Abstract

Parkinson's disease (PD) is a progressive, neurodegenerative condition that has increasingly been linked with mitochondrial dysfunction and inhibition of the electron transport chain. This inhibition leads to the generation of reactive oxygen species and depletion of cellular energy levels, which can consequently cause cellular damage and death mediated by oxidative stress and excitotoxicity. A number of genes that have been shown to have links with inherited forms of PD encode mitochondrial proteins or proteins implicated in mitochondrial dysfunction, supporting the central involvement of mitochondria in PD. This involvement is corroborated by reports that environmental toxins that inhibit the mitochondrial respiratory chain have been shown to be associated with PD. This paper aims to illustrate the considerable body of evidence linking mitochondrial dysfunction with neuronal cell death in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) of PD patients and to highlight the important need for further research in this area.

1. Introduction

Parkinson's disease (PD) is a progressive, neurodegenerative condition characterised by deterioration of the dopaminergic (DA) neurons of the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) [1, 2]. The exact mechanism by which SNpc cell death in PD occurs is poorly understood, but several lines of evidence implicate mitochondrial dysfunction as a possible primary cause due to the central role of mitochondria in energy production, along with oxidative stress, ubiquitin system impairment and excitotoxicity, all of which may be interlinked [3–5]. Mitochondrial dysfunction with complex I deficiency and impaired electron transfer in the substantia nigra in PD have been reported [3, 4]. Moreover, mutations in several mitochondrial proteins have been associated with familial forms of PD [5–7], as well as the presence of deletions in mitochondrial DNA identified in aging controls and PD substantia nigra [8]. This paper discusses the possible mechanisms relating mitochondrial impairment to cell death in PD.

2. Mitochondria

Mitochondria are found in virtually all eukaryotic cells and function to generate cellular energy in the form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) by oxidative phosphorylation and are thought to be derived evolutionarily from the fusion of prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms [9, 10]. They are also involved in regulation of cell death via apoptosis, calcium homeostasis, haem biosynthesis, and the formation and export of iron-sulphur (Fe-S) clusters, that have been reviewed in detail elsewhere [11–13], and function in the control of cell division and growth.

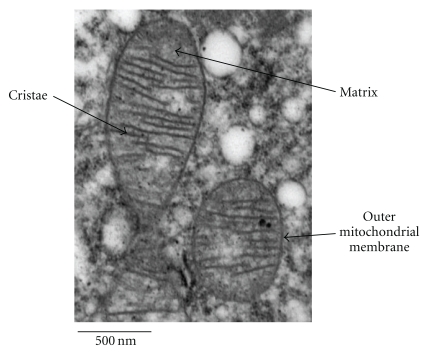

Structurally, mitochondria are composed of a double lipid bilayer with a phospholipid outer membrane and an inner membrane which surrounds the intracompartmental matrix (Figure 1). The space between the two membranes is important in, and contains the major units of, oxidative phosphorylation [9]. Mitochondria are unique amongst cellular organelles in that they have their own, circular, double-stranded, DNA (mtDNA) which is inherited almost exclusively down the maternal line and codes for 37 mitochondrial genes, 13 of which translate to proteins involved in oxidative phosphorylation [10, 14]. The remaining genes encode transfer (22) and ribosomal (2) RNA allowing the mitochondria to generate their own proteins [10]. Although mitochondria have the ability to produce proteins, the vast majority of proteins that function within the mitochondria, including those involved in DNA transcription, translation, and repair, are encoded by nuclear DNA and are transported into the mitochondria from the cytosol [10]. As mtDNA is located in the mitochondria in close proximity to the electron transport chain it is more susceptible to damage from free radicals generated during oxidative phosphorylation [15]. This damage may lead to mutations that have been linked with PD [13, 16] and will be discussed later.

Figure 1.

An electron micrograph to show mitochondrial ultrastructure. Reproduced with the kind permission of Tracy Davey, EM Research Services, Newcastle University.

2.1. Electron Transport Chain

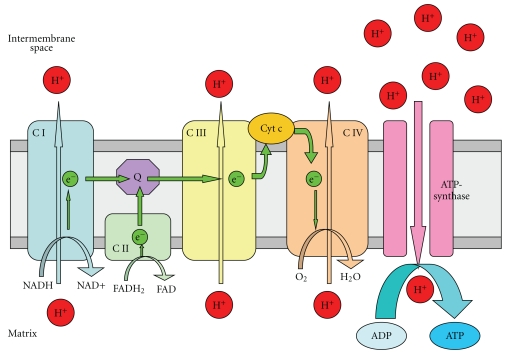

The electron transport chain is composed of five complexes including an ATP-synthase located in the inner mitochondrial membrane. The function of the chain is to generate cellular energy in the form of ATP. This is accomplished by the transport of electrons between complexes causing proton (H+ ions) movement from the matrix to the intermembrane space generating a proton concentration gradient used by ATP-synthase to produce ATP (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mitochondrial electron transport chain: schematic representation of the mitochondrial electron transport chain involved in oxidative phosphorylation. CI and II (Complexes I and II) transport electrons (e−s) generated by the conversion of NADH to NAD+ (CI) or FADH2 to FAD (CII) through Q (ubiquinone), CIII, Cyt c (cytochrome c) and finally CIV, which uses an e− to convert O2 to H2O. During electron transfer, CI, II, and IV pump protons (H+s) from the mitochondrial matrix into the intermembrane space generating a H+ concentration gradient that drives the formation of ATP from ADP by ATP-synthase (Complex V).

Whilst electron transport is a highly efficient process in mitochondria [17], during the process of oxidative phosphorylation, electrons can leak from the chain, specifically from CI [18] and CIII [19], and react with oxygen to form superoxide (·O2−). Under normal physiological conditions this ·O2− production occurs at relatively low levels, with approximately 1% of the mitochondrial electron flow forming ·O2− [20], and is removed by mitochondrial antioxidants such as manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) which converts ·O2− to H2O2 which is then converted to H2O by glutathione (GSH). Given the high activity of the respiratory chain under even normal circumstances, the small leakage of electrons in mitochondria is still a major source of ·O2− within many eukaryotic cells [21]. It is thought that dysfunction in this process leading to an increase in ·O2− production could be one of the main drivers of cell death in the SNpc in PD [22, 23].

2.2. Electron Transport Chain Dysfunction in PD

As neurons have a considerable energy need and are also highly equipped with mitochondria they are extremely sensitive to mitochondrial dysfunction. Several neurological disorders are associated with mitochondrial dysfunction and demonstrate enhanced production of free-radical species [16, 24]. The first line of evidence for a link between mitochondrial dysfunction and PD came from the description of Complex I (CI) deficiency in the postmortem SNpc of PD patients and has been suggested to be one of the fundamental causes of PD [4, 25]. This CI deficiency was also seen in the frontal cortex in PD [26], and in peripheral tissues such as platelets [27] and skeletal muscle [28] suggesting that there is a global reduction in mitochondrial CI activity in PD. This defect may be due to oxidative damage to CI and misassembly, since this is a feature of isolated PD brain mitochondria [3]. Incidental Lewy body disease (ILBD) which is considered by some to be a preclinical indicator of PD, has been shown to have an intermediate level of CI activity in the SNpc between healthy and PD patients [22] which further supports the theory of mitochondrial dysfunction. This inhibition of CI can lead to the degeneration of affected neurons by a number of mechanisms such as increased oxidative stress and excitotoxicity [23] which will be described below.

A decrease in the function of Complex III has also been reported in the lymphocytes and platelets of PD patients [27, 29]. A link between impairment of mitochondrial CIII assembly, an increase in free radical-production, and PD has also been identified [30]. This increase in free radical release may be due to the increased leakage of electrons from CIII (as explained below). Alternatively the inhibition of CIII assembly causes a severe reduction in the levels of functional CI in mitochondria [31] which could lead to an increase in free-radical production through CI deficiency. In addition, the CI and II electron acceptor ubiquinone has also shown to be reduced in the mitochondria of PD patients [32] and loss of DA neurons in aged mice treated with the Parkinsonian neurotoxin 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) was attenuated by ubiquinone [33], providing more evidence for the involvement of mitochondrial dysfunction in PD.

