Abstract

Objective:

Sleep problems occur in 20% to 30% of young children. Although behaviorally based interventions are highly efficacious, most existing interventions require personal contact with a trained professional, and unfortunately many children remain untreated. However, the use of an internet-based intervention could provide widespread access. Thus, the purpose of this study was to examine the efficacy of an internet-based intervention for infant and toddler sleep disturbances, as well as to assess any indirect benefits to maternal sleep, mood, and confidence.

Methods:

264 mothers and their infant or toddler (ages 6-36 months) participated in a 3-week study. Families were randomly assigned to one of 2 intervention groups (algorithmic internet-based intervention alone or in combination with a prescribed bedtime routine) or a control group. After a one-week baseline (usual routine), the intervention groups followed personalized recommendations during weeks 2 and 3. All mothers completed the Brief Infant Sleep Questionnaire, the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, and the Profile of Mood States weekly.

Results:

Both internet-based interventions resulted in significant reductions in problematic sleep behaviors. Significant improvements were seen in latency to sleep onset and in number/duration of night wakings, P < 0.001. Sleep continuity increased as well as mothers' confidence in managing their child's sleep. Improvements were seen by one week, with additional benefits by week two. Maternal sleep and mood were also significantly improved.

Conclusions:

This internet-based intervention (with and without routine) is beneficial in improving multiple aspects of infant and toddler sleep, especially wakefulness after sleep onset and sleep continuity, as well as improving maternal sleep and mood.

Citation:

Mindell JA; Du Mond CE; Sadeh A; Telofski LS; Kulkarni N; Gunn E. Efficacy of an internet-based intervention for infant and toddler sleep disturbances. SLEEP 2011;34(4):451-458.

Keywords: Sleep, infant, toddler, sleep problems, bedtime disturbances, night wakings, behavioral intervention

INTRODUCTION

Sleep problems are highly prevalent in young children, occurring in approximately 20% to 30% of infants and toddlers,1,2 and occur across cultures.3 They are one of the most common behavioral issues brought to the attention of primary care providers, although few pediatricians are confident in their ability to manage these problems and the majority lack the time to provide effective treatment.4,5 Fortunately, though, these behaviorally based sleep disturbances are highly treatable, with the American Academy of Sleep Medicine recently releasing a Standards of Practice documenting the high efficacy of behavioral interventions for bedtime problems and night wakings in young children.1,6 Furthermore, studies indicate that these sleep issues not only affect the child, but also have a significant negative impact on parents. In particular, behavioral interventions for children's sleep often lead to improvements in parental well-being.1,7,8

Behavioral interventions aimed at parents of young children have traditionally been conducted in face-to-face sessions, with limited availability, or through written educational materials, which lack the ability to be individualized. In contrast, the internet has become a widely used resource for parents, and internet-based interventions have the benefits of being available to a wide audience and the ability to be individualized through algorithms. Internet-based interventions or “information prescriptions” have been shown to be efficacious for multiple child health concerns, as well as adult insomnia.9–11 Thus, internet-based interventions appear to be an ideal method for providing treatment recommendations for sleep problems in early childhood. No online algorithmically based pediatric sleep interventions have been developed in the US to date, that we know of, and no studies have evaluated the efficacy of such an internet-based intervention.

The overall objective of the current study was to examine the efficacy of a newly developed internet-based intervention for mild to moderate infant and toddler sleep disturbances. We hypothesized that individualized recommendations provided in an internet-based format would result in (1) improvement in infant and toddler sleep, including decreased sleep onset latency, decreased night wakings, and increased sleep continuity; (2) positive impact on maternal sleep, mood, and confidence; and (3) that there may be an additive effect of the internet intervention alone in comparison to the internet intervention in combination with a prescribed bedtime routine that has been previously shown to be efficacious.12

METHODS

Participants

Overall, 264 mothers and their young children (6-36 months; 49.6% boys) participated in this study. Participants were recruited over a 3-week period prior to the start of the study through an independent market research firm utilizing contact lists of parents of young children and were screened by telephone. There were originally 272 families in the study; however, only 264 (97.1%) had complete data (attrition: 1 family in control group; 5 in internet, and 2 in internet + routine). See Table 1 for demographic information for all families with complete data.

Table 1.

Demographic variables

| Entire sample (n = 264) | |

|---|---|

| Variable | Percent (n)/Mean (SD) |

| Child's Gender | |

| Boy | 49.6 (131) |

| Girl | 50.4 (133) |

| Child's age (months) | 19.35 (8.88) |

| Age of Mother | |

| 18-29 | 32.6 (86) |

| 30-39 | 59.1 (156) |

| 40-49 | 8.3 (22) |

| Married | 89.0 (235) |

| School | |

| Graduated high school | 6.8 (18) |

| Some college | 28.8 (76) |

| College degree or more | 64.4 (170) |

| Employed | |

| Full-Time | 26.5 (70) |

| Part-Time | 23.5 (62) |

| Not Employed | 50.0 (132) |

| Income | |

| < $30,000 | 4.2 (11) |

| $30,000 - $39,999 | 15.5 (41) |

| $40,000 - $49,999 | 10.2 (27) |

| $50,000 - $74,999 | 34.1 (90) |

| $75,000 – 99,000 | 21.2 (56) |

| $100,000 or more | 14.4 (38) |

Inclusion criteria for the study required that all children must have a parent-identified sleep problem, with all mothers endorsing that their child had a sleep problem that ranged from “small” to “serious” (48% small problem, 49% moderate problem, 3% serious problem), as well as experienced bedtime difficulties, as indicated by bedtime being “somewhat difficult (56%), “moderately difficult” (37%), or “very difficult” (7%). However, families were excluded if the child had an apparent significant sleep disorder that may be related to developmental or medical issues, as defined as (1) > 3 night wakings per night, (2) awake > 60 min per night, or (3) total daily sleep duration < 9 hours. Additional exclusion criteria included: (1) non-English speaking, as all information and questionnaires were presented in English, (2) lack of internet access, as entire study was conducted online, (3) maternal age < 18 or > 49 years, (4) current acute or chronic illness, and (5) child routinely bathed before bed (after 16:00) ≥ 4 times per week, as a nightly bath was part of the prescribed bedtime routine for one of the intervention groups. Exclusion criteria were applied prior to random assignment to groups.

