Abstract

Determining the eligibility of patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) for deep brain stimulation (DBS) can be challenging for general (non-specialised) neurologists. We evaluated the use of an online screening tool (Stimulus) that aims to support appropriate referral to a specialised centre for the further evaluation of DBS. Implementation of the tool took place via an ongoing European multicentre educational programme, currently completed in 15 DBS centres with 208 referring neurologists. Use of the tool in daily practice was monitored via an online data capture programme. Selection decisions of patients referred with the assistance of the Stimulus tool were compared to those of patients outside the screening programme. Three years after the start of the programme, 3,128 patient profiles had been entered. The intention for referral was made for 802 patients and referral intentions were largely in accordance with the tool recommendations. Follow-up at 6 months showed that actual referral took place in only 28%, predominantly due to patients’ reluctance to undergo brain surgery. In patients screened with the tool and referred to a DBS centre, the acceptance rate was 77%, significantly higher than that of the unscreened population (48%). The tool showed a sensitivity of 99% and a specificity of 12% with a positive and negative predictive value of 79 and 75%, respectively. The Stimulus tool is useful in assisting general neurologists to identify appropriate candidates for DBS consideration. The principal reason for not referring potentially eligible patients is their reluctance to undergo brain surgery.

Keywords: Parkinson’s disease, Deep brain stimulation, Appropriateness method, Decision support

Introduction

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is an established therapy for patients with advanced Parkinson’s disease (PD). Several clinical trials have demonstrated significant improvement of motor symptoms, daily ‘off’ time, medication use and quality of life in well-selected patients [1–10]. To determine eligibility for DBS, patients need to undergo a comprehensive assessment in a specialised centre for movement disorders. Partly due to the lack of clear and manageable criteria for pre-selection by referring neurologists, a substantial proportion of patients are rejected following the evaluation in DBS centres [11]. For the same reason, it is also conceivable that many patients who could benefit from DBS therapy are not referred for further evaluation. In order to support appropriate pre-selection, we developed and implemented an online screening tool, called Stimulus, and monitored its use in daily clinical practice. The monitoring project aims at determining the relationship between the tool recommendations and actual referral decisions, as well as the predictive value of the tool outcomes for final selection decisions in specialised DBS centres. Here we present the three-year results of this ongoing project.

Methods

Electronic screening tool

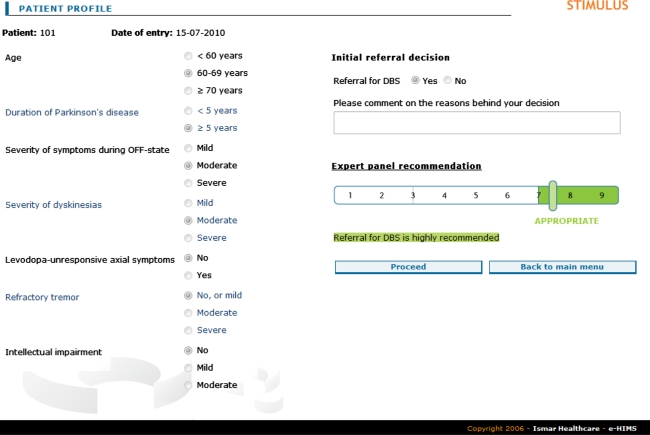

The development of the electronic screening tool is described elsewhere [12]. In summary, a panel of 12 European experts in movement disorders used the RAND Appropriateness Method [13, 14] to assess the appropriateness of referral for DBS for 972 hypothetical patient profiles. These profiles were mutually exclusive combinations of the values of seven clinical variables considered relevant to the decision as to whether a patient should be referred to a specialised centre for the consideration of DBS. Variables included age, disease duration, severity of off-symptoms, dyskinesias and tremor, presence of axial symptoms, and mental status. During a two-round process, panelists individually rated the appropriateness of referral using a nine-point scale. For each of the profiles included, an appropriateness statement (appropriate, inappropriate, or uncertain) was calculated on the basis of the median panel score and the extent of agreement [14]. The panel also formulated five absolute criteria a patient should meet to be considered for further DBS evaluation (diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease, presence of troublesome symptoms despite optimal pharmacological treatment or intolerable side effects of anti-parkinsonian medication, motor improvement with levodopa, absence of medical conditions preventing surgery, and absence of significant medically-resistant mental diseases). Panel results were embedded in an electronic decision tool that allows the user to select a patient profile and to see the related panel recommendation on referral (Fig. 1). The Stimulus tool is available via http://test.stimulus-dbs.org.

