Abstract

Nulliparous female mice that have not experienced mating, pregnancy, or parturition show near immediate spontaneous maternal behaviour when presented with foster pups. The fact that virgin mice display spontaneous maternal behaviour indicates that the hormonal events of pregnancy and parturition are not necessary to produce a rapid onset of maternal behaviour in mice. However, it is not known how similar maternal behaviour is between virgin and lactating mice. Here we show that naturally postpartum females are faster to retrieve pups and spend more time crouching over pups than spontaneously maternal virgin females, but these differences diminish with increased maternal experience. Moreover, 4 days of experience with pups induced pup retrieval on a novel T-maze. Further, the effects of experience on subsequent maternal responsiveness are not dependent on gonadal hormones as ovariectomised females with 4 days of pup experience show similar pup retrieval on a novel T-maze as postpartum mice. Four days of maternal experience also induced T-maze pup retrieval in ovariectomised aromatase knockout female mice that was not significantly different from the maternal responsiveness of ovariectomised wildtype littermates. These data suggest that maternal experience can induce maternal behaviour in females that have never been exposed to oestradiol at any time in development or adulthood. Finally, ovariectomised pup-experienced females continue to retrieve pups on a novel T-maze one month after the initial experience, suggesting that, even in the absence of oestradiol, maternal experience produces long-lasting modifications in maternal responsiveness.

Keywords: maternal behaviour, aromatase, social behaviour, oestrogens, epigenetic

Introduction

At the time of birth, female rodents ensure the survival of their altricial young with the display of maternal behaviours (retrieval, licking, nursing) (1). Nulliparous rats and mice will also show maternal behaviour when presented with foster pups (1, 2). In the absence of hormone stimulation, continual exposure to pups initiates maternal responsiveness. Virgin female rats require 6–8 days of pup exposure in order to show maternal behaviour (3). In contrast, mice of many strains show “spontaneous” maternal responses to pups within the first 15 or 30 minutes of pup presentation (2, 4–12), suggesting that the onset of maternal behaviour in mice is independent from hormonal mediation (8, 9, 11, 13, 14). Whereas some reports note that postpartum and virgin mice spend similar amounts of time with pups (14–16), detailed comparisons between postpartum and virgin females have not been reported. Here we examined spontaneous maternal behaviour in the inbred C57BL/6J (B6) strain of mice. We report that naturally postpartum females and spontaneously maternal females respond differently toward pups, and that differences diminish as virgin female mice gain experience with pups.

During the postpartum period, mother-pup interaction induces maternal motivation, or an increase in approach behaviours that help the female gain access to offspring (1, 17, 18). For example, postpartum rats and mice will traverse a novel environment containing pups and retrieve them back to their nest (19–21) or press a lever to obtain pups (22, 23). Whereas initial reports indicated that, when tested under these demanding conditions, virgin rats and mice were not responsive to pups (19, 20, 23–25), some recent evidence suggests that maternal motivation can be induced in virgin rats, but only after long periods of pup exposure (26–28).

In the present study, given that the maternal responsiveness of virgin females increased across test day, we asked whether maternal experience would affect subsequent maternal motivation in B6 mice (29, 30). To directly assess whether maternal experience effects on maternal motivation were dependent upon circulating hormones, we examined whether ovariectomised, pup-experienced female mice, like postpartum mice, were willing to traverse a novel T-maze in order to retrieve pups. In addition, we determined that the effects of pup experience on maternal motivation persist in the complete absence of oestradiol. Finally, in rats, experience with pups has been found to produce long-lasting modifications in subsequent maternal care and maternal motivation (26–28, 31–33). Thus, we examined whether experience with pups produced long-lasting effects on maternal care and motivation in B6 mice.

Materials and Methods

Subjects and housing

The background strain of all mice used for these studies was C57BL/6J. All mice were originally of Jackson Lab origin and were bred and maintained in the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Animal Facility. ArKO mice and WT littermates were produced using heterozygous breeding pairs and were genotyped for disrupted or WT Cyp19 gene as previously described (34). ArKO mice were backcrossed more than 10 times into C57BL/6J. Female mice were nulliparous females, naive to pups (except for their own littermates), weaned at 21 days of age, single-sex group-housed until the beginning of each experiment (60–100 days of age), and individually housed thereafter. Mice were maintained on a 12:12 light/dark cycle (lights off at 1200 EDT) and received food (#7912; Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI) and water ad libitum. Ovariectomies were conducted under isoflourane anaesthesia. After gonads were removed mice were given an s.c. Injection of 0.9% sodium chloride (for rehydration), a topical analgesic (0.25% Bupivacaine) and kept warm until they awakened. All females recovered from surgery for at least one week. A separate group of mice served as foster dams that provided stimulus pups. These females were paired with a male and allowed to give birth naturally. All procedures were in compliance with the University of Virginia Animal Care and Use Committee.

Experiment 1

Mice were randomly assigned to either the postpartum (n= 9) or the virgin (n= 10) group. Postpartum females were housed with a male of the same strain until 24–48 hours prior to parturition. On the day of birth (postpartum day 0 = PP0), litters were culled to 4 pups, and maternal behaviour testing began PP1. On each test day, prior to the start of testing, pups were briefly removed and scattered. In order to compare the spontaneous maternal responsiveness of virgin female mice with the natural onset of maternal behaviour in postpartum females, postpartum females remained with their pups at the end of the 2-hour maternal behaviour test. Virgin female mice were presented with 4 stimulus pups at the start of maternal behaviour testing, and these pups were removed at the end of the 2-hour test period and returned to a lactating dam.

Experiment 2

In Experiment 1, four days of pup exposure (2h/day) facilitated retrieval behaviour in virgin mice. Therefore, we tested the hypothesis that 4 days of experience (2h/day) would also induce retrieval behaviour on a novel T-maze, and that the effect of maternal experience on subsequent maternal behaviour was not dependent on ovarian hormones. Female mice were randomly assigned to the postpartum group (n= 9), the pup-experienced group (n= 10), or the naive group (n= 11). The pup-experienced and pup-naive groups were comprised of nulliparous ovariectomised virgin females. Pregnant mice were monitored for parturition and newborn pups were removed within 2–8 hours of birth. Pup-experienced and postpartum females received 4 consecutive days of pup exposure (2h/day), while pup-naive females were not exposed to pups. Pup exposure for postpartum females began the day they gave birth. Dams were exposed to their biological pups for 2–8 hours on PP0 and for the next three days they received stimulus pups (obtained from a donor female) for 2 hours each day. At the start of each 2-hour pup exposure, 4 pups were scattered in the cage. At the end of the 2-hour period, upon removal of the pups, all females had retrieved the 4 pups to the nest location. During the exposure phase, pup-naive females were not exposed to pups, rather their cage tops were opened and their bedding was disturbed at the beginning and end of the 2-hour period. On the 5th day, 24 hours after the last pup exposure, all females were tested for pup retrieval on a novel T-maze. In order to examine whether retrieval behaviour on the T-maze was related to general differences in anxiety between the groups, all females were tested on the elevated plus maze (EPM) on the day after the T-maze retrieval test.

