression depending on the subtypes and/or developmental stages (4, 7, 9, 10, 28). Using a transgenic mouse line specifically expressing C/EBPα in the lung, and a lung-specific C/EBPα conditional null mouse, C/EBPα was demonstrated to play a critical role in later stages of lung development (3, 4, 17).

C/EBPα and/or C/EBPδ regulates Scgb1a1 and Scgb3a2 gene expression through synergistic interaction with NKX2–1, as demonstrated by in vitro experiments such as reporter assays, electrophoretic gel mobility shift analysis, and coimmunoprecipitation (8, 9, 28). Furthermore, FOXA1 and FOXA2 activate Scgb1a1 gene expression (6, 8, 19, 25, 26). The level of enhancement, however, is much smaller compared with C/EBPs and no synergistic activation with NKX2–1 was observed (8). These results suggest that C/EBPs are the far more potent transcription factors in activating the Scgb1a1 gene at least as determined by in vitro analysis.

The in vivo role for C/EBPs in the regulation of Scgb3a2 gene expression in lung was demonstrated using A-C/EBP transgenic mouse (TetO-A-C/EBP) that was crossed with a transgenic mouse expressing the rtTA under the CCSP (SCGB1A1) promoter (called CCSP-rtTA;TetO-A-C/EBP double transgenic mouse) (28). A-C/EBP is a dominant negative C/EBP protein consisting of the C/EBPα leucine zipper dimerization domain and an acidic region that replaces the basic region critical for DNA binding (29). A-C/EBP heterodimerizes with all C/EBP family members through the leucine zipper region of the B-ZIP, and the acidic region forms a coiled coil structure with the basic region of the C/EBP to stabilize the heterodimer and block DNA binding (29). Thus the A-C/EBP reagent provides a useful tool to understand the role of C/EBPs in the transcriptional regulation of a gene in a tissue such as lung where multiple C/EBPs are expressed and can share the same target gene(s). When CCSP-rtTA;TetO-A-C/EBP double transgenic mice were fed Dox for 1 mo, increased levels of A-C/EBP mRNA expression was obtained in lung whereas SCGB3A2 mRNA expression was statistically significantly reduced (28). These results confirmed the conclusion of in vitro studies that C/EBPs play a major role in regulating SCGB3A2 expression in lung.

Using the CCSP-rtTA;TetO-A-C/EBP double transgenic mice, the role of C/EBPs in regulation of SCGB1A1 expression in lung in vivo was examined. Unexpectedly, the expression levels of SCGB1A1 mRNA in lungs of CCSP-rtTA;TetO-A-C/EBP double transgenic mice fed Dox did not decrease compared with wild-type littermates. This could be due to FOXA1 that may have become the main regulator of Scgb1a1 expression under chronic suppression of C/EBPs' activities. These results suggest the importance of in vivo studies in understanding the in vivo regulation of a gene(s).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Mice used in this study were CCSP-rtTA;TetO-A-C/EBP double transgenic mice and CCSP-rtTA and TetO-A-C/EBP monogenic mice. Production and characterization of the CCSP-rtTA;TetO-A-C/EBP mice were previously described (28). Genotyping was carried out by use of the following primers: 5′-CCA CGC TGT TTT GAC CTC CAT AG-3′ and 5′-ATT CCA CCA CTG CTC CCA TTC-3′ for A-C/EBP, and 5′-ACT GCC CAT TGC CCA AAC AC-3′ and 5′-AAA ATC TTG CCA GCT TTC CCC-3′ for CCSP-rtTA. The PCR condition was 94°C, 5 min followed by 35 cycles of 94°C, 15 s, 60°C, 30 s, and 72°C, 15 s. Some groups of mice were fed food containing 200 mg/kg doxycycline (Dox) and others were fed control diet as shown in Fig. 1A. Dox time-course experiments were carried out using 6-wk-old mice. All experiments with mice were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines after approval by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Animal Care and Use Committee.

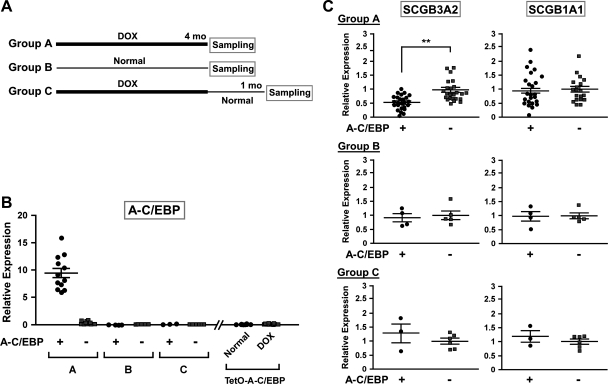

Fig. 1.

Doxycycline (Dox) treatment of A-C/EBP mice. A: scheme for 3 different Dox treatment regimens. For groups A and C, the pups were fed Dox before birth through the mother and feeding continued for 4 mo after birth. Each group consists of mice expressing A-C/EBP (A-C/EBP+) and those not expressing A-C/EBP (A-C/EBP−). B: quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis of A-C/EBP expression in lungs of 3 groups of mice as described in A, as well as TetO-A-C/EBP monogenic mice fed normal chow and Dox diet for 4 mo. Each symbol corresponds to a mouse. C: expression level of SCGB3A2 and SCGB1A1 was analyzed by qRT-PCR. The relative expression levels are expressed based on the mean values (±SD) of wild-type mice as 1. **P < 0.01 by Student's t-test.

qRT-PCR.

Messenger RNAs were measured by quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR). Total RNA was isolated from lung with the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) and RNA concentration was measured. Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from 2 μg of RNA using the Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). qRT-PCR was performed with the cDNA by using the following specific primers: 5′-ACA GGG AGA CGG TTG ATG AG-3′ and 5′-GTT GGG CTT TCT GAC TGC AT-3′ for SCGB3A2, 5′-AAA GCC TCC AAC CTC TAC CA-3′ and 5′-AGG ACT TGA AGA AAT CCT GGG-3′ for SCGB1A1, 5′-GTC ACT GGT CAA CTC GAG GA-3′ and 5′-AGT CGG TGG ACA AGA ACA GC-3′ for C/EBPα, 5′-GGC CCG GCT AGA CAG TTA C-3′ and 5′-GTT TCG GGA CTT GAT GCA AT-3′ for C/EBPβ, 5′-ATG TTG GGT GTG AGG AGA GC-3′ and 5′-TCT TTG CCC TCT GCA GTT CT-3′ for C/EBPδ, 5′-GTG CTT TGG ACT CAT CGA CA-3′ and 5′-GTC CTC GGA AAG ACA GCA TC-3′ for NKX2–1, 5′-TGG TCA TGG TGT TCA TGG TC-3′ and 5′-GGA ACA GCT ACT ACG CGG AC-3′ for FOXA1, 5′-TTC ATG TTG CTC ACG GAA GA-3′ and 5′-CGG CCA GCG AGT TAA AGT AT-3′ for FOXA2, and 5′-ATG GAG GGG AAT ACA GCC C-3′ and 5′-TTC TTT GCA GCT CCT TCG TT-3′ for β-actin as normalization control. The primers for A-C/EBP were the same as those used for genotyping. qRT-PCR condition used was as follows: denaturation at 95°C for 15 s and annealing and extension at 60°C for 60 s for 40 cycles. All data were calculated by the ΔΔCt method with β-actin as normalization control. The mean value (±SD) of A-C/EBP− (wild-type) mice or control vector was set as 1. Statistical analysis was carried out with GraphPad Prism5 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Transfection analysis.

