Abstract

Purpose

A combined chemotherapy of taxane and platinum, with or without anthracycline, has been used as a standard first-line regimen. The purpose of this study was to investigate the effectiveness of second-line chemotherapy for treatment of advanced or recurrent endometrial carcinoma previously treated with a combined chemotherapy of taxane and platinum, with or without anthracycline.

Methods

During the 2000–2008 study period, 723 patients were diagnosed with endometrial cancer at the Departments of Obstetrics and Gynecology of the Osaka University and the Osaka Rosai Hospitals, Osaka, Japan. The subset of these cases that eventually required treatment by second-line chemotherapy was retrospectively analyzed.

Results

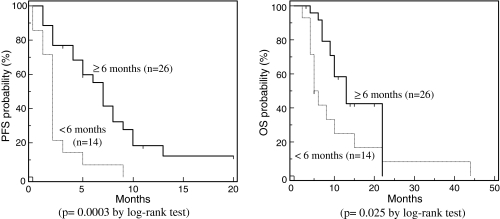

Response rate to second-line chemotherapy was 25%. Treatment-free interval (TFI) of ≥ or <6 months was demonstrated to be significantly associated with the response to second-line chemotherapy (P = 0.0026), progression-free survival (P = 0.0003) and overall survival (P = 0.025). The second-line chemotherapy similar to the first-line regimen was ineffective in all the 7 cases (100%) whose TFI was shorter than 6 months. Multivariate analysis showed that TFI was the most significantly important factor predicting the effectiveness of second-line chemotherapy (the adjusted hazard ratio of TFI on PFS and OS: 3.482, 95% CI, 1.641–7.388, P = 0.0012, and 2.341, 95% CI, 1.034–5.301, P = 0.042, respectively).

Conclusions

Our present study provides, for the first time, evidence that the majority of refractory or recurrent diseases, if they occur within 6 months of a first-line chemotherapy using taxane and platinum with or without anthracycline, are non-responsive to the current regimens of second-line chemotherapy.

Keywords: Endometrial cancer, Second-line chemotherapy, Response, Treatment-free interval, Progression-free survival, Overall survival

Introduction

The incidence of endometrial carcinoma, already the most common malignancy of the female pelvis and the fourth most common cancer among women in the United States, has been increasing steadily during the last three decades [1]. In approximately 75% of patients, the tumor is still confined to the uterus at diagnosis (FIGO stage I), and thus, there is a good prognosis [2]. However, the prognosis for advanced endometrial carcinomas, with extra-pelvic metastatic dissemination, is extremely poor, and the 5-year survival rate is a mere 5–32% [1]. Irradiation was usually performed as post-operative adjuvant therapy for early cases considered being at risk of recurrence and for most advanced cases [3]. Recently, systemic adjuvant chemotherapy, compared to adjuvant irradiation, was reported to significantly improve the prognosis of these cases [4, 5].

About one-fourth of those patients, treated for what was thought to be an early-stage endometrial cancer, go onto develop a recurrence. Unfortunately, 3–19 years after treatment for the recurrence, only 7.7% of the patients were alive and without evidence of disease [3]. Recurrences, restricted to the vaginal vault, are relatively better treated with radiotherapy. However, in most cases of relapse, the disease had spread to other sites, including pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes, the peritoneum of the pelvis and abdominal cavity, and the lungs. For these cases, systemic chemotherapy is usually required.

