1. Introduction

Human papillomaviruses (HPVs) are small DNA tumor viruses of approximately 8kb that infect both cutaneous and mucosal epithelia [1]. Currently, more than 100 different HPV types have been identified and it is well recognized that a specific subset are the etiological agents of cervical cancer. Globally, cervical cancer is the second largest cause of female cancer mortality [2]. Successful development and implementation of prophylactic virus-like particle (VLP) vaccines has resulted in protection against the two most common “high risk” HPV types, 16 and 18 [3]. However, the neutralizing antibody protection provided by VLP vaccination is type specific and non-therapeutic [4]. Induction of cell mediated immunity is necessary for eradication of established HPV disease [5], [6].

Papillomaviruses (PVs) are species and tissue specific [7] and there are currently no PV types that naturally infect laboratory strains of small rodents [8]. Rabbit, dog, and bovine models are the only preclinical animal models of natural PV infection. The cottontail rabbit papillomavirus (CRPV)/rabbit model offers several advantages for studying host immunity induced during a natural PV infection. CRPV infections mimic several characteristics of high-risk HPV infections [9] and the CRPV/rabbit model has been used extensively to test the protective immunity elicited by VLP-based vaccines [10], [11] as well as the cell-mediated immunity generated to viral proteins E1, E2, E6, E7, E8 and L1 [12], [13], [14], [15]. A second benefit of this model is that CRPV DNA is infectious and can initiate papillomas in the absence of genome encapisidation [16], [17] thereby bypassing induction of a humoral immune response elicited to the capsid proteins.

Recent establishment of an HLA-A2.1 transgenic rabbit model provides an added useful resource for the assessment of vaccine induced protective immunity to HPV epitopes during natural PV infections [18]. Our studies have demonstrated that the HLA-A2.1 transgenic rabbit model is capable of producing strong protective and therapeutic immune responses to computer-predicted HLA-A2.1-restricted epitopes from the CRPVE1 gene in vivo [19]. Additional studies with this preclinical model have verified that HLA-A2.1 transgenic rabbits are able to generate strong cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) responses to the well known HPV16E7 82-90 epitope [20] and this in vivo immunity is protective [21].

Papillomavirus proteins are expressed from initial infection throughout progression to cancer and provide potential prophylactic and therapeutic targets for vaccination. Previous studies have demonstrated that both the E7 gene and its protein are essential for papilloma outgrowth in rabbits [22] while the L2 protein is dispensable [23]. In these studies we embedded the well known HLA-A2.1-restricted HPV16E7 82-90 epitope in both the L2 gene and E7 gene of CRPV using two alternative methods. Both new CRPV genomes were able to produce papillomas confirming earlier studies [24] that there are areas of plasticity within the CRPV genome. We next examined the DNA vaccine induced protective immunity elicited to the HPV16E7 82-90 epitope embedded in these two CRPV genes. Expression of the 82-90 epitope within the L2 and E7 proteins resulted in increased protection of the epitope-vaccinated HLA-A2.1 transgenic rabbits compared to control rabbits after DNA viral challenge. These data indicate that protective immunity can be triggered to an embedded HPV epitope expressed within both an early protein and a late protein of the CRPV.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. DNA Vaccine

The HPV16E7/82-90 DNA vaccine was designed with five repeats of the single epitope separated by alanine-alanine-tyrosine (AAY) spacers [20], [25]. An N-terminus Kozak sequence, followed by a universal tetanus toxoid (TT) T-helper motif [26], and a C-terminus Ubiquitin motif were also included in the synthetic sequence as described earlier [19]. The entire vaccine sequence was then cloned into the pCX expression vector. The finished vaccine products were designated HPV16E7/82-90 epitope vaccine and control vector vaccine, respectively. All DNA vaccines were adjusted to a plasmid concentration of 1ug/ml in 1XTE. The DNA was then precipitated onto 1.6um-diamter gold particles at a ratio of 1ug of DNA/0.5mg of gold particles as described by the manufacturer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, California)

2.2. Viral DNA Challenge Constructs

H.CRPV construct cloned into a pUC19 vector at the SalI site as previously described was used as wild type CRPV [17]. A subclone of the CRPV E7 gene was subjected to site directed mutagenesis to insert the HPV16E7 82-90 (LLMGTLGIV) sequence in frame into the CRPV E7 gene just upstream of the E7 stop codon. Primer sequences used for this single step mutagenesis can be found in table I. A modified CRPV E7 gene containing 9 additional amino acids at the carboxy-terminus was produced and confirmed by DNA sequence analysis. The modified CRPV E7 gene was then cloned into the H.CRPV construct at the EcorI and ClaI sites creating CRPV/E7ins82-90 and this was confirmed by DNA sequence analysis. To create the CRPV/L2sub82-90 genome, a subclone containing the L2 gene of CRPV inserted in the pUC19 vector was subjected to multiple rounds of PCR mutagenesis. Primer pairs for each successive site-directed mutagenic PCR can be found in table I. This allowed for incremental changes in the nucleotide coding sequence between nucleotides 447 and 474 of the L2 gene. Upon confirmation of all the necessary codon changes via DNA sequence analysis, the new L2 gene fragment containing the HPV16E7 82-90 epitope sequence was cloned into the H.CRPV construct at SalI and AgeI sites creating the new CRPV genome. Viral DNA plasmids were isolated and purified using the Qiagen maxiprep plasmid isolation kit and subjected to cesium chloride density gradient centrifugation. Plasmid concentration was adjusted to 200ng/ml in 1X TE

Table I.

