Abstract

Recently, we demonstrated that the LuxS-based quorum sensing (QS) system (AI-2) negatively regulated the virulence of a diarrheal isolate SSU of Aeromonas hydrophila, while the ahyRI-based (AI-1) N-acyl-homoserine lactone system was a positive regulator of bacterial virulence. Thus, these QS systems had opposing effects on modulating biofilm formation and bacterial motility in vitro models and in vivo virulence in a speticemic mouse model of infection. In this study, we linked these two QS systems with the bacterial second messenger cyclic diguanosine monophosphate (c-di-GMP) in the regulation of virulence in A. hydrophila SSU. To accomplish this, we examined the effect of overproducing a protein with GGDEF domain, which increases c-di-GMP levels in bacteria, on the phenotype and transcriptional profiling of genes involved in biofilm formation and bacterial motility in wild-type (WT) versus its QS null mutants. We provided evidence that c-di-GMP overproduction dramatically enhanced biofilm formation and reduced motility of the WT A. hydrophila SSU, which was equitable with that of the ΔluxS mutant. On the contrary, the ΔahyRI mutant exhibited only a marginal increase in the biofilm formation with no effect on motility when c-di-GMP was overproduced. Overall, our data indicated that c-di-GMP overproduction modulated transcriptional levels of genes involved in biofilm formation and motility phenotype in A. hydrophila SSU in a QS-dependent manner, involving both AI-1 and AI-2 systems.

Keywords: A. hydrophila, QS, AI-1 (ahyRI-based) QS, AI-2 (luxS-based) QS, motility, biofilm, c-di-GMP

1. INTRODUCTION

At least two modified autoinducer (AI) systems, which are known to date in other bacteria, exist in a diarrheal isolate SSU of A. hydrophila [1, 2]. One of them is the S-ribosylhomocysteinase (LuxS)-based autoinducer AI-2 system [3]. LuxS plays a major role in AI-2 synthesis, and is also an integral component of the activated methyl cycle [4]. The bacterial phenotypes that are dependent on the QS systems include surface attachment and/or biofilm formation, motility, and in vivo virulence [5–7].

Recently, we characterized the AI-2-mediated QS in A. hydrophila SSU and showed that the ΔluxS mutant formed denser biofilm in vitro, had increased virulence in a septicemic mouse model of A. hydrophila infections, and exhibited decreased motility compared to that of the wild-type (WT) bacterium [1]. However, limited information was available on the AI-1 [N-acyl-homoserine lactone (AHL)-based QS (ahyRI)] system in the regulation of bacterial virulence. Consequently, we demonstrated that several virulence traits were altered in the ΔahyRI mutant [2]. However, there are at least three ahyR homologs that exist in the genome of A. hydrophila SSU, and ahyR2 is genetically linked to the type 6 secretion system (T6SS) (unpublished data). The contribution of these three ahyR homologs in A. hydrophila SSU AI-1 QS is currently unknown.

Like QS, cyclic diguanosine monophosphate (c-di-GMP), the bacterial intracellular second messenger, has also been implicated in the regulation of cell surface properties of several bacterial species [8]. The cellular level of c-di-GMP was shown to be controlled through the opposite activities of diguanylate cyclases (DGCs) and phosphodiesterases (PDEs), which contained functional GGDEF and EAL domains, respectively. Subsequently, it was found that GGDEF and EAL domain proteins were involved in c-di-GMP synthesis and degradation (hydrolysis), respectively [9, 10]. Recently, it was shown that QS modulated the c-di-GMP signaling pathway to control bacterial virulence [11, 12], and the role of LuxS in controlling c-di-GMP production at the transcriptional level was described in Vibrio species [13]. Indeed, c-di-GMP activated biofilm formation in a variety of bacteria, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, Vibrio spp., and Yersinia pestis [14, 15] and correspondingly repressed motility of these bacteria [14, 16, 17].

In V. cholerae, an accumulation of AI-2 induced the expression of a gene encoding the master QS-regulator HapR [18]. HapR negatively affected bacterial biofilm formation and exopolysaccharide (EPS) biosynthesis [19] by lowering the intracellular level of c-di-GMP [13]. Further, HapR negatively regulated the transcription of vpsR, vpsT, and the vps genes, while VpsR and VpsT positively regulated the transcription of vps genes in V. cholerae [20]. The contribution of the AI-2 extracellular signal to this process is not clearly understood. Although LuxS was initially identified by its contribution to the expression of the hapR gene in a light production bioassay [18], deletion of the luxS gene in a later study did not affect HapR-dependent biofilm formation in V. cholerae [21].

The mechanism of coexistence and co-regulation of the above-mentioned two QS systems (AI-1 and AI-2) in A. hydrophila SSU is not clear. Since QS and c-di-GMP signaling regulate some of the same complex processes, like biofilm formation, motility, and virulence of bacteria, and since we observed that a GGDEF domain protein encoding gene is genetically linked to the luxS gene of A. hydrophila SSU [1], it is possible that these two signaling pathways converge in A. hydrophila.

In this study, we provided data showing an effect of c-di-GMP overproduction on the phenotypic and transcriptional profiling of virulence-associated genes in WT and QS mutants of A. hydrophila SSU. To our knowledge, our study is the first that illustrated an interplay between AI-1, AI-2, and c-di-GMP in A. hydrophila.

2. RESULTS

2.1. Identification of genes in A. hydrophila SSU which are homologs of QS-dependent c-di-GMP regulated genes in Vibrio and Pseudomonas

Although our recent studies showed the roles of AHL-mediated AI-1 QS system [2] and that of the luxS gene [1] in A. hydrophila virulence, we were interested in identifying additional genes which could be involved in the QS system of A. hydrophila SSU. Consequently, we took advantage of our annotation of the genome sequence of A. hydrophila subsp. hydrophila ATCC 7966T [22]. By using specific primers (Table 1) and sequence analysis of the resulting polymerase chain reaction (PCR) product, we identified the presence of two more ahyR homologs on the genome of A. hydrophila SSU. The gene ahyR2 was genetically linked to the T6SS.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotides used and PCR products

| Primer | Oligonucleotide sequence | Use | PCR product (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ggdefF1 ggdefR1 |

CCGCTCGAGATGATCAAGTATCAAATCCCCA GCTCTAGATCAGGATGGCAGCGGCATC |

GGDEF domain encoded gene of A. hydrophila cloned into pBAD/Myc-HisB ara Kmr Apr | 966 |

| litRF1 litRR1 |

GAACCACGCGCAGAAATAAG GGGCCGTCACGTACTTGA |

litR | 595 |

| vpsT (csgAB)F1 vpsT (csgAB)R1 |

TCAGAGATACTCCTTGGCCCA CGCTTCATGATCACCCCATA |

vpsT (csgAB) | 645 |

| vpsR(fleQ)F1 vpsR(fleQ)R1 |

TGCTTCCTTGCTCATCCCGTA TGTTGATTGTTGACGCCGAT |

vpsR(fleQ) | 1403 |

| fleN F1 fleN R1 |

TGGTCTGCGCAAAATGCGT TTATTCACGGGAACCTTCCTG |

fleN | 856 |

| luxSF2 luxSR2 |

ACCTCCAAGTGGGATGCGTAT CGGGCCATCGAAAAAATGT |

luxS | 971 |

| ahyRF1 ahyRR1 |

TATTGCATCAGCTTGGGGAA TGAAACAAGACCAACTGCTTG |

ahyR | 781 |

| ahyIF1 ahyIR1 |

AGGAAAATTAAAAGAACACCC TTATTCTGTGACCAGTTCGC |

ahyI | 610 |

| ahyR2F2 ahyR2R2 |

TCCTCATACCCCGGAAATGA TCACTGCTCCTCATCCACAT |

ahyR2 | 790 |

| ahyR2F1 ahyR2R1 |

ATGTTCAACGATGCGATCTG TTATGACAGCCGCAGGTTGGT |

ahyR3 | 612 |

| aha4220F1 aha4220R1 |

CAACCTTACCCATCAAGGCTA TCTATACCCACGCCTCATTCA |

aha4220 homolog | 1101 |

| aha1018F1 aha1018R1 |

AGAGAGGGGGGAGGGCAT GCATTTCAAGAAGAGTACCCA |

aha1018 homolog | 720 |

| aha0145F aha0145R |

AGAGTTTGATCATGGCTCAG GTATTACCGCGGCTGCTG |

aha0145 homolog | 531 |

We also identified in its genome the homologs of luxQ, luxU and luxO genes, which are involved in AI-2-dependent phosphorylation cascade [23], and exhibited 95, 96, and 92% homology with the corresponding genes found in the genome of A. hydrophila 7966T strain [22]. However, we were unable to amplify the luxP gene which encodes an autoinducer binding protein in V. harveyi [24, 25]. The luxP gene is also not present in the genome of A. hydrophila 7966T strain [22].

