Abstract

Information seeking and scanning refers to active pursuit of information and passive exposure, respectively. Cancer (ca) is the leading cause of mortality for Asian Americans, yet little is known about their ca information seeking/scanning behaviors (SSB). We aimed to evaluate ca SSB among older limited English proficient (LEP) Vietnamese immigrants, compared to Whites/African Americans. 104 semi-structured interviews about breast/prostate/colon ca SSB (age 50–70) were conducted in English and Vietnamese, transcribed, and coded for frequency of source use, active/passive nature, depth of recall, and relevance to decisions. Higher SSB was associated with ca screening. In contrast to non-Vietnamese, SSB for Vietnamese was low. Median # of ca screening sources was 2 (vs. 8–9 for non-Vietnamese). They also had less seeking, lower recall, and less decision-making relevance for information on colon ca and all ca combined. Overall, Vietnamese had lower use of electronic, print, and interpersonal sources for ca SSB, but more research is needed to disentangle potential effects of ethnicity and education. This study brings to light striking potential differences between ca SSB of older LEP Vietnamese compared to Whites/African Americans. Knowledge of SSB patterns among linguistically isolated communities is essential for efficient dissemination of cancer information to these at-risk communities.

For adults age 50 and older, information about cancer holds particular relevance because of the age-related increase in risk. Patients and other community members acquire cancer information through a variety of channels, and these channels can impact the manner in which cancer information is conceptualized and used (Case, Andrews, Johnson, & Allard, 2005; Shim, Kelly, & Hornik, 2006). Methods of knowledge acquisition can be categorized into two distinct categories: “information scanning” and “information seeking” (Niederdeppe et al., 2007). Niederdeppe and colleagues describe information scanning as an umbrella term encompassing information acquired through customary exposure to knowledge sources, information encountered incidentally, or information acquired through browsing news and other sources, insomuch as the information can be recalled with minimal prompt. They classify information seeking as purposeful endeavors to acquire specific information in a manner transcending customary exposure to knowledge sources. These two definitions of information scanning and seeking are adopted as the operational definitions implemented in this paper. In addition, information seeking and scanning behavior (SSB) can be described further with regard to its breadth (total number of information sources accessed), depth (extent to which information acquired was retained), and relevance to decision-making (impact that the information had on health-related decisions). The concept of SSB is clinically important, because recent evidence from national data suggests a correlation between SSB and cancer screening behavior (Shim, Kelly, & Hornik, 2006).

Multiple factors influence to what extent health information is being accessed by individuals and population subgroups (Johnson, 1997). Several studies have alluded to the influence that cultural background exhibits on health information seeking, at least for Latinos and African Americans (Courtright, 2004; Matthews, Sellergren, Manfredi, & Williams, 2002). One contributing factor is the language barrier that members of some immigrant populations face in the midst of predominately English information sources.

Beyond language, however, cultural incongruities between immigrant populations and the American health system can also impact the extent to which immigrant groups access health information (Grace X. Ma & Fleisher, 2003). For example, some cultures have a strong narrative based communication tradition, often relying heavily on storytelling for the purpose of education rather than entertainment (Miller, Wiley, Fung, & Liang, 1997). In such cultures, the process of sharing and seeking health information may differ from that which is customary in mainstream America. Asian Americans, unlike the majority American culture, may also place greater emphasis on filial piety (Cheng & Chan, 2006) as well as collectivism (as opposed to individualism), conformity, and humility (Kim, Li, & Ng, 2005). Patients from these minority backgrounds often feel that their doctors do not understand their values and have lower satisfaction in their medical care (Ngo-Metzger, Legedza, & Phillips, 2004). Consequently, such patients may be less likely to seek information from healthcare providers.

A study analyzing the disparities between Asian Americans and White Americans in the Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) reported that Asian Americans had lower awareness of institutionalized information sources such as the American Cancer Society and National Institutes of Health, and perceived their cancer risk to be low in comparison to the responses of their white counterparts (G. T. Nguyen & Bellamy, 2006). Additional investigations have suggested that ethnicity can play a determinate role in the selection of the medium through which cancer information is attained (Kakai, Maskarinec, Shumay, Tatsumura, & Tasaki, 2003). Several reports indicate that Asian Americans are more likely to acquire health-related information from interpersonal sources, as compared to white Americans who are more inclined to use print literature or the Internet (Kakai, Maskarinec, Shumay, Tatsumura, & Tasaki, 2003; Lorence, Park, & Fox, 2006).

