Abstract

We previously reported that the myocardial energetic state, as defined by the ratio of phosphocreatine to ATP (PCr/ATP), was preserved at baseline (BL) in a swine model of chronic myocardial ischemia with mild reduction of myocardial blood flow (MBF) 10 wk after the placement of an external constrictor on the left anterior descending coronary artery. It remains to be seen whether this stable energetic state is maintained at a longer-term follow-up. Hibernating myocardium (HB) was created in minipigs (n = 7) by the placement of an external constrictor (1.25 mm internal diameter) on the left anterior descending coronary artery. Function was assessed with MRI at regular intervals until 6 mo. At 6 mo, myocardial energetic in the HB was assessed by 31P-magnetic resonance spectrometry and myocardial oxygenation was examined from the deoxymyoglobin signal using 1H-magnetic resonance spectrometry during BL, coronary vasodilation with adenosine, and high cardiac workload with dopamine and dobutamine (DpDb). MBF was measured with radiolabeled microspheres. At BL, systolic thickening fraction was significantly lower in the HB compared with remote region (34.4 ± 9.4 vs. 50.1 ± 10.7, P = 0.006). This was associated with a decreased MBF in the HB compared with the remote region (0.73 ± 0.08 vs. 0.97 ± 0.07 ml·min−1·g, P = 0.03). The HB PCr/ATP at BL was normal. DpDb resulted in a significant increase in rate pressure product, which caused a twofold increase in MBF in the HB and a threefold increase in the remote region. The systolic thickening fraction increased with DpDb, which was significantly higher in the remote region than HB (P < 0.05). The high cardiac workload was associated with a significant reduction in the HB PCr/ATP (P < 0.02), but this response was similar to normal myocardium. Thus HB has stable BL myocardial energetic despite the reduction MBF and regional left ventricular function. More importantly, HB has a reduced contractile reserve but has a similar energetic response to high cardiac workload like normal myocardium.

Keywords: spectroscopy

in clinical practice, hibernating myocardium refers to areas of regional dysfunction, decreased blood flow, and absence of scar in patients with coronary artery disease who are thought to recover after revascularization (30–31, 35). Hibernating myocardium is characterized by a balance between matched reductions in myocardial blood flow (MBF) and function (15, 16). The acute perfusion contraction matching in short-term hibernation is maintained up to 90 min after the initiation of moderate ischemia and is not sustained over several hours (15, 16). In animal models, chronic hibernating myocardium can be created by a constriction of a proximal coronary artery that leads to a progressive reduction in MBF and regional dysfunction (3–5, 8–9, 11–13, 23–25). Perfusion contraction matching in this model probably develops from single or repetitive bouts of stress-induced ischemia and reperfusion in the presence of severe coronary stenosis (15, 16). Thus there is a temporal progression from chronic stunning to hibernation in which the reduced resting blood flow is the result rather than the cause of chronic contractile dysfunction (3–5, 8–9, 11–13, 23–25). Decreased myocardial oxygen consumption has been observed in hibernating myocardium at rest and during an increase in myocardial oxygen demand that contrasts with the findings in short-term hibernating myocardium (2, 12). Chronic hibernating myocardium demonstrates the alteration in metabolism with an increase in glucose uptake and glycogen storage (8, 13, 23). The energetic state in the hibernating myocardium has been previously studied with diverse results (7, 17, 24, 36).

Our laboratory specializes in studying myocardial energetic states in vivo with NMR spectroscopy. Energetic state refers to ΔG, which is the free energy of ATP hydrolysis (34). ΔGATP (in kJ/mol) = ΔG° − RT ln ([ATP]/[ADP][Pi]), where ΔG° (−30.5 kJ/mol) is the value of ΔGATP under standard conditions of molarity, temperature, pH, and [Mg2+]; R is the gas constant (8.3 J/mol K); and T is temperature (in °K). ΔG is linearly related to the myocardial phosphocreatine-to-ATP ratio (PCr/ATP) (34). The set point of the driving force and the efficiency of mitochondria ATP production [oxidative phosphorylation (mtOXPHOS)] are reflected by the myocardial PCr/ATP (ΔG). In chronic heart failure or acute myocardial ischemia, the myocardial energetic state is decreased, which is reflected by a decrease in PCr/ATP (18, 21–22, 26, 41, 43, 45). In a short-term follow-up of animals with chronic hibernation, we showed that despite a reduction in MBF and regional function, the hibernating myocardium has well-preserved myocardial energetics (24).

The aim of the present study is threefold. First, we aim to create a model of chronic hibernation in minipigs to allow us to study the energetic state in chronic hibernating myocardium up to 6 mo. Our second objective is to determine sequential measurements of MBF in this model with magnetic resonance (MR) imaging to assess for sequential changes in blood flow and its correlation with regional function. Third and most important, we hypothesize that chronic hibernating myocardium will maintain a stable energetic state in long-term follow-up up to 6 mo at baseline and with increased workload.

METHODS

All experiments were performed in accordance with the animal use guidelines of the University of Minnesota, and the experimental protocol was approved by the University of Minnesota Research Animal Resources Committee. The investigation conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, published by the National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No 85-23, Revised 2010).

Animal preparation.

Sinclair minipigs (Sinclair Research Center) were used for this study. Sinclair pigs are research-purpose bred and grow very slowly, which allowed us to follow these animals for long term. A chronic hibernation myocardium model was created in seven minipigs. Briefly, female Sinclair minipigs (5 mo old) were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (30 mg/kg iv), intubated, and ventilated with a respirator with supplemental oxygen. A left thoracotomy was performed. The left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) was dissected free, and a C-shaped titanium occluder (3 mm in length and 1.25 mm in internal diameter) was secured around the proximal vessel and gently closed with suture. In all animals, the pericardium and chest were closed in layers. Animals received standard postoperative care including analgesia until they ate normally and became active.

Regional function measurements.

