Synopsis

Eating disorders and obesity in children and adolescents involve harmful behavior and attitude patterns that infiltrate daily functioning. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is well-suited to treat these conditions, given the emphasis on breaking negative behavior cycles. This article reviews the current empirically-supported treatments and the considerations for youth with weight control issues. New therapeutic modalities (i.e., Enhanced CBT and the socio-ecological model) are discussed. Rationale is provided for extending therapy beyond the individual treatment milieu to include the family, peer network, and community domains to promote behavior change, minimize relapse, and support healthy long-term behavior maintenance.

Keywords: cognitive behavioral therapy, eating disorders, obesity, weight control

Children and adolescents who struggle with eating disorders and obesity require clinical attention. Eating- and weight-related difficulties are characterized by maladaptive daily patterns, involving distorted cognitions and problematic behavior cycles. The treatment of weight control issues requires a comprehensive approach, as disordered eating permeates the individual, home, and social environments. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) emphasizes the process of changing habits and attitudes that maintain psychological disorders. Given this focus, CBT is an appropriate treatment approach for eating disorders and obesity. By restructuring the harmful patterns that infiltrate daily functioning, youth will be better positioned to lead healthier lives. Understanding eating disorders and obesity, as well as their representation as a spectrum of weight control issues, is imperative to their successful treatment and prevention.

Weight Control Issues: Understanding Eating Disorders and Obesity

The spectrum of weight control issues spans a variety of behaviors and cognitions and affects a wide range of individuals. These problems typically develop in childhood and adolescence. Often, unhealthy weight-related patterns are difficult to treat, especially because they are entrenched in daily life. Specifically, a heightened emphasis is placed on food, eating, body weight or shape, and control; for many, it functions as an unhealthy coping strategy. As a result, weight control issues significantly impact social functioning and quality of life.

The revised fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR) includes the following eating disorder diagnoses: anorexia nervosa (AN); bulimia nervosa (BN); and eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS) 1, the most commonly diagnosed of the three disorders 2. Included within the current EDNOS category is binge eating disorder (BED); however, it has been proposed as its own formal diagnosis in the upcoming edition of the DSM 3. While individuals with AN are severely underweight, individuals with BN and BED often fluctuate between the normal and overweight ranges.

On the far end of the weight spectrum, childhood obesity has become a major public health concern. Over the past three decades, rates of pediatric overweight and obesity have tripled in the United States 4, making this a national epidemic. Weight classification is used to determine overweight or obese status. For adults, body mass index (BMI) is the standard definition; for children, BMI percentile is used because it is sensitive and easy to obtain 5. BMI is the ratio of weight (in kilograms) per the square of height (in meters), and BMI percentiles refer to age- and sex-specific curves. While this article discusses the classification, associated features and comorbidities, and treatment approaches for eating disorders and obesity, it is important to note that obesity is not considered to be a mental illness; it is neither an eating disorder nor an addiction 6.

Table 1 provides an overview of the current diagnostic criteria, definitions, and prevalence rates for AN, BN, BED, and Obesity.

Table 1.

Overview of the current diagnostic criteria, definitions, and prevalence rates for AN, BN, BED, and Obesity

| Anorexia Nervosa | Bulimia Nervosa | Binge Eating Disorder | Obesity |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. Refusal to maintain body weight at or above a minimally normal weight for age and height (e.g., weight loss leading to maintenance of body weight less than 85% of that expected; or failure to make expected weight gain during period of growth, leading to body weight less than 85% of that expected). |

A. Recurrent episodes of binge eating, characterized by: 1. Eating, in a discrete period of time (e.g., within 2-hours), an amount of food that is definitely larger than most people would eat during a similar period of time or circumstances 2. A sense of lack of control over eating during the episode (e.g., a feeling that one cannot stop eating or control what or how much one is eating) |

A. Recurrent episodes of binge eating, characterized by: 1. Eating, in a discrete period of time (e.g., within 2-hours), an amount of food that is definitely larger than most people would eat during a similar period of time or circumstances 2. A sense of lack of control over eating during the episode (e.g., a feeling that one cannot stop eating or control what or how much one is eating) |

Overweight: 85th to < 95th BMI1 Percentile Obesity: ≥ 95th BMI Percentile |

| B. Intense fear of gaining weight or becoming fat, even though underweight. |

B. Recurrent inappropriate compensatory behavior, such as self- induced vomiting; misuse of laxatives, diuretics, enemas, or other medications; fasting; or excessive exercise. |

B. Binge eating episodes are associated with 3 (or more) of the following: 1. Eating much more rapidly than usual 2. Eating until uncomfortably full 3. Eating large amounts of food when not feeling physically hungry 4. Eating alone because of being embarrassed by how much one is eating 5. Feeling disgusted with oneself, depressed, or very guilty after overeating |

|

| C. Disturbance in the way one’s body weight or shape is experienced, undue influence of body weight or shape on self- evaluation, or denial of the seriousness of current low body weight. |

C. The binge eating and inappropriate compensatory behaviors both occur, on average, ≥2 times a week for 3 months.2 |

C. Marked distress regarding binge eating is present. |

|

| D. In postmenarcheal females, amenorrhea (absence of ≥3 consecutive menstrual cycles).3 |

D. Self-evaluation is unduly influenced by body shape and weight. |

D. The binge eating occurs, on average, ≥2 days a week for 6 months.4 |

|

| E. The disturbance does not occur exclusively during episodes of AN. |

E. The binge eating is not associated with the regular use of inappropriate compensatory behaviors and does not occur exclusively during episodes of AN or BN. |

||

|

| |||

| Prevalence Estimates: 0.3 – 3.7% | Prevalence Estimates: 1.0 – 4.2% | Prevalence Estimates: 0.7 – 3.0% | Prevalence Estimates: Obesity: 16.3% Overweight & Obesity: 31.9% |

Body Mass Index (BMI) = weight (kilograms)/height (meters2); BMI percentile = age- and sex-specific curves.