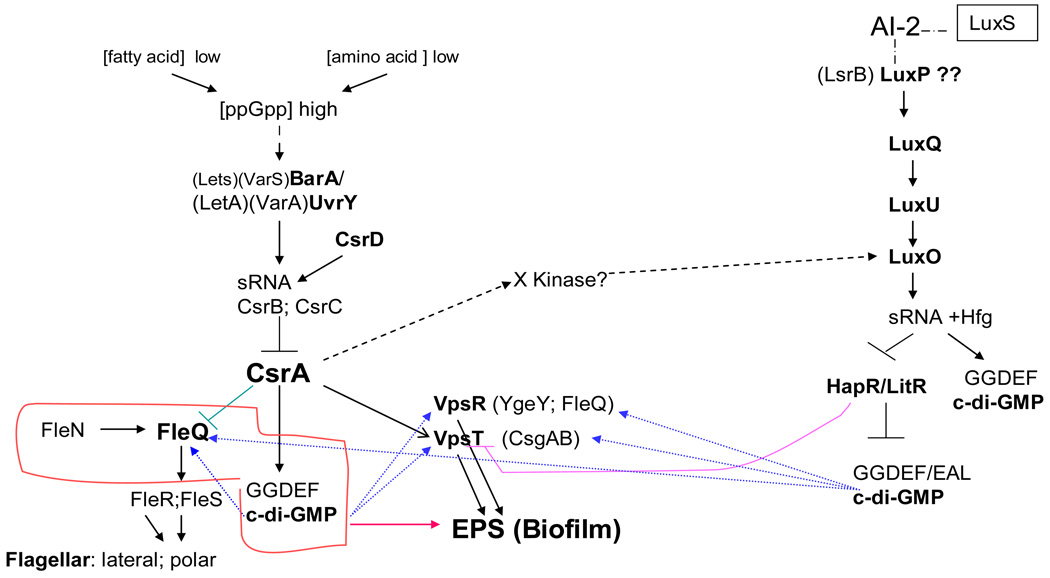

We noted the presence of a litR gene in A. hydrophila SSU which is a homolog of hapR gene in V. cholerae [19]. The LitR of A. hydrophila SSU was highly homologous (~98%) to the corresponding gene found in the annotated genome sequences of A. hydrophila 7966 and A. salmonicida subsp. salmonicida A449 strains [22, 26], and exhibited 35–40% identity with HapR protein sequences of vibrios. HapR is a DNA-binding transcription factor that initiates a program of gene expression, switching the cells from individual, low-cell-density state, to the high-cell density state [13]. HapR in V. cholerae regulates c-di-GMP metabolizing genes that lead to a net reduction in the level of cellular c-di-GMP, and thereby, to the negative control of biofim formation [13]. By directly down-regulating the expression of the vpsT gene [13], HapR is also shown to control biofilm formation in a c-di-GMP-independent manner. VpsT is a transcriptional activator which together with VpsR is required for the expression of the V. cholerae polysaccharide biosynthesis operon [27, 28]. We found the vpsT homolog, named csgAB (Fig. 7), in the A. hydrophila SSU genome which encoded a protein with 37–53% identity to VpsT of Vibrio species.

Fig. 7.

Integrated schematic based on the published information illustrating QS-dependent regulatory network in Vibrio, Pseudomonas, and A. hydrophila. LuxR/HapR/LitR represents a major regulator of QS target genes [23, 50–53] involved in the AI-2 phosphorylation cascade [19, 45–47, 72]. HapR negatively affects biofilm formation and exopolysaccharide biosynthesis [19] by lowering the intracellular level of c-di-GMP [13] and repressing the positive regulator VpsT [73]. VpsT from V. cholerae, a master regulator for biofilm formation [15], directly senses c-di-GMP to inversely control extracellular matrix production and motility. VpsR and FleQ are the transcriptional regulators containing an AAA-type ATP-ase domain and a DNA- binding domain [29]. The orthologous systems CsrA LetA/LetS exist in many gram-negative bacteria, such as S. enterica (BarA/SirA), Erwinia carotovora (ExpA/ExpS), V. cholerae (VarA/VarS), Pseudomonas spp. (GacA/GacS), Photorhabdus luminescens (UvrY/BarA) and E. coli (UvrY/BarA) [74]. The central regulator CsrA is antagonized by sRNA and CsrC, whose expression is positively regulated by the BarA-UvrY two-component system.[48, 75]. An unconventional GG-DEF-EAL protein CsrD regulates sRNAs at the level of RNA stability [76–78]. The global regulator CsrA contributes to the control of c-di-GMP levels by modulating selected panels of GGDEF and EAL genes in response to internal signals [79]. Also CsrA, a post-transcriptional regulator, can activate LuxO, possibly through an additional regulatory factor (denoted X) [80].

Interesting was also the presence of FleQ in A. hydrophila SSU (Fig. 7), which showed 51% identity with its homolog in P. aeruginosa [29], and 35% identity with VpsR in V. cholerae [28]. Likewise, the FleN in A. hydrophila SSU demonstrated 69% identity with FleN of P. aeruginosa [29]. FleQ, the first example of a c-di-GMP effector involved in transcription control, is a master regulator of flagellar gene expression in P. aeruginosa [29]. FleN, an anti-activator of FleQ, down-regulates FleQ activity through direct interactions and thereby plays a crucial role in maintaining a single flagellum in P. aeruginosa [30, 31].

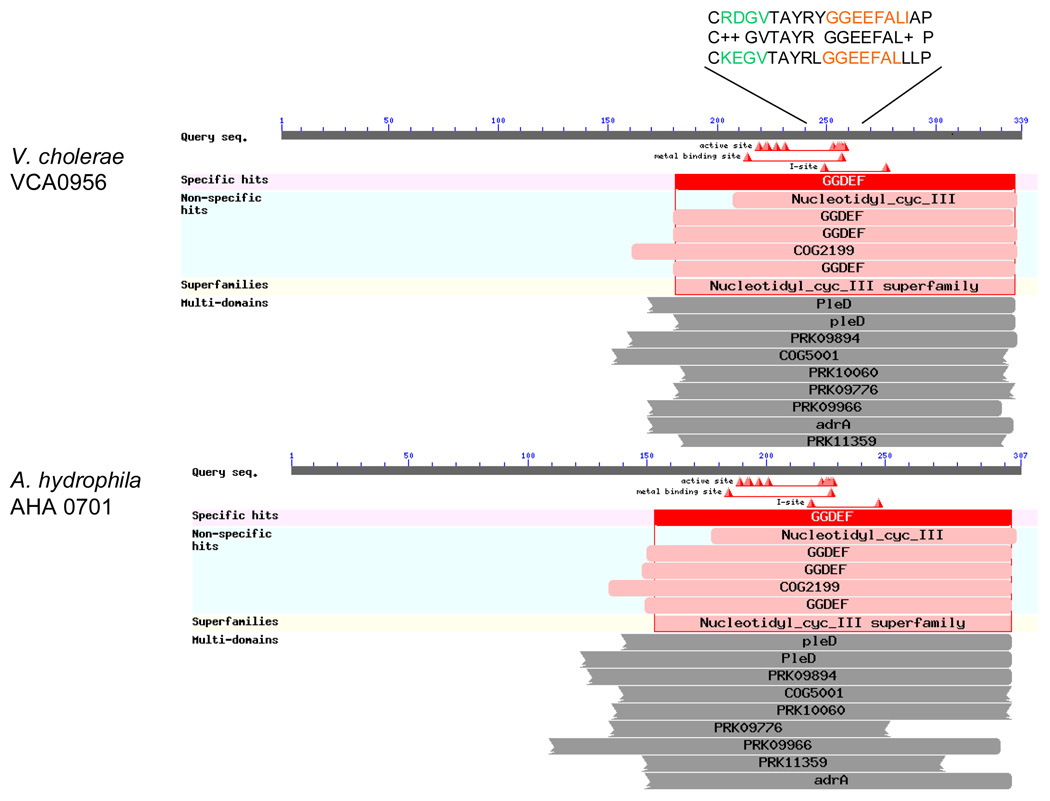

Our genome sequencing of A. hydrophila 7966 strain suggested the presence of 23 proteins containing GGDEF domain, 7 proteins with an EAL domain, and 15 proteins that had both GGDEF and EAL domains [22]. One of the GGDEF domain protein (AHA0701h) encoding genes was located immediately downstream of the luxS gene in A. hydrophila SSU. The AHA0701h protein exhibited 93% identity with its homolog found in A. hydrophila 7966 strain [22]. A homolog of A. hydrophila SSU AHA0701h, referred to as VCA0956 (46/68), was also found in V. cholerae (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

A homology of A. hydrophila AHA0701 protein with its VCA0956 homolog found in V. cholerae.

Therefore, A. hydrophila SSU QS systems have characteristics of both Vibrio and Pseudomonas, in addition to having unique signaling cascades which makes it an ideal candidate to study QS-dependent c-di-GMP regulatory network. Such studies on A. hydrophila are important as the organism leads to both gastroenteritis and septicemia depending on the route of infection [2].

2.2. Overproduction of GGDEF domain protein regulates virulence-associated phenotypes of WT A. hydrophila SSU

The GGDEF domain and an allosteric binding site for c-di-GMP (I site) [32] are typically found as part of modular DGC enzymes, which catalyze the synthesis of the signaling molecule c-di-GMP [33]. The presence of AHA0701h with GGDEF domain, the location of its gene immediately downstream of the luxS gene in A. hydrophila SSU, together with the homology of AHA0701h with VCA0956 (Fig. 1), prompted us to test the effect of its over-production on WT A. hydrophila virulence-associated phenotype(s). Indeed, overproduction of VCA0956, a cytoplasmic protein composed of a single DGC domain, was successfully used to increase c-di-GMP levels in V. cholerae [34, 35] and V. vulnificus [36]. Studies have shown that the modulation of c-di-GMP level by overproducing proteins with either the DGC or the PDE domain of V. cholerae and A. veronii biovar sobria resulted in an altered biofilm formation and motility [35, 37].

For these studies, we cloned the gene encoding AHA0701h into the pBAD/Myc-HisB vector. Subsequently, the empty vector and pBAD/Myc-His::aha0701h (Table 2) were transformed into WT A. hydrophila SSU and its ΔahyRI mutant, and the phenotype of these strains was studied after arabinose induction.

