Abstract

Purpose

Tumor progression correlates with the induction of a dense supply with blood vessels and formation of peritumoral lymphatics. Hem- and lymphangiogenesis are potently regulated by members of the Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) family. Previous studies have indicated up-regulation of VEGF-A and −C in progressed neuroblastoma (NB). However, quantification was performed by semiquantitative methods, or patients were studied, who had received radio- or chemotherapy.

Experimental Design

We have analyzed primary NB from 49 patients by real-time RT-PCR and quantified VEGF-A, −C and −D and VEGF receptors (R)-1, −2, −3, as well as the soluble form of VEGFR-2 (sVEGFR-2), which has recently been characterized as an endogenous inhibitor of lymphangiogenesis. None of the patients had received radio- or chemotherapy before tumor resection.

Results

We did not observe up-regulation of VEGF-A, −C and −D in metastatic NB, but found significant down-regulation of the lymphangiogenesis inhibitor sVEGFR-2 in metastatic stages 3, 4 and 4s. In stage 4 NB there were tendencies for the up-regulation of VEGF-A and −D and the down-regulation of the hem/lymphangiogenesis inhibitors VEGFR-1 and sVEGFR-2 in MYCN-amplified tumors. Similarly, MYCN-transfection of the NB cell-line SH-EP induced up-regulation of VEGF-A and −D and the switching-off of sVEGFR-2.

Conclusion

We provide evidence for the down-regulation of the lymphangiogenesis inhibitor sVEGFR-2 in metastatic NB stages, which may promote lymphogenic metastases. Down-regulation of hem- and lymphangiogenesis inhibitors VEGFR-1 and sVEGFR-2, and up-regulation of angiogenic activators VEGF-A and VEGF-D in MYCN-amplified stage 4 NB supports the high impact of this oncogene on NB progression.

Keywords: Neuroblastoma, metastasis, vascularization, VEGFR-1, sVEGFR-2, VEGF-D, MYCN

Introduction

A key step in the malignant progression of tumors in adults is the angiogenic switch, the induction of blood vessels by hypoxic tumors (1, 2). Additionally, tumor-induced lymphangiogenesis correlates frequently with the dissemination of tumor cells via lymphatic vessels. Hem- and lymphangiogenesis are robustly regulated by members of the Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) family: VEGF-A being (predominantly) hemangiogenic, and VEGF-C and −D lymphangiogenic (3–5). In adults, hem- and lymphangiogenesis are associated with progressed tumor stages. Tumors of infants present a much broader spectrum of heterogeneity than those of adults, especially exemplified by the biology of neuroblastoma.

Neuroblastoma (NB) is derived from sympatho-adrenal progenitor cells that migrate from the neural crest into target regions of the embryo. NB is mostly located along the sympathetic trunk ganglia and in the adrenal medulla. The spectrum of the disease ranges from complete spontaneous regression, which can be immediately observed in the ‘special’ NB stage 4s - but may as well occur in early stages - to malignant progression into stage 4, with 5-year survival rates of less than 30%. Partial differentiation into ganglioneuroblastma is another developmental pathway (6). The most critical molecular predictor for the behavior and treatment of NB is the MYCN protooncogene. Amplification (up to 150x) of MYCN characterizes highly aggressive tumors and poor outcome despite intensive treatment (7). Staging of NB is performed according to the International Neuroblastoma Staging System (INSS). Stage 1 and 2 NBs are localized tumors, which have grown across the midline in stage 2. Metastasis to regional and systemic lymph nodes characterizes stages 3 and 4, respectively (8), indicating active interactions with the lymphovascular system. Additionally, high vascularity is characteristic for the progressed tumor stages (9, 10), indicating an influence of blood capillaries on NB cell behavior and their typical dissemination into bone marrow.

The impact of VEGFs on tumor hemangiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis has been shown in numerous studies of adult tumors, and several investigations in recent years have postulated a similar function for VEGFs in NB. Blood vessels and lymphatics are present in NB, and expression of the ligands VEGF-A, −C and −D as well as their receptors has been found (11–13). Increased expression of VEGF-A has been described in NB stages 3 and 4 (14), while VEGF-C has been identified as a risk factor in stage 4 NB (15). High levels of VEGF-A have been found in stage 4 NB, but neither VEGF-A nor VEGF-C correlated with age, MYCN copy number or lymph node metastasis (16). Moreover, it has been observed that MYCN amplification correlates strongly with dense vascular supply, tumor dissemination and poor survival (9). According to Kang et al. (17), MYCN up-regulates VEGF-A, and MYCN amplified NBs exert changes in the vascular pattern of the chick chorioallantoic membrane (18). Some authors have suggested anti-VEGF-A treatment with bevacizumab for high-risk NB (19). There are, however, results that challenge the unequivocal functions of VEGFs for the progression of NB. Vessel density was not predictive of survival in a cohort of NB patients (20). Anti-VEGF-A treatment did not result in any reduction of experimental NB growth in mice (21, 22), and some authors have emphasized the heterogeneity of angiogenesis stimulators and inhibitors in NB (23, 24). We have therefore reinvestigated the expression of VEGFs and their receptors in a cohort of 49 NB patients and in 24 NB cell lines. Additionally, we studied the impact of MYCN on the expression of VEGFs in primary NB and in NB cell lines. In contrast to previous studies we did not observe a positive correlation between tumor progression and the expression of VEGF-A and −C. Of note, we found significant down-regulation of the VEGF-C inhibitor sVEGFR-2 in the progressed stages 3, 4 and 4s, indicating a positive correlation between lymphangiogenesis and lymph node metastases. Additionally, we observed increased expression of VEGF-A and −D, as well as reduced expression of the inhibitors VEGFR-1 and sVEGFR-2 in MYCN-amplified stage 4 NB, a finding, which was recapitulated by MYCN-transfected SH-EP cells, but not generally observed in MYCN-amplified NB cell lines. Our data show that up-regulation of the hem- and lymphangiogenesis activators VEGF-A and VEGF-D and down-regulation of the hem- and lymphangiogenesis inhibitors VEGFR-1 and sVEGFR-2 act in concert during NB progression. Cell lines do not necessarily reflect the in vivo situation. In addition to the down-regulation of hemangiogenesis inhibitors (25, 26), down-regulation of lymphangiogenesis inhibitors is an alternative mechanism for the increased vascularization and metastasis formation of progressed NB.

