Abstract

We have observed that in chloralose-anesthetized animals, gastric distension (GD) typically increases blood pressure (BP) under normoxic normocapnic conditions. However, we recently noted repeatable decreases in BP and heart rate (HR) in hypercapnic-acidotic rats in response to GD. The neural pathways, central processing, and autonomic effector mechanisms involved in this cardiovascular reflex response are unknown. We hypothesized that GD-induced decrease in BP and HR reflex responses are mediated during both withdrawal of sympathetic tone and increased parasympathetic activity, involving the rostral (rVLM) and caudal ventrolateral medulla (cVLM) and the nucleus ambiguus (NA). Rats anesthetized with ketamine and xylazine or α-chloralose were ventilated and monitored for HR and BP changes. The extent of cardiovascular inhibition was related to the extent of hypercapnia and acidosis. Repeated GD with both anesthetics induced consistent falls in BP and HR. The hemodynamic inhibitory response was reduced after blockade of the celiac ganglia or the intraabdominal vagal nerves with lidocaine, suggesting that the decreased BP and HR responses were mediated by both sympathetic and parasympathetic afferents. Blockade of the NA decreased the bradycardia response. Microinjection of kainic acid into the cVLM reduced the inhibitory BP response, whereas depolarization blockade of the rVLM decreased both BP and HR inhibitory responses. Blockade of GABAA receptors in the rVLM also reduced the BP and HR reflex responses. Atropine methyl bromide completely blocked the reflex bradycardia, and atenolol blocked the negative chronotropic response. Finally, α1-adrenergic blockade with prazosin reversed the depressor. Thus, in the setting of hypercapnic-acidosis, a sympathoinhibitory cardiovascular response is mediated, in part, by splanchnic nerves and is processed through the rVLM and cVLM. Additionally, a vagal excitatory reflex, which involves the NA, facilitates the GD-induced decreases in BP and HR responses. Efferent chronotropic responses involve both increased parasympathetic and reduced sympathetic activity, whereas the decrease in BP is mediated by reduced α-adrenergic tone.

Keywords: sympathoinhibition, vagal excitation, γ-aminobutyric acid, rostal and caudal ventrolateral medulla, nucleus ambiguus

gastric distention commonly leads to transient increases in blood pressure. In this regard, we and others (5, 12, 16, 26, 36) have previously shown that repeated gastric distention induces consistent increases in mean arterial blood pressure in normoxic normocapnic rats and cats anesthetized with α-chloralose. Splanchnic nerve denervation virtually eliminates the distention-induced excitatory cardiovascular reflex (12, 16). Splanchnic nerve stimulation leads to increases in the discharge activity of neurons in the rostral ventrolateral medulla (rVLM), among many other brain stem nuclei (13, 14, 35). Thus, the rVLM and likely other medullary nuclei process cardiovascular sympathoexcitatory reflex responses during mechanical stimulation of the stomach wall.

In addition to the well-studied sympathoexcitatory responses, gastric distention has less commonly been found to be capable of reflexly decreasing blood pressure (21, 21, 27). The reason for these dichotomous reflex responses to gastric stretch is uncertain. However, we (8) also have recently observed in a preliminary study that gastric distention can induce inhibitory cardiovascular responses consisting of decreases in blood pressure and heart rate. Careful examination of our data showed that repeatable decreases in blood pressure and heart rate in response to gastric distension in ketamine-xylazine-anesthetized rats were associated with hypercapnia and acidosis.

A rise in CO2 and the associated increased concentration of protons stimulates both central and peripheral chemoreceptors (9). Although the stimulation of peripheral and central chemoreceptors increases the respiratory rate and causes a reflex cardiovascular pressor response in freely breathing humans (3, 31), activation of the central chemoreceptors during controlled ventilation prevents the secondary pulmonary reflex response and thus reduces sympathetic drive, frequently leading to a hypotensive response (4, 24). Little work has been conducted to evaluate the potential of chemoreceptor stimulation (for example, during hypercapnia-acidosis) to modify what are normally excitatory reflex responses. In this regard, the only observation has been that hypercapnia in a rat model significantly attenuates splanchnic sympathetic efferent nerve activity during brief tibial nerve stimulation in association with inhalation of 5% CO2, demonstrating modulation of a somatosympathetic reflex by hypercapnia (17). However, no studies have demonstrated that normal excitatory responses can be converted to inhibitory reflexes by hypercapnia and acidosis, and no studies have examined the afferent, central, and efferent mechanisms underlying depressor responses in this setting.

As such, the goal of the present studies was to evaluate the relationship between arterial CO2 (and low pH) and the reflex response to gastric distension in rats. To understand better the underlying mechanisms, the afferent pathways, central regions of integration, and efferent autonomic mechanisms involved in the reflex responses were determined. We hypothesized that mechanical stimulation of the stomach elicits both sympathoinhibitory and parasympathoexcitatory reflex responses during hypercapnia in rats. We further hypothesized that the nucleus ambiguus as well as the caudal ventrolateral medulla (cVLM) and rVLM are involved in the inhibitory reflex response. Finally, we hypothesized that efferent cholinergic and both α- and β-adrenergic systems contribute to the inhibitory responses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Surgical Preparations

