Abstract

Prostate cancer development is associated with hyperactive androgen signaling. However, the molecular link between androgen receptor (AR) function and humoral factors remains elusive. A prostate cancer mouse model was generated by selectively mutating the AR threonine 877 into alanine in prostatic epithelial cells through Cre-ERT2–mediated targeted somatic mutagenesis. Such AR point mutant mice (ARpe-T877A/Y) developed hypertrophic prostates with responses to both an androgen antagonist and estrogen, although no prostatic tumor was seen. In prostate cancer model transgenic mice, the onset of prostatic tumorigenesis as well as tumor growth was significantly potentiated by introduction of the AR T877A mutation into the prostate. Genetic screening of mice identified Wnt-5a as an activator. Enhanced Wnt-5a expression was detected in the malignant prostate tumors of patients, whereas in benign prostatic hyperplasia such aberrant up-regulation was not obvious. These findings suggest that a noncanonical Wnt signal stimulates development of prostatic tumors with AR hyperfunction.

Keywords: antiandrogen, hormone-refractory state, TRAMP

The androgen receptor (AR) is pivotal in prostate cancer development (1, 2), because either androgen depletion (3, 4) or androgen antagonism (5, 6) is clinically successful in attenuating prostate cancer growth in its initial stages. However, most patients treated with antiandrogen therapies eventually transition into a “hormone-refractory” state (2, 7), which is usually aggressive and frequently lethal. Up-regulation of AR target genes also occurs during the transitional stage (2, 7). Rising serum levels of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) accompany the development of the hormone-refractory state (8). Thus, enhancement of AR-mediated androgen signaling appears to portend the onset of tumor progression, although its molecular basis remains largely elusive.

AR is a member of the nuclear steroid receptor gene superfamily, and acts as a hormone-dependent transcription factor (9). Activation of AR by ligand binding transcriptionally controls expression of the target genes (10, 11). Like the other members, AR is functionally and structurally divided into five domains, A–E. The most conserved, the C domain, in the middle of the receptor protein encodes the DNA binding domain, whereas the C-terminal E domain encompasses the hormone/ligand binding domain (LBD). The N-terminal A/B domains and the LBD bear the transactivation function, and dock transcriptional coregulators or coregulator complexes for ligand-dependent transcriptional regulation (12). As tumors transition, they generate AR mutations leading to altered responses to steroid hormones and synthetic ligands, including resistance to androgen antagonists (13, 14). Most point mutations found in prostatic tumors of hormone-refractory patients have been mapped in the AR LBD (15, 16). As the hydrophobic pocket in the LBD specifically recognizes and captures androgens and AR ligands, the mutated amino acid residues in the LBD, particularly in the motifs constituting the pocket, are presumed to impair specificity in hormone/ligand recognition. Indeed, in in vitro cell cultures, such human (h)AR point mutants display acquired responsiveness to other steroid hormones and androgen antagonists (17, 18). The point mutation threonine 877 to alanine (T877A) in the LBD is one of the most common mutations in prostate tumors (15, 16). Significantly, the hAR point mutants found in hormone-refractory patients appear hyperactive in terms of transactivation, because the mutants are hypersensitive to endogenous nonandrogenic steroid hormones as well as to clinically used AR synthetic antagonists. In addition to the aberrant hyperfunction of the AR mutants, cellular signals from the tumor cells and surrounding nontumor cells also contribute to prostate tumor progression (19). Growth factors secreted by the stroma and prostate epithelium act in concert with signaling through the activated AR to stimulate prostate cancer cell growth in vitro (20). However, in animal models, the roles of these humoral factors remain to be investigated. Several mouse prostate cancer models have been established (21), and spontaneous prostatic tumorigenesis is seen in one of the transgenic murine prostate cancer model (TRAMP) lines expressing a T-antigen gene (22). However, androgen dependency in prostatic tumor development and onset could not be recapitulated in such mouse models (21).

To determine whether aberrantly potentiated AR signaling stimulates prostate cancer growth in vivo, we have generated an experimental prostate cancer model in mice by selectively mutating AR T877 to A in prostatic epithelial cells of adult mice, through Cre-ERT2-mediated spatiotemporally controlled targeted somatic mutagenesis (23). Such AR point mutant mice (ARpe-T877A/Y) exhibited hypertrophic prostates but failed to develop prostate tumors. In orchidectomized AR mutants, hydroxyflutamide (HF), a clinically used androgen antagonist, stimulated prostate growth. By introducing the T877A mutation into epithelial cells of the prostate of adult TRAMP transgenic mice, the onset of tumor formation was shortened and tumor growth was stimulated. Genetic screening of tumor growth factors in these mice led to the identification of a noncanonical Wnt ligand (Wnt-5a) that accelerated tumor growth. Importantly, enhanced Wnt-5a expression was also present in tumor cells of prostate cancer patients but not in prostatic cells from patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia. These findings demonstrate that the genetic mutation T877A in the AR promotes prostatic tumor growth by stimulating a noncanonical Wnt signaling pathway.

Results

Introduction of the Human T877A AR Mutation into the Mouse AR Gene Locus.