Table 2.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s) | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| A. hydrophila SSU | CDCa, Atlanta | |

| SSU-Rifr | Rifampin resistance (Rifr) | Laboratory stock |

| SSUΔluxS | luxS mutant of A. hydrophila SSU-R; Rifr Kmr | This study |

| SSUΔluxS/pBR322::luxS | luxS mutant complemented Rifr Kmr Apr | This study |

| ΔahyRI | ΔahyRI deletion mutant of hydrophila SSU-R; Rifr Smr Spr | This study |

| ΔahyRI/pBR322:: ΔahyRI | ΔahyRI mutant complemented Rifr Smr Spr Apr | |

| E. coli | TOP10 | Invitrogen |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBAD/Myc-HisB | vector, ara BAD promoter Apr | Laboratory stock |

| pBAD:: ggdef | GGDEF domain encoded gene of A. hydrophila cloned into pBAD/Myc-HisB ara Kmr Apr | Laboratory stock |

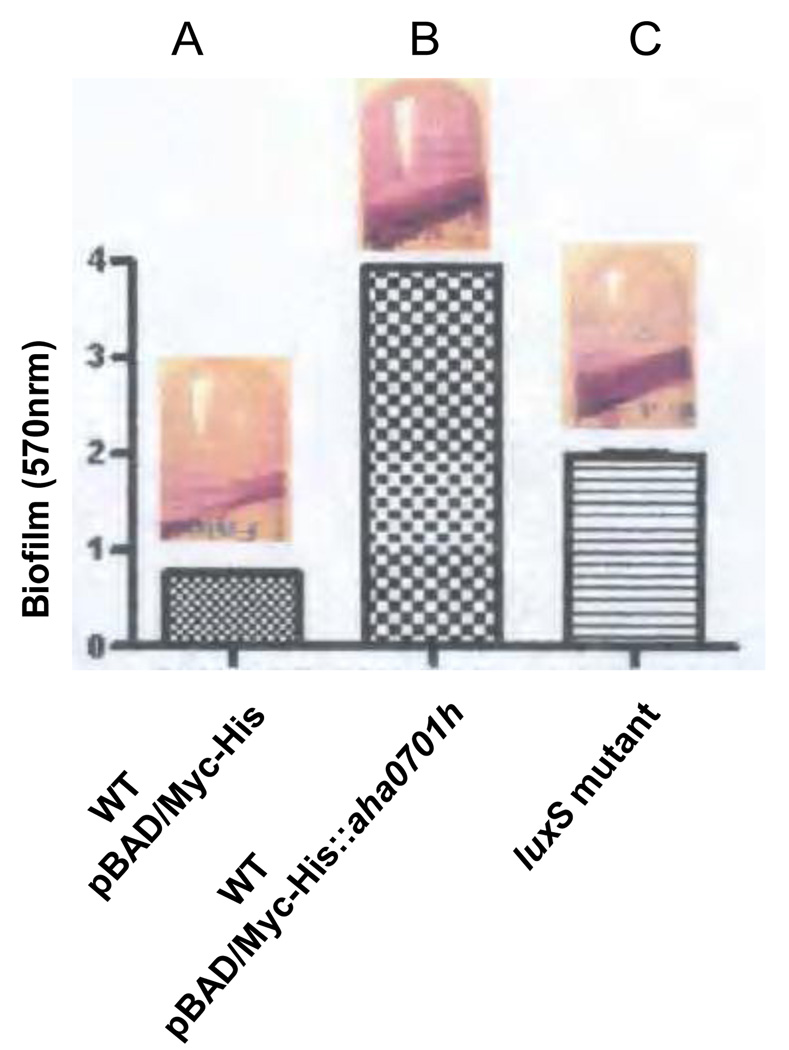

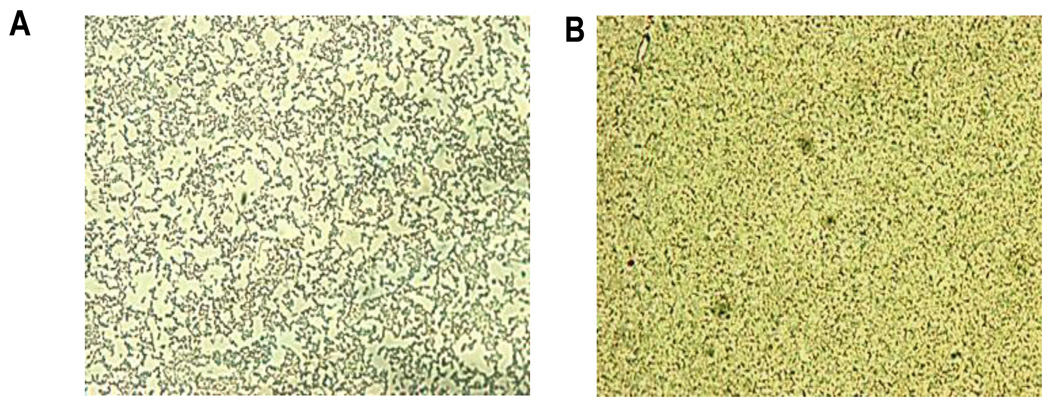

Overproduction of AHA0701h resulted in a dramatically increase in biofilm formation, as measured by quantitative crystal violet (CV) staining, in WT A. hydrophila SSU compared to that of bacteria harboring only the vector (Fig. 2A & B). The biofilm formed by WT A. hydrophila with vector alone, visualized by light microscopy, appeared as uniform sparse cell attachment on the surface of Thermanox plastic cover slips after 12 h of incubation, with a greater number of bacterial cells adherent at the line of the edge of the cover slips after 24 h of incubation (Fig. 3A). In contrast, biofilm formed by the WT A. hydrophila with pBAD/Myc-His B::aha0701h plasmid appeared as a mature, dense three-dimensional structure after 24 h of incubation, uniformly distributed all along the cover slip’s surface (Fig. 3B). Thus, overexpression of the gene encoding AHA0701h in WT A. hydrophila dramatically increased the number of attached cells and accelerated the dynamics of three-dimensional structured biofilm formation.

Fig. 2.

Measurement of biofilm mass formed on polystyrene plastic after crystal violet staining: A – WT A. hydrophila SSU with pBAD/Myc-HisB vector alone; B – WT A. hydrophila SSU with pBAD/Myc-His::aha0701h; C - ΔluxS mutant.

Fig. 3.

Light microscopy images of biofilm formation on Thermanox cover slips by WT A. hydrophila with uniform sparse cell attachment on the surface of plastic cover slip (A), and WT A. hydrophila with overproduction of GGDEF domain protein (AHA0701h), forming much thicker and denser biofilm (B), after 24 h of cultivation.

The number of biofilm forming cell-units of WT A. hydrophila SSU with overproduced GGDEF protein (AHA0701h) was greater compared to that of the ΔluxS mutant (Fig. 2B & C). Further, the ΔluxS mutant formed a matured biofilm after 48 h of incubation [1], while a mature biofilm of WT A. hydrophila SSU with overproduced GGDEF protein (AHA0701h) appeared after 24 h (Fig. 3B).

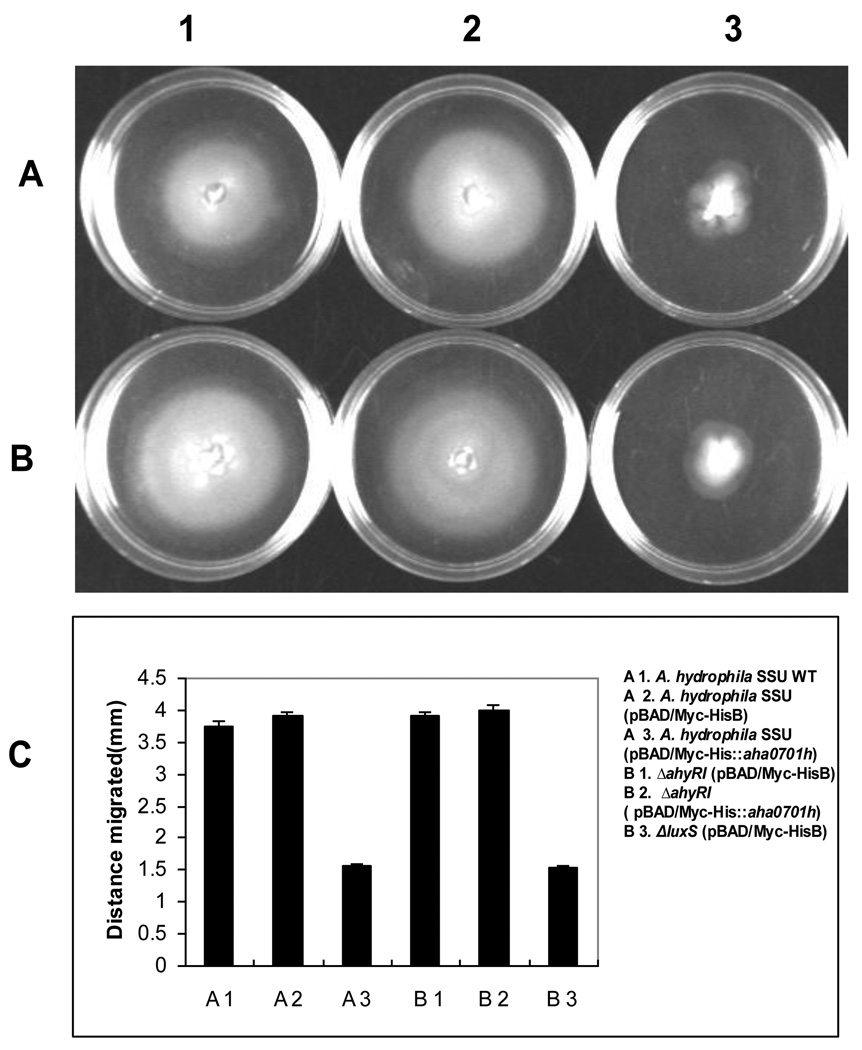

While over-expression of the gene encoding AHA0701h in WT A. hydrophila SSU positively regulated biofilm formation, motility of the bacteria was decreased compared to that of the WT bacteria (Fig. 4A-3 versus A-1). Additionally, the WT A. hydrophila, which overproduced GGDEF protein (AHA0701h), exhibited minimal motility similar to that of the A. hydrophila ΔluxS mutant (Fig. 4A-3 versus B-3).

