Abstract

In this study we sought to better understand the role of the glycoprotein quality control machinery in the assembly of MHC class I molecules with high-affinity peptides. The lectin-like chaperone calreticulin (CRT) and the thiol oxidoreductase ERp57 participate in the final step of this process as part of the peptide-loading complex (PLC). We provide evidence for an MHC class I/CRT intermediate before PLC engagement and examine the nature of that chaperone interaction in detail. To investigate the mechanism of peptide loading and roles of individual components, we reconstituted a PLC subcomplex, excluding the Transporter Associated with Antigen Processing, from purified, recombinant proteins. ERp57 disulfide linked to the class I-specific chaperone tapasin and CRT were the minimal PLC components required for MHC class I association and peptide loading. Mutations disrupting the interaction of CRT with ERp57 or the class I glycan completely eliminated PLC activity in vitro. By using the purified system, we also provide direct evidence for a role for UDP-glucose:glycoprotein glucosyltransferase 1 in MHC class I assembly. The recombinant Drosophila enzyme reglucosylated MHC class I molecules associated with suboptimal ligands and allowed PLC reengagement and high-affinity peptide exchange. Collectively, the data indicate that CRT in the PLC enhances weak tapasin/class I interactions in a manner that is glycan-dependent and regulated by UDP-glucose:glycoprotein glucosyltransferase 1.

Keywords: protein folding, peptide editing

The assembly of MHC class I molecules is a critical step in the generation of immune responses against viruses and tumors, and also a highly specialized example of glycoprotein folding in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). MHC class I molecules display peptides representative of the cellular protein content to CD8+ T cells, and the stable association of the class I heavy chain (HC), β2-microglobulin (β2m), and a high-affinity 8- to 10-aa foreign peptide is essential for T-cell activation. As a result, a specialized adaptation of the glycoprotein folding machinery has evolved to ensure the loading of MHC class I molecules with optimal peptide ligands. Following HC assembly with β2m, the empty heterodimer rapidly and stably associates with the peptide-loading complex (PLC), which facilitates the final peptide-binding step (1). The functions of the MHC class I-specific components of the PLC are well defined. Tapasin interacts with both the HC/β2m dimer as well as Transporter Associated with Antigen Processing (TAP), thereby retaining the empty complexes in proximity to the peptide supply. More importantly, tapasin association stabilizes class I molecules and promotes loading with high-affinity peptides. However, the optimal activity of tapasin requires the presence of calreticulin (CRT) and ERp57, two ER proteins involved in general glycoprotein folding, in the PLC (2–4).

The ER glycoprotein quality control machinery is a complex system that uses the structural state of N-linked glycans to dictate the fate of newly synthesized proteins (1, 5, 6). Initially, a Glc3Man9GlcNAc2 glycan is transferred to polypeptides during translocation and subsequently trimmed by glucosidase I (GlsI) and glucosidase II (GlsII) to a monoglucosylated glycan, which is the substrate for the lectin-like chaperones CRT and calnexin (CNX). Both chaperones have a globular lectin-binding domain and an extended arm known as the P-domain that binds specifically to ERp57, a member of the protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) family. ERp57 has a four-domain architecture of abb′a′ in which the first and last contain a CXXC active site. CRT and CNX work in concert with ERp57 to promote proper folding and disulfide bond formation of newly synthesized glycoproteins. Upon release of the glycoprotein from CRT or CNX, its glycan is deglucosylated by GlsII and is no longer a substrate for the chaperones. If the glycoprotein has not yet acquired its native structure, the enzyme UDP-glucose:glycoprotein glucosyltransferase 1 (UGT1), a folding sensor, reglucosylates it to reinitiate an interaction with CRT/CNX/ERp57. However, a properly folded glycoprotein is not a substrate for UGT1 and can be exported to the Golgi.

Important roles for CRT and ERp57 in MHC class I assembly and PLC function have been established from studies of KO mice and deficient cell lines (2, 3). In the absence of either component, the cell surface expression and stability of MHC class I molecules are reduced. The cause of the defect has been elucidated for ERp57-deficient cells. Tapasin forms a stable disulfide-linked heterodimer with ERp57, which is required for the structural stability and optimal function of the PLC (4, 7, 8). The disulfide linkage is between Cys95 of tapasin and Cys57 of the ERp57 a domain active site (9), and the dimer is further stabilized by noncovalent interactions between tapasin and the a′ domain active site (10). CRT interacts with both the HC glycan and the b′ domain of ERp57, but the nature and importance of these interactions within the PLC are controversial, particularly in regard to glycan-independent substrate binding (11–15). Finally, the potential roles of GlsII and UGT1 in regulating the CRT/class I interaction in the PLC have yet to be addressed.

