Abstract

The pathological hallmarks of bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD), one of the most common long-term pulmonary complications associated with preterm birth, include arrested alveolarization, abnormal vascular growth, and variable interstitial fibrosis. Severe BPD is often complicated by pulmonary hypertension characterized by excessive pulmonary vascular remodeling and right ventricular hypertrophy that significantly contributes to the mortality and morbidity of these infants. Connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) is a multifunctional protein that coordinates complex biological processes during tissue development and remodeling. We have previously shown that conditional overexpression of CTGF in airway epithelium under the control of the Clara cell secretory protein promoter results in BPD-like architecture in neonatal mice. In this study, we have generated a doxycycline-inducible double transgenic mouse model with overexpression of CTGF in alveolar type II epithelial (AT II) cells under the control of the surfactant protein C promoter. Overexpression of CTGF in neonatal mice caused dramatic macrophage and neutrophil infiltration in alveolar air spaces and perivascular regions. Overexpression of CTGF also significantly decreased alveolarization and vascular development. Furthermore, overexpression of CTGF induced pulmonary vascular remodeling and pulmonary hypertension. Most importantly, we have also demonstrated that these pathological changes are associated with activation of integrin-linked kinase (ILK)/glucose synthesis kinase-3β (GSK-3β)/β-catenin signaling. These data indicate that overexpression of CTGF in AT II cells results in lung pathology similar to those observed in infants with severe BPD and that ILK/GSK-3β/β-catenin signaling may play an important role in the pathogenesis of severe BPD.

Keywords: inflammation, vascular development, vascular remodeling, GSK-3β, β-catenin

despite recent advances in neonatal intensive care and surfactant therapy, bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) continues to be one of the most common long-term pulmonary complications associated with preterm birth (29). Exposure to mechanical ventilation and supplemental oxygen for initial respiratory distress induces inflammatory responses that play a key role in the pathogenesis of BPD (29, 46). The inflammatory processes disrupt normal lung development and lead to chronic lung structure damage characterized by arrested alveolarization, abnormal vascular growth, and variable interstitial fibrosis (8, 23, 28, 46). Severe BPD is often complicated by pulmonary hypertension characterized by excessive pulmonary vascular remodeling and right ventricular hypertrophy that significantly contributes to the mortality and morbidity of these infants (14, 47, 48). However, there remains a significant gap in our knowledge regarding the interplay of growth factors, transcription factors, and inflammatory mediators that orchestrate normal lung development, the inflammatory response to injury, and the pathogenesis of BPD.

Connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) is a prototypical member of the CCN family of modular proteins that coordinate complex biological processes during tissue development and remodeling (34). Expression of CTGF is upregulated by several factors involved in tissue remodeling, including transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), mechanical ventilation, and oxygen exposure (7, 17, 18, 49, 50). Upon stimulation, CTGF is secreted into the extracellular environment, where it interacts with distinct cell surface receptors, growth factors, and the extracellular matrix (ECM) (34). The principal CTGF receptor is the heterodimeric cell surface integrin complex whereas integrin-linked kinase (ILK) is a key mediator of integrin signaling that interacts with the cytoplasmic domain of β integrins (22, 25, 40). Activated ILK subsequently phosphorylates AKT, also known as protein kinase B and glucose synthesis kinase-3 β (GSK-3β) thus leading to activation of a diverse array of cellular processes (22, 37, 45). In addition to its binding to integrins, CTGF can also bind to low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5/6, thus modulating Wnt signaling (38, 53). Furthermore, CTGF also binds to various growth factors in the ECM, thereby modifying their activity. The binding of CTGF to TGF-β enhances TGF-β dimerization with its receptors, thus facilitating TGF-β signaling (1). In contrast, binding of CTGF to vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) decreases VEGF availability to its receptors, thus inhibiting VEGF-induced angiogenesis (11, 24). Overexpression of CTGF is associated with many forms of adult lung fibrosis and pulmonary vascular remodeling (3, 44). Increasing data suggest that CTGF also plays an important role in neonatal lung injury. Our laboratory and others have demonstrated that mechanical ventilation and hyperoxia exposure induce CTGF expression in lungs of neonatal animals (2, 7, 50). Furthermore, our most recent study has demonstrated that inducible overexpression of CTGF in airway epithelium under the control of the Clara cell secretory protein (CCSP) gene promoter disrupts alveolarization, decreases pulmonary vascular development, and induces interstitial fibrosis in the neonatal mouse lungs, which are similar to the lung pathology seen in BPD (51).

Because BPD is a distal lung disease, we have recently generated doxycycline (Dox)-inducible transgenic mice with overexpression of CTGF in alveolar type II epithelial (AT II) cells under the control of the surfactant protein C (SP-C) gene promoter. We report here that overexpression of CTGF in AT II cells of neonatal mice not only severely disrupts alveolarization and pulmonary vascularization but also induces excessive pulmonary vascular remodeling and pulmonary hypertension. Furthermore, these lung structural changes were associated with activation of ILK/GSK-3β/β-catenin signaling in vivo and in vitro. Taken together, these data strongly support an important role for CTGF and ILK/GSK-3β/β-catenin signaling in the pathogenesis of severe BPD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of Dox-inducible transgenic mice with overexpression of CTGF in AT II cells under the direction of the SP-C gene promoter.

The study protocols were reviewed and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Miami (Miami, FL). The conditional and tissue specific overexpression of CTGF was achieved by mating two lines of transgenic mice, the SP-C-rtTA mice (line 2), bearing the reverse tetracycline responsive transactivator (rtTA) under the control of the 3.7-kb rat SP-C gene promoter (41), and the TetO-CTGF mice, containing tetracycline operator (TetO) and minimal CMV promoter and CTGF transgene. The SP-C-rtTA mice were provided by Dr. Jeffrey Whitsett (Cincinnati Children's Hospital, Cincinnati, OH), and the TetO-CTGF mice were generated in the University of Miami Transgenic Facility and have been previously described (51). To generate double transgenic mice, the homozygous SP-C-rtTA mice were mated with the heterozygous TetO-CTGF mice. The newborn mice were genotyped by PCR of tail DNA with SP-C-rtTA primers, 5′-GACACATATAAGACCCTGGTCA-3′ and 5′-AAAATCTTGCCAGCTTTCCCC-3′, and TetO-CTGF primers as previously described (51). The single transgenic SP-C-rtTA mice were used as control mice, and the double transgenic SP-C-rtTA/Teto-CTGF mice were used and referred to as CTGF mice. To induce CTGF expression in the lungs of newborn pups, the nursing dams were fed with Dox-containing water (1 mg/ml) from postnatal day (P) 1. Additional litters were given regular drinking water to determine whether CTGF is induced in the absence of Dox treatment.

Wild-type mice and hyperoxia exposure.

Time pregnant wild-type FVB mice were raised in the animal facility at the University of Miami School of Medicine. Within 24 h after birth mouse pups were randomized to receive normoxia (21% O2) or hyperoxia (90% O2) for 14 days. Continuous 90% O2 exposure was achieved in a Plexiglas chamber by a flow-through system and the oxygen levels inside the Plexiglas chamber were monitored continuously with a Ceramatec (MAXO2) oxygen analyzer. Nursing dams were rotated between normoxia and hyperoxia every 48 h to prevent oxygen toxicity in the dams.

Tissue preparation.

Mice were killed on P7 and P14, and the lungs were infused with 4% paraformaldehyde via a tracheal catheter at 20 cmH2O of pressure for 5 min and then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution overnight at 4°C. Fixed lung tissues were paraffin embedded, and 5-μm sections were processed. Additional lungs were also collected for total RNA and protein isolation.

