SUMMARY

Activation Induced cytidine Deaminase (AID) initiates Immunoglobulin (Ig) heavy chain (IgH) class switch recombination (CSR) and Ig variable region somatic hypermutation (SHM) in B lymphocytes by deaminating cytidines on template and non-template strands of transcribed DNA substrates. However, the mechanism of AID access to the template DNA strand, particularly when hybridized to a nascent RNA transcript, has been an enigma. We now implicate the RNA exosome, a cellular RNA processing/degradation complex, in targeting AID to both DNA strands. In B-lineage cells activated for CSR, the RNA exosome associates with AID, accumulates on IgH switch regions in an AID-dependent fashion, and is required for optimal CSR. Moreover, both the cellular RNA exosome complex and a recombinant RNA exosome core complex impart robust AID- and transcription-dependent DNA deamination of both strands of transcribed SHM substrates in vitro. Our findings reveal a role for non-coding RNA surveillance machinery in generating antibody diversity.

INTRODUCTION

Antigen activated B lymphocytes undergo two distinct immunoglobulin (Ig) gene diversification processes, namely somatic hypermutation (SHM) and Ig heavy chain (IgH) class switch recombination (CSR). SHM diversifies IgH and Ig light chain (IgL) variable region exons to allow generation of B cells with the potential to secrete higher affinity antibodies (reviewed by Odegard and Schatz, 2006; Di Noia and Neuberger, 2007; Maul and Gearheart, 2010). IgH class switch recombination (CSR) allows B cells to express different classes of antibodies with different IgH constant regions (CHs) and, as a result, different antibody effector functions (reviewed by Chaudhuri et al., 2007; Honjo et al., 2002). CSR involves joining DNA double strand breaks (DSBs) in the large repetitive switch (S) region (Sµ) that lies upstream of the Cµ constant regions exons to DSBs within a downstream S region (e.g. Sγ1), which replaces Cµ exons with a set of downstream CH exons to complete CSR (e.g. switching from IgM to IgG1). Activation Induced cytidine Deaminase (AID) initiates both SHM and CSR (Muramatsu et al., 2000; Revy et al., 2000) by deaminating cytidines on, respectively, transcribed IgH or IgL variable region exons or transcribed IgH S regions (Petersen-Mahrt et al., 2002). The deaminated cytidines become targets of co-opted DNA repair pathways that lead to mutations associated with variable region exon SHM or to S region DSBs that initiate CSR (reviewed by Di Noia and Neuberger, 2007; Neuberger et al., 2003). To initiate both SHM and CSR, AID equally deaminates both template and non-template strands of transcribed target DNA sequences (Milstein et al., 1998; Shen et al., 2006; Xue et al., 2006).

AID is a single-stranded (ss) DNA specific cytidine deaminase that lacks activity on double-stranded (ds) DNA (Chaudhuri et al., 2003; Dickerson et al., 2003; Ramiro et al., 2003; Sohail et al., 2003). Correspondingly, SHM and CSR require transcription through duplex substrate V(D)J exons or S regions to target AID activity, consistent with transcription generating a ssDNA AID substrate (reviewed by Chaudhuri et al., 2007; Yang and Schatz, 2007; Di Noia and Neuberger, 2007; Maul and Gearheart, 2010). Transcription through mammalian S regions generates R-loops, in which the template strand is hybridized to the nascent transcript and the non-template strand is looped out as ssDNA (Daniels and Lieber, 1995; Shinkura et al., 2003; Tian and Alt, 2000; Yu et al., 2003a). In biochemical studies, transcription-generated R-loops within duplex substrates allow AID deamination, but mainly on the looped-out non-template strand (Chaudhuri et al., 2003). AID that is phosphorylated on serine 38 by protein kinase A can access in vitro transcribed dsDNA SHM substrates (e.g. V(D)J exons) that lack R-loop forming ability; again, however, mainly on the non-template strand (Basu et al., 2005; Basu et al., 2008; Chaudhuri et al., 2004; Zarrin et al., 2004; Vuong et al., 2009). Ectopically expressed AID mutates transcribed substrates in bacteria and yeast, but once again predominantly on the non-template strand (Gomez-Gonzalez and Aguilera, 2007; Ramiro et al., 2003). Thus, the mechanism by which AID accesses the template DNA strand of substrates has been a major question (e.g. Chaudhuri et al., 2007; Chelico et al., 2009; Di Noia and Neuberger, 2007; Liu and Schatz, 2009; Longerich et al., 2006; Maul and Gearhart, 2010; Pavri et al., 2010; Peled et al., 2008).

Biochemical studies suggested that AID may gain access to both DNA strands of certain types of transcribed plasmids via formation of RNA polymerase-generated super-coils (Besmer et al., 2006; Shen et al., 2005; Shen and Storb, 2004). However, such a mechanism does not readily explain how AID accesses the template strand of a transcribed substrate if it is blocked by a nascent RNA transcript (Maul and Gearheart, 2010). Indeed, AID has no known activity on RNA/DNA hybrids, which form over wide regions of mammalian S regions in the form of R-loops (Huang et al., 2007; Huang et al., 2006; Roy, Yu, and LIeber, 2008; Yu et al., 2003a) and which may also form in the context of transcription bubbles (Gomez-Gonzalez and Aguilera, 2007; Li and Manley, 2005). RNase H has been proposed as a candidate for exposing regions of R-looped S region template strands to AID based on biochemical ability to degrade RNA in the context of R-loops (Lieber, 2010; Yu and Lieber, 2003b); however, to date there has been no direct evidence that implicated either RNase H or other cellular RNA degradation factors in CSR.

The RNA exosome is an evolutionarily conserved RNA processing/degradation complex (reviewed by Houseley et al., 2006; Lykke-Andersen et al., 2009; Schmid and Jensen, 2008; Shen and Kiledjian, 2006). The nine sub-unit core of the eukaryotic RNA exosome, which includes the CsL4, Rrp4, Rrp40, Rrp41, Rrp46, Mtr3, Rrp42, Rrp43 and Rrp45 subunits, has RNA-binding activity, but lacks ribonuclease activity (Anderson et al., 2006; Greimann and Lima, 2008; Oddone et al., 2007; Figure S1). RNA exosome ribonuclease activity is provided by non-core subunits including Rrp6 and Rrp44 that have RNA 3'-5' exonuclease or endonuclease activity (Greimann and Lima, 2008; Houseley et al., 2006; Lebreton et al., 2008; Schaeffer et al., 2009; Figure S1). The mammalian RNA exosome complex interacts with co-factors, such as the TRAMP complex, that target it to particular substrates based on sequence or structural features (reviewed by Houseley et al., 2006; Houseley and Tollervey, 2008; LaCava et al., 2005). In Drosophila, the RNA exosome complex interacts with elongating RNA polymerase II (Pol II) complexes via the Spt5/6 transcription elongation co-factors (Andrulis et al., 2002); and in yeast it binds to and removes nascent RNP complexes from template DNA (El Hage et al., 2010; Houseley et al., 2006; Houseley and Tollervey, 2008). We now describe studies that implicate the RNA exosome as a long speculated co-factor that targets AID deamination activity to both template and non-template strands of transcribed dsDNA substrates.