Materials and Methods

Primary neuroblastomas

RNA samples of 50 primary, untreated tumors, were kindly provided by the Tumorbank of the German Neuroblastoma Studies Group, Drs. F. Berthold, B. Hero and J. Theissen, Children’s Hospital University Cologne, Cologne, Germany. Tumor specimens were prepared according to a standard protocol. Two representative areas were dissected out of the tumor and each was divided into four parts. One part was fixed in fomalin and three parts were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. Snap frozen specimens were used in our study. RNA was isolated with Trizol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The samples were tested with Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies, Böblingen, Germany). One sample failed the test and was discarded. The remaining 49 samples were allocated to the NB stages as follows: stage 1 (n=8), stage 2 (n=6), stage 3 (n=5; 2 were MYCN-amplified), stage 4 (n=20; 10 were MYCN-amplified), stage 4s (n=10; 1 was MYCN-amplified).

Cell culture

All 24 human NB cells lines (Table 1; and see (27) for a well-arranged review of 113 NB cell lines) were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2 atmosphere using RPMI 1640 medium (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Biochrome, Berlin, Germany) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen). The NB cell line SH-EP was stably transfected to overexpress the MYCN oncogene as described before (28). The transfected cell line was designated WAC2. Transfected cells were continuously selected by adding G418 (100 μg/ml; Invitrogen) to the medium. PC-3 human prostate carcinoma cells were purchased from DSMZ (Braunschweig, Germany), and used as reference for VEGF-A and −C ELISAs.

Table 1.

Human neuroblastoma cell lines: references and sources

| Name | Reference | Commercial source |

|---|---|---|

| CHLA 20 | Keshelava, N., Seeger, R. C., Groshen, S., and Reynolds, C. P. Drug resistance patterns of human neuroblastoma cell lines derived from patients at different phases of therapy. Cancer Res., 58: 5396 – 5405, 1998. | |

| CHLA 90 | Keshelava, N., Seeger, R. C., Groshen, S., and Reynolds, C. P. Drug resistance patterns of human neuroblastoma cell lines derived from patients at different phases of therapy. Cancer Res., 58: 5396 – 5405, 1998. | |

| CHP 100 | Schlesinger, H. R., Gerson, J. M., Moorhead, P. S., Maguire, H., and Hummeler, K. Establishment and Characterization of human Neuroblastoma Cell Lines, Cancer Research. 36: 3094–3100, 1976 | |

| CHP 134 | Schlesinger, H. R., Gerson, J. M., Moorhead, P. S., Maguire, H., and Hummeler, K. Establishment and Characterization of human Neuroblastoma Cell Lines, Cancer Research. 36: 3094–3100, 1976 | RIKEN |

| Gi Men | Cornaglia-Ferraris, P., Ponsoni, M., Montaldo, P., Mariottini, G., Donti, E., Di Martino, D., and Tonini, G. A new human highly tumoigenic neuroblastoma cell line with undetectable expression of N-myc, Pediatric Research. 27: 1–6, 1990. | CLS |

| IMR 32 | Tumilowicz, J. J., Nichols, W. W., Cholon, J. J., and Greene, A. E. Definition of a Continuous Human Cell Line Derived from Neuroblastoma, Cancer Research. 30: 2110- 2118, 1970. | CLS RIKEN |

| IMR5 | 7. Tumilowicz, J.J., Nichols, W.W., Cholon, J.J., and Greene, A.E. (1979). Cancer Res. 30:2110–2118. | |

| Kelly | Schwab, M., Alitalo, K., Klempnauer, K., Varmus, H., Bishop, J., Gilbert, F., Brodeur, G., Goldstein, M., and Trent, J. Amplified DNA with limited homology to myc cellular oncogene is shared by human neuroblastoma cell lines and a neuroblastoma tumor., Nature. 305: 245- 248, 1983. | DSMZ |

| Lan 1 | Seeger, R. C., Rayner, S. A., Banerjee, A., Chung, H., Laug, W. E., Neustein, H. B., and Benedict, W. F. Morphology, Growth, Chromosomal Pattern, and Fibrinolytic Activity of Two New Human Neuroblastoma Cell Lines, Cancer Research. 37: 1364–1371, 1977. | RIKEN |

| Lan 2 | Seeger, R. C., Rayner, S. A., Banerjee, A., Chung, H., Laug, W. E., Neustein, H. B., and Benedict, W. F. Morphology, Growth, Chromosomal Pattern, and Fibrinolytic Activity of Two New Human Neuroblastoma Cell Lines, Cancer Research. 37: 1364–1371, 1977. | RIKEN |

| Lan 5 | Dr.Seeger, Robert C. Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, 4546 W. Sunset Boulevard, Mailstop #57, Smith Research Tower #509, Los Angeles, CA 90027 USA | RIKEN |

| Lan 6 | Wada, R. K., Seeger, R. C., Brodeur, G. M., Einhorn, P. A., Rayner, S. A., Tomayko, M. M., and Reynolds, C. P. Human Neuroblastoma Cell Lines that Express N- myc without Gene Amplification, Cancer. 72: 3346–3354, 1993. | |

| NB 69 | Brodeur, G. M. and Goldstein, M. N. Histochemical demonstration of an increase in acetylcholinesterase in established lines of human and mouse neuroblastomas by nerve growth factor, Cytobios. 16: 133–138, 1976. | RIKEN |

| NB-LS | Cohn, S., Salwen, H., Quasney, M., Ikegaki, N., Cowan, J., Herst, C., Kennett, R., Rosen, S., DiGiuseppe, J., and Brodeur, G. Prolonged N- myc protein half-life in a neuroblasoma cell line lacking N-myc amplification, Oncogene. 5: 1821–1827, 1990. | |