Primer sequences for site-directed mutagenesis. Primer sequences are listed in pairs with the forward primer first followed by the reverse compliment primer sequence. Sequences in bold represent single nucleotide changes while underlined sequences represent inserted nucleotides.

| Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|

| L2A L2B |

5’-AGCCAGATTTCAGACCTCACAACTGGTACATTCGGCACAGTGTCCAGAACACACATT-3’ 5’-AATGTGTGTTCTGGACACTGTGCCGAATGTACCAGTTGTGAGGTCTGAAATCTGGCT-3’ |

| L2C L2D |

5’-AGCCAGATTTCAGACCTCCCAACTGGTACACTCGGCACCGTGTCCAGAACACACATT-3’ 5’-AATGTGTGTTCTGGACACGGTGCCGAGTGTACCAGTTGGGAGGTCTGAAATCTGGCT-3’ |

| L2E L2F |

5’-AGCCAGATTTCAGACCTGCCAATTGGTACACTCGGCATCGTGTCCAGAACACACATT-3’ 5’-AATGTGTGTTCTGGACACGATGCCGAGTGTACCAATTGGCAGGTCTGAAATCTGGCT-3’ |

| L2G L2H |

5’-AGCCAGATTTCAGACCTGCTAATGGGTACACTCGGCATCGTGTCCAGAACACACATT-3’ 5’-AATGTGTGTTCTGGACACGATGCCGAGTGTACCCATTAGCAGGTCTGAAATCTGGCT-3’ |

| E7A E7B |

5’- GCCCGGAGTGTTGTAACCTGCTGATGGGCACCCTGGGCATCGTGTGAAAATGGCTGAAGGTACAGACC-3’ 5’- GGTCTGTACCTTCAGCCATTTTCACACGATGCCCAGGGTGCCCATCAGCAGGTTACAACACTCCGGGC-3’ |

2.3. Rabbit Vaccination and Viral DNA Challenge

HLA-A2.1 transgenic outbred rabbits were maintained in the Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine animal facility while non-transgenic outbred rabbits were purchased from Covance Research Products, Inc. All animal care and handling procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Rabbits were divided into groups and were vaccinated three times at three-week intervals with either the HPV16E7/82-90 vaccine or the control vector. The inner ear skin of each sedated rabbit was cleaned with 70% ethanol and then barraged with DNA coated gold particles at a rate of 400lb/in2 by a helium driven gene gun [27]. Each rabbit received a vaccine dose of 20ug at each immunization. Four days following the final booster rabbit backs were shaved and scarified as described [27]. One week after the final booster vaccination, rabbits were challenged with wild type CRPV DNA, CRPV/E7ins82-90 DNA, or CRPv/L2sub82-90 DNA at a dose of 10ug/site in a 50ul volume.

2.4. Papilloma Volume Determination and Statistical Analysis

Papilloma size was calculated as described previously [19]. Briefly, the product of length x width x height in millimeters of individual papillomas was calculated to determine geometric mean diameter (GMD). Measurements were gathered weekly starting 3 weeks after viral DNA challenge. Unpaired t-test comparisons were used to decide statistical significance. The protection rates were calculated as previously described [21] and statistical significance was determined by Fishers exact test.

