Abstract

Objective

To test whether public reporting in the setting of postacute care in nursing homes results in changes in patient sorting.

Data Sources/Study Setting

All postacute care admissions from 2001 to 2003 in the nursing home Minimum Data Set.

Study Design

We test changes in patient sorting (or the changes in the illness severity of patients going to high- versus low-scoring facilities) when public reporting was initiated in nursing homes in 2002. We test for changes in sorting with respect to pain, delirium, and walking and then examine the potential roles of cream skimming and downcoding in changes in patient sorting. We use a difference-in-differences framework, taking advantage of the variation in the launch of public reporting in pilot and nonpilot states, to control for underlying trends in patient sorting.

Principal Findings

There was a significant change in patient sorting with respect to pain after public reporting was initiated, with high-risk patients being more likely to go to high-scoring facilities and low-risk patients more likely to go to low-scoring facilities. There was also an overall decrease in patient risk of pain with the launch of public reporting, which may be consistent with changes in documentation of pain levels (or downcoding). There was no significant change in sorting for delirium or walking.

Conclusions

Public reporting of nursing home quality improves matching of high-risk patients to high-quality facilities. However, efforts should be made to reduce the incentives for downcoding by nursing facilities.

Keywords: Public reporting, quality of care, nursing home quality

Publicly reporting quality information is a commonly adopted strategy that is typically thought to improve quality of care through two pathways (Berwick, James, and Coye 2003). First, having quality information publicly available makes it possible for health care consumers (or their agents and advocates) to shop on quality, thus increasing the number of patients choosing high-quality providers. Second, in response to the increased demand for high-quality care, public reporting may induce health care providers to invest in and improve the quality of care they deliver. Prior work has documented quality improvement from public reporting through both of these pathways (Marshall et al. 2000; Fung et al. 2008;).

While these consumer- and provider-driven pathways may represent the dominant responses to public reporting, public reporting may change quality in additional ways. One possibility is that public reporting affects the sorting of patients to providers. Whereas typical demand-side changes under public reporting imply that the number of patients choosing high-scoring providers increases, sorting may change the type of patients choosing high-scoring providers (e.g., changing the case mix of patients going to high- versus low-scoring facilities). Changes in patient sorting may be patient driven and result in improved matching of patients to providers (i.e., if high-risk patients are more likely to seek out high-scoring providers). They may also be provider driven, either resulting from cream skimming (i.e., if low-scoring providers are more likely to seek out low-risk patients) or downcoding (i.e., if low-scoring providers change their documentation to make their patients [and their quality] appear better).

Our objective in this paper is to test whether public reporting in the setting of postacute care in skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) results in changes in patient sorting, and to test whether changes in patient sorting are driven by patient or provider behavior.

BACKGROUND AND PRIOR LITERATURE

Public reporting may shift the type of patients seen at high- and low-scoring providers for several reasons. First, patient–provider matching may improve because sicker patients may disproportionately use publicly reported information to seek out high-scoring providers if they stand to gain more by finding a high-quality provider (or lose more if they are cared for by a low-quality provider). Limited prior work has examined whether public reporting results in better matching of sick patients to high-scoring providers. One study examined changes in patient sorting after the publication of cardiac bypass surgery mortality rates in the early 1990s and found evidence of improved matching (Dranove et al. 2003).

Second, certain types of providers—such as low-quality providers—may benefit from improving their report card scores by either seeking out lower-risk patients (cream skimming) or by changing their documentation of patient characteristics to make patients appear healthier (downcoding). Cream skimming is only possible if patient outcomes that are publicly reported are not perfectly risk adjusted or if providers have superior information about patient risk than the risk adjustment used in public reporting. Cream skimming may result in fewer high-risk patients being treated overall by providers subject to public reporting (particularly if there are provider or treatment substitutes available), and downcoding may result in the appearance of lower risk on average (without changes in the true underlying risk levels). However, cream skimming and downcoding may cause the appearance of patient matching when improved patient matching does not exist or exaggerate estimates of improvements in true patient matching. This might happen if the likelihood of cream skimming or downcoding differs by provider type (e.g., low-quality providers may be more likely to engage in cream skimming or downcoding to improve their quality scores).

