Abstract

In yeast, a single form of TFIIIB is required for transcription of all RNA polymerase III (pol III) genes. It consists of three subunits: the TATA box-binding protein (TBP), a TFIIB-related factor, BRF, and B′′. Human TFIIIB is not as well defined and human pol III promoters differ in their requirements for this activity. A human homolog of yeast BRF was shown to be required for transcription at the gene-internal 5S and VA1 promoters. Whether or not it was also involved in transcription from the gene-external human U6 promoter was unclear. We have isolated cDNAs encoding alternatively spliced forms of human BRF that can complex with TBP. Using immunopurified complexes containing the cloned hBRFs, we show that while hBRF1 functions at the 5S, VA1, 7SL and EBER2 promoters, a different variant, hBRF2, is required at the human U6 promoter. Thus, pol III utilizes different TFIIIB complexes at structurally distinct promoters.

Keywords: hBRF/RNA polymerase III/snRNA

Introduction

Yeast RNA polymerase III (pol III) is recruited to its cognate promoters primarily via interaction with transcription factor IIIB (TFIIIB) (reviewed in Kumar et al., 1998). Yeast TFIIIB consists of three subunits: the TATA-box binding protein (TBP) (Huet and Sentenac, 1992; Kassavetis et al., 1992), BRF/PCF4/TDS4, a 67 kDa protein related to TFIIB (Buratowski and Zhou, 1992; Colbert and Hahn, 1992; Lopez-De-Leon et al., 1992), and B′′/TCF5, a 90 kDa protein (Kassavetis et al., 1995; Roberts et al., 1996; Ruth et al., 1996). All three subunits of TFIIIB are required for transcription of the yeast tRNA, 5S RNA and U6 small nuclear RNA (snRNA) genes (Kassavetis et al., 1990; Huet et al., 1994; Joazeiro et al., 1994); however, these genes differ in the mechanism by which they recruit TFIIIB. TFIIIB cannot bind independently to the 5S or tRNA promoters, but is instead recruited by factors that are already bound to the DNA (Kassavetis et al., 1990). In the case of the 5S promoter, TFIIIA binds the internal control region and is followed by binding of TFIIIC. In contrast, tRNA promoters consist of gene-internal A and B boxes that directly bind TFIIIC. The binding of TFIIIC to the 5S and tRNA promoters is followed by the recruitment of TFIIIB. TFIIIA and TFIIIC can be removed in vitro by treatment with high salt or heparin, leaving TFIIIB stably bound upstream of the transcription initiation site. TFIIIB, in the absence of any other basal factors, can then direct multiple rounds of transcription by pol III from these genes (Kassavetis et al., 1990). A gene-internal A box, a B box in the 3′-flanking sequence and TFIIIC are required for U6 transcription in vivo (Brow and Guthrie, 1990; Eschenlauer et al., 1993). However, the U6 gene also contains an upstream TATA box that can bind TFIIIB directly, so that in vitro the B box and TFIIIC are not required (Joazeiro et al., 1994; Gerlach et al., 1995; Whitehall et al., 1995).

The vertebrate pol III transcription apparatus is less well characterized than that of yeast. Vertebrate pol III promoters are more diverse and are classified on the basis of their structures (reviewed in Willis, 1993). Type I genes, exemplified by the 5S RNA gene, contain an internal control region. The presence of gene-internal A and B boxes characterizes the type II tRNA and adenovirus2 VA1 RNA genes. In contrast, the promoters of the type III genes lie entirely upstream of the RNA coding sequences. The basal human U6 promoter, a type III promoter, consists of a TATA box that binds TBP in vitro, and a proximal sequence element (PSE) (Das et al., 1988; Kunkel and Pederson, 1989; Lobo and Hernandez, 1989) that binds the SNAPc/PTF complex (Sadowski et al., 1993; Yoon et al., 1995). TFIIIA and TFIIIC are not required for transcription of the human U6 snRNA gene in vitro (Reddy, 1988; Waldschmidt et al., 1991; Kuhlman et al., 1999). In addition to these three types of genes, there are several that have gene-internal A and B box homologies as well as upstream promoter elements. Among these are the human 7SL gene, the Epstein–Barr virus-encoded EBER1 and EBER2 RNA genes, the Xenopus selenocysteine tRNA gene and the vault RNA gene (reviewed in Willis, 1993).

