Abstract

Whole brain radiation therapy (WBRT) leads to cognitive impairment in 40–50% of brain tumor survivors following treatment. Although the etiology of cognitive deficits post-WBRT remains unclear, vascular rarefaction appears to be an important component of these impairments. In this study, we assessed the effects of WBRT on the cerebrovasculature and the effects of systemic hypoxia as a potential mechanism to reverse the microvascular rarefaction. Transgenic mice expressing green fluorescent protein driven by the Acta2 (smooth muscle actin) promoter for blood vessel visualization were randomly assigned to control or radiated groups. Animals received a clinical series of 4.5 Gy WBRT two times weekly for 4 wk followed by 1 mo of recovery. Subsequently, mice were subjected to 11% (hypoxia) or 21% (normoxia) oxygen for 1 mo. Capillary density in subregions of the hippocampus revealed profound vascular rarefaction that persisted despite local tissue hypoxia. Nevertheless, systemic hypoxia was capable of completely restoring cerebrovascular density. Thus hippocampal microvascular rarefaction post-WBRT is not capable of stimulating angiogenesis and can be reversed by chronic systemic hypoxia. Our results indicate a potential shift in sensitivity to angiogenic stimuli and/or the existence of an independent pathway of regulating cerebral microvasculature.

Keywords: angiogenesis, hippocampus, capillary, pericyte

in the united states, over 1,500,000 new cases of cancer are expected to be diagnosed this year, with over 22,000 cases expected to be brain and nervous system related (2). Whole brain radiation therapy (WBRT) continues to be one of the most common forms of treatment for metastatic brain tumors located in brain regions that are difficult to reach for surgical removal, as well as for treatment of primary brain tumors following surgical intervention (26). Although this treatment regimen has proven to be effective in reducing or eliminating tumors, some damage to normal brain tissue is inevitable. Previous studies have shown that a relatively large proportion of brain tumor survivors develop cognitive deficits that are evident months to years after treatment (26, 29, 52, 53). These impairments in learning and memory have been confirmed in animal models (6, 46). However, the etiology of WBRT-induced cognitive impairment is not fully understood.

In animal studies, radiation therapy has been shown to induce dose-dependent endothelial apoptosis (30) and disruption of the blood-brain barrier (31), thickening and vacuolation of the vascular basement membrane (25), vascular rarefaction (7), and cognitive deficits (6, 46). To sustain neuronal activity and normal brain function, blood vessel integrity must be preserved to maintain a consistent supply of oxygen, nutrients, and growth factors and provide efficient removal of waste products from cells. Thus it is reasonable to conclude that radiation-induced damage to the cerebral microvasculature contributes at least in part to the impairment in brain function.

The aim of this study was to determine whether the administration of a clinically relevant regimen of WBRT results in microvascular rarefaction within subregions of the hippocampus (an area important for learning and memory) and whether low ambient oxygen levels, a potent physiological stimulus for vessel growth throughout the body, could restore microvascular density following treatment. We report that, by 2 mo post-WBRT, microvascular rarefaction in regions of the hippocampus is readily apparent; however, when mice are challenged with chronic hypoxia (11% oxygen for 28 days), microvascular density was completely restored. This is the first study, to our knowledge, that demonstrates complete recovery of cerebral microvascular density following WBRT and provides evidence that local angiogenic pathways are inhibited or completely suppressed by radiation whereas other pathways are maintained.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

To enable the direct visualization of blood vessels, a transgenic mouse model utilizing the Acta2 promoter to direct the expression of green fluorescent protein (GFP) was used. These mice were generated by Dr. J. Y. Tsai (47). The design of the Acta2 promoter was described by Wang et al. (51). Homozygous pairs of smooth muscle α-actin (SMA)-GFP mice, a generous gift from Dr. James Tomasek [University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center (OUHSC), Oklahoma City, OK], were bred, and male offspring were housed 3–5/cage in the rodent barrier facility at OUHSC. Animals were maintained on a 12:12-h light-dark cycle and fed standard rodent chow and water ad libitum. At 10–11 wk of age and 1 wk before radiation treatment, mice were transferred to the conventional facility (OUHSC) and housed under similar conditions. All animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of OUHSC.

Irradiation and experimental design.

After acclimating to the conventional facility for 1 wk, mice were randomly assigned to either control or radiated groups. Animals were weighed and anesthetized via intraperitoneal injection of ketamine and xylazine (100/15 mg/kg). Mice in the radiated group received a fractionated series of WBRT administered as eight fractions of 4.5 Gy/fraction, two times a week for 4 wk (total cumulative dose of 36 Gy), at a rate of 1.23 Gy/min while sham animals were anesthetized without radiation. Radiation was administered using a 137-cesium gamma irradiator (GammaCell 40; Nordion International). A Cerrobend shield was used to minimize the dose to the bodies of mice in the radiated group.

Dosimetry.

The radiation dose received by the mice was verified using film dosimetry. Radiochromic films were placed within a rodent equivalent phantom between the Cerrobend molds in specific locations. Six film positions were used to measure representations of the anterior and posterior surfaces as well as the centers of the head and body of the mice. The irradiator was then activated for a time known to deliver 4.5 Gy to an empty irradiator chamber. Because the irradiation chamber now contained both rodent and Cerrobend shielding, the actual dose was expected to be different from that delivered to an empty cell. Film analysis indicated that the body of the mice received an average of 1.06 ± 0.05 Gy while the head received 4.4 ± 0.2 Gy.

Hypoxia treatment.

