Abstract

Different splice variants of the proinflammatory cytokine IL-32 are found in various tissues; their putative differences in biological function remain unknown. In the present study, we report that IL-32γ is the most active isoform of the cytokine. Splicing to one less active IL-32β appears to be a salvage mechanism to reduce inflammation. Adenoviral overexpression of IL-32γ (AdIL-32γ) resulted in exclusion of the IL-32γ–specific exon in vitro as well as in vivo, primarily leading to expression of IL-32β mRNA and protein. Splicing of the IL-32γ–specific exon was prevented by single-nucleotide mutation, which blocked recognition of the splice site by the spliceosome. Overexpression of splice-resistant IL-32γ in THP1 cells or rheumatoid arthritis (RA) synovial fibroblasts resulted in a greater induction of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, compared with IL-32β. Intraarticular introduction of IL-32γ in mice resulted in joint inflammation and induction of several mediators associated with joint destruction. In RA synovial fibroblasts, overexpression of primarily IL-32β showed minimal secretion and reduced cytokine production. In contrast, overexpression of splice-resistant IL-32γ in RA synovial fibroblasts exhibited marked secretion of IL-32γ. In RA, we observed increased IL-32γ expression compared with osteoarthritis synovial tissue. Furthermore, expression of TNFα and IL-6 correlated significantly with IL-32γ expression in RA, whereas this was not observed for IL-32β. These data reveal that naturally occurring IL-32γ can be spliced into IL-32β, which is a less potent proinflammatory mediator. Splicing of IL-32γ into IL-32β is a safety switch in controlling the effects of IL-32γ and thereby reduces chronic inflammation.

IL-32 is a proinflammatory cytokine that exists in six isoforms (1, 2). The cDNA coding for IL-32 previously described as NK4 (3) is the IL-32 isoform that contains all IL-32 exons resulting in the complete IL-32 transcript. The NK4 protein sequence predicted from the nucleotide sequence contains a potential signal cleavage site between amino acid positions 31 and 32 (3). Whether NK4 could be secreted was investigated by in vitro translation of NK4 RNA and processing of the protein product in the presence or absence of canine microsomes (3). By PAGE analysis, a reduction of 2–3 kDa in size in the presence of canine microsomes was observed, corresponding to the predicted signal cleavage site (3). After 12 y, NK4 was studied as a recombinant protein and renamed IL-32 (2). IL-32 was detected in supernatants of IL-12-, IL-18-, and IL-12- plus IL-18-stimulated human natural killer (NK) cells (2). Furthermore, in that study, IL-32 expression in supernatants of concavalin A-stimulated human peripheral blood mononuclear cells was found, suggesting IL-32 secretion (2).

IL-32 protein expression was observed in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and osteoarthritis (OA) synovial fluid (4) and in supernatants of IL-1β-, IFNγ-, and TNFα-stimulated HT-29 human intestinal epithelial cells (5), indicating IL-32 protein secretion or release by cell death. Increased IL-32 gene expression was observed in T cells undergoing apoptosis, and overexpressed IL-32 resulted in enhanced apoptosis in HeLa cells whereas down-regulation prevented apoptosis (1). Silencing of IL-32 resulted in significantly reduced keratinocyte apoptosis in atopic dermatitis (6). Additionally, cells from patients with chronic myelomonocytic leukemia expressed only a small fraction of IL-32 compared with cells from healthy donors, whereas in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome with hematopoietic failure, IL-32 expression is increased (7), indicating the relationship between IL-32 and apoptosis.

We previously reported that IL-32 is a cell-associated cytokine when human peripheral blood mononuclear cells are stimulated with LPS or mycobacterium tuberculosis, and IL-32 protein in the supernatants was barely detectable (8), indicating a role for intracellular IL-32. Furthermore, we demonstrated that intracellular IL-32γ via adenoviral overexpression could synergize with TLR2 and NOD2 ligands for the production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines (9). In several studies, silencing of endogenous IL-32 resulted in significant reduction of proinflammatory mediators and prevented apoptosis (7, 10–14).

