Abstract

In the field of induced potency and fate reprogramming, it remains unclear what the best starting cell might be and to what extent a cell need be transported back to a more primitive state for translational purposes. Reprogramming a committed cell back to pluripotence to then instruct it toward a particular specialized cell type is demanding and may increase risks of neoplasia and undesired cell types. Precursor/progenitor cells from the organ of therapeutic concern typically lack only one critical attribute—the capacity for sustained self-renewal. We speculated that this could be induced in a regulatable manner such that cells proliferate only in vitro and differentiate in vivo without the need for promoting pluripotence or specifying lineage identity. As proof-of-concept, we generated and tested the efficiency, safety, engraftability, and therapeutic utility of “induced conditional self-renewing progenitor (ICSP) cells” derived from the human central nervous system (CNS); we conditionally induced self-renewal efficiently within neural progenitors solely by introducing v-myc tightly regulated by a tetracycline (Tet)-on gene expression system. Tet in the culture medium activated myc transcription and translation, allowing efficient expansion of homogeneous, clonal, karyotypically normal human CNS precursors ex vivo; in vivo, where Tet was absent, myc was not expressed, and self-renewal was entirely inactivated (as was tumorigenic potential). Cell proliferation ceased, and differentiation into electrophysiologically active neurons and other CNS cell types in vivo ensued upon transplantation into rats, both during development and after adult injury—with functional improvement and without neoplasia, overgrowth, deformation, emergence of non-neural cell types, phenotypic or genomic instability, or need for immunosuppression. This strategy of inducing self-renewal might be applied to progenitors from other organs and may prove to be a safe, effective, efficient, and practical method for optimizing insights gained from the ability to reprogram cells.

Keywords: stem cells, stroke, multipotence, hemorrhage

Although intense interest has been generated by the “reprogramming” of differentiated somatic cells (e.g., skin fibroblasts) to a state of pluripotence by forcing expression of three to four genes (1–3), the question remains whether an end-committed cell from an irrelevant tissue is the best initiator of therapy in a particular organ. Reprogramming all of the way back to pluripotence may involve more reverse steps than is necessary; returning to or preserving potential fates more directly pertinent to a given organ system or germ layer (i.e., “oligopotence” or “multipotence”) may suffice for many therapeutic indications. Furthermore, challenges still remain with all forms of pluripotent cells, whether they be human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) or newer induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells: (i) efficiently generating a homogeneous cell population while excluding cells of undesired lineages; and (ii) eliminating tumorigenic potential. For example, treatment of a neurologic disease might not require reprogramming back to the pluripotent state only to then attempt generation of pure neural lineages. It might be more prudent and efficient to start with cells firmly within the neural lineage, endow them with self-renewal to permit extensive expansion ex vivo while deferring terminal differentiation, and then reverse those actions upon engraftment to insure safety.

Myc is likely to remain the only required gene if one does not reprogram back to pluripotence. (Sox 2 is already expressed in neural progenitors.) Although not entirely necessary (4, 5), myc increases efficiency of reprogramming (4, 6, 7) and is the one gene consistently highly expressed in all reprogrammed colonies (7). The Myc family of transcription factors are well-established regulators of G1 progression, driving cells into S phase by mechanisms impacting cyclin-dependent kinase (Cdk) activity. They confer self-renewal, repress differentiation genes, and hence, link cell cycle regulation to maintenance of potency (8). The risk of myc is its tumorigenic potential (v- and L-myc less so than c-myc), offsetting its great utility in promoting self-renewal. However, if myc’s tumorigenic potential was to be reliably inactivated in vivo, it might be the only gene required to be invoked in vitro to enhance self-renewal of a neural progenitor, preserving its multipotence/oligopotence without inducing pluripotence.

In this study, we explore whether a progenitor cell (rather than a terminally committed cell) with only a single gene for the purpose of sustaining self-renewal might suffice to enhance efficiency, efficacy, and safety of the reprogramming process for specific organ therapy. To test this concept, we conditionally induced self-renewal of a human neural progenitor cell and applied it to a prototypical neural injury (stroke). We envision that this approach may be applicable to progenitor cells from other organs.

Results

Starting Material: Primary Culture of Human Neural Progenitor/Precursor Cells.

We first established primary cultures of cells dissociated from telencephalic tissue of human fetal cadavers (11–14 wk gestational age). When grown in UBC1 serum-free medium (DMEM with high glucose containing human insulin, human transferrin, sodium selenite, hydrocortisone, triiodothyronine, and other nutrients and antioxidants) with supplementary basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), the cultures grew as a monolayer of cells with flat fibroblast morphology intermixed with smaller bipolar cells; the former were mostly glial fibrillary acidic protein-positive (GFAP+), nestin− (consistent with an astrocytic phenotype), whereas the latter were either nestin+ or β-tubulin III+ (consistent with an early neural progenitor/precursor phenotype). The cultures were composed of ~70% nestin+ cells, ~20% GFAP+ cells, and ~9–10% β-tubulin III+ cells; <0.5% of the cells were O4+, galactocerebroside+, or 2′,3′-cyclic nucleotide 3′-phosphodiesterase-positive (CNPase+), suggestive of an oligodendrocytic phenotype. To assess cell division, cultures were incubated in bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) and processed for dual immunoreactivity against antibodies to BrdU/nestin or BrdU/β-tubulin III; >60% of cells on days 7–14 in vitro were dual BrdU+/nestin+, whereas no dual BrdU+/β-tubulin III+ cells were found. (In the absence of tonic exposure to supraphysiological concentrations of mitogens, progenitors in these primary cultures did not sustain self-renewal.)

