Abstract

Spectral filtering is an essential component of biophotonic methods such as fluorescence and Raman spectroscopy. Predominantly utilized in bulk microscopy, filters require efficient and selective transmission or removal of signals at one or more wavelength bands. However, towards highly sensitive and fully self-contained lab-on-chip systems, the integration of spectral filters is an essential step. In this work, a novel optofluidic solution is presented in which a liquid-core optical waveguide both transports sample analytes and acts as an efficient filter for advanced spectroscopy. To this end, the wavelength dependent nature of interference-based antiresonant reflecting optical waveguide technology is exploited. An extinction of 37 dB, a narrow rejection band of only 2.5 nm and a free spectral range of 76 nm using three specifically designed dielectric layers are demonstrated. These parameters result in an 18.4-fold increase in the signal-to-noise ratio for on-chip fluorescence detection. In addition, liquid-core waveguide filters with three operating wavelengths were designed for Forster resonance energy transfer detection and demonstrated using doubly labeled oligonucleotides. Incorporation of high-performance spectral processing illustrates the power of the optofluidic concept where fluidic channels also perform optical functions to create innovative and highly integrated lab-on-chip devices.

Introduction

Optical methods are an integral part of lab-on-chip (LOC) approaches to biomedical analysis.1 Fluorescence spectroscopy is by far the preferred method of detection due to well-developed specific labeling technology.1 However, it often relies on bulky macro-scale components for commercialized products or to achieve the ultimate detection limit of single molecule sensitivity.1,2 Optofluidic methods3 have shown promise towards self-contained LOC systems by incorporating integrated optical components (e.g. light source, optical routing and detector) with microfluidic elements.1,3 However, one key performance limiting factor that has received relatively little attention is spectral filtering.4 Essentially all biophotonic analysis methods involve at least two wavelengths (excitation and signal) that need to be separated before photodetection (especially for high sensitivity applications).4 Availability of integrated spectral filtering components with significant design flexibility would be useful for integration of ultrahigh sensitivity optical sensing methods such as single-molecule Forster resonance energy transfer (FRET) measurements,5,6 dual-color fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS)5,7 and single-molecule surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) detection.8,9 To date, optical filtering for integrated fluorescence sensors has mainly consisted of absorption and interference based approaches.4 Absorption filters can be made inexpensively, for example, by using chromophores integrated in a polymer matrix.10 However, they are restricted to specific absorbing materials (e.g. dictated by the chromophore solubility) where entirely new fabrication development may be necessary for different applications on the same device.4 In addition, the autofluorescence of the absorbing layer and polymers used has continued to be a significant performance limiting factor for low analyte concentrations.1,4,10

In contrast, the filter performance can also be tailored using wave interference from multiple dielectric layers.4,11 Interference filters are typically fully compatible with silicon microfabrication and can be made with a plethora of different materials (usually SiO2, SiN or TiO2 for visible wavelengths) that can be chosen to exhibit low autofluorescence. Despite being the leading technology for sensitive low concentration analyte detection, interference filters usually require many layers (>30), where each layer must be fabricated with tight tolerances for error (<5% thickness variations), increasing complexity and fabrication costs. Moreover, the fabrication of multiple band-pass and -stop filters for different colors on the same device would require an excessive number of layers.

In this work, a new approach to on-chip spectral filtering with interference-based liquid-core optical waveguides is introduced. Liquid-core waveguides have previously been used to guide a single spectral region (emission) to enable high-sensitivity fluorescence and Raman spectroscopy using planar integrated optics.12 The inherent spectral dependence of any interference-based waveguide is deliberately tailored to implement spectral processing at multiple wavelengths without introducing any changes in chip fabrication. The performance of these filters is characterized by: determining salient parameters, performing signal-to-noise studies for conventional fluorescence spectroscopy and demonstrating biomolecule FRET detection at low concentration. The integrated function facilitates further miniaturization and sets the stage for self-contained LOC devices with ultrahigh sensitivity.