3. Results

3.1. Two modified CRPV DNA genomes produced papillomas in New Zealand White rabbits

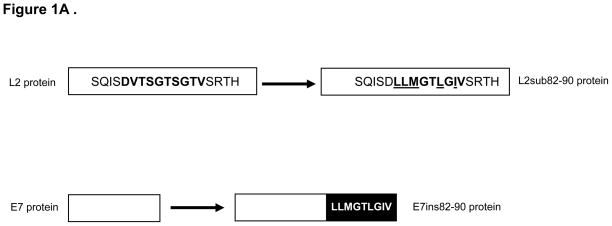

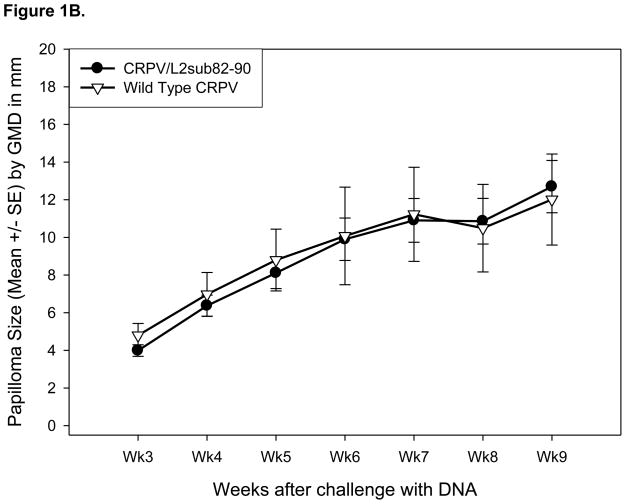

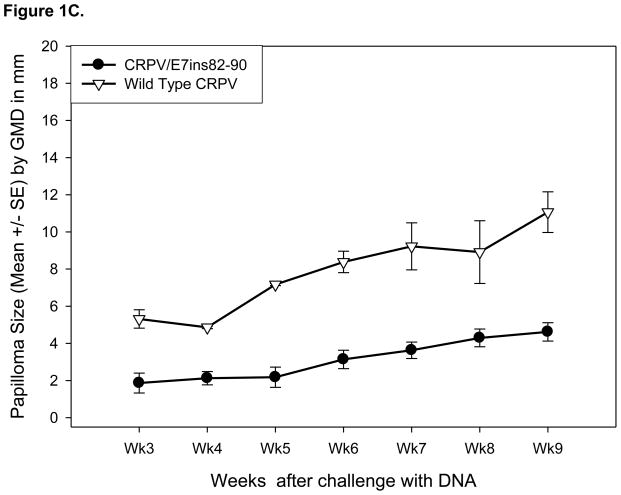

Previously, our laboratory demonstrated that the CRPV genome can undergo PCR-induced modification without loss of functional viability [23]. We have effectively performed epitope relocation via substitution of HPV16E7 82-90 into the CRPV E7 gene [21]. Here we created two additional modified CRPV genomes, CRPV/L2sub82-90 and CRPV/E7ins82-90, using two different methods to embed the epitope. To determine the substitution position of the epitope within the CRPV L2 gene, a protein sequence alignment was performed. Limited success with relocation of additional epitopes within the CRPV E7 gene led to the insertion method being used to relocate the 82-90 epitope to the carboxy-terminus of the CRPV E7 protein (Figure 1A). Following genome alteration, each CRPV construct was assayed for its capacity to induce papillomas. Two New Zealand White rabbits were challenged with 10ug/site of wild type CRPV DNA and each new modified CRPV genome DNA. Papilloma formation was considered a positive functional result. Papillomas appeared on the backs of rabbits 3 weeks after challenge with CRPV/L2sub82-90 DNA (Table II) and these papillomas grew at a similar rate to those papillomas induced by wild type CRPV DNA (Figure 1B). Three weeks after challenge with CRPV/E7ins82-90 DNA small papillomas appeared on the backs of the rabbits (Figure 1C and Table II). These papillomas were smaller in size and exhibited a slower growth rate compared to papillomas resulting from wild type CRPV DNA challenge, but persisted throughout the entire viability study.

Figure 1.

Modified CRPV genomes form papillomas in New Zealand White rabbits. Diagram illustrating the L2 and E7 proteins of CRPV before and after the CRPV genes underwent PCR mutagenesis to substitute or insert the HPV16E7 82-90 epitope, respectively (A). Papilloma GMDs from New Zealand White rabbits challenged with CRPV/L2sub82-90 DNA and wild type CRPV DNA (B). Papilloma GMDs from New Zealand White rabbits challenged with CRPV/E7ins82-90 DNA and wild type CRPV DNA (C).

Table II.

Papilloma formation on the backs of NZW rabbits challenged with 10ug/site with Wild Type (WT) CRPV DNA and either CRPV/L2sub82-90 or CRPV/E7ins82-90 DNA.

| Sites with papillomas | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Rabbits | Challenge sites/rabbit | WT CRPV (2 sites/rabbit) | CRPV/L2sub82-90 (8 sites/rabbit) | CRPV/E7ins82-90 (4 sites/rabbit) |

| 2 | 10 | 4/4 | 16/16 | 0/0 |

| 2 | 6 | 4/4 | 0/0 | 8/8 |

3.2. HLA-A2.1 transgenic rabbits receiving DNA vaccine are partially protected from challenge with the modified CRPV genome containing the HPV16E7 82-90 epitope substituted in the L2 gene

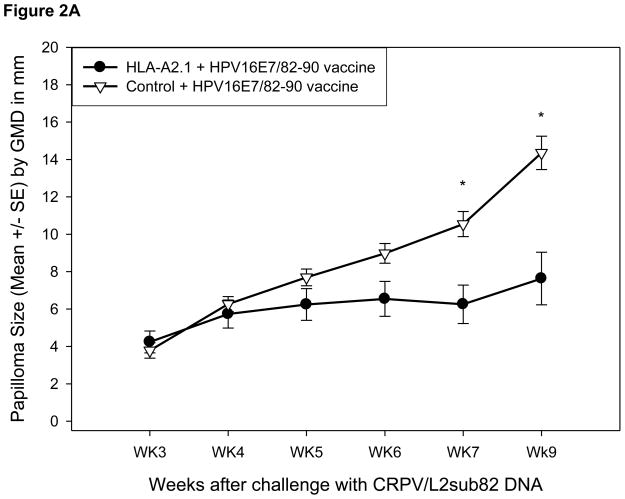

Specific immunity to the HLA-A2.1-restricted HPV16E7 82-90 epitope expressed within the CRPV E7 protein can be stimulated in the HLA-A2.1 transgenic rabbit model upon DNA vaccination [21]. We performed the following experiment to determine if this epitope specific immunity can target the same epitope when it is expressed in the CRPV L2 protein. HLA-A2.1 transgenic (N = 4) and control (N = 3) rabbits received three immunizations with the HPV16E7/82-90 epitope DNA vaccine or control vector vaccine at three-week intervals. One week following the final booster vaccination, each rabbit was challenged with wild-type CRPV DNA at two sites and CRPV/L2sub82-90 DNA at six sites. No statistically significant difference was observed in protection rates between the HLA-A2.1 transgenic rabbits and control rabbits immunized with the HPV16E7/82-90 epitope vaccine or control vaccine, respectively (Table III and IV). However, a statistically significant reduction in mean papilloma size was observed in HLA-A2.1 transgenic rabbits vaccinated with the epitope DNA vaccine followed by challenge with the modified CRPV genome (Figure 2A). As expected there was no difference in mean papilloma size in HLA-A2.1 transgenic or control rabbits receiving the HPV16E7/82-90 epitope vaccine that were subsequently challenged with wild type CRPV DNA (Figure 2B).

Table III.

Tumor protection in outbred New Zealand White rabbits challenged with CRPV DNA containing the HPV16E7 82-90 epitope substituted in the L2 gene after three immunizations with either the HPV16E7/82-90 epitope vaccine or the control vector vaccine.

| Rabbits | Vaccine | Challenged Sites | Protection Ratea (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | HLA-A2.1 (N = 4) | E7 Epitope | 24 | 4/24 (17%)b,c,d |

| 2 | Control (N = 3) | E7 Epitope | 18 | 0/18 (0%) |

| 3 | HLA-A2.1 (N = 4) | Vector | 24 | 2/24 (8%) |

| 4 | Control (N = 3) | Vector | 18 | 0/18 (0%) |

Protection rate, papilloma-free sites/challenge sites (six sites/each construct/each rabbit);

p = 0.14,

p = 0.67,

p = 0.14 vs group 2, group 3, and group 4, respectively, Fisher’s exact test.