Experimental preparations and protocols were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of California (Irvine, CA). This study conformed with the American Physiological Society's “Guiding Principles for Research Involving Animals and Human Beings” (2002). Studies were performed on adult Sprague-Dawley male rats (400–600 g). After an overnight fast of 18 h, anesthesia was induced with ketamine (100 mg/kg im) and xylazine (10 mg/kg im). Additional doses of xylazine (0.02 mg/kg iv) were given as necessary to maintain an adequate level of anesthesia, as determined by the lack of response to noxious toe pinch, a respiratory pattern that followed the respirator, as well as a stable blood pressure and heart rate. The influence of α-chloralose on the reflex responses also was examined in a subgroup of animals. For this protocol, anesthesia was induced with ketamine (100 mg/kg im) followed by α-chloralose (5 mg/kg iv). Additional doses of α-chloralose (3 mg/kg iv) were administered as needed. A femoral vein was cannulated for the administration of fluids. The trachea was exposed and intubated to artificially ventilate animals with a respirator (model 663, Harvard Apparatus). A femoral artery was cannulated and attached to a pressure transducer (P23XL, Ohmeda) to monitor blood pressure. Heart rate was derived from the pulsatile blood pressure signal. To establish hypercapnia in a group of animals, 5% CO2 was added to the O2-enriched room air. Arterial blood gases and pH were measured periodically with a blood gas analyzer (ABL5, Radiometer America). Protocol A examined reflex responses with variable levels of Pco2, which ranged between 31 and 68 mmHg. Alternatively, in protocol B (1–7), Pco2 was maintained between 42 and 55 mmHg (constant condition with repeated gastric distention) and Po2 was 200 ± 45 mmHg by adjusting the rate of delivery of 5% CO2 to the enriched inspired O2. Arterial pH varied between 7.22 and 7.34. Body temperature, which was monitored with a rectal thermistor (model 44TD), was kept between 36 and 38°C with a heating pad and lamp.

An unstressed 2-cm diameter latex balloon (Traub) was attached to a polyurethane tube (3-mm diameter) and inserted into the stomach through the mouth and esophagus. The balloon was palpated manually during insertion as it passed through the esophagus into the stomach to confirm positioning of the balloon inside the stomach. A syringe was attached to the cannula to inflate and deflate the balloon with air, while a manometer through a T-connection was used to monitor balloon pressure. Transmural pressure was determined by measuring the pressure required to inflate the balloon with the various volumes of air before it was inserted into the stomach (12). Distention pressures were selected to fall within the range that a rat normally experiences during the ingestion of food and fluids in a single meal (2, 6). To induce decreases in blood pressure and heart rate, the balloon was inflated inside the stomach. Decreases in blood pressure and heart rate were observed within 30 s of inflation. The balloon was deflated within 30 s after reaching the maximum decrease in blood pressure. We did not include animals in the study if the balloon was verified postmortem to be in the esophagus.

Experimental Procedures

The celiac ganglia and intra-abdominal vagal nerves were located and isolated through a small midline incision in the abdomen. A pledget soaked with 0.1 ml of 1% lidocaine was used to transiently block nerve conduction through the abdominal sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves.

Other animals were placed in a stereotaxic head frame to position their heads with the floor of the fourth ventricle in a horizontal position. A partial craniotomy was performed to expose the medulla to allow access to the nucleus ambiguus, rVLM, and cVLM. A microinjection probe was inserted with visual approximation at a 90° angle relative to the dorsal surface of the medulla, 1.8 mm lateral either right or left from the midline, 1.5 mm rostral to the obex, at a depth of 2.3 mm to access the nucleus ambiguus. To reach the rVLM, the probe was positioned 2.3 mm lateral to the midline, 1.5 mm rostral to the obex, at a depth of 3.3 mm. The probe was lowered into the cVLM in a position perpendicular to the dorsal surface, 0.5 mm caudal to the obex, 2.0 mm lateral to the midline, and 3.0 mm in depth. A modified CMA microdialysis AB probe that was 14 mm long (CMA, Stockholm, Sweden, tip diameter: 0.24 mm) and lacked the microdialysis membrane was advanced toward the ventral surface to reach the nucleus ambiguus, rVLM, and cVLM for unilateral microinjection using coordinates taken from the atlas of Paxinos and Watson (23). The probe was connected to a CMA 402 syringe pump to deliver 50 nl at a rate of 0.3 μl/min over a 10-s period 2 min before the next gastric distention.

Injection sites were marked with 50 nl of Chicago sky blue dye (5% in 0.5 M sodium acetate) at the end of each experiment after the administration of drugs into the rVLM, cVLM, or nucleus ambiguus. Thereafter, rats were euthanized under deep anesthesia with additional ketamine and xylazine followed by saturated KCl. The stomach was exposed to confirm placement of the balloon. The medulla was removed and submerged in 4% paraformaldehyde for at least 4 days. Frozen 40-μm coronal sections were cut with a CM 1850 cryostat microtome (Leica) to confirm microinjection sites histologically. Dye spots were identified with a binocular microscope. Microinjection sites in the medulla were plotted with Corel Presentation software on coronal sections reconstructed using the atlas of Paxinos and Watson (23) as a guide.