Fig. 4.

Effect of the overproduction of AHA0701h on the motility of A. hydrophila inoculated onto the surface of 0.35% LB agar plates containing 0.2 % arabinose: A 1 – WT A. hydrophila SSU; A 2 – WT A. hydrophila SSU with pBAD/Myc-HisB vector alone; A 3 – WT A. hydrophila SSU with pBAD/Myc-His::aha0701h; B 1 - ΔahyRI mutant with pBAD/Myc-HisB vector alone; B 2 - ΔahyRI mutant with pBAD/Myc-His::aha0701h; B 3 - ΔluxS mutant with pBAD/Myc-HisB vector alone; C - the bar graph shows distances in millimeters by which these strains migrated from the point of inoculation in soft agar plates. Data from three independent experiments were plotted with standard deviations. Statistical significance by Student’s t test (p ≤ 0.05) was found for A3 and B3 compared to other genetic background strains.

Thus, over-expression of the gene encoding AHA0701h in WT A. hydrophila led to enhanced biofilm formation and decreased motility, and these data correlated with the observations of Rahman et al. (2007) who showed that overproduction of the GGDEF domain protein AdrA increased c-di-GMP concentration and biofilm formation and reduced motility in A. veronii biovar sobria [37].

2.3. The effect of over-production of GGDEF domain protein on biofilm formation and motility in the ΔahyRI mutant of A. hydrophila SSU

We transformed empty vector and pBAD/Myc-HisB::aha0701h plasmid in the ΔahyRI mutant of A. hydrophila. Recently, we demonstrated that the ahyRI deletion resulted in decreased biofilm formation but the motility of the mutant was not affected compared to that of the parental bacteria [2]. In contrast to WT A. hydrophila with overproduced GGDEF protein (AHA0701h), which resulted in increased biofilm formation (Figs. 2B &3B), biofilm formed by the ΔahyRI mutant with over-production of GGDEF protein was marginally increased after 48 h of incubation (data not shown).

Importantly, both WT A. hydrophila and its ΔahyRI mutant had similar swarming and swimming motility [2] (also Fig. 4 A-2 versus B-1). However, overproduction of the GGDEF protein (AHA0701h) in the ΔahyRI mutant did not alter its motility compared to that of the parental mutant strain (Fig. 4 B-1 versus B-2). This was in contrast to decrease in motility that was observed with the WT A. hydrophila overproducing the GGDEF protein (AHA0701h) (Fig. 4 B-2 versus A-3). Thus, overproduction of GGDEF protein in WT versus its ΔahyRI mutant exhibited contrasting phenotypic alterations.

These data prompted us to study alteration in the transcription of major genes involved in biofilm formation and motility of the WT A. hydrophila and its ΔahyRI mutant after overproduction of GGDEF protein (AHA0701h), as compared to the parental background strains and the luxS mutant. Such studies were performed to evaluate a possible correlation between the presence and expression of QS system-encoding genes and c-di-GMP overproduction in A. hydrophila.

2.4. Alteration in the transcription of genes involved in biofilm formation and motility in luxS and ahyRI mutants of A. hydrophila SSU

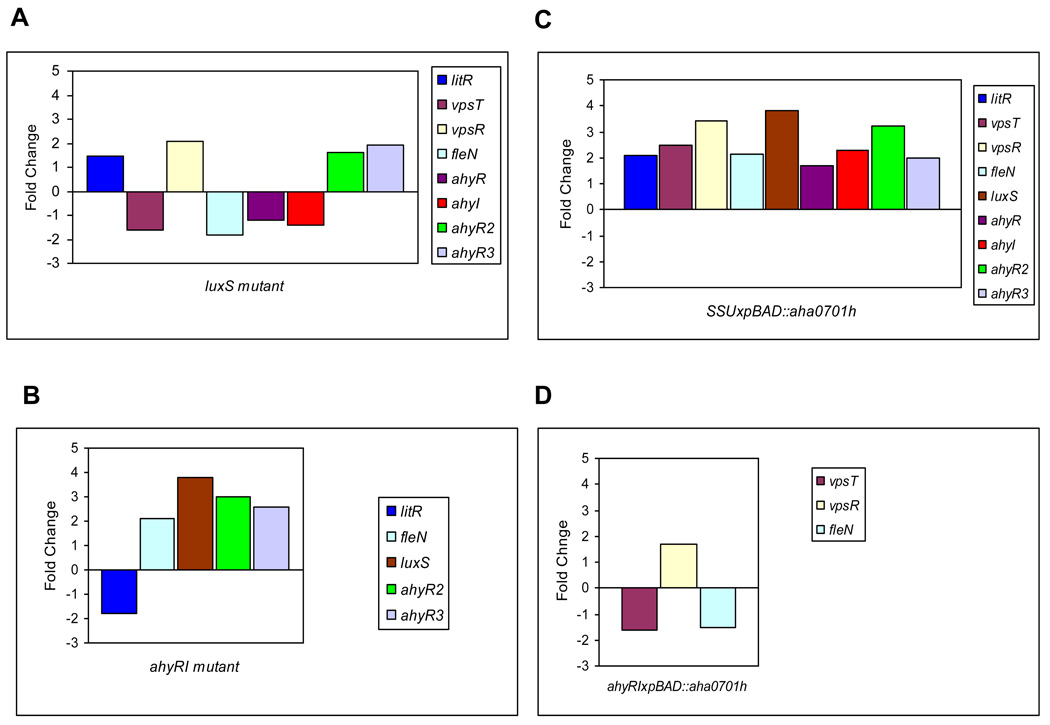

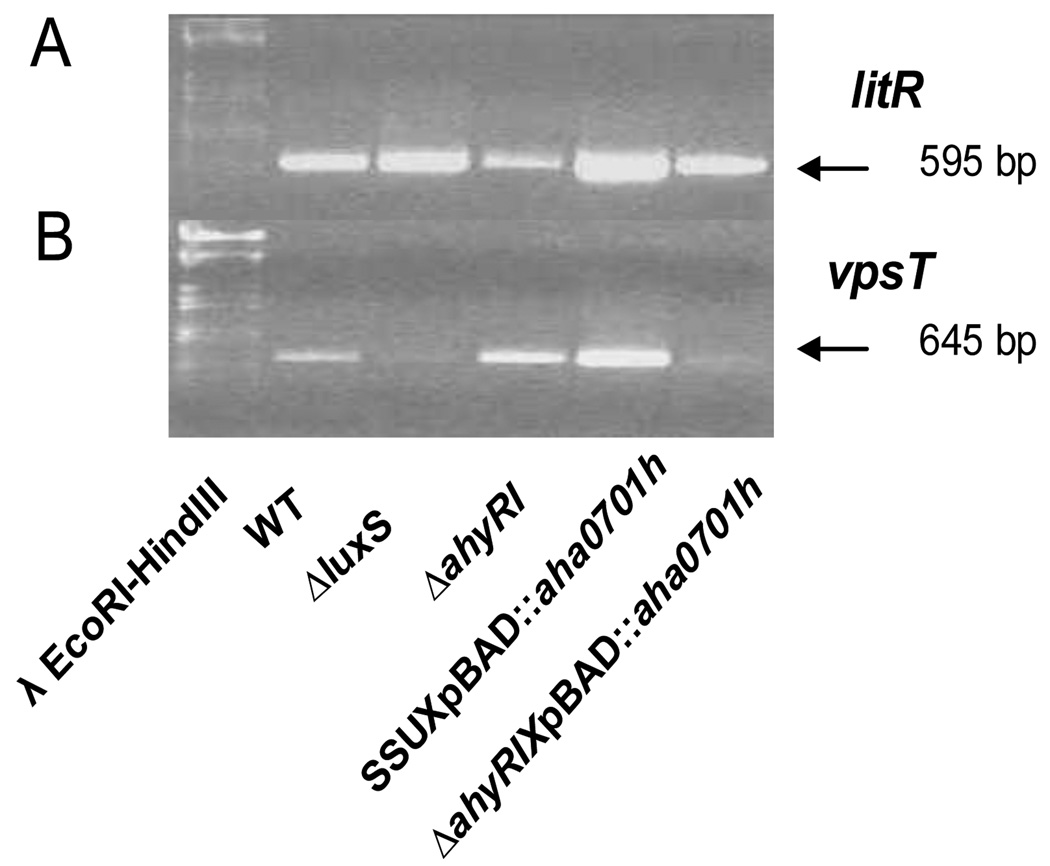

The analysis of transcripts by reverse-transcription PCR demonstrated increases in the levels for litR and fleQ (vpsR), and decreases in the levels of csgAB (vpsT) and fleN in the ΔluxS mutant compared to that of WT A. hydrophila (Fig. 5A; Supplemental data, Table I). On the contrary, the ΔahyRI mutation in WT A. hydrophila led to down-regulation of the litR (Figs. 5B and 6A) and an up-regulation of the fleN gene transcript (Fig. 5B), but the levels of expression for the csgAB (vpsT) (Fig. 6B) and fleQ (vpsR) genes were not altered compared to that of the WT A. hydrophila (Supplemental data, Table I). The ΔahyRI mutation also caused an increase in the luxS gene transcript as compared to that of the WT A. hydrophila (Fig. 5B). The expression level of the aha0701h gene in the ΔahyRI mutant was comparable to that in the WT bacteria (Supplemental data, Fig. I, lanes 1 & 3) in contrast to an over-expression of this gene which we noticed in the ΔluxS mutant (Supplemental data, Fig. I, lanes 1 & 2).

