Abstract

Polymer nanofibers exhibit properties that make them a favorable material for the development of tissue engineering scaffolds, filtration devices, sensors, and high strength lightweight materials. Electrospinning is a versatile method commonly used to manufacture polymer nanofibers. Collection of electrospun nanofibers across two parallel plates is a technique useful for creating nanofiber structures because it allows for the collection of linearly oriented individual nanofiber arrays and these arrays can be easily transferred to other substrates or structures. It is of importance to have some understanding of the capabilities of this collection method, such as the maximum length of fibers that can be collected across two parallel plates. The effect of different electrospinning parameters on maximum fiber length, average fiber diameter, diameter uniformity, and fiber quality was explored. It was shown that relatively long continuous polycaprolactone (PCL) nanofibers with average diameters from approximately 350 nm to 1 µm could be collected across parallel plates at lengths up to 35–50 cm. Experimental results lead to the hypothesis that even longer continuous nanofibers over 50 cm could be collected if the size of the parallel plates were increased. Extending the maximum fiber length that can be collected across parallel plates could expand the applications of electrospinning. Polymer solution concentration, plate size, and applied voltage were all shown to have varying effects on maximum fiber length, fiber diameter, and fiber uniformity.

Keywords: Electrospinning, Nanofiber, Polycaprolactone, Fabrication, Biomaterials, Nanomaterials

1. Introduction

The fabrication of polymer nanofibers by electrospinning has received much attention in recent years. Polymer nanofibers exhibit several properties that make them favorable for many applications. Nanofibers have a very large surface area to volume ratio, flexibility in surface functionalities, and mechanical properties superior to larger fibers [1–3]. Some potential applications for nanofibers include: tissue engineering scaffolds, filtration devices, sensors, materials development, and electronic applications [2–13].

In a typical electrospinning process, fibers are drawn from a solution or melt through a blunt needle by electrostatic forces. Electrospun nanofibers are most commonly collected as randomly oriented or parallel-aligned mats. Randomly oriented fiber mats result when a simple static collecting surface is used, and parallel-aligned mats have been collected by several methods [1]. Parallel aligned fiber mats are most commonly collected with a rotating mandrel used as the collecting device. Nanofibers can also be collected across an air gap between two parallel plates in a linear orientation [14]. The electric field produced between two parallel plates causes fibers to align perpendicular to the plates and stretch across them. Because individual nanofibers can be collected by this method, it expands the potential applications of electrospinning. Once collected these fibers may be further processed to form structures suitable for specific applications. When exploring the types of structures that could potentially be developed, it may be of importance to have some idea of the maximum length of polymer fibers that is achievable by the parallel plate technique. Li et al. collected poly (vinal pyrrolidone) nanofibers across two conductive silicone strips up to several centimeters in length and Teo and Ramakrishna collected PCL nanofibers across two thin steel blades at lengths up to 10 cm [14,15].

We theorized that longer fibers could be collected with a larger collecting device and that the maximum fiber length collected with this device would be affected by the electrospinning parameters. The characteristics of electrospun fibers are determined by many different parameters such as solution composition, polymer solution feed rate, applied voltage, and drop height. The maximum length of fibers that can be collected by the parallel plate method should be affected by these parameters and by the geometry and material characteristics of the collecting device. Optimization of these parameters could lead to the production of longer continuous fibers of a desired length and diameter. In this study the effect of these parameters on length and diameter is measured in order to gain an understanding of the factors that influence fiber diameter, uniformity, and maximum fiber length.

