Abstract

The transoral route is the gold standard for odontoid resection. Results are satisfying though surgery can be challenging for patients and surgeons due to its invasiveness. A less invasive transnasal approach could provide a sufficient extent of resection with less collateral damage. The technique of transnasal endoscopic odontoid resection is demonstrated by a case series of three patients. A fully endoscopic transnasal odontoid resection was conducted by use of CT-based neuronavigation. A complete odontoid resection succeeded in all patients. Symptoms such as dysarthria, swallowing disturbance, salivary retention, myelopathic gait disturbances, neck pain, and tetraparesis improved in all patients markedly. Transnasal endoscopic odontoid resection is a feasible alternative to the transoral technique. It leaves the oropharynx intact, which could result in lower approach related complications especially in patients with bulbar symptoms.

Keywords: Endoscopy, Basilar invagination, Odontoid, Odontoidectomy, Transnasal

Introduction

The transoral—endoscopic or non-endoscopic—approach is the most commonly used approach for the odontoid resection. Today it is still considered to be the gold standard [1, 2]. Others like the extreme lateral-transatlas approach, anterior cervical access, and midfacial translocation are used as well [3–5].

Nevertheless, the indication for removal of the odontoid remains rare nowadays.

Usually pannus formation posterior to the odontoid and atlantoaxial instability in rheumatoid arthritis is adequately treated by posterior spinal decompression and fusion. Thereby the atlantoaxial instability is eliminated and the inflammatory reaction, which causes the pannus formation, usually ceases. In patients with persistent or progressive symptoms and basilar impression, despite posterior fusion and decompression, ventral decompression is indicated as well [1, 6].

Associated with the standard transoral approach are complications like velopharyngeal incompetence, hypernasal speech, swallowing disturbances, and temporomandibular joint syndrome, even though use of endoscopes can improve visualisation and exposure [1, 7]. In patients with bulbar symptoms these approach related complications could add significant comorbidity.

The endoscopic transnasal approach on the other hand seems superior in this respect, because the oropharynx remains completely intact. It has been used for different purposes with very good results [8–10].

The endoscopic transnasal approach for resection of the odontoid process has been introduced recently, though published experience with this approach is still scarce. So far only two case series were published [11, 12].

Patients

The technique and results of transnasal endoscopic odontoid resection are demonstrated by a prospective case series of 3 patients 52-, 64-, and 77-year-old, female (Table 1) who received odontoid resection between November 2007 and March 2009:

Rheumatoid arthritis and basilar impression

Retrodental extradural tumor

Os odontoideum with basilar impression

Table 1.

Patients’ profiles

| Pat. no. | Age/sex | Symptoms | Pathology | CSF leakage | Previous dorsal decompression and stabilisation | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 64/f | Tetraparesis, swallowing disturbances, salivary retention, dysarthria, neck pain | Rheumatoid arthritis | No | Yes | Improved |

| 2 | 77/f | Myelopathic gait disturbance, neck pain, disturbance of fine motor skills | Retrodental tumor | No | Yes | Improved |

| 3 | 52/f | Myelopathic gait disturbance, neck pain, disturbance of fine motor skills, swallowing disturbances, salivary retention, dysarthria | Os odontoideum | No | Yes | Improved |

All patients underwent dorsal fusion (C1–C2, C0–C2(3)) and dorsal decompression before anterior odontoid resection. On admission patients suffered from progressive symptoms like: neck pain and disturbance of fine motor skills (all patients), dysarthria (2 of 3 patients), swallowing difficulties—salivary retention (2 of 3 patients), myelopathic gait disturbances (all patients), and tetraparesis (1 of 3 patients).

Patient 1

A 64-year-old woman suffered from rheumatoid arthritis with basilar impression. She underwent posterior atlantoaxial fusion more than 20 years ago. On admission she displayed a progressive tetraparesis (motor power grade 2/5–3/5) as well as a progression of swallowing disturbances, recurrent pneumonia, and therefore dependency on a nasogastric tube for 3 month (Fig. 1a, b, Table 1).