Measures

All measures were completed online on days 8, 15, and 22 regarding the past week. Families accessed the measures, and online intervention, from their home computer via a free-standing study website and mothers were provided with individual usernames and passwords to access the site.

Brief Infant Sleep Questionnaire

All mothers completed an expanded version of the Brief Infant Sleep Questionnaire (BISQ).13 The BISQ has been validated against actigraphy and daily logs, and its sensitivity in documenting expected developmental trends in young children's sleep and the effects of environmental factors has been established. Test-retest reliability for individual sleep measures on the BISQ was high (r = 0.81 to 0.95), as were comparisons between the BISQ and actigraphy (r = 0.23 to 0.54).13 The expanded version of the BISQ, as described previously,2 included questions about the child's daytime and nighttime sleep patterns, sleep-related behaviors, and maternal perceptions.

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)

The PSQI is a widely-used and well-validated 19-item self-report instrument that measures sleep disturbances in adults.14 The PSQI includes 7 subscale scores (sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, sleep medications, and daytime dysfunction), as well as provides a global score ranging from no sleep difficulty to severe difficulties. A global score > 5 indicates a “poor sleeper” and has been shown to have a diagnostic sensitivity of 89.6% and specificity of 86.5%. The expanded version of the PSQI used in this study included additional questions about night wakings, but these additional questions were not included in the global score. Mothers completed this measure regarding their own sleep.

Profile of Mood States (POMS)

The POMS is a well-validated measure of mood states.15 The 65-item scale measures 6 identified sub-scales: tension-anxiety, depression-dejection, anger-hostility, vigor-activity, fatigue-inertia, and confusion-bewilderment. Each item is responded to on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 0 = “not at all” to 5 = “extremely.” Higher scores indicate more negative mood state, except for vigor-activity for which lower scores denote negative mood state. The POMS has high internal consistency, as well as predictive and constructive validity.16 The POMS demonstrated sensitivity in detecting mood changes in similar contexts.12

Procedure

This study was approved by an institutional review board, and informed consent was obtained in-person from all participants on an individual basis. Families were not informed of the sponsor of the study and were paid $90 to $175 for their participation (payment based on the number of visits required to the study site). Families were randomly assigned (ensuring equal gender and age) to one of 3 groups. Mothers in each group were scheduled for in-person informed consent at different times so that no families were aware of the other groups. Thus, there were slightly uneven group sizes as a result of families' availability on certain days and times. The entire study (baseline and intervention weeks) was conducted during the same 3-week period for all participants.

All 264 families completed a one-week baseline period in which mothers followed their child's usual bedtime practices. Ninety-six (36%) families were randomly assigned to the internet-based intervention group (internet). Following the baseline period, the mothers were instructed to complete the internet-based intervention from their home computer (see description below), and mothers were instructed to follow the individualized recommendations that were provided. Eighty-four (32%) families were randomly assigned to the internet-based intervention plus routine group (internet + routine). In addition to completion of the internet-based intervention, these mothers were instructed to institute a nightly 3-step bedtime routine that included a bath (using a provided wash product), a lotion/ massage (using a provided moisturizing product), and quiet activities (e.g., cuddling, singing lullaby) with lights out within 30 minutes of the end of the bath. All mothers were provided with the same products. The participants were not intentionally blinded to the product, but the product was unrecognizable by maternal report (study labels covered identifying information). This specific bedtime routine has been found to result in significant improvements in sleep.12 Eight-four (32%) families participated as controls, and were randomly assigned to this group. These mothers were instructed to follow their child's usual bedtime practices throughout the entire 3-week period. They were informed that the study was about children's bedtime activities and sleep behaviors.