Fig. 1.

User interface of the screening tool

Implementation and monitoring

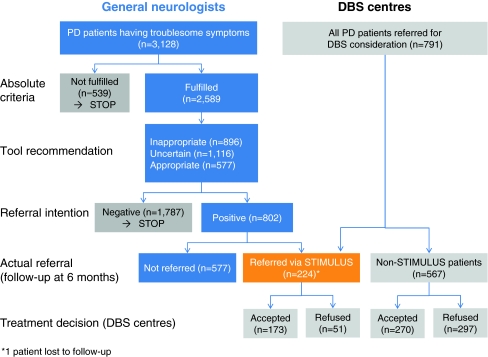

The tool was disseminated via regional educational meetings for general neurologists in six European countries. Meetings were moderated by an expert in movement disorders from the same region, and included an explanation of the development and functionalities of the tool. After the meeting, participants were asked to use the tool consecutively for a period of 4 months in patients having troublesome symptoms from Parkinson’s disease. The tool recommendation was not mandatory for the referral decision. Patient profiles and referral decisions were anonymously entered by participating neurologists in an online database. Six months after initial data entry, they were asked to add follow-up data for all patients for whom a positive referral intention was documented (verification of actual referral; if not referred, reasons behind the decision). For patients referred to a specialised centre for the consideration of DBS treatment, neurologists were asked to attach a printed tool report to the referral letter (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Flow chart of the data collection by general neurologists and by DBS centres

Evaluation

In parallel with the data collection by general neurologists, regional DBS centres were asked to provide monthly reports on final selection decisions (acceptance/refusal, reasons for refusal) for all PD patients evaluated for DBS (Fig. 2). Using the form attached to the referral letter, a distinction could be made between patients referred with and without the use of the Stimulus tool. For patients with a completed screening form, appropriateness data were added to information about the final selection decision.

Data analysis

The association between tool recommendations and referral intentions was studied by cross-tabulation (χ 2 test). The same statistical approach was used to analyse differences in acceptance rates of patients screened or not screened by the tool. The predictive value of the tool recommendations (inappropriate versus appropriate/uncertain) was assessed using the common measures for diagnostic tests (sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive value). To study differences in the reasons for refusal between screened and unscreened patients, the Fisher’s exact test was applied.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patients consents

All patient data were anonymously entered in the database. Participants were instructed that the tool outcome (panel recommendation) should in no way interfere with their independent judgment and referral decision. The need for ethical approval differed by national regulations. In Spain, approval was obtained from the Andalusian Health Council, while in Germany no explicit requirements were considered to apply for this type of data collection.

Results

Since February 2007, the programme has run in six European countries involving 29 DBS centres and surrounding regions. Currently, more than 4,000 patient profiles have been entered in the online database. In the remainder of this section, we will restrict our discussion to regions and centres for which data collection has been entirely completed (14 regions/centres in Germany and 1 in Spain). The educational meetings were attended by around 250 neurologists, the majority (n = 208) of whom agreed to participate in the monitoring programme. As of February 2010, 3,128 patient profiles had been completed (mean: 15 patients per participating neurologist). Five-hundred and thirty-nine patients (17%) did not meet the absolute requirements of DBS consideration (first check of the screening tool). Of the remaining 2,589 patients, referral was deemed appropriate in 22%, inappropriate in 35%, and uncertain in 43%. The intention to refer a patient for DBS consideration was strongly associated with the recommendations on appropriateness made by the Stimulus programme: a positive intention was documented in 73, 32 and 2% of patients with, respectively, an appropriate, uncertain or inappropriate referral according to the tool (Pearson χ 2 = 830,613; P < 0.0001). Six months after initial data entry, 28% of patients for whom a positive referral intention was documented had actually been referred to a DBS centre. Principal reasons for not referring a potentially appropriate candidate were the patient’s reluctance to undergo brain surgery (50%) and patient indecision (41%).

