Abstract

Background: Systematic evaluation of psychosocial distress in oncology outpatients is an important issue. We assessed feasibility and benefit of standardized routine screening using the Distress Thermometer (DT) and Problem List (PL) in all patients of our community-based hematooncology group practice.

Patients and methods: One thousand four hundred forty-six patients were screened between July 2008 and September 2008. Five hundred randomly selected patients were sent a feedback form.

Results: The average distress level was 4.7, with 37% indicating a distress level >5. Patients with nonmalignant diseases (81% autoimmune diseases or hereditary hemochromatosis) showed the highest distress level of 5.2. Most distressed were patients who just learned about relapse or metastases (6.4), patients receiving best supportive care (5.4) and patients receiving adjuvant antihormonal therapy (5.4). Ninety-seven percent of patients appreciated to speak to their doctor about their distress. Fifty-six percent felt better than usual after this consultation.

Conclusion: DT and PL are feasible instruments to measure distress in hematooncology outpatients receiving routine care. DT and PL are able to improve doctor–patient communication and thus should be implemented in routine patient care. The study shows that distress is distributed differently between individuals, disease groups and treatment phases.

Keywords: outpatients, psycho-oncology, psychosocial distress, routine care

introduction

Apart from the physical impairment, psychosocial distress is a major burden for around one-third of oncology patients [1–7]. There is also evidence that a high distress level correlates with a number of negative outcomes like decreased medical adherence, greater desire for death, increased morbidity and length of hospital stays [8–14]. However, the consequences for routine care especially within outpatient settings so far have been little. According to experts, the transfer of psycho-oncological findings into daily practice has been highly insufficient. Most oncologists rely only on their own estimation when assessing their patients’ distress level. This results in a great number of misjudgments [3–15]. One important aim of current research is to systematically and effectively identify patients who are suffering from high emotional distress as a precondition to find appropriate measures to improve their situation. Resident oncologists accompany their patients very closely and sometimes over a long time within these painful phases of their lives. On this account, it is the oncologist's duty not only to look after the patients’ physical condition but also to care about their psychological well-being. Although studies have shown that physicians tend to strongly underrate their patients’ psychosocial distress when relying on their personal appraisal [16–18], only between 10% and 14% of cancer specialists are using standardized screening instruments [19, 20]. Since furthermore both subjective perception of distress and the way patients talk about these issues vary to a great extent, transsectoral standards have to be established and implemented to reliably identify patients requiring specific intervention due to their high level of distress.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network's Distress Thermometer (DT) and Problem List (PL) are brief instruments to evaluate patients’ extent and sources of distress [21]. The DT has been validated within various international studies [22–27] and seems to be a reasonable instrument to overview the patients’ level of distress. Across the different indications and cultural backgrounds, these studies reported cutoff scores between >3 and >6. Based on the German adaptation by Mehnert et al. [28], the Research Group for Psycho-Oncology of the German Association for Hematology and Oncology (AK Psycho-Onkologie der DGHO) recommends the routine use of the DT and PL in German oncology patients with a cutoff score >5 as an indicator to refer the patient to psychosocial service [29]. We decided to use this ultrashort screening method although accuracy has been proven to be rather moderate [30]. But at the same time we expected the patients’ acceptance to participate to be high since it is easy to understand and does not make demands on their time.

With this study, we wanted to explore the DT's and PL's feasibility in routine care of a community-based hematooncology group practice in Germany. During the last 20 years, >300 community-based hematooncology group practices have been established in Germany caring for >500 000 patients per year. Therefore, having an instrument that could easily be implemented in daily practice for the assessment of psychosocial distress and that would be able to improve doctor–patient communication would be of great practical relevance. Furthermore, we expected the instrument to provide sufficient information to talk more effectively about psychosocial matters.

Therefore, it was our intention to test the instrument's practicability as a first-stage screen in daily practice and in which way it contributes to an improvement of the subsequent doctor–patient communication on psychosocial issues. Moreover, we wanted to explore the subjectively perceived level of distress in patients with different diseases undergoing different treatment forms and phases.