In this study, we investigated the expression of several IL-32 isoforms in OA and RA synovial biopsies and the correlation between IL-32 isoforms and TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6, or CXCL8 expression. Unexpectedly, we observed that IL-32γ can be spliced into IL-32β and, with a single-nucleotide mutation, we were able to prevent IL-32γ splicing. This splice-resistant IL-32γ isoform enabled us to define the function of the naturally occurring IL-32γ isoform and compared it with IL-32β. All previous studies were done with recombinant IL-32. Moreover, we compared differences in IL-32 secretion in spliced and splice-resistant IL-32γ in RA synovial fibroblasts.

Results

Expression of IL-32 Isoforms in Human OA and RA Synovial Biopsies.

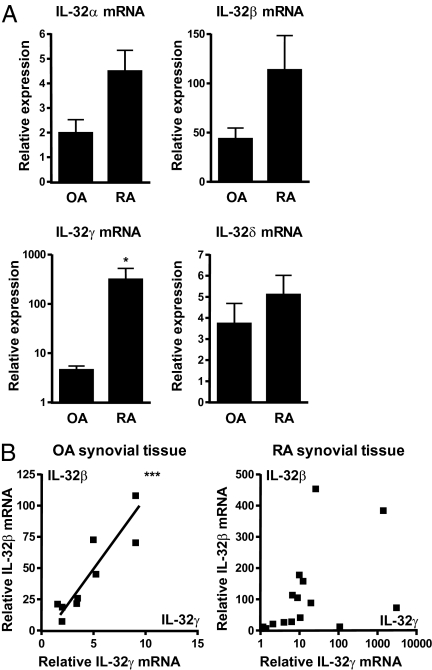

Although IL-32 expression is greater in RA and OA synovial lining (15), which isoform is expressed was unknown. As shown in Fig. 1A, OA as well as RA synovial tissue expression of IL-32α, IL-32β, IL-32γ, and IL-32δ mRNA was analyzed. The expression of IL-32γ was significantly increased in RA compared with OA synovial biopsies. Association between IL-32γ and IL-32β isoforms showed significant correlation in OA synovial tissue (Fig. 1B), but no correlation between IL-32γ and IL-32β was observed in RA synovial tissue.

Fig. 1.

IL-32α, IL-32β, IL-32γ, and IL-32δ expression and correlation in OA and RA synovial biopsies. RNA from synovial biopsies was isolated and used for determining IL-32 isoform expression. (A) IL-32γ mRNA expression was significantly enhanced in RA versus OA synovial biopsies (mean ± SEM; OA, n = 9; RA, n = 15; Mann–Whitney U test; *P < 0.05). (B) Correlation between IL-32γ and IL-32β isoforms in OA and RA synovial tissue (OA, n = 9, Pearson correlation test, Pearson r = 0.9023, P = 0.0009, ***P < 0.001; RA, n = 15, Pearson correlation test, nonsignificant).

Only IL-32γ Correlates with TNFα and IL-6 Expression in RA Synovial Tissue.

To investigate whether the difference in inflammatory status of synovial biopsies between RA and OA was responsible for the enhanced IL-32γ, we determined the expression of TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6, and CXCL8. Fig. 2A shows that RA synovial tissue expressed more proinflammatory mediators compared with OA. Next, we assessed whether TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6, or CXCL8 expression correlated with IL-32γ or IL-32β in RA synovial biopsies. TNFα and IL-6 correlated significantly with IL-32γ expression, whereas this was not observed for IL-32β (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Correlation between IL-32γ and TNFα or IL-6 in RA synovial tissue. (A) Enhanced TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6, and CXCL8 expression in RA synovial tissue (mean ± SEM; OA, n = 9; RA, n = 14; Mann-Whitney U test). (B) TNFα and IL-6 both correlated with IL-32γ expression in RA synovial tissue (RA, n = 14, Pearson correlation test, IL-6/IL-32γ, Pearson r = 0.9638, P < 0.0001; TNFα/IL-32γ, Pearson r = 0.9598, P < 0.0001, ***P < 0.001).

Splicing Regulates IL-32γ Expression, Resulting in Expression of IL-32β.