By using a variety of biochemical approaches, including reconstitution of a PLC subcomplex entirely from purified components, we have investigated the role of ER quality control components in MHC class I peptide loading. We demonstrate the CRT is recruited to and released from the PLC along with class I molecules. By examination of the CRT/HC stoichiometry and the HC glycosylation state, we found no evidence for glycan-independent interactions within the PLC. Consistent with this, in vitro reconstitution of the PLC required the lectin- and ERp57-binding activities of CRT and could be enhanced by UGT1-mediated glucosylation. Taken together, the data support important roles for CRT and the quality control machinery in regulating class I peptide loading by the PLC.

Results and Discussion

CRT Associates with MHC Class I HC/β2m Heterodimers Before Incorporation into the PLC.

Work from our laboratory has demonstrated that the tapasin/ERp57 conjugate associates with TAP in cells lacking expression of MHC class I HC or β2m (8, 16), suggesting that this core serves as a scaffold onto which the remaining PLC components assemble. Furthermore, the GlsII inhibitor castanospermine (CST) prevents the interaction of MHC class I molecules with the PLC in intact cells (17) and a cell-free assay (4). This suggests that CRT escorts HC/β2m dimers to tapasin, but this has not been demonstrated experimentally. Initially, we sought to identify PLC-independent complexes of HLA-B8 with CRT by using tapasin-negative .220.B8 cells. We prepared extracts from radiolabeled cells in the absence or presence of DSP, a chemical cross-linker, and performed sequential immunoprecipitations to detect CRT-associated proteins. As shown in Fig. 1A, a CRT/HC interaction was observed in untreated extracts and stabilized by DSP. β2m, which is not glycosylated, also coimmunoprecipitated with CRT from cross-linked cell extracts, demonstrating the presence of CRT-associated HC/β2m heterodimers (Fig. 1A). To determine whether this complex exists in the presence of the PLC, we performed tapasin immunodepletions from radiolabeled .220.B8.Tpsn cells. As shown in Fig. 1B, a fraction of HLA-B8 molecules were associated with CRT after the complete removal of tapasin. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that CRT/MHC class I complexes are an intermediate in the MHC class I assembly pathway.

Fig. 1.

HC/β2m heterodimers associate with CRT independently of the PLC. (A) .220.B8 cells were labeled for 30 min and lysed with or without 0.3 mM DSP. Immunoprecipitations were performed with tapasin (R.gp48C), CRT, or β2m Abs, followed by reimmunoprecipitation with 3B10.7 (HC) or β2m Abs. (B) Radiolabeled .220.B8.Tpsn cells (60-min pulse) were lysed and subjected to four immunodepletion steps with PaSta1-coupled beads, followed by immunoprecipitation with tapasin (R.gp48C), CRT, or ERp57 Abs. The associated HCs were reimmunoprecipitated with 3B10.7 and analyzed by SDS/PAGE. (C) Cell extracts were prepared from .220.B8 cells in lysis buffer containing the indicated concentrations of recombinant CRT. Samples were then incubated with or without 0.35 μM C60A conjugate for 15 min at RT followed by immunoprecipitation with PaSta1-coupled beads. The bound proteins were eluted and analyzed by immunoblotting with CRT and 3B10.7 Abs.

To examine whether CRT binding to MHC class I molecules is required to initiate interactions with the remaining PLC components, we adapted a cell-free assay for PLC activity (4, 10). This system reconstitutes PLC subcomplexes lacking TAP by the addition of recombinant soluble tapasin (sTpsn)/ERp57 conjugate to .220.B8 cell extracts, which are a crude source of CRT and empty class I molecules. We postulated that CRT/HC/β2m complexes (Fig. 1 A and B) are the subset of molecules recruited to the conjugate with this assay. However, a significant portion of these complexes likely dissociate during the extract preparation given the relatively low affinity of CRT for glycosylated class I HC (Kd of ~1 μM) (14) and the rapid rate of dissociation determined from kinetic experiments (t1/2 of ~10 min at 4 °C; Fig. S1). Consistent with our projections, the addition of excess recombinant CRT to the lysis buffer enhanced HC association with the conjugate (Fig. 1C), presumably because of preservation of CRT/HC/β2m complexes in the assembly pathway. In agreement, Del Cid et al. (11) have proposed a recruiting role for CRT in the PLC based on reduced class I association with the PLC in CRT-deficient cells. However, that interpretation is complicated by the analyses being performed at steady state, i.e., the effect of CRT on the class I /tapasin interaction may be a result of PLC stabilization. Although the two effects cannot be discriminated biochemically, CRT may serve an important role for both. The discovery that an HC/β2m/CRT assembly intermediate exists provides the most direct evidence for CRT-mediated recruitment (Fig. 1 A and B), whereas the coupling of known interactions between PLC components is sufficient to support CRT-mediated stabilization of existing class I/ tapasin interactions (1).

