Abstract

Pyogenic spondylitis can be life-threatening for elderly patients. To discuss the characteristics of the disease in the elderly, medical records of 103 consecutive cases of pyogenic spondylitis were reviewed. Of these, 45 cases were 65 years of age or older, and these 45 cases were enrolled into further study. In this study, the proportion of elderly patients among the total number with pyogenic spondylitis was 43.7%, and this figure has increased with the passing of time as follows: 37.5% (1988–1993), 44.4% (1994–1999), and 55.5% (2000–2005). The microorganisms were isolated in 16 cases: Staphylococcus aureus in 13 cases (including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in nine) and others in three. Twenty-five patients had associated diseases: diabetes in 18 patients and malignant tumors in seven. Thirty patients were treated conservatively, and 15 patients underwent surgery. Twenty-six patients had paralysis. All 15 patients treated surgically, and eight of the 11 patients treated conservatively showed improvement in paralysis. Bone union was achieved in all cases except one. Our results indicate that a good outcome can be expected from conservative treatment in elderly patients as well as the young.

Keywords: Pyogenic spondylitis, Elderly patients, Treatment, Paralysis, Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

Introduction

Pyogenic spondylitis often occurs in people with reduced resistance, so-called compromised hosts. Despite recent developments in chemotherapy, pyogenic spondylitis can be life-threatening for elderly patients, many of who have reduced resistance and various concomitant diseases. In recent years, because of the increasing proportion of elderly people in the population, the occurrence of pyogenic spondylitis among the elderly is no longer a rare phenomenon. Recently reported percentages of elderly patients among total cases of pyogenic spondylitis treated surgically are 42% [3], 46% [5], 39% [11], and 40% [15]. Although details of surgical techniques and their favorable results were well described in these reports, patients who had been treated conservatively were not included. Therefore, the demographics of all elderly patients with pyogenic spondylitis, characteristics of the disease, and the outcome following conservative treatment still remain unclear. Because Japan is the most aging society in the world, with elderly people of 65 years or older constituting more than 20% of its population and given that most advanced countries will likely be faced with the same situation in the near future, it is useful to study the demographics, characteristics, and clinical outcomes of pyogenic spondylitis in the elderly in Japan.

The current study was designed to clarify the following: (1) the demographics, namely the gender and proportion of elderly patients, and how these change overtime, (2) characteristics of the disease: causative organism, associated diseases, type of onset, and affected level, and (3) treatment methods and their outcomes.

Materials and methods

We retrospectively reviewed 103 consecutive patients who underwent treatment in our hospital for pyogenic osteomyelitis of the spine during 1988–2005. Forty-five of these patients were 65 years of age or older, and these cases were the subjects of this study. All patients were followed until death or a minimum of 10 months after admission (average 31 months; range 10–90 months). Medical records of these 45 cases were reviewed for demographics including age and gender, characteristics of the disease, including organism isolated, associated diseases, type of onset (acute, subacute, insidious) [4, 10, 12], and affected level. Treatment methods chosen and their outcomes, including improvement in pain (improved, unchanged, deteriorated) and paralysis [severe motor loss (unable to walk), mild motor loss (able to walk), numbness only, normal] were also analyzed. Achievement of bone union in all patients was evaluated with roentgenograms by the same investigator, who did not participate in the treatment in this series. Bone union was determined by trabecular continuity or bridging callus between vertebral bodies on the antero-posterior view or lateral view, or no detectable motion on the flexion–extension lateral view. The radiographs were examined in random order, and all patients’ names and other identifying marks were obscured.

Results

Forty-five of the 103 patients were 65 years of age or older (43.7%), and this figure has increased with the passing of time as follows: 37.5% (1988–1993), 44.4% (1994–1999), and 55.5% (2000–2005). These 45 patients consisted of 28 males and 17 females, whose age at the time of admission ranged from 65 to 93 years (average 71 years).

The diagnosis of pyogenic spondylitis was based on clinical presentations, hematological examinations (elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and white blood cell count), imaging findings (radiographs, magnetic resonance imaging, and computed tomography), and results of treatment.