Fig. 5.

Schematic representation of fold-changes in the expression of selected genes in various genetic backgrounds of A. hydrophila SSU: the luxS mutant (A); the ahyRI mutant (B); WT with AHA0701h over-production (C); the ahyRI mutant with AHA0701h over-production (D). The data used to generate fold changes (arithmatic mean ± SD) with statistical analysis is shown in Table I; Supplemental data.

Fig. 6.

Reverse-transcription PCR analysis of the litR (A) and vpsT (B) gene expression in different genetic backgrounds of A. hydrophila SSU.

It is known that the elevation of c-di-GMP in the low-cell-density state of V. cholerae induces the transcriptional activator vpsT involved in HapR/LitR-dependent regulation of biofilm formation [27]. Further, regulation by VpsR has also been linked to signal transduction by bacterial c-di-GMP [38, 39]. These studies prompted us to overexpress GGDEF protein (AHA0701h) encoding gene for studying the effect of high level of intracellular c-di-GMP on the transcriptional expression of selected genes mentioned above in WT A. hydrophila and its ΔahyRI mutant.

2.5. The effect of overproduction of GGDEF domain protein on genes involved in biofilm formation and regulation of motility in WT and ΔahyRI mutant of A. hydrophila SSU

We found that luxS, litR, csgAB (vpsT), fleQ, and fleN gene transcripts were significantly increased by AHA0701h overproduction in WT bacteria (Fig. 5C; Supplemental data, Table I). It should be noted that the expression levels of these genes in WT and the WT with vector alone were similar. When GGDEF protein was overproduced in the ΔahyRI mutant, the litR gene transcript was increased compared to its level noted in the ΔahyRI mutant with vector alone (Fig. 6A). At the same time, this level of litR gene transcript in the ΔahyRI mutant with overproduced GGDEF protein was comparable to that in the WT bacteria with vector alone (Fig. 6A; Supplemental data, Table I). Most likely, AHA0701h overproduction normalized the transcriptional level of litR gene in the ΔahyRI mutant, making it similar to that in the WT bacteria.

The same trend of transcript level normalization was also noted for the luxS gene in the ΔahyRI mutant with AHA0701h over-production (Supplemental data, Table I) but occurred as a result of down-regulation of this gene (Supplemental data, Table I). While the transcripts for csgAB (vpsT) and fleQ (vpsR) were not altered in the ΔahyRI mutant compared to that of WT bacteria (Supplemental data, Table I), the AHA0701h overproduction led to decreased levels of csgAB (vpsT) (Figs. 5D and 6B) and the increased levels of fleQ (vpsR) (Fig. 5D) in the ΔahyRI mutant.

Thus, the ahyRI deletion affected on the differentiation in the transcriptional responses of selected genes under AHA0701h over-production conditions compared to that in the WT A. hydrophila.

2.6. Co-modulation of QS gene transcripts and the effects of GGDEF domain protein overproduction on the expression of gene transcript levels in A. hydrophila SSU

Our data showed that the luxS gene transcript modulation was dependent on the presence and expression of AI-1 genes and on the c-di-GMP levels (Figs. 5B, C & D). This prompted us to study the effects of luxS mutation and c-di-GMP level modulation on the expression of ahyR, ahyI, and two additional ahyR (ahyR2 and ahyR3) homologs which exist in A. hydrophila SSU. The ahyR and ahyI gene transcripts were down-regulated in the ΔluxS mutant, while the ahyR2 and ahyR3 gene transcripts were over-expressed compared to that in the WT bacteria (Fig. 5A, Supplemental data, Table I). The GGDEF protein when overproduced in WT A. hydrophila resulted in the up-regulation of luxS, ahyI and all of the three homologs of ahyR genes as compared to that in the WT bacteria with vector alone (Fig. 5C, Supplemental data, Table I).

In the ahyRI mutant, the expression of ahyR2 and ahyR3, together with the luxS gene was increased as compared to that in the WT A. hydrophila (Fig. 5B, Supplemental data, Table I). However, overproduction of GGDEF protein in the ahyRI mutant resulted in down-regulation of luxS, ahyR2, and ahyR3 gene transcripts compared to that in the ΔahyRI mutant with vector alone. The level of expression of these genes returned to the level of WT bacteria (Supplemental data, Table I). Thus, our results demonstrated that AI-1 and AI-2 QS systems were linked at least at the transcriptional level in A. hydrophila SSU. The GGDEF domain protein overproduction modulated the transcriptional levels of genes involved in AI-1 and AI-2, and this modulation was dependent on the presence of both of them in the cells.

3. DISCUSSION

In this study, we identified additional components of LuxS- and AhyRI- dependent QS and c-di-GMP networks in A. hydrophila SSU. Majority of reports on the ΔluxS mutant indicated that the lack of luxS gene in bacteria led to attenuation in biofilm formation and virulence, or retention of virulence but to a decrease in biofilm formation [40–43]. However, Ali and Benitez [44] recently showed that in V. cholerae ΔluxS mutant, there occurred an increase in biofilm formation similar to our findings in A. hydrophila SSU [1]. This finding subsequently was correlated with the model of QS regulation and biofilm formation in V. cholerae through the modulation of intracellular c-di-GMP level [13].

In Vibrio species, sensing of extracellular AI-2 involves a regulation cascade consisting of a binding protein LuxP and the response regulator LuxQ (Fig. 7) [24, 19, 47]. The VarS/A-CsrA/BCD system is an additional signaling mechanism that acts in parallel with the two QS systems to input information into LuxO [48] (Fig. 7). The global regulators CsrA and HapR both largely contribute to the control of c-di-GMP levels by modulating selected panels of GGDEF and EAL domain-encoding genes in response to internal signals [13, 48] (Fig. 7). In addition to QS-dependent HapR regulating cascade, we also identified the VarS/VarA (LetS/LetA)-CsrA regulatory system in the A. hydrophila SSU genome (unpublished data) by examining gene homologs that exist in a variety of gram-negative bacteria [48]. However, subtle differences were noted, for example, between the HapR-dependent QS systems of V. cholerae and A. hydrophila SSU. Further, how these two regulatory systems co-function in A. hydrophila is not known yet.

To date, two types of AI-2 receptors have been identified: LuxP, present in Vibrio species and LsrB, first identified in S. Typhimurium [24, 49] (Fig. 7). However, we could not identify any homolog of such receptors in A. hydrophila SSU. Moreover, no information about sRNAs involved in A. hydrophila SSU QS regulation is available from the genome sequence of A. hydrophila ATCC 7966 [22].

We did identify homologs of luxQ, luxU, luxO, and litR/hapR genes in A. hydrophila SSU genome similar to that found in Vibrio [58]. LuxR/HapR is the only TetR family member that appears to act as both activator and repressor [50–53]. While the mechanism by which LuxR (HapR) activates qrr (encoding sRNA) gene expression in V. harveyi is yet to be determined, it is known that the expression of the qrr gene requires LuxO~P acting in conjunction with the alternative sigma factor sigma-54 [23, 54]. Recently, Waters et al. [13] demonstrated that HapR altered the expression of 14 genes encoding proteins with GGDEF and/or EAL domains. The QS control of these genes resulted in increased intracellular levels of c-di-GMP at low cell density and decreased c-di-GMP levels at high cell density. The major consequence of increased c-di-GMP in the low-cell-density state is the induction of biofilm transcriptional activator vpsT (Fig. 7) [27]. We identified the homolog of vpsT in WT A. hydrophila SSU genome which is designated as csgAB. VpsT is a member of the FixJ, LuxR, and CsgD family of prokaryotic response regulators [55–57].

We did not find any candidate protein which was closely related to VpsR of V. cholerae, a key regulator of biofilm formation [28, 58], in the A. hydrophila genome, but FleQ (found in P. aeruginosa) [29], a distant VpsR homolog, encoding gene was detected (Fig. 7). In V. parahaemolyticus, the role of VpsR is reported to be strain dependent [59] while in V. fischeri, VpsR might function as a repressor of an unknown polysaccharide that could contribute to mucoidal versus non-mucoidal bacterial colonies, and together with a positive regulator of cellulose biosynthesis, might involve in the complexity of the biofilm formation [60].

VpsR and FleQ are transcriptional regulators containing an AAA-type ATPase domain and a DNA-binding domain, and belong to Fis family of prokaryotic response regulators. FleQ was identified as a c-di-GMP responsive transcriptional regulator that controls the transcription of exopolysaccharide biosynthesis genes in P. aeruginosa (Fig. 7) [29]. However, FleQ also activates expression of the two component regulatory genes fleSR (Fig. 7) as well as genes that are necessary for the assembly of the flagellar export apparatus [29, 61–64]. We demonstrated the presence of fleQ, fleS and fleR gene homologs in A. hydrophila SSU genome (unpublished data) in contrast to A. hydrophila AH-3 strain, where no master regulatory genes encoding homologs of P. aeruginosa FleQ, FleS, and FleR were found [65]. We also identified FleN which is an anti-activator of FleQ in P. aeruginosa [29–31, 38]. We believe that FleQ of A. hydrophila SSU is a significant player in biofilm formation and bacterial motility.