3. Mitochondrial Generation of ReactiveOxygen Species in PD

Complex I or III inhibition causes an increase in the release of electrons from the transport chain into the mitochondrial matrix which then react with oxygen to form reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as ·O2−, hydroxyl radicals (·OH) and nitric oxide (NO·). This increase in the normal electron leakage occurs by blockage of electron movement along the chain to the next acceptor molecule. An example of this is the finding that blockade of the electron accepting capability of the ubiquinone binding site of Complex I leads to an increased production of electron radicals in rat skeletal muscle mitochondria [34]. The ROS formed can act as signalling molecules by causing lipid peroxidation or promote excitotoxicity, all leading to modification of proteins and eventual cell death. The main areas in which ROS cause damage in the cell include oxidative DNA damage, lipid peroxidation, and protein oxidation and nitration. The ·OH radical has been shown to react with the double bond of DNA bases leading to damaging DNA lesions [35] and an impairment of normal cellular function. There is evidence linking this mechanism of cell death to PD in the finding of increased levels of 8-hydroxyguanosine, produced by oxidative damage to DNA, in the SNpc of PD patients [36, 37]. Peroxynitrite (formation discussed below) also increases DNA single-strand breaks [38] which cause activation of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) which in turn disrupts the mitochondrial respiratory chain and ATP production via depletion of intracellular NAD+ stores, so exacerbating the original mitochondrial dysfunction [39].

3.1. ROS-Mediated Protein Damage

Amongst the most common mechanisms of protein damage caused by ROS is oxidation to form carbonyl groups on proteins and nitration by peroxynitrite. Reactive ROS can readily oxidise amino acids on various cellular proteins to form carbonyl groups, which can disrupt the physiological function of the affected protein and lead to cytotoxic protein aggregates, activation of cell death pathways, and impairment of neuroprotective pathways [40]. An increase in these carbonyl groups has been reported in the SNpc and in the basal ganglia and prefrontal cortex of PD patients [41] suggesting a role in the disease which is widespread throughout the brain. Peroxynitrite formed by the reaction of ROS with nitric oxide and nitrates tyrosine residues on proteins [42], damaging them and leading to cell death. These nitrotyrosine residues are present in Lewy bodies in PD neurons signifying the possibility that protein nitration may contribute to the pathology of PD [43]. Peroxynitrite [44] and other ROS [45] can also oxidise sulphydryl groups on glutathione, leading to depletion of antioxidant defences, and other thiol containing cofactors disrupting various cellular processes and structures. The final link between PD and mitochondrially generated ROS through protein damage comes with the discovery of nitrated and oxidatively damaged misfolded proteins that have strong genetic links with the disease such as α-synuclein, DJ-1, Parkin and PINK1 [46–51] suggesting that these disease-associated proteins are major targets of free-radical damage in sporadic forms of PD.

Lipid peroxidation is another of the main types of cellular damage caused by ROS occurring when ROS react with hydrogen in the lipid leading to the formation of a lipid radical. This radical can then form a further lipid radical via an intermediary by reacting with a hydrogen atom leading to a chain reaction and breakdown of the lipid. In the cell membrane, phospholipids are particularly susceptible to this damage due to their polyunsaturated nature, leading to damage to cell and organelle membranes and severe cellular dysfunction. There have been strong links between increased lipid peroxidation and PD with increased levels shown to be present and cause cell death in the nigral cells of PD patients [36, 37], suggesting a role for it in the mechanisms of neuronal death.

All of these mechanisms of oxidative stress can feed back to the mitochondria via a series of signalling pathways and cause further exacerbation and mitochondrial dysfunction by damaging mtDNA. In this way, ROS-driven mitochondrial dysfunction acts to propagate itself via a feedback loop leading to accelerated cellular damage and death and contributing to PD.

This oxidative damage could be exacerbated in PD by the discovery of reduced antioxidant defences in patients with the disease. The main line of evidence regards reduced GSH, which has been found to be selectively decreased in the SNpc of patients with PD [52], leading to a decline in cellular capability to inactivate H2O2 and peroxynitrite. This is thought to be an early event in PD pathology since lower levels of reduced GSH in incidental LB disease are of the same magnitude as those found in PD [53]. There have not been consistent reports of changes in the levels of most of the other major antioxidant systems; however, cases of an increase in mitochondrially located MnSOD in PD patients have been described [54, 55]. This supports a link between mitochondrial dysfunction generated superoxide and PD since MnSOD is the main ·O2− scavenging system in mitochondria.

Since there are elevated markers of oxidative damage in the brains of PD patients, including lipid peroxidation [36] protein damage [41, 43], and oxidative DNA damage [36, 37], oxidative stress is an established event in PD. This evidence combined with the PD-like effects of known Complex I inhibitors such as MPTP [56] and rotenone [57] and an increase in the activity of neutralising superoxide dismutase (SOD), particularly the mitochondrially localised MnSOD, being found in neurodegenerative disease patients [58] points to a strong link between ROS, possibly caused by mitochondrial dysfunction and PD.

3.2. Involvement of Iron in Oxidative Stress

Iron may also be involved in the production and propagation of oxidative stress in the mitochondria of DA neurons in PD. Iron is intrinsically linked with mitochondrial function and particularly the brain, since iron is an integral component of all respiratory chain complexes and the uptake of iron by the brain is linked with mitochondrial energy demands [59]. Increased iron levels in the brain have long been associated with PD [60–63] although this increase may be an effect of the normal pathological clearance of iron that occurs during cell death that occurs in PD. More recently, a specific increase in intracellular iron has been observed in SNpc neurones in PD patients [46] suggesting an increase in the cellular accumulation of iron in the disease. Cellular iron normally enters into neurones via the transferrin receptor system and evidence suggests that there is a reduction of this system in PD [64, 65] although this may relate more to the loss of SNpc neurones in PD [47]. This iron may also be taken up into the mitochondria in the SNpc via the transferrin receptor 2 and increased levels of ferritin have been reported in the mitochondria of SNpc DA neurons of PD patients and rats treated with rotenone [48]. ROS with a low oxidative potential, like ·O2− generated via dysfunction of oxidative phosphorylation, can increase the release of reactive ferrous iron from this ferritin so leading to the creation of more ROS via the Fenton reaction [49] and increasing oxidative stress and cell damage. The evidence that abnormal iron homeostasis is present in PD is clear; however, the role of iron in PD as either an initiator or a consequence of pathology remains to be elucidated.

4. Involvement of Ca2+ in Mitochondrial Dysfunction and PD

4.1. Excitotoxicity

The cellular damage caused by electron transfer chain inhibition may contribute to neuronal excitotoxicity exacerbating neurotoxicity in PD. Several mechanisms for excitotoxicity in neurodegenerative conditions have been proposed [50, 51]. Excitotoxicity occurs when depolarisation of the neuronal cell membrane from −90 mV to between −60 and −30 mV leads to a decrease in the magnesium blockade of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors. This, in turn, leads to NMDA receptor activation by latent levels of glutamate and causes an intracellular Ca2+ accumulation. This increase in Ca2+ is then thought to cause neurotoxicity by two main mechanisms. Firstly, Ca2+ causes an increase in intracellular NO via activation of nitric oxide synthase (NOS). The excess of NO in the cell can react with ·O2− to form peroxynitrite [66], which can cause cell death by mechanisms similar to those caused by ROS and mentioned above. Besides the peroxynitrite, NO itself can lead to cell damage via nitrosylation of various proteins.

A second mechanism driven by intracellular Ca2+ increase causes toxicity in DA neurons by acting on mitochondria themselves. The Ca2+ influx is extensively accumulated in the mitochondria and leads to effects on mitochondrial membrane potential and ATP synthesis as well as generation of ROS [67] contributing to the oxidative damage discussed above. This also all feeds back causing further malfunction of the cell's Ca2+ homeostasis and additional cellular damage.

Mitochondrial dysfunction can lead to excitotoxicity and cause a reduction in cellular ATP levels, an increase in cellular Ca2+, or a combination of both [23]. Inhibition of Complex I, and consequently ATP generation, lowers intracellular ATP, leading to partial neuronal depolarisation, due to a reduction in the activity of Na+/K+-ATPase. The Na+/K+-ATPase acts to maintain the resting membrane potential of the cell. A reduction in ATP levels will compromise this function leading to depolarisation and, therefore, excitotoxicity via over activation of NMDA receptors. Intracellular Ca2+ can be increased by two methods, that is, either directly by mitochondrial impairment or by over activity of NMDA receptors. Mitochondria can take up Ca2+ from the cytosol via an uniporter transporter or a transient “rapid mode”, both of which rely on the mitochondrial membrane potential, reviewed by [68]. The ROS generated by mitochondrial respiratory chain dysfunction can damage the mitochondrial membranes and disrupt this mechanism of Ca2+ uptake and storage, thereby raising intracellular Ca2+ levels and exacerbating the excitotoxicity. Sherer et al. showed that this could be a viable mechanism for cell death in PD by inhibiting Complex I in SH-SY5Y cells and showing a disruption in the mitochondrial membrane potential leading to an increased susceptibility to calcium overload [69]. It has also been shown that there is an increase in glutamate activity linked to excitotoxicity in the SNpc of mice treated with the Parkinsonian toxin MPTP, which may be linked to apoptosis and autophagy [70]. This evidence suggests that mitochondrially derived or driven excitotoxicity could be a major contributory factor in PD.