Table IV.

Tumor protection in outbred New Zealand White rabbits challenged with wild type CRPV DNA after three immunizations with either the HPV16E7/82-90 epitope vaccine or the control vector vaccine.

| Rabbits | Vaccine | Challenged Sites | Protection Ratea (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | HLA-A2.1 (N = 4) | E7 Epitope | 8 | 0/8 (0%)b,c,d |

| 2 | Control (N = 3) | E7 Epitope | 6 | 0/6 (0%) |

| 3 | HLA-A2.1 (N = 4) | Vector | 8 | 3/8 (38%) |

| 4 | Control (N = 3) | Vector | 6 | 0/6 (0%) |

Protection rate, papilloma-free sites/challenge sites (two sites/each construct/each rabbit);

p = 1,

p = 0.23,

p = 1 vs group 2, group 3, and group 4, respectively, Fisher’s exact test.

Figure 2.

Papilloma outgrowth in epitope DNA vaccinated outbred HLA-A2.1 transgenic and control rabbits after viral DNA challenge. HLA-A2.1 transgenic and control rabbits immunized three times with the HPV16E7/82-90 epitope DNA vaccine were challenged with CRPV/L2sub82-90 DNA (A) and wild type (B) CRPV DNA. Significantly smaller papillomas were found on HLA-A2.1 transgenic rabbits immunized with the E7 epitope vaccine and challenged with the epitope-modified CRPV DNA construct (p< 0.01, unpaired student’s t-test).

3.3. DNA vaccination imparts complete protection against infection with the modified CRPV genome containing the HPV16E7 82-90 epitope inserted in the E7 gene

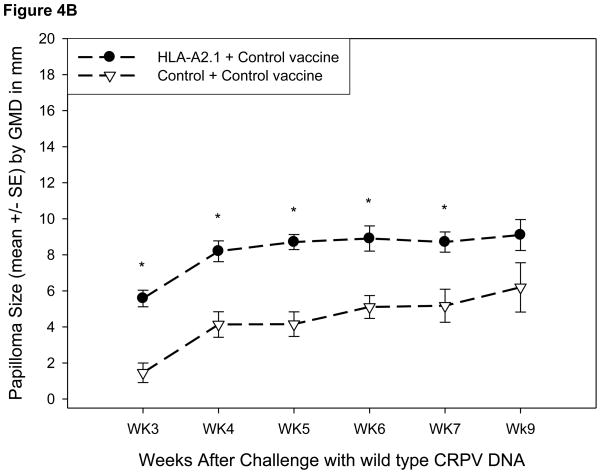

The protection induced by the HPV16E7/82-90 epitope vaccine against a modified CRPV genome containing the 82-90 epitope expressed at the end of the E7 protein was then tested. HLA-A2.1 transgenic and control rabbits were vaccinated three times with the HPV16E7/82-90 epitope vaccine or control vector vaccine as described above. The animals were challenged at two sites with wild type CRPV DNA and at six sites with CRPV/E7ins82-90 DNA one week later. HLA-A2.1 transgenic rabbits immunized with the epitope vaccine were completely protected against challenge with the modified CRPV genome (Table V) and unexpectedly showed partial protection from challenge with wild type CRPV DNA (Table VI). Additionally, the mean papilloma size on the HLA-A2.1 rabbits receiving the epitope vaccine was significantly smaller for both CRPV DNA genomes compared to the control rabbits (Figure 3A and 3B). In contrast, the protection rates were not statistically significant for control rabbits receiving either the epitope or control vaccines followed by challenge with wild type CRPV DNA or CRPV/E7ins 82-90 DNA (Table V and VI). Early after infection, there was a statistically significant difference in mean papilloma size between the HLA-A2.1 and control rabbits receiving the control vector vaccine followed by challenge with either CRPV genome (Figure 4A and 4B). Examination of the data revealed that papillomas resulting from challenge with either genome were slow to develop on these three control rabbits receiving the vector vaccine.

Table V.

Tumor protection in outbred New Zealand White rabbits challenged with CRPV DNA containing the HPV16E7 82-90 epitope inserted in the E7 gene after three immunizations with either the HPV16E7/82-90 epitope vaccine or the control vector vaccine.

| Rabbits | Vaccine | Challenged Sites | Protection Ratea (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | HLA-A2.1 (N = 3) | E7 Epitope | 18 | 18/18 (100%)b,c,d |

| 2 | Control (N = 3) | E7 Epitope | 18 | 1/18 (6%) |

| 3 | HLA-A2.1 (N = 4) | Vector | 24 | 7/24 (26%) |

| 4 | Control (N = 3) | Vector | 18 | 5/18 (28%) |

Protection rate, papilloma-free sites/challenge sites (six sites/each construct/each rabbit);

p = 0.0009,

p = 0.025,

p = 0.054 vs group 2, group 3, and group 4, respectively, Fisher’s exact test.

Table VI.

Tumor protection in outbred New Zealand White rabbits challenged with wild type CRPV DNA after three immunizations with the HPV16E7/82-90 epitope vaccine or the control vector vaccine.

| Rabbits | Vaccine | Challenged Sites | Protection Ratea (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | HLA-A2.1 (N = 3) | E7 Epitope | 6 | 5/6 (83%)b,c,d |

| 2 | Control (N = 3) | E7 Epitope | 6 | 0/6 (0%) |

| 3 | HLA-A2.1 (N = 4) | Vector | 8 | 0/8 (0%) |

| 4 | Control (N = 3) | Vector | 6 | 0/6 (0%) |

Protection rate, papilloma-free sites/challenge sites (two sites/each construct/each rabbit);

p = 0.10,

p = 0.04,

p = 0.10 vs group 2, group 3, and group 4, respectively, Fisher’s exact test.