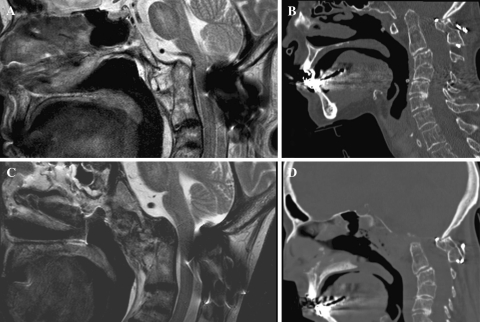

Fig. 1.

a Preoperative MRI reveals basilar impression from a dislocated odontoid. b Cranially migrated odontoid also clearly visible on CT scan. c Postoperative MRI after odontoid resection showing now a decompressed brainstem. d Postoperative CT: caudal tip of the clivus, the odontoid, and part of the C1 arch vanished

Patient 2

A 77-year-old woman with a retrodental extradural tumor received a dorsal decompression C1 for 2 years and fusion of C1–C2 for 2 weeks before odontoid resection due to progressive gait disturbance, progressive hypaesthesia of both hands and feet as well as strong neck pain (Fig. 2a, b).

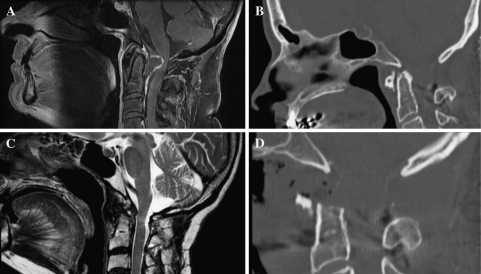

Fig. 2.

a Preoperative MRI shows a retrodental tumor with peripheral contrast agent enhancement and compression of the medulla. b CT showing the odontoid and posterior the site of the dorsal decompression. c Postoperative MRI after transnasal odontoid and tumor resection: the former site of anterior medulla compression has vanished. d Postoperative CT: most of the anterior arch of C1, and the odontoid are drilled away

Patient 3

A 52-year-old woman suffered from basilar impression due to an os odontoideum. The patient received a suboccipitocervical decompression and fusion C0–C1–C2 18 months ago. On admission she presented a progression of gait, fine motor skills, and swallowing disturbance, as well as neck pain. (Fig. 3a, b).

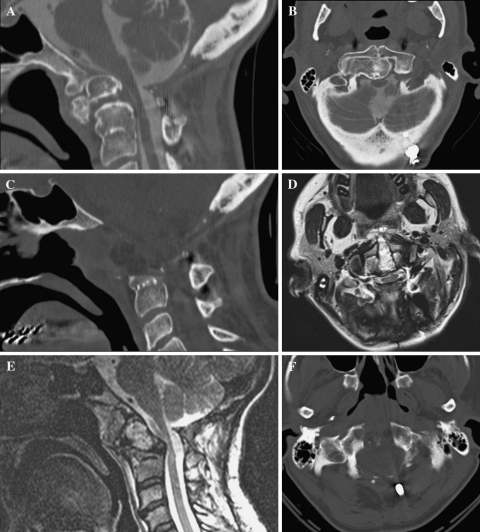

Fig. 3.

a Preoperative Myelography shows an os odontoideum with compression of the brainstem. b CT showing the os odontoideum and bulging of the brainstem. c Postoperative CT after the first operation, which suggests medially a sufficient decompression of the brainstem, the caudal tip of the clivus, the anterior bony structures and the os odontoideum are medially drilled away. d Postoperative axial MRI after first operation, which reveals especially lateral a persistent bulging of the brainstem at the right side. e Postoperative MRI after expanded transnasal decompression, former site of anterior brainstem compression is still visible. f Postoperative CT after expanded transnasal decompression now reveals a sufficient decompression lateral on both sides

