Abstract

CONTEXT:

The relative effectiveness of interventions to improve parental communication with adolescents about sex is not known.

OBJECTIVE:

To compare the effectiveness and methodologic quality of interventions for improving parental communication with adolescents about sex.

METHODS:

We searched 6 databases: OVID/Medline, PsychInfo, ERIC, Cochrane Review, Communication and Mass Media, and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature. We included studies published between 1980 and July 2010 in peer-reviewed English-language journals that targeted US parents of adolescents aged 11 to 18 years, used an experimental or quasi-experimental design, included a control group, and had a pretest/posttest design. We abstracted data on multiple communication outcomes defined by the integrative conceptual model (communication frequency, content, skills, intentions, self-efficacy, perceived environmental barriers/facilitators, perceived social norms, attitudes, outcome expectations, knowledge, and beliefs). Methodologic quality was assessed using the 11-item methodologic quality score.

RESULTS:

Twelve studies met inclusion criteria. Compared with controls, parents who participated in these interventions experienced improvements in multiple communication domains including the frequency, quality, intentions, comfort, and self-efficacy for communicating. We noted no effects on parental attitudes toward communicating or the outcomes they expected to occur as a result of communicating. Four studies were of high quality, 7 were of medium quality, and 1 was of lower quality.

CONCLUSIONS:

Our review was limited by the lack of standardized measures for assessing parental communication. Still, interventions for improving parent-adolescent sex communication are well designed and have some targeted effects. Wider dissemination could augment efforts by schools, clinicians, and health educators.

Keywords: parent, adolescent, communication, sex, systematic review

Adolescent sexual behavior is a normal developmental milestone. However, the social and public health consequences of adolescent sexual activity are tremendous. Of the 18 million sexually transmitted infections diagnosed in the United States each year,1,2 half occur in adolescents.3–5 Pregnancy affects 750 000 adolescents annually, 80% of which are unintended.6 Despite recent declines in the number of sexually active adolescents, engagement in risky sexual behaviors remains problematic.7

Adolescents who recall a parent talking with them about sex are more likely to report delaying sexual initiation8–10 and increasing condom8,11,12 and contraceptive11,13 use. In light of these findings, interventions for improving parental communication about sex have been developed.14 Although dozens of interventions exist, they have not been rigorously compared. We sought to examine whether interventions for improving parental communication with adolescents about sex are effective at strengthening multiple communication domains and to assess the methodologic quality of these interventions.

METHODS

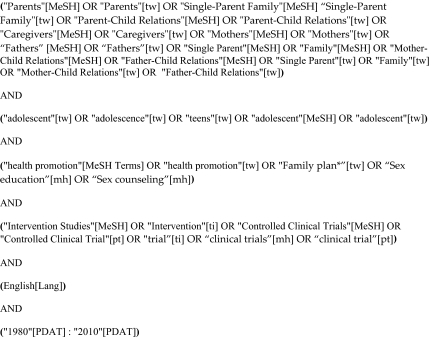

With the assistance of health science librarians, 6 databases were searched: OVID/Medline (1980 to July 2010), PsychInfo (1980 to July 2010), ERIC (1980 to July 2010), Cochrane Review (until July 2010), Communication and Mass Media (1980 to July 2010), and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (1982 to July 2010). We used terms for parent (eg, parent, caregiver), parenting (eg, mother-child relations, father-child relations), communication (eg, communication, health promotion), sex (eg, sex education, sex counseling), and experimental design (eg, intervention studies, pilot projects, clinical trials) along with Boolean connectors (ie, and, or). To identify additional articles that met our inclusion criteria, we hand-searched the reference list of each article on parent-adolescent communication, including review articles (see Fig 1 for an example of 1 of our search strategies).

FIGURE 1.

Sample search strategy for OVID/Medline.

Inclusion Criteria

We included studies that were published between January 1980 and July 2010; were published in peer-reviewed, English-language journals; empirically measured the effectiveness of interventions for improving parental communication with adolescents about sex; targeted parents of adolescents aged 11 to 18 years in the United States; and used an experimental or quasi-experimental study design that included a control group and a pretest/posttest design. Studies could target mothers, fathers, or both. Studies could target communication by parents with daughters, sons, or adolescents of both genders.

Data Abstraction

We initially searched each database to create a list of potentially eligible articles on the basis of title review. If there was any question of the article's relevance based on the title, we reviewed the abstract. If an abstract was not available or the articles' eligibility remained questionable after reading the abstract, we read the full text. For instances in which a single intervention was described in multiple published articles, we counted the interventions only once. The paper-based abstract and article review forms were pilot-tested and revised 3 times before the final forms were selected. Each pilot test was performed in a new electronic database. After the third pilot test, the forms functioned well for data abstraction from the remaining databases. We double-entered the abstracted data into a structured Excel database (Microsoft, Redmond, WA). Our review protocol is available on request.

Study Characteristics

Abstracted information included the interventions' inclusion and exclusion criteria, when the intervention was conducted, recruitment strategies, geographic setting, intervention- and control-group characteristics, study design (eg, number of intervention sessions, intervention site and content), data-collection methods, primary outcomes, and attrition rate.

Only findings that resulted from statistical tests of hypotheses assessing relationships between the intervention (exposure) and its effects on parental communication (outcome) were extracted. For cases in which multiple postintervention assessments (eg, immediate postintervention, 3-month, 6-month) were made, we abstracted outcome data for each assessment time point. When insufficient data were presented in the published article to determine outcome results, we contacted the study authors to obtain the necessary data. We contacted the authors of 2 studies to obtain the means and SDs for the communication outcome measures they reported to permit comparison with data reported from other included studies. These data also would have aided in calculating effect sizes. In both instances, we reached the study authors but were unable to obtain the necessary data. However, we did not exclude any data. We report study results as they were cited in each author's original article.

Communication Outcomes

We abstracted data on multiple aspects of communication. Our selection of outcomes was guided by the integrated conceptual model (ICM).15,16 This model had previously been used to examine parental communication about sex. Developed by a National Institutes of Health consensus panel of health behavior experts, the ICM posits that 3 factors are necessary and sufficient for parent-adolescent communication to occur: skills; intentions; and the absence of environmental barriers or presence of facilitators of the behavior. Four factors influence intentions: self-efficacy; perceived social norms; attitudes toward the behavior; and outcomes expected to occur as a result of engaging in the target behavior. Finally, 2 factors influence the previous 4: knowledge and beliefs about the behavior. We acknowledge that systematic reviews usually select only 1 outcome variable to examine. We included multiple domains of parental communication, because we recognized that a strict approach would severely limit the number of studies that would meet our inclusion criteria and, more importantly, would provide a less robust description of interventions' effect on parent-adolescent communication. When available, we included outcomes reported by parents and adolescents, because their perspectives regarding whether and how discussions about sex have occurred are often incongruent.17–20

Each study's test of the relationship between intervention participation and a communication domain was counted as a separate finding. Thus, a single study could contribute multiple findings (eg, communication frequency, quality, self-efficacy). Furthermore, when unadjusted and controlled analyses were reported in the same study, only findings from the controlled analyses were abstracted, because they provide a more precise measure of effect. Two reviewers independently abstracted all data and then met to discuss and compare their findings. The interrater reliability for data abstraction was 0.97.

Data Synthesis

Ideally, each intervention's effect on a given communication domain would have been converted to an effect size that provides a standardized measure of the magnitude of each intervention's effect, which would have allowed us to perform a meta-analysis and calculate pooled effect sizes for each communication domain. However, this was not possible because of variability in how communication domains were defined and measured across the studies.

Methodologic Quality

We systematically recorded information regarding each intervention's methodologic characteristics. We used a previously described and validated methodologic quality scoring (MQS) system.21,22 Scores on the 11-item MQS ranged from 0 to 20. Scores were grouped to denote lower- (score of 0–6), medium- (score of 7–14), and higher- (score ≥ 15) quality studies. The data were again abstracted by 2 independent coders, and the interrater reliability was 0.90.