Chemicals

Chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) with the exception of lidocaine (Alpharma, Baltimore, MD), atropine methyl bromide (City Chemical, West Haven, CT), and prazosin (Tocris Bioscience, Ellisville, MD). The depolarizing agent kainic acid (KA; 1 mM) and the GABAA antagonist gabazine (27 mM) were dissolved in normal saline (19, 36). We microinjected 50 nl of KA, gabazine, or saline unilaterally into the nucleus ambiguus, cVLM, or rVLM. Of note, several of our previous studies (5, 12, 36) have demonstrated significant blockade with unilateral administration. A 5 × 5-mm pledget soaked with 0.1 ml of 1% lidocaine was used to block the activity of the celiac ganglia and abdominal vagus (18). Atropine methyl bromide, a muscarinic cholinergic antagonist, and atenolol, a β-adrenoceptor antagonist, which do not cross the blood-brain barrier (1, 10), were dissolved in saline and administered (1 and 0.1 mg/kg, respectively) intravenously. Prazosin, an α1-adrenergic blocker that mainly affects blood vessels and postsynaptic α1-adrenoceptors, was dissolved in saline and ethanol and delivered intravenously (10 μg/kg) (34).

Experimental Protocols

Protocol A.

HYPERCAPNIA DOSE-RESPONSE CURVE.

Gastric distention-evoked reflex decreases in blood pressure and heart rate were examined during different levels of CO2 (using a random order of application) in 12 rats anesthetized with ketamine-xylazine during inhalation of a mixture of 5% CO2 and room air enriched with O2. Concomitantly, arterial blood gases were measured to correlate levels of Pco2 and pH with the hemodynamic reflex responses to gastric distension induced by slowly inflating the balloon over a 10-s period. Four animals exposed to wide range of hypercapnia were examined for baseline changes in blood pressure and heart rate. Reflex responses to gastric distension were examined in five other animals anesthetized with ketamine and α-chloralose.

Protocol B.

1. REPEATABILITY OF CARDIOVASCULAR INHIBITORY RESPONSES.

Gastric distention was induced by slowly inflating the balloon over a 10-s period with a volume ranging from 5 to 8 ml of air while elevated Pco2 was held constant. Consistent responses were evaluated in five animals. Once maximal decreases of blood pressure and heart rate were attained (generally within 30 s), the injected air was withdrawn slowly from the balloon. Peak inhibitory blood pressure and heart rate responses were noted typically within 20–30 s after inflation. Ten- to fifteen-minute recovery intervals were necessary to prevent attenuation of the cardiovascular reflex responses.

2. ROLES OF SYMPATHETIC AND PARASYMPATHETIC AFFERENT PATHWAYS.

Lidocaine was used to block spinal and vagal afferent transmission during gastric distention in 10 rats. A lidocaine-soaked pledget was placed on the abdominal celiac ganglion or vagus nerves after two repeatable distensions to establish control responses. Thereafter, three additional gastric distention responses were evaluated.

3. DEPOLARIZATION BLOCKADE IN THE NUCLEUS AMBIGUUS, CVLM, AND RVLM.

After the responses had been assessed during two gastric distensions, changes in blood pressure and heart rate during repeated visceral stimulation were evaluated after the microinjection of KA or saline unilaterally into the nucleus ambiguus, cVLM, or rVLM. The actions of KA in these nuclei were evaluated in groups of four, five, and seven animals, respectively. Saline was also microinjected into each of the 3 nuclei in 12 other rats as a control.

4. ROLE OF GABA IN THE RVLM.

Gabazine was microinjected unilaterally into the rVLM of five rats during repeated gastric distention. Thus, after two consistent sets of hemodynamic responses were observed, GABAA receptors were blocked, and three additional reflex responses were evaluated.

5. PERIPHERAL CHOLINERGIC REGULATION OF HEART RATE.

Atropine methyl bromide was administered (intravenously) to five rats after the demonstration of two repeatable reflex responses to gastric distention. Subsequently, three additional blood pressure and heart rate responses were evaluated to determine the role of peripheral cholinergic muscarinic receptor activation in this inhibitory reflex.

6. PERIPHERAL β-ADRENERGIC BLOCKADE.

Atenolol was injected intravenously after the establishment of two repeatable responses to gastric distension in six rats. Three additional distensions were then recorded to evaluate the role of cardiac sympathetic adrenoreceptor activation in the distension reflex response.

7. PERIPHERAL α1-ADRENOCEPTOR BLOCKADE.

After four repeated gastric distention responses (2 controls and 2 vehicle controls), the influence of intravenous prazosin on the inhibitory responses was evaluated during three additional distensions.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as means ± SE. Changes in mean arterial pressure and heart rate are presented as bar histograms. The decreases in blood pressure and heart rate before and after the delivery of experimental drugs or saline were compared by one-way ANOVA followed post hoc with the Student-Newman-Keuls test. Data were plotted and analyzed with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for normal data distribution and normalized when necessary with Sigma Plot (Jandel Scientific). Comparisons of increases in Pco2 or decreases in pH with the reflex depressor responses were evaluated by linear regression analysis using the least-squares method with the Durbin-Watson statistic (Sigma Plot). Similar analyses were performed for comparison with the bradycardia responses. Correlations between baseline values for blood pressure and heart rate changes also were evaluated by least-squares linear regression analyses. All statistical analyses were performed with Sigma Stat (Jandel Scientific). A probability level of 0.05 was used to detect significant differences.

