Abstract

Aim:

The aim was to describe how a multidisciplinary medical assessment changed the distribution of long-term sickness absentees between three different forms of social security support during a period of eleven years.

Methods:

The study group (n = 1002) consisted of persons on long-term sickness absence who were referred to a multidisciplinary medical assessment by the Social Insurance Office in Stockholm, Sweden between 1998 and 2007. Register data from the years 1993–2008 were linked to the study group. A calculation was provided for the number of days per person and year on unemployment benefits, sickness benefits, and disability pension, five years before, during, and five years after the assessment. Also, differences in the average number of days per person and year were calculated with one-way analysis of variance.

Results:

The number of days on sickness benefits increased up to the time of multidisciplinary medical assessment, from 69 to 218 days on average. After the assessment there was a decrease in the average number of days on sickness benefits, from 218 to 16 days. Before the assessment the number of days on disability pension was 21, but this increased after the assessment from 104 days to an average of 272 days five years after the assessment. There were age differences regarding number of compensated days, and these were particularly pronounced for disability days after the assessment. Further, there were significant differences between types of diagnosis in relation to average days on disability pension after the assessment.

Conclusion:

The study shows that after a multidisciplinary medical assessment there is a rapid increase in disability pension and a dramatic decrease in sickness benefits. The results indicate that for a large number of persons, a Social Insurance Office referral to an assessment does not improve their chances of returning to work, but rather seems to justify disability pension.

Keywords: multidisciplinary medical assessment, sickness absence, disability pension, sick leave, diagnosis, Sweden

Introduction

Long-term sickness absence (SA) and disability pension (DP) are seen as major public health and socioeconomic problems in many Western countries.1,2 Research during recent decades has mainly focused on the reasons why individuals and groups of individuals become sick-listed or take early retirement due to sickness and incapacity, but also on why the numbers have varied over time.3–5

Less research has been published on the effects of SA or having been granted DP. However, there are a few studies on the short- or long-term effects of having been on different forms of social security support.6,7 It has been shown that long periods of SA reduce the likelihood of returning to work and increase the risk of DP.4,8–13 Andren14 found that SA is a strong predictor for exit from the labor market through full or partial DP, unemployment, or emigration. Although other factors such as age and educational level affect the risk of DP after long spells of SA, the length of SA remains an important factor.15 Wallman et al16 found that the number of annual days of SA had the best prognostic precision for DP compared with other predictors such as age, length of education, and geographical area. Several other studies have also found that previous SA increases the risk of long-term SA and DP.11,17–21

Also, a number of studies have indicated that factors other than health are important in association with return-to-work (RTW) or DP.7,22–26 Low socioeconomic position, exposures to physical, psychosocial, or organizational factors at work, and high age increased the risk of DP.27

In Sweden, a correlation between the number of long-term SA cases and trends in numbers of new DPs has been reported.28 Both DP and compensation for long-term SA are granted on the basis of reduction of work capacity due to a disease or an injury.29 The individual’s social or labor market conditions are not formally assumed to affect the decision. For this reason, the assessment of medical conditions related to the individual’s work capacity is crucial. This is particularly important in relation to prolonged cases of SA and in deciding about permanent DP. However, in many cases of long-term SA the severity of the disease, its prognosis, and the rehabilitation potential of the individual are not well known by the Social Insurance Office (SIO). In the Swedish social security administration, different forms of intensified medical examinations are used to meet the need for a systematic assessment of health conditions, work capacity, and useful medical and vocational rehabilitation measures. The results of such examinations are assumed to improve the decision about whether the individual can RTW with or without rehabilitation measures. As DP is in most cases irreversible, it involves severe financial and social consequences for the individual and high costs for society.

Thus, the idea behind the SIO’s referral of an individual to a systematic multidisciplinary medical assessment (MMA) is to get better information about the individual’s health and work capacity. The primary assumption is that MMA provides a valid foundation for the insurance officials to decide on the sickness absentee’s right to benefits and need for further work-related rehabilitation. However, it is known that the MMA is in most cases conducted at a relatively late stage of an SA process and that a large number of individuals will not return to work after the MMA.10,11,30 What is not known is the mobility between different forms of social security compensation that takes place after an MMA, and to what degree the selection in this mobility is primarily due to health conditions or to other factors such as age, education, or sex.