RESULTS

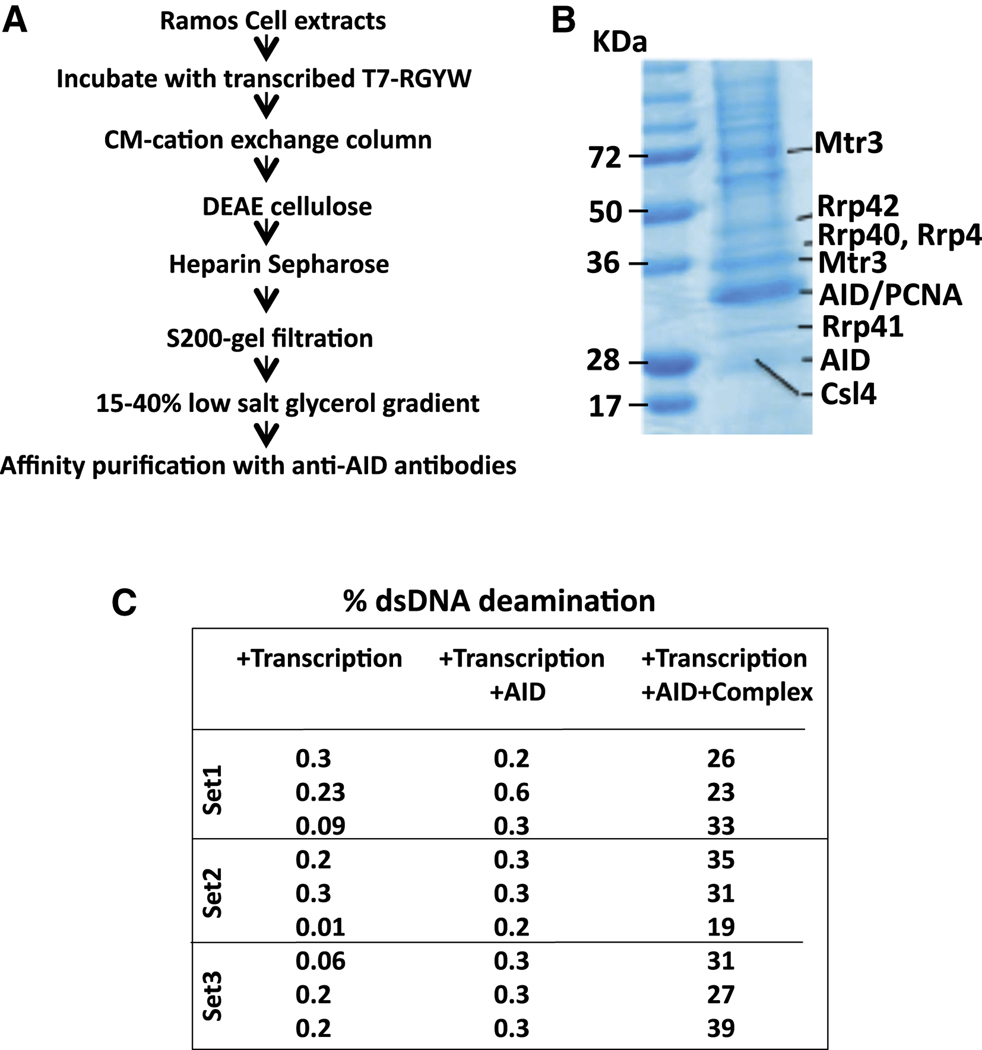

AID associates with the RNA exosome complex

To elucidate factors that might promote AID access to the template strand of transcribed substrates in the context of RNA/DNA hybrid structures, we in vitro transcribed an RGYW-rich dsDNA SHM substrate with T7 RNA polymerase in presence of Ramos human B cell lymphoma line extracts. Transcribed DNA- protein complexes were purified via chromatographic steps that would enrich for DNA binding (CM-sepharose, DEAE cellulose) and macromolecular complex formation (gel-filtration chromatography), followed by heparin sepharose chromatography and anti-AID antibody mediated affinity purification to enrich complexes containing AID (Figure 1A, B; Figure S1B; Supp. Table 1; see Supp. Methods for details). At each step, fractions enriched for AID deamination stimulatory activity were identified via a 3H-release assay (e.g. Figure S1B; Supp. Methods). Among proteins identified by mass spectrometric analysis of purified complexes were multiple subunits of the RNA exosome complex, including Mtr3, Csl4, Rrp43, Rrp40, Rrp42 (Figure 1B; Supp. Table 1). To further elucidate potential functions, we assayed ability of the AID-associated, transcribed DNA complex to enhance deamination activity of purified AID in a transcribed dsDNA SHM substrate assay (Chaudhuri et al., 2003), and found that it markedly stimulated AID activity (Figure 1C). Notably, AID association with the RNA exosome complex and purification of an AID-stimulatory activity was not observed if the purification was performed from a reaction without T7 polymerase, indicating that complex formation is enhanced by transcription (Figure S1B; data not shown).

Figure 1. AID forms a transcription-Dependent complex with RNA Exosome.

(A) Schematic outlining steps for enrichment of transcription dependent AID/RNA exosome/SHM substrate complex. Details are in text and supplementary methods. (B) Proteins enriched by purification scheme in panel A were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by staining with Coomassie Blue. Identity of proteins from selected bands was determined by mass spectrometry; bands that contain RNA exosome sub-units are indicted on the right with molecular weight markers on the left. (C) AID purified following ectopic expression in HEK293 cells was assayed in a 3H-release in vitro transcription dependent SHM substrate assay (Chaudhuri et al., 2003; see also Figure 5) in presence or absence of complex enriched by purification scheme in panel A. Percent of total transcribed DNA substrate deaminated is presented for 3 separate assays. See also Figure S1.

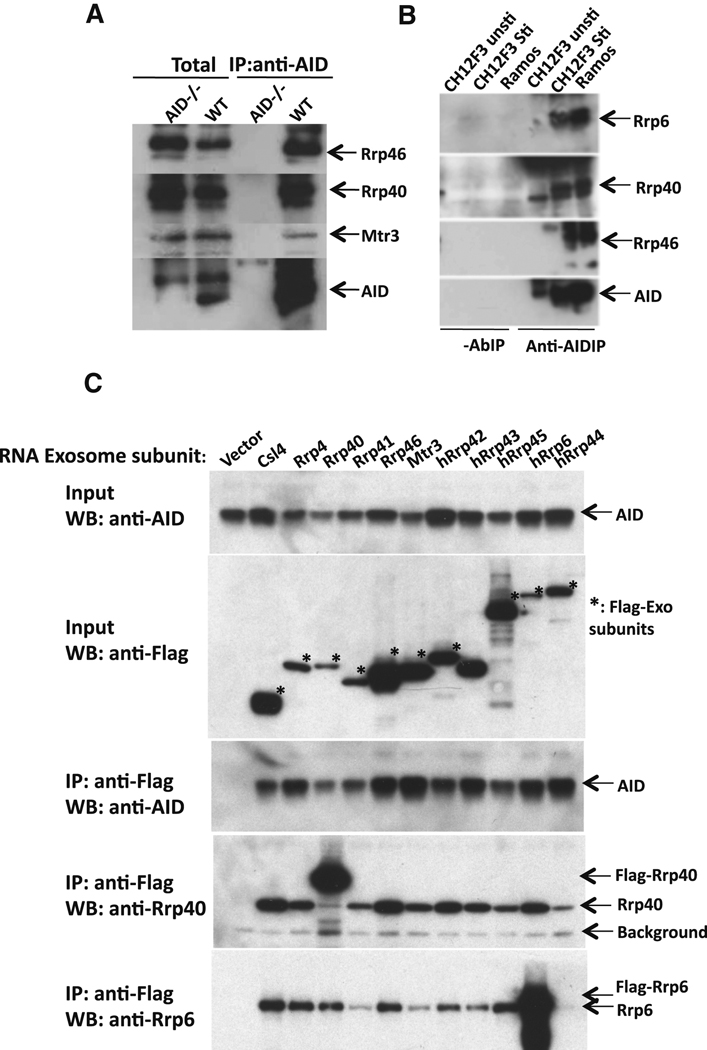

To assay for AID/RNA exosome association in vivo, we immunoprecipitated AID from mouse primary splenic B cells stimulated with anti-CD40 plus IL-4 to induce AID and CSR to IgG1 and then assayed immunoprecipitates for RNA exosome sub-units by Western blotting. These analyses revealed that AID associated with Rrp40, Rrp46, and Mtr3 RNA exosome subunits (Figure 2A). Likewise, AID immunoprecipitated from mouse CH12F3 B lymphoma cells stimulated with anti-CD40, IL-4 and TGF-β to undergo CSR to IgA, as well as AID immunoprecipated from the Human Ramos B lymphoma cells, associated with core Rrp40 and Rrp46 subunits, as well as with the Rrp6 catalytic exosome subunit (Figure 2B). By individually expressing FLAG-tagged versions of RNA exosome subunits along with AID in HEK293T cells, we observed that immunoprecipitation of any of the eleven exosome core and catalytic subunits via anti-FLAG antibodies also pulled down AID (Figure 2C). Together, our findings indicate that AID either directly or indirectly associates with the RNA exosome complex in cells.

Figure 2. AID complexes with RNA exosome subunits in vivo.

(A) AID immunoprecipitates from extracts of CSR-activated AID-deficient and wild-type B cells were assayed for Rrp40, Rrp46, Mtr3 and AID (indicated on the right) via Western blotting. The left two lanes show Western blotting of total extract and the right two lanes show Western blotting of immunoprecipitated products. (B) AID immunprecipitates ("Anti-AIDIP" lanes) or control reactions without anti-AID antibody ("-AbIP" lanes) from Ramos ("Ramos") and CSR-activated CH12F3 cells ("CH12F3 Sti") were assayed for Rrp46, Rrp40, Mtr3 and AID (indicated on right) by Western blotting. Un-stimulated CH12F3 cells ("CH12F3 unsti") were used as a negative control. (C) AID was co-expressed with individual FLAG-epitope tagged RNA exosome subunits in HEK293T cells. Lanes from left to right represent cells transfected with empty vector ("vector") as a control or the individual FLAG-epitope tagged subunit indicated at the top. The top two panels show Western blotting of total extract ("input") and the bottom three panels show western blotting with indicated antibodies (anti-AID, anti-Rrp40 and anti-Rrp6) following immunopreciptitation with anti-Flag antibodies. Asterisks indicate bands corresponding to Flag-tagged exosome subunits. A background band corresponding to the anti-Flag Ig light chain also is indicated (“Background").