Since DT and PL never have been evaluated in routine care outside academic institutions, the aim of the study was to answer three main questions concerning routine patient care in a community-based hematooncology group practice in Germany:

1 Is it feasible to use the DT and PL in routine care?

2 Does the use of DT and PL improve patient–doctor communication?

3 How is distress distributed between outpatients suffering from different diseases and patients within different treatment phases?

patients and methods

All 1446 patients visiting our oncology group practice between July 2008 and September 2008 were asked to complete the DT and PL, a single-item rapid screening tool for distress. On this visual analog scale, patients range their level of distress between ‘0’ (none) and ‘10’ (extreme). On the 36-item PL, the patients indicated specific problems as their individual sources of distress. The list consists of specific aspects from the areas of practical problems, family-related problems, emotional problems, spiritual/religious problems and physical problems. The distress score is being deduced from the information on the DT. The PL provides further information on the nature of the individual patient's distress. DT and PL are depicted in detail in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Distress thermometer (DT) and problem list (PL).

As a cutoff level to consider a patient as highly distressed, we chose a score >5 as it was constituted by the AK Psycho-Onkologie der DGHO.

The questionnaire was filled in while the patients were waiting for the appointment with their doctor. Patients were instructed how to use the tool by staff from the reception desk who also handed the form over to the patient. Most patients answered the questions independently or with the help of their accompanying person. In case patients needed actually further assistance, they received help from their oncologist at the beginning of their consultation visit. The contents then were immediately discussed between doctor and patient. Using another questionnaire, the doctor classified the patient regarding his or her disease, the current form and phase of treatment as well as the recommended or conducted measures of intervention. Possible measures of intervention by the oncologist were as follows:

1 Communication with the patient

2 Referral to psychotherapy

3 Referral to the local cancer society counseling team

4 Psychopharmacotherapy

5 Handing out information material

1 Recommendation for rehabilitation

At the same time, a group of 474 women participating in a mammography screening program (MSP) was asked also to complete the DT and PL as a reference group for our breast cancer patients (BCPs).

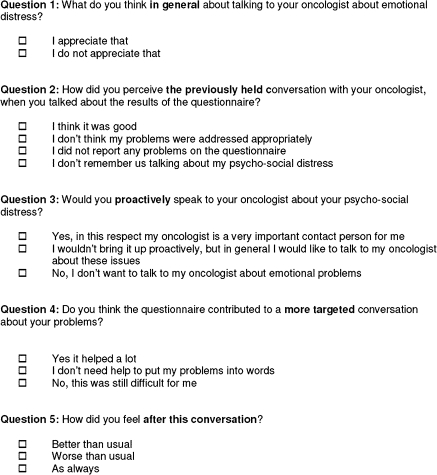

In order to assess the patients’ judgment of the DT's influence on the conversation with their doctor, a random sample of 500 study participants was sent a self-constructed five-item feedback form (see Figure 2). Accompanying an explanatory letter, the questions and predetermined response options were the following:

1.) What do you think in general about talking to your oncologist about emotional distress?

a. I appreciate that

b. I do not appreciate that

2.) How did you perceive the previously held conversation with your oncologist, when you talked about the results of the questionnaire?

a. I think it was good

b. I don't think my problems were addressed appropriately

c. I did not report any problems on the questionnaire

d. I don't remember us talking about my psychosocial distress

3.) Would you proactively speak to your oncologist about your psychosocial distress?

a. Yes, in this respect my oncologist is a very important contact person for me

b. I wouldn't bring it up proactively, but in general I would like to talk to my oncologist about these issues

c. No, I don't want to talk to my oncologist about emotional problems

4.) Do you think the questionnaire contributed to a more targeted conversation about your problems?

a. Yes it helped a lot

b. I don't need help to put my problems into words

c. No, this was still difficult for me

5.) How did you feel after this conversation?

a. Better than usual

b. Worse than usual

c. As always

Figure 2.

