Abstract

Study Objectives:

An improved animal model of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is needed for the development of effective pharmacotherapies. In humans, flexion of the neck and a supine position, two main pathogenic factors during human sleep, are associated with substantially greater OSA severity. We postulated that these two factors might generate OSA in animals.

Design:

We developed a restraining device for conditioning to investigate the effect of the combination of 2 body positions—prone (P) or supine (S)—and 2 head positions—with the neck flexed at right angles to the body (90°) or in extension in line with the body (180°)—during sleep in 6 cats. Polysomnography was performed twice on each cat in each of the 4 sleeping positions—P180, S180, P90, or S90. The effect of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) treatment was then investigated in 2 cats under the most pathogenic condition.

Setting:

NA.

Patients or Participants:

NA.

Interventions:

NA.

Measurements and Results:

Positions P180 and, S90 resulted, respectively, in the lowest and highest apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) (3 ± 1 vs 25 ± 2, P < 0.001), while P90 (18 ± 3, P < 0.001) and S180 (13 ± 5, P < 0.01) gave intermediate values. In position S90, an increase in slow wave sleep stage 1 (28% ± 3% vs 22% ± 3%, P < 0.05) and a decrease in REM sleep (10% ± 2% vs 18% ± 2%, P < 0.001) were also observed. CPAP resulted in a reduction in the AHI (8 ± 1 vs 27 ± 3, P < 0.01), with the added benefit of sleep consolidation.

Conclusion:

By mimicking human pathogenic sleep conditions, we have developed a new reversible animal model of OSA.

Citation:

Neuzeret PC; Gormand F; Reix P; Parrot S; Sastre JP; Buda C; Guidon G; Sakai K; Lin JS. A new animal model of obstructive sleep apnea responding to continuous positive airway pressure. SLEEP 2011;34(4):541-548.

Keywords: obstructive sleep apnea, animal models, body and head position, continuous positive airway pressure

INTRODUCTION

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), characterized by recurrent episodes of upper airway obstruction in sleep, affects 2% to 4% of the adult population1 and is associated with serious long-term adverse health consequences such as metabolic dysfunction,2 cardiovascular disease,3 neurocognitive deficits,4 and motor vehicle accidents.5 It has important social and economic consequences,6 and effective treatment requires a better understanding of its pathophysiology. Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP)7 is currently considered the gold standard management for OSA.8 However, the overall clinical usefulness of this approach is hampered by poor patient tolerability and compliance in up to 50% of patients.9 Few systematic attempts have been made to find new treatment strategies, particularly using pharmacological approaches,10 and no effective pharmacological treatment for OSA has been found.11 The lack of success of current pharmacological strategies is partly due to the data used being extrapolated from studies in vitro,12 in decerebrated animals,13 or in models in freely moving animal not naturally showing OSA.14,15

Several useful animal models of sleep apnea have been described during the last two decades; these include tracheostomized models in dogs,16,17 rats,18 and lambs,19 and a primate model involving the injection of small amounts of liquid collagen into tissues surrounding the upper airway.20 These approaches can be used to study the cardiovascular consequences and investigate the mechanisms that underlie OSA. However, because of the nature of these models, the investigation of neural drive to upper airway muscle is excluded. Naturally occurring OSA models have been identified in the dog21 and pig,22 but studies using these models are difficult due, in large part, to the limited availability of these animals and their relatively large size and cost. An improved animal model of OSA is therefore needed for the development of effective pharmacotherapies.

Cats have been historically used extensively for neurological research, especially in sleep research studies. In 1958, Dement,23 working on cats, described a sleep stage with low-voltage EEG, eye movements, and complete abolition of muscle potentials, later called “rapid eye movement sleep” (REM sleep). In 1959, Jouvet and colleagues described “paradoxical sleep” in cats, during which neodecorticated cats showed periodic loss of tonic neck muscle activity.24 An adult cat spends up to two-thirds of its time asleep, which, together with their small size and general tractability when socialized, have made them a popular choice as a mammalian model for sleep studies. Inspired by work from Horner's team,14 we have therefore developed, in the cat, a method for investigating neural drive to upper airway muscle (e.g., hypoglossal nucleus) during sleep, thus establishing a good animal model for studying neural mechanisms underlying OSA.

OSA syndrome is characterized by repetitive collapse of the pharynx during sleep in patients with a relatively narrow upper airway (UAW). Flexion of the neck has been shown to reduce the cross-sectional area of the UAW25 and increase UAW collapsibility in both humans26 and animals.27 In addition, a supine position is associated with more severe OSA.28,29 We therefore hypothesized that reproducing the combination of these body and head positions would generate OSA in cats.

The first aim of our study was to determine the best conditions to generate an OSA model in the nonanesthetized cat by modifying sleep body posture and head position, while the second was to substantiate the robustness of our animal model of OSA by evaluating the effect of CPAP treatment using the most pathogenic recording condition.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Experiments were performed on 6 adult male cats weighing 3.6 to 4.2 kg, born and bred in our own animal facilities. All procedures were carried out in conformity with EEC Council Directive 86/609 and were approved by the University of Lyon 1 Animal Care Committee.

Surgery

Under deep pentobarbital anesthesia (Nembutal, 25 mg/kg, i.v.), the animals were chronically implanted with standard electrodes for sleep recordings as described previously.15 In addition, a U-shaped piece of Plexiglas was fixed to the skull with acrylic cement and screws; this head-holder had transverse holes drilled into it into which bars could be inserted through holes in the box cover to permit painless restraint of the animal's head during sleep-wake recording (see Figure 1). All animals received an intramuscular injection of antibiotic (thiamphenicol) on the day after surgery, then once daily (orally) for 3 days. Food and water were available ad libitum.

