Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the annual changes in prostate variables and style of surgical treatment of patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) over the past 12 years.

Materials and Methods

The subjects were 918 patients (January 1999-November 2010) who were treated by either open prostatectomy or transurethral resection of prostate (TURP). Every year, the performance ratio between open prostatectomy and TURP was evaluated. Before surgery, total and transitional zone volumes of the prostate were measured by transrectal ultrasonography (TRUS). After surgery, resection weight and residual volume of the prostate were measured by TRUS.

Results

From 2001 through 2010, the performance ratio of TURP increased greatly from 89% to 97%. During 1999 to 2010, the total volume of the prostate increased from 40.0 cc to 55.0 cc in the TURP group and from 74.1 cc to 116.7 cc in the open prostatectomy group. During 1999 to 2010, the mean resection volume of the TURP group increased from 2.3 cc to 20.1 cc. Also, the mean resection volume of the open prostatectomy group increased from 59.3 cc to 114.3 cc. During 1999 to 2003, the resection time of the TURP group decreased from 72.9 minutes to 43.2 minutes.

Conclusions

During 1999 through 2010, the performance ratio between open prostatectomy vs TURP was high for TURP. The total volume and resection volume of the prostate increased annually, and the resection time decreased annually.

Keywords: Prostatectomy, Prostatic hyperplasia, Transurethral resection of prostate

INTRODUCTION

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is the main reason for lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) due to urethral blockade. There are two kinds of treatments for patients with BPH: medical and surgical treatment. Whereas medical treatment using alpha-blockers or 5-alpha reductase inhibitors is the first-line treatment of BPH, in some ineffective cases, open prostatectomy or transurethral resection of prostate (TURP) has been mainly applied. Approximately 10% of patients with BPH require surgical treatment [1]. In some cases, surgery could be the first choice for treatment rather than medical therapy. Approximately 8% of subjects receiving medical therapy require subsequent surgical therapy [2]. Delay of surgical therapy due to medical therapy can cause progression of BPH and its symptoms.

Recently, non-open surgery, or TURP, has been more popularly used because of the lower mortality and shorter hospital stay than with open surgery. Development of equipment such as high-quality resectoscopes and fiberoptic and microlens systems and advances in the technology of TURP also contribute to a higher rate of TURP than open surgery [3]. The purpose of this article was to evaluate the annual changes in prostate variables and style of surgical treatment in patients with BPH over the past 12 years.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The subjects were 918 patients (January 1999-November 2010) who were treated by either open prostatectomy or TURP. For the preoperative evaluation, chest x-ray, intravenous pyelography, electrocardiography (ECG), urine analysis, urine culture, blood tests, and biochemistry tests were done. In patients who were more than 60 years of age, arterial blood gas analysis (ABGA) was performed. Also, all patients underwent transrectal ultrasonography (TRUS, B&K Medical, Herlev, Denmark), digital rectum examination (DRE), and serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) measurement. All patients were treated by the same surgeon in our hospital. A monopolar electric surgical unit and 24 Fr resectoscope (Karl Storz™, Tuttlingen, Germany) and a continuous irrigation system were used until 2003, and a 22 Fr resectoscope (Karl Storz™, Tuttlingen, Germany) since 2004. All patients underwent TURP with spinal or general anesthesia.

Every year, the performance ratio between open prostatectomy and TURP was evaluated. Before surgery, the total volume of the prostate was measured by TRUS. All patients underwent TRUS by residents (2 second-year residents per year, 22 residents/12 years) in our urology department. In addition, before both TURP and open prostatectomy, the peak flow rate (PFR; Qmax), residual volume, and International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) were evaluated, and just after removal of the Foley catheter in both surgeries, Qmax, residual volume, and IPSS were measured. Resection volume was measured as follows. After TURP, resected prostate tissue was obtained and measured by use of a weighing machine. Resection time was measured as the duration from start to end of cutting the prostate. Postoperative complications were comparatively analyzed. Since 2006, the residual volume and resection time were measured. Follow-up data of performance ratio, prostate volume, resection volume, resection time, IPSS, and complications were analyzed by using SPSS ver. 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Comparisons of clinical characteristics and parameters were made by using the paired t-test and chi-square test. Values of p<0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