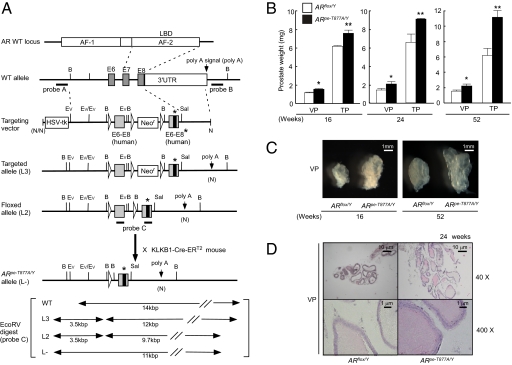

To create conditional mutants (T877A) located in the AR LBD, we replaced the mouse genomic DNA segment encompassing AR exons 6–8 with a DNA segment containing the corresponding human coding sequence flanked by three loxP sites, followed by a similar DNA segment encoding the T877A mutation (Fig. 1A). The knocked-in and floxed (L2) mouse line (ARflox/Y) (24, 25), in which the Neo cassette was deleted by Cre-mediated excision in embryonic stem cells, had no overt abnormalities and grew normally (Fig. S1A). The prostate was phenotypically normal, showing considerable budding and differentiation into columnar glandular epithelium. The size of the prostate, however, was smaller than that of the wild-type mouse at 10 wk of age (Fig. S1 C and D). When evaluated at 20 wk, the growth of the ventral prostate (VP) was delayed in comparison with the anterior (AP) and dorsal (DP) prostates and the seminal vesicle (SV). ARflox/Y males were fertile but their reproductive activity was reduced. However, the smaller prostates were structurally intact. Because growth of the prostate is dependent on AR-mediated androgen signaling (24–26), it is likely that the prostatic phenotype of the ARflox/Y results from hypofunction of the AR protein. The ARflox/Y showed normal levels of AR mRNA but reduced AR protein levels (Fig. S2 C and D). Therefore, the genetic manipulation may have affected stabilization of the AR protein. Serum testosterone levels were up-regulated, owing to decreased negative feedback on androgen biosynthesis (Fig. S1B). Thus, although androgen signaling in ARflox/Y mice appears reduced but not significantly impaired, we concluded that this floxed mouse line was appropriate for further study.

Fig. 1.

Selective introduction of the AR T877A mutation into prostatic epithelial cells of adult mice. (A) The targeting strategy for insertion of the ART877A mutation is illustrated. The diagram shows the wild-type AR genomic locus, targeting vector, floxed ART877A L3 and L2 alleles, and the ART877A allele (L-) obtained after Cre-mediated excision of human exons 6–8. B (BamHI), Ev (EcoRV), and loxP sites are indicated by arrowheads. The T877A mutation site are indicated by asterisks. (B) Ventral prostates (VP) and total prostates (TP) of ARpe-T877A/Y mice (n = 10) and ARflox/Y mice (n = 10) were weighed at 16, 24, and 52 wk of age. The ventral prostate lobes of ARpe-T877A/Y mice were about 1.5 times heavier than those of the control mice (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 by one-way ANOVA). The anterior and dorsal prostates showed similar results. Error bars represent the SD. (C) Prostate lobes of 16- and 52-wk-old ARpe-T877A/Y mice and ARflox/Y mice under a dark-field dissection microscope. ART877A mutation promoted prostate lobe growth. (D) Hematoxylin and eosin-stained ventral prostates of 24-wk-old ARpe-T877A/Y mice and ARflox/Y mice.

Selective Introduction of the T877A AR Mutation into Prostatic Epithelial Cells of Adult Mice.

We then used the KLKB1-Cre-ERT2 mouse line (23) and a T877A mouse line to generate a prostatic epithelium-specific, T877A knock-in. First, prostate-specific excision by Cre was confirmed using a tester mouse line in which the β-galactosidase gene was induced by Cre-mediated excision (27). Cre enzymatic activity (the Cre-ERT2 system) requires activation of an estrogen receptor point mutant which is sensitive only to an ERα partial agonist, tamoxifen (TAM), but not to endogenous estrogens (23). Following treatment with TAM for 5 d, clear staining of β-galactosidase was seen in the prostates (Fig. S2A) but not in the other tissues tested. We then crossed the ARflox/Y mice with the KLKB1-Cre-ERT2 mice to replace protein expression of the wild-type hAR LBD by the point-mutated (T877A) hAR LBD through Cre-mediated excision of the loxP sites (Fig. 1A), generating a KLKB1-Cre-ERT2; ARflox/Y mouse line. Then, these mice at the age of 16 wk were treated with TAM for 5 d to generate ARpe-T877A/Y, in which AR T877A was selectively expressed in prostatic epithelial cells. These mice exhibited no overt abnormalities and grew normally. Similar to ARflox/Y mice, the ARpe-T877A/Y mice were fertile but had impaired reproductive activity. The T877A mutation was detectable in the genomic sequences of prostates from 15 out of 20 mice (Fig. S2B). The expression levels of the AR transcript and protein in the ARpe-T877A/Y prostate were indistinguishable from those of ARflox/Y (Fig. S2 C and D). From these observations, we concluded that the Cre-ERT2 system was successful in selectively and inductively expressing the AR T877A mutant in the mouse prostate.