The most prevalent bacteria was methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) (9/45 cases), and the incidence of diabetes was particularly high (18/45 cases). The causative microorganism was identified in 16 cases. The microorganism was Staphylococcus aureus in 13 cases (including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in nine), Escherichia coli in two, and Candida in one. The bacteria were detected from samples taken during the operation in four cases, from biopsy samples in six cases, by blood culture in two cases, by sputum culture in two cases and by urine culture in two cases (Table 1). Twenty-five of the patients had associated diseases, diabetes in 18 patients, malignant tumors in seven patients, pyelonephritis in two patients, and renal failure, esophageal rupture and chronic hepatitis in one patient each (Table 2). The onset may be acute, subacute, or insidious [4, 10, 12], and our 45 subjects were composed of 27 acute cases with sudden onset of fever of 38°C or higher (range 38.0–39.5°C, average 38.7°C) and severe pain, 11 subacute cases with fever of less than 38°C (range 37.0–37.8°C, average 37.4°C) and moderate pain followed by a relatively mild course, and seven insidious cases with mild pain and unknown time of onset (Table 3). There were five cervical, eight thoracic, six thoracolumbar, and 26 lumbar lesions. Forty-three patients had single-level disease, and two had multilevel involvement; one of these two had double-level disease, and the other one had two separate levels of disease (Table 4).

Table 1.

Causative microorganisms

| Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) | 13 cases (9) |

| Escherichia coli | 2 |

| Candida | 1 |

MRSA methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

Table 2.

Associated diseases

| Diabetes | 18 cases |

| Malignant tumors | 7 |

| Pyelonephritis | 2 |

| Renal failure | 1 |

| Esophageal rupture | 1 |

| Chronic hepatitis | 1 |

Table 3.

Type of onset

| Acute | 27 cases |

| Subacute | 11 |

| Insidious | 7 |

Table 4.

Level affected

| Cervical | 5 cases |

| Thoracic | 8 |

| Thoracolumbar | 6 |

| Lumbar | 26 |

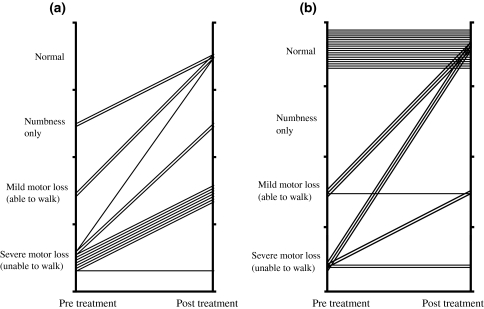

Favorable outcomes from conservative treatment as well as surgical treatment were obtained. Conservative treatment was applied in principle (30 patients), and surgical treatment was performed in patients in whom spinal paralysis occurred and in whom segmental instability persisted and in patients who did not respond to conservative treatment (15 patients). No response to conservative treatment was declared when erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and pain severity did not decrease or stopped decreasing for a few weeks. Conservative treatment consisted of immobilization of the spine by a hard corset and administration of antibiotics. Patients were allowed to stand and walk with a hard corset. Antibiotics were generally administered for 2 or 3 months after the erythrocyte sedimentation rate had normalized. Surgical treatment consisted of radical excision of the lesion followed by anterior fusion with autologous iliac bone graft in 13 patients (also with posterior spinal fusion with instrumentation in three cases) and posterior spinal fusion with instrumentation alone in one patient (Fig. 1). In one patient who had a history of surgery for pancreatic cancer, an anterior approach to the vertebral body was not possible due to strong adhesion of the peritoneum, and therefore posterior decompression was carried out for removal of an epidural abscess causing paralysis. All 45 patients had pain in the neck or back before treatment. The pain improved in 43 of those patients after the completion of antibiotic administration or after surgery. The pain remained unchanged in the other two patients, and there were no cases showing increased pain. Twenty-six of the patients had paralysis before treatment, and 15 of these 26 underwent surgery for treatment of the paralysis. Conservative treatment for the patients with paralysis was performed in 11 cases because of poor general condition or because consent for surgery was not obtained. The paralysis was improved in all of the patients who underwent surgery except one. The paralysis was improved in eight of the 11 patients who received conservative treatment but remained unchanged in the other three. Paralysis did not occur after surgery or conservative therapy in any of the 19 patients who did not have paralysis before treatment (Fig. 2). Two patients died. One of those patients, who refused to receive any medical intervention and stopped eating, died from lack of nutrition at 2 months after admission. The other patient died from pancreatic cancer during the course of treatment for pyogenic osteomyelitis of the spine at 4 months after admission. At the time of the latest follow-up, bony union was observed in 42 of the 43 survivors, and in the other survivor, bony union was not observed at 10 months after surgery although the erythrocyte sedimentation rate had normalized, and the patient reported no pain in his back. In this case, radical excision of the lesion followed by anterior fusion with autologous iliac bone graft had been performed. Instrument had not been used. We could not have longer follow-up than 10 months because the patient moved to another district. Residual kyphosis was observed in patients treated conservatively, but it was not clinically relevant. The mean kyphotic angle in patients treated conservatively was 5.6° (range −2° to 27°) in lumbar lesion and 14.3° (range −8° to 23°) in thoracic lesion.