Figure 3.

Papilloma outgrowth in epitope DNA vaccinated outbred HLA-A2.1 transgenic and control rabbits after viral DNA challenge. HLA-A2.1 transgenic and control rabbits immunized three times with the HPV16E7/82-90 epitope vaccine were challenged with CRPV/E7ins82-90 DNA (A) and wild type (B) CRPV DNA. Significantly smaller papillomas were found on all HLA-A2.1 transgenic rabbits immunized with the E7 epitope vaccine (p< 0.01, unpaired student’s t-test).

Figure 4.

Papilloma outgrowth in epitope DNA vaccinated outbred HLA-A2.1 transgenic and control rabbits after viral DNA challenge. HLA-A2.1 transgenic and control rabbits immunized three times with the control vector vaccine were challenged with CRPV/E7ins82-90 DNA (A) and wild type (B) CRPV DNA. Significantly smaller papillomas were found on all control rabbits immunized with the control vector vaccine (p< 0.01, unpaired student’s t-test).

3.4. Specific protective immunity induced in HLA-A2.1 transgenic rabbits following DNA vaccination with the HPV16E7/82-90 epitope vaccine

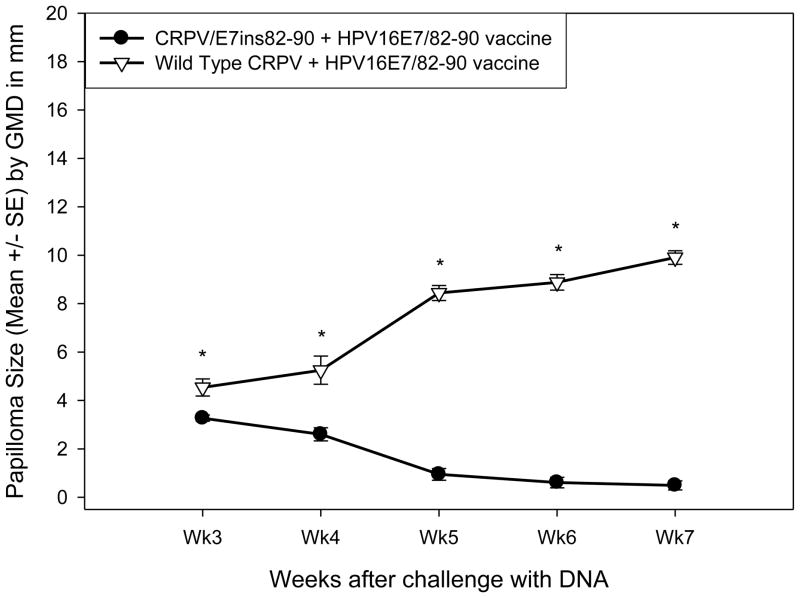

In the above experiment, rabbits were simultaneously challenged with wild type CRPV DNA and the modified CRPV/E7ins82-90 DNA. To demonstrate that the protective immunity stimulated in the HLA-A2.1 transgenic rabbits immunized with the HPV16E7/82-90 epitope vaccine was specific for the epitope expressed at the end of the E7 protein, in the context of the full CRPV genome, an additional experiment was conducted. Two groups of HLA-A2.1 transgenic rabbits were vaccinated three times at three-week intervals with the HPV16E7/82-90 epitope vaccine. One week after the final immunization, the animals were challenged with either CRPVE7ins82-90 DNA (N = 3) only or wild type CRPV DNA (N = 2) only. Near complete protection was observed in HLA-A2.1 transgenic rabbits challenged with the CRPV/E7ins82-90 DNA (Table VII). The mean papilloma size of the papillomas that did manifest was significantly smaller in these HLA-A2.1 transgenic rabbits (Figure 5).

Table VII.

Tumor protection in outbred New Zealand White rabbits challenged with CRPV DNA containing the HPV16E7 82-90 epitope inserted in the E7 gene or wild-type CRPV DNA after three immunizations with the HPV16E7/82-90 epitope DNA vaccine.

| Rabbits | DNA | Challenged Sites | Protection Ratea (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | HLA-A2.1 (N = 2) | WT CRPV | 16 | 0/16 (0%)b |

| 2 | HLA-A2.1 (N = 3) | E7 Ins 82 | 24 | 19/24 (79%) |

Protection rate, papilloma-free sites/challenge sites (eight sites/each construct/each rabbit);

p = 0.001 vs group 2, Fisher’s exact test.

Figure 5.

Papilloma outgrowth in epitope DNA vaccinated outbred HLA-A2.1 transgenic rabbits after viral DNA challenge. HLA-A2.1 transgenic rabbits immunized three times with the HPV16E7/82-90 epitope vaccine were challenged with CRPV/E7ins82-90 DNA or wild type CRPV DNA. Significantly smaller papillomas were found on HLA-A2.1 transgenic rabbits immunized with the E7 epitope vaccine and challenged with the epitope-modified CRPV DNA construct (p< 0.01, unpaired student’s t-test).