2. Materials and methods

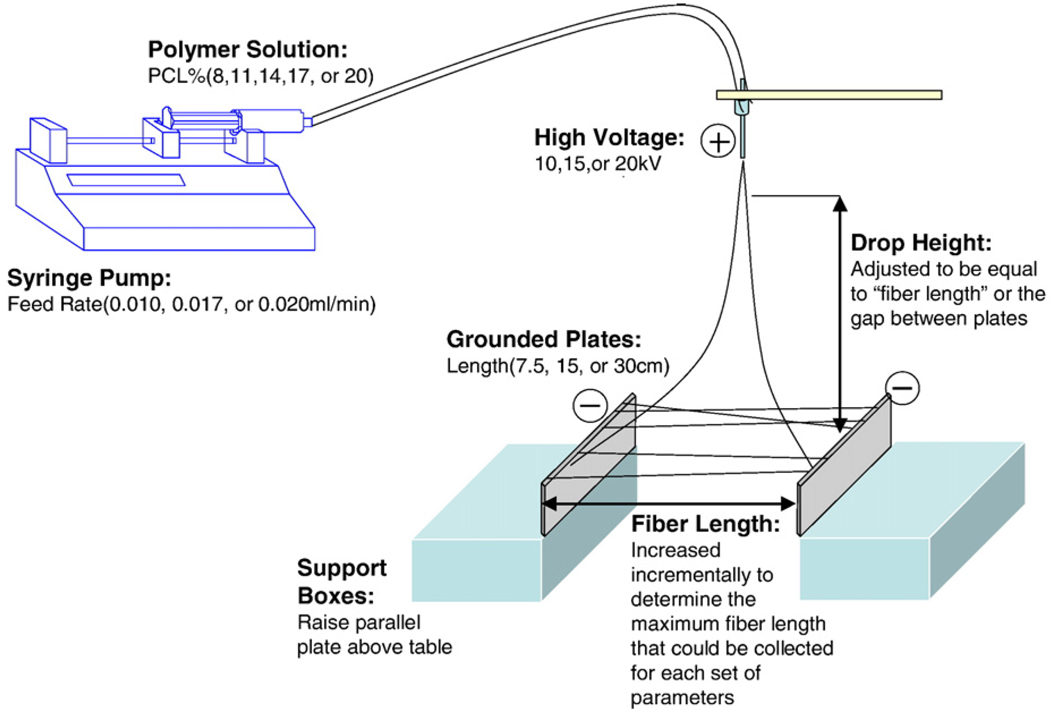

Fibers were electrospun from polymer solutions containing 8, 11, 14, 17, and 20% w/v PCL (Mn 80,000, Sigma) and 0.06% w/v NaCl. Solution shear viscosities were approximately 0.12, 0.22, 0.45, 0.56, and 0.82 Pa respectively as measured with a TA Instruments AR100 rheometer. A 7:3 mixture of dichloromethane (DCM, Alfa Aesar) and methanol (Fisher Scientific) respectively was used as the solvent. To prepare polymer solutions, 6 mg of NaCl was dissolved in 3 ml of methanol and the resulting solution was added to 7 ml of DCM. The desired amount of PCL was then added to obtain the appropriate concentrations. A second 14% PCL solution was mixed without the addition of NaCl. The PCL solutions were transferred to 5 ml syringes and connected to a 30, 23, or 21 gauge blunt tipped needle with polyethylene tubing. The needle tip was connected to a high voltage power source (Gamma High Voltage ES40P-10W) operating at 10, 15 or 20 kV, and polymer solution was feed into the needle at a rate of 0.010, 0.017, or 0.025 ml/min by a syringe pump (Medex inc. Medfusion 2010i). Two identical grounded aluminum plates were used as the collecting device. Three different sizes of plates were used. Dimensions were 30.5 × 7.5 × 0.7, 15 × 4 × 0.35, and 7.5 × 2 × 0.15 cm for large, medium, and small plates respectively. The plates were placed flat with an orientation that made their heights 7.5, 4, or 2 cm and arranged to be parallel along the longest dimension with a gap between them. The electrospinning setup is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Experimental setup for electrospinning across two parallel plates.

The air gap between the two plates was set at a distance estimated to be close to the maximum fiber length and the needle tip was kept at a height equal to the distance between the parallel plates. The gap between the plates and the drop height of the needle tip were adjusted in 2.5 cm increments to determine the maximum distance at which polymer fibers could be collected across the parallel plates. It has been previously shown that fiber collection rate decreases with increasing gap distance and constrains the maximum length at which fibers can be collected [15], therefore extending the length between the plates in increments allows an estimate of the maximum fiber length. Criteria used in making this determination were: (1) Polymer fibers stretched across the gap with each end attached to one of the parallel plates (2) Polymer fibers could be collected at an estimated amount of at least 50 fibers during a 2 min period (3) Polymer fiber collection at that distance was repeatable at least twice consecutively.

In group one, polymer concentration was varied with plate size set at 30.5 × 7.5 × 0.7 cm and NaCl concentration set at 0.06%. In group two, plate size was varied with polymer concentration set at 14% and NaCl concentration set at 0.06%. In group three, NaCl concentration was varied with polymer concentration set at 14% and plate size set at 30.5 × 7.5 × 0.7. Data was collected for all values in each group for all possible combinations of 10, 15, and 20 kV and 0.010, 0.017, and 0.025 ml/min.