Cisplatin and doxorubicin were shown to be the most effective drugs for both advanced and recurrent endometrial carcinomas; paclitaxel was also reported to be useful [6, 7]. A Gynecologic Oncology Group’s (GOG) study showed that a tripartite regimen of the Taxane paclitaxel, plus the Anthracycline doxorubicin and the Platinum drug cisplatin (TAP), provided a better response, as measured by progression-free and overall survival rates, than without the taxane (AP). However, there were significant adverse side effects in the TAP group [8]. A modified TAP regimen, with the Taxane paclitaxel and Epirubicin (a semi-synthetic stereoisomer of doxorubicin) plus the Platinum drug cisplatin (TEP), was a more effective combination chemotherapy, with a 73% response rate for advanced endometrial carcinomas, suggesting a possible future role of TEP therapy as the first-line treatment for advanced endometrial carcinomas [9]. A combination chemotherapy of the Taxane paclitaxel and Carboplatin (TC), which is a standard regimen for ovarian carcinoma, was also shown to be a well-tolerated, active adjuvant therapy regimen for advanced endometrial carcinomas [10]. More recently, a combination chemotherapy of the Taxane paclitaxel, Epirubicin and Carboplatin (TEC) was demonstrated to be active and tolerable in patients with advanced metastatic and recurrent endometrial carcinomas [11].

Based on these findings, a combined chemotherapy of taxane and platinum, with or without anthracycline, has been used as a standard first-line regimen for both unresected and recurrent endometrial carcinomas and also as an adjuvant therapy for resected cases with a high risk of recurrence. However, a second-line regimen for the treatment of advanced or recurrent endometrial carcinoma previously treated with a combined chemotherapy of taxane and platinum, with or without anthracycline, has yet to be established. We hoped our findings would change that. In our current study, the effectiveness of second-line chemotherapy and the various clinical factors that associate with the prognosis of advanced or recurrent endometrial carcinoma previously treated with a combination chemotherapy of taxane and platinum, with or without anthracycline, were retrospectively investigated.

Materials and methods

Materials

Patients’ characteristics

During the 9-year study period of 2000–2008, we diagnosed 723 endometrial carcinomas in Japanese women at the Departments of Obstetrics and Gynecology of the Osaka University and the Osaka Rosai Hospitals, Osaka, Japan. Traditionally, our department has used either a monthly delivered combination of Taxane (paclitaxel) and Carboplatin (with, or without, the anthracycline Epirubicin, TEC or TC, respectively) or a weekly administered TC regimen as the first-line adjuvant therapy for resected endometrial carcinomas and also as the first-line salvage therapy for unresected and recurrent diseases. Patients were enrolled in the present study, after obtaining their written informed consent, if they were treated by a second-line chemotherapy for their recurrent disease, after first having an initial first-line adjuvant or salvage TEC or TC therapy.

In the initial first-line monthly TEC (TECm) treatment, paclitaxel (150 mg/m2), carboplatin (AUC = 4) and epirubicin (50 mg/m2) were administered intravenously every 3–4 weeks. The dose of chemotherapy drugs appropriate for our Japanese population was determined in phase I/II studies we had previously conducted (to be described in detail elsewhere). In the monthly TC (TCm) therapy, paclitaxel (175 mg/m2) and carboplatin (AUC = 5) were also administered intravenously every 3–4 weeks, based on previous reports [12, 13]. In the weekly TC regimen (TCw), paclitaxel (80 mg/m2) and carboplatin (AUC = 2) were administered intravenously on days 1, 8 and 15 on a 4-week cycle [14, 15].

The clinicopathological features of these cases, including the age of the patient, the histology and initial stage of the disease and the regimen of the first and second-line chemotherapies, were retrospectively reviewed utilizing their clinical records, including physical examination notes, radiological reports, operative records and histopathology reports. The histological diagnoses were made by authorized pathologists from the Department of Pathology of the Osaka University and the Osaka Rosai Hospitals.

Methods

In order to evaluate the therapeutic effect of second-line chemotherapy, previously described standard criteria from the World Health Organization [16] and others (Pectasides et al. [17–19] were used. The tumors were assessed with a CT scan and/or MRI at baseline and every three treatment courses thereafter. A complete response (CR) was defined as the disappearance of all known disease, determined by two observations not less than 4 weeks apart. Partial response (PR) was defined as a 50% or more reduction in the summed products of the two largest perpendicular dimensions of bi-dimensionally measurable lesions, for at least 4 weeks. Stable disease (SD) was defined as a less than 50% decrease, or a less than 25% increase, of tumor size, with no new detectable lesions. Progressive disease (PD) was defined as a greater than 25% increase in tumor size or as the appearance of new lesions.