RESULTS

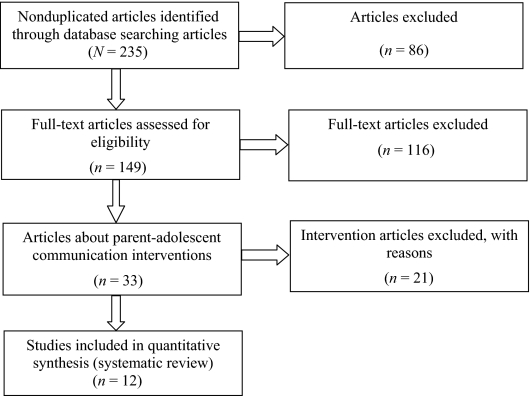

Thirty-three parent-adolescent communication interventions were identified; 12 met inclusion criteria. Fig 2 shows the flow diagram for study inclusion and exclusion. Twenty-one studies were excluded. Several studies met more than 1 exclusion criteria. Four studies were excluded because they lacked a control group23–26; 9 did not report parent-adolescent communication outcome data27–35; 1 did not report outcome data for parent participants, only for adolescent participants36; 3 included parents of younger children but did not stratify outcome data on the basis of the age of participating parents' children25,26,37; 1 only included parents of preschool-aged children38; parents participated in multiple interventions simultaneously in 1 study, which made it impossible to determine the individual effects of the parent-adolescent communication program39; and 4 included non-US samples.40–43

FIGURE 2.

Systematic review flow diagram.

Study Characteristics

Of the 12 included studies, 8 were published between 2000 and 2008.44–51 The studies were published in 11 journals that represent a variety of disciplinary fields including psychology,46,50,52 family relations,44,53,54 adolescent health,47,55 general medicine,51 public health,48 nursing,56 and sexual health.49

Overview of Communication Outcomes

Across all 12 studies, we identified 2 measures of actual communication: the frequency of parent-adolescent discussions about sex-related topics and the content of those discussions. Content of communication was assessed by using 3 measures: the number of sexuality-related topics ever discussed, as well as new and repeated topics discussed between follow-up periods. Specific measures regarding skills, intentions, self-efficacy (or comfort), attitudes, and outcomes expectations were identified. No studies assessed communication knowledge, environmental barriers/facilitators of communication, or perceived social norms regarding communication. Although we also found no measures that were explicitly titled “beliefs about communicating,” items contained in measures of perceived quality of communication seemed to tap parental beliefs about communicating. Hence, we review outcome data on quality measures in “Quality (ie, Beliefs) of Communication.”

Studies varied widely in the number of communication domains assessed. The 2 most common domains measured were frequency and content of communication. Eight studies assessed communication outcomes by using both parent and adolescent reports. Every intervention used different measures to assess each of the communication domains. Most of these measures were developed by the investigators for their individual study.

Intervention Characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of each of the 12 interventions included in this review. Six interventions were conducted in the South,47,48,50,54–56 3 in the West,46,51,53 2 in the Midwest,44,52 and 1 in the Northeast.49 Only 2 targeted rural populations.50,53 We assigned each intervention an urban/rural designation on the basis of the authors' report of intervention location and the US Census definition of urban/rural areas.57 Nine studies were conducted as randomized controlled trials, and the remainder used quasi-experimental designs.

TABLE 1.

Intervention Characteristics: Reviewed Studies and Their Methods and Findings

| Intervention | Parent Participants | Racial Composition (%) | Intervention Year(s) | Sample Size, Parents, n | Sample Size, Adolescents, n | % Mothers | Region | Urbanicity | Study Design | Sessions | Site | Theoretic Framework | Attrition, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Keepin' it REAL | Mothers of 11- to 14-y-olds | Black (97%); other (3%) | 1996–2001 | I: 160 (LSK); I: 154 (SCT); C: 156 | I: 187 (LSK); I: 194 (SCT); C: 201 | 100 | South | Urban | RCT | n = 7 | CBO | PBT, SCT | I: 7 (SCT); I: 9 (LSK); C: 13 |

| Facts and Feelings | Parents of 12- to 14-y-olds | White (95%); other (5%) | 1989–1994 | I: 126 families (full); I: 132 families (short); C: 290 families | NA | West | Urban and rural | RCT | n = 6 | Home | None | I: 4.7; C: 10 | |

| Parents Matter! | Parents of 9- to 12-y-olds | Black (100%) | 2001–2004 | I: 378 (full); I: 371 (short); C: 366 | I: 378 (full); I: 371 (short); C: 366 | 88 | South | Urban | RCT | n = 5 | School, CBO | SLT, PBT, TRA | 26–30 |

| Strong African American Families (SAAF) | Mothers of 11-y-olds | Black (100%) | 1999–present | I: 172 (families); C: 150 (families) | 100 | South | Rural | RCT | n = 7 | CBO | Authors' model | I: 4; C: 3 | |

| REAL Men | Fathers of 11- to 14-y-old boys | Black (97%); other (3%) | 1998–2005 | I: 141; C: 132 | I: 141; C: 132 | NA | South | Urban | RCT | n = 7 | CBO | SCT | 20 |

| Talking Parents, Healthy Teens | Parents of 6th- to 10th-graders | White (47%); black (17%); Hispanic (16%); Asian (14%); other (5%) | 2002–2005 | I: 269; C: 266 | I: 315; C: 312 | 72 | West | NA | RCT | n = 8 | Worksite | ICM | P: 6; A: 4 |

| Saving Sex for Later | Parents of 5th- to 6th-graders | Black (64%); Hispanic (28%); other (8%) | 2003–2005 | I: 345; C: 335 | I: 362; C: 348 | 92 | Northeast | Urban | RCT | NA | Home | SDT, DOI, TPB | NA |

| Huston Intervention | Parents of 6th- to 8th-graders | White (63%); Hispanic (31%); Asian (6%) | 1988 | I: 24; C: 8 | NA | 84 | South | Urban | NRT | n = 4 | School | None | I: 49; C: 53 |

| CHAMP | Parents of 10- to 14-y-olds | Black (100%) | 1996–2000 (first 2 waves) | I: 201; C: 264 | 59 | Midwest | Urban | NRT | n = 12 | Churches, schools, CBO | Authors' model | NA | |

| Lefkowitz intervention | Mothers of 11- to 15-y-olds | White (50%); black (15%); Hispanic (18%); Asian (10%); mixed (6%) | 1995–1997 | I: 20; C: 20 | I: 20; C: 20 | 100 | West | Urban | RCT | n = 2 | NA | None | I: 13; C: 26 |

| Families in Touch-Understanding AIDS | Parents of 8th-graders | White (34%); black (33%); Hispanic (20%); Asian (5%); other (8%) | 1998 | 94a | 93a | NA | Midwest | Urban | RCT | 6 d | Home | None | NA |

| Parent, Young Adolescent Family Life Education Project (PYAFLE) | Parents of 10- to 14-y-olds | White (77%); black (16%); other (7%) | 1979–1981 | I: 162; C: 23 | I: 191; C: 24 | 79 | South | Urban | NRT | n = 8 | Church, school, CBO | None | 25 |

I indicates intervention; C, control; LSK, life skills training; SCT, social cognitive theory; RCT, randomized controlled trial; CBO, community-based organization; PBT, problem behavior theory; NA, not available; SLT, social learning theory; TRA, theory of reasoned action; ICM, integrative conceptual model; SDT, social development theory; DOI, diffusion of innovation theory; TPB, theory of planned behavior; NRT, nonrandomized trial; P, Parent; A, Adolescent.

Unclear how many parents were in the intervention group and how many were in the control group.

Although the studies targeted parents of adolescents in different age ranges, all of them included parents of middle school students aged 11 to 14. Only 2 included high school students.46,51 One-third of the studies specifically targeted fathers48 or mothers,46,50,56 and the remainder included predominantly mothers despite both parents being eligible. Participants in 3 studies consisted mostly of white respondents,53–55 6 included predominantly black respondents,44,45,47–50 and the remainder included samples with more than 2 racial/ethnic groups.46,51,52