4.2. Nonexcitotoxic Involvement of Ca2+

Further to being integrally involved in mitochondrially generated excitotoxic cell death in PD, Ca2+ has been implicated in other mechanisms of cell death in the disease that may involve compromise of the role of mitochondria as one of the major intracellular Ca2+ stores. Sheehan et al. reported that mitochondria from PD patients showed lower sequestration of calcium than age-matched controls suggesting a role for Ca2+ homeostasis dysfunction in PD [71]. This would lead to higher intracellular Ca2+ levels, which has been shown to amplify free-radical production [72] and, therefore, an increase in ROS. An increase in cytosolic Ca2+ due to mitochondrial dysfunction has also been suggested to activate calpains and so raise levels of toxic α-synuclein proposing another link with PD [73], a discovery supported by the protective effect of calpain inhibition in an MPTP model of PD [74].

A role for Ca2+ and mitochondria has also been suggested in a mechanism of increased susceptibility to cell death specific to SNpc DA neurons and, therefore, relevant for PD. SNpc DA neurons are atypical in the brain in that they have self-generated pacemaker activity [75] mediated by Cav1.3, a rare L-type Ca2+ channel [60]. This activity means that that the Cav1.3 channels are open for a higher proportion of time than Ca2+ channels in other neurons leading to an increased ATP usage in the cells to pump Ca2+ across the membrane up steep concentration gradients [61]. This elevated need for ATP would lead to an increase in the activity of the electron transport chain, therefore increasing ROS production so exacerbating any mitochondrial dysfunction and making SNpc DA neurons more prone to cell death.

5. Dopamine Metabolism and MitochondrialDysfunction in PD

Dopamine metabolism generated oxidative stress has long been implicated in PD [40]. However, more recently, it has been suggested that ROS or reactive quinones produced by oxidation of dopamine, either spontaneously or by monoamine oxidase (MAO), may have a inhibitory effect on the proteins of the mitochondrial respiration chain [76–78]. Khan et al. showed that dopamine inhibits Complexes I and IV, most probably through the actions of the dopamine-generated quinones rather than through ROS [62]. MAO-A is bound to the outer mitochondrial membrane and can oxidise dopamine to form the metabolite 3,4 dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC), which can itself, or through oxidation to quinones, locally inhibit Complexes I and IV [78, 79] although a contradictory report suggests dopamine but not DOPAC inhibits the electron transport chain [63]. A recent study has shown that dopamine itself, rather than any oxidation products can directly inhibit Complex I [80] however, more work would need to be carried out to confirm this as there is no corroborating evidence.

These links between mitochondrial dysfunction and dopamine are supported by reports that the PD neurotoxins and Complex I inhibitors MPTP and rotenone increase dopamine oxidation and turnover [64, 65] although whether this is indirectly due to the ROS generating effects of the toxins is not clear. This hypothesis could offer an explanation as to why DA are more susceptible than other neurons to toxin or mutation mediated mitochondrial dysfunction PD, as they are already under a higher level of oxidative stress due to dopamine metabolism generated electron transfer chain inhibition.

6. Genetic Links between Mitochondrial Dysfunction and PD

Studies of families who suffer from inherited forms of PD have identified a number of genes encoding mitochondrial proteins or proteins implicated in mitochondrial dysfunction [46–51, 81].

6.1. α-Synuclein

The α-synuclein gene encodes a small protein of the synuclein family that is localised to nerve terminals although the physiological function of α-synuclein is unclear. The first link between α-synuclein and PD came with the discovery of mutations in the α-synuclein gene in PD patients [48, 49, 51]. This evidence was supported by the discovery that aggregates of α-synuclein are the major components of LBs [82]. Although there are many theories on the mechanism by which mutant α-synuclein causes neuronal cell death in PD, it has recently been reported that there is an association between α-synuclein and mitochondrial dysfunction [83, 84]. Mutant α-synuclein is targeted to and accumulates in the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM) and can cause Complex I impairment and an increase in ROS, possibly leading to cell death [85].

6.2. Parkin, PINK1, and DJ-1

Parkin, PTEN-induced putative kinase 1 (PINK1), and DJ-1 are genes that code for proteins that are crucially involved in mitochondrial function and resistance to oxidative stress and have been linked with PD. The Parkin gene encodes an E3 ubiquitin ligase involved in the ubiquitin-proteasomal system, marking proteins for degradation by the proteasome. Mutations in Parkin have been linked to autosomal recessive juvenile parkinsonism [86]. Parkin has also been shown to interact with and promote degradation of α-synuclein [87]; therefore, a loss of function Parkin mutation could contribute to the α-synuclein driven cell death mentioned above. It has been suggested that Parkin may also be involved in mitochondrial function and protection from mitochondrially generated ROS. Recent work in Parkin null mice has shown a reduction in subunits of Complex I and IV and reduced function in the mitochondrial respiratory chain along with increased oxidative stress in brain tissue [88]. This is supported by reduced mitochondrial Complex I activity in Parkinsonian patients with Parkin mutations [89] and the increased age-dependent or rotenone (a Complex I inhibitory toxin) induced DA neuronal degeneration and mitochondrial abnormalities in Parkin mutant drosophila [90]. Moreover, a recently generated zebrafish model of Parkin deficiency showed increased sensitivity of Parkin mutants to proteotoxic stress with no manifestation of dopaminergic neuron loss or affected mitochondrial morphology or function [91].

PTEN-induced putative kinase 1 (PINK1) is a serine/threonine kinase located in the inner mitochondrial membrane [92] which functions to protect neurons against various types of cell stress. Mutations in PINK1 are found to be associated with a autosomal recessive form of PD [93]. This pathogenesis may be associated with the loss of kinase activity as PINK1 is known to protect against cell death only if the kinase function is intact [94]. Several independent groups reported a role of PINK1 in mitochondrial integrity by regulating the mitochondrial fission machinery [95], which might have an impact on dopaminergic synapses and contribute to DA neuron degeneration [96–98]. Knockdown of PINK1 has been shown to induce mitochondrial oxidative stress, mitochondrial fragmentation, and autophagy and dysregulate calcium homeostasis in SH-SY5Y cells [76, 98]. Moreover, there is evidence of interplay between PINK1 and Parkin, since Parkin can reduce mitochondrial dysfunction caused by down-regulation of PINK1 [77]. Furthermore, it has been shown recently that both PINK1 and Parkin are involved in removal of damaged mitochondria. The proposed model suggests that in response to mitochondrial depolarization PINK1 accumulates on the mitochondrial membrane and recruits Parkin to promote mitophagy [78, 79]. Therefore, the pathology of mutant PINK1 and/or Parkin in Parkinsonism may arise from the inability to remove dysfunctional mitochondria [99].

The DJ-1 gene encodes a widely expressed protein found in neurons and glia in all central nervous system (CNS) regions [100]. Bonifati first identified an association between DJ-1 and autosomal recessive early-onset PD [46, 101], with numerous further familial mutations in DJ-1 being identified [102]. Reports have shown that DJ-1 is present in mitochondria and protects against oxidative neuronal death [103], DJ-1 deficient mice are more susceptible to MPTP [81] and DJ-1 knockdown in a neuroblastoma cell line renders the cells vulnerable to oxidative stress [104]. Finally, a critical role for DJ-1 in mitochondrial function is shown by a rescue effect of DJ-1 on neuronal cell death caused by PINK1 but not Parkin deletion [83]. Moreover, loss of DJ-1 leads to mitochondrial fragmentation, impaired dynamics, induced oxidative stress, and autophagy [84, 105]. In conclusion, DJ-1 protein has been observed to have pleiotropic functions (see [106] for further review), with an antioxidative role to be the most consistent finding. This may provide a link to PD whereby a loss of function mutation of DJ-1 causes an increase in mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative damage leading to nigral neuron cell death.

6.3. Other Nuclear Mutations

Omi/Htra2 is a mitochondrially located stress protective serine protease which has been linked to neurodegeneration [107, 108] with loss of function mutations being seen in some PD patients [109]. Although certain studies report no clear genetic association between the Omi/HtrA2 gene sequence variations and PD [110], there is evidence of mitochondrial pathology caused by loss of the Omi/HtrA2 protein function [111]. Omi/Htra2 has also been shown to have links with Pink1 in protecting against oxidative stress [112] and interacting in a prosurvival pathway [113, 114]. Therefore, mutations in this mitochondrially targeted gene may predispose cells to damage via oxidative stress generated from mitochondrial dysfunction.

Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) is a large (280 kDa) protein with kinase activities. Mutations in LRRK2 were first linked with autosomal dominant PD by Zimprich et al. in 2004 [115] and represents the most significant cause of autosomal dominant PD. LRRK2 has been shown to be localised to the outer mitochondrial membrane [116, 117] providing an association between mutations in this protein in PD and mitochondrial function. LRRK2 has also been shown to be linked with mitochondria by the finding that Drosophila with LRRK2 mutations show increased susceptibility to the Complex I inhibitor and mitochondrial toxin rotenone and increased protection against DA neuron degeneration by the mitochondrially protective protein Parkin [118].

A loss of function mutation in the lysosomal type 5 P-type ATPase, ATP13A2, has been shown to have links with a hereditary form of autosomal recessive early onset PD with dementia [119]. Gitler et al. reported that functional ATP13A2 can protect against α-synuclein overexpression induced toxicity and that knockdown of ATP13A2, enhances α-synuclein misfolding in neuronal models of PD [120]. With α-synuclein shown to be toxic to Complex I [85], loss of function mutations in ATP13A2, and therefore impaired α-synuclein clearance, could be a link to mitochondrial dysfunction in PD.

PLA2G6 is a calcium-independent phospholipase A2 linked to infantile neuroaxonal dystrophy [121] and neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation [101] that has recently been implicated in PD [122, 123]. PLA2G6 have been shown to locate to [124], and have a protective role against oxidative stress in [125], pancreatic β-cell mitochondria providing a possible link between loss of function mutations in this protein and mitochondrial dysfunction in PD. How, for example, PLA2G6 regulates iron, a major mitochondrial cofactor is not clear.

6.4. mtDNA Mutations

Besides nuclear DNA mutations, there have been links between mtDNA mutations and PD. Bender et al. [8] and Kraytsberg et al. [126] showed high levels of mtDNA deletions in neurons in the SNpc of PD sufferers. It has been hypothesised that these pathologic DNA rearrangements are not primary drivers of the disease but may be caused by oxidative stress generated during mitochondrial dysfunction, and this may further exacerbate cellular damage [127]. The mitochondrial transcriptional factor A (TFAM) regulates transcription of mtDNA and was linked to PD by the finding that TFAM knockout mice (MitoPark mice) had reduced mtDNA expression and respiratory chain deficiency in SNpc DA neurons, which lead to a Parkinsonian phenotype [128]. Although some studies showed that TFAM mutations do not significantly increase the risk of PD [129, 130], an investigation into the influence of TFAM variants on PD depending on mtDNA haplogroup found certain variants increased the chances of developing PD [131], suggesting a possible role for mtDNA, in some instances, and respiratory chain dysfunction in PD. Mitochondrial DNA polymerase γ 1 (POLG1) is an enzyme involved in the synthesis and regulation of mtDNA and has been shown to have links with PD, including reduced activity of mitochondrial respiratory chain complexes [132, 133]. The involvement of mutations of this protein in PD suggests a role for dysregulation of mtDNA in mitochondrial dysfunction in the disease. However, whether or not there is a common hereditary role for POLG1 in PD needs further study, since a large-scale study does not support this hypothesis [134] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of mutations and links to mitochondrial dysfunction and PD.

| Mutation | Link to mitochondria | Links with PD |

|---|---|---|

| α-synuclein | Targeted to IMM and causes CI inhibition | (i) Major component of LBs (ii) Mutation linked with PD |

| Parkin | Suggested role in mitochondrial function and antioxidant protection | Mutation linked to autosomal recessive juvenile PD |

| PINK1 | Interaction with Parkin | Loss of kinase mutation linked to familial PD |

| DJ-1 | (i) Antioxidant present in mitochondria (ii) Rescues mitochondria from PINK1 deletion |

Mutation linked with numerous cases of familial PD |

| Omi/Hrta2 | (i) Mitochondrial location (ii) Interaction with PINK1 |

Loss of function mutations found in PD patients |

| LRRK2 | (i) Protects against mitochondrial CI toxin rotenone (ii) Increases Parkin mediated cell protection (iii) Located in outer mitochondrial membrane |

Mutation linked with autosomal dominant PD |

| ATP13A2 | Leads to lysosomal dysfunction and build up of α-synuclein which is toxic to CI | Mutation linked with hereditary form of PD |

| PLA2G6 | (i) Located in mitochondria (ii) Protect mitochondria against oxidative stress |

Mutations linked to neurodegeneration and recently PD |

| TFAM | (i) Regulates transcription of mtDNA (ii) Knockout mouse has respiratory chain deficiency |

(i) Knockout mouse develops PD phenotype (ii) Mutations in some variants give increased risk of PD |

| POLG1 | (i) Involved in the synthesis and regulation of mtDNA (ii) Linked to respiratory chain deficiency in PD |

Mutation linked with PD |

7. Mitochondria and Lewy Body Formation

The histological hallmark of PD is the presence of proteinaceous intraneuronal inclusions termed Lewy bodies (LBs) along with the presence of Lewy neurites (LNs) within neuronal dendrites and axons [135, 136]. Dysfunction of protein metabolism appears to be an important factor in LB formation and the associated neurodegeneration (see for further review [137]), but the significance of these aggregates is still a subject of debate. It is unclear if LBs are pathogenic and mechanistically cause neuronal death [138] or rather the actual function of LBs is neuroprotective by sequestering unwanted, potentially toxic proteins [139–141]. The latter hypothesis is supported clinically by evidence, particularly from autosomal recessive juvenile Parkinson's disease due to Parkin mutation demonstrating that neurodegeneration can occur without the presence of LBs in both apparently sporadic and familial forms of PD [142, 143]. LBs are also reported in cognitively intact individuals over 65 years [144] although this may indicate a prodromal phase of PD prior to clinical presentation.

LBs are typically found in brainstem nuclei and in limbic and neocortical regions in PD and Dementia with Lewy bodies patients (DLB), and additionally, they can be identified in autonomic ganglia in the periphery [145]. There are two morphological types of LBs: brainstem (classic) and cortical Lewy bodies. Classic Lewy bodies are intracytoplasmic eosinophylic inclusions that consist of a dense core surrounded by a pale halo [135]. They are spherical in shape however, a recent report of Kanazawa et al. showed also convoluted LBs and their continuity with LNs, which may suggest evolution from LNs to LBs [146]. Typically, classic LBs are seen in dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra and noradrenergic neurons of the locus coeruleus although they were originally described in neurons of the basal forebrain [147]. Cortical LBs are less well-defined structures compared to classic LBs and are without the halo and are predominantly located in limbic areas of the brain, such as the amygdala, entorhinal, insular, and cingulate cortices [145]. Ultrastructurally, both classic and cortical LBs are composed of filamentous, insoluble in SDS, material resembling neurofilament [148]. Electron microscope examination of Lewy bodies demonstrates that the core contains dense granular material, whereas the outer halo is composed of radiating filaments of 7–20 nm in diameter [135]. Staging of severity of the pathology of PD and DLB based on the distribution of LBs in the brain have been put forward and are used in the classification of the neuropathology of PD and DLB [149].

Immunohistochemical staining and proteomic analyses have deciphered the complexities of the molecular composition of Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites. α-synuclein [135, 150], ubiquitin [151], and neurofilaments [152] appear to be the major components, with α-synuclein representing the most prominent and consistent marker of LB/LN. More recently triple immunolabeling for these epitopes has revealed a three-layered internal structure of LBs and LNs [146]. These primary molecular constituents are stratified into concentric layers with ubiquitin staining in the center, surrounded by α-synuclein and neurofilament on the periphery, which is consistent with previous observations [153].

A large number of mitochondria have been observed in early-stage LBs [132, 154]. Mitochondrial accumulation has also been found in nigral Lewy and pale bodies (possibly precursors of LBs [133]) and cortical LBs but not in classical LBs in PD and in a mouse 26S proteasomal knockout model [132]. This may suggest direct involvement of mitochondria in early stages of LB formation. According to the aggresome-related model of LB formation, mitochondria may be sequestered to the inclusion bodies in order to facilitate the removal of unwanted proteins (see [140] for extensive review). LBs also contain components of the ubiquitin-proteasome system although unlike functional aggresomes, they fail to degrade abnormal proteins but sequester them to delay neuronal death [153].