Ventricular function was assessed using MRI before surgery and then at 2 wk, 1 mo, 4 mo, and 6 mo after instrumentation. MRI was performed on a 1.5 Tesla clinical scanner (Siemens Sontata, Siemens Medical Systems, Islen, NJ) using a phased-array four-channel surface coil and ECG gating as previously described in detail (45). Animals were anesthetized with 1% isoflurane and positioned in a supine position within the scanner. The protocol consisted of 1) localizing scouts to identify the long and short axis of the heart, 2) short- and long-axis cine for the measurement of global cardiac function, and 3) delayed contrast enhancement for the assessment of scar size. Steady-state free-precession “True-FISP” cine imaging used the following MR parameters: repetition time (TR) = 3.1 ms, echo time (TE) = 1.6 ms, flip angle = 79°, matrix size = 256 × 120, field of view = 340 mm × 265 mm, and slice thickness = 6 mm (4-mm gap between slices), and 16–20 phases were acquired across the cardiac cycle. Global function and regional wall thickness data were computed from the short-axis cine images using MASS (Medis Medical Imaging Systems, Leiden, The Netherlands) for the manual segmentation of the endocardial and epicardial surfaces at both end diastole and end systole from base to apex. End diastole and end systole were determined by evaluating the largest and smallest ventricular volumes during a cycle. Short-axis turboFLASH imaging, from base to apex, used TR = 16 ms, TE = 4 ms, inversion time = ∼220 ms, flip angle = 30°, matrix size = 256 × 148, field of view = 320 mm × 185 mm, slice thickness = 6 mm (0-mm gap between slices), and two signal averages. The appropriate inversion time was chosen to adequately null the signal intensity (SI) of normal myocardium. The left ventricular (LV) papillary muscles, as well as the LV short and long axis, were used as landmarkers for the cardiac MRI and for indentifying the LAD region. The spatial resolution of the MRI measurements is very high (∼1 to 2 mm).

MBF with first-pass perfusion MRI.

Sequential MBF measurements were obtained before surgery and then at 2 wk, 1 mo, 4 mo, and 6 mo after instrumentation. Perfusion imaging was performed with a bolus injection of 0.025 mmol/kg of gadolinium-diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid at 5 ml/s through a power injector. We chose this dose to be in the linear range of gadolinium-diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid concentration and SI within the blood pool. A saturation-recovery gradient echo imaging with an echo-train readout was used. The field of view was 30 cm2, matrix was 1.4 × 1.4 mm, and short-axis slice thickness was 8 mm and TR = 6.3 ms, TE = 1.3 ms, flip angle = 20°, and the echo train = 4. During bolus transit, three to four short-axis images were acquired per one R-R interval gated to the electrocardiographic signal of the animal over 40 to 60 heart beats.

Perfusion images were analyzed off-line with an interactive data language-based software program (Cine Tool GEMS, Milwaukee, WI). Time intensity curves (TICs) were generated from both the LV blood pool to obtain the arterial input function to the coronary circulation and from the myocardial tissue. These were 1.0 to 1.5 cm2 in area to coincide with the volume of the pathological sections. The concept of deconvolution of arterial input function with a shaped function to fit the tissue enhancement curve was employed as first described by Axel (1), tissue mean transit time from dynamic-computed tomography by a simple deconvolution technique, and adapted to cardiac MR (19). A Fermi function is used to deconvolve the arterial input function to fit the myocardial TIC in a region of interest. Perfusion scans were acquired for 40 R-R intervals, and the entire myocardial TIC was used to generate the fit with the arterial input function. The resultant amplitude of the Fermi function after the fit reflects the absolute MBF (1, 19). Signal noise was calculated for each study by measuring the SD of the mean SI to a region of interest outside the chest cavity. This was done to separate the impact of noise from the tissue SI. The contrast enhancement ratio was calculated by the following: (peak enhancement − precontrast) SI/precontrast SI, during femoral arterial pressure perfusion.

MBF measurement with microspheres.

MBF was measured using radionuclide-labeled microspheres 15 μm in diameter, labeled with four different radioisotopes (51Cr, 85Sr, 95Nb, and 46Sc) during the terminal NMR study at 6-mo follow-up. Microsphere suspension containing 2 × 106 microspheres was injected through the left atrial catheter while a reference sample of arterial blood was withdrawn from the aortic catheter at a rate 15 ml/min beginning 5 s before the microsphere injection and continuing for 120 s. Radioactivity in the myocardial and blood reference specimens was determined using a gamma spectrometer (Packard Instrument, Downers Grove, IL) at window settings chosen for the combination of radioisotopes used during the study. Activity corrected for overlap between isotopes and for background was used to compute blood flow as milliliter per gram of myocardium per minute.

Surgical preparation for open-chest MR spectroscopy study.

Detailed surgical preparations for MR spectroscopy (MRS) study are published previously (18, 38, 40). Briefly, animals were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (30 mg/kg, followed by a 4 mg·kg−1·h−1 iv), intubated, and ventilated with a respirator and supplemental oxygen. Arterial blood gases were maintained within the physiological range by adjustments of the ventilator settings and oxygen flow. Heparin-filled polyvinyl chloride catheters (3.0 mm outer diameter) were inserted into the ascending aorta and inferior vena cava. A sternotomy was performed, and the heart was suspended in a pericardial cradle. A third heparin-filled catheter was introduced into the LV through the apical dimple and secured with a purse string suture. A 25-mm-diameter NMR surface coil was sutured onto the anterior wall of the LV. The pericardial cradle was then released, and the heart was allowed to assume its normal position in the chest. The surface coil leads were connected to a balanced-tuned external circuit, and the animals were positioned within the magnet. To compensate for insensible fluid loss in the open chest studies, we routinely administer saline at a rate of 1 ml/min iv during the entire experimental data acquisition. Ventilation rate, volume, and inspired oxygen content were adjusted to maintain physiological values for arterial Po2, Pco2, and pH. Aortic and LV pressures were monitored continuously throughout the study. Hemodynamic measurements were acquired simultaneously with the 1H- and 31P-MR spectra.

MRS study protocol and hemodynamic measurements.

Hemodynamic measurements were acquired simultaneously with the NMR spectra. Aortic and LV pressures were measured using pressure transducers positioned at midchest level (38, 42–43) and recorded on an eight-channel recorder. After all the baseline data were obtained, animals received adenosine to cause maximal vasodilation and the measurements were repeated. This was followed by a combined dobutamine and dopamine infusion (20 μg·kg−1·min−1 each) to induce a very high cardiac work state. After we waited for ∼5 min after the initiation of catecholamine infusion, all the spectroscopic and hemodynamic data were again measured under the high cardiac work states.

31P-NMR spectroscopy technique.