In a Danish study (page 300),25 RTW was measured in terms of “whether one received public transfer income or not in a given time period” and some 7,800 individuals who had been on SA for more than 8 weeks were followed over 2–3 years (page 300). After one year, the majority had no public transfer income, and was thus assumed to have returned to work, and within 2 years almost 60% received no public transfer. After that there was no increase and about 40% remained in some form of public compensation. RTW decreased with increasing age, low education, low income, female sex, and immigrant status.

The present study describes how the use of different kinds of social security benefits has developed over a period of eleven years among long-term sickness absentees that have undergone an MMA. The individuals are followed five years before the MMA and five years after. The main aim was to investigate the number of days of different forms of social security compensation among long-term sickness absentees, five years before, during, and five years after MMA. Specific aims were to analyse the shifts in the number of days on social security benefits per person and year with respect to three forms of compensation: unemployment benefits, sickness benefits, and DP. Further objectives were to study differences in the average number of days for each form of compensation related to sex, age, education, country of birth, and diagnosis.

Methods

Participants and procedure

The study group consisted of persons on long-term SA who underwent an MMA at the Diagnostic Center (DC), Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden, from 1998 to 2007 (see earlier studies31–33). At the MMA, all individuals completed a comprehensive questionnaire before medical examinations. The questionnaire included items about socio-demographics, social life, lifestyle, health, and symptoms. Each individual was examined on three different occasions within three weeks by three board-certified specialists in psychiatry, orthopedic surgery, and rehabilitation medicine, respectively. For each individual, the three specialists thereafter agreed on a joint statement with respect to diagnoses, level of work capacity, prognosis of return to work, and recommendation of medical and vocational rehabilitation measures. Most of the persons had been on SA for more than one year and had been referred to a MMA by the SIO. A total of 1,006 persons were examined over the period from 1998 to 2007, and the number of persons referred varied between 25 and 181 for the individual year.

Exclusion criteria

Persons who were entitled to old age pension when they turned 65 years of age (n = 14) or died (n = 20) during the follow-up period were excluded from the study group for the years post these events. Immigrants (n = 14) and emigrants (n = 10) were excluded for the years they were not resident in Sweden.

Study design

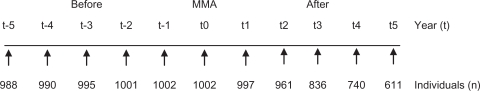

Figure 1 presents a description of the longitudinal study design. The persons were followed five years before, during, and five years after the year of the MMA. Information about the individuals was collected during the MMA. The follow-up data originate from databases from Statistics Sweden (LISA) and the Swedish Social Insurance Agency (MiDAS) about the annual numbers of days on different kinds of social security compensation for each individual during the period 1993–2008, linked to the study group. Individuals who underwent MMA after 2004 could not be followed during all five years. Thus the number of cases was reduced for each year after 2004 by 25, 144, 235, and 351.

Figure 1.

Design of the study. Number of years and participating individuals before (t-5 to t-1), during (t0), and after (t1 to t5) a multidisciplinary medical assessment at the diagnostic center.

Background variables

The background factors used were sex, age, education, country of birth, and diagnoses, categorized as follows: age categories (21–39, 40–49, 50–63 years), educational level (elementary, high school, university), country of birth (Sweden, other than Sweden), type of diagnosis (psychiatric, somatic, psychiatric and somatic, or none).

Outcome variables

Unemployment benefits: number of days per person and year with unemployment compensation, labor market education, sheltered employment. Days with part-time compensation were added to make full days.

Sickness benefits: number of days per person and year on sickness benefits, rehabilitation allowance, occupational injury allowance, preventive sick leave allowance, disease carrier’s allowance. Days on part-time compensation were added to make full days.