Vietnamese Americans are among the fastest growing, yet most linguistically isolated, populations of Asian Americans (Woodall et al., 2006). In 2000, Vietnamese Americans were the fourth largest Asian American population in the United States, comprising almost 11% of Asian Americans; within this large population, over 60% speak English less than very well (Reeves & Bennett, 2004). A 2006 study reported that Vietnamese American men are more than twice as likely to use Vietnamese newspapers or magazines than English ones as sources of health information, but this study was not focused on older adults, nor did it address cancer information in particular (Woodall et al., 2006). In addition, like other immigrant groups, linguistically isolated Vietnamese Americans may operate within social, political, or religious sub-communities that maintain ideologies that are largely inconsistent with most American health care practices. For example, such communities (which might be unfamiliar Western preventive health practices while having greater emphasis on the role of fate) could hold negative views about seeking medical care in the absence of symptoms.

This paper describes a study comparing information seeking and scanning behaviors for breast, prostate, and colon cancers between older Vietnamese Americans and the general American population. These cancers are among the most common malignancies in both populations (McCracken et al., 2007). The main aim was to investigate whether ethnicity is a factor in the extent and impact of cancer information acquisition for Vietnamese Americans. We hypothesized that, compared to Whites and African Americans, Vietnamese Americans would access fewer cancer information sources, be less likely to report information seeking, and be more likely to use interpersonal sources as compared to electronic or print sources. Furthers, we hypothesized that individuals who reported more SSB would also report more cancer screening.

Methods

This study is an extension of work published by Niederdeppe and colleagues (Niederdeppe et al., 2007). In brief, data were collected using in-person semi-structured interviews with respondents age 50–70. The initial sample of White and African American participants from the general population described in the paper by Niederdeppe et al was supplemented with additional interviews of Vietnamese American immigrants conducted during the same time frame. Based upon prior experience with this hard-to-reach minority community, we chose to recruit participants for this segment of the study through community-based organizations (CBO’s) serving Vietnamese American communities, rather than using purchased lists of households. Members of marginalized communities are often reluctant to participate in activities unless they are introduced by trusted sources such as CBO’s. This approach has been used by others for similar work (G. X. Ma, Shive, Tan, & Toubbeh, 2002). Vietnamese American participants were recruited from the same geographical boundaries used for the general population sample. Data were collected through semi-structured interviews using the same questions described in the prior work by Niederdeppe et al. However, all questions were translated into Vietnamese and back-translated to assure lexical equivalence; all interviews for the Vietnamese American sub-sample were conducted in Vietnamese. Additional questions specific to the Vietnamese immigrant population were asked at the conclusion of the interview (e.g., English proficiency, immigration year, age at immigration). Further details regarding collection of interview data for the Vietnamese sub-sample are published elsewhere (G. T. Nguyen, Barg, Armstrong, Holmes, & Hornik, 2008). In total, 104 interviews of White, African American and Vietnamese American participants were included in this study.

Men were asked about information seeking and scanning behaviors (SSB) related to colon cancer and prostate cancer, and women were asked about colon cancer and breast cancer SSB. Questions were designed to elicit responses that would distinguish between SSB related to primary prevention and SSB related to screening. Thus, each participant was asked questions using a four-module framework: breast or prostate cancer primary prevention, breast or prostate cancer screening, colon cancer primary prevention, and colon cancer screening.

All interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Vietnamese interviews were then translated into English by a research support company with extensive experience in multilingual project support. The textual data were managed using N6 qualitative research software (QSR International; Doncaster, Victoria, Australia; 2002). The data were coded by multiple reviewers for presence of cancer-related information seeking or scanning behavior (SSB), breadth of SSB, depth of SSB, and relevance to decision-making for cancer primary prevention and screening. Breadth was measured as the number of sources used to seek or scan for a decision. Depth was dichotomized into those who recalled at least general ideas from a source of cancer information and those who did not recall any substantive information from that source. This depth of recall was based purely on self-report, because there was no reliable and feasible way to assess whether each piece of recalled information was actually being remembered in an accurate fashion. Even scientific accuracy of the information described by participants could not be used for this purpose, because there was no guarantee that the original information to which participants had been exposed was scientifically correct from the start. Consequently, depth of recall was based on more contextual features (e.g., the participant mentions several details about the information source and/or about the information that was presented). Relevance to decision-making was determined based upon responses to the question, “Did that information lead you to do anything afterwards?” which was asked whenever participants reported exposure to any cancer-related information.

Further details regarding the data collection procedure, semi-structured interview protocol, coding procedures, and SSB measures are available in previously published papers (G. T. Nguyen, Barg, Armstrong, Holmes, & Hornik, 2008; Niederdeppe et al., 2007). The coded data were analyzed using SPSS 12.0 for Windows (SPSS, Inc.; Chicago, IL; 2003). All of the study materials were approved by the institutional review board of a major university prior to their implementation.

We tested for disparities in overall SSB by comparing racial/ethnic subgroups (White, African American, and Vietnamese American) using the Wilcoxin Rank-Sum test, stratified by information source. Similar analyses were carried out for depth of recall and information relevance to decision making. Comparisons were also made with regard to the number of sources used for each type of decision (breast/prostate/colon cancer primary prevention, breast/prostate/colon cancer screening). In addition, analyses (stratified by cancer type) also evaluated racial/ethnic differences in information seeking, recall, and relevance to decision-making.