ARpe-T877A/Y Mice Exhibit Androgen-Induced Prostate Development Without Detectable Tumorigenesis.

The prostatic phenotype of ARpe-T877A/Y mice was indistinguishable from that of ARflox/Y (Fig. 1C); prostate growth, however, was enhanced up until 16 wk in comparison with ARflox/Y control mice (the KLKB1-Cre-ERT2; ARflox/Y line untreated with TAM) (Fig. 1B). Hyperproliferation of prostatic cells, as demonstrated by an increased number of cells incorporating BrdU, was seen in ARpe-T877A/Y mice, whereas expression of activated caspase-3, an apoptotic factor, was unaltered (Fig. S2E). No prostate tumors were detected by histological analysis of the ARpe-T877A/Y mice at 52 wk (Fig. 1 C and D) or later. Because endogenous testosterone levels were significantly up-regulated (Fig. S1B), the mice were castrated (24, 27). Prostate development in castrated ARpe-T877A/Y mice was severely retarded at 24 wk of age. VP (Fig. 2 A and B) and total prostate (TP) (Fig. 2A) were restored by 5α-dihydrotestosterone (DHT) treatment for 3 wk. This DHT response was seen in both castrated ARflox/Y and ARpe-T877A/Y mice. These observations suggested that prostatic development of these lines was dependent on endogenous androgen. However, the T877A point mutation was not potent enough to trigger tumorigenesis.

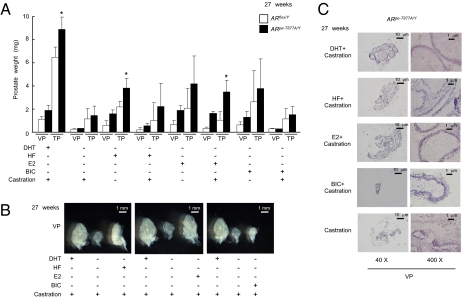

Fig. 2.

Aberrant prostate growth responses to hormonal and antagonist signals in ARpe-T877A/Y mice. (A) ARpe-T877A/Y mice and ARflox/Y mice at 24 wk of age were divided into eight groups (n = 5 per group) and treated with hormones (DHT, HF, E2, or BIC) for 3 wk after castration or a sham operation. Prostates were then excised and weighed. Prostate degeneration in castrated ARflox/Y mice was only prevented by DHT; however, all hormonal treatments were protective against prostate degeneration in ARpe-T877A/Y mice (*P < 0.05 with one-way ANOVA). Error bars represent the SD. BIC, bicalutamide; DHT, 5α-dihydrotestosterone; E2, 17β-estradiol; HF, hydroxyflutamide. (B) Typical ventral prostates of castrated ARpe-T877A/Y mice after hormonal treatment. (C) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of ventral prostates of ARpe-T877A/Y mice treated with the indicated hormones. The prostatic tubule structure in ARpe-T877A/Y mice was maintained by treatment with either HF or E2.

Growth of the Prostate in ARpe-T877A/Y Mice Is Stimulated by both an Androgen Antagonist and Estrogen.

At the initial stages of prostate cancer, while the cells retain hormone responsiveness, patients are treated with synthetic androgen antagonists to attenuate androgen-induced tumor development. However, after several years of treatment, the hormone-dependent state is frequently lost and new genetic mutations appear in the AR exons encoding the LBD (15, 16, 28). We therefore asked whether ARpe-T877A/Y mice develop a response similar to that seen in hormone-refractory patients. A 3-wk treatment with HF, a clinically used AR antagonist, stimulated prostate growth in ARpe-T877A/Y mice but not in ARflox/Y mice (Fig. 2 A and B). Likewise, high doses (160 μg/d for 3 wk) of exogenous 17β-estradiol (E2) clearly stimulated prostatic growth, whereas another AR antagonist, bicalutamide (BIC; Casodex), elicited no stimulatory effect (Fig. 2C). Thus, it appeared likely that ARpe-T877A/Y mice recapitulate the abnormal responses seen in hormone-refractory prostate cancer patients.

Accelerated Tumorigenesis Induced by the T877A AR Mutation in an Experimental Mouse Model of Prostate Cancer.