Disability pension: number of days per person and year with permanent or temporary DP. Days on part-time compensation were added to make full days.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to illustrate how the average number of days on different kinds of social security benefits had developed. The data were computed in two steps. In the first step, a calculation was provided for the number of days per person and year on unemployment benefits, sickness benefits, and DP. This was done for each year over the eleven-year period, ie, five years before the MMA, during the MMA year, and five years after the MMA. The information was based on register data for the period 1993–2008. In the second step, differences in the average number of days per person and year were calculated with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for each form of compensation related to sex, age, education, country of birth, and diagnosis (F-values and df were computed but not presented in Table 2). Also, cross-tabulation of sex by background variables was analyzed using the Chi-square test (Table 1). All P-values reported are statistically significant at the 5% level. Data were analysed using SPSS/PASW statistical programme package (version 17; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL).

Table 2.

Number of days on disability pension, sickness benefits, and unemployment related to sex, age, education, country of birth, and diagnosis

| Y |

Sex |

Age |

Education |

Country of birth |

Diagnosis |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W | M | P | <39 | <49 | <63 | P | E | H | U | P | O | SW | P | S | P | SP | P | |

| Disability pension | ||||||||||||||||||

| t-5 | 24 | 15 | 0.062 | 17 | 26 | 17 | 0.150 | 23 | 18 | 19 | 0.634 | 16 | 24 | 0.124 | 17 | 24 | 22 | 0.548 |

| t-4 | 32 | 20 | 0.038 | 24 | 36 | 21 | 0.045 | 32 | 23 | 27 | 0.396 | 24 | 31 | 0.194 | 25 | 32 | 29 | 0.657 |

| t-3 | 42 | 28 | 0.027 | 37 | 44 | 29 | 0.139 | 40 | 36 | 34 | 0.733 | 34 | 39 | 0.414 | 31 | 40 | 40 | 0.434 |

| t-2 | 63 | 51 | 0.124 | 52 | 72 | 49 | 0.015 | 61 | 63 | 47 | 0.239 | 54 | 61 | 0.348 | 51 | 54 | 66 | 0.184 |

| t-1 | 83 | 72 | 0.216 | 67 | 96 | 70 | 0.009 | 81 | 84 | 70 | 0.445 | 77 | 80 | 0.775 | 65 | 72 | 92 | 0.026 |

| t0 | 111 | 94 | 0.061 | 90 | 115 | 104 | 0.078 | 112 | 104 | 93 | 0.234 | 105 | 104 | 0.889 | 84 | 105 | 119 | 0.005 |

| t1 | 192 | 187 | 0.596 | 151 | 192 | 218 | <0.001 | 208 | 182 | 173 | 0.008 | 207 | 178 | 0.002 | 147 | 197 | 217 | <0.001 |

| t2 | 244 | 239 | 0.613 | 199 | 241 | 276 | <0.001 | 263 | 233 | 223 | 0.001 | 267 | 224 | <0.001 | 205 | 255 | 263 | <0.001 |

| t3 | 264 | 261 | 0.778 | 217 | 264 | 295 | <0.001 | 279 | 256 | 246 | 0.015 | 284 | 248 | <0.001 | 236 | 274 | 279 | 0.001 |

| t4 | 268 | 265 | 0.715 | 230 | 269 | 295 | <0.001 | 285 | 258 | 250 | 0.014 | 286 | 252 | 0.001 | 237 | 278 | 282 | 0.001 |

| t5 | 277 | 264 | 0.268 | 232 | 276 | 301 | <0.001 | 292 | 262 | 250 | 0.006 | 293 | 255 | 0.001 | 244 | 280 | 288 | 0.005 |

| Sickness benefits | ||||||||||||||||||

| t-5 | 68 | 71 | 0.698 | 62 | 79 | 64 | 0.099 | 69 | 72 | 66 | 0.828 | 68 | 69 | 0.881 | 63 | 60 | 79 | 0.059 |

| t-4 | 92 | 95 | 0.808 | 85 | 111 | 80 | 0.003 | 80 | 106 | 96 | 0.022 | 83 | 100 | 0.041 | 79 | 77 | 110 | 0.001 |

| t-3 | 122 | 127 | 0.617 | 108 | 136 | 121 | 0.050 | 114 | 127 | 133 | 0.242 | 105 | 137 | 0.001 | 111 | 104 | 140 | 0.002 |

| t-2 | 150 | 163 | 0.193 | 152 | 153 | 159 | 0.775 | 148 | 157 | 163 | 0.452 | 148 | 161 | 0.162 | 135 | 159 | 164 | 0.030 |

