Abstract

FtsH (HflB) is an Escherichia coli ATP-dependent protease that degrades some integral membrane and cytoplasmic proteins. While anchored to the cytoplasmic membrane by the two transmembrane (TM) segments near the N-terminus, it has a large cytoplasmic domain. The N-terminal region also has a role in homo-oligomerization of this protein. To study the significance of the membrane integration and oligomer formation, we constructed FtsH derivatives in which the N-terminal region had been deleted or replaced with either the leucine zipper sequence from Saccharomyces cerevisiae GCN4 protein or TM regions from other membrane proteins. The cytoplasmic domain, which was monomeric and virtually inactive, was converted, by the attachment of the leucine zipper, to an oligomer with proteolytic function against a soluble, but not a membrane-bound substrate. In contrast, chimeric TM–FtsH proteins were active against both substrate classes. We suggest that the cytoplasmic domain has intrinsic but weak self-interaction ability, which becomes effective with the aid of the leucine zipper or membrane tethering, and that membrane association is essential for FtsH to degrade integral membrane proteins.

Keywords: AAA ATPase/membrane protein/oligomerization/protein degradation

Introduction

Membrane proteins serve as structural components as well as catalysts of substrate transport and signal transduction. Their quality control is critical for maintenance of the membrane functions. However, our knowledge about how aberrant membrane proteins are degraded has been limited until recently.

In Escherichia coli, FtsH, a membrane-bound and ATP-dependent metalloprotease, is involved in degradation of some integral membrane proteins (Kihara et al., 1995; Akiyama et al., 1996b). This is the only integral membrane protein among the ATP-dependent proteases of E.coli (Gottesman et al., 1997). It has two transmembrane (TM) segments at the N-terminal region, which is followed by a large cytoplasmic domain (Tomoyasu et al., 1993a). Like other ATP-dependent proteases, FtsH has a homo-oligomeric structure (Akiyama et al., 1995). We showed that the N-terminal region is important for homo-oligomerization (Akiyama et al., 1995). The cytoplasmic region contains two subdomains: an AAA ATPase domain located just C-terminal to the membrane region and a protease domain with the HEXXH zinc-binding motif (Tomoyasu et al., 1993b).

We also showed that FtsH is at least partly in complex with a pair of membrane proteins, HflK and HflC, which themselves form a complex (HflKC) (Kihara et al., 1996). HflKC seems to regulate FtsH function (Kihara et al., 1996, 1998). The short periplasmic domain between the TM segments of FtsH is essential for the interaction with the periplasmically exposed HflKC complex (Akiyama et al., 1998b).

Membrane-bound substrates of FtsH include several multi-spanning membrane proteins, such as SecY (Kihara et al., 1995), subunit a of the proton ATPase (F0a) (Akiyama et al., 1996a) and the product of the yccA open reading frame (Kihara et al., 1998). Whereas the SecY subunit and the F0a subunit are degraded rapidly when they fail to associate with their partner proteins, YccA is degraded more slowly and its cellular function is unknown.

The cytoplasmic localization of the enzymatic domains of FtsH raises a question of whether and how it hydrolyzes the membrane-integrated and periplasmically exposed regions of a substrate protein. We examined in vivo degradation profiles of YccA and SecY derivatives that had an alkaline phosphatase (PhoA) domain inserted into a periplasmic region of these proteins (Kihara et al., 1999). The FtsH-mediated proteolysis seemed to propagate rapidly into the PhoA reporter region when the PhoA part remained unfolded. In contrast, the degradation stopped before the PhoA domain when it was tightly folded. From these results, we proposed that FtsH-mediated degradation of membrane proteins is processive and accompanied by dislocation of the periplasmic domains to the cytoplasmic side (Kihara et al., 1999).

In the present work, we studied the significance of membrane integration and multimerization in the functions of FtsH. We constructed and analyzed several derivatives of FtsH in which the membrane region was deleted, or replaced either with a leucine zipper sequence or with TM regions of other membrane proteins. The results suggested that multimerization of the cytoplasmic domain is essential for the proteolytic activity of FtsH, but without a TM region it cannot work against membrane proteins. We propose that FtsH-catalyzed degradation of membrane proteins requires membrane integration of this enzyme.

Results

In vivo proteolytic functions of FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc and Zip-FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc

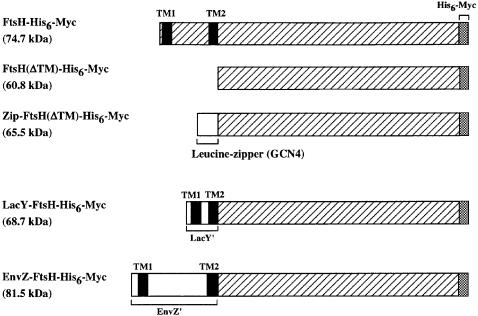

As a first step in our examination of the role of the membrane region, N-terminal residues 1–123 were deleted from FtsH-His6-Myc [FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc in Figure 1]. We also constructed Zip-FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc in which the leucine zipper sequence from the Saccharomyces cerevisiae GCN4 protein (Karimova et al., 1998) was attached to the N-terminus of FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc (Figure 1). Because the N-terminal region is required not only for membrane localization (Tomoyasu et al., 1993a) but also for multimerization of FtsH (Akiyama et al., 1995), FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc was expected to be monomeric and soluble. The leucine zipper sequence was thought to induce dimerization of FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc.

Fig. 1. Schematic representations of FtsH-His6-Myc, FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc, Zip-FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc, LacY-FtsH-His6-Myc and EnvZ-FtsH-His6-Myc used in this study. All the proteins carried the C-terminal His6-Myc tag. Hatched regions are derived from FtsH. TM1 and TM2 indicate the first and second TM segments of either FtsH, LacY or EnvZ. The molecular mass of each protein calculated from the amino acid sequence is indicated in parentheses.

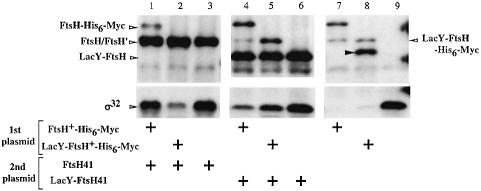

To assess the in vivo abilities of these proteins to degrade soluble and membrane-bound substrates, cellular accumulation of σ32 (chromosomally encoded) and SecY (overexpressed from a plasmid; Taura et al., 1993) was examined by immunoblotting (Figure 2). We used ΔftsH cells, which allowed high level accumulation of these proteins (Figure 2, lane 1), and their reduction was taken as the proteolytic activity of FtsH-His6-Myc derivatives expressed from a compatible plasmid. In contrast to FtsH-His6-Myc, which reduced the amounts of σ32 and SecY markedly (Figure 2, lane 2), expression of FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc at a similar level did not significantly affect the levels of σ32 and SecY (lane 3), although its higher overproduction resulted in a slight reduction of σ32 (data not shown). Thus, the cytoplasmic domain alone is largely non-functional.