To explore the inflammatory properties of the IL-32γ isoform, we constructed an adenoviral vector (9). Adenoviral overexpression of IL-32γ (AdIL-32γ) resulted in expression of IL-32γ and IL-32β isoforms in HeLa cells (Fig. 3A). Using specific primers, two amplicons were produced, as shown in Fig. 3A. The larger amplicon contains the IL-32γ–specific exon, whereas the smaller amplicon aligned with the IL-32β sequence. By Western blot (Fig. 3A), we observed IL-32γ and IL-32β proteins as early as 8 h and greater amounts 20 h after viral transduction. Thus, IL-32γ mRNA was spliced into IL-32β. Moreover, there was more IL-32β protein than IL-32γ (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Splicing of IL-32γ results in expression of IL-32β, which can be prevented by single-nucleotide mutation. (A) Adenoviral overexpression of IL-32γ resulted in IL-32β and IL-32γ mRNA expression and primarily IL-32β protein production, as shown in HeLa cells. (B) Theoretical model. G-to-A mutation of the B2 donor splice site prevents IL-32γ-into-IL-32β splicing. (C) Overexpression of IL-32γM results in IL-32γ mRNA expression and protein production in HeLa cells. Furthermore, in THP1 cells, AdControl shows no IL-32 protein production, whereas AdIL-32γ–exposed cells show primarily IL-32β and some IL-32γ production. Moreover, AdIL-32γM-transduced cells show primarily IL-32γ and some IL-32β production. In addition, we quantified IL-32β or IL-32γ production and corrected for actin production in AdIL-32γ– or AdIL-32γM–transduced cells, respectively. (D) THP1 cells transduced with AdControl, AdIL-32γ, or AdIL-32γM followed by medium or IL-1β stimulation. AdIL-32γM-transduced THP1 cells showed enhanced secretion of IL-6 and CXCL8 protein compared with AdIL-32γ– or AdControl-exposed cells. Furthermore, AdIL-32γM-exposed cells showed enhanced IL-1β production compared with AdControl-transduced cells. Additionally, AdIL-32γ showed only enhanced CXCL8 production compared with AdControl-transduced cells (mean ± SEM, n = 4, Bonferroni's multiple-comparison test, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001).

To avoid IL-32γ-into-IL-32β splicing, we mutated the donor site GU into AU. Removal of the IL-32γ–specific exon by the spliceosome is facilitated by recognition of the GU donor and AG acceptor site (16), which results in exclusion of the exon (Fig. 3B). Mutation of the donor splice site prevented recognition by the spliceosome (17), and splicing of IL-32γ should not occur (Fig. 3B). The mutated IL-32γ mRNA derived from an adenoviral vector (AdIL-32γM) was not spliced into IL-32β mRNA as well as IL-32β protein. This occurred as early as 8 h and more so at 20 h after viral transduction (Fig. 3C). As shown in Fig. 3C, IL-32γ splicing was prevented in human THP1 cells transduced with AdIL-32γM. Prominent IL-32γ protein bands at 24 and 48 h were present, although some endogenous IL-32β protein was observed. In addition, AdIL-32γ–transduced human THP1 cells showed primarily IL-32β protein bands at 24 and 48 h (Fig. 3C), whereas AdControl-exposed THP1 cells showed no IL-32 proteins.

We next investigated whether IL-32α mRNA originated from IL-32γ transcripts. To avoid induction of endogenous IL-32 isoform expression, we transduced murine fibroblasts (3T3 cell line) with AdIL-32γ or AdIL-32γM. Fig. S1 A and B shows that both AdIL-32γ– and AdIL-32γM–derived transcripts can be spliced into IL-32α; however, we did not observe any IL-32α protein bands in HeLa- or THP1-transduced cells based on protein size.

IL-32γ Isoform Is a Potent Inducer of Proinflammatory Mediators Compared with IL-32β.

IL-1β, IL-6, and CXCL8 protein secretion was investigated in AdControl-, AdIL-32γ–, or AdIL-32γM–transduced human THP1 cells. AdIL-32γM-transduced cells showed significantly enhanced IL-1β, IL-6, and CXCL8 production compared with AdControl-exposed cells (Fig. 3D). In AdIL-32γ–transduced cells, there was augmented CXCL8 production compared with AdControl, as shown in Fig. 3D. However, AdIL-32γM-transduced cells showed significantly elevated levels of IL-6 and CXCL8 compared with AdIL-32γ–transduced cells (Fig. 3D). To verify that AdIL-32γ and AdIL-32γM are equally efficient in IL-32 production, we quantified IL-32β protein expression produced by AdIL-32γ compared with IL-32γ production induced by AdIL-32γM and corrected for actin levels. After 24 and 48 h, AdIL-32γ produced more IL-32β- than AdIL-32γM-induced IL-32γ production (Fig. 3C). These results demonstrate that IL-32γ is a more potent inducer of proinflammatory mediators than IL-32β.