Reduction of this criterion to one time per week for 3 months has been proposed for DSM-V.

Removal of this criterion has been proposed for DSM-V.

Reduction of this criterion to one time per week for 3 months has been proposed for DSM-V.

Clinical Features

Weight control issues are associated with several medical and psychological complications. Patients with eating disorders struggle with body-related cognitive distortions (i.e., body dissatisfaction over-concern with weight and shape shame and guilt) and disordered eating behaviors (i.e., extreme weight loss methods, restrictive dieting, inappropriate compensatory behaviors). In addition, these individuals often experience psychosocial problems, including social isolation, low self-esteem, secretiveness about eating, and stigmatization 7,8. Eating disorders are also highly comorbid with other psychological disorders, such as depression, anxiety, and impulse control disorders 9,10. Severe medical complications, as a result of the starvation associated with AN, and the repeated binge/purge cycle characteristic of BN, are common. These include: metabolic changes (e.g., electrolyte imbalances); osteoporosis; dental, gastric, and renal abnormalities; dysregulated body temperature; irregular or loss of menses; appetite control dysregulation; and weight fluctuation 11-13. Adolescent binge and loss of control eating are related to excessive weight gain, which is associated with multiple problems, as discussed below 13-15. Although the physical presentation may look similar to that of obese youth, children and adolescents with BED and loss of control eating experience distinct psychopathology symptoms related to eating, mood, and anxiety disorders that are not reported by their non-eating-disordered obese counterparts 16.

Youth who struggle with overweight and obesity often face medical and psychological complications, as well. Notably, depression, feelings of worthlessness, low self-esteem, stigmatization, and teasing are associated psychological sequelae 17-19. Additional difficulties include poor academic performance and behavioral problems 20. Excessive weight is correlated with cardiovascular problems (e.g., heart disease, hypertension, high blood pressure, and high lipid profiles), diabetes, stroke, joint and bone pain or disease, cancer, and obstructive sleep apnea 20. Moreover, these children and adolescents often engage in disordered eating behaviors 21, which exacerbate the negative medical and psychological consequences of maladaptive eating patterns.

Thus, weight control issues represent serious problems that need to be addressed. Given that children and adolescents who display maladaptive eating behaviors are likely to develop additional weight-related difficulties 14,22-24, treating their current weight issues will both reduce the resultant medical and psychological problems and prevent future unhealthy patterns. Understanding the current risk factors and treatment approaches for weight management issues will improve the clinical responsiveness to youth who present with these problems.

Developing and Maintaining Factors

Multiple factors increase youths’ risk for the development of weight control issues. Body dissatisfaction, dietary restriction, overvaluation of weight and shape, negative affect, and low self-esteem are the core cognitions that place individuals at risk 25. Specific vulnerabilities, known as appetitive traits, have been linked to eating behavior and physical activity preferences 26. Satiety responsiveness (e.g., failure to recognize hunger cues), impulsivity (e.g., inability to postpone immediate rewards), and high motivation to eat are heritable and predictive of excessive weight gain 27. Interpersonal difficulties, including sensitivity and teasing 28,29, can propel the use of or control over food as a negative coping strategy. In addition, history of depression and history of teasing by a teacher or coach have been linked to the onset of an eating disorder 30. Weight control issues in childhood represent another critical risk factor. Being overweight as a child can lead to later development of eating disorder psychopathology and/or obesity 22,23,31. Loss of control and/or binge eating at a young age places youth at risk for developing the symptoms consistent with diagnostic criteria for BED 32 and for becoming obese 14,24.

The child’s environment further complicates the risk for weight gain and disordered eating pathology. Negative parental role modeling of unhealthy eating and activity patterns can lead children to develop maladaptive habits. Furthermore, recent trends towards increased sedentary behavior, meals eaten away from home, and consumption of high energy-density foods and drinks hinder healthy lifestyle choices for youth 33,34.

While these factors place individuals at risk, they also serve to maintain disordered weight control patterns. For example, there is often a negative cyclical relationship between weight-related behavior and depression 35 and interpersonal difficulties 17,25. As these patterns continue, they become more strongly entrenched in daily life and more difficult to modify. Thus, the need to intervene early is evident.

Treatment Considerations: The Need for Early Intervention

Habits start young, and in turn, interventions should follow suit. In fact, interventions that break maladaptive behavior patterns before they become ingrained have greater potential for success. This is particularly noteworthy because shorter duration and reduced severity of symptoms are associated with better outcomes 5,36-39; recovery rates for adolescents with eating disorders are higher than those for adults 8. Thus, through early intervention, children and adolescents are more likely to respond to treatment.

When intervening with youth, it is particularly important to include the parents and family in the treatment process. Parents can facilitate positive behavior change by creating a healthful home environment and minimizing negative stimuli to support healthy habits. For those children and adolescents who may be resistant to treatment, parents are able to serve as enforcers of necessary modifications. Furthermore, parents can model healthy lifestyle choices and reinforce the youth’s progress.