In order to test the hypothesis that Vietnamese Americans place more significance on interpersonal sources than on other sources of information, the sources were divided into 3 categories for some analyses: electronic media (television, radio, or the Internet); print media (newspapers, books, and pamphlets); and interpersonal sources (doctors, friends, and family). Once again, the reported use of these grouped sources was analyzed by race/ethnicity.

Finally, we performed logistic regression to identify predictors of 4 outcomes: active seeking of cancer information (all sources combined), use of electronic media for cancer information, use of print media, and use of interpersonal sources. As independent variables, we included race/ethnicity (Vietnamese versus White/African American), education (less than high school versus high school grad), gender, age, and marital status (married versus unmarried). Categorical variables were converted to dummy variables for regression analyses. Due to differences in education between Vietnamese and non-Vietnamese samples, we included an interaction term to test for effect modification.

In the Results, we will present a comparison of the three racial/ethnic groups in a variety of ways: First, we will focus on breadth of SSB (number of sources used for information about primary prevention vs. screening, separated by gender and cancer type). Next, we will present racial/ethnic comparisons for the presence of active information seeking, depth of information recall, and decision-making relevance, stratified by cancer type. Finally, we will break this down to the specific types of cancer information sources, and their relationship with information seeking, depth of recall, and relevance to decision-making. In addition, we will describe self-reported cancer screening (mammogram, PSA, sigmoidoscopy/colonoscopy) in relation to cancer-specific SSB for the full sample and for the Vietnamese American sub-sample alone.

Results

A total of 104 respondents were interviewed for this study. Characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1. The mean age for Vietnamese Americans was slightly older that that of Whites and African Americans, but the difference was not statistically significant. Differences in gender and marital status were also not statistically significant. However, discrepancy in educational status between Vietnamese Americans and the other two groups was statistically significant.

Table 1.

Demographics, by Race/Ethnicity

| Characteristics | White | African American |

Vietnamese American |

p- value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of participants | 63 | 21 | 20 | ||

| Mean age in years (SD) | 59.6 (5.74) |

59.2 (4.78) | 62.6 (6.42) | 0.099 | |

| Percent male | 41.3 | 28.6 | 50.0 | 0.367 | |

| Percent married | 66.7 | 38.1 | 85.0 | 0.127 | |

| Level of education | <.001 | *** | |||

| % less than high school | 0.0 | 4.8 | 70.0 | ||

| % completed high school | 28.6 | 23.8 | 15.0 | ||

| % some college or more | 71.4 | 71.4 | 15.0 | ||

| Year of immigration | - | - | 1979 to 2004 |

||

| Age at immigration, years | - | - | 34 to 65 | ||

| % speaking English very well | - | - | 10.0 |

Key: S.D. = "standard deviation";

significant at 0.05 level,

significant at 0.01 level,

significant at 0.001 level

Vietnamese Americans were considerably less likely to report engaging in cancer information seeking and scanning behaviors (SSB) than Whites and African Americans. Table 2 focuses on the breadth of SSB (median number of sources used) and compares the racial/ethnic groups by behavior type (primary prevention vs. screening), gender, and cancer type. These results demonstrate that Vietnamese Americans uniformly used fewer sources for both primary prevention and screening SSB across all three cancers. All three racial/ethnic groups used substantially more sources for screening than they did for primary prevention. Women generally accessed more sources than men in all groups.

Table 2.

Median number of sources used by a single individual, by race/ethnicity and decision type

| Median number of sources used for SSB |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decision Type | White | AA | Viet | p-value | |

|

Prevention and screening |

|||||

| All cancers | 13 | 11 | 3 | < 0.001 | *** |

| All cancers (female) | 14 | 12 | 3 | < 0.001 | *** |

| All cancers (male) | 11 | 9.5 | 1.5 | < 0.001 | *** |

| Prevention only | |||||

| All cancers | 4 | 4 | 1 | < 0.001 | *** |

| All cancers (female) | 5 | 4 | 1 | < 0.001 | *** |

| All cancers (male) | 3 | 4 | 0 | < 0.001 | *** |

| Breast ca (female) | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0.085 | |

| Prostate ca (male) | 0 | 0 | 0 | < 0.001 | *** |

| Colon ca (female) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0.524 | |

| Colon ca (male) | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0.524 | |

| Screening only | |||||

| All cancers | 8 | 8 | 2 | < 0.001 | *** |

| All cancers (female) | 9 | 8 | 2 | < 0.001 | *** |

| All cancers (male) | 7.5 | 6 | 1 | < 0.001 | *** |

| Breast ca (female) | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0.018 | * |

| Prostate ca (male) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.002 | ** |

| Colon ca (female) | 4 | 3 | 1 | < 0.001 | *** |

| Colon ca (male) | 4 | 4 | 0.5 | < 0.001 | *** |

Key: ca = "cancer"; AA = "African American", Viet = "Vietnamese American";

significant at 0.05 level,

significant at 0.01 level,

significant at 0.001 level

Note: For prostate cancer, median values are identical across race/ethnicities, but means were different, thus accounting for the statistically significant differences between groups.