| NGP | Brodeur, G. M. and Goldstein, M. N. Histochemical demonstration of an increase in acetylcholinesterase in established lines of human and mouse neuroblastomas by nerve growth factor, Cytobios. 16: 133–138, 1976. | |

| NLF | Schwab, M., Alitalo, K., Klempnauer, K., Varmus, H., Bishop, J., Gilbert, F., Brodeur, G., Goldstein, M., and Trent, J. Amplified DNA with limited homology to myc cellular oncogene is shared by human neuroblastoma cell lines and a neuroblastoma tumor., Nature. 305: 245- 248, 1983. | |

| NMB | Brodeur, G. M., Sekhon, G. S., and Godstein, M. N. Chromosomal Aberrations in Human Neuroblastomas, Cancer. 40: 2256–2263, 1977. | |

| SH-EP | Ross, R. A., Spengler, B. A., and Biedler, J. L. Coordinate morphological and biochemical interconversion of human neuroblastoma cells. J. Nati. Cancer Inst., 77:741–749, 1983. | |

| SH-IN | Ross, R. A., Spengler, B. A., and Biedler, J. L. Coordinate morphological and biochemical interconversion of human neuroblastoma cells. J. Nati. Cancer Inst., 77:741–749, 1983. | |

| SH-SY5Y | Ross, R. A., Spengler, B. A., and Biedler, J. L. Coordinate morphological and biochemical interconversion of human neuroblastoma cells. J. Nati. Cancer Inst., 77:741–749, 1983. | CLS ATCC |

| SK-N-AS | Sugimoto T, et al. Determination of cell surface membrane antigens common to both human neuroblastoma and leukemia-lymphoma cell lines by a panel of 38 monoclonal antibodies. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 73: 51–57, 1984. | ATCC |

| SK-N-SH | Biedler, J. L., Helson, L., and Spengler, B. A. Morphology and growth, tumorigenicity, and cytogenetics of human neuroblastoma cells in continuous culture. Cancer Res., 33: 2643–2652, 1973. | ATCC RIKEN |

| SMS-Kan | Reynolds, C. P., Biedler, J. L., Spengler, B. A., Reynolds, D. A., Ross, R. A., Frenkel, E. P., and Smith, R. G. Characterization of Human Neuroblastoma Cell Lines Established Before and After Therapy, JNCI. 76: 375–387, 1986. | |

| SMS-KCN | Reynolds, C. P., Biedler, J. L., Spengler, B. A., Reynolds, D. A., Ross, R. A., Frenkel, E. P., and Smith, R. G. Characterization of Human Neuroblastoma Cell Lines Established Before and After Therapy, JNCI. 76: 375–387, 1986. |

Sources:

ATCC: American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) P.O. Box 1549 Manassas, VA 20108, USA

CLS: Cell Lines Service, Justus-von-Liebig-Strasse 14,69214 Eppelheim, Germany

DSMZ: Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen GmbH, Inhoffenstraße 7 B, 38124 Braunschweig, GERMANY

RIKEN: Cell Bank, RIKEN BioResource Center 3-1-1 Koyadai, Tsukuba, Ibaraki, 305-0074, Japan

RNA isolation from cultured NB cells

Cells were rinsed twice with PBS and RNA was isolated directly from the culture plate using Trizol (Invitrogen) as recommended by the supplier. Quality of RNA samples was analyzed with NanoDrop spectrophotometer (NanoDrop products, Wilmington, DE) and ethidium bromide staining on agarose gels.

Real-time RT-PCR

We prepared cDNA from 2 μg total RNA using Omniscript reverse transcriptase (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Real-time PCR was performed with Opticon2 thermal cycler (MJ Research, Waltham, MA), using SYBR green JumpStart Taq ReadyMix (Sigma-Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany). Primers used are listed in Table 2. All primers were designed to produce fragments, which are spanning exon-intron boundaries, to exclude amplification of genomic DNA. The primers were also designed to detect all known splice variants of the respective gene of interest. For sVEGFR-2 the reverse primer recognizes the intron 13 motif, which is specific for the truncated transcript-variant of this secreted form of VEGFR-2 (29). The probe was measured against two different β-actin probes. Both measurements revealed significant down-regulation in metastatic NB (only one is shown in Fig. 1G).

Table 2.