4. Discussion

In this report we have used the novel HLA-A2.1 transgenic rabbit model to study the vaccine induced protective immunity generated against the HLA-A2.1-restricted HPV16E7 82-90 epitope after challenge with modified CRPV DNA genomes containing this same epitope expressed from the L2 protein or the E7 protein. The HPV16E7/82-90 epitope vaccine elicited protective immunity that effectively targeted the 82-90 epitope embedded via substitution in the CRPVL2 gene or via insertion in the CRPV E7 gene. These data indicate that both early and late proteins of papillomaviruses can be targeted by epitope-specific immunity and that the E7 protein is a superior protein target. A previously published report from our laboratory has demonstrated that HLA-A2.1 transgenic rabbits receiving the HPV16E7/82-90 epitope vaccine can effectively mount an epitope-specific CTL response against a CRPV viral DNA genome containing this epitope substituted within the E7 gene [21]. A second series of studies indicated that the HLA-A2.1 transgenic rabbit model could be used to screen the immunogenicity of computer-predicted HLA-A2.1-restricted epitopes and test their protective and therapeutic immunity in vivo [19]. Collectively, these data highlight the versatility of the HLA-A2.1 transgenic rabbit model system for testing various immunological aspects of vaccine generated protective immunity.

CRPV DNA is infectious and can induce papillomas in the CRPV rabbit model system [28], [17]. This infection method presumably bypasses induction of humoral immunity to the major and minor capsid proteins, L1 and L2, respectively. Additionally, the CRPV genome can be subjected to a range of PCR-induced mutagenesis events without jeopardizing its functional viability [24]. Finally, our laboratory has shown that domestic rabbits are permissive for CRPV and can be used to study the entire virus life cycle in vivo [29]. These features allowed us to examine the vaccine-induced epitope-specific protective immunity generated against the HLA-A2.1-restricted HPV16E7 82-90 epitope when the epitope is expressed in either a late protein or at the end of an early protein of CRPV. The L2 protein of CRPV is not necessary for papilloma formation in rabbits, [23] and as expected substitution of the 82-90 epitope within the CRPV L2 gene did not compromise the ability of the modified genome to form papillomas in rabbits. Furthermore, the protective immune response generated after DNA vaccination to an epitope expressed within the L2 protein has yet to be examined for in vivo protection. For these reasons we chose to determine if epitope-specific protective immunity induced through DNA vaccination with the HPV16E7 82-90 epitope could target this epitope expressed in the CRPV L2 protein. The results of the first vaccine study suggests that epitopes embedded in the L2 gene and expressed at late time points during a natural papillomavirus infection are viable targets for cell-mediated immunity. Experimental vaccination with L2 peptides [30] and L2 fusion proteins [31] induce L2 specific antibodies that are capable of neutralizing divergent PV types. Further studies to determine if HPV L2 proteins contain any cross-protective T cell epitopes could prove useful for additional immunity generated by broadly-protective prophylactic HPV L2-based vaccines.

The E7 gene of CRPV and its protein product are essential for papilloma formation in rabbits [22]. Attempts to create new genomes with a variety of other HLA-A2.1-restricted HPV16E7 epitopes embedded in the CRPV E7 gene using the substitution method were unsuccessful (unpublished data). This mutagenesis method relies on sequence similarity between the epitope and protein target of choice. To overcome these challenges we chose to employ an insertion method for embedding epitopes within the CRPV E7 gene, essentially creating epitope tags. Insertion of the HPV16E7 82-90 epitope within the E7 gene just upstream of the stop codon resulted in a viable genome. In addition, this site is permissive for insertion of other HLA-A2.1-restricted HPV16 E7 epitopes (unpublished data). However, a reduction in growth rate of the CRPV/E7ins82-90 genome when compared to wild type CRPV was observed. Previous studies have demonstrated that alteration of the codon sequence of the CRPV E7 gene can affect the growth rate and in vivo immunogenicity of the new CRPV genome [37]. The viability study for the CRPV/E7ins82-90 genome was carried out in unvaccinated rabbits, suggesting the reduction in observed growth rate was not due to an altered immune response to the modified genome but most likely due to altered functionality of the CRPV E7 protein in vivo.

Gene gun mediated DNA vaccination with the HPV16E7/82-90 epitope vaccine generated powerful protective immunity in the HLA-A2.1 transgenic rabbits. However, regression of papillomas resulting from challenge with both CRPV/E7ins82-90 DNA and wild type CRPV DNA was observed on epitope vaccinated HLA-A2.1 transgenic rabbits. This second vaccination study suggested that the protective immunity induced by the HPV16E7/82-90 DNA vaccine was not exclusively epitope specific. Additionally, the reduction in mean papilloma size observed in the control rabbits vaccinated with the control vector vaccine followed by challenge with either CRPV genome suggested that the vector is not neutral immunologically.

A limitation of the first study with the CRPV/E7ins82-90 genome was the fact that rabbits were challenged with both the epitope-modified and wild type CRPV genomes simultaneously. Therefore, we were only able to determine that the HPV16/E7 82-90 epitope vaccine elicited a strong protective immune response in the HLA-A2.1 transgenic rabbits. To ascertain if this immune response was epitope specific a second study was performed. The results of this third protection study demonstrated that the protective immunity elicited by epitope vaccination of the HLA-A2.1 transgenic rabbits was specific for the HPV16E7 82-90 epitope. The unexpected results obtained in the first protection experiment with the CRPV/E7ins82-90 genome may be due to a phenomenon known as bystander T cell activation. Previous studies have shown that bystander T cells may become activated by viruses and oligonucleotides containing CpG motifs in vivo thereby up-regulating certain surface markers and undergoing proliferation [32], [33]. Additionally, LPS, type I interferons secreted by dendritic cells, and interferon-gamma secreted by NK cells can induce activation of bystander T cells in vitro [34]. DNA vaccines produced in bacteria are known to contain CpG motifs that can have immunostimulatory effects in vivo [35]. Furthermore, our laboratory has demonstrated that the HLA-A2.1 transgenic rabbit model has an increased low level of natural immunity to CRPV infections as compared to non-transgenic rabbits [18]. Finally, the early proteins E6, E7, E1 and E2 are initially expressed in the infected basal layer of epithelial cells providing T cells greater access to naturally occurring as well as vaccine specific epitopes at the base of the papilloma [36]. Consequently, the initial vaccination event with a DNA vaccine containing CpG motifs followed by challenge with the CRPV viral DNA, and continuous access of epitope specific as well as heterologous T cells to foreign antigens may have created a multi-epitoped-targeted immune storm.