While searching for genes encoding c-di-GMP metabolic proteins in A. hydrophila SSU genome in addition to aha0701h, we identified the presence of aha4220 and aha1018 gene homologs. These genes encode DGC and PDE, respectively, but we could not identify, for instance, a homolog of A. hydrophila ATCC 7966 aha0996 gene that encodes DGC (unpublished data). Thus, QS-dependent c-di-GMP regulatory network in A. hydrophila SSU includes the elements of cascade related to that in Vibrio and Pseudomonas, thus making this system unique.

To better understand the role of LuxS and AhyRI in QS-dependent c-di-GMP regulatory network in A. hydrophila SSU, we monitored transcript levels of the selected genes involved in biofilm and motility regulation and the effects on them by overproduction of GGDEF protein.

Interestingly, the fact that the litR gene was up-regulated in the ΔluxS mutant of A. hydrophila SSU was surprising in itself because it is totally distinct compared to the QS-dependent hapR regulation which exists in Vibrio [23] (Fig. 7). Together with the absence of major components of the QS-dependent regulating cascade, such as the LuxP and the genes encoded cascade involving sRNA, suggest a different mechanism of LuxS-dependent QS gene regulation in V. cholerae [48, 58] and A. hydrophila.

Biofilm formation in V. cholerae is primarily controlled by two transcriptional activators VpsT and VpsR, which are required for the expression of Vibrio polysaccharide biosynthesis operon vps [58]. HapR represses vpsT expression both by reducing the cellular concentration of c-di-GMP via altering transcription of genes encoding GGDEF and EAL proteins and by directly binding to the vpsT promoter [13]. In addition, recently, Krasteva et al. [15] showed that the transcriptional regulator VpsT from V. cholerae directly senses c-di-GMP to inversely control biofilm and motility.

Our study showed that the ΔluxS mutant of A. hydrophila SSU formed denser biofilm and exhibited decreased motility, however, the csgAB (vpsT) transcript was down-regulated, while the fleQ (vpsR) was increased. Importantly, VpsR in A. hydrophila SSU was more closely related to FleQ in P. aeruginosa [29] thus making LitR-VpsT-FleQ system of A. hydrophila SSU unique.

Importantly, in contrast to the luxS mutant, the transcript levels for the vpsT and vpsR genes in the ahyRI mutant of A. hydrophila SSU were similar to that in the WT bacteria in spite of litR gene down-regulation, and no alteration in biofilm formation and motility was noted. However, we evidenced that ahyRI deletion sufficiently altered transcriptional response and phenotype changes when GGDEF protein was overproduced in the ahyRI mutant compared to that in the WT A. hydrophila SSU.

Notably, overproduction of GGDEF protein in WT A. hydrophila SSU resulted in increase of all selected genes compared to that in the WT bacteria (Fig. 5C). An increase in the luxS and litR transcripts could provide a decrease in c-di-GMP level that correlated with the common scheme of LuxS-dependent HapR c-di-GMP regulation in Vibrio [66] (Fig. 7). However, because GGDEF protein is overproduced, the c-di-GMP level continued to be very high that consequently could stimulate csgAB (vpsT) and fleQ (vpsR) expression levels as noted in Fig. 5C. The phenotypic alterations noted with the overproduction of GGDEF protein in the WT A. hydrophila SSU were not surprising, and corroborated with the effects of high level of c-di-GMP on biofilm formation and motility in A. veronii [37] and V. vulnificus [36]. Interestingly, these alterations were similar to that found in the ΔluxS mutant, however, the transcriptional level of expression of the selected genes involved in the biofilm formation and motility regulation were distinct.

In contrast to the up-regulation of all selected genes which were revealed in the WT A. hydrophila SSU when GGDEF protein was overproduced, in the ΔahyRI mutant, the overproduction of AHA0701h mostly resulted in adjustment of the selected gene expression levels to the level of these genes in the WT bacteria. The exceptions to that were vpsT (csgAB) and fleN, which were down-regulated, and vpsR (fleQ), which was up-regulated when compared to the same gene transcripts in the WT A. hydrophila SSU. These gene transcript level alterations were not essentially affecting motility and biofilm formation in the ΔahyRI mutant. More likely, the deletion of the ahyRI genes abrogated the effect of GGDEF protein overproduction on gene expression in the ΔahyRI mutant compared to that in the WT A. hydrophila SSU when GGDEF protein was overproduced.

In addition, we observed for the first time to our knowledge, that mutation in either the luxS gene or the ahyRI genes caused an alteration in gene transcripts of the remaining functional QS system of A. hydrophila. Interestingly, together with the luxS gene up-regulation, the expression levels of two additional copies of the ahyR gene were increased in the ahyRI mutant. Moreover, the overproduction of GGDEF protein brought down these transcripts to the level comparable to that in WT A. hydrophila SSU.

In conclusion, the transcript level of genes involved in AI-1 and AI-2 QS systems were co-regulated in A. hydrophila SSU. A balance of transcriptional level of gene expression between luxS and ahyR was regulated by modulation of c-di-GMP level. The luxS and luxR- type (ahyR) regulator of AI-1 mutually compensated each other at least at the transcriptional level. The effects of c-di-GMP modulation on a number of common genes involved in motility and biofilm formation regulation were dependent on the expression AI-1 and AI-2 systems.

4. MATERIALS AND METHODS

4.1. Bacterial strains and plasmids

The sources of A. hydrophila and E. coli strains, as well as the plasmids used in this study, are listed in Table 2. The antibiotics ampicillin (Ap), kanamycin (Km), streptomycin (Sp), and spectinomycin (Sm) were used at concentrations of 50–500, 50–100, 50–100 and 50–100 µg/ml, respectively, in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium or agar plates. Rifampicin (Rif) was utilized at a concentration of 50 µg/ml for bacterial growth and 300 µg/ml during transformation experiments. All of the antibiotics used were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Restriction endonucleases and T4 DNA ligase were obtained from Promega (Madison, WI). The Advantages cDNA PCR Kit was purchased from Clontech (Palo Alto, CA). The digested plasmid DNA or DNA fragments from agarose gels were purified using a QIApreps Miniprep Kit (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA). The medium was supplemented with L-arabinose (0.2%) when the ggdef gene was expressed from the pBAD/Myc-HisB::ggdef plasmid (Table 1) under the control of an arabinose-inducible pBAD promoter.

4.2. Primers and PCR assays

The primers used for various experiments are indicated in Table 1 and were synthesized by Sigma-Aldrich Biotechnology LP. PCR assays were performed with 100 ng of gDNA and 50 ng of plasmid DNA.

4.3. Cloning of the aha0701h gene into pBAD/Myc-HisB

The aha0701h gene was amplified with primers ggdeF1 and ggdefR1 from A. hydrophila SSU genomic DNA. The PCR product was digested with the indicated enzymes and cloned into the XhoI and XbaI sites of the conjugative expression vector pBAD/Myc-HisB. Correct clones were verified by restriction digestion and sequencing. Expression of the aha0701h gene was induced with arabinose.

4.4. Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Standard conditions for the isolation of total RNA from cells grown overnight in LB medium were used (Ambion, Austin, TX). RNA concentration was determined by optical density at 260 nm. Triple measurements were performed for each RNA sample and an average value was obtained as a final concentration. RT-PCR was performed using SuperScript™ III Platinum (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Equal amounts of DNase-treated total RNA (500 ng) were used to generate cDNA with random hexamer primers according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

The resultant cDNA was diluted eight times with Nuclease-free water and concentration was determined by optical density at 260 nm. The diluted cDNA was subsequently used in 50 µl of RT-PCR reaction. Sequences of primers used in RT-PCR are shown in Table 1. The 16S rRNA was used as the internal control gene to confirm that equal amounts of total RNA was used in each reaction [67, 68]. As a negative control and a control to detect DNA contamination, water and DNase treated RNA were used in place of cDNA template, respectively. For RT-PCR analysis, 30–35 cycles of PCR reaction was used. Standard techniques were employed to prevent and detect in vitro contamination of the PCR reactions. Amplified products were identified by size, by using agarose-gel electrophoresis and ethidium-bromide staining. Specificity of the amplified products was demonstrated by DNA sequence analysis. The relative level of the cDNAs of RT-PCR was determined by densitometric analyses using AlphaEasyFC software (AlphaInnotech, San Leandro, CA) using 16S rRNA genes as references.

4.5. in vitro growth of the biofilm

Briefly, 6-well, sterile polystyrene microtiter plates were filled with 2.5 ml of LB broth supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics. Next, a sterile, 13-mm-diameter thermanox plastic cover slip was laid in each of the wells. Medium was inoculated with 106 colony forming units (cfu) of WT A. hydrophila or its mutants, and the plates were incubated at 37°C. After 12, 24 or 48 h of incubation with gentle shaking (65 rpm), those bacterial cells that were not sufficiently adherent, were removed along with the planktonic cells, by 3 washes of water. Glass or Thermanox plastic cover slips containing the attached biofilms were removed, rinsed with water, and viewed by light microscopy.

4.6. Motility assay

LB medium with 0.35% agar was used to characterize the motility phenotype of WT A. hydrophila SSU and its mutants strain. The overnight cultures grown in the presence of respective antibiotic were adjusted to the same optical density, and equal numbers of CFU (106) were stabbed into 0.35% LB agar plates. Plates were incubated at 37°C overnight, and the motility was assayed by examining migration of bacteria through the agar from the center towards the periphery of the plate [69].