Luciferase reporter assay was carried out by using COS-1 cells that were cultured in DMEM high glucose with l-glutamine (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. Cells were seeded in 24-well tissue culture plates. A transfection mixture contained 20 μl of serum-free OPTI-MEM (Invitrogen), 1 μl of FuGENE 6 (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN), and various amounts of pGL4.11-based reporter construct (Promega, Madison, WI), pSV-β-Gal Control vector (Promega) as an internal control, and a mammalian expression vector (pcDNA3.1, Invitrogen) for C/EBPα, C/EBPδ, FOXA1, FOXA2, or A-C/EBP. The total DNA amount was adjusted by adding pcDNA3.1 vector. This transfection mixture was added to a well and mixed briefly, and cells were incubated for 48 h. Cells were washed once with PBS and lysed with Reporter Lysis Buffer (Promega). Luciferase activity was assayed by using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega), and β-galactosidase activity was assayed with the β-galactosidase Enzyme Assay System (Promega). Relative luciferase activity was expressed after normalization to that of β-galactosidase.

Transfection of mtCC cells was carried out as follows: mtCC cells were seeded in six-well tissue culture plates. A transfection mixture contained 100 μl of serum-free OPTI-MEM (Invitrogen), 5 μl of FuGENE 6 (Roche Applied Science), 1 μg of pcDNA3.1-A-C/EBP mammalian expression vector, or 1 μg of pcDNA3.1 vector as a control. This transfection mixture was added to a well and mixed briefly, and cells were incubated for 48 h. Cells were washed once with PBS and total RNA was isolated by use of the TRIzol reagent.

Nuclear extract preparation.

Nuclear extracts were prepared from C/EBPα, C/EBPδ, FOXA1, and/or A-C/EBP-transfected COS-1 cells. Briefly, cells were grown in 150-mm dishes to 50–80% confluence. Serum-free DMEM (1 ml) containing expression constructs (20 μg) was mixed with 50 μl of FuGENE HD (Roche Applied Science), was let stand for 15 min at room temperature, and was added dropwise to cells. Media were changed 8 h after transfection and cells were cultured for additional 48 h before harvest. Harvested cells were subjected to preparation of nuclear extract by using the NXTRACT CelLytic Nuclear Extraction Kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and the recommended protocol. The protein concentration of nuclear extract was determined by Bradford protein assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) with BSA as a standard. The final concentration was adjusted to 2 mg/ml.

EMSA.

EMSA was carried out as described (1). Briefly, synthetic oligonucleotides were radiolabeled with [γ-32P]ATP (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) and T4 polynucleotidekinase. Labeled oligonucleotide (1 μl containing 0.1 pmol, 2 × 105 cpm/μl) and nuclear extract (1 μl or 2 μg protein) were mixed in a total of 20 μl of binding buffer [0.1 μg/μl poly(dI-dC), 10 mM Tris·HCl, pH 8.0, 1 mM DTT, 80 mM KCl, 20% glycerol, 0.04 μg/μl BSA] and incubated 15 min at room temperature in the presence or absence of 50× excess of cold competitor. For antibody supershift analysis, 0.4 μg each of anti-C/EBPα (sc-61, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), anti-C/EBPδ (sc-151, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), or anti-FOXA1 antibody (Seven Hills Bioreagents, Cincinnati, OH) was added to the sample solution prior to the probe. Normal rabbit IgG (sc-2027, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was used as a nonrelated antibody. Samples were electrophoresed on a 4% polyacrylamide gel using 0.5× TBE buffer. Gels were dried and exposed to phosphoimager screen and signals detected with Storm 840 (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ).

Western blotting.

Nuclei prepared from transfected COS-1 cells by using NXTRACT CelLytic NuCLEAR Extraction Kit (Sigma-Aldrich), or whole lung tissues were homogenized in ice-cold buffer containing 350 mM Tris·HCl, pH 6.8, 10.28% SDS, 600 mM DTT, 0.012% bromophenol blue, and 30% glycerol. Two to 20 μl of total nuclear extract/homogenate were separated by SDS-PAGE on a 4–15% gradient polyacrylamide gel (Bio-Rad Laboratories) and were transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (GE Healthcare). The membrane was incubated in TBS (Tris-buffered saline: 25 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, pH 7.4, KD Medical, Columbia, MD) containing 5% skim milk for 1 h and incubated with rabbit anti-SCGB1A1 (CC10) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-SCGB3A2 (22), anti-C/EBPα, C/EBPβ, and C/EBPδ (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), or mouse anti-FOXA1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) antibody. The membrane was washed with TBS containing 0.05% Tween 20, followed by an hour incubation with a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-linked secondary antibody (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). The membrane was washed three times (10 min each) with 0.05% Tween 20/TBS and then washed an additional two times (5 min each) with TBS. Labeled proteins were visualized by using a SuperSignal West Pico Substrate (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). Signals were detected by using Classic Blue Autoradiography Film BX (MIDSCI, St. Louis, MO) and FluorChem HD2 imaging instrument (Cell Biosciences, Santa Clara, CA).

Immunohistochemistry.

Lungs were fixed in 10% buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin; 4-μm sections were mounted on glass slides and deparaffinized through xylene and rehydrated through a series of graded ethanol. To demonstrate colocalization of four different proteins, mirror and serial sections were coimmunostained for SCGB1A1 and C/EBPα, C/EBPδ, or FOXA1. Immunohistochemistry was also carried out for CYP2F2 to demonstrate the integrity of lung epithelia. Double immunostaining was performed as follows: at first, the sections were rinsed with 0.05% Triton-X 100 in PBS, and nonspecific binding sites were blocked using 10% normal goat serum, 0.05% Tween 20, and 3% skim milk in PBS before incubation with a primary antibody. The sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with rabbit anti-SCGB1A1 (CC10) antibody (Severn Hills Bioreagents) as the primary antibody in a humidified chamber. After being rinsed three times in PBS for 15 min, the tissues were incubated with alkaline phosphatase anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) (AP-1000, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 60 min. Following three additional 15-min rinses in PBS, fast red substrate chromogen system (K0597, DAKO, Carpinteria, CA) was used to visualize specific immunoreactive staining for SCGB1A1. To block cross-reactivity between sequential rounds of staining, sections were autoclaved at 121°C for 5–20 min in Tris-EDTA buffer (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA-Na, pH 9.0). This process inactivated all remaining activities of primary and alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary antibodies. After heating, all slides were cooled down for at least 30 min to room temperature, and the sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with C/EBPα, C/EBPδ, or FOXA1 (Seven Hills Bioreagents) antibody as the primary antibody. The tissues were rinsed three times in PBS for 15 min, incubated with HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) as the secondary antibody, and immune complexes visualized using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) as substrate with hematoxylin counterstaining. Immunostaining with a single primary antibody was visualized by use of DAB and counterstained with hematoxylin.

RESULTS

Effect of loss of C/EBPs activities on SCGB3A2 and SCGB1A1 mRNA expression in vivo.