RESULTS

Protocol A: Reflex Responses to Variable Levels of Pco2

In this protocol, Pco2 ranged between 31 and 64 mmHg and pH ranged between 7.40 and 7.12.

Hemodynamic responses to hypercapnia-acidosis.

We observed progressively larger depressor and bradycardia responses to gastric distension in 12 animals anesthetized with ketamine-xylazine as we increased Pco2 (Fig. 1A). Additionally, pH was directly related to decreases in blood pressure and heart rate responses (Fig. 1B). We noted transient increases in baseline blood pressure but not heart rate when Pco2 was elevated (Fig. 1C). However, the changes in blood pressure had resolved before the gastric distension. We observed similar changes in blood pressure induced by gastric distention in animals anesthetized with ketamine and α-chloralose as Pco2 was increased (Fig. 2). Baseline blood pressure and heart rate were 96 ± 4 mmHg and 315 ± 16 beats/min, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Relationships among Pco2, pH, mean arterial blood pressure (BP) changes (ΔMAP), or heart rate [HR; in beats/min (bpm)]. A: inverse relationship between Pco2 and ΔMAP and HR in response to gastric distention. B: significant direct relationship between pH, BP, and HR. C: increase in baseline BP with increased CO2. PaCO2, arterial Pco2.

Fig. 2.

Relationships between Pco2 and ΔMAP or HR in a single group of animals anesthetized with α-chloralose. Similar to xylazine-anesthethized animals, changes in BP and HR were inversely related to increases in Pco2 during gastric distention.

Protocol B: Reflex Responses During Constant Elevated Pco2

Animals in this protocol had an average Pco2 of 49 ± 3 and a pH of 7.28 ± 0.04.

Repeatability of cardiovascular inhibitory responses.

In the time control group of five rats, we observed consistent decreases in blood pressure and heart rate with repeated gastric distention applied every 10 min while a constant level of hypercapnia-acidosis was maintained (Fig. 3). Changes in baseline blood pressures associated with hypercapnia had resolved before the gastric distension. Furthermore, baseline BP in these animals remained constant over the duration of the experiment.

Fig. 3.

Hypercapnic rats subjected to repeated gastric distention every 10 min. The stimulation of mechanosensitive receptors on the wall of the stomach resulted in consistent decreases in both BP (A) and HR (B) responses. Values above each bar indicate baseline MAP and HR (means ± SE) before gastric distention. Bars represent depressor and bradycardia reflex responses after distention of the stomach every 10–15 min.

Roles of sympathetic and parasympathetic afferent pathways.

Lidocaine application to either the celiac ganglion or the abdominal vagal nerves transiently reduced the hemodynamic responses to gastric distension by 61% and 71%, respectively (Fig. 4, I and II).

Fig. 4.

MAP responses to gastric distension before and after chemical denervation of intra-abdominal celiac ganglion/sympathetic afferents (I) or vagal afferents (II) with 1% lidocaine. Lidocaine denervation transiently attenuated the cardiovascular depressor reflexes. Original data before (a and d), immediately after (b and e), and 30 min after (c and f) chemical denervation of the celiac ganglion (I) and abdominal vagus (II) of the inhibitory BP and HR responses are shown above the histograms. Values above each bar indicate baseline MAP and HR (means ± SE) before gastric distention. Bars represent depressor and bradycardia reflex responses after distention of the stomach every 10–15 min.*P < 0.05.

KA in the rVLM and cVLM.

KA microinjected into the rVLM or cVLM reduced the extent of the cardiovascular inhibitory responses. Saline (Table 1) microinjection did not influence the reflex responses. Changes in both blood pressure and heart rate were reduced by depolarization blockade of the rVLM (Fig. 5I, A and B), whereas KA in the cVLM attenuated only the blood pressure response (Fig. 5II, A and B). Basal blood pressure and heart rate were unaffected by depolarization blockade in the cVLM and rVLM.

Table 1.

Gastric distention-induced blood pressure and HR responses to microinjection of saline into the rVLM, cVLM, and nucleus ambiguus

| rVLM |

cVLM |

Nucleus ambiguus |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔMAP, mmHg | ΔHR, beats/min | ΔMAP, mmHg | ΔHR, beats/min | ΔMAP, mmHg | ΔHR, beats/min | |

| Before saline microinjection | −41 ± 11 | −36 ± 18 | −47 ± 9 | −17 ± 7 | −36 ± 6 | −47 ± 20 |

| After saline microinjection | −39 ± 9 | −44 ± 20 | −38 ± 9 | −17 ± 6 | −35 ± 6 | −60 ± 22 |

Values are means ± SE; n = 4 each. rVLM and cVLM, rostral and caudal ventrolateral medulla, respectively; MAP, mean arterial pressure; HR, heart rate.

Fig. 5.

Cardiovascular responses of gastric distention after unilateral blockade of the rostral ventrolateral medulla (rVLM), caudal ventrolateral medulla (cVLM), and nucleus ambiguus (Nuc Amb). Blockade of the rVLM with either kainic acid (KA) or gabazine reduced both the inhibitory BP and HR responses (I and IV). Microinjection of KA into the cVLM attenuated the hypotensive response (II, A), whereas the bradycardia was unaffected (II, B). On the other hand, blockade of the nucleus ambiguus did not attenuate the hypotensive response (III, A) but did attenuate the chronotropic response (III, B). Values above each bar indicate baseline MAP and HR (means ± SE) before gastric distention. Bars represent depressor and bradycardia reflex responses after distention of the stomach every 10–15 min. *P < 0.05.