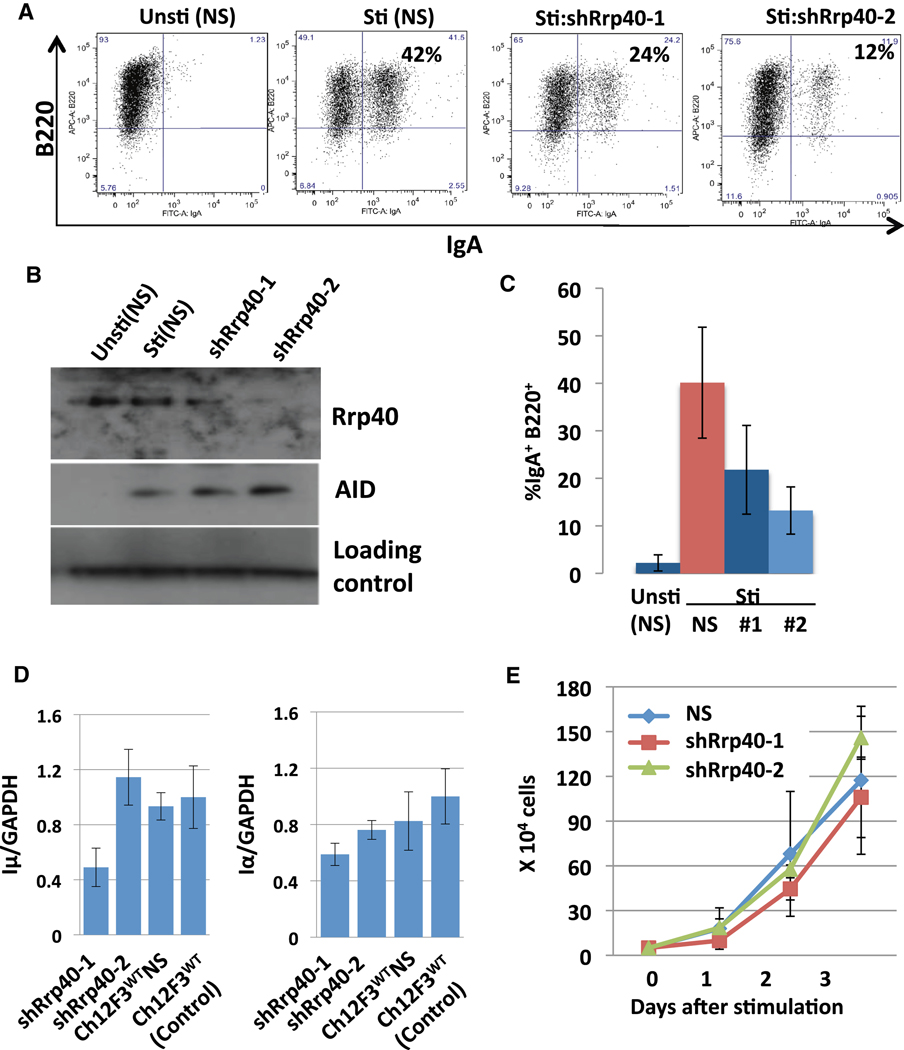

Exosome core sub-unit Rrp40 is required for optimal CSR

Previous work indicates that absence of given core exosome subunit leads to a severe defect in overall RNA exosome function (Jensen and Moore, 2005). Therefore, to evaluate potential roles of the RNA exosome complex in CSR, we used a knock-down approach to reduce Rrp40 in the CH12F3 B lymphoma line. For this purpose, we lentivirally-introduced two different shRNAs that targeted Rrp40, respectively, into CH12F3 cells to generate 3 different knockdown lines that had Rrp40 levels ranging from about 50% to less than 10% those of controls including a WT line and a line harboring a non-specific ("scrambled") shRNA (Figure 3B; Figure S2C). Following stimulation with anti-CD40, TGFβ and IL4 for 48hrs to induce CSR to IgA, Rrp40 knock-down lines consistently displayed reduced CSR, with levels ranging from 30–50% those of controls (Figure 3A,C; Figure S2B). However, the various Rrp40 knock-down lines proliferated similarly to controls after stimulation (Figure 3E and Figure S2A,E). In addition, the knock-down and control lines expressed similar levels of Iµ and Iα transcripts and similar levels of AID; while there were variations in transcript levels from clone to clone, there was no correlation with CSR and Rrp40 levels (Figure 3D; Figure S2F). Finally, similar knockdowns of the Mtr3 RNA exosome core sub-unit also led to decreased CSR without markedly affecting cell proliferation, AID levels, or Iµ and Iα transcription (Figure S3). Together, these findings demonstrate that physiological levels of RNA exosome core subunits are required for efficient CSR.

Figure 3. RNA exosome subunit Rrp40 is required for normal CSR.

(A) CH12F3 cells lenti-virally infected with a scrambled short hairpin plasmid (NS) or with shRNA against Rrp40 (shRrp40) were either not stimulated ("Unsti") or stimulated ("Sti") for 2 days with anti-CD40, IL4, and TGFβ and analyzed for IgA CSR by flow cytometry. ShRrp40-1 and shRrp40-2 are independent shRrp40-expressing CH12F3 isolates. Results are representative of 8 experiments; additional experiments shown in Fig. S2A,B. (B) NS, shRrp40-1 and shRrp40-2 expressing stimulated and un-stimulated CH12F3 isolates (shown in Panel A) were assayed for Rrp40 and AID by Western blotting. Results representative of 4 experiments; additional experiment in Fig. S2. (C) Average levels and standard deviation from the mean of CSR to IgA from three independent experiments (one shown in Panel A) performed simultaneously with un-stimulated ("unsti") NS, and stimulated ("Sti") NS, shRrp40-1 ("#1") and ShRrp40-2 ("#2") CH12F3 isolates. Five additional experiments gave similar results (Fig. S2A,B). (D) Total cellular RNA from 3 independently stimulated samples of indicated CH12F3 isolates (the ones used for Panel C) was assayed for Iµ transcripts (left panel) and Iα transcripts (right panel) via quantitative RT-PCR. Average and standard deviation from the mean is shown for the three separate experiments. Additional experiment based on Northern or RT-PCR is shown in Fig. S2F. (E) Growth curves of stimulated (NS), shRrp40-1 and shRrp40-2 CH12F3 cells calculated from three independent sets of three experiments (one used for panel C and others shown Fig. S2A) with a fourth set of 3 experiments indicated in Fig. S2E. Values represent average and standard deviation from the mean.