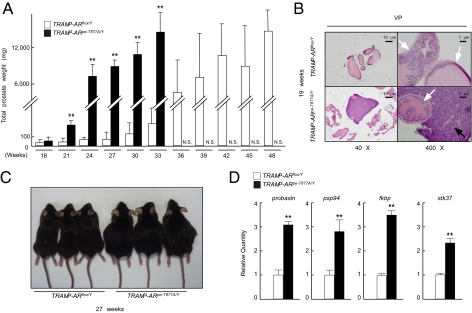

Because ARpe-T877A/Y mice failed to develop detectable prostate tumors even after 1 y, we tested the impact of the T877A AR mutation on prostate tumor growth in a known experimental prostate cancer model (TRAMP). This mouse line spontaneously develops prostate cancer in which the tumor resembles that seen in humans (22). TRAMP mice were crossed with KLKB1-Cre-ERT2; ARflox/Y mice to generate a TRAMP; KLKB1-Cre-ERT2; ARflox/Y mouse line. At 16 wk of age, these mice were treated with TAM for 5 d to introduce the T877A mutation into the prostate. This mouse line (TRAMP-ARpe-T877A/Y) exhibited an earlier onset of prostate tumor growth than did the TRAMP-ARflox/Y mice (Fig. 3 A and C). The rapid growth of the prostate tumor led to the death of all of the TRAMP-ARpe-T877A/Y mice at around 36 wk of age. In contrast, TRAMP-ARflox/Y mice survived past 48 wk (Fig. 3A). Consistently, the expression levels of several known AR target genes (Probasin, PSP94, Fkbp51, Stk37) (29–31) were higher in prostate tumors from TRAMP-ARpe-T877A/Y than those of TRAMP-ARflox/Y (Fig. 3D). However, no remarkable alteration in the expression levels of the tumor-related genes was detected (Fig. S3). Histologically, the prostate tumor phenotype of TRAMP-ARpe-T877A/Y mice at 19 wk was indistinguishable from that of TRAMP-ARflox/Y mice (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Early onset of tumor growth was induced by the ART877A mouse mutation in an experimental model of prostate cancer. (A) The effect of the ART877A mutation on the growth of prostate tumors. TRAMP-ARpe-T877A/Y mice and TRAMP-ARflox/Y mice were divided into 11 groups (n = 5 per group). From 18 to 50 wk of age, mice from each group were killed every 3 wk and the prostates were weighed. TRAMP-ARpe-T877A/Y mice developed prostate tumors early and the tumors rapidly grew until the animals’ death by 36 wk (**P < 0.01 with one-way ANOVA). TRAMP-ARflox/Y mice developed prostate tumors after 24 wk and most of the mice survived past 50 wk. Black columns indicate TRAMP-ARpe-T877A/Y mice, and white columns indicate TRAMP-ARflox/Y mice. N.S., no survival. (B) Hematoxylin and eosin-stained prostate lobes of TRAMP-ARpe-T877A/Y and TRAMP-ARflox/Y mice at 19 wk of age. Ventral prostates of both TRAMP-ARflox/Y and TRAMP-ARpe-T877A/Y mice were composed of undifferentiated sheets of malignant cells lacking the normal glandular prostatic architecture. (C) External appearance of 27-wk-old TRAMP-ARpe-T877A/Y mice and TRAMP-ARflox/Y mice. (D) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of AR target genes in TRAMP-ARpe-T877A/Y mice and TRAMP-ARflox/Y mice. The ratios of gene expression levels in TRAMP-ARpe-T877A/Y prostate tumors compared with TRAMP-ARflox/Y are representative of five independent experiments (**P < 0.01 with Student's t test).

To test whether both the early onset and the rapid growth of the prostatic tumors in TRAMP-ARpe-T877A/Y were tumor-autonomous and/or androgen-dependent, we transplanted the tumors into the ventral prostate lobe of nude mice (Fig. S4A). The prostatic tumors continued to grow. At 8 wk posttransplantation, the tumors derived from TRAMP-ARpe-T877A/Y mice were three times larger than those from TRAMP-ARflox/Y mice (Fig. S4 B–D). When these mice were castrated, such tumor growth was more attenuated from TRAMP-ARflox/Y mice than from TRAMP-ARpe-T877A/Y mice (Fig. S5 A and B), suggesting that tumor growth is dependent on activated AR function. From these findings, we presumed that the tumor progression in TRAMP-ARpe-T877A/Y mice can be attributed to AR hyperfunction induced by endogenous hormones. Moreover, we assumed that a certain factor(s) expressed in the prostate potentiated the growth of prostate tumors harboring the T877A mutation.

Noncanonical Wnt Ligand Acts as an Activator in Experimental Prostate Cancer.

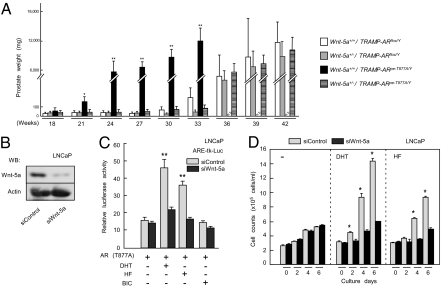

We reasoned that the function of the AR mutant in tumor growth was potentiated by cross-talk with prostatic growth factors and/or cytokine signaling pathways. Several major candidate factors (Fgf10, Stat3, Tab2, Wnt-5a), already documented to modulate prostate growth in vivo and in vitro, were examined by crossing the TRAMP; KLKB1-Cre-ERT2; ARflox/Y mouse line with lines deficient in the candidate factors (32–37). The offspring at 16 wk of age were then treated with TAM to introduce the ART877A mutation. Of the factors tested, haploinsufficiency of Wnt-5a (33) remarkably aborted the early onset and early lethality of the prostate tumors in TRAMP-ARpe-T877A/Y mice, and conferred prostatic growth similar to that observed in the TRAMP-ARflox/Y control line (Fig. 4A). Thus, Wnt-5a appeared to be an activator of AR-mediated prostate cancer growth. Wnt-5a is a ligand involved in the noncanonical Wnt signaling pathway that also coregulates the transactivation function of PPARγ (33). During studies of Wnt-5a action associating with AR hyperfunction, LNCaP cells were found to endogenously express Wnt-5a (Fig. 4B and Fig. S6). When Wnt-5a was knocked down (Fig. 4B and Fig. S6), transactivation function of liganded AR was clearly lowered (Fig. 4C). Consistently, androgen-dependent proliferation of LNCaP cells was attenuated by this Wnt-5a knockdown (Fig. 4D and Fig. S7).