Lung histology and morphometry.

Lung tissue sections were stained by standard hematoxylin and eosin (HE) method for histology and morphometry. The lung morphometric analysis was performed by a staff unaware of the experimental condition. For mean linear intercept (MLI) assessment, 10 random images were taken with the ×20 objective on each HE-stained lung tissue section. The images were viewed under a field of equally spaced horizontal lines, and the MLI was calculated as the average of total length of lines divided by the total intercepts of alveolar septa from each lung. For radial alveolar count (RAC) measurement, 10 random terminal respiratory bronchioles were identified under the ×20 objective on each HE-stained lung tissue section. The number of distal air sacs that were transected by a line drawn from a terminal respiratory bronchiole to the nearest pleural surface was counted, and the RAC was calculated as the average of number of distal air sacs from each lung.

Immunostaining and double immunofluorescence staining.

The following primary antibodies were used in immunostaining and immunofluorescence staining: goat anti-CTGF and anti-monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1) and mouse anti-proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) antibodies from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA); a rabbit anti-von Willebrand factor (vWF) antibody from Dako (Carpinteria, CA); mouse anti-α smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and anti-β-catenin antibodies from Sigma (St. Louis, MO); a rabbit anti-pro-SP-C antibody from Chemicon (Temecula, CA); a rat anti-Mac3 antibody from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA); a rabbit anti-ILK antibody from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). The immunostaining and double immunofluorescence staining were performed as previously described (51). The tissue sections were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated through graded ethanol into PBS. The sections were incubated with the respective primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. For immunostaining, the tissue sections were then incubated with biotinylated secondary IgGs for 1 h at room temperature. The cell-bound biotinylated secondary antibodies were detected with either streptavidin-biotin-alkaline phosphatase complexes and substrates or streptavidin-biotin-peroxidase complexes and diaminobenzidine substrates (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). For double immunofluorescence staining, the tissue sections were then incubated with Alexa Fluor 488 and/or Alexa Fluor 594-labeled secondary antibodies (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 1 h at room temperature. After being washed with PBS, the tissue sections were counterstained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Vector Laboratories) and mounted with glycerol.

Pulmonary vascular morphometry.

Immunofluorescence staining for vWF, an endothelial specific marker, was performed for assessing vascular density. Ten random images were taken with the ×20 objective on each vWF-stained slide. The vascular density was expressed as the average number of vWF-positive vessels (15–50 μm) per high-power field (HPF).

Assessment of pulmonary vascular muscularization and remodeling.

The degree of muscularization and medial wall thickness of peripheral pulmonary vessels (15–50 μm) were determined on α-SMA-stained tissue sections. Muscularized vessels were defined by the presence of smooth muscle cells positively stained with α-SMA antibody in 50% or more of the vessel circumference of intraacinous arterioles as previously described (15, 55). The total number of vessels and muscularized vessels were counted from 10 random images taken with the ×20 objective on each slide for calculation of the percentage of muscularized vessels. For medial wall thickness assessment, random images containing 25 vessels were taken with the ×40 objective on each slide. The external diameter and internal diameter of the α-SMA-stained lamina were measured, and the medial wall thickness was determined by the average external diameter minus the average internal diameter and divided by the average external diameter from each slide. For assessing proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells, double immunofluorescence staining for PCNA and α-SMA was performed. The number of vessels with at least one PCNA-positive nucleus in smooth muscle cells was counted from 25 vessels (15–50 μm) on each slide.

Assessment of pulmonary hypertension.

Right ventricular systolic pressure (RVSP) and right ventricle (RV) to left ventricle (LV) plus septum weight ratio (RV/LV+S) were determined as indexes for pulmonary hypertension in 2-wk-old mice as previously described (54). Briefly, mice were sedated, tracheotomized, and ventilated with a Harvard Mini-Vent. After thoracotomy, a 25-gauge needle fitted to a pressure transducer was inserted into the RV. RVSP was measured and continuously recorded on a Gould polygraph. Immediately after RVSP measurements, hearts were dissected for RV free wall separation from LV+S for RV/LR+S ratio measurements.

BAL and analysis.

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed in 4-wk-old control and CTGF mice by instilling 0.5 ml cold normal saline into the airway through a trachea catheter and gently withdrawing the fluid. The lavage was repeated four times to recover a total volume of 1.5–2 ml. The cells were stained with Trypan blue to determine viability and with Turk solution to obtain total nucleated cell counts by use of a hemocytometer. Cytospin (Cytospin 2; Shandon, Waltham, MA) slides were prepared from the BAL fluid and were then fixed and stained by using a Neat Stain hematology kit (Polysciences, Warrington, PA). Differential cell counts were determined by counting 300 cells per each slide.

Assessment of lung inflammation.

Lung inflammation was assessed by histology and immunostaining for Mac3, a macrophage-specific marker. The number of Mac3-positive cells in the alveolar air spaces was counted from 10 random images taken with the ×40 objective on each slide. To determine the potential mechanisms causing macrophage infiltration, double immunofluorescence staining for MCP-1 and Mac3 as well as MCP-1 and pro-SP-C was performed.

AT II cell isolation and culture.

AT II cells were isolated and cultured from 4-wk-old control and CTGF mice as previously described with some modification (42, 56). Mice were euthanized by intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital and tracheotomized. The lungs were infused with dispase solution followed by low-melting agarose via a tracheal catheter and were covered by ice to allow the agarose to polymerize. The lungs were then dissected and digested in dispase and teased from the bronchi in DNase solution. The cell suspension was filtered through gradient cell strainers (100 μm to 20 μm), and the cells were pelleted by centrifugation and then placed on tissue culture plates precoated with anti-CD 45 and anti-CD 32 antibodies (BD Biosciences). After incubation for 2 h in a humidified 37°C incubator with 21% O2 and 5% CO2, the AT II cells (nonadhered) were collected, centrifuged, and placed on Matrigel (70%)-coated eight-well chamber slides or six-well plates (BD Biosciences). The AT II cells were cultured overnight in bronchial epithelial cell growth medium minus hydrocortisone (Lonza, Portsmouth, NH) with 5% charcoal-stripped fetal calf serum and keratinocyte growth factor. The media were changed to fresh media containing Dox (1 μg/ml), and the cells were cultured for additional 72 h. Live cells were imaged and immunofluorescence staining was performed on these cells. The purity of AT II cells was typically >90%, as assessed by pro-SP-C staining.

RNA isolation and quantitative real-time RT-PCR.

Total RNA was isolated from frozen lung tissues and AT II cells and treated with DNase to remove possible DNA contamination as described (51). One microgram of total RNA was reverse-transcribed in a 20-μl reaction by using a first-strand cDNA synthesis kit according to manufacturer's protocol (Invitrogen). The real-time RT-PCR was performed on an ABI Fast 7500 System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Each reaction included diluted first-strand cDNA, specific primers, and master mix containing enzymes and TaqMan probes according to the manufacturer's instruction (Applied Biosystems). Real-time RT-PCR conditions were 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 30 s. RNase-free water was used as a negative control. For each target gene, a standard curve was established by performing a series of dilutions of the first-strand cDNA. The mRNA expression levels of target genes were determined from the standard curve and normalized to GAPDH.

Western blot analysis.