For the observational survey in the DBS centres, the mean observation period was 16 months (range 6–24 months). Final selection decisions were documented for 791 patients, of whom 224 (28%) had been screened with the Stimulus tool (Table 1).

Table 1.

Acceptance for DBS (final decisions by DBS centres) in screened versus unscreened patients

| Patient population | Accepted for DBS | |

|---|---|---|

| Number | Percentage | |

| Screened patients (n = 224) | 173 | 77 |

| Inappropriate (n = 8) | 2 | 25 |

| Uncertain (n = 62) | 43 | 69 |

| Appropriate (n = 154) | 128 | 83 |

| Unscreened patients (n = 567) | 270 | 48 |

The acceptance rate of the Stimulus group was significantly higher than that of patients outside the screening programme (77 vs. 48%; Pearson χ 2 = 57,15; P < 0.0001), and was most favourable in patients for whom the outcome of the tool was appropriate (83%). Of patients for whom referral was deemed inappropriate by the tool (n = 8), two were accepted for DBS.

Considering the Stimulus tool as a diagnostic test with the outcome positive (appropriate or uncertain) or negative (inappropriate), and taking the final decision of the DBS centres as the ‘gold standard’ (accepted/refused), the tool showed a high sensitivity and a low specificity (Table 2). The positive and negative predictive values were fairly similar.

Table 2.

Tool outcomes compared to final selection decision by DBS centres

| Decision of DBS centre | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome Stimulus tool | Accepted | Refused | Total |

| Appropriate/uncertain | 171 | 45 | 216 |

| Inappropriate | 2 | 6 | 8 |

| Total | 173 | 51 | 224 |

Sensitivity: 99%; Specificity: 12%; Positive predictive value: 79%; Negative predictive value: 75%

Absolute numbers of patients

A comparison of reasons for refusal (by DBS centres) between screened and unscreened patients is shown in Table 3. In both groups, the top two categories were ‘anti-parkinsonian medication not optimised yet’ and ‘neuropsychological and/or psychiatric disorders’, albeit their frequency was higher in the Stimulus group. None of the differences reached the level of statistical significance (Fisher’s exact test).

Table 3.

Reasons behind refusal for DBS in patients screened and not screened using the Stimulus tool

| Principal reason for refusal | Unscreened (n = 297) | Screened (n = 51) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | |

| Non-idiopathic PD | 37 | 12 | 2 | 4 |

| Insufficient response to levodopa test | 36 | 12 | 5 | 10 |

| Anti-parkinsonian medication not optimised yet | 68 | 23 | 17 | 33 |

| Significant levodopa-resistant axial symptoms | 29 | 10 | 1 | 2 |

| Motor disability not severe enough | 27 | 9 | 6 | 12 |

| Neuropsychological and/or psychiatric disorders | 42 | 14 | 10 | 20 |

| Abnormalities on brain imaging | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Significant co-morbidity | 10 | 3 | 2 | 4 |

| Contra-indication for surgery | 1 | <1 | 2 | 4 |

| Poor motivation/unrealistic expectations patient | 23 | 8 | 3 | 6 |

| Other | 21 | 7 | 2 | 4 |

Based on information from DBS centres following evaluation

Discussion

Similar to observations in the United States [11], we found that in patients referred by general neurologists without the assistance of a screening tool, a substantial proportion (52%) were refused for DBS after evaluation in a specialised DBS centre. In patients for whom the Stimulus tool was applied, the acceptance rate was significantly higher (77%), with most favourable figures in patients for whom referral was deemed appropriate (83%). Taking the final selection decision by DBS centres as the reference value, good to reasonable values were found for the tool’s sensitivity (99%) and positive (79%) and negative (75%) predictive value, while specificity was low (12%). Although generally supporting the tool’s ability to improve the quality of pre-selection for DBS, these results should be considered within the context of the design and data collection of this monitoring project.