One month following sham or WBRT, mice were further divided into normoxic (21% oxygen) or hypoxic (11% oxygen) conditions. Hypoxia was achieved through the use of a custom-designed Plexiglas chamber (40.5 in. × 24 in. × 10.5 in.) capable of holding six mouse cages. Air flow through the chamber was provided by air pumps and holes drilled into the individual mouse cages. Nitrogen gas and room air were regulated to create a final ambient oxygen level of 11% inside the chamber. Oxygen levels were monitored at least twice daily using an oxygen meter (Extech Instruments, Waltham, MA) inserted through a fitted port. Adjustments to gas flow were made as necessary. Hypoxia was induced gradually by decreasing the levels of oxygen by 1.5% daily for the first 7 days, until the target level of 11% oxygen was obtained. Oxygen levels were then maintained at 11% from day 7 through day 28. Cage changes were performed weekly, exposing animals to room air for short periods (no more than 5 min). Animals in the normoxic group were housed in similar cages as hypoxic animals with oxygen levels maintained at 21%.

Tissue collection and preparation.

After completion of hypoxia treatment, mice were anesthetized using ketamine and xylazine (100/15 mg/kg). Animals in the hypoxic groups were exposed to room air for no more than 1 h before death to minimize changes that may occur with reoxygenation. Blood was collected via cardiac puncture for determining hematocrit levels. Animals were transcardially perfused using cold, heparinized sodium phosphate buffer. Brains were removed; left hemispheres were postfixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight; and right hemispheres were dissected into hippocampus and cortex, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until processing.

Vascular endothelial growth factor measurement.

Protein was isolated from the right hippocampus using a Protein and RNA Isolation System kit (PARIS; Ambion, Austin, TX) following the manufacturer's protocol. Protein concentration was measured using the BCA Protein Assay kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) protein levels were quantified using the Mouse VEGF ELISA Quantikine kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) following the manufacturer's protocol. Protein expression of VEGF within the hippocampus was represented as picograms per milligram of total protein. Percent change in hematocrit and VEGF protein expression was calculated using the following equation %change = [(Hyp − Norm)/Norm] × 100, where “Hyp” represents the average value of the hypoxic group and “Norm” represents the average value of the normoxic group.

Western blot analysis of VEGF-R2 and hypoxia-inducible factor-1α.

For Western blot analysis, equal amounts of protein were loaded in 4–20% gradient gels (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes using semidry transfer. After being blocked for 1 h in Odyssey Blocking Solution (Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE), membranes were incubated in 1:500 rabbit polyclonal antibody to VEGF-R2 and rabbit polyclonal antibody to β-tubulin (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) at room temperature for 1 h. Membranes were then incubated with 1:10,000 goat anti-rabbit AlexorFluor 680 secondary antibody at room temperature for 1 h. Membranes were scanned using an Odyssey system (Li-Cor), and bands were analyzed using Odyssey Analysis software. Protein expression levels were represented as a ratio of VEGF-R2 to tubulin.

Right cortexes were processed using a nuclear extraction kit (Panomics, Fremont, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Protein concentration was measured using the DC Protein Assay (Bio-Rad). Equal amounts of protein from the nuclear extracts were loaded and electrophoresed in 4–20% gradient gels. Membranes were probed using 1:500 rabbit polyclonal antibody to hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α (Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO) followed by 1:10,000 goat anti-rabbit 680 antibody. Membranes were then stripped using Nitro Stripping Buffer (Li-Cor) and probed using 1:2,000 rabbit polyclonal antibody to β-tubulin followed by 1:10,000 goat anti-rabbit 680 antibody and scanned using the Odyssey system. Protein expression was represented as target band intensity/tubulin band intensity.

Quantification of capillary density.

Postfixed left hemispheres were cryoprotected in a series of graded sucrose solutions (10, 20, and 30%) and frozen in Cryo-Gel (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) for sectioning. Coronal sections of 70 μm were cut through the hippocampus and stored free-floating in cryoprotectant solution (25% glycerol, 25% ethylene glycol, 25% 0.1 M phosphate buffer, and 25% water) at −20°C. Sections selected for vessel density analysis were standardized using common anatomical planes following the Comparative Cytoarchitectonic Atlas of the C57BL/6 and 129/Sv Mouse Brains (20). Selected sections were ∼2.7 mm caudal to bregma where the lateral ventricles were least visible. After being blocked in 5% BSA/Tris-buffered saline (TBS) for 1 h, sections were immunostained using antibody against mouse CD31 (1:100, phycoerythrin conjugated; BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA) overnight at 4°C. Sections were washed for 5 min in TBS (×3), transferred to slides, and covered with a cover slip. Image stacks were captured using confocal microscopy (Leica Microsystems, Urbana, IL) using a ×40 oil objective.

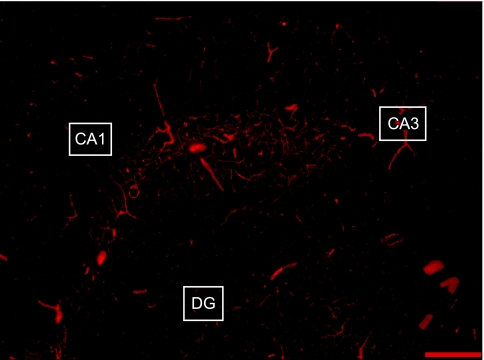

Capillary density in the CA1, CA3, and dentate gyrus (DG) of the hippocampus (shown in Fig. 1) was quantified as the length of blood vessels <10 μm in diameter per volume of tissue using Neurolucida with AutoNeuron (MicroBrightField, Williston, VT). The computer software allows for the tracing of blood vessels in three-dimensional space through acquired image stacks. The total length of capillaries (mm) within a 512 × 512 pixel image was divided by the volume of hippocampal tissue (mm3) to obtain capillary density (length/volume of tissue). The density of SMA- and CD31-stained capillaries was calculated within each region for each animal. The area of the hippocampus within the sampling section was obtained by drawing an outline around the hippocampus and using Neurolucida Explorer to calculate the area. The experimenter was blinded to the groups and treatments of the animals throughout the period of blood vessel staining and analysis.

Fig. 1.