Total protein was extracted from frozen lung tissues with a RIPA buffer according to manufacturer's protocol (Santa Cruz). The protein concentrations were measured by a BCA protein assay using a commercial kit from Pierce Biotechnology (Rockford, IL). Total proteins (50 μg/sample) were fractionated by SDS-PAGE on 4–12% Tris-glycine precast gradient gels (Invitrogen) and then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ). The membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with respective primary antibodies and then incubated for 1 h at room temperature with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies. Antibody bound proteins were detected by ECL chemiluminescence methodology (Amersham). Membranes were then stripped with 0.2 N NaOH and reincubated with primary antibodies reactive with a normalization protein, β-actin. The intensities of protein bands were quantified by Quantity One Imaging Analysis Program (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Data presentation and statistical analysis.

Results are expressed as means ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed by Student's t-test. A P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Overexpression of CTGF disrupts alveolarization.

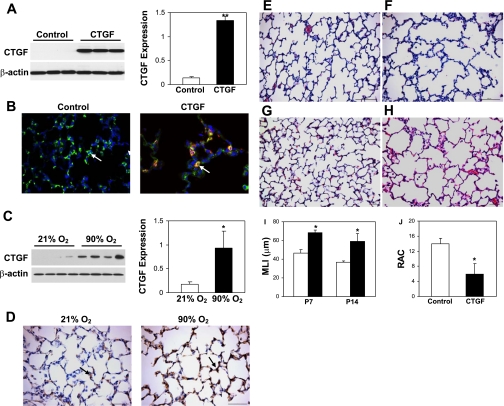

After mice were exposed to Dox from P1 to P14, high levels of CTGF expression were detected by Western blot analysis in lung homogenates from CTGF mice (Fig. 1A). Double immunofluorescence staining colocalized CTGF in AT II cells in lung tissue sections from these mice (Fig. 1B). This increased CTGF expression was similar to that observed in lungs from hyperoxia-exposed newborn mice for 14 days (Fig. 1, C and D). On histological examination at P7 and P14, the control lungs displayed normal alveolar development with numerous small alveoli and secondary septa (Fig. 1, E and G). In contrast, there were larger and simplified alveoli with fewer secondary septa in CTGF lungs (Fig. 1, F and H). Further morphometric analysis demonstrated a 30% increase at P7 and a 50% increase at P14 in MLI in CTGF lungs compared with control lungs (Fig. 1I). The RAC was reduced by near 60% in CTGF lungs at P14 (Fig. 1J). There was no difference in CTGF expression and alveolarization between CTGF lungs and control lungs without Dox exposure (data not shown). Thus overexpression of CTGF in AT II cells severely disrupted alveolarization in neonatal mice.

Fig. 1.

Connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) disrupted alveolarization. Western blot analysis demonstrated a significant increase in CTGF expression in CTGF- (A) and hyperoxia-exposed lungs (C). B: double immunofluorescence staining was performed on lung tissue sections at P14 with an anti-pro-surfactant protein C (SP-C) (green signal) and an anti-CTGF antibody (red signal) and 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) nuclear staining (blue signal). Pro-SP-C (arrow) was detected in control and CTGF lungs, but CTGF was only colocalized with pro-SP-C (orange signal, arrow) in CTGF lungs. D: immunostaining with an anti-CTGF antibody demonstrated a marked increase in CTGF expression in hyperoxia-exposed lungs compared with normoxia-exposed lungs. Hematoxylin and eosin (HE)-stained lung tissue sections from control lungs at postnatal day (P) 7 (E) and P14 (G) demonstrated normal alveolar development. However, overexpression of CTGF disrupted alveolar development with larger and simplified alveoli at P7 (F) and P14 (H). Mean linear intercept (MLI) was significantly increased in CTGF lungs at P7 and P14 (I). Open bars, control lungs; solid bars, CTGF lungs. Radial alveolar count (RAC) was significantly decreased in CTGF lungs (J). N = 4/group. *P < 0.01. **P < 0.001. Magnification: ×40 (B, D), ×20 (E–H). Scale bars: 50 μm (D, G, H) and 100 μm (E, F).

Overexpression of CTGF inhibits pulmonary vascular development.

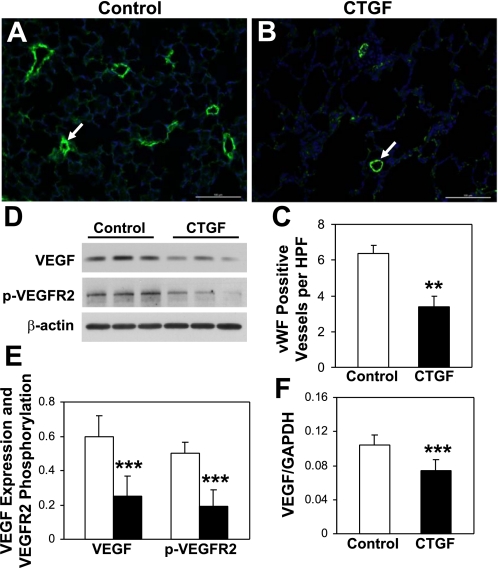

To determine whether epithelial overexpression of CTGF disrupts pulmonary vascular development, vascular density was quantified by immunofluorescence staining for vWF. There was a 60% decrease in vWF-positive intraacinous vessels in CTGF lungs compared with control lungs at P14 (Fig. 2, A–C), indicating severe inhibition of pulmonary vascular development. Because VEGF plays a key role in pulmonary vascular development, VEGF expression and VEGF receptor 2 (VEGFR2) phosphorylation were assessed in lung homogenates. VEGF expression was significantly decreased in CTGF lungs compared with control lungs (Fig. 2, D and E). Correlating with decreased VEGF expression, there was a decreased VEGFR2 phosphorylation in CTGF lungs (Fig. 2, D and E). We also examined VEGF gene expression in primary cultured AT II cells and found that it was significantly decreased in CTGF lungs (Fig. 2F). These results indicate that decreased VEGF expression and its signaling may mediate CTGF inhibition of lung vascular development.

Fig. 2.

CTGF decreased vascular development. Immunofluorescence staining was performed on lung tissue sections from control (A) and CTGF (B) lungs at P14 with an anti-von Willebrand factor (vWF) antibody (green signal) and DAPI nuclear staining (blue signal). The number of vWF-positive vessels (15–50 μm, arrow) was significantly decreased in CTGF lungs (C). Western blot analysis (D and E) demonstrated significant decreases in VEGF expression and VEGF receptor 2 (VEGFR2) phosphorylation in CTGF lungs (solid bars) compared with control lungs (open bars). Real-time RT-PCR demonstrated a significant decrease in VEGF gene expression in CTGF lungs (F). N = 4/group in C and 3/group in E and F. **P < 0.001 and ***P < 0.05. Magnification: ×20. Scale bars: 100 μm.

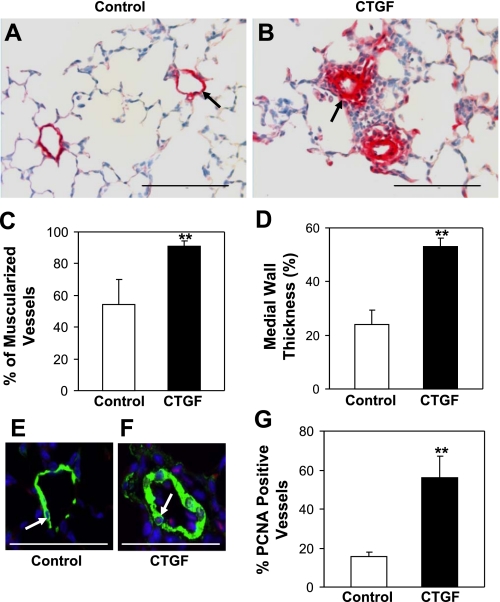

Overexpression of CTGF induces pulmonary vascular remodeling.

