Abstract

Cell-penetrating peptides comprising cloned epitopes that contribute to membrane transduction, DNA-binding and cell targeting functions are known to facilitate nucleic acid delivery. Using the ITASSER software, we predicted the 3-D structure of a well characterized and efficient transfecting cell-penetrating peptide, namely TAT-Mu and its derivative TAT-Mu-AF protein that harbors a targeting ligand, the HER2-binding affibody. Our model predicts TAT-Mu-AF fusion protein as primarily comprising α-helices. The affibody in TAT-Mu-AF is predicted as a 3-helical domain that is distinct from the TAT-Mu domain. Its positioning in three-dimensional structure is oriented in a manner that possibly favors interactions with receptor and facilitates transport to the target site. The linker region between TAT-Mu and the affibody is also predicted as a helix that is likely to stabilize the overall fold of the TAT-Mu-AF complex. Further, the evaluation of secondary structure of the designed TAT-Mu-AF fusion protein by circular dichroism is in support of our predictions.

Keywords: 3-D modelling, iTASSER, CPPs, Affibody, TAT fusions, Nucleic acid delivery, Cell-targeting

Introduction

Efficient gene delivery into mammalian cells has been a challenge ever since it was considered a viable alternative to treat genetic diseases and inherited disorders. The translocating property of transcription factor Antennapedia (Antp) (Perez et al. 1992), herpes simplex virus type 1(HSV-1) VP22 structural protein (Dilber et al. 1999) and the protein transduction domain (PTD) of HIV-1 (TAT) (Fawell et al. 1994) are some of the early examples of cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) that mediate the delivery of proteins and nucleic acids of therapeutic potential. In the last decade, CPPs in gene delivery protocols have gained attention due to their versatility, non-toxicity and ability to deliver nucleic acids into cells (Abes et al. 2007; Lundberg et al. 2007; Vives 2005). TAT CPP that encompasses a basic region of 11 amino acids of HIV-1 TAT has been demonstrated to deliver protein cargo across the blood–brain barrier (Schwarze et al. 1999) and has wide application in the area of gene delivery (Vives et al. 1997; Eguchi et al. 2001; Torchilin et al. 2003; Ishihara et al. 2009). Miller’s laboratory has shed light on the DNA-condensing ability of synthetic adenoviral Mu peptide (Murray et al. 2001) for nucleic acid delivery. Synthetic TAT peptide and more recently, a designed recombinant TAT fusion peptide TAT-Mu (TM), were demonstrated for efficient DNA delivery in the presence of cationic lipids (Hyndman et al. 2004; Rajagopalan et al. 2007; Xavier et al. 2009). The current advancements and applications of TAT and other CPP macromolecules in therapeutic delivery of DNA and siRNA in vitro and in vivo have been reviewed (Gump and Dowdy 2007; Eguchi and Dowdy 2009). From these studies, it is evident that a combinatorial approach is more efficient to deliver therapeutic nucleic acids into cells.

Peptides with targeting ligands have been widely used in formulations that facilitate specific DNA delivery into MDA-MB-453 cells overexpressing the HER2 receptor (Medina-Kauwe et al. 2001; Jeyarajan et al. 2010), an ideal model for DNA targeting. A novel class of small affinity ligands first described a decade ago, i.e. the affibody, was developed towards multiple targets that includes specificity for the extracellular domain of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2/neu) (Orlova et al. 2007). It was also demonstrated that the affibody binds ErbB2 receptors overexpressed in MDA-MB-453/MCF-7/SK-BR-3 cells, through its recognition epitope comprising a 3-helix bundle domain (Nygren 2008). The lack of cell specificity of CPPs motivated the addition of targeting moieties to generate additional functional epitopes and thereby engineer TM with a cell-targeting ligand namely the affibody (AF). However, a major concern preceding such effort is to ensure that the cloned affibody would specifically recognize its target. This would require the designed protein to fold appropriately. Therefore computational studies prior to experimentation of the designed peptides are useful to infer whether the designed protein is capable of maintaining a fold that favors the delivery of therapeutic nucleic acids.

Predicting 3-dimensional structures from amino acid sequences of designed peptides synthesized or overproduced de novo is important to understand the structure–function relationship of biological macromolecules. In the absence of experimentally derived structures from the Protein Data Bank (PDB), the 3-D structures of peptides can be predicted using ab initio methods such as I-TASSER (Wu et al. 2007). Also, CD spectroscopy studies can be carried out to validate the secondary structure. Simulation studies by Zhang’s laboratory demonstrate that I-TASSER can predict correct folds with high reproducibility for small single-domain proteins. The other programs available are ROSETTA (Simons et al. 1997) and TOUCHSTONE II (Zhang et al. 2003). The average performance of I-TASSER is considered to be similar or better with a lower computational time (Wu et al. 2007).