Intervention Effectiveness

In general, authors of the studies reported that their interventions increased parental reports of parent-adolescent communication regardless of the communication domain assessed (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Intervention Outcomes for Each Communication Domain

| Communication Domain | Intervention | Description of Outcome Measure | Intervention-Group Outcomesc | Control-Group Outcomesc | Direction of Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Parents Mattera | 9-item scale; 2-point Likert scale (eg, never, lots of times); higher scores denote more frequent communication | No pre/post outcome data were presented for parents or adolescents, only differences in mean change between each of the 3 intervention arms for each assessment period | See right | Parents and adolescents in the enhanced intervention (2 sessions) reported increased communication compared to single-session intervention or the control group; magnitude of change between pre- and immediate postintervention assessments was reportedly greater among adolescents than parents; at subsequent follow-up postintervention assessments; magnitude of change was reportedly greater among parents than adolescents, although the magnitude of the difference in means decreased over time |

| CHAMPb | Measure not described or referenced; lower scores denote more frequent communication | Pre: 13.5 (5.0); post: 11.8 (5.2); t scored: −0.30 (NS) | Pre: NR; post: 14.1 (4.6); t score: −6.9 | Parents in the intervention group reported increased frequency of communication relative to the control group | |

| Hustonb | Assess No. of times 11 sexual topics were discussed; 6 response options (ie, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, >5 times); responses summed yielding frequency score; compared difference in frequency score pre- and postintervention; higher scores denote more frequent communication | Pre: NR; post: 10.9 (7.3)f | Pre: NR; post: −2.50 (5.86)f | Parents in the intervention group reported increased frequency of communication relative to the control group | |

| Lefkowitza | Assessment of discussions regarding 10 sexuality- and AIDS-related topics during previous 2 wk; dichotomous response (yes/no); reported mean No. of topics discussed | Parents: pre: 0.5 (0.9); post: 0.4 (1.1) | Parents: pre: 0.3 (0.6); post: 0.4 (1.0) | No difference reported for parents or adolescents | |

| Adolescents: pre: 0.5 (1.1); post: 0.9 (2.3) | Adolescents: pre: 0.3 (0.5); post: 0.5 (0.8) | ||||

| Facts and Feelingsa | Parents: assessed frequency of discussion of 14 topics in previous 3 mo; 4-point Likert scale (eg, no talk, >4 times); higher scores denote more frequent communication | Exact point estimates for pre- and postintervention (3- and 12- mo) outcomes not presented | See right | Parents: parents in the video-only and the video+newsletter groups showed a larger increase in the frequency of communication than those in the control group; half the gain in communication frequency was lost in both intervention groups by 12 mo; control-group parents experienced a gradual increase in communication | |

| Adolescents: assessed frequency of discussion of 15 topics in previous 3 mo; 4-point Likert scale (eg, no talk, >4 times); higher scores denote more frequent communication | Adolescents: adolescents whose parents were in either intervention group showed a larger increase in the frequency of communication than those in the control group; adolescents whose parents were in the video+newsletter group showed a larger increase than those in the video-only group; at 12 mo, all 3 groups returned to their baseline frequency of communication | ||||

| Families in Toucha | The modified Fisher scale measured parent-child communication about sex by using a 8-item scale; 4-point Likert scale; scores ranged from 0-32; higher scores denote more frequent communication | Parent: MPre: NR MPost: NR Pre(Fstatistic): NR Post(Fstatistic): NR 2 wk(F1,52) = 5.33 (.05) |

Parents: pre: NR; 2 wk: NR | Parents in the intervention group reported increased frequency of communication relative to control group | |

| Adolescent: MPre: NR MPost: NR Pre(F1,143) = 6.17 (.01) (mother); F1,138 = 4.68 (<.05) (father) Post(Fstatistic): NR 2 wk(Fstatistic): NR |

Adolescents: pre: NR; 2 wk: NR | ||||

| Families in Toucha | Discussions about AIDS reported by using 1 of the items from the Fisher scale (described above); higher scores denote more frequent communication | Parent: MPre: NR MPost: 2.53 Pre(Fstatistic): NR Post(F1,52): 4.36 (<.05) M2 wk(F1,52) = 5.86 (<.05) |

Parents: pre: NR; 2 wk: see F statistic (left) | Parents in the intervention group reported speaking with their adolescent more about AIDS compared to the control group | |

| Adolescent: MPre: NR MPost: NR Pre(F1,143) = 5.05 (<.05) (mother); F1,138 = 4.82 (<.05) (father) Post(Fstatistic): NR 2 wk(Fstatistic): NR |

Adolescents: pre: see F statistics (left); 2 wk: 1.85 | ||||

| Ever discussed | Talking Parentsa | Parents: assessed whether ever discussed 24 sex-related topics at baseline and summed the responses; at each postintervention assessment, calculated the No. of new topics discussed between visits and the No. of repeated topics | Parents: pre: 8.9 (5.5); 1 wk (No. of new topics): 4.0 (NR); 3 mo (No. of new topics): NR; 9 mo (No. of new topics): NR; 1 wk (repeat topics): 6.4 (NR); 3 mo (repeat topics): NR; 9 mo (repeat topics): NR | Parents: pre NR; 1 wk (No. of new topics): 0.8 (NR); 3 mo (No. of new topics): NR; 9 mo (No. of new topics): NR; 1 wk (repeat topics): 3.7 (NR); 3 mo (repeat topics): NR; 9 mo (repeat topics): NR | The mean No. of new topics parents and adolescents reportedly discussed between baseline and the immediate postintervention assessment increased; the magnitude of the mean difference in the No. of new topics reportedly discussed by parents and adolescents in the intervention and control group was the same at 3 and 9 mo as at 1 wk after the intervention; the difference in the mean No. of repeated topics reported by parents and adolescents increased significantly at 3 and 9 mo |

| Adolescents: assessed whether ever discussed 22 sex-related topics at baseline and summed the responses; at each postintervention assessment, calculated the No. of new topics discussed between visits and the No. of repeated topics | Adolescents: pre: 7.2 (5.3); 1 wk (No. of new topics): 3.3 (NR); 3 mo (No. of new topics): NR; 9 mo (No. of new topics): NR; 1 wk (repeat topics): 4.5 (NR); 3 mo (repeat topics): NR; 9 mo (repeat topics): NR | Adolescents: pre: NR; 1 wk (No. of new topics): 1.4 (NR); 3 mo (No. of new topics): NR; 9 mo (No. of new topics): NR; 1 wk (repeat topics): 3.3 (NR); 3 mo (repeat topics): NR; 9 mo (repeat topics): NR | |||

| Lefkowitza | One item assessed whether ever communicated about AIDS; 5-point Likert scale (eg, not at all, a lot) | Exact point estimates for pretest or postintervention outcomes not presented | See right | No increase in communication about AIDS reported by mothers or adolescents | |

| Lefkowitza | One item assessed whether ever communicated about sexuality; 5-point Likert scale (eg, not at all, a lot) | Exact point estimates for pretest or postintervention outcomes not presented | See right | No increase in communication about sexuality reported by mothers or adolescents | |

| Lefkowitza | One item assessed whether ever communicated about birth control; 5-point Likert scale (eg, not at all, a lot) | Parents: pre: NR; post: NR | Parents: pre: NR; post: NR | Increased communication about birth control reported among intervention adolescents but not mothers | |

| Adolescents: pre: 1.5 (1.0); post: 2.2 (1.4) | Adolescents: pre: 1.7 (1.1); post: 1.8 (1.3) | ||||

| REAL Mena | Fathers: assessed whether 16 topics had ever been discussed between fathers and sons; 3 response options (eg, not discussed, discussed a lot); responses summed to yield a summary score that ranged from 0 to 48 | Parents: pre: NR; 3 mo: 22.60 (14.22); 6 mo: 22.98 (13.97); 12 mo: 23.33 (14.37) | Parents: pre: NR; 3 mo: 18.29 (15.89); 6 mo: 20.38 (16.01); 12 mo: 19.77 (15.27) | Fathers: intervention fathers reported having ever discussed more topics than control-group fathers at 3 and 12 mo but not at the 6-mo postintervention assessment | |

| Adolescent sons: assessed whether 13 topics had ever been discussed; 3 response options (eg, not discussed, discussed a lot); responses summed to yield a summary score that ranged from 0 to 39 | Adolescents: pre: NR; 3 mo: 23.19 (12.57); 6 mo: 22.73 (13.91); 12 mo: 23.63 (12.50) | Adolescents: pre: NR; 3 mo: 20.54 (13.51); 6 mo: 21.93 (14.35); 12 mo: 20.02 (13.73) | Adolescent sons: there were no significant differences between reports of discussions by sons whose fathers were in the intervention group; did not report more discussions than those in the control groups at any of the postintervention assessments | ||

| Saving Sex for Laterb | Assessed whether 14 topics had ever been discussed; responses summed to yield a score that ranged from 0 to 14; scores outcome denotes percent reporting lower scores | Pre: 22.6%; post: 13.9% | Pre: 18.7%; post: 25.7% | Parents in the intervention group were less likely to report low levels of communication after the intervention | |

| Strong African American Familiesb | Assessed whether 9 topics had ever been discussed; 3 response options (ie, no, yes, quite a bit) | Pre: 4.97 (3.01); post (3 mo): 0.14 (0.12)h | Pre: 5.76 (3.03); post (3 mo): −0.16 (0.13)h | Parents reported greater communication between the pretest and posttest assessments | |