Fig. 2. Accumulation of SecY and σ32 in cells expressing FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc or Zip-FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc. Strain AR5090 (ΔftsH) carrying pKY248 (secY) was transformed further with the plasmids indicated below. Cells were grown in L medium at 30°C and induced with 1 mM IPTG and 5 mM cAMP for 2.5 h. Proteins were precipitated by 5% trichloroacetic acid and analyzed by SDS–PAGE followed by immunoblotting using anti-FtsH, anti-σ32 or anti-SecY antibodies as indicated. The second plasmids carried were: pUC119 (vector; lane 1), pSTD113 (ftsH-his6-myc; lane 2), pSTD219 [ftsH(ΔTM)-his6-myc; lane 3], pSTD430 [zip-ftsH(ΔTM)-his6-myc; lane 4], pSTD432 [zip-ftsH317(ΔTM)-his6-myc; lane 5] and pSTD444 [zip-ftsH41(ΔTM)-his6-myc; lane 6]. FtsH′ indicates C-terminally self-processed product of FtsH-His6-Myc (Akiyama, 1999) (lane 1).

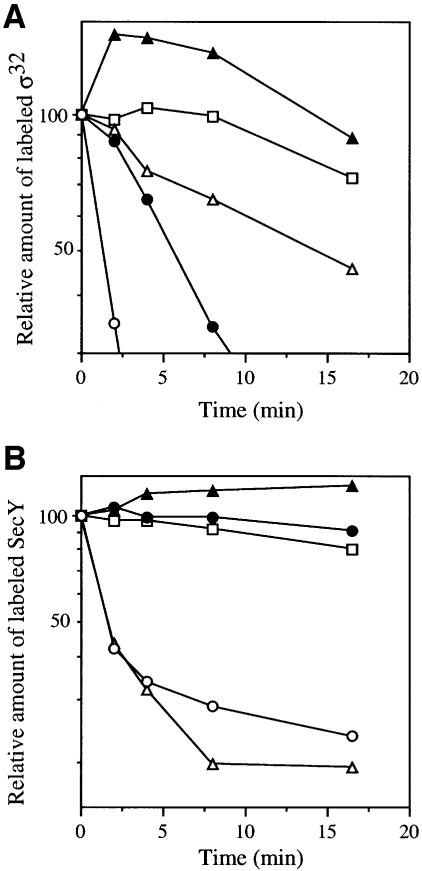

In contrast, Zip-FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc strikingly lowered the level of σ32 (Figure 2, lane 4). Therefore, proteolytic activity was fully regained by the attachment of the leucine zipper sequence. A mutant form of Zip-FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc with a mutation in the protease active site (ftsH317) (Figure 2, lane 5) or in the ATP-binding site (ftsH41) (lane 6) did not reduce the accumulation of σ32 appreciably even when they were expressed at higher levels. Thus, the activities observed with Zip-FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc were dependent on the normal activities of FtsH. Interestingly, accumulation of SecY was not affected by Zip-FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc (Figure 2, lane 4). These results were substantiated more directly by pulse–chase experiments (Figure 3). Zip-FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc greatly enhanced the degradation of σ32 (Figure 3A, solid circles) but not of SecY (Figure 3B, solid circles). Both of these substrates were stable in the presence of FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc (solid triangles). These results indicate that: (i) the cytosolic domain of FtsH is barely active; (ii) it is activated by the N-terminal addition of the leucine zipper sequence with respect to proteolysis against σ32; and (iii) the leucine zipper sequence is still unable to confer proteolytic activity against SecY.

Fig. 3. Degradation of σ32 and SecY in cells expressing FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc, Zip-FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc or LacY-FtsH-His6-Myc. Plasmids pSTD113 (ftsH-his6-myc; open circles), pSTD430 [zip-ftsH(ΔTM)-his6-myc; solid circles], pSTD348 (lacY-ftsH-his6-myc; open triangles), pSTD219 [ftsH(ΔTM)-his6-myc; solid triangles] and pUC119 (vector; open squares) were introduced into AR5090 (ΔftsH) to examine σ32 stability (A) or into AR5090 carrying pKY248 (secY) to examine SecY stability (B). Cells were grown in M9 medium at 30°C, induced with 1 mM IPTG and 5 mM cAMP for 2 h, pulse-labeled with [35S]methionine for 2 min and chased with unlabeled methionine for the indicated time. At each time point, a portion of culture was treated with trichloroacetic acid for subsequent immunoprecipitation of σ32 (A) or SecY (B). σ32 and SecY radioactivities were determined after SDS–PAGE, and are reported as a percentage of the initial (0 min chase) radioactivity for each culture.

Oligomeric states of FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc and Zip-FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc

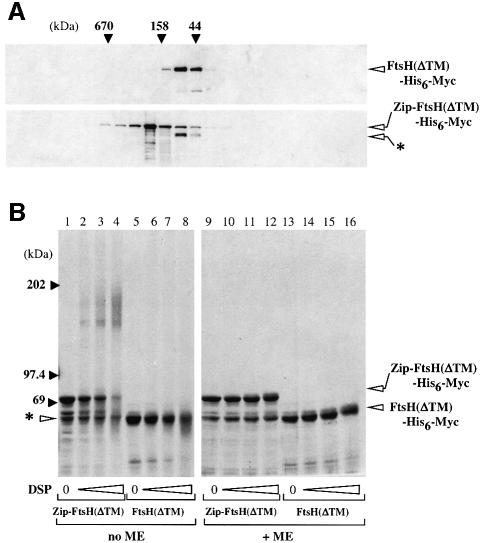

Upon cell fractionation, both FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc and Zip-FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc were recovered almost exclusively in the soluble cytoplasmic fraction (data not shown). When Zip-FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc (calculated molecular mass 65.5 kDa) was highly overproduced, it formed a doublet of ∼70 and ∼60 kDa upon electrophoresis (Figure 4B, lane 9). The lower band had almost the same mobility as FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc (calculated molecular mass 60.8 kDa) and reacted with both anti-FtsH (see Figure 4A) and anti-Myc (data not shown). Zip-FtsH317(ΔTM)-His6-Myc did not produce the doublet (data not shown). These observations suggest that the lower band represented a product of self-cleavage around the junction between the leucine zipper and FtsH(ΔTM).

Fig. 4. Oligomeric states of FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc and Zip-FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc. (A) Gel filtration. Purified preparations of FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc (upper panel) and Zip-FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc (lower panel) (12.5 µg each) were fractionated by Superose 6 gel filtration chromatography. Each fraction was examined for FtsH content by SDS–PAGE and anti-FtsH immunoblotting. The molecular mass markers (indicated at the top) used were: thyroglobulin (670 kDa), bovine γ-globulin (158 kDa) and chicken ovalbumin (44 kDa). (B) Cross-linking. Zip-FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc (lanes 1–4 and 9–12) and FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc (lanes 5–8 and 13–16) were treated with 0 (lanes 1, 5, 9 and 13), 62.5 (lanes 2, 6, 10 and 14), 187.5 (lanes 3, 7, 11 and 15) or 562.5 (lanes 4, 8, 12 and 16) µg/ml DSP at 4°C for 1 h. Samples were analyzed by SDS–PAGE, with (+ME) or without (no ME) 2-mercaptoethanol, and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. Asterisks indicate a self-cleaved product of Zip-FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc.