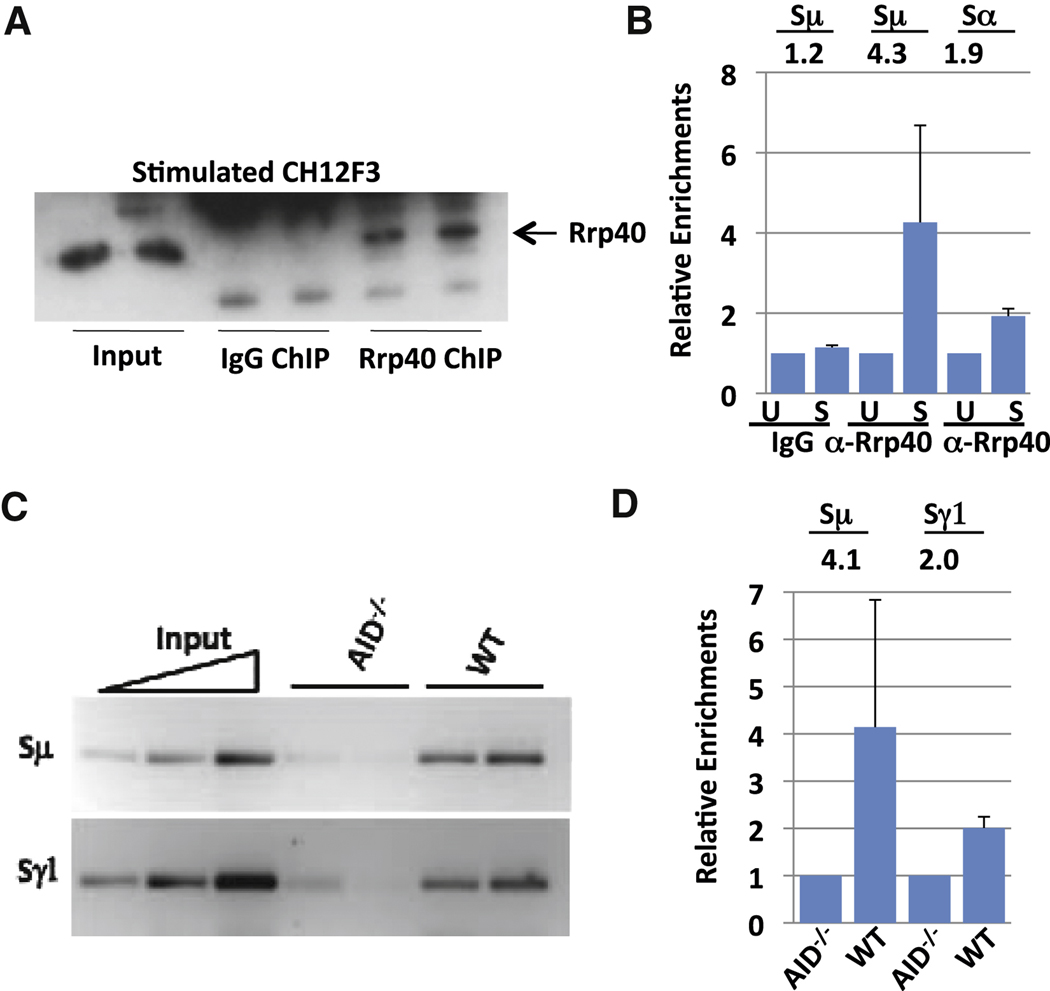

Association of Rrp40 with S regions in B cells activated for CSR

If the RNA exosome functions to target AID activity, it should be found in association with transcribed S regions in B cells activated for CSR. To evaluate this possibility, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays to test whether Rrp40 associates with transcribed Sµ sequences in activated CH12F3 cells before and after stimulation for CSR to IgA. We first employed western blotting to confirm that Rrp40 is specifically precipitated with an anti-Rrp40 antibody, but not control IgG, under ChIP conditions (Figure 4A). After processing immunoprecipitates for isolation of bound DNA, we utilized quantitative PCR (q-PCR) to determine levels of Rrp40 bound to Sµ and Sα. These analyses demonstrated enrichment of Sµ and, to a lesser extent, Sα in the anti-Rrp40 ChIPs from stimulated versus un-stimulated CH12F3 cells (Figure 4B; Figure S4). As there is some Sµ transcription in non-activated B cells (Muramatsu et al., 2000), the question arises as to whether transcription per se is sufficient to recruit the RNA exosome to S regions. To explore this question, we assayed for Rrp40 recruitment to Sµ and Sγ1 in WT and AID-deficient primary B cells activated with anti-CD40 and IL-4, which induces germline Sγ1 transcription in both cell types (Muramatsu et al., 2000). Consistent with targeting dependent on germline transcription, Rrp40 was recruited to Sµ and Sγ1 in the activated WT B cells (Figure 4C, D; Figure S4). Notably, however, Rrp40 was not measurably recruited to Sµ and Sγ1 in AID-deficient B cells. Together, our results indicate that the RNA exosome complex is recruited to transcribed S regions in B cells activated for CSR in an AID-dependent fashion.

Figure 4. RNA exosome subunit Rrp40 is recruited to S regions.

(A) Ch12F3 cells were either stimulated with TGFβ, IL4 and CD40 or kept un-stimulated for 48 hours. Subsequently, Rrp40 was immunoprecipitated from cell extracts under chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) conditions and immunoprecipitates analyzed for Rrp40 by Western blotting with anti-Rrp40. (B) The "ChIPed" Rrp40-DNA complex from Ch12F3 cells was processed to isolate bound DNA. ChIPed DNA was tested for Sµ and Sα sequences via q-PCR. The average and standard deviation from the mean for three separate ChIP experiments is shown (see also Fig. S4). Numbers indicate average fold changes comparing stimulated and un-stimulated samples. Un-stimulated samples were arbitrarily normalized as 1 (Supp. Methods). (C) Rrp40 ChIPs were performed on extracts from primary splenic B cells stimulated for 2 days with anti-CD40 plus IL4. Sµ and Sγ1 were tested via semi-quantitative PCR; results are shown for two independent ChIP samples for each genotype. A 5-fold serial dilution of inputs is shown with the highest input concentration corresponding to 1/20 of total input. (D) ChIPed DNA from activated splenic B cells was tested for Sµ and Sγ1 via q-PCR. Numbers indicate average fold changes comparing WT and AID−/− samples. AID−/− samples were arbitrarily normalized as 1 (Supp. Methods). Values represent the average and standard deviation from the mean for three experiments. See Figure S4 for more details.

RNA exosome stimulates AID Activity on Template and Non-Template Strands

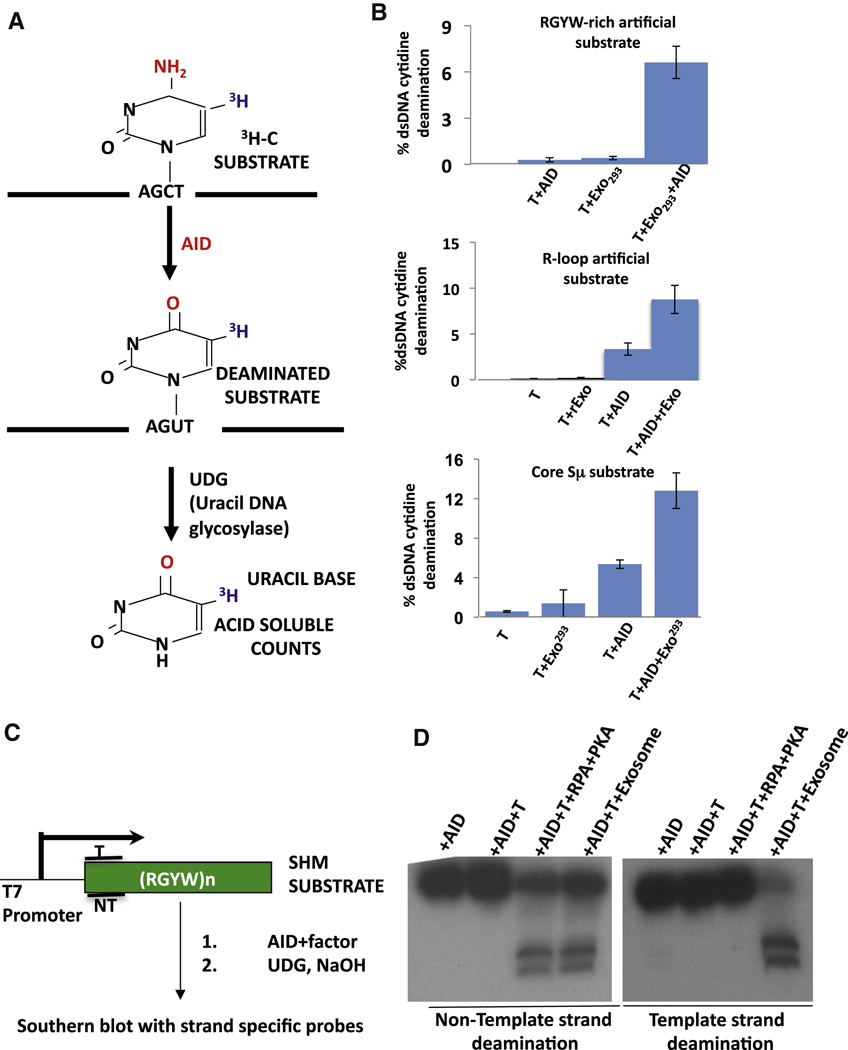

To further evaluate the potential ability of the cellular RNA exosome complex to act as an AID co-factor, we substantially purified this complex from cell-free nuclear extracts prepared from HEK293T cells that expressed a FLAG-epitope tagged Rrp6 exosome sub-unit. In this purification, we maintained relatively low salt concentrations to prevent disaggregation of protein complexes (Figure S5). To test activity, we added varying amounts of the exosome-enriched extract to a 3H-uracil-release in vitro transcription-dependent AID deamination assay, which measures overall SHM substrate deamination (Figure 5A). In this assay, T7 polymerase transcription of the SHM substrate leads to little or no AID deamination activity and addition of partially purified RNA exosome extract in the absence of AID also gives no deamination activity on the T7 transcribed substrate (Figure 5B). However, addition of both AID and partially purified RNA exosome led to substantial deamination of the transcribed substrate (Figure 5B), with activity appearing to be, roughly, within a range similar to that observed with phosphorylated AID and RPA ((Basu et al., 2005; Basu et al., 2008; Chaudhuri et al., 2004); see below). The AID deamination stimulatory activity observed in these extracts is likely mediated by the exosome complex; since we found that deamination activity co-fractionated with the RNA exosome during purification (Figure S5). Likewise, we found similar results when we purified the exosome complex from HEK293T cells via an approach in which affinity purification of the complex was performed with antibodies against endogenous Rrp40 (Figure S5D). Finally, we found that the RNA exosome also stimulated AID deamination of a transcribed dsDNA core Sµ substrate and a synthetic R-loop forming substrate (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5. Cellular RNA exosome augments transcription-dependent AID deamination activity on template and non-template DNA strands.

(A) Schematic representation of 3H release assay for AID deamination of transcribed dsDNA SHM substrate. (B) Top Panel: Results of 3H release assay in which a SHM substrate was transcribed by T7 polymerase (T) in the presence of purified AID (AID), purified HEK293 RNA exosome (Exo293) or both. Middle Panel: Results of 3H release assay in which a synthetic R-loop forming substrate was transcribed by T7 polymerase (T) in the presence of purified AID (AID), recombinant RNA exosome (rExo) or both. Bottom Panel: Results of 3H release assay in core Sµ substrate was transcribed by T7 polymerase (T) in the presence of purified AID (AID), purified HEK293 RNA exosome (Exo293) or both. In all three panels, values represent average and standard deviation from the mean from three independent experiments. (C) A schematic representation of assay for measuring strand-specific AID deamination of a transcribed dsDNA SHM. The location of template (T) and non-template (NT) strand probes is indicated. (D) The strand-specificity of RPA-dependent or RNA exosome-dependent DNA deamination was analyzed by the assay in panel C using either non-template (left panel) or template (right panel) strand-specific probes. Reactions contained AID, T7 polymerase (T), RPA and PKA, or purified HEK293 exosome ("Exosome") as indicated. See also Fig. S6.