In Vivo Overexpression of IL-32γ Results in Joint Inflammation.

To investigate the properties of AdIL-32γM in vivo, we first examined whether murine fibroblasts produced IL-32γ following transduction. AdIL-32γ–transduced 3T3 cells expressed IL-32γ and IL-32β, whereas AdIL-32γM-transduced cells only expressed IL-32γ (Fig. 4A). To confirm that IL-32γ is produced in vivo, AdIL-32γM was injected into C57BL/6 mice. Intraarticular injection of AdIL-32γ into mouse knee joints resulted in IL-32γ and IL-32β expression, whereas AdIL-32γM-injected joints expressed only IL-32γ (Fig. 4A). Intraarticular injection of AdIL-32γM resulted in significantly enhanced joint swelling compared with AdIL-32γ (Fig. 4A). Moreover, histological analysis showed enhanced synovial infiltrating cells in AdIL-32γM-exposed joints.

Fig. 4.

Aggravated arthritis in AdIL-32γM-exposed mice. (A) Splicing of IL-32γ into IL-32β in 3T3 cells and mice, which is not observed in AdIL-32γM-exposed mice. Enhanced macroscopic knee joint scores (mean ± SEM, n = 12, Mann–Whitney U test, ***P < 0.001) and more infiltrating cells in mice knee joints (mean ± SEM, n = 6, Mann–Whitney U test, **P < 0.01), which is shown by H&E staining. (B) Increased expression of TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-32γ (1 × 5 pooled synovial biopsies), whereas IL-32all expression was comparable between AdIL-32γ and AdIL-32γM. (C) Enhanced iNOS, MMP3, and MMP13 expression in patellar cartilage derived from AdIL-32γM-exposed mice (1 × 5 pooled patellar cartilage samples).

Expression of proinflammatory mediators was determined in synovial tissue and patellar cartilage. In synovial tissue, mRNA expression of TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-32γ was markedly enhanced in AdIL-32γM-exposed joints, compared with AdIL-32γ. Furthermore, iNOS, MMP3, and MMP13 mRNA levels were greater in patellae of AdIL-32γM-injected mice (Fig. 4C), but MMP9 expression was comparable in both groups. Because the expression of IL-32all (recognizing IL-32 α, β, γ, and δ isoforms) was comparable between AdIL-32γM and AdIL-32γ, we observed that both adenoviral vectors were equally efficient in viral transduction (Fig. 4B).

IL-32γ Isoform but Not IL-32β Is Secreted in Human RA Synovial Fibroblasts.

We hypothesized that IL-32γ is the isoform that can be secreted, because the IL-32γ–specific exon contains a potential signal peptide (3, 18). In supernatants of AdIL-32γ–transduced RA synovial fibroblasts, a small portion of IL-32 protein was observed (Fig. 5A). Most of the IL-32 protein remained intracellular. However, when stimulated with IL-1β or TNFα, there was enhanced IL-32γ secretion (Fig. 5A). Of particular interest, AdIL-32γM-transduced RA synovial fibroblasts secreted IL-32γ protein without stimulation (Fig. 5A). TNFα or IL-1β stimulation showed some additional secretion of IL-32γ protein.

Fig. 5.

Secretion of IL-32 can be enhanced by IL-1β or TNFα stimulation, whereas splice-resistant IL-32γ is directly secreted in RA synovial fibroblasts. (A) AdControl-transduced RA FLS showed low IL-32 concentrations both intra- and extracellularly. Secretion of IL-32 was significantly induced in AdIL-32γ–transduced RA FLS after IL-1β or TNFα stimulation, whereas medium control showed minimal secretion of IL-32 (mean ± SEM, n = 5, Mann–Whitney U test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). Moreover, AdIL-32γM-transduced RA FLS showed impressive secretion of IL-32γ compared with AdIL-32γ, whereas IL-1β or TNFα stimulation showed some increase (mean ± SEM, n = 5, Mann–Whitney U test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). (B) In addition, cell death was investigated by determining LDH release, which was not different between the groups (mean percentage LDH release ± SEM, n = 6, Dunnett's multiple-comparison test). (C) Splice-resistant IL-32γ was more potent in inducing IL-6 and CXCL8 compared with spliced IL-32γ or AdControl after IL-1β stimulation (fold increase protein level ± SEM, n = 5, Bonferroni's multiple-comparison test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01).