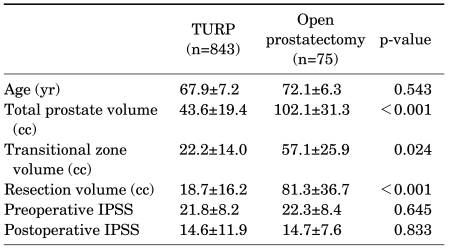

The mean age of the 843 patients who underwent TURP was 67.9±7.2 years (range, 46-88 years) and the mean age of the 75 patients who underwent open prostatectomy was 72.1±6.3 years (range, 58-83 years). The mean total volume of TURP was 43.6±19.4 cc (range, 14-98 cc) and that for open prostatectomy was 102.1±31.3 cc (range, 52-213 cc). The mean weight of the resected volume was 18.7±16.2 cc (range, 2-54 cc) in the TURP group and 81.3±36.7 cc (range, 21-140 cc) in the open prostatectomy group. In the TURP group, the mean preoperative IPSS score was 21.8±8.2 and the mean postoperative IPSS score was 14.6±11.9. In the open prostatectomy group, the mean preoperative IPSS score was 22.3±8.4 and the mean postoperative IPSS score was 14.7±7.6. Between the TURP and open prostatectomy groups, total prostate volume, transitional zone volume, and resection volume were significantly different (p<0.001, p=0.024, p<0.001, respectively) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Comparisons between the TURP group and the open prostatectomy group

TURP: transurethral resection of the prostate, IPSS: International Prostate Symptom Score

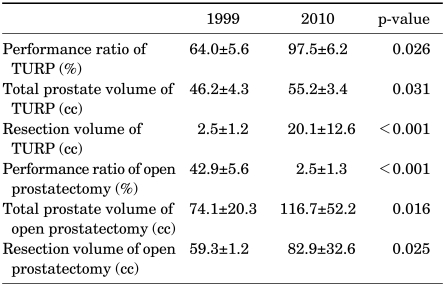

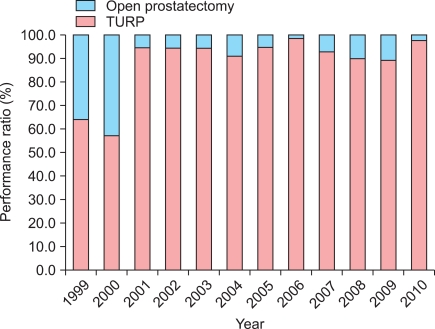

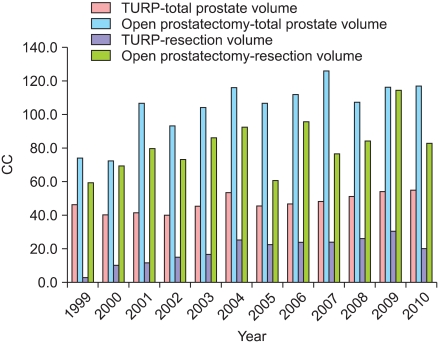

The performance ratio between open prostatectomy and TURP treatment was 64% vs 36% in 1999 and 3% vs 97% in 2010. In 2001 the performance ratio of TURP started to increase over open prostatectomy as 94.5% vs 5.5%, and during 2001 through 2010, the performance ratio of TURP greatly increased (Table 2, Fig. 1). From 1999 to 2010, the total prostate volume of the TURP group increased from 40.0 cc to 55.0 cc, which was a significant difference (p=0.031) (Table 2, Fig. 2). From 1999 to 2010, the total prostate volume also showed an increase from 74.1 cc to 116.7 cc in the open prostatectomy group, which was a significant difference (p=0.016) (Table 2, Fig. 2). From 1999 to 2010, the mean resection volume of the TURP group increased from 2.3 cc to 20.1 cc, which was a significant difference (p<0.001) (Table 2, Fig. 2). Also, the mean resection volume of the open prostatectomy group increased from 59.3 cc to 114.3 cc, which was a significant difference (p=0.025) (Table 2, Fig. 2). In the beginning of TURP, the surgeon preferred to perform open prostatectomy rather than TURP, because the operator was not as experienced with TURP as with open prostatectomy.

TABLE 2.