We purified the proteins using Ni-NTA affinity chromatography and examined their profiles by gel filtration chromatography (Figure 4A). FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc and the self-cleavage product of Zip-FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc were recovered at fractions corresponding to ∼70 kDa. On the other hand, the intact Zip-FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc protein (upper band) was eluted earlier, at fractions corresponding to ∼170 kDa.

The oligomeric states of the purified proteins were also examined by cross-linking experiments (Figure 4B). Purified preparations of FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc and Zip-FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc were treated with increasing concentrations of a disulfide-cleavable cross-linker, dithiobis(succinimidyl propinate) (DSP) and subjected to SDS–PAGE before and after cleavage of the cross-link. DSP-treated Zip-FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc yielded slow migrating products with apparent molecular masses of ∼155 and 175 kDa (Figure 4B, lanes 1–4), which disappeared upon reduction (lanes 9–12). No such cross-linked product was generated from FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc (Figure 4B, lanes 5–8).

Taken together, these results suggest that FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc is monomeric whereas Zip-FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc is at least dimeric. The generation of two cross-linked products for Zip-FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc might have been due to cross-linking at different residues.

In vivo proteolytic functions of LacY-FtsH-His6-Myc and EnvZ-FtsH-His6-Myc

To address the significance of membrane localization, the TM region of FtsH was replaced with those of two unrelated membrane proteins, EnvZ and LacY (Figure 1). EnvZ has two N-terminal TM segments of the same topology as FtsH (Forst et al., 1987), whereas LacY contains 12 TM segments (Calamia and Manoil, 1990). The EnvZ–FtsH fusion protein consists of the entire TM region of EnvZ followed by the FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc sequence, whereas LacY-FtsH-His6-Myc consists of the N-terminal region of LacY, including the first and the second TM segments, followed by the FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc sequence.

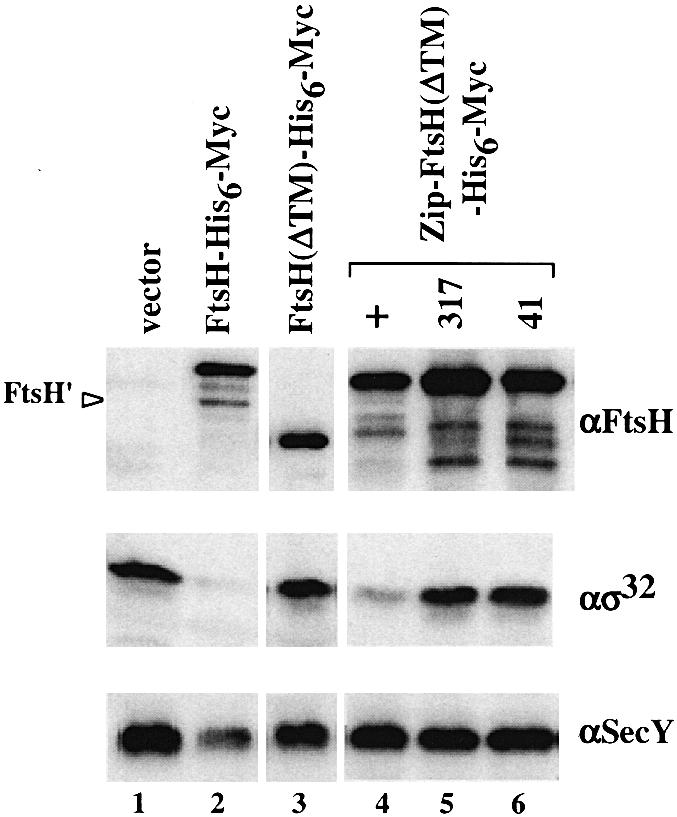

The proteolytic functions of these proteins were examined by expressing them in the ΔftsH cells as described above. As shown in Figure 5, LacY-FtsH-His6-Myc (lane 3) and EnvZ-FtsH-His6-Myc (lane 6) both lowered the levels of SecY as well as of σ32. They were as effective as FtsH-His6-Myc (Figure 5, lane 1). Fusion proteins with the ftsH317 mutation were ineffective (Figure 5, lanes 2 and 4). Pulse–chase experiments (Figure 3) showed that expression of LacY-FtsH was accompanied by rapid degradation of SecY (Figure 3B, open triangles) and significant degradation of σ32 (Figure 3A, open triangles). These results indicate that LacY-FtsH-His6-Myc and EnvZ-FtsH-His6-Myc are as active as FtsH-His6-Myc in degrading the membrane-bound substrates. LacY-FtsH-His6-Myc and EnvZ-FtsH-His6-Myc underwent the cleavage around the fusion junction as indicated by the generation of anti-Myc- and anti-FtsH-reacting fragments of smaller sizes (Figure 5, lanes 3 and 6). This cleavage was due to self-processing since it was blocked by the ftsH317 mutation (lane 4 and data not shown for EnvZ-FtsH-His6-Myc).

Fig. 5. Accumulation of SecY and σ32 in cells expressing LacY-FtsH-His6-Myc or EnvZ-FtsH-His6-Myc. Strain AR5090 (ΔftsH) carrying pKY248 (secY) was transformed further with the plasmids indicated below. Accumulation of SecY and σ32 was examined as described in the legend to Figure 2. The second plasmids carried were: pSTD120 (ftsH-his6-myc; lane 1), pSTD319 (ftsH317-his6-myc; lane 2), pSTD350 (lacY-ftsH-his6-myc; lane 3), pSTD389 (lacY-ftsH317-his6-myc; lane 4), pMW119H (vector; lane 5), pSTD310 (envZ-ftsH-his6-myc; lane 6) and pTYE007B (vector; lane 7). Arrowheads indicate the cytoplasmic domain of FtsH-His6-Myc generated by self-cleavage between the fusion junction of LacY-FtsH-His6-Myc (lane 3) or EnvZ-FtsH-His6-Myc (lane 6).