While early intervention is effective, it is equally crucial to direct our focus to prevention. Prevention efforts offer the opportunity to reduce the onset and prevalence of weight-related problems. As our understanding of risk factors and predictors of treatment outcome has evolved, we are well-equipped to develop appropriate preventive strategies. Further, because obesity is cyclical (i.e., overweight parents are more likely to have overweight children, who are also more likely to become overweight adults) 40,41, increased initiatives for parents and children would enable a necessary decline in the increasing weight trends. Successful pioneering research in this domain demonstrates the utility of preventive work 42-48.

Empirical Support for the Treatment of Eating Disorders and Obesity in Youth

Eating Disorders

CBT is the most established psychological treatment for BN and BED 49, with demonstrated efficacy over pharmacological and other psychological therapeutic options 50. The goal of treatment is to identify, monitor, and tackle the cognitions and behaviors that maintain the disorder while heightening the motivation for change 49,51-53. Given that the need for treatment far outweighs the availability of practitioners 54, current efforts are focused on increasing dissemination by modifying the traditional CBT manual into guided self help 55-57 and computer- and Internet-based versions 58,59.

Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) is the only psychological treatment for BN and BED to show comparable efficacy to CBT 60, and for certain groups, there may be increased benefits 57,61. IPT helps patients connect their binge and/or purge behaviors to interpersonal difficulties; the therapist highlights how a social arena can function as both a causal and a maintaining factor for binge eating, but can also be used as an avenue through which to build support for recovery. Given the emphasis of IPT on current relationships, it is particularly effective for youth, for whom the social network is of heightened importance 62,63. IPT has been effective for use in individual 57,64 and group formats 65-67 and has demonstrated positive results for the prevention of excessive weight gain in overweight adolescents 13,68. Recent studies have found that IPT, as adapted for youth, can also be effectively disseminated into community-based settings 63. Current efforts are underway to improve IPT dissemination for the eating disorder population.

Treatment research on AN has been much more scant, in part due to difficulties with participant recruitment and retention 37,69. Results of studies have provided little support for specialized psychotherapies or pharmacotherapies, conducted with both underweight and weight-restored individuals 70-79. However, family-based therapy—one established form of which is the Maudsley approach—has been effective in treating adolescents with AN 80,81. The treatment focuses on empowering the family to serve as agents of change in helping the ill adolescent reach recovery. The therapist works collaboratively with the family to help the patient regain weight, regulate disordered eating behaviors, and promote healthy adolescent development and independence.

While the DSM-IV uses a categorical classification system of mutually-exclusive diagnoses, patients with eating disorders often develop symptoms consistent with more than one diagnosis over the course of their illness, demonstrating shifts between diagnoses known as diagnostic crossover 82,83. To more effectively address this, an enhanced, “transdiagnostic” approach to CBT has been established 84, with the goal of treating eating disorder psychopathology across diagnoses, rather than a specific diagnosis. The treatment addresses the shared, underlying core beliefs (i.e., over-evaluating and controlling one’s weight and shape) in order to break the maladaptive cognitive and behavior patterns that have maintained the eating disorder 25,85,86.

There are two forms of the enhanced CBT (CBT-E): focused (CBT-Ef) and broad (CBT-Eb). CBT-Ef is considered the “default” version and targets the eating disorder psychopathology. The broad version addresses these same issues, but includes an additional focus on external factors that maintain the disorder and make behavior change more difficult. In particular, patients with low self-esteem, poor mood-regulation strategies, high interpersonal problems, and high levels of clinical perfectionism are well-suited for CBT-Eb, in which these four core features are targeted. Both forms of treatment are delivered weekly for twenty sessions in an outpatient setting. CBT-E consists of four phases that modify maladaptive behaviors and negative pathology and teach strategies for relapse prevention. For those entering treatment at low weight (BMI ≤17.5), forty weekly sessions are recommended with an additional focus on weight regain.

Obesity

Lifestyle interventions represent the most successful treatment for childhood obesity 5,38 and have been shown to be more effective than psychoeducation alone 87. Furthermore, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends that children ages 6 to 18 years old be screened by pediatricians and offered multi-component, moderate-to-intense treatment to address obesity 88; this recommended treatment is directly in line with the lifestyle intervention approach. Lifestyle interventions use a multi-component approach to modify children’s daily practices into healthy habits (i.e., healthier diets and increased physical activity), which promotes long-term behavior maintenance 5,89. These interventions include behavioral components and cognitive skills training to target weight-related behavior. For the majority of programs, the behavioral aspects of weight treatment are central; however, programs that supplement the behavioral approaches with cognitive restructuring and relapse-prevention techniques may result in increased treatment effectiveness 90-92.

Interventions with behavioral components that modify both diet and activity (i.e., physical activity and/or sedentary behavior, during which few or no calories are burned, such as while watching TV) have been demonstrated to be the most effective for overweight youth 93-96 and are recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force 88. Another key component of lifestyle interventions is the involvement of the family for support. Family-based behavioral interventions, which include parents in the treatment process, have been demonstrated to be effective in promoting weight control and healthy habit development over the past 30 years 87,94,97,98.

Among treatment programs, several behavioral change components have been shown to support healthy weight control. Specifically, intervention strategies focus on stimulus control (e.g., restructuring the home to encourage healthy behaviors and limit unhealthy behaviors associated with eating and activity) and self-monitoring of weight, eating, and physical activity 89,90,95,99,100. In family-based interventions, parents take an active role in treatment. They are instructed to serve as models for their children by monitoring and modifying their own behaviors, since parent success with weight control is predictive of child success 101. Parents are also encouraged to utilize a behavioral reward system, in which successful goal completion (e.g., weight loss, reduced caloric intake, increased physical activity) is reinforced with rewards that are interpersonal and/or promote healthy behavior (e.g., family outings, bike riding, ice skating) 102. Family praise is also encouraged to reinforce positive behaviors. In addition, parents are educated about key parenting behaviors, including modeling, providing consistent reinforcement, and utilizing stimulus control techniques to restructure the home environment. All of these skills help families to develop healthy behaviors.