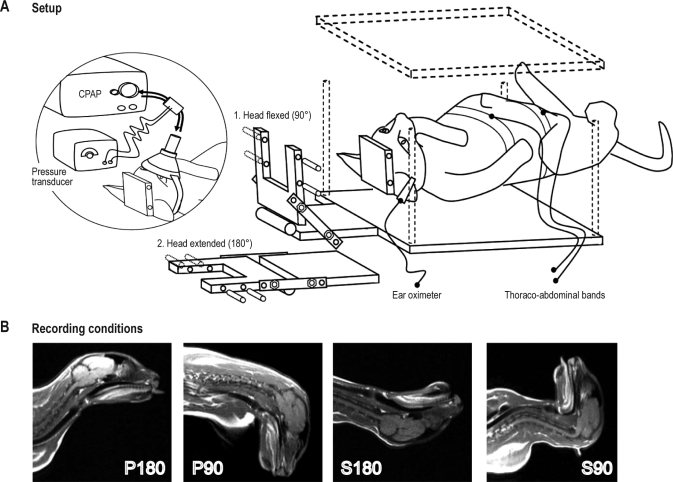

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the experimental set-up. (A) Setup. The cat is restrained in the supine position. The head can be tilted forwards at 90° (i.e., S90) or extended at 180° (i.e., P180). In the circled diagram on the left, the cat is equipped with an adapted oronasal mask used to analyze respiratory airflow and apply continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP). (B) Recording conditions. This shows the results of magnetic resonance imaging performed under anesthesia in the 4 recording conditions: P180 is the prone position with the neck in extension in line with the body, S180 the supine position with the neck in extension in line with the body, S90 the supine position with the neck in flexion at 90° to the body, and P90 the prone position with the neck in flexion at 90° to the body.

Experimental Set-Up and Animal Training

After one week of recovery, each cat was trained for 2 weeks to sleep in a hammock inside a Plexiglas box (Figure 1). During conditioning, the cats were painlessly restrained by attaching the head-holder to the cover of the box with bars inserted into the cylinders of both the U-shaped piece and the Plexiglas cover. Once fixed, the head of the cat, attached to the Plexiglas cover, could pivot in the sagittal plane and be restrained in 2 positions for recordings, with the neck either extended so that the eye axis and body axis were aligned (180°), or flexed so that the eye axis made a right angle with the body axis (90°) (Figure 1). During sleep recording, the box was placed in the recording chamber. During the first week of conditioning, the cats were trained to sleep in the 4 positions: P180 (control condition; prone position with the neck extended), S180 (supine position with the neck extended), S90 (supine position with the neck flexed at 90°), and P90 (prone position with the neck flexed at 90°); the recording duration was progressively increased to 150 min for each position. During the second week, the cats were habituated to sleep wearing an adapted mask, thoraco-abdominal bands, and an ear pulse oximeter. The cats were considered to be habituated to the experimental conditions when they displayed normal sleep-wake cycles in the apparatus during P180 (control condition).

After the 2 weeks of habituation, two 150-min polysomnographic recordings were performed during the day: in the morning from 09:00 to 11:30 and in the afternoon from 13:30 to 16:00; each cat was randomly recorded 2 times in the 4 positions.

During habituation and before each daily recording during experimental sessions, instrumental deprivation of REM sleep30 was performed to promote the REM rebound process and ensure that the animal fell asleep during recording sessions. The cats were REM deprived using the “flower pot” technique30 from 19:00 on the day before recording to 08:00 on the following day (the cat sits or squats on an inverted flower pot at the bottom of a large plastic pail filled with water to a height just below the upper level of the inverted pot). During this deprivation phase, the animal displays slow wave sleep (SWS), but cannot enter REM sleep.30

Polysomnographic Recordings

The EEG, EOG, and neck EMG data were digitized using a CED 1401 data processor (Cambridge Electronic Design (CED), Cambridge, UK) at a sampling rate of 256 Hz. All respiratory data was recorded using an Embletta PDS device (ResMed SA, Lyon, France) at a sampling rate of 20 Hz for oro-nasal flow and 10 Hz for thoracic and abdominal movements and oxygen saturation.

Oronasal inspiratory and expiratory airflow was recorded through an adapted ventilation nasal mask (IQ Mask, Sleepnet, L3medical, France) connected to a pressure transducer system (Pneumoflow, MAP, Germany). The flexible shell of the mask was molded to conform to the cat's mouth and nose. Respiratory movements were monitored by respiratory inductance plethysmography (thoracic and abdominal bands), and blood oxygen saturation (SpO2) was measured using an ear pulse oximeter (Figure 1).

Continuous Positive Airway Pressure Therapy

The effect of CPAP treatment was investigated in 2 of the cats under the condition identified as the most pathogenic (S90). A CPAP device (Autoset Spirit, ResMed, France) was used to deliver CPAP air pressure via the adapted mask (Figure 1). During CPAP treatment, an intentional leak was provided using a tube adaptor placed between the mask and the CPAP to avoid CO2 rebreathing. Unintentional leak from the mask and mouth was automatically compensated by the CPAP. A pressure sensor was installed in the mask to control the pressure delivered to the upper airway. The CPAP level was manually adjusted using a remote control outside the sleep recording room.