Polymer fibers deposited across the parallel plates were adhered to an electron microscope stub moved through the air gap perpendicular to the fibers. Fibers contacting the stub stuck to its surface and were pulled off of the parallel plates. The samples were sputter coated with gold at a thickness of 50–70 nm using a Cressington 108 AUTO sputter-coater with a current of 30 mA for 2 min. Images of the samples were taken at 10,000 times magnification using a scanning election microscope (SEM, Hitachi TM-1000). The diameters of individual fibers were measured using Image-Pro Plus 4.0 and averaged for each group using 17 to 40 measurements per group. Standard deviation % was calculated as the standard deviation of measured fiber diameters for one set of parameters divided by the average fiber diameter for that set of parameter. For this experiment, standard deviation % was used as a measure of the uniformity of the collected fibers. The presence of beaded fibers was quantified by measuring the ratio of the maximum to minimum diameter along the length of randomly selected fiber segments from 10,000× SEM images. At least 65 fiber segments were averaged for 14% PCL solutions with and without NaCl added.

The effects of five different parameters were investigated: PCL %, plate size, NaCl concentration, voltage, and feed rate. The effects of polymer concentration, plate size, and NaCl concentration were analyzed within their groups and the effects of voltage and feed rate were analyzed using all of the data points. The Kruskal–Wallis test was used to determine whether the properties of maximum fiber length, resultant fiber diameter, or uniformity (standard deviation %) were affected by polymer concentration, plate size, NaCl concentration, voltage, or feed rate. The Holm's test was used to further investigate the relationships within the groups that had differences of Kruskal–Wallis significance.

Because of the instabilities in the jet, there was a random factor associated with fiber collection. The rate of fiber collection and the repeatability of fiber collection for a specific electrospinning setup were associated with the probability that fibers were being ejected in a direction that allowed them to collect in the desired location. The maximum fiber length was determined from the distance when the probability of fiber collection across the gap was too low to easily collect samples for analysis based of repeatability (two times consecutively) and rate of collection (estimated minimum of 50 fibers in a 2 min period). A P-value of <0.01 was selected to determine significance because of the variability involved with random fluctuations in the electrospinning jet, and because of the error associated with human observation.

3. Results

Continuous fibers were successfully collected across the parallel aluminum plates for most groups. PCL nanofibers with an average diameter of less than 500 nm were collected at lengths up to 42.5 cm, and PCL nanofibers with an average diameter of less than 1 µm were collected at lengths up to 50 cm. Collected fibers tended to be oriented perpendicular or near perpendicular to the plates. Fibers were also observed to collect on nearby structures that were not part of the collecting device.

Fibers were successfully collected across the parallel plates for all parameter combinations except for at 8% PCL, 0.025 ml/min, and 20 kV; 20% PCL, 10 ml/min, and 15 kV; and all three flow rates in combination with 20% PCL and 20 kV. It appeared from observation that collection was impeded in the 8% PCL, 0.025 ml/min, and 20 kV group because of rapid deposition of unoriented fibers that collided with and broke the fibers collecting across the parallel plates. In the other four groups that failed to collect, fiber formation appeared to be impeded by solution properties.