From a Clinical Perspective: Extending Beyond the Individual Treatment Milieu

While successful treatments programs have been established, relapse and non-recovery still remain a significant problem 8,38. Within the eating disorder field, many recovered patients subsequently resume their binge and/or purge behaviors and individuals with AN often do not complete treatment, dropping out prematurely 37,75,103. Family-based behavioral treatment for obesity has been shown to be successful in the short-term 87, but the targeted healthy behaviors are difficult to sustain over time. Many people who lose weight during the intervention experience weight regain 99,104,105.

Although relapse prevention is addressed in each of these treatments, more effective strategies are necessary that extend beyond the individual treatment milieu. The persistence of weight-related problems may occur because environmental stimuli, which had fostered the previously learned, maladaptive behaviors, have not been modified 106. Given that individual behaviors related to eating and activity are influenced by complex interactions between socio-environmental factors and biological phenomena, multiple drivers of behavior must be considered to encourage sustained behavior change 107. Thus, without addressing the environmental context, children and adolescents are cued to relapse into prior behavior patterns.

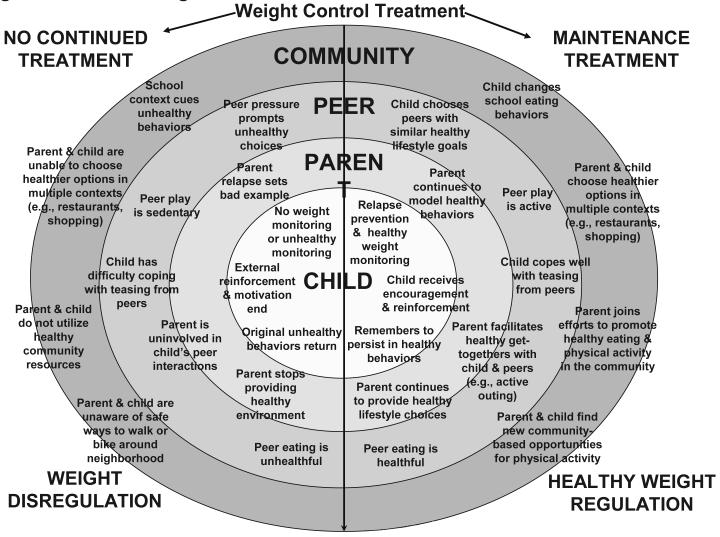

The multiple behavioral drivers can be conceptualized together within a socio-ecological model 108, which can then be incorporated into a weight management treatment program. Specifically, this model posits that factors within the individual/family, peer/social, and community domains serve as important foci throughout treatment 107,108. The social and physical environments include the availability of peers and resources to support and promote healthy eating and activity patterns (Fig 1). For individuals who do not receive treatment, harmful patterns are cued; for those who do receive treatment, healthful behaviors are reinforced.

Figure 1.

Socio-ecological model of cued behaviors. Adapted and reprinted from Wilfley, et al, 2010.

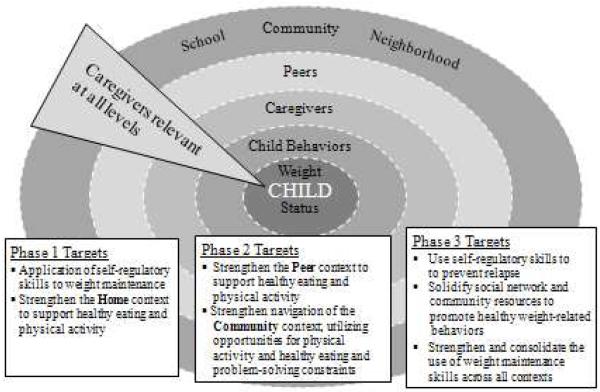

Throughout treatment, exploring each domain for stimuli that encourage or hinder healthy behaviors is important; this provides the foundation from which to promote positive behavior change. Key areas to assess include interpersonal relationships and difficulties, as well as the accessibility and utilization of healthy resources within the home, peer network, and community (Fig 2).

Figure 2.

The Socio-Ecological Model treatment targets

The socio-ecological model was tested in a large-scale randomized controlled trial 91. This study was designed to target weight maintenance in children and was the first to focus on pediatric long-term weight control. The results indicate that continued contact and focus on the child’s social ecology are critical treatment components 91. Furthermore, data from computer biosimulation models suggest a socio-ecological emphasis within family-based maintenance interventions produces sustained behavior changes, due to the extension into multiple contexts 106. The results also provide support for the increased duration and intensity of weight maintenance treatment to improve effectiveness over time.

Discussion and Future Directions

The socio-ecological approach helps to enhance an individual’s likelihood of success. The treatment targets extend beyond the individual to incorporate a supportive environment, which more comprehensively addresses the multi-contextual problem of weight control. Involving the family, peers, healthcare providers, and community network is crucial. For example, families should take responsibility to create a healthy home environment: eat regular meals together; avoid bringing home foods that encourage unhealthy eating or electronics that promote sedentary behavior; plan fun and active family outings; and facilitate open communication with youth about daily pressures. Leaders in schools should advocate for healthier meal and snack options, as well as more physically active classes and school-wide events. Communities should offer facilities, clubs, and activities that promote healthy lifestyles, including fitness classes, healthy restaurants, and farmers’ markets. On the whole, educating people and providers across the various contexts will enable effective and long-lasting change on a broader scale.

