Abstract

Background

Stroke is the leading cause of adult disability. Inpatient programs optimize secondary stroke prevention care at the time of hospital discharge, but such care may not be continued following hospital discharge.

Methods

To improve the delivery of secondary stroke preventive services after hospital discharge, we have designed a chronic care model-based program called SUSTAIN (Systemic Use of STroke Averting INterventions). This care intervention includes group clinics, self-management support, report cards, decision support through care guides and protocols, and coordination of ongoing care. The first specific aim is to test via a randomized-controlled trial whether SUSTAIN improves blood pressure control among an analytic sample of 268 patients with a recent stroke or transient ischemic attack discharged from four Los Angeles County public hospitals. Secondary outcomes consist of control of other stroke risk factors, lifestyle habits, medication adherence, patient perceptions of care quality, functional status, and quality of life. A second specific aim is to conduct a cost analysis of SUSTAIN from the perspective of the Los Angeles County Department of Health Services, using direct costs of the intervention, cost equivalents of associated utilization of county system resources, and cost equivalents of the observed and predicted averted vascular events.

Conclusions

If SUSTAIN is effective, we will have the expertise and findings to advocate for its continued support at Los Angeles county hospitals and to disseminate the program to other settings serving indigent, minority populations.

Keywords: stroke, secondary prevention, risk factors, self-management, care coordination

Background

Death and disability are major consequences of stroke, and health care costs related to stroke exceed $74 billion per year in the United States. 1 Of the 795,000 strokes in the United States that occur each year, approximately 23% are secondary strokes. 1 The occurrence of a stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) is the strongest predictor of a repeat event. 2 The overwhelming majority of strokes per year could be prevented by better control of modifiable risk factors such as hypertension. 2

Quality improvement programs have focused on the initiation of secondary stroke prevention measures in the inpatient setting. 3, 4 However, the use of evidence-based therapies for secondary stroke prevention over the long-term remains inadequate. 5-7 Clinical inertia has been cited as a barrier that prevents titration of appropriate medications to adequate levels. 8

The need to improve stroke prevention care is especially pressing among minority populations. 9 The incidence of stroke among African-Americans and Mexican Americans is higher than non-Hispanic whites. 1 The prevalence of stroke among Latinos in Los Angeles County is elevated reflecting an excessive burden of risk factors. 10 The awareness and control of risk factors are poor among African-American and Mexican-American stroke survivors.11 A systematic review showed that minorities are less likely to receive appropriate stroke preventive services. 9 However, only a few stroke prevention programs specifically target stroke survivors from minority communities. 12

Conceptual Model

Medical care for chronic diseases including stroke is suboptimal. 13 To address this problem, the Chronic Care Model (CCM) has been proposed as a guide to design interventions to improve complex care for patients with chronic disease. 14 The six CCM components are self-management support, clinical information systems, delivery system redesign, decision support, health care organization, and community resources. Most CCM-based interventions have shown improvement of a care process or outcome measure and reduction of health care costs as a result. 14, 15

Group clinics for patients with a shared disease are based on the CCM component of delivery system redesign. Group clinics (also called “cluster visits” or “chronic care clinics”) contain elements of both a support group and a subspecialty clinic. Studies on group clinics have reported positive health outcomes and reduced costs. 16-18 Group clinics have been implemented in care venues serving the uninsured. 19 Group clinics may be particularly effective when patients share a social connection, such as patients with the same ethnicity. 20

Coordination of patient care in an increasingly complex health care system is also based on the CCM component of delivery system redesign. Analyses of this component frequently show significantly improved access to care and decreased hospitalizations. 21

Another CCM component consists of supporting patient self-management to improve self-efficacy, the confidence in one's ability to behave in a way that produces the desired outcome. 22, 23 A systematic review of self-management programs among patients with diabetes, asthma, and hypertension found improvements in relevant physiologic outcomes. 23

In this study we have crafted an outpatient care intervention called SUSTAIN (Systemic Use of STroke Averting INterventions) that uniquely adapts the principles of a successful in-hospital stroke prevention program3 along with CCM components. Specific components in this intervention include group clinics, patient self-management, and care coordination and delivery of stroke prevention care by a trained, licensed independent care provider, either a nurse practitioner (NP) or physician assistant (PA). The target population is persons admitted to Los Angeles county hospitals with a recent ischemic cerebrovascular event (stroke or TIA). Based on an analytic size of 268 patients, we will evaluate the efficacy of SUSTAIN in controlling blood pressure via a randomized controlled trial (RCT). Finally, we will also conduct a cost analysis of SUSTAIN from the perspective of the Los Angeles County Department of Health Services (LAC-DHS). Safety net institutions may not have the resources to support care programs on the basis of health improvements alone; they also need to justify such programs on the basis of costs. Unless a care program is shown to have cost savings or be cost neutral, scarce resources for supporting a new care program comes at the expense of supporting another care program.