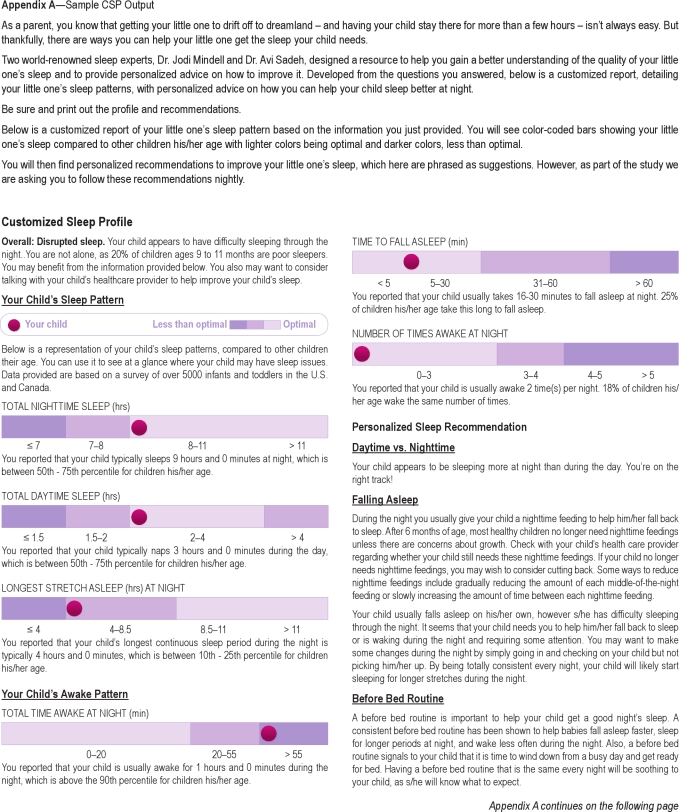

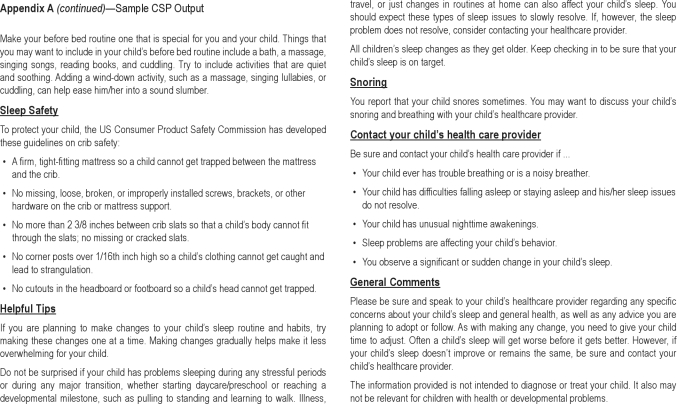

Customized sleep profile (CSP)

The CSP is an algorithm-based internet intervention developed by 2 of the authors (Mindell and Sadeh). The CSP collects caregivers' responses on an expanded version of the BISQ and provides parents with individualized information across three general domains: (1) a normative comparison of their child's sleep to other children of the same age (based on a normative database of over 5000 children ages 0-32); (2) a rating of whether their child is an “excellent, good, or disrupted sleeper” (based on an age-based algorithm that takes into account total sleep time, sleep onset latency, and number/duration of night wakings); (3) customized advice on how caregivers can help their child sleep better at night. For example, if a parent indicates that they feed their child to sleep at bedtime on the BISQ, recommendations regarding discontinuing feeding to sleep are provided. All advice is based on empirically supported recommendations,1,6 and includes such aspects as the importance of an early bedtime, the establishment of a consistent bedtime routine, decreasing negative sleep associations, and overall development of positive sleep habits. Additional information is provided on crib and sleep safety, which are based on American Academy of Pediatrics and Consumer Product Safety Commission guidelines. Recommendations provided are tailored to each child based on responses to the BISQ and are provided online in text and as graphs (normative information), as well as being automatically emailed to each family so that they can continue to refer to the advice at any time. An example of the information provided to a family is available in Appendix A.

On day 8, mothers in the internet intervention groups accessed the CSP via a free-standing internet site designed for this study, following completion of all baseline measures from their home computer. Mothers were instructed to follow the individually tailored sleep recommendations throughout weeks 2 and 3.

Data Analyses

Descriptive analyses (means, frequencies) were used to describe demographic and sleep variables. Preliminary analyses, including analysis of variance and χ2 tests, were conducted to evaluate whether there were any demographic differences between the 3 groups that would need to be controlled for when conducting between-group analyses, however none were noted. Similar analyses were conducted to determine whether sleep patterns differed between the groups. Although randomly assigned, there were significant differences in sleep patterns at baseline. Specifically, there were significant differences between the controls and intervention children at baseline for bedtime difficulty, maternal confidence, and parent perception of sleep problems (P < 0.05), and significant trends for sleep onset latency, morning mood, and perception of night time sleep (P < 0.10), with no significant differences between the 2 intervention groups (P < 0.05). Overall, children in the control group were reported to be better sleepers by the mothers compared with children in both intervention groups. Two-way analyses of variance were conducted across group (control, internet, internet + routine) × time (baseline, week 2, week 3), with significant findings noted in the tables. However, given the differences at baseline, individual repeated measures oneway ANOVAs were considered more appropriate and conducted separately for each variable within the control group and the intervention groups. All significant findings were followed by Tukey HSD post hoc testing. Because of the multiple analyses conducted, findings were only considered significant if P < 0.001. All outcomes were similar for infants (ages 0-11 months) and toddlers (ages 12-36 months), and thus results are presented for the entire group. Furthermore, there were no significant associations between any demographic variable and any sleep outcomes (P > 0.01).

RESULTS

Sleep Recommendations

Table 2 presents the recommendations that were provided to the individual families. As can be seen, all families were recommended to institute a bedtime routine. One-third to two-thirds of families were provided recommendations on making changes to their child's sleep schedule, decreasing sleep-related negative associations, and changing how they respond to their child during the night.

Table 2.

Individualized internet intervention recommendations

| Recommendation | Internet Percent (n) | Internet & Routine Percent (n) | Total Percent (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Implement bedtime routine | 100% (96) | 100% (84) | 100% (180) |

| Increase sleep time | 25.0% (24) | 26.2% (22) | 25.6% (46) |

| Discontinue negative sleep associations | 38.5% (37) | 40.5% (34) | 39.4% (71) |

| Decrease or stop nighttime feedings | 34.4% (33) | 36.9% (31) | 35.6% (64) |

| Decrease attention to night wakings | 55.2% (53) | 66.7% (56) | 60.6% (109) |

| Encourage child to get own pacifier at night | 25.0% (24) | 23.8% (20) | 24.4% (44) |

| Use more absorbent diapers | 34.4% (33) | 26.2% (22) | 30.6% (55) |

| Switch back to crib from bed | 17.7% (17) | 13.1% (11) | 15.6% (28) |

| Have child sleep in own bed rather than parents’ bed | 2.1% (2) | 3.6% (3) | 2.8% (5) |

| Consult primary care practitioner about snoring | 16.7% (16) | 21.4% (18) | 18.9% (34) |

Overall, parents were very positive about the internet-based intervention. On a 5-point Likert scale, 90% of the mothers in both intervention groups reported that they found the individualized recommendations “helpful,” with 45.6% finding them “very helpful.” In addition, 93.3% said that they were likely (74.4% “very likely”) to continue using the recommendations after the study, with 94% of the mothers in the internet + routine group stating they were likely to continue using the prescribed routine and products (75% very likely).