Proteomic analysis of mitochondrial protein composition of the substantia nigra of mice treated with MPTP compared to controls showed significant changes in numerous protein expression. Of these proteins, DJ-1 protein levels were significantly increased in the toxin-treated mice and also colocalised with α-synuclein in LB-like inclusions in the remaining nigral neurons. Moreover, DJ-1 was present in the halo of classical LBs in nigral tissue of PD patients [155]. Parkin, PINK1, and Omi/HtrA2 have also been localized to the LBs in cases with PD [156–159]. These proteins have been shown to interact and are also involved in proteasomal functions [160, 161]. Thus, there is a potential link between mitochondrial and proteasomal functions, which may influence α-synuclein biology. The interplay may involve oxidative stress and ATP production [161]; however, a wider impact of these cellular pathologies may be speculated. In addition, α-synuclein has been shown to affect both proteasome and mitochondria [162, 163] therefore, a vicious cycle of mitochondrial and proteasomal dysfunction and α-synuclein aggregation in LBs may exist (see for review [164]).

8. Neurotoxins That Link Mitochondrial Dysfunction and PD

There is extensive evidence that PD can be caused by neurotoxins, specifically MPTP [165], rotenone [166], paraquat [167], diquat [168], and 1-Trichloromethyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-β-carboline (TaClo) [169, 170]. These compounds are thought to act via various mechanisms, but all by causing mitochondrial dysfunction.

8.1. MPTP

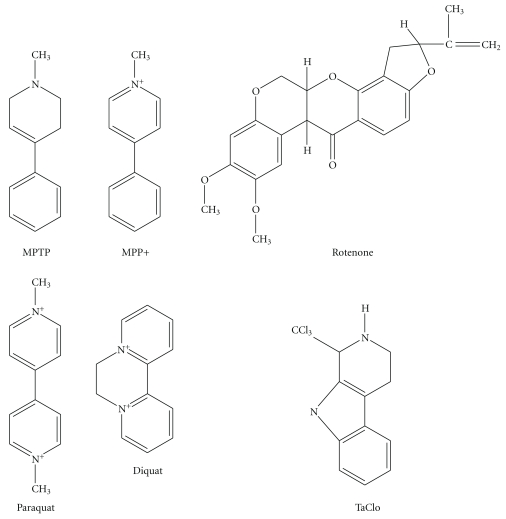

The first toxin that linked mitochondrial Complex I inhibition and PD was MPTP (Figure 3). MPTP is produced as a byproduct of the synthesis of a meperidine analogue with heroin-like properties [171]. Langston et al. described in 1983 that users of meperidine reported striking Parkinsonian symptoms and related this to the presence of MPTP [172]. It has also been shown to closely reproduce the DA degeneration and symptoms of PD in various animal experimental models [173, 174] and has been the most widely used toxin in animal models of PD [175]. MPTP readily crosses the blood brain barrier and is converted to the toxic 1-methyl-4-phenyl-2,3-dihydropyridium ion (MPP+) (Figure 3) by monoamine oxidase B in astrocytes [176] and is then taken up into DA neurons by DAT seen as a reduction in MPTP toxicity in DAT deficient mice [177]. MPP+ is taken up into mitochondria via passive transport due to the large mitochondrial transmembrane gradient [178], where MPP+ inhibits mitochondrial Complex I [179]. This inhibition of Complex I leads to cell death via energy deficits [180], free radical and ROS generation [181], and possibly excitotoxicity [182]. In an MPTP mouse model of PD, α-synuclein is nitrated [183], providing another link between MPTP and PD. However, despite all of the evidence of links between MPTP and PD, there are differences between MPTP models of PD and idiopathic PD with variations in disease progression, an acute onset, and the lack of typical LB formation [184].

Figure 3.

Structures of the PD-linked neurotoxins MPTP/MPP+, Rotenone, Paraquat, Diquat, and TaClo.

8.2. Rotenone

Rotenone (Figure 3) is a widely used pesticide and naturally occurring neurotoxin that has been found to have links to PD [166]. Rotenone is highly lipophilic and able to easily cross the blood brain barrier and enter neuronal cells and intracellular organelles, such as mitochondria, without the aid of transporters. Rotenone specifically blocks the ubiquinone binding site of Complex I, preventing the transport of electrons from Complex I to ubiquinone leading to the release of free radicals into the mitochondrial matrix and ROS formation [34]. This evidence that rotenone is a specific inhibitor of Complex I, which in turn leads to ROS production and oxidative stress, can also cause PD-like behavioural symptoms such as akinesia and rigidity in rats [185]. Rotenone administration has been shown to oxidatively modify DJ-1 and cause α-synuclein aggregation, which are effects linked to PD and localised to the DA neurons of the SNpc [186]. Betarbet et al. reported LB-like ubiquitin and α-synuclein containing cytoplasmic inclusions in the brains of rotenone treated rats [57]. This evidence, taken together, presents a strong link between rotenone exposure, mitochondrial dysfunction and PD. However, there is also evidence to suggest rotenone causes damage to neurons in the striatum but not SNpc [187], suggesting that it may not be an entirely accurate model of PD.

8.3. Paraquat and Diquat

Paraquat and diquat are widely used herbicides shown to have links with PD [167, 168]. They are hydrophilic compounds and, therefore, do not readily cross the blood brain barrier and the mechanism by which they enter the brain is unclear although uptake by a neutral amino acid [188] or polyamine [189] transporters has been suggested. Paraquat and diquat have very similar structures to MPTP and MPP+ (Figure 3), suggesting a similar toxic mechanism. However, unlike rotenone and MPP+, paraquat does not inhibit Complex I and is not taken up by DAT, suggesting an alternative mechanism of cell death [190]. A toxic mechanism is described where paraquat is reduced to the paraquat radical by Complex I causing accelerated lipid peroxidation [191, 192]. An alternative theory whereby paraquat is reduced to the paraquat radical by Complex II has also been reported [193]. A final hypothesis for the formation of the paraquat radical is that paraquat is reduced by NADPH-cytochrome p450 reductase [194] or NADPH-cytochrome c reductase [195] in the cell. Whichever complex or enzyme is involved, the paraquat radical can react with oxygen to form ·O2− and cause oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction [192]. This mechanism of cell death may target the DA neurons specifically because of their constant state of oxidative stress leaving them more vulnerable than other cells. It has also been shown that paraquat can lead to an increase in both α-synuclein levels and aggregation [196]. Although the exact mechanism has yet to be elucidated, mitochondrially derived paraquat radical, combined with its effects on α-synuclein, indicate paraquat toxicity as a possible mitochondrially mediated form of PD. Diquat also generates oxygen radicals in rat brain microsomes [197]; a discovery that, when coupled with its similarity in structure and properties with paraquat, suggests a possible similar role for diquat in mitochondrial dysfunction in PD.

8.4. TaClo

β-carbolines such as TaClo have structures similar to that of MPTP (Figure 3) and may be neurotoxic for DA neurons and lead to a PD-like syndrome [169, 170]. Trichloroethylene (TCE) is an industrial solvent used as a degreasing agent and in dry cleaning. TCE is a major environmental contaminant in the air, the water system and soil, and there is, therefore, exposure at low levels to various groups in the population. It has been discovered that TCE can be converted to the β-carboline TaClo in man [198]. TaClo can cross the blood brain barrier following intraperitoneal injection in the rat [199]. Rausch et al. found that micromolar concentrations of TaClo caused up to 50% cell death in primary C57/B16 mouse DA mesencephalon cultures [200]. This is supported by in vivo studies showing a reduction in DA metabolism [201], with a progressive reduction in locomotion and increase in apomorphine-induced rotations in behavioural tests [202–204] and the discovery of a strong inhibition of mitochondrial Complex I in vitro [205]. Taken together, these data present a strong case for the neurotoxic properties of TaClo against DA neurons. Interestingly, further work showed that N-methyl-TaClo is a more potent inhibitor of mitochondrial Complex I and more neurotoxic than TaClo itself [206]. This evidence suggests that TaClo or another related toxin could cause PD with mitochondrial dysfunction playing a central role. The mechanisms of environmental toxin induced neuronal cell death are summarised in Figure 4.

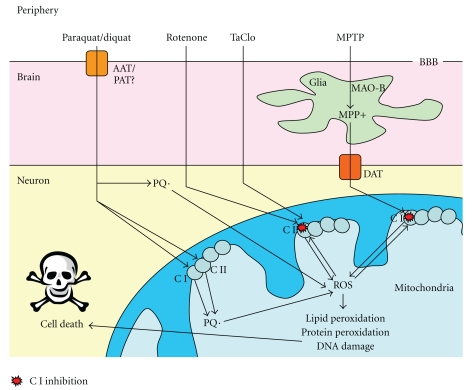

Figure 4.