Methods

Setting, population, and subjects

The setting of this study is all four county hospitals that anchor care for patients in the Los Angeles County public healthcare system (LAC), which serves the largest, most ethnically diverse county in the United States. This system serves more than 10 million residents and provides healthcare to 700,000 people every year. According to LAC administrative databases, more than 50% of patients use a language other than English as their primary language and 63% of outpatients are uninsured (personal communication: Jeff Guterman). Institutional Review Board approval was obtained at each of the four county hospitals.

Potential subjects are identified through outpatient clinics, admission diagnosis logs, and the stroke Inpatient Clinical Pathways (ICP) implemented at LAC. The ICP prompts inpatient physicians to obtain verbal consent for the research assistant (RA) to meet with the patient, and if obtained, to notify the research team. The RA determines if the patient meets eligibility criteria for enrollment. If patients decline participation in the RCT, the RA requests permission to record their demographic information for generating enrollment propensity weights. Inclusion criteria include a TIA or ischemic stroke within the past 90 days and a systolic blood pressure (SBP) greater than 120 mm Hg. Participants must be English-speaking or Spanish-speaking. Persons with hemorrhagic stroke are excluded because their high short-term mortality rate would lead to high attrition rates. 1 Patients are excluded if the research team believes that they will be unable to actively participate in group clinic settings, such as persons with severe global disability. Persons with language (aphasia) or cognitive difficulties are eligible as long as they can communicate that they understand the study during the informed consent process.

For eligible subjects who consent to the study, the RA administers the baseline survey. After administering the baseline survey, the RA uses a centralized call number to obtain the randomization assignment for the subject. A statistical programmer, who has no contact with subjects, keeps randomizations lists that were generated before the RCT began and will inform the RA about the assignment of the subject during the telephone call. These lists have an allocation ratio of 1:1, a block size of 4, and are stratified by site and preferred language of the subject. To ensure that subjects randomized to the usual care arm receive some attention about stroke, they are given the AHA brochure “Controlling Your Risk Factors: Our Guide to reducing your risk of heart attack and stroke.” We anticipate that the impact of this type of passive education is small.

Subjects randomized to the intervention arm of SUSTAIN are offered the same usual care that is offered to subjects randomized to the control arm of SUSTAIN as well as the usual care that is offered to patients not participating in the RCT. Usual care for a patient with a recent stroke or TIA in LAC consists of at least one scheduled appointment to the outpatient neurology clinic, followed by a plan to rapidly transition care to a primary care provider. Patients without an existing primary care provider are given instructions on how to obtain one affiliated with LAC.

Intervention Staffing

The intervention care managers are bilingual NPs or PAs. An RA assists each care manager in implementing the intervention by scheduling patients for regular and group visits, and preparing for such visits.

A SUSTAIN Task Force reviews the design of the intervention, recommends local adaptations to facilitate implementation at each site, and assesses the extent of implementation. It includes the site Principal Investigators (PIs) at each of the four county hospitals and representatives from three community organizations whose missions match our research team's goals of reducing the risk of stroke in underserved minority communities of Los Angeles: the American Heart Association (AHA), Partners in Care Foundation, and Healthy African-American Families.

Group clinics

Each subject randomized to SUSTAIN is scheduled to attend group clinics at 2, 5, and 10 months after enrollment (see Figure 1). Separate group clinics are scheduled for subjects who speak English or Spanish. The first group clinic consists of education about stroke warning signs, stroke risk factors, medications, and community resources. The second group clinic consists of strategies to enhance self-management of their disease, such as adopting healthy lifestyle habits in diet and physical activity. At the third group clinic, the care manager reinforces content presented at prior group clinics. Following each group clinic, there are brief one-on-one sessions with the care manager to individualize and reinforce content presented in the group session and problem solve with subjects facing unique challenges with adhering to recommendations.

Figure 1. Design of RCT and schedule of key activities among persons randomized to the SUSTAIN intervention.