Child Sleep

Significant differences were found for almost all sleep variables following institution of the intervention compared to baseline for both intervention groups (Table 3). Overall, children had decreased sleep onset latency, decreased number/duration of night wakings, increased sleep continuity, and increased nighttime sleep (P < 0.001). There was a nonsignificant effect for total nighttime sleep, P = 0.006. There were also improvements in parents' perception of their child's mood in the morning, sleep as a problem, bedtime difficulty, how well their child slept, and mothers' confidence in managing their child's sleep (P < 0.001). No significant changes were found for naps or how often their child woke on his/her own in the morning, P > 0.05. Post-hoc analyses (Tukey HSD) indicate that for many sleep variables (e.g., night wakings, sleep continuity), significant differences occurred between baseline and week 2, with additional improvements at week 3. No significant differences were found at the end of intervention between the 2 intervention groups for any sleep outcome, P > 0.05. However, visual inspection indicated that the effect sizes were slightly larger for many sleep outcome variables in the internet + routine group.

Table 3.

Sleep-wake patterns for infants and toddlers (BISQ)

| Baseline | Week 2 | Week 3 | ANOVA |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | WL | F | P | ES |

| Sleep latency (min)‡ | |||||||

| Control | 20.39 (16.32) | 17.98 (14.21) | 18.48 (14.06) | 0.951 | 01.12 | 0.127 | 0.049 |

| Interneta | 25.49 (16.33) | 19.79 (14.38) | 14.22 (11.83) | 0.600 | 31.31 | < 0.001 | 0.400 |

| Internet & Routinea | 25.00 (16.30) | 15.89 (15.05) | 14.58 (14.30) | 0.652 | 21.86 | < 0.001 | 0.348 |

| Number of night wakings‡ | |||||||

| Control | 1.64 (1.06) | 1.60 (1.03) | 1.42 (1.02) | 0.938 | 2.69 | 0.074 | 0.062 |

| Interneta,c | 1.81 (1.13) | 1.44 (1.03) | 0.99 (0.85) | 0.558 | 37.18 | < 0.001 | 0.442 |

| Internet & Routinea,c | 1.85 (0.93) | 1.27 (0.87) | 0.94 (0.84) | 0.559 | 32.34 | < 0.001 | 0.441 |

| Duration of night wakings (min)‡ | |||||||

| Control | 36.61 (38.21) | 33.21 (31.07) | 33.21 (37.69) | 0.989 | 0.45 | 0.638 | 0.011 |

| Interneta,c | 46.41 (42.87) | 35.94 (36.90) | 22.81 (32.35) | 0.753 | 15.40 | < 0.001 | 0.247 |

| Internet & Routinea,c | 41.43 (29.97) | 23.75 (21.87) | 15.89 (19.94) | 0.584 | 29.20 | < 0.001 | 0.416 |

| Longest continuous sleep period (hours)‡ | |||||||

| Controla,c | 6.38 (2.48) | 6.90 (2.47) | 7.21 (2.06) | 0.830 | 7.81 | 0.001 | 0.170 |

| Interneta,c | 5.74 (2.41) | 6.61 (2.40) | 7.78 (2.40) | 0.582 | 31.16 | < 0.001 | 0.418 |

| Internet & Routinea,c | 5.80 (2.17) | 7.19 (2.46) | 8.07 (2.58) | 0.518 | 34.89 | < 0.001 | 0.482 |

| Total nighttime sleep (hours) | |||||||

| Control | 9.72 (1.33) | 9.78 (1.59) | 9.86 (1.62) | 0.983 | 0.70 | 0.499 | 0.017 |

| Interneta,c | 9.49 (1.53) | 9.82 (1.39) | 10.16 (1.22) | 0.776 | 12.99 | < 0.001 | 0.224 |

| Internet & Routinea,c | 9.43 (1.44) | 9.83 (1.22) | 10.17 (1.21) | 0.719 | 15.60 | < 0.001 | 0.281 |

| Total naps (hours) | |||||||

| Control | 1.43 (0.66) | 1.40 (0.64) | 1.36 (0.65) | 0.985 | 0.61 | 0.547 | 0.015 |

| Internet | 1.39 (0.73) | 1.36 (0.65) | 1.32 (0.61) | 0.966 | 1.67 | 0.194 | 0.034 |

| Internet & Routine | 1.46 (0.69) | 1.44 (0.71) | 1.47 (0.73) | 0.992 | 0.35 | 0.709 | 0.008 |

| Consider sleep a problem^‡ | |||||||

| Controlb,c | 2.73 (1.03) | 2.68 (1.10) | 2.32 (1.14) | 0.756 | 13.25 | < 0.001 | 0.244 |

| Interneta,c | 2.89 (0.95) | 2.54 (1.02) | 1.92 (0.98) | 0.499 | 47.13 | < 0.001 | 0.501 |

| Internet & Routinea,c | 3.21 (0.95) | 2.52 (1.05) | 1.95 (1.05) | 0.407 | 59.76 | < 0.001 | 0.593 |

| Child's mood in morning^ | |||||||

| Control | 2.02 (1.10) | 2.02 (1.08) | 1.96 (1.02) | 0.995 | 0.22 | 0.806 | 0.005 |

| Interneta | 2.04 (1.04) | 1.17 (0.81) | 1.54 (0.77) | 0.821 | 10.27 | < 0.001 | 0.179 |

| Internet & Routinea | 2.36 (1.17) | 1.76 (0.94) | 1.73 (0.96) | 0.764 | 12.68 | < 0.001 | 0.236 |

| Number of times called | |||||||

| Control | 2.48 (2.13) | 2.18 (1.79) | 1.84 (1.86) | 0.897 | 2.76 | 0.074 | 0.103 |

| Interneta | 3.03 (2.43) | 2.70 (2.79) | 1.47 (1.73) | 0.625 | 17.39 | < 0.001 | 0.375 |

| Internet & Routinea,c | 2.93 (2.43) | 1.79 (2.04) | 1.18 (1.39) | 0.571 | 20.29 | < 0.001 | 0.429 |