KA in the nucleus ambiguus.

Unilateral depolarization blockade of neurons in the nucleus ambiguus inhibited the heart rate response but not the blood pressure response to gastric distention (Fig. 5III, A and B). Baseline heart rate did not change in this group. Microinjection of saline did not influence the cardiovascular responses (Table 1).

Gabazine in the rVLM.

Like KA, microinjection of gabazine into the rVLM attenuated both the blood pressure and heart rate responses to gastric distention (Fig. 5IV, A and B), whereas baseline blood pressure and heart rate were unaffected.

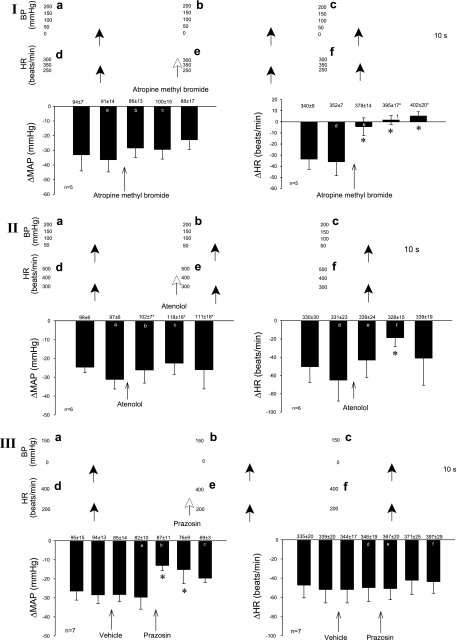

Peripheral muscarinic cholinergic blockade.

Atropine methyl bromide eliminated the bradycardia but not the blood pressure response to gastric distention (Fig. 6I). Baseline heart rate was increased by cholinergic blockade.

Fig. 6.

Role of the sympathetic adrenergic and parasympathetic cholinergic systems in gastric distention-induced reflex responses in hypercapnic rats. Cholinergic blockade with atropine methyl bromide attenuated the HR but not the BP reflex changes (I). β-Adrenergic blockade with atenolol also reduce the negative chronotropic response, whereas the depressor response was unaffected (II). Prazosin, an α-adrenergic antagonist, reduced the depressor but not HR responses (III). Original data are shown above the histograms and correspond to a–f in I–III. Values above each bar indicate baseline MAP and HR (means ± SE) before gastric distention. Bars represent depressor and bradycardia reflex responses after distention of the stomach every 10–15 min.*P < 0.05.

Peripheral β-adrenergic blockade.

Atenolol partially reversed the distension-evoked decrease in heart rate (71%), whereas the blood pressure response was not affected (Fig. 6II).

Peripheral α-adrenergic blockade.

Prazosin significantly reversed the depressor responses to gastric distention by 56% but did not influence the changes in heart rate (Fig. 6III).

Anatomical location of microinjection sites.

All injections found to be located within the rVLM, cVLM, and nucleus ambiguus were included in the data analysis. Two sites found to be medial and ventral to the nucleus ambiguus that did not alter the reflex response were excluded (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Composite map showing microinjection sites in the nucleus ambiguus (N. Amb), cVLM, and rVLM. O, outside the nucleus ambiguus; NTS, nucleus tractus solitarii; py, pyramidal tract; AP, area postrema; ●, KA microinjection site; *gabazine microinjection site.

DISCUSSION

We (12, 16) have previously shown that gastric distention in normocapnic cats and rats anesthetized with α-chloralose typically induces sympathoexcitatory reflex responses that are mediated through the splanchnic nerve and spinal afferents. The present study shows that the activation of mechanosensitive receptors in the stomach decreases blood pressure and heart rate in hypercapnic-acidotic rats anesthetized with ketamine and xylazine and that the sympathoexcitatory response observed during normocapnic conditions is converted to a sympathoinhibitory (and parasympathoexcitatory) response in the presence of high CO2 and low pH. In fact, the magnitude of the blood pressure and heart rate inhibitory reflex responses increased linearly with increasing Pco2. Inhibition of the cardiovascular responses was reduced by interruption of sympathetic as well as parasympathetic abdominal afferent neurotransmission with lidocaine, indicating that both spinal and vagal sensory pathways participate in the decrease in blood pressure and heart rate during gastric distension. We also observed that several medullary regions in the brain, including the nucleus ambiguus, cVLM, and rVLM, process the inhibitory reflexes, since depolarization blockade with KA in each of these regions substantially modified the reflex hemodynamic responses. Sympathoinhibition of blood pressure in the rVLM involves, in part, GABAA receptors, since gabazine likewise reduced the reflex. Furthermore, the peripheral cholinergic and β-adrenergic receptor systems (activation and withdrawal, respectively) contribute to the inhibitory chronotropic hemodynamic responses, whereas α-adrenergic receptors (withdrawal) account for the inhibitory blood pressure responses.