Given the establishment of effective treatments for eating disorders and weight control, the next step is to disseminate this work. Translational research promotes the extension of laboratory findings into everyday practice; this is particularly relevant for addressing the national obesity epidemic. Training community people and providers to recognize disordered eating patterns and unhealthy weight status will likely make early detection and intervention more feasible, and in turn, has the potential to further our prevention efforts. Moreover, instructing providers in the delivery of the established, manual-based treatments will advance treatment practices and reach. Additionally, we should continue to expand research across populations. Studying additional ages and racial/ethnic groups may offer insight into the manifestation of disordered weight control patterns and key treatment factors that need to be addressed to ensure widespread treatment success.

Conclusion

The parallels between eating disorders and obesity allow for the discussion of these issues along a weight control continuum. Within the eating disorders field, specialized psychotherapies (e.g., CBT and IPT) remain effective modalities for the individual eating disorder diagnoses, and a “transdiagnostic” approach (i.e., CBT-E) has been developed to better address symptom fluctuation between diagnostic categories. For obesity, family-based behavioral treatment programs are the most effective, and the incorporation of targeted cognitive skills are useful additions. These lifestyle interventions are enhanced when applied through a socio-ecological framework. Across the spectrum, treatment approaches should encourage the family, peer network, and community to create supportive environments. Ultimately, we need to intervene early to have the best likelihood of helping children and adolescents to improve daily functioning and lead healthy lives.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Contributor Information

Denise E. Wilfley, Professor of Psychiatry, Medicine, Pediatrics, and Psychology, Department of Psychiatry, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri.

Rachel P. Kolko, Department of Psychology, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, Missouri.

Andrea E. Kass, Department of Psychology, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, Missouri.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Author; Washington, D. C.: 2000. text rev. ed. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fairburn CG, Bohn K. Eating disorder NOS (EDNOS): an example of the troublesome “not otherwise specified” (NOS) category in DSM-IV. Behav Res Ther. 2005 Jun;43(6):691–701. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Psychiatric Association Proposed draft revisions to DSM disorders and criteria. 2010 http://www.dsm5.org/Pages/Default.aspx.