Progression-free survival (PFS) was measured from the date of the last administration of chemotherapy to the date of the radiological or pathological relapse or to the date of the last follow-up. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the period from the start of chemotherapy to the patient’s disease-specific death or to the date of the last follow-up, as previously described [10]. Treatment-free interval (TFI) was defined as the period between the last administration of first-line chemotherapy and the initiation of the second-line chemotherapy, as previously described [20].

Second-line chemotherapy

Some patients received TECm or TCw (as described above) as second-line chemotherapy. Others were given docetaxel (30 mg/m2) and CPT-11 (60 mg/m2) (docetaxel + CPT) on days 1 and 8, on a 3–4-week cycles, or daily oral medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) (400–600 mg/day). The dose and schedule of administration of docetaxel + CPT appropriate for our Japanese population was also determined in our previous phase I/II study (to be described in detail elsewhere).

Statistical analysis of effect of second-line chemotherapy

The association between sensitivity to second-line chemotherapy and sensitivity to a TFI was analyzed by Fisher’s exact test. PFS curves determined by a TFI were constructed using the Kaplan–Meier method and were evaluated for statistical significance by the log-rank test. The multivariate Cox proportional hazards model was used to calculate the significant factors contributing to PFS after second-line chemotherapy. Results were considered to be significant when the P value was <0.05.

Results

Clinical characteristics of the study cases

During the 9-year study period, 40 patients required a second-line chemotherapy treatment against a recalcitrant or recurrent disease, after having first received an adjuvant or salvage first-line chemotherapy using TECm, TCm or TCw. The clinicopathological characteristics of these 40 patients are shown in Table 1. Eighty percent (32 out of 40 cases) of the patients received first-line TECm therapy; the other eight cases underwent either monthly or weekly TC (TCm or TCw) therapy, prior to the second-line chemotherapy. No cases were canceled due to second-line chemotherapy toxicity.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the study cases

| Characteristics | Patients (n = 40) | |

|---|---|---|

| Number | % | |

| Age (years) | ||

| <60 | 18 | 45 |

| ≥60 | 22 | 55 |

| Histology | ||

| Endometrioid | 32 | 80 |

| Serous | 4 | 10 |

| Clear cell | 1 | 3 |

| Others | 3 | 8 |

| Initial stage | ||

| I | 10 | 25 |

| II | 6 | 15 |

| III | 19 | 48 |

| IV | 5 | 13 |

| First-line chemotherapy | ||

| TEC | 32 | 80 |

| TC | 7 | 18 |

| Weekly TC | 1 | 3 |

All patients received first-line chemotherapy using taxane and carboplatin (with or without epirubicin, TC/TEC)

TECm monthly administration of taxane (paclitaxel), epirubicin and carboplatin, TCm monthly administration of paclitaxel and carboplatin, TCw weekly administration of paclitaxel and carboplatin

Outcome of the patients after second-line chemotherapy

Among the 40 patients, 24 patients received second-line TECm, TCm or TCw, 3 received docetaxel + CPT, 7 received oral MPA therapy, and 6 received oral Etoposide therapy (Table 2). The overall response rate for second-line chemotherapy was 25% (0–38%). The PFS was 3.5 months (0–20 months), and the OS was 10 months (2–44 months). The response rate, PFS, and OS were not significantly different among the TECm/TCm/TCw, docetaxel + CPT, MPA and Etoposide groups.

Table 2.