| Number of times out of crib/bed | |||||||

| Control | 1.97 (2.25) | 1.70 (2.35) | 1.50 (1.92) | 0.917 | 1.72 | 0.192 | 0.083 |

| Internet | 1.84 (2.07) | 1.65 (2.03) | 1.02 (1.60) | 0.743 | 7.09 | 0.002 | 0.257 |

| Internet & Routine | 2.18 (2.75) | 1.26 (1.99) | 0.59 (0.93) | 0.690 | 7.20 | 0.003 | 0.310 |

| How difficult was bedtime?^ | |||||||

| Control | 2.48 (2.13) | 2.18 (1.79) | 1.84 (1.86) | 0.865 | 6.42 | 0.003 | 0.135 |

| Interneta,c | 3.03 (2.43) | 2.70 (2.79) | 1.47 (1.73) | 0.410 | 67.54 | < 0.001 | 0.590 |

| Internet & Routinea | 2.93 (2.43) | 1.79 (2.04) | 1.18 (1.39) | 0.345 | 77.90 | < 0.001 | 0.655 |

| How well did child sleep?^‡ | |||||||

| Control | 2.96 (1.07) | 2.70 (1.06) | 2.69 (1.10) | 0.860 | 6.65 | 0.002 | 0.140 |

| Interneta,c | 3.16 (1.02) | 2.67 (1.01) | 2.11 (0.96) | 0.481 | 50.76 | < 0.001 | 0.519 |

| Internet & Routinea,c | 3.33 (1.01) | 2.31 (0.96) | 2.04 (0.96) | 0.430 | 54.24 | < 0.001 | 0.570 |

| Bedtime | |||||||

| Control | 8.35 (0.95) | 8.34 (0.97) | 8.29 (0.96) | 0.944 | 2.46 | 0.092 | 0.056 |

| Interneta,c | 8.46 (0.93) | 8.28 (0.78) | 8.17 (0.72) | 0.797 | 11.97 | < 0.001 | 0.203 |

| Internet & Routine | 8.56 (0.94) | 8.43 (0.81) | 8.38 (0.76) | 0.918 | 3.67 | 0.030 | 0.082 |

| Wake time | |||||||

| Control | 6.65 (0.95) | 6.78 (0.90) | 6.86 (0.99) | 0.937 | 2.76 | 0.069 | 0.063 |

| Internet | 6.68 (1.21) | 6.88 (1.09) | 7.83 (1.07) | 0.941 | 2.96 | 0.057 | 0.059 |

| Internet & Routineb,c | 6.57 (0.99) | 6.68 (0.85) | 6.97 (1.02) | 0.813 | 9.43 | < 0.001 | 0.187 |

| Maternal confidence‡ | |||||||

| Control | 2.40 (1.13) | 2.36 (1.11) | 2.12 (1.19) | 0.889 | 5.12 | 0.008 | 0.111 |

| Interneta,c | 2.98 (1.07) | 2.23 (0.96) | 1.69 (0.86) | 0.372 | 79.33 | < 0.001 | 0.628 |

| Internet & Routinea,c | 2.73 (1.09) | 1.96 (1.07) | 1.65 (0.95) | 0.542 | 34.68 | < 0.001 | 0.458 |

| How often same routine | |||||||

| Control | 3.94 (0.90) | 3.95 (0.93) | 4.12 (0.84) | 0.922 | 3.47 | 0.036 | 0.078 |

| Interneta | 3.83 (1.00) | 4.15 (0.86) | 4.31 (0.77) | 0.796 | 12.07 | < 0.001 | 0.204 |

| Internet & Routinea | 3.89 (0.93) | 4.40 (0.71) | 4.42 (0.63) | 0.746 | 13.97 | < 0.001 | 0.254 |

| How often wakes on own | |||||||

| Control | 4.52 (0.83) | 4.60 (0.82) | 4.67 (0.67) | 0.966 | 1.44 | 0.242 | 0.034 |

| Internet | 4.47 (0.91) | 4.53 (0.85) | 4.56 (0.89) | 0.991 | 0.43 | 0.651 | 0.009 |

| Internet & Routine | 4.35 (1.04) | 4.68 (0.81) | 4.64 (0.90) | 0.873 | 5.96 | 0.004 | 0.127 |

A one way repeated measures ANOVA was utilized to analyze group differences over time.

Significant difference between baseline/week 2 and baseline/week 3.

Significant difference between baseline and week 3.

Significant difference between week 2 and week 3.

Lower scores are better.

Significant interaction. WL, Wilks lambda; ES, Effect size as partial Eta2 where 0.10 = small effect, 0.25 = moderate effect, and 0.40 = large.

There were few significant differences found across the 3 weeks for the control group. There was some improvement in sleep continuity and parental perception of sleep problems (P < 0.001), with smaller effect sizes for the control group compared to both intervention groups for both variables.

Maternal Sleep

For both intervention groups, following implementation of the intervention, maternal sleep was improved including sleep onset latency, total sleep time, number and duration of night wakings, sleep efficiency, and total sleep quality (P < 0.001; see Table 4). No changes in either bedtime or wake time were reported by mothers in any of the 3 groups. P > 0.05. Mothers in the control group were found to have fewer night wakings and improved global sleep quality at the end of the study compared to baseline, P < 0.001. Effect sizes for global sleep quality were lower for the control group (ES = 0.27) compared to the intervention groups (ES = 0.51 and 0.62).

Table 4.