In this study, we investigated the structure of TM and chimeric fusion protein TAT-Mu-AF (TMAF) using the I-TASSER structure-prediction program. The TAT and Mu epitopes of the TM peptide are both necessary for DNA binding and cell uptake (Rajagopalan et al. 2007), while the purpose of the AF epitope, a targeting ligand is to confer specific recognition of the HER2 receptors overexpressed in certain breast carcinoma cells, namely MDA-MB-453. We report here the modelled structure of the chimeric protein TMAF and the evaluation of its secondary structure by CD spectroscopy.

Methods

Peptide/protein design

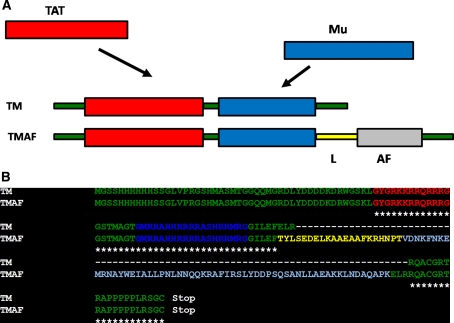

The schematic shown in Fig. 1a depicts the organization of the designed peptide TM and TMAF. The corresponding sequence alignment shown in Fig. 1b was generated using ClustalW program (Thompson et al. 1994). The TM chimera has an N-terminal His-tag region followed by 11 amino acid TAT epitope and 19 amino acid Mu epitope. In TMAF, the AF epitope is engineered downstream of the TAT and Mu epitopes with a linker (L) that separates the AF domain from TM. The linker sequences were derived as reported (Ma et al. 2004) and engineered in silico in pET28a plasmid expression vector (Novagen), in a manner that enables the separation of AF from the TM epitopes. The targeting ligand, a small peptide of ~6 kDa, a non-cysteine three-helix bundle domain (Nygren 2008) has earlier been used for a variety of applications such as in vivo tumor imaging, therapy, diagnostics, bioseparation (Wahlberg et al. 2003; Wikman et al. 2004). We expect the AF to maintain its native fold when fused to TM and hence have the capacity to recognize and bind HER2/3 receptors. The affibody, a HER2-binding peptide sequence (Canine et al. 2009) was cloned along with the TM and linker sequences as shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

a Schematic representation of designed TMAF with cell-targeting ligand (AF) with the vector backbone depicted as thin rectangles. The linker domain depicted in L separates the TAT and Mu domains from the AF domain (Not drawn to scale). b. Pairwise alignment of the amino acid sequences of TM and TMAF using ClustalW program (Thompson et al. 1994). Both TM and TMAF are N-terminal His-tag chimeras followed by a 11-amino acid TAT epitope (YGRKKRRQRRR), 19-amino acid Mu epitope (MRRAHHRRRRASHRRMRG), linker region (TYLSE....NPT) and AF (VDNK......QAPK) followed by the Stop signal. The vector sequences are depicted in thin. Asterisk below the sequence represents identical domains of the designed constructs

TMAF fusion protein construction, design and purification

TMAF as shown in Fig. 1 was designed and cloned in the expression vector pET28a (Novagen) as an N-terminal His-tag fusion protein. The 261 bp long minigene encoding the linker and affibody region was custom synthesized as one fragment and cloned in pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega) at Bioserve Technologies Ltd., Hyderabad, India. The cloned synthetic gene thus obtained was amplified with EcoRI and SacI sites incorporated in designed forward and reverse primers in order to facilitate cloning in-frame with the TAT-Mu epitopes in plasmid pTAT-Mu to generate pTMAF. Plasmid pTMAF was verified to confirm its sequence. The sequence encodes the peptide chimera of 192 amino acids of theoretical molecular mass 21,947 daltons. Plasmid pTMAF was transformed, grown and expressed in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3)pLysS and was subsequently purified under native conditions as described (The QIAexpressionistTM manual, Qiagen) using Ni–NTA column prior to CD measurements.

CD spectroscopy

A far-UV CD spectrum (195–250 nm) of purified TMAF (0.8 mg/ml final concentration) in phosphate buffered saline (pH 7.4) was recorded at room temperature using a Jasco J-815 spectropolarimeter (Jasco, Easton, MD). The spectra shown are the average of five scans that was corrected for the buffer baseline and plotted using Origin 7 software (OriginLab Corp.)