Mechanisms of mitochondrial dysfunction-mediated cell death generated by neurotoxins: Paraquat crosses the blood brain barrier (BBB) by an as yet unclear mechanism, possibly via an amino acid transporter (AAT)/polyamine transporter (PAT), where it enters the cell and is spontaneously reduced to the paraquat radical PQ· or reduced by Complex I or II (CI or II) and can then form reactive oxygen species (ROS). Rotenone and TaClo enter neurons and can cause CI inhibition which leads to the production of ROS. MPTP enters the brain, where it is converted to MPP+ in glial cells by monoamine oxidase-B (MAO-B) which is transported into neurons by the dopamine transporter (DAT). Once in the cell, MPP+ also causes CI inhibition and generation of ROS. ROS formed by these environmental toxins can then exacerbate the CI inhibition as well as causing lipid and protein peroxidation, DNA damage, and, ultimately, cell death.

However, this evidence of mitochondrial Complex I inhibition leading to neuronal cell death in PD following toxin exposure requires further investigation following the findings of Choi et al. that midbrain neurons without Complex I activity were still susceptible to cell death following rotenone, MPTP, or paraquat treatment [207]. This suggests that mitochondrial dysfunction could either be occurring parallel to another nonmitochondrial cell death mechanism or as a secondary effect driven by some other cellular stress or damage such as toxic protein accumulation due to ubiquitin-proteasome system impairment [208], inflammation [209], or DNA damage [210].

9. Conclusions

This paper demonstrates a considerable body of evidence linking mitochondrial dysfunction, specifically respiratory chain inhibition, with neuronal cell death in the SNpc of PD patients. Many of the mutations related with PD have been shown to involve mitochondrial proteins or proteins linked to mitochondrial dysfunction. Furthermore, neurotoxins that can cause a PD-like syndrome are strong inhibitors of the mitochondrial electron transfer chain (see Figure 5). However, the exact mechanisms of cell death in sporadic PD are still unclear and it has not been conclusively proved whether mitochondrial dysfunction is a primary driver of cellular stress and damage in the disease or a secondary consequence of another insult.

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson's disease: environmental and genetic factors combine to cause mitochondrial dysfunction leading to ROS- and excitotoxic mediated DA cell death and Parkinson's disease.

Further investigation should be carried out into how genes implicated in PD, such as UCH-L1 [211], as well as those mentioned in this paper, may affect mitochondrial function and how mutations in these genes could lead to mitochondrial defects. Although slightly out of the scope of this paper, it would also be of interest to explore how reported crosstalk between mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum [212] may be involved in cell death control, the processing of proteins and Ca2+ homeostasis, and how any deficits in these systems could impact on PD pathology.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledges support from the UK Health Protection Agency. M. Kurzawa is supported by a PhD studentship from the UK Lewy Body Society.

Abbreviations

- AAT:

Amino acid transporter

- ATP:

Adenosine triphosphate

- CNS:

Central nervous system

- DA:

Dopaminergic

- DAT:

Dopamine transporter

- DLB:

Dementia with Lewy bodies

- e−:

Electron

- GSH:

Glutathione

- H+:

Proton

- H2O2:

Hydrogen peroxide

- ILBD:

Incidental Lewy body disease

- LB:

Lewy body

- LN:

Lewy Neurites

- LRRK2:

Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2

- MnSOD:

Manganese superoxide dismutase

- MAO:

Monoamine oxidase

- MPP+:

1-methyl-4phenyl-2,3-dihydropyridium ion

- mtDNA:

Mitochondrial DNA

- MPTP:

1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine

- NMDA:

N-methyl-D-aspartate

- NO·:

Nitric oxide radical

- NOS:

Nitric oxide synthase

- ·O2−:

Superoxide radical

- ·OH:

Hydroxide radical

- PARP:

poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase

- PAT:

Polyamine transporter

- PD:

Parkinson's disease

- POLG1:

Mitochondrial DNA polymerase γ 1

- ROS:

Reactive oxygen species

- SNpc:

Substantia nigra pars compacta

- TaClo:

1-Trichloromethyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-β-carboline

- TCE:

Trichloroethylene

- TFAM:

Mitochondrial transcriptional factor A.