Experiment 3

The results of Experiment 2 suggest that circulating oestradiol is not required for experience-effects on motivation, however we can’t rule out the possibility that synthesis of oestradiol in the brain produced effects on maternal behaviour (35, 36). To investigate whether the effects of maternal experience on maternal motivation would persist in the complete absence of oestradiol, we used female mice with a targeted mutation in the Cyp19 gene (aromatase knockout mice; (36). Aromatase knockout (ArKO) mice are deficient in aromatase, the enzyme that is necessary for oestradiol biosynthesis. ArKO mice (n= 6) and their wildtype (WT; n= 8) littermates were ovariectomised. All females were tested for maternal behaviour in the home-cage for two hours/day on test days 1–4 (as described above). On test day 5, all females were tested for retrieval behaviour on the T-maze. Note that ArKO mice do not differ from WT mice on measures of anxiety (37), therefore we did not examine whether T-maze retrieval behaviour was related to general differences in anxiety between these two groups.

Experiment 4

Ovariectomised nulliparous mice were randomly assigned to the pup-experienced group (n= 11) or the naive group (n= 11) for the exposure phase (Figure 1). One week following the exposure phase, mice were tested for maternal behaviour in the home cage on two consecutive test days. The results of Experiment 1 indicated that by the third day of maternal behaviour testing, differences in pup retrieval between postpartum and virgin females had diminished. Thus, we asked whether, by test day 3, retrieval behaviour would also be facilitated in the T-maze. To determine if maternal experience had a lasting effect on maternal motivation we examined pup-retrieval on the T-maze one month after the first experience with pups (trial 2). All females remained individually housed, and were not exposed to pups in the one-month interim between trials 1 and 2. Prior to the start of the T-maze test all females were briefly exposed to pups (one hour of pup stimulation followed by one hour of pup deprivation) (28).

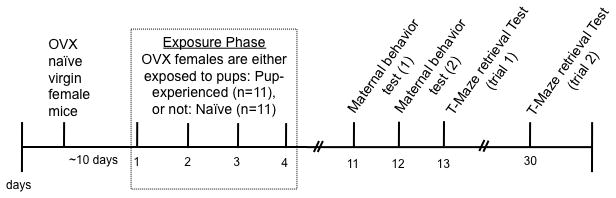

Figure 1.

Methods for Experiment 4. Timeline of pup exposure and test schedule.

Maternal behaviour testing

Tests were conducted in the dark phase of the light/dark cycle under dim red light. Animals were habituated to the test room for at least 24 hours prior to testing. Tests began with the placement of 4 stimulus pups (all the same age between 2-7 days old) in the areas of the cage farthest from the female’s nest. A 15-minute retrieval test was conducted during which the following behaviours were scored: latencies to retrieve each pup to the nest, sniff/lick all pups in the nest, and crouch over all pups in the nest. Forty-five minutes after the presentation of pups, each female was observed continuously for 15 minutes. Behaviour was scored once every 15 seconds for a total of 60 observations, during this time hovering, sniffing and licking, or crouching over the pups were recorded. Hovering was defined as an upright posture over pups (so that pups had access to the female’s ventral surface), including actively sniffing/licking the pups or engaging in self-grooming. In contrast, crouching was recorded when females were in a quiescent, immobile posture, with all four limbs supporting a slightly arched or highly arched posture over the pups (38). This detailed 15-minute observation was followed by an additional 1-hour observation during which behaviour was scored once every 3 minutes for a total of 20 observations.

T-Maze retrieval test

The walls and floors of the T-maze apparatus (67.3 X 11.4 X 8.3 cm) were clear Plexiglas upon which a removable wire mesh top was fitted. The vertical runway measured 48.3 cm in length and opened into a horizontal runway that measured 67.3 cm in length. An 11.4 cm X 12.7 cm goal box was attached to the end of the vertical runway which could be closed off from the rest of the T-maze by a clear Plexiglas guillotine door. Three stimulus pups were scattered in the horizontal arm of the T-maze: one pup was placed in the middle of the horizontal arm and one pup was placed at each end of the horizontal arm. At the start of the retrieval test, each female was placed into the goal box of the T-maze with her nest material. After a10-minute habituation period, the Plexiglas door was removed and the 15-minute retrieval test began. The following behaviours were scored: latency to emerge (all four paws) from the goal box, latency to sniff the first pup, and latency to retrieve each pup to the goal box. The test ended after 15 minutes, or when the female had retrieved all three pups to the goal box. The maze was thoroughly cleaned with 95% alcohol between each test.

Elevated Plus Maze (EPM)

The floors and walls of the elevated plus maze (ENV-560A; Med Associates, Inc., St. Albans, VT) were black polypropylene. Each runway measured 6.1 cm wide and 34.9 cm long and was raised 71.25 cm from the floor. The walls on the closed arms were 20.3 cm high. The outer arms were marked with a piece of white tape that indicated “outer” open arms (39). At the start of the test, each mouse (pup-experienced, n = 10; naive, n = 11; intact postpartum, n = 9) was placed in the centre of the EPM, facing an open arm, and allowed to explore the maze for 10 minutes. A video camera mounted above the EPM recorded all test sessions, and all sessions were subsequently scored for the following behaviours: time spent in the open arms (s), time spent in the outer open arms (s), time spent in the closed arms (s), and number of times the mouse crossed from one arm to the other. An animal was considered in an arm if all four paws were inside the arm.

Statistical analysis

Data from Experiments 1 and 3 were analyzed using a 2X4 ANOVA, with reproductive status as the between factor and test day as the repeated factor, followed by trend analysis across test day. Data from Experiment 4 were also analyzed this way, except that a 2X2 ANOVA was used. Data from Experiment 2 were analysed using a one-way ANOVA. To examine differences between groups on a given test day, a post hoc Tukey-Kramer test was conducted. For the number of pups retrieved nonparametric statistics were used.