Transduction of Regulatable myc into Human Neural Progenitor/Precursor Cells.

Replication-incompetent amphotropic infection with a retroviral vector, based on a Maloney murine leukemia viral (MMLV) backbone, was carried out on the primary dissociated human telencephalic cells described above. It was highly likely that some nestin+ proliferative cells, i.e., the neural progenitor cell population in the dish, would integrate the provirus. The culture was first infected with a tetracycline (Tet)-response regulator vector, and infectants were selected by resistance to G418 (300 μg/mL). Selected clones were then infected with a retroviral vector encoding v-myc, an isoform of myc (9, 10) (SI Materials and Methods).

Infectants were then selected for resistance to hygromycin (200 μg/mL). During the selection with antibiotics (i.e., dual resistance to both G418 and hygromycin), much cell death occurred. Colonies of phase-dark bipolar or polygonal cells with short processes began to appear (Fig. 1 A, A).

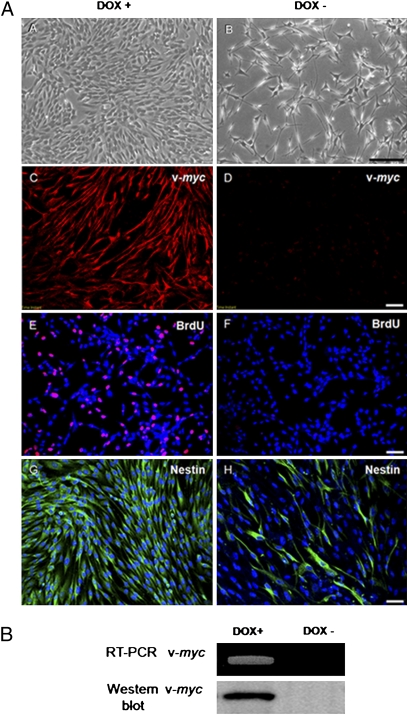

Fig. 1.

Clonal human neural progenitor cells induced to become self-renewing by conditional expression of a single “stemness” gene. (A) Dox-regulated expression of myc (isoform v-myc) and cell proliferation. (A and B) Phase contrast microscopy of cells grown in presence (+) or absence (–) of Dox for 7 d. In Dox, cells are bipolar or polygonal with short processes; in Dox–, they extend long processes. (C and D) Immunofluorescence staining for the v-myc gene product. In Dox− (differentiation-inductive conditions), the cells do not express v-myc protein. (E and F) Immunofluorescence staining for BrdU (red) of cells grown in Dox+ or Dox− media for 12 h. In Dox−, few if any cells incorporate BrdU, i.e., are not mitotically active. [Nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue)]. (G and H) Immunostaining for nestin (green). In Dox+, virtually all of the cells express nestin, a neural stem/progenitor marker, whereas in the Dox– medium, fewer cells express nestin, indicating that a majority of the cells are now differentiating—primarily into neurons (see Fig. 2) and, to a lesser extent, glia. [Nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue)]. (Scale bars, A–D, 100 μm; E–H, 50 μm.) (B) RT-PCR for v-myc and Western blot analysis for v-Myc. Transcripts and the gene product of v-myc are demonstrated in cells grown for 7 d under self-renewing, proliferative conditions (Dox+), but are absent under differentiation-inductive conditions (Dox–). Expression of the "self-renewal" gene myc in HB2.G2 cell is well regulated and does not adversely alter the karyotype (Fig. S1).

Isolation of Clonal Lines of Regulatable myc-Expressing Induced Self-Renewing Human Neural Progenitor Cells.

Cell lines (collectively designated as “HB2 cells”) were isolated by limiting dilution and their clonal identity confirmed by presence on Southern blot of a single retroviral insertion site in all members of the population. A representative clonal cell line, “HB2.G2,” is presented here in detail but reflects the characteristics of all clones so generated (Fig. 1). With doxycycline (Dox+) in the growth medium, HB2.G2 cells expressed nestin (Fig. 1 A, G), suggesting that they were undifferentiated. Similarly, all Dox+ HB2.G2 cells were immunopositive for the v-myc gene product, whereas in the absence of Dox, v-myc expression was completely inactivated (Fig. 1 A, C compared with D). RT-PCR confirmed presence of v-myc mRNA, and Western blot showed the v-myc gene product in Dox-containing medium; in the absence of Dox, both message and protein were undetectable (Fig. 1 B, A). Coincident with v-myc inactivation, the cells ceased dividing, became phase bright, and began extending long processes. In the presence of Dox in vitro, 70 ± 15.6% of HB2.G2 cells had incorporated BrdU (after a 12-h incubation), but without Dox, only 6 ± 5% did so (Fig. 1 A, E compared with F). Doubling time for HB2.G2 cells, investigated by cell counts at 12, 24, 48, and 72 h, indicated mitosis every 24.2 h. (As a control against attributing these effects to nonspecific retroviral integration, neural progenitors transduced with a vector encoding only the lacZ reporter gene did not evince these behaviors. As a control against attributing these properties to integration of a provirus within a particular “hot spot” in the cell's genome, all the “induced conditional self-renewing progenitor (ICSP) cell” clones—each differing in integration site because retroviral insertion is essentially random—possessed these same properties.)