Primers used for real-time RT-PCR

| Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|

| β-Actin1 fwd | 5′- GCATCCCCCAAAGTTCACAA -3′ |

| β-Actin1 rev | 5′- AGGACTGGGCCATTCTCCTT -3′ |

| β-Actin2 fwd | 5′- TCGTGCGTGACATTAAGGAG -3′ |

| β-Actin2 rev | 5′- CCATCTCTTGCTCGAAGTCC -3′ |

| VEGF-A fwd | 5′- AAGGAGGAGGGCAGAATCAT -3′ |

| VEGF-A rev | 5′- GCAGTAGCTGCGCTGATAGA -3′ |

| VEGF-C fwd | 5′- TGAACACCAGCACGAGCTAC -3′ |

| VEGF-C rev | 5′- GCCTTGAGAGAGAGGCACTG -3′ |

| VEGF-D fwd | 5′- TGGAACAGAAGACCACTCTCATCT -3′ |

| VEGF-D rev | 5′- GCAACGATCTTCGTCAAACATC-3′ |

| VEGFR-1 fwd | 5′- TCCAAGAAGTGACACCGAGA -3′ |

| VEGFR-1 rev | 5′- TTGTGGGCTAGGAAACAAGG -3′ |

| VEGFR-2 fwd | 5′- GACTTGGCCTCGGTCATTTA -3′ |

| VEGFR-2 rev | 5′- ACACGACTCCATGTTGGTCA -3′ |

| VEGFR-3 fwd | 5′- CAGCTCCTACGTGTTCGTGA -3′ |

| VEGFR-3 rev | 5′- GTTGACCAAGAGCGTGTCAG -3′ |

| sVEGFR-2 fwd | 5′- GCCTTGCTCAAGACAGGAAG -3′ |

| sVEGFR-2 rev | 5′- CAACTGCCTCTGCACAATGA -3′ |

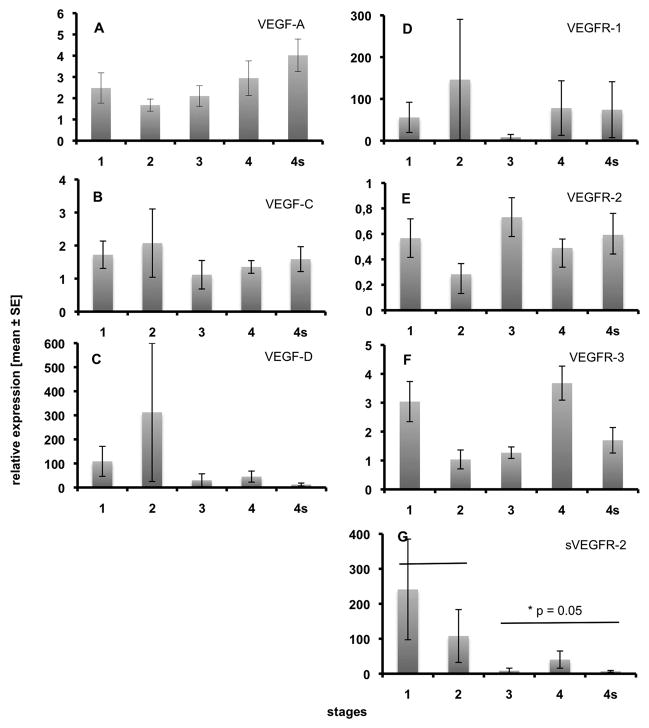

Fig. 1.

Expression of VEGF ligands and receptors in 49 primary NB specimens as measured by real-time RT-PCR. A) VEGF-A, B) VEGF-C, C) VEGF-D, D) VEGFR-1, E) VEGFR-2, F) VEGFR-3, G) sVEGFR-2. Note statistically significant down-regulation of sVEGFR-2 in metastatic stages 3, 4 and 4s. None of the other molecules exhibits any obvious stage-specific regulation. Relative expression ± standard error are shown.

Sandwich ELISA

Sandwich ELISA was performed to measure VEGF-A and VEGF-C protein in cell culture supernatants of NB cell lines SH-EP and SH-IN in comparison with the human prostate carcinoma PC-3 cell line, with methods and tools described recently (30, 31). Cells were cultured for four days in RPMI 1640 medium. Supernatant was collected and compared to control (day 0) supernatant of PC-3 cells. Experiments were performed twice.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS-Software v. 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Primary neuroblastomas

We have studied primary NB from a cohort of 49 patients by real-time RT-PCR using SYBR green and the ΔΔCt method for relative quantification of VEGFs and VEGF receptors. None of the patients had received radio- or chemotherapy before tumor resection. Staging of NB was performed according to the International Neuroblastoma Staging System (INSS) and the specimens were allocated to the stages as follows: stage 1 (n=8), stage 2 (n=6), stage 3 (n=5; 2 of which were MYCN-amplified), stage 4 (n=20; 10 of which were MYCN-amplified), stage 4s (n=10; 1 of which was MYCN-amplified). We studied expression of VEGF-A, VEGF-C, VEGF-D, VEGFR-1 (FLT1), VEGFR-2 (KDR) and VEGFR-3 (FLT4), as well as a soluble splice variant of VEGFR-2 (sVEGFR-2), which has very recently been shown to act as an endogenous inhibitor of lymphangiogenesis (29). Expression of all VEGFs and their receptors varied greatly. We did not observed statistically significant difference between loco-regional tumors (stages 1 and 2) and metastasized NB (stages 3, 4 and 4s) for VEGF-A, −C and −D (Fig. 1A-C). Also, VEGFR-1, −2 and −3 were not significantly regulated (Fig. 1D-F), however, we observed significant down-regulation of the lymphangiogenesis inhibitor sVEGFR-2 in metastatic stages 3, 4 and 4s (Fig. 1G).

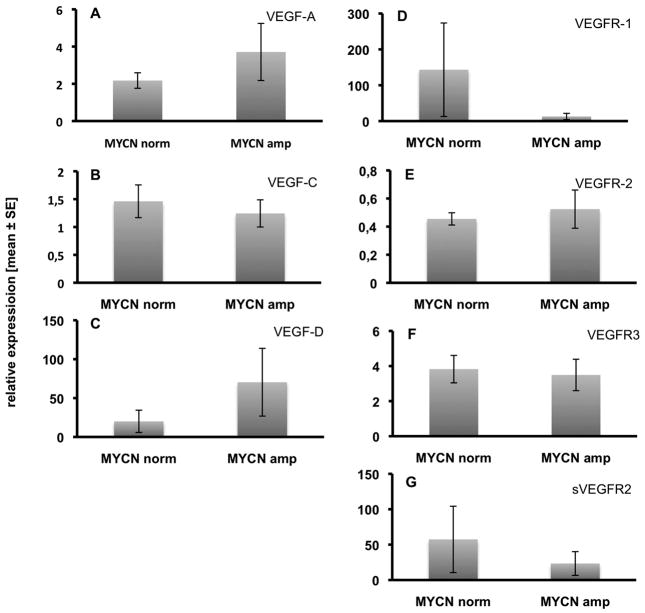

We have then compared the expression levels of VEGFs in MYCN-amplified stage 4 NB with those that had normal MYCN status (each 10 per group). We did not find statistically significant differences, however, there were tendencies for an increase in the expression of VEGF-A and −D and for down-regulation of VEGFR-1 and sVEGFR-2 in MYCN-amplified stage 4 tumors (Fig. 2). This suggest increased hemangiogenic and lymphangiogenic potential.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of the expression of VEGF ligands and receptors in stage 4 NB with normal vs. amplified MYCN expression. A) VEGF-A, B) VEGF-C, C) VEGF-D, D) VEGFR-1, E) VEGFR-2, F) VEGFR-3, G) sVEGFR-2. There are no statistically significant differences, but tendencies for the up-regulation of VEGF-A and VEGF-D, and the down-regulation of VEGFR-1 and sVEGFR-2 in MYCN-amplified tumors. Relative expression ± standard error are shown.