| Keepin It REALa | Assessed whether mothers had ever discussed 15 items; reported percentage of topics discussed in the previous 3 mo | Parents: pre: NR; 4 mo: NR; 12 mo: NR; 24 mo: 55% (intervention based on SCT); 54% (intervention based on LSK) | Parents: pre: NR; 4 mo: NR; 12 mo: NR; 24 mo: 45% | Mothers in the SCT group reported discussing a greater proportion of topics compared to those in the control group; there was no difference in the proportion of topics discussed between mothers in the LSK group compared with the control group | |

| Adolescents: pre: NR; 4 mo: NR; 12 mo: NR; 24 mo: NR | Adolescents: pre: NR; 4 mo: NR; 12 mo: NR; 24 mo: NR | ||||

| Skills | Lefkowitz | External assessment of maternal and adolescent speaking time and 4 maternal communication behaviors (asking questions, asking open-ended questions, showing support, being nonjudgmental) when discussing sexuality and AIDS | Conversations about sexuality | Conversations about sexuality | Parents: intervention mothers spoke less at time 2 than at time 1 compared with the delayed control group when discussing AIDS; intervention mothers were less judgmental at time 2 than at time 1 compared with the delayed control group when discussing AIDS; intervention mothers asked more open-ended questions at time 2 than at time 1 compared with the delayed control group when discussing AIDS or sexuality |

| Speaking time: NR | Speaking time: NR | ||||

| Asking questions: pre: 3.8 (1.5); post: 4.3 (1.0); F statistic: 1.49 (.23) | Asking questions: pre: 3.6 (1.6); post: 3.4 (1.4) | ||||

| Asking open-ended questions: pre: 3.2 (1.1); post: 3.6 (1.3); F statistic: 3.80 (.06) | Asking open-ended questions: pre: 3.4 (1.5); post: 2.8 (1.4) | ||||

| Showing warmth/support: pre: 3.6 (0.6); post: 3.4 (0.8); F statistic: 0.53 (.47) | Showing warmth/support: pre: 3.9 (0.5); post: 3.4 (1.2) | ||||

| Being non-judgmental: pre: 4.8 (0.4); post: 4.8 (0.5); F statistic: 2.05 (.16) | Being nonjudgmental: pre: 4.8 (0.5); post: 4.4 (1.2) | ||||

| Conversations about AIDS | Conversations about AIDS | ||||

| Speaking time: 38 s less than controls (P = .4) | Speaking time: 38 s more than intervention (P = .4) | ||||

| Asking questions: pre: 3.0 (1.4); post: 3.4 (1.3); F statistic: 0.62 (0.44) | Asking questions: pre: 3.0 (1.7); post: 2.9 (1.2) | ||||

| Asking open-ended questions: pre: 2.3 (1.3); post: 3.2 (1.3); F statistic: 6.03 (0.02) | Asking open-ended questions: pre: 2.7 (1.5); post: 2.3 (1.2) | ||||

| Showing warmth/support: pre: 3.6 (0.6); post: 3.6 (0.7); F statistic: 0.30 (0.59) | Showing warmth/support: pre: 3.8 (0.5); post: 3.7 (0.8) | ||||

| Being nonjudgmental: pre: 4.7 (0.4); post: 5.0 (0.2); F statistic: 9.08 (0.004) | Being nonjudgmental: pre: 4.9 (0.4); post: 4.6 (0.6) | ||||

| Intentions | REAL Menb | Assessed intentions regarding discussing 16 sexual topics in the future; 5 response options (eg, definitely won't, definitely will); responses summed to yield a summary score that and ranged from 16 to 80. | Pre: NR; 3 mo: 72.75 (10.05); 6 mo: 70.51 (10.12); 12 mo: 70.37 (12.37) | Pre: NR; 3 mo: 70.10 (13.68); 6 mo: 70.50 (13.28); 12 mo: 67.32 (14.66) | There were no differences in intentions to communicate between the intervention and control groups at 3 and 6 mo; fathers in the intervention group had greater intentions to communicate at the 12-mo postintervention assessment |

| Keepin' it REALb | Assessed intentions to discuss each of 15 sexual topics in the future; reported percentage of topics mothers intended to discuss in future | Pre: NR; 4 mo: NR; 12 mo: NR; 24 mo: 78% (SCT); 69% (LSK) | Pre: NR; 4 mo: NR; 12 mo: NR; 24 mo: 60% | Mothers in the SCT and LSK groups reported greater intentions to discuss topics compared with those in the control group | |

| Self-efficacy | Parents Mattera | Parents: 5-item scale; 3-point Likert scale (eg, not true at all, very true); higher score denotes greater self-efficacy | No pre/post outcome data were presented, only differences in mean change between assessment periods | See right | Enhanced intervention (2 sessions) showed improved parental self-efficacy (parental and adolescent reports) compared with single-session intervention or control group |

| Adolescents: 6-item scale; 3-point Likert scale; higher score denotes greater perceived parental self-efficacy | Magnitude of change between preintervention and immediate postintervention assessments was greater among adolescents than parents; at subsequent follow-up visits, magnitude of change was reportedly greater among parents than adolescents, although the magnitude of difference in means declined over time | ||||

| Saving Sex for Laterb | Assessed how prepared parents felt to discuss specific sexual health issues; 7-item scale; 4 response options (eg, not at all, very prepared); responses summed to yield a score that ranged from 7 to 28; scores were dichotomized, outcome denotes the percentage with lower scores | Pre: 32.9; post: 16.4 | Pre: 27.0; post: 23.6 | Parents in the intervention group were less likely to report low levels of self-efficacy compared to control group parents | |

| Keepin' it REALb | 16-item scale assessing parenting self-efficacy for talking with adolescents about sex; 7-point scale (eg, not sure at all, completely sure); higher scores denote greater self-efficacy | Exact point estimates for pretest or postintervention (4, 12, and 24 mo) outcomes were not presented | See right | Data were not reported, but authors stated that self-efficacy for communication increased over time | |

| REAL Menb | Assessed confidence talking with sons about sex; 17 items; 7-point Likert scale (eg, not sure at all, completely sure); responses summed to yield a summary score that ranged from 17 to 119; higher scores denote greater confidence | Pre: NR; 3 mo: 96.55 (13.16) | Pre: NR; 3 mo: 88.73 (21.80) | Fathers in the intervention group had increased self-efficacy scores compared to control group fathers | |

| Talking Parentsa | One item assessed ability to communicate about sexual health topics; 7-point Likert scale (eg, excellent, terrible) | Exact point estimates for pretest or postintervention (1 wk, 3, and 9 mo) outcomes not presented | See right | Parents: intervention parents reported significantly higher self-efficacy for communication at each follow up assessment (1 wk, 3 and 9 mo) | |

| Adolescents: intervention adolescents reported significantly higher self-efficacy for communicating with parents at 3 and 9 mo | |||||

| Comfort | CHAMPb | Number and type of items not described, 4-point Likert scale | Pre: 16.2 (4.3); post: 9.5 (3.8); t score: −17.4 | Pre: NR; post: 17.3 (4.2); t score: −10.4 | Increased comfort with communicating among intervention group relative to control group |

| Lefkowitza | Comfort talking about 10 sexuality-related topics; 7-point Likert scale; responses summed and mean score reported | Parents: pre: 4.6 (1.4); post: 4.8 (0.9) | Parents: pre: 5.1 (0.6); post: 5.0 (0.7) | Increased comfort with general communication reported by adolescents but not mothers | |

| Adolescents: pre: 5.0 (0.7); post: 5.2 (0.6) | Adolescents: pre: 4.7 (1.0); post: 4.5 (1.0) | ||||

| Keepin' it REALa | Assessed comfort discussing each of 15 topics; reported percentage of topics mothers comfortable discussing in the previous 3 mo | Parents: pre: NR; 4 mo: NR; 12 mo: NR; 24 mo: 62% (SCT); 59% (LSK) | Parents: pre: NR; 4 mo: NR; 12 mo: NR; 24 mo: 44% | Mothers in the SCT and LSK groups reported greater comfort compared to the control group | |

| Adolescents: pre: NR; 4 mo: NR; 12 mo: NR; 24 mo: NR | Adolescents: pre: NR; 4 mo: NR; 12 mo: NR; 24 mo: NR | ||||