In vivo degradation of YccA-(P3)-PhoA-His6-Myc by Zip-FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc and LacY-FtsH-His6-Myc

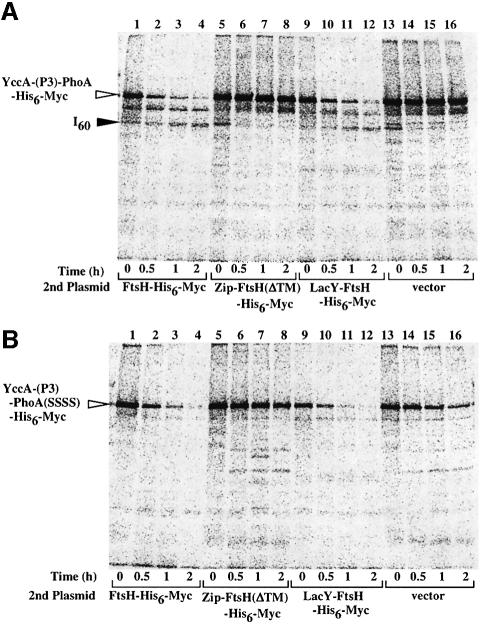

YccA spans the cytoplasmic membrane seven times with a cytoplasmic N-terminus and a periplasmic C-terminus (Kihara et al., 1998). We previously examined the mode of the FtsH-dependent degradation of YccA-(P3)-PhoA-His6-Myc, having the PhoA sequence inserted within the third periplasmic region (Kihara et al., 1999). Folding of the PhoA domain depends on DsbA-dependent formation of its intramolecular disulfide bonds. Whereas the periplasmic PhoA domain was degraded completely in a dsbA– background in an FtsH-dependent manner, the degradation stopped before the PhoA domain in a dsbA+ background. Thus, a product containing a segment from the PhoA domain to the C-terminus, termed I60, was generated in the latter background. These and other observations led us to propose that FtsH degrades YccA-(P3)-PhoA-His6-Myc processively in the N to C direction and that the periplasmically exposed regions are dislocated to the cytoplasmic side during the proteolysis (Kihara et al., 1999).

We addressed the question of whether the degradation profile of YccA-(P3)-PhoA-His6-Myc was affected in cells in which Zip-FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc or LacY-FtsH-His6-Myc substituted for normal FtsH (Figure 6). Degradation of YccA-(P3)-PhoA-His6-Myc was examined by pulse–chase experiments in ΔftsH dsbA+ cells that were complemented with either FtsH-His6-Myc (lanes 1–4), Zip-FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc (lanes 5–8) or LacY-FtsH-His6-Myc (lanes 9–12). YccA-(P3)-PhoA-His6-Myc was stable in the ΔftsH cells (Figure 6A, lanes 13–16) as well as in those cells with Zip-FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc (Figure 6A, lanes 5–8). FtsH-His6-Myc (lanes 1–4) and LacY-FtsH-His6-Myc (lanes 9–12) led to rapid degradation of YccA-(P3)-PhoA-His6-Myc with the concomitant appearance of a 60 kDa fragment of the same mobility as I60, which reacted with both anti-PhoA (lanes 4 and 12) and anti-Myc (data not shown). To examine degradation of an unfolded PhoA domain, we constructed YccA-(P3)-PhoA(SSSS)-His6-Myc, in which all four cysteines in PhoA had been replaced by serine. Different FtsH derivatives produced essentially the same effects on YccA-(P3)-PhoA(SSSS)-His6-Myc as on YccA-(P3)-PhoA-His6-Myc, except that degradation of the former substrate was not accompanied by the production of the I60 product (Figure 6B). These results suggest that LacY-FtsH-His6-Myc is able to induce dislocation of a periplasmic domain that lacks tight folding. In contrast, Zip-FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc is unable to degrade the two membrane protein substrates examined.

Fig. 6. Degradation of YccA-(P3)-PhoA-His6-Myc in cells expressing FtsH-His6-Myc, Zip-FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc or LacY-FtsH-His6-Myc. AR5090 (ΔftsH) carrying pKH412 [yccA-(P3)-phoA-his6-myc] (A) and that carrying pSTD423 [yccA-(P3)-phoA(SSSS)-his6-myc] (B) were transformed further with the plasmids indicated below. Pulse–chase experiments were carried out as described in the legend to Figure 3, except that the growth temperature was 28°C and immunoprecipitation was with anti-PhoA. Anti-Myc gave similar results (data not shown). I60 indicates the degradation product of YccA-(P3)-PhoA-His6-Myc, which consists of the PhoA domain and the C-terminal end. The second plasmids carried were: pSTD113 (ftsH-his6-myc; lanes 1–4), pSTD430 [zip-ftsH(ΔTM)-his6-myc; lanes 5–8], pSTD348 (lacY-ftsH-his6-myc; lanes 9–12) and pTYE007B (vector; lanes 13–16).

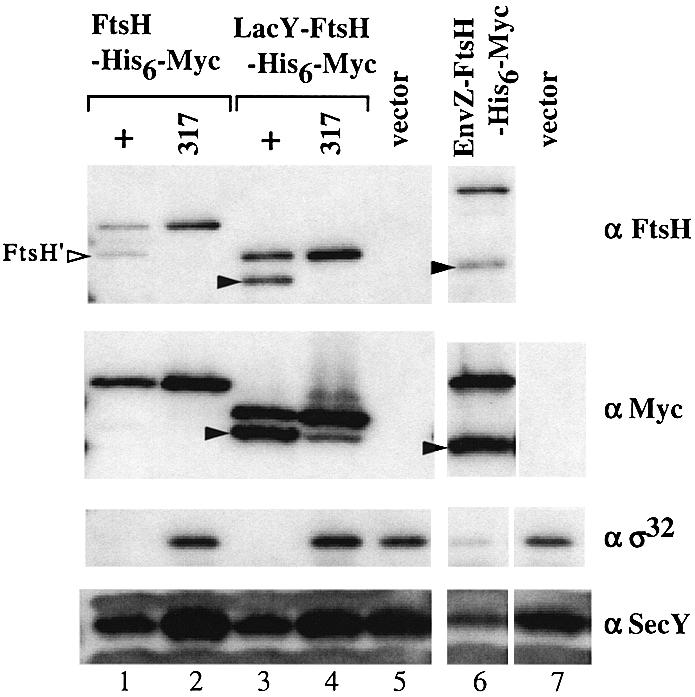

Dominant interference with LacY-FtsH-His6-Myc function by ATPase mutants

We showed previously that a number of non-functional mutant forms of FtsH dominantly inhibit the function of wild-type FtsH (Akiyama et al., 1994). Thus, σ32 was stabilized by co-expression of FtsH41 in the presence of FtsH-His6-Myc (Figure 7, compare lanes 1 and 7). We now find that FtsH41 exerted much weaker inbibition against LacY-FtsH (Figure 7, lanes 1 and 2). Interestingly, LacY-FtsH with the ftsH41 mutation (LacY-FtsH41) dominantly inhibited LacY-FtsH itself in degrading σ32 (Figure 7, lanes 5 and 8), but not FtsH (lane 4). The combination-specific dominant interference suggests that the dominant effects were not due to sequestration of the substrate by the inactive FtsH molecules. The simplest explanation may be that they preferentially sequester the respective wild-type counterpart. Thus, FtsH molecules, whether wild-type or with the ftsH41 mutation, oligomerize themselves in an exclusive manner. Thus co-existing LacY-FtsH molecules are left behind. Our results thus indicate that the latter molecules still interact mutually. Since LacY is monomeric (Sahin-Tóth et al., 1994), it seems unlikely that its TM1–TM2 region oligomerizes. We suggest that the cytosolic domain of FtsH has intrinsic self-interaction ability, which becomes apparent in the LacY-FtsH configuration. In support of this notion, we found that FtsH41(ΔTM) interfered weakly but significantly with LacY-FtsH-mediated σ32 degradation, but not with that mediated by FtsH (data not shown).