Surgical procedure

After transoral, endotracheal intubation the patient is placed in supine position. The head is fixed orthograde in the Mayfield clamp. Midface, forehead and nose are disinfected; sterile dressings leave the midface, forehead and nose free. Surface registration of a CT dataset (slice thickness 1 mm) is carried out (BrainLAB VectorVision2) thereafter. CT dataset surface registration is carried out with a registration-pointer (BrainLAB) analogous to an MRI surface registration. In two patients there was persistent motion at the C0–C1 junction, though insignificant, with regard to the intraoperative navigation since the CT dataset is acquired in orthograde position. In all cases, the four handed technique via two nostrils was used to resect the odontoid process down to the base. Only in the case with the retrodental tumor it was intended to resect soft tissue for further decompression of the medulla. From one case to the other, there was a marked change in the surgical approach. In the first case, following the suggestion of Nayak et al. [11], an extended transnasal approach was created first. A wide sphenoidotomy was performed by resection of the vomer, the posterior edge of the nasal septum, the anterior wall of the sphenoid sinus, and the posterior ethmoid with its respective mucosa. The internal mucosa was resected. Thereafter, the proper approach to the odontoid was created. The bony floor of the sphenoid sinus and the clivus from underneath the sphenoid sinus floor was drilled from midline to the carotid protuberance laterally. Guided by neuronavigation, the tip of the odontoid was found beneath soft tissue. From the tip to the base, the odontoid was thinned by high-speed drill (diamond drill, 4 mm). While drilling to the caudal direction, the anterior arch of the atlas was reached and subsequently drilled, too. Pulsation of the soft tissue was visible as sign for sufficient decompression. In this case, the highspeed drill HiLAN XS with the long angled hand piece GB758R (Aesculap, Tuttlingen, Germany) was used. The length of the drill was just sufficient for drilling of the odontoid base, since in this case the odontoid base is positioned far cranial due to the basilar impression. Most of the preparation was performed under visualisation of a 0° 18 cm endoscope, 4 mm diameter with irrigation shaft. Only the preparation of the odontoid base was done with a 30° endoscope. The distance from the nostril to the odontoid becomes longer the more caudally the resection gets.

In the second case, the localisation of the pathology was, with regard to the hard palate and the clivus, more caudal. The intention was not to perform a wide sphenoidotomy in the first place. Instead, only the lower part of the vomer and the posterior edge of the nasal septum were resected to allow bilateral access to the choanae. Resection of the mucosa of the clivus forming the posterior wall of the epipharynx guided to the bony lower tip of the clivus. In this case only resection of the odontoid, and not the clivus and only subtotal resection of the anterior arch of the atlas, was necessary (Fig. 2). The surgical field was far deeper as in the first case. Therefore, 0° and 30° endoscopes, 30 cm in length were used (Storz, Tuttlingen, Germany). Furthermore, a longer drill, MA-D20, with a thinner shaft, MA-15S, was introduced (Anspach, Palm Beach Gardens, Fl, USA). In both cases, the resection cavity was only covered with fibrin glue. As demonstrated in Fig. 3, the most caudal site of compression of the medulla was found in our third patient. In this case, the sphenoid sinus was not opened at all. Only the posterior lower edge of the nasal septum was resected to gain bilateral access. The most challenging and time-consuming resection in this case was the lateral aspects of the C2 body and the bone of the axis caudal to the anterior arch of the atlas. As shown in Fig. 3d and f, the drilling was done in a keyhole fashion with narrow corridor ventral and wider resection dorsal. In this case, a real cavity was formed. Even in standing position, fluids would not exit this cavity, provoking infection. For that reason, the cavity was obstructed by fascia lata. A nasogastric tube was inserted under endoscopic view.

Results

All patients were extubated the day of surgery. They received a gastric tube for 7 days (one patient for 3 weeks), thereafter, standard oral diet. There were no wound-healing disorders. One patient underwent a laterally and caudally expanded resection 5 days after first surgery due to insufficient relief of symptoms and still visible signs of basilar impression on postoperative imaging (Fig. 3c, d).

All patients displayed improvement of myelopathy, motor function, fine motor skills and reduction of neck pain.