Analysis of the MHC Class I/CRT Interaction in the PLC.

To better understand the functions of CRT in class I assembly, we evaluated the stoichiometry and mode of interaction between CRT and the class I HC in the PLC. The initial assessment of the CRT/HC ratio (18) was complicated by the subsequent discovery of ERp57 in the PLC, so we used a different approach that involved quantitative immunoblotting. PLCs were isolated by immunoprecipitation from .220.B8.Tpsn cells and analyzed in parallel with purified CRT and class I HC as standards so the relative amounts could be determined. A representative blot is shown in Fig. 2A and the average ratio calculated from five independent experiments was 1.08 ± 0.19 CRT to 1.00 HC molecules. Thus, equimolar amounts of MHC class I HC and CRT are present in the PLC. In further support of this stoichiometry, we performed tapasin immunoprecipitations from CRT-depleted .220.B8.Tpsn extracts and found that there are essentially no CRT-deficient PLCs (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Analysis of the CRT/HC interaction in the PLC. (A) TAP immunoprecipitations were performed from the indicated number of .220.B8.Tpsn cells and analyzed by SDS/PAGE along with recombinant class I HC and CRT standards. Quantitative immunoblotting was performed with 3B10.7 or CRT Abs, and the standard curves are shown in Fig. S2. Two sample sets were processed and averaged per experiment, but only one is shown. (B) Extracts from radiolabeled .220.B8.Tpsn cells (60-min pulse) were subjected to four CRT immunodepletion steps. Immunoprecipitations were then performed with control, PaSta1, or CRT Abs and analyzed by SDS/PAGE. (C) Schematic of the JBM assay. (D) .220.B8.Tpsn cells were pulse-labeled for 30 min and chased for as long as 90 min. Primary immunoprecipitations were performed with 148.3 Ab-coupled beads and secondary immunoprecipitations were performed with 3B10.7 or R.gp48C. Digests were then performed with JBM or EndoH and samples were analyzed by SDS/PAGE. Note that, after JBM digestion, the migration of glucosylated species is more similar to that of the undigested band (red asterisk), whereas the migration of deglucosylated species is more similar to that of the EndoH-treated band (blue asterisk). (E) .220.B8.tpsn cells were labeled for 60 min and sequential immunoprecipitation/pull-down assays were performed with 3B10.7 Ab, GST, or CRT-GST immobilized on beads followed by 3B.10.7 (Upper). The total amount of HC recovered was calculated from two sequential 3B10.7 immunoprecipitations or from three CRT-GST pull-down steps (Lower).

Monoglucosylated glycans are required for CRT binding to the class I HC in vitro (14), which presents an apparent discrepancy between the stoichiometry (Fig. 2A) and the mixed glycan structures of PLC-associated HC previously reported (19). We therefore reevaluated the glycosylation state of class I in the PLC with the use of two assays. The first used jack-bean mannosidase (JBM), an exomannosidase that trims nonglucosylated glycans more extensively than those with a terminal glucose residue (Fig. 2C), which can then be detected as subtle shifts by SDS/PAGE (20). We performed a pulse-chase experiment with .220.B8.Tpsn cells followed by JBM or EndoH digestion of PLC-associated tapasin or class I HC. As shown in Fig. 2D, the tapasin glycan contains terminal glucose residues shortly after synthesis (0 min chase), which are subsequently trimmed by the 90-min chase point, consistent with its maturation to the native state. In contrast, the JBM-treated class I HC band did not shift during the chase; thus, its glycan is not trimmed while it is associated with the PLC. To more accurately quantify the fraction of PLC-associated class I HC with monoglucosylated glycans, our second assay used pull-downs with CRT-GST fusion protein immobilized on glutathione beads. As shown in Fig. S2, the binding of class I HC to the CRT-GST beads was completely eliminated by treatment with GlsII and is therefore glycan-dependent. Compared with the total amount of PLC-associated class I HC, determined by 3B10.7 immunoprecipitations, we found that 97% of the total could be recovered from sequential CRT-GST pull-downs (Fig. 2E). We therefore conclude that virtually all MHC class I molecules in the PLC are monoglucosylated and bound to CRT via the N-linked glycan.

CRT and ERp57 Provide Structural Roles in Soluble PLCs Reconstituted from Purified Components.