Feedback questionnaire.

statistics

Descriptive analysis was carried out for patient characteristics and data from the feedback form. Analysis of variation was carried out to compare the distress level regarding patient characteristics (disease group, age group, treatment phase, BCP versus MSP). Using chi-square test for heterogeneity, we compared the prevalence of problems from the PL for BCP versus MSP. Pearson's r was calculated to describe the correlation between age and distress score and the number of problems (total number, number of emotional problems and number of physical problems, respectively). All statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

results

patient characteristics

One thousand four hundred ninety patients were eligible for this study. Forty-four (3.0%) patients refused to participate or were unable to answer the questions. A total of 1446 patients were eventually enrolled in the study. The median age was 66 years. Forty-three percent were male and 57% were female. The sample comprises 620 (43%) patients with hematological neoplasms, 598 (41%) patients with solid tumors, 154 (11%) patients with benign hematological diseases and 74 (5%) patients with other nonmalignant diseases (mostly with an autoimmune disease or hemochromatosis). Regarding treatment phases, most patients were under observation (19%), receiving palliative i.v. chemotherapy (16%) or oral chemotherapy only (15%). Full patient characteristics are depicted in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Patient characteristics | n | % |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 617 | 43 |

| Female | 829 | 57 |

| Age (years) | ||

| <50 | 246 | 17 |

| 50–59 | 271 | 19 |

| 60–69 | 395 | 27 |

| 70–79 | 395 | 27 |

| ≥80 | 139 | 10 |

| Diagnoses | ||

| Hematological neoplasms | 620 | 43 |

| Myeloproliferative disease | 184 | 30 |

| Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma | 137 | 22 |

| Chronic lymphocytic leukemia | 106 | 17 |

| Multiple myeloma | 76 | 12 |

| Myelodysplastic Syndrome | 59 | 10 |

| Hodgkin's disease | 18 | 3 |

| Hairy cell leukemia | 15 | 2 |

| Acute myeloid leukemia | 14 | 2 |

| Acute lymphocytic leukemia | 8 | 1 |

| Other lymphocytic leukemia | 3 | 0.5 |

| Solid tumors | 598 | 41 |

| Breast | 236 | 39 |

| Digestive organs | 103 | 17 |

| Respiratory and intrathoracic organs | 65 | 11 |

| Male genital organs | 64 | 11 |

| Female genital organs | 33 | 6 |

| Urinary tract | 27 | 5 |

| Skin | 17 | 3 |

| Cancer of unknown primary | 13 | 2 |

| Eye, brain, CNS | 11 | 2 |

| Mesothelialan soft tissue | 11 | 2 |

| Lip, oral cavity and pharynx | 8 | 1 |

| Thyroid and other endocrine glands | 6 | 1 |

| In situ neoplasms | 2 | 0.3 |

| Bone and articular cartilage | 2 | 0.3 |

| Benign hematological diseases | 154 | 11 |

| Anemia | 53 | 34 |

| Purpura and other hemorrhagic conditions | 31 | 20 |

| Other diseases of blood and blood-forming organs | 30 | 19 |

| Monoclonal gammopathy | 19 | 12 |

| Common variable immunodeficiency syndrome | 14 | 9 |

| Coagulation defect | 6 | 4 |

| Exclusion of disease | 1 | 1 |

| Other nonmalignant diseases | 74 | 5 |

| Autoimmune disease | 47 | 64 |

| Hemochromatosis | 13 | 18 |

| Infection | 6 | 8 |

| Other nonmalignant diseases | 5 | 7 |

| Benign neoplasms | 2 | 3 |

| Exclusion of disease | 1 | 1 |

| Treatment phases | ||

| Observation | 270 | 19 |

| Palliative chemotherapy | 225 | 16 |

| Oral chemotherapy only | 217 | 15 |

| Other therapy (mostly bisphosphonates or immunosuppressive therapy) | 139 | 10 |

| Follow-up | 126 | 9 |

| Patients within diagnostic workup | 122 | 8 |

| Best supportive care | 88 | 6 |

| Palliative antihormonal therapy | 62 | 4 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 60 | 4 |

| Adjuvant antihormonal therapy | 52 | 4 |

| Advice/second opinion | 50 | 3 |

| First diagnosis | 21 | 1 |

| Diagnosis of relapse/metastases | 14 | 1 |

CNS, central nervous system.

distress scores and problems

One thousand three hundred thirty-four of 1446 patients rated their distress level on the DT and showed a mean score of 4.7. Thirty-seven percent rated their distress >5 and therefore required specific intervention.

Table 2 shows that younger patients suffer more distress than older patients. A significant negative correlation between age and distress score was seen (r = −0.122; P < 0.001). However, distress rises again after the age of 80 years, with females scoring higher (4.9) on the DT than males with a mean level of 4.5.