To determine the effect of overexpression of CTGF on pulmonary vascular remodeling, we performed immunostaining for α-SMA, a smooth muscle marker. Abnormally extensive muscularization of peripheral pulmonary vessels was detected in CTGF lungs compared with control lungs, which showed little or partial staining for α-SMA (Fig. 3, A and B). There was a 70% increase in muscularized vessels in CTGF lungs (Fig. 3C). There was also a more than twofold increase in medial wall thickness of these vessels in CTGF lungs (Fig. 3D). Correlating with increased wall thickness, there was significantly increased vessels with proliferating cells in CTGF lungs (Fig. 3, F and G). These data indicate that epithelial overexpression of CTGF results in excessive pulmonary vascular remodeling.

Fig. 3.

CTGF induced pulmonary vascular remodeling. Immunostaining with an anti-α-SMA antibody was performed on control (A) and CTGF (B) lungs at P14. Overexpression of CTGF significantly increased the percentage of muscularized vessels (C) and medial wall thickness (D) (15–50 μm). Double immunofluorescence staining was performed with an anti-α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) (green signal) and an anti-proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) antibody (red signal) and DAPI nuclear staining (blue signal). E: a representative small pulmonary vessel from control. F: representative small pulmonary vessel from CTGF lung. Quantification of PCNA-positive vessels (pink signal in nuclei, arrow) was significantly increased in CTGF lungs (G). N = 4/group. **P < 0.001. Magnification: ×40. Scale bars: 100 μm (A and B); 50 μm (E and F).

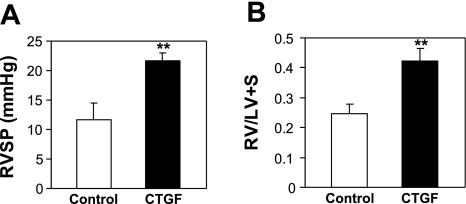

Overexpression of CTGF induces pulmonary hypertension.

To determine whether CTGF-induced inhibition of pulmonary vascularization and vascular remodeling leads to pulmonary hypertension, RVSP and RV/LV+S were assessed. The RVSP was significantly higher in CTGF mice compared with control mice (Fig. 4A). The CTGF mice also had a significant increase in RV/LV+S (Fig. 4B), suggesting right ventricular hypertrophy. These results support that epithelial overexpression of CTGF causes pulmonary hypertension in neonatal mice.

Fig. 4.

CTGF induced pulmonary hypertension. A: right ventricular systolic pressure (RVSP). B: weight ratio of right ventricle to left ventricle plus septum (RV/LV+S) in 2-wk-old control and CTGF mice. Overexpression of CTGF significantly increased RVSP and RV/LV+S. N = 6 in control group and 4 in CTGF group. **P < 0.001.

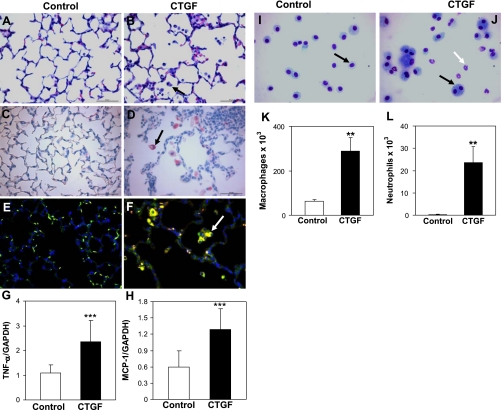

Overexpression of CTGF causes pulmonary inflammation.

On histological examination, there was increased inflammatory cell infiltration in alveolar air spaces and perivascular regions in CTGF lungs (Fig. 5B). Immunostaining with a Mac3 antibody demonstrated a ninefold increase in macrophage infiltration in alveolar air spaces in CTGF lungs compared with control lungs (13.08 ± 4.35 vs. 1.43 ± 0.22 per HPF, P < 0.001, Fig. 5D). Correlating with increased macrophage infiltration, there was a more than twofold increase in TNF-α gene expression in CTGF lungs (Fig. 5G), although there was no significance difference in gene expression of IL-1β and IL-6 between control and CTGF lungs (data not shown). Furthermore, macrophage and neutrophil counts were drastically increased in BAL fluids from CTGF mice (Fig. 5, J–L). There were numerous multinucleated giant cells in BAL fluids from CTGF mice, which were rarely seen in control mice (Fig. 5J). To determine the potential mechanisms of overexpression of CTGF-induced macrophage infiltration, we examined MCP-1 expression. Double immunofluorescence staining demonstrated increasing MCP-1 expression in infiltrated macrophages (Fig. 5F) as well as in AT II cells (data not shown) in CTGF lungs compared with control lungs where MCP-1 was undetectable (Fig. 5E). Moreover, MCP-1 gene expression was also significantly increased in CTGF lungs (Fig. 5H). These results suggest that overexpression of CTGF induces MCP-1 expression in macrophages and AT II cells that causes macrophage infiltration.

Fig. 5.

CTGF induced lung inflammation. Histological examination on HE-stained lung tissue sections revealed dramatic infiltration in 2-wk-old CTGF lungs (B, arrow) compared with control lungs (A). Immunostaining for Mac3 demonstrated a significant increase macrophage infiltration in alveolar air spaces in CTGF lungs (D, arrow) compared with control lungs (C) [13.08 ± 4.35 vs. 1.43 ± 0.22 per high-power field (HPF), n = 4/group, **P < 0.001]. Double immunofluorescence staining for Mac3 (green signal) and MCP-1 (red signal) detected increased MCP-1 expression in infiltrated macrophages in CTGF lungs (yellow signal, arrow, F) compared with control lungs where MCP-1 was undetectable (E). Real-time RT-PCR demonstrated increased gene expression of TNF-α and MCP-1 in CTGF lungs (G and H). Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed in 4-wk-old control and CTGF mice. Neat hematology stain identified only macrophages in BAL cytospin from control mice (I). However, multinucleated gain cells (black arrow) and neutrophils (white arrow) were detected in BAL cytospin from CTGF mice (J). Quantification of macrophages (K) and neutrophils (L) were both significantly increased in CTGF lungs. N = 4/group. **P < 0.001 and ***P < 0.05. Magnification: ×40. Scale bars: 50 μm.

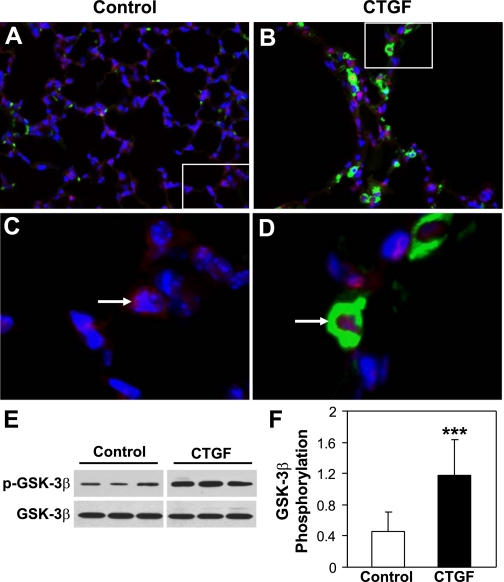

Overexpression of CTGF induces GSK-3β phosphorylation and β-catenin nuclear translocation in vivo.