Individual clinic and scheduled phone calls to coordinate care

Subjects in the SUSTAIN intervention are also scheduled to a regular clinic with the care manager at 1 month and 7 months after enrollment (see Figure 1). These sessions reinforce content discussed at SUSTAIN group sessions and will help coordinate outpatient stroke care delivery. In addition, the care manager schedules telephone care coordination calls starting at one week after hospital discharge, and between group clinics and individualized visits. Protocols on care coordination are followed if a problem is identified, such as a missed appointment or prescription refill.

Self-management tools

During individualized sessions, subjects are given a customized report card on their current versus optimal control of key stroke risk factors. Subjects review the report card and are instructed to bring a blank report card to future primary care provider visits so that these clinicians can be actively engaged in delivering stroke preventive services.

Subjects are provided blood pressure monitors (Omron HEM-711 DLX) for use at home. This model has been validated according to international blood pressure protocols. 24 In focus groups that we conducted of persons with recent stroke or TIA in this population, participants preferred this model over others because it had a pre-formed cuff, making it easier to use. Subjects are trained on how to use this equipment, and the care manager follows home blood pressure measurements at telephone calls and individual visits.

Care protocols and health information technology to support care management

The care managers follow care protocols written by the Task Force and research team to address stroke prevention services. Medication algorithms are based on AHA guidelines, 2 and the Preventing Occurrence of Thrombotic Events through Co-ordinated Treatment (PROTECT) protocol, an inpatient program for initiating stroke preventive medications. 3 The protocols also address tobacco cessation, physical activity, depression, and medication adherence. These protocols are implemented in an existing health information technology/chronic disease registry program by LAC-DHS for diabetes, heart failure, and asthma. 25 This health information technology infrastructure is also used to capture SUSTAIN data and prompt care managers on the protocol. These protocols remind the care manager whether subjects have achieved goal physiologic measurements and when telephone calls, scheduled visits, pharmacy refills, and laboratory testing are due. By building on existing infrastructure, we anticipate enhanced sustainability of SUSTAIN at LAC beyond the funding period.

Caregivers or family members are encouraged to participate in all aspects of the care intervention because they may be most responsible for medication adherence and improving lifestyle habits.