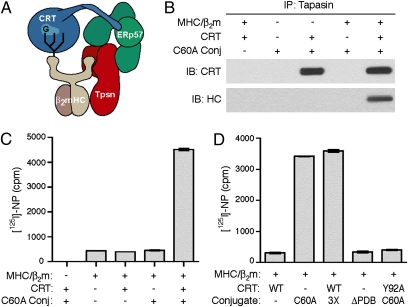

Conflicting data regarding the mechanism of CRT and ERp57 activity in the PLC have been reported in studies in intact cells (11, 12, 15). We sought to address these discrepancies using an in vitro assay for PLC activity. Since the discovery of tapasin in 1996, two experimental systems have been devised to address its function and both have limitations. Chen and Bouvier used recombinant soluble MHC class I complexes and tapasin purified from Escherichia coli (21), but excluding CRT and ERp57 from the system necessitated the addition of leucine zippers to tapasin and class I HCs to induce dimerization. In contrast, we developed a cell-free assay that successfully reconstituted a subcomplex of the PLC (4) but used cell extracts, meaning that a role for unidentified components could not be eliminated. For these reasons, we continued our endeavor to reconstitute a soluble subcomplex of the PLC from purified components (Fig. 3A). This has been a considerable challenge because of the multiple components and specialized interactions within the PLC (1).

Fig. 3.

In vitro reconstitution of a soluble subcomplex of the PLC. (A) Schematic of the soluble PLC subcomplex. (B) Recombinant proteins (0.5 μM each) were incubated at RT for 1 h and immunoprecipitations were performed with PaSta1-coupled beads. The tapasin-associated CRT and HC were detected by immunoblotting. (C and D) The indicated recombinant proteins—CRT or Y92A, a CRT glycan-binding mutant; disulfide-linked conjugates of sTpn with C60A, an ERp57 mutant that traps tapasin, with 3X, a redox-inactive ERp57 mutant that traps tapasin, or with ΔPDB, an ERp57 mutant that traps tapasin but does not interact with CRT—were incubated at a final concentration of 0.4 μM each for 15 min at RT with [125I]-NP. Peptide loading was measured by w6/32 immunoprecipitation and γ-counting.

The production of the appropriate PLC substrate (empty MHC class I complexes with monoglucosylated N-linked glycans) has been the most problematic. We previously described the expression of soluble HLA-B8 bearing such a glycan in a Saccharomyces cerevisiae glycosylation mutant (14), but the refolding yields without high-affinity peptides were insufficient for extensive structural or functional analyses. Consequently, we tested a different strategy that involved baculovirus expression, as the class I HC assembles with β2m in insect cells but the complexes are largely devoid of peptides because of the absence of tapasin and TAP (22, 23). Coexpression of the luminal domain of HLA-B8 with human β2m in Sf21 cells resulted in the formation of heterodimers that were completely retained in the ER as determined by EndoH digestion (Fig. S3A). We therefore postulated that a significant fraction of the HC molecules might possess the correct oligosaccharide structure for CRT binding. Analysis of samples from multiple infections by CRT-GST pull-downs indicated that approximately 20% of the class I molecules produced in Sf21 cells were monoglucosylated (Fig. S3B). HLA-B8 molecules expressed in Sf21 cells were unstable, however, as a result of the absence of bound peptides. To prevent dissociation of HC/β2m complexes, extraction and purification were carried out in the presence of an intermediate-affinity peptide, the previously described RAL variant of the antigenic peptide EBNA3(339-447) (4). The RAL ligand binds and stabilizes HLA-B8 molecules (4), but can be displaced by the PLC in vitro (Fig. S4).

Our strategy was to assemble the PLC subcomplex in vitro from purified CRT, sTpsn/ERp57 conjugate, and HC/β2m/RAL complexes (Fig. S3C). First, we incubated the recombinant proteins in various combinations and assessed PLC reconstitution by the coimmunoprecipitation of CRT and class I HC with tapasin (Fig. 3B). As expected, CRT bound to the conjugate at these concentrations as a result of its specific interaction with the ERp57 b′ domain (Kd of 0.55 μM) (11). MHC class I complexes did not interact with sTpsn/ERp57 alone, but did so efficiently in the presence of CRT, demonstrating that PLC subcomplexes were generated (Fig. 3B). These observations explain the need for leucine zippers to force the dimerization of class I with tapasin in the absence of an HC glycan, CRT, and ERp57 (21). We next tested the reconstituted system for peptide loading activity by using the high-affinity NP(380-387L) ligand specific for HLA-B8 (4). We incubated HC/β2m/RAL complexes with purified PLC components and [125I]-NP and then determined radiolabeled peptide loading by immunoprecipitations with the mAb w6/32, which binds HC/β2m/peptide complexes (Fig. 3C). HC/β2m/RAL complexes were capable of a low level of [125I]-NP exchange that was not affected by the presence of CRT or the sTpsn/ERp57 conjugate alone. However, when both CRT and the conjugate were present, a 10-fold increase in high-affinity peptide binding was observed, which directly demonstrates catalysis of peptide exchange by the PLC. Some laboratories have reported that PDI is a member of the PLC and affects peptide loading (24), but these findings have been contentious (1). Recombinant human PDI was not required for PLC activity, nor did it enhance peptide loading in this assay. These experiments demonstrate successful reconstitution of the PLC from purified proteins and establish MHC class I HC, β2m, CRT, tapasin, and ERp57 as the only components essential for peptide exchange in vitro.