Representative image used for capillary density quantification in regions of the hippocampus. Image was captured at ×4 magnification using fluorescence microscopy. Sections were stained using CD31 antibody for visualization of blood vessels. DG, dentate gyrus. Scale bar = 200 μm.

Quantification of capillary coverage by pericytes.

Pericytes were characterized as cells that were positive for SMA with a round nucleus and long, cytoplasmic projections (14, 15). To confirm that SMA+ cells on capillaries were indeed pericytes, we processed tissue sections for immunohistochemical staining using 1:200 rabbit polyclonal to neuron/glia-type 2 antigen (NG2; Chemicon/Millipore, Billerica, MA) and 1:200 rat anti-mouse platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR)-β (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) antibodies. Sections were incubated in primary antibody for 42 h, washed 6 × 15 min in 1× TBS (1% Triton X-100), incubated for 3 h in 1:200 donkey anti-rabbit DyLight 549 (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) or goat anti-rat TRITC (Abcam), washed, and mounted to slides. Images were captured using a confocal microscope at ×100 magnification. Capillaries covered by pericytes were identified as SMA-positive vessels that were 10 μm or less in diameter. To obtain the percent density of pericyte coverage, the total length of SMA+ capillaries was divided by the total length of CD31+ capillaries of each animal and then multiplied by 100.

Statistical analysis.

Changes in capillary density, hematocrit, VEGF, VEGF-receptor (R) 2, and HIF-1α protein expression were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA (group × treatment). For post hoc analysis, the Student-Newman-Keuls test was used to determine differences between groups. Data are represented as means ± SE with a statistically significant difference set at P < 0.05. All statistical analyses were done using SigmaStat software version 3.5.

RESULTS

General.

Changes in body mass were monitored for the duration of the study. No differences in body mass were evident before radiation (control 27.4 ± 0.5 g, radiated 27.7 ± 0.4 g); however, as expected, midway through and following completion of the WBRT series, animals in the radiated group experienced significant weight loss (P < 0.01) (Table 1). During the 1-mo recovery period, animals in the radiated group demonstrated recovery of body mass but remained significantly lower than the controls (P < 0.01). The radiated animals continued to regain weight until the end of the study when no difference in body mass compared with their control treatment-matched groups (P > 0.05) was observed.

Table 1.

Changes in body mass of animals

| Time Point | Control | Radiated | Significance (P value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 27.4 ± 0.5 (29) | 27.7 ± 0.4 (16) | NS (0.590) |

| 18 Gy | 28.7 ± 0.5 (29) | 25.7 ± 1.2 (16) | (0.008)** |

| 36 Gy | 29.0 ± 0.5 (29) | 25.3 ± 1.0 (16) | (<0.001)*** |

| 1 mo post-WBRT | 29.3 ± 0.5 (29) | 26.2 ± 1.3 (16) | (0.006)** |

| End of study | |||

| Normoxia | 30.0 ± 0.7 (13) | 28.3 ± 1.0 (8) | NS (0.157) |

| Hypoxia | 28.6 ± 0.6 (16) | 27.1 ± 0.4 (8) | NS (0.133) |

Data represent means ± SE; for control and radiated groups, no. of animals is in parentheses. Animals were selected for body mass measurement at each major step of the experiment. Time points shown represent: before commencement of whole brain radiation therapy (WBRT) (baseline), after a cumulative dose of 18 Gy, after completion of the cumulative series of irradiation (36 Gy), 1 mo post-WBRT, and at the end of the hypoxia or normoxia treatment. NS, not significant.

P < 0.01 and

P < 0.001.

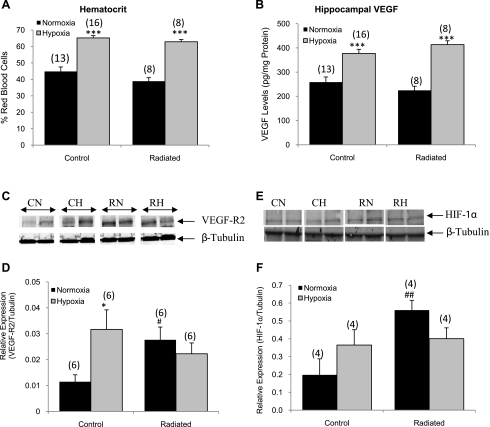

Hematocrit, VEGF, VEGF-R2, and HIF-1α protein levels confirm the hypoxic state of animals.

At the end of the hypoxic study, hematocrit was measured to verify that animals demonstrated normal physiological responses to hypoxia. Hematocrit was slightly reduced in the radiated normoxic group (38.9 ± 2.12) compared with the control normoxic (44.79 ± 2.77), but this difference did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.06; Fig. 2A). Following hypoxia (11% O2 for 28 days), both radiated and control groups had elevated hematocrit values (65.19 ± 1.41 in the controls and 62.84 ± 1.36 in the radiated groups), representing a 31.3 and 38.1% increase, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Confirmation of hypoxic status of animals. Hematocrit (A) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF, B) protein levels increased in response to hypoxia treatment in both groups (n = 8–16 animals/group). C: representative Western blot for VEGF receptor (R) 2 levels. D: quantification of Western blot analysis showed that VEGF-R2 protein levels increased in the control animals in response to hypoxia and also increased in response to radiation (n = 6/group). E: representative Western blot for cortical hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α in nuclear fractions. F: quantification of the Western blot showed that, in the normoxic-treated radiated group, nuclear HIF-1α is increased compared with controls (n = 4/group). CN, control normoxia; CH, control hypoxia; RN, radiated normoxia; RH, radiated hypoxia. *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.001 vs. the normoxic group. #P < 0.05 and ##P < 0.01 vs. the control normoxic group.