Prior work has documented cases of both cream skimming (Omoigui et al. 1996; Schneider and Epstein 1996; Dranove et al. 2003;) and downcoding (Green and Wintfeld 1995) in the setting of public reporting. One prior study examined whether public reporting in nursing homes caused cream skimming of low-risk patients by examining trends in six clinical characteristics among newly admitted nursing homes residents. They find that one characteristic declined after the initiation of public reporting (the percentage of newly admitted residents in pain) and that this decline was larger among facilities reported to have poor pain control (Mukamel et al. 2009). While suggestive of cream skimming, this descriptive study did not attempt to differentiate patient matching, provider cream skimming, and downcoding.

SETTING

We focus our analyses on postacute care (or short-stay) residents of nursing homes. Postacute care provides a transition between hospitalization and home (or another long-term care setting) for over 5.1 million Medicare beneficiaries annually (MedPAC 2008), providing health care services, including rehabilitation, skilled nursing, and other ancillary services in a variety of health care settings (MedPAC 2009). Over 40 percent of Medicare beneficiaries use postacute care annually and the largest proportion of postacute care occurs in nursing homes (or SNFs), with over 2.5 million SNF stays in 2007 for which Medicare paid over U.S.$21 billion. Approximately 11 percent of nursing home beds are filled by Medicare postacute care patients at any given time; these services provide an important revenue stream for nursing homes.

Poor quality of care has been pervasive in nursing homes for decades (Institute of Medicine 1986). In an attempt to address these quality deficits, the Department of Health and Human Services announced the formation of the Nursing Home Quality Initiative in 2001, with a major goal of improving the information available to consumers on the quality of care at nursing homes. As part of this effort, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) released Nursing Home Compare, a guide detailing quality of care at over 17,000 Medicare- and/or Medicaid-certified nursing homes (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid 2008). Nursing Home Compare was first launched as a pilot program in six states in April 2002 (Colorado, Florida, Maryland, Ohio, Rhode Island, and Washington). Seven months later, in November 2002, Nursing Home Compare was launched nationally. At that time, Nursing Home Compare included four measures of postacute care quality: the proportion of postacute care residents with moderate to severe pain, delirium (with and without adjustment for facility admissions profile), and improvement in walking. The facility-adjusted delirium measure was dropped soon thereafter, leaving three postacute care measures.

Several recent studies have examined whether quality improved under Nursing Home Compare. These studies have found that report card scores improved on some clinical measures but not others (Mukamel et al. 2008b; Werner et al. 2009;). For measures where quality scores improved, such as the proportion of nursing home residents with pain, the size of the improvement was modest (Werner et al. 2009).

METHODS

We extend prior work on Nursing Home Compare by testing empirically for a change in patient sorting—or the illness severity of patients going to high- versus low-scoring facilities after the initiation of public reporting—and then examining the role of cream skimming and downcoding in changes in patient sorting. We use a difference-in-differences framework, taking advantage of the variation in release of Nursing Home Compare in pilot and nonpilot states, to control for underlying trends in patient sorting. The contemporaneous control of pilot states provides a stronger empirical test of the association between Nursing Home Compare and observed changes in patient sorting and illness severity than just relying on within-state pre–post changes in patient sorting.

Study Sample

We focus on the postacute care nursing home population for several important reasons. First, the postacute population has a high turnover rate and less cognitive impairment compared with the chronic care nursing home population. This makes it feasible empirically to find changes in patient sorting in response to public reporting over a short timeframe, if they exist. Second, postacute care residents can be linked with important variables used in case mix adjustment from the qualifying Medicare-covered hospitalization, enhancing our ability to control carefully for changes in case mix when testing for changes in quality. Finally, with the high spending on postacute care, improving the quality of postacute care has become a high priority for Medicare.