Fig. 4.

Wnt-5a, a noncanonical Wnt ligand, is an activator for prostate tumors harboring the ART877A mutation. (A) The weights of prostates from Wnt-5a+/−; TRAMP-ARpe-T877A/Y mice and Wnt-5a+/−; TRAMP-ARflox/Y mice. Mice were divided into nine groups (n = 5 per group). Prostates of mice from each group were resected and weighed every 2 wk. Wnt-5a+/+; TRAMP-ARpe-T877A/Y or Wnt-5a+/+; TRAMP-ARflox/Y mice were also analyzed as controls. Note that even at 26 wk of age, Wnt-5a+/−; TRAMP-ARpe-T877A/Y mice did not develop significant prostate tumors (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 with one-way ANOVA). (B) Efficiencies of the indicated siRNAs toward human Wnt-5a in LNCaP cells. Western blot with α-Wnt-5a (R&D Systems) or α-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was performed 48 h after the transfection of siRNAs. (C and D) The attenuation of AR-mediated androgen signaling in LNCaP cells by Wnt-5a knockdown. LNCaP cells transfected with siRNAs were subjected to transfection for a reporter luciferase assay (C) or a cell proliferation assay (D). AR ligands were incubated with the cells for 12 h (C) or 6 d (D). Each point represents the mean ± SD of three separate experiments (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 with two-way ANOVA).

Aberrant Wnt-5a Expression in Human Prostate Tumors.

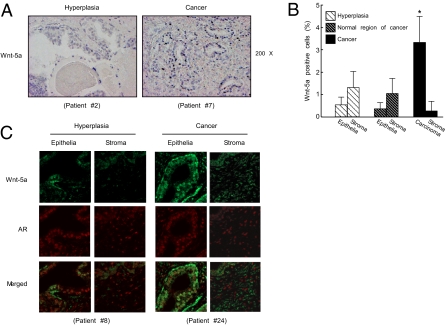

To address the impact of Wnt-5a on human prostate cancer, we examined the expression of Wnt-5a in human prostates. In benign prostatic hyperplasia, Wnt-5a expression levels were normal by immunohistochemical analysis (Fig. 5B). In contrast, malignant prostate tumors (Dataset S1) demonstrated aberrantly up-regulated Wnt-5a expression compared with that in the surrounding normal tissues (Fig. 5 A and B). Stromal–epithelial interactions and the bioactive factors produced by these interactions have proven to be important in cancer progression (19, 20). Here we examined whether Wnt-5a in carcinoma cells is acting in an autocrine fashion or in a paracrine fashion. By an immunofluorescence analysis, expressions of Wnt-5a and AR proteins were seen in both carcinoma and stromal cell types (Fig. 5C). However, colocalized expression of these two factors was predominantly detected in the carcinoma cells (Fig. 5C). Thus, it is likely that the Wnt-5a effect in carcinoma cells occurs primarily in an autocrine fashion. These findings suggest that Wnt-5a can serve as an activator of AR-mediated androgen signaling for prostate growth under certain pathological conditions in the human prostate, as seen in mice.

Fig. 5.

Aberrant Wnt-5a expression in human prostate cancer. (A) Wnt-5a expression was detected by immunostaining of the prostates of patients diagnosed with benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostate cancer. (B) The numbers of Wnt-5a-positive cells in the epithelium and interstitium in hyperplasia, the epithelium and interstitium in normal regions of prostate tumors, and carcinoma cells and interstitium in prostate tumors (Dataset S1). Nine patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia and 37 with prostate cancer were counted (*P < 0.05 with one-way ANOVA). (C) Immunofluorescent double staining for Wnt-5a (green) and AR (red) indicates that Wnt-5a and AR are mainly colocalized in the carcinoma cells in human prostate cancer. Such colocalization is absent in the stromal cells in prostate tumors. Representative images of the prostates from patients diagnosed with benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostate cancer are shown from three independent experiments.

Discussion

Mouse models of prostate cancer have been developed to improve understanding of the molecular basis of prostate carcinogenesis and explore treatment regimens for prostate cancer patients (21). Some model limitations are inherent because prostatic structure and major areas/cells of tumors are not identical in human patients and mouse models. Nonetheless, the impact of oncogenic and antioncogenic genes in prostatic tumors has been tested by mouse genetic approaches (21). Among such candidate factors AR is of prime interest, because it is involved in all stages of prostate cancer (16, 38). Androgen actions are indispensable for prostate development and function, and appear stimulatory for tumorigenesis, evidently acting through AR. Moreover, AR is considered a key factor in prostate cancer even after transition to the androgen-independent state (16, 38). Whatever the function of AR in androgen-dependent and -independent prostate cancer, mouse models to assess AR function have been unavailable owing to the innate roles of AR in prostate development (24, 25). To avoid this difficulty, we have introduced a modified Cre-loxP system to selectively introduce a point mutation into the AR LBD in the prostates of adult mice (ARpe-T877A/Y mice). This mutation (T877A) is often seen in prostatic tumors of androgen-independent patients (17, 18).