The right hippocampus was processed for VEGF protein expression by ELISA. Following WBRT, there was no change in VEGF expression (258.65 ± 21.2 pg/mg protein in controls and 224.86 ± 16.9 pg/mg protein in the radiated group; Fig. 2B) under normoxic conditions. However, in response to chronic hypoxia, VEGF levels were significantly increased in the hippocampal tissue of both groups (377.03 ± 17.3 pg/mg protein in controls and 413.52 ± 15.9 pg/mg protein in the radiated group, P < 0.001), representing a 31.4 and 45.6% increase, respectively.

VEGF-R2 has been reported to be upregulated in hypoxic conditions (50). Therefore, to confirm the hypoxic state of the tissues, we used Western blotting to determine the relative protein expression of VEGF-R2 in the hippocampus. WBRT induced a 2.3-fold increase in the relative expression of VEGF-R2 (P = 0.038 compared with controls; Fig. 2C). Chronic hypoxia stimulated a 2.7-fold increase in receptor expression in the controls (P = 0.012 compared with the control normoxic group). An increased expression of VEGF-R2 in response to WBRT alone is consistent with the hypothesis that the reduction in vessel density (see below) produced a hypoxic condition within the hippocampus of WBRT-treated animals.

It is well established that the transcription factor, HIF-1α, is stabilized in low oxygen levels (24) and is therefore an excellent hypoxic marker. To determine the level of tissue hypoxia present following WBRT and chronic hypoxia treatment, HIF-1α protein levels were measured in the cortical nuclear fractions using Western blot analysis. Under normoxic conditions, WBRT induced a 2.8-fold increase in nuclear HIF-1α compared with control animals (P = 0.009; Fig. 2F), further supporting the conclusion that the brains of radiated animals were hypoxic.

Microvascular rarefaction in hippocampal subregions and recovery of vascular density following hypoxia.

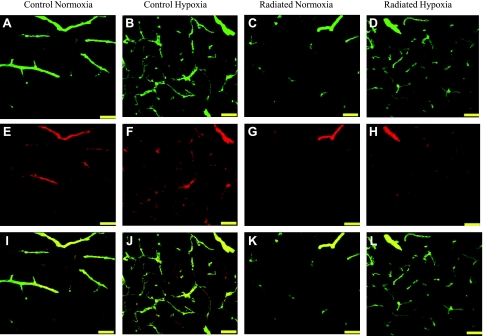

Capillaries were identified by their expression of CD31, using a lumen diameter of 10 μm or less as a standard identifier (40, 55). Capillary density was quantified in CA1, CA3, and DG of the mouse hippocampus and was represented as the total length of capillaries (mm) per volume of tissue sampled (mm3). Figure 3 shows a representative image of SMA+ (Fig. 3, A–D) and CD31 (Fig. 3, E–H) and merged (Fig. 3, I–L) staining of blood vessels in the CA3 region of the hippocampus. Following WBRT, CD31-stained capillary density decreased in the radiated group compared with controls in CA1 (347.97 ± 96.5 vs. 728.21 ± 53.7, P = 0.002; Fig. 4A), CA3 (291.57 ± 85.4 vs. 593.65 ± 75.3, P = 0.01; Fig. 4B), and DG (331.74 ± 81.1 vs. 873.17 ± 79.6, P = 0.003; Fig. 4C). Chronic hypoxia was able to completely restore capillary density in the radiated groups within all regions assessed (P < 0.01 each) to levels found in nonradiated hypoxic animals.

Fig. 3.

Representative images of CD31 and smooth muscle actin (SMA) staining in blood vessels within the hippocampus. Projection image showing SMA (A–D), CD31 (E–H), and merged staining of vessels within CA3 of the hippocampus (I–L) (scale bar = 50 μm). Images were captured using confocal microscopy at ×40 magnification. Analysis revealed reduced CD31 and SMA capillary density in subregions of the hippocampus in response to radiation and complete recovery of CD31 and SMA density in response to hypoxia treatment.

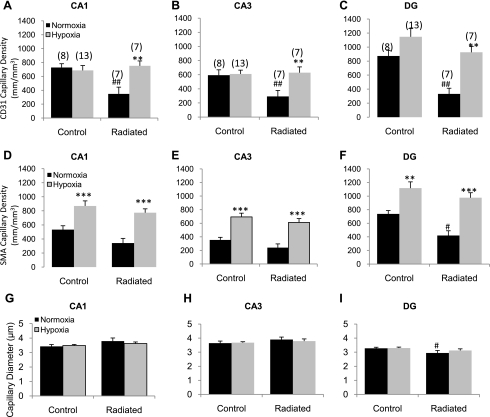

Fig. 4.

Changes in capillary density within subregions of the hippocampus. Sections were stained using CD31 antibody and imaged using confocal microscopy. Capillaries were defined as blood vessels <10 μm in diameter. Capillaries were traced using Neurolucida and quantified as length of vessel per volume of tissue (as described in materials and methods). CD31 capillary density in CA1 (A), CA3 (B), and DG (C). SMA capillary density in CA1 (D), CA3 (E), and DG (F). Capillary diameter in CA1 (G), CA3 (H), and DG (I). Data indicate profound capillary rarefaction in all regions assessed in response to WBRT and complete recovery of density with hypoxia. Data represent means ± SE. **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 vs. the normoxic group and #P < 0.05 and ##P < 0.01 vs. control-normoxic; the number of animals per group is indicated in parentheses.

Capillaries expressing SMA were quantified in the CA1, CA3, and DG of the mouse hippocampus. Following WBRT, SMA capillary density in the CA1 (Fig. 4D) and CA3 (Fig. 4E) did not show a significant reduction (P > 0.05) compared with the control normoxic groups. However, in response to hypoxia treatment, SMA capillary density was significantly increased in both the control and radiated groups (P < 0.01). In the DG (Fig. 4F), WBRT induced a significant reduction in capillary density in the normoxia-treated radiated group (738.15 ± 49.0 to 418.94 ± 70.7, P = 0.01). In response to hypoxia, SMA capillary density increased in both groups (P < 0.01). Analysis of capillary diameter showed no difference between groups or treatments in CA1 (Fig. 4G) and CA3 (Fig. 4H); however, capillary lumen diameter was reduced in the normoxic, WBRT group compared with the control normoxic group (P = 0.044) in the DG (Fig. 4I).