| t-1 | 189 | 208 | 0.064 | 201 | 190 | 199 | 0.597 | 187 | 199 | 207 | 0.251 | 195 | 197 | 0.849 | 185 | 211 | 194 | 0.136 |

| t0 | 211 | 230 | 0.053 | 225 | 215 | 215 | 0.656 | 213 | 218 | 226 | 0.582 | 223 | 214 | 0.339 | 227 | 226 | 208 | 0.176 |

| t1 | 122 | 118 | 0.722 | 139 | 126 | 101 | 0.002 | 112 | 124 | 129 | 0.274 | 120 | 121 | 0.924 | 149 | 115 | 104 | <0.001 |

| t2 | 60 | 58 | 0.784 | 80 | 62 | 42 | <0.001 | 54 | 64 | 64 | 0.383 | 55 | 63 | 0.316 | 76 | 55 | 47 | 0.005 |

| t3 | 30 | 27 | 0.508 | 40 | 30 | 19 | 0.016 | 30 | 30 | 25 | 0.747 | 27 | 30 | 0.512 | 32 | 26 | 22 | 0.293 |

| t4 | 19 | 14 | 0.273 | 17 | 24 | 9 | 0.016 | 17 | 19 | 14 | 0.734 | 15 | 18 | 0.529 | 22 | 12 | 15 | 0.285 |

| t5 | 18 | 14 | 0.458 | 18 | 21 | 10 | 0.212 | 13 | 17 | 22 | 0.401 | 15 | 18 | 0.595 | 26 | 8 | 14 | 0.035 |

| Unemployment benefits | ||||||||||||||||||

| t-5 | 57 | 80 | 0.003 | 78 | 75 | 48 | 0.002 | 61 | 73 | 63 | 0.338 | 73 | 61 | 0.093 | 60 | 75 | 65 | 0.343 |

| t-4 | 52 | 70 | 0.019 | 62 | 70 | 45 | 0.009 | 60 | 62 | 52 | 0.503 | 69 | 51 | 0.014 | 60 | 68 | 53 | 0.226 |

| t-3 | 49 | 64 | 0.036 | 51 | 70 | 41 | 0.002 | 55 | 56 | 51 | 0.846 | 72 | 42 | <0.001 | 57 | 64 | 48 | 0.206 |

| t-2 | 38 | 49 | 0.085 | 36 | 54 | 32 | 0.005 | 45 | 40 | 39 | 0.694 | 54 | 33 | 0.001 | 44 | 46 | 39 | 0.559 |

| t-1 | 28 | 26 | 0.603 | 24 | 34 | 22 | 0.067 | 30 | 24 | 26 | 0.539 | 29 | 26 | 0.453 | 35 | 21 | 26 | 0.113 |

| t0 | 16 | 16 | 0.982 | 12 | 19 | 15 | 0.361 | 18 | 13 | 16 | 0.533 | 14 | 17 | 0.495 | 20 | 13 | 14 | 0.321 |

| t1 | 20 | 18 | 0.608 | 23 | 22 | 15 | 0.237 | 21 | 16 | 22 | 0.499 | 13 | 24 | 0.007 | 24 | 17 | 17 | 0.342 |

| t2 | 18 | 24 | 0.167 | 23 | 28 | 11 | 0.004 | 20 | 18 | 24 | 0.584 | 15 | 24 | 0.046 | 25 | 15 | 21 | 0.283 |

| t3 | 17 | 27 | 0.049 | 25 | 31 | 6 | <0.001 | 15 | 24 | 24 | 0.213 | 19 | 21 | 0.726 | 24 | 20 | 18 | 0.578 |

| t4 | 20 | 22 | 0.731 | 29 | 24 | 10 | 0.018 | 13 | 24 | 28 | 0.069 | 15 | 25 | 0.078 | 29 | 22 | 14 | 0.074 |

| t5 | 21 | 15 | 0.282 | 27 | 24 | 6 | 0.008 | 12 | 27 | 18 | 0.074 | 12 | 24 | 0.049 | 35 | 13 | 10 | 0.001 |

Notes: The average per person per year, 5–1 years (Y) before (t-5 to t-1) multidisciplinary medical assessment (MMA), during (t0) and after MMA (t1 to t5), related to sex (W, women; M, men), age at MMA (<39 = 21–39, <49 = 40–49, <63 = 50–63), education (E, elementary; H, high school; U, university), country of birth (O, other than Sweden; SW, Sweden), diagnosis (S, somatic; P, psychiatric; SP, somatic and psychiatric); no diagnosis was assessed in 25 individuals. ANOVA, P-value. F-values, and df were computed but are not presented in the table. P-values in bold type indicate significant results.