Outcome of the patients after second-line chemotherapy

| Cases | Response rate | PFS | OS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (%) | (months) | (months) | ||

| TEC/weekly TC | 24 | 38 | 5.5 (2–20) | 13 (3–44) |

| Docetaxel + CPT-11 | 3 | 33 | 4 (0–5) | 6 (4–10) |

| MPA (oral) | 7 | 0 | 1 (0–3) | 5 (2–22) |

| Etoposide (oral) | 6 | 0 | 2 (1–8) | 9 (4–11) |

| Total | 40 | 25 | 3.5 (0–15) | 10 (2–44) |

No significant difference was demonstrated among the four groups (TECm/TCm/TCw, docetaxel + CPT, MPA and Etoposide)

TECm monthly administration of paclitaxel, epirubicin and carboplatin, TCw weekly administration of paclitaxel and carboplatin, TCm monthly administration of paclitaxel and carboplatin, MPA oral daily medroxyprogesterone acetate, Etoposide oral daily Etoposide, PFS progression-free survival, OS overall survival

Association between TFI and sensitivity to second-line chemotherapy

The effect of a TFI, after first-line chemotherapy using TC/TEC, on the tumor’s sensitivity to second-line chemotherapy was evaluated. Among the 24 patients whose TFI was equal to or longer than 6 months, CR or PR was achieved in 10 patients (42%). However, all 16 cases (100%) whose TFI was shorter than 6 months exhibited either SD or PD against the second-line chemotherapy. This association between TFI and sensitivity to a second-line chemotherapy was statistically significant (P = 0.0026 by Fisher’s exact test). These results are tabulated in Table 3.

Table 3.

Association between TFI and effectiveness of second-line chemotherapy

| CR/PR | SD/PD | |

|---|---|---|

| TFI ≥ 6 months | 10 (42%)a | 14 (58%) |

| TFI < 6 months | 0 (0%) | 16 (100%)a |

Forty-two percent (10 out of 24 cases) of the patients whose TFI was equal to or longer than 6 months exhibited sensitivity to second-line chemotherapy; however, all cases whose TFI was shorter than 6 months were resistant to second-line chemotherapy. This association was statistically significant (P = 0.0026 by Fisher’s exact test)

TFI treatment-free interval, CR complete response, PR partial response, SD stable disease, PD progressive disease

a P = 0.0026

Association between TFI and sensitivity to second-line chemotherapy using taxane and platinum, with or without anthracycline, was, next, analyzed. Among the 17 patients whose TFI was equal to or longer than 6 months, CR or PR was achieved in 9 patients (53%). However, all 7 cases (100%) whose TFI was shorter than 6 months exhibited either SD or PD against the second-line chemotherapy. This association between TFI and sensitivity to a second-line chemotherapy was statistically significant (P = 0.015 by Fisher’s exact test). These results are tabulated in Table 4.

Table 4.

Association between TFI and sensitivity to second-line chemotherapy using taxane and platinum, with or without anthracycline

| CR/PR | SD/PD | |

|---|---|---|

| TFI ≥ 6 months | 9 (53%)a | 8 (47%) |

| TFI < 6 months | 0 (0%) | 7 (100%)a |

Fifty-three percent (9 out of 17 cases) of the patients whose TFI was equal to or longer than 6 months exhibited sensitivity to second-line chemotherapy; however, all cases whose TFI was shorter than 6 months were resistant to second-line chemotherapy. This association was statistically significant (P = 0.015 by Fisher’s exact test)

TFI treatment-free interval, CR complete response, PR partial response, SD stable disease, PD progressive disease

a P = 0.015

PFS and OS after second-line chemotherapy by TFI

The differences by TFI in the effectiveness of second-line chemotherapy regimens were investigated. The median PFS was 7 months (1–20 months) for the 26 patients whose TFI was equal to or longer than 6 months, which was significantly longer than the 2 months (0–9 months) for the 14 whose TFI was shorter than 6 months (P = 0.0003 by log-rank test) (Fig. 1). The median OS was 13 months (3–22 months) for the 26 patients whose TFI was equal to or longer than 6 months, which was significantly longer than the 5.5 months (2–44 months) for the 14 whose TFI was shorter than 6 months (P = 0.025 by log-rank test) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PFS and OS after second-line chemotherapy by TFI. Progression-free probability and overall probability after second-line chemotherapy of the patients whose TFI was equal to or longer than 6 months were significantly longer than those whose TFI was shorter than 6 months (P = 0.0003 and P = 0.025, respectively, by the log-rank test)