Because the RNA exosome can associate with Pol II transcription complexes and remove nascent transcripts from transcribed DNA (El Hage et al., 2010), we considered it as a candidate AID co-factor for template DNA strand deamination. To test this possibility, we performed in vitro transcription-dependent AID dsDNA SHM substrate deamination assays in which the Southern blotting read-out reveals deamination of either template or non-template strands, respectively (Figure 5C) (Chaudhuri et al., 2004). In this assay, no deamination of either strand was observed when only AID was added in the presence or absence of T7 polymerase (Figure 5D; Figure S6A). As observed previously, addition of PKA (to phosphorylate AID on S38) and RPA along with T7 polymerase and AID led to deamination of the non-template strand but not the template strand (Figure 5D; Figure S6A). Strikingly, addition of both AID and partially purified RNA exosome (in the absence of RPA or PKA) to the T7-transcription reaction led to deamination of both strands of the SHM substrate (Figure 5D; Figure S6A, E). In most assays, activity on both template and non-template strands, respectively, was robust, as evidenced by greatly diminished levels of full-length substrate strands (Figure 5D; Figure S6A). The RNA exosome also enhances AID template strand deamination activity on transcribed core Sµ substrate and synthetic R loop-forming substrates (Figure 5B; Figure S6B, C). Together, our findings indicate that the endogenous RNA exosome complex can function as a stimulatory co-factor for AID deamination activity on both strands of transcribed duplex SHM substrates.

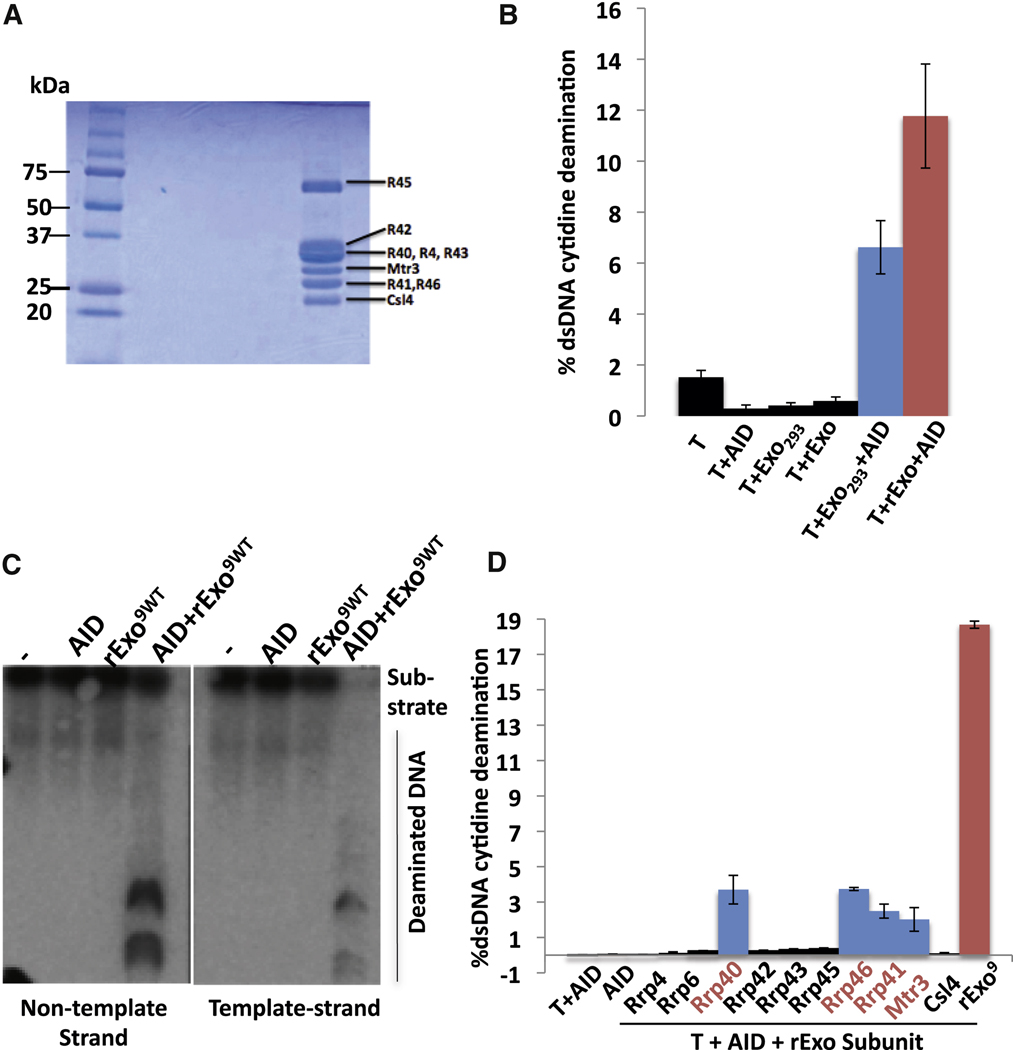

Recombinant Core RNA Exosome Stimulates AID-dependent Deamination on Template and Non-Template Strands

The partially purified endogenous RNA exosome preparation should contain the core structural complex as well as catalytic sub-units (e.g. Rrp6 which was used to pull down the complex) and potentially other co-factors or contaminating proteins. To unequivocally evaluate the ability of the RNA exosome to stimulate AID activity on transcribed SHM substrates and to also obtain insight into potential mechanisms, we assayed a 9 sub-unit recombinant human RNA exosome core complex reconstituted from subunits that were individually purified subsequent to expression in bacteria (Figure 6A)(Greimann and Lima, 2008; Liu et al., 2006). We found that, when titrated for optimal activity (Figure S6E), the recombinant RNA exosome core complex robustly stimulated AID-dependent deamination of transcribed SHM substrates as measured by the H3-uracil release assay (Figure 6B; Figure S6F). In fact, maximum deamination levels stimulated by the recombinant core complex were roughly similar to those obtained with partially purified RNA exosome complex (Figure 6B; Figure S6F). Moreover, the recombinant RNA exosome core complex also stimulated AID-dependent deamination of both template and non-template strands of the SHM substrate (Figure 6C; Figure S6G) and synthetic R-loop forming substrates (Figure S6C). Thus, the core RNA exosome complex alone, in the absence of the RNAase catalytic sub-units, promotes AID- and transcription-dependent SHM substrate deamination.

Figure 6. Recombinant core RNA exosome and individual subunits stimulate AID activity.

(A) Coomassie blue stained polyacrylamide gel electrophoreisis analysis of the 9 subunit recombinant RNA exosome complex generated from individual subunits. (B) Comparative analysis of the ability of RNA exosome complex from 293T cells (Exo293) and recombinant RNA core exosome complex (rExo) to stimulate AID deamination activity as measured by 3H release/SHM substrate assay in Fig. 5A. See Supp. Methods and Fig. S6 for details. Optimal amounts of RNA exosome293T and recombinant RNA exosome core complex were used (Fig. S6; Supp. Methods). (C) Assay of recombinant exosome complex to stimulate strand-specific AID deamination of a transcribed SHM substrate via assay in Fig. 5C. Non-template and template strand deamination are shown on left and right panels, respectively. Reactions contained either AID, recombinant core RNA exomsome (rExo9wt) or both (AID + rExo9wt) as indicated. (D) Individual recombinant RNA exosome subunits were assayed for ability to promote AID deamination of a T7-transcribed SHM substrate as outlined in Fig. 5A. Added exosome components are indicated. Control reactions with AID alone or AID plus T7 polymerase are on the left. A positive control with complete recombinant core RNA exosome (rExo9) plus T7 and AID is on the right. For panels B and D, values represent the average and standard deviation from the mean for three independent experiments. See also Figure S 6&7.

To further characterize potential functions of the core RNA exosome, we assayed individual core subunits (Figure 6D and Figure S7). Individual subunits were assayed at approximately the same molarity as when assayed in the context of the core complex. Some, but not all, recombinant core RNA exosome subunits stimulated AID- and transcription-dependent SHM substrate deamination activity; however, the level of stimulation was low compared to that of the full core complex (Figure 6D; Figure S7A). The RNA binding subunits Rrp40, Rrp46, Rrp41 and Mtr3 showed low levels of activity (Figure 6D and Figure S7A,C). On the other hand, other core sub-units with demonstrated RNA binding activity and/or RNA binding domains, along with the Rrp6 ribonuclease sub-unit, lacked detectable activity indicating that the observed activity is not a property of all such proteins

DISCUSSION

Enigma of AID Targeting of the Template Substrate Strand

Recent studies revealed a mechanism by which AID can be brought to transcribed substrates in the context of RNA Polymerase II pausing (Pavri et al., 2010). Once recruited to the substrate, transcription-based mechanisms also provide a potential means of providing AID with a ssDNA substrate in the context of a duplex substrate via looping out of the non-template strand (Chaudhuri et al., 2004; Chaudhuri et al., 2003; Gomez-Gonzalez and Aguilera, 2007; Ramiro et al., 2003; Yu et al., 2003b). However, AID equally deaminates both substrate DNA strands during CSR and SHM (Milstein et al., 1998; Shen et al., 2006; Xue et al., 2006). In the latter context, the mechanism by which AID generates DSB intermediates that are substrates for CSR (Peterson et al., 2001; Schrader et al., 2005; Wuerffel et al., 1997) and for chromosomal translocations (Ramiro et al., 2004; Robbianni et al., 2008) requires targeting of both DNA strands (e.g. Xue et al., 2006; reviewed by "Di Noia and Neuberger, 2007). Thus, the mechanism by which AID accesses the template DNA strand has been a major question (e.g. Chaudhuri et al., 2007; Chelico et al., 2009; Di Noia and Neuberger, 2007; Liu and Schatz, 2009; Longerich et al., 2006; Maul and Gearhart, 2010; Pavri et al., 2010; Peled et al., 2008). We now show that the core RNA exosome complex promotes AID deamination of both template and non-template strands of in vitro transcribed SHM substrates. Moreover, in B cells activated for CSR, the RNA exosome complex associates with AID and accumulates on S regions in an AID-dependent manner. Finally, integrity of the RNA exosome complex is required for optimal CSR. Thus, the RNA exosome is a long sought co-factor that can target AID activity to both template and non-template strands of transcribed SHM and CSR targets.