4.7. Crystal violet (CV) biofilm assay

The WT A. hydrophila SSU and its mutants were grown in 3 ml LB broth contained in polystyrene tubes at 37°C for 24 h with shaking. Biofilm formation was quantified according to the procedure described elsewhere [70, 71]. The biofilm formation results were normalized to 1× 109 cfu to account for any differences in the growth rate of various bacterial strains used. The experiment was repeated independently three times.

4.8. Statistical analysis

All of the experiments were performed in triplicate, and wherever appropriate, the data were analyzed by using the Student’s t test, with a p value of ≤ 0.05 considered significant. The data were presented as an arithmetic mean ± standard deviation.

Supplementary Material

Figure I. Reverse-transcription PCR analysis of aha0701h gene encoding GGDEF domain protein (A) and 16S RNA as a reference (B) in: 1. WT A. hydrophila SSU; 2. ΔluxS mutant of A. hydrophila SSU; 3. ΔahyRI mutant of A. hydrophila SSU.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the grants from NIH/NIAID (AI041611) and the Environmental Protection Agency.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kozlova EV, Popov VL, Sha J, Foltz SM, Erova TE, Agars SL, Horneman J, Chopra AK. Mutation in the S-Ribosylhomocysteinase (luxS) gene involved in quorum sensing affects biofilm formation and virulence in a clinical isolate of Aeromonas hydrophila. Microbial Pathogenesis. 2008;45:343–354. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khajanchi BK, Sha J, Kozlova EV, Erova TE, Suarez G, Sierra JC, Popov VL, Horneman AJ, Chopra AK. N-Acyl Homoserine lactones involved in quorum sensing control type VI secretion system, biofilm formation and virulence in a clinical isolate of Aeromonas hydrophila. Microbiology. 2009;155(Pt 11):3518–3531. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.031575-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waters CM, Bonnie BL. Quorum sensing: cell-to-cell communication in bacteria. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2005;21:319–346. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.012704.131001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Winzer K, Hardie KR, Williams P. LuxS and autoinducer-2: their contribution to quorum sensing and metabolism in bacteria. Adv Appl Microbiol. 2003;53:291–396. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2164(03)53009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Irie Y, Parsek MR. Quorum sensing and microbial biofilms. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2008;322:67–84. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-75418-3_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tamayo R, Schild S, Pratt JT, Camilli A. Role of cyclic di-GMP during El Tor biotype Vibrio cholerae Infection: Characterization of the in vivo induced cyclic di-GMP phosphodiesterase CdpA. Infect Immun. 2008;76(4):1617–1627. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01337-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kendall MM, Sperandio V. Quorum sensing by enteric pathogens. Current Opinion in Gastroenterology. 2007;23(1):10–15. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e3280118289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hengge R. Principles of c-di-GMP signalling in bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7(4):263–273. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paul R, Weiser S, Amiot NC, Chan C, Schirmer T, Giese B, Jenal U. Cell cycle-dependent dynamic localization of a bacterial response regulator with a novel di-guanylate cyclase output domain. Genes Dev. 2004;18(6):715–727. doi: 10.1101/gad.289504. 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmidt AJ, Ryjenkov DA, Gomelsky M. The ubiquitous protein domain EAL is a cyclic diguanylate-specific phosphodiesterase: enzymatically active and inactive EAL domains. J Bacteriol. 2005;187(14):4774–4781. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.14.4774-4781.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Römling U, Simm R. Prevailing concepts of c-di-GMP signaling. Contrib Microbiol. 2009;16:161–181. doi: 10.1159/000219379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Römling U, Gomelsky M, Galperin MY. C-di-GMP: the dawning of a novel bacterial signalling system. Mol Microbiol. 2005;57(3):629–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waters CM, Lu W, Rabinowitz JD, Bassler BL. Quorum sensing controls biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae through modulation of cyclic di-GMP levels and repression of vpsT. J Bacteriol. 2008;90(7):2527–2536. doi: 10.1128/JB.01756-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tamayo R, Pratt JT, Camilli A. Roles of cyclic diguanylate in the regulation of bacterial pathogenesis. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2007;61:131–148. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krasteva PV, Fong JC, Shikuma NJ, Beyhan S, Navarro MV, Yildiz FH, Sondermann H. Vibrio cholerae VpsT regulates matrix production and motility by directly sensing cyclic di-GMP. Science. 2010;327(5967):866–868. doi: 10.1126/science.1181185. 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuchma SL, Ballok AE, Merritt JH, Hammond JH, Lu W, Rabinowitz JD, O'Toole GA. Cyclic-di-GMP-mediated repression of swarming motility by Pseudomonas aeruginosa: the pilY1 gene and its impact on surface-associated behaviors. J Bacteriol. 2010;192(12):2950–2964. doi: 10.1128/JB.01642-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee HS, Gu F, Ching SM, Lam Y, Chua KL. CdpA is a Burkholderia pseudomallei cyclic di-GMP phosphodiesterase involved in autoaggregation, flagellum synthesis, motility, biofilm formation, cell invasion, and cytotoxicity. J Bacteriol. 2010;192(12):2950–2964. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00446-09. Epub 2010 Mar 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller MB, Skorupski K, Lenz DH, Taylor K, Bassler BL. Parallel quorum sensing systems converge to regulate virulence in Vibrio cholerae. Cell. 2002;110:303–314. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00829-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hammer BK, Bassler BL. Quorum sensing controls biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae. Mol Microbiol. 2003;50(1):101–104. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shikuma NJ, Fong JC, Odell LS, Perchuk BS, Laub MT, Yildiz1 FH. Overexpression of VpsS, a hybrid sensor kinase, enhances biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 2009;191(16):5147–5158. doi: 10.1128/JB.00401-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu J, Mekalanos JJ. Quorum sensing-dependent biofilms enhance colonization in Vibrio cholerae. Dev Cell. 2003;5(4):647–656. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00295-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seshadri R, Joseph SW, Chopra AK, Sha J, Shaw J, Graf J, Haft D, Wu M, Ren Q, Rosovitz M, Madupu R, Tallon L, Kim M, Jin S, Vuong H, Stine OC, Ali A, Horneman AJ, Heidelberg JF. Genome sequence of Aeromonas hydrophila ATCC 7966T: jack of all trades. J Bacteriol. 2006;188(23):8272–8282. doi: 10.1128/JB.00621-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lenz DH, Mok KC, Lilley BN, Kulkarni RV, Wingreen NS, Bassler BL. The small RNA chaperone Hfq and multiple small RNAs control quorum sensing in Vibrio harveyi and Vibrio cholerae. Cell. 2004;118(1):1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen X, Schauder S, Potier N, Van Dorsselaer A, Pelczer I, Bassler BL, Hughson FM. Structural identification of a bacterial quorum-sensing signal containing boron. Nature. 2002;415(6871):545–549. doi: 10.1038/415545a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Federle MJ, Bassler BL. Interspecies communication in bacteria. J Clin Invest. 2003;112(9):1291–1299. doi: 10.1172/JCI20195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reith ME, Singh RK, Curtis B, Boyd JM, Bouevitch A, Kimball J, Munholland J, Murphy C, Sarty D, Williams J, Nash JH, Johnson SC, Brown LL. The genome of Aeromonas salmonicida subsp. salmonicida A449: insights into the evolution of a fish pathogen. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:427. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-427. 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Casper-Lindley C, Yildiz FH. VpsT is a transcriptional regulator required for expression of vps biosynthesis genes and the development of rugose colonial morphology in Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor. J Bacteriol. 2004;186(5):1574–1578. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.5.1574-1578.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yildiz FH, Dolganov NA, Schoolnik GK. VpsR, a member of the response regulators of the two-component regulatory systems, is required for expression of vps biosynthesis genes and EPS (ETr)-associated phenotypes in Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor. J Bacteriol. 2001;183(5):1716–1726. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.5.1716-1726.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hickman JW, Harwood CS. Identification of FleQ from Pseudomonas aeruginosa as a c-di-GMP-responsive transcription factor. Mol Microbiol. 2008;69(2):376–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06281.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dasgupta N, Arora SK, Ramphal R. fleN, a gene that regulates flagellar number in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 2000;182(2):357–364. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.2.357-364.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dasgupta N, Ramphal R. Interaction of the antiactivator FleN with the transcriptional activator FleQ regulates flagellar number in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 2001;183(22):6636–6644. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.22.6636-6644.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jenal U, Malone J. Mechanisms of cyclic-di-GMP signaling in bacteria. Annu Rev Genet. 2006;40:385–407. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.40.110405.090423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Navarro MV, De N, Bae N, Wang Q, Sondermann H. Structural analysis of the GGDEF-EAL domain-containing c-di-GMP receptor FimX. Structure. 2009;17(8):1104–1116. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tischler AD, Camilli A. Cyclic diguanylate (c-di-GMP) regulates Vibrio cholerae biofilm formation. Mol Microbiol. 2004;53(3):857–869. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04155.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beyhan S, Tischler AD, Camilli A, Yildiz FH. Transcriptome and phenotypic responses of Vibrio cholerae to increased cyclic di-GMP level. J Bacteriol. 2006;188(10):3600–3613. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.10.3600-3613.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakhamchik A, Wilde C, Rowe-Magnus DA. Cyclic-di-GMP regulates extracellular polysaccharide production, biofilm formation, and rugose colony development by Vibrio vulnificus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74(13):4199–4209. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00176-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rahman M, Simm R, Kader A, Basseres E, Römling U, Möllby R. The role of c-di-GMP signaling in an Aeromonas veronii biovar sobria strain. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2007;273(2):172–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lim B, Beyhan S, Meir J, Yildiz FH. Cyclic-diGMP signal transduction systems in Vibrio cholerae: modulation of rugosity and biofilm formation. Mol Microbiol. 2006;60(2):331–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beyhan S, Yildiz FH. Smooth to rugose phase variation in Vibrio cholerae can be mediated by a single nucleotide change that targets c-di-GMP signalling pathway. Mol Microbiol. 