Maternal sleep (PSQI)

| Baseline | Week 2 | Week 3 | ANOVA |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | WL | F | P | ES |

| Bedtime | |||||||

| Control | 10.85 (1.12) | 10.83 (0.99) | 10.94 (1.08) | 0.979 | 0.88 | 0.415 | 0.021 |

| Internet | 10.88 (1.14) | 10.67 (1.07) | 10.68 (1.17) | 0.919 | 4.12 | 0.019 | 0.081 |

| Internet & Routine | 10.84 (1.00) | 10.64 (1.03) | 10.76 (0.95) | 0.912 | 3.98 | 0.022 | 0.088 |

| Sleep Onset Latency | |||||||

| Control | 23.33 (21.33) | 23.18 (22.59) | 21.93 (34.67) | 0.997 | 0.12 | 0.892 | 0.003 |

| Interneta,c | 25.19 (19.16) | 20.21 (13.16) | 17.16 (12.24) | 0.723 | 18.03 | < 0.001 | 0.277 |

| Internet & Routinea,c | 26.99 (23.35) | 18.30 (13.62) | 16.43 (13.91) | 0.799 | 10.32 | < 0.001 | 0.201 |

| Waketime | |||||||

| Control | 6.57 (0.93) | 6.71 (0.95) | 6.79 (0.91) | 0.943 | 2.46 | 0.092 | 0.057 |

| Internet | 6.66 (1.10) | 6.70 (1.04) | 6.82 (1.04) | 0.887 | 5.98 | 0.004 | 0.113 |

| Internet & Routine | 6.53 (0.92) | 6.57 (0.96) | 6.78 (1.01) | 0.895 | 4.80 | 0.011 | 0.105 |

| Total Sleep Time | |||||||

| Control | 6.81 (1.15) | 7.02 (1.28) | 7.12 (1.19) | 0.913 | 3.82 | 0.026 | 0.087 |

| Interneta,c | 6.58 (1.16) | 6.99 (1.05) | 7.30 (1.01) | 0.657 | 24.58 | < 0.001 | 0.343 |

| Internet & Routinea,c | 6.71 (1.11) | 7.15 (1.13) | 7.49 (1.15) | 0.655 | 21.16 | < 0.001 | 0.345 |

| Night Wakings | |||||||

| Controla | 3.51 (2.82) | 2.43 (2.04) | 2.20 (1.94) | 0.792 | 10.77 | < 0.001 | 0.208 |

| Interneta,c | 3.72 (2.87) | 2.87 (2.33) | 2.29 (2.67) | 0.764 | 14.54 | < 0.001 | 0.236 |

| Internet & Routinea | 3.14 (2.19) | 2.10 (2.02) | 1.79 (1.71) | 0.781 | 11.52 | < 0.001 | 0.219 |

| Time Awake Night | |||||||

| Control | 18.59 (13.60) | 19.30 (13.63) | 20.39 (29.99) | 0.994 | 0.19 | 0.825 | 0.006 |

| Interneta | 24.75 (18.36) | 18.03 (13.08) | 17.65 (15.69) | 0.846 | 6.63 | 0.002 | 0.154 |

| Internet & Routinea | 23.93 (23.75) | 15.31 (10.65) | 17.61 (21.81) | 0.807 | 7.07 | 0.002 | 0.193 |

| Sleep Efficiency | |||||||

| Control | 88.98 (13.26) | 89.60 (12.52) | 90.36 (9.99) | 0.989 | 0.43 | 0.652 | 0.011 |

| Internetb,c | 84.98 (12.79) | 87.21 (9.70) | 90.51 (10.67) | 0.801 | 11.67 | < 0.001 | 0.199 |

| Internet & Routineb,c | 87.47 (10.75) | 90.23 (8.46) | 93.80 (10.82) | 0.722 | 15.77 | < 0.001 | 0.278 |

| Global Sleep Quality‡ | |||||||

| Controla,c | 8.62 (2.29) | 7.90 (1.38) | 7.23 (2.49) | 0.733 | 14.92 | < 0.001 | 0.267 |

| Interneta,c | 9.23 (2.46) | 7.55 (2.20) | 6.49 (2.06) | 0.489 | 49.15 | < 0.001 | 0.511 |

| Internet & Routinea,c | 9.10 (2.19) | 7.07 (2.10) | 6.05 (2.22) | 0.384 | 65.84 | < 0.001 | 0.616 |

A one way repeated measures ANOVA was utilized to analyze group differences over time. ^Lower scores are better.

Significant difference between baseline/week 2 and baseline/week 3.

Significant difference between baseline and week 3.

Significant difference between week 2 and week 3.

Significant interaction. WL, Wilks lambda; ES, Effect size as partial Eta2 where 0.10 = small effect, 0.25 = moderate effect, and 0.40 = large.

At baseline, 8.3% (control), 2.1% (internet), and 6.0% (internet + routine) of mothers were considered good sleepers (PSQI global score < 5), with no significant differences across groups, P > 0.05. At the end of treatment, 25.0% of mothers in the control group were good sleepers, in comparison to 33.3% (internet) and 47.6% (internet + routine) of mothers in each of the intervention groups, χ2 = 10.72, P = 0.005.

Maternal Mood State

Significant improvements for mothers in the internet + routine group were found for all subscales of the POMS (P < 0.001; see Table 5). For mothers in the internet only group, there were significant improvements in tension, depression, fatigue, and confusion (P < 0.001). As seen in Table 5, post hoc analyses (Tukey HSD) indicate that significant differences were found between baseline and both week 2 and week 3 for all significant subscales of the POMS, with additional differences between week 2 and week 3 for many of the subscales. The only significant difference found for maternal mood for the control group was for fatigue, P < 0.001, although there was significantly less of a decrease in this group compared to the intervention groups (ES = 0.19 vs 0.39 and 0.53).

Table 5.