Results

Experiment 1: Differences in the quality of maternal behaviour between postpartum and virgin female mice diminish as a result of maternal experience

All female mice retrieved pups to the nest and crouched over pups during the first 15-minute test on each test day. Postpartum females were faster to retrieve [first pup (F (1,51)= 64.3, p< 0.01), Figure 2a; all pups (F(1,51)= 26.67, p< 0.01), Figure 2b] when compared with virgin females. There was a main effect of test day on latency to retrieve [first pup (F(3,51)=12.52, p< 0.01); all pups (F(3,51)=8.24, p< .01)], as well as a significant interaction between test day and reproductive status on latency to retrieve [first pup (F(3,51) =11.14, p< 0.01); all pups (F(3,51) =4.01, p< 0.02)]. Post hoc analyses revealed a significant trend for all females to retrieve pups faster across test day (p< 0.05). Postpartum females retrieved the first pup faster than virgin females on test day 1, and all pups faster than virgins on test days 1–2 (p< 0.05)

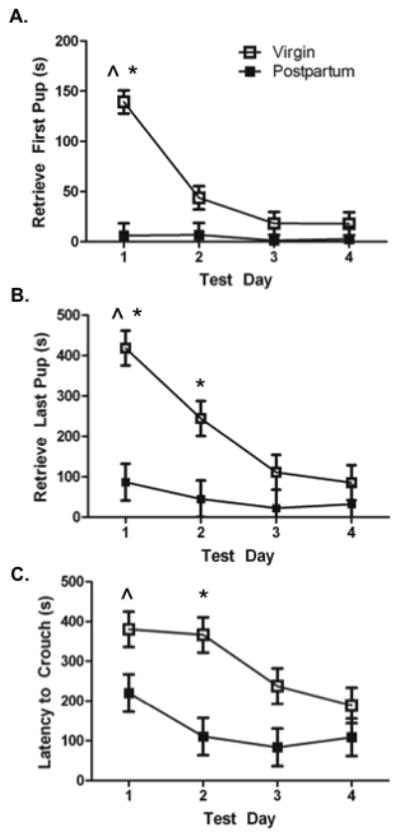

Figure 2.

Latency (s) to the onset of maternal behaviour on test days 1–4. Differences between virgin (n= 10) and postpartum (n=9) females fade over test day as virgins respond more quickly to pups. A) Latency (s) to retrieve the first pup on test days 1–4. B) Latency (s) to retrieve all pups on test days 1–4. C) Latency to crouch over all four pups in the nest. * Significantly different from postpartum group ^ Significant trend across test days

There was a significant main effect of reproductive status (F(1,51)= 15.78, p< 0.01; Figure 2c), and test day (F(3,51)= 4.78, p< 0.01) on latency to crouch over all pups in the nest. There was a trend for all females to crouch over pups more quickly as test day advanced (p< 0.05). Postpartum females were faster to crouch over pups on test day 2 (p< 0.05).

The total time spent with pups differed across test day (F(3,51) = 3.64, p< 0.02; see Table 1). There was a significant trend toward more time with pups across test day (p< 0.05). Compared to postpartum females, virgin females spent significantly more time licking pups (F(1,51) = 16.57, p< 0.01), on days 2 and 4 of testing (p< 0.05). An inverse relationship between virgins and postpartum females was seen for crouching behaviour. There were significant main effects of reproductive status (F(1,51) = 15.19, p< 0.01) and test day (F(3,51) = 6.90, p< 0.01). There was a trend toward more crouching behaviour as test day advanced. This pattern of maternal responding continued in the second hour of observation (data not shown).

Table 1.

| Group | Test Day | Frequency pup contact ± SE | Frequency Licking ± SE | Frequency Crouching ± SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Postpartum n= 9 | 1 | 45.1± 3.3 | 12.6 ± 3.8 | 28 ± 5.5 |

| 2 | 58.9 ± 3.3 | 7.8 ± 3.8* | 50.8 ± 5.5 | |

| 3 | 56.8 ± 3.3 | 17.4 ± 3.8 | 36.4 ± 5.5 | |

| 4 | 59.2 ± 3.3 | 3.1 ± 3.8* | 56 ± 5.5 | |

| Virgin n= 10 | 1 | 55.6 ± 3.1 | 25.3 ± 3.6 | 19.2 ± 5.3 |

| 2 | 59.5 ± 3.1 | 29.5 ± 3.6 | 27.1 ± 5.3 | |

| 3 | 58.7 ± 3.1 | 27.3 ± 3.6 | 27.4 ± 5.3 | |

| 4 | 59.9 ± 3.1 | 19.8 ± 3.6 | 38.3 ± 5.3 | |

Number of observations (out of 60 total) in contact with pups, licking, or crouching during the 15 min observation. There was a statistically significant trend across test days to spend more time with pups, less time licking, and more time crouching.

Significantly different from virgin group on the same test day

Experiment 2: Maternal motivation is dependent upon experience with pups rather than ovarian hormones

A significant main effect of pup experience on latency to retrieve each of the three pups (F(2,27) = 9.57, 6.81, 5.81, p< 0.01, respectively), from the ends of a novel T-maze was detected (Figure 3a). Pup-naive females were significantly slower to retrieve pups when compared with postpartum and pup-experienced females. There were no significant differences in retrieval latencies between postpartum and pup-experienced females. Pup-naive females also retrieved significantly fewer pups than postpartum and pup-experienced females (H = 11.6236, 2 d.f., p< 0.01; see Figure 3b).

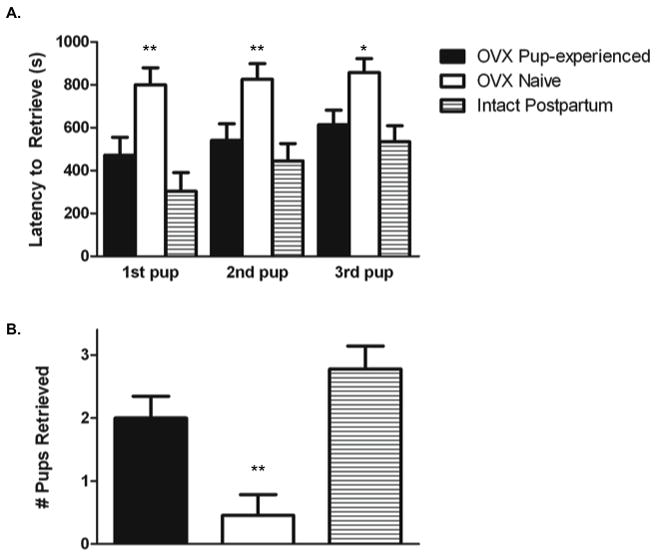

Figure 3.

Retrieval responses on the T-maze after 4 days of pup exposure (pup-experienced, n= 10; intact postpartum, n= 9) or no pup exposure (naive, n= 11). Pup-experienced and pup naive females were ovariectomised. A) Latency in seconds to retrieve each pup from the far ends of the T-maze. B) Number of pups retrieved from the far ends of the T-maze. **Significantly different from postpartum and pup-experienced groups. *Significantly different from the postpartum group

Because differences in pup retrieval on the T-maze might be associated with differences in anxiety behaviour between females, we examined the behaviour of these subjects on the elevated plus maze (EPM). There were no significant differences in the amount of time spent in the open (F(2,27)=. 47, p= 0.62), the closed (F(2,27)=2.05, p= 0.14) or the outer open arms (F(2,27)=1.19, p= 0.31; Table 2). Additionally, there were no significant differences in crosses between groups (F(2,27)=1.80, p= 0.185).