After months of immobilization due to tetraparesis, patient no. 1 made her first attempt at walking during the first week postoperatively. Nasogastric tube was removed on the third postoperative week, speech normalized and salivary retention disappeared. Due to myocardial infarction, the patient died 4 months after the operation. The patient had a long history of chronic heart failure and recurrent endocarditis with valvular transplant 10 years ago.

One year postoperatively patient no. 2 displayed completely restored fine motor skills, as well as no gait disturbances or hypaesthesia. Complete resection of the retrodental extradural tumor was shown in the postoperative imaging (Fig. 2c, d). Histopathology revealed chondral tissue, no inflammation or malignant cells. She only complained about the restricted mobility of her neck.

Patient no. 3 directly showed postoperative persistent symptoms. Due to insufficient decline of symptoms and still visible signs of basilar impression on postoperative imaging (Fig. 3c, d) she underwent a laterally expanded resection 5 days after first surgery. Three months postoperatively swallowing disturbance, dysarthria and salivary retention ceased completely. Gait disturbance had improved significantly. She still complained about occasional neck pain. Imaging of the follow-up examinations revealed persistent and complete resection of space-occupying lesions (Fig. 3e, f).

Discussion

The odontoid process is still one of the most difficult to access areas of the spine. The transoral approach is the usually performed route for resection of the odontoid process [1, 13]. The transnasal approach with standard equipment performed by a purely neurosurgical team experienced in endoscopic surgery or a neurosurgical/otolaryngological team appears as a good alternative [12, 14, 15]. Neuronavigation proved to be an important adjunct. As we learned from Case no. 3, there is no anatomical landmark in the lateral and caudal direction for the extent of resection of the C2 base. Complete resection of the odontoid process was possible even in the case without basilar impression.

Compared to other descriptions of the transnasal approach to the odontoid we do not see the necessity for a wide sphenoidotomy in all patients, depending on the relation of the odontoid to the sphenoid sinus in cranio-caudal axis. Only in cases of severe basilar impression with an odontoid which migrated through the foramen magnum a sphenoidotomy could be necessary. Complications due to soft tissue defects appear to be less likely with the transnasal approach compared to the standard oral approach. Pharyngeal incision and opening of the oral cavity with a higher potential risk of bacterial contamination is not necessary [16]. Velopharyngeal incompetence due to splitting of the soft palate was not observed in our series. It is a complication in the transoral route but was observed less frequently in the transnasal route by Nayak et al. [11] as well.

Therefore in cases of swallowing disturbances and salivary retention we see an advantage in the transnasal approach, which does not add as much extra damage to the oral cavity and oropharyngeal tissue. In our patients no clinical signs of damage or obstruction of the eustachian tube were observed.

Considerable risks of the transnasal approach are cerebrospinal fluid leaks and vascular injury, which resemble the risks of other possible approaches.

Whether these complications may be controlled via the transnasal endoscopic approach, has not been shown yet. Limitations of the transnasal approach are its restriction to medial processes. Caudally the hard palate limits the area of resection to the base of the odontoid. As Messina et al. [17] stated in regard to their cadaver study a complete resection of the odontoid in cases in which the C1–C2 junction is below the horizontal level of the hard palate is challenging.

Conclusion

Though experience with the transnasal approach is limited in our series of three patients, we see more than satisfying results with good improvement of neurological function. During the follow up period we did not observe any surgery-associated complications. The transnasal approach to the odontoid is less invasive than other approaches and therefore could reduce peri- and postoperative patient distress. The oropharynx stays untouched which might be an advantage in patients with bulbar symptoms, especially swallowing disturbances, and could reduce significantly the approach related complications.

Conflict of interest

None.

Footnotes

J. Gempt and J. Lehmberg contributed equally.

Contributor Information

Jens Gempt, Email: Jens.Gempt@lrz.tum.de.

Jens Lehmberg, Phone: +49-89-41402151, FAX: +49-89-41404889.