NB cell lines

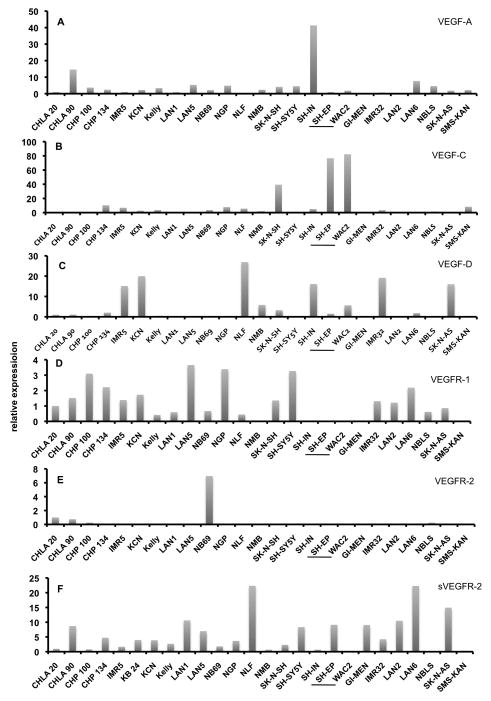

In a further approach, we isolated RNA from 24 human NB cell lines and studied expression of VEGF-A, VEGF-C, VEGF-D, VEGFR-1, VEGFR-2 and VEGFR-3 and sVEGFR-2. Relative expression in NB cell line CHLA20 was used as reference and was set as 1 (Fig. 3). Only a few NB cell lines showed robust expression of VEGF-A. We observed 15-fold expression in CHLA90 and almost 40-fold expression in SH-IN (Fig. 3A). To analyze the biological significance of this observation, we inoculated SH-IN (high VEGF-A), GI-MEN and CHP134 (low VEGF-A) on the chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) of chick embryos. The three cell lines produced solid tumors after 7 days, but only SH-IN were densely vascularized, whereas GI-MEN and CHP134 produced almost avascular tumors (data not shown). VEGF-C was highly expressed in SK-N-SH and SH-EP (Fig. 3B), and VEGF-D was high in IMR5, KCN, NLF, SH-IN, IMR32 and SK-N-AS (Fig. 3C). Expression of VEGF receptors was low, and for VEGFR-3 almost undetectable (data not shown). We found very weak expression of VEGFR-1 in various NB cell lines (Fig. 3D), elevated expression of VEGFR-2 only in NB69 (Fig. 3E), but considerable expression of sVEGFR-2 in a number of cell lines, most prominently in NLF, LAN6, SK-N-AS, LAN1 and LAN2 (Fig. 3F). For two cell lines, SH-EP and SH-IN, we measured VEGF-A and VEGF-C at protein level with sandwich ELISA (Table 3). The data show that RNA and protein expression correlate very well, e.g. SH-IN, which have the highest VEGF-A mRNA expression secret high amounts of VEGF-A (2005 pg/ml), while VEGF-C protein is not measurable (compare to Fig. 3A,B). SH-EP secret VEGF-C (140 pg/ml), which is comparable to the prostate carcinoma cell line PC-3, and have considerably high RNA levels of VEGF-C mRNA.

Fig. 3.

Expression of VEGF ligands and receptors in 24 NB cell lines as measured by real-time RT-PCR. A) VEGF-A, B) VEGF-C, C) VEGF-D, D) VEGFR-1, E) VEGFR-2, F) sVEGFR-2. Data for VEGFR-3 are not shown, because this receptor was almost undetectable. Expression of CHLA20 cells was used as reference and set as 1. Note that WAC2 are stably MYCN-transfected SH-EP cells. There is up-regulation of VEGF-A and VEGF-D, and a switch-off of sVEGFR-2 in WAC2.

Table 3. Concentration (pg/ml) of VEGF-A and VEGF-C in supernatants of two neuroblastoma cell lines and PC-3 cells measured by sandwich ELISA.

The VEGF-A ELISA measures total VEGF-A and the VEGF-C ELISA detects the fully processed form of VEGF-C. Indicated are the mean values of two measurements. n.d.= not detectable (detection limit is appr. 60 pg/ml).

| Cell type | VEGF-A (pg/ml) | VEGF-C (pg/ml) |

|---|---|---|

| PC-3 (day 0) | n.d. | n.d. |

| PC-3 (day 4) | 146 | 172 |

| SH-EP | 192 | 140 |

| SH-IN | 2005 | n.d. |

It has been shown that MYCN inhibition by siRNA blocks VEGF-A secretion in MYCN-amplified IMR-32 cells (17). To test the effects of MYCN, we performed stable overexpression of MYCN in SH-EP, which have regular MYCN expression. The stably transfected cell line was designated WAC2, because the cells form colonies in soft agar (28). For VEGF-C, VEGFR-1, −2 and −3, expression in WAC2 was not different from that of the parental cell line SH-EP (Fig. 3B,D,E), however, VEGF-A and −D were up-regulated, and sVEGFR-2 was significantly down-regulated, so that it was not detectable any more in WAC2 (Fig. 3A,C,F). Notably, these effects may promote hemangiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis.