The cats were progressively habituated to sleep at a constant minimal pressure (4 cm H2O) for a period of 150 min. After habituation, manual titration of the CPAP pressure was performed for each cat under polysomnographic control during one 150-min session of sleep recording. The minimum starting CPAP was 4 cm H2O, and the CPAP was increased by 1 cm H2O at intervals of 3 min with the goal of eliminating obstructive respiratory events. The CPAP was increased if at least 1 obstructive apnea or 1 hypopnea was observed. If the cat awoke and showed distress due to the pressure being too high, the pressure was reduced to a comfortable level that allowed the cat to fall asleep. The same procedure was used to determine the level of CPAP to be used during SWS and REM sleep. During the experimental session, the cats were treated with the determined minimum effective pressure at which most apneas and hypopneas were abolished in, respectively, SWS and REM sleep. Three recordings of 150 min each were made from each of the 2 cats on different days during CPAP treatment.

Data Analysis

Vigilance states were scored visually 10 sec by 10 sec and classified according to the previously published standard criteria of our laboratory.15 Respiratory events were scored as apnea when there was a cessation of oronasal airflow lasting > 5 s. Hypopnea was defined as a decrease of ≥ 50% in oronasal airflow lasting > 5 s. To be considered, respiratory events had to be associated with a fall in SpO2 > 3% from the preceding baseline level and/or with arousal (respiratory arousal) or transient lightening of sleep. Arousal was defined as an abrupt change in the EEG to alpha frequencies ≥ 1 s. During REM sleep, arousals were scored if the change in the EEG was accompanied by an increase in the amplitude of the neck EMG signal. In addition, respiratory events were classified as obstructive or central according to the presence or absence of breathing efforts (asynchronous respiratory movements). As central apneas were absent or rare during recordings, they were excluded from the study. Total sleep time (TST) refers to the time a cat spent asleep and was expressed as a percentage of the recording time (150 min). The oxygen desaturation index was defined as the number of desaturation episodes > 3% below baseline per hour. Both arousals and shifts toward a lighter sleep stage, related to respiratory events, were tabulated as indexes (number per hour of sleep).

Statistical Analysis

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare all variables for P180, S180, P90, and S90 (Statel, AD Science, Paris, France); if it revealed significant differences, a paired t-test with Bonferroni correction as post hoc test was performed. A paired t-test was used to compare the effect of CPAP treatment on the 2 cats. Values are presented as the mean ± SEM, and a P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Influence of Body and Head Position and Sleep State on Occurrence of OSA (Table 1)

Table 1.

Sleep and respiration characteristics in the 4 recording positions

| P180 | S180 | P90 | S90 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 12 | N = 12 | N = 12 | N = 12 | |

| Apnea hypopnea index (n/h) | 3 ± 1 | 13 ± 5** | 18 ± 3*** | 25 ± 2*** |

| Apnea duration (sec) | 12 ± 2 | 13 ± 0.4 | 23 ± 4** | 20 ± 2* |

| Hypopnea duration (sec) | 19 ± 3 | 20 ± 1 | 37 ± 5** | 24 ± 1* |

| Desaturation epoch index (n/h) | 1 ± 1 | 2 ± 1 | 9 ± 2*** | 10 ± 2*** |

| TST, % RT | 77 ± 3 | 81 ± 3 | 68 ± 6 | 75 ± 3 |

| Wake, % TST | 23 ± 3 | 19 ± 3 | 32 ± 6 | 25 ± 3 |

| S1, % TST | 22 ± 3 | 28 ± 6 | 33 ± 3** | 28 ± 3* |

| S2, % TST | 32 ± 4 | 39 ± 8 | 22 ± 4 | 27 ± 3 |

| S-PGO, % TST | 5 ± 1 | 4 ± 1 | 8 ± 2** | 10 ± 1*** |

| REM, % TST | 18 ± 2 | 9 ± 1*** | 5 ± 2*** | 10 ± 2*** |

| Arousal index (n/h) | 2 ± 1 | 4 ± 1 | 6 ± 1*** | 8 ± 1*** |

| Shifts toward a lighter sleep stage index (n/h) | 2 ± 1 | 8 ± 3** | 6 ± 2** | 9 ± 1*** |

P180, prone position with the neck in extension in line with the body; S180, supine position with the neck in extension in line with the body; P90, prone position with the neck in flexion at 90° to the body; S90, supine position with the neck in flexion at 90° to the body; TST, total sleep time, RT; recording time (150 min), S1, slow wave sleep stage 1; S2, slow wave sleep stage 2; S-PGO, slow wave sleep stage 2 with ponto-geniculo-occipital waves PGO; REM, rapid eye movement sleep. The results are presented as the mean ± SEM. Positions S180, P90, and S90 were compared to the P180 position:

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01,

P < 0.001; if not indicated otherwise, the difference is not statistically significant.

Data comparing sleeping conditions were obtained from 6 cats.

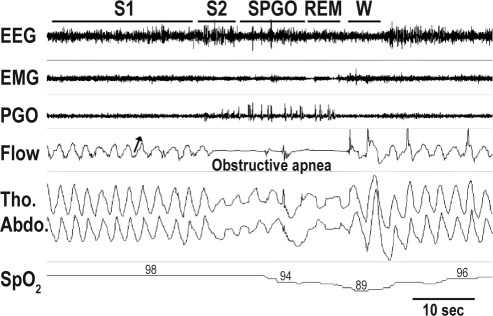

An example of UAW modification by body and head positioning, as evidenced by magnetic resonance imaging in one anesthetized cat, is shown in Figure 1. During sleep, the frequency of apneas or hypopneas increased gradually in the order AHI P180, AHI S180, AHI P90, and AHI S90. In all these sleeping positions, the obstructive apneas and hypopneas had very similar characteristics. They were associated with increased respiratory effort, as shown by out-of-phase abdominal and thoracic movements (Figure 2). Oxygen saturation (SpO2) progressively decreased during apnea and reached its lowest level just after termination of apnea, then increased slowly after a short period of normal breathing (Figure 2). Because the pathologic OSA index in adult humans is considered to be greater than 5 apneas/hypopneas per hour, we considered P180 (AHI < 5) as the “control” position. The three remaining conditions induced OSA to a greater extent (AHI > 5). Both S180 and P90 resulted in a significant increase in the AHI (S180: 13 ± 5, P < 0.01; P90: 18 ± 3, P < 0.001), but the highest AHI was seen in the S90 position when the supine position and neck flexion were combined (S90: 25 ± 2, P < 0.001, increase of 7- to 8-fold compared to the P180 control position.