Outcome Measures

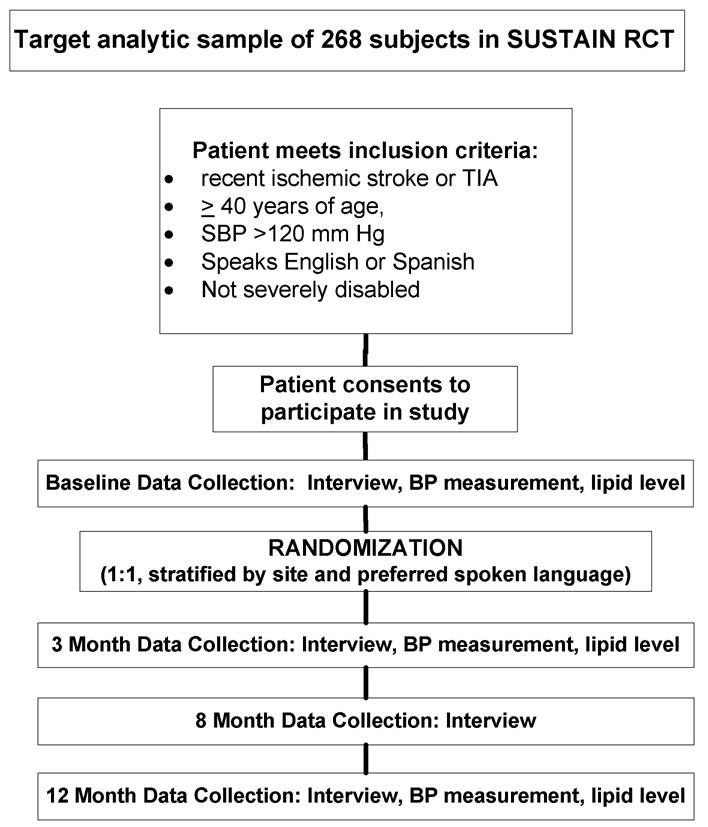

The outcome measures are listed in the Table. An RA who is blinded to the randomization arm collects study outcomes on all enrollees. Interviews are conducted in person at baseline, 3 months, and 12 months, and an abbreviated telephone interview occurs at 8 months (see Figure 2). The risk factors assessed in this study include blood pressure, cholesterol level, smoking status, and physical activity levels. 2 At each in-person assessment, two blood pressures are obtained and averaged from each subject using the Omron HEM-907XL 26 following a standardized protocol provided by the manufacturer about cuff size, cuff application, body position, and time intervals when taking a measurement. 27 In-person assessment of stroke severity is performed using the National Institute of Health Stroke Scale28 and assessment of disability by the modified Rankin scale. 29 A large set of potential mediators of risk factor control are also collected. Assessment of stroke knowledge has been adapted from a prior survey administered periodically to a large metropolitan area. 30, 31 Assessment of patient perceptions of stroke care quality was adapted from the Consumer Assessment of Health Plans Study. 32 Self-report medication adherence is assessed through recommended scales 33 and barriers to adherence are assessed through the Morisky scale. 34 Medication adherence is also assessed through county databases containing pharmacy refill information. 35 Other potential mediators include access to care, depression, competing needs, social support, and life chaos. 36-39 We also collect sociodemographic data, insurance status, and measures of acculturation. 40 Subjects are paid up to $115 for collection of outcome measures across all timepoints.

Table. Data collected to evaluate SUSTAIN.

| Primary Outcome |

| Systolic blood pressure |

| Secondary Outcomes |

| Low-density lipoprotein level |

| Smoking status |

| Physical activity level |

| Health care costs |

| Potential mediators of outcomes |

| Demographics |

| Insurance status |

| Medical history |

| Stroke severity (NIH Stroke Scale), disability (Rankin) |

| Patient perceptions of quality of stroke preventive care |

| Knowledge about stroke signs and risk factors |

| Medication adherence |

| Competing needs, access to care, chaos, social support |

| Depression screener |

| Short Form 6-D |

| Health care utilization (such as hospitalizations) |

Figure 2. Enrollment of subjects and schedule for collecting evaluation data.

To perform cost analyses, we will first assess the direct costs of SUSTAIN by calculating the start-up costs (including time for the PI to train SUSTAIN staff and the training time required by the staff to become proficient in carrying out their duties) and maintenance costs (including time for the care manager and RA to execute the intervention care management activities, clinic room charges, printing of materials, and telephone costs for care coordination). Associated costs based on utilization of county resources by subjects will be determined by a survey 41 and a query of the county administrative database. Utilization includes the total number of hospital-days, emergency room visits, outpatient visits, and prescription medications and laboratory tests relevant to stroke prevention. We will obtain the fees paid by LAC to compute cost equivalents. We will also administer the SF-6D to calculate quality of life utilities to enable a full cost-effectiveness analysis, if indicated. 42 Future costs will be predicted by modeling the number of future vascular events based on the net difference in BP levels found in the two arms of the study.

Sample size and statistical power

Our sample size calculation and power analyses are based on the primary outcome of SBP, the premier modifiable risk factor for stroke. The most well-known national guideline on blood pressure control defines normal SBP as less than 120 mm Hg. 43 Large meta-analyses of observational and RCTs have found clinical benefit for having a SBP as low as 115 mm Hg. 44, 45 In addition, a large RCT of SBP-lowering for secondary stroke prevention found similar health benefits for persons with baseline hypertension and for persons with baseline normotension. 46 Based on available data from one of the four hospitals from which the data collection will be conducted, the mean and standard deviation of SBP for persons with stroke with SBP >120mm Hg are 148 and 20, respectively (personal communication, Bruce Ovbiagele). Using a type I error of 0.05, a type II error of 0.1 (or power of 90%), and a two-sided test, 132 subjects in each treatment arm (or 264 subjects in total) will enable detection of a difference of 8mm Hg in SBP, which corresponds to an effect size of 0.5, between the two treatment arms. This difference of 8mm Hg in SBP between the two treatments is smaller than the 10 mm Hg threshold cited in the guideline, and thus we have sufficient statistical power with the estimated sample size to detect clinical benefit. An alternative outcome measure to SBP is recurrent stroke, but our sample size is not large enough to detect differences in recurrent stroke over 12-months of follow-up.

Enrollment sample size

Although we will facilitate the retention of subjects in the RCT as much as possible, the retention rates in disadvantaged populations are likely lower than in other settings. In addition, we need to account for attrition due to mortality. The one-year all-cause mortality rate after stroke is 15-20% for persons aged 45-69, and 20-25% for persons aged 70 and above. 1 Using a conservative estimate of a 65% retention rate to account for these factors, the target number for enrollment is 410.