Optofluidic platform

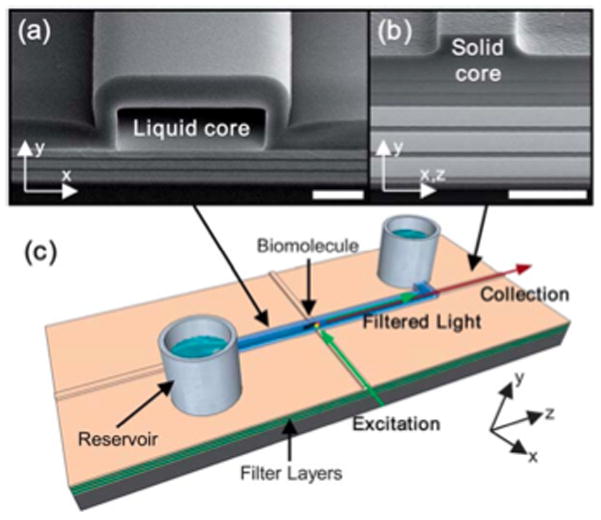

Liquid-core antiresonant reflecting optical waveguides (ARROWs)13 are a subset of optofluidic waveguides that has proven itself as an ultrasensitive LOC optical biosensor.12 Liquid-core ARROWs consist of high refractive index (n) dielectric layers (e.g. Ta2O5, n = 2.13, SiN, n = 2.05 or SiO2, n = 1.46) surrounding a hollow core (Fig. 1a) that can be filled with low index fluids (e.g. water, n = 1.33) and are made using standard Si microfabrication methods.12 The key to high sensitivity is the ability to confine light in the same fluid volume as analytes of interest. An optofluidic platform was developed to interface liquid-core ARROWs (Fig. 1a) with solid-core ARROWs (Fig. 1b) to prevent liquids from evaporating and provides a perpendicular excitation/collection geometry (Fig. 1c, colored arrows) that spatially rejects the excitation light by ~45 dB for sensitive detection applications.12 A thick top mechanical layer is grown to prevent the hollow core (Fig. 1a) from collapsing and defining the core of a rib waveguide (Fig. 1b). The liquid-core ARROW platform has already demonstrated single-fluorophore sensitivity, single liposome detection, single virus detection, chemical detection and can optically manipulate or trap particles.12–14 However, for these demonstrations, optical sensing required discrete filters. This is due to the light that is scattered at the solid to liquid-core interface (Fig. 1c, excitation), collected by the liquid-core waveguide (Fig. 1c, collection), and finally filtered before hitting the detector. Therefore, towards a self-contained LOC, an integrated on-chip filter is a necessity for high sensitivity applications. Since ARROWs are based on wave interference, the loss of a waveguide can be tailored for specific applications.12

Fig. 1.

Optofluidic ARROW platform components. (a and b) SEM images of liquid and solid-core ARROW waveguide cross-sections, respectively (scale bars are ~4 μm). (c) Schematic of an integrated optofluidic filter with perpendicular excitation/collection geometry for detecting biomolecules.

The spectral response of an ARROW is determined by choosing specific dielectric layers. If the ith layer is made with a thickness,

| (1) |

(where λD is a design wavelength, nc is the liquid-core refractive index and ni is the ith layer refractive index), with the integer MD odd, then low loss operation can be achieved. However, if MD is even, the waveguide will have high loss at λD. Therefore, an ARROW layer of thickness ti can guide light at one wavelength while being lossy at another for constant product MDλD. This can be done for not only two wavelengths, but also many design wavelengths. The vertical structure of liquid-core ARROWs (Fig. 1a, y-axis) consists of bottom low/high index (nB1/nB2) and top low/high index (nT1/nT2) layers around the liquid-core with the index profile: Si/nB1/nB2/nB1/nB2/nB1/nB2/nc/nT2/nT1/nT2/nT1/nT2/nT1/air and the thickness profile: tB1/tB2/tB1/tB2/tB1/tB2/tc/tT2/tT1/tT2/tT1/tT2/tTM where nc and tc are the core index and height, tTM is the thickness of the mechanical top layer and tBi or tTi are the bottom or top ith thickness, respectively, for the corresponding numbered low or high index. The horizontal structure (Fig. 1a, x-axis) is given by the top layer sequence surrounding the core of width, w. Traditionally, nB1 = nT1, nB2 = nT2, tB1 = tT1 and tB2 = tT2, but this is not necessary. In fact, it is sufficient for only the tB2 layer (for given nB2) to be tailored for filtering and the other layers can be independently designed (e.g. low loss operation).