Maternal mood (POMS)

| Baseline | Week 2 | Week 3 | ANOVA |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | WL | F | P | ES |

| Tension | |||||||

| Control | 8.17 (5.50) | 7.29 (4.84) | 6.58 (5.60) | 0.920 | 3.54 | 0.033 | 0.080 |

| Interneta,c | 9.65 (5.88) | 8.00 (6.10) | 6.83 (6.38) | 0.762 | 14.64 | < 0.001 | 0.238 |

| Internet & Routinea,c | 8.68 (4.44) | 5.86 (4.10) | 4.76 (3.76) | 0.613 | 15.88 | < 0.001 | 0.387 |

| Depression | |||||||

| Control | 5.55 (6.49) | 5.79 (7.44) | 5.08 (8.67) | 0.990 | 0.411 | 0.665 | 0.010 |

| Interneta,c | 6.57 (7.98) | 5.00 (7.91) | 3.77 (7.11) | 0.832 | 9.52 | < 0.001 | 0.168 |

| Internet & Routinea,c | 4.93 (5.59) | 2.92 (4.49) | 1.96 (2.91) | 0.722 | 15.76 | < 0.001 | 0.278 |

| Anger | |||||||

| Control | 5.76 (5.52) | 5.38 (5.98) | 4.48 (6.58) | 0.950 | 2.17 | 0.121 | 0.050 |

| Internet | 6.35 (6.22) | 4.83 (6.07) | 4.31 (6.73) | 0.911 | 4.57 | 0.013 | 0.089 |

| Internet & Routinea | 4.74 (4.84) | 3.10 (3.87) | 2.25 (3.02) | 0.751 | 13.58 | < 0.001 | 0.249 |

| Fatigue | |||||||

| Controlb,c | 8.30 (5.48) | 7.70 (5.91) | 6.24 (5.45) | 0.809 | 9.69 | < 0.001 | 0.191 |

| Interneta,c | 9.51 (5.65) | 7.25 (5.81) | 5.40 (5.60) | 0.613 | 29.70 | < 0.001 | 0.387 |

| Internet & Routinea,c | 8.23 (5.26) | 5.05 (3.79) | 3.36 (3.42) | 0.471 | 46.13 | < 0.001 | 0.529 |

| Vigor | |||||||

| Control | 13.88 (5.63) | 12.82 (6.20) | 13.86 (6.06) | 0.937 | 2.76 | 0.069 | 0.063 |

| Internet | 13.47 (6.39) | 14.23 (6.04) | 14.71 (6.17) | 0.954 | 2.28 | 0.108 | 0.046 |

| Internet & Routinea | 13.67 (5.85) | 15.58 (5.34) | 16.31 (5.94) | 0.811 | 9.58 | < 0.001 | 0.189 |

| Confusion | |||||||

| Control | 5.55 (3.86) | 5.77 (4.08) | 4.87 (3.77) | 0.936 | 2.80 | 0.067 | 0.064 |

| Interneta,c | 6.69 (4.16) | 5.55 (3.95) | 4.72 (4.34) | 0.725 | 17.95 | < 0.001 | 0.275 |

| Internet & Routinea,c | 5.20 (3.87) | 4.12 (2.60) | 3.38 (2.38) | 0.682 | 19.11 | < 0.001 | 0.318 |

A one way repeated measures ANOVA was utilized to analyze group differences over time.

Significant difference between baseline/week 2 and baseline/week 3.

Significant difference between baseline and week 3.

Significant difference between week 2 and week 3.

Significant interaction.

WL, Wilks lambda; ES, Effect size as partial Eta2 where 0.10 = small effect, 0.25 = moderate effect, and 0.40 = large

DISCUSSION

The results of this study indicate that an internet-based intervention that includes empirically supported behaviorally based recommendations is beneficial in improving multiple aspects of infant and toddler sleep, resulting in shorter sleep onset latency, decreased wakefulness after sleep onset, and increased sleep consolidation. Parental perception of sleep also improved, including perception of their child having a sleep problem, sleep quality, bedtime ease, and morning mood, as well as mothers' confidence in managing their child's sleep. In addition, maternal sleep and mood state improved following intervention.

One striking finding of the results presented was the large effect sizes for the primary outcome variables. There were major improvements in infant and toddler sleep, with decreases in number and duration of night wakings of 50% or more and increases in sleep continuity of over 2 hours. Similar, although less dramatic, changes were noted in maternal sleep and maternal mood. Of note is that there were minor improvements seen in the control group, primarily for sleep continuity and parental perception of a sleep problem, likely as a result of parental monitoring and increased awareness and attention to their child's sleep.

The personalized intervention included a wide variety of recommendations, based on the specific issues identified as problematic for each child. Overall, a consistent bedtime routine was recommended to all families. Many families also received recommendations involving changing negative sleep associations, decreasing nighttime feedings, and changing sleep schedules. A fewer number of families were informed to contact their primary care provider about snoring, using more absorbent diapers, or moving their child back to a crib from a bed. As noted in the research design, some families were also instructed to implement a prescribed bedtime routine that has been previously demonstrated to be efficacious.12 Interestingly, although there were no statistically significant differences in outcomes with the addition of this specific bedtime routine, effect sizes for many of the measures were slightly larger in this group than the internet-based intervention alone. Also of note, across almost all domains, the interventions were found to be efficacious after just one week, with additional benefits accruing after two weeks. Considering the fact that both a bedtime routine12 and the intervention have demonstrated benefits, future research should further explore the long-term effects of these interventions, the additive effect of combining them, and the match between child/family characteristics and the specific intervention. For instance, it could be hypothesized that for a family with more disrupted routines, the routine intervention would be more efficacious; whereas a family with more parental nighttime involvement and excessive feedings would benefit more from the sleep tool intervention.

In addition to the positive impact on the infants and toddlers, it is noteworthy that concurrent improvements were also seen in maternal sleep and mood. Mothers also reported greater confidence in their ability to manage their child's sleep and were very positive about the internet-based format of the intervention. Future studies should include measures of paternal sleep and mood, as well as family functioning to examine possible family-based effects.