Cytogenetic analysis of HB2.G2 cells showed a normal human 46XX karyotype (Fig. S1).

Neuronal Differentiation of HB2.G2 Conditionally Induced Self-Renewing Human Neural Progenitor Cells.

HB2.G2 cells were examined for expression of CNS cell-type markers in Dox+ and Dox− media containing 10 ng/mL of bFGF (Fig. 2). In both conditions, whether proliferative or nonproliferative, HB2.G2 cells expressed ABCG2 or nestin, undifferentiated state markers (Fig. 2A). Musashi 1, an even more immature neural marker, however, was expressed only under Dox+ conditions and was absent under Dox– conditions. Low level expression of NF-L [low molecular weight (MW) neurofilament], a marker for early immature neurons, was observed in both Dox+ and Dox– media. Expression of β-tubulin III, another marker for immature neurons, increased markedly in Dox– media, whereas its expression was low in Dox+. NF-M (medium MW), NF-H (high MW), and MAP2—markers for more mature neurons—were detected only in HB2.G2 cells grown in the Dox– conditions (Fig. 2A). GFAP (a neural stem/progenitor cell marker when it coexpresses nestin and an astrocyte marker when expressed alone) was present under both conditions, but the emergence of MBP (a maturing oligodendrocyte-specific marker) was evident only in the absence of Dox (Fig. 2A).

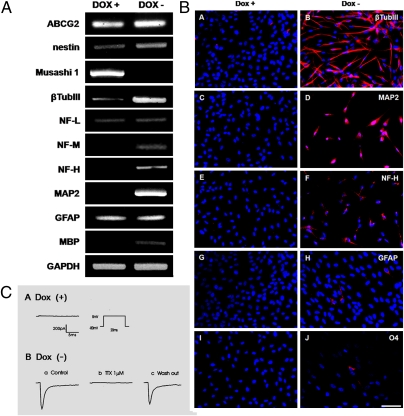

Fig. 2.

Differentiation profile of HB2.G2 neural ICSP cells. Neuronal differentiation appears somewhat more prominent than glial differentiation, consistent with the typical default fate of most normal neural progenitors upon exiting the cell cycle. (A) Analysis by RT-PCR of ICSP cells when self-renewal is inactivated in the absence of Dox. Transcripts of immature neural markers (ABCG2, nestin, and Musashi1) as well as of cell type-specific markers—for neurons (β-tubulin III, NF-L, NF-M, and NF-H), astrocytes (GFAP), and oligodendrocytes (MBP)—were determined in cells grown in Dox+ or Dox− media for 3 d. GAPDH was an internal control. (B) Immunocytochemical analysis of ICSP cells when self-renewal is inactivated in the absence of Dox. Immunostaining is shown for cardinal neuronal and glial markers (red) in cells grown in Dox+ or Dox– media for 7 d: β-tubulin III (A and B), MAP2 (C and D), and NF-H (E and F) for neurons; GFAP (G and H) for astrocytes; and O4 (I and J) for oligodendrocytes. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). (C) Whole cell patch-clamp recordings of HB2.G2 ICSP cells in Dox+ and Dox− media. (A) In Dox+ (self-renewing conditions), no sodium currents were present, as recorded with depolarization pulses to 0 mV from a holding potential of 80 mV. (B, a) Representative Na+ currents from cells in Dox− differentiation-inductive conditions. (b) Tetrodotoxin (TTX) at 1 μM blocked inward currents. (c) Recovery of Na+ currents after wash out of TTX.

Corroborating the RT-PCR studies in Fig. 2A, immunocytochemical analysis showed a similar expression pattern of neural cell-type markers by HB2.G2 cells (Fig. 2B), with 92.5 ± 1.5% β-tubulin III+ under Dox– conditions, and only 23.5 ± 2.5% in Dox+ (Fig. 2 B, A compared with B). In Dox+, no cells stained for MAP2 or NF-H (Fig. 2 B, C–F); however, 7 d after removal of Dox, 79.4 ± 2.8% of the cells were immunopositive for NF-H and 81.7 ± 1.1% for MAP2. Expression of several neurotrophic factors is documented in Fig. S2.

Immunocytochemically identifiable glial cells were less abundant than neurons (Fig. 2 B, G–J). Despite a prominent RT-PCR amplification product for GFAP, <5% of GFAP immunopositive cells and <1% of O4 immunopositive cells (the latter suggestive of oligodendrocytes) were detectable in the absence of Dox—typical profiles for human neural stem cells (hNSCs) in the absence of specific glia-promoting agents (10). No glial cells of either type were seen in Dox+ media.

Thus, under these in vitro differentiation conditions, this “conditional induced self-renewing human neural progenitor cell” line is predisposed more toward neuronal than glial phenotypes, consistent with the well-accepted notion that neuronal differentiation is a default path for neural progenitor cells, particularly in nonconfluent cultures. Importantly, no cells of any non-neuroectodermal lineages were evident under any conditions.