FRET filter design

In order to demonstrate the flexible multiple wavelength design capabilities of ARROW technology, a FRET detection application was chosen. A FRET filter requires the excitation wavelength, λex, to be rejected in the liquid-core before reaching the detector and both the donor and acceptor wavelengths, λd and λa respectively, to be passed. This can be achieved by choosing an ARROW layer thickness such that MD = Mex is even and MD = Md or Ma is odd. By substituting the relevant variables into eqn (1) and reducing the equations, the requirement translates to satisfying the following equations simultaneously,12

| (2) |

| (3) |

This defines an M triplet (Mex, Md, and Ma) that can be found for the design wavelengths λex, λd and λa, respectively. Note that the relationship is approximate and can be optimized due to the relaxed thickness tolerances of the low loss regions.15

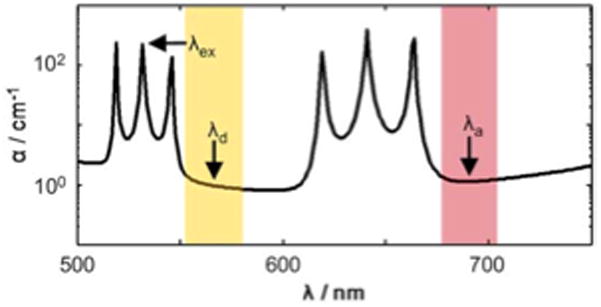

For a specific application using the common Cy3 and Cy5 FRET pair, the design wavelengths are λex = 532 nm, λd = 570 nm and λa = 690 nm. The corresponding M triplet for tB2 of (10, 9, and 7) with layers made of Ta2O5 (nB2 = 2.13) yields the thickness of tB2 = 768 nm. If a low loss design is used with layers made of SiN (nT2 = 2.05) and SiO2 (nB1 = 1.46, nT1 = 1.475) for the remaining layers, an optimized design with a thickness profile of 213/768/213/768/213/768/4000/121/369/121/369/121/1798 (units in nm) may be obtained. The hollow core dimensions w = 12 μm wide by tc = 4 μm high were chosen in order to maximize the extinction and emission wavelength transmittance. The resulting loss, α(λ), for this design, calculated by a 2 × 2 matrix formalism,11 yields the desired high α(λex), low α(λd) and low α(λa) (Fig. 2). Compared to standard discrete interference optical filters used for FRET detection (Fig. 2, shaded bands), the transmission passbands are much broader with a free spectral range (FSR) of 73 nm and thus can collect more emission light. Due to the design freedoms, the FSR can be made wider or more narrow if desired. The narrow stopband at λex is more selective than discrete passband filters and could be useful for applications with small Stokes or anti-Stokes shifts, thereby expanding the range of usable fluorescent dyes or use for Raman scattering. The other noncritical layers can be made with a much wider thickness tolerance (<20%) and index tolerance with little effect on the filter function.

Fig. 2.

Integrated optofluidic filter design calculated by loss spectral dependence. The excitation wavelength, λex, and the Cy3 and Cy5 FRET pair design emission wavelengths, λd, λa, respectively, are depicted. The light and dark bands show the typical passbands for a standard discrete FRET filter set.

Filter fabrication

The optofluidic filter design above was constructed with two types of available deposition methods. The bottom layers were deposited at the design parameters (within <6% thickness deviations and an index tolerance of ±0.005) with an inexpensive sputtering method. The top wide tolerance layers (<20%) are deposited by plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition over a patterned sacrificial core (SU-8 10, Microchem) to ensure multilayer conformality and the structural integrity of the hollow core. The solid-core ARROWs (Fig. 1b) were formed in the thick top SiO2 (900 nm ridge depth) by contact photolithography (Karl Suss America) and an inductively coupled plasma reactive-ion etch (RIE) step (Trion Tech.). The sacrificial core was exposed by another RIE step (Anelva Corp.) and then the wafer was placed in an optimized fast-etch piranha bath (H2SO4 : H2O2, 1 : 1) to remove the SU-8 and form the hollow core.16 SEMs of the waveguide cross-sections are shown in Fig. 1a and b where the thicker Ta2O5 filter layers appear bright white. The chips were cleaved to a desired size (~1 × 1 cm2) and metal tubes (3 mm diameters by 3 mm high) were glued using epoxy resin around the hollow core inlets defining reservoirs used to introduce fluids and analytes (Fig. 1c). The waveguides were then filled and the spectral response was investigated.