Table 2.

Distress scores by age groups

| Distress by age group (years) | Mean | SD | P |

| <50 | 5.4 | 2.78 | <0.001 |

| 50–59 | 5.2 | 2.54 | |

| 60–69 | 4.6 | 2.90 | |

| 70–79 | 4.2 | 2.80 | |

| ≥80 | 4.5 | 2.96 |

SD, standard deviation.

Among the patients of our practice, patients with malignant diseases are not necessarily those to mention the highest levels of distress. On average, patients with nonmalignant non-hematologic diseases—this patient population consisted of patients mostly with autoimmune diseases or hemochromatosis—showed the highest degree of distress (5.2) (Table 3). Considering the treatment phases, the highest level of distress was seen in patients who just learned about their diagnosis of relapsed or metastatic disease (6.4), who received best supportive care (5.4) as well as patients undergoing adjuvant antihormonal treatment (5.4).

Table 3.

Distress scores by disease groups

| Distress by disease group | Mean | SD | P |

| Other nonmalignant diseases | 5.2 | 2.83 | 0.033 |

| Solid tumors | 4.9 | 2.86 | |

| Benign hematologic diseases | 4.7 | 2.77 | |

| Hematologic neoplasms | 4.5 | 2.78 |

SD, standard deviation.

Patients receiving no treatment at all—predominantly patients with early-stage chronic lymphocytic leukemia not yet requiring medical treatment—showed the lowest average distress level of 4.2.

From the PL, the most prevalent problems were fatigue (49%), pain (44%), impaired mobility (41%) and sleep disturbances (41%). A significant correlation was seen between the distress score and the total number of reported problems from the PL (r = 0.529; P < 0.001). Correlations were also observed between the distress score and the number of emotional problems (r = 0.460; P < 0.001) and the number of physical problems (r = 0.442; P < 0.001), respectively. The number of physical and emotional problems also correlated significantly (r = 0.434; P < 0.001).

measures of intervention

Concerning the recommended or conducted measures of intervention, in 70% of all cases, the doctor intervened by talking to the patient about his psychosocial distress himself. Prescription of antipsychotic drugs or referral to a psychotherapist was effected in 6%, respectively. A small number of patients were recommended to consult the local cancer information center (2%), to start certain rehabilitation measures (2%), or were handed information material (1%), though in 28% of distressed patients no intervention was recommended or carried out.

patient feedback

Two hundred thirty-nine of 500 randomly selected patients returned the feedback form by means of which they were asked to give their opinion on the usefulness of the DT and PL for the doctor–patient communication. Ninety-seven percent indicated that they appreciated talking to their doctor about their psychosocial situation. However, for 17%, the initiative had to come from the doctor since they did not consider it appropriate to bring up these topics. One hundred twenty-seven patients regarded themselves as distressed and remembered talking with their doctor about the DT and PL. Fifty percent of these patients perceived the DT and PL as helpful to talk about their distress more precisely. Fifty-six percent stated that they felt better than usual after this consultation. Only one patient felt worse than usual and the rest of patients felt as always (28%) or did not answer this question (16%).

subgroup analysis: BCPs versus mammography screening participants

The subgroup analysis of BCPs with a median age of 62 years compared with participants of an MSP with a median age of 59 years revealed significantly different distress levels of 5.2 for BCP versus 3.3 for MS (P < 0.001). Forty-two percent of BCP scored >5 versus 21% of MSP (P < 0.001). In both groups, there was a significant reverse correlation between age and distress score (MSP: r = −0.158; P = 0.002; BCP: r = −0.161; P = 0.016). In BCP, distress continues to decline also after the age of 80 years. Table 4 shows the distress scores of BCP by treatment phase. Again patients who just found out they had cancer (8.8) and patients receiving best supportive care (7.0) showed the highest distress. Patients undergoing adjuvant antihormonal treatment showed higher distress scores (5.7) than patients under adjuvant chemotherapy (4.3) or palliative therapy (chemotherapy: 5.2; antihormonal therapy: 4.9). The most prevalent problems for BCP were fatigue (58%), fears (53%), sleep disturbances (52%) and pain (50%). The relative risk compared with MSP was 2.1, 2.5, 1.4 and 1.6, respectively. The relative risk for sadness, depression, worry and nervousness was 2.6, 2.1, 1.7 and 1.6, respectively. These differences in risk were statistically significant. Table 5 shows prevalence of all problems from the PL for BCP and MSP.

