Abstract

Summary: The Ensembl database makes genomic features available via its Genome Browser. It is also possible to access the underlying data through a Perl API for advanced querying. We have developed a full-featured Ruby API to the Ensembl databases, providing the same functionality as the Perl interface with additional features. A single Ruby API is used to access different releases of the Ensembl databases and is also able to query multi-species databases.

Availability and Implementation: Most functionality of the API is provided using the ActiveRecord pattern. The library depends on introspection to make it release independent. The API is available through the Rubygem system and can be installed with the command gem install ruby-ensembl-api.

Contact: jan.aerts@esat.kuleuven.be

1 INTRODUCTION

The Ensembl (Flicek et al., 2010) and UCSC (Fujita et al., 2010) genome browsers are the first point of call for a large community of genetics and genomics researchers. Both provide a graphical interface for browsing the genomes of a large number of species, displaying the location of genes, polymorphisms, repeats and regulatory regions. Each database can also be accessed directly via SQL and provides an interface for simple querying of the data: BioMart for Ensembl (Haider et al., 2009) and the Table Browser for UCSC. In addition, the Ensembl team provides a Perl API for advanced scripted access to the data (Flicek et al., 2010).

In recent years, the Python and Ruby scripting languages have gained significant ground in the bioinformatics community (Aerts and Law, 2009; Cock et al., 2009; Goto et al., 2010, see e.g.), increasing the need for a programmable interface in these languages. In this article, we describe a second API to the Ensembl database, focusing on the Ruby programming community.

2 IMPLEMENTATION

The data available in the Ensembl Genome Browser is stored in a set of MySQL relational databases and to a certain extent normalized. Every table covers one specific conceptual class of objects, such as ‘genes’ or ‘transcripts’. The Ruby ActiveRecord library is used to map tuples within the Core and Variation tables to objects of a class, and delivers a full API with a limited amount of code.

As does the perl API, the Ruby library provides a Slice class which describes a region of the genome. Each class that defines a locus (e.g. gene, simple_feature, assembly_exception) includes the Sliceable mixin which provides additional methods such as returning the sequence of the object or its position. The Ruby and Perl Slice classes differ however significantly at the conceptual level. The slice for a feature (e.g. a gene) in the perl API is the complete seq_region this feature is located on, commonly the whole chromosome: e.g. ‘chromosome 13’ for the gene BRCA2. In contrast, the slice in the Ruby version is delimited by the boundaries of the feature: ‘chromosome:GRCh37:13:32889611:32973347:1’ for the same gene. As a result, methods such as overlaps?, contains? and within? are available for each object that implements Sliceable.

The Ruby API to Ensembl is not part of the BioRuby project, but might be linked to it as a plugin in the future.

3 FEATURES

The user provides the species name (e.g. ‘Homo sapiens’) and an optional release number to connect to the Ensembl database. It is not necessary to make the distinction between Core or Variation; the code will internally open connections to either if necessary. In addition and in contrast to the Perl API, only a single Ruby interface is necessary for every Ensembl release. The Ruby API is also able to work with Ensembl Genomes databases, where multiple species are stored within the same database (e.g. bacterial, fungal and plant genomes; Kersey et al., 2010).

The Ruby Ensembl API provides—to our knowledge—the same functionality as the Perl API where concerning the Core and Variation databases. Class methods cover searching for records: every column in the table is available for querying by preceding it with find_by_. These class methods bypass the need for Adaptor objects as in the Perl API. Instance methods, on the other hand, work on records and for example provide access to specific data for a single column in a given row (e.g. my_gene.start). As each method call returns an object, different method calls can be chained together. To obtain the start position of the first transcript for a gene my_gene, the user can invoke my_gene.transcripts[0].start. Functionality that is not automatically covered by the ActiveRecord pattern but that is present in the Perl API is also provided. This includes but is not limited to converting genomic positions between different coordinate systems (e.g. between chromosome, scaffold and contig) and SNP effect prediction. In addition, the user can ask the API what types of object are related to each other, thus providing additional real-time documentation for every class in the API.