31P-NMR spectroscopy has been used to study myocardial energetics (14). NMR spectroscopy was performed at 6-mo follow-up in a 4.7-T magnet. Magnetic field shimming to improve the magnetic field homogeneity of the heart was achieved by the “auto-shim” scheme (Varian Association). Spatially localized 31P-NMR spectroscopy was performed using the RAPP-ISIS/FSW method (27, 38, 42–43), which is the rotating-frame experiment using adiabatic plane-rotation pulses for phase modulation (RAPP)-imaging-selected in vivo spectroscopy (ISIS)/Fourier series window (FSW) method. Detailed experiments documenting voxel profiles, voxel volumes, and spatial resolution attained by this method have been previously published. In this application of RAPP-ISIS/FSW, the signal origin was first restricted to a 12 × 12-mm2 two-dimensional column perpendicular to the LV wall. The signal was later localized into three well-resolved and five partially resolved layers along the column and, hence, across the LV wall. The localization along the column was based on B1-phase encoding and employed a nine-term FSW as previously described (27, 38, 42–43). The phase-encoded data were used to generate a voxel or a “window” that can be shifted arbitrarily by post-data acquisition processing along the phase encode direction (in this case perpendicular to the surface coil and thus the heart wall); consequently, voxels were generated at different distances or “depths” from the outer LV wall. However, we normally present five voxels centered about 45°, 60°, 90°, 120°, and 135° phase angles as previously described. There is absolutely no overlap between the 135° voxel (corresponding to the subepicardium) and the 45° voxel (corresponding to the subendocardium). Whole wall spectra were obtained with the ISIS technique, defining a column 12 × 12 mm2 perpendicular to the heart wall. The calibration of spectroscopic parameters was facilitated by placing a polyethylene capillary filled with 15 μl of 3 M/l phosphonoacetic acid into the inner diameter of the surface coil. This phosphonoacetic acid standard was used only for calculating the 90° pulse length of the RAPP-ISIS method (27, 38, 42–43). The position of the voxels relative to the coil was set according to the B1 strength at the coil center, which was experimentally determined in each case by measuring the 90° pulse length for the phosphonoacetic acid standard contained in the reference capillary at the coil center. NMR data acquisition was gated to the cardiac and respiratory cycles using the cardiac cycle as the master clock to drive both the respirator and the spectrometer as previously described (27, 38, 42–43). The surface coil was constructed from a single turn copper wire 25 mm in diameter with each side of the coil leads soldered to a 33-pF capacitor. Complete transmural data sets were obtained in 10-min time blocks using a TR of 6 to 7 s to allow for a full relaxation for ATP and Pi and ∼95% relaxation of the PCr resonance (27, 38, 42–43). PCr/ATP values were calculated for each transmurally differentiated spectra set as previously described (27, 38, 42–43). All resonance intensities were quantified using integration routines provided by the SISCO software.

Creatine kinase kinetics measurement with 31P-MRS saturation transfer.

A double-tuned (200 MHz for 1H and 81 MHz for 31P) surface coil (diameter, 28 mm) was used for radiofrequency (RF) transmission and signal detection. A chemical shift selective pulse sequence was employed to saturate the ATPγ resonance (39); this sequence consisted of a 90° Sinc RF excitation pulse, followed by a short half-sine gradient pulse in all three orthogonal axes to enhance the dephasing of transverse magnetization. This chemical shift selective sequence was repetitively applied to ensure a complete saturation of the ATPγ resonance. The TR for signal acquisition of 12 s provided fully relaxed ATPγ and PCr resonances. Control spectra were acquired with the saturation carrier frequency setting on the opposite side of the PCr resonance with a frequency difference identical to that between PCr and ATPγ. The relative change of the PCr resonance intensity between the saturated and control spectra is proportional to the forward rate constant (kf) in the exchange reaction between PCr and ATP. All spectra were recorded with a spectral width of 6,000 Hz. The forward rate of creatine kinase (CK) (kf, PCr→ATPγ) and the intrinsic longitudinal relaxation time for PCr (T1) were calculated based on the two-site chemical exchange model as follows: kf = (ΔM/M0)/T1* and 1/T1 = 1/T1* − kf, where kf and T1 represent the pseudo-first-order rate constant and the intrinsic longitudinal relaxation time of PCr, respectively; ΔM = M0 − Minfinite, where M0 and Minfinite represent the magnetization at saturation zero and infinite times, respectively; and T1* is the time constant that describes the integral of PCr magnetization decay as the time of saturation of ATPγ increased from zero to infinity. The CK forward flux rate (Fluxf) was calculated as the product of kf and the myocardial PCr concentration (Fluxf = kf[PCr]). Each set of spectra for saturation transfer measurements required ∼6.2 min.

1H-NMR spectroscopy technique.

1H-NMR spectroscopy was performed on 4.7-T, and the methods have been previously reported in detail (6, 27). In brief, RF transmission and signal detection were performed with the dually tuned 28-mm diameter surface coil. A single-pulse collection sequence with a frequency selective Gaussian excitation pulse (1 ms) was used to selectively excite the N-δ proton resonance signal of the proximal histidine in deoxymyoglobin (Mb-δ). This technique provided sufficient water suppression because of the large chemical shift difference between water and Mb-δ (>14 kHz). The NMR signal was optimized by adjusting the RF pulse power using the water signal as a reference. A short TR (25 ms) was used because of the short T1 of Mb-δ. Each spectrum was acquired in 5 min (10,000 free induction decays). Although the short T1 of Mb-δ and fast acquisition prevent gating to the cardiac cycle, the signal loss due to motion is negligible compared with the inherently broad line width of the Mb-δ peak.

Statistics.

Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA (hibernating vs. remote, and baseline vs. time) with post hoc analysis. For the comparison between the two treatment groups, the conventional significance level of type I error (P < 0.05) was used. The Bonferroni correction for the significance level was used to take into account multiple comparisons. All values are expressed as means ± SD. All statistical analyses were performed in SigmaStat version 3.5 (San Jose, CA).

RESULTS

Resting MBF in hibernating myocardium.

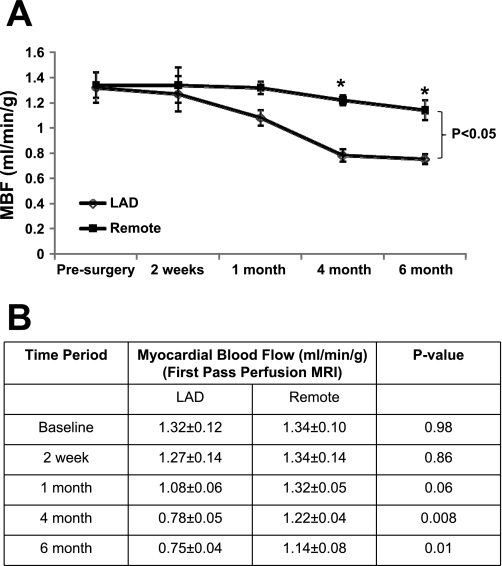

A titanium C-shaped occluder device with an internal diameter of 1.25 mm was placed over the proximal LAD. MR angiography was performed to determine the progression in severity of stenosis over time. It showed that at 1 mo there is ∼75% stenosis, and it progresses to >90% stenosis of the proximal LAD at 4 mo, but it was not completely occluded. There was a gradual decline of MBF in the anterior region of the heart. Resting MBF data obtained with perfusion MRI is summarized in Fig. 1. There was a trend toward a decreased MBF in the LAD territory compared with the remote region at 1 mo (1.08 ± 0.06 vs. 1.32 ± 0.05 ml·min−1·g−1, P = 0.06). At 4 mo, the LAD region had significantly decreased MBF than the remote region (0.78 ± 0.05 vs. 1.22 ± 0.04 ml·min−1·g−1, P = 0.008), which persisted up to the 6 mo follow-up (0.75 ± 0.04 vs. 1.14 ± 0.08 ml·min−1·g−1, P = 0.01).