Fig. 7. Dominant inhibition of LacY-FtsH-His6-Myc by LacY-FtsH41. Strain AR5090 (ΔftsH) was transformed with combinations of two plasmids, one (1st plasmid) encoding a functional FtsH derivatives and the other (2nd plasmid) encoding a non-functional FtsH41 derivative. Cells were grown at 37°C and induced with 1 mM IPTG for 2.5 h. Total proteins were analyzed by 10% SDS–PAGE followed by immunoblotting using anti-FtsH or anti-σ32 as indicated. For the explanation of the closed arrowhead see legend to Figure 5. The second plasmids carried were: pSTD405 (ftsH41; lanes 1–3), pSTD406 (lacY-ftsH41; lanes 4–6) and pSTV28 (vector; lanes 7–9). The first plasmids carried were: pSTD120 (ftsH-his6-myc; lanes 1, 4 and 7), pSTD350 (lacY-ftsH-his6-myc; lanes 2, 5 and 8) and pMW119H (vector; lanes 3, 6 and 9).

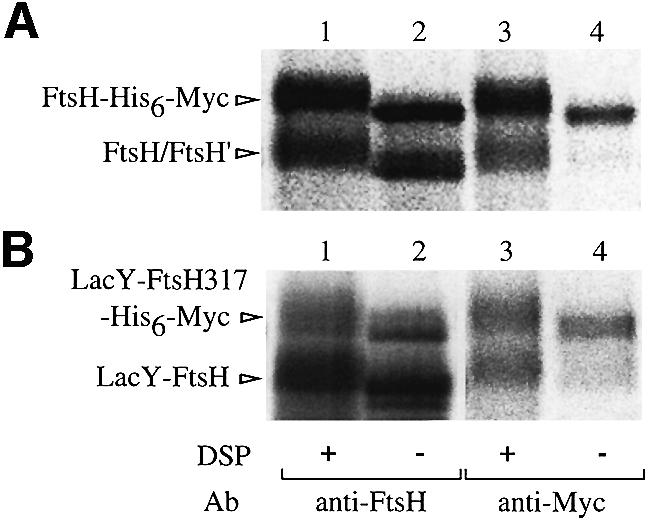

Cross-linking analysis of LacY-FtsH-His6-Myc

The self-interacting property of LacY-FtsH-His6-Myc was studied by cross-linking experiments (Figure 8). Mem brane fractions were prepared from pulse-labeled cells containing His6-Myc-tagged and untagged versions of FtsH or LacY-FtsH (LacY-FtsH317-His6-Myc was used as a tagged protein to prevent self-processing) and they were treated with DSP. Proteins were solubilized with SDS, immunoprecipitated with anti-FtsH or anti-Myc and analyzed by SDS–PAGE following cleavage of cross-linkages. As reported previously (Akiyama et al., 1995), FtsH without the tag was recovered with anti-Myc antibodies only when the sample had been treated with DSP (Figure 8A, lanes 3 and 4). Similarly, LacY-FtsH was precipitated with anti-Myc in a DSP-dependent manner (Figure 8B, lanes 3 and 4). These results indicate that LacY-FtsH molecules were in close proximity to LacY-FtsH-His6-Myc on the membrane. Thus, LacY-FtsH can interact homotypically.

Fig. 8. Cross-linking of LacY-FtsH. Membranes prepared from [35S]methionine-labeled cells of AD21 (WT)/pSTD401 (ftsH)/pSTD113 (ftsH-his6-myc) (A) or AD21/pSTD393 (lacY-ftsH)/pSTD389 (lacY-ftsH317-his6-myc) (B) were treated with 0 (lanes 2 and 4) or 0.24 (lanes 1 and 3) mg/ml DSP at 4°C for 1 h as indicated. Immunoprecipitates with anti-FtsH or anti-Myc were subjected to SDS–PAGE after reduction with 2-mercaptoethanol. Proteins in the DSP-treated samples were electrophoresed slightly more slowly than those in the untreated samples because of modification by DSP.

Interaction of LacY-FtsH with HflKC

We examined whether LacY-FtsH-His6-Myc can interact with HflKC. Membranes prepared from cells expressing FtsH-His6-Myc or LacY-FtsH-His6-Myc were solubilized with NP-40 and subjected to Ni-NTA affinity chromatography. As shown previously (Kihara et al., 1996), HflKC was co-eluted with FtsH-His6-Myc using imidazole (data not shown). In contrast, LacY-FtsH-His6-Myc brought down essentially no HflKC (data not shown). Thus, LacY-FtsH-His6-Myc is defective in its interaction with HflKC, confirming our previous findings that the periplasmic region of FtsH is important for the association between FtsH and HflKC (Akiyama et al., 1998b).

Complementation activities

Expression of the lacY-ftsH-his6-myc gene from a plasmid did not rescue the growth of AR3317 [the ftsH1(Ts) mutant] at 42°C or that of AK525 (carrying zgj-525::IS1A; Kihara et al., 1995) at 20°C, whereas expression of ftsH-his6-myc did (data not shown). The lack of complementation was not due to a harmful effect of LacY-FtsH-His6-Myc on cell growth, since growth of neither AR3319 (ftsH1 sfhC21) cells nor AR3291 (ΔftsH3::kan sfhC21) cells was affected by LacY-FtsH at any temperature. Thus, although LacY-FtsH-His6-Myc is functional in degrading SecY and σ32, it cannot carry out all the biological roles of FtsH.

Discussion

FtsH is similar to other E.coli ATP-dependent proteases in that it is multimeric, but is unique in that it is membrane integrated (Gottesman et al., 1997). The membrane localization may be related to its involvement in membrane protein degradation, while the multimeric structure per se is required for the catalytic mechanism of the AAA ATPase (Karata et al., 1999). The dual role of the N-terminal region in multimerization and membrane association makes it difficult to analyze these structural features separately. In this study, we overcame this difficulty by replacing the N-terminal region of FtsH with a domain of other proteins that functions specifically for either multimerization or membrane association.