Our focus was on the tool’s applicability in daily practice with a minimum burden for participating neurologists. For that reason, data collection was limited and did not, for example, include a reassessment of patients for whom a negative referral decision was made (potential false-negatives). In addition, no follow-up data were collected for these patients, and it is conceivable that some of them were referred in a later phase.

Referral decisions were largely in line with the tool recommendations, and resulted in a low number of inappropriate referrals (n = 8). The low specificity of the tool (2 out of these 8 patients were eventually accepted for DBS) should therefore be interpreted with caution.

Despite the strong association between panel recommendations and referral ‘intentions’, only 28% of patients for whom a positive intention was documented were actually referred during the 6 month follow-up period. In the vast majority of cases (90%) this was related to the patients’ reluctance to undergo brain surgery or their wish to postpone the decision of referral. However, it needs to be considered that patients may change their decision over time if the disease progresses and/or their confidence in DBS increases with further information. Therefore, it is likely that a higher acceptance rate was found when the follow-up period was longer.

Potential shortcomings of the tool may be reflected in the reasons for refusal. For example, the principal reasons for refusal in Stimulus patients were non-optimal anti-parkinsonian medication and the presence of neuropsychological and/or psychiatric disorders. Though not significantly different from the non-Stimulus patients (presumably due to the low number of patients and events), refinement of these criteria by the inclusion of additional checklists or screening tools may be warranted. However, the benefits of a more specific tool should be balanced against the drawback of making it more time-consuming, potentially jeopardising its use in routine neurological care.

Notwithstanding these considerations, we feel that the diagnostic properties of the tool are sufficiently convincing to advocate its use to assist general neurologists in deciding on referral for DBS in patients with PD. Periodic reassessment of the tool is needed in light of changing insights and user experiences. For example, new insights into the role of age [10, 15] and disease duration [16] for patient selection may necessitate reconsideration of the criteria included. We therefore consider the Stimulus tool as a dynamic instrument of which the application could be improved by a continuous process of learning from both science and practice.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the support of all participating referral neurologists and DBS centres. Principal investigators at the DBS centres were: N. Allert (Neurologisches Rehabilitationszentrum Godeshöhe e. V., Bad Godesberg), C. Buhmann (Universitätsklinikum Hamburg Eppendorf), I. Galazky (Otto-von-Guericke-University, Magdeburg), B. Haslinger (Neurologische Klinik und Poliklinik, TU-Muenchen, Munich), F. Hertel (Klinikum Idar-Oberstein), J. Herzog (Christian- Albrechts- University, Kiel), A. Janzen (Bezirksklinikum Regensburg, Regensburg), B. Leinweber (Universitätsklinikum Gießen und Marburg, Marburg), A. Kupsch (Charité, University Medicine Berlin), T. Prokop (Universitätsklinik Freiburg), T. Wächter and R. Krüger (Hertie Institute for Clinical Brain Research, University Hospital Tübingen), H. Wilms (Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg), D. Woitalla (St. Josef- und St. Elisabeth Hospital, Bochum), M. Wolz (Universitätsklinikum Carl Gustav Carus, Dresden), all Germany, and A. Mínguez-Castellanos, F. Escamilla-Sevilla, C. Sáez-Zea, C. Piñana-Plaza (University Hospital Virgen de las Nieves, Granada), Spain. This study was sponsored by Medtronic International Sàrl.