The library provides two binaries. The ensembl command takes a species and release number as argument and drops the user in an interactive Ruby session for quick querying of the Ensembl database without the need to write one-off scripts. In addition, the variation_effect_predictor script takes a file containing known or novel SNPs/indels and annotates this list with a consequence type (e.g. essential_splice_site, stop_gained).

Future efforts will focus on extending the API to the Compara and FunctionalGenomics databases which provide data for multi-species comparisons and for functional as well as regulatory information.

3.1 Example

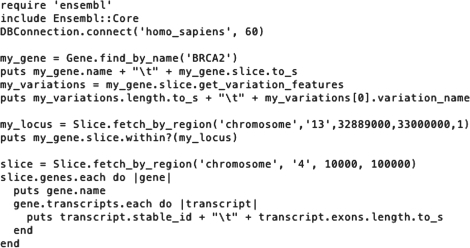

Figure 1 shows an example of using the Ruby Ensembl API. Lines 1 to 3 load the library and connect to the Core and Variation databases for human release 60. In lines 4 and 5, the BRCA2 gene is retrieved and gene name and location are printed. The #slice method creates a Slice object, which describes the locus itself and is serialized into a string. Lines 6 and 7 retrieve all variations within the gene and report on the total number of variations and the dbSNP accession of the first one. In lines 8 and 9, a locus is defined and the code checks if the BRCA2 gene is within that locus. Finally, in lines 10 to 16, a slice of the genome is selected directly. For every gene in this slice, the gene name in printed as well as the stable ID and number of exons for each transcript.

Fig. 1.

Example script using the Ruby Ensembl API.

4 CONCLUSION

The library described here provides the functionality needed to query the Ensembl database using the Ruby programming language. This API has several advantages compared to the Perl version, including a single API for all releases, terser code, a powerful interactive shell, a more useful implementation of the Slice concept and extensive introspection. The Ruby Ensembl API is also ideal for e.g. adding background information on candidate genes from the Ensembl database in applications geared at clinical geneticists (e.g. Annotate-It; Sifrim,A. et al., manuscript in preparation).

From a library maintainer's perspective, the metaprogramming and introspection capabilities of the Ruby language and the ActiveRecord module allow for providing full functionality and easy maintenance with minimal effort. They enable the Ruby API to be very flexible and by definition virtually insensitive to adding or removing data columns in tables.

The API is available through the Rubygem system and can be installed with the command gem install ruby-ensembl-api. Source code is at http://github.com/jandot/ruby-ensembl-api. Documentation and an extensive tutorial (with permission modified from the Perl API) is also available at the GitHub website.

ACKNOWLEDEGMENTS

J.A. initiated the project and wrote the Core code and overall framework. F.S. created the Variation API and adapted the code for Ensembl Genomes multi-species databases. Both contributed to the manuscript. We thank the European Bioinformatics Institute for hosting JA under the Geek For A Week program, and specifically Glenn Proctor and Andreas Kahari. We thank Marc Hoeppner for useful discussions and Alejandro Sifrim for his contribution to the variation consequence calculation.

Funding: Article processing charges are covered by SymBioSys II (grant number KUL PFV/10/016 SymBioSys).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Aerts J., Law A. An introduction to scripting in Ruby for biologists. BMC Bioinf. 2009;10:221. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cock P.J., et al. Biopython: freely available Python tools for computational molecular biology and bioinformatics. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1422–1423. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flicek P., et al. Ensembl 2011. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;39(Suppl. 1):D800–D806. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita P.A., et al. The UCSC Genome Browser database: update 2011. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq963. [Epub ahead of print, doi:10.1093/nar/gkq963; October 18, 2010] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto N., et al. BioRuby: bioinformatics software for the Ruby programming language. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2617–2619. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haider S., et al. BioMart Central Portal - unified access to biological data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:W23–W27. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kersey P.J., et al. Ensembl Genomes: extending Ensembl across the taxonomic space. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D563–D569. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]