Figure 2.

Example of polysomnographic recording showing an obstructive apnea in the S90 position. Note the “out-of-phase” breathing movements during obstructive apnea, indicating strong respiratory effort against upper airway obstruction. Oxygen saturation (SpO2) falls below 90% after obstructive apnea and increases slowly during a short period of normal breathing. Termination of apnea is accompanied by arousal, indicated by modifications of the EEG waveforms. The arrow indicates the direction of inspiration. EEG, electroencephalogram; EMG, electromyogram; W, wake; S1, slow wave sleep stage 1; S2, slow wave sleep stage 2; S-PGO, slow wave sleep with ponto-geniculo-occipital waves; REM, rapid eye movement sleep; Flow, bucco-nasal pressure airflow; Tho. Abdo., thoracic and abdominal movements; SpO2, oxygen saturation.

Influence of Position on Respiratory and Sleep Characteristics

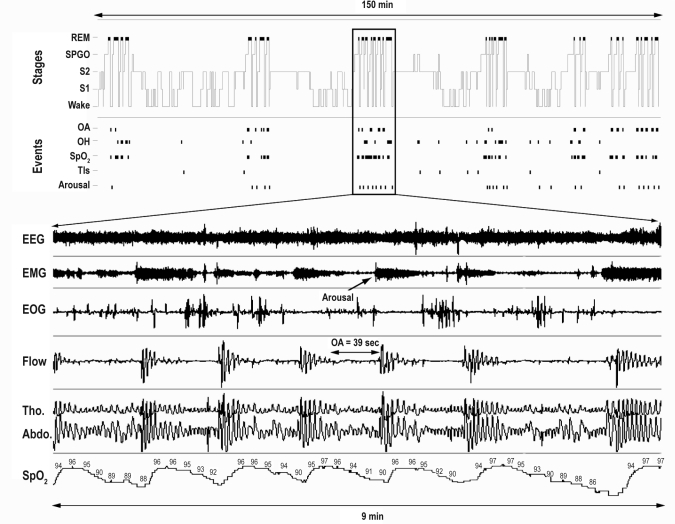

The AHI was higher during REM sleep than during SWS (58.2 ± 6 vs 19.3 ± 3, P < 0.01), showing that apneas were more frequent during REM sleep (55%) than during SWS (17%) (Figure 3). Apnea duration was similar during REM sleep and SWS (24 ± 2 sec vs 22 ± 2 sec, P = NS), while hypopneas were longer during REM sleep than during SWS (32 ± 3 sec vs 25 ± 1 sec, P < 0.01). The desaturation index showed a similar evolution to the AHI (Table 1), the highest index being seen in the S90 position (10 ± 2, P < 0.001).

Figure 3.

Example of a 150-min hypnogram recording showing the repetition of obstructive respiratory events. The figure below the hypnogram represents 9 min of a polysomnographic recording of disrupted REM sleep. Note the succession of obstructive events accompanied by consecutive falls in oxygen saturation that interrupt REM sleep. OA, obstructive apnea; OH, obstructive hypopnea; Tls, transient lightening of sleep; EOG, electrooculogram. See Figure 2 for the abbreviations of EEG, EMG, W, S1, S2, S-PGO, REM, Flow, Tho., Abdo., and SpO2.

Total sleep time (TST) was unaffected by sleeping position (Table 1). The most significant changes in sleep architecture were observed in the P90 and S90 positions. In the most pathogenic position, S90, the amount of wake was not disturbed, although the arousal index (S90: 8 ± 1 vs P180: 2 ± 1, P < 0.001) and the index of shifts toward a lighter sleep stage due to respiratory events (S90: 9 ± 1 vs P180: 2 ± 1, P < 0.001) was significantly increased. The total number of shifts to a lighter sleep stage was significantly increased (S2 to S1: 41 ± 4 vs 30 ± 4, P < 0.05; S-PGO to S2: 9 ± 2 vs 2 ± 1, P < 0.001; REM sleep to wake: 13 ± 3 vs 5 ± 0, P < 0.01). A slight increase in the percentage of S1 (S90: 28% ± 3%, P < 0.05; P90: 33% ± 3%, P < 0.01 vs P180: 22% ± 3%) was also observed. The percentage of REM sleep was decreased in positions S180, P90, and S90 (S90: 10% ± 2% vs P180: 18% ± 2%, P < 0.001, Table 1). S-PGO, which immediately precedes entry into REM sleep, was increased in positions S90 and P90 (S90: 10% ± 1% vs P180: 5% ± 1%, P < 0.001, Table 1). Of note, in the most pathogenic condition (S90), the total number of shifts from S-PGO to REM sleep was increased (S90: 14 ± 2 vs P180: 4 ± 0.3, P < 0.001).

Effect of CPAP Treatment in the S90 Position (Table 2)

Table 2.