- 4.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999-2004. Jama. 2006 Apr 5;295(13):1549–1555. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barlow SE. Expert committee recommendations regarding the prevention, assessment, and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity: summary report. Pediatrics. 2007 Dec;120(Suppl 4):S164–192. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2329C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson GT. Eating disorders, obesity and addiction. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2010 Sep-Oct;18(5):341–351. doi: 10.1002/erv.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldschmidt AB, Hilbert A, Manwaring JL, et al. The significance of overvaluation of shape and weight in binge eating disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2010 Mar;48(3):187–193. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Psychiatric Association. American Psychiatric Association Treatment of patients with eating disorders,third edition. Am J Psychiatry. 2006 Jul;163(7 Suppl):4–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beumont PJV. Clinical presentation of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. In: Brownell CGFK, editor. Eating disorders and obesity: A comprehensive handbook. 2nd ed. Guilford Press; New York: 2002. pp. 162–170. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bulik CM. Anxiety, depression, and eating disorders. In: Brownell CGFK, editor. Eating disorders and obesity: A comprehensive handbook. 2nd ed. Guilford Press; New York: 2002. pp. 193–198. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pomeroy C, Mitchell JE. Medical complications of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. In: Fairburn CG, Brownell KD, editors. Eating disorders and obesity: A comprehensive handbook. 2nd ed. Guilford Press; New York: 2002. pp. 278–285. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldstein MA, Herzog DB, Misra M, Sagar P. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 29-2008. A 19-year-old man with weight loss and abdominal pain. N Engl J Med. 2008 Sep 18;359(12):1272–1283. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcpc0804641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Wilfley DE, Young JF, et al. Preventing excessive weight gain in adolescents: interpersonal psychotherapy for binge eating. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007 Jun;15(6):1345–1355. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Cohen ML, Yanovski SZ, et al. A prospective study of psychological predictors of body fat gain among children at high risk for adult obesity. Pediatrics. 2006 Apr;117(4):1203–1209. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanofsky-Kraff M. Binge eating among children and adolescents. In: Jelalian E, Steele R, editors. Handbook of Child and Adolescent Obesity. Springer; New York: 2008. pp. 42–57. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glasofer DR, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Eddy KT, et al. Binge eating in overweight treatment-seeking adolescents. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007 Jan-Feb;32(1):95–105. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsl012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldschmidt AB, Sinton MM, Aspen VP, et al. Psychosocial and familial impairment among overweight youth with social problems. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2010 Mar 17; doi: 10.3109/17477160903540727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.BeLue R, Francis LA, Colaco B. Mental health problems and overweight in a nationally representative sample of adolescents: effects of race and ethnicity. Pediatrics. 2009 Feb;123(2):697–702. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hayden-Wade HA, Stein RI, Ghaderi A, Saelens BE, Zabinski MF, Wilfley DE. Prevalence, characteristics, and correlates of teasing experiences among overweight children vs. non-overweight peers. Obes Res. 2005 Aug;13(8):1381–1392. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.August GP, Caprio S, Fennoy I, et al. Prevention and treatment of pediatric obesity: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline based on expert opinion. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008 Dec;93(12):4576–4599. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldschmidt AB, Aspen VP, Sinton MM, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Wilfley DE. Disordered eating attitudes and behaviors in overweight youth. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008 Feb;16(2):257–264. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fairburn CG, Welch SL, Doll HA, Davies BA, O’Connor ME. Risk factors for bulimia nervosa. A community-based case-control study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997 Jun;54(6):509–517. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830180015003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stice E, Whitenton K. Risk factors for body dissatisfaction in adolescent girls: a longitudinal investigation. Dev Psychol. 2002 Sep;38(5):669–678. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.38.5.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stice E, Presnell K, Spangler D. Risk factors for binge eating onset in adolescent girls: a 2-year prospective investigation. Health Psychol. 2002 Mar;21(2):131–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Shafran R. Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders: a “transdiagnostic” theory and treatment. Behav Res Ther. 2003 May;41(5):509–528. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(02)00088-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carnell S, Wardle J. Appetitive traits and child obesity: measurement, origins and implications for intervention. Proc Nutr Soc. 2008 Nov;67(4):343–355. doi: 10.1017/S0029665108008641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carnell S, Wardle J. Appetitive traits in children. New evidence for associations with weight and a common, obesity-associated genetic variant. Appetite. 2009 Oct;53(2):260–263. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2009.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taylor CB, Bryson S, Celio Doyle AA, et al. The adverse effect of negative comments about weight and shape from family and siblings on women at high risk for eating disorders. Pediatrics. 2006 Aug;118(2):731–738. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Warschburger P. The unhappy obese child. Int J Obes (Lond) 2005 Sep;29(Suppl 2):S127–129. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jacobi C, Fittig E, Bryson SW, Wilfley DE, Kraemer HC, Taylor CB. Who is really at risk: Identifying risk factors for subthreshold and full eating disorders in a high-risk sample. Psychological Medicine. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710002631. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Striegel-Moore RH, Fairburn CG, Wilfley DE, Pike KM, Dohm FA, Kraemer HC. Toward an understanding of risk factors for binge-eating disorder in black and white women: a community-based case-control study. Psychol Med. 2005 Jun;35(6):907–917. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704003435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Shomaker LB, Roza CA, et al. A prospective study of pediatric loss of control eating and psychological outcomes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. doi: 10.1037/a0021406. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ayala GX, Rogers M, Arredondo EM, et al. Away-from-home food intake and risk for obesity: examining the influence of context. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008 May;16(5):1002–1008. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gordon-Larsen P, Nelson MC, Popkin BM. Longitudinal physical activity and sedentary behavior trends: adolescence to adulthood. Am J Prev Med. 2004 Nov;27(4):277–283. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luppino FS, de Wit LM, Bouvy PF, et al. Overweight, obesity, and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010 Mar;67(3):220–229. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Epstein LH, Valoski AM, Kalarchian MA, McCurley J. Do children lose and maintain weight easier than adults: a comparison of child and parent weight changes from six months to ten years. Obes Res. 1995 Sep;3(5):411–417. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1995.tb00170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Agras WS, Brandt HA, Bulik CM, et al. Report of the National Institutes of Health workshop on overcoming barriers to treatment research in anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2004 May;35(4):509–521. doi: 10.1002/eat.10261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spear BA, Barlow SE, Ervin C, et al. Recommendations for treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity. Pediatrics. 2007 Dec;120(Suppl 4):S254–288. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2329F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berkman ND, Lohr KN, Bulik CM. Outcomes of eating disorders: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Eat Disord. 