Because IL-32 is associated with cell death (1, 7), we determined the percentage lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release. There were no differences between cells exposed to adenovirus-, AdControl-, AdIL-32γ–, or AdIL-32γM–transduced RA synovial fibroblasts (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, we observed that IL-32γ was more potent in inducing IL-6 than IL-32β or control transduced RA fibroblast-like synoviocytes (FLS) after IL-1β stimulation (Fig. 5C). In addition, CXLC8 protein production after IL-1β stimulation was significantly enhanced by IL-32γ compared with control exposed RA FLS, whereas this was not observed for IL-32β (Fig. 5C).

Discussion

The splicing of the IL-32γ isoform into IL-32β was an unexpected finding associated with rather marked changes in the biological properties of IL-32. In the case of IL-32γ splicing, the lower abundance of this isoform resulted in reduced in vitro cytokine production as well as in vivo activity. Next, there was also an unexpected change in the amount of IL-32 secreted from RA synovial fibroblasts such that cells primarily expressing the IL-32γ isoform released significantly more compared with cells expressing IL-32β. From a clinical perspective, there was an excellent correlation of TNFα and IL-6 in mRNA levels in synovial tissues from RA patients with the IL-32γ but not the IL-32β isoform. Splicing is a rather common occurrence in transcripts but is rarely associated with clinically relevant phenotypic changes in the cell, as shown in this report. The present study also supports the concept that IL-32 is an example of self-imposed limitation of runaway inflammation by splicing to a less active isoform as well as restricting the product of the IL-32β isoform to an intracellular existence. Transgenic mice expressing human IL-32γ initially exhibit greater inflammation in a model of induced colitis compared with WT but, as the disease progresses, the transgenic mice recover and heal more rapidly than WT (19). It is likely that the splicing event to IL-32β contributes to the clinical improvement.

The increased expression of IL-32γ in RA synovial tissue is consistent with several studies reporting enhanced levels of IL-32 in RA synovial fluid (4) or in RA synovial fibroblasts (20), compared with OA synovial fluid or fibroblasts, respectively. Enhanced expression of TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6, and CXCL8 was observed as expected in RA compared with OA synovial tissue. In OA synovial biopsies a positive association between IL-32γ and IL-32β isoforms was observed, whereas this was absent in RA. One explanation is that in OA there is less inflammatory milieu, allowing for a correlation between IL-32γ and IL-32β. In RA, enhanced expression of proinflammatory cytokines is observed which potentially could result in loss of the IL-32γ/IL-32β correlation. IL-32γ correlated significantly with TNFα and IL-6 in RA synovial tissue, whereas IL-32β did not with either cytokine. In OA synovial tissue, no correlation between IL-32 isoforms and TNFα or IL-6 was observed. We assume that mRNA splicing is responsible for expression of the different IL-32 isoforms, as observed for other proteins such as IL-6-induced α-1-antitrypsin (21) or LPS-induced ICAM-1 isoform expression (22).