Electrophysiological Assessment of HB2.G2 Cells.

Electrophysiological properties of differentiated HB2.G2 cells were further studied by whole-cell voltage clamping after growth in proliferative self-renewing (Dox+) and differentiation-inductive (Dox–) conditions (Fig. 2C). Dox+ HB2.G2 cells exhibited virtually no sodium currents (n = 9), but upon removal of Dox, substantial numbers of sodium currents were observed (n = 11) and were blocked by tetrodotoxin (1 μM). Concomitant with sodium current induction, regenerative action potentials were observed in HB2.G2 cells following growth in the absence of Dox.

Survival, Integration, and Differentiation of HB2.G2 Cells in Immature Normal Rat Brain.

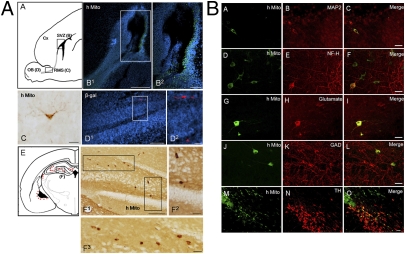

We next tested the responsiveness of the HB2.G2 clone to normal developmental cues in vivo. The cells were identified with a human mitochondria-specific antibody (hMito). At 2 wk following transplantation into the lateral ventricles of newborn rats, HB2.G2-derived cells had integrated into the germinal subventricular zone (SVZ) and had migrated into subcortical brain parenchyma (Fig. 3 A, A–C). hMito+ cells were found in the outer granular layer of the olfactory bulb, indicating that some HB2.G2 cells had migrated along the rostral migratory stream (RMS) to their appropriate developmental target, where a small number had differentiated appropriately into granule cell neurons (Fig. 3 A, D). Additional HB2.G2 cells had migrated appropriately to the hippocampus (Fig. 3 B, E and F). The neuronal phenotype of donor-derived cells was supported by double immunostaining for hMito and neuron-specific markers (Fig. 3B). hMito+ HB2.G2 cells not only expressed the mature neuronal markers MAP2 and NF-H (Fig. 3 B, A–F) but also the neurotransmitter-related markers glutamate and GAD (the synthetic enzyme for GABA), suggestive of at least partial differentiation into glutamatergic and GABAergic interneurons (Fig. 3 B, G–L). When implanted into the developing substantia nigra, HB2.G2 cells expressed tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) 4 wk after transplantation (n = 3 rats) (Fig. 3 B, M–O). Only neural lineage markers were expressed; no non-neuroectodermal lineages or tumors were generated for at least 20 wk, the longest interval examined (Fig. S3).

Fig. 3.

Nontumorigenic engraftment, migration, and neural differentiation of ICSP cells following transplantation. In vivo, Dox is not present and hence, self-renewal is not active. (A) Survival and migration of HB2.G2 ICSP cells following intraventricular transplantation into newborn rat brain. The engrafted cells were detected by immunostaining with antibodies specific either for human mitochondria (hMito) or β-galactosidase (β-gal). A schematic sagittal section view of newborn rat forebrain 7 d after transplantation of HB2.G2 ICSP cells (A), showing HB2.G2-derived cells in the germinal SVZ adjacent to the rostral part of the lateral ventricle (B), and in the RMS (D). B2 and D2 are enlargements of the boxed areas in B1 and D1. An HB2.G2 cell with a typical mature granule neuron morphology (hMito+) is found in the olfactory bulb 2 wk posttransplantation (C). A schematic coronal view of a rat brain (E) shows the distribution of hMito+ HB2.G2-derived cells at 2 wk posttransplantation. The hMito+ HB2.G2 cells transplanted intraventricularly earlier are seen to have migrated to the hippocampus (within E, note red cells in box F). F1 is an enlargement of the boxed area F in E. F2 and F3 are magnified views of the boxed areas in F1. (Scale bars in B1, D1, and F1, 200 μm; B2 and D2, 100 μm; and C, F2, and F3, 50 μm.) (B) Immunohistological analysis of differentiation fate in vivo of HB.G2 ICSP cells in rat brain following neonatal intraventricular transplantation 2 wk earlier. Differentiation of the cells toward a neuronal phenotype is suggested by dual staining for hMito+ (green) and the following neuronal markers: MAP2+ (red) (A–C); NF-H+ (red) (D–F); glutamate (red) (consistent with a glutamatergic interneuronal phenotype) (G–I); and GAD+ (red) (consistent with a GABAergic interneuronal phenotype) (J–L). Four weeks following transplantation of ICSP cells into adult substantia nigra, occasional TH+ (red) donor-derived cells were, nevertheless, surprisingly detected (M–O). (Scale bar, 50 μm.)

Transplantation of HB2.G2 Cells Improves Function in Rats with Hemorrhagic Stroke.

A rodent model of intracerebral hemorrhagic (ICH) stroke provided proof of principle that HB2.G2 cells, in which self-renewal was stringently inactivated in vivo, can be safely and effectively transplanted into the brains of adult animals with neurological dysfunction and help mediate functional recovery without tumor formation, deformation, or the emergence of inappropriate cell types. The ICH rats receiving HB2.G2 cells showed improved behavioral performance on the rotarod compared with the PBS sham-transplanted control group (Fig. 4 A, A) and marked improvement in the limb placement test (Fig. 4 A, B), effects that persisted for the 2-mo period until histological analysis of the brains. The mechanisms underlying improvement are elaborated in Discussion.