Table 3 focuses on the remaining dimensions of SSB: presence of active information seeking, depth of recall, and relevance to decision-making. Vietnamese Americans reported less seeking, lower recall, and less information relevance to decision-making for colon cancer, and to a lesser extent for breast and prostate cancer. Comparable results were found for information scanning and SSB for all three cancers. Combining all three cancers, close to 100% of Whites and African Americans could recall general ideas from SSB and found SSB to be relevant to their decision making. In contrast, less than two-thirds of Vietnamese Americans demonstrated recall of cancer information. Similarly, less than two-thirds of Vietnamese Americans cited SSB as relevant to their decision making process.

Table 3.

Percent reporting information seeking, depth of recall and decision relevance, by cancer type

| Category | White | AA | Viet | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Presence of active seeking | |||||

| All ca combined | 60.3 | 61.9 | 15.0 | 0.001 | ** |

| Breast ca | 28.6 | 28.6 | 10.0 | 0.226 | |

| Prostate ca | 19.0 | 9.5 | 0.0 | 0.079 | |

| Colon ca | 39.7 | 38.1 | 10.0 | 0.045 | * |

| Able to recall ca information | |||||

| All ca combined | 98.4 | 100.0 | 55.0 | <0.001 | *** |

| Breast ca | 58.7 | 71.4 | 25.0 | 0.007 | * |

| Prostate ca | 38.1 | 28.6 | 15.0 | 0.145 | |

| Colon ca | 98.4 | 100.0 | 40.0 | <0.001 | *** |

| Relevance to decision | |||||

| All ca combined | 98.4 | 100.0 | 60.0 | <0.001 | *** |

| Breast ca | 55.6 | 61.9 | 30.0 | 0.081 | |

| Prostate ca | 33.3 | 23.8 | 5.0 | 0.041 | * |

| Colon ca | 92.1 | 90.5 | 35.0 | <0.001 | *** |

Key: ca = "cancer"; AA = "African American", Viet = "Vietnamese American";

significant at 0.05 level,

significant at 0.01 level,

significant at 0.001 level

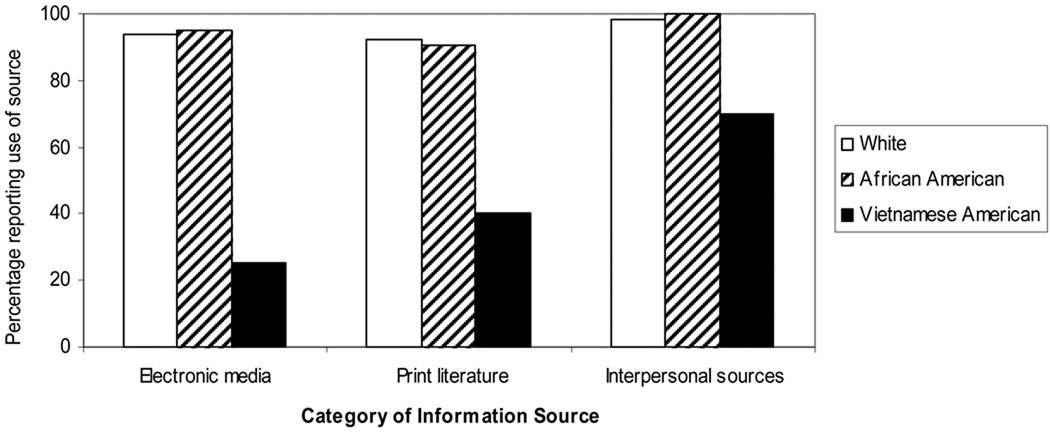

Figure 1 illustrates the types of sources used for SSB. Over 90% of Whites and African Americans reported use of electronic media, print literature, and interpersonal sources for SSB; meanwhile, interpersonal sources were the only category accessed by more than half of Vietnamese Americans. As shown in Table 4, Vietnamese Americans also reported less SSB, lower recall, and less relevance to decision making for each of the individual sources under investigation. Doctors were the most used source of information for respondents of all races/ethnicities, followed closely by friends and family, although the percentage of Vietnamese Americans who accessed these sources was about half that of their counterparts. Television, newspaper, and pamphlet use was reported by the majority of Whites and African Americans, but these sources played a substantially diminished role in the SSB of Vietnamese Americans.

Figure 1.