| Attitudes | Parent, Young Adolescent Family Life Education (PYAFLE) projecta | Assessed self-reported personal attitudes toward parent-adolescent communication with adolescent about sex; No. of items not provided; 4-point Likert scale (eg, strongly agree, strongly agree) | Parents: pre: NR (PO); NR (AO); NR (PAT); NR (PAS); NR (PAST); 2 mo: NR (PO); NR (AO); NR (PAT); NR (PAS); NR (PAST) | Parents: pre: NR; 2 mo: NR | Parents: the difference between pretest and posttest means for the control and all intervention groups was “minimal”; the control group experienced no change in the pretest and posttest means; the PO and PAT groups experienced a decrease in mean attitudinal scores between the pre- and postintervention assessment; the greatest improvement in self-reported personal attitudes was among parents in the PAS group |

| Adolescents: pre: 2.84 (NR) (PO); 2.71 (NR) (AO); 2.89 (NR) (PAT); 2.82 (NR) (PAS); 2.83 (NR) (PAST); 2 mo: 2.95 (NR) (PO); 2.78 (NR) (AO); 2.90 (NR) (PAT); 2.83 (NR) (PAS); 2.92 (NR) (PAST) | Adolescents: pre: 2.82; 2 mo: 2.83 | Adolescents: the control group and the PAS and PAT groups experienced no change; the greatest improvement in attitudes was among the PO and PAST groups | |||

| Outcome expectations | Keepin' it REALb | Assessed mothers' perception of outcomes associated with talking about sexual topics using a 15-item scale; 5-point scale (eg, strongly disagree, strongly agree); responses summed to yield a summary score that ranged from 15 to 75; higher scores denote greater perceived positive outcomes | Exact point estimates for pretest or postintervention (4, 12, and 24 mo) outcomes were not present | See right | There was no difference between pre- and postintervention assessment in outcome expectations |

| REAL Menb | Perceptions of outcomes expected to occur after talking with sons about sexual topics; 23 items; 5-point Likert scale (eg, strongly agree, strongly disagree); responses summed to yield a summary score that ranged from 23 to 115; higher scores correspond to more positive outcomes | NR | NR | NR | |

| Quality | Facts and Feelingsa | Parents: 5 items assessed quality of communication; 5-point Likert scale (eg, strongly agree, strongly disagree); higher scores denote higher quality | Exact point estimates for preintervention and postintervention outcomes not presented | See right | Parents: parents in the video-only and the video+newsletter groups showed a larger increase in the quality of communication than those in the control group; observed increase decreased by half in both intervention groups by 12 mo; control-group parents showed no change across assessment periods |

| Adolescents: 10 items; 5-point Likert scale (eg, strongly agree, strongly disagree); higher scores denote higher quality | Adolescents: there was no difference in adolescent reports of the quality of communication from pre- to postintervention assessment | ||||

| Talking Parentsa | Parents: 12-item scale assessed openness of parent-adolescent communication about sexual topics; 4-point Likert scale (eg, strongly agree, strongly disagree); scores assessed as the centile of the overall baseline distribution; higher scores denote more openness | Exact point estimates for preintervention and postintervention outcomes not presented | See right | Parents: parents in the intervention group reported higher scores at each follow up (1 wk and 3 and 9 mo) | |

| Adolescents: 7-item scale assessed openness of parent-adolescent communication about sexual topics; 4-point Likert scale (eg, strongly agree, strongly disagree); scores assessed as the centile of the overall baseline distribution; higher scores denote more openness | Adolescents: adolescents reported significantly higher scores at each follow up (1 wk and 3 and 9 mo) |

Reported results are significant unless otherwise specified. NS indicates not significant; NR, not reported; SCT, social cognitive theory; LSK, life skills program; PO, parent only; AO, adolescent only; PAT, parent and adolescent together; PAS, parent and adolescent separate; PAST, parent and adolescent separate then together.

Data were reported from both parents and adolescents.

Data were reported from parents only.

Responses are reported as mean (SD), unless otherwise noted.

Compared pretest/posttest means for the intervention group only.

Compared posttest mean for the intervention group to the control group.

Change in mean scale score between preassessment and postassessment periods with SD deviation in parentheses.

The F statistic tests the treatment effect at the posttest while controlling for the pretest result.

z score.

Compared with adolescents, parents seemed more likely to report that interventions had a positive effect on communication domains and reported larger preintervention/postintervention changes. We summarize the findings for each communication domain below.

Frequency of Communication

In 5 of the 6 studies that assessed frequency of communication, parents reported an increase in communication from before to after testing.44,47,52,53,55 No change was noted in 1 study.46 Four studies assessed adolescent reports of changes in the frequency of communication: 2 resulted in increases47,53; the adolescent result was not reported for 1 study52; and 1 resulted in no change.46 Only 1 study compared the magnitude of change in the frequency of communication between parents and adolescents; parents reported a larger change than adolescents.47

Content of Discussions

Six studies assessed the content of parent-adolescent conversations.45,46,48–51 Because of heterogeneity in how this communication domain was defined (ie, number of new topics discussed, repeated topics, individual topics discussed, percentage of topics discussed, mean number of topics discussed, and percentage that reported lower scores from scale measures), it is difficult to summarize the findings. In general, parents reported an increase in the content of communication, whereas adolescent reports were highly varied. Only 1 study compared the magnitude of change in the mean number of repeated topics reported by parents and adolescents.51 The study authors found that parents reported discussing more topics at the postintervention assessment than adolescents.

Skills for Communicating

One study assessed parental skills for communicating.46 In that study, parents and adolescents were directly observed discussing both sexuality and AIDS. The skills assessed were how long the mothers and adolescents each spoke, how many questions mothers asked, the number of open-ended questions the mothers asked, maternal display of warmth, maternal display of support, and maternal use of nonjudgmental behaviors. Compared with mothers in a control condition, mothers who participated in the intervention group spoke less and were less judgmental when discussing AIDS at the postintervention assessment compared with the preintervention assessment. Compared with mothers in a control condition, mothers who participated in the intervention group asked more open-ended questions when discussing sexuality or AIDS at the postintervention assessment compared with the preintervention assessment.

Intentions to Communicate

Two studies assessed communication intentions. In both studies, parents reported an increase in their intentions to communicate.45,48 Data were not collected from adolescents in either study.

Self-efficacy for Communicating

Five studies assessed parental self-efficacy for communicating.45,47–49,51 Data were reported from only 4 studies.47–49,51 In all 4 studies, parents reported an increase in their self-efficacy for communicating. Two studies assessed adolescent reports of changes in self-efficacy. In 1 study, adolescents reported an increase in their perception of their parents' self-efficacy for communicating with them about sex.47 In the second study, adolescents reported an increase in their self-efficacy for communicating with their parent about sex.51 Only 1 study compared the magnitude of change reported by parents versus adolescents, and the authors noted that parents reported a larger change than adolescents.47

Comfort With Communicating

Three studies reported communication comfort instead of or in addition to self-efficacy.44–46 Parents reported an increase in comfort in 2 studies.44,45 Only 1 study reported data from adolescents, and the authors noted an improvement.46 The magnitude of the change in communication comfort reported by parents and adolescents was not compared in any of these studies.

Attitudes Toward Communicating

One study assessed attitudes toward communicating, and the authors noted no significant change in parents' or adolescents' self-reported personal attitudes towards parent-adolescent communication about sex.54

Outcomes Expected to Occur After Communicating

Two studies assessed the outcomes expected to occur as a result of parent-adolescent discussions about sex.45,48 Both studies assessed only parental perspectives, but the authors of only 1 study reported actual data for this outcome45 and noted no change in outcome expectations.

Quality (ie, Beliefs) of Communication

Quality of communication was included as a marker of parental beliefs about communicating. In both studies that assessed the quality of communication, parents reported improvements.51,53 The duration of this effect seemed to decline over time in 1 study53 yet continued to improve significantly in the other.51 Adolescents reported improvement in the quality of communication in 1 study51 but no change in quality in the other.53 The magnitude of the change in quality reported by parents and adolescents was not compared in either study.

Methodologic Quality

The frequency distributions for each element of the MQS are listed in Table 3. MQSs ranged from 6 to 16 points (mean: 12 ± 3) (Table 4). Only 1 study had an MQS in the lower-quality range54; 7 were of medium quality,44,46,48,49,51,52,55 and 4 were of high quality.45,47,50,53

TABLE 3.