We plan to enroll study participants over 24 months. Based on discharge diagnoses of stroke and TIA in the four LAC hospitals in 2007, we estimate that there will be 1608 admissions for stroke or TIA in the 24-month enrollment period (see Figure 2). Based on available data from one of the four hospitals, we estimate that about 2/3 of all patients with new stroke or TIA will have a SBP greater than 120 mm Hg. Even after excluding persons with SBP <120 mm Hg, we still anticipate 964 hospitalized patients with stroke or TIA will be eligible for this study during the enrollment period, a number considerably larger than the target enrollment of 410 patients. We will also be enrolling patients from the outpatient clinic.

Analysis

The distributions of baseline characteristics between the SUSTAIN intervention and usual care groups will be compared. Continuous measures will be compared using the two group t-test, and ordinal or non Gaussian continuous variables will be compared using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Nominal categorical variables will be compared using Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test.

Enrollment propensity weights will be used to analyze how the tendency to participate in the RCT impacts study outcomes. Enrollment weights based on a logistic regression model will be calculated using demographic data collected from eligible non-participants. If needed, attrition weights will be determined from logistic regression models using demographic data on participants who disenrolled from the study. These two weights will be combined to form an overall analytic weight, using the inverse of the product of the probabilities of participation. Both the raw rate and the rate adjusted by the analytic weight will be compared between SUSTAIN and usual care arms.

Intention to treat analyses on all primary and secondary outcomes will be conducted using ordinal logistic or multiple linear regression models. With outcome assessments collected at multiple times (baseline, 3 motnhs, 8 months, and 12 months), repeated measures mixed effects models will be used to estimate population effects, as well as individual variation over time. The primary outcome of systolic blood pressure will be analyzed as a continuous variable. In sensitivity analyses, it will also be analyzed as a dichotomous variable using 120 mm Hg and 140 mm Hg as cutoffs. Intervention status will be a primary independent variable used in all models. We will compare study outcomes between the control and intervention groups both with and without adjusting for potential covariates associated with the outcome measure. To check the fidelity (uptake) of the SUSTAIN intervention, we will also analyze attendance at SUSTAIN clinics and the number of telephone coordination of care calls made during the one year care management follow-up. We do not expect differences in mortality rates between randomization arms during the short time period that subjects are followed in this study. However, if differential mortality rates between the two arms exist, we will analyze it similar to other missing data (determine if it is missing at random or missing not at random, etc.), and perform sensitivity analyses and imputation methods to determine if missing outcomes data due to deaths changes the results from unadjusted analysis.

We will examine the distribution of costs to determine whether the data need to be transformed and whether two-part modeling is required to account for subjects with zero expenditures. The first cost analyses will compare the direct costs of SUSTAIN plus the associated costs for utilization among subjects in the intervention arm versus the associated costs of utilization among subjects in the usual care arm during the one-year period subjects were enrolled in the RCT after randomization. The second cost analyses will extend the above analysis beyond the one-year period to include all available data (potentially more than 3 years for the first subjects enrolled in the study). The third set of cost analyses will extend the above analyses to include future costs based on predicted risk of vascular events.

Significance, sustainability, and dissemination

SUSTAIN is designed to be implemented in resource-constrained settings for improving stroke prevention in vulnerable communities and reducing disparities in stroke care. It is designed to improve adherence to guideline-recommended care after hospital discharge to the outpatient setting, using CCM-based components in a NP/PA-coordinated approach.

We have proposed a series of analyses necessary for decision-makers to determine whether to support the SUSTAIN intervention in LAC after the funding period. As part of the Task Force, the site PIs will have been involved in implementing the SUSTAIN program and are in a position to advocate for its continuation. In addition, the research team and the AHA representative will update county administrators on developments throughout the award period. When we have completed this RCT, we plan to make the products from SUSTAIN available to the research and public health community.

Limitations

In this study, we are randomizing patients instead of clusters such as by site because it is the most statistically efficient method for demonstrating efficacy and thus would require the smallest sample size. 47 Cluster randomization is appropriate when the threat of contamination is high, 48 but we believe that the threat of contamination is small in this study. Although a primary care provider could potentially manage subjects in both randomization arms of SUSTAIN, most of the care interventions in SUSTAIN will be conducted by the care manager, and this person will not be managing subjects randomized to usual care. In addition, given the large number of primary care providers, there will only be a few primary care providers who will also manage patients in both arms of the study.