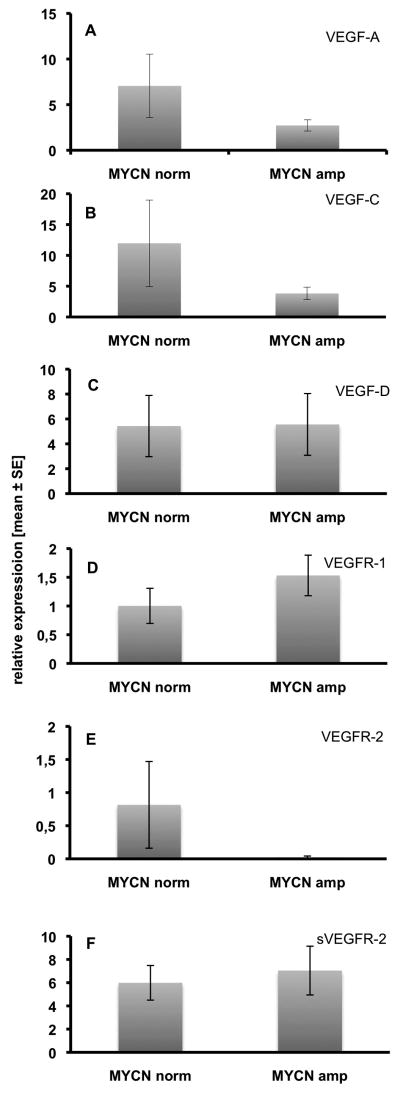

According to published data, we also divided the 24 cell lines into two groups with normal vs. amplified MYCN expression and compared VEGF ligands and receptors (Fig. 4A-F). However, the results did not reflect any of the results measured in primary tumors, and underline that in vitro data have to be interpreted with great caution.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of the expression of VEGF ligands and receptors in 24 NB cell lines, sorted by their MYCN copy numbers (normal vs. amplified). A) VEGF-A, B) VEGF-C, C) VEGF-D, D) VEGFR-1, E) VEGFR-2, F) sVEGFR-2. There are no statistically significant differences, but tendencies for the down-regulation of VEGF-A, VEGF-C and VEGFR-2 in MYCN-amplified cell lines. However, this does not reflect our observations on primary NBs. Relative expression ± standard error are shown.

In summary, our data show that there is significant down-regulation of the lymphangiogenesis inhibitor sVEGFR-2 in metastatic NB as compared to localized NB stages 1 and 2. In MYCN-amplified stage 4 NB there is a tendency for the up-regulation of VEGF-A and −D, and down-regulation of VEGFR-1 and sVEGFR-2. Similar results can be observed in MYCN-transfected SH-EP cells. Together, up-regulation of hem- and lymphangiogenesis activators (VEGF-A and VEGF-D, respectively) and down-regulation of hem- and lymphangiogenesis inhibitors (VEGFR-1 and sVEGFR-2, respectively) may represent cooperative mechanisms during NB progression.

Discussion

VEGFs and NB vascularity

Quite some time ago, the importance of VEGF-A for hemangiogenesis and of VEGF-C and VEGF-D for lymphangiogenesis has been revealed (32–39). The essential role of VEGF-A in tumor hemangiogenesis is the basis for its targeting in anti-angiogenesis therapy (40). Tumor-induced lymphangiogenesis by VEGF-C and −D, and the positive correlation with the lymphogenic spread of tumor cells, has been described several years ago (41–44). Dense vascularization is a key feature of malignant tumor progression (1). This holds true for numerous tumor types in the adult, and has also been observed in tumors of infants, such as neuroblastoma (NB).

A vascular index of NB specimens (total number of vessels per mm2) has been measured in a cohort of 50 patients, and it was found that an index > 4 correlates strongly with widely disseminated disease, poor survival and MYCN amplification (9). A similar correlation with angiogenic (integrin αvβ3- and αvβ5-positive) endothelium has been described by Erdreich-Epstein et al. (45). A number of studies have revealed a positive correlation between NB progression and VEGFs, however, most of these studies were performed in vitro or in experimental tumors in nude mice, and there are only few data available on primary tumors. Among these, Pavlakovic et al. (46) have shown that VEGF-A levels are not increased (rather slightly reduced) in the serum of NB patients as compared with healthy controls. In contrast, elevated levels of VEGF-A, −B and −C have been measured by RT-PCR (quantified by densitometric analysis, normalized against GAPDH expression in a cohort of 37 patients) in NB stages 3 and 4 as compared to stages 1, 2 and 4s (11). By means of ELISA, VEGF-A protein has been measured in 5 primary NB and revealed values of 150pg - 2400pg per g total protein with the highest value in a stage 2 NB (13). Fakhari et al. (14) studied expression of VEGF-A, −B and −C in 37 NB patients, who had routine radiologic and medical program before surgery, by real-time RT-PCR, and VEGF-A in serum by ELISA. They observed significant up-regulation of VEGF-A and −C in stages 3 and 4, as compared to adrenal control tissue, and elevated serum VEGF-A levels only in stage 3. Additionally they found up-regulation of VEGFR-1 and −2 in stage 3 NB. In sum, the published data do not yet provide a consistent picture of VEGFs in NB and we have therefore reinvestigated their expression in a cohort of 49 untreated, primary tumors and in 24 cell lines by real-time RT-PCR. Thereby we also included the soluble splice variant of VEGFR-2 (sVEGFR-2), an endogenous inhibitor of lymphangiogenesis (29), and studied the impact of MYCN on the respective expression patterns.

Regulation of hem- and lymphangiogenesis in NB

In contrast to previous studies, we have not detected elevated expression of VEGF-A and −C in stage 3 and 4 NB. In fact, there is no significant difference between localized stages 1 and 2 and the metastatic stages 3, 4 and 4s as concerns the expression of VEGF-A, −C and −D. VEGFR-1 is expressed at almost equal amounts in all stages, and also VEGFR-2 and −3 are detectable in all stages. A significant difference between localized and metastatic stages is found for sVEGFR-2, a secreted endogenous inhibitor of lymphangiogenesis (29). This inhibitor is highly expressed in stages 1 and 2, and barely detectable in stages 3, 4 and 4s. Since the regulation of lymphangiogenesis by tumors has an influence on their metastatic behavior (3), our data for the first time indicate that down-regulation of an inhibitor of lymphangiogenesis may expedite the formation of lymph node metastases. NB stages 3, 4 and 4s are characterized by the spread of tumor cells to local, distant and dermal lymph nodes, respectively. However, we have to be aware that our measurements performed at RNA level do not necessarily reflect the amount of secreted protein. Down-regulation of sVEGFR-2 may be enhanced by the MYCN oncogene, which is a critical clinical predictor for poor outcome.