To determine the potential mechanisms by which overexpression of CTGF causes lung pathology, we performed double immunofluorescence staining for β-catenin and CTGF in control and CTGF lungs. As demonstrated in Fig. 6, A and C, CTGF was undetectable and β-catenin was localized in the cytoplasm in control lungs. In contrast, β-catenin-positive nuclei were colocalized with CTGF-expressing cells in CTGF lungs (Fig. 6, B and D), suggesting that overexpression of CTGF induces β-catenin nuclear translocation. Because GSK-3β plays an important role in modulating β-catenin degradation and nuclear translocation, Western blot was performed to determine GSK-3β expression and phosphorylation. Overexpression of CTGF did not change GSK-3β expression but increased Ser9 GSK-3β phosphorylation, which is known to lose the ability to phosphorylate β-catenin, thus leading to β-catenin accumulation and nuclear translocation (52) (Fig. 6, E and F).

Fig. 6.

CTGF induced β-catenin nuclear translocation and GSK-3β phosphorylation in vivo. Double immunofluorescence staining for β-catenin (red signal) and CTGF (green signal) as well as DAPI nuclear staining (blue signal) was performed on lung tissue sections from 2-wk-old control (A and C) and CTGF (B and D) lungs. In control lungs β-catenin was mainly detected in the cytoplasm, whereas in CTGF lungs β-catenin was largely detected in the nuclei (pink signal) and that is colocalized with CTGF in the cytoplasm. Western blot analysis demonstrated that overexpression of CTGF significantly increased Ser9 GSK-3β phosphorylation (E and F). N = 5/group, ***P < 0.05. Magnification: ×40 (A and B). C: focal enlargement of A. D: focal enlargement of B as indicated with same magnification.

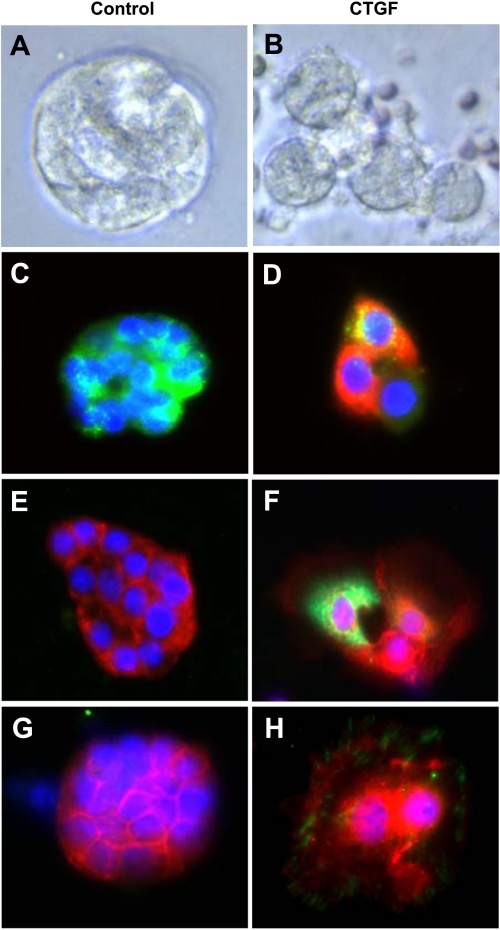

Overexpression of CTGF induces β-catenin nuclear translocation in primary AT II cells in vitro.

Primary AT II cell culture was performed to further identify the cellular and molecular mechanisms by which CTGF causes β-catenin nuclear translocation. When cultured on Matrigel, the AT II cells from control lungs grew in clusters and formed alveolar-like cysts (Fig. 7A). In contrast, the AT II cells from CTGF lungs appeared larger and were spread out (Fig. 7B). Double immunofluorescence staining demonstrated that the AT II cells from control lungs express high level of pro-SP-C but no CTGF (Fig. 7C). However, some of the AT II cells from CTGF lungs coexpress pro-SP-C and CTGF, indicating that these are SP-C-expressing AT II cells and overexpression of CTGF in AT II cells can be achieved in vitro (Fig. 7D). Double immunofluorescence staining also demonstrated that the AT II cells from control lungs express β-catenin in the cytoplasm (Fig. 7E), whereas β-catenin-positive nuclei were colocalized in CTGF-expressing cells from CTGF lungs (Fig. 7F). Furthermore, ILK was undetectable in AT II cells from control lungs (Fig. 7G), but it was colocalized with β-catenin-positive nuclei in AT II cells from CTGF lungs (Fig. 7H). These in vitro data are consistent with the in vivo data suggesting that overexpression of CTGF in AT II cells activates ILK/GSK-3β pathway, which may play an important role in CTGF-induced β-catenin nuclear translocation and lung pathology.

Fig. 7.

CTGF induced β-catenin nuclear translocation in primary alveolar type II epithelial (AT II) cells. AT II cells were isolated from 4-wk-old control and CTGF lungs and cultured for 72 h on Matrigel. Live cell imaging demonstrated alveolar-like cysts in control group (A) but larger and spread cells in CTGF group (B). Double immunofluorescence staining for pro-SP-C (green signal) and CTGF (red signal) and DAPI nuclear staining (blue signal) detected only pro-SP-C in control cells (C), but pro-SP-C and CTGF were colocalized (orange signal) in CTGF cells (D). Double immunofluorescence staining for β-catenin (red signal) and CTGF (green signal) and DAPI nuclear staining (blue signal) detected only β-catenin in the cytoplasm in control cells (E), but β-catenin was localized in the nuclei (pink signal) and in the cytoplasm (pale green signal) in CTGF-expressing cells (F). Double immunofluorescence staining for β-catenin (red signal) and integrin-linked kinase (ILK) (green signal) and DAPI nuclear staining (blue signal) detected only β-catenin in the cytoplasm in control cells (G), but β-catenin was localized in the nuclei (pink signal) and in the cytoplasm whereas ILK was localized in the cytoplasm in CTGF cells (H).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we provide direct evidence that overexpression of CTGF in AT II cells results in severe BPD-like architecture in neonatal mice. We demonstrate that inducible overexpression of CTGF in AT II cells during the alveolar stage of lung development induces pulmonary inflammation, disrupts alveolarization and pulmonary vascularization, and results in pulmonary vascular remodeling and pulmonary hypertension. The pulmonary inflammation was associated with increased MCP-1 expression in macrophages and AT II cells. The disruption of alveolarization and vascularization were associated with decreased VEGF expression and VEGFR2 activation. Furthermore, overexpression of CTGF activates ILK/GSK-3β pathway and results in β-catenin nuclear translocation. This study, therefore, provides important insights into the interplay of growth factors, transcriptional factors, and inflammatory mediators that orchestrates the epithelial-mesenchymal cross talk and the development of BPD.

We have demonstrated in this study that inducible overexpression of CTGF in AT II cells, under the control of SP-C promoter, severely disrupts alveolarization and pulmonary vascular development; this is similar to that observed in our previous study with overexpression of CTGF in airway epithelium, under the control of CCSP promoter (51). CTGF has been implicated in both angiogenesis and antiangiogenesis. Recent data demonstrate that CTGF knockout mice have normal angiogenesis, suggesting that endogenous CTGF is not essential for angiogenesis (31). However, increasing data indicate that CTGF is antiangiogenic through its interactions with VEGF, a key mitogenic and survival factor for endothelial cells produced by many cell types including AT II cells (33). CTGF inhibits VEGF expression in tumor cells through degrading hypoxia-inducible factor, which is responsible for VEGF gene transcription (6). CTGF can also form a complex with VEGF in ECM of aortic endothelial cells that inhibits the binding of VEGF to VEGF receptor 2 (VEGFR2), thus inhibiting VEGF angiogenesis (11, 24). Increasing data indicate that disruption of normal lung vascular development plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of BPD. Inhibition of VEGF or disruption of VEGFR2 results in severe disruption of air spaces and vasculature in experimental BPD and pulmonary hypertension (19, 33). In this study, overexpression of CTGF not only decreased VEGF expression but also impaired VEGFR2 activation. These results suggest that epithelial overexpression of CTGF may inhibit alveolarization and pulmonary vascular development through a VEGF-dependent mechanism.