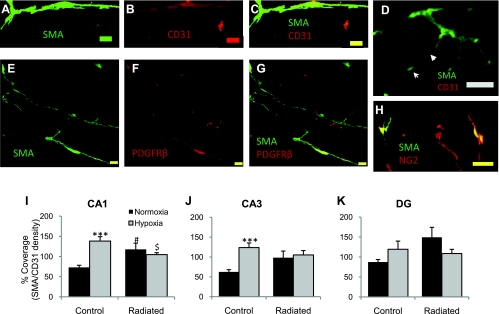

Capillary coverage by pericytes in the mouse hippocampus.

Although there is no definitive immunohistochemical marker for pericytes (14, 15), pericytes were identified by their expression of SMA and general morphology (round nucleus and long cytoplasmic projections as described in Refs. 14 and 15) and confirmed by their expression of NG2 and/or PDGFR-β. SMA+ putative pericytes were observed along CD31-stained endothelial cells of capillaries with the described morphology (Fig. 5, A–D). These cells were also positive for PDGFR-β (Fig. 5, E–G) and NG2 (Fig. 5H). The percent coverage of capillaries by pericytes was quantified by using a ratio of SMA+ capillary length to CD31+ capillary length. In the CA1 region (Fig. 5I), the percent coverage by pericytes increased significantly in response to hypoxia in the controls (from 73.02 ± 5.4 to 138.40 ± 10.9%, P < 0.001) and also increased in both the radiated normoxic (P = 0.012) and hypoxic (P = 0.033) groups compared with the control normoxic group. In the CA3 region (Fig. 5J) of the hippocampus, a significant increase in the percent coverage was observed only in the control hypoxic group (P < 0.001). There were no significant differences between groups or treatments in the DG (Fig. 5K).

Fig. 5.

Coverage of capillaries by pericytes. Sample capillary covered by SMA+ pericyte (A), CD31 staining (B), and merged image captured at ×100 magnification (C). Scale bar represents 10 μm. D: ×20 magnification image showing putative pericytes covering CD31-stained endothelial cells. The general morphology is consistent to that of a pericyte with the centralized nucleus (arrow) and long cytoplasmic projections (arrowhead) covering a capillary. Scale bar represents 20 μm. SMA-positive cells are also positive for platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR)-β (E–G) and neuron/glia-type 2 antigen (NG2, H). Scale bar represents 10 μm. The density of CD31+ capillaries was represented as a percentage of the density of SMA+ capillaries to obtain the percent of coverage. The percent of coverage of capillaries by pericytes in CA1 (I), CA3 (J), and DG (K) are shown. Data represent mean% ± SE. ***P < 0.001 vs. normoxic group, #P < 0.05 vs. control, and $P < 0.05 vs. control normoxic group.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we assessed microvascular changes induced by WBRT and the effect of chronic hypoxia in the mouse hippocampus, a brain region closely associated with learning and memory. WBRT induced profound microvascular rarefaction within 2 mo in CA1, CA3, and DG of the mouse hippocampus. Surprisingly, following 1 mo of hypoxia, a complete recovery of microvascular density was observed in the radiated group, indicating that, although WBRT induced vascular rarefaction and tissue hypoxia (established by HIF-1α and VEGF-R2 levels), other mechanisms capable of inducing vascular regrowth remain intact and can be induced by generalized hypoxia. This is the first study to demonstrate that cerebral microvascular rarefaction occurs in subregions of the hippocampus following WBRT and that a complete recovery of capillary density can be achieved in response to low ambient oxygen levels. Although we cannot exclude the possibility that radiation results in a reduced angiogenic response to localized hypoxia, the present data suggest that more generalized vasculogenic pathways, not affected by WBRT, can be induced by a generalized hypoxic stimulus and restore brain microvasculature.

Radiation and vascular changes.

It is well known that radiation has profound effects on the vasculature. Previous studies have assessed changes in endothelial cells as well as vascular structure and density following several different radiation regimens. For example, one study reported that microvascular rarefaction occurs in the rat brain as early as 10 wk following fractionated WBRT, and a partial recovery is observed at 20 wk (7). Nevertheless, localized changes within hippocampal subregions were not assessed, and significant changes were only observed when larger brain regions were combined for analysis. The present study utilized a mouse model combined with a rigorous analytical approach to assess three-dimensional microvascular changes in subregions of the hippocampus, making it relevant to the cognitive changes induced by radiation treatment. Importantly, significant changes in all regions of the hippocampus were observed within 2 mo of completion of the fractionated doses of radiation. Other studies have utilized single doses of 5–200 Gy to the brain and observed a 15% decrease in endothelial cell number within 1 day of irradiation that was maintained for up to 1 mo (33). Finally, decreased endothelial cell density within the CA1 region of the hippocampus has been reported 12 mo posttreatment after single doses as low as 0.5 and 2 Gy high-linear energy transfer radiation (35). Taken together, these studies demonstrate that endothelial cells are highly sensitive to radiation and are consistent with our findings of a profound capillary rarefaction that occurs within the mouse hippocampus following WBRT.

Significance of capillary density and maintenance of vascular integrity.