Implications of AID/RNA Exosome Biochemistry

Our In vivo knock-down, ChIP, and physical association studies provide strong biological evidence that the RNA exosome functions in CSR. However, such studies often provide limited mechanistic insight. In addition, as elimination of RNA exosome core sub-units is cell lethal in yeast; it may be difficult to achieve complete knockdowns or knockouts to fully test extent of exosome function in promoting AID activity in vivo. Classical biochemistry has been extremely useful for elucidating potential functions of essential replication, repair, and recombination factors (e.g. Chaudhuri et al., 2004; Dzantiev et al., 2004; Genschel and Modrich, 2003; Maldonado et al., 1996; Stillman and Gluzman, 1985). In this context, our biochemical studies reveal that the core RNA exosome robustly targets AID to both strands of T7 polymerase-transcribed SHM substrates in vitro. Clearly, T7 polymerase is structurally and mechanistically distinct from mammalian RNA PoI II, and the in vitro system we have employed does not operate in the chromatin context in which SHM and CSR occurs in vivo. Also, the concentration of the RNA exosome, and of other factors in our assays, may be greater than their cellular levels. But again, it is just these aspects of the biochemical assay that allow us to define what the RNA exosome has the potential of achieving. Additional mechanisms and factors (e,g, AID) likely will work to specifically recruit the RNA exosome to transcribed SHM and CSR targets in vivo (see below), potentially increasing local concentration to levels sufficient to achieve activities observed in vitro.

The evolutionarily conserved RNA exosome complex is required for degradation and/or processing of various RNAs, including non-coding RNAs generated in cells due to error-prone transcription or from transcription-initiated by cryptic promoters (Houseley et al., 2006; Jensen and Moore, 2005; Lykke-Andersen et al., 2009; Preker et al., 2008). In bacteria, the exosome core complex contains ribonuclease activity; however, in yeast and mammalian cells, the core subunits lack such activity and generally have been considered structural scaffolds (Greimann and Lima, 2008; Houseley et al., 2006; Jensen and Moore, 2005). In eukaryotes, non-core exosome sub-units or co-factors provide ribonuclease activity (Callahan and Butler, 2010; Greimann and Lima, 2008; Houseley et al., 2006; Lebreton et al., 2008; Schaeffer et al., 2009; Staals et al., 2010; Tomecki et al., 2010). Our biochemical data demonstrate that the recombinant 9 sub-unit exosome core, in the absence of catalytic subunits, robustly targets AID to both strands of T7 transcribed substrates. The precise molecular mechanism by which the RNA exosome core achieves this activity remains to be determined. In theory, it may compete with duplex DNA for binding the nascent transcript, thereby displacing it from the template strand; while also forming a scaffold that stabilizes the transcriptionally-opened template to expose both DNA strands. Our finding that certain core exosome subunits have low, but significant, ability to enhance AID deamination of in vitro transcribed substrates is intriguing. Currently, however, there is no clear correlation between any particular known sub-unit activity and which sub-units promote low level AID access.

We previously have shown that that RPA, a ssDNA binding protein involved in replication and repair, binds AID phosphorylated on S38 and, thereby, targets AID to transcribed SHM substrates in vitro, albeit mostly to the non-template strand (Basu et al., 2005; Chaudhuri et al., 2004). A substantial amount of evidence supports the significance of the AID/RPA interaction for AID function during CSR and SHM, both in augmenting AID deamination activity and also potentially in recruiting downstream repair pathways involved in further processing AID initiated lesions (Basu et al., 2005; Basu et al., 2008; Cheng et al., 2009; McBride et al., 2006; McBride et al., 2008; Pasqualucci et al., 2006). Notably, RNA exosome-mediated AID-targeting activity in our in vitro SHM assay does not require AID phosphorylation on S38 or RPA, demonstrating that the RNA exosome function in AID targeting is distinct. However, these two AID targeting mechanisms still might be complementary in vivo (see below).

Potential Mechanism by which the RNA Exosome Promotes AID Activity in vivo

Both CSR and SHM in activated B cells require transcription through target S regions or variable region exons. Such transcriptional targeting was proposed to result from association of a mutator factor with stalled Pol II within the target sequence (Peters and Storb, 1996). Over the years, this model has been supported by numerous findings including: AID, now known to be the hypothetical mutator, is targeted by transcription (reviewed by Chaudhuri et al., 2007; Yang and Schatz, 2007; Di Noia and Neuberger, 2007); AID associates with Pol II (Nambu et al., 2003); and Pol II indeed stalls during transcription through S regions (Rajagopal et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2009), potentially augmented by transcribed S regions forming secondary structures such as R loops (reviewed by Maul and Gearheart, 2010). Recent studies have implicated the Spt5 transcriptional elongation co-factor in recruiting AID to stalled Pol II and, thereby, bringing AID to transcribed genomic targets (Pavri et al., 2010). However, the AID/Spt5/Pol II interaction did not explain how AID actually accesses its target sequences once there and, in particular, how AID accesses the template DNA strand (Pavri et al., 2010), a process in which we now have implicated the RNA exosome. The recruitment of the RNA exosome to S regions in B cells activated for CSR, in theory, might involve a putative Spt5/RNA exosome interaction (Andrulis et al., 2002) or generation of the non-coding S region transcripts (Lennon and Perry, 1985 Lutzker and Alt, 1988), the latter of which might attract the RNA exosome complex (reviewed by Houseley et al., 2006; Jensen and Moore, 2005; Schmid and Jensen, 2008). However, the marked AID-dependence of exosome recruitment to targeted S regions in activated B cells rules out Spt5 interaction or germline transcription alone for RNA exosome recruitment. While AID might directly recruit the RNA exosome complex; we, thus far, have not found interaction with individual purified subunits, raising the additional possibility of indirect recruitment, for example via an AID/transcription-related complex.

We propose a working model for how the RNA exosome may enhance targeting of AID to both DNA strands of its in vivo substrates (Supp. Fig. 8). This model is based on our current biochemical and cellular findings regarding relationships between AID and the RNA exosome, known aspects of AID function and recruitment to transcribed target sequences, and known RNA exosome properties. To enhance AID activity on the template strand, the RNA exosome must in some way remove the template RNA. As the RNA exosome is not known to engage RNA substrates that lack a free single stranded 3' end, co-transcriptional RNA exosome activity where a RNA in the RNA/DNA hybrid is still attached to the RNA polymerase would seem unlikely. Therefore, we suggest that the RNA exosome would have its relevant activity on stalled Pol II units that backtrack to reveal a free 3' end (Adelman et al., 2005) (Supp. Fig. 8a). In this context, stalled RNA polymerase recruits AID via the Spt5 transcription factor (Pavri et al., 2010). Thus, Pol II stalling would indirectly recruit the RNA exosome via AID (Supp. Fig. 8b). Likewise, Pol II stalling would also provide a suitable substrate to engage the RNA exosome and allow it to enhance AID substrate activity (Sup. Fig. 8b), potentially via mechanisms mentioned in the preceding section of the Discussion or below. We further suggest that RPA might bind to and stabilize ssDNA targets opened up by the RNA exosome and facilitate S38-phosphorylated AID accumulation via direct interaction (Basu et al., 2005; Basu et al., 2008; Vuong et al. 2009) (Supp. Fig. 8c,d). In addition, bound RPA may facilitate engagement of downstream repair pathways (Chaudhuri, Khuong, and Alt, 2004; Vuong et al., 2009). We must note that it remains possible, in vivo, that the catalytic subunit of the RNA exosome could provide ribonuclease activity that would degrade the nascent transcript from the DNA/RNA hybrids on transcribed AID substrates and, thereby, further contribute to exposing the template strand to AID activity (Supp. Fig. 8E). Finally, we do not rule out the possibility that RNA exosome, in the context of an AID complex, acquires unique properties as compared to those already known the RNA exosome and that these are relevant to enhancing AID activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Recombinant plasmids, antibodies and proteins

RNA exosome subunits, AID, and RPA were expressed as described (Greimann and Lima, 2008; Chaudhuri et al., 2004; Chaudhuri et al., 2003; Stillman and Gluzman, 1985). AID antibodies were generated as described (Chaudhuri et al., 2003) and anti-exosome sub-unit antibodies were purchased from Genway or AbCam. Exosome subunit and complex purifications were as described (Greimann and Lima, 2008). Details are in Supplementary Methods.

AID activity assays

The 3H-release assay was performed essentially as described (Chaudhuri et al., 2003; Basu et al., 2005). The strand specific AID and transcription dependent dsDNA deamination assay was performed as described (Chaudhuri et al., 2004; Chaudhuri et al., 2003). Details are in Supplementary Methods.