Results and discussion

Filter spectral response

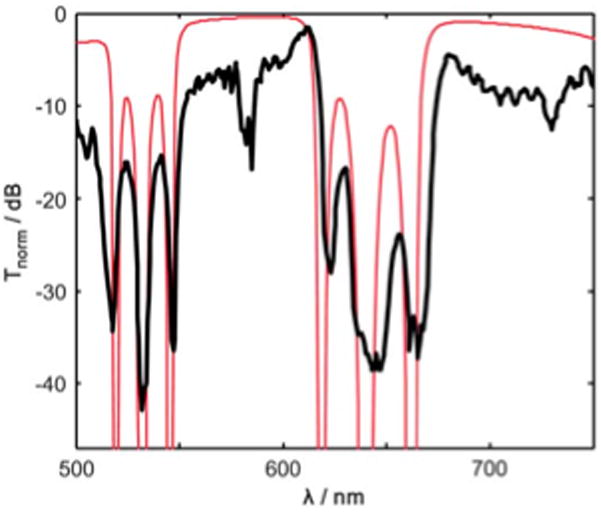

Spectral characterization was done using a previously described setup.17 A high intensity white light (~475 to 950 nm) is generated by coupling pulsed light (120 fs temporal width, 75 MHz repetition rate) at 850 nm (Ti:Sapphire, MIRA, Coherent) into a highly nonlinear photonic crystal fiber (790 nm zero dispersion, 1 m long, Thorlabs). The white light is then coupled through a water-filled optofluidic filter via the collection solid-core ARROW and collected by an optical spectrum analyzer at the opposite end. The response is later normalized by the input light. The calculated transmission spectrum corresponding to Fig. 2 (Fig. 3, thin line) shows excellent agreement with the experimental background normalized transmittance, Tnorm (Fig. 3, thick line), for the 4 mm long liquid-core waveguide. The fact that all the high loss dips match in number, spectral position and width validates the design and calculation methods used. Fig. 3 also shows the very high donor channel extinction defined as ΔTd = Tnorm (570 nm) − Tnorm (532 nm) = 36 dB and an acceptor channel extinction of ΔTa = Tnorm (690 nm) − Tnorm (532 nm) = 37 dB for only 4 mm long samples. The FSR of 76 nm is very close to the expected 73 nm and still allows for more collected light than a discrete passband filter. The average 3 dB bandwidth of the three rejection dips in the 500 to 550 nm range was 2.5 nm and 5.8 nm in the 600 to 670 nm range. The average rejection transition edge widths were very steep at ~1 nm. The limited extinction is attributed to the roughness of the bottom layers.

Fig. 3.

Optofluidic filter experimental (thick line) and calculated design (thin line) spectral response for a 4 mm long liquid-core ARROW waveguide.

The uniformity of the filter response across an entire 4 inch Si wafer with 32 devices was excellent with average extinctions of ΔTd = 27.5 ± 5.0 dB and ΔTa = 26.8 ± 6.0 dB for the 4 mm long liquid-core ARROWs. This verifies that all intact devices were functioning as multi-wavelength optofluidic FRET filters and demonstrates that the extinction for multiple design wavelengths can be achieved using only three strict tolerance layers. The signal-to-noise ratio improvement due to the achieved extinction is investigated in the next section.