Fig. 1.

Case 1. A 70-year-old woman developed L1–L2 pyogenic spondylitis. She underwent radical excision of the lesion followed by anterior fusion with autologous iliac bone graft with posterior instrumentation, compression–distraction rod system [7]. Pre-operative antero-posterior (a) and lateral (b) radiographs show destruction of L1–L2 end-plates. Pre-operative magnetic resonance images show low intensity zone in the disk space in T1-weighted image (c) and high intensity zone in T2-weighted image (d). Antero-posterior (e) and lateral (f) radiographs taken 6 months after surgery show fusion of the vertebral bodies

Fig. 2.

Improvement of paralysis in patients treated surgically (a) and conservatively (b)

Discussion

We designed the current study to clarify the demographics of pyogenic spondylitis, particularly the proportion of elderly patients and how this proportion has changed with the passing of time due to the dramatic increase in the elderly population in Japan. Outcomes from conservative treatment for elderly patients with pyogenic spondylitis were also of particular interest to us.

The major limitation of the current study was that due to its retrospective design, improvement in pain and paralysis could only be roughly assessed from medical records.

Large differences in the percentages of elderly patients with pyogenic spondylitis are reported in the English literature: 46% (60 years of age or older) [2], 16.5% (61 years of age or older) [12] and 42% (65 years of age or older) [3]. These differences are thought to be partially due to national variations in the percentage of aged people in the population and also due to the year of study. Previous reports have indicated that the proportions of patients aged 60 years or more among pyogenic spondylitis cases in Japan are: 16% [8], 14% [18], and 47% [13]. In our series, the number of patients aged 60 years or older was 54 (52% of the 103 patients). Thus, the percentage of elderly patients with pyogenic spondylitis in Japan has been increasing year by year and is now about 50% of total cases. This increase is ascribed to the increasing ratio of aged people in the Japanese population. The ratio of aged people (65 years of age or older) in Japan has increased from 9.1% in 1980 to 17.4% in 2000, an increase of almost twofold in the past two decades. The ratio of aged people is expected to further increase to 22.5% in 2010 and to 27.8% in 2020 [14]. It is therefore expected that the incidence of pyogenic spondylitis in elderly people in Japan will continue to increase.

The causative microorganism identified in 16 cases included Staphylococcus aureus in 13 cases, and the bacteria in nine of those 13 was MRSA. Since most cases of MRSA infection occur in hospitals, due consideration should be given to the risk of spondylitis occurring from cross-infection with MRSA in elderly hospitalized patients. Cases of pyogenic spondylitis with MRSA in elderly patients have been increasing recently, as indicated by the occurrence of five such cases among the nine pyogenic spondylitis patients in the past 6 years in our series. It is not surprising that we only identified the causative germ in just 16/45(35.6%) patients. 35.6% is not very low. There are many papers reporting similar ratio: 13.1% [12], 28.6% [1], 51.7% [15], 28.9% [13], and 27.9% [17].