Two recent UK care interventions - Stop Stroke and phase I of EXPRESS did not show improvement in delivery of stroke preventive services. 49, 50 The interventions in these two studies included issuing stroke care recommendations to primary care. However, in phase II of EXPRESS, treatments could be directly initiated by the implementation team, and this was shown to be effective. 50 The SUSTAIN intervention consists of care managers who are supported by tools such as medication algorithms and tracking registries to not only form treatment recommendations but who also possess the clinical privileges to directly implement the BP guidelines and other risk factor recommendations.

Summary

Persons with a recent stroke or TIA are at increased risk of a future stroke. Their risk can be reduced through better control of modifiable risk factors, especially SBP. However, population studies show that management of stroke risk factors is inadequate and probably worse for minority populations. CCM is a guide to design interventions for improving outpatient care of chronic diseases, particularly diabetes. While CCM-based interventions are supported by theory and data, an RCT needs to be conducted to determine whether it can be successfully implemented in a new population – persons with a recent stroke or TIA– in a setting only infrequently studied, a county safety net health system. An intervention shown to be efficacious and cost-efficient can potentially improve the health of all persons with a recent stroke or TIA and provide a blueprint for CCM-based interventions implemented in underserved populations.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources: This work was supported by an award from the American Heart Association Pharmaceutical Roundtable and David and Stevie Spina. There are no sponsor-imposed restrictions on publication of this manuscript and any subsequent manuscripts about this study. Dr. Eric Cheng is supported by a Career Development Award from NIH/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS, K23NS058571). Dr. Cheng and Dr. Cunningham also received partial support from the UCLA/DREW Project EXPORT (NCMHD grants #P20MD000148/ P20MD000182). Dr. Cunningham also receives partial support from the UCLA Center for Health Improvement of Minority Elderly/Resource Centers for Minority Aging Research (NIA grant #P30AG021684).