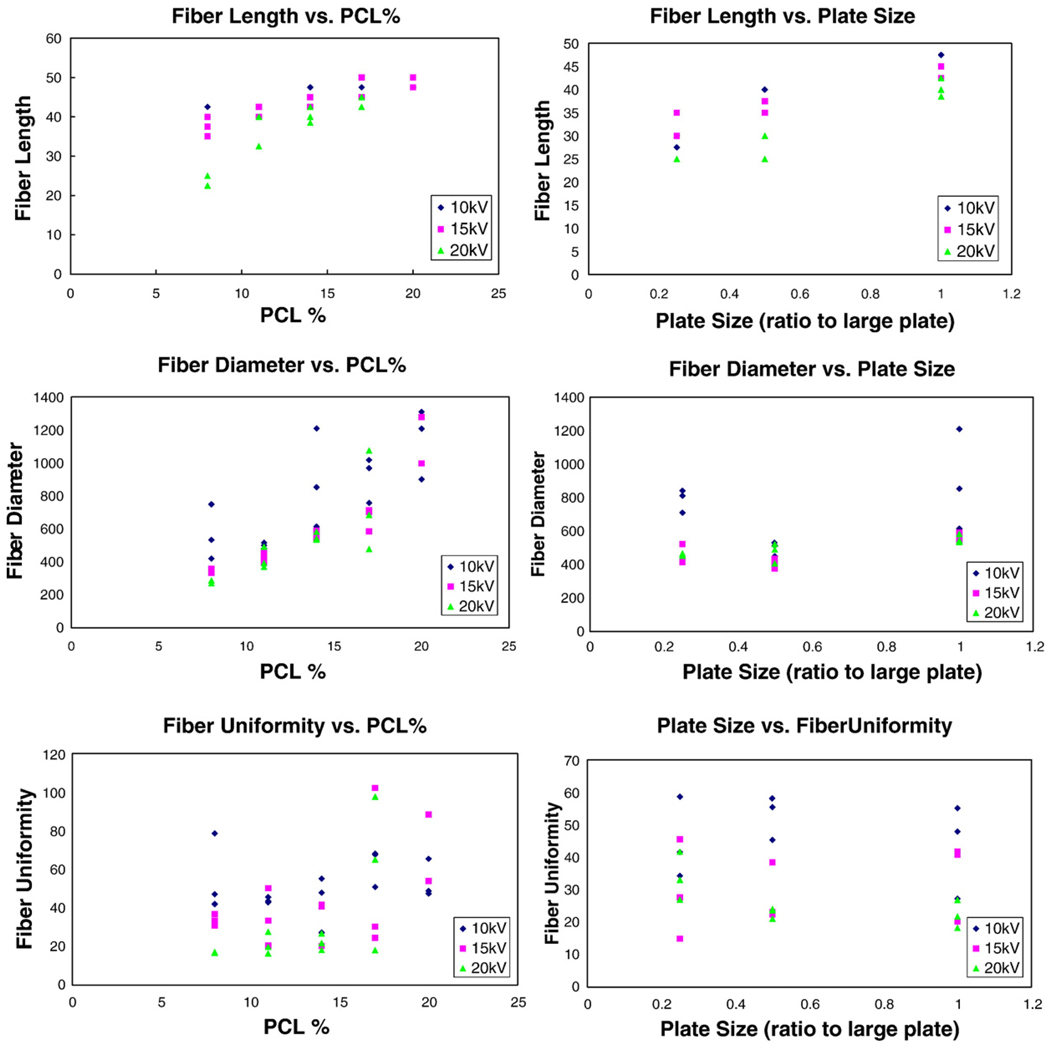

Fiber collection is limited by a number of different factors. In some cases fibers extending across the plates were pulled down off the collecting plates. It was hypothesized that this was due to the electrostatic attraction to the surrounding objects because of the high acceleration observed. In several cases fiber collection proceeded from the bottom up, as electrostatic repulsion from other fibers were able to hold up new fibers on top. Fibers were also observed to fall off the plates because of collisions with other fibers. At some distances fibers were not observed stretching across the plates at all. Data points from the variable polymer concentration and plate size groups are plotted in Fig. 2. Voltage for each data point can be obtained from the legend, but differences in feed rate are not represented.

Fig. 2.

Fiber length, diameter, and uniformity versus polymer concentration and plate size.

3.1. Feed rate

Feed rate was not found to have a significant effect on maximum fiber length, diameter or uniformity over all parameter variations. Once the feed rate is sufficient for forming fibers, higher feed rate only provides more polymer solution than needed, since it was observed that the amount of excess polymer solution formed at the needle tip increased with increasing feed rate (Table 1).

Table 1.