Multivariate Cox proportional hazards analysis for effectiveness of second-line chemotherapy on PFS and OS

In order to further support our finding that a TFI was significantly associated with the effectiveness of second-line chemotherapy, the multivariate Cox proportional hazards model was utilized. The results are listed in Table 4. The adjusted hazard ratio (HR) of TFI (≥6 months versus <6 months) on PFS was 3.482 (95% CI, 1.641–7.388) and that of TFI on OS was 2.341 (95% CI, 1.034–5.301). TFI was demonstrated to be a significant factor in predicting for PFS and OS (P = 0.0012 and P = 0.042, respectively, based on the multivariate Cox proportional hazards model) (Tables 5 and 6).

Table 5.

Multivariate Cox proportional hazards analysis for effectiveness of second-line chemotherapy on PFS

| Variable | Adjusted HR | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.14 | ||

| <60 | 1 | ||

| ≥60 | 0.573 | 0.274–1.197 | |

| Histology | 0.53 | ||

| Endometrioid | 1 | ||

| Non-endometrioid | 1.331 | 0.546–3.247 | |

| Initial stage | 0.82 | ||

| I/II | 1 | ||

| III/IV | 1.092 | 0.517–2.308 | |

| TFI | 0.0012 | ||

| ≥6 months | 1 | ||

| <6 months | 3.482 | 1.641–7.388 |

The adjusted HR of TFI < 6 months was 3.482 (95% CI, 1.641–7.388), compared to TFI ≥ 6 months, showing statistical significance (P = 0.0012)

HR hazard ratio, TFI treatment-free interval

Table 6.

Multivariate Cox proportional hazards analysis for effectiveness of second-line chemotherapy on OS

| Variable | Adjusted HR | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.081 | ||

| <60 | 1 | ||

| ≥60 | 0.497 | 0.228–1.085 | |

| Histology | 0.40 | ||

| Endometrioid | 1 | ||

| Non-endometrioid | 1.497 | 0.590–3.800 | |

| Initial stage | 0.30 | ||

| I/II | 1 | ||

| III/IV | 1.613 | 0.658–3.953 | |

| TFI | 0.042 | ||

| ≥6 months | 1 | ||

| <6 months | 2.341 | 1.034–5.301 |

The adjusted HR of TFI < 6 months was 2.341 (95% CI, 1.034–5.301), compared to TFI ≥ 6 months, showing statistical significance (P = 0.042)

HR hazard ratio, TFI treatment-free interval

Conclusions

Endometrial adenocarcinoma is increasingly the most common malignancy of the female pelvis in the United States [1]. Although early-stage endometrial carcinomas have a good prognosis [2], the prognoses for advanced or recurrent cases are extremely poor (except for recurrences limited to the vaginal vault, which can generally be treated successfully with surgery and radiation therapy) [3]. Although a truly successful treatment for advanced or recurrent endometrial carcinomas has yet to be established, taxane and platinum (with or without anthracycline, TC/TEC) have demonstrated at least a partial efficacy [6–11].

Recently, based on these findings, the combined chemotherapy of TC/TEC has been used as a standard first-line regimen for unresected and recurrent endometrial carcinomas as well as an adjuvant therapy for resected cases with a high risk of recurrence. However, an effective second-line regimen for advanced or recurrent endometrial carcinomas previously treated with TC/TEC has not yet been established.

In our present study, we analyzed the outcomes of patients who, after having received a first-line TC or TEC chemotherapy, received a variety of second-line chemotherapy against relapsed or recurrent tumors. The overall response rate to second-line chemotherapy was 25% (0–38%). The PFS was 3.5 months (0–20 months), and the OS was 10 months (2–44 months). The response rates, PFS and OS did not differ significantly by the regimen of second-line chemotherapy. Therefore, other factors associated with the response to second-line chemotherapy were investigated.