Abbreviations

- AHA

American Heart Association

- CCM

chronic care model

- ICP

Inpatient Clinical Pathways

- LAC

Los Angeles County public healthcare system

- LAC-DHS

Los Angeles County Department of Health Services

- NP

nurse practitioner

- PA

physician assistant

- PI

principal investigator

- PROTECT

Preventing Occurrence of Thrombotic Events through Co-ordinated Treatment

- RA

research assistant

- RCT

randomized-controlled trial

- SBP

systolic blood pressure

- SUSTAIN

Systemic Use of Stroke Averting Interventions

- TIA

transient ischemic attack

Footnotes

Disclosures: None

References

- 1.Lloyd-Jones D, Adams RJ, Brown TM, Carnethon M, Dai S, De Simone G, Ferguson TB, Ford E, Furie K, Gillespie C, Go A, Greenlund K, Haase N, Hailpern S, Ho PM, Howard V, Kissela B, Kittner S, Lackland D, Lisabeth L, Marelli A, McDermott MM, Meigs J, Mozaffarian D, Mussolino M, Nichol G, Roger VL, Rosamond W, Sacco R, Sorlie P, Stafford R, Thom T, Wasserthiel-Smoller S, Wong ND, Wylie-Rosett J. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2010 update: a report from the american heart association. Circulation. 2010;121:e46–e215. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sacco RL, Adams R, Albers G, Alberts MJ, Benavente O, Furie K, Goldstein LB, Gorelick P, Halperin J, Harbaugh R, Johnston SC, Katzan I, Kelly-Hayes M, Kenton EJ, Marks M, Schwamm LH, Tomsick T. Guidelines for prevention of stroke in patients with ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Council on Stroke: co-sponsored by the Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention: the American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this guideline. Circulation. 2006;113:e409–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ovbiagele B, Saver JL, Fredieu A, Suzuki S, McNair N, Dandekar A, Razinia T, Kidwell CS. PROTECT: A coordinated stroke treatment program to prevent recurrent thromboembolic events. Neurology. 2004;63:1217–1222. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000140493.83607.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwamm LH, Fonarow GC, Reeves MJ, Pan W, Frankel MR, Smith EE, Ellrodt G, Cannon CP, Liang L, Peterson E, Labresh KA. Get With the Guidelines-Stroke is associated with sustained improvement in care for patients hospitalized with acute stroke or transient ischemic attack. Circulation. 2009;119:107–115. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.783688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qureshi AI, Suri MFK, Guterman LR, Hopkins LN. Ineffective secondary prevention in survivors of cardiovascular events in the US population: Report From the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1621–1628. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.13.1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng EM, Asch SM, Brook RH, Vassar SD, Jacob EL, Lee ML, Chang DS, Sacco RL, Hsiao AF, Vickrey BG. Suboptimal Control of Atherosclerotic Disease Risk Factors After Cardiac and Cerebrovascular Procedures. Stroke. 2007;38:929. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000257310.08310.0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng E, Chen A, Vassar S, Lee M, Cohen S, Vickrey B. Comparison of secondary prevention care after myocardial infarction and stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2006;21:235–241. doi: 10.1159/000091220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oliveria SA, Lapuerta P, McCarthy BD, L'Italien GJ, Berlowitz DR, Asch SM. Physician-related barriers to the effective management of uncontrolled hypertension. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:413–420. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.4.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stansbury JP, Jia H, Williams LS, Vogel WB, Duncan PW. Ethnic Disparities in Stroke: Epidemiology, Acute Care, and Postacute Outcomes. Stroke. 2005;36:374–386. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000153065.39325.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanossian N, Wu J, Azen SP, Varma R. Prevalence and risk factors for cerebrovascular disease in community-dwelling Latinos. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2008;110:985–987. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruland S, Raman R, Chaturvedi S, Leurgans S, Gorelick PB. Awareness, treatment, and control of vascular risk factors in African Americans with stroke. Neurology. 2003;60:64–68. doi: 10.1212/wnl.60.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rimmer JH, Braunschweig C, Silverman K, Riley B, Creviston T, Nicola T. Effects of a short-term health promotion intervention for a predominantly African-American group of stroke survivors. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18:332–338. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00129-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, Keesey J, Hicks J, DeCristofaro A, Kerr EA. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2635–2645. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa022615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. JAMA. 2002;288:1775–1779. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness: the chronic care model, Part 2. JAMA. 2002;288:1909–1914. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.15.1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trento M, Passera P, Tomalino M, Bajardi M, Pomero F, Allione A, Vaccari P, Molinatti GM, Porta M. Group visits improve metabolic control in type 2 diabetes: a 2-year follow-up. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:995–1000. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.6.995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coleman EA, Eilertsen TB, Kramer AM, Magid DJ, Beck A, Conner D. Reducing emergency visits in older adults with chronic illness. A randomized, controlled trial of group visits. Eff Clin Pract. 2001;4:49–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scott JC, Conner DA, Venohr I, Gade G, McKenzie M, Kramer AM, Bryant L, Beck A. Effectiveness of a group outpatient visit model for chronically ill older health maintenance organization members: a 2-year randomized trial of the cooperative health care clinic. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1463–1470. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clancy DE, Cope DW, Magruder KM, Huang P, Salter KH, Fields AW. Evaluating group visits in an uninsured or inadequately insured patient population with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2003;29:292–302. doi: 10.1177/014572170302900220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Culhane-Pera K, Peterson KA, Crain AL, Center BA, Lee M, Her B, Xiong T. Group visits for hmong adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a pre-post analysis. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2005;16:315–327. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2005.0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schillinger D, Bibbins-Domingo K, Vranizan K, Bacchetti P, Luce JM, Bindman AB. Effects of primary care coordination on public hospital patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:329–336. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.07010.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bodenheimer T, Lorig K, Holman H, Grumbach K. Patient self-management of chronic disease in primary care. JAMA. 2002;288:2469–2475. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.19.2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Warsi A, Wang PS, LaValley MP, Avorn J, Solomon DH. Self-management education programs in chronic disease: a systematic review and methodological critique of the literature. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1641–1649. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.15.1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grim CE, Grim CM. Omron HEM-711 DLX home Blood pressure monitor passes the European Society of Hypertension International Validation Protocol. Blood Press Monit. 2008;13:225–226. doi: 10.1097/MBP.0b013e3282feebd5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Los Angeles Country Health Services Clinical Resource Management Executive Summary. [July 27, 2010]; http://www.cahpf.org/GoDocUserFiles/248.CRM%20Executive%20Briefing%202007-01-22%201330.pdf.