As expected, previous studies indicate that capillary density is highly correlated with regional blood flow (16, 56), and our results suggest that the density of the brain microvasculature is one critical factor that contributes to the reduction in blood flow to brain tissues after radiation. The brain is a highly metabolic organ requiring consistent oxygen levels for normal function. Maintaining an adequate supply of oxygen, nutrients, and trophic factors to subregions of the brain is accomplished by highly organized capillary networks that minimize the diffusion distance between the blood vessels and neurons/glia. For example, one study found that regional uptake of loperamide was significantly correlated with local capillary density (56). In addition to the loss of nutrient exchange that undoubtedly occurs from capillary rarefaction, there is a reduced ability to remove the waste products of cellular metabolism (including CO2) from brain tissues. Capillary diameter is also an important indicator of diffusion characteristics, and a large range of diameters has been reported for capillaries. For example, capillary diameters ranging from 3 to 8 μm in the rat cortex (55), 3.2 to 6.9 μm in rabbit tenuissimus muscle (5), and 2.87 μm in reperfused and 4.08 μm in control gerbil brains have been observed (18). In this study, there was no difference in capillary diameters between treatment groups in CA1 or CA3 but a slight, significant decrease in the radiated normoxic group in the DG compared with the control normoxic group. Whether this decrease in capillary diameter is a contributing factor in impaired brain function remains to be established. However, more importantly, we observed a 40% decrease in vessel density, strongly supporting the hypothesis that vascular rarefaction occurring postradiation may have a significant role in the reported decline of cognitive performance (6, 8, 12).

Hypoxia-induced angiogenesis.

Angiogenesis is a multistep process that results in the formation of new blood vessels from a preexisting vascular network (11). Alternatively, vasculogenesis, a process of de novo vessel formation, involves the mobilization of several populations of cells from the bone marrow (1, 9, 22, 28, 54). The processes of angiogenesis and vasculogenesis are recognized as the two primary mechanisms necessary to develop, maintain, and/or restore vascular integrity after disruption of vascular networks (44). Previous results indicate that prevention of glioblastoma recurrence can only be accomplished when vasculogenesis, and not angiogenesis, is inhibited (27), demonstrating that these processes are activated by different stimuli and utilize independent pathways.

Hypoxia is a potent angiogenic stimulus (10, 23), acting through the stabilization of HIF-1α and activation of downstream angiogenic factors such as VEGF and erythropoietin (13, 32, 41). Recent studies have shown that radiation induces tissue hypoxia, HIF-1α expression, and oxidative stress as early as 4 wk posttreatment (42). In this study, we hypothesized that WBRT-induced vascular rarefaction was the result of diminished local angiogenic capacity. In response to WBRT, profound vascular rarefaction occurred in the presence of tissue hypoxia. The absence of significant angiogenesis in the presence of hypoxia indicates that local vascular repair is impaired in radiated animals. However, we also subjected these animals to a low ambient oxygen level of 11% oxygen for 1 mo and then reassessed capillary density. In response to hypoxia, vessel density was completely restored in radiated animals, providing prima facia evidence that a general limitation of vessel growth is not the primary factor in the chronic vessel rarefaction after radiation therapy.

Although the present study was not designed to distinguish between angiogenesis and vasculogenesis in the process of vessel repair, our results are consistent with the hypothesis that radiation suppresses local angiogenesis, whereas vessel density can be reestablished through hypoxia-induced vasculogenesis. Udagawa et al. (48) reported that radiation-induced suppression of angiogenesis is independent of restoration of hematopoietic cells, in that, although hematopoietic reconstitution occurred following radiation, vessel density was not restored but remained lower than the nonradiated controls. The relative contribution of each of these mechanisms to the restoration of microvascular density observed in our study is uncertain. However, the lack of local angiogenesis in the radiated group suggests that the radiation-induced tissue hypoxia alone is not an adequate stimulus to restore vessel density. On the contrary, the introduction of a generalized hypoxic stimulus is necessary to initiate vessel growth. Our data indicate that at least two independent processes contribute to vessel growth. We hypothesize that inhibition or a shift in sensitivity of local angiogenic processes occurs following WBRT, whereas other processes induced by hypoxia (e.g., vasculogenesis) remain intact and are able to compensate for the effects of radiation.

Pericyte outgrowth in the microvasculature.

Pericytes are a heterogeneous population of mural cells associated with the microvasculature (3, 34) having important roles in endothelial proliferation (45), blood-brain barrier integrity (19), contraction of capillaries, and regulation of capillary blood flow (43). Several different markers have been used to identify pericytes, including SMA (19, 21, 36, 37, 39), NG2 (21, 38, 49), desmin (21), endosialin (49), and PDGFR-β (17, 38, 49). In this study, putative pericytes were identified by their morphology and expression of SMA, NG2, and PDGFR-β, as well as their association to blood vessels with a diameter <10 μm. Pericytes have been shown to guide and precede proliferating endothelial cells during embryonic angiogenesis (49) and also function in stabilizing newly formed blood vessels, maintaining the endothelial cells in a quiescent state (32). In tumor vasculature, entire endothelial-free vessel tubes consisting only of pericytes have been observed (38). Importantly, blood vessel coverage by pericytes has been postulated to be key in understanding the nature of the blood vessel. The absence of SMA-positive pericytes covering endothelial cells has been suggested to indicate a “window of plasticity” for remodeling of the microvasculature (4). In addition, assessment of the ratio of pericytes to endothelial cells has been reported to show organ-specific distributions. Finally, the pericyte-to-endothelial cell ratio has been reported to be highest in the central nervous system (34), specifically the retina with a 1:1 ratio (45).

In this study, we found a significant increase in SMA capillary density in response to exposure to low oxygen levels. Also, when CD31 capillary density was expressed as a percentage of SMA capillary density, we found that the control group had <100% coverage under normoxic conditions but increased to >100% in hypoxic conditions. The increase in pericyte coverage with hypoxia treatment supports the conclusion that pericytes have a role in guiding the development of new vessel growth during angiogenesis. However, in the radiated group, 100% coverage of capillaries by SMA was observed under normoxic conditions and did not increase further with hypoxia. These observations suggest that pericyte growth remains intact after radiation and may stabilize blood vessels potentially as a protective mechanism. Although our data related to pericyte coverage are of interest, further research will be required to assess the significance of these findings.