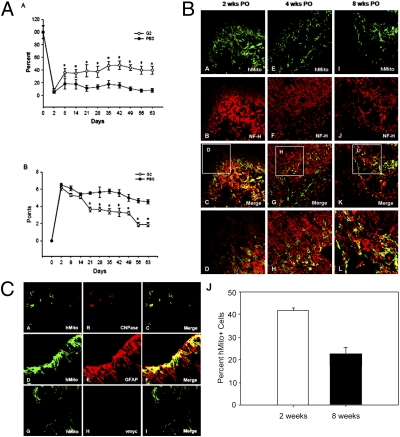

Fig. 4.

Behavioral improvement following safe engraftment and integration of ICSP cells into an adult rat model of ICH stroke. (A) Functional tests of adult rats subjected to stroke followed by intracerebral transplantation of HB2.G2 ICSP cells. (A) In the rotarod test, ICH-lesioned rats receiving HB2.G2 cells showed improved performance from 1 to 9 wk compared with control animals receiving PBS. *P < 0.05. (B) In the limb placement test, ICH-lesioned rats receiving HB2.G2 cells showed improved performance from 3 to 9 wk posttransplantation. *P < 0.05. (B) Immunohistochemistry suggests the presence of donor-derived neurons. Three each of ICH-lesioned adult rats were killed at 2, 4, and 8 wk posttransplantation (Left, Center, and Right columns, respectively). Coronal sections of their brains were double labeled with anti-hMito antibody (green) (A, E, and I) and anti–NF-H antibody (red) (B, F, and J); merged images are shown in C, G, and K; the boxed area in each merged image is shown at higher magnification in D, H, and L, respectively. Engrafted cells that differentiated toward a neuronal phenotype show yellow fluorescence. (C) Double immunofluorescence staining of engrafted HB2.G2-derived cells in ICH-lesioned adult rat brain 4 wk posttransplantation suggests the presence of donor-derived glia and down-regulation of myc. (A–F) In brain sections from an ICH-lesioned adult rat, HB2.G2 cells double labeled with anti-hMito (green) (A and D) and anti-CNPase (red) (B) or anti-GFAP (red) (E) had differentiated toward oligodendrocytic (C) or astrocytic (F) lineages, respectively. (G–I) Negative v-myc immunoreactivity (red) (H) in hMito+ engrafted (G) HB2.G2-derived cells in the absence of Dox—the typical condition in vivo in the brain. Accordingly, the neural progenitors do not undergo mitosis, thereby precluding tumor formation or brain deformation. (J) Survival of engrafted HB2.G2-derived cells 2 and 8 wk posttransplantation in ICH-lesioned adult rat brains. The percentage of surviving cells per mm2 of engrafted brain was 41.6% at 2 wk and 20.2% at 8 wk; functional improvement persisted until at least 20 wk (study termination).

Transplanted HB2.G2 Cells Migrate to ICH Lesions and Differentiate into Neurons and Glia.

Immunostaining with the hMito antibody demonstrated preferential migration of grafted HB2.G2 cells toward the perihematomal border by 1–2 wk posttransplantation. Double labeling with hMito/NF-H antibodies revealed a large number of donor-derived cells differentiating toward a neuronal phenotype with extended processes at the lesion site (Fig. 4 B, A–D), and progressively by 4 and 8 wk posttransplantation, hMito+/NF-H+ cells in the HB2.G2 transplanted group displayed a more mature neuronal morphology with long processes (Figs. 4 B, E–L). Also, many grafted cells at the perihematomal border area were hMito+/GFAP+, indicating that some cells of the HB2.G2 clone had differentiated toward an astrocytic lineage (Fig. 4 B, D–F). Finally, some hMito+/CNPase+ cells (suggestive of an oligodendrocytic lineage) were present within the lesion sites (Fig. 4 C, A–C).

Importantly, at 4 and 8 wk posttransplantation, no v-myc+ cells, including dual hMito+/v-myc+ cells, were detected by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 4 C, G–I), indicating that v-myc expression was inactivated in vivo in the Dox– environment. No tumors, deformations, or donor-derived nonneural cells were seen at 2, 4, 8, 12, and 20 wk (Fig. S3).

Survival of Engrafted HB2.G2 Cells in ICH Rat Brain.

The total number of hMito+ HB2.G2 cells in brain sections from ICH animals was determined by unbiased stereological analysis at 2 and 8 wk posttransplantation (Fig. 4 C, J). At 2 wk, 83,100 ± 1,140 cells (41.6 ± 1.7% of the initial implant of 200,000 cells) and at 8 wk, 40,340 ± 2,850 cells (20.2 ± 2.5% of the initial implant) had survived. (Because the HB2.G2 cells grow as an adherent monolayer, it is necessary to remove them from the culture dish by trypsin digestion for transplantation; this procedure evidently produces some cell death, so that although 200,000 HB2.G2 cells were prepared for transplantation, the actual number of live cells implanted, as determined by trypan blue exclusion immediately before transplantation, was 20% lower, i.e., 160,000–170,000 cells. Taking this finding into account, the survival of grafted HB2.G2 cells in the ICH animals would be 51.9% at 2 wk posttransplantation and 25.2% at 8 wk.) HB2.G2 cells survived to at least 20 wk posttransplantation (Fig. S4). It bears noting that this survival, which was sufficient to impart a behavioral improvement in the ICH rats (mechanism discussed below), was performed without immunosuppression. Although addition of immunosuppressive drugs might have increased grafted cell survival, the achievement of therapeutic efficacy with safety while avoiding such pharmacological complications was appealing. There was no evidence of an inflammatory immunorejection reaction by the host to the presence of human cells.