It was found that the isolated cytoplasmic domain of FtsH was virtually inactive and that the addition of the leucine zipper sequence strikingly stimulated the proteolytic activity against σ32. The oligomerization domain of the λ CI protein had a similar ability when N-terminally fused to FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc (our unpublished results). Gel filtration and cross-linking experiments showed that the leucine zipper sequence indeed induced multimerization of FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc. These results suggest that the proteolytic activity of FtsH requires multimerization. The importance of the multimerization for the ATPase and protease activities of FtsH has also been suggested from the studies of MBP–FtsH fusions (Makino et al., 1999). In addition, it has been shown that Yta10 and Yta12, FtsH homologs in S.cerevisiae, form a (hetero-)oligomer before they are able to function (Arlt et al., 1996).

Zip-FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc is at least dimeric in vitro. A dimer could be the minimum functional unit of FtsH. Recently, the crystal structure of the D2 domain, one of the two AAA cassettes of N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor (NSF), was determined (Yu et al., 1998). Based on the structure of D2, Ogura and colleagues (Karata et al., 1999) proposed that Arg315 in the conserved region (SRH region) of FtsH participates in the formation of the ATPase active site between the neighboring subunits. The leucine zipper-mediated dimerization may activate the cytoplasmic domains of FtsH by allowing them to form a functional ATPase active site. We consider a further possibility that dimerization of FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc induces higher order multimerization through interaction of the cytoplasmic domain (see below for the cytoplasmic interaction of FtsH). Self-compartmentalization is a common feature of multimeric ATP-dependent proteases (De Mot et al., 1999).

FtsH41 and LacY-FtsH41 acted in a dominant-negative manner against FtsH and LacY-FtsH, respectively. Sequestration of the substrate (σ32) by the ATPase-defective proteins is insignificant since the dominant effects were combination specific; neither mutant protein affected degradation of σ32 that was mediated by the active form of the other protein. Such effects can be explained by sequestration of the wild-type proteins by the respective mutant forms. Taken together with the results of the cross-linking experiments, it is likely that the LacY-FtsH molecules form homo-oligomers. Since LacY is monomeric (Sahin-Tóth et al., 1994), it is unlikely that its TM1–TM2 region self-associates. The oligomerization of LacY-FtsH-His6-Myc could be mediated by its cytoplasmic domain. The monomeric state of FtsH(ΔTM) suggests that such an interaction, if any, is weak and it alone is insufficient to form a functional oligomer. In the case of LacY-FtsH, the self-interaction of the cytoplasmic domain may be aided by the tethering to the membrane. Thus, increased local concentration and restricted movement favor the association. We propose that the cytoplasmic interaction is an intrinsic property of the AAA domain of FtsH. The precise region of interaction could be identified by the sites of intragenic suppressors against the dominant effect of LacY-FtsH.

LacY-FtsH-His6-Myc has an important difference from Zip-FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc in that it is able to degrade a membrane protein. Thus, multimerization is crucial for proteolytic activity of FtsH but insufficient for degradation of membrane proteins. It is conceivable that membrane localization results in the correct positioning of the active site relative to a substrate, and hence enables proteolysis of the membrane protein. TM segments of FtsH could interact with those of substrate membrane proteins during the degradation process. However, efficient degradation of SecY and YccA-(P3)-PhoA-His6-Myc by LacY-FtsH-His6-Myc suggests that no specific primary sequence is required for the TM segments of FtsH. Thus, such an interaction, if any, may be of a more general kind, such as a hydrophobic interaction. LacY-FtsH-His6-Myc and FtsH-His6-Myc degraded YccA-(P3)-PhoA-His6-Myc in an essentially identical fashion; when the PhoA domain of the fusion was tightly folded, a characteristic degradation product designated as I60 was generated, whereas the fusion protein with the unfolded PhoA domain was totally degraded without any stable intermediates. According to our previous model (Kihara et al., 1999), these results suggest that LacY-FtsH-His6-Myc is capable of dislocating the extracytoplasmic domains of YccA. Our present finding, that the putative dislocation process does not require specific primary sequences in TM segments, raises an interesting question as to what might comprise the channel for dislocation. For instance, the FtsH TM segments may form a channel-like structure that is induced by the interaction in the cytoplasmic domain of FtsH. Alternatively, a channel may be formed by other membrane proteins, such as SecYEG.

Although LacY-FtsH-His6-Myc was almost as functional as FtsH-His6-Myc in degradation of σ32 and SecY, it lacked the complementation activity against the ftsH mutations. LacY-FtsH-His6-Myc may have defects in efficient degradation of a subset of substrates including LpxC that is critical for cell viability (Ogura et al., 1999).

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains and media

Escherichia coli K12 derivatives AD21 (cya283/F′lacIq) (Akiyama and Ito, 1985), TYE024 (ompT::kan/F′lacIq) (Akiyama et al., 1995) and AK525 (zgj-525::IS1A) (Kihara et al., 1995) were described previously. Isogenic strains AR3307 (ftsH+, sfhC+), AR3317 (ftsH1, sfhC+), AR3289 (ftsH+, sfhC21), AR3319 (ftsH1, sfhC21) and AR3291 (ΔftsH3::kan, sfhC21) were also described previously (Ogura et al., 1999). AR5090 (ΔftsH3::kan, sfhC21/F′lacIq) was a gift of K.Karata and T.Ogura. The sfhC21 mutation is a suppressor of the ΔftsH3::kan mutation (Ogura et al., 1999).

L medium (Davis, 1980) and M9 medium (Silhavy et al., 1984) were used. Ampicillin (50 µg/ml) and/or chloramphenicol (20 or 100 µg/ml) were added for growing plasmid-bearing strains.