To directly test the roles of ERp57 and CRT in the PLC, we generated several mutants and tested their ability to support peptide loading. The 3X mutant of ERp57 (C60A/C406A/C409A) allows covalent trapping of tapasin, but is redox-inactive (7). The ΔPDB ERp57 construct (K214A/K274A/K284A) is a combination of the individual point mutations that most profoundly disrupt CNX/CRT P-domain binding (25). Both ERp57 mutants efficiently formed disulfide-linked heterodimers when coexpressed with sTpsn and were purified. We also produced a Y92A mutant of human CRT based on the analogous mutations of rabbit and mouse CRT that disrupt glycan binding (11, 26). Consistent with the crystal structure of the sTpsn/ERp57 conjugate (10) and the characterization of the 3X mutant in ERp57-deficient cells (7, 15), inactivation of ERp57 redox activity did not impair the function of the PLC (Fig. 4D). However, when either Y92A CRT or the sTpsn/ΔPDB ERp57 conjugate was used, no tapasin-mediated peptide loading was observed. Thus, the CRT/glycan and CRT/ERp57 interactions are required for PLC function in vitro. Contradictory results have been reported on this issue with the use of mutants expressed in CRT- or ERp57-deficient mouse cells (11, 12, 15). With an independent experimental system involving soluble components, our results agree with the findings of Del Cid et al. (11).

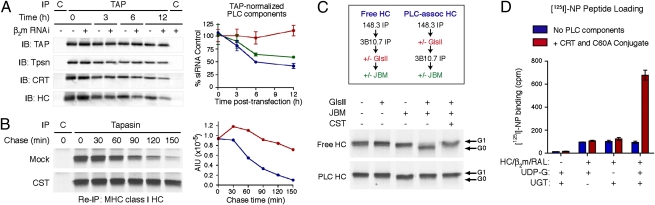

Fig. 4.

Reglucosylation of MHC class I molecules by UGT promotes reengagement with the PLC. (A) Control or β2m-specific siRNA oligos were introduced into .220.B8.Tpsn cells and samples were harvested at 0, 12, and 24 h after nucleofection. PLC components were detected by immunoprecipitation with 148.3 Ab and quantitative immunoblotting (Left). Amounts of PLC-associated CRT, tapasin, and class I HC were calculated and normalized to TAP (Right). (B) .220.B8.Tpsn cells were labeled with [35S]-methionine for 30 min and chased for 0 to 120 min with or without 2.5 mM CST. Immunoprecipitations were performed with control or 148.3 Abs followed by elution and reimmunoprecipitation with 3B10.7 mAb (Left). Right: PhosphorImager quantification. (C) .220.B8.Tpsn cells were labeled for 60 min and then subjected to immunoprecipitations and enzymatic digestions as shown in the flowchart (Upper). (D) Purified recombinant MHC class I complexes depleted of those with monoglucosylated glycans were incubated with or without UGT and UDP-glucose. Subsequently, [125I]-NP loading was measured in the absence or presence of the remaining PLC components (0.4 μM C60A conjugate and CRT).

CRT Exits the PLC with MHC Class I, but Release Is Not Induced by GlsII.

The events that govern MHC class I peptide loading and dissociation of the PLC are poorly understood. Based on our finding that empty MHC class I heterodimers and CRT are corecruited to the core complex of tapasin/ERp57/TAP (Fig. 1), we postulated that they are also simultaneously released from the PLC upon peptide binding. To test this hypothesis, we used siRNA to knock down β2m, preventing the association of newly synthesized MHC class I molecules with tapasin, and then followed the fate of the preexisting PLC components. Transient transfections of .220.B8.Tpsn cells were performed with control or β2m-specific siRNA, and samples were harvested for as long a 12 h (Fig. 4A). Analysis by coimmunoprecipitation and blotting showed that the amount of TAP-associated tapasin/ERp57 conjugate remained constant over the 12-h period after transfection, whereas the CRT and class I HC levels decreased in parallel. This suggests that CRT is released from the core PLC components following peptide loading, and agrees with the observation that CRT does not associate with TAP in the absence of MHC class I heterodimers (16).