AID complex purification from Ramos cells

We used a combination of DNA affinity, size chromatography and affinity purification for isolating AID complexes. We analyzed components of the complex via mass spectrometry. For details, see Extended Supplementary Methods.

RNA exosome purification from 293T cells

We generated protein extracts from HEK293 cells expressing FLAG-epitope tagged Rrp6. We used a combination of size chromatography, glycerol gradient sedimentation and FLAG affinity purification to isolate a protein complex enriched with RNA exosome complex. We also isolated RNA exosome from HEK293 cells using the same approach except that the affinity purification step employed anti-Rrp40 antibodies. For details see Extended Supplementary Methods.

Immunoprecipitation of AID/RNA exosome complex from B cells and HEK293 cells

We utilized previously published protocols to immunoprecipitate the AID complex from B cells (Chaudhuri et al. 2004; Basu et al. 2005); or similarly adapted protocols for immunoprecipitating FLAG-exosome subunits from 293 cells. For details, see Extended Supplementary Methods.

CSR analysis of Rrp40-deficient CH12F3 cells

We performed shRNA-mediated knockdowns in Ch12F3 according to TRC shRNA library protocols. Knockdown efficiencies were measured by detecting levels of Rrp40 in these cells by western blotting. We determined levels of germline S region transcripts in Rrp40-deficient cell via previously published protocols (Muramatsu et al. 2000). For details, see Extended Supplementary Methods.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation assays

We utilized adaptations of previously published protocols (Chaudhuri et al., 2004) for isolating chromatin immunoprecipitates of Rrp40. See Extended Supplementary Methods for details.