Plasmids

Plasmids used in this study are listed in Table I. For construction of pSTD219, a HindIII site was first introduced into the immediate 3′ region of the second TM segment of FtsH (on pSTD178; Akiyama et al., 1995) using a primer (CGCCGCCCTGCAAGCTTTGACGCATGA) (Kunkel et al., 1987). Then, a HindIII–SacI fragment of the resulting plasmid, encoding the cytoplasmic region of FtsH-His6-Myc, was cloned into pUC119. pSTD348 was constructed as follows. An EcoRI–AccI fragment of a pT7-5/lacY cassette (a gift of H.R.Kaback, DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession No. X56095) was inserted into BamHI-digested pSTD113 (Akiyama et al., 1995) after treatment with T4 DNA polymerase. From the resulting plasmid, the region between the LacY N-terminal region (from the N-terminus to the second TM segment) and the cytoplasmic domain of FtsH was deleted using the Quick change mutagenesis kit (Strategene) and a pair of primers (CCGCTGTTTGGTCTGCTTTCTCG TCAAATGCAGGGCGGCGG and CCGCCGCCCTGCATTTGACG AGAAAGCAGACCAAACAGCGG). pSTD350 was constructed by replacing an XbaI–MluI fragment of pSTD120 with an XbaI–MluI fragment of pSTD348. pSTD430 was constructed by cloning the KpnI fragment of pT18-zip (Karimova et al., 1998) into HindIII-digested pSTD219 after treatment with T4 DNA polymerase. pSTD310 was constructed by deleting the upstream region of envZ-ftsH-his6-myc on pSTD117 (Akiyama et al., 1995) by site-directed mutagenesis using the Quick change mutagenesis kit and a pair of primers (GAAACA GCTATGACCATGAGGCGATTGCGC and GAAACAGCTATGA CCATGAGGCGATTGCGC) to place the envZ-ftsH-his6-myc gene under the control of the lac promoter. The ftsH317 mutation (causing a His417 to Tyr change) was first introduced into the ftsH gene on pSTD401 (Akiyama et al., 1995) using the Quick change mutagenesis kit with a pair of primers (GAATCGACGGCTTACTACGAAGCGGGTC and GACCCGCTTCGTAGTAAGCCGTCGATTC). The resulting plasmid was designated pSTD314. Other plasmids carrying the ftsH317 mutation were constructed by replacing an appropriate fragment of each plasmid by a corresponding fragment from pSTD314. The ftsH41 mutation was transferred similarly from pSTD41 (Akiyama et al., 1994). All of the mutagenized genes were confirmed by DNA sequencing. pSTD423 was constructed by replacing the BsgI–SphI fragment of pKH412 by a corresponding fragment of pTY7 (Sone et al., 1998). pMW119H (Akiyama et al., 1998b) and pTYE007B were constructed by self-ligation of HindIII-digested pMW119 (Nippon Gene) or BamHI-digested pTYE007 (Akiyama et al., 1995) after treatment with T4 DNA polymerase, respectively.

Table I. Plasmids used in this study.

| Plasmid | Cloned gene | Vector (replicon) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| pSTD113 | ftsH-his6-myc | pTYE007 [pBlueScript II SK(–)] | Akiyama et al. (1995) |

| pSTD120 | ftsH-his6-myc | pMW119 (pSC101) | Akiyama et al. (1995) |

| pSTD319 | ftsH317-his6-myc | pMW119 | this study |

| pSTD401 | ftsH | pHSG575 (pSC101) | Akiyama et al. (1995) |

| pSTD405 | ftsH41 | pSTV28 (pACYC184) | this study |

| pSTD219 | ftsH(ΔTM)-his6-myc | pUC119 | this study |

| pSTD430 | zip-ftsH(ΔTM)-his6-myc | pUC119 | this study |

| pSTD432 | zip-ftsH317(ΔTM)-his6-myc | pUC119 | this study |

| pSTD444 | zip-ftsH41(ΔTM)-his6-myc | pUC119 | this study |

| pSTD348 | lacY-ftsH-his6-myc | pTYE007 | this study |

| pSTD350 | lacY-ftsH-his6-myc | pMW119 | this study |

| pSTD389 | lacY-ftsH317-his6-myc | pMW119 | this study |

| pSTD393 | lacY-ftsH | pSTV28 | this study |

| pSTD406 | lacY-ftsH41 | pSTV28 | this study |

| pSTD310 | envZ-ftsH-his6-myc | pTYE007 | this study |

| pKY248 | secY | pKY238 (pACYC184) | Taura et al. (1993) |

| pKH412 | yccA-(P3)-phoA-his6-myc | pSTV29 (pACYC184) | Kihara et al. (1999) |

| pSTD423 | yccA-(P3)-phoA(SSSS)-his6-myc | pSTV29 | this study |

| pMW119H | – | pMW119 | Akiyama et al. (1998) |

| pTYE007B | – | pTYE007 | this study |

Immunoblot examination of protein stability in vivo

Cells were grown in L broth at 30 or 37°C to mid-log phase and induced with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for 2 h, and a portion of the cultures (containing ∼3 × 107 cells) was removed and mixed with the same volume of 10% trichloroacetic acid. Denatured proteins were collected by centrifugation, dissolved in SDS sample buffer (Laemmli, 1970) and separated on a 10% acrylamide gel (for FtsH and σ32) (Laemmli, 1970) or 16.1% acrylamide–0.12% N,N′-methylene-bis-acrylamide gel (for SecY) (Akiyama and Ito, 1985). They were then detected by immunoblotting with anti-FtsH (Akiyama et al., 1998a), anti-Myc (A-14) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), anti-σ32 (a gift of M.Kanemori) or anti-SecY (Shimoike et al., 1995) antibodies. Visualization and quantification were done by means of an ECL detection kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) and a Fuji LAS1000 lumino-image analyzer.

Pulse–chase examination of protein stability in vivo

Cells were induced with 1 mM IPTG and 5 mM cAMP for 2 h, pulse-labeled with [35S]methionine, and chased with unlabeled methionine as described previously (Akiyama et al., 1995), except that the growth temperature was 28°C in the experiments described in Figure 6 to minimize the DegP-mediated degradation of unfolded PhoA (Spiess et al., 1999). YccA-(P3)-PhoA-His6-Myc, YccA-(P3)-PhoA(SSSS)-His6-Myc, σ32 and SecY were immunoprecipitated essentially as described previously (Akiyama et al., 1995) and separated by 10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Labeled proteins were visualized and quantified by means of a Fuji BAS2000 imaging analyzer.

Purification of FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc and Zip-FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc

Cells of TYE024/pSTD219 and TYE024/pSTD430 were grown at 30°C in 1 l of L medium containing 1 mM IPTG and 1 mM cAMP for 3 h. Cells were harvested, washed with wash buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.1 and 10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol), suspended in buffer A (10 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.1, 300 mM KCl, 20 mM imidazole, 10% glycerol, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and 10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol) and disrupted by French press (at 8000 p.s.i.). Samples were centrifuged (Beckman 70Ti rotor, 38 000 r.p.m. for 1 h), and supernatants were applied to an Ni-NTA agarose column, which was washed with buffer A and eluted with a linear gradient of 20–500 mM imidazole in buffer A. The peak fractions of FtsH, as detected by SDS–PAGE and Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining, were pooled and dialyzed against buffer B (20 mM HEPES–KOH pH 7.5, 50 mM KCl, 10% glycerol, 5 mM MgCl2 and 10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol).

Cross-linking experiments

FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc and Zip-FtsH(ΔTM)-His6-Myc preparations (in buffer B) were treated with the indicated concentrations of DSP (dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide) at 4°C for 1 h. DSP was then quenched with 0.75 M ammonium acetate, and proteins were precipitated with 5% trichloroacetic acid. They were dissolved in SDS sample buffer with or without 10% 2-mercaptoethanol and analyzed by 6% SDS–PAGE followed by Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining.