Criteria for Assessing Methodologic Quality and Frequency Distributions for Each Quality Characteristic

| Methodologic Characteristic | Scoring Options (Maximum Total Score = 20 Points) | Distribution of Characteristics Among Included Studies |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency, n (%) | Reference No. | ||

| Definition of parental communication | Not reported: 0 | 1 (8) | 54 |

| Global: 1 | 0 (0) | — | |

| Communication domain-specific: 2 | 11 (92) | 44–53 and 55 | |

| Validity data for parental communication scores | Not reported: 0 | 11 (92) | 44 and 46–55 |

| Reported: 1 | 1 (8) | 45 | |

| Reliability data for parental communication scores | Not reported: 0 | 5 (42) | 44, 46, 49, 51, and 54 |

| Reported: 1 | 7 (58) | 45, 47, 48, 50, 52, 53, and 55 | |

| Validity/reliability data for other main variables in study | Not reported: 0 | 9 (75) | 44, 46–49, 51, 52, 54, and 55 |

| Reported: 1 | 3 (25) | 45, 50, and 53 | |

| Theoretical framework presented | Did not present: 0 | 5 (42) | 46 and 52–55 |

| Presented: 1 | 7 (58) | 44, 45, and 47–51 | |

| Research paradigm | Quantitative or qualitative: 1 | 12 (100) | 44–55 |

| Mixed methods: 2 | 0 (0) | — | |

| Study design | Correlational or cross-sectional: 1 | 6 (50) | 44, 49, 50, 52, 54, and 55 |

| Longitudinal: 2 | 6 (50) | 45–48, 51, and 53 | |

| Sample size | Undetermined: 0 | 1 (8) | 52 |

| <100: 1 | 2 (17) | 46 and 55 | |

| >100 to <300: 2 | 4 (33) | 44, 48, 50, and 54 | |

| >300: 3 | 5 (42) | 45, 47, 49, and 51, 53 | |

| Sample design | Convenience/nonprobability: 0 | 4 (33) | 44, 52, 54, and 55 |

| Random/probability but not nationally representative: 1 | 8 (67) | 45–51 and 53 | |

| Random/probability and nationally representative: 2 | 0 (0) | — | |

| Data analysis | Qualitative/univariate/descriptive: 1 | 0 (0) | — |

| Bivariate/ANOVA: 2 | 4 (33) | 44, 46, 52, and 54 | |

| Multiple/logistic regressions: 3 | 6 (50) | 45, 47, 48, 51, 53, and 55 | |

| Multivariate: 4 | 2 (17) | 49 and 50 | |

| Appropriate inferences of causality | Inappropriate: 0 | 2 (17) | 49 and 54 |

| Appropriate: 1 | 10 (83) | 44–48, 50–53, and 55 | |

ANOVA indicates analysis of variance.

TABLE 4.

Methodologic Quality Scores for Each Intervention

| Intervention | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | MQS Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Keepin' it Real45 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 17 |

| Facts and Feelings53 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 15 |

| Parents Matter!47 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 15 |

| Strong African American Families (SAAF)50 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 15 |

| REAL Men48 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 14 |

| Talking Parents, Healthy Teens51 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 14 |

| Saving Sex for Later49 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 13 |

| Huston intervention55 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 10 |

| CHAMP44 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 10 |

| Lefkowitz intervention46 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 10 |

| Families in Touch52 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 8 |

| Parent, Young Adolescent Family Life Education Project (PYAFLE)54 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 6 |

Definition of parental communication outcomes: B, validity data for parental communication measures; C, reliability data for parental communication measures; D, validity and reliability data for other intervention variables; E, theoretical framework; F, research paradigm; G, design; H, sample size; I, sample design; J, data analysis; K, appropriate inferences of causality.

Reliability/Validity Assessment

Studies infrequently reported validity or reliability data for the measures used to assess study outcomes. For 7 studies the communication outcome measures were developed de novo,46,47,49,51,53–55 and psychometric data were reported for their scales in only 3 studies.

Theoretical Grounding

The authors of 7 studies reported using a theoretical framework to guide the intervention design and analytic inquiry.44,45,47–51 The most commonly used theory was social cognitive theory.45,48

Research Paradigm

All the interventions used a quantitative, questionnaire-based analytic paradigm; follow-up cross-sectional study designs were the most frequently used. None of the studies used a qualitative research paradigm or mixed-methods evaluation approach.

Study Design

Five studies used a longitudinal design (ie, postintervention assessment with at least 1 additional follow-up assessment). Four of these studies conducted 1 immediate postintervention assessment and 2 additional follow-up assessments; the other study included 1 postintervention assessment and 1 additional follow-up assessment. In these longitudinal studies, participants were followed for a maximum of 9,51 12,47,48 or 2445 months.

Sample Size and Design

Nine studies used a medium sample size44,48,50,53,54 (100–300 participants) or larger45,47,49,51 (>300 participants), but the majority of them used convenience, nonprobability samples. None of the studies included a sample that was both randomly selected and nationally representative. Conduction of a power calculation to determine the sample size needed to assess the study outcomes was reported for only 2 studies.

Analytic Approach

Half the studies used multiple or logistic regression techniques to analyze their data,45,47,48,51,53,55 whereas one-third reported only bivariate methods (eg, correlations or analysis of variance).44,46,52,54 The authors of only 2 studies cited using a repeated-measures design.49,50 Similarly, few authors reported using analytic techniques to account for nested study designs for studies in which the participants participated in group-based facilitated interventions or when they were recruited from multiple settings (eg, schools, community organizations). Use of multivariate analytical techniques (eg, structural equation modeling) was not reported from any study.

Inferences of Causality

Given many of the studies' sample and design limitations, we were interested in assessing each researcher group's awareness and acknowledgment of their study's limitations and ability (or not) to establish cause-effect relationships. Among the reviewed studies, limitations of the findings were accurately reported for 10; authors of 2 reports inappropriately stated or implied that their intervention was effective despite multiple threats to internal validity (eg, sample size, analytic approach, limited follow-up data) that made such determination difficult.

DISCUSSION

We compared the effectiveness and methodologic quality of select interventions that met our inclusion criteria and were designed to improve parents' ability to communicate with their adolescents about sex. Our evaluation was limited by the fact that every study used a different measure to assess the same communication domain. Which measures are used will certainly affect whether significant findings are observed. Despite this heterogeneity among the communication-outcome measures, the data suggest that parent-adolescent communication interventions have some targeted effects. Compared with controls, parents who participate in these interventions experience improvements in multiple communication domains. We noted improvements in the frequency, quality, intentions, comfort, and self-efficacy for communicating. We did not find any effect on parental attitudes toward communicating or the outcomes they expected to occur as a result of communicating.

Communication is a complex process. We assessed specific aspects of the communication process defined by our guiding conceptual model. However, other facets of communication and other conceptual frameworks are likely equally important. For example, Jaccard58 identified 5 aspects of parent-adolescent communication as important: the extent of communication as measured by frequency and depth of discussions; the style or manner in which information is communicated; the content of the information discussed; the timing of communication; and the general family environment or overall relationship between the parent and child. Had we assessed a different set of communication outcomes, our overall perception of the effectiveness of these interventions may have differed.

Although positive effects on the frequency, content, and psychosocial mediators of parental communication with adolescents about sex were noted for most interventions, few studies assessed the durability of these effects over time. Those that did found mixed results. Because adolescents' sexual knowledge and behaviors change throughout adolescence, parents' approach to discussing sex with their adolescents must change as well. It remains unclear whether participation in these interventions provides sufficient support for parents' communication efforts throughout their child's adolescence. Future studies should seek to clarify the long-term effect of these interventions on parent-adolescent communication about sex.

The explicit teaching and measurement of communication-skills acquisition received little attention in the studies included in this evaluation. Yet, the results indicate that the approaches parents take when talking with their adolescent about sex may have a tremendous influence on the adolescent. For example, parents who dominate conversations (ie, talk more) have adolescents who are less knowledgeable about sexual health topics.59,60 Because communication skills are important, researchers have suggested that parents be taught certain general communication skills such as how to talk less and listen more, be less directive, ask more questions of their adolescent, and behave in a nonjudgmental fashion.46,61–63 Adolescents whose parents engage in these behaviors report greater comfort discussing sex with their parents and discussing more topics.46 Research in this area needs a greater focus on identifying which communication skills are most effective for transmitting sexual health knowledge and decision-making skills to their adolescents.