References

- 1.Crockard HA, Pozo JL, Ransford AO, Stevens JM, Kendall BE, Essigman WK. Transoral decompression and posterior fusion for rheumatoid atlanto-axial subluxation. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1986;68:350–356. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.68B3.3733795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crockard HA, Sen CN. The transoral approach for the management of intradural lesions at the craniovertebral junction: review of 7 cases. Neurosurgery. 1991;28:88–97. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199101000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mello-Filho FV, Mamede RC, Ricz HM, Susin RR, Colli BO. Midfacial translocation, a variation of the approach to the rhinopharynx, clivus and upper odontoid process. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2006;34:400–404. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ture U, Pamir MN. Extreme lateral-transatlas approach for resection of the dens of the axis. J Neurosurg. 2002;96:73–82. doi: 10.3171/spi.2002.96.1.0073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolinsky JP, Sciubba DM, Suk I, Gokaslan ZL. Endoscopic image-guided odontoidectomy for decompression of basilar invagination via a standard anterior cervical approach. Technical note. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;6:184–191. doi: 10.3171/spi.2007.6.2.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eyres KS, Gray DH, Robertson P. Posterior surgical treatment for the rheumatoid cervical spine. Br J Rheumatol. 1998;37:756–759. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/37.7.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Menezes AH, VanGilder JC. Transoral-transpharyngeal approach to the anterior craniocervical junction. Ten-year experience with 72 patients. J Neurosurg. 1988;69:895–903. doi: 10.3171/jns.1988.69.6.0895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alfieri A, Jho HD, Schettino R, Tschabitscher M. Endoscopic endonasal approach to the pterygopalatine fossa: anatomic study. Neurosurgery. 2003;52:374–378. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000044562.73763.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alfieri A, Jho HD, Tschabitscher M. Endoscopic endonasal approach to the ventral cranio-cervical junction: anatomical study. Acta Neurochir. 2002;144:219–225. doi: 10.1007/s007010200029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Divitiis E, Cappabianca P, Cavallo LM. Endoscopic transsphenoidal approach: adaptability of the procedure to different sellar lesions. Neurosurgery. 2002;51:699–705. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200209000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nayak JV, Gardner PA, Vescan AD, Carrau RL, Kassam AB, Snyderman CH. Experience with the expanded endonasal approach for resection of the odontoid process in rheumatoid disease. Am J Rhinol. 2007;21:601–606. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2007.21.3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu JC, Huang WC, Cheng H, Liang ML, Ho CY, Wong TT, Shih YH, Yen YS. Endoscopic transnasal transclival odontoidectomy: a new approach to decompression: technical case report. Neurosurgery. 2008;63:ONSE92–ONSE94. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000313115.51071.D5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Welch WC, Kassam A. Endoscopically assisted transoral-transpharyngeal approach to the craniovertebral junction. Neurosurgery. 2003;52:1511–1512. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000068353.22859.CB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kassam AB, Snyderman C, Gardner P, Carrau R, Spiro R. The expanded endonasal approach: a fully endoscopic transnasal approach and resection of the odontoid process: technical case report. Neurosurgery. 2005;57:E213. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000163687.64774.E4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laufer I, Greenfield JP, Anand VK, Hartl R, Schwartz TH. Endonasal endoscopic resection of the odontoid process in a nonachondroplastic dwarf with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis: feasibility of the approach and utility of the intraoperative Iso-C three-dimensional navigation. Case report. J Neurosurg Spine. 2008;8:376–380. doi: 10.3171/SPI/2008/8/4/376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baird CJ, Conway JE, Sciubba DM, Prevedello DM, Quinones-Hinojosa A, Kassam AB. Radiographic and anatomic basis of endoscopic anterior craniocervical decompression: a comparison of endonasal, transoral, and transcervical approaches. Neurosurgery. 2009;65:158–163. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000345641.97181.ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Messina A, Bruno MC, Decq P, Coste A, Cavallo LM, Divittis E, Cappabianca P, Tschabitscher M. Pure endoscopic endonasal odontoidectomy: anatomical study. Neurosurg Rev. 2007;30:189–194. doi: 10.1007/s10143-007-0084-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]