We include all nursing homes that were persistently included in public reporting for postacute care measures over this period (SNFs with fewer than 20 eligible patients over a 6-month period are excluded from Nursing Home Compare [Morris et al. 2003]). While approximately one-half of SNFs are excluded from our analyses due to their small size, only 6 percent of SNF discharges are excluded. Among SNFs exposed to public reporting, we included all Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries age 65 years or older.

Data

Our primary data source is the nursing home Minimum Data Set (MDS). The MDS contains detailed clinical data collected at regular intervals for every resident in a Medicare- and/or Medicaid-certified nursing home. These data are collected and used by nursing homes to assess needs and develop a plan of care unique to each resident and by the CMS to calculate Medicare prospective reimbursement rates. Because of the reliability of these data (Gambassi et al. 1998; Mor et al. 2003;) and the detailed clinical information contained therein, they are the data source for the report card measures included in Nursing Home Compare. We also used two secondary sources of data. We obtained facility characteristics from the Online Survey, Certification and Reporting dataset. We used the 100 percent MedPAR data (with all Part A claims) to calculate health care utilization covariates used in risk adjustment.

Dependent Variables: Patient Risk

We define our dependent variables of patient risk in three ways: patients with moderate or severe pain on admission; delirium on admission; and difficulty walking on admission. These are baseline assessments that are not publicly reported. However, they correspond to the three postacute clinical areas for which quality is measured from 14-day assessments and publicly reported.

Main Independent Variable: Facility Quality Report Card Scores

Our main independent variables are the three facility quality report card scores used by Nursing Home Compare: percent of short-stay patients who did not have moderate or severe pain; percent of short-stay patients without delirium; and percent of short-stay patients whose walking remained independent or improved. (All report card scores are scaled so that higher levels indicate higher quality.) We calculate these report card scores directly from MDS (rather than using the scores that were publicly reported), enabling us to consistently measure facility report card scores both before and after public reporting of these scores was initiated.

We calculated report card scores for each facility following the method used to calculate the publicly reported postacute care report card scores on Nursing Home Compare (Morris et al. 2003): Each measure is based on patient assessments 14 days after admission; is calculated based on assessments over a 6-month period; includes only those residents who stay in the facility long enough to have a 14-day assessment; is calculated only at facilities with at least 20 cases during the target time period; and is based on data collected 3–9 months before the score's calculation. To ensure accurate replication of the report card scores, we benchmarked our calculated report card scores against the report cards available from CMS. Our calculated scores did not significantly differ from those reported by CMS, differing by between 0 and 0.1 percentage points, indicating an excellent match between the results of our calculations and the publicly reported scores. Note that we measure patient risk at admission and that facility quality is based on patient outcomes on the 14th day of their postacute care stay.

Covariates

We include patient- and facility-level characteristics as covariates in all analyses. Patient characteristics include sociodemographic characteristics (age, sex, and race), comorbidities (including cognitive performance, functional status, and indicators of medical diagnoses), resource utilization group, and prior health care utilization (including prior number of SNF stays, hospital stays, and total Medicare charges). Facility characteristics include profit status, size, occupancy, hospital based, and payer mix. We also include postacute care market fixed effects (defined by the Dartmouth Atlas Hospital Service Areas) and time quarter fixed effects.

Empirical Specifications

All analyses include SNF admissions between the years 2001 and 2003, spanning the launch of the first published reports from Nursing Home Compare in April and November 2002, for pilot and nonpilot states, respectively.

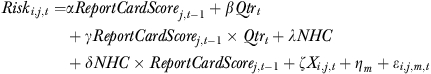

Our first goal is to test for changes in patient sorting related to the launch of public reporting using two empirical approaches. First, we describe quarterly estimates of patient sorting using an interrupted time-series design and test whether we observe changes in patient sorting in the quarters when Nursing Home Compare was launched. Using a linear probability model, we estimate the following:

| (1) |

where patient i's risk (in facility j, market m, quarter t) is estimated as a function of the report card score of that patient's chosen facility in the prior quarter, a vector of quarterly time dummies, and the interaction between the two. We also include a vector of time-varying patient and facility characteristics and market fixed effects. We lag the report card score by one-quarter to allow consumers to respond to the report card score from the prior quarter. The coefficient on the report card score (α) represents patient sorting in the baseline and omitted time period—the first quarter of 2001—and reflects the correlation between a facility's report card score in a given clinical area and the status of newly admitted patients in the same clinical area. The coefficients on the vector of interactions (γ) represent quarterly changes in patient sorting after the baseline period. Before public reporting, we expect this correlation to be low and unchanged from quarter to quarter, as consumers were not aware of scores and facilities had little incentive to engage in cream skimming or downcoding. After public reporting, we expect this correlation to increase. We stratify these regressions by location in a pilot versus nonpilot state, as Nursing Home Compare was initiated 7 months earlier in the pilot states, hypothesizing that the γ will be higher in post-Nursing Home Compare quarters than in the respective preceding quarters, with the change in the trend occurring when Nursing Home Compare was implemented (second quarter of 2002 for pilot states and fourth quarter of 2002 for nonpilot states). We estimate this specification separately for the clinical areas of pain, delirium, and walking.

Second, to more directly test whether changes in patient sorting are attributable to Nursing Home Compare, we use a difference-in-differences specification that mirrors that used in equation (1) but pools pilot and nonpilot states and adds an interaction between a post-Nursing Home Compare indicator variable and facility report card scores:

|

(2) |

The Nursing Home Compare indicator variable (NHC) equals 1 after public reporting was launched and zero otherwise; it thus varies between pilot and nonpilot states because of the different timing of the launch of Nursing Home Compare. The coefficient on the second interaction term (δ) represents a difference-in-differences estimate of change in patient sorting between pilot and nonpilot states (controlling for secular trends). Identification using this specification comes from the 7-month gap in launching public reporting nationwide after it was initiated in the pilot states. As above, we estimate changes in patient sorting in the clinical areas of pain, delirium, and walking separately.

Our second goal is to explore whether identified changes in patient sorting could be due to provider behavior (cream skimming or downcoding). First, we look for changes in admission severity, or the overall incidence of pain, delirium, and difficulty walking on admission to postacute care in SNFs. We test for these incidence changes using the same difference-in-differences estimation strategy described above, estimating differences in patient risk between pilot and nonpilot states.

Second, we test whether any observed declines in admission severity are more likely due to cream skimming or downcoding. To do this we use data from the prereporting period and regress a patient's admission risk on 33 predictors of admission risk from MDS and MedPAR (including demographics, prior SNF and hospital utilization, RUG groups, clinical characteristics, and comorbidities) and then use the coefficients from these regressions to predict each patient's admission risk in the postreporting period. If patients entering SNFs after Nursing Home Compare was launched were lower risk for poor outcomes (and risk levels were correlated with other observable patient characteristics), we expect that predicted admission risk would also decline after Nursing Home Compare was launched. This would suggest that observed declines in risk were due to true declines in patient severity, which might be due to cream skimming. On the other hand, if actual patient risk did not change but SNFs engaged in downcoding after Nursing Home Compare was launched, we expect that predicted risk would remain stable while observed risk declines.

Third, we test whether any observed declines in admission risk might be driving the main result of changes in patient sorting. To do this, we redefine our dependent variable with a simulated variable that takes on the values of observed admission risk in the prereporting period and predicted risk in the postreporting period (starting in 2002q2 in pilot states and 2002q4 in nonpilot states). We then use this simulated dependent variable to test whether changes in patient sorting remain using the same difference-in-difference model defined in equation (2).

RESULTS

A total of 8,139 SNFs from Nursing Home Compare were included in the study, covering 4,437,746 postacute care admissions. Characteristics of these SNFs and SNF stays are summarized in Table 1, stratified by location in pilot versus nonpilot states.

Table 1.