Since many elderly people have reduced immunity accompanying various diseases, they are susceptible to infectious diseases such as pyogenic spondylitis. Twenty-five (56%) of our 45 patients had associated diseases. The incidence of diabetes was particularly high (18/45 cases). Perronne et al. [16] reported that 18% of their patients with pyogenic spondylitis had diabetes and suggested that diabetes is one of the main contributory factors. Attention must be paid to diabetes as a risk factor for pyogenic spondylitis since its incidence is increasing year by year [6].

Eighteen (40%) of the 45 patients aged 65 years or older had subacute or chronic pyogenic spondylitis. Diagnosis is often delayed in such patients because the time of onset is not clear. Particular attention should be paid to elderly people since many elderly people have neck or back pain due to degenerative diseases.

Conservative treatment with immobilization and systemic administration of antibiotics is the first choice of treatment for pyogenic spondylitis. In our series, bony union at the affected site and alleviation of pain were obtained in all patients treated conservatively. Thus, a good outcome from conservative treatment can be expected in elderly patients as well as the young. However, in elderly patients, attention should be paid to the possible occurrence of secondary complications caused by bed rest, such as pneumonia, urinary tract infection, bedsores, and dementia. Selection of an appropriate antibiotic is important for conservative treatment. Antibiotics to which the bacteria are sensitive are naturally the first choice in cases in which the causative bacteria has been identified, but selection of antibiotics for cases in which the causative bacteria has not been identified is difficult. We mainly used second-generation cephalosporin with broad spectrum in our patients, and combination therapy with vancomycin was used in cases in which MRSA was the causative bacteria. Care must be taken when using vancomycin in elderly patients because of diarrhea as a side effect and potential renal dysfunction, and therefore, the serum concentration of vancomycin should be monitored during the period of administration. The optimal duration of antibiotics use remains controversial because no randomized clinical trial comparing short with longer treatment course has been undertaken. However, Asamoto [1] reported that 2 months use of antibiotics after normalization of laboratory data was sufficient, and Kourbeti [9] suggested 6–8 weeks minimum up to 3 months antibiotic treatment.

Previously reported incidence of paralysis in patients with pyogenic spondylitis are relatively low: 5.2% [12], 7.1% [3], 8% [8], 9.5% [18], and 18% [13]. The incidence of paralysis was high in our patients aged 65 years or older (26/45, 58%) but was low in patients of less than 65 years of age (10/58, 17%). Sakate et al. [17] reported that paralysis occurred in 35% of their patients aged 60 years or older but in none of their patients aged less than 60 years. Thus, spondylitis in elderly patients is characterized by a high incidence of paralysis, and this is thought to result from the high incidence of spinal canal stenosis, spinal deformity, and susceptibility to neural tissue damage in elderly people.

Candidates for surgical treatment include patients in whom paralysis has occurred and patients in whom bone destruction or segmental instability has progressed. In our series, the primary indication for surgery was paralysis, not segmental instability. It is thought to be due to high incidence of paralysis in elderly patients described above. Paralysis due to epidural abscess often occurs relatively early before segmental instability progresses.

Surgery cannot be performed in some elderly patients who are candidates for surgical treatment because of poor general condition or because of refusal by the patient or a member of the patient’s family to give consent to surgical treatment. In our series, conservative treatment was performed for 11 of the 26 in whom paralysis occurred. The paralysis was improved by conservative therapy in eight of those 11 patients. The amelioration of paralysis was thought to be due to the disappearance of a preexisting epidural abscess and relief of nerve compression (Fig. 3). We have the impression that the time to expect neurological improvement in patients treated conservatively is 2–8 weeks. However, it is impossible to identify the exact time of beginning of neurological improvement from medical records. This is a limitation of the current study due to retrospective design. Our results indicate that paralysis can be improved even by conservative therapy in patients in whom an abscess is the cause of paralysis.