Several lines of evidence suggest that different forms of TFIIIB are required at TATA-less and TATA box-containing promoters. First, human U6 transcription can be reconstituted by the addition of recombinant TBP to a TBP-depleted nuclear extract. In contrast, transcription from the TATA-less VA1, 5S and 7SL promoters can only be restored by the addition of a partially purified 300 kDa TBP-containing complex, 0.38M TFIIIB (Lobo et al., 1992). Secondly, Teichmann and Seifart (1995) identified two forms of TFIIIB, TFIIIB-α and TFIIIB-β, required for transcription of the human U6 and VA1 genes, respectively. Thirdly, Wang and Roeder (1995) isolated a cDNA encoding a 90 kDa human homolog of yeast BRF, TFIIIB90. Like yeast BRF, the N-terminal half of TFIIIB90 is related to the RNA pol II transcription factor TFIIB and contains a Zn2+-binding domain and two imperfect direct repeats. Transcription of the U6 and VA1 genes was abolished in a nuclear extract depleted with polyclonal antibodies against full-length TFIIIB90, but only VA1 transcription could be restored by the addition of recombinant TFIIIB90 and TBP. That U6 transcription was not reconstituted in this way was interpreted to mean that a TFIIIB90-containing complex, distinct from that involved in transcription of the 5S and tRNA genes, was required by U6. Finally, Mital et al. (1996) immunodepleted extracts using antibodies directed against the C-terminal 14 amino acid peptide of TFIIIB90, which they had cloned independently and named hBRF. Removal of >95% of this protein from an extract had no effect on U6 transcription, whereas VA1 transcription was abolished, suggesting that hBRF is not required for U6 transcription.

Here we report the cloning of cDNAs encoding variant forms of human BRF that are derived from a single gene by alternative splicing. We refer to the 90 kDa version cloned by Wang and Roeder (1995) and Mital et al. (1996) as hBRF1 and to the other variants as hBRFs 2, 3 and 4. Each variant contains one of the direct repeats found in yeast BRF and hBRF1. We show that all the variants can enter into complexes with TBP and have mapped the domains of each variant that mediate this interaction. We report that hBRF1 is the most active variant in transcription from the 5S, VA1, 7SL and EBER2 promoters, whereas hBRF2 is required for transcription from the U6 promoter. These findings suggest that multiple versions of TFIIIB that differ in composition and function exist in human cells.

Results

Isolation of cDNAs encoding hBRF variants

A human cDNA library (Foster et al., 1999) was screened with a probe derived from hBRF (Mital et al., 1996) and four different hBRF variants were obtained (Figure 1). Partial cDNAs encoding hBRF1 were isolated four times. Two independent isolates of hBRF3 were obtained and one each of hBRFs 2 and 4. Sequences corresponding to the 3′ end of the hBRF4 mRNA are represented in the expressed sequence tag (EST) database (DDBJ/ EMBL/GenBank accession Nos N91109, AI806823 and W20443).