With 1 exception, mothers were the primary participant in all interventions. None of the studies compared intervention effects on fathers and mothers. Although mothers primarily communicate with adolescents about sex,11,64–66 fathers do play a role in their adolescents' sexual socialization.67 However, mothers and fathers play different roles.68,69 Kirkman et al68 examined the role of fathers in family discussions about sex through in-depth interviews with parents and adolescents of both genders. They found that the pubertal transition often disrupts the relationship and communication patterns fathers have with their children; that fathers find discussions about sex difficult and distressing; and that fathers generally leave the task of talking about sex to mothers, although fathers perceive the responsibility of communicating to be a shared one. Additional work is needed to explore intervention effects on mothers versus fathers, because interventions for improving parental communication about sex may require tailoring to maximize their effectiveness among each. Similarly, none of the included interventions explored whether intervention effects varied according to adolescent gender. Given that parental discussions about sex vary in frequency and content for adolescent boys and girls,66,69,70 additional work is needed to determine if these interventions produce differential effects based on adolescent gender.

Implications

Despite the limitations inherent in parent-adolescent communication interventions, our interpretation of the data is that these interventions, at a minimum, improve the frequency and content of discussions about sex between parents and their adolescents. Wider dissemination of the interventions seems warranted but should be done in conjunction with additional studies that clarify these interventions' effects. For example, communication measures should be standardized, and differential intervention effects among mothers versus fathers and among adolescent boys versus girls should be explored.

The need to expand delivery of interventions for improving parental communication with adolescents about sex is exemplified by a recent troubling report. The report cited data from 1988, 1995, and 2002 and showed significant declines in US female adolescents' reports of parent-adolescent communication about contraception and sexually transmitted infections and stable but low reporting by adolescent boys of discussions with parents about contraception.71 These declines coincided with decreases in adolescent reports of receiving school-based sex education and increases in adolescent birth rates.72 Thus, adolescents seem to be experiencing a historic reversal in reproductive health trends while receiving less information about sexual health topics from both parents and schools. Increasing delivery of content via parent-adolescent communication interventions could play a critical role in reducing adverse outcomes among adolescents.

A major challenge in scaling up delivery of parent-adolescent communication interventions is achieving economy of scale. As noted in our review, most existing interventions involve face-to-face facilitated formats. Face-to-face interventions require trained personnel, require significant time commitments by parents, and have limited reach because few parents can be accommodated per training cycle. Mass media, multimedia, and some of the new social-networking programs may be critical for disseminating these interventions more widely. They are less costly once development costs have been expended, which makes them potentially more affordable and easier to disseminate. Few of the interventions included used mass-media formats, and none of them used small media (eg, Web, text-messaging).

Limitations

When evaluating interventions, it is useful to know not only whether an intervention is effective but to understand what intervention components are most correlated with success. Because we were unable to calculate effect sizes, we cannot state whether more effective studies have specific characteristics or components in common. Moreover, few authors reported whether their sample size was sufficiently powered, which makes it is impossible to know whether the findings are truly significant. Each study used different communication measures, often creating them de novo and infrequently providing details about the measures' psychometric properties. Lack of detail about the measures' generalizability or reliability when tested in different populations makes it difficult to compare results across studies. It also means we were unable to determine which communication domains are most strongly affected by parent-targeted interventions.

CONCLUSIONS

Parent-targeted interventions for improving parental communication with adolescents about sex have been well designed and improve multiple facets of family communication. However, communication measures need to be standardized to make it easier to compare the effectiveness of various interventions. The relative effect of these interventions among mothers and fathers are unknown. Given that parental communication is associated with positive effects on adolescent sexual behavior, these interventions may represent a valuable tool for improving adolescent sexual and reproductive health.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was supported by National Institutes of Health Roadmap Multidisciplinary Clinical Research Career Development Award grant 1 KL2 RR024154-01. Support was also provided by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Amos Medical Faculty Development Program. Information on the NCRR is available at www.ncrr.nih.gov, and information on Re-engineering the Clinical Research Enterprise can be obtained from http://commonfund.nih.gov/clinicalresearch/overview-translational.aspx.

Anne E. George and Karen Derzic assisted with data abstraction.

Dr Akers designed the study; Dr Akers and Ms Holland abstracted the data; and Dr Akers, Ms Holland, and Dr Bost analyzed the data and prepared and reviewed the manuscript.

The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the National Center for Research Resources or of National Institutes of Health.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

- MQS

- methodologic quality score

REFERENCES

- 1. Cates W., Jr Estimates of the incidence and prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases in the United States. American Social Health Association Panel. Sex Transm Dis. 1999;26(4 suppl):S2–S7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Special Focus Profiles: STDs in Adolescents and Young Adults. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Braverman PK. Sexually transmitted diseases in adolescents. Med Clin North Am. 2000;84(4):869–889, vi–vii [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Weinstock H, Berman S, Cates W., Jr Sexually transmitted diseases among American youth: incidence and prevalence estimates, 2000. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2004;36(1):6–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Starkman N, Rajani N. The case for comprehensive sex education. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2002;16(7):313–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy Proportion of All Pregnancies That Are Unplanned by Various Socio-demographics, 2001. New York, NY: National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, et al. ; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth Risk Behavioral Surveillance: United States, 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(4):1–131 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Huebner A, Howell L. Examining the relationship between adolescent sexual risk-taking and perceptions of monitoring, communication, and parenting styles. J Adolesc Health. 2003;33(2):71–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hutchinson MK, Jemmott JB, III, Jemmott LS, Braverman P, Fong GT. The role of mother-daughter sexual risk communication in reducing sexual risk behaviors among urban adolescent females: a prospective study. J Adolesc Health. 2003;33(2):98–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Longmore M, Manning W, Giordano P. Preadolescent parenting strategies and teens' dating and sexual initiation: A longitudinal analysis. J Marriage Fam. 2001;63(2):322–335 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Meschke LL, Bartholomae S, Zentall SR. Adolescent sexuality and parent-adolescent processes: promoting healthy teen choices. J Adolesc Health. 2002;31(suppl l6):264–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. DeVore E, Ginsburg K. The protective effects of good parenting on adolescents. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2005;17(4):460–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jaccard J, Dodge T, Dittus P. Parent-adolescent communication about sex and birth control: a conceptual framework. In: Talking Sexuality: Parent-Adolescent Communication. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2002:9–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kirby D, Miller BC. Interventions designed to promote parent-teen communication about sexuality. New Dir Child Adolesc Dev. 2002;(97):93–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fishbein M, Bandura A, Triandis H, Kanfer F, Becker M, Middlestadt SE. Factors influencing behavior and behavior change: final report to the Theorist's Workshop. In: Theorist's Workshop. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Mental Health; 1991 [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fishbein M, Triandis HC, Kanfer FH, Becker M, Middlestadt SE, Eichler A. Factors influencing behavior and behavior change. In: Baum A, Revenson TA, Singer JE. Handbook of Health Psychology. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2001:3–17 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ashcraft AM. A Qualitative Investigation of Urban African American Mother/Daughter Communication About Relationships and Sex [PhD dissertation] Richmond, VA: Virginia Commonwealth University; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bhushan R. A study of family communication: parents and their adolescent children. J Pers Clin Stud. 1993;9:79–85 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Guilamo-Ramos V, Jaccard J, Dittus P, Bouris A, Holloway I, Casillas E. Adolescent expectancies, parent-adolescent communication and intentions to have sexual intercourse among inner-city, middle school youth. Ann Behav Med. 2007;34(1):56–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jaccard J, Dittus P, Gordon V. Parent-adolescent congruency in reports of adolescent sexual behavior and in communications about sexual behavior. Child Dev. 1998;69(1):247–261 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Buhi ER, Goodson P. Predictors of adolescent sexual behavior and intention: a theory-guided systematic review. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40(1):4–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Goodson P, Buhi ER, Dunsmore MS. Self-esteem and adolescent sexual behaviors, attitudes and intentions: a systematic review. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38(3):310–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Benshoff J, Alexander S. The family communication project: Fostering parent-child communication about sexuality. Elem Sch Guid Couns. 1993;27(4):288–300 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Burgess V, Dziegielewski SF, Green CE. Improving comfort about sex communication between parents and their adolescents: practice-based research within a teen sexuality group. Brief Treat Crisis Interv. 2005;5(4):379–390 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Green HH, Documet PI. Parent peer education: lessons learned from a community-based initiative for teen pregnancy prevention. J Adolesc Health. 2005;37(3 suppl):S100–S107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Klein JD, Sabaratnam P, Pazos B, Auerbach MM, Havens CG, Brach MJ. Evaluation of the parents as primary sexuality educators program. J Adolesc Health. 2005;37(3 suppl):S94–S99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bennett JA, Contessa ST, Turner LC. Parent to parent: preventing adolescent exposure to HIV. Holist Nurs Pract. 1999;14(1):59–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dancy BL, Crittenden KS, Talashek ML. Mothers' effectiveness as HIV risk reduction educators for adolescent daughters. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2006;17(1):218–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. DeVore ER, Dean K, Joyce E, McKay MM. A multiple-family group HIV prevention program for drug-involved mothers and their young children. J HIV AIDS Soc Serv. 2004;3(2):27–46 [Google Scholar]