Characteristics of SNFs and SNF Admissions in Study Sample, Stratified by Participation in the Nursing Home Compare Pilot Program

| Pilot States | Nonpilot States | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) of SNFs | 1,485 | (18.2) | 6,654 | (81.8) |

| Number (%) of SNF admissions | 885,658 | (20.0) | 3,552,088 | (80.0) |

| Number (%) of SNF admissions with | ||||

| Moderate or severe pain | 267,680 | (30.2) | 995,251 | (28.0) |

| Delirium | 67,168 | (7.6) | 241,448 | (6.8) |

| Difficulty walking | 858,511 | (96.9) | 3,412,309 | (96.1) |

| Facility report card scores, mean (SD) | ||||

| % Residents without pain | 73.6 | (13.8) | 75.9 | (14.4) |

| % Residents without delirium | 95.5 | (5.9) | 95.9 | (5.5) |

| % Residents who are independent in walking or whose walking improved | 31 | (14.4) | 28.1 | (14.5) |

| Facility characteristics | ||||

| Ownership, n (%) | ||||

| For profit | 1,116 | (75.2) | 4,583 | (68.9) |

| Not for profit | 332 | (22.4) | 1,777 | (26.7) |

| Government | 37 | (2.5) | 294 | (4.4) |

| Total number of beds, mean (SD) | 133.9 | (75.2) | 134.8 | (80.1) |

| Occupancy rate, mean (SD) | 81.9 | (19.4) | 84.1 | (17.9) |

| Hospital based, n (%) | 115 | (7.7) | 715 | (10.7) |

| Payer mix, mean (SD) | ||||

| % Medicare | 17.7 | (20.0) | 18.0 | (22.3) |

| % Medicaid | 56.1 | (23.9) | 29.2 | (25.8) |

| % Private pay | 26.2 | (17.5) | 22.8 | (17.8) |

SNF, skilled nursing facility.

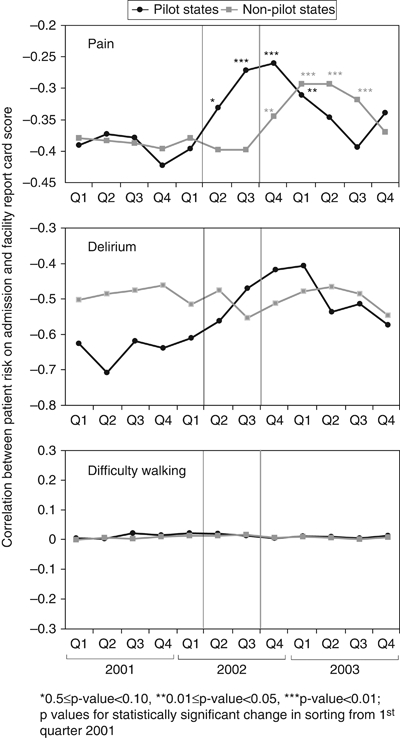

Quarterly estimates of patient sorting based on equation 1 (i.e., the correlation between patient risk and report card scores) are displayed in Figure 1. For pain, low-scoring facilities are more likely to serve high-risk patients at baseline (as evidenced by the negative correlation between patient risk and report card scores) and this sorting did not significantly change quarter to quarter before the initiation of public reporting. However, the correlation between patient risk and report card scores significantly increased in the quarter after these scores became publicly available via the launch of Nursing Home Compare in both pilot and nonpilot states, suggesting that patients with admission pain were more likely to choose higher-scoring facilities when quality information became publicly available. Evidence of improved matching remained for four quarters after public reporting was initiated, but then declined to prereporting levels. For delirium, although there was an increase in the correlation between patient risk and report card scores at the launch of Nursing Home Compare in the pilot states, the change was not statistically significant and was not seen in nonpilot states. There was no change in patient sorting with respect to difficulty walking.

Figure 1.

Correlation between Patient Risk on Admission and Facility Report Card Score (Or Patient Sorting) before and after Report Card Scores Were Publicly Reported

Notes. Results are stratified by location in a pilot versus nonpilot state because public reporting was launched at different times in pilot and nonpilot states. The vertical lines show the timing of the launch of public reporting in pilot states (in black) and nonpilot states (in gray). Results from multivariate regression described in Equation 1.