| Kruskal P-value | |

|---|---|

| Feed rate comparison | |

| Length | 0.9 |

| Diameter | 0.6 |

| Standard Dev | 0.7 |

3.2. Polymer concentration

Maximum fiber length and fiber diameter increased with increasing polymer concentration at significant levels with plate size (30.5 × 7.5 × 0.7 cm) and NaCl concentration (0.06%) fixed and variable voltage and feed rate. Significant variation between 8% and 17%, 11% and 17%, and 11% and 20% PCL concentration groups for fiber length was identified by Holm's test. Holm's test also identified significant variation between 11% and 14%, 11% and 17%, and 11% and 20% PCL concentration groups for fiber diameter. Uniformity was observed to decrease with increasing polymer concentration, but not at the required level of significance. Fiber formation was sometimes impeded by the high viscosity of the solution at very high polymer concentration (20%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

| Kruskal P-value | |

|---|---|

| PCL % comparison | |

| Length | 0.00005 |

| Diameter | 0.00002 |

| Standard Dev | 0.03 |

3.3. Voltage

Fiber length and diameter decreased with increasing voltage over all data points, but only fiber diameter decreased at the desired level of significance. Uniformity of the fibers formed increased with increasing voltage at significant levels. Subsequent analysis of individual groups by Holm's test resulted in significant differences between the 10 kV and 15 kV and 10 kV and 20 kV groups for both fiber diameter and fiber uniformity (Table 3).

Table 3.

| Kruskal P-value | |

|---|---|

| Voltage | |

| Length | 0.01 |

| Diameter | 0.003 |

| Standard Dev | 0.00008 |

3.4. NaCl

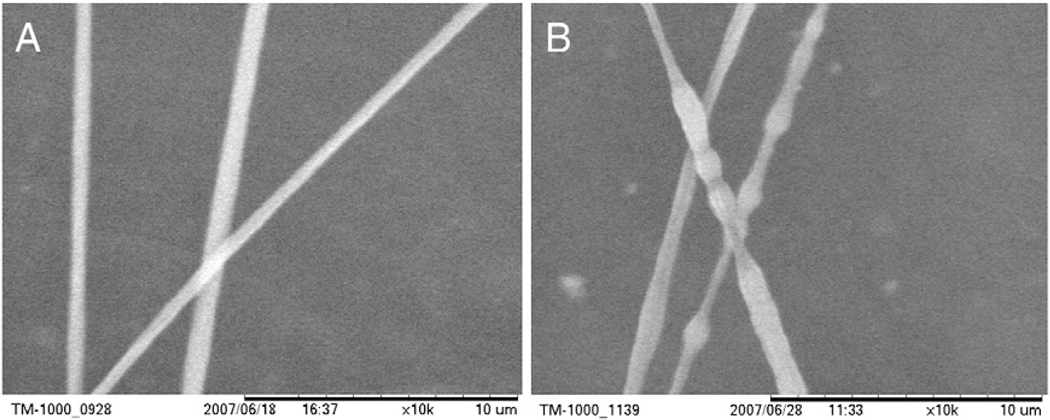

Addition of salts to the polymer solution increases the conductivity of the solution and the surface charge density of the solution jet. Previously, addition of salts to polymer solutions reduced bead defects and decreased fiber diameter when a rotating drum was used as the collecting device [16]. Removal of NaCl from the polymer solution in this experiment did not result in any significant differences in maximum fiber length, diameter, or uniformity for the two NaCl concentration groups with polymer concentration (14%) and plate size fixed (30.5 × 7.5 × 0.7). There was however some observed decrease in fiber diameter with increasing NaCl concentration and fibers with beads were observed only when NaCl was not present in the polymer solution. The presence of beaded fibers due to lack of NaCl was quantified by the ratio of the maximum to minimum diameter of fiber segments in 10,000 times SEM images. The mean diameter ratio for fibers spun with and without NaCl added was 1.16 and 1.66 respectively (p < 0.01). Beaded fibers electrospun from 14% PCL solution with no NaCl added are compared to fibers electrospun with 0.06% NaCl in solution in Fig. 3 (Table 4).

Fig. 3.

Fibers electrospun from 14% PCL solution feed at 10 ml/min and 10 kV applied voltage with (A) and without 0.06% w/v NaCl (B).

Table 4.

| Kruskal P-value | |

|---|---|

| NaCl concentration | |

| Length | 0.8 |

| Diameter | 0.1 |

| Standard Dev | 0.8 |

3.5. Plate size

A significant increase was observed for maximum fiber length and fiber diameter for variations in plate size with PCL concentration (14%) and NaCl content (0.06%) fixed. Analysis of individual groups by Holm's test resulted in significant differences in the small and large, and medium and large plates for fiber length and the medium and large plates for fiber diameter (Table 5).