Use of electronic, print, and interpersonal sources for cancer information seeking and scanning, by race/ethnicity

Table 4.

Sources used, depth of recall, and relevance to decision making

| Percent who used source for any cancer SSB |

Percent able to recall ca info from source |

Percent reporting relevance to decision | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | White | AA | Viet | p-value | White | AA | Viet | p-value | White | AA | Viet | p-value | |||

| Television | 88.9 | 90.5 | 25.0 | < 0.001 | *** | 82.5 | 81.0 | 15.0 | < 0.001 | *** | 36.5 | 28.6 | 5.0 | 0.025 | * |

| Radio | 49.2 | 52.4 | 0.0 | < 0.001 | *** | 39.7 | 42.9 | 0.0 | 0.002 | ** | 7.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.181 | |

| Internet | 22.2 | 23.8 | 0.0 | 0.062 | 19.0 | 23.8 | 0.0 | 0.078 | 6.3 | 23.8 | 0.0 | 0.015 | * | ||

| Newspaper | 84.1 | 71.4 | 25.0 | < 0.001 | *** | 76.2 | 57.1 | 15.0 | < 0.001 | *** | 28.6 | 4.8 | 0.0 | 0.003 | ** |

| Books | 24.4 | 38.1 | 10.0 | 0.115 | 22.2 | 38.1 | 10.0 | 0.099 | 7.9 | 23.8 | 0.0 | 0.027 | * | ||

| Pamphlets | 74.6 | 85.7 | 25.0 | < 0.001 | *** | 66.7 | 71.4 | 5.0 | < 0.001 | *** | 25.4 | 14.3 | 10.0 | 0.246 | |

| Friends/Family | 95.2 | 90.5 | 55.0 | < 0.001 | *** | 93.7 | 90.5 | 40.0 | < 0.001 | *** | 55.6 | 38.1 | 15.0 | 0.005 | ** |

| Doctors | 96.8 | 95.2 | 65.0 | < 0.001 | *** | 96.8 | 95.2 | 40.0 | < 0.001 | *** | 87.3 | 95.2 | 45.0 | < 0.001 | *** |

Key: ca info = "cancer information"; AA = "African American", Viet = "Vietnamese American";

significant (p< 0.05),

significant (p<0.01),

significant p<0.001)

Logistic regression (Table 5) failed to identify significant differences between Vietnamese and non-Vietnamese participants for overall active seeking of cancer information, nor for the use of electronic sources and print sources for any cancer SSB. However, in the case of interpersonal sources for any cancer SSB, being Vietnamese and high school-educated was an independently significant predictor for not using interpersonal sources (p=0.024; reference category=high school-educated non-Vietnamese); meanwhile, being non-high-school-educated (whether Vietnamese or not) was not associated with any significant differences from the reference category. The regression analyses were limited by the fact that there were few non-Vietnamese participants with less than high school education. Regression analyses also suggested that older age predicts increased use of electronic media, print media and interpersonal sources for cancer SSB. Female gender also appears to predict increased use of print media and interpersonal sources for cancer SSB.

Table 5.

Logistic Regression

| Outcome | Independent Variable | Odds Ratio | 95% C.I. | Adjusted p-value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Any active cancer information seeking |