CCSP-rtTA;TetO-A-C/EBP double transgenic and CCSP-rtTA mice as control were subjected to three feeding regimens to control the levels of A-C/EBP expression (Fig. 1A). The CCSP-rtTA mice were the littermates of CCSP-rtTA;TetO-A-C/EBP mice after interbreeding of TetO-A-C/EBP and CCSP-rtTA mice. The CCSP-rtTA;TetO-A-C/EBP (tentatively called A-C/EBP+) is a tetracycline-regulated transgenic mouse line that expresses a dominant negative A-C/EBP only in the presence of Dox in an airway specific fashion under the control of CCSP (SCGB1A1) gene promoter (28). A-C/EBP inhibits the DNA binding of all C/EBP family members and therefore is useful to understand the consequences of lack of all C/EBPs (29). This is important because many tissues including lung, express multiple forms of C/EBPs. Breeder pairs of both A-C/EBP+ and the littermate CCSP-rtTA mice (A-C/EBP−) were fed a Dox-containing or normal diet, and after birth the pups were continuously fed Dox or normal diet for 4 mo as shown in Fig. 1A; group A mice were continuously fed Dox for 4 mo, group C mice were first fed Dox for 4 mo followed by a normal diet for 1 mo, and group B mice were fed normal diet throughout the experimental period of 4 mo, serving as control. Group A and B mice and group C mice were subjected to gene expression analysis at 4 and 5 mo old, respectively. When RNAs purified from lungs of these mice were subjected to qRT-PCR, high levels of A-C/EBP mRNA expression were detected only with A-C/EBP+ mice continuously fed Dox for 4 mo (Fig. 1B). Other groups of mice, regardless of genotype or feeding regimen, had no or almost no expression of A-C/EBP. To demonstrate that the increased expression of A-C/EBP mRNA in A-C/EBP+ mice was dependent on their exposure to Dox, TetO-A-C/EBP monotransgenic mice were subjected to normal and Dox chow for 4 mo. A-C/EBP expression was not observed in either chow-fed mice (Fig. 1B). The A-C/EBP+ mice fed Dox for 4 mo looked healthy throughout the experimental period. However, ∼25% of them were found to have emphysematous lungs in part of the lobes as revealed when they were killed at 4 mo of age (data not shown). The apparent defective lungs were omitted from further analysis.

Lung RNAs from different groups were used to determine the expression levels of SCGB3A2 and SCGB1A1 mRNAs. SCGB1A1 is the prototypical protein of the gene superfamily to which SCGB3A2 belongs to (Fig. 1C). Both genes were chosen because their expression is regulated by C/EBPα αnd C/EBPδ as revealed by in vitro transfection studies (8–10, 28). The in vivo downregulation of SCGB3A2 mRNA by C/EBPs was previously demonstrated by studies using A-C/EBP mice fed Dox (28), in agreement with the present results with group A (Fig. 1C). Interestingly, the expression of SCGB1A1 mRNA did not change in A-C/EBP+ mice compared with A-C/EBP− mice, both fed Dox. This result was unexpected because, in in vitro transfection experiments, C/EBPα and C/EBPδ are clearly the major transcription factors regulating Scgb1a1 gene expression (8–10). In groups B and C mice, the levels of SCGB3A2 and SCGB1A1 mRNAs were similar between A-C/EBP+ and A-C/EBP− mice (Fig. 1C). In TetO-A-C/EBP monotransgenic mice that have no expression of A-C/EBP, the levels of SCGB3A2 and SCGB1A1 mRNAs remained the same between normal and Dox-fed mice (data not shown).

Expression of various genes in the absence of C/EBPs activities in lung in vivo.

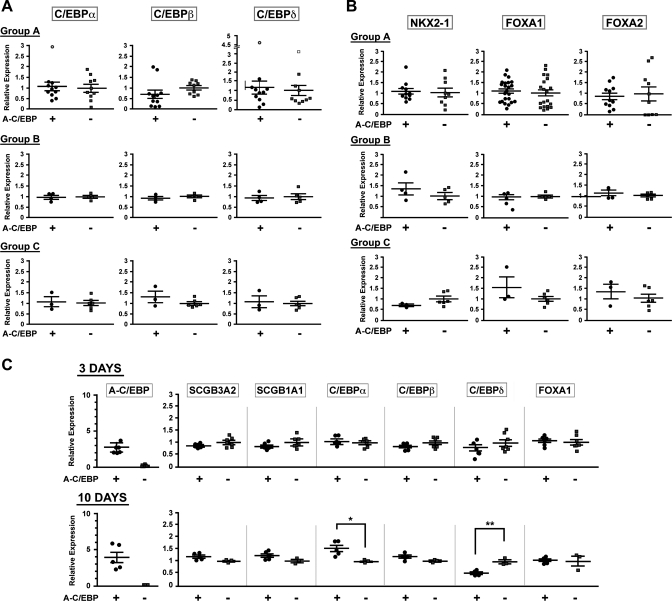

Several transcription factors other than C/EBPα and C/EBPδ, notably C/EBPβ, NKX2–1, FOXA1, and FOXA2, are expressed in lung epithelial cells and/or are known to be involved in the regulation of Scgb3a2 and/or Scgb1a1 gene expression (2, 6, 8, 22, 25, 26, 28). RNAs from lungs of three groups of mice with and without Dox treatment were subjected to qRT-PCR analysis to examine the expression levels of all six transcription factors (Fig. 2). The results demonstrated that the mRNA levels of all transcription factors were similar between A-C/EBP+ and A-C/EBP− mice in all three groups when measured at the age of 4 or 5 mo for mice maintained under the scheme shown in Fig. 1A (Fig. 2, A and B). Under short-term Dox exposure, A-C/EBP expression was already highly elevated after 3 days in A-C/EBP+ mice; however, there were no differences in the levels of SCGB3A2, SCGB1A1, C/EBPs, and FOXA1 mRNAs between A-C/EBP+ and A-C/EBP− mice (Fig. 2C). After 10 days of Dox exposure, A-C/EBP mRNA levels in A-C/EBP+ mice further increased, which continued for up to 4 mo (see Figs. 2C and 1B). Despite of the increase of A-C/EBP expression, the expression of SCGB3A2, SCGB1A1, C/EBPβ, and FOXA1 mRNAs stayed at similar levels at day 10 between A-C/EBP+ and A-C/EBP− mice, whereas C/EBPα and C/EBPβ mRNA levels were statistically up- and downregulated in A-C/EBP+ mice compared with A-C/EBP− mice. These results suggested that A-C/EBP expression does not immediately affect the levels of SCGB3A2 and SCGB1A1 mRNA. Furthermore, the inhibition of C/EBPs' activities at the DNA binding level in vivo may lead to the different expression status for C/EBP mRNAs depending on the length of Dox exposure.

Fig. 2.

Expression of transcription factors in lungs of A-C/EBP mice. The same mouse lungs used for Fig. 1 were subjected to qRT-PCR analysis of C/EBPα, C/EBPβ, and C/EBPδ (A) and NKX2–1, FOXA1, and FOXA2 expression (B). In A, open circles and open squares are outliers (one for C/EBPα in group A, and one circle and one square for C/EBPδ in group A) as determined by GraphPad, Grubbs' test. Status for the “no statistically significant difference” between A-C/EBP+ and A-C/EBP− groups remained the same even after disregarding these points. C: time course for the expression of genes indicated in A-C/EBP+ or A-C/EBP− mice after start of Dox diet. Each symbol corresponds to a mouse. The relative expression levels are expressed based on the mean values (±SD) of wild-type mice as 1. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 by Student's t-test.