Table 4.

Breast cancer patients: distress by treatment phase

| Mean | SD | P | |

| First diagnosis | 8.8 | 1.50 | 0.025 |

| Best supportive care | 7.0 | 2.45 | |

| Advice/second opinion | 6.6 | 2.97 | |

| Diagnosis of relapse/metastases | 6.5 | 4.43 | |

| Adjuvant antihormonal therapy | 5.7 | 2.86 | |

| Observation | 5.5 | 2.33 | |

| Palliative chemotherapy | 5.2 | 2.54 | |

| Oral chemotherapy only | 5.2 | 2.89 | |

| Palliative antihormonal therapy | 4.9 | 2.50 | |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 4.3 | 2.40 | |

| Follow-up | 4.3 | 2.70 | |

| Other therapy (mostly bisphosphonates or immunosuppressive therapy) | 3.2 | 3.35 |

SD, standard deviation.

Table 5.

Problems from the PL

| BCP (%) | MSP (%) | P | |

| Fatigue | 58 | 27 | 0.000 |

| Fears | 53 | 21 | 0.000 |

| Sleep | 52 | 37 | 0.000 |

| Pain | 50 | 31 | 0.000 |

| Nervousness | 47 | 29 | 0.000 |

| Getting around | 45 | 23 | 0.000 |

| Worry | 44 | 26 | 0.000 |

| Sadness | 41 | 16 | 0.000 |

| Tingling in hands/feet | 38 | 21 | 0.000 |

| Skin dry/itchy | 30 | 16 | 0.000 |

| Eating | 24 | 5 | 0.000 |

| Nose dry/congested | 24 | 8 | 0.000 |

| Indigestion | 23 | 14 | 0.003 |

| Nausea | 23 | 5 | 0.000 |

| Breathing | 23 | 12 | 0.001 |

| Feeling swollen | 22 | 12 | 0.000 |

| Depression | 21 | 10 | 0.001 |

| Mouth sores | 19 | 7 | 0.000 |

| Constipation | 18 | 7 | 0.000 |

| Dealing with partner | 16 | 10 | 0.038 |

| Changes in urination | 15 | 4 | 0.000 |

| Sexual problems | 14 | 5 | 0.000 |

| Appearance | 14 | 5 | 0.000 |

| Diarrhea | 14 | 7 | 0.004 |

| Dealing with children | 12 | 7 | 0.025 |

| Bathing/dressing | 11 | 2 | 0.000 |

| Work/school | 9 | 12 | 0.115 |

| Housing | 8 | 4 | 0.052 |

| Transportation | 5 | 2 | 0.035 |

| Child care | 4 | 2 | 0.113 |

| Concerning god | 3 | 2 | 0.190 |

| Fevers | 3 | 1 | 0.053 |

| Insurance/financial | 3 | 1 | 0.160 |

| Loss of faith | 1 | 1 | 0.526 |

PL, Problem List; BCP, breast cancer patient; MSP, mammography screening program.

discussion

During the last 20 years >300 community-based hematooncology group practices have been founded in Germany caring for >500 000 patients per year. An instrument that could reliably assess psychosocial distress, improves doctor–patient communication and could easily be implemented in daily practice, would be highly relevant for routine care. DT and PL have been studied extensively in academic institutions. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study evaluating the DT and PL in routine care of outpatients treated in a community-based group practice. With this study we wanted to answer three main questions:

1. Is it feasible to use the DT and PL in routine care?

The answer unequivocally is yes! From 1490 patients, 1446 (97%) could fill out the form. No significant additional workload was created by using the DT and PL in routine care. As a consequence of the positive results of our study, we decided to continue using the DT and PL in daily practice. As from now, every patient in our practice is asked to complete the DT and PL on a regular basis.