Nanoparticle sensing

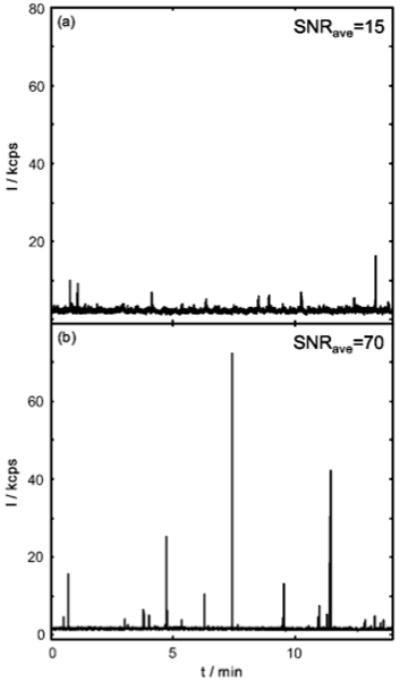

In order to determine the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) improvement using the optofluidic filters, fluorescent nanoparticles (100 nm diameter, Tetraspeck, Invitrogen) were introduced into the liquid-core via the reservoir. The nanoparticles were diluted by ultra-pure water (18 MΩ cm) with bovine serum albumin (BSA, 1.4 μg mL−1 final concentration) to a final concentration of 2.6 × 1010 particles per mL corresponding to an average of 0.3 particles in the excitation volume of 11.4 fL (using e−2 radii). To decrease the probability for particle coagulation, the solution of particles was ultrasonicated. The BSA was added to prevent the nanoparticles from sticking to the microfluidic channel walls. Laser light (633 nm, HeNe, 12 mW, Melles Griot) was coupled into the excitation solid-core ARROW (Fig. 1c) via a single-mode fiber (~2 mW) and, when the single nanoparticles flowed past the excitation region, the particle was excited. The particle fluorescence was then collected by the liquid-core ARROW, propagated through the collection solid-core ARROW and directed to a single photon avalanche photodiode (AQR-14, Perkin Elmer). Due to the sensitivity of the detection setup, an additional optical filter (640 nm longpass filter, Semrock) was necessary to compare standard ARROWs (broadband transmission from ~500 to 900 nm without filter function) and filter ARROW chips.

Measurements were performed on standard ARROWs14 (Fig. 4a) and the optofluidic filters (Fig. 4b). As can be seen, the detected particle SNR (baseline subtracted signal divided by the standard deviation of the noise) greatly improves. The noise standard deviation was 0.4 kcps for standard ARROWs and 0.11 kcps for filter ARROWs. The average SNR increases from SNRave = 15 using a standard ARROW to SNRave = 70 with a filter ARROW (or a 4.7 fold improvement). The maximum SNR achieved was 35 for standard ARROWs and 645 for a filter ARROW (or an 18.4 fold increase). The signal amplitude deviation is attributed to the particles travelling through the excitation volume away from the optimal coupling efficiency region (near the center of the liquid-core waveguide). This could be improved by focusing the particles in the center of the waveguide, for example, by optical manipulation means.14 Moreover, since the excitation solid-core waveguide is located in the center of the device, filtering is achieved only by a 2 mm long region (half of the device) where the SNR improvement is less than it would be if the full extinction was applied. Therefore, further improvement can be made by making the applied filter length longer to achieve the desired SNR for an application (e.g. 8 mm long to achieve ~55 dB extinction).

Fig. 4.

Fluorescent nanoparticle sensing using the (a) standard ARROW or (b) filter ARROW.

FRET sensing

To apply the filter towards FRET measurements, oligonucleotides with end-labeled FRET Cy3 and Cy5 pairs were introduced into the waveguide. The oligonucleotides (HPLC purified, IDT) were designed to avoid hairpin formation using the following sequences: 5′-TGC AGC GAG TTC AGC/Cy3-3′ (15 bases, donor) and 3′-ACG TCG CTC AAG TCG TA/Cy5-5′ (17 bases, acceptor). The two extra bases at the Cy5 5′ end were added to optimize FRET efficiency by avoiding steric clashing. Oligonucleotides (20 μM) were hybridized in TE buffer with salt (pH 8.0, with final concentrations of 2.5 mM Tris–HCl, 150 μM EDTA and 12.5 mM NaCl) at 53 °C for 2 min and then cooled to room temperature over one hour. Single stranded (donor only) and double stranded (hybridized FRET pair) oligonucleotides were diluted to a final concentration of 600 nM in TE buffer. To avoid significant sticking to the channel walls, the optofluidic filter was filled with BSA (10 μg mL−1) and flushed with TE buffer several times before introducing the analyte. Once the optofluidic filter was filled with the analyte solution, a laser (532 nm, Verdi V10, Coherent) was used to excite the donor dye, Cy3, by coupling light into the excitation solid-core waveguide (Fig. 1c) via a single-mode fiber with an output of ~2 mW. Since the optical extinction for the device is only ~14 dB (with a 2 mm long collection path), the signal was split into two channels using a dichroic filter (640 long-pass, Omega) and went through single bandpass emission filters used for the donor channel (585 ± 17 nm, Omega, Fig. 2, light band) and acceptor channel (670 ± 17 nm, Omega, Fig. 2, dark band) before being coupled to separate APDs (Perkin Elmer).