We contend that the initial immunity induced by the HPV16E7/82-90 DNA vaccine was specific for the epitope. This epitope-specific activation was followed by bystander activation of heterologous T cells leading to spreading immunity to other naturally occurring epitopes that are HLA-A2.1-restricted and shared by both CRPV genomes. In support of this hypothesis, our laboratory has demonstrated that powerful protective and therapeutic immunity to native HLA-A2.1-restricted CRPV E1 epitopes can be generated [19] and that these CRPV E1 epitopes may have been additional targets for the spreading immunity. However, such spreading immunity was only seen in rabbits challenged with the CRPV/E7ins82-90 genome. This observation could result from the facts that the L2 protein is not expressed until later in the viral life cycle and is typically expressed in the upper layers of the epithelium [36]. Thus, there would be less time and less exposure of the epitope specific T cells for their specific antigen and the immune environment therefore, would not be as conducive for bystander T cell activation.

Our experiments have demonstrated that the CRPV genome contains areas of plasticity that are amendable to modification without loss of genome viability. Additionally, we have shown that an HPV16 E7 epitope embedded in the L2 gene or the E7 gene of CRPV can be targeted by DNA vaccine induced immunity. However, the E7 protein provides a superior target over the L2 protein as the HLA-A2.1 transgenic rabbits receiving the epitope vaccine showed significant levels of protection against challenge with the CRPV/E7ins82-90 genome compared to those challenged with the CRPV/L2sub82-90 genome. Together these data demonstrate that the CRPV/HLA-A2.1 transgenic rabbit model is a useful and versatile tool to explore various facets of vaccine generated immunity in a model of natural papillomavirus infection.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Public Health Service, National Cancer Institute Grant R01 CA47622 from the National Institutes of Health and by the Jake Gittlen Memorial Golf Tournament.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Nicholls PK, Stanley MA. The immunology of animal papillomaviruses. Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology. 2000;73(2):101–27. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2427(99)00165-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.zur Hausen H. Papillomaviruses in the causation of human cancers - a brief historical account. Virology. 2009;384(2):260–5. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campo MS, Roden RBS. Papillomavirus Prophylactic Vaccines: Established Successes, New Approaches. Journal of Virology. 2010;84(3):1214–20. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01927-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lowy DR, Schiller JT. Prophylactic human papillomavirus vaccines. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2006;116(5):1167–73. doi: 10.1172/JCI28607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nicholls PK, Moore PF, Anderson DM, et al. Regression of canine oral papillomas is associated with infiltration of CD4+and CD8+lymphocytes. Virology. 2001;283(1):31–9. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Selvakumar R, Schmitt A, Iftner T, Ahmed R, Wettstein FO. Regression of papillomas induced by cottontail rabbit papillomavirus is associated with infiltration of CD8+ cells and persistence of viral DNA after regression. Journal of Virology. 1997;71(7):5540–8. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.5540-5548.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campo MS. Animal models of papillomavirus pathogenesis. Virus Research. 2002;89(2):249–61. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(02)00193-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christensen ND. Cottontail rabbit papillomavirus (CRPV) model system to test antiviral and immunotherapeutic strategies. Antiviral Chemistry & Chemotherapy. 2005;16:355–62. doi: 10.1177/095632020501600602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christensen ND, Pickel MD, Budgeon LR, Kreider JW. In vivo anti-papillomavirus activity of nucleoside analogues including cidofovir on CRPV-induced rabbit papillomas. Antiviral Research. 2000;48(2):131–42. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(00)00124-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Breitburd F, Kirnbauer R, Hubbert NL, et al. Immunization with Virus-Like Particles from Cottontail Rabbit Papillomavirus (Crpv) Can Protect Against Experimental Crpv Infection. Journal of Virology. 1995;69(6):3959–63. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3959-3963.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christensen ND, Reed CA, Cladel NM, Han R, Kreider JW. Immunization with viruslike particles induces long-term protection of rabbits against challenge with cottontail rabbit papillomavirus. Journal of Virology. 1996;70(2):960–5. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.960-965.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Han R, Reed CA, Cladel NM, Christensen ND. Intramuscular injection of plasmid DNA encoding cottontail rabbit papillomavirus E1, E2, E6 and E7 induces T cell–mediated but not humoral immune responses in rabbits. Vaccine. 1999;17(11–12):1558–66. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)00356-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Han R, Reed CA, Cladel NM, Christensen ND. Immunization of rabbits with cottontail rabbit papillomavirus E1 and E2 genes: protective immunity induced by gene gun-mediated intracutaneous delivery but not by intramuscular injection. Vaccine. 2000;18(26):2937–44. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00110-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu JF, Han RC, Cladel NM, Pickel MD, Christensen ND. Intracutaneous DNA vaccination with the E8 gene of cottontail rabbit papillomavirus induces protective immunity against virus challenge in rabbits. Journal of Virology. 2002;76(13):6453–9. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.13.6453-6459.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu J, Cladel NM, Budgeon LR, Reed CA, Pickel MD, Christensen ND. Protective cell-mediated immunity by DNA vaccination against papillomavirus L1 capsid protein in the cottontail rabbit papillomavirus model. Viral Immunology. 2006;19(3):492–507. doi: 10.1089/vim.2006.19.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brandsma JL, Xiao W. Infectious Virus-Replication in Papillomas Induced by Molecularly Cloned Cottontail Rabbit Papillomavirus Dna. Journal of Virology. 