In vitro expression of SCGB1A1 in the absence of C/EBPs activities.

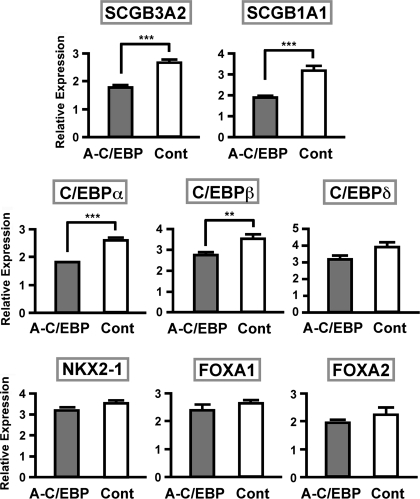

To gain insight into the in vivo effect of the loss of C/EBPs activities in A-C/EBP+ mice fed Dox, mtCC cells were transiently transfected with a A-C/EBP plasmid and qRT-PCR was carried out to determine the expression levels of mRNAs for SCGB1A1, SCGB3A2, and the aforementioned six transcription factors, C/EBPα, C/EBPβ, C/EBPδ, NKX2–1, FOXA1, and FOXA2 (Fig. 3). The mtCC is a cell line derived from transformed mouse Clara cells in which the SV40 large T antigen is expressed under the control of the Scgb1a1 promoter (16). This cell line constitutively expresses all genes described herein (16, 28). The results revealed that SCGB3A2, SCGB1A1, C/EBPα, and C/EBPβ mRNA levels were statistically significantly lower in the presence of A-C/EBP plasmid compared with control vector, whereas the levels of other transcription factors C/EBPδ, NKX2–1, FOXA1, and FOXA2 were not statistically different, although there was a trend of reduced C/EBPδ mRNA expression upon A-C/EBP addition. These results demonstrated that in the transient expression system in mtCC cells, A-C/EBP significantly downregulated the expression of C/EBPs, leading to the reduced mRNA expression of SCGB3A2 and SCGB1A1, the known C/EBP's target genes (8, 10, 28). Thus, at least at the level of SCGB1A1 expression, the effect of transient expression of A-C/EBP appeared to be different from that of its long-term expression in vivo, through which C/EBPs' activities were constantly suppressed.

Fig. 3.

Expression levels of various genes after transfection of A-C/EBP plasmid into mtCC cells. Expression levels were determined by qRT-PCR and compared between those transfected with A-C/EBP and control plasmid. Results are means of 3 independent experiments ± SD. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005 by Student's t-test.

In vitro transfection analysis of the Scgb1a1 promoter.

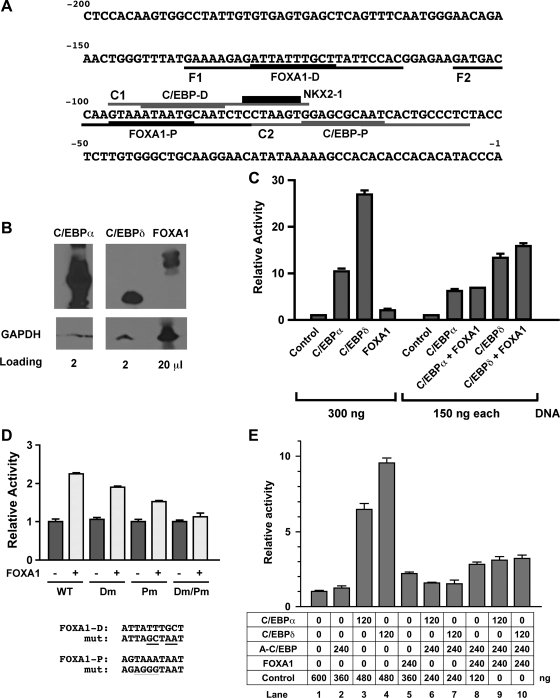

To understand a possible mechanism for the difference between the in vivo and the in vitro results, the promoter sequences of Scgb1a1 and Scgb3a2 genes were examined. Both genes are regulated by C/EBPs according to in vitro studies (8–10, 28). Within −506 bp of the mouse Scgb3a2 gene promoter, several C/EBP and two NKX2–1 binding sites were identified, whereas no FOXA binding sites were found as demonstrated by previous studies (28). In contrast, within −150 bp of the −457 bp Scgb1a1 gene upstream sequences, two FOXA, two C/EBP, and one NKX2–1 binding sites were identified using the AliBaba2.1 program (http://labmom.com/link/alibaba_2_1_tf_binding_prediction) and as described (10) (Fig. 4A). The sites were similar to those previously reported (8, 10, 25, 26). Analysis of the promoter sequences suggested the possibility that FOXAs may underlie the difference between the in vivo and the in vitro results found in Scgb1a1 gene expression.

Fig. 4.

Luciferase reporter analysis of Scgb1a1 promoter activity. A: mouse Scgb1a1 gene promoter sequence up to −200 bp. Binding sites for transcription factors are as follows: C/EBP proximal (C/EBP-P), C/EBP distal (C/EBP-D), FOXA1 proximal (FOXA1-P), FOXA1 distal (FOXA1-D), and NKX2–1. Oligonucleotide sequences used for EMSA are F1, F2 containing FOXA1-D and FOXA1-P site, respectively, and C1, C2 containing C/EBP-D and C/EBP-P site, respectively. B: nuclear extracts were prepared from COS-1 cells transfected with C/EBPα, C/EBPδ, or FOXA1 expression plasmids and subjected to SDS-PAGE in duplicate, followed by Western blotting. After 1 membrane was cut into 4 sections containing only 1 loaded lane, each membrane was incubated with either anti-C/EBPα, C/EBPδ, or FOXA1. A duplicate blot was incubated with anti-GAPDH antibody that served as a loading control. The amount of samples loaded in each well is as follows: 2 μl for C/EBPα, 2 μl for C/EBPδ, and 20 μl for FOXA1. A gap was introduced between C/EBPα and C/EBPδ lanes because the original membrane contained another sample that was not included in this figure. C: COS-1 cells were cotransfected with the −457 Scgb1a1-luciferase reporter construct (300 ng) with various expression plasmids in the pcDNA 3.1 (vector) singly or in combination as indicated. D: COS-1 cells were cotransfected with −457 Scgb1a1-luciferase construct (300 ng) containing no (WT) or various FOXA1 binding site mutations as indicated together with (+) or without (−) FOXA1 expression plasmid (300 ng). Dm, FOXA1-D binding site mutant; Pm, FOXA1-P binding site mutant. Mutated (mut) sequences are shown at bottom. E: COS-1 cells were cotransfected with −457 Scgb1a1-luciferase reporter construct (300 ng) with various expression plasmids singly or in combination as indicated. Luciferase activity is mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments and is expressed based on that of the control vector as 1.

Transient transfection analysis was carried out to confirm that C/EBPs and FOXAs can bind to the Scgb1a1 gene promoter. C/EBPα, C/EBPδ, and FOXA1 were chosen for this study. Expression plasmids were transfected singly or in combination into COS-1 cells to determine Scgb1a1 gene promoter activities using a luciferase reporter plasmid harboring −457 bp of the mouse Scgb1a1 gene promoter (Fig. 4). COS-1 cells do not express any of the following transcription factors: NKX2–1, C/EBPα, C/EBPβ, C/EBPδ, FOXA1 and FOXA2. Since we tested for binding of FOXA1 to the FOXA binding sites (see below), they were denoted as FOXA1 binding sites (Fig. 4A). Of interest is that the distal C/EBP binding site (C/EBP-D) partially overlapped with the proximal FOXA1 binding site (FOXA1-P).