Table 2.

| Group | N | Time in Open Arms (s) (Mean ± SEM) | Time in Outer Open Arms (s) (Mean ± SEM) | Time in Closed Arms (s) (Mean ± SEM) | Arm-Arm Crosses (Mean ± SEM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intact Postpartum | 9 | 70 ± 12 | 25 ± 8 | 328 ± 13 | 37 ± 2 |

| OVX Pup Experienced | 10 | 80 ± 12 | 36 ± 7 | 364 ± 12 | 41 ± 2 |

| OVX Naïve | 11 | 86 ± 11 | 40 ± 7 | 354 ± 12 | 42 ± 2 |

Activity on the elevated plus maze. Mean time in seconds (± standard error) spent in open, outer open, and closed arms. Number of crosses between arms during the 10-minute test. There were no significant differences between groups.

Experiment 3: Maternal experience can potentiate maternal motivation in the absence of oestradiol

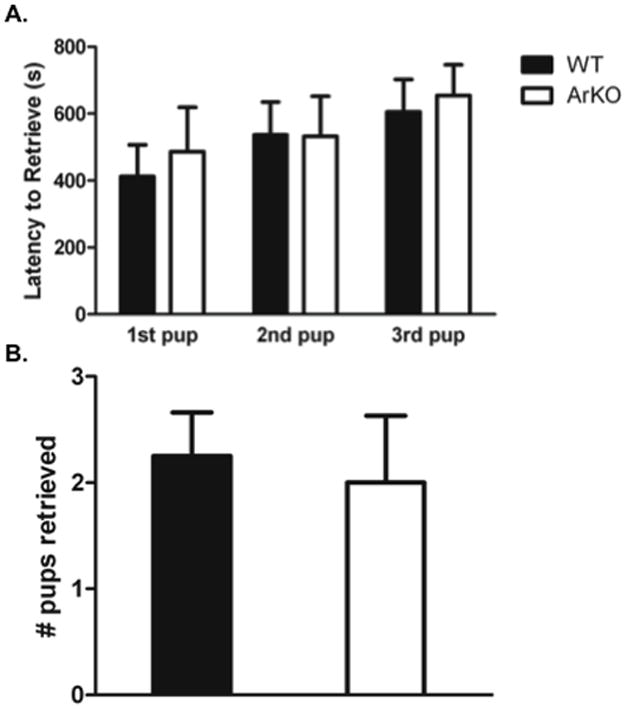

Overall, the maternal responsiveness (retrieval, licking, and nursing) of naive OVX WT mice was not significantly different from naive OVX ArKO mice. The latency to retrieve was not significantly different between WT and ArKO females across the 4 test days, but both groups retrieved pups faster as test day advanced [first pup (F(1,36)= 22.08, p< 0.01), Figure 4a; all pups (F(1,36)= 11.16, p< 0.01), Figure 4b]. There was also a main effect of test day on latency to crouch over all pups in the nest (F(1,36)= 11.32, p< 0.01; Figure 4c).

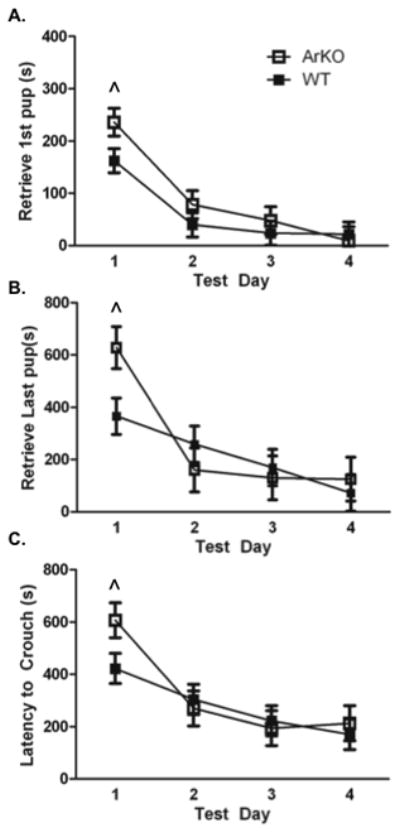

Figure 4.

Latency in seconds to the onset of maternal behaviour on test days 1–4 in ovariectomised wild type (WT, n= 8) and aromatase knockout (ArKO, n= 6) mice. A) Latency (s) to retrieve the first pup on test days 1–4. B) Latency (s) to retrieve all pups. C) Latency (s) to crouch over all four pups in the nest. ^ Significant trend across test days

There were no significant differences in maternal interactions between WT and ArKO females and pups in the nest. During the 15-minute observation, all females displayed significantly less licking across test day (F(1,36) = 7.08.30, p< 0.01, Table 3) and significantly more crouching across test day (F(1,36) = 8.69, p< 0.01). This pattern continued in the following hour observation (data not shown).

Table 3.

| Group | Test Day | Frequency pup contact ± SE | Frequency Licking ± SE | Frequency Crouching ± SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT n= 8 | 1 | 55 ± 2.1 | 21.9 ± 3.4 | 22 ± 5 |

| 2 | 55.3 ± 2.1 | 20.2 ± 3.4 | 21.8 ± 5 | |

| 3 | 59.5 ± 2.1 | 20.5 ± 3.4 | 32.5 ± 5 | |

| 4 | 58.8 ± 2.1 | 12.9 ± 3.4 | 44.4 ± 5 | |

| ArKO n= 6 | 1 | 54 ± 2.5 | 30.7 ± 3.9 | 18 ± 5.7 |

| 2 | 56.2 ± 2.5 | 27.5 ± 3.9 | 21.5 ± 5.7 | |

| 3 | 59.2 ± 2.5 | 19.7 ± 3.9 | 34.2 ± 5.7 | |

| 4 | 58.2 ± 2.5 | 8.2 ± 3.9 | 43.5 ± 5.7 | |

Number of observations (out of 60 total) in contact with pups, licking, or crouching during the 15 min observation. There was a statistically significant trend across test days to spend less time licking and more time crouching.

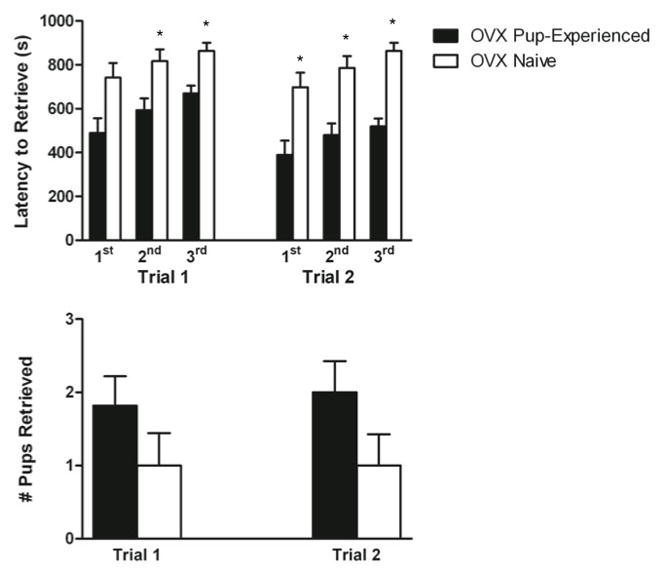

Because the results of Experiment 2 indicated that pup experience induced high levels of maternal responsiveness in ovariectomised virgin mice, we also examined whether 4 days of pup experience would facilitate pup retrieval on a novel T-maze in ArKO mice. There were no significant differences between WT and ArKO mice on latency to retrieve pups retrieval on the T-maze or in the number of pups retrieved (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Retrieval responses on a novel T-maze after 4 days of maternal behaviour testing. WT (n= 8) and ArKO (n= 6) females were ovariectomised. A) Latency (s) to retrieve each pup from the far ends of the T-maze. B) Number of pups retrieved from the far ends of the T-maze.