Comparisons between 1999 vs. 2010 in the TURP and open prostatectomy groups

TURP: transurethral resection of the prostate

FIG. 1.

The performance ratio of transurethral resection of the prostate and open prostatectomy. TURP: transurethral resection of prostate.

FIG. 2.

The total prostate volume and resection volume in the transurethral resection of the prostate group and open prostatectomy group. TURP: transurethral resection of prostate.

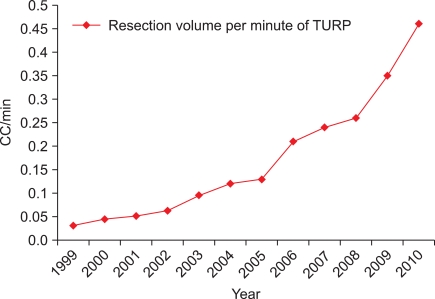

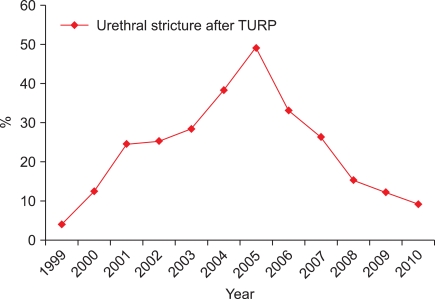

From 2006 to 2010, the residual volume of the prostate after TURP decreased from 29.3 cc to 24.7 cc. From 1999 to 2010 the resection time of the TURP group decreased from 72.9 minutes to 43.2 minutes, which was significant difference (p=0.031) (Table 2). Also, the resection volume per minute of TURP increased from 0.03 cc to 0.46 cc (Fig. 3). There was no significant difference between postoperative Qmax and postoperative IPSS in 1999 to 2010. Urethral dilatation and internal urethrotomy to treat the urethral stricture gradually increased between 1999 and 2005 such as from 4.0% to 49.1%. Between 2005 and 2010, urethral strictures decreased from 49.1% to 9.2% (Fig. 4). There was no significant difference between the frequency of cystocatheterization and reoperation due to postoperative bleeding.

FIG. 3.

The resection volume per minute of TURP. TURP: transurethral resection of prostate.

FIG. 4.

Occurrence of urethral strictures after TURP. TURP: transurethral resection of prostate.

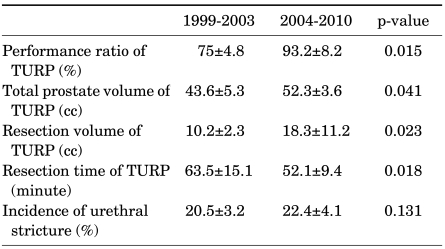

Also, the performance ratio, total prostate volume, and resection volume were higher and resection time was lower in the TURP group who underwent the procedure with the 22 Fr resectoscope from 2004 to 2010. Regardless of resectoscope size, the performance ratio, total prostate volume, and resection volume increased annually and resection time decreased annually. Also, the incidence of urethral stricture after TURP was not significantly different in either group (p=0.131) (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Comparison between 24 Fr resectoscope (1999-2003) vs 22 Fr resectoscope (2004-2010)

TURP: transurethral resection of the prostate

DISCUSSION

BPH, the most common benign neoplasm in men, is clinically followed by LUTS. These variable symptoms range from incomplete emptying, nocturia, weak stream, to frequency and can potentially advance to urge incontinence, urinary retention, urinary tract infection (UTI), bladder calculi, or renal failure. LUTS impede habitual activities and reduce quality of life [4,5].

In order to relieve bladder outlet obstruction, the transurethral operation was started by Pare in the 16th century [6]. In 1926, Stearns developed the tungsten loop, which could be used for the resection, and the transurethral resection procedure widely spread [7]. The indications for TUR are as follows: complete urinary obstruction with prostate blockade syndrome, urinary obstruction symptoms, recurrent bleeding, and recurrent UTI [8]. With the increase in the population of old aged persons and improved medical service, the number of BPH patients has increased. Among them are patients in their 60s and 70s who need to be operated on because they have diseases such as lung disease, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension [9]. TUR can be conducted in persons who can live longer than 6 months with other internal organ tumors. The selection of a treatment method can be accomplished by considering the patient's physical condition, accompanying diseases, the size and shape of the prostate, expected complications, and surgeon's technique.