References

- 1.Lees AJ, Hardy J, Revesz T. Parkinson’s disease. The Lancet. 2009;373(9680):2055–2066. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60492-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dickson DW, Braak H, Duda JE, et al. Neuropathological assessment of Parkinson’s disease: refining the diagnostic criteria. The Lancet Neurology. 2009;8(12):1150–1157. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70238-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keeney PM, Xie J, Capaldi RA, Bennett JP. Parkinson’s disease brain mitochondrial complex I has oxidatively damaged subunits and is functionally impaired and misassembled. Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26(19):5256–5264. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0984-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schapira AHV, Cooper JM, Dexter D, Clark JB, Jenner P, Marsden CD. Mitochondrial complex I deficiency in Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1990;54(3):823–827. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb02325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kitada T, Asakawa S, Hattori N, et al. Mutations in the parkin gene cause autosomal recessive juvenile parkinsonism. Nature. 1998;392(6676):605–608. doi: 10.1038/33416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valente EM, Abou-Sleiman PM, Caputo V, et al. Hereditary early-onset Parkinson’s disease caused by mutations in PINK1. Science. 2004;304(5674):1158–1160. doi: 10.1126/science.1096284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonifati V, Rizzu P, Van Baren MJ, et al. Mutations in the DJ-1 gene associated with autosomal recessive early-onset parkinsonism. Science. 2003;299(5604):256–259. doi: 10.1126/science.1077209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bender A, Krishnan KJ, Morris CM, et al. High levels of mitochondrial DNA deletions in substantia nigra neurons in aging and Parkinson disease. Nature Genetics. 2006;38(5):515–517. doi: 10.1038/ng1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frey TG, Mannella CA. The internal structure of mitochondria. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 2000;25(7):319–324. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01609-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson S, Bankier AT, Barrell BG. Sequence and organization of the human mitochondrial genome. Nature. 1981;290(5806):457–465. doi: 10.1038/290457a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang X, Wang X. Cytochrome C-mediated apoptosis. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 2004;73:87–106. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Szabadkai G, Duchen MR. Mitochondria: the hub of cellular Ca2+ signaling. Physiology. 2008;23(2):84–94. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00046.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lill R, Dutkiewicz R, Elsässer HP, et al. Mechanisms of iron-sulfur protein maturation in mitochondria, cytosol and nucleus of eukaryotes. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2006;1763(7):652–667. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giles RE, Blanc H, Cann HM, Wallace aD. C. C. Maternal inheritance of human mitochondrial DNA. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1980;77(11):6715–6719. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.11.6715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen XJ, Butow RA. The organization and inheritance of the mitochondrial genome. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2005;6(11):815–825. doi: 10.1038/nrg1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Finsterer J. Central nervous system manifestations of mitochondrial disorders. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. 2006;114(4):217–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2006.00671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chan DC. Mitochondria: dynamic organelles in disease, aging, and development. Cell. 2006;125(7):1241–1252. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takeshige K, Minakami S. NADH- and NADPH-dependent formation of superoxide anions by bovine heart submitochondrial particles and NADH-ubiquinone reductase preparation. Biochemical Journal. 1979;180(1):129–135. doi: 10.1042/bj1800129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beyer RE. An analysis of the role of coenzyme Q in free radical generation and as an antioxidant. Biochemistry and Cell Biology. 1992;70(6):390–403. doi: 10.1139/o92-061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lass A, Agarwal S, Sohal RS. Mitochondrial ubiquinone homologues, superoxide radical generation, and longevity in different mammalian species. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272(31):19199–19204. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.31.19199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cadenas E, Davies KJA. Mitochondrial free radical generation, oxidative stress, and aging. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2000;29(3-4):222–230. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00317-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schapira AHV, Mann VM, Cooper JM, et al. Anatomic and disease specificity of NADH CoQ reductase (complex I) deficiency in Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1990;55(6):2142–2145. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb05809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sherer TB, Betarbet R, Greenamyre JT. Environment, mitochondria, and Parkinson’s disease. Neuroscientist. 2002;8(3):192–197. doi: 10.1177/1073858402008003004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin MT, Beal MF. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Nature. 2006;443(7113):787–795. doi: 10.1038/nature05292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mizuno Y, Ohta S, Tanaka M, et al. Deficiencies in complex I subunits of the respiratory chain in Parkinson’s disease. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1989;163(3):1450–1455. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)91141-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parker WD, Jr., Parks JK, Swerdlow RH. Complex I deficiency in Parkinson’s disease frontal cortex. Brain Research. 2008;1189(1):215–218. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.10.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haas RH, Nasirian F, Nakano K, et al. Low platelet mitochondrial complex I and complex II/III activity in early untreated Parkinson’s disease. Annals of Neurology. 1995;37(6):714–722. doi: 10.1002/ana.410370604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bindoff LA, Birch-Machin MA, Cartlidge NEF, Parker WD, Turnbull DM. Respiratory chain abnormalities in skeletal muscle from patients with Parkinson’s disease. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 1991;104(2):203–208. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(91)90311-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shinde S, Pasupathy K. Respiratory-chain enzyme activities in isolated mitochondria of lymphocytes from patients with Parkinson’s disease: preliminary study. Neurology India. 2006;54(4):390–393. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.28112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rana M, De Coo I, Diaz F, Smeets H, Moraes CT. An out-of-frame cytochrome b gene deletion from a patient with parkinsonism is associated with impaired complex III assembly and an increase in free radical production. Annals of Neurology. 2000;48(5):774–781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Acín-Pérez R, Bayona-Bafaluy MP, Fernández-Silva P, et al. Respiratory complex III is required to maintain complex I in mammalian mitochondria. Molecular Cell. 2004;13(6):805–815. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00124-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shults CW, Haas RH, Passov D, Beal MF. Coenzyme Q levels correlate with the activities of complexes I and II/III in mitochondria from Parkinsonian and nonparkinsonian subjects. Annals of Neurology. 1997;42(2):261–264. doi: 10.1002/ana.410420221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beal MF, Matthews RT, Tieleman A, Shults CW. Coenzyme Q attenuates the 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6- tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) induced loss of striatal dopamine and dopaminergic axons in aged mice. Brain Research. 1998;783(1):109–114. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01192-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lambert AJ, Brand MD. Inhibitors of the quinone-binding site allow rapid superoxide production from mitochondrial NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I) Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(38):39414–39420. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406576200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cooke MS, Evans MD, Dizdaroglu M, Lunec J. Oxidative DNA damage: mechanisms, mutation, and disease. FASEB Journal. 2003;17(10):1195–1214. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0752rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dexter DT, Carter CJ, Wells FR, et al. Basal lipid peroxidation in substantia nigra is increased in Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1989;52(2):381–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1989.tb09133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dexter D, Carter C, Agid F. Lipid peroxidation as cause of nigral cell death in Parkinson’s disease. Lancet. 1986;2(8507):639–640. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)92471-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Szabó C, Zingarelli B, O’Connor M, Salzman AL. DNA strand breakage, activation of poly(ADP-ribose) synthetase, and cellular energy depletion are involved in the cytotoxicity in macrophages and smooth muscle cells exposed to peroxynitrite. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93(5):1753–1758. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.5.1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Przedborski S, Vila M. MPTP: a review of its mechanisms of neurotoxicity. Clinical Neuroscience Research. 2001;1(6):407–418. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eşrefoğlu M. Cell injury and death: oxidative stress and antioxidant defense system: review. Turkiye Klinikleri Journal of Medical Sciences. 2009;29(6):1660–1676. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Floor E, Wetzel MG. Increased protein oxidation in human substantia nigra pars compacta in comparison with basal ganglia and prefrontal cortex measured with an improved dinitrophenylhydrazine assay. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1998;70(1):268–275. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70010268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reiter CD, Teng RJ, Beckman JS. Superoxide reacts with nitric oxide to nitrate tyrosine at physiological pH via peroxynitrite. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(42):32460–32466. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M910433199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Good PF, Hsu A, Werner P, Perl DP, Warren Olanow C. Protein nitration in Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 1998;57(4):338–342. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199804000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Radi R, Beckman JS, Bush KM, Freeman BA. Peroxynitrite oxidation of sulfhydryls: the cytotoxic potential of superoxide and nitric oxide. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1991;266(7):4244–4250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Armstrong DA, Buchanan JD. Reactions of O−2, H2O2 and other oxidants with sulfhydryl enzymes. Photochemistry and Photobiology. 1978;28(4-5):743–755. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1978.tb07011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oakley AE, Collingwood JF, Dobson J, et al. Individual dopaminergic neurons show raised iron levels in Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2007;68(21):1820–1825. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000262033.01945.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Faucheux BA, Hauw JJ, Agid Y, Hirsch EC. The density of [125I]-transferrin binding sites on perikarya of melanized neurons of the substantia nigra is decreased in Parkinson’s disease. Brain Research. 1997;749(1):170–174. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)01412-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mastroberardino PG, Hoffman EK, Horowitz MP, et al. A novel transferrin/TfR2-mediated mitochondrial iron transport system is disrupted in Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiology of Disease. 2009;34(3):417–431. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Double KL, Maywald M, Schmittel M, Riederer P, Gerlach M. In vitro studies of ferritin iron release and neurotoxicity. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1998;70(6):2492–2499. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70062492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Albin RL, Greenamyre JT. Alternative excitotoxic hypotheses. Neurology. 1992;42(4):733–738. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.4.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Greene JG, Greenamyre JT. Bioenergetics and glutamate excitotoxicity. Progress in Neurobiology. 1996;48(6):613–634. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(96)00006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jenner P, Dexter DT, Sian J, Schapira AHV, Marsden CD. Oxidative stress as a cause of nigral cell death in Parkinson’s disease and incidental Lewy body disease. Annals of Neurology. 1992;32:S82–S87. doi: 10.1002/ana.410320714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jenner P. Altered mitochondrial function, iron metabolism and glutathione levels in Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica, Supplement. 1993;87(146):6–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Saggu H, Cooksey J, Dexter D, et al. A selective increase in particulate superoxide dismutase activity in parkinsonian substantia nigra. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1989;53(3):692–697. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1989.tb11759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yoritaka A, Hattori N, Mori H, Kato K, Mizuno Y. An immunohistochemical study on manganese superoxide dismutase in Parkinson’s disease. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 1997;148(2):181–186. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(96)05339-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Przedborski S, Tieu K, Perier C, Vila M. MPTP as a mitochondrial neurotoxic model of Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Bioenergetics and Biomembranes. 2004;36(4):375–379. doi: 10.1023/B:JOBB.0000041771.66775.