Besides disruption of alveolarization and pulmonary vascular development, overexpression of CTGF in AT II cells also caused excessive pulmonary vascular remodeling. The pulmonary vascular remodeling is demonstrated by abnormally extensive muscularization and increased medial wall thickness of peripheral pulmonary vessels in CTGF lungs. Moreover, we have also demonstrated that there is increased cell proliferation of these vessels. There is compelling evidence that suggests that CTGF plays an important role in vascular remodeling in both pulmonary and systemic vasculatures. CTGF gene expression is upregulated in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (PASMC) in monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension (35). TGF-β/CTGF signaling promotes progressive neointimal hyperplasia in vein grafts (27). Furthermore, CTGF is the downstream mediator of TGF-β-induced adventitial remodeling in carotid angioplasty (32). This study provides for the first time the direct evidence that epithelial overexpression of CTGF causes excessive pulmonary vascular remodeling in the developing lung.

The development of pulmonary hypertension remains a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in severe BPD (14, 47, 48). In this study, overexpression of CTGF not only impaired vascular development but also induced pulmonary vascular remodeling that led to significant increase in both pulmonary artery pressure and right ventricular hypertrophy. In a rodent model of hyperoxia-induced BPD, pulmonary hypertension and right ventricular hypertrophy are associated with both impaired vascular development and increased vascular remodeling (4). The pulmonary hypertension may be caused by decreased pulmonary vasculature that limits vascular surface area, thus leading to elevation of pulmonary vascular resistance (47). The excessive pulmonary vascular remodeling may further contribute to high pulmonary vascular resistance through narrowing of the vessel diameter and decreased vascular compliance (47). However, the molecular mechanisms as well as the interplay of vascular development and remodeling in the pathogenesis of neonatal pulmonary hypertension are poorly understood. Our model provides the advantage for further exploring the individual role of vascular development and remodeling in the pathogenesis of neonatal hypertension.

An important finding of this study is that overexpression of CTGF results in significant inflammation in the neonatal lung. There was increased inflammatory cell infiltration in both air spaces and perivascular regions in CTGF lungs. Lung inflammation, whether induced prior to birth or during the early postnatal period, is considered the key mediator of alveolar and vascular injury in BPD. Clinical studies have demonstrated the presence of increased neutrophils, activated macrophages, and high concentrations of inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and TGF-β in tracheal fluid from preterm infants who subsequently developed BPD (46). Animal models further support the key role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of BPD. Transgenic overexpression of IL-β induced neutrophilic and monocytic infiltration, increased expression of chemokines such as macrophage inflammatory protein-2 (CXCL2) and MCP-1, and disrupted alveolar septation and capillary development in neonatal mice (5). A recent study has demonstrated that bone marrow stromal cells attenuate alveolar damage and pulmonary vascular remodeling in hyperoxia-induced murine BPD, and this correlated with prevention of neutrophil and macrophage infiltration (4). It is suggested that the protective effects of bone marrow stromal cells on alveolar structure may be caused by the immunomodulatory proteins produced by these cells (4). In contrast to CTGF's well-known ability to induce tissue remodeling, the inflammatory potential is just beginning to be understood. A recent study has demonstrated that systemic administration of CTGF increased renal expression of chemokines (MCP-1 and RANTES) and cytokines (INF-γ, IL-6, and IL-4) and induced marked infiltration of T lymphocytes and monocytes/macrophages in the renal interstitium (43). Furthermore, inhibition of NF-κB attenuated CTGF-induced renal inflammatory responses. Although the mechanisms of CTGF-induced inflammation in our model are not clear, we do have evidence that overexpression of CTGF increases MCP-1 expression in macrophages and AT II cells. We speculate that MCP-1 and other potential chemokines produced by macrophages and AT II cells may play a key role in CTGF-induced lung inflammation.

Although dysregulation of many growth factors and inflammatory mediators has been linked to the pathogenesis of BPD, the underlying molecular mechanisms are poorly understood. Our study identified for the first time that overexpression of CTGF induces β-catenin nuclear translocation. β-Catenin is a membrane-associated protein that is an effector of the canonical Wnt signaling (26, 30). β-Catenin also binds to cadherin in the adherens junction where it stabilizes cadherin-mediated cell-cell contact (26, 30). GSK-3β plays a key role in β-catenin degradation and nuclear translocation. Nonphosphorylated GSK-3β is the active form and can phosphorylate β-catenin and lead to β-catenin degradation in the cytoplasm (26, 30). Activation of ILK and/or Wnt signaling results in GSK-3β phosphorylation, thus leading to GSK-3β inactivation. Subsequently, β-catenin phosphorylation is inhibited, and its degradation is attenuated. Accumulated β-catenin then undergoes nuclear translocation, and that regulates target gene expression and cellular function (26, 30). The Wnt/β-catenin signaling is essential for lung morphogenesis and its dysregulation has been recently linked to the pathogenesis of many lung diseases, in particular lung fibrosis and hyperoxia-induced neonatal lung injury (10, 30). Less is known about ILK/GSK-3β signaling in lung development and remodeling. Previous studies have demonstrated an important role of ILK in regulating survival of lung fibroblasts and stimulating proliferation and migration of vascular SMC (13, 16, 39). Recent studies have shown that inhibition of GSK-3β protects bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis (20). Accumulating data indicate that CTGF can activate both ILK/GSK-3 and Wnt signaling in various pathological conditions. CTGF induces human proximal tubular epithelial cells to mesenchymal transition via an ILK-dependent pathway (36). CTGF induces primary mesangial cell migration and cytoskeletal rearrangement, and this is associated with GSK-3β phosphorylation. Furthermore, CTGF promotes tumorigenicity of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by inducing Ser9 GSK-3β phosphorylation and β-catenin nuclear translocation (12). In our transgenic model, overexpression of CTGF induces β-catenin nuclear translocation in AT II cells as well as other cells and this is associated with increased GSK-3β phosphorylation in vivo. Most importantly, we have also demonstrated that overexpression of CTGF causes β-catenin nuclear translocation in AT II cells in vitro and this is associated with increased ILK expression. These in vivo and in vitro data strongly support that the ILK/GSK-3β/β-catenin signaling plays a key role in CTGF disruption of neonatal lung structure. Further studies will be done to investigate the functional significance of this pathway in CTGF-induced neonatal lung injury and in other experimental models of BPD.