The treatment methods of BPH are classified as medical and surgical treatments. The surgical treatments can be classified as open prostatectomy and TURP treatment in general. TURP still represents the surgical treatment of choice for prostate glands up to 100 ml, whereas open prostatectomy is indicated for prostate glands larger than 80 to 100 ml [10,11]. Generally, in cases of much more than 100 g of prostate volume, open prostatectomy will be recommended [12]. However, Kwak et al reported on a comparison between TURP and open prostatectomy for patients with large BPH, and there were no significant differences in effectiveness or safety for 5 years. Even for patients with BPH with a high volume, TURP is an effective operation that can replace open prostatectomy [13]. When selecting the proper treatment methods for BPH, not only the many factors already listed previously but also the anticipated complications must be seriously considered [12]. Usually, TURP is conducted more often than open prostatectomy because the former is not only less invasive but also is associated with less morbidity. TURP is the gold standard for the surgical management of symptomatic BPH and has proven to be a highly efficient technique associated with a low mortality rate [14-16]. However, after TURP, several complications such as incontinence, stricture of the urethra, and retrograde ejaculation may develop [7]. In our data, urethral dilatation and internal urethrotomy to treat the urethral stricture gradually increased between 1999 and 2005 from 4.0% to 49.1%. Between 2005 and 2010, however, the rate of urethral strictures decreased from 49.1% to 9.2%. From 2006, we started to maintain the temperature of the urethra with warm irrigation solution during transurethral resection of the prostate. This decreased the incidence of urethral stricture compared with the room-temperature irrigation solution group. We observed that a lower temperature might be another cause of urethral stricture after TURP. The mechanical damage in the urethral mucosa leads to leakage of urine, resulting in inflammation and scar formation [17]. Resectoscope size, however, did not have a significant relationship with the incidence of urethral stricture.

Developments in anesthesia, for example, the addition of opioids to local anesthetics, have reduced the side effects of spinal anesthesia in urologic surgery [18]. Owning to new techniques, the operation time has been reduced and complications have declined. Because of the high quality of the resectoscope, and the fiberoptic and microlens systems, and strict adherence to the practice of performing TURP, the results of the present study also demonstrate that the safety of TURP is improved by decreasing intraoperative blood loss, which significantly decreases the need for blood transfusion [19]. For these reasons, TURP has been widely performed rather than open prostatectomy during the past 12 years in urology. This is the trend in the treatment of patients with BPH.

In general, surgeons start an operation with an easy case, which is followed by difficult ones. The learning curve migrates from small prostate cases to large prostate cases. In our data, prostate volume was larger during the latter period than in the early period because of improved techniques of TURP. In addition, TURP efficiency increased in proportion to prostate weight, and this study showed a continuous increase in resection volume per minute of TURP.

The introduction of medical therapy for symptomatic BPH resulted in a delay in the need for surgical intervention, such that a man who eventually required TURP inevitably presents when older, with a worsening comorbid status, and more progressive disease, thus resulting in poorer outcomes and more frequent postoperative complications [20]. Also, delay in surgical therapy results in the progression of BPH. This can lead to more extensive and complicated resection. Patients treated by TURP show an increase in not only prostate volume but also resected prostate volume, which may be because the surgery was delayed by treatment with alpha-1 blockers or 5-alpha reductase inhibitors. The volume of the prostate removed by open prostatectomy also increased, which may also have been caused by the delayed surgical effect by medication [20], although that should be followed up for a longer time.

CONCLUSIONS

From 1999 through 2010, the performance ratio between open prostatectomy and TURP was higher for TURP. The total and resection volumes of the prostate increased annually. The increases in prostate volume and resected prostate volume may have occurred because the surgery was delayed by the improvement in symptoms by medications. Also, the resection time and postoperative complications decreased annually as the result of improvements in surgical techniques and instruments.