Fig. 1.

Temporal changes in myocardial blood flow (MBF) in chronic hibernating myocardium (HB) as measured by first-pass perfusion MRI. A: MBF over time. B: MBF. LAD, left anterior descending coronary artery. *P < 0.05.

Coronary flow reserve in hibernating myocardium.

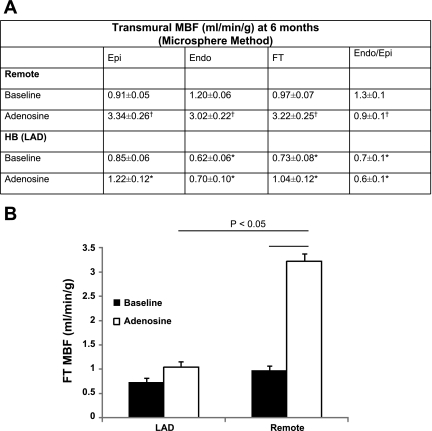

During the final terminal study at 6 mo, MBF was measured by an injection of microspheres at baseline and after intravenous adenosine administration (Fig. 2). The baseline MBF data correlated with the perfusion MRI data obtained at baseline at 6 mo. This demonstrates that at baseline, hibernating myocardium has decreased MBF compared with remote myocardium (0.73 ± 0.08 vs. 0.97 ± 0.07 ml·min−1·g−1, P < 0.05). Moreover, subendocardial blood flow (0.62 ± 0.06 vs. 1.20 ± 0.06 ml·min−1·g−1, P < 0.05) showed the most dramatic decrease in the hibernating myocardium with subsequent decrease in the subendothelium-to-subepithelium ratio (endo/epi). After adenosine vasodilation, MBF was critically impaired in the LAD region and only increased minimally (0.73 ± 0.08 vs. 1.04 ± 0.12 ml·min−1·g−1, P = not significant) compared with the more than threefold increase in MBF in the remote region (0.97 ± 0.07 vs. 3.22 ± 0.25 ml·min−1·g−1, P = 0.0007) (Fig. 2). Coronary flow reserve (equals MBF after maximal hyperemia with adenosine/MBF at rest) was calculated and was significantly lower in hibernating myocardium compared with remote region (1.38 ± 0.12 in hibernating myocardium vs. 3.36 ± 0.14 in remote myocardium, P < 0.05).

Fig. 2.

Myocardial perfusion reserve is diminished in chronic HB. A: transmural MBF data at 6 mo using microsphere method. Values are means ± SD. *P < 0.05 compared with remote; †P < 0.05 compared with baseline. B: the full-thickness MBF changes with adenosine in remote and HB. FT, Fourier transform; endo/epi, ratio of subendothelium to subepithelium.

Ventricular function in hibernating myocardium.

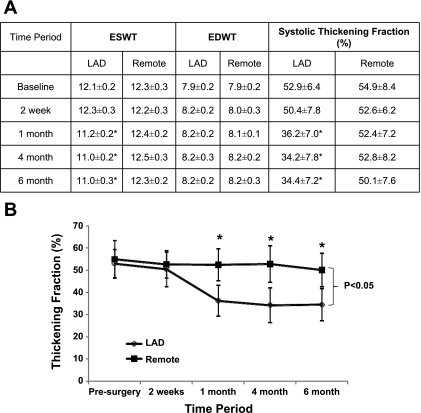

The weights of the animal were 20 ± 3 kg at 6 mo. Serial measurements of ventricular volumes, ventricular mass, and ejection fraction have been summarized in Table 1. These demonstrate that the global LV function was normal in all the animals throughout the follow-up period. There was no evidence of myocardial infarction by delayed enhanced MRI. None of the animals developed clinical heart failure, LV end-diastolic pressure was normal in all animals at 6 mo (2.8 ± 3.3 mmHg), and none of the animals had an LV end-diastolic pressure greater than 10 mmHg. There were two animals that died from sudden cardiac death, and thus mortality was 22% over a period of 6 mo. Regional ventricular function is summarized in Fig. 3. Systolic thickening fraction was significantly decreased in the LAD region compared with the remote region at 1 mo (36.2 ± 7.0% vs. 52.4 ± 7.2%, P = 0.04). This persisted at 4 mo (34.2 ± 7.8% vs. 52.8 ± 8.2%, P = 0.02) and 6 mo (34.4 ± 7.2% vs. 50.1 ± 7.6%, P = 0.02).

Table 1.

Ventricular volumes, mass, and ejection fraction

| EDV, ml | ESV, ml | SV, ml | EF, % | LVED Mass, g | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 16.9 ± 2.6 | 7.6 ± 1.8 | 9.3 ± 0.8 | 55.1 ± 2.2 | 35.20 ± 2.2 |

| 2 wk | 19.6 ± 1.3 | 8.9 ± 1.0 | 10.7 ± 0.5 | 55.5 ± 2.5 | 36.10 ± 2.4 |

| 1 mo | 16.7 ± 2.6 | 7.7 ± 1.9 | 9.0 ± 1.1 | 55.2 ± 4.5 | 36.42 ± 2.8 |

| 4 mo | 26.9 ± 3.1* | 11.3 ± 0.1* | 15.5 ± 3.2* | 57.2 ± 2.6 | 40.63 ± 3.8* |

| 6 mo | 26.9 ± 4.3* | 11.9 ± 2.2* | 15.1 ± 2.5* | 56.2 ± 3.6 | 44.12 ± 3.6* |

Values are means ± SD. EDV, end-diastolic volume; ESV, end-systolic volume; SV, stroke volume; EF, ejection fraction; LVED mass, left ventricular end-diastolic mass.

P < 0.05 compared with baseline.

Fig. 3.

Temporal changes in regional ventricular function in chronic HB. A: wall thickness and systolic thickening fraction. Values are means ± SD. ESWT, end-systolic wall thickness; EDWT, end-diastolic wall thickness. *P < 0.05 compared with remote. B: systolic thickening fraction over time. *P < 0.05.

Response to increased cardiac workload in hibernating myocardium.