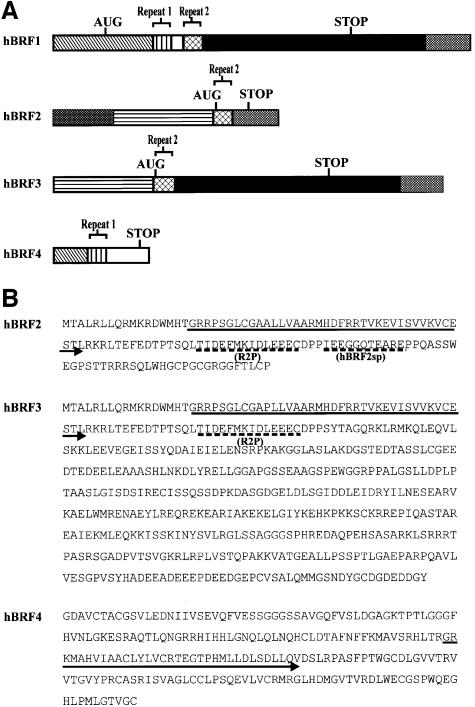

Fig. 1. Structure of hBRF variants. (A) Schematic representation of variant cDNAs. Translation start (AUG) and stop sites (STOP) are indicated. Repeat 1 and Repeat 2 refer to the regions encoding the imperfect repeats homologous to TFIIB. (B) Amino acid sequences of hBRFs 2, 3 and 4. Arrows indicate the repeat regions. Dashed lines indicate the peptides R2P and hBRF2sp used for raising antibodies. (C) The specificity of anti-peptide antibodies. hBRFs 1–4 were translated in vitro (lanes 1–4) and immunoprecipitated with purified anti-R2P (lanes 5–8) or anti-hBRF2sp antibodies (lanes 9–12).

hBRF3 is identical to hBRF1 except that it is N-terminally truncated by the presence of an untranslated 5′ sequence that replaces the region encoding repeat 1 and the Zn2+-binding domain of hBRF1 (Figure 1A). It encodes a 473 amino acid protein (Figure 1B) that migrates at ∼70 kDa on SDS–polyacrylamide gels (Figure 1C, lane 3). The hBRF2 cDNA also contains this 5′-untranslated region, with an additional 500 bp upstream (Figure 1A). Translation of hBRF2, a 139 amino acid protein (Figure 1B) that migrates at ∼23 kDa (Figure 1C, lane 2), initiates at the same methionine as hBRF3. It contains repeat 2 but, after this, a region that is present in hBRFs 1 and 3 is skipped, bringing the sequence downstream of the stop codon in hBRFs 1 and 3 into frame with repeat 2. The hBRF4 cDNA is incomplete and contains part of the Zn2+-binding region, repeat 1 and a region of 86 amino acids that is not homologous to any protein (Figure 1A and B). It encodes a 225 amino acid protein that migrates at ∼25 kDa (Figure 1C, lane 4).

The hBRF variants are not library artifacts or products of a gene family as a BAC clone containing part of the hBRF gene, including the unique region of hBRF4, the 5′-untranslated leader of hBRFs 2 and 3 and the regions common to hBRFs 1 and 3, has been sequenced (DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession No. AF11170). Furthermore, we have isolated an ∼100 kb human genomic P1 clone that contains the regions unique to all of the variants. The characterization of this clone and the intron–exon structure of the hBRF gene will be described elsewhere (V.McCulloch, J.Grams, W.Peng and S.Lobo-Ruppert, in preparation).

Polyclonal antisera were raised against two peptides: R2P, located distal to repeat 2 in hBRFs 1, 2 and 3, and hBRF2sp, an hBRF2-specific peptide (Figure 1B). To confirm the specificity of the antibodies, the hBRFs were translated in vitro (Figure 1C, lanes 1–4) and used in non-denaturing immunoprecipitations (lanes 5–12). Anti-R2P antibodies precipitated the repeat 2-containing hBRFs 1, 2 and 3 (Figure 1C, lanes 5, 6 and 7) but not hBRF4 (lane 8), whereas the anti-hBRF2sp antibodies brought down only hBRF2 (compare lane 10 with lanes 9, 11 and 12). As equal amounts of hBRF2 (five times that shown in the input lane, Figure 1C, lane 2) were used in lanes 10 and 6, the anti-hBRF2sp antibody precipitates hBRF2 less efficiently than does the anti-R2P antibody. The anti-hBRF2sp antibodies do not precipitate or deplete hBRF2 from HeLa nuclear extracts although they detect a protein of the size of hBRF2 in immunoblots of nuclear extracts (Figure 7B, lanes 3 and 4), suggesting that the cognate epitope is masked in the native protein.