Conflicts of interest

Dr. Wächter received consulting fees, speaker honoraria, travel reimbursement for scientific meetings and research grants from Medtronic, and travel reimbursement for a clinical meeting from Solvay. Dr. Mínguez-Castellanos received consulting fees and a research grant from Medtronic and speaker honoraria/travel reimbursements from Novartis, Lundbeck, GlaxoSmithKline, Boehringer Ingelheim and Medtronic. Dr. Valldeoriola is an advisory board member of UCB Pharmaceuticals and Solvay, and a consultant of Boehringer Ingelheim and Medtronic. He received a grant from Solvay and honoraria from Solvay, Boehringer Ingelheim and Medtronic. Dr. Herzog received reimbursement of travel expenses to scientific meetings from Medtronic. Dr. Stoevelaar received research honoraria from Medtronic, Pfizer, Gen-Probe, Astellas, Novartis and Ipsen.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Contributor Information

Tobias Wächter, Phone: +49-70-712982049, FAX: +49-7071-294839, Email: tobias.waechter@uni-tuebingen.de.

Adolfo Mínguez-Castellanos, Email: aminguezc@meditex.es.

Francesc Valldeoriola, Email: FVALLDE@clinic.ub.es.

Jan Herzog, Email: j.herzog@neurologie.uni-kiel.de.

Herman Stoevelaar, Email: herman.stoevelaar@ismar.com.

References

- 1.Krack P, Batir A, Van Blercom N, et al. Five-year follow-up of bilateral stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus in advanced Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1925–1934. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lyons KE, Pahwa R. Long-term benefits in quality of life provided by bilateral subthalamic stimulation in patients with Parkinson disease. J Neurosurg. 2005;103:252–255. doi: 10.3171/jns.2005.103.2.0252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodriguez-Oroz MC, Obeso JA, Lang AE, et al. Bilateral deep brain stimulation in Parkinson’s disease: a multicentre study with 4 years follow-up. Brain. 2005;128:2240–2249. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schüpbach WM, Chastan N, Welter ML, et al. Stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus in Parkinson’s disease: a 5 year follow-up. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:1640–1644. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.063206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pahwa R, Factor SA, Lyons KE, et al. Practice parameter: treatment of Parkinson disease with motor fluctuations and dyskinesia (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2006;66:983–995. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000215250.82576.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deuschl G, Schade-Brittinger C, Krack P, et al. A randomized trial of deep-brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:896–908. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Østergaard K, Aa Sunde N. Evolution of Parkinson’s disease during 4 years of bilateral deep brain stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus. Mov Disord. 2006;21:624–631. doi: 10.1002/mds.20776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kleiner-Fisman G, Herzog J, Fisman DN, et al. Subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation: summary and meta-analysis of outcomes. Mov Disord. 2006;21(Suppl 14):S290–S304. doi: 10.1002/mds.20962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gan J, Xie-Brustolin J, Mertens P, et al. Bilateral subthalamic nucleus stimulation in advanced Parkinson’s disease: three years follow-up. J Neurol. 2007;254:99–106. doi: 10.1007/s00415-006-0297-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weaver FM, Follett K, Stern M, et al. Bilateral deep brain stimulation vs. best medical therapy for patients with advanced Parkinson disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301:63–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okun MS, Fernandez HH, Pedraza O, et al. Development and initial validation of a screening tool for Parkinson disease surgical candidates. Neurology. 2004;63:161–163. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000133122.14824.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moro E, Allert N, Eleopra R, et al. A decision tool to support appropriate referral for deep brain stimulation in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol. 2009;256:83–88. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-0069-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brook RH, Chassin MR, Fink A, et al. A method for the detailed assessment of the appropriateness of medical technologies. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 1986;2:53–63. doi: 10.1017/S0266462300002774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fitch K, Bernstein SJ, Aguilar MS et al The RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method User’s manual. http://www.rand.org/pubs/monograph_reports/MR1269. Accessed 1 September 2010

- 15.Derost PP, Ouchchane L, Morand D, et al. Is DBS-STN appropriate to treat severe Parkinson disease in an elderly population? Neurology. 2007;68:1345–1355. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000260059.77107.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schüpbach WM, Maltête D, Houeto JL, et al. Neurosurgery at an earlier stage of Parkinson disease: a randomized, controlled trial. Neurology. 2007;68:267–271. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000250253.03919.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]