Experiment 4: Effects of pup experience are stable

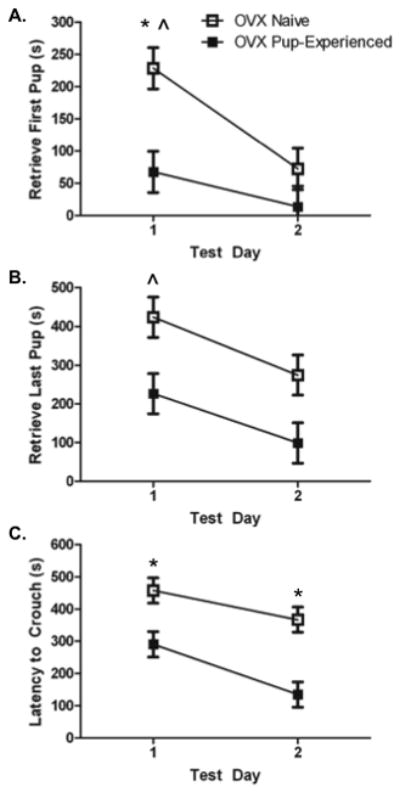

Pup-experienced females were faster to retrieve [first pup (F(1,20) = 5.88, p< 0.05), Figure 6a); all pups (F(1,20) = 6.65, p< 0.02, Figure 6b)] than pup-naive mice. There was a significant main effect of test day on latency to retrieve [first pup (F(1,20) =10.76, p< 0.02); all pups (F(1,20) = 7.11, p< 0.02)]. There was a significant trend to retrieve first and all pups faster across test day (p< 0.05). Pup-experienced females retrieved the first pup faster on test day 1 (p< 0.05). There was an effect of status and test day (F(1,20) = 9.38, 9.81, p< 0.01, respectively) on latency to crouch over all four pups (Figure 6c). Pup-experienced females crouched over pups faster on days 1–2 (p< 0.05).

Figure 6.

Latency (s) to the onset of maternal behaviour on test days 1-2. All females were ovariectomised. Naive females (n = 11) were not exposed to pups prior to maternal behaviour testing. Pup-experienced (n= 11) females were exposed to pups for 2 hours/day for 4 days. A) Latency (s) to retrieve the first pup on test days 1–2. B) Latency (s) to retrieve the last pups on test days 1–2. C) Latency (s) to crouch over all 4 pups in the nest on test days 1–2. * Significantly different from pup-experienced group ^ Significant trend across test days

During the 15-minute observation, pup-naive females displayed significantly more licking than pup-experienced females (F(1,20) = 11.87, p< 0.01, Table 4). Inversely, pup-experienced females show significantly more crouching than pup-naive females (F(1,20) = 12.12, p< 0.01). This pattern continued in the following hour observation (data not shown).

Table 4.

| Group | Test Day | Frequency pup contact ± SE | Frequency Licking ± SE | Frequency Crouching ± SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pup Exp n= 11 | 1 | 59 ± 1.3 | 15.4 ± 2.4* | 40.4 ± 3.1* |

| 2 | 58.8 ± 1.3 | 10.7 ± 2.4* | 45.2 ± 3.1* | |

| Naive n= 11 | 1 | 55.4 ± 1.3 | 28.9 ± 2.4 | 19.5 ± 3.1 |

| 2 | 57.5 ± 1.3 | 28.2 ± 2.4 | 26 ± 3.1 | |

Number of observations (out of 60 total) in contact with pups, licking, or crouching during the 15 min observation.

Significantly different from naive group on the same test day

Two days of pup exposure did not facilitate pup retrieval on the T-maze. Females that were naive to pups during the exposure phase were slower to retrieve the each pup (F(1,20) = 5.96, 7.56, 9.62 p< 0.05, respectively) from the ends of the T-maze when compared with pup-experienced females (Figure 7a). There was no effect of trial on latency to retrieve each pup. There were no differences in number of pups retrieved (Figure 7b).

Figure 7.

Retrieval responses on the T-maze after 2 days of maternal behaviour testing. Pup-experienced (n= 11) females received 4 days of pup exposure 1 week prior to maternal behaviour testing. Pup-naive (n= 11) females were not exposed to pups prior to the 2 days of maternal behaviour testing. Pup-experienced and pup naive females were ovariectomised. Trials 1 and 2 were separated by 30 days. A) Latency (s) to retrieve each pup from the far ends of the T-maze. B) Number of pups retrieved from the far ends of the T-maze. *Significantly different from the pup-experienced group

Discussion

Here we report that virgin females are slower to retrieve and crouch over pups, spend more time licking/grooming pups, and less time crouching over pups when compared to postpartum females. However, as test day advanced, virgins retrieved pups faster, spent less time licking/grooming, and more time crouching over pups. Similar changes in maternal responding across the first few days postpartum have previously been reported in primiparous mice, and therefore as virgin females gain more experience with pups, their behaviour more closely resembles that of a postpartum female (40). We speculate that crouching behaviour is not affected by the ability to lactate because ovariectomised pup-experienced females in Experiment 3–4 spent similar amounts of time crouching as postpartum lactating females in Experiment 1. Further, it has been reported that crouching behaviour is not dependent on the ability nurse because sensitised virgin rats show “nursing” behaviour which is more similar to postpartum suckled than non-suckled rats (41). Finally, whereas others have reported that postpartum and virgin females spend similar amounts of time with pups (14–16), the present study is the first to quantify pup-retrieval, licking/grooming, and crouching behaviour.

Unlike postpartum female rodents, virgin females do not show high levels of maternal motivation (16, 19–21, 23, 25, 30). Our results are in agreement with these reports, and indicate that OVX naive females are not responsive to pups on a novel T-maze. It has been suggested that experience with pups, in the absence of hormone stimulation, is not sufficient to induce maternal motivation in virgin females (20, 23, 25, 30). However, we found that even in the absence of circulating ovarian hormones (OVX), pup experience induced maternal motivation in virgin mice. One possibility is that differences exist in the sensitivity of different mouse strains to pup experience (20, 23, 30). In support of this idea, note that wild mice are unresponsive to pups even after multiple experiences with pups (42).