I-TASSER

I-TASSER is a protein structure prediction server based on iterative algorithm for de novo modelling (Wu et al. 2007; Zhang 2007, 2008; Wu et al. 2007; Zhang and Skolnick 2004). We used this program to model the structure of recombinant TM and TMAF corresponding to the amino acid sequences shown in Fig. 1b. I-TASSER is a hierarchical protein structure modelling approach based on the secondary-structure enhanced Profile-Profile threading Alignment (PPA) and the iterative implementation of the Threading ASSEmbly Refinement (TASSER) program (Wu et al. 2007; Zhang 2008). The program retrieves template proteins of similar folds from the PDB library. In case no similar structures are detected, I-TASSER builds whole structures ab initio.

Results and discussion

3-D structure prediction of TMAF by iterative TASSER simulations

TM peptide is characterized by its ability to bind DNA and transfect cells in vitro (Rajagopalan et al. 2007). Structures of TM earlier elucidated by atomic force microscopy depicted the formation of stable nanoparticles (Xavier et al. 2009). The modelled structure of synthetic α-helical TAT peptide alone has also been previously reported to adopt helical conformation (Ho et al. 2001). As suitable templates were not available for the designed TM or TMAF, I-TASSER generated ab initio models and 5 models were reported for the sequence. Our results indicate that the TAT and Mu cationic domains in TM with abundant arginine residues are in α-helical conformation.

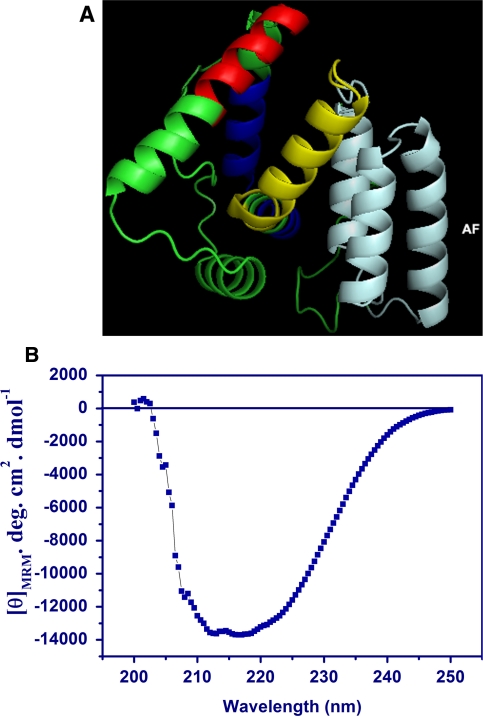

The tertiary structure of TMAF fusion protein with the AF domain engineered in TM for cell-specific DNA targeting was to ascertain if the targeting ligand, namely the HER2-binding affibody maintained the 3-bundle helical fold as in the NMR structure (Wahlberg et al. 2003). The TMAF model (model 1 in the ensemble) is shown in Fig. 2a using PYMOL software (DeLano 2002). The other models were of lower rank and therefore not considered for further analysis. The TMAF model is predicted to comprise primarily helices. The targeting ligand is a 3-helix bundle. The confidence levels of the models are in the range (−5, 2) that suggests a good model. The model suggests that the AF 3-helical bundle is distinct from the TAT-Mu domain and this may facilitate recognition by HER2 receptors.

Fig. 2.

a Structure of recombinant TMAF protein predicted by I-TASSER program. Models were generated using PyMOL software (DeLano 2002). TAT epitope (red), Mu epitope (blue) and AF (pale cyan). The linker regions (yellow) separate the TAT-Mu domains from the AF. b. CD profile of TMAF protein in the far-UV spectral region (195–250 nm). Mean residue mass ellipticity was obtained using a Jasco J-815 spectropolarimeter (Jasco, MD). Five scans were averaged and the calculated MRE values were plotted as a function of the far-UV-spectrum. The characteristic shape and magnitude of the CD spectral trace is indicative of α-helix conformation

Determination of the secondary structure of TMAF by CD spectroscopy

We also evaluated the secondary structure of TMAF protein by CD spectroscopy. Far-UV CD of TMAF protein in PBS buffer (pH 7.4) purified under native conditions as described in methods was used to determine to determine the secondary structure. CD spectroscopy reveals that the secondary structure is predominantly helical, Fig. 2b. This was supported by calculating the R values i.e. the ratio between the molar ellipticity at 222 nm and 207 nm from the CD spectra obtained for TMAF that was 1.33, supporting an increased α-helical content. R = [θ]222/[θ]207, is a useful parameter for the interpretation of CD spectra (Manning and Woody 1991) where a value of ~1 indicates α-helices.

