Abstract

J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich).

Adiponectin, a protein secreted by adipose tissue, has anti‐inflammatory, antithrombogenic, and antidiabetogenic effects. Lower plasma adiponectin levels are present in diabetes, obesity, and the metabolic syndrome. Adiponectin levels are higher in women compared with men. The purpose of this study was to determine whether there is a relationship between total adiponectin, or the molecular weight fractions of adiponectin, and testosterone levels in African American men and premenopausal women. A sample (N=48) of men and premenopausal women was selected based on high and low serum‐free testosterone level. All patients had data on blood pressure, metabolic risk factors, and sex hormone levels. Stored plasma samples were assayed for total adiponectin. Molecular weight fractions of adiponectin were separated by gel electrophoresis and quantified by Western blot. Data analysis compared adiponectin (total and fractions) levels with androgen status in both sexes. Among men with high testosterone levels, all fractions of adiponectin were significantly lower than those in men with low testosterone (P<.05). In women with high testosterone, total adiponectin (P=.02) and all fractions of molecular weight adiponectin (P<.05) were lower compared with those in women with low testosterone. Plasma adiponectin levels are lower in both men and premenopausal women with relatively higher testosterone levels. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2010;12:957–963. © 2010 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Adipose tissue is known to secrete many active hormones, including leptin, plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1, resistin, tumor necrosis factor α, and interleukin 6, all of which are inflammatory cytokines. Adipocytes also secrete adiponectin, which has anti‐inflammatory effects. 1 , 2 , 3 In humans, plasma adiponectin concentration negatively correlates with body mass index (BMI) and insulin resistance and is lower in patients with type 2 diabetes. 4 , 5 , 6 , 7

Although adiponectin is secreted by fat cells, obese patients have significantly lower levels of adiponectin compared with nonobese individuals. 8 , 9 , 10 It has also been shown that women have higher plasma adiponectin levels than men, despite having a relatively greater percentage of body fat. Kern and colleagues 11 reported that plasma adiponectin levels in women are 65% higher than in men, especially in relatively lean individuals. Reports from other clinical studies describe similar results, with lower mean adiponectin levels in men compared with women. 9 , 12 Bottner and colleagues 13 examined adiponectin levels in children and adolescents and reported that a decrease of plasma adiponectin level occurs at puberty in boys, and the decrease in adiponectin is related to an increase in androgen levels. Therefore, androgens appear to contribute to the sex differences in plasma adiponectin concentration.

Adiponectin is composed of a collagen‐like motif at the N‐terminus, a C1q‐like globular domain at the C‐terminus, and a 20‐residue signal sequence. 14 , 15 The concentration of adiponectin in humans is between 3 μg/mL and 30 μg/mL. Adiponectin functions in forms of multimers in the body including trimer (low molecular weight complexes [LMW]), hexamers (medium molecular weight complexes [MMW]), and multimers (high molecular weight complexes [HMW]). 16 A previous study reported significantly higher total adiponectin and also higher HMW adiponectin levels in women than in men. 17 It has been suggested that the HMW fraction of adiponectin is the biologic active form. Basu and colleagues 18 reported that the HMW adiponectin level was lower in type 2 diabetic patients than in nondiabetics and the HMW adiponectin level in diabetic patients increased following a hypocaloric diet. Among obese Japanese adolescents, HMW adiponectin had a stronger negative correlation with obesity than total adiponectin. 19

These reports suggest that plasma total adiponectin levels and molecular weight fractions of adiponectin may be modified in men by testosterone level. The purpose of this study was to determine whether there is an inverse relationship of plasma total adiponectin concentration or specific molecular weight components of adiponectin with androgen status, based on free testosterone level, among both women and men in a sample of young adult African Americans.