Age (years) | 1.002 | (0.990, 1.014) | 0.727 | |

| Female (vs male) | 1.697 | (0.716, 4.020) | 0.230 | ||

| Unmarried (vs married) | 0.874 | (0.356, 2.148) | 0.769 | ||

| Vietnamese (vs Non-Vietnamese) |

0.408 | (0.067, 2.487) | 0.331 | ||

| Non-HS grad (vs HS grad) |

970,810,522 | (0.000, n/a) | 1.000 | ||

| Etdnic Group/Education interaction |

0.000 | (0.000, n/a) | 1.000 | ||

|

Use of electronic media for cancer SSB |

Age (years) | 1.036 | (1.015, 1.056) | 0.001 | ** |

| Female (vs male) | 3.892 | (0.714, 21.206) | 0.116 | ||

| Unmarried (vs married) | 0.933 | (0.173, 5.028) | 0.935 | ||

| Vietnamese (vs Non-Vietnamese) |

0.194 | (0.026, 1.466) | 0.112 | ||

| Non-HS grad (vs HS grad) |

67,325,226 | (0.000, n/a) | 1.000 | ||

| Etdnic Group/Education interaction |

0.000 | (0.000, n/a) | 1.000 | ||

|

Use of print media for cancer SSB |

Age (years) | 1.028 | (1.011, 1.045) | 0.001 | ** |

| Female (vs male) | 4.366 | (1.084, 17.591) | 0.038 | * | |

| Unmarried (vs married) | 1.024 | (0.248, 4.225) | 0.974 | ||

| Vietnamese (vs Non-Vietnamese) |

0.296 | (0.042, 2.069) | 0.220 | ||

| Non-HS grad (vs HS grad) |

80,889,037 | (0.000, n/a) | 1.000 | ||

| Etdnic Group/Education interaction |

0.000 | (0.000, n/a) | 1.000 | ||

|

Use of interpersonal sources for cancer SSB |

Age (years) | 1.060 | (1.024, 1.098) | 0.001 | ** |

| Female (vs male) | 25.097 | (1.734, 363.218) | 0.018 | * | |

| Unmarried (vs married) | 0.791 | (0.061, 10.185) | 0.857 | ||

| Vietnamese (vs Non-Vietnamese) |

0.041 | (0.003, 0.620) | 0.021 | * | |

| Non-HS grad (vs HS grad) |

3,476,701 | (0.000, n/a) | 1.000 | ||

| Etdnic Group/Education interaction |

0.000 | (0.000, n/a) | 1.000 |

Note: Due to differences in educational attainment between Vietnamese Americans and non-Vietnamese Americans, an interaction term was added to the model. The reference group is "non-Vietnamese Americans with High School education."

Key: SSB = "information seeking and scanning behaviors"; HS grad "high school diploma or more"; C.I. = "confidence interval";

significant at 0.05 level,

significant at 0.01 level,

significant at 0.001 level

History of mammography was reported by 98.1% of non-Vietnamese and 90% of Vietnamese participants (p=0.294). Self-reported screening was lower for prostate cancer (75% non-Vietnamese, 0% Vietnamese; p<0.001) and colon cancer (61.2% non-Vietnamese, 30.0% Vietnamese; p=0.002). Table 6 shows the percent of participants who reported screening for breast, prostate, and colon cancer, stratified by whether any SSB was reported for each cancer. A positive association was found for SSB and cancer screening. This was statistically significant for the full sample but not for the Vietnamese American sub-sample alone (but the sample was not specifically powered to assess this).

Table 6.

SSB and Self-Reported Screening Behavior

| Percent who reported screening for |

Breast Cancer | Prostate Cancer | Colon Cancer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Those with SSB, full sample | 98.4% | 68.6% | 58.8% |

| Those without SSB, full sample | 0.0% | 0.0% | 12.5% |

| p-value | 0.032 * | < 0.001 * | 0.008 * |

| Those with SSB, Vietnamese only | 100.0% | 0.0% | 38.5% |

| Those without SSB, Vietnamese only |

0.0% | 0.0% | 14.3% |

| p-value | 0.100 | 0.306 | 0.324 |

statistically significant

In order to explore the question of whether the collectivist Vietnamese culture played a role in explaining why their SSB appeared to be lower, we reviewed the portions of the Vietnamese interview transcripts pertaining to interpersonal communication. Whereas reports of active information seeking were minimal, participants spoke at length about being exposed to cancer information when it happened to emerge in casual conversations with friends and family members. If someone in a person’s social circle had cancer or had cancer screening, for example, the topic became more relevant to the respondents.

Discussion

This is the first report comparing cancer information seeking and scanning behaviors (SSB) of Vietnamese Americans to those of the larger American population. While it is important to recognize that increased SSB does not necessarily equate with increased knowledge, these results raise important questions with regard to the role of Vietnamese ethnicity and cancer SSB. Moreover, inasmuch as our data suggest that increased SSB is potentially associated with increased cancer screening, the fact that Vietnamese study participants reported lower cancer SSB could have negative downstream effects on screening behavior.

As hypothesized, Vietnamese American participants reported accessing fewer cancer information sources and lower cancer information seeking compared to White/African American participants in this sample of older adults age 50–70 years. While Vietnamese Americans did not report using interpersonal sources at higher rates than non-Vietnamese, Vietnamese participants did report using interpersonal sources more often than electronic and print sources.

Many of our findings are consistent with existing literature. In a study of online health information seeking, Lorence and colleagues (Lorence, Park, & Fox, 2006) found that more Whites (67.78%) reported health information seeking than Asian Americans (62.9%). The results also correlated with a 2003 investigation that found that non-Japanese Asians and Pacific Islanders selected physicians (54.8%) and people in general (28.6%) as among the top three most frequently accessed sources of health information (Kakai, Maskarinec, Shumay, Tatsumura, & Tasaki, 2003). These prior studies did not specify collection of data in Asian languages, therefore leaving unanswered questions about whether non-English speaking Asian Americans would report similar behaviors. Our results also showed that doctors and friends/family were considered the most relevant sources for decision making, which is in agreement with published Vietnamese American focus group data suggesting that doctors and patients are considered the most credible sources of health information (B. H. Nguyen, Vo, Doan, & McPhee, 2006); unlike our study, however, this prior work did not include comparisons between Vietnamese Americans and the general population.