In the related field of ovarian carcinomas, a TFI has consistently been shown to be the most important factor in the prediction of the response to the second-line chemotherapy [21–24]. Patients with ovarian tumor who relapse within 6 months have a disease that is significantly more likely to be both resistant to the original drugs and to have a lower response rate to new chemotherapy; however, those who relapse after 6 months from a first-line platinum-based chemotherapy have a higher chance of responding well, either to a re-challenge with a platinum-based treatment or to other agents [21].

However, comparable predictive factors for the response to second-line chemotherapy have not been established for endometrial carcinomas. It was yet to be determined whether TFI predicts a response to second-line chemotherapy, and if so, whether 6 months was a reasonable critical threshold that would suggest the clinical outcome after second-line chemotherapy. It was also unclear which current regimen is most effective as a second-line chemotherapy for endometrial carcinoma.

In our study, a TFI greater or less than 6 months was demonstrated to be significantly associated with the tumor’s likely responsiveness to a second-line chemotherapy (P = 0.0026 by Fisher’s exact test). The current study also showed that the association between TFI and sensitivity to a second-line TECm, TCm or TCw was statistically significant (P = 0.015 by Fisher’s exact test), indicating that second-line chemotherapy using taxane and platinum, with or without anthracycline, was not effective for those whose TFI was shorter than 6 months after initial treatment using taxane and platinum, with or without anthracycline.

PFS and OS were also shown to relate to a TFI ≥ or <6 months (P = 0.0003 and P = 0.025, respectively, by the log-rank test). As in ovarian tumors, multivariate analysis showed that the TFI for endometrial tumors was also the most significant factor for predicting the effectiveness of a second-line chemotherapy (the adjusted HR of TFI (≥6 months versus <6 months) on PFS: 3.482 (95% CI, 1.641–7.388), and that on OS: 2.341 (95% CI, 1.034–5.301)). TFI was demonstrated to be a significant factor in predicting for PFS and OS (P = 0.0012 and P = 0.042, respectively, based on the multivariate Cox proportional hazards model).

These results imply, for the first time, that the standard strategy for ovarian carcinoma second-line chemotherapy can now be applied to endometrial carcinoma as well. Endometrial carcinomas that relapse at least 6 months after first-line chemotherapy using TC/TEC have a significantly higher chance of responding to second-line chemotherapy. However, the tumors that relapse before 6 months are likely to be resistant. In fact, none of the currently popular regimens of chemotherapy (including the same as, or other than, the first-line regimen) were effective, and the PFS and OS were only 2 months (0–9 months) and 5.5 months (2–44 months), respectively (data not shown). Palliative care in these cases, rather than second-line chemotherapy, may for now be more appropriate.

Our present study provides, for the first time, good evidence that relapsed or recurrent diseases found within 6 months from a first-line chemotherapy regimen using taxane and platinum (with or without anthracycline) fail to respond to second-line chemotherapy. Further investigation is still required to establish an efficacious strategy for second-line chemotherapy for advanced or recurrent endometrial cancer.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. G. S. Buzard, CDCP and Jonathan Mitchell, Virginia Technical University, for their constructive critique and editing of our manuscript.

Conflicts of interest statement

This study was approved by our Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee. There are no conflicts of interest between the authors related to the research being reported.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Abbreviations

- CR

Complete response

- HR

Hazard ratio

- OS

Overall survival

- PD

Progressive disease

- PFS

Progression-free survival

- PR

Partial response

- RR

Response rate

- SD

Stable disease

- TFI

Treatment-free interval

- CAP

Cisplatin, Adriamycin and cycloPhosphamide

- MPA

MedroxyProgesterone Acetate

- TAP or AP

Anthracycline (doxorubicin) plus Platinum (cisplatin) (with, or without, the Taxane, paclitaxel)

- TEC or TC

Taxane paclitaxel and Carboplatin (with, or without, the anthracycline, Epirubicin)

- TEP

Taxane (paclitaxel), Epirubicin and the Platinum, cisplatin

- TCw, TCm, TECm

TC or TEC administered on a weekly or monthly regimen

Contributor Information

Yutaka Ueda, Email: ZVF03563@nifty.ne.jp.