Footnotes

The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Crowley AR, Horowitz M, Chan E, Macchia RJ. Transurethral resection of the prostate versus open prostatectomy: long-term mortality comparison. J Urol. 1995;153:695–697. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199503000-00041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saigal CS, Movassghi M, Pace J, Joyce G. Economic evaluation of treatment strategies for benign prostatic hyperplasia--is medical therapy more costly in the long run? J Urol. 2007;177:1463–1467. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.11.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reich O, Gratzke C, Bachmann A, Seitz M, Schlenker B, Hermanek P, et al. Morbidity, mortality and early outcome of transurethral resection of the prostate: a prospective multicenter evaluation of 10,654 patients. J Urol. 2008;180:246–249. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.03.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barry MJ, Fowler FJ, Jr, Bin L, Pitts JC, 3rd, Harris CJ, Mulley AG., Jr The natural history of patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia as diagnosed by North American urologists. J Urol. 1997;157:10–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Girman CJ, Epstein RS, Jacobsen SJ, Guess HA, Panser LA, Oesterling JE, et al. Natural history of prostatism: impact of urinary symptoms on quality of life in 2115 randomly selected community men. Urology. 1994;44:825–831. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(94)80165-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Habib NA, Luck RJ. Results of transurethral resection of the benign prostate. Br J Surg. 1983;70:218–219. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800700411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.John MF. Minimally invasive and endoscopic management of benign prostatic hyperplasia. In: Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Novick AC, Parrtin AW, Peters CA, editors. Campbell-Walsh urology. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2007. pp. 2803–2844. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Misop H, Alan WP. Retropubic and suprapubic open prostatectomy. In: Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Novick AC, Parrtin AW, Peters CA, editors. Campbell-Walsh urology. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2007. pp. 2845–2853. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim HH, Kwak C, Seo SI, Chung H, Lee ES, Lee CW. The effects and complications of transurethral resection for benign prostatic hyperplasia: results of long-term follow-up. Korean J Urol. 1996;37:268–280. [Google Scholar]

- 10.de la Rosette JJ, Alivizatos G, Madersbacher S, Perachino M, Thomas D, Desgrandchamps F, et al. EAU Guidelines on benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) Eur Urol. 2001;40:256–263. doi: 10.1159/000049784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roehrborn CG, Bartsch G, Kirby R, Andriole G, Boyle P, de la Rosette J, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia: a comparative, international overview. Urology. 2001;58:642–650. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(01)01402-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang HS, Choi NG. The results of benign hyperplasia treatment by transurethral resection, open prostatectomy, and TUMT (transurethral microwave thermotherapy) Korean J Urol. 1994;35:370–375. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kwak DY, Chang HS, Park CH, Kim CI. Long-term results of transurethral resection of the prostate for large benign prostatic hyperplasia: a comparative study with open prostatectomy. Korean J Urol. 2008;49:31–36. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mebust WK, Holtgrewe HL, Cockett AT, Peters PC. Transurethral prostatectomy: immediate and postoperative complications. A cooperative study of 13 participating institutions evaluating 3,885 patients. J Urol. 1989;141:243–247. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)40731-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horninger W, Unterlechner H, Strasser H, Bartsch G. Transurethral prostatectomy: mortality and morbidity. Prostate. 1996;28:195–200. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0045(199603)28:3<195::AID-PROS6>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chacko KN, Donovan JL, Abrams P, Peters TJ, Brookes ST, Thorpe AC, et al. Transurethral prostatic resection or laser therapy for men with acute urinary retention: the ClasP randomized trial. J Urol. 2001;166:166–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park JK, Lee SK, Han SH, Kim SD, Choi KS, Kim MK. Is warm temperature necessary to prevent urethral stricture in combined transurethral resection and vaporization of prostate? Urology. 2009;74:125–129. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.12.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim J, Moon YE, Hong S, Jeon JP, Chang HW, Kim SJ, et al. Comparison of clinical effect of intrathecally administered fentanyl for elderly patients undergoing urologic surgery. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2008;55:579–584. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berger AP, Wirtenberger W, Bektic J, Steiner H, Spranger R, Bartsch G, et al. Safer transurethral resection of the prostate: coagulating intermittent cutting reduces hemostatic complications. J Urol. 2004;171:289–291. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000098925.76817.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Borth CS, Beiko DT, Nickel JC. Impact of medical therapy on transurethral resection of the prostate: a decade of change. Urology. 2001;57:1082–1085. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(01)01018-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]