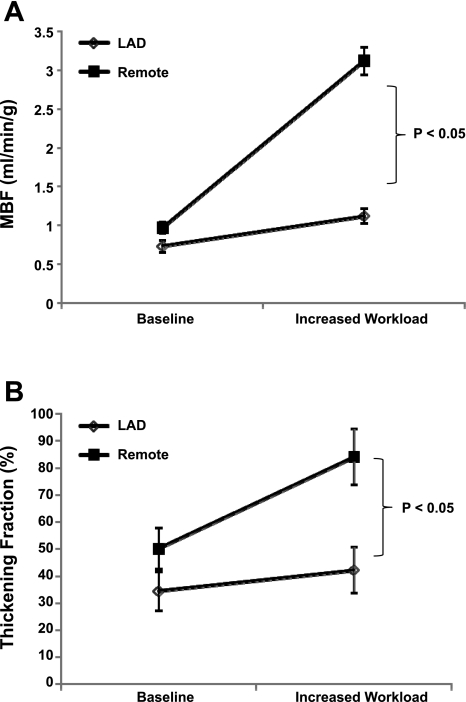

Even though the resting MBF and function in the hibernating myocardium was decreased, all the animals had an appropriate hemodynamic response to inotropic stimulation. An intravenous administration of dopamine and dobutamine resulted in a significant increase in heart rate (101.6 ± 14.9 vs. 153 ± 32.7 beats/min, P = 0.019), LV systolic pressure (103.8 ± 16.5 vs. 160 ± 40.5 mmHg, P = 0.04), and consequently rate pressure product (10.6 ± 2.3 × 103 vs. 25.0 ± 10.8 × 103, P = 0.04) (Table 2). This increase in workload was associated with only a 53.4% increase in MBF in the hibernating myocardium compared with a 222% increase in MBF in the remote myocardium (Fig. 4). The thickening fraction was similar at baseline in the hibernating myocardium and remote myocardium. Thickening fraction significantly increased in the remote area after inotropic stimulation compared with baseline (P < 0.05). Moreover, thickening fraction was significantly higher in the remote area compared with hibernating myocardium after inotropic stimulation (84.1 ± 10.4% vs. 42.2 ± 8.6%, P = 0.006). However, there was no significant difference between the thickening fraction at baseline and the increased workload in the hibernating myocardium.

Table 2.

Hemodynamic data

| Baseline | Increased Workload | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heart rate, beats/min | 101.6 ± 14.9 | 153 ± 32.7 | 0.019 |

| LVSP, mmHg | 103.8 ± 16.5 | 160 ± 40.5 | 0.04 |

| RPP, ×103 | 10.6 ± 2.3 | 25.0 ± 10.8 | 0.04 |

Values are means ± SD. LVSP, left ventricular systolic pressure; RPP, rate pressure product.

Fig. 4.

Response to increased cardiac workload in chronic HB. A: response to MBF to increased workload. B: MBF.

Myocardial energetics in hibernating myocardium.

Transmural high-energy phosphate measurements in the hibernating myocardium are summarized in Table 3. In addition, these have been compared with normal minipig controls and historical normal controls (27, 39). This shows that the hibernating myocardium has a normal energetic state at baseline as reflected by the PCr/ATP. The subepicardial, subendocardial, and full thickness PCr/ATP values in the hibernating myocardium are 2.33 ± 0.09, 1.88 ± 0.06, and 2.25 ± 0.21, respectively, which are similar to normal minipigs and historical pig controls. As shown, there is a significant decrease in PCr/ATP with inotropic stimulation (1.84 ± 0.23 vs. 2.25 ± 0.21, P = 0.03), but this decrease is similar to what is observed in normal myocardium at a similar workload (27). The increased workload was associated with a 20.4 ± 0.12% decrease in ATP production rate via CK, which is again similar to previous observations in normal pigs at an increased workload (27). Transmural myocardial oxygenation, by in vivo 1H-MRS myoglobin saturation levels, demonstrated no myoglobin desaturation in the hibernating myocardium at rest or with increased cardiac workload. Thus myocardial ischemia is not observed in hibernating myocardium despite a depression in MBF and reduction in wall thickening.

Table 3.

Transmural high-energy phosphate

| Epi | Endo | FT | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hibernating myocardium | |||

| Baseline | 2.33 ± 0.09 | 1.88 ± 0.06 | 2.25 ± 0.21 |

| Increased work load | 1.94 ± 0.10* | 1.65 ± 0.14* | 1.84 ± 0.23* |

| Control (minipigs) | |||

| Baseline | 2.13 ± 0.08 | 1.97 ± 0.06 | 2.06 ± 0.06 |

| Historical control (normal pigs) | |||

| Baseline | 2.23 ± 0.08 | 1.92 ± 0.08 | 2.18 ± 0.06 |

| Increased workload | 1.73 ± 0.09* | 1.64 ± 0.09* | 1.70 ± 0.08* |

Values are means ± SD. Epi, subepithelium; Endo, subendothelium; FT, Fourier transform.

P < 0.05 compared with baseline within group.

The CK Fluxf was calculated as the product of kf and the myocardial PCr concentration (Fluxf = kf[PCr]), where [PCr] = [ATP] × PCr/ATP. ATP concentration in hibernating myocardium has been previously reported by Hu et al. (17) as 20.1 ± 1.0 μmol/g dry wt. Under baseline conditions in our study, the PCr/ATP and kf were 2.25 ± 0.21 and 0.40 ± 0.04 s−1. Thus Fluxf was calculated as 18.1 ± 2.1 μmol·g−1·s−1. This value is similar to what has been reported for normal pigs (20.3 ± 2.4 μmol·g−1·s−1) (26).

DISCUSSION

This study describes the longest follow-up of experimental chronic hibernation in a preclinical large animal model. It used cardiac MRI to demonstrate the temporal changes in blood flow and regional function in hibernating myocardium to elucidate the exact timing of the development of the phenomenon of hibernating myocardium in these animals. More importantly, it reveals that the myocardial energetic state as reflected by PCr/ATP is normal under baseline conditions up to 6 mo in hibernating myocardium despite a reduction in perfusion reserve and regional function. Furthermore, the decrease in PCr/ATP with increased workload in hibernating myocardium is similar to normal myocardium.

Creation of hibernating myocardium animal model.

Our previous study of myocardial energetic in hibernating myocardium was limited to a follow-up period of 10 wk because of the large size of the farm pigs that were not able to fit in the bore size of the magnet used for MR studies (24). Thus, in the current study we used minipigs that have been shown to grow at a slower rate and thus do not attain a large size despite a longer follow-up period. This allowed us to follow the function and blood flow in the hibernating myocardium up to 6 mo and study the myocardial energetic in the hibernating myocardium at this longer follow-up. A titanium C-shaped occluder device with an internal diameter of 1.25 mm was placed over the proximal LAD, which is smaller than the 1.4 mm size used in the farm pig study (24). MR angiography was performed to determine the progression in severity of stenosis over time. It showed that at 1 mo there is ∼75% stenosis, and it progresses to >90% stenosis of the proximal LAD at 4 mo, but it was not completely occluded. It has been previously shown that hibernating myocardium develops regardless of whether the chronic stenosis was eventually totally occluded or remained patent; however, the inotropic reserve that was recruited by epinephrine depended on coronary reserve and was greater with a patent artery in that study (10). There was no evidence of myocardial infarction by late enhanced gadolinium MR imaging and on gross visualization at the time of death at 6 mo. Focal myocardial damage exceeding 5% of the myocardium within the region of interest seems to be necessary for the detection of late gadolinium enhancement in vivo in an experimental model of coronary microembolization (28). Thus smaller areas of fibrosis cannot be excluded in the present study.