2007 May;40(4):293–309. doi: 10.1002/eat.20369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Whitaker RC, Wright JA, Pepe MS, Seidel KD, Dietz WH. Predicting obesity in young adulthood from childhood and parental obesity. N Engl J Med. 1997 Sep 25;337(13):869–873. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709253371301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Serdula MK, Ivery D, Coates RJ, Freedman DS, Williamson DF, Byers T. Do obese children become obese adults? A review of the literature. Prev Med. 1993 Mar;22(2):167–177. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1993.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Neumark-Sztainer D, Flattum CF, Story M, Feldman S, Petrich CA. Dietary approaches to healthy weight management for adolescents: the New Moves model. Adolesc Med State Art Rev. 2008 Dec;19(3):421–430. viii. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taylor CB, Bryson S, Luce KH, et al. Prevention of eating disorders in at-risk college-age women. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006 Aug;63(8):881–888. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.8.881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kohn M, Rees JM, Brill S, et al. Preventing and treating adolescent obesity: a position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. J Adolesc Health. 2006 Jun;38(6):784–787. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shaw H, Stice E, Becker CB. Preventing eating disorders. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2009 Jan;18(1):199–207. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Franko DL, Mintz LB, Villapiano M, et al. Food, mood, and attitude: reducing risk for eating disorders in college women. Health Psychol. 2005 Nov;24(6):567–578. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.6.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Austin SB, Kim J, Wiecha J, Troped PJ, Feldman HA, Peterson KE. School-based overweight preventive intervention lowers incidence of disordered weight-control behaviors in early adolescent girls. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007 Sep;161(9):865–869. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.9.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jones M, Luce KH, Osborne MI, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of an internet-facilitated intervention for reducing binge eating and overweight in adolescents. Pediatrics. 2008 Mar;121(3):453–462. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wilson GT, Grilo CM, Vitousek KM. Psychological treatment of eating disorders. Am Psychol. 2007 Apr;62(3):199–216. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.3.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wilson GT. Psychological treatment of eating disorders. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:439–465. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wilson GT, Fairburn CG, Agras WS. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for bulimia nervosa. In: Garner DM, Garfinkel PE, editors. Handbook of treatment for eating disorders. 2nd ed. Guilford Press; New York: 1997. pp. 67–93. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wilfley DE. Psychological treatment of binge eating disorder. In: Fairburn CGB, K D, editors. Eating disorders and obesity: A comprehensive handbook. 2nd ed. The Guilford Press; New York: 2002. pp. 350–353. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fairburn CG. Overcoming binge eating. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Insel TR. Translating scientific opportunity into public health impact: a strategic plan for research on mental illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009 Feb;66(2):128–133. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schmidt U, Lee S, Beecham J, et al. A randomized controlled trial of family therapy and cognitive behavior therapy guided self-care for adolescents with bulimia nervosa and related disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2007 Apr;164(4):591–598. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.4.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Striegel-Moore RH, Wilson GT, DeBar L, et al. Cognitive behavioral guided self-help for the treatment of recurrent binge eating. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010 Jun;78(3):312–321. doi: 10.1037/a0018915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wilson GT, Wilfley DE, Agras WS, Bryson SW. Psychological treatments of binge eating disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010 Jan;67(1):94–101. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sanchez-Ortiz VC, Munro C, Stahl D, et al. A randomized controlled trial of internet-based cognitive-behavioural therapy for bulimia nervosa or related disorders in a student population. Psychol Med. 2010 Apr 21;:1–11. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710000711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schmidt U, Andiappan M, Grover M, et al. Randomised controlled trial of CD-ROM-based cognitive-behavioural self-care for bulimia nervosa. Br J Psychiatry. 2008 Dec;193(6):493–500. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.046607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wilson GT, Shafran R. Eating disorders guidelines from NICE. Lancet. 2005 Jan 1-7;365(9453):79–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17669-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chui W, Safer DL, Bryson SW, Agras WS, Wilson GT. A comparison of ethnic groups in the treatment of bulimia nervosa. Eat Behav. 2007 Dec;8(4):485–491. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Young JF, Mufson L. Manual for Interpersonal Psychotherapy-Adolescent Skills Training (IPT-AST) Columbia University; New York, NY: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mufson L. Interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents (IPT-A): Extending the reach from academic to community settings. Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2010;15(2):66–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-3588.2009.00556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Marcus MD, Wing RR, Fairburn CG. Cognitive behavioral treatment of binge eating vs. behavioral weight control on the treatment of binge eating disorder. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 1995;17:S090. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Telch CF, Agras WS, Rossiter EM, Wilfley DE, Kenardy J. Group cognitive-behavioral treatment for the nonpurging bulimic: an initial evaluation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1990 Oct;58(5):629–635. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.58.5.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wilfley DE, Agras WS, Telch CF, et al. Group cognitive-behavioral therapy and group interpersonal psychotherapy for the nonpurging bulimic individual: a controlled comparison. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1993 Apr;61(2):296–305. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.2.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wilfley DE, Welch RR, Stein RI, et al. A randomized comparison of group cognitive-behavioral therapy and group interpersonal psychotherapy for the treatment of overweight individuals with binge-eating disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002 Aug;59(8):713–721. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.8.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Wilfley DE, Young JF, et al. A pilot study of interpersonal psychotherapy for preventing excess weight gain in adolescent girls at-risk for obesity. Int J Eat Disord. 2009 Oct 30; doi: 10.1002/eat.20773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Halmi KA. The perplexities of conducting randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled treatment trials in anorexia nervosa patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2008 Oct;165(10):1227–1228. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08060957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Channon S, de Silva P, Hemsley D, Perkins R. A controlled trial of cognitive-behavioural and behavioural treatment of anorexia nervosa. Behav Res Ther. 1989;27(5):529–535. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(89)90087-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pike KM, Walsh BT, Vitousek K, Wilson GT, Bauer J. Cognitive behavior therapy in the posthospitalization treatment of anorexia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry. 2003 Nov;160(11):2046–2049. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.11.2046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.McIntosh VV, Jordan J, Carter FA, et al. Three psychotherapies for anorexia nervosa: a randomized, controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2005 Apr;162(4):741–747. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.4.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Serfaty MA, Turkington D, Heap M, Ledsham L, Jolley E. Cognitive therapy versus dietary counseling in the outpatient treatment of anorexia nervosa: Effects of the treatment phase. European Eating Disorders Review. 