Discussion

In the rapidly evolving field of cell reprogramming, choice of the best starting cell in any particular experimental or therapeutic situation or the extent to which a given cell needs to be transported back to a more primitive state remain unsettled. iPS cells offer the advantage of a genetic match to the patient from whom the skin cells were obtained, minimizing prospects of immunological rejection. However, for diseases of a particular organ system where lineage-restricted progenitors are available, reprogramming of an end-committed cell from an irrelevant tissue (e.g., a dermal fibroblast) all of the way back to pluripotence and then efficiently, specifically, and uniformly to an alternate organ identity may unnecessarily add time, effort, genes, and manipulations, increasing the risk of neoplasia, undesired cell types, and other sources of morbidity. Starting with a precursor/progenitor cell from the organ of therapeutic interest may be preferable. We tested this hypothesis in the CNS where progenitor/precursor cells are well known. Our ICSP cells proved to be regulatable so as to offset their limited capacity for self-renewal. They matched the predilection of other neural progenitor cell preparations to become neuronal (10) and to be effective in clinical disease models (10–16). Although, in these experiments, the neural progenitors were obtained from the brain, they could likely be obtained from such more accessible sources as olfactory neuroepithelium or skin. Also, given the absence of immunorejection, one ICSP line could serve many recipients.

To summarize, we have established stable clonal ICSP cells—in other words, lines in which the starting cell is a non–self-renewing progenitor from the target organ of ultimate therapeutic interest (rather than a terminally differentiated unrelated cell) in which expression of a gene stimulating self-renewal is under the conditional control of a tightly regulatable promoter. The gene is myc, well established as pivotal in endowing self-renewal competence to somatic cells in transition to a pluripotent state. When myc is omitted because of its potential oncogenic risk, efficiency of reprogramming is significantly impaired. In the present study, we established conditional self-renewing clonal neural progenitor cell lines (representative clone HB2.G2 was presented here) in which expression of the isoform v-myc is regulated by a Tet-on gene expression system. (In previous studies, we established that v-myc was the most effective and safest isoform of myc for these purposes (9). Expression of myc was activated only in the presence of the Tet derivative Dox, resulting in enhanced cell proliferation, but not malignant growth. (The cells still respected normal growth controls, i.e., were contact inhibited, did not grow in soft agar, and had a normal karyotype). These ICSP cells expand readily with a doubling time of 24.2 h in the presence of Dox, thus providing an accessible, renewable, homogenous, reliable, abundant, safe, effective, and practical source of human CNS precursors. In the absence of Dox, myc was no longer expressed, cell proliferation ceased, and differentiation into CNS cell types rapidly ensued. Such actions were observed not only in vitro but also in rats in vivo both under normal developmental conditions (where they engrafted, migrated, and differentiated appropriately) and following stroke in the adult, a model providing proof of principle that these ICSP cells, with proliferation stringently regulated, can be safely and effectively transplanted into injured brains without tumor formation or deformation. In short, these ICSP cells, which now behave transiently like multipotent somatic stem cells, embody the benefits of rapid scale-up offered by hESCs or iPS cells, but without their risks (teratoma formation or emergence of a premalignant state; emergence of nonneural cell types inappropriate to the brain or other types of uncontrolled heterogeneity; and phenotypic or genomic instability). Furthermore, a degree of plasticity (often dangerous in pluripotent cells and unattainable in end-differentiated somatic cells) is preserved, which facilitates engraftment, integration, and multi-neural cell-type reconstitution. The potential clinical advantages of such conditionally induced progenitor cells are summarized in Table S1.

The induction of conditional self-renewal in progenitor cells with a single gene is far more efficient than has been achieved with iPS cells, although improvements in the iPSC methodology are being sought intensively (1–3). ICSP cells can be generated with an efficiency of 33% or better, with colonies forming within 1 wk and sufficient cells for multiple transplants within 2 wk.

Role and Control of myc.

The role of myc in inducing pluripotence in end-differentiated cells, and its conditional deletion in the neural stem cells of transgenic mice, causing a failure of normal brain growth attributable to disruptions in a cell cycle regulatory program (17), have led to recognition of myc as a “stemness” gene, both promoting self-renewal and holding terminal differentiation in abeyance (17–21). Its precise mechanism of action has been attributed to one or a combination of the following: (i) Inducing a cell-cycle gene expression program necessary specifically for self-renewal and inhibition of differentiation by repression of cdk inhibitors and stimulation of D cyclins in stem cell populations (19–21); it also may play a nontranscriptional role in initiation of DNA replication (17–21). (ii) Maintaining key components of transcriptionally active chromatin required for self-renewal, pluripotency, and suspension of differentiation (including histone H3 and H4 acetylation as well as H3 methylation at lysine 4) (19–21).