After transfection into COS-1 cells, the levels of expressed proteins were C/EBPα > C/EBPδ >>> FOXA1 as determined by Western blotting (Fig. 4B). Note that although this may not represent the absolute amounts expressed due to different antibodies used, the differences are sufficiently large made by this semiquantitative determination using GAPDH as a loading control. In the transfection system, C/EBPδ enhanced the promoter activity over 25-fold compared with vector only, whereas C/EBPα exhibited about half the activity of C/EBPδ (Fig. 4C, left 5 lanes). On the other hand, FOXA1 only slightly increased promoter activity compared with vector only. The combination of FOXA1 with C/EBPα or C/EBPδ had a marginal additive effect on the promoter activity (Fig. 4C, right lanes). Taken together with the Western blotting results, C/EBPδ may be the most efficient transcription factor among those examined in enhancing Scgb1a1 promoter activity (Fig. 4, B and C). The results are in good agreement with those previously reported, demonstrating that C/EBPα and C/EBPδ play a major role in Scgb1a1 gene transcription as determined by in vitro transfection analysis (8, 10). However, considering the amount of expressed FOXA1, which is ∼1/10 that of C/EBPα, FOXA1 could be as efficient a transcription factor as C/EBPα in regulating the Scgb1a1 promoter.

The role of FOXA1 in Scgb1a1 promoter activity was further analyzed by using various binding site mutants in cotransfection analysis (Fig. 4D). The distal FOXA1 binding site (FOXA1-D) mutant exhibited about 20–30% reduced promoter activity compared with wild type whereas the proximal FOXA1 binding site (FOXA1-P) mutant showed about a half the activity of wild type. Both mutations together almost abolished the promoter activity. These results demonstrated that the proximal FOXA1 binding site was most responsible for promoter activity; however, both binding sites were required for FOXA1-enhanced promoter activity of the mouse Scgb1a1 gene as previously described (6, 8, 19, 25, 26).

To gain insight into how the presence of A-C/EBP affects Scgb1a1 promoter activity, cotransfection analysis was carried out using expression plasmids for C/EBPα or C/EBPδ, and A-C/EBP and FOXA1 singly or in various combinations (Fig. 4E). C/EBPα or C/EBPδ-enhanced promoter activity was almost completely suppressed by the addition of a twofold excess of the A-C/EBP expression plasmid (lanes 2, 3, 4, 6, 7). When expression plasmids for C/EBPα or C/EBPδ, and A-C/EBP and FOXA1 were added together, promoter activity was increased approximately twofold relative to the level of C/EBPα or C/EBPδ and A-C/EBP combined (lanes 6 and 7 vs. lanes 9 and 10), which was similar to or slightly higher than the level obtained by FOXA1 alone or with A-C/EBP (lanes 5 and 8). These results suggested that, in the presence of A-C/EBP, the transcriptional activity of C/EBPα or C/EBPδ is suppressed whereas FOXA1 stays as an active transcription factor.

DNA binding activities of C/EBPs and FOXA1.

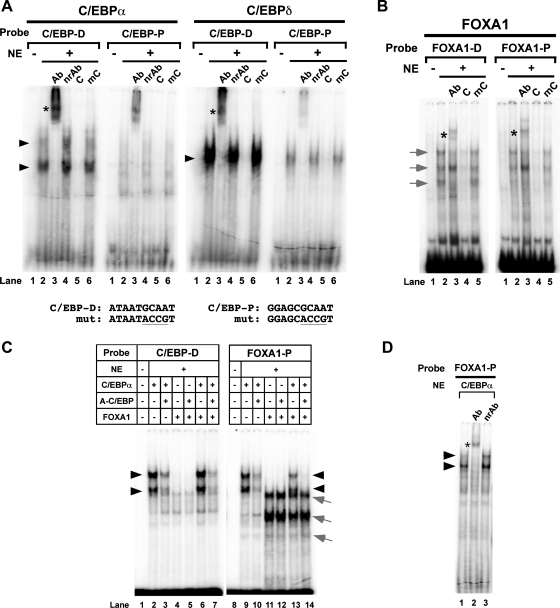

To demonstrate that C/EBPα/δ and FOXA1 bind to their cognate binding sites in the Scgb1a1 promoter, EMSA DNA binding analysis was carried out by using the same amounts (volume and protein concentration) of nuclear extracts similarly prepared from COS-1 cells transfected with C/EBPα, C/EBPδ, or FOXA1 expression plasmid (Fig. 5). Although both C/EBPα and C/EBPδ bound to the proximal (C/EBP-P) and distal C/EBP (C/EBP-D) binding sites, the C/EBP-D site appeared far more preferential than the C/EBP-P site for both C/EBPs (Fig. 5A). Because C/EBPα was expressed slightly more than C/EBPδ (see Fig. 4B), the binding of C/EBPδ appeared to be much stronger than C/EBPα to their specific binding site. This would account for the stronger promoter activity of C/EBPδ observed in transient transfection analysis (see Fig. 4C). On the other hand, FOXA1 bound to both proximal (FOXA1-P) and distal (FOXA1-D) sites at similar extent (Fig. 5B). In all cases, the specific DNA-protein shifted band was supershifted by a specific antibody (lane 3), but not by a nonrelated antibody (C/EBPs only, lane 4), and competed out by unlabeled cognate oligonucleotide (lane 5 for C/EBPs and lane 4 for FOXA1), but not mutated oligonucleotide (lane 6 for C/EBPs and lane 5 for FOXA1). These results demonstrated that all C/EBPα, C/EBPδ, and FOXA1 bind to their specific binding sites within −150 bp of the mouse Scgb1a1 gene promoter.

Fig. 5.

EMSA analysis of C/EBP and FOXA1 binding sites of mouse Scgb1a1 gene promoter. Nuclear extracts (NE) prepared from COS-1 cells transfected with C/EBPα (A, left), C/EBPδ (A, right), or FOXA1 (B) expression plasmid were subjected to EMSA with various additives as follows. A: C/EBP-D or C/EBP-P site-containing probe with nuclear extract prepared from control vector-transfected COS-1 cells (lane 1; NE−), or nuclear extract prepared from C/EBPα or C/EBPδ expression plasmid-transfected COS-1 cells (lanes 2–6; NE+) in the presence of specific antibody (lane 3; Ab), nonrelated antibody (lane 4; nrAb), cognate oligonucleotide as competitor (lane 5; C), or mutated oligonucleotide as competitor (lane 6; mC). Mutated sequences for C/EBP-D and C/EBP-P binding sites are shown at the bottom. B: FOXA1-D or FOXA1-P site-containing probe with nuclear extract prepared from control vector-transfected COS-1 cells (lane 1; NE−), or nuclear extract prepared from FOXA1 expression plasmid-transfected COS-1 cells (lanes 2–5; NE+) in the presence of specific antibody (lane 3; Ab), cognate oligonucleotide as competitor (lane 4; C), or mutated oligonucleotide as competitor (lane 5; mC). Sequences for the mutated oligonucleotides for FOXA1-D and FOXA1-P are shown in Fig. 4D. C: EMSA was carried out with use of nuclear extracts prepared from transfected COS− cells with control vector (lane 1; NE−) or various combinations of expression plasmids (lanes 2–7; NE+) as indicated. D: EMSA was carried out with use of FOXA1-P site-containing probe and a nuclear extract prepared from C/EBPα expression plasmid-transfected COS-1 cells in the absence (lane 1) or the presence of anti-C/EBPα antibody (lane 2) or nonrelated antibody (lane 3). Black arrowheads indicate a C/EBP-specific DNA-protein shifted band; gray arrows indicate a FOXA1-specific DNA-protein shifted band. Asterisks show antibody supershifted bands. Antibodies used for supershift analysis were as follows: anti-C/EBPα (sc-61, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-C/EBPδ (sc-151, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-FOXA1 (Seven Hills Bioreagents) and normal rabbit IgG as nonrelated antibody (sc-2027, Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