Takayuki Enomoto, Phone: +81-66879-3351, FAX: +81-66879-3359, Email: enomoto@gyne.med.osaka-u.ac.jp.

References

- 1.DiSaia PJ, Creasman WT. Clinical gynecologic oncology. 6. Mosby: St. Louis; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bristow RE, Zerbe MJ, Rosenshein NB, Grumbine FC, Montz FJ. Stage IVB endometrial carcinoma: the role of cytoreductive surgery and determinants of survival. Gynecol Oncol. 2000;78:85–91. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2000.5843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berek JS. Novak’s Gynecology. 13. Baltimore: William and Wilkins; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Randall ME, Filiaci VL, Muss H, Spirtos NM, Mannel RS, Fowler J, Thigpen JT, Benda JA. Gynecologic oncology group study randomized phase iii trial of whole-abdominal irradiation versus doxorubicin and cisplatin chemotherapy in advanced endometrial carcinoma: a gynecologic oncology group study. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:36–44. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.7617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Susumu N, Sagae S, Udagawa Y, Niwa K, Kuramoto H, Satoh S, Kudo R. Japanese gynecologic oncology group randomized phase iii trial of pelvic radiotherapy versus cisplatin-based combined chemotherapy in patients with intermediate—and high risk endometrial cancer: a Japanese gynecologic oncology group study. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;108:226–233. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aapro MS, van Wijk FH, Bolis G, Chevallier B, van der Burg ME, Poveda A, de Oliveira CF, Tumolo S, Scotto di Palumbo V, Piccart M, Franchi M, Zanaboni F, Lacave AJ, Fontanelli R, Favalli G, Zola P, Guastalla JP, Rosso R, Marth C, Nooij M, Presti M, Scarabelli C, Splinter TA, Ploch E, Beex LV, Ten Bokkel Huinink W, Forni M, Melpignano M, Blake P, Kerbrat P, Mendiola C, Cervantes A, Goupil A, Harper PG, Madronal C, Namer M, Scarfone G, Stoot JE, Teodorovic I, Coens C, Vergote I, Vermorken JB. European organisation for research, treatment of cancer gynaecological cancer group. Doxorubicin versus doxorubicin, cisplatin in endometrial carcinoma: definitive results of a randomised study (55872) by the EORTC gynaecological cancer group. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:441–448. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ball HG, Blessing JA, Lentz SS, Mutch DG. A phase II trial of paclitaxel in patients with advanced or recurrent adenocarcinoma of the endometrium: a gynecologic oncology group study. Gynecol Oncol. 1996;62:278–281. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1996.0227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fleming GF, Brunetto VL, Cella D, Look KY, Reid GC, Munkarah AR, Kline R, Burger RA, Goodman A, Burks RT. Phase III trial of doxorubicin plus cisplatin with or without paclitaxel plus filgrastim in advanced endometrial carcinoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2159–2166. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.07.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lissoni A, Gabriele A, Gorga G, Tumolo S, Landoni F, Mangioni C, Sessa C. Cisplatin-, epirubicin- and paclitaxel-containing chemotherapy in uterine adenocarcinoma. Ann Oncol. 1997;8:969–972. doi: 10.1023/A:1008221310453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sovak MA, Hensley ML, Dupont J, Ishill N, Alektiar KM, Abu-Rustum N, Barakat R, Chi DS, Sabbatini P, Spriggs DR, Aghajanian C. Paclitaxel and carboplatin in the adjuvant treatment of patients with high-risk stage III and IV endometrial cancer: a retrospective study. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;103:451–457. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Papadimitriou CA, Bafaloukos D, Bozas G, Kalofonos H, Kosmidis P, Aravantinos G, Fountzilas G, Dimopoulos MA. Hellenic co-operative oncology group. Paclitaxel, epirubicin, and carboplatin in advanced or recurrent endometrial carcinoma: a Hellenic co-operative oncology group (HeCOG) study. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;110:87–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoskins PJ, Swenerton KD, Pike JA, Wong F, Lim P, Acquino-Parsons C, Lee N. Paclitaxel and carboplatin, alone or with irradiation, in advanced or recurrent endometrial cancer: a phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:4048–4053. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.20.4048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.du Bois A, Neijt JP, Thigpen JT. First-line chemotherapy with carboplatin plus paclitaxel in advanced ovarian cancer–a new standard of care? Ann Oncol. 1999;10(Suppl 1):35–41. doi: 10.1023/A:1008355317514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Havrilesky LJ, Alvarez AA, Sayer RA, Lancaster JM, Soper JT, Berchuck A, Clarke-Pearson DL, Rodriguez GC, Carney ME. Weekly low-dose carboplatin and paclitaxel in the treatment of recurrent ovarian and peritoneal cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;88:51–57. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2002.6859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kikuchi A, Sakamoto H, Yamamoto T. Weekly carboplatin and paclitaxel is safe, active, and well tolerated in recurrent ovarian cancer cases of Japanese women previously treated with cisplatin-containing multidrug chemotherapy. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2005;15:45–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1048-891X.2005.15006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization . WHO handbook of reporting results of cancer treatment no. 48. Geneva: WHO Offset Publication; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pectasides D, Xiros N, Papaxoinis G, Pectasides E, Sykiotis C, Koumarianou A, Psyrri A, Gaglia A, Kassanos D, Gouveris P, Panayiotidis J, Fountzilas G, Economopoulos T. Carboplatin and paclitaxel in advanced or metastatic endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;109:250–254. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bartsch R, Wenzel C, Altorjai G, Pluschnig U, Rudas M, Mader RM, Gnant M, Zielinski CC, Steger GG. Capecitabine and trastuzumab in heavily pretreated metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3853–3858. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.9776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ueno Y, Enomoto T, Otsuki Y, Sugita N, Nakashima R, Yoshino K, Kuragaki C, Ueda Y, Aki T, Ikegami H, Yamazaki M, Ito K, Nagamatsu M, Nishizaki T, Asada M, Kameda T, Wakimoto A, Mizutani T, Yamada T, Murata Y. Prognostic significance of p53 mutation in sub optimally resected advanced ovarian carcinoma treated with the combination chemotherapy of paclitaxel and carboplatin. Cancer Lett. 2006;241:289–300. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Markman M, Markman J, Webster K, Zanotti K, Kulp B, Peterson G, Belinson J. Duration of response to second-line, platinum-based chemotherapy for ovarian cancer: implications for patient management and clinical trial design. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3120–3125. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.05.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harries M, Gore M. Part II: chemotherapy for epithelial ovarian cancer-treatment of recurrent disease. Lancet Oncol. 2002;3:537–545. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(02)00847-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blackledge G, Lawton F, Redman C, Kelly K. Response of patients in phase II studies of chemotherapy in ovarian cancer: implications for patient treatment and the design of phase II trials. Br J Cancer. 1989;59:650–653. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1989.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gore ME, Fryatt I, Wiltshaw E, Dawson T. Treatment of relapsed carcinoma of the ovary with cisplatin or carboplatin following initial treatment with these compounds. Gynecol Oncol. 1990;36:207–211. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(90)90174-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Markman M, Reichman B, Hakes T, Jones W, Lewis JL, Jr, Rubin S, Almadrones L, Hoskins W. Responses to second-line cisplatin-based intraperitoneal therapy in ovarian cancer: influence of a prior response to intravenous cisplatin. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9:1801–1805. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1991.9.10.1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]