Furthermore, previous work on v-myc–enhanced transplanted cells has documented that extra copies of myc are spontaneously and constitutively inhibited by normal developmental mechanisms of the transplant recipient, just as endogenous c-myc is down-regulated in CNS precursors (9, 10, 18–21). The presence of a regulatable promoter adds an extra level of safety and control.

Controlled expression of myc in ICSP cells with a Tet-on system obviates the risk of tumorigenesis in vivo following transplantation. HB2.G2 cells, or other such cells, (i) precisely regulate proliferation in vitro (for scale-up), however (ii) cease dividing once transplanted into CNS, while retaining the ability to differentiate into neurons and glia in response to local microenvironmental cues. By comparison, previous studies (22) have indicated that a Tet-off–v-myc gene expression system was “leaky,” so that v-myc mRNA and protein were found in newly generated cell lines. Also, cell lines generated via the Tet-off system grew slowly with a doubling time of >80 h (22). More concerning, Tet-off cells might continue to proliferate after transplantation into the brain where continuous Dox exposure is not feasible. In contrast, the HB2.G2 ICSP cells bear a Tet-on system, with Dox-promoting expression of v-myc solely in vitro; the absence of Dox in vivo renders v-myc mRNA and protein undetectable (Fig. 2).

Neurobiological Fidelity of Human Neural ICSP Cells.

In vitro, HB2.G2 cells under Dox− conditions show a predilection for neuronal, more than glial, differentiation, consistent with the typical default behavior of most normal neural progenitors upon exiting the cell cycle. Their properties include expression of neuronal cytoskeletal proteins (NF-L, M, and H, β-tubulin III and MAP2), ion channels (for Na+, K+, and Ca2+), neurotransmitter synthesizing enzymes (ChAT, GAD, and TH) and neurotransmitters (GABA and glutamate). In addition, such differentiated HB2.G2 cells expressed tetrodotoxin-sensitive Na+ currents and could spike action potentials, critical hallmarks of functional neurons.

In vivo, HB2.G2 cells migrated along at least two different pathways after implantation into the cerebral ventricles of neonatal rats: (i) along the RMS to olfactory bulb and (ii) into hippocampus, as reported for other neural progenitors (10–12, 14), hence suggesting that fundamental progenitor properties are unaffected by the transgene and its Tet regulatory system. Although the precise mechanism is unclear by which HB2.G2 hNSCs migrate extensively yet selectively to pathological lesions, it likely involves, as with other neural progenitors, chemoattractant signals produced at CNS injury sites, such as stromal cell-derived factor 1α (SDF1α) (12), vascular endothelial cell growth factor (VEGF) (11, 13), or stem cell factor (SCF) (11, 13). Other cytokines with important functions in CNS development, including bFGF, EGF, and TGFα, also contribute to ischemia-induced proliferation and migration of neural progenitor cells. HB2.G2 cells express CXCR4 (the receptor for SDF1α), VEGFR1, VEGFR2, and c-kit, again suggesting that conditionally augmenting self-renewal via myc in these cells does not alter their fundamental neural progenitor properties.

It bears emphasis that we do not claim functional improvement in the adult rat with stroke has resulted from cell replacement. The predominant mechanism was likely via the “chaperone effect,” (14, 15) the HB2.G2 cells providing trophic and neuroprotective support to endangered host cells. Whatever the underlying mechanism (beyond the scope of this report), ICSP cells invoke it with a safety and efficacy equal to that of other progenitor cell populations.

All our animal experiments were performed without addition of an immunosuppressive agent, consistent with previously reported immunotolerance for NSCs in transplantation studies (9, 14). Whereas immunosuppression might increase survival of donor-derived cells, we, by intent, wished to determine how well the cells would persist, differentiate, and impact function without the inevitable side effects, health risks, and confounders imposed by the chronic use of immunosuppressants, as one would ideally prefer in human patients. Our results suggest that a sufficient impact may be attainable under this more desirable treatment regime.

Therefore, induced conditional self-renewing progenitors will likely be valuable for future studies in developmental biology, drug discovery, and derivation of stem cell-based therapies.

Conclusions

Human neural ICSP cells—self-renewing in vitro and differentiating in vivo within a given organ's range of lineages—offer an attractive alternative to pluripotent cells (which require additional manipulation to ensure safety and efficacy), or to cellular “spheres” isolated from a given organ (which are heterogeneous, of dubious clonality, and difficult to transplant, engineer, synchronize, scale-up, and render uniform and invariant from experiment to experiment for dose–response studies, drug discovery, or high-throughput screening of small molecules (23). Usually, the number of neural progenitors obtained from a human brain is small, their expansion slow, and the risk of cell line senescence sufficiently prevalent that routine clinical transplantation is difficult. Therefore, for the CNS, ICSP cells—rapidly expandable and standardizable in vitro as monolayers—provide an efficient, expeditiously generated source of abundant, uniform, well-characterized, safe, therapeutically effective neural cells for transplantation—possibly preferable to hESCs and iPS cells in this regard (24).