Neoplasia was undetectable in the prostates of the ARpe-T877/Y mice even after 1 y, indicating that a single mutation rendering AR hyperactive is not sufficient to trigger prostatic tumorigenesis. The onset of prostatic tumors bearing hyperfunctioning AR thus appears to require at least one additional factor in mice, as already predicted in the literature (21, 28). In our initial pilot experiment, we sought to compare the impact of the T877A mutation on prostate tumorigenesis between Pten+/− (generously provided by A. Suzuki, Kyushu University, Fukuoka, Japan) and TRAMP mouse model lines, and found no significant differences in tumor incidence and progression in the Pten+/− genetic background at 30 wk of age. In contrast, crossing the ARpe-T877/Y line with the TRAMP line consistently enhanced tumor development in TRAMP mice and, more importantly, androgen dependency became evident. Thus, the TRAMP-ARpe-T877/Y line constitutes a unique mouse model of androgen-dependent prostate cancer, and will be useful for exploration of the molecular basis underlying the transition from androgen dependency to the refractory state.

TRAMP-ARpe-T877A/Y mice demonstrated that the T877A mutation significantly shortened the onset of tumor development and accelerated tumor growth. The average lifespan of the TRAMP-ARflox/Y line was greater than 48 wk, whereas that of TRAMP-ARpe-T877A/Y mice was less than 36 wk. TRAMP-ARpe-T877A/Y mice succumbed to tumors that were equivalent in size to their total body weight. Furthermore, the transplanted prostate tumors from the TRAMP-ARpe-T877A/Y mice grew three times as fast as the control line in nude mice. These findings suggest that a prostatic factor potentiates the effect of the AR hyperfunction that drives prostate tumor progression.

Using a microarray analysis and quantitative PCR validation (39) of TRAMP-ARpe-T877A/Y mice, we observed the expected alterations in tumor genes such as TERT and Cdk2 (40, 41) and the tumor suppressor genes NKX3.1, ATBF1, and p21 (42, 43) (Fig. S3). However, in this analysis, we were unable to identify new candidate genes accounting for tumor growth at this stage. Therefore, we opted for a genetic screening strategy that crossed mice deficient in regulators of cell proliferation. Wnt-5a was identified as an activator of early onset and rapid growth of prostate tumors in TRAMP-ARpe-T877A/Y mice. We also found aberrantly up-regulated expression of Wnt-5a in human prostate tumors. Wnt-5a is a noncanonical Wnt ligand involved in cell proliferation and differentiation, particularly during embryonic development (34, 44, 45).

It is conceivable that ectopic Wnt-5a expression potentiates cancer cell proliferation (46, 47), because Wnt-5a protein is aberrantly up-regulated in tumors compared with the normal tissues of prostate cancer patients. In accordance with this observation, Wnt-5a was able to coregulate the transactivation function of T877A-mutated AR in a transient expression assay and promote proliferation of LNCaP cells. Together with the finding of limited colocalization of Wnt-5a with AR in carcinoma cells, it is likely that Wnt-5a potentiates AR-mediated androgen signaling, presumably via an autocrine fashion in the carcinoma cells, thereby promoting tumorigenesis. It could also be postulated that Wnt-5a expression is actually induced by an upstream factor, particularly at an initial stage and at the transition to the hormone-refractory state. These upstream factors might be particularly significant in prostate tumor progression. In this respect, the identification of factors subsequently activating the noncanonical Wnt signaling pathway is an important early step in understanding the molecular basis of prostate cancer progression.

Materials and Methods

Generation of the Mouse Model.

The genomic AR DNA fragment was isolated from a TT2 embryonic stem (ES) cell genomic library. The targeting vector was created by inserting human cDNA of wild-type AR exons 6–8 with two loxP sites and human cDNA of ART877A exons 6–8 together with a positive Neo selective marker (Neor) (Fig. 1A). A thymidine kinase gene (HSV-tk) cassette was attached to the 5′ end of the targeting vector for negative selection. The targeted TT2 ES clones were selected after positive–negative selection with Southern analysis, and then aggregated with single eight-cell embryos from CD-1 mice (32, 48). The floxed AR mice (ARflox/Y), originally on a hybrid C57BL/6 and CBA genetic background, were backcrossed for four generations into a C57BL/6J background. These mice were mated with KLKB1-Cre-ERT2 transgenic mice that express the tamoxifen-dependent Cre-ERT2 recombinase under the control of the human PSA promoter, allowing us to introduce the AR T877A mutation selectively into epithelial cells of fully differentiated prostates of adult mice (23). Tamoxifen administration [daily injection (1 mg/d) for 5 d] to 6-wk-old mice was performed as described (23). To generate Wnt-5a+/−/TRAMP-ARpe-T877A/Y mice, we first mated KLKB1-Cre-ERT2; ARflox/Y mice with TRAMP transgenic [C57BL/6-Tg (TRAMP) 8247Ng/J; The Jackson Laboratory] mice. Then we interbred TRAMP-ARpe-T877A/Y mice with mice heterozygous for Wnt-5a deficiency (33). All mice were maintained according to the protocol approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Tokyo.