Although removal of the ovaries eliminates the majority of circulating steroid hormones, it is still possible that oestradiol synthesized in the brain (36, 43) during maternal experience could have facilitated pup retrieval on the T-maze. To rule out this possibility we assessed maternal responsiveness in OVX ArKO mice given 4 days of pup experience (2h/day) and then tested them on the T-maze along with OVX WT littermates. The fact that there were no significant differences in maternal responsiveness between groups in the home cage or on the T-maze indicates that the effects of maternal experience on maternal motivation were not dependent on oestradiol. Further, the fact that ArKO female mice, which have not been exposed to oestradiol at any point during development, are responsive to pups in the home cage and on the T-maze suggests that oestradiol is not necessary for spontaneous maternal behaviour. The results of Experiment 3 did not address whether the maternal responsiveness of ArKO mice is equivalent to mice that have exposed to circulating oestradiol (intact virgins) or parturitional hormones (intact postpartum). Based on the results of Experiment 2, we speculate that the retrieval behavior of ArKO females on the T-maze would not be significantly different from intact postpartum females. However, it is important to emphasize that intact postpartum females do not need 4 days of pup experience to show high levels of motivation (10, 20, 21, 25, 30), therefore the presence of oestradiol would certainly facilitate maternal responsiveness. What is significant about the present data is that they are the first to demonstrate that in B6 mice, maternal experience, even in the complete absence of oestradiol, is sufficient to induce high levels of maternal responsiveness.

The T-maze retrieval task requires that the female overcome her fearfulness of a novel environment in order to retrieve pups, therefore a relevant question is whether pup-experienced and postpartum females show a general reduction in anxiety which is related to their increased motivation to retrieve pups on the T-maze. Here we report that there are no significant differences in activity on the EPM between OVX naive, OVX pup-experienced, or intact postpartum females. This finding is suprising considering that motherhood in rodents has frequently been associated with a general reduction in anxiety (1, 44), which has been attributed both to the hormonal events of parturition, as well as mother-pup interaction (45–47). It is important to note, however, that anxiolytic responses on the EPM are dependent upon continual pup exposure. For example, as little as 4 hours of pup deprivation can eliminate differences in EPM behavior between virgin and lactating rats (46). Therefore, because the EPM test was conducted 24 hours after the last pup exposure, it is possible that intact postpartum females did not show the typical anxiolytic response on the EPM because they were not continually exposed to pups. Therefore, differences in pup retrieval on the T-maze are not related to a general reduction in anxiety, but might be related to a reduction in anxiety to pup stimuli, specifically (27).

Our data indicate that ovarian hormones, particularly oestradiol, are not required for maternal responsiveness, but this does not preclude a role for peptide hormones such as oxytocin (OT), vasopressin, and prolactin, all of which can affect maternal behaviour through direct actions on the brain (6, 43, 48–59). However, it is important to emphasize that the facilitatory effects of OT and prolactin on maternal behaviour are dependent upon intact ovaries or co-administration of oestradiol (8, 49, 52, 56). Therefore, although these hormones play an important role in maternal behaviour, it is unlikely that the facilitatory effects of pup-experience in ovariectomised mice are related to peptide hormones.

In Experiment 4 we addressed two questions about the effects of maternal experience on maternal motivation. First, how many days of pup exposure are necessary to produce effects on maternal motivation, and secondly, are the effects on maternal motivation long lasting. The results of Experiment 4 indicate that although 2 days of pup exposure facilitates pup retrieval in the home cage, OVX naive females with two days of maternal experience did not respond to pups on the T-maze. Further, one month following the initial exposure, OVX females that had a total of 6 days of pup experience (2 hours/day) continued to respond to pups on the T-maze, whereas females with 2 days of pup experience (2 hours/day) were still unresponsive. Therefore, subtle differences in pup exposure can influence the duration of experience-induced modifications in maternal behaviour.

The experience of interacting with pups likely produces modifications in gene transcription and the neural circuits that regulate maternal responsiveness so that during subsequent maternal interactions, pup stimuli come to elicit maternal responsiveness more effectively. The medial preoptic area (MPOA) is the critical neural region that responds to hormonal and sensory inputs from pup stimuli to affect the display of maternal behaviour (22, 60–69). Importantly, MPOA neurons show increased responsiveness as measured by increased Fos gene (70) and Fos protein expression (12) when virgin or ovariectomised female mice are interacting with pups. MPOA interaction with the mesolimbic dopamine (DA) system is critical for maternal responsiveness as well as the consolidation of maternal experience (for review see (71). Pup-experienced rats show significantly more DA release into nucleus accumbens (NA) in response to pups than naïve females (72) and blockade of DA D1 and D2 receptors in NA inhibits the consolidation of maternal responsiveness, such that DA antagonist treated females require significantly more pup exposure to induce maternal behaviour than control females (73). The mesolimbic DA system is also involved in maternal responding in mice. For example, maternal behaviour can be reinstated in olfactory bulbectomised mice following systemic treatment with apomorphine, a DA receptor agonist (74), and dopamine transporter knockout mice that are constantly exposed to supraphysiological amounts of DA show severe impairments in maternal behaviour (75). Further, hyperactivity of the mesolimbic DA system is associated with naturally occurring maternal neglect in some strains of mice (76).

Although it’s likely that the same neural circuits regulate maternal responsiveness in rats and mice, it is possible that the mechanisms through which maternal experience is consolidated are different. For example, in rats the experience of interacting with pups facilitates subsequent maternal responsiveness by increasing the activity of neural circuits that regulate approach as well decreasing activity in circuits that regulate pup avoidance (1). Whereas in mice, the occurrence of spontaneous maternal behavior suggests that neural circuits that regulate maternal responsiveness are already sensitive to pup stimuli. Therefore, experience with pups might specifically increase the sensitivity of neural circuits that regulate maternal motivation. This might explain why subtle differences in experience can impact maternal responsiveness in mice but not in rats. The molecular mechanisms through which maternal experience modifies these pathways will be resolved by our ongoing research.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Aileen Wills, Savera Shetty, and Michelle Edwards for their excellent technical assistance. We are indebted to Dr. Evan Simpson for providing us with the ArKO mice we used to establish our colony. This work has been supported by NIH T32 training grant # DK007646 and R01 MH057759.