HeLa cells transduced with AdIL-32γ showed two protein species, one corresponding to the size of IL-32γ (~27 kDa) and the other to IL-32β (~22 kDa). In addition, PCR with specific primers was performed to discriminate between IL-32γ and IL-32β, resulting in two amplicons. Both were sequenced and corresponded to IL-32γ and IL-32β sequences. Apparently, the majority of IL-32γ mRNA is spliced and translated into IL-32β protein, although some IL-32γ protein was observed. To prevent IL-32γ-into-IL-32β splicing, a single-nucleotide mutation at the donor site was introduced. Transduction of this mutant IL-32γ adenoviral vector (AdIL-32γM) resulted in one IL-32γ–specific amplicon and IL-32γ protein in human HeLa and THP1 cells. This IL-32γ protein derived from AdIL-32γM is more potent in inducing proinflammatory cytokines compared with AdIL-32γ–derived IL-32β protein. Intraarticular injection of AdIL-32γM resulted in enhanced macroscopic knee joint scores, more infiltrating cells in synovia, and enhanced expression of proinflammatory mediators in synovia and patellae compared with AdIL-32γ–injected mice. Moreover, we showed that intracellularly overexpressed IL-32γ can function as a proinflammatory cytokine in the absence of additional stimuli, which is in contrast to IL-32β, which requires a second signal to act as a proinflammatory cytokine (9). This is in line with a previous study in which adenoviral overexpression of IL-32β in human umbilical vein endothelial cells resulted in profound enhancement of ICAM-1, VCAM-1, and E-selectin only after IL-1 stimulation (23). Moreover, it was shown that transgenic IL-32β mice were healthy, viable, and fertile; however, in a cecal-ligation and puncture sepsis model, inflammation and sepsis were exacerbated (23), again showing the requirement for an additional signal for IL-32β. Others demonstrated that the expression and secretion of mouse IL-1β and IL-6 by splenocytes from bone marrow-derived transgenic (BM-hIL-32β) mice was not different compared with the control group (24). In an additional study, the potency of IL-32γ was investigated by stimulating mouse peritoneal macrophages with recombinant IL-32α, IL-32β, IL-32γ, or IL-32δ (25). It was reported that recombinant IL-32γ was most potent in inducing secretion of mouse TNFα and MIP2, confirming our data that IL-32γ is more potent than IL-32β. Although they used LPS-resistant mice, peptidoglycans could still be present in these recombinant protein preparations, capable of synergizing with IL-32 via NOD2 (9, 26), which potentially could influence the results.

It is still not clear whether IL-32 can be secreted and which isoforms are released. In the early days, it was reported that in vitro translation of the NK4 transcript resulted in a shift in protein size which corresponded to the predicted signal peptide sequence length when canine microsomes were added (3). Several studies reported IL-32 release; however, cell death was not thoroughly investigated (1, 2, 5, 7, 24, 27). In our study, IL-32 secretion was not due to cell death because overexpression of spliced or splice-resistant IL-32γ did not result in release of intracellular LDH. Recently, it was proposed that endogenous IL-32 could be released as a membrane-associated protein, because IL-32 accumulated on the cell surface in droplet-like structures and colocalized with endosomal and lysosomal markers (28). Moreover, they observed cell death after prolonged IL-32 induction by IFNγ and TNFα stimulation in intestinal epithelial cells which resulted in IL-32 release. Apparently, IL-32 can be released via non- and classical secretory pathways.

Single-nucleotide mutation of the donor splice site prevented IL-32γ from being spliced into IL-32β, which gave us the opportunity to study the role of intracellular IL-32γ rather than IL-32β. This mutant IL-32γ isoform is more potent than the IL-32γ isoform, which is primarily spliced into IL-32β, as shown in this study. Interestingly, this splice-resistant IL-32γ contains a potential signal peptide sequence for protein secretion which cannot be removed through mRNA splicing and showed that IL-32 secretion was significantly enhanced. When the IL-32γ–specific exon was removed, the amount of released IL-32 was significantly lower compared with the intracellular IL-32 content.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that IL-32γ can be spliced into the IL-32β isoform, in vitro as well as in vivo. Furthermore, we demonstrated that IL-32γ is more potent than IL-32β in inducing proinflammatory mediators, which results in enhanced inflammatory arthritis. Additionally, secretion of IL-32γ was significantly enhanced by TNFα or IL-1β stimulation without cell death being involved. Moreover, splice-resistant IL-32γ was already efficiently secreted without TNFα or IL-1β stimulation. Splicing of IL-32γ into IL-32β suggests a safety switch or negative feedback loop, dampening intracellular presence and secretion of the more potent IL-32γ isoform. By unraveling the function of IL-32γ our current knowledge concerning IL-32 biology increases, which contributes to understanding autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis.

Materials and Methods

RA and OA Synovial Tissue.