Because CRT and MHC class I molecules are released simultaneously from TAP (Fig. 4A) in a manner that is apparently affected by GlsII inhibition (27), we considered the possibility that trimming of the HC glycan triggers dissociation of the PLC. To address this question in greater detail, we labeled .220.B8.Tpsn cells and followed the kinetics of HC release from TAP in the absence or presence of CST. We found that the interaction of class I molecules with the PLC was dramatically prolonged when GlsII activity was inhibited during the chase (Fig. 4B). This suggested that glycan trimming is required for release of class I from the PLC. To further investigate this, we compared the ability of purified GlsII to trim the monoglucosylated glycan of PLC-associated and free HC. TAP immunoprecipitations were performed from radiolabeled .220.B8.Tpsn cells, samples were incubated with GlsII before or after reimmunoprecipitation of the class I HC, and then JBM digestions were performed as a readout. As shown in Fig. 4C, the glycans of free HCs, but not PLC-associated HCs, were accessible to GlsII (compare lanes 3 and 4 in Fig. 4C). Glycan trimming must therefore occur after release of CRT or MHC class I from the PLC. This finding would appear to disagree with the conclusion implied by the data in Fig. 4B and ref. 27, i.e., that glucose removal is required for dissociation. To reconcile these findings, we suggest that the prolonged interaction of MHC class I molecules with the PLC is maintained by a dynamic equilibrium that results from multiple rounds of release and reengagement of the class I glycan provided it is monoglucosylated.

This hypothesis presents interesting implications for the mechanism of peptide optimization, including a potential role for UGT in promoting repeated peptide loading events until the highest-affinity ligand is acquired. In support of this conclusion, we have found and reported in a companion paper in PNAS that the assembly of MHC class I molecules is impaired in UGT1-deficient murine fibroblasts (28). To further these observations, we adapted our in vitro assay to directly demonstrate that MHC class I complexes with intermediate-affinity peptides are substrates for reglucosylation by using the Drosophila homologue (i.e., UGT) of human UGT1. Purified HC/β2m/RAL preparations were depleted of monoglucosylated species with CRT-GST beads, incubated with or without recombinant UGT and UDP-glucose, and then subsequently tested for PLC-mediated loading of [125I]-NP. As shown in Fig. 4D, no peptide exchange was observed following the CRT-GST depletion, indicating that all HC-bearing monoglucosylated glycans had been removed. However, peptide exchange was observed when the depleted HC/β2m/RAL complexes were enzymatically reglucosylated by using UGT and UDP-glucose. Thus, as demonstrated directly in the companion paper (28), UGT recognizes MHC class I molecules loaded with suboptimal ligands, promoting peptide optimization by the PLC.

Summary.

Taken together, the results from the present study support a critical role for the lectin-like chaperone activity of CRT in the PLC. Although it has been speculated that CRT escorts class I molecules to tapasin and TAP (11, 17), we provide experimental evidence for the existence of this intermediate. In addition to a recruiting function, CRT stabilizes class I molecules within the PLC via an equimolar, glycan-dependent interaction. By coupling interactions with the HC glycan and ERp57, the presence of CRT greatly enhances the otherwise weak affinity between MHC class I molecules and the tapasin/ERp57 heterodimer. The glucosylation state of the class I molecule therefore dictates its engagement with the PLC, permitting a role for UGT1 in the optimization of the peptide repertoire as described in another study in PNAS (28).

For more than a decade, the analysis of the PLC and its components has been largely restricted to the biochemical characterization of cell lines. Although such studies have been highly informative, they can provide only an indirect analysis of PLC function. The development of an in vitro assay for PLC function now permits precise analysis of the mechanisms of peptide loading. This objective has been hampered for many years by the inability to produce the appropriate class I substrate (4, 14, 21). By using soluble HLA-B8 expressed with β2m in insect cells, we were able to reconstitute a soluble subcomplex of the PLC with purified CRT and sTpsn/ERp57. In addition to establishing the minimal components required for function, we unambiguously established a role for the CRT/ERp57 interaction and for UGT1 in peptide exchange and optimization. The reconstituted system finally opens the door for the detailed mechanistic analysis of the core PLC components, as well as possible accessory roles of other ER factors such as peptidases in MHC class I peptide loading.

Materials and Methods

Plasmids.

A baculovirus construct was generated for the coexpression of soluble HLA-B*0801 (AA-24–273) with human β2m. Inserts were amplified by using PCR and cloned into pFastBac Dual (Invitrogen). The mature domain of human CRT with a C-terminal 6× His tag was cloned into pET15b (Novagen). The QuikChange mutagenesis kit (Agilent) was used to generate Y92A CRT in pET15b and the two ERp57 mutations (ΔPDB and 3X) in pFastBac Dual with sTpsn.

Cell Lines and Reagents.

The human .220.B8 cell line and its WT tapasin transfectant (.220.B8.Tpsn) have been described previously (18). The antibodies used were 3B10.7 (free class I HC), w6/32 (class I conformation-specific), PaSta1 (tapasin), R.gp48C (tapasin), R.ERp57 (full length ERp57), and CRT (4, 8). The peptides NP(380-387L) and EBNA3(339-447) RAL were synthesized by GenScript and iodinated as described (4).

Immunoprecipitations and Immunoblotting.