In the intact, freely breathing animal, hypercapnia stimulates both central and peripheral chemoreceptors to increase breathing frequency and blood pressure, the latter through an increase in sympathetic activity (31). Furthermore, in the O2-enriched condition, which applies to our model (Po2: 200 ± 45 mmHg), the responsiveness of the peripheral chemoreceptors to hypercapnia is reduced (11) to an extent that is comparable to peripheral chemoreceptor denervation (7), suggesting that the hemodynamic responses observed in the present study were influenced mainly by central chemoreceptors. Our findings are consistent with previous observations of progressive elevations in baseline mean arterial blood pressure with increasing arterial Pco2 in vagal sinoaortic-denervated rats (20). Thus, it is likely that central chemoreceptors activation during hypercapnia increased arterial blood pressure.

We observed a progressively greater hemodynamic inhibitory reflex response to gastric distension as the Pco2 increased during stimulation of the central chemoreceptors by room air enriched with CO2 and O2. Although there was a transient increase in baseline blood pressure in response to the increase in Pco2, this effect had dissipated by the time of visceral reflex stimulation. Furthermore, after the stabilization of arterial blood gases in protocol B (elevated Pco2 and Po2 and low pH), we found that rats subjected to gastric distention manifested repeatable reflex decreases in blood pressure and heart rate during the course of the experiment. Pco2-evoked changes in baseline blood pressure did not influence the depressor responses since Pco2 remained stable during repeated gastric distension in all except protocol A (Fig. 1). Additionally, baseline blood pressures in our previous (normocapnia) and present (hypercapnia) studies were very similar (12, 36, 39, 39, 39) Hence, alterations in baseline blood pressure in hypercapnic-acidotic animals do not appear to be a factor in the depressor responses.

A number of studies have examined reflex responses to hypercapnia-acidosis. Two studies (25, 33) have demonstrated an increase in sympathetic discharge during activation of the central chemoreceptors in the absence of baroreceptor input with elevated CO2. In contrast, another study (17) reported the attenuation of splanchnic sympathetic nerve activity after brief stimulation of the tibial nerve during 5% CO2, thus demonstrating a decrease in the magnitude of a somatosympathetic reflex response in hypercapnic rats. Finally, it has been suggested that hypercapnia activates central chemoreceptors in the respiratory network, pre-Bötzinger or cVLM, to decrease sympathetic activity, likely by activating barosensitive neurons in this region (20). Our data are consistent with investigations (17, 20) showing that hypercapnia reduces sympathetic outflow. Furthermore, we have documented that elevated Pco2 decreases cardiovascular responses in a concentration-dependent manner through mechanisms that involve medullary nuclei that process information received from both spinal and nonspinal (vagal) afferent input. The nuclei influence, in turn, both sympathetic and parasympathetic outflow (see below). In combination with our previous studies (5, 12) showing sympathoexcitatory responses in eucapnic rats during gastric distension, it is apparent that hypercapnia and acidosis play a role in reversing the sympathoexcitation.

The inhibitory cardiovascular responses observed with hypercapnia and acidosis were related to the activation of both sympathetic and parasympathetic afferent pathways since local anesthetic blockade of either spinal or vagal afferent pathways markedly reduced the cardioinhibitory response to gastric distension. The fact that both sets of afferents are involved in this reflex is interesting as previous studies (12, 15, 22) have shown that the sympathoexcitatory reflex from gastric distension and from visceral organs, in general, is carried predominately by the splanchnic nerve, a spinal pathway. Few studies have examined vagal input during abdominal visceral organ stimulation and have focused only on the heart rate response (bradycardia). In this regard, a study by Tougas and Wang (37) examined the cholinergic efferent activation during gastric distension that led to a decrease in heart rate. They did not examine blood pressure responses nor did they determine if there was a relationship to Pco2 or pH or a reversal from a pressor response to a depressor response. In fact, the study did not report acid-base status, so it is uncertain if their animals were hypercapnic or acidotic. Thus, the present study is the first to demonstrate that, in the setting of hypercapnia and acidosis, gastric distension causes inhibitory reflex responses that use both vagal and sympathetic (spinal) afferent pathways. Furthermore, this is the first observation that reflex responses to gastric mechanical stimulation are processed in regions of the brain stem regulating both sympathetic and parasympathetic outflow and that the magnitude of the cardiovascular response in this condition depends on the extent of elevation in Pco2 and depression of pH.

Central processing of the gastric inhibitory cardiovascular response occurred in several medullary nuclei that modulate sympathetic or parasympathetic outflow. We chose to study brain stem nuclei that directly regulate autonomic sympathetic and parasympathetic outflow. Specifically, we examined the nucleus ambiguus as this nucleus processes afferent information leading to the cardiac chronotropic responses. On the other hand, the cVLM contributed to the decrease in blood pressure, whereas the rVLM processed both hemodynamic responses. Gabazine blockade of GABAA receptors confirmed the depolarization blockade experiments in the rVLM and identified a role for this inhibitory neurotransmitter. Since the cVLM also participates in the depressor reflex, it is possible that cVLM-rVLM GABAergic projections play a role since a number of studies (28, 29, 32, 38) have demonstrated their role in sympathoinhibition during baroreflex activation, among others.

Our previous data showed that spinal afferents in normocapnic animals mediate the gastric distention-induced pressor responses. Although sympathetic afferents played a predominant role in the previous sympathoexcitatory studies, activation of vagal afferents cannot be excluded. The present data collected in hypercapnic animals showed that both spinal and vagal afferent fibers participate in reflex cardiovascular inhibition during mechanical stimulation of the stomach wall. However, it is likely that hypercapnia-induced activation of central chemoreceptors in the present study participated in the reflex response by altering central processing, for example, through the cVLM, rVLM, and nucleus ambiguus, leading to sympathoinhibition and parasympathetic activation.