In stage 4 NB, MYCN-amplification does not only down-regulate sVEGFR-2, but also the hemangiogenesis inhibitor VEGFR-1. At the same time, the hem- and lymphangiogenic factors VEGF-A and −D are up-regulated. Identical regulation patterns can be observed after MYCN-transfection of SH-EP cells. In these cells we even observed complete switching-off of sVEGFR-2 expression. Our data support the observation that MYCN-amplification promotes the progression of NB, and it obviously does so by both the up-regulation of activators and the down-regulation of inhibitors. Down-regulation of other inhibitors of hemangiogenesis in NB has been described previously (25, 26).

The concept of high vascularity of progressed tumours has been challenged recently, as a number of data have pointed to a more aggressive behavior and the up-regulation of genes associated with poor survival in avascular glioblastomas (47) and hypoxic neuroblastoma (48). In mice, the inhibition of tumor angiogenesis either by targeting the VEGF-A or the VEGFR/PDGFR kinase pathways have induced progression to greater malignancy and increased invasiveness, and decreases overall survival (49, 50). However, our observations in general support the classical view, although differences in the expression of angiogenic factors may not become immediately evident by comparing tumor stages. The proportion between pro- and anti-angiogenic factors has to be taken into account, as well as the fact that tumor cell lines do not necessarily reflect the in vivo behavior in the human.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mrs. S. Schwoch, Mrs. Ch. Zelent and Mr. B. Manshausen for their excellent technical assistance and Drs. Frank Berthold, Barbara Hero and Jessica Theissen of the German Neuroblastoma Studies Group, Children’s Hospital University Cologne, Cologne, Germany, for providing tumour samples and data. We are grateful to Dr. L. Schweigerer for leaving us the NB cell lines.