Table 1.

Distribution of women and men by age, education, country of birth, and type of diagnosis at MMA (n = 1002)

| n | Men n = 370 % | Women n = 632 % | Total n = 1002 % | PChi2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.056 (ns) | ||||

| 21–39 | 261 | 22 | 29 | 26 | |

| 40–49 | 381 | 39 | 38 | 38 | |

| 50–63 | 360 | 39 | 34 | 36 | |

| Education | 0.079 (ns) | ||||

| Elementary | 406 | 44 | 38 | 41 | |

| High school | 352 | 31 | 38 | 35 | |

| University | 244 | 25 | 24 | 24 | |

| Country of birth | 0.153 (ns) | ||||

| Sweden | 573 | 54 | 59 | 57 | |

| Other than Sweden | 428 | 46 | 41 | 43 | |

| Diagnosis | 0.004* | ||||

| Somatic | 266 | 22 | 29 | 27 | |

| Psychiatric | 244 | 29 | 22 | 24 | |

| Somatic + Psych | 467 | 47 | 47 | 47 | |

| Nonea | 25 | 3 | 2 | 3 |

Notes:

No diagnosis was assessed in 25 cases and no P-value was computed;

Indicates significant results.

Abbreviations: MMA, multidisciplinary medical assessment; ns, not significant.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm, Sweden (1995-149, 2006/1281-31, 2008/71-31/5, 2008/1051-31/12, and 2010/448-32).

Results

Table 1 shows the distribution of women and men in the study population with respect to age, educational level, country of birth, and diagnostic category. All persons had been long-term sickness absent, all for at least one year.31 There was a significant difference between the type of diagnosis with respect to sex. However, there were no significant differences between the sexes with respect to age, education, or country of birth. Table 1 further shows that most persons had both a psychiatric and a somatic diagnosis.

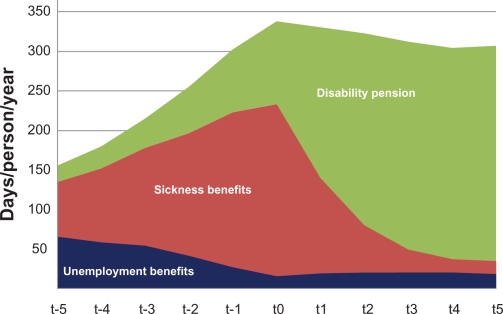

Figure 2 shows the results of a cumulative description of how the average number of days on different kinds of social security benefits had developed during the period of eleven years. Five years before the MMA, about 208 days in a year were not compensated through SA, DP, or unemployment benefits. Five years after the MMA, the group had on average only 64 days without compensation. The average number of days on unemployment benefits decreased from 66 to 16 days per person and year until the time of the MAA, but after the MMA there was no change. The number of days on sickness benefits increased until the time of MMA from 69 to 218 days on average. After the MMA there was a rapid decrease in the number of days on sickness benefits, from 218 to 16 days on average. Before the MMA, the average number of days on DP was 21. Only one individual had a permanent DP before the MMA, but a few individuals had different forms of temporary DP. The average number of days on DP increased gradually after the MMA, from an average of 104 days in the first year, to an average of 272 days five years after the MMA. There is a general shift from high numbers of days on sickness compensation in the years before the MMA, to high numbers of days on DP after the MMA. Five years after the MMA, about 20% had returned to work. Fewer elderly persons, persons not born in Sweden, and persons with both somatic and psychiatric diagnoses returned to work compared to other groups.

Figure 2.

Number of benefit days based on the average value per person and year on unemployment benefit, sickness benefit, disability pension, 5 to 1 years before multidisciplinary medical assessment (MMA) (t-5 to t-1), and after MMA (t1 to t5) for individuals diagnosed in the period 1998–2007.