As noted, the gastric distention-induced cardiovascular inhibitory responses include both sympathoinhibition and parasympathoexcitation. Peripheral muscarinic cholinergic blockade with atropine methyl bromide increased the basal heart rate and reduced the heart rate inhibition. The small increase in basal heart rate likely did not influence reversal of the negative chronotropic response since the animals remained responsive, as demonstrated by the reflex decrease in blood pressure. Similarly, peripheral β-adrenergic blockade partially reversed the reflex bradycardia, documenting that β-adrenoceptors and sympathetic withdrawal presumably originating from the rVLM also participate in the chronotropic response. The small increase in baseline blood pressure likely did not influence the heart rate response to atenolol. Blockade of α-adrenoceptors, on the other hand, reversed inhibitory blood pressure responses, further supporting the notion of sympathetic withdrawal during the gastric distension reflex in the setting of hypercapnia and acidosis.

Perspective

Rats anesthetized with ketamine-xylazine under the condition of hypercapnia that were subjected to gastric distention demonstrated reproducible depressor and bradycardia responses in the present study. These reflex responses are in contrast to our previous studies (5, 15) involving ketamine and α-chloralose anesthesia, which documented pressor responses in eucapnic cats and rats during gastric distention. However, in the present study, we demonstrated that the cardioinhibitory blood pressure responses were not dependent on the anesthetic. Overall, reflex depressor and cardioinhibitory responses to gastric distension in response to hypercapnia-acidosis do not appear to be influenced by the choice of anesthetic. Furthermore, directional changes in reflex cardiovascular responses to visceral afferent stimulation, particularly gastric distension, are dictated by the baseline arterial Pco2 and pH. Since elevations in CO2 and attendant decreases in pH can convert a sympathoexcitatory response to a sympathoinhibitory response, investigators need to carefully evaluate and control the blood gas status of their preparations during studies involving reflex activation, as supported by Sheriff et al. (30) using a hypoxic model. Furthermore, during gastrointestinal surgery, which can evoke visceral afferent stimulation, there is a risk of hypotensive as well as hypertensive responses depending on the underlying acid-base status, either of which could place patients at risk for an adverse event.

Conclusions

The present study shows that gastric distention in the setting of high CO2 and acidosis leads to reflex decreases blood pressure and heart rate, responses mediated by both spinal and vagal afferent input into central nervous system. These reflexes are processed in the rVLM, cVLM, and nucleus ambiguus. Activation of the cVLM during mechanical stimulation of the stomach likely influences the rVLM through a GABAergic mechanism that, in turn, leads to sympathoinhibitory reflex responses. Unlike the cVLM, the rVLM modulates both depressor and negative chronotropic reflex responses through the withdrawal of sympathetic outflow. Ultimately, descending parasympathetic and sympathetic efferent projections to the heart and vascular system through cholinergic and adrenergic mechanisms lead to bradycardia and depressor responses associated with the stimulation of gastric mechanosensitive receptors. This model is the first example of a reflex response that is changed directionally and modulated by the extent of hypercapnic-acidosis.

GRANTS

The work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants HL-63313 and HL-72125 as well as by the Larry K. Dodge and Susan Samueli Endowed Chairs (to J. C. Longhurst).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful for the technical input of Wei Zhou and Jesse Ho.