EMSA was further used to demonstrate the effect of A-C/EBP on the binding of C/EBPα and FOXA1 to their specific binding sites (Fig. 5C). With the C/EBP-D site-containing probe, the intensity of C/EBPα-specific shifted bands (Fig. 5C, lane 2) decreased in the presence of A-C/EBP (Fig. 5C, lane 3), confirming that A-C/EBP interferes with C/EBP's binding to the specific binding site. The weak C/EBPα-specific bands remained in the presence of A-C/EBP. FOXA1 did not bind to the C/EBP-D site-containing probe with or without A-C/EBP even though the binding site partially overlaps (Fig. 5C, lanes 4 and 5). The presence of FOXA1 did not further change the pattern and intensity of C/EBPα's binding to its specific binding site in the presence and absence of A-C/EBP (Fig. 5C, lanes 6 and 7). In contrast, C/EBPα was able to bind to FOXA1-P containing probe (Fig. 5C, lane 9). This binding was again incompletely inhibited by A-C/EBP (Fig. 5C, lane 10). The binding of C/EBPα to the FOXA1-P binding site was considered genuine because anti-C/EBPα antibody supershifted the bands (Fig. 5D). FOXA1 produced the expected shifted bands with the FOXA1-P probe, which was not affected by A-C/EBP (Fig. 5C, lanes 11 and 12). When C/EBPα and FOXA1 were added together, both transcription factors bound to the FOXA1-P site (Fig. 5C, lane 13). Interestingly, in the presence of A-C/EBP, C/EBPα-specific bands completely disappeared whereas FOXA1-specific bands remained the same (Fig. 5C, lane 14). These results demonstrated that A-C/EBP interferes with C/EBP's binding to the specific binding site, whereas it does not affect FOXA1's binding to its specific binding site.

Analysis of A-C/EBP mouse lungs.

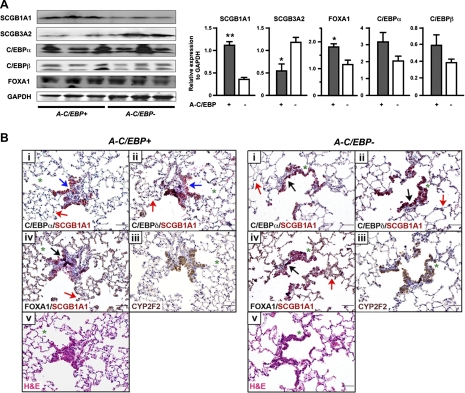

The in vivo effect of A-C/EBP on the expression of SCGB3A2, SCGB1A1, and transcription factors C/EBPα, C/EBPβ, and FOXA1 proteins was examined by Western blotting in lungs of A-C/EBP+ and A-C/EBP− mice fed Dox for 4 mo (Fig. 6A). The expression of SCGB3A2 protein was decreased to about one-half in A-C/EBP+ mice fed Dox compared with A-C/EBP− mice, which was in good agreement with the mRNA levels shown in Fig. 1C. SCGB1A1 protein expression was almost threefold higher in A-C/EBP+ mice than that of A-C/EBP− mice, both fed Dox. Since SCGB1A1 mRNA levels did not change between A-C/EBP+ and A-C/EBP− mice (see Fig. 1C), the Western blotting results suggest the involvement of protein stabilization and/or the increase in translation of SCGB1A1 protein. The FOXA1 level was increased in A-C/EBP+ mice compared with A-C/EBP− mice with statistical significance whereas C/EBPα and C/EBPβ showed a trend of increased expression in A-C/EBP+ mice compared with A-C/EBP− mice (Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6.

Analysis of A-C/EBP+ mouse lungs fed Dox for 4 mo. A: Western blotting for the expression of SCGB1A1, SCGB3A2, C/EBPα, C/EBPβ, and FOXA1 using proteins prepared from lungs of A-C/EBP+ and A-C/EBP− mice fed Dox for 4 mo. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Left: results from 3 mice in each genotype are shown. Both C/EBPα and C/EBPβ have 2 isoforms as previously described (23). Right: each Western blotting band was quantitated and normalized to the level of GAPDH. Results are means ± SD from 3 bands shown at left. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 compared with A-C/EBP− control mice by Student's t-test. B: immunohistochemistry of lungs of A-C/EBP+ and A-C/EBP− mice fed Dox. Immunohistochemistry was carried out using mirror sections (between i and ii, and between iii and iv) and serial sections (between ii and iii, and between iv and v). Green asterisks are shown to locate the orientation of the sections. Immunohistochemistry was carried out for SCGB1A1 (red) and C/EBPα, C/EBPδ, or FOXA1 (black) for dual staining, and for CYP2F2 (brown). All 4 genes are generally highly expressed in bronchiolar epithelial cells of both A-C/EBP+ and A-C/EBP− mice as shown by black arrow in A-C/EBP− panel. In bronchiolar epithelial cells of A-C/EBP+ mice, some cells highly express SCGB1A1 and FOXA1 (black arrow), but not C/EBPα or C/EBPδ (blue arrows in A-C/EBP+ panel). Red arrows show alveolar cells that are positive for C/EBPα, C/EBPδ, and FOXA1 (shown in both A-C/EBP+ and A-C/EBP− panels). At least 3 lungs from each genotype were examined, and no differences in lung histology were found between the groups.

To determine the correlation among protein expression of SCGB1A1 and the three transcription factors C/EBPα, C/EBPδ, and FOXA1 at the individual cell level, immunohistochemistry was carried out in lung sections obtained from A-C/EBP+ mice fed Dox compared with A-C/EBP− mice (Fig. 6B). To locate the expression of these four proteins, mirror and serial sections were subjected to double immunohistochemistry for SCGB1A1 and C/EBPα, C/EBPδ, or FOXA1. Hematoxylin and eosin staining and immunostaining for Clara cell-specific monooxygenase CYP2F2 were also carried out to analyze epithelial cell integrity. A detailed examination of lung sections from at least three mice in each genotype revealed no histological modifications in the airway epithelial cells of A-C/EBP+ mice compared with A-C/EBP− mice, including those in the terminal bronchioli and the alveolar epithelia. The pattern of CYP2F2 expression in lung was indistinguishable between the two mouse lines. Immunohistochemistry further demonstrated that all four proteins, SCGB1A1, C/EBPα, C/EBPδ, and FOXA1, were highly expressed in most bronchiolar epithelial cells of wild-type as well as A-C/EBP+ mice in similar patterns. The expression of three transcription factors was also observed in many alveolar epithelial cells. In A-C/EBP+ mice, cells highly expressing SCGB1A1 and FOXA1 but clearly without any expression of C/EBPα and C/EBPδ were sometimes observed (Fig. 6, blue arrow). It should be noted, however, that immunohistochemistry is not quantitative and positive staining for C/EBPα or C/EBPδ by immunohistochemistry does not determine that they have transcription factor activity, since antibody reacts with C/EBP protein to which A-C/EBP binds and interferes with the DNA binding activity. Nevertheless, these results altogether suggested that FOXA1 may play a role in SCGB1A1 expression at individual cell levels in A-C/EBP+ mice fed Dox.