In summary, WBRT results in capillary rarefaction in subregions of the hippocampus, a brain region highly associated with cognitive function. We have demonstrated that microvascular rarefaction post-WBRT induces local tissue hypoxia, but the hypoxic state within the tissue is not adequate to stimulate an angiogenic response. Nevertheless, a generalized stimulus of low ambient oxygen levels completely restores brain microvascular density. Our data suggest that WBRT inhibits angiogenesis through a yet to be determined local mechanism resulting in either a shift in the sensitivity for hypoxia-induced angiogenesis or a permanent impairment in local angiogenesis. Nevertheless, the cerebral vessel rarefaction can be overcome by a generalized hypoxic stimulus.

GRANTS

This study was supported by the following grants: NIH Grants NS-056218 and AG-11370 (W. E. Sonntag), an American Heart Association Predoctoral Fellowship (J. P. Warrington), and an University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center GSA Research Grant (J. P. Warrington).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest are declared by the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. James Tomasek for providing breeding pairs of SMA-GFP mice. The technical support of Matthew Mitschelen, Julie Farley, and Han Yan is greatly appreciated.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ahn G, Brown J. Role of endothelial progenitors and other bone marrow-derived cells in the development of the tumor vasculature. Angiogenesis 12: 159–164, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. American Cancer Society Cancer Facts & Figures 2010. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Armulik A, Abramsson A, Betsholtz C. Endothelial/pericyte interactions. Circ Res 97: 512–523, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Benjamin L, Hemo I, Keshet E. A plasticity window for blood vessel remodelling is defined by pericyte coverage of the preformed endothelial network and is regulated by PDGF-B and VEGF. Development 125: 1591–1598, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bosman J, Tangelder GJ, Oude Egbrink MG, Reneman RS, Slaaf DW. Capillary diameter changes during low perfusion pressure and reactive hyperemia in rabbit skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 269: H1048–H1055, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brown W, Blair R, Moody D, Thore C, Ahmed S, Robbins M, Wheeler K. Capillary loss precedes the cognitive impairment induced by fractionated whole-brain irradiation: a potential rat model of vascular dementia. J Neurol Sci 257: 67–71, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brown W, Thore C, Moody D, Robbins M, Wheeler K. Vascular damage after fractionated whole-brain irradiation in rats. Radiat Res 164: 662–668, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Butler JM, Rapp SR, Shaw EG. Managing the cognitive effects of brain tumor radiation therapy. Curr Treat Options Oncol 7: 517–523, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Caballero S, Sengupta N, Afzal A, Chang K, Li Calzi S, Guberski D, Kern T, Grant M. Ischemic vascular damage can be repaired by healthy, but not diabetic, endothelial progenitor cells. Diabetes 56: 960–967, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cao R, Jensen L, Söll I, Hauptmann G, Cao Y. Hypoxia-induced retinal angiogenesis in zebrafish as a model to study retinopathy. PLoS One 3: e2748, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Conway E, Collen D, Carmeliet P. Molecular mechanisms of blood vessel growth. Cardiovasc Res 49: 507–521, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. DeAngelis LM, Delattre JY, Posner JB. Radiation-induced dementia in patients cured of brain metastases. Neurology 39: 789–796, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Denko N. Hypoxia, HIF1 and glucose metabolism in the solid tumour. Nat Rev Cancer, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dore-Duffy P, Cleary K. Morphology and properties of pericytes. Methods Mol Biol 686: 49–68, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fisher M. Pericyte signaling in the neurovascular unit. Stroke 40: S13–15, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gjedde A, Diemer N. Double-tracer study of the fine regional blood-brain glucose transfer in the rat by computer-assisted autoradiography. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 5: 282–289, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Greenberg J, Shields D, Barillas S, Acevedo L, Murphy E, Huang J, Scheppke L, Stockmann C, Johnson R, Angle N, Cheresh D. A role for VEGF as a negative regulator of pericyte function and vessel maturation. Nature 456: 809–813, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hauck EF, Apostel S, Hoffmann JF, Heimann A, Kempski O. Capillary flow and diameter changes during reperfusion after global cerebral ischemia studied by intravital video microscopy. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 24: 383–391, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hayashi K, Nakao S, Nakaoke R, Nakagawa S, Kitagawa N, Niwa M. Effects of hypoxia on endothelial/pericytic co-culture model of the blood-brain barrier. Regul Pept 123: 77–83, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hof PR, Young WC, Bloom FE, Belichenko PV, Celio MR. Comparative Cytoachitectonic Atlas of the C57BL/6 and 129/Sv Mouse Brains. New York, NY: Elsevier, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hughes S, Chan-Ling T. Characterization of smooth muscle cell and pericyte differentiation in the rat retina in vivo. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 45: 2795–2806, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hunting C, Noort W, Zwaginga J. Circulating endothelial (progenitor) cells reflect the state of the endothelium: vascular injury, repair and neovascularization. Vox Sang 88: 1–9, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ingraham JP, Forbes ME, Riddle DR, Sonntag WE. Aging reduces hypoxia-induced microvascular growth in the rodent hippocampus. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 63: 12–20, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jewell U, Kvietikova I, Scheid A, Bauer C, Wenger R, Gassmann M. Induction of HIF-1alpha in response to hypoxia is instantaneous. FASEB J 15: 1312–1314, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kamiryo T, Lopes M, Kassell N, Steiner L, Lee K. Radiosurgery-induced microvascular alterations precede necrosis of the brain neuropil. Neurosurgery 49: 409–414, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Khuntia D, Brown P, Li J, Mehta M. Whole-brain radiotherapy in the management of brain metastasis. J Clin Oncol 24: 1295–1304, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kioi M, Vogel H, Schultz G, Hoffman R, Harsh G, Brown J. Inhibition of vasculogenesis, but not angiogenesis, prevents the recurrence of glioblastoma after irradiation in mice. J Clin Invest 120: 694–705, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Leone A, Valgimigli M, Giannico M, Zaccone V, Perfetti M, D'Amario D, Rebuzzi A, Crea F. From bone marrow to the arterial wall: the ongoing tale of endothelial progenitor cells. Eur Heart J 30: 890–899, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Li J, Bentzen S, Renschler M, Mehta M. Relationship between neurocognitive function and quality of life after whole-brain radiotherapy in patients with brain metastasis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 71: 64–70, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Li Y, Chen P, Haimovitz-Friedman A, Reilly R, Wong C. Endothelial apoptosis initiates acute blood-brain barrier disruption after ionizing radiation. Cancer Res 63: 5950–5956, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Li Y, Chen P, Jain V, Reilly R, Wong C. Early radiation-induced endothelial cell loss and blood-spinal cord barrier breakdown in the rat spinal cord. Radiat Res 161: 143–152, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Liao D, Johnson R. Hypoxia: a key regulator of angiogenesis in cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev 26: 281–290, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ljubimova N, Levitman M, Plotnikova E, Eidus L. Endothelial cell population dynamics in rat brain after local irradiation. Br J Radiol 64: 934–940, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lu C, Sood AK. Role of pericytes in angiogenesis. In: Cancer Drug Discovery and Development Angiogenic Agents in Cancer Therapy, edited by Teicher BA. Totowa, Canada: Humana, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mao X, Favre C, Fike J, Kubinova L, Anderson E, Campbell-Beachler M, Jones T, Smith A, Rightnar S, Nelson G. High-LET radiation-induced response of microvessels in the Hippocampus. Radiat Res 173: 486–493, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nehls V, Drenckhahn D. Heterogeneity of microvascular pericytes for smooth muscle type alpha-actin. J Cell Biol 113: 147–154, 1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nisancioglu M, Betsholtz C, Genové G. The absence of pericytes does not increase the sensitivity of tumor vasculature to vascular endothelial growth factor-A blockade. Cancer Res 70: 5109–5115, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ozerdem U, Stallcup W. Early contribution of pericytes to angiogenic sprouting and tube formation. Angiogenesis 6: 241–249, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Park F, Mattson D, Roberts L, Cowley AJ. Evidence for the presence of smooth muscle α-actin within pericytes of the renal medulla. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 273: R1742–R1748, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Peppiatt CM, Howarth C, Mobbs P, Attwell D. Bidirectional control of CNS capillary diameter by pericytes. Nature 443: 700–704, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pugh C, Ratcliffe P. Regulation of angiogenesis by hypoxia: role of the HIF system. Nat Med 9: 677–684, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rabbani Z, Mi J, Zhang Y, Delong M, Jackson I, Fleckenstein K, Salahuddin F, Zhang X, Clary B, Anscher M, Vujaskovic Z. Hypoxia inducible factor 1alpha signaling in fractionated radiation-induced lung injury: role of oxidative stress and tissue hypoxia. Radiat Res 173: 165–174, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rucker H, Wynder H, Thomas W. Cellular mechanisms of CNS pericytes. Brain Res Bull 51: 363–369, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Schatteman GC. Non-classical mechanisms of heart repair. Mol Cell Biochem 264: 103–117, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Shepro DN. Morel Pericyte physiology. FASEB J 7: 1031–1038, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Shi L, Adams MM, Long A, Carter CC, Bennett C, Sonntag WE, Nicolle MM, Robbins M, D'Agostino R, Brunso-Bechtold JK. Spatial learning and memory deficits after whole-brain irradiation are associated with changes in NMDA receptor subunits in the hippocampus. Radiat Res 166: 892–899, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tsai JY, Yamamoto T, Fariss R, Hickman F, Pagan-Mercado G. Using SMAA-GFP mice to study pericyte coverage of retinal vessels (Abstract). Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 43: 12, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 48. Udagawa T, Birsner A, Wood M, D'Amato R. Chronic suppression of angiogenesis following radiation exposure is independent of hematopoietic reconstitution. Cancer Res 67: 2040–2045, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Virgintino D, Girolamo F, Errede M, Capobianco C, Robertson D, Stallcup W, Perris R, Roncali L. An intimate interplay between precocious, migrating pericytes and endothelial cells governs human fetal brain angiogenesis. Angiogenesis 10: 35–45, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Waltenberger J, Mayr U, Pentz S, Hombach V. Functional upregulation of the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor KDR by hypoxia. Circulation 94: 1647–1654, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wang J, Niu W, Nikiforov Y, Naito S, Chernausek S, Witte D, LeRoith D, Strauch A, Fagin J. Targeted overexpression of IGF-I evokes distinct patterns of organ remodeling in smooth muscle cell tissue beds of transgenic mice. J Clin Invest 100: 1425–1439, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Welzel G, Fleckenstein K, Mai S, Hermann B, Kraus-Tiefenbacher U, Wenz F. Acute neurocognitive impairment during cranial radiation therapy in patients with intracranial tumors. Strahlenther Onkol 184: 647–654, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Welzel G, Fleckenstein K, Schaefer J, Hermann B, Kraus-Tiefenbacher U, Mai S, Wenz F. Memory function before and after whole brain radiotherapy in patients with and without brain metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 72: 1311–1318, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Yoder M. Defining human endothelial progenitor cells. J Thromb Haemost 7, Suppl 1: 49–52, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zhang Z, Zhang L, Jiang Q, Zhang R, Davies K, Powers C, Bruggen N, Chopp M. VEGF enhances angiogenesis and promotes blood-brain barrier leakage in the ischemic brain. J Clin Invest 106: 829–838, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zhao R, Pollack G. Regional differences in capillary density, perfusion rate, and P-glycoprotein activity: a quantitative analysis of regional drug exposure in the brain. Biochem Pharmacol 78: 1052–1059, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]