Table 2 presents the differences in average number of days on the three different types of social security benefits, with respect to sex, age, educational level, country of birth, and type of diagnosis over time. There were no significant differences between the sexes in relation to average days on sickness benefits, disability benefits, or unemployment benefits, neither before nor after the MMA. Age differences in the number of compensated days occurred more frequently, and were particularly pronounced for disability days after the MMA. A tendency towards fewer days on unemployment benefits before and after the MMA was also observed in the oldest age group (50–63 years). There were no significant differences between different levels of education and sickness benefit or unemployment benefits. However, it emerges from the data that individuals with a low level of education had significantly lower numbers of days on DP during the years after the MMA.

Table 2 also shows that there were no clear associations between the country of birth and sickness benefit, but individuals from countries other than Sweden had a significantly higher rate of number of days with DP after the MMA. Further, there were no significant differences between types of diagnosis in relation to average days on DP before the MMA, but there were significant differences between types of diagnosis after the MMA. There were no clear patterns in relation to sickness benefit before or after the MMA. As expected, individuals who had psychiatric diagnoses, as well as individuals with a combination of psychiatric and somatic diagnoses, also had on average a larger number of days on DP after the MMA.

Discussion

The study describes how the use of different kinds of social security benefits developed five years before and five years after MMA. The results show that the average number of days on DP increased rapidly after the MMA, and that the number of days on sickness benefits decreased concurrently. The average number of days on unemployment benefits decreased until the MMA, but remained constant after the MMA.

The results indicate that a referral of the SIO to an MMA did not improve the chances of RTW for large numbers of individuals. Furthermore, the results of this study illustrate that the selection between different forms of social security compensation that takes place after an MMA, and the degree to which it takes place, is partly due to background factors such as age, education, and country of birth, but also related to diagnosis. Age and country of birth are strongly associated with a higher number of days on disability benefits as older individuals and individuals born outside Sweden had a significantly higher number of benefits after MMA. Persons with psychiatric diagnoses as well as those with combinations of somatic and psychiatric diagnoses had a higher average number of days on DP. This may imply that modern working life is less adjustable to psychiatric disorders such as cognitive malfunctioning, phobias, anxieties, or unstable moods compared to somatic disabilities.34,35 To some degree these psychiatric disorders may also have workplace-related grounds.36–39

The results of this study confirm the findings of two previous Swedish studies of transition from SA to DP.14,15 This is also in line with a Danish follow-up of long-term sick-listed individuals,25 and is also in concordance with a recent review of factors affecting the risk of DP.27 However, the fact that conducting an MMA does reduce the numbers who were granted DP and stability in the distribution of factors affecting such as a decision has not previously been studied.

It should be noted, however, that the present study is not a controlled clinical trial. Generally, a high proportion of individuals who have been long-term sickness absent stand a high risk for DP. Conducting MMA earlier during a sick-leave spell might lead to more adequate interventions, promoting RTW.

Methodological considerations

The strength of this study was its longitudinal design, and that the MMAs were carried out in the same manner for all persons. There was also good quality of register data over 16 years (1993–2008) and few missing cases over these years. However, the study has some limitations: with regard to referral of individuals from the SIO, the selection process might have changed over the years (1998–2007), or might differ between SIO officials, and the criteria for SIO selection are unknown.31 Some variables that can impact on the selection process are probably health status, education, economic and labor market situation of the individual, and changes in the insurance system. Not all of the individuals included in this study (n = 1002) could be followed up for a full 5-year period. A total of 39% were lost to follow-up in the fifth year due to a short follow-up period (36%), due to death (2%), or emigration (1%).

Conclusion

The study shows that after a multidisciplinary medical assessment, there was a rapid increase in DP and a corresponding dramatic decrease in sickness benefits. The fact that the multidisciplinary medical assessment was conducted at a late stage of the process of sickness absence seems to lead to a decision to grant DP in a large number of cases. This may be connected with a number of factors such as deterioration of health, labor market difficulties, or lack of efficient vocational rehabilitation. Those factors need to be further researched.

Acknowledgments

This study was financially supported by the County Council of Stockholm and the Swedish Council for Working Life and Social Research.