Effect of CPAP on OSA severity and sleep stages in the S90 position

| Before CPAP | During CPAP | |

|---|---|---|

| N = 6 | N = 6 | |

| Apnea hypopnea index (n/h) | 27 ± 3 | 8 ± 1** |

| Apnea duration (sec) | 22 ± 4 | 14 ± 1* |

| Hypopnea duration (sec) | 21 ± 3 | 21 ± 3 |

| Desaturation epoch index (n/h) | 14 ± 1 | 2 ± 1** |

| TST, % RT | 79 ± 1 | 83 ± 3 |

| Wake, % TST | 19 ± 1 | 17 ± 3 |

| S1, % TST | 17 ± 2 | 17 ± 2 |

| S2, % TST | 36 ± 2 | 39 ± 2 |

| S-PGO, % TST | 9 ± 1 | 4 ± 0.5* |

| REM, % TST | 13 ± 0.5 | 24 ± 6* |

| Arousal index (n/h) | 8 ± 3 | 2 ± 1** |

| Shifts toward a lighter sleep stage index (n/h) | 3 ± 1 | 1 ± 0.2* |

CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; S90, supine position with the neck in flexion at 90° to the body; TST, total sleep time; RT, recording time (150 min); S1, slow wave sleep stage 1; S2, slow wave sleep stage 2; S-PGO, slow wave sleep stage 2 with ponto-geniculo-occipital waves; REM, rapid eye movement sleep. The results are presented as the mean ± SEM. S90 during CPAP was compared with S90 before CPAP in the 2 cats:

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01; if not indicated otherwise, the difference is not statistically significant.

To further characterize our model and reinforce its clinical relevance, CPAP was applied to 2 cats in position S90, the most pathogenic condition, to test its effect on OSA occurrence. The 2 cats had similar AHIs to the other 4 cats (27 ± 3 vs 25 ± 2, P = NS). During CPAP application, the mean pressure delivered at the mask was 6 cm H2O during SWS and 15.9 cm H2O during REM sleep. CPAP treatment resulted in a reduced AHI (8 ± 1 vs 27 ± 3, P < 0.01) and desaturation index (2 ± 1 vs 14 ± 1, P < 0.01). The AHIs during SWS (11 ± 2 vs 4 ± 1, P < 0.05) and REM sleep (82 ± 12 vs 31 ± 12, P < 0.05) were significantly decreased. In particular, CPAP treatment reduced S-PGO sleep (4% ± 0.5% vs 9% ± 1%, P < 0.05) and increased REM sleep (24% ± 6% vs 13% ± 0.5%, P < 0.05). The arousal index (2 ± 1 vs 8 ± 3, P < 0.01) and the index of shifts toward a lighter stage of sleep (1 ± 0.2 vs 3 ± 1, P < 0.05) were also significantly decreased.

DISCUSSION

We have developed a new animal model of obstructive sleep apnea with several important attributes. This is the first model involving sleep-related pharyngeal collapse of soft tissue. The frequency, and thus the severity, of obstructive events can be manipulated to model mild, moderate, or severe OSA; in addition, the saturation falls within the range most commonly observed clinically. The obstruction can be reversed by changing the position or by CPAP, and the observation that a worse effect is seen in the supine position models the human disease.

Replication of Major Human Pathogenic Factors in the Cat Generates OSA

We found that the AHI was highest in the S90 position—the order being AHI S90 > AHI P90 > AHI S180 > AHI P180— and that the combination of supine position and neck flexion (S90) resulted in severe OSA in the cat. These results are consistent with previous studies showing that (i) supine sleep can generate obstructive apneas in humans29 and that (ii) neck flexion can strongly influence airway collapsibility in both humans25,31,32 and animals.33 In our model, the S90 position more closely replicated the anatomical conditions favorable to UAW obstruction observed in human OSA pathology. In the S90 position, the longitudinal axis of the tongue can pivot perpendicularly to the posterior pharyngeal wall, thus mechanically increasing the gravitational force on the genioglossus. Thus, with the additive collapsing force due to the decrease in genioglossus muscle activity during sleep,15 the cat may be unable to maintain pharyngeal patency. Interestingly, head flexion also significantly increased the AHI in the prone position, although to a lesser extent. Although the mechanism is still unclear, the hypotonia of the soft tissue muscles that surround the pharyngeal airway, together with the decrease in the lumen induced by head flexion, probably contributes to UAW obstruction.

Surprisingly, with head extension, although body position still had an effect on the occurrence of OSA, it was less drastic. Indeed, head extension in a supine sleeping position may partly preserve upper airway patency, probably by increasing the UAW cross-sectional area as a result of the “head tilt-chin lift” maneuver used in cardiopulmonary resuscitation to create an open airway in humans. In addition, it has been shown that neck extension dilates the upper airway25,34 and makes it more rigid, improving pharyngeal airway patency25 in humans. Recently, a study has shown that a cervical pillow that promotes neck extension can improve sleep disordered breathing in OSA patients by increasing the cross-sectional area.35

Obstructive Apnea and Sleep Stage

In human adults, half of OSA patients have a higher AHI during SWS than during REM sleep,36 while in children, the majority of obstructive events occur during REM sleep.37 In our model, cats in the worst apneic position (S90) had a higher AHI during REM sleep than during SWS. During REM sleep, the greater reduction in UAW muscle activity15 and in muscle reflex activation38 increases the vulnerability of the UAW to collapse. It is well known that episodes of breathing disorders are more severe during REM sleep than during SWS in both humans39 and the English bulldog.21 Furthermore, an increase in the propensity of REM sleep during recording due to the previous REM sleep deprivation used in our model might partly explain this higher REM sleep AHI.