REFERENCES

- 1. Abdelrahman A, Tabrizchi R, Pang CC. Effects of β1- and β2-adrenergic stimulation on hemodynamics in the anesthetized rat. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 15: 720–728, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Baird J, Travers J, Travers S. Parametric analysis of gastric distention responses in the parabrachial nucleus. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 281: R1568–R1580, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bernards J, Dejours P, Lacaisse A. Ventilatory effects in man of breathing successively CO2-free, CO2-enriched and CO2-free gas mixtures with low, normal or high oxygen concentration. Respir Physiol 1: 390–397, 1966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cherniack N, Edelman N, Lahiri S. Hypoxia and hypercapnia as respiratory stimulants and depressants. Respir Physiol 11: 113–126, 1970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Crisostomo M, Li P, Tjen-A-Looi SC, Longhurst JC. Nociceptin in rVLM mediates electroacupuncture inhibition of cardiovascular reflex excitatory response in rats. J Appl Physiol 98: 2056–2063, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Davison JS, Grundy D. Modulation of single vagal efferent fibre discharge by gastrointestinal afferents in the rat. J Physiol 284: 82, 1978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hanna B, Lioy F, Polosa C. Role of carotid and central chemoreceptors in the CO2 response of sympathetic preganglionic neurons. J Auton Nerv Syst 3: 421–435, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hsiao AF, Tjen-A-Looi S, Zhou W, Li P, Cabatbat R, Longhurst JC. Neural pathways of cardiovascular depressor reflex during gastric distension and its modulation by electroacupuncture. FASEB J 22: 737.23, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kara T, Narkiewicz K, Somers V. Chemoreflexes–physiology and clinical implications. Acta Physiol Scand 177: 377–384, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Knuepfer MM, Gan Q. Role of cholinergic receptors and cholinesterase activity in hemodynamic responses to cocaine in conscious rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 276: R103–R112, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lahiri S, Delaney RG. Relationship between carotid chemoreceptor activity and ventilation in the cat. Respir Physiol 24: 267–286, 1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Li P, Rowshan K, Crisostomo M, Tjen-A-Looi S, Longhurst J. Effect of electroacupuncture on pressor reflex during gastric distention. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 283: R1335–R1345, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Li P, Tjen-A-Looi SC, Longhurst JC. The arcuate-ventrolateral periaqueductal gray reciprocal circuit in electroacupuncture cardiovascular inhibition. Auton Neurosci 158: 13–23, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Li P, Tjen-A-Looi S, Longhurst JC. Excitatory projections from arcuate nucleus to ventrolateral periaqueductal gray in electroacupuncture inhibition of cardiovascular reflexes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 290: H2535–H2542, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Longhurst JC, Ibarra J. Sympathoadrenal mechanisms in hemodynamic responses to gastric distention in cats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 243: H748–H753, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Longhurst J, Spilker H, Ordway G. Cardiovascular reflexes elicited by passive gastric distension in anesthetized cats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 240: H539–H545, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Makeham J, Goodchild A, Costin N, Pilowsky P. Hypercapnia selectively attenuates the somato-sympathetic reflex. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 140: 133–143, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McCoy K, Rotto D, Rybicki K, Kaufman M. Attenuation of the reflex pressor response to muscular contraction by an antagonist to somatostatin. Circ Res 62: 18–24, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Moazzami A, Tjen-A-Looi SC, Longhurst JC. Serotonergic projection from nucleus raphe pallidus to rostral ventrolateral medulla modulates cardiovascular reflex responses during acupuncture. J Appl Physiol 108: 1336–1346, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Moreira TS, Takakura AC, Colombari E, Guyenet PG. Central chemoreceptors and sympathetic vasomotor outflow. J Physiol 577: 369–386, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. O'Regan R, Majcherczyk S. Role of peripheral chemoreceptors and central chemosensitivity in the regulation of respiration and circulation. J Exp Biol 100: 23–40, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pan HL, Zeisse ZB, Longhurst J. Role of summation of afferent input in cardiovascular reflexes from splanchnic nerve stimulation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 270: H849–H856, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. New York: Academic, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Petho G, Porszasz R, Peitl B, Szolcsanyi J. Spike generation from dorsal roots and cutaneous afferents by hypoxia or hypercapnia in the rat in vivo. Exp Physiol 84: 1–15, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pitsikoulis C, Bartels M, Gates G, Rebmann R, Layton A, De Meersman R. Sympathetic drive is modulated by central chemoreceptor activation. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 164: 373–379, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pozo F, Fueyo A, Esteban MM, Rojo-Ortega JM, Marin B. Blood pressure changes after gastric mechanical and electrical stimulation in rats. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 249: G739–G744, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Qin C, Chandler MJ, Miller K, Foreman R. Responses and afferent pathways of C1-C2 spinal neurons to gastric distention in rats. Auton Neurosci 104: 128–136, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schreihofer AM, Ito S, Sved AF. Brain stem control of areterial pressure in chronic arterial baroreceptor-denervated rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 289: R1746–R1755, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schreihofer A, Guyenet P. The baroreflex and beyond: control of sympathetic vasomotor tone by gabaergic neurons in the ventrolateral medulla. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 29: 514–521, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sheriff M, Fontes M, Killinger S, Horiuchi J, Dampney RAL. Blockade of AT1 receptors in the rostral ventrolateral medulla increases sympathetic activity under hypoxic conditions. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 290: R733–R740, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Steinback C, Salzer D, Medeiros P, Kowalchuk M, Shoemaker J. Hypercapnic vs. hypoxic control of cardiovascular, cardiovagal, and sympathetic function. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 296: R402–R410, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sved AF, Ito S, Madden CJ. Baroreflex dependent and independent roles of the caudal ventrolateral medulla in cardiovascular regulation. Brain Res Bulletin 51: 129–133, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Takakura A, Colombari E, Menani J, Moreira TS. Ventrolateral medulla mechanims involved in cardiorespiratory responses to central chemoreceptor activation in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. First published November 10, 2010; doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00220.2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Timmermans P, Lam E, Van Zwieten P. The interaction between prazosin and clonidine at α-adrenoceptors in rats nad cata. Eur J Pharmacol 55: 57–66, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tjen-A-Looi SC, Li P, Longhurst JC. Medullary substrate and differential cardiovascular response during stimulation of specific acupoints. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 287: R852–R862, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tjen-A-Looi S, Li P, Longhurst C. Processing cardiovascular information in the vlPAG during electroacupuncture in rats: roles of endocannabinoids and GABA. J Appl Physiol 1793–1799, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tougas G, Wang L. Pseudoaffective cardioautonomic responses to gastric distention in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 277: R272–R278, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Willette R, Punnen S, Krieger A, Sapru H. Interdependence of rostral and caudal ventrolateral medullary areas in the control of blood pressure. Brain Res 321: 169–174, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhou W, Mahajan A, Longhurst JC. Spinal nociceptin mediates electroacupuncture-related modulation of visceral sympathoexcitatory reflex responses in rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 297: H859–H865, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]