- 26.Elliott WJ, Young PE, DeVivo L, Feldstein J, Black HR. A comparison of two sphygmomanometers that may replace the traditional mercury column in the healthcare workplace. Blood Press Monit. 2007;12:23–28. doi: 10.1097/MBP.0b013e3280858dcf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Omron FAQ: Blood pressure monitors. [July 7, 2010]; http://www.omronhealthcare.com/service-and-support/faq/blood-pressure-monitors/

- 28.Brott T, Adams HP, Jr, Olinger CP, Marler JR, Barsan WG, Biller J, Spilker J, Holleran R, Eberle R, Hertzberg V, et al. Measurements of acute cerebral infarction: a clinical examination scale. Stroke. 1989;20:864–870. doi: 10.1161/01.str.20.7.864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sulter G, Steen C, De Keyser Jacques. Use of the Barthel Index and Modified Rankin Scale in Acute Stroke Trials. Stroke. 1999;30:1538–1541. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.8.1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pancioli AM, Broderick J, Kothari R, Brott T, Tuchfarber A, Miller R, Khoury J, Jauch E. Public Perception of Stroke Warning Signs and Knowledge of Potential Risk Factors. JAMA. 1998;279:1288–1292. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.16.1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schneider AT, Pancioli AM, Khoury JC, Rademacher E, Tuchfarber A, Miller R, Woo D, Kissela B, Broderick JP. Trends in community knowledge of the warning signs and risk factors for stroke. JAMA. 2003;289:343–346. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.3.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hargraves JL, Hays RD, Cleary PD. Psychometric properties of the Consumer Assessment of Health Plans Study (CAHPS) 2.0 adult core survey. Health Serv Res. 2003;38:1509–1527. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2003.00190.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simoni JM, Kurth AE, Pearson CR, Pantalone DW, Merrill JO, Frick PA. Self-report measures of antiretroviral therapy adherence: A review with recommendations for HIV research and clinical management. AIDS Behav. 2006;10:227–245. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9078-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morisky DE, Green LW, Levine DM. Concurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence. Med Care. 1986;24:67–74. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198601000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Caetano PA, Lam JM, Morgan SG. Toward a standard definition and measurement of persistence with drug therapy: Examples from research on statin and antihypertensive utilization. Clin Ther. 2006;28:1411–1424. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41:1284–1292. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wong MD, Sarkisian CA, Davis C, Kinsler J, Cunningham WE. The association between life chaos, health care use, and health status among HIV-infected persons. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1286–1291. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0265-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cunningham WE, Andersen RM, Katz MH, Stein MD, Turner BJ, Crystal S, Zierler S, Kuromiya K, Morton SC, St Clair P, Bozzette SA, Shapiro MF. The impact of competing subsistence needs and barriers on access to medical care for persons with human immunodeficiency virus receiving care in the United States. Med Care. 1999;37:1270–1281. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199912000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32:705–714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marin G, Gamba RJ. A new measurement of acculturation for Hispanics: The bidimensional acculturation scale for Hispanics (BAS) Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1996;18:297–316. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vickrey BG, Mittman BS, Connor KI, Pearson ML, Della Penna RD, Ganiats TG, DeMonte RW, Jr, Chodosh J, Cui X, Vassar S, Duan N, Lee M. The Effect of a Disease Management Intervention on Quality and Outcomes of Dementia Care: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:713–726. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-10-200611210-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brazier J, Usherwood T, Harper R, Thomas K. Deriving a preference-based single index from the UK SF-36 Health Survey. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:1115–1128. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00103-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jr, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT, Jr, Roccella EJ. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 Report. JAMA. 2003;289:2560–2571. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lawes CM, Bennett DA, Feigin VL, Rodgers A. Blood pressure and stroke: an overview of published reviews. Stroke. 2004;35:1024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360:1903–1913. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11911-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Randomised trial of a perindopril-based blood-pressure-lowering regimen among 6105 individuals with previous stroke or transient ischaemic attack. The Lancet. 2001;358:1033–1041. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06178-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baskerville NB, Hogg W, Lemelin J. The effect of cluster randomization on sample size in prevention research. J Fam Pract. 2001;50:W241–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Donner A, Klar N. Pitfalls of and controversies in cluster randomization trials. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:416–422. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.3.416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wolfe CD, Redfern J, Rudd AG, Grieve AP, Heuschmann PU, McKevitt C. Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial of a Patient and General Practitioner Intervention to Improve the Management of Multiple Risk Factors After Stroke. Stop Stroke. Stroke. 2010 doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.588046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rothwell PM, Giles MF, Chandratheva A, Marquardt L, Geraghty O, Redgrave JN, Lovelock CE, Binney LE, Bull LM, Cuthbertson FC, Welch SJ, Bosch S, Alexander FC, Silver LE, Gutnikov SA, Mehta Z. Effect of urgent treatment of transient ischaemic attack and minor stroke on early recurrent stroke (EXPRESS study): a prospective population-based sequential comparison. Lancet. 2007;370:1432–1442. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61448-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]