Difference-in-differences estimates of changes in patient sorting in response to Nursing Home Compare (from equation 2) are displayed in Table 2. Changes in matching from Nursing Home Compare for pain is 0.095, suggesting that after Nursing Home Compare was launched a 10-point higher facility report card score was associated with an approximately 1-percentage point higher admission pain level in the following quarter. Changes in matching for delirium and walking were not statistically significant.

Table 2.

Difference-in-Differences Estimates (from Equation 2) of Changes in Matching between High-Quality SNFs and High-Severity Patients after NHC Was Launched

| Pain on Admission | Delirium on Admission | Difficulty Walking on Admission | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Report card score × post-NHC† | 0.095*** | 0.029 | −0.005 |

| (.018) | (.057) | (.008) | |

| Post-NHC‡ | −0.091*** | −0.029 | 0.001 |

| (.014) | (.055) | (.002) | |

| Pilot state | −0.06*** | 0.01 | 0.006 |

| (.013) | (.017) | (.011) | |

| Quarterly estimates of report card scores | x | x | x |

| Quarterly fixed effects | x | x | x |

| Market fixed effects | x | x | x |

| Constant | −0.005*** | 0.000*** | 0.001*** |

| (.000) | (.000) | (.000) | |

| Number of observations | 4,437,746 | 4,437,746 | 4,437,746 |

| R2 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.17 |

Notes. Key coefficients are highlighted in bold. All regressions include patient and facility characteristics (profit status, number of total beds, occupancy, hospital based, and payer mix).

Robust standard errors in parentheses.

Report card score is defined as the percent of residents without pain, without delirium, who are independent in walking or whose walking improved for regressions of changes in admission-level pain, delirium, and difficulty walking, respectively. These report card scores are included in Nursing Home Compare. We include a one-quarter lag of the report card scores to allow consumers time to respond to the scores that were reported in the prior quarter.

Nursing home compare was launched in April 2002 (or 2002q2) in pilot states and November 2002 (or 2002q4) in nonpilot states.

p-value <.01.

NHC, Nursing Home Compare; SNF, skilled nursing facility.

There was also a decline in the incidence of moderate to severe pain across all SNFs at the time of admission to postacute care after Nursing Home Compare was launched, with the incidence of admission pain declining by 2.01 percentage points on a base of approximately 30 percent (standard error 0.19; p-value <.001). The changes in admission incidence of delirium and difficulty walking were small and statistically nonsignificant.

While the observed incidence of pain on admission declined by 2 percentage points after Nursing Home Compare was launched, the predicted incidence of admission pain did not significantly change. The change in the predicted value of admission pain after Nursing Home Compare was launched was close to zero (change 0.07 percentage points, standard error 0.04; p-value .09). However, when substituting this predicted value for the dependent variable in the postpublic reporting period, the estimate of patient sorting did not change substantially. With the simulated dependent variable, public reporting was associated with a statistically significant change of patient sorting of 0.093 (standard error 0.013; p-value <.001).

DISCUSSION

We find a significant change in patient sorting with respect to pain after public reporting was initiated, with high-risk patients being more likely to go to high-scoring facilities and low-risk patients more likely to go to low-scoring facilities. We also find that the incidence of admission pain levels decreases after the launch of public reporting in a way that is not predicted by other patient characteristics, suggesting that facilities were downcoding high-risk patients. Nonetheless, even after accounting for potential down coding, significant evidence of patient sorting remained.

Although we find evidence of changes in patient sorting and changes in admission risk profiles with respect to pain, we find little evidence of either patient sorting or changes in admission risk with respect to delirium or walking. There are plausible explanations for these discrepant findings. First, admission delirium and difficulty walking had very low and high prevalence (at 7 and 96 percent, respectively), making it less likely we will find evidence of changes in patient sorting, if it exists. Second, to the extent that improved matching is due to patient behavior, the report card measure of pain control may be more salient and thus patients (or their agents) may be more likely to respond to it. Because of the low levels of within-facility correlation between report card measures, improved matching on one measure will not necessarily spill over to improved matching on another uncorrelated measure.