Patients and Methods

Participants for this study were selected from a previous large clinical investigation designed to examine relationships of androgen status and metabolic risk factors, including prediabetes, dyslipidemia, and the metabolic syndrome in young adult African Americans. 20 , 21 This project was approved by the institutional review board of Thomas Jefferson University, and written informed consent was obtained for each participant enrolled in the project. Young adult African Americans aged 28 to 33 years were initially examined between 1994 and 1999. Exclusion criteria at the time of initial enrollment included known type 1 and 2 diabetes, polycystic ovarian syndrome, and chronic kidney disease. The study was conducted to investigate blood pressure (BP) and cardiovascular risk factors and included measures of metabolic risk factors, including insulin resistance. Androgen status was ascertained by plasma levels of sex hormone–binding globulin, free testosterone, and estradiol. Participants were re‐enrolled between August 2001 and July 2007 for a study to investigate longitudinal change in risk factor status. Individuals who developed type 2 diabetes subsequent to the initial enrollment were not excluded from re‐enrollment. The initial and repeat clinical reassessment included anthropometric data, BP, lipid levels, oral glucose tolerance test, and insulin sensitivity measured by an insulin clamp. Plasma, free testosterone, and plasma estradiol were measured again in the second study.

To create a sample of high androgen and low androgen cases, the free testosterone levels, measured at the second study between 2001 to 2007, for all 300 patients in the entire cohort were rank‐ordered from highest to lowest in men separately and in women separately. For men and women separately, the cases were stratified by tertiles. We then used available residual plasma samples (stored at −80°C) on patients in the upper and lower tertiles of the testosterone ranking for assay of total adiponectin and adiponectin isoforms. The stored plasma samples that were used to assay adiponectin and adiponectin isoforms were the same plasma samples in which free testosterone had been assayed. Samples from patients in the middle tertile were not used. The cutoff for high testosterone in men was ≥10 pg/mL and in women was ≥1 pg/mL.

Measurement of Serum Adiponectin and Sex Hormones

Adiponectin was measured by a quantitative sandwich enzyme immunoassay using a commercially available kit. The minimum detectable concentration of adiponectin was 0.246 ng/mL. Free testosterone and estradiol were measured by radioimmunoassay using commercial kits.

Measurement of Molecular Weight Fractions of Adiponectin

To quantify different molecular weight fractions of adiponectin, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis was performed according to standard Laemmli method. Sample buffer for nonreducing condition contained 3% SDS, 50 mmol/L Tris‐HCl pH6.8, and 10% glycerol, but without 2‐mercaptoethanol. Aliquot of 0.7 μL human serum was diluted in 9.6 μL H2O, mixed with 10 μL of 2× sample buffer, was subjected to 3% to 8% Tris Acetate gradient gel under nonreducing and nonheating denaturing conditions. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were incubated in 1× blocking buffer containing 5% non‐fat milk, 10 mmol/L Tris, 100 mmol/L NaCl, and 0.1% polysorbate 20, then incubated with 1:1000 diluted mouse monoclonal adiponectin antibody in blocking buffer at 4°C overnight. Visualization of bound antibodies was performed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies and then enhanced chemiluminescence, exposure to x‐ray film, and quantification using the Image Station 440CF (Kodak, Rochester, NY) (Figure). Internal standards were applied on all gels. For quantification, the gel result was scanned into the Image Station 440CF. The light intensity of each band was measured. Mean intensity was recorded and used for all calculations. Based on the intensity of the band, the proportions (%) of HMW, MMW, and LMW adiponectin were calculated for each patient. Using the serum adiponectin value for each patient, values (in μg/mL) for each of the 3 molecular weights of adiponectin were inferred.

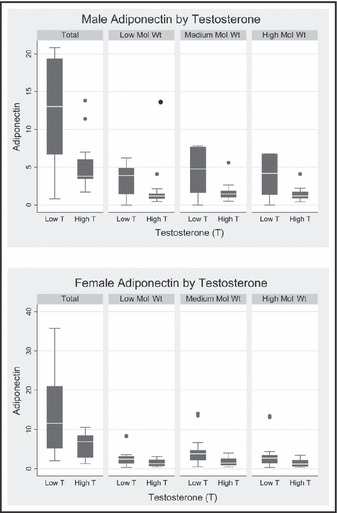

Figure.