Temporal changes in MBF in hibernating myocardium.

A unique feature of our study was the ability to examine the serial changes of MBF noninvasively using quantitative MR perfusion imaging techniques. This showed that the MBF in the hibernating myocardium started to decline at 1 mo. Thus the absolute MBF in the hibernating myocardium was significantly lower than the remote region at 4- and 6-mo follow-up. Cardiac MR perfusion imaging has been used to demonstrate decreased resting MBF in patients with coronary artery disease and regional LV dysfunction (33). There is an excellent correlation between microsphere and MRI MBF measures. We have previously shown that hypoperfused regions, identified with microspheres, on the first-pass MR images displayed significantly decreased signal intensities compared with normally perfused myocardium (P < 0.0007) (37). Moreover, flow estimates by first-pass MR imaging averaged 1.2 ± 0.5 ml·min−1·g−1 (n = 29), compared with 1.3 ± 0.3 ml·min−1·g−1 obtained with tracer microspheres in the same tissue specimens at the same time. In the present study, MBF in control myocardium at 6 mo is 1.14 ± 0.08 and 0.97 ± 0.07 by MR perfusion imaging and microspheres, respectively, while in hibernating myocardium at 6 mo the MBF is 0.75 ± 0.04 and 0.73 ± 0.08. We believe it is the first time that sequential MBF measurements have been obtained in an animal model of chronic hibernating myocardium. Transmural MBF measurements at 6 mo using microsphere also showed that the subendocardial layer had the most significant decrease in MBF with a subsequent decrease in the endo/epi MBF ratio. The myocardial perfusion reserve was also markedly diminished in the hibernating myocardium as shown previously (12).

It is interesting to note that systolic thickening fraction was maintained in hibernating myocardium between 1 and 6 mo (Fig. 3), whereas the MBF graduately continue to decrease by an additional 25% (Fig. 1), which suggests that the hibernating myocardium is becoming more efficient between 1 and 6 mo (maintaining the same function while being provided less blood flow). Assuming the mtOXPHOS is unchanged between 1–6 mo, this observation would suggest that a similar amount of myocardial thickening contraction requires less supporting ATP in month 6 compared with month 1. The mechanism for this observation warrants future studies such as using tagged MRI to track three-dimensional regional myocardial motion vectors in modeling the efficiency of LV ejection (20, 46).

Preserved baseline myocardial energetics in chronic hibernating myocardium.

In short-term hibernation myocardium, sequential biopsy-based measurements of ATP, PCr, creatine, and Pi revealed a decrease in the free-energy change of ATP hydrolysis during early ischemia with a subsequent recovery during continued 90 min ischemia (22). A key feature of this study is that the myocardial energetic state as measured by in vivo NMR spectroscopy is stable in chronic hibernating myocardium. Energetic state refers to ΔG, which is the free energy of ATP hydrolysis (34). ΔGATP (in kJ/mol) = ΔG° − RT ln ([ATP]/[ADP][Pi]), where ΔG° (−30.5 kJ/mol) is the value of ΔGATP under standard conditions of molarity, temperature, pH, and [Mg2+]; R is the gas constant (8.3 J/mol K), and T is temperature (in °K). ΔG is linearly related to the myocardial PCr/ATP (34). The set point of the driving force and the efficiency of mitochondria ATP production (mtOXPHOS) are reflected by the myocardial PCr/ATP (ΔG). In chronic heart failure or acute myocardial ischemia, the myocardial energetic state is decreased, which is reflected by a decrease in PCr/ATP (41, 43). Baseline high-energy phosphate levels have been previously studied in animal models of hibernating myocardium and human hibernating myocardium with differing results (7, 17, 24, 36). Elsasser et al. (7) studied 16 patients with coronary artery disease and LV dysfunction who had documented hibernating myocardium detected by thallium-201 scintigraphy, radionuclide ventriculography, and low-dose dobutamine echocardiography. All these patients had an improvement of LV function with revascularization (7). Myocardial biopsy specimens from the hibernating myocardium regions revealed a significant depression of PCr, adenosine triphosphate, and creatine and a significant increase in lactate levels and acidosis (7). They concluded that hibernating myocardium demonstrated a decrease in free energy of ATP hydrolysis and thus is energy depleted (7). Wiggers et al. (36) studied the myocardial energetic in 25 patients with coronary artery disease and LV dysfunction, but these authors further categorized the dysfunctional myocardium into reversible (hibernating) and irreversible based on improvement after revascularization. Biopsy specimens revealed similar ATP/ADP, lactate levels, and glucose uptake in hibernating and remote myocardium; however, the irreversible myocardium had significantly decreased ATP/ADP and glucose uptake and significantly increased lactate levels (36). In contrast to the study of Elsasser et al. (7), these authors concluded that the energy stores in hibernating myocardium are well preserved (7, 36). One of the reasons for this discrepancy could be the increased fibrosis (30%) in the hibernating myocardial specimens in the study of Elsasser et al. (7). In a porcine model of chronic hibernating myocardium, Hu et al. (17) report normal baseline total creatine, PCr, and ATP/ADP in biopsy specimens from hibernating myocardium 3 mo after the placement of the ameroid occluder. These authors did observe a global reduction of absolute ATP, ADP, and total adenine nucleotide levels in the hibernating myocardium, but despite these reductions, the overall energetic state as determined by the ATP/ADP and cardioplegia levels was preserved (17). Our group has the unique opportunity to study the myocardial energetic in vivo with NMR spectroscopy as opposed to measuring the levels of high-energy phosphate in vitro in biopsy specimens. We have previously shown that the myocardial energetic state as determined by PCr/ATP is maintained at 10 wk in a porcine model of chronic hibernating myocardium (24). Unfortunately, we were not able to perform a longer follow-up on these animals because of their large size. In the current study, a minipig model of chronic hibernating myocardium allowed us to study the myocardial energetic up to 6 mo follow-up. We demonstrate that the transmural PCr/ATP is normal in hibernating myocardium at 6 mo, reflecting a stable energetic state despite a reduction in regional blood flow and function. Furthermore, 1H-NMR spectroscopy does not reveal any baseline Mb-δ, showing that these tissues are not ischemic despite a reduction in blood flow. The preservation of a stable energetic state reflects the ability of hibernating myocardium to balance the supply and demand, and this may be achieved by an intrinsic downregulation of its metabolic needs. Using a proteomic approach, Page et al. (29) have shown that hibernating myocardium developed a significant downregulation of many mitochondrial proteins such as proteins involved in the major entry points to oxidative metabolism (e.g., pyruvate dehydrogenase complex and acyl-CoA dehydrogenase) and enzymes involved in electron transport (e.g., complexes I, III, and V) (29).