In HINTS 2003, 63.7% of adults report use of Internet for health information, with highest use among those who were “Other” race (Non-White, Non-Black, Non-Hispanic; e.g., Asian) (Hesse et al., 2005). In contrast, our findings show lower health-related Internet use among Asians (Vietnamese) as compared to Whites and Blacks. In interpreting these differences, it is important to note that HINTS is a survey of adults from a broad range of ages, whereas our study focused on much older adults (age 50–70). Even more importantly, the Asians included HINTS were not entirely representative of the entire Asian American population, due to its poor representation of Asians with higher age, lower income, and lower education (G. T. Nguyen & Bellamy, 2006). Thus, our sample captured an important segment of the Asian American population that was excluded from HINTS. The HINTS data also suggested that older Americans are less likely to use the Internet as compared to younger adults, while our study showed a statistically significant increase in use of electronic media with increased age (p=0.001). However, the actual size of this effect was quite minimal (OR 1.036) and therefore may not be important from a practical standpoint.

Our results regarding the use of interpersonal sources, to the near exclusion of other sources of information, differed from a 2006 study reporting that English-proficient Asian Americans (90.6%) were more likely than Whites (78.1%) to chose printed publications as a source of cancer information (G. T. Nguyen & Bellamy, 2006). Whether our results are particular to the Vietnamese American community should be investigated further. Moreover, studies should explore whether people from more collectivist cultures might find cancer information from interpersonal sources to be more salient than do people from individualist cultures.

Comparison of seeking, depth of recall, and decision relevance for each cancer type revealed statistically significant differences for colon cancer, but not for breast or prostate cancer. This might be related to power limitations, since both male and female participants provided data regarding colon cancer, while analyses surrounding breast and prostate cancer relied on half as many participants due to the gender specific nature of these cancers. While the median number of sources used for SSB about cancer screening was significantly different between race/ethnicities for every cancer type, it was not significant for every cancer with regard to primary prevention. This could be due to low statistical power or floor effects.

This study was limited by the difference in sample selection process between Vietnamese American and the other participants. However, it was necessary to use community based organizations for recruitment due to the limited accessibility of linguistically- and culturally-isolated Vietnamese Americans. Another potential limitation is that a disparity existed between the level of educational attainment of the Vietnamese American participants as compared to African American and White participants. This educational discrepancy, however, is consistent with reports that Vietnamese Americans have the worst educational attainment of all major Asian sub-populations in the United States (US Census Bureau, 2007). We attempted to address potential effects of education through addition of an interaction term for ethnicity and education, but this was limited by the low number of non-Vietnamese participants who failed to complete high school. Consequently, the regression findings with respect to ethnicity and educational attainment should be considered purely exploratory. Future work should attempt to disentangle the potential effects of education and race/ethnicity in this regard. The question of acculturation should also be addressed, since the sample size of the present study did not allow the effects of acculturation on SSB within the Vietnamese sample. Published research has demonstrated an effect of acculturation on television use among Hispanics (Ruiz, Marks, & Richardson, 1992) and Internet use among East Asians (Ye, 2005), so it is likely that this would hold true for Vietnamese Americans. Finally, it is important to note that, given the sample size, age range (50–70 years) and limited geographical area, these findings might not be generalizable to every community, and it would be helpful to have follow-up studies in other cities (particularly those with a greater variety of Vietnamese ethnic media sources) as well as with other age groups.

The results of this study suggest that older Vietnamese Americans access cancer information at disparate rates when compared with their White and African American counterparts, across all sources (but only in bivariate analysis). Multivariate analyses are less clear-cut, and further study is warranted. If it is true that older Vietnamese Americans tend to prefer cancer information from interpersonal sources over print and electronic sources, a potentially effective strategy might be to work with community-based social networks to encourage discussions about health with reliable sources such as physicians, public health workers and peer health educators. Efforts to encourage cancer information seeking in this population might also be worthwhile, but safeguards would be needed to ensure that information seekers have appropriate health literacy to discriminate between accurate and inaccurate sources. Further research on the topic of health communication behaviors and preferences in linguistically isolated ethnic minorities is crucial in our increasingly multicultural society.

Contributor Information

Giang T. Nguyen, The Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, the Center for Public Health Initiatives, the Center of Excellence in Cancer Communication Research, and the Abramson Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA

Nicholas P. Shungu, Predoctoral Program, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA

Jeff Niederdeppe, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Health & Society Scholars Program, Department of Population Health Sciences, University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin, USA.