We also find that changes in patient sorting on pain waned over four quarters in both pilot and nonpilot states. While one explanation for this waning effect might be that the effect of public reporting itself wanes over time, as fewer resources are devoted to promoting it, a more compelling explanation is related to the inadequate risk adjustment of the quality measures used in Nursing Home Compare (Arling et al. 2007; Mukamel et al. 2008a;). If quality measures are poorly risk adjusted, as high-scoring facilities attract high-risk patients their report card scores are bound to decline. Indeed, the four quarters of improved sorting that we document may be related to the delay built into the calculation of the report card scores—report card scores are calculated three quarters after the data are collected; we include a one-quarter lag of the report card scores to allow consumers a chance to respond to the information. Thus, the changes in patient illness severity that occur at the time of Nursing Home Compare would take four quarters to appear in the report card score.

We make several important contributions to the existing literature. To our knowledge, we are the first to directly examine changes in patient sorting in response to Nursing Home Compare. While it is usually assumed that public reporting will improve quality of care by increasing the market share of high-quality providers and/or giving providers incentive to improve the quality of care they deliver, changes in patient sorting suggests an alternative mechanism to improve quality of care, implying that there are changes in the type of patients a provider sees, rather than or in addition to the number of patients a provider sees. Improved matching suggests that the quality effect of public reporting may be largest among the sickest patients.

While prior work has described a decline in the incidence of admission pain after Nursing Home Compare was launched (Mukamel et al. 2009), we affirm these findings using a robust methodological approach that controls for underlying secular trends. Even when controlling for underlying trends in states where Nursing Home Compare was not simultaneously released, we find clinically meaningful declines in levels of admission pain. However, our analyses suggest that these declines are most consistent with downcoding rather than cream skimming. While it remains possible that nursing homes engage in cream skimming, particularly in ways that are unobservable to us in the data, we find that observable patient characteristics are predictive of higher, and stable, levels of admission pain after Nursing Home Compare was launched. Researchers have found evidence of downcoding in the presence of public reporting (Green and Wintfeld 1995). In addition, prior evidence suggests the reliability of the pain measure may be low and varies with patient characteristics (Wu et al. 2005a, b;). Despite the evidence in support of downcoding in this setting, downcoding does not substantially alter our estimates of sorting. Even after controlling for changes in coding we find significant changes in patient sorting in association with public reporting.

A few study limitations should be considered. First, the relationship we estimate between a facility's report card score and admission severity may be endogenous, particularly in the presence of inadequate risk adjustment where the severity of patients admitted influences that facility's report card score. Although our lagged report card scores account in part for this potential source of endogeneity, it remains a possible source of bias. Second, we limit our analyses to the postacute care patients in nursing homes, which limit the generalizability of our results. However, these results provide important information about the potential for public reporting to induce patient matching and downcoding in any health care sector. Third, our difference-in-differences model depends on the assumption that secular trends in pilot and nonpilot states are the same, and potential violations of this assumption make causal attribution of changes in sorting and case mix to Nursing Home Compare impossible.

Despite these limitations, our findings have important implications. Public reporting may have the largest impact on improving quality for the sickest patients. Thus, looking for changes in quality on average, rather than among subsets of patients, may lead to an underestimate of the effect of public reporting on quality of care. Although improved matching of patients to providers under public reporting is good news, it is accompanied by the possibility that public reporting may also induce downcoding by providers. Changes in coding may be a justified response to data inaccuracies that must be fixed to more accurately measure quality. However, these changes obfuscate true changes in quality in response to quality improvement incentives.

Acknowledgments

Joint Acknowledgment/Disclosure Statement: This research was funded by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R01 HS016478-01). Rachel M. Werner is supported in part by a VA HSR&D Career Development Award.

Disclosures: None.

Disclaimers: The content of this article does not reflect the views of the VA or of the U.S. Government.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article:

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell is not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

REFERENCES

- Arling G, Lewis T, Kane RL, Mueller C, Flood S. Improving Quality Assessment through Multilevel Modeling: The Case of Nursing Home Compare. Health Service Research. 2007;42(3, Part 1):1177–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00647.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berwick DM, James B, Coye MJ. Connections between Quality Measurement and Improvement. Medical Care. 2003;41(1) suppl:I-30–8. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200301001-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid. 2008. “Nursing Home Compare” [accessed on September 19, 2008]. Available at http://www.medicare.gov/Nhcompare/Home.asp.