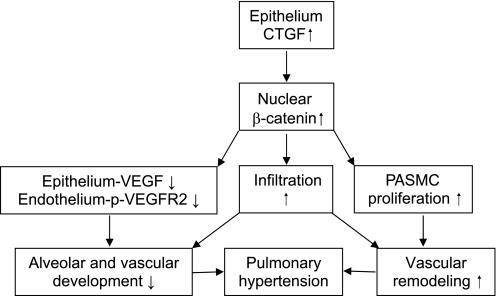

In summary, our data reveal a novel role of CTGF in the pathogenesis of severe BPD. This transgenic model replicates the pathological hallmarks of severe BPD, namely pulmonary inflammation, impaired alveolarization and vascularization, and excessive pulmonary vascular remodeling and pulmonary hypertension. Most importantly, this study provides both in vivo and in vitro evidence that overexpression of CTGF activates the ILK/GSK-3β pathway and induces β-catenin nuclear translocation. We propose that epithelial overexpression of CTGF activates the ILK/GSK-3β/β-catenin via autocrine and/or paracrine mechanisms leading to epithelial and endothelial cell dysfunction and PASMC remodeling, thus resulting in lung structural changes and pulmonary hypertension. Furthermore, the inflammatory response induced by CTGF via β-catenin-dependent and/or independent mechanisms potentiates CTGF-induced lung structural change (Fig. 8). This work provides important insights into the interplay of growth factors, transcriptional factors, and inflammatory processes orchestrating normal lung development and the pathogenesis of BPD, and this could potentially lead to the development of novel therapies aimed at anti-inflammation, promoting lung development and preventing pulmonary hypertension in neonates.

Fig. 8.

Proposed model for CTGF inhibition of alveolarization and vascularization and induction of pulmonary hypertension in neonatal lungs. Overexpression of CTGF in AT II cells via an autocrine mechanism induces β-catenin nuclear translocation, and that may decrease VEGF expression in epithelium leading to decreased VEGFR2 phosphorylation in endothelium, thus disrupting alveolar and pulmonary vascular development. Epithelium-produced CTGF may also induce β-catenin nuclear translocation via a paracrine mechanism in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (PASMC), thus leading to excessive pulmonary vascular remodeling. The combination of poor alveolar and vascular development as well as increased vascular remodeling results in pulmonary hypertension. The CTGF-induced infiltration via β-catenin-dependent and/or independent mechanisms further disrupts alveolar and vascular development and induces pulmonary hypertension.

GRANTS

This work was supported by funding from National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant K08 HD046582, Bank of America Charitable Grant, Project Newborn from the University of Miami, American Heart Association Grant and Micah Batchelor Award from the Batchelor Foundation.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