2. Does the use of the DT and the PL improve doctor–patient communication?

The answer is yes! Ninety-seven percent of the patients returning the feed back form stated that they appreciate talking to their doctor about their psychosocial situation. Fifty-six percent stated that they felt better than usual after this consultation. Although we did not measure doctor's satisfaction systematically, all five oncologists had the impression that doctor–patient communication was improved by the DT and PL and that the instrument should be part of their future routine patient care. Here, we have to admit some methodological limitations of our study. Since we did not provide for a comparison group, our argument that the modified doctor–patient dialogue achieved an improvement on the patients' distress is based on our impression as well as on the results from our feedback study. The feedback though was only given by nearly half of the patients we had contacted. Under these circumstances, we cannot eliminate the fact that these results may be biased.

3. How is distress distributed between patients suffering from different diseases and patients within different treatment phases in a community-based group practice?

One important result of this study is that psychosocial distress does not necessarily depend on malignancy or prognosis of the patient's disease. Our patient sample features subgroups with a comparatively good prognosis that report the same or even higher distress than patient subgroups with poorer prognoses. Patients with nonmalignant diseases show the highest distress scores. BCPs receiving adjuvant antihormonal treatment are also scoring unexpectedly high compared with BCPs under palliative treatment. These subgroups require the oncologist's permanent watchfulness concerning their psychosocial condition.

It is known that BCPs are a highly distressed subgroup within the population of cancer patients [6] and that younger women undergoing breast cancer treatment report lower quality of life than older women [4, 31–33] but undergoing adjuvant antihormonal treatment seems to be an important aspect that generates psychosocial distress. This is possibly due to the strong physical and psychological impairment caused by the hormonal change that comes along with this kind of therapy of which the benefit remains often unclear. This underlines the importance of an extended baseline discussion with the patient to point out consequences and anticipatory benefit of adjuvant antihormonal treatment.

Against the expectation that this situation is supposed to be very stressful for patients, the patient population under observation—mostly patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia—shows a relatively low distress profile. Most of these patients have visited the practice for many years and the relationship with their doctor is therefore very close and trustful. This plays an important role for the maintenance of their stable psychosocial condition. We have evaluated the instrument in a heterogeneous patient sample representing the reality of patient care in a community-based group practice. Although the DT and PL were originally developed for use in oncology settings, we think that it is also a useful screening instrument for patients with other chronic diseases (i.e. autoimmune diseases).

With a view to the shortcomings of the instrument, we have already mentioned the moderate accuracy with a high rate of false positives and false negatives. One study also found that compared with the scores on the HADS, the DT is more anxiety related than depression related [24]. Originally, the DT is meant only to be used as a screening tool to identify patients who require referral to further psychosocial care. Although a close collaboration between oncologists and mental health professionals is most important and desirable, patients reporting a high distress level are not necessarily referred to psychosocial service. Patients being explicitly or seemingly distressed are routinely offered to make use of psychosocial services. In practice, however, the patient has to accept long waiting periods for these services, which may not be appropriate to the acuteness of the patient's psychological strain. Apart from that, a significant proportion of patients explicitly do not wish to visit a psychotherapist. Through these conversations we came to another important conclusion. Further interrogation of some patients who had reported an extraordinarily high distress level resulted in the knowledge that their distress originated from a totally different source than their disease. In most of these cases, psychosocial referral would have been inappropriate.

Therefore, we considered it important to find out that both oncologists and patients confirmed that the DT and PL influenced the doctor–patient communication in a positive way since it was a useful instrument to speak about psychosocial issues more targeted. This helps to shape the restricted time of consultations more effectively and therefore saves time.

The information from the DT and PL served as indicators for the doctor to ask the right questions. Correspondingly, the final assessment of the patients’ psychosocial needs was made based on the information from the DT and PL as well as the information obtained in the following doctor–patient dialogue and the patient's wish. A very helpful recommendation for the DT's use in daily practice has been made by Gessler et al. [34] who suggest a ‘traffic light system’ with a green light for patients scoring low (0–4) and therefore being treated as usual, a yellow light for patients scoring 5–6, which requires further examination, and a red light for patients scoring ≥7 indicating an excessively increased level of distress. In case of a yellow or red light, the authors recommend close monitoring, the discussion of the matter of distress and referral for specialist intervention if appropriate. In most of the cases, the DT- and PL-induced conversation on psychosocial problems obviously had a relieving effect. This impression was confirmed by the results of our feedback study with more than half of the patients indicating that they felt better after this conversation than usual. This clarifies again the oncologist's important role for comprehensive cancer care. Since health care systems possess limited resources for psychosocial care, the doctor–patient conversation on psychosocial distress also seems to be an economically reasonable first measure and helps to better identify patients who would actually profit from further psychosocial intervention. A well-functioning doctor–patient communication correlates with numerous aspects such as enhanced quality of life, medical adherence and patient satisfaction, whereas malfunctioning communication is associated with increased levels of anxiety, depression, anger and confusion [11, 35–37].