Synovial biopsies were isolated from RA or OA patients receiving joint replacement surgery and immediately stored in liquid nitrogen until RNA isolation. Synovial tissue was disrupted by using MagNA Lyser green ceramic beads in a MagNA Lyser apparatus (Roche), and an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) was used to isolate RNA. Reverse-transcriptase enzyme was used to produce cDNA which was used to determine IL-32 isoforms (primer sequences are shown in Table S1). TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6, and CXCL8 expression was corrected for GAPDH, as described by Heinhuis et al. (9).

Cells.

RA FLS and HeLa, and 3T3 cells were cultured in DMEM-Glutamax medium (Gibco-Invitrogen) and THP1 cells in RPMI-1640 (Gibco-Invitrogen), both containing 10% FCS, pyruvate, and penicillin/streptomycin. RA FLS were isolated from synovial tissue as described (9).

Single-Nucleotide Mutation of the GU Donor Splice Site and Construction of AdIL-32γM.

Specific primers containing the mutation were designed and used in conventional PCR using pPro-EX-HTa-IL-32γ as a template. The PCR product was ligated into pScript, and sequence analysis showed the presence of the mutation. Subsequently, pScript-IL-32γM and pShuttle-CMV were digested with BglII/XbaI (New England Biolabs) and the insert was ligated into pShuttle-CMV, resulting in pShuttle-CMV-IL-32γM. The plasmid was sequenced and used to generate AdIL-32γM as described (9).

In Vitro Transduction of AdIL-32γ or AdIL-32γM.

HeLa, THP1, and 3T3 cells were transduced with AdIL-32γ or AdIL-32γM as described by Heinhuis et al. (9). IL-32γ splicing was investigated by conventional PCR using primers as described by Goda et al. (1). Western blot analysis was used to study IL-32γ splicing as described (9) with the following adaptations: Rabbit anti-goat-HRP (Dako) antibody was used as a second antibody and the ECL Plus Western Blotting Detection System (GE Healthcare) was used to visualize proteins. THP1 culture media (48 h posttransduction) were used to measure TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6, and CXCL8 production with Luminex Multi-Analyte technology (Bio-Plex System; Bio-Rad Laboratories).

In Vivo Transduction of AdIL-32γ or AdIL-32γM.

C57BL/6 mice were intraarticularly injected with 1 × 107 plaque-forming units of AdIL-32γ or AdIL-32γM. At 24 h after adenovirus injection, synovial tissues were isolated to investigate splicing by conventional PCR analysis. Moreover, knee joints were isolated and used for histology (H&E staining) as were synovia/patellae for quantitative real-time PCR analysis, 48 h after viral transduction. Mice were kept in filter-top cages with standard diet and water both freely available. Animal studies were approved by our institutional ethics committee.

IL-32 Secretion in RA Synovial Fibroblasts.

RA synovial fibroblasts were transduced with AdIL-32γ or AdIL-32γM as described (9). Twenty-four hours posttransduction, cells were stimulated with 1 ng/mL IL-1β or 10 ng/mL TNFα in serum-free DMEM-Glutamax medium for 24 h. Secretion of IL-32 was measured in culture media by using an IL-32 ELISA; goat anti-IL-32 (AF3040) antibody (R&D Systems) was used as capturing antibody and biotinylated goat anti-IL-32 (BAF3040) antibody (R&D Systems) was used for detection. Recombinant IL-32α (R&D Systems) protein was used for the standard curve. Cell death was investigated with a CytoTox 96 Kit (Promega).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Monique M. Helsen, Birgitte Walgreen, Liduine van den Bersselaar, Elly L. Vitters, Onno J. Arntz, Miranda B. Bennink, and Patrick L. J. M. Zeeuwen for their technical support. B.H. was supported by a research grant from the Dutch Arthritis Association (06-1-301) and M.G.N. was supported by a Vici grant from The Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research.