Other Material and Methods

See Extended Supplementary Methods for further details.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Bjoern Schwer, Jason Rodriguez, Stephen Goff, Bruce Stillman and Tasuku Honjo for providing reagents and/or protocols. We also thank Bjoern Schwer and Cosmas Giallourakis for critically reading the manuscript. This work was supported by National Insititute of Health grants AI31541 (to F.W.A.) and GM079196) (to K.J. and C.D.L.), by Trustees of Columbia University Faculty start up funds (to U.B.), and by funds from Regeneron Pharmaceuticals (in support of E.P). FLM is a fellow of Cancer Research Institute of New York. CK was supported by a Cancer Biology training grant CA09503-23 (C.K.) KJ is fellow of the American Cancer Society (PF-10-236-01-RMC). UB is a Special Fellow of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society of America and the recipient of New Investigator Award from the Leukemia Research Foundation (U.B.). F.W.A. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Adelman K, Marr MT, Werner J, Saunders A, Ni Z, Andrulis ED, Lis JT. Efficient release from promoter-proximal stall sites requires transcript cleavage factor TFIIS. Mol Cell. 2005;17:103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JR, Mukherjee D, Muthukumaraswamy K, Moraes KC, Wilusz CJ, Wilusz J. Sequence-specific RNA binding mediated by the RNase PH domain of components of the exosome. RNA. 2006;12:1810–1816. doi: 10.1261/rna.144606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrulis ED, Werner J, Nazarian A, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Lis JT. The RNA processing exosome is linked to elongating RNA polymerase II in Drosophila. Nature. 2002;420:837–841. doi: 10.1038/nature01181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu U, Chaudhuri J, Alpert C, Dutt S, Ranganath S, Li G, Schrum JP, Manis JP, Alt FW. The AID antibody diversification enzyme is regulated by protein kinase A phosphorylation. Nature. 2005;438:508–511. doi: 10.1038/nature04255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu U, Wang Y, Alt FW. Evolution of phosphorylation-dependent regulation of activation-induced cytidine deaminase. Mol Cell. 2008;32:285–291. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besmer E, Market E, Papavasiliou FN. The transcription elongation complex directs activation-induced cytidine deaminase-mediated DNA deamination. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:4378–4385. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02375-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callahan KP, Butler JS. TRAMP complex enhances RNA degradation by the nuclear exosome component Rrp6. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:3540–3547. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.058396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri J, Basu U, Zarrin A, Yan C, Franco S, Perlot T, Vuong B, Wang J, Phan RT, Datta A, et al. Evolution of the immunoglobulin heavy chain class switch recombination mechanism. Adv Immunol. 2007;94:157–214. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(06)94006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri J, Khuong C, Alt FW. Replication protein A interacts with AID to promote deamination of somatic hypermutation targets. Nature. 2004;430:992–998. doi: 10.1038/nature02821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri J, Tian M, Khuong C, Chua K, Pinaud E, Alt FW. Transcription-targeted DNA deamination by the AID antibody diversification enzyme. Nature. 2003;422:726–730. doi: 10.1038/nature01574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chelico L, Pham P, Petruska J, Goodman MF. Biochemical basis of immunological and retroviral responses to DNA-targeted cytosine deamination by activation-induced cytidine deaminase and APOBEC3G. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:27761–27765. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R109.052449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H-L, Vuong B, Basu U, Franklin A, Schwer B, Phan R, Datta, Manis J, Alt FW, Chaudhuri J. Integrity of Serine-38 AID phosphorylation site is critical for somatic hypermutation and class switch recombination in mice. Proceeding of the national Academy of Sciences. 2009;106(8):2717–2722. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812304106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels GA, Lieber MR. RNA:DNA complex formation upon transcription of immunoglobulin switch regions: implications for the mechanism and regulation of class switch recombination. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:5006–5011. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.24.5006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Noia JM, Neuberger MS. Molecular mechanisms of antibody somatic hypermutation. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:1–22. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.061705.090740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson SK, Market E, Besmer E, Papavasiliou FN. AID mediates hypermutation by deaminating single stranded DNA. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1291–1296. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzantiev L, Constantin N, Genschel J, Iyer RR, Burgers PM, Modrich P. A defined human system that supports bidirectional mismatch-provoked excision. Mol Cell. 2004;15:31–41. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Hage A, French SL, Beyer AL, Tollervey D. Loss of Topoisomerase I leads to R-loop-mediated transcriptional blocks during ribosomal RNA synthesis. Genes Dev. 2010;24:1546–1558. doi: 10.1101/gad.573310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genschel J, Modrich P. Mechanism of 5'-directed excision in human mismatch repair. Mol Cell. 2003;12:1077–1086. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00428-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Gonzalez B, Aguilera A. Activation-induced cytidine deaminase action is strongly stimulated by mutations of the THO complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:8409–8414. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702836104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greimann JC, Lima CD. Reconstitution of RNA exosomes from human and Saccharomyces cerevisiae cloning, expression, purification, and activity assays. Methods Enzymol. 2008;448:185–210. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)02610-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honjo T, Kinoshita K, Muramatsu M. Molecular Mechanism of Class Switch Recombination: Linkage with Somatic Hypermutation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:165–196. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.090501.112049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houseley J, LaCava J, Tollervey D. RNA-quality control by the exosome. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:529–539. doi: 10.1038/nrm1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houseley J, Tollervey D. The nuclear RNA surveillance machinery: the link between ncRNAs and genome structure in budding yeast? Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1779:239–246. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang FT, Yu K, Balter BB, Selsing E, Oruc Z, Khamlichi AA, Hsieh CL, Lieber MR. Sequence dependence of chromosomal R-loops at the immunoglobulin heavy-chain Smu class switch region. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:5921–5932. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00702-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang FT, Yu K, Hsieh CL, Lieber MR. Downstream boundary of chromosomal R-loops at murine switch regions: implications for the mechanism of class switch recombination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:5030–5035. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506548103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen TH, Moore C. Reviving the exosome. Cell. 2005;121:660–662. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaCava J, Houseley J, Saveanu C, Petfalski E, Thompson E, Jacquier A, Tollervey D. RNA degradation by the exosome is promoted by a nuclear polyadenylation complex. Cell. 2005;121:713–724. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebreton A, Tomecki R, Dziembowski A, Seraphin B. Endonucleolytic RNA cleavage by a eukaryotic exosome. Nature. 2008;456:993–996. doi: 10.1038/nature07480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennon GG, Perry RP. Cmu-containing transcripts initiate heterogeneously within the IgH enhancer region and contain a novel 5'-nontranslatable exon. Nature. 1985;318:475–478. doi: 10.1038/318475a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Manley JL. Inactivation of the SR protein splicing factor ASF/SF2 results in genomic instability. Cell. 2005;122:365–378. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieber MR. The mechanism of double-strand DNA break repair by the nonhomologous DNA end-joining pathway. Annu Rev Biochem. 2010;79:181–211. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.052308.093131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M, Schatz DG. Balancing AID and DNA repair during somatic hypermutation. Trends Immunol. 2009;30:173–181. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Greimann JC, Lima CD. Reconstitution, activities, and structure of the eukaryotic RNA exosome. Cell. 2006;127:1223–1237. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longerich S, Basu U, Alt F, Storb U. AID in somatic hypermutation and class switch recombination. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18:164–174. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lykke-Andersen S, Brodersen DE, Jensen TH. Origins and activities of the eukaryotic exosome. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:1487–1494. doi: 10.1242/jcs.047399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutzker S, Alt FW. Structure and expression of germ line immunoglobulin gamma 2b transcripts. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:1849–1852. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.4.1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado E, Shiekhattar R, Sheldon M, Cho H, Drapkin R, Rickert P, Lees E, Anderson CW, Linn S, Reinberg D. A human RNA polymerase II complex associated with SRB and DNA-repair proteins. Nature. 1996;381:86–89. doi: 10.1038/381086a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maul RW, Gearhart PJ. AID and somatic hypermutation. Adv Immunol. 2010;105:159–191. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(10)05006-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride KM, Gazumyan A, Woo EM, Barreto VM, Robbiani DF, Chait BT, Nussenzweig MC. Regulation of hypermutation by activation-induced cytidine deaminase phosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:8798–8803. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603272103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride KM, Gazumyan A, Woo EM, Schwickert TA, Chait BT, Nussenzweig MC. Regulation of class switch recombination and somatic mutation by AID phosphorylation. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2585–2594. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milstein C, Neuberger MS, Staden R. Both DNA strands of antibody genes are hypermutation targets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:8791–8794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muramatsu M, Kinoshita K, Fagarasan S, Yamada S, Shinkai Y, Honjo T. Class switch recombination and hypermutation require activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), a potential RNA editing enzyme. Cell. 2000;102:553–563. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nambu Y, Sugai M, Gonda H, Lee CG, Katakai T, Agata Y, Yokota Y, Shimizu A. Transcription-coupled events associating with immunoglobulin switch region chromatin. Science. 2003;302:2137–2140. doi: 10.1126/science.1092481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuberger MS, Harris RS, Di Noia J, Petersen-Mahrt SK. Immunity through DNA deamination. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:305–312. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00111-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oddone A, Lorentzen E, Basquin J, Gasch A, Rybin V, Conti E, Sattler M. Structural and biochemical characterization of the yeast exosome component Rrp40. EMBO Rep. 2007;8:63–69. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odegard VH, Schatz DG. Targeting of somatic hypermutation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:573–583. doi: 10.1038/nri1896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasqualucci L, Kitaura Y, Gu H, Dalla-Favera R. PKA-mediated phosphorylation regulates the function of activation-induced deaminase (AID) in B cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:395–400. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509969103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavri R, Gazumyan A, Jankovic, Di Virgolio M, Kein I, Sobrinho C, Resch W, Yamane A, San-Martin B, Barreto V, Neilaand T, Root D, Casellas R, Nussenzweig M. Activation Induced Deaminase targets DNA at sites of RNA polymerase II stalled by interaction with Spt5. Cell. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peled JU, Kuang FL, Iglesias-Ussel MD, Roa S, Kalis SL, Goodman MF, Scharff MD. The biochemistry of somatic hypermutation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2008;26:481–511. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A, Storb U. Somatic hypermutation of immunoglobulin genes is linked to transcription initiation. Immunity. 1996;4:57–65. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80298-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen S, Casellas R, Reina-San-Martin B, Chen HT, Difilippantonio MJ, Wilson PC, Hanitsch L, Celeste A, Muramatsu M, Pilch DR, et al. AID is required to initiate Nbs1/gamma-H2AX focus formation and mutations at sites of class switching. Nature. 2001;414:660–665. doi: 10.1038/414660a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen-Mahrt SK, Harris RS, Neuberger MS. AID mutates E. coli suggesting a DNA deamination mechanism for antibody diversification. Nature. 2002;418:99–103. doi: 10.1038/nature00862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preker P, Nielsen J, Kammler S, Lykke-Andersen S, Christensen MS, Mapendano CK, Schierup MH, Jensen TH. RNA exosome depletion reveals transcription upstream of active human promoters. Science. 2008;322:1851–1854. doi: 10.1126/science.1164096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopal D, Maul RW, Ghosh A, Chakraborty T, Khamlichi AA, Sen R, Gearhart PJ. Immunoglobulin switch mu sequence causes RNA polymerase II accumulation and reduces dA hypermutation. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1237–1244. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramiro AR, Jankovic M, Eisenreich T, Difilippantonio S, Chen-Kiang S, Muramatsu M, Honjo T, Nussenzweig A, Nussenzweig MC. AID is required for c-myc/IgH chromosome translocations in vivo. Cell. 2004;118:431–438. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramiro AR, Stavropoulos P, Jankovic M, Nussenzweig MC. Transcription enhances AID-mediated cytidine deamination by exposing single-stranded DNA on the nontemplate strand. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:452–456. doi: 10.1038/ni920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revy P, Muto T, Levy Y, Geissmann F, Plebani A, Sanal O, Catalan N, Forveille M, Dufourcq-Labelouse R, Gennery A, et al. Activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) deficiency causes the autosomal recessive form of the Hyper-IgM syndrome (HIGM2) Cell. 2000;102:565–575. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbiani DF, Bothmer A, Callen E, Reina-San-Martin B, Dorsett Y, Difilippantonio S, Bolland DJ, Chen HT, Corcoran AE, Nussenzweig A, et al. AID is required for the chromosomal breaks in c-myc that lead to c-myc/IgH translocations. Cell. 2008;135:1028–1038. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy D, Yu K, Lieber MR. Mechanism of R-loop formation at immunoglobulin class switch sequences. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:50–60. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01251-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffer D, Tsanova B, Barbas A, Reis FP, Dastidar EG, Sanchez-Rotunno M, Arraiano CM, van Hoof A. The exosome contains domains with specific endoribonuclease, exoribonuclease and cytoplasmic mRNA decay activities. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:56–62. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid M, Jensen TH. The exosome: a multipurpose RNA-decay machine. Trends Biochem Sci. 2008;33:501–510. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrader CE, Linehan EK, Mochegova SN, Woodland RT, Stavnezer J. Inducible DNA breaks in Ig S regions are dependent on AID and UNG. J Exp Med. 2005;202:561–568. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen HM, Ratnam S, Storb U. Targeting of the activation-induced cytosine deaminase is strongly influenced by the sequence and structure of the targeted DNA. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:10815–10821. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.24.10815-10821.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen HM, Storb U. Activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) can target both DNA strands when the DNA is supercoiled. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:12997–13002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404974101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen HM, Tanaka A, Bozek G, Nicolae D, Storb U. Somatic hypermutation and class switch recombination in Msh6(−/−)Ung(−/−) double-knockout mice. J Immunol. 2006;177(8):5386–5392. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.8.5386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen V, Kiledjian M. A view to a kill: structure of the RNA exosome. Cell. 2006;127:1093–1095. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinkura R, Tian M, Smith M, Chua K, Fujiwara Y, Alt FW. The influence of transcriptional orientation on endogenous switch region function. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:435–441. doi: 10.1038/ni918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohail A, Klapacz J, Samaranayake M, Ullah A, Bhagwat AS. Human activation-induced cytidine deaminase causes transcription-dependent, strand-biased C to U deaminations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:2990–2994. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staals RH, Bronkhorst AW, Schilders G, Slomovic S, Schuster G, Heck AJ, Raijmakers R, Pruijn GJ. Dis3-like 1: a novel exoribonuclease associated with the human exosome. EMBO J. 2010;29:2358–2367. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stillman BW, Gluzman Y. Replication and supercoiling of simian virus 40 DNA in cell extracts from human cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1985;5:2051–2060. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.8.2051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian M, Alt FW. Transcription-induced cleavage of immunoglobulin switch regions by nucleotide excision repair nucleases in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:24163–24172. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003343200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomecki R, Kristiansen MS, Lykke-Andersen S, Chlebowski A, Larsen KM, Szczesny RJ, Drazkowska K, Pastula A, Andersen JS, Stepien PP, et al. The human core exosome interacts with differentially localized processive RNases: hDIS3 and hDIS3L. EMBO J. 2010;29:2342–2357. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuong BQ, Lee M, Kabir S, Irimia C, Macchiarulo S, McKnight GS, Chaudhuri J. Specific recruitment of protein kinase A to the immunoglobulin locus regulates class-switch recombination. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:420–426. doi: 10.1038/ni.1708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Wuerffel R, Feldman S, Khamlichi AA, Kenter AL. S region sequence, RNA polymerase II, and histone modifications create chromatin accessibility during class switch recombination. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1817–1830. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuerffel RA, Du J, Thompson RJ, Kenter AL. Ig Sgamma3 DNA-specifc double strand breaks are induced in mitogen- activated B cells and are implicated in switch recombination. J Immunol. 1997;159:4139–4144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue K, Rada C, Neuberger MS. The in vivo pattern of AID targeting to immunoglobulin switch regions deduced from mutation spectra in msh2−/− ung−/− mice. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2085–2094. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang SY, Schatz DG. Targeting of AID-mediated sequence diversification by cis-acting determinants. Adv Immunol. 2007;94:109–125. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(06)94004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu K, Chedin F, Hsieh CL, Wilson TE, Lieber MR. R-loops at immunoglobulin class switch regions in the chromosomes of stimulated B cells. Nat Immunol. 2003a;4:442–451. doi: 10.1038/ni919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu K, Lieber MR. Nucleic acid structures and enzymes in the immunoglobulin class switch recombination mechanism. DNA Repair (Amst) 2003b;2:1163–1174. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2003.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarrin AA, Alt FW, Chaudhuri J, Stokes N, Kaushal D, Du Pasquier L, Tian M. An evolutionarily conserved target motif for immunoglobulin class-switch recombination. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:1275–1281. doi: 10.1038/ni1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.