In summary, the DT and PL are very useful screening instruments for psychosocial distress in cancer patients. Our impression is that they improved patient–doctor communication and that they could be easily incorporated into the daily routine of our community outpatient practice. It was well received by patients, doctors and medical staff.

Future research should incorporate the aspect if and in which way an improved doctor–patient communication, which focuses more on the patient's psychosocial problems, can actually reduce the patients’ distress persistently.

funding

TEVA Deutschland GmbH. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by Institut für Versorgungsforschung in der Onkologie (InVO).

disclosures

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Carlson LE, Bultz BD. Cancer distress screening. Needs, models, and methods. J Psychosom Res. 2003;55(5):403–409. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(03)00514-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doebbeling C, Losee L, Powers J, et al. Screening for unmet psycho-social needs in cancer care. ASCO Meeting Abstracts, J Clin Oncol. 2006;18S(20 Suppl) 500s (Abstract 8633) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fallowfield L, Ratcliffe D, Jenkins V, Saul J. Psychiatric morbidity and its recognition by doctors in patients with cancer. Br J Cancer. 2001;84(8):1011–1015. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ganz PA. Psychological and social aspects of breast cancer. Oncology (Williston Park) 2008;22(6):642–646. 650; discussion 650, 653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Graves KD, Arnold SM, Love CL, et al. Distress screening in a multidisciplinary lung cancer clinic: prevalence and predictors of clinically significant distress. Lung Cancer. 2007;55(2):215–224. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herschbach P, Keller M, Knight L, et al. Psychological problems of cancer patients: a cancer distress screening with a cancer-specific questionnaire. Br J Cancer. 2004;91(3):504–511. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zabora J, BrintzenhofeSzoc K, Curbow B, et al. The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psychooncology. 2001;10(1):19–28. doi: 10.1002/1099-1611(200101/02)10:1<19::aid-pon501>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Pessin H, et al. Depression, hopelessness, and desire for hastened death in terminally ill patients with cancer. JAMA. 2000;284(22):2907–2911. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.22.2907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Von Essen L, Larsson G, Oberg K, Sjödén PO. ‘Satisfaction with care’: associations with health-related quality of life and psychosocial function among Swedish patients with endocrine gastrointestinal tumours. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2002;11(2):91–99. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2354.2002.00293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herrmann C, Brand-Driehorst S, Kaminsky B, et al. Diagnostic groups and depressed mood as predictors of 22-month mortality in medical inpatients. Psychosom Med. 1998;60(5):570–577. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199809000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lerman C, Daly M, Walsh WP, et al. Communication between patients with breast cancer and health care providers. Determinants and implications. Cancer. 1993;72(9):2612–2620. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19931101)72:9<2612::aid-cncr2820720916>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richardson JL, Shelton DR, Krailo M, Levine AM. The effect of compliance with treatment on survival among patients with hematologic malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 1990;8(2):356–364. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1990.8.2.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Skarstein J, Aass N, Fosså SD, et al. Anxiety and depression in cancer patients: relation between the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Quality of Life Questionnaire. J Psychosom Res. 2000;49(1):27–34. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(00)00080-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steel JL, Geller DA, Gamblin TC, et al. Depression, immunity, and survival in patients with hepatobiliary carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(17):2397–2405. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.4592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Passik S, Dugan W, McDonald MV, et al. Oncologists’ recognition of depression in their patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(4):1594–1600. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.4.1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Söllner W, DeVries A, Steixner E, et al. How successful are oncologists in identifying patient distress, perceived social support, and need for psychosocial counselling? Br J Cancer. 2001;84(2):179–185. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Newell S, Sanson-Fisher RW, Girgis A, Bonaventura A. How well do medical oncologists‘ perceptions reflect their patients’ reported physical and psychosocial problems? Data from a survey of five oncologists. Cancer. 