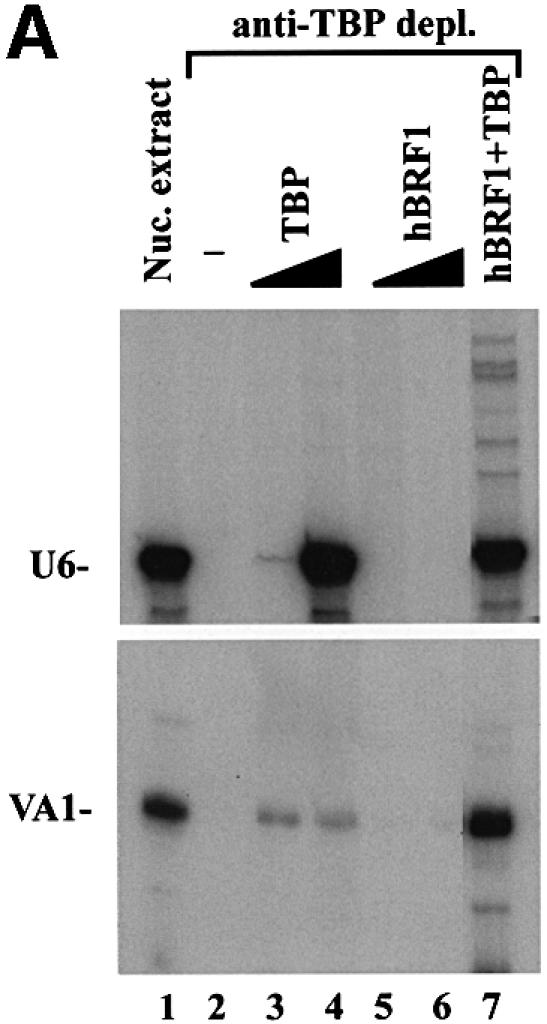

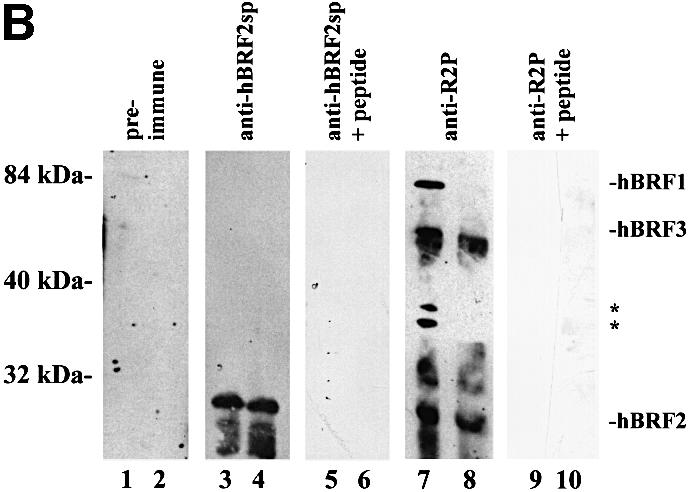

Fig. 7. U6, but not VA1, transcription is restored by the addition of recombinant TBP alone to a TBP-depleted nuclear extract. (A) Reconstitution of U6 and VA1 transcription from a TBP-depleted nuclear extract. HeLa nuclear extract was either untreated (lane 1) or immunodepleted with anti-TBP mAbs (lanes 2–7). Recombinant TBP (0.2 and 0.66 fpu; lanes 3 and 4), in vitro translated hBRF1 (3 and 5 µl; lanes 5 and 6) or 0.66 fpu of TBP in combination with 5 µl of hBRF1 (lane 7) were added to the TBP-depleted extract. (B) Anti-TBP mAbs co-deplete hBRF1 but not hBRF2 from nuclear extract. Nuclear extract depleted with anti-TBP mAbs (lanes 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10) or not (lanes 1, 3, 5, 7 and 9) was immunoblotted with pre-immune serum (lanes 1 and 2), anti-hBRF2sp antibodies (lanes 3 and 4), anti-hBRF2sp antibodies + hBRF2sp peptide (lanes 5 and 6), anti-R2P antibodies (lanes 7 and 8) or anti-R2P antibodies + R2P peptide (lanes 9 and 10). Molecular weight markers are indicated on the left.