References

- 1.Numan MI, TR . The neurobiology of parental behavior. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Noirot E. The onset of maternal behavior in rat, hamsters and mice. In: Lehrman DS, Hinde RA, Shaw E, editors. Advances in the study of behavior. New York: Academic Press; 1972. pp. 107–45. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenblatt JS. Nonhormonal basis of maternal behavior in the rat. Science. 1967;156:1512–4. doi: 10.1126/science.156.3781.1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas SA, Palmiter RD. Impaired maternal behavior in mice lacking norepinephrine and epinephrine. Cell. 1997;91:583–92. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80446-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mann MA, Kinsley C, Broida J, Svare B. Infanticide exhibited by female mice: genetic, developmental and hormonal influences. Physiol Behav. 1983;30:697–702. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(83)90165-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lucas BK, Ormandy CJ, Binart N, Bridges RS, Kelly PA. Null mutation of the prolactin receptor gene produces a defect in maternal behavior. Endocrinology. 1998;139:4102–7. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.10.6243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leussis MP, Bond TL, Hawken CM, Brown RE. Attenuation of maternal behavior in virgin CD-1 mice by methylphenidate hydrochloride. Physiol Behav. 2008;95:395–9. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Larsen CM, Kokay IC, Grattan DR. Male pheromones initiate prolactin-induced neurogenesis and advance maternal behavior in female mice. Horm Behav. 2008;53:509–17. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2007.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gandelman R, Vom Saal FS. Pup-killing in mice: the effects of gonadectomy and testosterone administration. Physiol Behav. 1975;15:647–51. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(75)90114-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gandelman R. The ontogeny of maternal responsiveness in female Rockland-Swiss albino mice. Horm Behav. 1973;4:257–68. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(73)90010-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gandelman R. Maternal behavior in the mouse: effect of estrogen and progesterone. Physiol Behav. 1973;10:153–5. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(73)90101-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Calamandrei G, Keverne EB. Differential expression of Fos protein in the brain of female mice dependent on pup sensory cues and maternal experience. Behav Neurosci. 1994;108:113–20. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.108.1.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leblond C. Nervous and hormonal factors in the maternal behavior of the mouse. The Journal of Genetic Psychology. 1940;57:327–44. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leblond C. Extra-hormonal factors in maternal behavior. Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine. 1938;38:66–70. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Noirot E. Changes in Responsiveness to Young in the Adult Mouse: The Effect of External Stimuli. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1964;57:97–9. doi: 10.1037/h0042864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gandelman R, Paschke RE, Zarrow MX, Denenberg VH. Care of young under communal conditions in the mouse (Mus musculus) Dev Psychobiol. 1970;3:245–50. doi: 10.1002/dev.420030405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stolzenberg DS, Numan M. Hypothalamic interaction with the mesolimbic DA system in the control of the maternal and sexual behaviors in rats. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35:826–47. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Numan M, Woodside B. Maternity: neural mechanisms, motivational processes, and physiological adaptations. Behav Neurosci. 2010;124:715–41. doi: 10.1037/a0021548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stern JM, Mackinnon DA. Postpartum, hormonal, and nonhormonal induction of maternal behavior in rats: effects on T-maze retrieval of pups. Horm Behav. 1976;7:305–16. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(76)90036-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gandelman R, Zarrow MX, Denenberg VH. Maternal Behavior: Differences between mother and virgin mice as a function of testing procedure. Developmental Psychobiology. 1973;3 :207–14. doi: 10.1002/dev.420030308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bridges R, Zarrow MX, Gandelman R, Denenberg VH. Differences in maternal responsiveness between lactating and sensitized rats. Dev Psychobiol. 1972;5:123–7. doi: 10.1002/dev.420050205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee A, Clancy S, Fleming AS. Mother rats bar-press for pups: effects of lesions of the mpoa and limbic sites on maternal behavior and operant responding for pup-reinforcement. Behav Brain Res. 2000;108:215–31. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(99)00170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hauser H, Gandelman R. Lever pressing for pups: evidence for hormonal influence upon maternal behavior of mice. Horm Behav. 1985;19:454–68. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(85)90041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koch M, Ehret G. Estradiol and parental experience, but not prolactin are necessary for ultrasound recognition and pup-retrieving in the mouse. Physiol Behav. 1989;45:771–6. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(89)90293-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohen JB, RS Retention of maternal behavior in nulliparous and primiparous rats: Effects of duration of previous maternal experience. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology. 1981;95:450–9. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seip KM, Morrell JI. Exposure to pups influences the strength of maternal motivation in virgin female rats. Physiol Behav. 2008;95:599–608. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scanlan VF, Byrnes EM, Bridges RS. Reproductive experience and activation of maternal memory. Behav Neurosci. 2006;120:676–86. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.120.3.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fleming AS, Korsmit M, Deller M. Rat pups are potent reinforcers to the maternal animal: Effects of experience, parity, hormones, and dopamine function. Psychobiology. 1994;22 :44–53. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ehret GKM, Haack B, Markl H. Sex and parental experience determine the onset of an instinctive behavior in mice. Naturwissenschaften. 1989;74:47. doi: 10.1007/BF00367047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ehret G, Koch M. Ultrasound-inuced parental behaviour in house mice is controlled by female sex hormones and parental experience. Ethology. 1989:81–93. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Orpen BG, Fleming AS. Experience with pups sustains maternal responding in postpartum rats. Physiol Behav. 1987;40:47–54. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(87)90184-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bridges RS. Parturition: Its role in the long term retention of maternal behavior in the rat. Physiology and Behavior. 1977;18:487–90. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bridges RS. Long-term effects of pregnancy and parturition upon maternal responsiveness in the rat. Physiol Behav. 1975;14:245–9. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(75)90028-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kudwa AE, Boon WC, Simpson ER, Handa RJ, Rissman EF. Dietary phytoestrogens dampen female sexual behavior in mice with a disrupted aromatase enzyme gene. Behav Neurosci. 2007;121:356–61. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.121.2.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taziaux M, Keller M, Bakker J, Balthazart J. Sexual behavior activity tracks rapid changes in brain estrogen concentrations. J Neurosci. 2007;27:6563–72. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1797-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robertson KM, O’Donnell L, Jones ME, Meachem SJ, Boon WC, Fisher CR, Graves KH, McLachlan RI, Simpson ER. Impairment of spermatogenesis in mice lacking a functional aromatase (cyp 19) gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:7986–91. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.7986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dalla C, Antoniou K, Papadopoulou-Daifoti Z, Balthazart J, Bakker J. Oestrogen-deficient female aromatase knockout (ArKO) mice exhibit depressive-like symptomatology. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20:217–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stern JM, Johnson SK. Ventral somatosensory determinants of nursing behavior in Norway rats. I. Effects of variations in the quality and quantity of pup stimuli. Physiol Behav. 1990;47:993–1011. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(90)90026-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Imwalle DB, Gustafsson JA, Rissman EF. Lack of functional estrogen receptor beta influences anxiety behavior and serotonin content in female mice. Physiol Behav. 2005;84:157–63. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Champagne FA, Curley JP, Keverne EB, Bateson PP. Natural variations in postpartum maternal care in inbred and outbred mice. Physiol Behav. 2007;91:325–34. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lonstein JS, Wagner CK, De Vries GJ. Comparison of the “nursing” and other parental behaviors of nulliparous and lactating female rats. Horm Behav. 