2007;63(4):995–1007. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Winzer K, Hardie KR, Williams P. Bacterial cell-to-cell communication: sorry, can’t talk now – gone to lunch! Curr Opin Microbiol. 2002;5:216–222. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(02)00304-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bobrov AG, Bearden SW, Fetherston JD, Khweek AA, Parrish KD, Perry RD. Functional quorum sensing systems affect biofilm formation and protein expression in Yersinia pestis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;603:178–191. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-72124-8_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Choi J, Shin D, Ryu S. Implication of quorum sensing in Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium virulence: the luxS gene is necessary for expression of genes in pathogenicity island 1. Infect. Immun. 2007;75(10):4885–4890. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01942-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Coulthurst SJ, Clare S, Evans TJ, Foulds IJ, Roberts KJ, Welch M, Dougan G, Salmond GP. Quorum sensing has an unexpected role in virulence in the model pathogen Citrobacter rodentium. EMBO Rep. 2007;8(7):698–703. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ali SA, Benitez JA. Differential response of Vibrio cholerae planktonic and biofilm cells to autoinducer 2 deficiency. Microbiol Immunol. 2009;53(10):582–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2009.00161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Freeman JA, Bassler BL. A genetic analysis of the function of LuxO, a two-component response regulator involved in quorum sensing in Vibrio harveyi. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31(2):665–677. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Freeman JA, Bassler BL. Sequence and function of LuxU: a two-component phosphorelay protein that regulates quorum sensing in Vibrio harveyi. J Bacteriol. 1999;181(3):899–906. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.3.899-906.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brackman G, Celen S, Baruah K, Bossier P, Van Calenbergh S, Nelis HJ, Coenye T. AI-2 quorum-sensing inhibitors affect the starvation response and reduce virulence in several Vibrio species, most likely by interfering with LuxPQ. Microbiology. 2009;155(Pt 12):4114–4122. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.032474-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lenz DH, Miller MB, Zhu J, Kulkarni RV, Bassler BL. CsrA and three redundant small RNAs regulate quorum sensing in Vibrio cholerae. Mol Microbiol. 2005;58(4):1186–1202. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pereira CS, de Regt AK, Brito PH, Miller ST, Xavier KB. Identification of functional LsrB-like autoinducer-2 receptors. J. Bacteriol. 2009;191(22):6975–6987. doi: 10.1128/JB.00976-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Showalter RE, Martin MO, Silverman MR. Cloning and nucleotide sequence of luxR, a regulatory gene controlling bioluminescence in Vibrio harveyi. J Bacteriol. 1990;172(6):2946–2954. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.6.2946-2954.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kovacikova G, Skorupski K. Regulation of virulence gene expression in Vibrio cholerae by quorum sensing: HapR functions at the aphA promoter. Mol Microbiol. 2002;46(4):1135–1147. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pompeani AJ, Joseph J, Irgon JJ, Berger MF, Bulyk ML, Wingreen NS, Bassler BL. The Vibrio harveyi master quorum-sensing regulator, LuxR, a TetR-type protein is both an activator and a repressor: DNA recognition and binding specificity at target promoters. Mol Microbiol. 2008;70(1):76–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06389.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tu KC, Bassler BL. Multiple small RNAs act additively to integrate sensory information and control quorum sensing in Vibrio harveyi. Genes Dev. 2007;21:221–233. doi: 10.1101/gad.1502407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lilley BN, Bassler BL. Regulation of quorum sensing in Vibrio harveyi by LuxO and sigma-54. Mol Microbiol. 2000;36(4):940–954. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chirwa NT, Herrington MB. CsgD, a regulator of curli and cellulose synthesis, also regulates serine hydroxymethyltransferase synthesis in Escherichia coli K-12. Microbiology. 2003;149(Pt 2):525–535. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.25841-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Römling U, Bian Z, Hammar M, Sierralta WD, Normark S. Curli fibers are highly conserved between Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli with respect to operon structure and regulation. J Bacteriol. 1998;180(3):722–731. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.3.722-731.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gao R, Stock AM. Biological insights from structures of two-component proteins. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2009;63:133–154. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.091208.073214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yildiz FH, Visick KL. Vibrio biofilms: so much the same yet so different. Trends Microbiol. 2009;17(3):109–118. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Güvener ZT, McCarter LL. Multiple regulators control capsular polysaccharide production in Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J Bacteriol. 2003;185(18):5431–5441. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.18.5431-5441.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Darnell CL, Hussa EA, Visick KL. The putative hybrid sensor kinase SypF coordinates biofilm formation in Vibrio fischeri by acting upstream of two response regulators, SypG and VpsR. J Bacteriol. 2008;190(14):4941–4950. doi: 10.1128/JB.00197-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jyot J, Dasgupta N, Ramphal R. FleQ, the major flagellar gene regulator in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, binds to enhancer sites located either upstream or atypically downstream of the RpoN binding site. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:5251–5260. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.19.5251-5260.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ritchings BW, Almira EC, Lory S, Ramphal R. Cloning and phenotypic characterization of fleS and fleR, new response regulators of Pseudomonas aeruginosa which regulate motility and adhesion to mucin. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4868–4876. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.12.4868-4876.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dasgupta N, Wolfgang MC, Goodman AL, Arora SK, Jyot J, Lory S, Ramphal R. A four-tiered transcriptional regulatory circuit controls flagellar biogenesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol. 2003;50(3):809–824. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Correa NE, Lauriano CM, McGee R, Klose KE. Phosphorylation of the flagellar regulatory protein FlrC is necessary for Vibrio cholerae motility and enhanced colonization. Mol Microbiol. 2000;3:5743–5755. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Canals R, Ramirez S, Vilches S, Horsburgh G, Shaw JG, Tomás JM, Merino S. Polar flagellum biogenesis in Aeromonas hydrophila. J. Bacteriol. 2006;188(2):542–555. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.2.542-555.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ng WL, Bassler BL. Bacterial quorum-sensing network architectures. Annu Rev Genet. 2009;43:197–222. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102108-134304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Park D, Ciezki K, van der Hoeven R, Singh S, Reimer D, Bode HB, Forst S. Genetic analysis of xenocoumacin antibiotic production in the mutualistic bacterium Xenorhabdus nematophila. Mol Microbiol. 2009;73(5):938–949. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06817.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Talà A, De Stefano M, Bucci C, Alifano P. Reverse transcriptase-PCR differential display analysis of meningococcal transcripts during infection of human cells: up-regulation of priA and its role in intracellular replication. BMC Microbiol. 2008;8:131. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-131. 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sha J, Fadl AA, Klimpel GR, Niesel DW, Popov VL, Chopra AK. The two murein lipoproteins of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium contribute to the virulence of the organism. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.7.3987-4003.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.O’Toole GA, Kolter R. Flageller and twitching motility are necessary for Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm development. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:295–304. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Moroshi T, Nakamura Y, Yamazaki G, Ishida A, Kato N, Ikeda T. The plant pathogen Pantoea ananatis produces N-acylhomoserin lactone and causes center rot disease of onion by quorum sensing. J. Bacterial. 2007;189:8333–8338. doi: 10.1128/JB.01054-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hammer BK, Bassler BL. Regulatory small RNAs circumvent the conventional quorum sensing pathway in pandemic Vibrio cholerae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(27):11145–11149. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703860104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hammer BK, Bassler BL. Distinct sensory pathways in Vibrio cholerae El Tor and classical biotypes modulate cyclic dimeric GMP levels to control biofilm formation. J Bacteriol. 2009;191(1):169–177. doi: 10.1128/JB.01307-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sahr T, Brüggemann H, Jules M, Lomma M, Albert-Weissenberger C, Cazalet C, Buchrieser C. Two small ncRNAs jointly govern virulence and transmission in Legionella pneumophila. Mol Microbiol. 2009;72(3):741–762. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06677.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jonas K, Edwards AN, Simm R, Romeo T, Römling U, Melefors O. The RNA binding protein CsrA controls cyclic di-GMP metabolism by directly regulating the expression of GGDEF proteins. Mol Microbiol. 2008;1:236–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06411.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Suzuki K, Babitzke P, Kushner SR, Romeo T. Identification of a novel regulatory protein (CsrD) that targets the global regulatory RNAs CsrB and CsrC for degradation by RNase E. Genes Dev. 2006;20(18):2605–2617. doi: 10.1101/gad.1461606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Baker CS, Morozov I, Suzuki K, Romeo T, Babitzke P. CsrA regulates glycogen biosynthesis by preventing translation of glgC in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 2002;44(6):1599–1610. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wei BL, Brun-Zinkernagel AM, Simecka JW, Prüss BM, Babitzke P, Romeo T. Positive regulation of motility and flhDC expression by the RNA-binding protein CsrA of Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 2001;40(1):245–256. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jonas K, Melefors Ö, Römling U. Regulation of c-di-GMP metabolism in biofilms. Future Microbiol. 2009;4(3):341–358. doi: 10.2217/fmb.09.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lenz DH, Bassler BL. The small nucleoid protein Fis is involved in Vibrio cholerae quorum sensing. Mol Microbiol. 2007;63(3):859–871. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure I. Reverse-transcription PCR analysis of aha0701h gene encoding GGDEF domain protein (A) and 16S RNA as a reference (B) in: 1. WT A. hydrophila SSU; 2. ΔluxS mutant of A. hydrophila SSU; 3. ΔahyRI mutant of A. hydrophila SSU.