Footnotes

Disclosure

No conflicts of interest were declared in relation to this paper.

References

- 1.Ilmarinen JE. Aging workers. Occup Environ Med. 2001;58(8):546–552. doi: 10.1136/oem.58.8.546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.OECD Sickness, disability and work, breaking the barriers, Sweden: will the recent reforms make it? 2009. Directive for employment, labor and social affairs, organization for economic co-operation and development. OECD;

- 3.Lidwall U. Long-term sickness absence Aspects of society, work, and family. 2010. PhD thesis, Stockholm: Karolinska Institutet, Sweden; [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Hansen A, Edlund C, Branholm IB. Significant resources needed for return to work after sick leave. Work. 2005;25(3):231–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lidwall U, Marklund S. Trends in long-term sickness absence in Sweden 1992–2008: the role of economic conditions, legislation, demography, work environment, and alcohol consumption. Int J Soc Welfare. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2397.2010.00744.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karlsson NE, Carstensen JM, Gjesdal S, Alexanderson KA. Risk factors for disability pension in a population-based cohort of men and women on long-term sick leave in Sweden. Eur J Public Health. 2008;18(3):224–231. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckm128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krokstad S, Johnsen R, Westin S. Social determinants of disability pension: a 10-year follow-up of 62000 people in a Norwegian county population. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31(6):1183–1191. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.6.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adams H, Ellis T, Stanish WD, Sullivan MJ. Psychosocial factors related to return to work following rehabilitation of whiplash injuries. J Occup Rehabil. 2007;17(2):305–315. doi: 10.1007/s10926-007-9082-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waddell G, Sawney P. Back pain, incapacity for work, and social security benefits: an international review and analysis. Press RSoM; London, United Kingdom: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahlgren A, Bergroth A, Ekholm J, Schuldt K. Work resumption after vocational rehabilitation: a follow-up two years after completed rehabilitation. Work. 2007;28(4):343–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahlgren A, Broman L, Bergroth A, Ekholm J. Disability pension despite vocational rehabilitation? A study from six social insurance offices of a county. Int J Rehabil Res. 2005;28(1):33–42. doi: 10.1097/00004356-200503000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eden L, Andersson IH, Ejlertsson, et al. Return to work still possible after several years as a disability pensioner due to musculoskeletal disorders: a population-based study after new legislation in Sweden permitting “resting disability pension”. Work. 2006;26(2):147–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burstrom B, Nylen L, Clayton S, Whitehead M. How equitable is vocational rehabilitation in Sweden? A review of evidence on the implementation of a national policy framework. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33(6):453–466. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2010.493596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andren D. Long-term absenteeism due to sickness in Sweden. How long does it take and what happens after? Eur J Health Econ. 2007;8(1):41–50. doi: 10.1007/s10198-006-0005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andren D. First exits from the Swedish labor market due to disability. Popul Res Policy Rev. 2008;27:227–238. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wallman T, Wedel H, Palmer E, et al. Sick-leave track record and other potential predictors of a disability pension. A population based study of 8,218 men and women followed for 16 years. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:104. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vaez M, Rylander G, Nygren A, Asberg M, Alexanderson K. Sickness absence and disability pension in a cohort of employees initially on long-term sick leave due to psychiatric disorders in Sweden. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2007;42(5):381–388. doi: 10.1007/s00127-007-0189-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lindberg P, Vingard E, Josephson M, Alfredsson L. Retaining the ability to work-associated factors at work. Eur J Public Health. 2006;16(5):470–475. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cki190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hansen A, Edlund C, Henningsson M. Factors relevant to a return to work: a multivariate approach. Work. 2006;26(2):179–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gjesdal S, Ringdal PR, Haug K, Maeland JG. Predictors of disability pension in long-term sickness absence: results from a population-based and prospective study in Norway 1994–1999. Eur J Public Health. 2004;14(4):398–405. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/14.4.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kivimaki M, Ferrie JE, Hagberg J, et al. Diagnosis-specific sick leave as a risk marker for disability pension in a Swedish population. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61(10):915–920. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.055426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mansson NO, Merlo J. The relation between self-rated health, socioeconomic status, body mass index and disability pension among middle-aged men. Eur J Epidemiol. 2001;17(1):65–69. doi: 10.1023/a:1010906402079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Melchior M, Niedhammer I, Berkman LF, Goldberg M. Do psychosocial work factors and social relations exert independent effects on sickness absence? A six year prospective study of the GAZEL cohort. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57(4):285–293. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.4.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sjogren-Ronka T, Ojanen MT, Leskinen EK, Tmustalampi S, Malkia EA. Physical and psychosocial prerequisites of functioning in relation to work ability and general subjective well-being among office workers. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2002;28(3):184–190. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stoltenberg CD, Skov PG. Determinants of return to work after long-term sickness absence in six Danish municipalities. Scand J Public Health. 2010;38(3):299–308. doi: 10.1177/1403494809357095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Virtanen M, Kivimaki M, Vahtera, et al. Sickness absence as a risk factor for job termination, unemployment, and disability pension among temporary and permanent employees. Occup Environ Med. 2006;63(3):212–217. doi: 10.1136/oem.2005.020297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bjorngaard JH, Krokstad S, Johnsen, et al. Epidemiologisk forkning om uförepensjon i Norden. Norsk Epidemiologi. 2009;19:103–114. [Epidemiological research about disability pension in the Nordic countries, in Norwegian, abstract in English]. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Skogman Thoursie P, Lidwall P, Marklund S. Trends in new disability pensions. In: Gustafsson R, Lundberg I, editors. Worklife and health in Sweden 2004. Stockholm, Sweden: National Institute for Working Life; 2005. pp. 205–222. [Google Scholar]