The structural requirement for TAT-mediated transduction is not known. The amino acids (47–57) of the HIV TAT also denoted as the protein transduction domain (PTD), were shown to mediate the passage of heterologous fusion proteins such as the β-galactosidase, into mammalian cells both in vivo and in vitro (Schwarze et al. 1999). Using information from the in vitro data of cationic peptides (Rajagopalan et al. 2007) together with the modelling studies, we propose that the targeting ligand with the basic epitopes in TMAF possibly retain their α-helical conformation and therefore function for its DNA-binding and receptor-binding property. Further, CD spectra confirmed the helical nature of the designed TMAF fusion protein. This may be an important prerequisite for the uptake of nucleic acids that can be delivered via receptor ligand interactions through the affibody. This study predicts and confirms the structure of TMAF fusion protein. Molecular modelling studies combined with experimental determination as demonstrated here, maybe useful for the rational design of novel molecules of desired function. We are in the process of investigating the cell specificity of TMAF in vitro and in vivo.

Conclusion

This study predicts and confirms the structure of engineered epitopes of a recombinant cell targeting multi-domain fusion protein TMAF that has been designed for the delivery of nucleic acids into the cells. Our study reveals that designed TAT-Mu (TM) and TAT-Mu-AF (TMAF) fusion proteins primarily comprise α-helices. The affibody retains the 3-helix bundle conformation known to be essential for recognizing the HER2 receptors. Such modelling studies may be a useful way to decrease the number of potential biomolecules that can be taken up for experimental validation in gene delivery protocols.

Acknowledgments

VG acknowledges Grant support from the Department of Science and Technology, New Delhi, # SR/SO/BB-046/2007. The authors also acknowledge Drs. N. Madhusudhana Rao and T. Ramakrishna for valuable comments and constructive suggestions. VG specially acknowledges Sivakumar Jeyarajan for providing purified TMAF protein and Virender Kumar for help with the CD measurement.

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Abes S, Moulton H, Turner J, Clair P, Richard JP, Iversen P, Gait MJ, Lebleu B. Peptide-based delivery of nucleic acids: design, mechanism of uptake and applications to splice-correcting oligonucleotides. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2007;35:53–55. doi: 10.1042/BST0350053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canine BF, Wang Y, Hatefi A. Biosynthesis and characterization of a novel genetically engineered polymer for targeted gene transfer to cancer cells. J Control Release. 2009;138:188–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLano WL (2002) The PyMOL molecular graphics system. DeLano Scientific, San Carlos, CA, USA. http://www.pymol.org