- 30. DiIorio C, McCarty F, Denzmore P, Landis A. The moderating influence of mother-adolescent discussion on early and middle African-American adolescent sexual behavior. Res Nurs Health. 2007;30(2):193–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Henschke JA. New directions in facilitating the teaching role of parents in the sex education of their children. Presented at: National Adult Education Conference; Louisville, KY; November 8, 1984 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jacknik M, Isberner F, Gumerman S, Hayworth R, Braunling-McMorrow D. OCTOPUS: a church-based sex education program for teens and parents. Adolescence. 1984;19(76):757–763 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kirby D, Peterson L, Brown JG. A joint parent-child sex education program. Child Welf. 1982;61(2):105–115 [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lederman RP, Chan W, Roberts-Gray C. Parent-adolescent relationship education (PARE): program delivery to reduce risks for adolescent pregnancy and STDs. Behav Med. 2008;33(4):137–143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Snegroff S. Communicating about sexuality: a school/community program for parents and children. J Health Educ. 1995;26(1):49–51 [Google Scholar]

- 36. Stanton BF, Li X, Ricardo I, Galbraith J, Feigelman S, Kaljee L. A randomized, controlled effectiveness trial of an AIDS prevention program for low-income African-American youths. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1996;150(4):363–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Caron SL, Knox CB, Rhoades C, Aho J, Tulman KK, Volock M. Sexuality education in the workplace: seminars for parents. J Sex Educ Ther. 1993;19(3):200–212 [Google Scholar]

- 38. Davis SL, Koblinsky SA, Sugawara AI. Evaluation of a sex education program for parents of young children. J Sex Educ Ther. 1986;12(1):32–37 [Google Scholar]

- 39. Prado G, Pantin H, Briones E, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a parent-centered intervention in preventing substance use and HIV risk behaviors in Hispanic adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75(6):914–926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Baptiste D, Voisin DR, Smithgall C, Martinez DDC, Henderson G. Preventing HIV/AIDS among Trinidad and Tobago teens using a family-based program: preliminary outcomes. Soc Work Ment Health. 2007;5(3–4):333–354 [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gallegos EC, Villarruel AM, Gomez MV, Onofre DJ, Zhou Y. Research brief: sexual communication and knowledge among Mexican parents and their adolescent children. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2007;18(2):28–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Phetla G, Busza J, Hargreaves JR, et al. “They have opened our mouths”: increasing women's skills and motivation for sexual communication with young people in rural South Africa. AIDS Educ Prev. 2008;20(6):504–518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Villarruel AM, Cherry CL, Cabriales EG, Ronis DL, Zhou Y. A parent-adolescent intervention to increase sexual risk communication: results of a randomized controlled trial. AIDS Educ Prev. 2008;20(5):371–383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. McKay MM, Chasse KT, Paikoff R, et al. Family-level impact of the CHAMP Family Program: a community collaborative effort to support urban families and reduce youth HIV risk exposure. Fam Process. 2004;43(1):79–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. DiIorio C, Resnicow K, Thomas S, et al. Keepin' it R.E.A.L.! Program description and results of baseline assessment. Health Educ Behav. 2002;29(1):104–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lefkowitz ES, Sigman M, Au TK. Helping mothers discuss sexuality and AIDS with adolescents. Child Dev. 2000;71(5):1383–1394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Forehand R, Armistead L, Long N, et al. Efficacy of a parent-based sexual-risk prevention program for African American preadolescents: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(12):1123–1129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. DiIorio C, McCarty F, Resnicow K, Lehr S, Denzmore P. REAL men: a group-randomized trial of an HIV prevention intervention for adolescent boys [published correction appears in Am J Public Health. 2007;97(8):1350]. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(6):1084–1089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. O'Donnell L, Stueve A, Agronick G, Wilson-Simmons R, Duran R, Jeanbaptiste V. Saving Sex for Later: an evaluation of a parent education intervention. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2005;37(4):166–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Brody GH, Murry VM, Gerrard M, et al. The Strong African American Families Program: translating research into prevention programming. Child Dev. 2004;75(3):900–917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Schuster MA, Corona R, Elliott MN, et al. Evaluation of Talking Parents, Healthy Teens, a new worksite based parenting programme to promote parent-adolescent communication about sexual health: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2008;337:a308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Crawford I, Jason LA, Riordan N, et al. A multimedia-based approach to increasing communication and the level of AIDS knowledge within families. J Community Psychol. 1990;18:361–373 [Google Scholar]

- 53. Miller BC, Norton MC, Jenson GO, Lee TR, Christopherson C, King PK. Impact evaluation of Facts & Feelings: A home-based video sex education curriculum. Fam Relat. 1993;42(4):392–400 [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hamrick MH. Parent, adolescent FLE: an evaluation of five approaches. Fam Life Educ. 1985;4(1):12–16 [Google Scholar]

- 55. Huston RL, Martin LJ, Foulds DM. Effect of a program to facilitate parent-child communication about sex. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1990;29(11):626–633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. DiIorio C, Resnicow K, McCarty F, et al. Keepin' it R.E.A.L.!: results of a mother-adolescent HIV prevention program. Nurs Res. 2006;55(1):43–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. US Census Bureau Geographic terms and concepts: U.S. Census Bureau, 2008 redistricting data prototype (Public Law 94-171) summary file. Available at: www.census.gov/geo/www/geoareas/GTC_08.pdf Accessed January 14, 2011

- 58. Jaccard J. Adolescent contraceptive behavior: conceptual and applied issues. Presented at: Improving Contraceptive Use in the United States: Assessing Past Efforts and Setting New Directions, Bethesda, MD; October 5–6, 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lefkowitz ES, Kahlbaugh P, Au TK, Sigman M. A longitudinal study of AIDS conversations between mothers and adolescents. AIDS Educ Prev. 1998;10(4):351–365 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Whalen CK, Henker B, Hollingshead J, Burgess S. Parent adolescent dialogues about AIDS. J Fam Psychol. 1996;10(3):343–357 [Google Scholar]

- 61. Coombs RH, Santana FO, Fawzy FI. Parent training to prevent adolescent drug use: An educational model. J Drug Issues. 1984;14:393–402 [Google Scholar]

- 62. Foster SL, Robin AL. Parent-adolescent conflict. In: Mash EJ, Barkley RA. Treatment of Childhood Disorders. New York, NY: Gilford; 1989:493–528 [Google Scholar]

- 63. Robin AL, Koepke T. Behavioral assessment and treatment of parent-adolescent conflict. In: Hersen M, Miller R. Progress in Behavior. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1990:178–215 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Miller K, Levin M, Whitaker DJ, Xu X. Patterns of condom use among adolescents: the impact of mother adolescent communication. Am J Public Health. 1998b;88(10):1542–1544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Lindberg L, Ku L, Sonenstein F. Adolescents' report of reproductive health education, 1988 and 1995. Fam Plann Perspect. 2000;32(5):220–226 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Miller K, Kotchick B, Dorsey S, Forehand R, Ham A. Family communications about sex: what are parents saying and are their adolescents listening? Fam Plann Perspect. 1998a;30(5):218–235 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Akers A, Burke J, Chang J, Yonas M. “Do you want somebody treating your sister like that?”: exploring African American family discussions about healthy dating relationships. J Interpers Violence. 2010; Published online October 1, 2010. DOI: 10.1177/0886260510383028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Kirkman M, Rosenthal DA, Feldman SS. Talking to a tiger: fathers reveal their difficulties in communicating about sexuality with adolescents. New Dir Child Adolesc Dev. 2002;(97):57–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Akers A, Schwarz E, Borrero S, Corbie-Smith G. Family discussions about contraception and family planning: a qualitative exploration of African American parent and adolescent experiences. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2010;42(3):160–167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Nolin M, Peterson K. Gender differences in parent-child communication about sexuality: an exploratory study. J Adolesc Res. 1992;7(1):59–79 [Google Scholar]

- 71. Robert AC, Sonenstein FL. Adolescents' reports of communication with their parents about sexually transmitted diseases and birth control: 1988, 1995, and 2002. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46(6):532–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD, Ventura SJ, Menacker F, Kirmeyer S. Births: final data for 2006. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2009;57(7):1–102 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]