Analysis of Prostate Morphology.

Mice were fully anesthetized and ventral, anterior, and dorsal prostate lobes were removed, weighed, and examined under a dark-field dissection microscope. Then, prostate tissues were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. Sections (8 μm) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin for histologic examination (24). For methods for immunohistochemistry, RNA preparation, and real-time RT-PCR, see SI Materials and Methods.

Castration and Hormone Replacement.

Twenty-four-week-old mice were castrated or sham-operated, and slow-releasing pellets of DHT (160 μg/d), HF (160 μg/d), E2 (160 μg/d), or Casodex (BIC) (4.1 μg/d) (Innovative Research) were implanted s.c. in the scapular region behind the neck (27). After 3 wk, ventral prostates were resected, weighed, and examined.

Transplantation of Prostate Cancer.

When prostate tumors in TRAMP-ARpe-T877A/Y mice and TRAMP-ARflox/Y mice reached ~5,000 mg, tumors were resected and minced in a 10% volume of physiological saline. A volume (0.05 mL) of minced tissue was injected into a ventral prostate lobe of nude mice (BALB/c, Scl-nu/nu). Prostates were resected and weighed 8 wk after transplantation.

Statistical Analysis.

For all graphs, data are represented as means ± SD. Statistical differences were determined using one-way ANOVA or two-way ANOVA followed by post hoc comparison with Fisher's protected least significant difference test or Student's t test. Statistical significance is displayed as *P < 0.05 or **P < 0.01.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Y. Homma, S. Horie, T. Ichikawa, and S. Teshima for helpful discussions; Dr. A. Suzuki for the Pten+/− mouse line; Drs. T. Sato, K. Yoshimura, Y. Nakamichi, J. Miyamoto, H. Shiina, Ms. Y. Sato, and S. Tanaka for generation of the knock-in mice; Drs. K. Igarashi and J. Kanno for microarray analysis; and M. Yamaki and K. Motoi for manuscript preparation. This work was supported by funds from the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, the Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer, and in part by priority areas from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (S.K.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1014850108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.De Marzo AM, et al. Inflammation in prostate carcinogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:256–269. doi: 10.1038/nrc2090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hsieh AC, Small EJ, Ryan CJ. Androgen-response elements in hormone-refractory prostate cancer: Implications for treatment development. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:933–939. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70316-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Denmeade SR, Isaacs JT. A history of prostate cancer treatment. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:389–396. doi: 10.1038/nrc801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ross RW, et al. Efficacy of androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) in patients with advanced prostate cancer: Association between Gleason score, prostate-specific antigen level, and prior ADT exposure with duration of ADT effect. Cancer. 2008;112:1247–1253. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prostate Cancer Trialists Collaborative Group Maximum androgen blockade in advanced prostate cancer: An overview of the randomised trials. Lancet. 2000;355:1491–1498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scholz M, et al. Prostate-cancer-specific survival and clinical progression-free survival in men with prostate cancer treated intermittently with testosterone-inactivating pharmaceuticals. Urology. 2007;70:506–510. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oudard S, et al. New targeted therapies in hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Bull Cancer. 2007;94(7 Suppl):F62–F68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lilja H, Ulmert D, Vickers AJ. Prostate-specific antigen and prostate cancer: Prediction, detection and monitoring. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:268–278. doi: 10.1038/nrc2351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mangelsdorf DJ, et al. The nuclear receptor superfamily: The second decade. Cell. 1995;83:835–839. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90199-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Norris JD, et al. The homeodomain protein HOXB13 regulates the cellular response to androgens. Mol Cell. 2009;36:405–416. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Q, et al. Androgen receptor regulates a distinct transcription program in androgen-independent prostate cancer. Cell. 2009;138:245–256. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG. The coregulator exchange in transcriptional functions of nuclear receptors. Genes Dev. 2000;14:121–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bohl CE, Gao W, Miller DD, Bell CE, Dalton JT. Structural basis for antagonism and resistance of bicalutamide in prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:6201–6206. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500381102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoshida T, et al. Antiandrogen bicalutamide promotes tumor growth in a novel androgen-dependent prostate cancer xenograft model derived from a bicalutamide-treated patient. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9611–9616. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taplin ME, et al. Mutation of the androgen-receptor gene in metastatic androgen-independent prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1393–1398. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505253322101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feldman BJ, Feldman D. The development of androgen-independent prostate cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2001;1:34–45. doi: 10.1038/35094009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun C, et al. Androgen receptor mutation (T877A) promotes prostate cancer cell growth and cell survival. Oncogene. 2006;25:3905–3913. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suzuki H, et al. Codon 877 mutation in the androgen receptor gene in advanced prostate cancer: Relation to antiandrogen withdrawal syndrome. Prostate. 1996;29:153–158. doi: 10.1002/1097-0045(199609)29:3<153::aid-pros2990290303>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu H, Kortylewski M, Pardoll D. Crosstalk between cancer and immune cells: Role of STAT3 in the tumour microenvironment. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:41–51. doi: 10.1038/nri1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu P, et al. Macrophage/cancer cell interactions mediate hormone resistance by a nuclear receptor derepression pathway. Cell. 2006;124:615–629. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahmad I, Sansom OJ, Leung HY. Advances in mouse models of prostate cancer. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2008;10:e16. doi: 10.1017/S1462399408000689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Masumori N, et al. A probasin-large T antigen transgenic mouse line develops prostate adenocarcinoma and neuroendocrine carcinoma with metastatic potential. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2239–2249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ratnacaram CK, et al. Temporally controlled ablation of PTEN in adult mouse prostate epithelium generates a model of invasive prostatic adenocarcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:2521–2526. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712021105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawano H, et al. Suppressive function of androgen receptor in bone resorption. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:9416–9421. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1533500100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sato T, et al. Late onset of obesity in male androgen receptor-deficient (AR KO) mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;300:167–171. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02774-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mooradian AD, Morley JE, Korenman SG. Biological actions of androgens. Endocr Rev. 1987;8:1–28. doi: 10.1210/edrv-8-1-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakamura T, et al. Estrogen prevents bone loss via estrogen receptor α and induction of Fas ligand in osteoclasts. Cell. 2007;130:811–823. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brinkmann AO, Trapman J. Prostate cancer schemes for androgen escape. Nat Med. 2000;6:628–629. doi: 10.1038/76194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.He HH, et al. Nucleosome dynamics define transcriptional enhancers. Nat Genet. 2010;42:343–347. doi: 10.1038/ng.545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jia L, et al. Genomic androgen receptor-occupied regions with different functions, defined by histone acetylation, coregulators and transcriptional capacity. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3645. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kwong J, Xuan JW, Chan PS, Ho SM, Chan FL. A comparative study of hormonal regulation of three secretory proteins (prostatic secretory protein-PSP94, probasin, and seminal vesicle secretion II) in rat lateral prostate. Endocrinology. 2000;141:4543–4551. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.12.7818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sekine K, et al. Fgf10 is essential for limb and lung formation. Nat Genet. 1999;21:138–141. doi: 10.1038/5096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takada I, et al. A histone lysine methyltransferase activated by non-canonical Wnt signalling suppresses PPAR-γ transactivation. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1273–1285. doi: 10.1038/ncb1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamaguchi TP, Bradley A, McMahon AP, Jones S. A Wnt5a pathway underlies outgrowth of multiple structures in the vertebrate embryo. Development. 1999;126:1211–1223. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.6.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Katoh M, Katoh M. STAT3-induced WNT5A signaling loop in embryonic stem cells, adult normal tissues, chronic persistent inflammation, rheumatoid arthritis and cancer. Int J Mol Med. 2007;19:273–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sanjo H, et al. TAB2 is essential for prevention of apoptosis in fetal liver but not for interleukin-1 signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:1231–1238. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.4.1231-1238.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang S, et al. Prostate-specific deletion of the murine Pten tumor suppressor gene leads to metastatic prostate cancer. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:209–221. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00215-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen CD, et al. Molecular determinants of resistance to antiandrogen therapy. Nat Med. 2004;10:33–39. doi: 10.1038/nm972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fukuda T, et al. DEAD-box RNA helicase subunits of the Drosha complex are required for processing of rRNA and a subset of microRNAs. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:604–611. doi: 10.1038/ncb1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Donehower LA, Lozano G. 20 years studying p53 functions in genetically engineered mice. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:831–841. doi: 10.1038/nrc2731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shay JW, Wright WE. Telomerase: A target for cancer therapeutics. Cancer Cell. 2002;2:257–265. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00159-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lei Q, et al. NKX3.1 stabilizes p53, inhibits AKT activation, and blocks prostate cancer initiation caused by PTEN loss. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:367–378. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sun X, et al. Frequent somatic mutations of the transcription factor ATBF1 in human prostate cancer. Nat Genet. 2005;37:407–412. doi: 10.1038/ng1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Veeman MT, Axelrod JD, Moon RT. A second canon. Functions and mechanisms of β-catenin-independent Wnt signaling. Dev Cell. 2003;5:367–377. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00266-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takada I, Kouzmenko AP, Kato S. Wnt and PPARγ signaling in osteoblastogenesis and adipogenesis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2009;5:442–447. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2009.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McDonald SL, Silver A. The opposing roles of Wnt-5a in cancer. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:209–214. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pukrop T, Binder C. The complex pathways of Wnt 5a in cancer progression. J Mol Med. 2008;86:259–266. doi: 10.1007/s00109-007-0266-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yoshizawa T, et al. Mice lacking the vitamin D receptor exhibit impaired bone formation, uterine hypoplasia and growth retardation after weaning. Nat Genet. 1997;16:391–396. doi: 10.1038/ng0897-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.