- 29.SFS 1962:381 . Lagen om allmän försäkring (AFL) Stockholm, Sweden: 1962. [The National Insurance Act, Government Offices of Sweden, in Swedish]. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahlgren A, Bergroth A, Ekholm J. Work resumption or not after rehabilitation? A descriptive study from six social insurance offices. Int J Rehabil Res. 2004;27(3):171–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Svedberg P, Salmi P, Hagberg J, Lundh G, Linder J, Alexanderson K. Does multidisciplinary assessment of long-term sickness absentees result in modification of sick-listing diagnoses? Scand J Public Health. 2010;38(6):657–663. doi: 10.1177/1403494810373674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salmi P, Svedberg P, Hagberg J, Lundh G, Linder J, Alexanderson K. Multidisciplinary investigations recognize high prevalence of co-morbidity of psychiatric and somatic diagnoses in long-term sickness absentees. Scand J Public Health. 2009;37(1):35–42. doi: 10.1177/1403494808095954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salmi P, Svedberg P, Hagberg J, Lundh G, Linder J, Alexanderson K. Outcome of multidisciplinary investigations of long-term sickness absentees. Disabil Rehabil. 2009;31(2):131–137. doi: 10.1080/09638280701855545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muschalla B, Linden M, Olbrich D. The relationship between job-anxiety and trait-anxiety–a differential diagnostic investigation with the Job-Anxiety-Scale and the State-Trait-Anxiety-Inventory. J Anxiety Disord. 2010;24(3):366–371. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Linden M, Muschalla B. Anxiety disorders and workplace-related anxieties. J Anxiety Disord. 2007;21(3):467–474. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hensing G, Andersson L, Brage S. Increase in sickness absence with psychiatric diagnosis in Norway: a general population-based epidemiologic study of age, gender and regional distribution. BMC Med. 2006;4:19. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-4-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gjesdal S, Ringdal PR, Haug K, Maeland JG. Long-term sickness absence and disability pension with psychiatric diagnoses: a population-based cohort study. Nord J Psychiatry. 2008;62(4):294–301. doi: 10.1080/08039480801984024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Linder J, Ekholm KS, Jansen GB, Lundh G, Ekholm J. Long-term sick leavers with difficulty in resuming work: comparisons between psychiatric-somatic comorbidity and monodiagnosis. Int J Rehabil Res. 2009;32(1):20–35. doi: 10.1097/MRR.0b013e328306351d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Andersson L, Nyman CS, Spak F, Hensing G. High incidence of disability pension with a psychiatric diagnosis in western Sweden. A population-based study from 1980 to 1998. Work. 2006;26(4):343–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]