Fig. 3.

Case 2. A 82-year-old man developed an L4–L5 pyogenic spondylitis. He had severe pain and numbness in his right leg. Pre-treatment T1- (a) and T2 (b) -weighted magnetic resonance images show epidural abscess. He was treated conservatively, including immobilization of the spine by a hard corset and administration of antibiotics, and the pain in his leg disappeared. T1- (c) and T2 (d) -weighted magnetic resonance images taken 3 months later reveal disappearance of epidural abscess

Conflict of interest

No funds were received in support of this work. No benefits in any form have been or will be received from any commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Asamoto S, Doi H, Kobayashi N, et al. Spondylodiscitis: diagnosis and treatment. Surg Neurol. 2005;64:103–108. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2004.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Digby JM, Kersley JB (1979) Pyogenic non-tuberculous spinal infection. J Bone Joint Surg 61-B:47–55 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Dimar JR, Carreon LY, Glassman SD, et al. Treatment of pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis with anterior debridement and fusion followed by delayed posterior spinal fusion. Spine. 2004;29:326–332. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000109410.46538.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guri JP. Pyogenic osteomyelitis of the spine: differential diagnosis through clinical and roentgenographic observations. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1946;28:29–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ha KY, Shin JH, Kim KW, et al. The fate of anterior autogenous bone graft after anterior radical surgery with or without posterior instrumentation in the treatment of pyogenic lumbar spondylodiscitis. Spine. 2007;32:1856–1864. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318108b804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.International Diabetes Federation (2007) Facts & Figures page. http://www.idf.org/home/index.cfm?node=6. Accessed Jan 2007

- 7.Kaneda K, Kazama H, Satoh S, et al. Follow-up study of medial facetectomies and posterolateral fusion with instrumentation in unstable degenerative spondylolisthesis. Clin Orthop. 1986;203:159–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kokubun S, Tsukui T, Sakai K, et al. Pyogenic osteomyelitis of the spine: diagnosis and treatment. Rinsho Seikei Geka. 1978;13:307–316. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kourbeti IS, Tsiodras S, Boumpas DT. Spinal infections: evolving concepts. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2008;20:471–479. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e3282ff5e66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kulowski BJ. Pyogenic osteomyelitis of the soine. J Bone Joint Surg. 1936;18:343–364. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee JS, Suh KT (2006) Posterior lumbar interbody fusion with an autogenous iliac crest bone graft in the treatment of pyogenic spondylodiscitis. J Bone Joint Surg 88-B:765–770 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Malawski SK, Lukawski S. Pyogenic infection of the spine. Clin Orthop. 1991;272:58–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maruo S, Wada G, Taniguchi M, et al. Treatment for pyogenic osteomyelitis of the spine. Seikei Geka. 1987;38:611–620. [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Institute of Population and Social Security Research (2007) Population Projections for Japan: 2001–2050 with Long-range Population Projections. http://www.ipss.go.jp/index-e.html. Accessed Jan 2007

- 15.Pee YH, Park JD, Choi YG, et al. Anterior debridement and fusion followed by posterior pedicle screw fixation in pyogenic spondylodiscitis: autologous iliac bone strut versus cage. J Neurosurg Spine. 2008;8:405–412. doi: 10.3171/SPI/2008/8/5/405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perronne C, Saba J, Behloul Z, et al. Pyogenic and tuberculous spondylodiscitis (vertebral osteomyelitis) in 80 adults patients. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;19:746–750. doi: 10.1093/clinids/19.4.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sakate I, Tamura N, Miyake Y, et al. Treatment for the pyogenic osteomyelitis of the spine in the elderly. Bessatsu Seikei Geka. 1987;12:207–212. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Satomi K, Otani K, Mitsuashi S, et al. Pyogenic osteomyelitis of the spine. Rinsho Seikei Geka. 1980;15:594–600. [Google Scholar]