Table 5.

| Kruskal P-value | |

|---|---|

| Plate size | |

| Length | 0.00007 |

| Diameter | 0.003 |

| Standard Dev | 0.743 |

3.6. Diameter

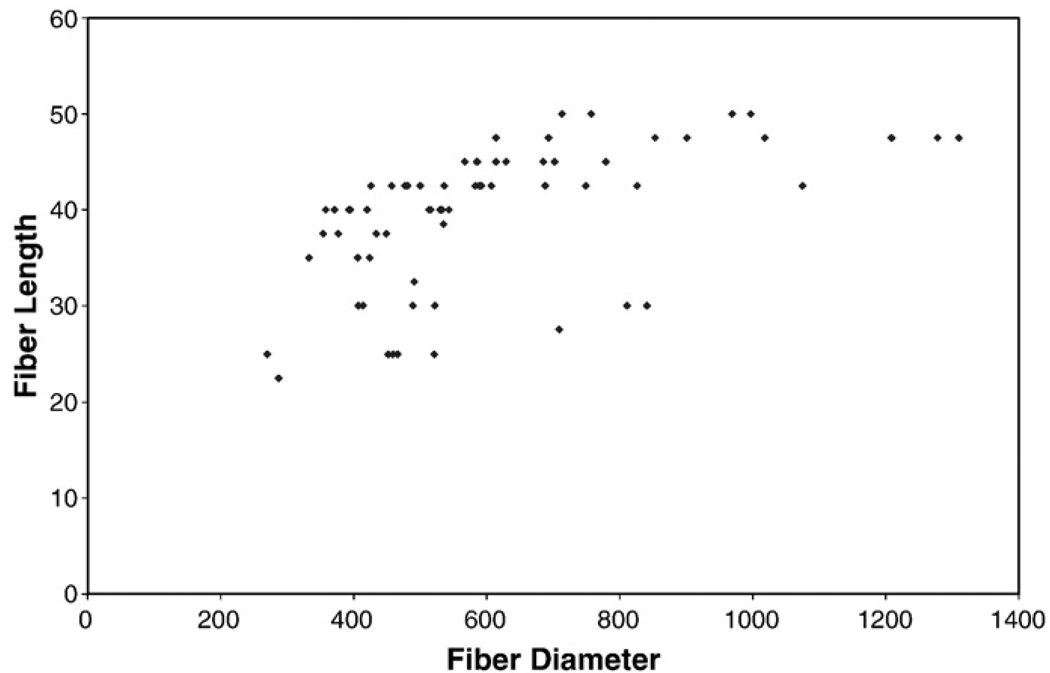

Maximum fiber length was compared to fiber diameter (Fig. 4) to determine if fiber diameter had a limiting relationship on maximum fiber length. There appeared to be some correlation between maximum fiber length and fiber diameter, but this correlation was determined weak by observation.

Fig. 4.

Fiber diameter versus maximum fiber length.

4. Discussion

The data would suggest that of the variables investigated, polymer concentration, applied voltage, and plate size had significant effects on the characteristics of fibers collected by the parallel plate method. The most interesting aspect of this experiment is the question of what the maximum length of PCL nanofibers is under optimum experimental conditions. In analyzing this question it is important to consider whether the limiting factor for maximum fiber length is the formation of continuous correctly oriented fibers or the adhesion of those fibers to the plates without fracture. It has previously been reported that under certain conditions fibers extended across two parallel plates, but broke under their own weight [14].

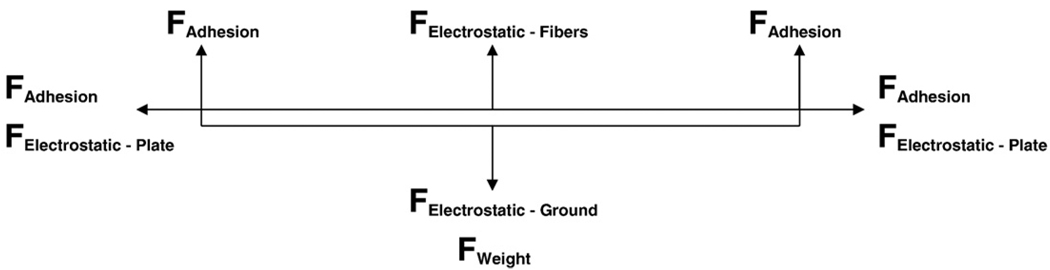

The data suggests that the electrical properties of the jet and the electric field have an effect on both fiber length and fiber diameter as indicated by the observed effect of polymer concentration and applied voltage on maximum fiber length. The forces acting on the fibers after contact with the plate are: adhesion to the plates, the weight of the fiber, electrostatic attraction to the plates, electrostatic attraction to the ground, electrostatic repulsion from other collected fibers, and collisions with other fibers. A diagram of these forces is illustrated in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Forces acting on a single nanofiber electrospun across two parallel plates.