Pediatricians often lack the expertise to manage these problems, which are highly prevalent in their practice.5 Additionally, internet-based interventions are clearly becoming an important resource for families with the increasing popularity of telemedicine, especially as they enable health-care provision to a wide audience who may not have access to locally based practitioners. Information prescriptions, that is, a prescription for specific, evidence-based information to manage health problems, are becoming more common and enable treatment of many issues.17,18 Not only can internet-based interventions provide widespread care, but they also appear to be a highly acceptable method of treatment delivery by parents and practitioners.19

For example, parents are highly likely to use the internet as a source for medical information and the act of looking for health information is one of the most popular uses of the internet. In addition, a recent survey found that 82% of parents report being at least somewhat interested and 22% extremely interested in an internet-based sleep-related program, with 95% of pediatric practitioners reporting that they would recommend such an internet-based intervention to their patients.20 In the broader context of sleep medicine, our findings are in line with recent studies demonstrating the efficacy of internet-based interventions for insomnia in adults.9,21,22 These studies found that internet-based interventions improved overall insomnia severity, as well as overall sleep improvements and subjective perception of sleep. These studies in conjunction with our findings demonstrate the applicability of telemedicine expanding the reach and availability of clinical interventions for common sleep problems. There are clearly limitations, however, to internet-based interventions, including lack of universal access and limited ability to tailor to every unforeseen variation in sleep issues.

There are a number of limitations to this study. First, this study did not include an objective measure of child or parental sleep, such as actigraphy. Another limitation was the lack of a longer term follow-up. It is not known whether improvements in sleep were maintained following the two-week intervention period. Future studies of the efficacy of this internet-based intervention would benefit from assessing long-term objective outcomes. Finally, this study did not allow for assessment of which particular recommendations resulted in the improvements observed. Future studies need to elucidate whether such a multi-component treatment is necessary, or whether there are certain key elements that would lead to improvement.

Overall, this study found that an internet-based intervention incorporating individualized empirically based recommendations (with and without a prescribed bedtime routine) improves sleep in infants and toddlers, as shown here with mild to moderate sleep problems. This internet-based intervention allows for provision of services to a wide audience and can easily be recommended by practicing pediatricians and other pediatric providers for the treatment of sleep problems in young children. Not only does this intervention improve sleep in young children, but it also has the indirect benefit of improving maternal well-being, specifically maternal sleep and mood.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This study was supported by Johnson & Johnson Consumer Companies, Inc. The Customized Sleep Profile is currently available to parents at no cost through Internet access. The authors do not receive financial benefit from its use. Neema Kulkarni, Lorena Telofski, and Euen Gunn are employees of Johnson & Johnson. Drs. Mindell, Du Mond, and Sadeh have consulted for Johnson and Johnson. Dr. Du Mond was responsible for data analysis and co-wrote the paper with Dr. Mindell who was the primary author. There was no involvement from Johnson & Johnson with the data analysis or the writing of the paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mindell JA, Kuhn B, Lewin DS, Meltzer LJ, Sadeh A. Behavioral treatment of bedtime problems and night wakings in infants and young children. Sleep. 2006;29:1263–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sadeh A, Mindell JA, Luedtke K, Wiegand B. Sleep and sleep ecology in the first 3 years: a web-based study. J Sleep Res. 2009;18:60–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mindell JA, Sadeh A, Wiegand B, How TH, Goh DY. Cross-cultural differences in infant and toddler sleep. Sleep Med. 2010;11:274–80. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mindell JA, Moline ML, Zendell SM, Brown LW, Fry JM. Pediatricians and sleep disorders: training and practice. Pediatrics. 1994;94:194–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Owens JA. The practice of pediatric sleep medicine: results of a community survey. Pediatrics. 2001;108:e51. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.3.e51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morgenthaler TI, Owens J, Alessi C, et al. Practice parameters for behavioral treatment of bedtime problems and night wakings in infants and young children. Sleep. 2006;29:1277–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bayer JK, Hiscock H, Hampton A, Wake M. Sleep problems in young infants and maternal mental and physical health. J Paediatr Child Health. 2007;43:66–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2007.01005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hiscock H, Bayer J, Gold L, Hampton A, Ukoumunne OC, Wake M. Improving infant sleep and maternal mental health: a cluster randomised trial. Arch Dis Child. 2007;92:952–8. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.099812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ritterband LM, Thorndike FP, Gonder-Frederick LA, et al. Efficacy of an Internet-based behavioral intervention for adults with insomnia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:692–8. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ritterband LM, Gonder-Frederick L, Cox D, Clifton AD, West RW, Borowitz S. Internet interventions: In review, in use, and into the future. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2003;34:527–34. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stinson J, Wilson R, Gill N, Yamada J, Holt J. A systematic review of internet-based self-management interventions for youth with health conditions. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009;34:495–510. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mindell J, Telofski LS, Wiegand B, Kurtz E. A nightly bedtime routine: Impact on sleep problems in young children and maternal mood. Sleep. 2009;32:599–606. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.5.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sadeh A. A brief screening questionnaire for infant sleep problems: Validation and findings for an Internet sample. Pediatrics. 2004;113:e570–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.6.e570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shacham S. A shortened version of the Profile of Mood States. J Pers Assess. 1983;47:305–6. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4703_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Curran SL, Andrykowski MA, Studts J. Short form of the Profile of Mood States (POMS-SF): Psychometric information. Psychol Assess. 1995;7:80–3. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kind T. The Internet as an adjunct for pediatric primary care. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2009;21:805–10. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e328331e7b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.D'Alessandro DM, Kreiter CD, Kinzer SL, Peterson MW. A randomized controlled trial of an information prescription for pediatric patient education on the Internet. Arch Pediatr AdolescMed. 2004;158:857–62. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.9.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ritterband LM, Borowitz S, Cox DJ, et al. Using the internet to provide information prescriptions. Pediatrics. 2005;116:e643–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thorndike FP. Commentary: Interest in internet interventions--an infant sleep program as illustration. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009;34:470–3. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vincent N, Lewycky S. Logging on for better sleep: RCT of the effectiveness of online treatment for insomnia. Sleep. 2009;32:807–15. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.6.807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strom L, Pettersson R, Andersson G. Internet-based treatment for insomnia: a controlled evaluation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:113–20. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.1.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]