- Dilber MS, Phelan A, Aints A, Mohamed AJ, Elliott G, Smith CI, O’Hare P. Intercellular delivery of thymidine kinase prodrug activating enzyme by the herpes simplex virus protein, VP22. Gene Ther. 1999;6(1):12–21. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eguchi A, Dowdy SF. siRNA delivery using peptide transduction domains. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2009;30:341–345. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eguchi A, Akuta T, Okuyama H, Senda T, Yokoi H, Inokuchi H, Fujita S, Hayakawa T, Takeda K, Hasegawa M, Nakanishi M. Protein transduction domain of HIV-1 Tat protein promotes efficient delivery of DNA into mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(28):26204–26210. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010625200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawell S, Seery J, Daikh Y, Moore C, Chen LL, Pepinsky B, Barsoum J. Tat-mediated delivery of heterologous proteins into cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:664–668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.2.664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gump JM, Dowdy SF. TAT transduction: the molecular mechanism and therapeutic prospects. Trends Mol Medicine. 2007;13(10):443–448. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho A, Schwarze SR, Mermelstein SJ, Waksman G, Dowdy SF. Synthetic protein transduction domains: enhanced transduction potential in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res. 2001;61:474–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyndman L, Lemoine JL, Huang L, Porteous JD, Boyd AC, Nan X. HIV-1 TAT protein transduction domain peptide facilitates gene transfer in combination with cationic liposomes. J Control Release. 2004;99:435–444. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara T, Goto M, Kodera K, Kanazawa H, Murakami Y, Mizushima Y, Higaki M. Intracellular delivery of siRNA by cell-penetrating peptides modified with cationic oligopeptides. Drug Deliv. 2009;16(3):153–159. doi: 10.1080/10717540902722774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeyarajan S, Xavier J, Rao NM, Gopal V. Plasmid DNA delivery into MDA MB-453 cells mediated by recombinant Her-NLS fusion protein. Int J of Nanomed. 2010;5:725–733. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S13040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg P, El-Andaloussi S, Sütlü T, Johansson H, Langel Ü. Delivery of short interfering RNA using endosomolytic cell-penetrating peptides. FASEB J. 2007;21:2664–2671. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6502com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma N, Wu SS, Ma YX, Wang X, Zeng J, Tong G, Huang Y, Wang S. Nerve growth factor receptor-mediated gene transfer. Mol Ther. 2004;9:270–281. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning MC, Woody RW. Theoretical CD studies of polypeptide helices: examination of important electronic and geometric factors. Biopolymers. 1991;31:569–586. doi: 10.1002/bip.360310511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina-Kauwe LK, Maguire M, Kasahara N, Kedes L. Nonviral gene delivery to human breast cancer cells by targeted Ad5 penton proteins. Gene Ther. 2001;8:1753–1761. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray KD, Etheridge CJ, Shah SI, Matthews DA, Russell W, Gurling HMD, Miller AD, et al. Enhanced cationic liposome-mediated transfection using the DNA-binding peptide Mu (mu) from the adenovirus core. Gene Ther. 2001;8:453–460. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nygren P-Å (2008) Alternative binding proteins: affibody binding proteins developed from a small three-helix bundle scaffold. FEBS J 275:2668–2676 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Orlova A, Tolmachev V, Pehrson R, Lindborg M, Tran T, Sandstrom M, Nilsson FY, Wennborg A, Abrahmsen L, Feldwisch J. Synthetic affibody molecules: a novel class of affinity ligands for molecular imaging of HER2-expressing malignant tumors. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2178–2186. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez F, Joliot A, Bloch-Gallego E, Zahraoui A, Triller A, Prochiantz A. Antennapedia homeobox as a signal for the cellular internalization and nuclear addressing of a small exogenous peptide. J Cell Sci. 1992;102(4):717–722. doi: 10.1242/jcs.102.4.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopalan R, Xavier J, Rangaraj N, Rao NM, Gopal V. Recombinant fusion proteins TAT-Mu, Mu and Mu-Mu mediate efficient non-viral gene delivery. J Gene Med. 2007;9:275–286. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarze SR, Ho A, Vocero-Akbani A, Dowdy SF. In vivo protein transduction: delivery of a biologically active protein into the mouse. Science. 1999;285:1569–1572. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5433.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons KT, Kooperberg C, Huang E, Baker D. Assembly of protein tertiary structures from fragments with similar local sequences using simulated annealing and Bayesian scoring functions. J Mol Biol. 1997;268:209–225. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.0959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22(22):4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torchilin VP, Levchenko TS, Rammohan R, Volodina N, Papahadjopoulos-Sternberg B, D’Souza GM. Cell transfection in vitro and in vivo with nontoxic TAT peptide-liposome-DNA complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:1972–1977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0435906100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vives E. Present and future of cell-penetrating peptide mediated delivery systems: “Is the Trojan horse too wild to go only to Troy?”. J Control Release. 2005;109:77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vives E, Brodin P, Lebleu B. A truncated HIV-1 Tat protein basic domain rapidly translocates through the plasma membrane and accumulates in the cell nucleus. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:16010–16017. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.25.16010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahlberg E, Lendel C, Helgstrand M, Allard P, Dincbas-Renqvist V, Hedqvist A, Berglund H, Nygren P-Å, Härd T. An affibody in complex with a target protein: Structure and coupled folding . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(6):3185–3190. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0436086100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wikman M, Steffen A-C, Gunneriusson E, Tolmachev V, Adams GP, Carlsson J, Stahl S. Selection and characterization of HER2/neu-binding affibody ligands. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2004;17:455–462. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzh053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S, Skolnick J, Zhang Y. Ab initio modelling of small proteins by iterative TASSER simulations. BMC Biol. 2007;5:17. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-5-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xavier J, Singh S, Dean DA, Rao NM, Gopal V. Designed multi-domain protein as a carrier of nucleic acids into cells. J Control Release. 2009;133:154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.09.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. Template-based modelling and free modelling by ITASSER in CASP7. Proteins. 2007;69(S8):108–117. doi: 10.1002/prot.21702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. I-TASSER server for protein 3D structure prediction. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:40. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Skolnick J. Automated structure prediction of weakly homologous proteins on a genomic scale. Proc Natl Acad Sci (USA) 2004;101:7594–7599. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305695101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Kolinski A, Skolnick J. TOUCHSTONE II: a new approach to ab initio protein structure prediction. Biophysical J. 2003;85:1145–1164. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74551-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]