On the other hand, despite the REM sleep pressure induced by previous REM sleep deprivation, the amount of REM sleep was significantly reduced in our model. This REM sleep deficit was accompanied by an increased REM sleep propensity, as suggested by the increase in the number of S-PGO to REM sleep transition attempts and in the percentage of S-PGO sleep (the stage which announces the imminent onset of REM sleep), which can be interpreted as representing the build-up of a pressure that homeostatically regulates REM sleep.40 In the same way, in sleep apnea patients, a chronic REM sleep deficit is usually suggested to explain the REM rebound observed during the first night of CPAP therapy.41 In the canine model of induced OSA, although the amount of REM sleep is similar before and during OSA,42 REM sleep rebound is still seen during the recovery phase after induction of OSA, again suggesting a REM sleep alteration. The authors suggested that apnea-related REM sleep fragmentation and/or repetitive hypoxia might be responsible, rather than a REM sleep deficit per se.

Effective Application of CPAP for OSA Treatment in the Feline Model

To our knowledge, this is the first report of CPAP being used as an effective treatment for OSA in an animal model. CPAP probably prevents obstructive events by providing a pneumatic splint that anteriorly displaces collapsible tissue (e.g., genioglossus muscle), preventing occlusion of the airway. Initially, we applied a single higher pressure across all wake-sleep cycles, alleviating most obstructive apneas during REM sleep. We then changed to using a bilevel pressure, with a lower pressure during SWS and a higher pressure during REM sleep. The use of a single higher pressure for the entire recording increased pressure intolerance and was associated with a poor ability to fall asleep and reduced acceptance of CPAP treatment, as reported in some patients.43 A higher pressure requirement during REM sleep than SWS has also been reported in humans, but the difference is not as great,44,45 probably because of the severity of apnea seen during REM sleep in our model.

As previously described in humans,46,47 in the cat, CPAP treatment resulted in better sleep quality, with fewer arousals and a reduced number of sleep stage shifts, and an increase in REM sleep. The rebound phenomenon was especially pronounced in REM sleep, as described previously during the first night of treatment in human OSA.46 Interestingly in OSA patients, REM sleep rebound has been shown to be correlated with apnea severity during CPAP polysomnography.47 As apneas are more severe and more frequent during REM sleep, it is logical that their elimination by CPAP treatment greatly increased the amount of REM sleep in our model.

A Useful New Animal Model for Studying OSA

Our cat model is less like the natural obese pig model22 and more like the dog model, in which the UAW presents a marked narrowing that is not obesity-related. Indeed, our model highlights the interaction of anatomic pharyngeal factors and neural state-related factors in producing pharyngeal collapse. Although obesity is a known risk factor for the development of OSA,48 our study did not address this factor. However, it is conceivable that, in the near future, the obese cat could be studied using the same method presented here. This would add clinical pertinence to our model and make it possible to determine the weight of each of these factors in the occurrence of OSA.

Concerning severity, OSA in cats appears to be more severe than that in obese pigs, which only display sleep disordered breathing characterized by increased resistance to airflow, snoring, and inspiratory flow limitation.49 As in the English bulldog,21 apneas in our cat model were worse and more frequent during REM sleep. Other models have been developed in which severe apneas can be induced using mechanical occlusion of the airway.16,18 Although somewhat useful in investigating the mechanisms involved in the adverse cardiovascular consequences of OSA before and following induction of OSA, these induced models interfere with UAW dynamics by instrumental modification and/or alteration of motor airway control by anesthesia. In contrast, our cat model preserves full neural drive to the upper airway dilator muscles, and this will allow us to investigate the neural mechanisms by which the upper airway muscles (e.g., the genioglossus muscle) are regulated using a method developed for manipulation of neurotransmission at the hypoglossal nucleus in freely moving animals.15 However, in the form described here, our model can be described as acute in comparison to the chronic OSA dog model.21 Currently, we are inducing OSA for 7-8 h each day and for a longer period (up to 4 months), which is closer to a chronic condition and more similar to the sleep duration in human beings.

Few attempts have been made to reproduce OSA in animals by mimicking human sleeping positions or by modifying UAW patency. In the anesthetized rabbit, the supine sleeping position was investigated, but only inspiratory flow limitation was described.50 In agreement with the data obtained in this model, our results showed only a few obstructive apneas when the cats were positioned in the supine position, suggesting that body position alone could not generate OSA. OSA is mostly reported in humans showing a specific conformation of UAW anatomy imposed by an upright posture, which leads to flexion of the head on the neck. Taking advantage of this primate airway conformation, Philips et al.20 developed a model of sleep disordered breathing in monkeys by expanding the lateral pharyngeal wall with collagen injections and induced hypopnea in the supine sleeping position, but did not observe obstructive apnea.

Methodological Considerations

Initially, several strategies were attempted to train the cats to sleep in the apparatus contention by progressive conditioning and without sleep deprivation. However, cats sleeping on their backs did not exhibit a normal sleep architecture even after several days of training, probably due to the fact that this is an unusual position for a naturally sleeping cat. As only a low amount of REM sleep was observed in these conditions, selective REM sleep deprivation was performed before each recording, as described previously.30 After REM sleep deprivation, the cats exhibited sleepiness due to the lack of deep sleep and readily fell asleep as soon as they were settled in the retraining apparatus for conditioning. Furthermore, previous sleep deprivation exacerbated OSA severity by increasing the amount of REM sleep during recording. Indeed, as shown in patients with OSA, sleep deprivation worsens obstructive apneas,51 probably by aggravating the muscle tone decrease seen with increased depth of sleep.