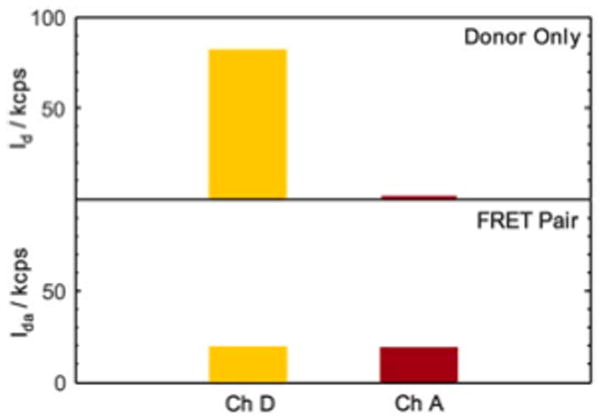

When oligonucleotides with only donor dyes attached were present, the background subtracted signal from the donor channel (Ch D) was high (81.2 ± 0.5 kcps) and the acceptor channel (Ch A) had no signal above the background (Fig. 5, top). When oligonucleotides with both donor and acceptor dyes were hybridized and introduced, Ch D showed a marked signal decrease (17.8 ± 0.2 kcps) and Ch A had a signal increase (17.3 ± 0.4 kcps) indicative of resonant energy transfer. The standard measure of FRET efficiency is,5

Fig. 5.

FRET signal in the donor (Ch D) and acceptor (Ch A) channel with (top) donor only and (bottom) hybridized FRET pair oligonucleotides present.

| (4) |

where Id is the intensity of the donor signal in the presence of the donor only and Ida is the intensity of the donor signal in the presence of the donor and acceptor pairs. Using eqn (4), the efficiency is E = 78%, which is slightly less than expected from the designed sequence structure. This discrepancy is attributed to the uncertainty in orientation of the dye and the influence of residual single stranded donor oligonucleotides (verified by agarose sol–gel electrophoresis). In Fig. 5, channels D and A showed a SNR of 80 and 10, respectively, which was consistent with the integrated filter rejection characteristics shown in Fig. 3 and the SNR level of the nanoparticle demonstration in Fig. 4. Therefore, FRET between Cy3 and Cy5 was detected in the nanomolar range using this specifically designed integrated optofluidic filter.

Conclusions

On-chip optofluidic filters with multiple high and low loss regions were designed by tailoring three bottom layers of a liquid-core ARROW. Compared to previous ARROW versions with a single low-loss visible wavelength region, a complex frequency response was implemented without complicating the fabrication process. The reduction of the number of strict tolerance layers (3) compared to other interference-based filter designs (>30) is an order of magnitude or more with similar or superior performance.4 High extinction (37 dB) using 4 mm long optofluidic filters was shown. Nanoparticle sensing measurements more than quadrupled the average signal-to-noise ratio by using filter ARROWs instead of standard ARROWs. FRET was detected with a specific optofluidic filter design at a concentration of 600 nM. When a 2 : 1 minimum SNR is assigned, the estimated LOD is 15 nM (or 103 dyes within the 11.4 fL excitation volume), which rivals other integrated LOC approaches (LOD ranging from 10 nM to 10 μM).1,4 Compared with previous FRET experiments using microscopes in combination with microfluidic channels,4,18 this demonstration of fully planar detection represents a significant step towards point-of-care applications. While the present experiments were carried out using purified nucleic acids, more complex clinical samples can be investigated using appropriate upstream microfluidic filtration and purification to avoid clogging or nonspecific binding.19

There are several ways to take advantage of the ARROW filter technology presented in this work. These include the design of filters for Raman scattering, combination with selectively patterned solid-core waveguide filters, tunable filter sections using different core fluids, or downstream integration of on-chip photodetectors.9,12,17,20 As the optical properties of ARROW-based devices continue to improve, integrated spectral filtering will become an essential component for chip-based optical analysis on the single particle level.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank R. Hoelle for SEM imaging, D. Ermolenko for oligonucleotide sequence design, M. Eberle for sol–gel electrophoresis measurements, M. Rudenko for software support and gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the NIH through grants R01EB006097 and R21EB008802 and the W. M. Keck Center for Nanoscale Optofluidics at the University of California Santa Cruz.