Response to increased workload in hibernating myocardium.

The animals with hibernating myocardium demonstrated an appropriate hemodynamic response to inotropic stimulation with a subnormal increase in blood flow and regional function. It has been previously shown in a short-term hibernation model that inotropic stimulation with dobutamine for 5 min increases contractile function without increasing blood flow and disrupts the recovery of PCr and lactate consumption. If inotropic stimulation is maintained for 90 min, the metabolic deterioration is followed by myocardial infarction (32). In our present study, the increased workload was associated with a decrease in the PCr/ATP, which is similar to the decrease seen in normal myocardium previously at a similar workload (rate pressure product, ∼23,000). Thus, the hibernating myocardium has a stable energetic state, implying similar to normal myocardium. The decreased PCr/ATP values during dobutamine infusion probably reflect a change in the kinetics of OXPHOS or intermediary metabolic steps rather than a myocyte oxygenation-related limitation of ATP synthetic capacity. In contrast to this response in chronic hibernating myocardium, we have previously demonstrated a dramatic decrease in PCr/ATP after dobutamine stimulation in animals with moderate acute coronary artery stenosis. At this level of acute coronary artery stenosis with a state of abolished coronary flow reserve and a minor decrease of MBF, there is mild reduction of PCr/ATP at basal cardiac work state (PCr/ATP, ∼1.99) but a marked further reduction of PCr/ATP (to ∼1.40) during a higher cardiac work state (44). It is possible that intrinsic changes in the mitochondria that reduce oxidant damage within hibernating myocardium preserve energy at high work states. Hu et al. (17) have shown that hibernating myocardium have a significant reduction in mitochondrial function in vitro as reflected by a significant reduction in the respiratory control ratio mainly because of a decrease in state 3 respiration. This was also shown by Mc Falls et al. (25) who studied isolated mitochondria from hibernating myocardium and demonstrated a decreased respiratory control ratio. They further demonstrated that the reduction in oxidant damage may also be related to an increase in uncoupling protein 2 in hibernating myocardium (25).

Conclusion.

Thus long-term chronic hibernating myocardium has a relatively well-preserved stable energetic state despite a reduction in regional blood flow and function. This is probably related to an intrinsic downregulation in the mitochondrial function that minimizes oxidative stress and leads to a balanced supply and demand at baseline and increased workload.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants HL-50470, HL-67828, and HL-95077 and American Heart Association Greater Midwest Predoctoral Award 0810015Z (to M. N. Jameel).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Drs. Yuan and Zhang for providing the statistics consultations.