1993;67(1):567–71. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.1.567-571.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kreider JW, Cladel NM, Patrick SD, et al. High-Efficiency Induction of Papillomas In-Vivo Using Recombinant Cottontail Rabbit Papillomavirus Dna. Journal of Virological Methods. 1995;55(2):233–44. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(95)00062-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu JF, Peng XW, Budgeon LR, Cladel NM, Balogh KK, Christensen ND. Establishment of a cottontail rabbit papillomavirus/HLA-A2.1 transgenic rabbit model. Journal of Virology. 2007;81(13):7171–7. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00200-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu JF, Cladel N, Peng XW, Balogh K, Christensen ND. Protective immunity with an E1 multivalent epitope DNA vaccine against cottontail rabbit papillomavirus (CRPV) infection in an HLA-A2.1 transgenic rabbit model. Vaccine. 2008;26(6):809–16. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.11.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kast WM, Brandt RMP, Drijfhout JW, Melief CJM. Human-Leukocyte Antigen-A2.1 Restricted Candidate Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte Epitopes of Human Papillomavirus Type-16 E6-Protein and E7-Protein Identified by Using the Processing-Defective Human Cell Line-T2. Journal of Immunotherapy. 1993;14(2):115–20. doi: 10.1097/00002371-199308000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu JF, Peng XW, Schell TD, Budgeon LR, Cladel NM, Christensen ND. An HLA-A2.1-transgenic rabbit model to study immunity to papillomavirus infection. Journal of Immunology. 2006;177(11):8037–45. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.11.8037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu X, Xiao W, Brandsma JL. Papilloma Formation by Cottontail Rabbit Papillomavirus Requires E1 and E2 Regulatory Genes in Addition to E6 and E7 Transforming Genes. Journal of Virology. 1994;68(9):6097–102. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.6097-6102.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nasseri M, Meyers C, Wettstein FO. Genetic-Analysis of Crpv Pathogenesis - the L1 Open Reading Frame Is Dispensable for Cellular-Transformation But Is Required for Papilloma Formation. Virology. 1989;170(1):321–5. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90388-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu JF, Cladel NM, Balogh K, Budgeon L, Christensen ND. Impact of genetic changes to the CRPV genome and their application to the study of pathogenesis in vivo. Virology. 2007;358(2):384–90. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.08.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Velders MP, Weijzen S, Eiben GL, et al. Defined flanking spacers and enhanced proteolysis is essential for eradication of established tumors by an epitope string DNA vaccine. Journal of Immunology. 2001;166(9):5366–73. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.9.5366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Daftarian P, Ali S, Sharan R, et al. Immunization with Th-CTL fusion peptide and cytosine-phosphate-guanine DNA in transgenic HLA-A2 mice induces recognition of HIV-infected T cells and clears vaccinia virus challenge. Journal of Immunology. 2003;171(8):4028–39. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.8.4028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cladel NM, Hu J, Balogh K, Mejia A, Christensen ND. Wounding prior to challenge substantially improves infectivity of cottontail rabbit papillomavirus and allows for standardization of infection. Journal of Virological Methods. 2008;148(1–2):34–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brandsma JL, Yang ZH, Barthold SW, Johnson EA. Use of A Rapid, Efficient Inoculation Method to Induce Papillomas by Cottontail Rabbit Papillomavirus Dna Shows That the E7 Gene Is Required. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1991;88(11):4816–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.11.4816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu J, Budgeon L, Cladel N, Culp T, Balogh K, Christensen ND. Detection of L1, infectious virions and anti-L1 antibody in domestic rabbits infected with cottontail rabbit papillomavirus. Journal of General Virology. 2007;88(12):3286–93. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82879-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gambhira R, Jagu S, Karanam B, et al. Protection of rabbits against challenge with rabbit papillomaviruses by immunization with the N terminus of human papillomavirus type 16 minor capsid antigen L2. Journal of Virology. 2007;81(21):11585–92. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01577-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gambhira R, Gravitt PE, Bossis I, Stern PL, Viscidi RP, Roden RBS. Vaccination of healthy volunteers with human papillomavirus type 16 L2E7E6 fusion protein induces serum antibody that neutralizes across papillomavirus species. Cancer Research. 2006;66(23):11120–4. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tough DF, Borrow P, Sprent J. Induction of bystander T cell proliferation by viruses and type I interferon in vivo. Science. 1996;272(5270):1947–50. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5270.1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sun S, Zhang X, Touch DF, Sprent J. Type I interferon-mediated stimulation of T cells by CpG DNA. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1998;188(12):2335–42. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.12.2335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kamath AT, Sheasby CE, Tough DF. Dendritic cells and NK cells stimulate bystander T cell activation in response to TLR agonists through secretion of IFN-alpha beta and IFN-gamma. Journal of Immunology. 2005;174(2):767–76. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klinman DM, Yamshchikov G, Ishigatsubo Y. Contribution of CpG motifs to the immunogenicity of DNA vaccines. Journal of Immunology. 1997;158(8):3635–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Doorbar J. The papillomavirus life cycle. Journal of Clinical Virology. 2005;32:S7–S15. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cladel NM, Hu JF, Balogh KK, Christensen ND. CRPV Genomes with Synonymous Codon Optimizations in the CRPV E7 Gene Show Phenotypic Differences in Growth and Altered Immunity upon E7 Vaccination. PLoS One. 2008;3(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]