References

- 1.Myers FB, Lee LP. Lab Chip. 2008;8:2015. doi: 10.1039/b812343h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weiss S. Science. 1999;283:1676. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5408.1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Craighead H. Nature. 2006;442:387. doi: 10.1038/nature05061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Psaltis D, Quake SR, Yang C. Nature. 2006;442:381. doi: 10.1038/nature05060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Monat C, Domachuk P, Eggleton B. Nat Photonics. 2007;1:106. [Google Scholar]; Hawkins AR, Schmidt H. Handbook of Optofluidics. CRC Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dandin M, Abshire P, Smela E. Lab Chip. 2007;7:955. doi: 10.1039/b704008c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lakowicz JR. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. 3. Springer; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roy R, Hohng S, Ha T. Nat Methods. 2008;5:507. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Varghese SS, Zhu Y, Davis TJ, Trowell SC. Lab Chip. 2010;10:1355. doi: 10.1039/b924271f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Magde D, Elson E, Webb WW. Phys Rev Lett. 1972;29:705. [Google Scholar]; Schwille P, Meyer-Almes FJ, Rigler R. Biophys J. 1997;72:1878. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78833-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jeanmaire DL, Van Duyne RP. J Electroanal Chem Interfacial Electrochem. 1977;84:1. doi: 10.1016/0302-4598(87)85005-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moskovits M. Rev Mod Phys. 1985;57:783. [Google Scholar]; Nie S, Emory SR. Science. 1997;275:1102. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5303.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Kneipp K, Wang Y, Kneipp H, Perelman LT, Itzkan I, Dasari RR, Feld MS. Phys Rev Lett. 1997;78:1667. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.76.2444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bliss CL, McMullin JN, Blackhouse CJ. Lab Chip. 2007;7:1280. doi: 10.1039/b708485d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Hofmann O, Wang XH, Cornwell A, Beecher S, Raja A, Bradley DDC, deMello AJ, deMello JC. Lab Chip. 2008;5:507. doi: 10.1039/b603678c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Bliss CL, McMullin JN, Blackhouse CJ. Lab Chip. 2008;8:143. doi: 10.1039/b711601b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yeh P. Optical Waves in Layered Media. 2. Wiley; New Jersey: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmidt H, Hawkins AR. Microfluid Nanofluid. 2008;4:3. doi: 10.1007/s10404-007-0199-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Hawkins AR, Schmidt H. Microfluid Nanofluid. 2008;4:17. doi: 10.1007/s10404-007-0194-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yin D, Barber JP, Hawkins AR, Deamer DW, Schmidt H. Appl Phys Lett. 2004;85:3477. [Google Scholar]; Bernini R, Campopiano S, Zeni L. IEEE J Sel Top Quantum Electron. 2002;8:106. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yin D, Lunt EJ, Rudenko MI, Deamer DW, Hawkins AR, Schmidt H. Lab Chip. 2007;7:1171. doi: 10.1039/b708861b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Rudenko MI, Kuhn S, Lunt EJ, Deamer DW, Hawkins AR, Schmidt H. Biosens Bioelectron. 2009;24:3258. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Kuhn S, Measor P, Lunt EJ, Phillips BS, Deamer DW, Hawkins AR, Schmidt H. Lab Chip. 2009;9:2212. doi: 10.1039/b900555b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Kuhn S, Lunt EJ, Philips BS, Hawkins AR, Schmidt H. Lab Chip. 2010;10:189. doi: 10.1039/b915750f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Measor P, Kuhn S, Lunt EJ, Philips BS, Hawkins AR, Schmidt H. Opt Express. 2009;17:24342. doi: 10.1364/OE.17.024342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Archambault JL, Black RJ, Lacroix S, Bures J. J Lightwave Technol. 1993;11:416. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holmes M, Keeley J, Hurd K, Schmidt H, Hawkins AR. J Micromech Microeng. 2010;20:115008. doi: 10.1088/0960-1317/20/11/115008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phillips BS, Measor P, Zhao Y, Schmidt H, Hawkins AR. Opt Express. 2010;18:4790. doi: 10.1364/OE.18.004790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yea K-h, Lee S, Choo J, Oh C-H, Lee S. Chem Commun. 2006;14:1509. doi: 10.1039/b516253j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Jung J, Chen L, Lee S, Kim S, Seong GH, Choo J, Lee EK, Oh CH, Lee S. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2007;387:2609. doi: 10.1007/s00216-007-1158-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Hsieh ATH, Pan PJH, Lee AP. Microfluid Nanofluid. 2009;6:391. [Google Scholar]; Varghese SS, Zhu Y, Davis TJ, Trowell SC. Lab Chip. 2010;10:1355. doi: 10.1039/b924271f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim J, Johnson M, Hill P, Gale BK. Integr Biol. 2009;1:574. doi: 10.1039/b905844c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Erickson D, Rockwood T, Emery T, Scherer A, Psaltis D. Opt Lett. 2006;31:59. doi: 10.1364/ol.31.000059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]