Median and interquartile range of different molecular weight fractions of adiponectin are presented for the low and high testosterone groups for each sex. In men, the median values of total and different molecular weight fractions of adiponectin in the low testosterone group were significantly higher than the high testosterone group (P<.05). In women, the median values of total and medium molecular weight adiponectin were significantly higher in the low testosterone group (P<.05). Mol Wt indicates molecular weight.

Statistical Analysis

Summary statistics were calculated for patient characteristics by sex. Men and women were stratified into high and low androgen groups based on their free testosterone levels. Due to the selection of cases, continuous variables had largely skewed distributions. Therefore, baseline characteristics of the patients are reported as mean and standard deviation, but the Wilcoxon test was used for significance testing. The variables of free testosterone, total adiponectin, and molecular weight subfractions of adiponectin were analyzed and recorded as geometric means and 95% confidence intervals. Differences in total adiponectin and differences between the different molecular weight fractions of adiponectin in each sex and testosterone group were also compared by Wilcoxon test. A P value ≤.05 was considered significant. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, INC, Cary, NC).

Results

The characteristics of the 4 study samples are provided in Table I. Among men, available plasma samples included 6 cases with low testosterone and 15 with high testosterone. Among women, available samples included 18 cases with low testosterone and 9 with high testosterone. Mean age (40 years) was similar in men with both high and low testosterone and women with high and low testosterone. In men, there were no significant differences between the high and low testosterone groups in BMI, weight, BP, or plasma lipids. In the high testosterone group, 5 of 15 men were obese (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) compared with 2 of 6 men in the low testosterone group. The mean fasting glucose and 2‐hour glucose (after 75‐g oral glucose tolerance test) values were higher in the men with low testosterone compared with those with high testosterone, revealing that 3 men in the low testosterone group in whom diabetes was detected compared with only 1 man who was found to have diabetes in the high testosterone group. All diabetic patients included in this study were newly diagnosed and were not taking any medication or other treatment. Compared with women in the low testosterone group, women in the high testosterone group had significantly higher BMI (P=.001), weight (P=.001), and triglyceride level (P=.031). In the high testosterone group, 8 of 9 women were obese compared with 4 of 18 women in the low testosterone group. There were no differences in BP, total cholesterol, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol, low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol, fasting glucose, or 2‐hour glucose between women with low and high testosterone levels. Two women in each testosterone group met criteria for diabetes.

Table I.

Baseline Characteristics

| Variable | Men | Women | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Testosterone (n=6) | High Testosterone (n=15) | P Value | Low Testosterone (n=18) | High Testosterone (n=9) | P Value | |

| Age, y | 42.7±2.9 | 40.7±2.7 | .169 | 41.1±3.2 | 39.8±2.9 | .394 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28.5±5.3 | 27.5±4.6 | .755 | 26.6±5.2 | 35.5±3.9 | .001 |

| Weight, kg | 91.9±17.3 | 87.5±14.9 | .533 | 70.8±15.6 | 98.2±12.6 | .001 |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 126.0±7.5 | 124.0±19.8 | .938 | 122.8±17.5 | 128.2±13.2 | .256 |

| Diastolic BP, mm Hg | 75.7±8.0 | 75.9±16.0 | .845 | 72.3±15.1 | 75.7±8.6 | .141 |

| HTN, % (No.) | 16.7 (1) | 13.3 (2) | 1.000 | 16.7 (3) | 44.4 (4) | .175 |

| HDL, pg/mL | 42.2±10.9 | 46.5±13.6 | .413 | 54.6±15.6 | 48.3±8.8 | .471 |

| LDL, pg/mL | 105.3±30.4 | 117.3±29.2 | .640 | 102.2±38.4 | 125.3±32.7 | .111 |

| Triglycerides, pg/mL | 95.5±77.6 | 85.9±39.7 | .640 | 70.6±48.2 | 96.6±40.3 | .031 |

| Total cholesterol, pg/mL | 166.7±29.1 | 181.1±30.4 | .243 | 176.4±36.9 | 192.8±35.7 | .181 |

| Fasting glucose, mg/dL | 171.0±125.0 | 104.4±8.6 | .086 | 114.4±82.7 | 105.4±13.0 | .116 |

| 2‐H glucose, mg/dLa | 175.2±86.3 | 113.9±42.5 | .127 | 120.2±34.4 | 144.0±38.7 | .284 |

| Diabetes, % (No.) | 50 (3) | 6.67 (1) | .053 | 11.11 (2) | 22.2 (2) | .58 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; HDL, high‐density lipoprotein; HTN, hypertension; LDL, low‐density lipoprotein. Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation unless otherwise indicated. aOnly 24 women and 19 men had 2‐hour glucose values available.