In conclusion, we believe this strategy of inducing conditional self-renewal within lineage-bounded progenitor cells (for in vitro expansion after which self-renewal is permanently inactivated in vivo) may serve broadly as a safe, effective, and practical method for optimizing the revolutionary insights gained of late from the ability to reprogram cells to an earlier developmental state, but with the advantage of requiring fewer genes and fewer intervening steps in the derivation of therapeutically useful cells for a given organ.

Materials and Methods

A replication-incompetent retroviral vector was used to transduce v-myc transcribed from the RevTet-on system into primary human fetal telencephalic ventricular zone cells in culture, from which several clones were isolated. Clone HB2.G2 was then transfected with an adenovirus encoding lacZ. Please see SI Materials and Methods for details of clone genesis and subsequent cytogenetic, RT-PCR, Western blot, immunohistochemical, electrophysiological, and transplantation procedures. Most reagents and methods were previously described (16).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank I. Singec and D. Wakeman for their insights. This work was supported by grants from the National RD Program for Cancer Control, Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare (08203103-22650), and the Canadian Myelin Research Initiative (to S.U.K.); from NS059770, Sanford Children's Research Center, and California Institute for Regenerative Medicine; and from the A-T Children's Project and the Nancy Lurie Marks Family Foundation (to R.L.S.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1019743108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Yamanaka S, Blau HM. Nuclear reprogramming to a pluripotent state by three approaches. Nature. 2010;465:704–712. doi: 10.1038/nature09229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanna JH, Saha K, Jaenisch R. Pluripotency and cellular reprogramming: Facts, hypotheses, unresolved issues. Cell. 2010;143:508–525. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zaehres H, Kim JB, Schöler HR. Induced pluripotent stem cells. Methods Enzymol. 2010;476:309–325. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(10)76018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakagawa M, et al. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells without Myc from mouse and human fibroblasts. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:101–106. doi: 10.1038/nbt1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wernig M, Meissner A, Cassady JP, Jaenisch R. c-Myc is dispensable for direct reprogramming of mouse fibroblasts. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:10–12. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meissner A, Wernig M, Jaenisch R. Direct reprogramming of genetically unmodified fibroblasts into pluripotent stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:1177–1181. doi: 10.1038/nbt1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park IH, et al. Reprogramming of human somatic cells to pluripotency with defined factors. Nature. 2008;451:141–146. doi: 10.1038/nature06534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh AM, Dalton S. The cell cycle and Myc intersect with mechanisms that regulate pluripotency and reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Snyder EY, et al. Multipotent neural cell lines can engraft and participate in development of mouse cerebellum. Cell. 1992;68:33–51. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90204-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flax JD, et al. Engraftable human neural stem cells respond to developmental cues, replace neurons, and express foreign genes. Nat Biotechnol. 1998;16:1033–1039. doi: 10.1038/3473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeong S-W, et al. Human neural stem cell transplantation promotes functional recovery in rats with experimental intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2003;34:2258–2263. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000083698.20199.1F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Imitola J, et al. Inflammation's other face: Directed migration of human and mouse neural stem cells to site of CNS injury by the SDF1a/CXCR4-dependent pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:18117–18122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408258102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim SK, et al. Human neural stem cells target experimental intracranial medulloblastoma and deliver a therapeutic gene leading to tumor regression. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:5550–5556. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee J-P, et al. Stem cells act through multiple mechanisms to benefit mice with neurodegenerative metabolic disease. Nat Med. 2007;13:439–447. doi: 10.1038/nm1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Redmond DE, Jr, et al. Behavioral improvement in a primate Parkinson's model is associated with multiple homeostatic effects of human neural stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:12175–12180. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704091104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee HJ, Lim IJ, Lee MC, Kim SU. Human neural stem cells genetically modified to overexpress brain-derived neurotrophic factor promote functional recovery and neuroprotection in a mouse stroke model. J Neurosci Res. 2010;88:3282–3294. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knoepfler PS, Cheng PF, Eisenman RN. N-myc is essential during neurogenesis for the rapid expansion of progenitor cell populations and the inhibition of neuronal differentiation. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2699–2712. doi: 10.1101/gad.1021202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cartwright P, et al. LIF/STAT3 controls ES cell self-renewal and pluripotency by a Myc-dependent mechanism. Development. 2005;132:885–896. doi: 10.1242/dev.01670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knoepfler PS. Why myc? An unexpected ingredient in the stem cell cocktail. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:18–21. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dominguez-Sola D, et al. Non-transcriptional control of DNA replication by c-Myc. Nature. 2007;448:445–451. doi: 10.1038/nature05953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knoepfler PS, et al. Myc influences global chromatin structure. EMBO J. 2006;25:2723–2734. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oberst C, Hartl M, Weiskirchen R, Bister K. Conditional cell transformation by doxycycline-controlled expression of the MC29 v-myc allele. Virology. 1999;253:193–207. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singec I, et al. Defining the actual sensitivity and specificity of the neurosphere assay in stem cell biology. Nat Methods. 2006;3:801–806. doi: 10.1038/nmeth926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roy NS, et al. Functional engraftment of human ES cell-derived dopaminergic neurons enriched by coculture with telomerase-immortalized midbrain astrocytes. Nat Med. 2006;12:1259–1268. doi: 10.1038/nm1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.