DISCUSSION

By use of a transgenic mouse line with lung-specific expression of a dominant-negative A-C/EBP, the present study revealed that FOXA1 becomes a critical transcription factor regulating Scgb1a1 gene expression in the absence of C/EBP activities in vivo. Thus loss of activity of a transcription factor(s) identified by in vitro studies as a main regulator of a gene(s) may not necessarily reflect the regulation of expression of the gene in vivo. The discrepancy between in vitro and in vivo transcriptional control was described on the basis of knockout mice studies (15). These studies, and our present results, suggest the importance of in vivo studies to understand the role of a specific transcription factor in regulation of a gene(s) in an intact organism. This is particularly important since transformed cell lines routinely used for transfection assays may represent different cellular conditions from the corresponding normal cell, and in most cases transfection assays observe only transient effects.

SCGB1A1, the most studied member of the SCGB gene superfamily, mainly expressed in lung, is a multifunctional protein with anti-inflammatory/immunomodulatory properties with manifestation of antichemotactic, antiallergic, antitumorigenic, and embryonic growth-stimulatory activities (18, 20). However, the physiological function(s) of SCGB1A1 is still elusive. C/EBPs are among the major transcription factors regulating expression of Scgb1a1 gene in lung as determined by in vitro experiments as shown in this manuscript and studies from others (4–10, 19, 22, 25, 26, 28). Thus the EMSA experiments clearly demonstrated that C/EBPα and C/EBPδ bind to the promoter of Scgb1a1 gene. FOXA1 is also able to bind its specific binding site in the Scgb1a1 gene promoter as previously described (6, 8, 19, 25, 26). In EMSA, A-C/EBP did not completely interfere with the binding of C/EBPα to its specific binding site. However, when C/EBPα, A-C/EBP, and FOXA1 were combined, the formation of C/EBPα-DNA specific bands was completely abolished and transient promoter activity was enhanced. Although the reason for these phenomena is not completely understood, these results strongly support the hypothesis that FOXA1 may become a major transcription factor for SCGB1A1 expression under constant suppression of C/EBPs' DNA binding activity. This notion is also supported by the fact that FOXA1's binding activity did not change by the presence of A-C/EBP and by immunohistochemical results, which showed that some cells in A-C/EBP+ mouse lungs have high expression of SCGB1A1 and FOXA1 with no clear expression of C/EBPα and C/EBPδ.

The in vitro transfection experiments with mtCC cells demonstrated that A-C/EBP reduced expression of all three C/EBP mRNAs, resulting in reduced expression of SCGB1A1 and SCGB2A2 mRNA levels without any effect on FOXA1 expression. This reduced level of C/EBPs and SCGB1A1 mRNAs in vitro was opposite to that of the in vivo results with Dox exposure. Although the exact mechanisms for the discrepancy between the in vivo and the in vitro systems is not known, it could be due to the fact that in the case of the in vitro system, the level of A-C/EBP expression is based on the amount of transfected plasmid within cells, which is robust, and the effect on C/EBPs' DNA binding activity is direct, all of which can occur within a short time period. On the other hand, in the in vivo system, several steps have to be involved in for the effect of A-C/EBP to appear. The concentration of Dox in lung may need to be maintained at sufficient level to have A-C/EBP expression at a concentration to effectively interact with C/EBPs at the protein level, which in turn interferes with their DNA binding to target genes. For this, the levels of mRNA and protein of C/EBPs need to reach a new equilibrium. Short-term Dox exposure demonstrated that the marked increase of A-C/EBP mRNA expression was already observed 3 days after Dox treatment, whereas the expression levels of other genes including SCGB1A1 and SCGB3A2 did not change in A-C/EBP+ mice compared with A-C/EBP− mice. Only C/EBPα and C/EBPδ mRNA levels were significantly up- and downregulated in A-C/EBP+ mice 10 days after Dox treatment, which might suggest that C/EBPs attempt to maintain expression of their target genes. After 4 mo of Dox exposure, C/EBP levels appeared to be stabilized both in mRNAs and proteins in A-C/EBP+ mice even though the expression level of A-C/EBP mRNA continuously increased for up to 4 mo of age. Furthermore, despite the fact that transgenic and lung epithelial-specific knockouts of C/EBPα exhibit respiratory failure at birth because of defects in lung epithelial cell maturation and function (3, 4, 17), emphysematous lungs were observed in part of the lobes in ∼25% of mice fed Dox in our experiments. These results may suggest that the effect of A-C/EBP on C/EBPs' DNA binding activity is inefficient and/or slow in vivo. Furthermore, since the endogenous expression levels of C/EBPs and FOXAs are not known either in mtCC cells or lungs, and the relative protein levels of A-C/EBP to those of C/EBPs are critical whether A-C/EBP can have a complete suppression of C/EBPs' transcriptional activities, it is difficult to directly compare the results obtained from these two systems.

There also remains the possibility that lung homeostasis may have changed in A-C/EBP+ mice after long-term Dox exposure. Three C/EBPs together may directly affect the expression of a large number of genes as demonstrated by a transcription profiling study for C/EBPα target genes (12). C/EBPα may also interact with other proteins to indirectly regulate many downstream genes. For instance, C/EBPα is known to interact with Cdk2, p21, and HDAC1 (27, 30, 31). As a result, the expression of a large number of genes may be directly and/or indirectly affected in lungs of A-C/EBP+ mice fed Dox. Chronic alteration of gene expression and/or cellular events may result in altered homeostasis of the lung, including the immune system, which may in turn require higher expression of immunomodulatory proteins such as SCGB1A1. Alternatively, long-term suppression of C/EBPs activities may result in remodeling of the airway cells over a long period of time that in turn regulates other cellular and/or transcriptional events. Because lung histology did not reveal any differences between A-C/EBP+ and A-C/EBP− mice, remodeling of the airway cells, if any, may be quite subtle. Altogether, the data suggest a critical role for SCGB1A1 in homeostasis and/or physiological function(s) of the lung and the need for a backup system to maintain its expression level. Thus, in the situation in which C/EBPs' activities are not fully available, FOXA1 becomes a critical transcription factor. This notion was further supported by the fact that A-C/EBP+ mouse lungs had even higher levels of SCGB1A1 protein than A-C/EBP− mice as determined by Western blotting. This also suggests the possible involvement of protein stabilization and/or the increase in translation in the regulation of SCGB1A1 expression in vivo. Note that Scgb1a1-null mice are viable with apparent normal appearance; however, they manifest various problems under various challenges (20). Since FOXA2 can bind to the FOXA binding site, it is likely that FOXA2 behaves similarly to FOXA1 in the presence of A-C/EBP. In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that FOXA1 becomes a critical transcription factor regulating SCGB1A1 expression in the absence of C/EBP activities in vivo. Thus in vivo studies are necessary, especially to determine the role of a transcription factor(s) in the transcriptional regulation of a gene of interest in complex tissues in vivo.