The values for the total adiponectin and molecular weight fractions of adiponectin in each testosterone group are provided in Table II and the Figure. There was no overlap in geometric mean and 95% confidence intervals in free testosterone levels between high testosterone and low testosterone groups in both the men and women. In men, total adiponectin was lower in the high testosterone group compared with the low testosterone group, although the difference did not reach statistical significance in the limited sample size. The absolute concentration of each molecular weight fraction of adiponectin was significantly lower in high testosterone men compared with low testosterone men (all P<.05). However, when the data were analyzed as the percent of total adiponectin, the relative contribution of each molecular weight fraction to total adiponectin were similar in the high and low testosterone men.

Table II.

Molecular Weight of Adiponectin by Testosterone Level in Men and Women

| Variable | Men | Women | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Testosterone (n=6) | High Testosterone (n=15) | P Value | Low Testosterone (n=18) | High Testosterone (n=9) | P Value | |||||

| GM | 95% CI | GM | 95% CI | GM | 95% CI | GM | 95% CI | |||

| Free testosterone, pg/mL | 5.0 | (3.7–6.7) | 16.5 | (13.6–19.9) | <.001 | 0.4 | (0.4–0.5) | 1.6 | (1.2–2.1) | <.001 |

| Total adiponectin, μg/mL | 9.0 | (2.5–32.6) | 4.4 | (3.2–6.0) | .220 | 11.0 | (7.3–16.5) | 4.8 | (2.8–8.3) | .015 |

| LMW adiponectin, μg/mL | 3.5 | (2.0–6.0) | 1.1 | (0.8–1.5) | .001 | 2.1 | (1.4–3.2) | 1.2 | (0.7–2.1) | .088 |

| MMW adiponectin, μg/mL | 4.5 | (2.5–8.3) | 1.4 | (1.1–2.0) | .003 | 3.2 | (2.1–4.9) | 1.4 | (0.8–2.5) | .047 |

| HMW adiponectin, μg/mL | 4.0 | (2.1–7.6) | 1.2 | (0.8–1.6) | .002 | 2.4 | (1.5–3.8) | 1.2 | (0.7–2.1) | .045 |

| LMW adiponectin, % | 29.0 | (26.2–32.1) | 30.4 | (29.3–31.5) | .326 | 27.4 | (26.0–28.8) | 32.2 | (31.2–33.3) | <.001 |

| MMW adiponectin, % | 37.7 | (36.1–39.4) | 38.5 | (37.6–39.5) | .309 | 41.6 | (40.2–43.0) | 37.1 | (36.2–38.1) | <.001 |

| HMW adiponectin, % | 33.1 | (30.8–35.5) | 30.9 | (29.7–32.2) | .075 | 30.6 | (28.8–32.4) | 30.6 | (29.6–31.5) | .970 |

Abbreviations: HMW, high molecular weight; LMW, low molecular weight; MMW, medium molecular weight. All values are expressed as geometric means (GM) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Among women, total adiponectin was significantly lower in the high testosterone group compared with the low testosterone group (P<.02). The geometric mean values for each of the molecular weight fractions of adiponectin were lower in women with high testosterone compared with those with low testosterone. The difference was statistically significant for the HMW fraction (P<.05) and the MMW fraction of adiponectin (P<.05). When the data were compared as a percentage of each molecular weight fraction, women with high testosterone had a higher percentage of LMW adiponectin and lower percentage of MMW adiponectin compared with women with low testosterone (P<.001), and no difference in percentage of HMW adiponectin. Although the levels of free testosterone were markedly lower in women than in men, the data demonstrate a similar relationship between testosterone and adiponectin in men and women.