REFERENCES

- 1. Abreu JG, Ketpura NI, Reversade B, De Robertis EM. Connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) modulates cell signaling by BMP and TGF-β. Nat Cell Biol 4: 599–604, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alejandre-Alcázar MA, Kwapiszewska A, Reiss I, Amarie OV, Marsh LM, Sevilla-Pérez J, Wygrecka M, Eul B, Köbrich S, Hesse M, Schermuly RT, Seeger W, Eickelberg O, Morty RE. Hyperoxia modulates TGF-β/BMP signaling in a mouse model of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 292: L537–L549, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Allen JT, Knight RA, Bloor CA, Spiteri MA. Enhanced insulin-like growth factor binding protein-related protein 2 (Connective tissue growth factor) expression in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and pulmonary sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 21: 693–700, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Aslam M, Baveja R, Liang OD, Fernandez-Gonzalez A, Lee C, Mitsialis SA, Kourembanas S. Bone marrow stromal cells attenuate lung injury in a murine model of neonatal chronic lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 180: 1122–1130, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bry K, Whitsett JA, Lappalainen U. Interleukin-1beta causes pulmonary inflammation, emphysema, and airway remodeling in the adult murine lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 36: 32–42, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chang CC, Lin MT, Lin BR, Jeng YM, Chen ST, Chu CY, Chen RJ, Chang KJ, Yang PC, Kuo ML. Effect of connective tissue growth factor on hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha degradation and tumor angiogenesis. J Natl Cancer Inst 98: 984–995, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen CM, Wang LF, Chou HC, Lang YD, Lai YP. Up-regulation of connective tissue growth factor in hyperoxia-induced lung fibrosis. Pediatr Res 62: 128–133, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Coalson JJ, Winter VT, Delemos RA. Decreased alveolarization in baboon survivors with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 152: 640–646, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Crean JK, Furlong F, Finlay D, Mitchell D, Murphy M, Conway B, Brady HR, Godson C, Martin F. Connective tissue growth factor [CTGF]/CCN2 stimulates mesangial cell migration through integrated dissolution of focal adhesion complexes and activation of cell polarization. FASEB J 18: 1541–1543, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dasgupta C, Sakurai R, Wang Y, Guo P, Ambalavanan N, Torday JS, Rehan VK. Hyperoxia-induced neonatal rat lung injury involves activation of TGF-β and Wnt signaling and is protected by rosiglitazone. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 296: L1021–L1041, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dean RA, Butler GS, Hamma-Kourbali Y, Delbe J, Brigstock DR, Courty J, Overall CM. Identification of candidate angiogenic inhibitors processed by matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP2) in cell-based proteomic screens: disruption of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)/heparin affin regulatory peptide (pleiotrophin) and VEGF/connective tissue growth factor angiogenic inhibitory complexes by MMP2 proteolysis. Mol Cell Biol 27: 8454–8465, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Deng Y, Chen P, Wang Y, Yin D, Koeffler HP, Li A, Tong X, Xie D. Connective tissue growth factor is overexpressed in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and promotes tumorigenicity through β-catenin-T-cell factor/Lef signaling. J Biol Chem 282: 36571–36581, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dwivedi A, Sala-Newby GB, George SJ. Regulation of cell-matrix contacts and beta-catenin signaling in VSMC by integrin-linked kinase: implications for intimal thickening. Basic Res Cardiol 103: 244–256, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fouron JC, LeGuennec JC, Villemont D, Perreault G, Davignon A. Value of echocardiography in assessing the outcome of BPD. Pediatrics 65: 529–535, 1980 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Frank DB, Lowery J, Anderson L, Brink M, Reese J, de Caestecter M. Increased susceptibility to hypoxic pulmonary hypertension in Bmpr2 mutant mice is associated with endothelial dysfunction in the pulmonary vasculature. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 294: L98–L109, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Friedrich EB, Clever YP, Wassmann S, Werner N, Bohm M, Nickenig G. Role of integrin-linked kinase in vascular smooth muscle cells: regulation by statins and angiotensin II. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 349: 883–889, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fu M, Zhang J, Zhu X, Myles DE, Willson TM, Liu X, Chen YE. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma inhibits transforming growth factor beta-induced connective tissue growth factor expression in human aortic smooth muscle cells by interfering with Smad3. J Biol Chem 276: 45888–45894, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Grotendorst GR. Connective tissue growth factor: a mediator of TGF-beta action on fibroblasts. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 8: 171–179, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Grover TR, Parker TA, Zenge JP, Markham NE, Kinsella JP, Abman SH. Intrauterine hypertension decreases lung VEGF expression and VEGF inhibition causes pulmonary hypertension in the ovine fetus. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 284: L508–L517, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gurrieri C, Piazza F, Gnoato M, Montini B, Biasutto L, Gattazzo C, Brunetta E, Cabrelle A, Cinetto F, Niero R, Facco M, Garbisa S, Calabrese F, Semenzato G, Agostini C. 3-(2,4-Dichlorophenyl)-4-(1-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)-1H-pyrrole-2,5-dione (SB216763), a glycogen synthase kinase-3 inhibitor, displays therapeutic properties in a mouse model of pulmonary inflammation and fibrosis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 332: 785–794, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hannigan GE, Lelung-Hagesteijin C, Fitz-Gibbon L, Coppolino MG, Radeva G, Filmus J, Bell JC, Dedhar S. Regulation of cell adhesion and anchorage-dependent growth by a new β1-integrin-linked protein kinase. Nature 379: 91–96, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Heng ECK, Huang Y, Black SA. Trackman PC, CCN2, connective tissue growth factor, stimulates collagen deposition by gingival fibroblasts via module 3 and alpha6- and beta1 integrins. J Cell Biochem 98: 409–420, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Husain AN, Siddiqui NH, Stocker JT. Pathology of arrested acinar development in post surfactant bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Hum Pathol 29: 710–717, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Inoki I, Shiomi T, Hashimoto G, Enomoto H, Nakamura H, Makino KI, Ikeda E, Takata S, Kobayashi KI, Okada Y. Connective tissue growth factor binds vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and inhibits VEGF-induced angiogenesis. FASEB J 16: 219–221, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jedsadayanmata A, Chen CC, Kireeva ML, Lau LF, Lam SC. Activation-dependent adhesion of human platelets to Cyr61 and Fisp12/mouse connective tissue growth factor is mediated through integrin αIIbβ3. J Biol Chem 274: 24321–24327, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jernigan KK, Cselenyi CS, Thorne CA, Hanson AJ, Tahinci E, Halicek N, Oldham WM, Lee LA, Hamm HE, Hepler JR, Kozasa T, Linder ME, Lee E. Gβγ activates GSK3 to promote LRP6-mediated β-catenin transcriptional activity. Sci Signal 3: ra37, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jiang Z, Tao M, Omalley KA, Wang D, Ozaki CK, Berceli SA. Established neointimal hyperplasia in vein grafts expands via TGF-β-mediated progressive fibrosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 297: H1200–H1207, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jobe A. The new BPD: an arrest of lung development. Pediatr Res 46: 641–643, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jobe AH, Bancalari E. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 163: 1723–1729, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Konigshoff M, Eickelberg O. Wnt signaling in lung disease a failure or a regeneration signal? Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 42: 21–31, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kuiper EJ, Roestenberg P, Ehlken C, Lambert V, van Treslong-de Groot HB, Lyons KM, Agostini HJ, Rakic JM, Klaassen I, Van Noorden CJ, Goldschmeding R, Schlingemann RO. Angiogenesis is not impaired in connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) knock-out mice. J Histochem Cytochem 11: 1139–1147, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kundi R, Hollenbeck ST, Yamanouchi D, Herman BC, Edlin R, Ryer EJ, Wang C, Tsai S, Liu B, Kent KC. Arterial gene transfer of the TGF-beta signaling protein Smad3 induces adaptive remodeling following angioplasty: a role for CTGF. Cardiovasc Res 84: 326–335, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Le Cras TD, Markham NE, Tuder RM, Voelkel NF, Abman SH. Treatment of newborn rats with a VEGF receptor inhibitor causes pulmonary hypertension and abnormal lung structure. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 283: L555–L562, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Leask A, Abraham DJ. All in the CCN family: essential matricellular signaling modulators emerge from the bunker. J Cell Sci 119: 4803–4810, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lee YS, Bryun J, Kim JA, Lee JS, Kim KL, Suh YL, Kim JM, Jang HS, Lee JY, Shin IS, Suh W, Jeon ES, Kim DK. Monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension correlates with upregulation of connective tissue growth factor expression in the lung. Exp Mol Med 37: 27–35, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Liu BC, Li MX, Zhang JD, Liu XC, Zhang XL, Phillips AO. Inhibition of integrin-linked kinase via a siRNA expression plasmid attenuates connective tissue growth factor-induced human proximal tubular epithelial cells to mesenchymal transition. Am J Nephrol 28: 143–151, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. McDonald PC, Fielding AB, Dedhar S. Integrin-linked kinase essential roles in physiology and cancer biology. J Cell Sci 121: 3121–3132, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mercurio S, Latinkic B, Itasaki N, Krumlauf R, Smith JC. Connective-tissue growth factor modulates WNT signalling and interacts with the WNT receptor complex. Development 131: 2137–2147, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nho RS, Xia H, Kahm J, Kleidon J, Diebold D, Henke CA. Role of integrin-linked kinase in regulating phosphorylation of Akt and fibroblast survival in type I collagen matrices through a beta1 integrin viability signaling pathway. J Biol Chem 280: 26630–26639, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nishida T, Kawaki H, Baxter RM, DeYoung RA, Takigawa M, Lyons KM. CCN (connective tissue growth factor) is essential for extracellular matrix production and integrin signaling in chondrocytes. J Cell Commun Signal 1: 45–58, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Perl AK, Zhang L, Whitsett JA. Conditional expression of genes in the respiratory epithelium in transgenic mice: cautionary notes and toward building a better mouse trap. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 40: 1–3, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rice WR, Conkright JJ, Na CL, Ikegami M, Shannon JM, Weaver TE. Maintenance of the mouse type II cell phenotype in vitro. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 283: L256–L264, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sanchez-Lopez E, Rayego S, Rodrigues-Diez R, Rodriguez JS, Rodrigues-Diez R, Rodriguez-Vita J, Carvajal G, Aroeira LS, Selgas R, Mezzano SA, Ortiz A, Egido J, Ruiz-Ortega M. CTGF promotes inflammatory cell infiltration of the renal interstitium by activating NF-kappaB. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 1513–1526, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sato S, Nagaoka T, Hasegawa M, Tamatani T, Nakanishi T, Takigawa M, Takehara K. Serum levels of connective tissue growth factor are elevated in patients with systemic sclerosis: association with extent of skin sclerosis and severity of pulmonary fibrosis. J Rheumatol 27: 149–154, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Schwartz MA, Ginsberg MH. Networks and crosstalk: integrin signaling spreads. Nat Cell Biol 4: E65–E68, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Speer CP. Inflammation and bronchopulmonary dysplasia: a continuing story. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 11: 354–362, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Stenmark KR, Abman SH. Lung vascular development: implications for pathogenesis of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Annu Rev Physiol 67: 623–661, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Thebaud B, Abman SH. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia: where have all the vessels gone? Roles of angiogenic growth factors in chronic lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 175: 978–985, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wallace MJ, Probyn ME, Zahra VA, Crossley K, Cole TJ, Davis PG, Morley CJ, Hooper SB. Early biomarkers and potential mediators of ventilation-induced lung injury in very preterm lambs. Respir Res 10: 19, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wu S, Capasso L, Lessa A, Peng JH, Kasisomayajula K, Rodriguez M, Suguihara C, Bancalari E. High tidal volume ventilation up-regulates CTGF expression in the lung of newborn rats. Pediatr Res 63: 245–250, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wu S, Platteau A, Chen S, McNamara M, Whitsett J, Bancalari E. Conditional over-expression of connective tissue growth factor disrupts postnatal lung development. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 42: 552–563, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Xu C, Kim NG, Gumbiner BM. Regulation of protein stability by GSK3 mediated phosphorylation. Cell Cycle 8: 4032–4039, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Yang M, Huang H, Li J, Li D, Wang H. Tyrosine phosphorylation of the LDL receptor-related protein (LRP) and activation of the ERK pathway are required for connective tissue growth factor to potentiate myofibroblast differentiation. FASEB J 18: 1920–1931, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Young KC, Torres E, Hatzistergos E, Hehre D, Suguihara C, Hare JM. Inhibition of the SDF-1/CXCR4 axis attenuates neonatal hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Circ Res 104: 1293–1301, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yu L, Quinn DA, Garg HG, Hales CA. Deficiency of the NHE1 gene prevents hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension and vascular remodeling. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 177: 1276–1284, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Yu W, Fang X, Ewald A, Wong K, Hunt A, Werb Z, Matthay MA, Mostov K. Formation of cysts by alveolar type II cells in three-dimensional culture reveals a novel mechanism for epithelial morphogenesis. Mol Biol Cell 18: 1693–1700, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]