In this study, a 5-s minimal duration was chosen for defining respiratory events, since cats have a smaller respiratory capacity than humans and their respiratory rate as much as twice that in humans. A 5-s duration is therefore clinically relevant in the cat, since these respiratory events resulted in significant transient SpO2 reduction and frequent EEG arousal. This criterion is similar to that used in the definition of apnea in children.52

CONCLUSIONS

To our knowledge, this is the first description of a nonanesthetized animal model in which OSA is induced by mimicking human sleeping conditions. We have developed a new animal model of OSA by replicating sleeping pathogenic factors identified in humans. As in human patients suffering from OSA, our model shows a disturbance of sleep architecture (decreased REM sleep and increased slight slow wave sleep) associated with obstructive respiratory events. Apnea is relieved by changing sleeping position or by applying CPAP treatment. This new robust animal model of OSA provides a useful tool for investigating the pathogenic mechanisms underlying OSA and for improving and developing new pharmacological strategies.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank P. Lévy (Rehabilitation and Physiology Department, Grenoble University Hospital) and R.L. Horner (Department of Medicine, University of Toronto) for providing scientific advice, J.P. Pracros and P. Né (Department of Pediatric Radiology, Hospital Debrousse, Lyon) for providing expert assistance with the magnetic resonance imaging, and G. Rouffet (Resmed, France) for expert advice about technical respiratory records.

This work was supported by INSERM U1028 and University Lyon 1. The authors thank ADIR (Aides à Domicile aux Insuffisants Respiratoires, Isneauville, France) and ANTADIR (Association Nationale pour les Traitements à Domicile, les Innovations et la Recherche, Paris, France) and Weinmann (Hambourg, Germany) for fellowships.