Fiber diameter is a variable that reflects all of the forces acting on the fiber after contacting the plate, therefore if plate adherence or fiber strength were major factors in limiting maximum fiber length then it could be expected that fiber diameter would be strongly related to fiber length.

The data shows some trend of increasing maximum fiber length with increasing fiber diameter, but the wide range of diameters for each fiber length suggests a weak correlation of maximum fiber length and fiber diameter. This would tend to discount the theory that plate adhesion or fiber strength has a strong limiting effect on the maximum fiber length for PCL, a relatively elastic material, across two parallel plates at the distances investigated.

The data suggests that it would be possible to extend the maximum length by increasing the polymer solution concentration or increasing the size of the plates. Polymer solution concentration can only be increased to a certain extent before the viscosity impedes jet formation, but the plate size can be increased without limit to any reasonable size. It is hypothesized that increasing the plate size can increase maximum fiber length to an undetermined value when using the parallel plate method, and it may be of future interest to determine how long electrospun nanofibers can be made by this method under optimum conditions. Nanofibers are a very promising material, but the fabrication of the long continuous individual nanofibers that are required for many applications remains a challenge. Fabrication of increasingly longer nanofibers collected by the parallel plate method using increasingly larger plates will expand the potential uses of electrospinning fabrication to applications that require longer continuous nanofibers.

5. Conclusions

This experiment showed that continuous individual PCL nanofibers with diameters in the range of approximately 350 nm to 1 µm could be collected at lengths of 35 to 50 cm, and that polymer concentration, voltage, and plate size had significant effects on maximum fiber length, fiber diameter, and fiber uniformity. Fibers of this length could potentially be used as single fibers or further assembled into structures for many applications. For practical applications it will be desirable to obtain high quality fibers of a desired length and diameter, with a high degree of uniformity in diameter. It has been shown that all of these parameters can be controlled by changing the electrospinning conditions. It may be of interest to produce relatively long nanofibers for certain applications and it was shown that fiber length could be increased by increasing the PCL concentration in solution and the plate size. Because plate size can be increased without disrupting the electrospinning process, it is hypothesized that plates larger than those used in this experiment could be used to collect significantly longer PCL fibers up to an unknown maximum length. Parallel plate electrospinning could be used to create devices suitable for many different applications and by understanding how to create longer continuous fibers with controlled properties we can expand the versatility of this technique.

Acknowledgments

This work was made possible by NIH Grant Number (R01NS050243) from the (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke), Wallace H. Coulter Foundation, USA, South Carolina Spinal Cord Injury Research Fund.

References

- 1.Ramakrishna Z. Huang. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2003;63:2223. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang Y, et al. J. Mater Sci., Mater. Med. 2005;16(10):933. doi: 10.1007/s10856-005-4428-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kwon IK, Kidoaki S, Matsuda T. Biomaterials. 2005;26(18):3929. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luong-Van E, et al. Biomaterials. 2006;27(9):2042. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chew SY, et al. Biomacromolecules. 2005;6(4):2017. doi: 10.1021/bm0501149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang F, et al. Biomaterials. 2005;26(15):2603. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chua KN, et al. Biomaterials. 2006;27(36):6043. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stitzel J, et al. Biomaterials. 2006;27(7):1088. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahn P, Kim, Hwang, Lee, Shin, Lee Curr. Appl. Phys. 2006;6:1030. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barhate R. J. Membr. Sci. 2007;296:1. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dong L, Huang, Yang, Zheng Mater. Lett. 2007;61:2556. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu L. Li, Zhang Jia, Ryu Yang. Mater. Lett. 2008;62:511. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aussawasathien D. Synth. Met. 2005;154:37. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li D, Wang Yuliang, Xia Younan. Nano Lett. 2003;3(8):1167. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Teo W, Ramakrishna S. Nanotechnology. 2005;16:1878. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zong K, Fang, Ran, Hsiao, Chi Polymer. 2002;43:4403. [Google Scholar]