Footnotes

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1016005108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Goda C, et al. Involvement of IL-32 in activation-induced cell death in T cells. Int Immunol. 2006;18:233–240. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim SH, Han SY, Azam T, Yoon DY, Dinarello CA. Interleukin-32: A cytokine and inducer of TNFα. Immunity. 2005;22:131–142. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dahl CA, Schall RP, He HL, Cairns JS. Identification of a novel gene expressed in activated natural killer cells and T cells. J Immunol. 1992;148:597–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mun SH, et al. Tumor necrosis factor α-induced interleukin-32 is positively regulated via the Syk/protein kinase Cδ/JNK pathway in rheumatoid synovial fibroblasts. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:678–685. doi: 10.1002/art.24299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shioya M, et al. Epithelial overexpression of interleukin-32α in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;149:480–486. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03439.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meyer N, et al. IL-32 is expressed by human primary keratinocytes and modulates keratinocyte apoptosis in atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:858–865, e10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marcondes AM, et al. Dysregulation of IL-32 in myelodysplastic syndrome and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia modulates apoptosis and impairs NK function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:2865–2870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712391105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Netea MG, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis induces interleukin-32 production through a caspase- 1/IL-18/interferon-γ-dependent mechanism. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e277. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heinhuis B, et al. IL-32γ and Streptococcus pyogenes cell wall fragments synergise for IL-1-dependent destructive arthritis via upregulation of TLR-2 and NOD2. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1866–1872. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.127399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bai X, et al. IL-32 is a host protective cytokine against Mycobacterium tuberculosis in differentiated THP-1 human macrophages. J Immunol. 2010;184:3830–3840. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heinhuis B, et al. December 27 Tumour necrosis factor α-driven IL-32 expression in rheumatoid arthritis synovial tissue amplifies an inflammatory cascade. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010 doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.139196. 10.1136/ard.2010.139196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hong J, et al. Suppressing IL-32 in monocytes impairs the induction of the proinflammatory cytokines TNFα and IL-1β. Cytokine. 2010;49:171–176. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nold-Petry CA, et al. IL-32-dependent effects of IL-1β on endothelial cell functions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:3883–3888. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813334106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nold MF, et al. Endogenous IL-32 controls cytokine and HIV-1 production. J Immunol. 2008;181:557–565. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joosten LA, et al. IL-32, a proinflammatory cytokine in rheumatoid arthritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:3298–3303. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511233103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wahl MC, Will CL, Lührmann R. The spliceosome: Design principles of a dynamic RNP machine. Cell. 2009;136:701–718. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montell C, Fisher EF, Caruthers MH, Berk AJ. Control of adenovirus E1B mRNA synthesis by a shift in the activities of RNA splice sites. Mol Cell Biol. 1984;4:966–972. doi: 10.1128/mcb.4.5.966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bendtsen JD, Nielsen H, von Heijne G, Brunak S. Improved prediction of signal peptides: SignalP 3.0. J Mol Biol. 2004;340:783–795. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choi J, et al. Paradoxical effects of constitutive human IL-32γ in transgenic mice during experimental colitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:21082–21086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015418107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cagnard N, et al. Interleukin-32, CCL2, PF4F1 and GFD10 are the only cytokine/chemokine genes differentially expressed by in vitro cultured rheumatoid and osteoarthritis fibroblast-like synoviocytes. Eur Cytokine Netw. 2005;16:289–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kalsheker N, Swanson T. Exclusion of an exon in monocyte α-1-antitrypsin mRNA after stimulation of U937 cells by interleukin-6. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;172:1116–1121. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)91562-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mizgerd JP, Spieker MR, Lupa MM. Exon truncation by alternative splicing of murine ICAM-1. Physiol Genomics. 2002;12:47–51. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00073.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kobayashi H, et al. Interleukin-32β propagates vascular inflammation and exacerbates sepsis in a mouse model. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9458. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shoda H, et al. Interactions between IL-32 and tumor necrosis factor α contribute to the exacerbation of immune-inflammatory diseases. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8:R166. doi: 10.1186/ar2074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choi JD, et al. Identification of the most active interleukin-32 isoform. Immunology. 2009;126:535–542. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.02917.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Netea MG, et al. IL-32 synergizes with nucleotide oligomerization domain (NOD) 1 and NOD2 ligands for IL-1β and IL-6 production through a caspase 1-dependent mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:16309–16314. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508237102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alsaleh G, et al. Innate immunity triggers IL-32 expression by fibroblast-like synoviocytes in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:R135. doi: 10.1186/ar3073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hasegawa H, Thomas HJ, Schooley K, Born TL. Native IL-32 is released from intestinal epithelial cells via a non-classical secretory pathway as a membrane-associated protein. Cytokine. 2011;53:74–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.