Cells (5 × 106 per sample unless indicated otherwise) were lysed in 1% digitonin (EMD Biosciences) in 150 mM NaCl, 25 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.4, 1 mM CaCl2 (TBS-C) with complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor tablets (Roche) and 10 mM methyl methanethiosulfonate (Pierce). Following a 30-min preclear, immunoprecipitations were performed for 1 h at 4 °C with the indicated Abs and protein G Sepharose or directly conjugated beads. Normal rabbit serum was used as a control Ab. After three washes with 0.1% digitonin in TBS-C, proteins were eluted in sample buffer or in 0.5% SDS for subsequent reimmunoprecipitation after dilution into 1% Triton in TBS-C. The following steps were used when indicated. Pulse/chase experiments were performed as described (14). Immunodepletions were executed with four 45-min incubations with Ab-coupled beads. Enzymatic digests were performed overnight at 37 °C with EndoH (NEB) or JBM (Sigma). The standard blotting procedures and detection with ECL (Pierce) were performed as described (4, 7). For quantitative immunoblots, CRT and soluble HLA-B8 purified from E. coli (14) were used as standards, and proteins were detected with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary Ab (Jackson Labs) and ECF substrate (GE Healthcare). PhosphorImager and FluorImager quantifications were performed by using the Storm860 system and ImageQuant software (GE Healthcare).

β2m siRNA.

Cells (.220.B8.Tpsn) were transfected with β2m-specific or control siRNA oligos by using the Amaxa Nucleofector (Lonza) with program V01 in five 100-μL aliquots. Briefly, 20 × 106 cells were resuspended in 500 μL of Solution R with 250 pmol control (GCUUCAACAGCAGGCACUC) or 125 pmol each of β2m-specific (GAGUAUGCCUGCCGUGUGAUU and GCAAGGACUGGUCUUUCUAUU) siRNA oligos (Dharmacon). Samples were harvested at the indicated times and frozen for subsequent analysis. Immunoprecipitations and blotting were performed as described earlier, and the data were normalized to TAP levels before calculating the percentage of control siRNA-treated value.

Protein Purification.

All CRT and sTpsn/ERp57 recombinant proteins were purified by using the established protocols (4, 14). Unless indicated otherwise, the C60A conjugate (WT sTpsn disulfide-linked to C60A ERp57), which is fully active (4), was used for experiments. Free class I HCs (soluble HLA-B8) were purified from E. coli inclusion bodies (14), and HC/β2m/RAL complexes were isolated from Sf21 cells by using the following protocol. Frozen cell pellets were lysed in 1% Triton in 50 mM sodium phosphate, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM methyl methanethiosulfonate, with Complete EDTA-free tablets (Roche). The complexes were purified by using Talon beads (Clontech) according to the manufacturer's instructions and then by MonoQ chromatography with a linear gradient of 0 to 500 mM NaCl in 25 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8. To limit dissociation of HC/β2m dimers, 25 to 50 μM RAL peptide was included in the lysis, purification, and storage buffers. Pig liver GlsII was purified as described (6). Drosophila UGT produced in Sf9 cells was a gift of Karin Reinisch (Yale University, New Haven, CT).

Peptide Loading Assay.