1999;7:334–350. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Halmi KA. A multi-site study of AN treatment involving CBT and fluoxetine treatment in prevention of relapse: A 6-month treatment analysis; Paper presented at: Annual meeting of the Eating Disorders Research Society1999; San Diego, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Halmi KA, Agras WS, Crow S, et al. Predictors of treatment acceptance and completion in anorexia nervosa: implications for future study designs. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005 Jul;62(7):776–781. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.7.776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ball J, Mitchell P. A randomized controlled study of cognitive behavior therapy and behavioral family therapy for anorexia nervosa patients. Eat Disord. 2004 Winter;12(4):303–314. doi: 10.1080/10640260490521389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Walsh BT, Kaplan AS, Attia E, et al. Fluoxetine after weight restoration in anorexia nervosa: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2006 Jun 14;295(22):2605–2612. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.22.2605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Attia E, Haiman C, Walsh BT, Flater SR. Does fluoxetine augment the inpatient treatment of anorexia nervosa? Am J Psychiatry. 1998 Apr;155(4):548–551. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.4.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kaye WH, Nagata T, Weltzin TE, et al. Double-blind placebo-controlled administration of fluoxetine in restricting- and restricting-purging-type anorexia nervosa. Biol Psychiatry. 2001 Apr 1;49(7):644–652. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)01013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lock J, le Grange D. Family-based treatment of eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2005;37(Suppl):S64–67. doi: 10.1002/eat.20122. discussion S87-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lock J. Treating adolescents with eating disorders in the family context. Empirical and theoretical considerations. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2002 Apr;11(2):331–342. doi: 10.1016/s1056-4993(01)00009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Eddy KT, Dorer DJ, Franko DL, Tahilani K, Thompson-Brenner H, Herzog DB. Diagnostic crossover in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: implications for DSM-V. Am J Psychiatry. 2008 Feb;165(2):245–250. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07060951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fairburn CG, Harrison PJ. Eating disorders. Lancet. 2003 Feb 1;361(9355):407–416. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12378-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Doll HA, et al. Transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioral therapy for patients with eating disorders: a two-site trial with 60-week follow-up. Am J Psychiatry. 2009 Mar;166(3):311–319. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08040608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Murphy R, Straebler S, Cooper Z, Fairburn CG. Cognitive behavioral therapy for eating disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2010 Sep;33(3):611–627. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Fairburn CG. Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. Guilford Press; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wilfley DE, Tibbs TL, Van Buren DJ, Reach KP, Walker MS, Epstein LH. Lifestyle interventions in the treatment of childhood overweight: a meta-analytic review of randomized controlled trials. Health Psychol. 2007 Sep;26(5):521–532. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.5.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Screening for obesity in children and adolescents: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Pediatrics. 2010 Feb;125(2):361–367. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Faith MS, Saelens BE, Wilfley DE, Allison DB. Behavioral treatment of childhood and adolescent obesity: Current status, challenges, and future directions. In: Thompson JK, Smolak L, editors. Body Image, Eating Disorders, and Obesity in Youth: Assessment, Prevention, and Treatment. American Psychological Association; Washington, D. C.: 2001. pp. 313–319. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Graves T, Meyers AW, Clark L. An evaluation of parental problem-solving training in the behavioral treatment of childhood obesity. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988 Apr;56(2):246–250. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.2.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wilfley DE, Stein RI, Saelens BE, et al. Efficacy of maintenance treatment approaches for childhood overweight: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2007 Oct 10;298(14):1661–1673. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.14.1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Herrera EA, Johnston CA, Steele RG. A comparison of cognitive and behavioral treatments for pediatric obesity. Children’s Health Care. 2004;33:151–167. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Jelalian E, Saelens BE. Empirically supported treatments in pediatric psychology: pediatric obesity. J Pediatr Psychol. 1999 Jun;24(3):223–248. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/24.3.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tsiros MD, Sinn N, Coates AM, Howe PR, Buckley JD. Treatment of adolescent overweight and obesity. Eur J Pediatr. 2008 Jan;167(1):9–16. doi: 10.1007/s00431-007-0575-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Young KM, Northern JJ, Lister KM, Drummond JA, O’Brien WH. A meta-analysis of family-behavioral weight-loss treatments for children. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007 Mar;27(2):240–249. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Epstein LH, Paluch RA, Gordy CC, Dorn J. Decreasing sedentary behaviors in treating pediatric obesity. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000 Mar;154(3):220–226. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.3.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Epstein LH, Wing RR, Woodall K, Penner BD, Kress MJ, Koeske R. Effects of family-based behavioral treatment on obese 5- to 8-year-old children. Behavior Therapy. 1985;16:205–212. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Epstein LH, Paluch RA, Roemmich JN, Beecher MD. Family-based obesity treatment, then and now: twenty-five years of pediatric obesity treatment. Health Psychol. 2007 Jul;26(4):381–391. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.4.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Epstein LH, Myers MD, Raynor HA, Saelens BE. Treatment of pediatric obesity. Pediatrics. 1998 Mar;101(3 Pt 2):554–570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wilfley DE, Saelens BE. Epidemiology and causes of obesity in children. In: Fairburn CG, Brownell KD, editors. Eating disorders and obesity: A comprehensive handbook. 2nd ed. Guilford Press; New York: 2002. pp. 429–432. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wrotniak BH, Epstein LH, Paluch RA, Roemmich JN. Parent weight change as a predictor of child weight change in family-based behavioral obesity treatment. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004 Apr;158(4):342–347. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.4.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Dietz WH, Robinson TN. Clinical practice. Overweight children and adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2005 May 19;352(20):2100–2109. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp043052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Stein RI, Saelens BE, Dounchis JZ, Lewczyk CM, Swenson AK, Wilfley DE. Treatment of eating disorders in women. The Counseling Psychologist. 2001;29:695–732. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Jeffery RW, Drewnowski A, Epstein LH, et al. Long-term maintenance of weight loss: current status. Health Psychol. 2000 Jan;19(1 Suppl):5–16. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.19.suppl1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Wadden TA, Butryn ML, Byrne KJ. Efficacy of lifestyle modification for long-term weight control. Obes Res. 2004 Dec;12(Suppl):151S–162S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Wilfley DE, Van Buren DJ, Theim KR, et al. The use of biosimulation in the design of a novel multilevel weight loss maintenance program for overweight children. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010 Feb;18(Suppl 1):S91–98. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Huang TT, Drewnosksi A, Kumanyika S, Glass TA. A systems-oriented multilevel framework for addressing obesity in the 21st century. Prev Chronic Dis. 2009 Jul;6(3):A82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Glass TA, McAtee MJ. Behavioral science at the crossroads in public health: extending horizons, envisioning the future. Soc Sci Med. 2006 Apr;62(7):1650–1671. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]