1999;36:242–51. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1999.1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Soroker VTJ. Changes in incidence of infanticidal and parental responses during the reproductive cycle in male and female wild mice Mus musculus. Animal Behavior. 1988;36:1275–81. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takayanagi Y, Yoshida M, Bielsky IF, Ross HE, Kawamata M, Onaka T, Yanagisawa T, Kimura T, Matzuk MM, Young LJ, Nishimori K. Pervasive social deficits, but normal parturition, in oxytocin receptor-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:16096–101. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505312102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maestripieri D, D’Amato FR. Anxiety and maternal aggression in house mice (Mus musculus): a look at interindividual variability. J Comp Psychol. 1991;105:295–301. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.105.3.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pereira M, Uriarte N, Agrati D, Zuluaga MJ, Ferreira A. Motivational aspects of maternal anxiolysis in lactating rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;180:241–8. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-2157-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lonstein JS. Reduced anxiety in postpartum rats requires recent physical interactions with pups, but is independent of suckling and peripheral sources of hormones. Horm Behav. 2005;47:241–55. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Agrati D, Zuluaga MJ, Fernandez-Guasti A, Meikle A, Ferreira A. Maternal condition reduces fear behaviors but not the endocrine response to an emotional threat in virgin female rats. Horm Behav. 2008;53:232–40. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pedersen CA, Caldwell JD, Walker C, Ayers G, Mason GA. Oxytocin activates the postpartum onset of rat maternal behavior in the ventral tegmental and medial preoptic areas. Behav Neurosci. 1994;108:1163–71. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.108.6.1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pedersen CA, Ascher JA, Monroe YL, Prange AJ., Jr Oxytocin induces maternal behavior in virgin female rats. Science. 1982;216:648–50. doi: 10.1126/science.7071605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bosch OJ, Neumann ID. Brain vasopressin is an important regulator of maternal behavior independent of dams’ trait anxiety. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:17139–44. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807412105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kessler MS, Bosch OJ, Bunck M, Landgraf R, Neumann ID. Maternal care differs in mice bred for high vs. low trait anxiety: Impact of brain vasopressin and cross-fostering. Soc Neurosci. 2010:1–13. doi: 10.1080/17470919.2010.495567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pedersen CA, Prange AJ., Jr Induction of maternal behavior in virgin rats after intracerebroventricular administration of oxytocin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979;76:6661–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.12.6661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yu GZ, Kaba H, Okutani F, Takahashi S, Higuchi T. The olfactory bulb: a critical site of action for oxytocin in the induction of maternal behaviour in the rat. Neuroscience. 1996;72:1083–8. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00600-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ragnauth AK, Devidze N, Moy V, Finley K, Goodwillie A, Kow LM, Muglia LJ, Pfaff DW. Female oxytocin gene-knockout mice, in a semi-natural environment, display exaggerated aggressive behavior. Genes Brain Behav. 2005;4:229–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2005.00118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pedersen CA, Vadlamudi SV, Boccia ML, Amico JA. Maternal behavior deficits in nulliparous oxytocin knockout mice. Genes Brain Behav. 2006;5:274–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2005.00162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pedersen CA, Caldwell JD, Johnson MF, Fort SA, Prange AJ., Jr Oxytocin antiserum delays onset of ovarian steroid-induced maternal behavior. Neuropeptides. 1985;6:175–82. doi: 10.1016/0143-4179(85)90108-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nishimori K, Young LJ, Guo Q, Wang Z, Insel TR, Matzuk MM. Oxytocin is required for nursing but is not essential for parturition or reproductive behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:11699–704. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Macbeth AH, Stepp JE, Lee HJ, Young WS, 3rd, Caldwell HK. Normal maternal behavior, but increased pup mortality, in conditional oxytocin receptor knockout females. Behav Neurosci. 2010;124:677–85. doi: 10.1037/a0020799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.D’Cunha TM, King SJ, Fleming AS, Levy F. Oxytocin receptors in the nucleus accumbens shell are involved in the consolidation of maternal memory in postpartum rats. Horm Behav. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Numan M, Rosenblatt JS, Komisaruk BR. Medial preoptic area and onset of maternal behavior in the rat. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1977;91:146–64. doi: 10.1037/h0077304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Numan M, Corodimas KP, Numan MJ, Factor EM, Piers WD. Axon-sparing lesions of the preoptic region and substantia innominata disrupt maternal behavior in rats. Behav Neurosci. 1988;102:381–96. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.102.3.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Numan M, Callahan EC. The connections of the medial preoptic region and maternal behavior in the rat. Physiol Behav. 1980;25:653–65. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(80)90367-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Numan M. Medial preoptic area and maternal behavior in the female rat. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1974;87:746–59. doi: 10.1037/h0036974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lee AW, Brown RE. Comparison of medial preoptic, amygdala, and nucleus accumbens lesions on parental behavior in California mice (Peromyscus californicus) Physiol Behav. 2007;92 :617–28. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kalinichev M, Rosenblatt JS, Morrell JI. The medial preoptic area, necessary for adult maternal behavior in rats, is only partially established as a component of the neural circuit that supports maternal behavior in juvenile rats. Behav Neurosci. 2000;114:196–210. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.114.1.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jacobson CD, Terkel J, Gorski RA, Sawyer CH. Effects of small medial preoptic area lesions on maternal behavior: retrieving and nest building in the rat. Brain Res. 1980;194:471–8. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)91226-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gray P, Brooks PJ. Effect of lesion location within the medial preoptic-anterior hypothalamic continuum on maternal and male sexual behaviors in female rats. Behav Neurosci. 1984;98:703–11. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.98.4.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fleming AS, Miceli M, Moretto D. Lesions of the medial preoptic area prevent the facilitation of maternal behavior produced by amygdala lesions. Physiol Behav. 1983;31:503–10. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(83)90073-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Arrati PG, Carmona C, Dominguez G, Beyer C, Rosenblatt JS. GABA receptor agonists in the medial preoptic area and maternal behavior in lactating rats. Physiol Behav. 2006;87:51–65. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kuroda KO, Meaney MJ, Uetani N, Fortin Y, Ponton A, Kato T. ERK-FosB signaling in dorsal MPOA neurons plays a major role in the initiation of parental behavior in mice. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2007;36:121–31. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Numan M, Stolzenberg DS. Medial preoptic area interactions with dopamine neural systems in the control of the onset and maintenance of maternal behavior in rats. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2009;30:46–64. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Afonso VM, Grella SL, Chatterjee D, Fleming AS. Previous maternal experience affects accumbal dopaminergic responses to pup-stimuli. Brain Res. 2008;1198:115–23. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Parada M, King S, Li M, Fleming AS. The roles of accumbal dopamine D1 and D2 receptors in maternal memory in rats. Behav Neurosci. 2008;122:368–76. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.122.2.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sato A, Nakagawasai O, Tan-No K, Onogi H, Niijima F, Tadano T. Effect of non-selective dopaminergic receptor agonist on disrupted maternal behavior in olfactory bulbectomized mice. Behav Brain Res. 2010;210:251–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Spielewoy C, Roubert C, Hamon M, Nosten-Bertrand M, Betancur C, Giros B. Behavioural disturbances associated with hyperdopaminergia in dopamine-transporter knockout mice. Behav Pharmacol. 2000;11:279–90. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200006000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gammie SC, Edelmann MN, Mandel-Brehm C, D’Anna KL, Auger AP, Stevenson SA. Altered dopamine signaling in naturally occurring maternal neglect. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1974. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]