Purified components (0.4 μM) were incubated in 50 μL TBS-C with 0.8 μM [125I]-NP(380-387L) for 15 min at room temperature (RT). (The residual RAL concentration from the purified MHC was 5 μM.) Next, 750 μL of 0.1% Triton in TBS-C with 50 μM cold NP peptide was added and w6/32 immunoprecipitations were performed. After three washes with 0.1% Triton in TBS-C, the amount of peptide bound on the beads was measured by using a Wallac 1420 counter (Perkin-Elmer). Reactions were performed in duplicate and the baseline values (i.e., no recombinant protein) were subtracted as background from all data sets. For reglucosylation experiments, the HC/β2m/RAL preparations were depleted of monoglucosylated complexes by using CRT-GST beads and then incubated with 1 μM UGT and 100 μM UDP-glucose (Sigma) in 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM CaCl2, 25 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8, for 1 h at 30 °C before the peptide loading assay.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Wei Zhang for helpful discussions, Karin Reinisch for valuable reagents, and Nancy Dometios for manuscript preparation. This work was supported by The Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1102524108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Wearsch PA, Cresswell P. The quality control of MHC class I peptide loading. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:624–631. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gao B, et al. Assembly and a ntigen-presenting function of MHC class I molecules in cells lacking the ER chaperone calreticulin. Immunity. 2002;16:99–109. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00260-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garbi N, Tanaka S, Momburg F, Hämmerling GJ. Impaired assembly of the major histocompatibility complex class I peptide-loading complex in mice deficient in the oxidoreductase ERp57. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:93–102. doi: 10.1038/ni1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wearsch PA, Cresswell P. Selective loading of high-affinity peptides onto major histocompatibility complex class I molecules by the tapasin-ERp57 heterodimer. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:873–881. doi: 10.1038/ni1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Helenius A, Aebi M. Roles of N-linked glycans in the endoplasmic reticulum. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:1019–1049. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D'Alessio C, Caramelo JJ, Parodi AJ. UDP-GlC:glycoprotein glucosyltransferase-glucosidase II, the ying-yang of the ER quality control. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2010;21:491–499. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2009.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peaper DR, Cresswell P. The redox activity of ERp57 is not essential for its functions in MHC class I peptide loading. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:10477–10482. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805044105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peaper DR, Wearsch PA, Cresswell P. Tapasin and ERp57 form a stable disulfide-linked dimer within the MHC class I peptide-loading complex. EMBO J. 2005;24:3613–3623. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dick TP, Bangia N, Peaper DR, Cresswell P. Disulfide bond isomerization and the assembly of MHC class I-peptide complexes. Immunity. 2002;16:87–98. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00263-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dong G, Wearsch PA, Peaper DR, Cresswell P, Reinisch KM. Insights into MHC class I peptide loading from the structure of the tapasin-ERp57 thiol oxidoreductase heterodimer. Immunity. 2009;30:21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Del Cid N, et al. Modes of calreticulin recruitment to the major histocompatibility complex class I assembly pathway. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:4520–4535. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.085407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ireland BS, Brockmeier U, Howe CM, Elliott T, Williams DB. Lectin-deficient calreticulin retains full functionality as a chaperone for class I histocompatibility molecules. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:2413–2423. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-10-1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 13.Rizvi SM, Mancino L, Thammavongsa V, Cantley RL, Raghavan M. A polypeptide binding conformation of calreticulin is induced by heat shock, calcium depletion, or by deletion of the C-terminal acidic region. Mol Cell. 2004;15:913–923. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wearsch PA, et al. MHC class I molecules expressed with monoglucosylated N-linked glycans bind calreticulin independently of their assembly status. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:25112–25121. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401721200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Y, et al. ERp57 does not require interactions with calnexin and calreticulin to promote assembly of class I histocompatibility molecules, and it enhances peptide loading independently of its redox activity. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:10160–10173. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808356200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diedrich G, Bangia N, Pan M, Cresswell P. A role for calnexin in the assembly of the MHC class I loading complex in the endoplasmic reticulum. J Immunol. 2001;166:1703–1709. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.3.1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sadasivan B, Lehner PJ, Ortmann B, Spies T, Cresswell P. Roles for calreticulin and a novel glycoprotein, tapasin, in the interaction of MHC class I molecules with TAP. Immunity. 1996;5:103–114. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80487-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ortmann B, et al. A critical role for tapasin in the assembly and function of multimeric MHC class I-TAP complexes. Science. 1997;277:1306–1309. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5330.1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Radcliffe CM, et al. Identification of specific glycoforms of MHC class I heavy chains suggests that class I peptide loading is an adaptation of the quality control pathway involving calreticulin and ERp57. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:46415–46423. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202466200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cannon KS, Helenius A. Trimming and readdition of glucose to N-linked oligosaccharides determines calnexin association of a substrate glycoprotein in living cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:7537–7544. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.11.7537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen M, Bouvier M. Analysis of interactions in a tapasin/class I complex provides a mechanism for peptide selection. EMBO J. 2007;26:1681–1690. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jackson MR, Song ES, Yang Y, Peterson PA. Empty and peptide-containing conformers of class I major histocompatibility complex molecules expressed in Drosophila melanogaster cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:12117–12121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.24.12117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lauvau G, et al. Tapasin enhances assembly of TAP-dependent and independent peptides with HLA-A2 and HLA-B27 expressed in insect cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:31349–31358. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.44.31349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park B, et al. Redox regulation facilitates optimal peptide selection by MHC class I during antigen processing. Cell. 2006;127:369–382. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kozlov G, et al. Crystal structure of the bb’ domains of the protein disulfide isomerase ERp57. Structure. 2006;14:1331–1339. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomson SP, Williams DB. Delineation of the lectin site of the molecular chaperone calreticulin. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2005;10:242–251. doi: 10.1379/CSC-126.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Leeuwen JEM, Kearse KP. Deglucosylation of N-linked glycans is an important step in the dissociation of calreticulin-class I-TAP complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13997–14001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang W, Wearsch PA, Yajuan Z, Leonhardt RM, Cresswell P. A role for UDP-glucose glycoprotein glucosyltransferase in expression and quality control of MHC class I molecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011:4956–4961. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102527108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trombetta ES, Simons JF, Helenius A. Endoplasmic reticulum glucosidase II is composed of a catalytic subunit, conserved from yeast to mammals, and a tightly bound noncatalytic HDEL-containing subunit. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:27509–27516. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.44.27509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.