References

- 1.Folkman J. Tumor angiogenesis. Adv Cancer Res. 1985;43:175–203. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60946-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Naumov GN, Akslen LA, Folkman J. Role of angiogenesis in human tumor dormancy: animal models of the angiogenic switch. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:1779–87. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.16.3018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Achen MG, Stacker SA. Molecular control of lymphatic metastasis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1131:225–34. doi: 10.1196/annals.1413.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan A. Antiangiogenic therapy for metastatic breast cancer: current status and future directions. Drugs. 2009;69:167–81. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200969020-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shojaei F, Ferrara N. Antiangiogenesis to treat cancer and intraocular neovascular disorders. Lab Invest. 2007;87:227–30. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maris JM, Hogarty MD, Bagatell R, Cohn SL. Neuroblastoma. Lancet. 2007;369:2106–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60983-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Westermann F, Schwab M. Genetic parameters of neuroblastomas. Cancer Lett. 2002;184:127–47. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(02)00199-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brodeur GM, Pritchard J, Berthold F, et al. Revisions of the international criteria for neuroblastoma diagnosis, staging, and response to treatment. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:1466–77. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.8.1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meitar D, Crawford SE, Rademaker AW, Cohn SL. Tumor angiogenesis correlates with metastatic disease, N-myc amplification, and poor outcome in human neuroblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:405–14. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.2.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rossler J, Taylor M, Geoerger B, et al. Angiogenesis as a target in neuroblastoma. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:1645–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eggert A, Ikegaki N, Kwiatkowski J, Zhao H, Brodeur GM, Himelstein BP. High-level expression of angiogenic factors is associated with advanced tumor stage in human neuroblastomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:1900–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lagodny J, Juttner E, Kayser G, Niemeyer CM, Rossler J. Lymphangiogenesis and its regulation in human neuroblastoma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;352:571–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.11.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meister B, Grunebach F, Bautz F, et al. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptors in human neuroblastoma. Eur J Cancer. 1999;35:445–9. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(98)00387-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fakhari M, Pullirsch D, Paya K, Abraham D, Hofbauer R, Aharinejad S. Upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor receptors is associated with advanced neuroblastoma. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37:582–7. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2002.31614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nowicki M, Konwerska A, Ostalska-Nowicka D, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-C - a potent risk factor in children diagnosed with stadium 4 neuroblastoma. Folia Histochem Cytobiol. 2008;46:493–9. doi: 10.2478/v10042-008-0067-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Komuro H, Kaneko S, Kaneko M, Nakanishi Y. Expression of angiogenic factors and tumor progression in human neuroblastoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2001;127:739–43. doi: 10.1007/s004320100293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kang J, Rychahou PG, Ishola TA, Mourot JM, Evers BM, Chung DH. N-myc is a novel regulator of PI3K-mediated VEGF expression in neuroblastoma. Oncogene. 2008;27:3999–4007. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ribatti D, Raffaghello L, Pastorino F, et al. In vivo angiogenic activity of neuroblastoma correlates with MYCN oncogene overexpression. Int J Cancer. 2002;102:351–4. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Segerstrom L, Fuchs D, Backman U, Holmquist K, Christofferson R, Azarbayjani F. The anti-VEGF antibody bevacizumab potently reduces the growth rate of high-risk neuroblastoma xenografts. Pediatr Res. 2006;60:576–81. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000242494.94000.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Canete A, Navarro S, Bermudez J, Pellin A, Castel V, Llombart-Bosch A. Angiogenesis in neuroblastoma: relationship to survival and other prognostic factors in a cohort of neuroblastoma patients. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:27–34. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim E, Moore J, Huang J, et al. All angiogenesis is not the same: Distinct patterns of response to antiangiogenic therapy in experimental neuroblastoma and Wilms tumor. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36:287–90. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2001.20691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zaghloul N, Hernandez SL, Bae JO, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor blockade rapidly elicits alternative proangiogenic pathways in neuroblastoma. Int J Oncol. 2009;34:401–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chlenski A, Liu S, Cohn SL. The regulation of angiogenesis in neuroblastoma. Cancer Lett. 2003;197:47–52. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(03)00082-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shusterman S, Maris JM. Prospects for therapeutic inhibition of neuroblastoma angiogenesis. Cancer Lett. 2005;228:171–9. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Breit S, Ashman K, Wilting J, et al. The N-myc oncogene in human neuroblastoma cells: down-regulation of an angiogenesis inhibitor identified as activin A. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4596–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hatzi E, Murphy C, Zoephel A, et al. N-myc oncogene overexpression down-regulates IL-6; evidence that IL-6 inhibits angiogenesis and suppresses neuroblastoma tumor growth. Oncogene. 2002;21:3552–61. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thiele C. Neuroblastoma Cell Lines. In: Masters J, editor. Human Cell Culture. Lancaster, UK: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1998. pp. 21–53. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schweigerer L, Breit S, Wenzel A, Tsunamoto K, Ludwig R, Schwab M. Augmented MYCN expression advances the malignant phenotype of human neuroblastoma cells: evidence for induction of autocrine growth factor activity. Cancer Res. 1990;50:4411–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Albuquerque RJ, Hayashi T, Cho WG, et al. Alternatively spliced vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 is an essential endogenous inhibitor of lymphatic vessel growth. Nat Med. 2009;15:1023–30. doi: 10.1038/nm.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bando H, Brokelmann M, Toi M, et al. Immunodetection and quantification of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-3 in human malignant tumor tissues. Int J Cancer. 2004;111:184–91. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weich HA, Bando H, Brokelmann M, et al. Quantification of vascular endothelial growth factor-C (VEGF-C) by a novel ELISA. J Immunol Methods. 2004;285:145–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2003.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Achen MG, Jeltsch M, Kukk E, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor D (VEGF-D) is a ligand for the tyrosine kinases VEGF receptor 2 (Flk1) and VEGF receptor 3 (Flt4) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:548–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.2.548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jeltsch M, Kaipainen A, Joukov V, et al. Hyperplasia of lymphatic vessels in VEGF-C transgenic mice. Science. 1997;276:1423–5. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5317.1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Joukov V, Pajusola K, Kaipainen A, et al. A novel vascular endothelial growth factor, VEGF-C, is a ligand for the Flt4 (VEGFR-3) and KDR (VEGFR-2) receptor tyrosine kinases. EMBO J. 1996;15:290–98. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leung DW, Cachianes G, Kuang WJ, Goeddel DV, Ferrara N. Vascular endothelial growth factor is a secreted angiogenic mitogen. Science. 1989;246:1306–9. doi: 10.1126/science.2479986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Millauer B, Wizigmann-Voos S, Schnurch H, et al. High affinity VEGF binding and developmental expression suggest Flk-1 as a major regulator of vasculogenesis and angiogenesis. Cell. 1993;72:835–46. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90573-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oh SJ, Jeltsch MM, Birkenhager R, et al. VEGF and VEGF-C: specific induction of angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis in the differentiated avian chorioallantoic membrane. Dev Biol. 1997;188:96–109. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Terman BI, Dougher-Vermazen M, Carrion ME, et al. Identification of the KDR tyrosine kinase as a receptor for vascular endothelial cell growth factor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;187:1579–86. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)90483-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilting J, Christ B, Weich HA. The effects of growth factors on the day 13 chorioallantoic membrane (CAM): a study of VEGF165 and PDGF-BB. Anat Embryol (Berl) 1992;186:251–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00174147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ferrara N. Vascular endothelial growth factor. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:789–91. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.179663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mandriota SJ, Jussila L, Jeltsch M, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor-C-mediated lymphangiogenesis promotes tumour metastasis. EMBO J. 2001;20:672–82. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.4.672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Papoutsi M, Siemeister G, Weindel K, et al. Active interaction of human A375 melanoma cells with the lymphatics in vivo. Histochem Cell Biol. 2000;114:373–85. doi: 10.1007/s004180000204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Skobe M, Hawighorst T, Jackson DG, et al. Induction of tumor lymphangiogenesis by VEGF-C promotes breast cancer metastasis. Nat Med. 2001;7:192–8. doi: 10.1038/84643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stacker SA, Caesar C, Baldwin ME, et al. VEGF-D promotes the metastatic spread of tumor cells via the lymphatics. Nat Med. 2001;7:186–91. doi: 10.1038/84635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Erdreich-Epstein A, Shimada H, Groshen S, et al. Integrins alpha(v)beta3 and alpha(v)beta5 are expressed by endothelium of high-risk neuroblastoma and their inhibition is associated with increased endogenous ceramide. Cancer Res. 2000;60:712–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pavlakovic H, Von Schutz V, Rossler J, Koscielniak E, Havers W, Schweigerer L. Quantification of angiogenesis stimulators in children with solid malignancies. Int J Cancer. 2001;92:756–60. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20010601)92:5<756::aid-ijc1253>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saidi A, Javerzat S, Bellahcene A, et al. Experimental anti-angiogenesis causes upregulation of genes associated with poor survival in glioblastoma. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:2187–98. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Poomthavorn P, Wong S, Higgins S, Werther G, Russo V. Activation of a prometastatic gene expression program in hypoxic neuroblastoma cells. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2009 doi: 10.1677/ERC-08-0340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ebos JM, Lee CR, Cruz-Munoz W, Bjarnason GA, Christensen JG, Kerbel RS. Accelerated metastasis after short-term treatment with a potent inhibitor of tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:232–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Paez-Ribes M, Allen E, Hudock J, et al. Antiangiogenic therapy elicits malignant progression of tumors to increased local invasion and distant metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:220–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]