Discussion

Data from this study detected an inverse relationship between androgen status, determined by free testosterone level, and plasma total adiponectin concentration in African American women with a similar trend in men. This relationship is present despite marked differences in the range of testosterone levels between men and women. When the molecular weight fractions of adiponectin were examined, the absolute level of HMW, MMW, and LMW were all significantly lower in men with high testosterone levels. Among women, the HMW fraction and MMW fraction of adiponectin was significantly lower in the women with high testosterone levels. While we did not identify a consistent relationship of different molecular weight adiponectin fractions with androgenicity, our results show a consistent inverse relationship of total adiponectin level and testosterone status in women. Although the geometric mean for total adiponectin was lower in the men with high testosterone, the difference did not reach statistical significance in this small sample of cases.

Our results are consistent with previous clinical reports in men. In healthy boys, total adiponectin levels decline with progression into puberty, in parallel with increasing endogenous androgen production. 13 Compared with healthy men, plasma total adiponectin concentration is higher in hypogonadal men and decreases following testosterone administration. 22 , 23 Total adiponectin levels decrease following testosterone administration in female‐to‐male transsexual patients. 24 Experimentally, testosterone treatment reduces plasma adiponectin concentration in mice. 25

There are limited reports on the relationships between adiponectin and androgen levels in women. Among women with polycystic ovarian syndrome, no significant negative association of plasma adiponectin level with total testosterone was detected. 26 Yasui and colleagues 27 described a significant negative relationship between plasma adiponectin concentration and testosterone in men, but found no significant relationships in postmenopausal women. Women included in our study were different from women in Yasui’s study. The average age of women in Yasui’s study was 67 years; however, women included in our study were premenopausal, with an average age of 40 years. The estrogen and testosterone levels may be significantly different between these two groups. Also, in our study, the androgen status was measured by free testosterone level, which is the active form of testosterone, compared with total testosterone in Yasui’s study.

Even less has been published on adiponectin and androgen status in African Americans. Based on data from studies in our laboratory, we previously reported that among African American women, hyperinsulinemia cosegregates with higher levels of free testosterone, 28 and premenopausal African American women with relative androgen excess have greater insulin resistance. 29 Among African American men, Haren and colleagues 30 reported that the levels of dehydroepiandrosterone, a testosterone precursor, were inversely associated with adiponectin levels. There is some evidence that total adiponectin levels are lower in African Americans compared with European Americans. 31 , 32 Lara‐Castro and colleagues 33 examined molecular weight fractions of adiponectin in African American and European premenopausal women. These investigators reported that the lower serum adiponectin levels in African American women were predominantly due to lower concentrations of LMW adiponectin and that LMW, but not HMW, adiponectin correlated with metabolic risk factors.

Adiponectin circulates in the body in 3 isoforms: LMW, MMW, and HMW adiponectin. The mechanism of conversion and regulation of different fractions of adiponectin is unclear. An in vitro study showed that testosterone selectively inhibited the secretion of HMW adiponectin from adipose tissue. 34 In patients with diabetes, thiazolidinedione treatment can increase the HMW/(HMW+LMW) ratio. 35 Previous studies report that HMW adiponectin may be the most biologic active form of adiponectin. Some reports describe stronger associations of HWM adiponectin than total adiponectin with insulin resistance, chronic inflammation, and obesity. 18 , 35 , 36 , 37 Data from our study identified a higher level of HMW adiponectin in low testosterone men compared with high testosterone men. However, among these men there were also parallel differences in the MMW and LMW fractions of adiponectin. Among low testosterone women, the HMW and MMW adiponectin fraction were significantly higher compared with the high testosterone women. While significant associations in absolute concentrations of adiponectin molecular weight fractions with testosterone status was detected in this small sample, when the adiponectin fractions were compared as percentage of total adiponectin, differences were detected only in women.