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Betarbet R, Sherer TB, MacKenzie G, Garcia-Osuna M, Panov AV, Greenamyre JT. Chronic systemic pesticide exposure reproduces features of Parkinson’s disease. Nature Neuroscience. 2000;3(12):1301–1306. doi: 10.1038/81834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yoshida E, Mokuno K, Aoki SI, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid levels of superoxide dismutases in neurological diseases detected by sensitive enzyme immunoassays. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 1994;124(1):25–31. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(94)90006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mash DC, Pablo J, Flynn DD, Efange SMN, Weiner WJ. Characterization and distribution of transferrin receptors in the rat brain. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1990;55(6):1972–1979. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb05784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Striessnig J, Koschak A, Sinnegger-Brauns MJ, et al. Role of voltage-gated L-type Ca2+ channel isoforms for brain function. Biochemical Society Transactions. 2006;34(5):903–909. doi: 10.1042/BST0340903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Surmeier DJ, Guzman JN, Sanchez-Padilla J. Calcium, cellular aging, and selective neuronal vulnerability in Parkinson’s disease. Cell Calcium. 2010;47(2):175–182. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Khan FH, Sen T, Maiti AK, Jana S, Chatterjee U, Chakrabarti S. Inhibition of rat brain mitochondrial electron transport chain activity by dopamine oxidation products during extended in vitro incubation: implications for Parkinson’s disease. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2005;1741(1-2):65–74. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2005.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jana S, Maiti AK, Bagh MB, et al. Dopamine but not 3,4-dihydroxy phenylacetic acid (DOPAC) inhibits brain respiratory chain activity by autoxidation and mitochondria catalyzed oxidation to quinone products: implications in Parkinson’s disease. Brain Research. 2007;1139(1):195–200. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.09.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lotharius J, O’Malley KL. The Parkinsonism-inducing drug 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium triggers intracellular dopamine oxidation: a novel mechanism of toxicity. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(49):38581–38588. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005385200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Thiffault C, Langston JW, Di Monte DA. Increased striatal dopamine turnover following acute administration of rotenone to mice. Brain Research. 2000;885(2):283–288. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02960-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dawson VL, Dawson TM. Nitric oxide neurotoxicity. Journal of Chemical Neuroanatomy. 1996;10(3-4):179–190. doi: 10.1016/0891-0618(96)00148-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nicholls DG, Budd SL. Neuronal excitotoxicity: the role of mitochondria. BioFactors. 1998;8(3-4):287–299. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520080317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gunter TE, Buntinas L, Sparagna G, Eliseev R, Gunter K. Mitochondrial calcium transport: mechanisms and functions. Cell Calcium. 2000;28(5-6):285–296. doi: 10.1054/ceca.2000.0168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sherer TB, Trimmer PA, Borland K, Parks JK, Bennett JP, Tuttle JB. Chronic reduction in complex I function alters calcium signaling in SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells. Brain Research. 2001;891(1-2):94–105. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)03203-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Meredith GE, Totterdell S, Beales M, Meshul CK. Impaired glutamate homeostasis and programmed cell death in a chronic MPTP mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Experimental Neurology. 2009;219(1):334–340. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sheehan JP, Swerdlow RH, Parker WD, Miller SW, Davis RE, Tuttle JB. Altered calcium homeostasis in cells transformed by mitochondria from individuals with Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1997;68(3):1221–1233. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68031221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dykens JA. Isolated cerebral and cerebellar mitochondria produce free radicals when exposed to elevated Ca+ and Na+: implications for neurodegeneration. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1994;63(2):584–591. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.63020584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Esteves AR, Arduíno DM, Swerdlow RH, Oliveira CR, Cardoso SM. Dysfunctional mitochondria uphold calpain activation: contribution to Parkinson’s disease pathology. Neurobiology of Disease. 2010;37(3):723–730. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Crocker SJ, Smith PD, Jackson-Lewis V, et al. Inhibition of calpains prevents neuronal and behavioral deficits in an MPTP mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23(10):4081–4091. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-10-04081.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Grace AA, Bunney BS. Intracellular and extracellular electrophysiology of nigral dopaminergic neurons. 2. Action potential generating mechanisms and morphologic correlates. Neuroscience. 1983;10(2):317–331. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(83)90136-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gandhi S, Wood-Kaczmar A, Yao Z, et al. PINK1-associated Parkinson’s disease is caused by neuronal vulnerability to calcium-induced cell death. Molecular Cell. 2009;33(5):627–638. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Exner N, Treske B, Paquet D, et al. Loss-of-function of human PINK1 results in mitochondrial pathology and can be rescued by parkin. Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27(45):12413–12418. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0719-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Narendra DP, Jin SM, Tanaka A, et al. PINK1 is selectively stabilized on impaired mitochondria to activate Parkin. PLoS Biology. 2010;8(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000298. Article ID e1000298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Geisler S, Holmström KM, Skujat D, et al. PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy is dependent on VDAC1 and p62/SQSTM1. Nature Cell Biology. 2010;12(2):119–131. doi: 10.1038/ncb2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Brenner-Lavie H, Klein E, Ben-Shachar D. Mitochondrial complex I as a novel target for intraneuronal DA: modulation of respiration in intact cells. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2009;78(1):85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kim RH, Smith PD, Aleyasin H, et al. Hypersensitivity of DJ-1-deficient mice to 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6- tetrahydropyrindine (MPTP) and oxidative stress. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(14):5215–5220. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501282102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Spillantini MG, Crowther RA, Jakes R, Hasegawa M, Goedert M. α-synuclein in filamentous inclusions of Lewy bodies from Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95(11):6469–6473. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hao LY, Giasson BI, Bonini NM. DJ-1 is critical for mitochondrial function and rescues PINK1 loss of function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107(21):9747–9752. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911175107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Irrcher I, Aleyasin H, Seifert EL, et al. Loss of the Parkinson's disease-linked gene DJ-1 perturbs mitochondrial dynamics. Human Molecular Genetics. 2010;19(19):3734–3746. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Devi L, Raghavendran V, Prabhu BM, Avadhani NG, Anandatheerthavarada HK. Mitochondrial import and accumulation of α-synuclein impair complex I in human dopaminergic neuronal cultures and Parkinson disease brain. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283(14):9089–9100. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710012200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kitada T, Asakawa S, Hattori N, et al. Mutations in the parkin gene cause autosomal recessive juvenile parkinsonism. Nature. 1998;392(6676):605–608. doi: 10.1038/33416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kim SEJ, Sung JY, Um JIW, et al. Parkin cleaves intracellular α-synuclein inclusions via the activation of calpain. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(43):41890–41899. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306017200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Palacino JJ, Sagi D, Goldberg MS, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative damage in parkin-deficient mice. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(18):18614–18622. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401135200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Müftüoglu M, Elibol B, Dalmizrak Ö, et al. Mitochondrial complex I and IV activities in leukocytes from patients with parkin mutations. Movement Disorders. 2004;19(5):544–548. doi: 10.1002/mds.10695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wang C, Lu R, Ouyang X, et al. Drosophila overexpressing parkin R275W mutant exhibits dopaminergic neuron degeneration and mitochondrial abnormalities. Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27(32):8563–8570. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0218-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Fett ME, Pilsl A, Paquet D, et al. Parkin is protective against proteotoxic stress in a transgenic zebrafish model. PLoS One. 2010;5(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011783. Article ID e11783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Silvestri L, Caputo V, Bellacchio E, et al. Mitochondrial import and enzymatic activity of PINK1 mutants associated to recessive parkinsonism. Human Molecular Genetics. 2005;14(22):3477–3492. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Valente EM, Abou-Sleiman PM, Caputo V, et al. Hereditary early-onset Parkinson’s disease caused by mutations in PINK1. Science. 2004;304(5674):1158–1160. doi: 10.1126/science.1096284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Petit A, Kawarai T, Paitel E, et al. Wild-type PINK1 prevents basal and induced neuronal apoptosis, a protective effect abrogated by Parkinson disease-related mutations. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280(40):34025–34032. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505143200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hoppins S, Lackner L, Nunnari J. The machines that divide and fuse mitochondria. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 2007;76:751–780. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.071905.090048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Yang Y, Ouyang Y, Yang L, et al. Pink1 regulates mitochondrial dynamics through interaction with the fission/fusion machinery. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105(19):7070–7075. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711845105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Gispert S, Ricciardi F, Kurz A, et al. Parkinson phenotype in aged PINK1-deficient mice is accompanied by progressive mitochondrial dysfunction in absence of neurodegeneration. PLoS One. 2009;4(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005777. Article ID e5777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Dagda RK, Cherra SJ, Kulich SM, Tandon A, Park D, Chu CT. Loss of PINK1 function promotes mitophagy through effects on oxidative stress and mitochondrial fission. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2009;284(20):13843–13855. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808515200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Chu CT. A pivotal role for PINK1 and autophagy in mitochondrial quality control: implications for Parkinson disease. Human Molecular Genetics. 2010;19(1):R28–R37. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq143. Article ID ddq143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bader V, Zhu XR, Lübbert H, Stichel CC. Expression of DJ-1 in the adult mouse CNS. Brain Research. 2005;1041(1):102–111. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Morgan NV, Westaway SK, Morton JEV, et al. PLA2G6, encoding a phospholipase A, is mutated in neurodegenerative disorders with high brain iron. Nature Genetics. 2006;38(7):752–754. doi: 10.1038/ng1826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Van Duijn CM, Dekker MCJ, Bonifati V, et al. PARK7, a novel locus for autosomal recessive early-onset parkinsonism, on chromosome 1p36. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2001;69(3):629–634. doi: 10.1086/322996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Canet-Avilés RM, Wilson MA, Miller DW, et al. The Parkinson’s disease DJ-1 is neuroprotective due to cysteine-sulfinic acid-driven mitochondrial localization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101(24):9103–9108. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402959101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Taira T, Saito Y, Niki T, Iguchi-Ariga SMM, Takahashi K, Ariga H. DJ-1 has a role in antioxidative stress to prevent cell death. EMBO Reports. 2004;5(2):213–218. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Krebiehl G, Ruckerbauer S, Burbulla LF, et al. Reduced basal autophagy and impaired mitochondrial dynamics due to loss of Parkinson’s disease-associated protein DJ-1. PLoS One. 2010;5(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009367. Article ID e9367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Cookson MR. DJ-1, PINK1, and their effects on mitochondrial pathways. Movement Disorders. 2010;25(supplement 1):S27–S31. doi: 10.1002/mds.22713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Jones JM, Datta P, Srinivasula SM, et al. Loss of Omi mitochondrial protease activity causes the neuromuscular disorder of mnd2 mutant mice. Nature. 2003;425(6959):721–727. doi: 10.1038/nature02052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Martins LM, Morrison A, Klupsch K, et al. Neuroprotective role of the reaper-related serine protease HtrA2/Omi revealed by targeted deletion in mice. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2004;24(22):9848–9862. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.22.9848-9862.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Strauss KM, Martins LM, Plun-Favreau H, et al. Loss of function mutations in the gene encoding Omi/HtrA2 in Parkinson’s disease. Human Molecular Genetics. 2005;14(15):2099–2111. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]