REFERENCES

- 1. Axel L. Tissue mean transit time from dynamic computed tomography by a simple deconvolution technique. Invest Radiol 18: 94–99, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Canty JM, Jr, Fallavollita JA. Hibernating myocardium represents a primary downregulation of regional myocardial oxygen consumption distal to a critical coronary stenosis. Basic Res Cardiol 90: 5–8, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Canty JM, Jr, Fallavollita JA. Lessons from experimental models of hibernating myocardium. Coron Artery Dis 12: 371–380, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Canty JM, Jr, Fallavollita JA. Resting myocardial flow in hibernating myocardium: validating animal models of human pathophysiology. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 277: H417–H422, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Canty JM, Jr, Suzuki G, Banas MD, Verheyen F, Borgers M, Fallavollita JA. Hibernating myocardium: chronically adapted to ischemia but vulnerable to sudden death. Circ Res 94: 1142–1149, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen W, Cho Y, Merkle H, Ye Y, Zhang Y, Gong G, Zhang J, Ugurbil K. In vitro and in vivo studies of 1H NMR visibility to detect deoxyhemoglobin and deoxymyoglobin signals in myocardium. Magn Reson Med 42: 1–5, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Elsasser A, Muller KD, Skwara W, Bode C, Kubler W, Vogt AM. Severe energy deprivation of human hibernating myocardium as possible common pathomechanism of contractile dysfunction, structural degeneration and cell death. J Am Coll Cardiol 39: 1189–1198, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fallavollita JA, Canty JM., Jr Differential 18F-2-deoxyglucose uptake in viable dysfunctional myocardium with normal resting perfusion: evidence for chronic stunning in pigs. Circulation 99: 2798–2805, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fallavollita JA, Lim H, Canty JM., Jr Myocyte apoptosis and reduced SR gene expression precede the transition from chronically stunned to hibernating myocardium. J Mol Cell Cardiol 33: 1937–1944, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fallavollita JA, Logue M, Canty JM., Jr Coronary patency and its relation to contractile reserve in hibernating myocardium. Cardiovasc Res 55: 131–140, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fallavollita JA, Logue M, Canty JM., Jr Stability of hibernating myocardium in pigs with a chronic left anterior descending coronary artery stenosis: absence of progressive fibrosis in the setting of stable reductions in flow, function and coronary flow reserve. J Am Coll Cardiol 37: 1989–1995, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fallavollita JA, Malm BJ, Canty JM., Jr Hibernating myocardium retains metabolic and contractile reserve despite regional reductions in flow, function, and oxygen consumption at rest. Circ Res 92: 48–55, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fallavollita JA, Perry BJ, Canty JM., Jr 18F-2-deoxyglucose deposition and regional flow in pigs with chronically dysfunctional myocardium. Evidence for transmural variations in chronic hibernating myocardium. Circulation 95: 1900–1909, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Guth BD, Martin JF, Heusch G, Ross J., Jr Regional myocardial blood flow, function and metabolism using phosphorus-31 nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy during ischemia and reperfusion in dogs. J Am Coll Cardiol 10: 673–681, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Heusch G. Hibernating myocardium. Physiol Rev 78: 1055–1085, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Heusch G, Schulz R, Rahimtoola SH. Myocardial hibernation: a delicate balance. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288: H984–H999, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hu Q, Suzuki G, Young RF, Page BJ, Fallavollita JA, Canty JM., Jr Reductions in mitochondrial O2 consumption and preservation of high-energy phosphate levels after simulated ischemia in chronic hibernating myocardium. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 297: H223–H232, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hu Q, Wang X, Lee J, Mansoor A, Liu J, Zeng L, Swingen C, Zhang G, Feygin J, Ochiai K, Bransford TL, From AH, Bache RJ, Zhang J. Profound bioenergetic abnormalities in peri-infarct myocardial regions. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291: H648–H657, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jerosch-Herold M, Wilke N, Stillman AE. Magnetic resonance quantification of the myocardial perfusion reserve with a Fermi function model for constrained deconvolution. Med Phys 25: 73–84, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li W, Yu X. Quantification of myocardial strain at early systole in mouse heart: restoration of undeformed tagging grid with single-point HARP. J Magn Reson Imaging 32: 608–614, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liu J, Wang C, Murakami Y, Gong G, Ishibashi Y, Prody C, Ochiai K, Bache RJ, Godinot C, Zhang J. Mitochondrial ATPase and high-energy phosphates in failing hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 281: H1319–H1326, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Martin C, Schulz R, Rose J, Heusch G. Inorganic phosphate content and free energy change of ATP hydrolysis in regional short-term hibernating myocardium. Cardiovasc Res 39: 318–326, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McFalls EO, Hou M, Bache RJ, Best A, Marx D, Sikora J, Ward HB. Activation of p38 MAPK and increased glucose transport in chronic hibernating swine myocardium. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 287: H1328–H1334, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McFalls EO, Kelly RF, Hu Q, Mansoor A, Lee J, Kuskowski M, Sikora J, Ward HB, Zhang J. The energetic state within hibernating myocardium is normal during dobutamine despite inhibition of ATP-dependent potassium channel opening with glibenclamide. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293: H2945–H2951, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. McFalls EO, Sluiter W, Schoonderwoerd K, Manintveld OC, Lamers JM, Bezstarosti K, van Beusekom HM, Sikora J, Ward HB, Merkus D, Duncker DJ. Mitochondrial adaptations within chronically ischemic swine myocardium. J Mol Cell Cardiol 41: 980–988, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Murakami Y, Zhang J, Eijgelshoven MH, Chen W, Carlyle WC, Zhang Y, Gong G, Bache RJ. Myocardial creatine kinase kinetics in hearts with postinfarction left ventricular remodeling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 276: H892–H900, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Murakami Y, Zhang Y, Cho YK, Mansoor AM, Chung JK, Chu C, Francis G, Ugurbil K, Bache RJ, From AH, Jerosch-Herold M, Wilke N, Zhang J. Myocardial oxygenation during high work states in hearts with postinfarction remodeling. Circulation 99: 942–948, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nassenstein K, Breuckmann F, Bucher C, Kaiser G, Konorza T, Schafer L, Konietzka I, de Greiff A, Heusch G, Erbel R, Barkhausen J. How much myocardial damage is necessary to enable detection of focal late gadolinium enhancement at cardiac MR imaging? Radiology 249: 829–835, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Page B, Young R, Iyer V, Suzuki G, Lis M, Korotchkina L, Patel MS, Blumenthal KM, Fallavollita JA, Canty JM., Jr Persistent regional downregulation in mitochondrial enzymes and upregulation of stress proteins in swine with chronic hibernating myocardium. Circ Res 102: 103–112, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rahimtoola SH. The hibernating myocardium. Am Heart J 117: 211–221, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rahimtoola SH. A perspective on the three large multicenter randomized clinical trials of coronary bypass surgery for chronic stable angina. Circulation 72: V123–V135, 1985 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schulz R, Rose J, Martin C, Brodde OE, Heusch G. Development of short-term myocardial hibernation. Its limitation by the severity of ischemia and inotropic stimulation. Circulation 88: 684–695, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Selvanayagam JB, Jerosch-Herold M, Porto I, Sheridan D, Cheng AS, Petersen SE, Searle N, Channon KM, Banning AP, Neubauer S. Resting myocardial blood flow is impaired in hibernating myocardium: a magnetic resonance study of quantitative perfusion assessment. Circulation 112: 3289–3296, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tian R, Ingwall JS. Energetic basis for reduced contractile reserve in isolated rat hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 270: H1207–H1216, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Vanoverschelde JL, Wijns W, Depre C, Essamri B, Heyndrickx GR, Borgers M, Bol A, Melin JA. Mechanisms of chronic regional postischemic dysfunction in humans. New insights from the study of noninfarcted collateral-dependent myocardium. Circulation 87: 1513–1523, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wiggers H, Noreng M, Paulsen PK, Bottcher M, Egeblad H, Nielsen TT, Botker HE. Energy stores and metabolites in chronic reversibly and irreversibly dysfunctional myocardium in humans. J Am Coll Cardiol 37: 100–108, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wilke N, Kroll K, Merkle H, Wang Y, Ishibashi Y, Xu Y, Zhang J, Jerosch-Herold M, Muhler A, Stillman AE, et al. Regional myocardial blood volume and flow: first-pass MR imaging with polylysine-Gd-DTPA. J Magn Reson Imaging 5: 227–237, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ye Y, Gong G, Ochiai K, Liu J, Zhang J. High-energy phosphate metabolism and creatine kinase in failing hearts: a new porcine model. Circulation 103: 1570–1576, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ye Y, Wang C, Zhang J, Cho YK, Gong G, Murakami Y, Bache RJ. Myocardial creatine kinase kinetics and isoform expression in hearts with severe LV hypertrophy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 281: H376–H386, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zeng L, Hu Q, Wang X, Mansoor A, Lee J, Feygin J, Zhang G, Suntharalingam P, Boozer S, Mhashilkar A, Panetta CJ, Swingen C, Deans R, From AH, Bache RJ, Verfaillie CM, Zhang J. Bioenergetic and functional consequences of bone marrow-derived multipotent progenitor cell transplantation in hearts with postinfarction left ventricular remodeling. Circulation 115: 1866–1875, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhang J, Ishibashi Y, Zhang Y, Eijgelshoven MH, Duncker DJ, Merkle H, Bache RJ, Ugurbil K, From AH. Myocardial bioenergetics during acute hibernation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 273: H1452–H1463, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zhang J, McDonald KM. Bioenergetic consequences of left ventricular remodeling. Circulation 92: 1011–1019, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zhang J, Merkle H, Hendrich K, Garwood M, From AH, Ugurbil K, Bache RJ. Bioenergetic abnormalities associated with severe left ventricular hypertrophy. J Clin Invest 92: 993–1003, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zhang J, Path G, Chepuri V, Homans DC, Merkle H, Hendrich K, Ugurbil K, Bache RJ, From AH. Effects of dobutamine on myocardial blood flow, contractile function, and bioenergetic responses distal to coronary stenosis: implications with regard to dobutamine stress testing. Am Heart J 129: 330–342, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zhang J, Wilke N, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Wang C, Eijgelshoven MH, Cho YK, Murakami Y, Ugurbil K, Bache RJ, From AH. Functional and bioenergetic consequences of postinfarction left ventricular remodeling in a new porcine model. MRI and 31 P-MRS study. Circulation 94: 1089–1100, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zhou R, Pickup S, Glickson JD, Scott CH, Ferrari VA. Assessment of global and regional myocardial function in the mouse using cine and tagged MRI. Magn Reson Med 49: 760–764, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]