Limitations

The present study has several limitations. First, a major limitation is the very limited sample size. The cases were selected on the basis of testosterone level. Although testosterone and adiponectin were assayed on the same plasma sample, the cases that were included in this study were also limited by the stored samples that were available for adiponectin assay. Therefore, in addition to the small sample size, there could be some selection or ascertainment bias in the study groups. Second, an inverse relationship of adiponectin and BMI has been reported in several studies. 4 , 38 , 39 In our study, there was no significant difference in BMI between men with low and high testosterone levels. However, in women, BMI was higher in the high testosterone group compared with the low testosterone group. Since BMI is inversely associated with adiponectin, we cannot conclude that the differences in adiponectin levels between high and low testosterone women were due only to different testosterone levels. Finally, the patients were all African Americans, which limits generalizability. Therefore the results should be considered with caution until replicated in larger samples and in other ethnic groups.

Conclusions

Data from this study detected lower plasma adiponectin levels among both men and women with high free testosterone compared with those with low testosterone. Parallel differences in all molecular weight fractions of adiponectin were identified in men and for HMW and MMW fractions in women.

Disclosures: This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (HL051547) and the Pennsylvania Department of Public Health. The Pennsylvania Department of Health disclaims responsibility for any analyses, interpretations, or conclusions.

References

- 1. Zhang Y, Proenca R, Maffei M, et al. Positional cloning of the mouse obese gene and its human homologue. Nature. 1994;372:425–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hotamisligil GS, Shargill NS, Spiegelman BM. Adipose expression of tumor necrosis factor‐alpha: direct role in obesity‐linked insulin resistance. Science. 1993;259:87–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shimomura I, Funahashi T, Takahashi M, et al. Enhanced expression of PAI‐1 in visceral fat: possible contributor to vascular disease in obesity. Nat Med. 1996;2:800–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yamamoto Y, Hirose H, Saito I, et al. Correlation of the adipocyte‐derived protein adiponectin with insulin resistance index and serum high‐density lipoprotein‐cholesterol, independent of body mass index, in the Japanese population. Clin Sci (Lond). 2002;103:137–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hotta K, Funahashi T, Bodkin NL, et al. Circulating concentrations of the adipocyte protein adiponectin are decreased in parallel with reduced insulin sensitivity during the progression to type 2 diabetes in rhesus monkeys. Diabetes. 2001;50:1126–1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yamauchi T, Kamon J, Waki H, et al. The fat‐derived hormone adiponectin reverses insulin resistance associated with both lipoatrophy and obesity. Nat Med. 2001;7:941–946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Iwashima Y, Katsuya T, Ishikawa K, et al. Hypoadiponectinemia is an independent risk factor for hypertension. Hypertension. 2004;43:1318–1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hotta K, Funahashi T, Arita Y, et al. Plasma concentrations of a novel, adipose‐specific protein, adiponectin, in type 2 diabetic patients. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:1595–1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Arita Y, Kihara S, Ouchi N, et al. Paradoxical decrease of an adipose‐specific protein, adiponectin, in obesity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;257:79–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kumada M, Kihara S, Sumitsuji S, et al. Association of hypoadiponectinemia with coronary artery disease in men. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:85–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kern PA, Di Gregorio GB, Lu T, et al. Adiponectin expression from human adipose tissue: relation to obesity, insulin resistance, and tumor necrosis factor‐alpha expression. Diabetes. 2003;52:1779–1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cnop M, Havel PJ, Utzschneider KM, et al. Relationship of adiponectin to body fat distribution, insulin sensitivity and plasma lipoproteins: evidence for independent roles of age and sex. Diabetologia. 2003;46:459–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bottner A, Kratzsch J, Muller G, et al. Gender differences of adiponectin levels develop during the progression of puberty and are related to serum androgen levels. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:4053–4061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shapiro L, Scherer PE. The crystal structure of a complement‐1q family protein suggests an evolutionary link to tumor necrosis factor. Curr Biol. 1998;8:335–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Maeda K, Okubo K, Shimomura I, et al. Analysis of an expression profile of genes in the human adipose tissue. Gene. 1997;190:227–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Waki H, Yamauchi T, Kamon J, et al. Impaired multimerization of human adiponectin mutants associated with diabetes. Molecular structure and multimer formation of adiponectin. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:40352–40363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Aso Y, Yamamoto R, Wakabayashi S, et al. Comparison of serum high‐molecular weight (HMW) adiponectin with total adiponectin concentrations in type 2 diabetic patients with coronary artery disease using a novel enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay to detect HMW adiponectin. Diabetes. 2006;55:1954–1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Basu R, Pajvani UB, Rizza RA, et al. Selective downregulation of the high molecular weight form of adiponectin in hyperinsulinemia and in type 2 diabetes: differential regulation from nondiabetic subjects. Diabetes. 2007;56:2174–2177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Araki S, Dobashi K, Kubo K, et al. High molecular weight, rather than total, adiponectin levels better reflect metabolic abnormalities associated with childhood obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:5113–5116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Boyd‐Woschinko G, Kushner H, Falkner B. Androgen excess is associated with insulin resistance and the development of diabetes in African American women. J Cardiometab Syndr. 2007;2:254–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stein E, Kushner H, Gidding S, et al. Plasma lipid concentrations in nondiabetic African American adults: associations with insulin resistance and the metabolic syndrome. Metabolism. 2007;56:954–960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Page ST, Herbst KL, Amory JK, et al. Testosterone administration suppresses adiponectin levels in men. J Androl. 2005;26:85–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lanfranco F, Zitzmann M, Simoni M, et al. Serum adiponectin levels in hypogonadal males: influence of testosterone replacement therapy. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2004;60:500–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Berra M, Armillotta F, D’Emidio L, et al. Testosterone decreases adiponectin levels in female to male transsexuals. Asian J Androl. 2006;8:725–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nishizawa H, Shimomura I, Kishida K, et al. Androgens decrease plasma adiponectin, an insulin‐sensitizing adipocyte‐derived protein. Diabetes. 2002;51:2734–2741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sieminska L, Marek B, Kos‐Kudla B, et al. Serum adiponectin in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome and its relation to clinical, metabolic and endocrine parameters. J Endocrinol Invest. 2004;27:528–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yasui T, Tomita J, Miyatani Y, et al. Associations of adiponectin with sex hormone‐binding globulin levels in aging male and female populations. Clin Chim Acta. 2007;386:69–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Falkner B, Hulman S, Kushner H. Gender differences in insulin‐stimulated glucose utilization among African‐Americans. Am J Hypertens. 1994;7:948–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sherif K, Kushner H, Falkner BE. Sex hormone‐binding globulin and insulin resistance in African‐American women. Metabolism. 1998;47:70–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Haren MT, Banks WA, Perry Iii HM, et al. Predictors of serum testosterone and DHEAS in African‐American men. Int J Androl. 2008;31:50–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Degawa‐Yamauchi M, Dilts JR, Bovenkerk JE, et al. Lower serum adiponectin levels in African‐American boys. Obes Res. 2003;11:1384–1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hulver MW, Saleh O, MacDonald KG, et al. Ethnic differences in adiponectin levels. Metabolism. 2004;53:1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lara‐Castro C, Doud EC, Tapia PC, et al. Adiponectin multimers and metabolic syndrome traits: relative adiponectin resistance in African Americans. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2008;16:2616–2623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Xu A, Chan KW, Hoo RL, et al. Testosterone selectively reduces the high molecular weight form of adiponectin by inhibiting its secretion from adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:18073–18080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pajvani UB, Hawkins M, Combs TP, et al. Complex distribution, not absolute amount of adiponectin, correlates with thiazolidinedione‐mediated improvement in insulin sensitivity. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:12152–12162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Salani B, Briatore L, Andraghetti G, et al. High‐molecular weight adiponectin isoforms increase after biliopancreatic diversion in obese subjects. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2006;14:1511–1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kobayashi H, Ouchi N, Kihara S, et al. Selective suppression of endothelial cell apoptosis by the high molecular weight form of adiponectin. Circ Res. 2004;94:e27–e31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Weiss R, Dufour S, Groszmann A, et al. Low adiponectin levels in adolescent obesity: a marker of increased intramyocellular lipid accumulation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:2014–2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Weiss R, Dziura J, Burgert TS, et al. Obesity and the metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2362–2374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]