Frances K. Barg, The Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, and the Abramson Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA

John H. Holmes, The Center for Public Health Initiatives, the Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, and the Abramson Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA

Katrina Armstrong, The Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics and the Abramson Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

Robert C. Hornik, The Center for Public Health Initiatives and the Center of Excellence in Cancer Communication Research, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA

References

- Case DO, Andrews JE, Johnson JD, Allard SL. Avoiding versus seeking: the relationship of information seeking to avoidance, blunting, coping, dissonance, and related concepts. Journal of the Medical Library Association. 2005;93:353–362. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S-T, Chan ACM. Filial piety and psychological well-being in well older Chinese. Journals of Gerontology Series B-Psychological Sciences & Social Sciences. 2006;61(5):P262–P269. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.5.p262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtright C. Health information-seeking among Latino newcomers: an exploratory study. Information Research. 2004;10(2) paper 224 [Available at http://InformationR.net/ir/210-222/paper224.html]

- Hesse BW, Nelson DE, Kreps GL, Croyle RT, Arora NK, Rimer BK, et al. Trust and sources of health information: the impact of the Internet and its implications for health care providers: findings from the first Health Information National Trends Survey. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2005;165:2618–2624. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.22.2618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JD. Cancer-related information seeking. Cresskill, N.J: Hampton Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kakai H, Maskarinec G, Shumay DM, Tatsumura Y, Tasaki K. Ethnic differences in choices of health information by cancer patients using complementary and alternative medicine: an exploratory study with correspondence analysis. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;56:851–862. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00086-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim BSK, Li LC, Ng GF. The Asian American values scale--multidimensional: development, reliability, and validity. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2005;11:187–201. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.11.3.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorence DP, Park H, Fox S. Assessing health consumerism on the Web: a demographic profile of information-seeking behaviors. Journal of Medical Systems. 2006;30:251–258. doi: 10.1007/s10916-005-9004-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma GX, Fleisher L. Awareness of cancer information among Asian Americans. Journal of Community Health. 2003;28(2):115–130. doi: 10.1023/a:1022695313702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma GX, Shive S, Tan Y, Toubbeh J. Prevalence and predictors of tobacco use among Asian Americans in the Delaware Valley region. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:1013–1020. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.6.1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews AK, Sellergren SA, Manfredi C, Williams M. Factors influencing medical information seeking among African American cancer patients. Journal of Health Communication. 2002;7:205–219. doi: 10.1080/10810730290088094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCracken M, Olsen M, Chen MS, Jr, Jemal A, Thun M, Cokkinides V, et al. Cancer Incidence, Mortality, and Associated Risk Factors Among Asian Americans of Chinese, Filipino, Vietnamese, Korean, and Japanese Ethnicities. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2007;57:190–205. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.4.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller PJ, Wiley AR, Fung H, Liang CH. Personal storytelling as a medium of socialization in Chinese and American families. Child Development. 1997;68:557–568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngo-Metzger Q, Legedza ATR, Phillips RS. Asian Americans' Reports of Their Health Care Experiences. Results of a National Survey. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2004;19:111–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30143.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen BH, Vo PH, Doan HT, McPhee SJ. Using focus groups to develop interventions to promote colorectal cancer screening among Vietnamese Americans. Journal of Cancer Education. 2006;21:80–83. doi: 10.1207/s15430154jce2102_8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen GT, Barg FK, Armstrong K, Holmes JH, Hornik RC. Cancer and Communication in the Health Care Setting: Experiences of Older Vietnamese Immigrants, A Qualitative Study. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2008;23:45–50. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0455-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen GT, Bellamy SL. Cancer Information Seeking Preferences and Experiences: Disparities Between Asian Americans and Whites in the Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) Journal of Health Communication. 2006;11 Supp 1:173–180. doi: 10.1080/10810730600639620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederdeppe JD, Hornik RC, Kelly BJ, Frosch DL, Romantan A, Stevens RS, et al. Examining the dimensions of cancer-related information seeking and scanning behavior. Health Communication. 2007;22:153–167. doi: 10.1080/10410230701454189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves TJ, Bennett CE. We the people: Asians in the United States. Washington DC: Census Bureau; 2004. (No. Census 2000 Special Report CENSR-17) [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz MS, Marks G, Richardson JL. Language acculturation and screening practices of elderly Hispanic women. The role of exposure to health-related information from the media. Journal of Aging and Health. 1992;4:268–281. doi: 10.1177/089826439200400206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim M, Kelly B, Hornik R. Cancer information scanning and seeking behavior is associated with knowledge, lifestyle choices, and screening. Journal of Health Communication. 2006;11 Suppl 1:157–172. doi: 10.1080/10810730600637475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Census Bureau. The American Community - Asians: 2004. 2007 (No. US Census ACS-05) [Google Scholar]

- Woodall ED, Taylor VM, Yasui Y, Ngo-Metzger Q, Burke N, Thai H, et al. Sources of health information among Vietnamese American men. Journal of Immigrant & Minority Health. 2006;8:263–271. doi: 10.1007/s10903-006-9331-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye J. Acculturative stress and use of the Internet among East Asian international students in the United States. CyberPsychology & Behavior. 2005;8:154–161. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2005.8.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]