GRANTS

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Drs. Jeffrey Whitsett (Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH) for providing the CCSP-rtTA transgenic mouse, Francesco DeMayo (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX) for providing mtCC cells, and Frank Gonzalez (NCI) for critical review of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith JA, Struhl K. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. Somerset, NJ: Wiley, 2010, p. 12.2.1–12.2.11 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barlier-Mur AM, Chailley-Heu B, Pinteur C, Henrion-Caude A, Delacourt C, Bourbon JR. Maturational factors modulate transcription factors CCAAT/enhancer-binding proteins alpha, beta, delta, and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma in fetal rat lung epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 29: 620–626, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Basseres DS, Levantini E, Ji H, Monti S, Elf S, Dayaram T, Fenyus M, Kocher O, Golub T, Wong KK, Halmos B, Tenen DG. Respiratory failure due to differentiation arrest and expansion of alveolar cells following lung-specific loss of the transcription factor C/EBPalpha in mice. Mol Cell Biol 26: 1109–1123, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Berg T, Didon L, Nord M. Ectopic expression of C/EBPα in the lung epithelium disrupts late lung development. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 291: L683–L693, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Besnard V, Wert SE, Kaestner KH, Whitsett JA. Stage-specific regulation of respiratory epithelial cell differentiation by Foxa1. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 289: L750–L759, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bingle CD, Hackett BP, Moxley M, Longmore W, Gitlin JD. Role of hepatocyte nuclear factor-3 alpha and hepatocyte nuclear factor-3 beta in Clara cell secretory protein gene expression in the bronchiolar epithelium. Biochem J 308: 197–202, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cao Z, Umek RM, McKnight SL. Regulated expression of three C/EBP isoforms during adipose conversion of 3T3–L1 cells. Genes Dev 5: 1538–1552, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cassel TN, Berg T, Suske G, Nord M. Synergistic transactivation of the differentiation-dependent lung gene Clara cell secretory protein (secretoglobin 1a1) by the basic region leucine zipper factor CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha and the homeodomain factor Nkx2.1/thyroid transcription factor-1. J Biol Chem 277: 36970–36977, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cassel TN, Nord M. C/EBP transcription factors in the lung epithelium. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 285: L773–L781, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cassel TN, Nordlund-Moller L, Andersson O, Gustafsson JA, Nord M. C/EBPalpha and C/EBPdelta activate the clara cell secretory protein gene through interaction with two adjacent C/EBP-binding sites. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 22: 469–480, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chiba Y, Kurotani R, Kusakabe T, Miura T, Link BW, Misawa M, Kimura S. Uteroglobin-related protein 1 expression suppresses allergic airway inflammation in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 173: 958–964, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Halmos B, Basseres DS, Monti S, D'Alo F, Dayaram T, Ferenczi K, Wouters BJ, Huettner CS, Golub TR, Tenen DG. A transcriptional profiling study of CCAAT/enhancer binding protein targets identifies hepatocyte nuclear factor 3 beta as a novel tumor suppressor in lung cancer. Cancer Res 64: 4137–4147, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Johnson PF. Molecular stop signs: regulation of cell-cycle arrest by C/EBP transcription factors. J Cell Sci 118: 2545–2555, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kurotani R, Tomita T, Yang Q, Carlson BA, Chen C, Kimura S. Role of secretoglobin 3A2 in lung development. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 178: 389–398, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lee YH, Sauer B, Johnson PF, Gonzalez FJ. Disruption of the c/ebp alpha gene in adult mouse liver. Mol Cell Biol 17: 6014–6022, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Magdaleno SM, Wang G, Jackson KJ, Ray MK, Welty S, Costa RH, DeMayo FJ. Interferon-γ regulation of Clara cell gene expression: in vivo and in vitro. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 272: L1142–L1151, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Martis PC, Whitsett JA, Xu Y, Perl AK, Wan H, Ikegami M. C/EBPalpha is required for lung maturation at birth. Development 133: 1155–1164, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Miller TL, Shashikant BN, Pilon AL, Pierce RA, Shaffer TH, Wolfson MR. Effects of recombinant Clara cell secretory protein (rhCC10) on inflammatory-related matrix metalloproteinase activity in a preterm lamb model of neonatal respiratory distress. Pediatr Crit Care Med 8: 40–46, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Minoo P, Hu L, Xing Y, Zhu NL, Chen H, Li M, Borok Z, Li C. Physical and functional interactions between homeodomain NKX2.1 and winged helix/forkhead FOXA1 in lung epithelial cells. Mol Cell Biol 27: 2155–2165, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mukherjee AB, Zhang Z, Chilton BS. Uteroglobin: a steroid-inducible immunomodulatory protein that founded the Secretoglobin superfamily. Endocr Rev 28: 707–725, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Newman JR, Keating AE. Comprehensive identification of human bZIP interactions with coiled-coil arrays. Science 300: 2097–2101, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Niimi T, Keck-Waggoner CL, Popescu NC, Zhou Y, Levitt RC, Kimura S. UGRP1, a uteroglobin/Clara cell secretory protein-related protein, is a novel lung-enriched downstream target gene for the T/EBP/NKX2.1 homeodomain transcription factor. Mol Endocrinol 15: 2021–2036, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ossipow V, Descombes P, Schibler U. CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein mRNA is translated into multiple proteins with different transcription activation potentials. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90: 8219–8223, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ramji DP, Foka P. CCAAT/enhancer-binding proteins: structure, function and regulation. Biochem J 365: 561–575, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sawaya PL, Luse DS. Two members of the HNF-3 family have opposite effects on a lung transcriptional element; HNF-3 alpha stimulates and HNF-3 beta inhibits activity of region I from the Clara cell secretory protein (CCSP) promoter. J Biol Chem 269: 22211–22216, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sawaya PL, Stripp BR, Whitsett JA, Luse DS. The lung-specific CC10 gene is regulated by transcription factors from the AP-1, octamer, and hepatocyte nuclear factor 3 families. Mol Cell Biol 13: 3860–3871, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tan EH, Hooi SC, Laban M, Wong E, Ponniah S, Wee A, Wang ND. CCAAT/enhancer binding protein alpha knock-in mice exhibit early liver glycogen storage and reduced susceptibility to hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res 65: 10330–10337, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tomita T, Kido T, Kurotani R, Iemura S, Sterneck E, Natsume T, Vinson C, Kimura S. CAATT/enhancer-binding proteins alpha and delta interact with NKX2–1 to synergistically activate mouse secretoglobin 3A2 gene expression. J Biol Chem 283: 25617–25627, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Vinson C, Myakishev M, Acharya A, Mir AA, Moll JR, Bonovich M. Classification of human B-ZIP proteins based on dimerization properties. Mol Cell Biol 22: 6321–6335, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wang GL, Salisbury E, Shi X, Timchenko L, Medrano EE, Timchenko NA. HDAC1 cooperates with C/EBPalpha in the inhibition of liver proliferation in old mice. J Biol Chem 283: 26169–26178, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wang H, Iakova P, Wilde M, Welm A, Goode T, Roesler WJ, Timchenko NA. C/EPalpha arrests cell proliferation through direct inhibition of Cdk2 and Cdk4. Mol Cell 8: 817–828, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]