Cross-linking of labeled crude membranes was carried out as described previously (Akiyama et al., 1995). Briefly, cells of AD21/pSTD401/pSTD113 and AD21/pSTD393/pSTD389 were grown in M9 medium, induced and pulse-labeled with [35S]methionine. After cell disruption by sonication, membrane fractions were prepared and treated with 0.24 mg/ml DSP. Proteins were solubilized in SDS and immunoprecipitated with anti-FtsH or anti-Myc antibodies. Immunoprecipitates were analyzed by 10% SDS–PAGE after cleavage of the cross-linkage with 2-mercaptoethanol.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank K.Karata and T.Ogura for bacterial strains, M.Kanemori for anti-σ32, H.R.Kaback for the pT7-5/lacY cassette, A.Kihara, S.Chiba, N.Saikawa and H.Mori for discussion, and T.Yabe, Y.Shimizu and K.Mochizuki for technical assistance. This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture, Japan and from CREST, Japan Science and Technology Corporation.

References

- Akiyama Y. (1999) Self-processing of FtsH and its implication for the cleavage specificity of this protease. Biochemistry, 38, 11693–11699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama Y. and Ito,K. (1985) The SecY membrane component of the bacterial protein export machinery: analysis by new electrophoretic methods for integral membrane proteins. EMBO J., 4, 3351–3356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama Y., Shirai,Y. and Ito,K. (1994) Involvement of FtsH in protein assembly into and through the membrane. II. Dominant mutations affecting FtsH functions. J. Biol. Chem., 269, 5225–5229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama Y., Yoshihisa,T. and Ito,K. (1995) FtsH, a membrane-bound ATPase, forms a complex in the cytoplasmic membrane of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem., 270, 23485–23490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama Y., Kihara,A. and Ito,K. (1996a) Subunit a of proton ATPase F0 sector is a substrate of the FtsH protease in Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett., 399, 26–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama Y., Kihara,A., Tokuda,H. and Ito,K. (1996b) FtsH (HflB) is an ATP-dependent protease selectively acting on SecY and some other membrane proteins. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 31196–31201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama Y., Ehrmann,M., Kihara,A. and Ito,K. (1998a) Polypeptide-binding of Escherichia coli FtsH (HflB). Mol. Microbiol., 28, 803–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama Y., Kihara,A., Mori,H., Ogura,T. and Ito,K. (1998b) Roles of the periplasmic domain of Escherichia coli FtsH (HflB) in protein interactions and activity modulation. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 22326–22333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arlt H., Tauer,R., Feldmann,H., Neupert,W. and Langer,T. (1996) The YTA10-12 complex, an AAA protease with chaperone-like activity in the inner membrane of mitochondria. Cell, 85, 875–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calamia J. and Manoil,C. (1990) lac permease of Escherichia coli: topology and sequence elements promoting membrane insertion. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 87, 4937–4941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis R.W., Botstein,D. and Roth,J.R. (1980) Advanced Bacterial Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- De Mot R., Nagy,I., Walz,J. and Baumeiste,W. (1999) Proteasomes and other self-compartmentalizing proteases in prokaryotes. Trends Microbiol., 7, 88–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forst S., Comeau,D., Norioka,S. and Inouye,M. (1987) Localization and membrane topology of EnvZ, a protein involved in osmoregulation of OmpF and OmpC in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem., 262, 16433–16438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottesman S., Wickner,S. and Maurizi,M.R. (1997) Protein quality control: triage by chaperones and proteases. Genes Dev., 11, 815–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karata K., Inagawa,T., Wilkinson,A.J., Tatsuta,T. and Ogura,T. (1999) Dissecting the role of a conserved motif (the second region of homology) in the AAA family of ATPase. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 26225–26232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimova G., Pidoux,J., Ullmann,A. and Ladant,D. (1998) A bacterial two-hybrid system based on a reconstituted signal transduction pathway. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 5752–5756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kihara A., Akiyama,Y. and Ito,K. (1995) FtsH is required for proteolytic elimination of uncomplexed forms of SecY, an essential protein translocase subunit. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 92, 4532–4536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kihara A., Akiyama,Y. and Ito,K. (1996) A protease complex in the Escherichia coli plasma membrane: HflKC (HflA) forms a complex with FtsH (HflB), regulating its proteolytic activity against SecY. EMBO J., 15, 6122–6131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kihara A., Akiyama,Y. and Ito,K. (1998) Differential pathways for protein degradation by the FtsH/HflKC membrane-embedded protease complex: an implication from the interference by a mutant form of a new substrate protein, YccA. J. Mol. Biol., 279, 175–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kihara A., Akiyama,Y. and Ito,K. (1999) Dislocation of membrane proteins in FtsH-mediated proteolysis. EMBO J., 18, 2970–2981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunkel T.A., Roberts,J.D. and Zakour,R.A. (1987) Rapid and efficient site-specific mutagenesis without phenotypic selection. Methods Enzymol., 154, 367–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli U.K. (1970) Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature, 227, 680–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino S.-i. et al. (1999) Second transmembrane segment of FtsH plays a role in its proteolytic activity and homo-oligomerization. FEBS Lett., 460, 554–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogura T. et al. (1999) Balanced biosynthesis of major membrane components through regulated degradation of the committed enzyme of lipid A biosynthesis by the AAA protease FtsH (HflB) in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol., 31, 833–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahin-Tóth M., Lawrence,M.C. and Kaback,H.R. (1994) Properties of permease dimer, a fusion protein containing two lactose permease molecules from Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 91, 5421–5425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimoike T., Taura,T., Kihara,A., Yoshihisa,T., Akiyama,Y., Cannon,K. and Ito,K. (1995) Product of a new gene, syd, functionally interacts with SecY when overproduced in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem., 270, 5519–5526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silhavy T.J., Berman,M.L. and Enquist,L.W. (1984) Experiments with Gene Fusions. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Sone M., Akiyama,Y. and Ito,K. (1998) Additions and corrections to differential in vivo roles played by DsbA and DsbC in the formation of protein disulfide bonds. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 27756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiess C., Beil,A. and Ehrmann,M. (1999) A temperature-dependent switch from chaperone to protease in a widely conserved heat shock protein. Cell, 97, 339–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taura T., Baba,T., Akiyama,Y. and Ito,K. (1993) Determinants of the quantity of the stable SecY complex in the Escherichia coli cell. J. Bacteriol., 175, 7771–7775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomoyasu T., Yamanaka,K., Murata,K., Suzaki,T., Bouloc,P., Kato,A., Niki,H., Hiraga,S. and Ogura,T. (1993a) Topology and subcellular localization of FtsH protein in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol., 175, 1352–1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomoyasu T., Yuki,T., Morimura,S., Mori,H., Yamanaka,K., Niki,H., Hiraga,S. and Ogura,T. (1993b) The Escherichia coli FtsH protein is a prokaryotic member of a protein family of putative ATPases involved in membrane functions, cell cycle control and gene expression. J. Bacteriol., 175, 1344–1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu R.C., Hanson,P.I., Jahn,R. and Brünger,A.T. (1998) Structure of the ATP-dependent oligomerization domain of N-ethylmaleimide sensitive factor complexed with ATP. Nature Struct. Biol., 5, 803–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]