1998;83(8):1640–1651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keller M, Sommerfeldt S, Fischer C, et al. Recognition of distress and psychiatric morbidity in cancer patients: a multi-method approach. Ann Oncol. 2004;15(8):1243–1249. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pirl WF, Muriel A, Hwang V, et al. Screening for psychosocial distress: a national survey of oncologists. J Support Oncol. 2007;5(10):499–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mitchell AJ, Kaar S, Coggan C, Herdman J. Acceptability of common screening methods used to detect distress and related mood disorders-preferences of cancer specialists and non-specialists. Psychooncology. 2008;17(3):226–236. doi: 10.1002/pon.1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.NCCN. Distress management: clinical practice guidelines. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2003;1:344–374. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2003.0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adams CA, Carter GL, Clover KA. Concurrent validity of the distress thermometer with other validated measures of psychological distress. Abstracts of the 8th world congress of psychooncology, Psychooncology. 2006;15:S105. (Abstr 249) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dolbeault S, Bredart A, Mignot V, et al. Screening for psychological distress in two French cancer centers: feasibility and performance of the adapted distress thermometer. Palliat Support Care. 2008;6(2):107–117. doi: 10.1017/S1478951508000187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gil F, Grassi L, Travado L, et al. Southern European Psycho-Oncology Study Group: use of distress and depression thermometers to measure psychosocial morbidity among southern European cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2005;13(8):600–606. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0780-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacobsen PB, Donovan KA, Trask PC, et al. Screening for psychologic distress in ambulatory cancer patients. Cancer. 2005;103(7):1494–1502. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ransom S, Jacobsen PB, Booth-Jones M. Validation of the Distress Thermometer with bone marrow transplant patients. Psychooncology. 2006;15(7):604–612. doi: 10.1002/pon.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roth AJ, Kornblith AB, Batel-Copel L, et al. Rapid screening for psychologic distress in men with prostate carcinoma: a pilot study. Cancer. 1998;82(10):1904–1908. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19980515)82:10<1904::aid-cncr13>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mehnert A, Müller D, Lehmann C, Koch U. Die Deutsche Version des NCCN Distress-Thermometers. Z Psychiatr Psychol Psychother. 2006;54(3):213–223. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heussner P, Riedner C, Sellschopp A. Psychosoziale Betreuung im Onkologischen Zentrum. Hämatol Onkol. 2007;3:10–12. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mitchell AJ. Pooled results from 38 analyses of the accuracy of distress thermometer and other ultra-short methods of detecting cancer-related mood disorders. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(29):4670–4681. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.0438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wenzel LB, Fairclough DL, Brady MJ, et al. Age-related differences in the quality of life of breast carcinoma patients after treatment. Cancer. 1999;86(9):1768–1774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rakovitch E, Franssen E, Kim J, et al. A comparison of risk perception and psychological morbidity in women with ductal carcinoma in situ and early invasive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2003;77(3):285–293. doi: 10.1023/a:1021853302033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Gestel YR, Voogd AC, Vingerhoets AJ, et al. A comparison of quality of life, disease impact and risk perception in women with invasive breast cancer and ductal carcinoma in situ. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43(3):549–556. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gessler S, Low J, Daniells E, et al. Screening for distress in cancer patients: is the distress thermometer a valid measure in the UK and does it measure change over time? A prospective validation study. Psychooncology. 2008;17:538–547. doi: 10.1002/pon.1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heussner P, Huber B, Sellschopp A. Integrierte psycho-onkologische Diagnostik im Rahmen eines Clinical Cancer Centers. Psychoonkologie. 2006:S175–S180. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holland JC. American Cancer Society Award lecture. Psychological care of patients: psycho-oncology's contribution. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(23 Suppl):253s–265s. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.09.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lehmann C, Koch U, Mehnert A. Die Bedeutung der Arzt-Patient-Kommunikation für die psychische Belastung und die Inanspruchnahme von Unterstützungsangeboten bei Krebspatienten: Ein Literaturüberblick über den gegenwärtigen Forschungsstand unter besonderer Berücksichtigung patientenseitiger Präferenzen. Psychother Psych Med. 2009;59(7):3–27. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1067443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]