- Dranove D, Kessler D, McClellan M, Satterthwaite M. Is More Information Better? The Effects of “Report Cards” on Health Care Providers. Journal of Political Economy. 2003;111(3):555–88. [Google Scholar]

- Fung CH, Lim Y-W, Mattke S, Damberg C, Shekelle PG. Systematic Review: The Evidence That Publishing Patient Care Performance Data Improves Quality of Care. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2008;148(2):111–23. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-2-200801150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gambassi G, Landi F, Peng L, Brostrup-Jensen C, Calore K, Hiris J, Lipsitz L, Mor V, Bernabei R. Validity of Diagnostic and Drug Data in Standardized Nursing Home Resident Assessments: Potential for Geriatric Pharmacoepidemiology. SAGE Study Group. Systematic Assessment of Geriatric Drug Use via Epidemiology. Medical Care. 1998;36(2):167–79. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199802000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green J, Wintfeld N. Report Cards on Cardiac Surgeons. Assessing New York State's Approach. New England Journal of Medicine. 1995;332(18):1229–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505043321812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Improving the Quality of Care in Nursing Homes. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall MN, Shekelle PG, Leatherman S, Brook RH. The Public Release of Performance Data: What do we Expect to Gain? A Review of the Evidence. Journal of American Medical Association. 2000;283:1866–74. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.14.1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MedPAC. A Data Book: Healthcare Spending and the Medicare Program (June 2008) Washington, DC: Medicare Payment Advisory Commission; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- MedPAC. Report to Congress: Medicare Payment Policy (March 2009) Washington, DC: Medicare Payment Advisory Commission; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mor V, Angelelli J, Jones R, Roy J, Moore T, Morris J. Inter-Rater Reliability of Nursing Home Quality Indicators in the U.S. BMC Health Services Research. 2003;3:20. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-3-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JN, Moore T, Jones R, Mor V, Angelelli J, Berg K, Hale C, Morriss S, Murphy KM, Rennison M. Validation of Long-Term and Post-Acute Care Quality Indicators. Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Mukamel DB, Glance LG, Li Y, Weimer DL, Spector WD, Zinn JS, Mosqueda L. Does Risk Adjustment of the CMS Quality Measures for Nursing Homes Matter? Medical Care. 2008a;46(5):532–41. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31816099c5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukamel DB, Weimer DL, Spector WD, Ladd H, Zinn JS. Publication of Quality Report Cards and Trends in Reported Quality Measures in Nursing Homes. Health Service Research. 2008b;43(4):1244–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00829.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukamel DB, Ladd H, Weimer DL, Spector WD, Zinn JS. Is there Evidence of Cream Skimming among Nursing Homes Following the Publication of the Nursing Home Compare Report Card? Gerontologist. 2009;49:793–802. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omoigui NA, Miller DP, Brown KJ, Annan K, Cosgrove D, Lytle B, Loop F, Topol EJ. Outmigration for Coronary Bypass Surgery in an Era of Public Dissemination of Clinical Outcomes. Circulation. 1996;93:27–33. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider EC, Epstein AM. Influence of Cardiac-Surgery Performance Reports on Referral Practices and Access to Care: A Survey of Cardiovascular Specialists. New England Journal of Medicine. 1996;335:251–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199607253350406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner RM, Konetzka RT, Stuart EA, Norton EC, Polsky D, Park J. The Impact of Public Reporting on Quality of Post-Acute Care. Health Service Research. 2009;44(4):1169–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.00967.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu N, Miller SC, Lapane K, Roy J, Mor V. Impact of Cognitive Function on Assessments of Nursing Home Residents' Pain. Medical Care. 2005a;43(9):934–9. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000173595.66356.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu N. The Quality of the Quality Indicator of Pain Derived from the Minimum Data Set. Health Service Research. 2005b;40(4):1197–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00400.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.