REFERENCES

- 1.Young T. Analytic epidemiology studies of sleep disordered breathing--what explains the gender difference in sleep disordered breathing? Sleep. 1993;16:S1–2. doi: 10.1093/sleep/16.suppl_8.s1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levy P, Bonsignore MR, Eckel J. Sleep, sleep-disordered breathing and metabolic consequences. Eur Respir J. 2009;34:243–60. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00166808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Somers VK, White DP, Amin R, et al. Sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease: an American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Foundation Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association Council for High Blood Pressure Research Professional Education Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke Council, and Council on Cardiovascular Nursing. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:686–717. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Engleman HM, Douglas NJ. Sleep. 4: Sleepiness, cognitive function, and quality of life in obstructive sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome. Thorax. 2004;59:618–22. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.015867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teran-Santos J, Jimenez-Gomez A, Cordero-Guevara J. The association between sleep apnea and the risk of traffic accidents. Cooperative Group Burgos-Santander. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:847–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903183401104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.AlGhanim N, Comondore VR, Fleetham J, Marra CA, Ayas NT. The economic impact of obstructive sleep apnea. Lung. 2008;186:7–12. doi: 10.1007/s00408-007-9055-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sullivan CE, Issa FG, Berthon-Jones M, Eves L. Reversal of obstructive sleep apnoea by continuous positive airway pressure applied through the nares. Lancet. 1981;1:862–5. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)92140-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strollo PJ, Jr, Rogers RM. Obstructive sleep apnea. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:99–104. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199601113340207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zozula R, Rosen R. Compliance with continuous positive airway pressure therapy: assessing and improving treatment outcomes. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2001;7:391–8. doi: 10.1097/00063198-200111000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hedner J, Grote L, Zou D. Pharmacological treatment of sleep apnea: current situation and future strategies. Sleep Med Rev. 2008;12:33–47. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horner RL. Respiratory motor activity: influence of neuromodulators and implications for sleep disordered breathing. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2007;85:155–65. doi: 10.1139/y06-089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berger AJ, Bayliss DA, Viana F. Modulation of neonatal rat hypoglossal motoneuron excitability by serotonin. Neurosci Lett. 1992;143:164–8. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90257-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kubin L, Tojima H, Davies RO, Pack AI. Serotonergic excitatory drive to hypoglossal motoneurons in the decerebrate cat. Neurosci Lett. 1992;139:243–8. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90563-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jelev A, Sood S, Liu H, Nolan P, Horner RL. Microdialysis perfusion of 5-HT into hypoglossal motor nucleus differentially modulates genioglossus activity across natural sleep-wake states in rats. J Physiol. 2001;532:467–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0467f.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neuzeret PC, Sakai K, Gormand F, et al. Application of histamine or serotonin to the hypoglossal nucleus increases genioglossus muscle activity across the wake-sleep cycle. J Sleep Res. 2009;18:113–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kimoff RJ, Makino H, Horner RL, et al. Canine model of obstructive sleep apnea: model description and preliminary application. J Appl Physiol. 1994;76:1810–7. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.76.4.1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O'Donnell CP, King ED, Schwartz AR, Robotham JL, Smith PL. Relationship between blood pressure and airway obstruction during sleep in the dog. J Appl Physiol. 1994;77:1819–28. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.77.4.1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farre R, Rotger M, Montserrat JM, Calero G, Navajas D. Collapsible upper airway segment to study the obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome in rats. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2003;136:199–209. doi: 10.1016/s1569-9048(03)00082-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fewell JE, Williams BJ, Szabo JS, Taylor BJ. Influence of repeated upper airway obstruction on the arousal and cardiopulmonary response to upper airway obstruction in lambs. Pediatr Res. 1988;23:191–5. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198802000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Philip P, Gross CE, Taillard J, Bioulac B, Guilleminault C. An animal model of a spontaneously reversible obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in the monkey. Neurobiol Dis. 2005;20:428–31. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hendricks JC, Kline LR, Kovalski RJ, O'Brien JA, Morrison AR, Pack AI. The English bulldog: a natural model of sleep-disordered breathing. J Appl Physiol. 1987;63:1344–50. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1987.63.4.1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lonergan RP, 3rd, Ware JC, Atkinson RL, Winter WC, Suratt PM. Sleep apnea in obese miniature pigs. J Appl Physiol. 1998;84:531–6. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.84.2.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dement W. The occurrence of low voltage, fast, electroencephalogram patterns during behavioral sleep in the cat. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1958;10:291–6. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(58)90037-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jouvet M, Michel F. [Electromyographic correlations of sleep in the chronic decorticate & mesencephalic cat.] C R Seances Soc Biol Fil. 1959;153:422–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Isono S, Tanaka A, Tagaito Y, Ishikawa T, Nishino T. Influences of head positions and bite opening on collapsibility of the passive pharynx. J Appl Physiol. 2004;97:339–46. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00907.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Isono S, Remmers JE, Tanaka A, Sho Y, Nishino T. Static properties of the passive pharynx in sleep apnea. Sleep. 1996;19:S175–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Odeh M, Schnall R, Gavriely N, Oliven A. Dependency of upper airway patency on head position: the effect of muscle contraction. Respir Physiol. 1995;100:239–44. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(94)00135-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pevernagie DA, Shepard JW., Jr Relations between sleep stage, posture and effective nasal CPAP levels in OSA. Sleep. 1992;15:162–7. doi: 10.1093/sleep/15.2.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cartwright RD. Effect of sleep position on sleep apnea severity. Sleep. 1984;7:110–4. doi: 10.1093/sleep/7.2.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jouvet D, Vimont P, Delorme F, Jouvet M. [Study of selective deprivation of the paradoxal sleep phase in the cat.] C R Seances Soc Biol Fil. 1964;158:756–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liistro G, Stanescu D, Dooms G, Rodenstein D, Veriter C. Head position modifies upper airway resistance in men. J Appl Physiol. 1988;64:1285–8. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1988.64.3.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choi JK, Goldman M, Koyal S, Clark G. Effect of jaw and head position on airway resistance in obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Breath. 2000;4:163–8. doi: 10.1007/s11325-000-0163-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Odeh M, Schnall R, Gavriely N, Oliven A. Dependency of upper airway patency on head position: the effect of muscle contraction. Respir Physiol. 1995;100:239–44. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(94)00135-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jan MA, Marshall I, Douglas NJ. Effect of posture on upper airway dimensions in normal human. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149:145–8. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.1.8111573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kushida CA, Rao S, Guilleminault C, et al. Cervical positional effects on snoring and apneas. Sleep Res Online. 1999;2:7–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Siddiqui F, Walters AS, Goldstein D, Lahey M, Desai H. Half of patients with obstructive sleep apnea have a higher NREM AHI than REM AHI. Sleep Med. 2006;7:281–5. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goh DY, Galster P, Marcus CL. Sleep architecture and respiratory disturbances in children with obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:682–6. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.2.9908058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eckert DJ, McEvoy RD, George KE, Thomson KJ, Catcheside PG. Genioglossus reflex inhibition to upper-airway negative-pressure stimuli during wakefulness and sleep in healthy males. J Physiol. 2007;581:1193–205. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.132332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Findley LJ, Wilhoit SC, Suratt PM. Apnea duration and hypoxemia during REM sleep in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 1985;87:432–6. doi: 10.1378/chest.87.4.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Benington JH, Woudenberg MC, Heller HC. REM-sleep propensity accumulates during 2-h REM-sleep deprivation in the rest period in rats. Neurosci Lett. 1994;180:76–80. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90917-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Issa FG, Sullivan CE. The immediate effects of nasal continuous positive airway pressure treatment on sleep pattern in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1986;63:10–7. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(86)90056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Horner RL, Brooks D, Kozar LF, et al. Sleep architecture in a canine model of obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 1998;21:847–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oksenberg A, Silverberg DS, Arons E, Radwan H. The sleep supine position has a major effect on optimal nasal continuous positive airway pressure : relationship with rapid eye movements and non-rapid eye movements sleep, body mass index, respiratory disturbance index, and age. Chest. 1999;116:1000–6. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.4.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marrone O, Insalaco G, Bonsignore MR, Romano S, Salvaggio A, Bonsignore G. Sleep structure correlates of continuous positive airway pressure variations during application of an autotitrating continuous positive airway pressure machine in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Chest. 2002;121:759–67. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.3.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Polo O, Berthon-Jones M, Douglas NJ, Sullivan CE. Management of obstructive sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome. Lancet. 1994;344:656–60. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92089-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Issa FG, Sullivan CE. The immediate effects of nasal continuous positive airway pressure treatment on sleep pattern in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1986;63:10–7. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(86)90056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Verma A, Radtke RA, VanLandingham KE, King JH, Husain AM. Slow wave sleep rebound and REM rebound following the first night of treatment with CPAP for sleep apnea: correlation with subjective improvement in sleep quality. Sleep Med. 2001;2:215–23. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(00)00069-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Young T, Shahar E, Nieto FJ, et al. Predictors of sleep-disordered breathing in community-dwelling adults: the Sleep Heart Health Study. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:893–900. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.8.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tuck SA, Dort JC, Olson ME, Remmers JE. Monitoring respiratory function and sleep in the obese Vietnamese pot- bellied pig. J Appl Physiol. 1999;87:444–51. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.87.1.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bellemare F, Pecchiari M, Bandini M, Sawan M, D'Angelo E. Reversibility of airflow obstruction by hypoglossus nerve stimulation in anesthetized rabbits. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:606–12. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200502-190OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Persson HE, Svanborg E. Sleep deprivation worsens obstructive sleep apnea. Comparison between diurnal and nocturnal polysomnography. Chest. 1996;109:645–50. doi: 10.1378/chest.109.3.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sanchez-Armengol A, Capote-Gil F, Cano-Gomez S, Ayerbe-Garcia R, Delgado-Moreno F, Castillo-Gomez J. Polysomnographic studies in children with adenotonsillar hypertrophy and suspected obstructive sleep apnea. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1996;22:101–5. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-0496(199608)22:2<101::AID-PPUL4>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]