The variant hBRFs form complexes with human TBP in vitro

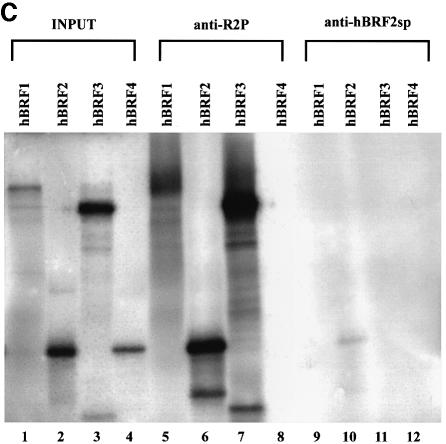

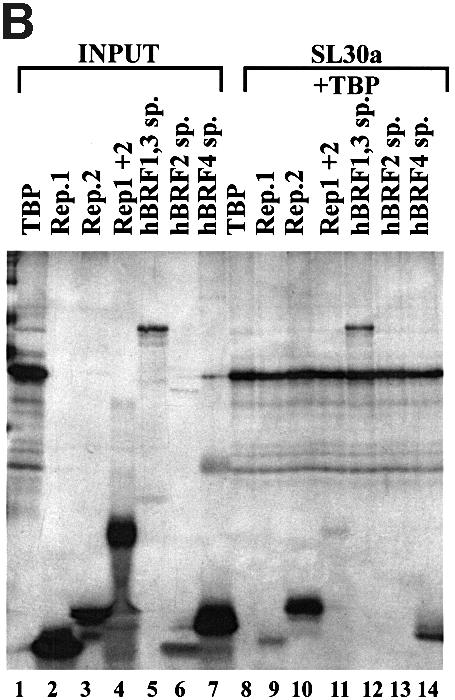

hBRF1 binds TBP in vitro through the TFIIB homology region and, more avidly, through its C-terminal half (Wang and Roeder, 1995; Mital et al., 1996). To determine whether hBRFs 2, 3 or 4 enter into complexes with TBP, they were translated in vitro, mixed with TBP and used in co-immunoprecipitations with the monoclonal antibody (mAb) SL30a, which recognizes human TBP (Ruppert et al., 1996) (Figure 2A). The firefly luciferase (luc) protein was assayed in parallel as a negative control. Ethidium bromide was added to preclude the possibility that DNA might mediate interactions between these proteins (Lai and Herr, 1992). The individually translated input proteins are shown in Figure 2A (lanes 1–6). Under non-denaturing conditions, all of the variants (lanes 14–17), but not luc (lane 13), were brought down with TBP. When 0.5% NP-40 was included in these reactions, only hBRFs 1 and 3 were co-immunoprecipitated with TBP (not shown), indicating that these two variants form stronger complexes with TBP than do hBRFs 2 and 4. When the assay was done in RIPA buffer, the detergents present disrupted protein–protein interactions so that only TBP was immunoprecipitated (Figure 2A, lanes 7–12). The assay was also performed without added TBP, and none of the hBRFs was brought down (Figure 2A, lanes 23–26), confirming that the antibody does not recognize an epitope on any of the variants. Thus, like hBRF1, hBRFs 2, 3 and 4 can enter into complexes with TBP in vitro.

Fig. 2. Characterization of interactions between hBRF variants and TBP. (A) Co-immunoprecipitation of in vitro translated hBRFs with TBP. The hBRF variants, TBP and luc were translated in vitro (lanes 1–6), incubated with TBP in either RIPA buffer (lanes 7–12) or buffer D + 300 mM KCl (lanes 13–18) or without TBP in buffer D + 300 mM KCl (lanes 23–26) and immunoprecipitated with anti-TBP mAb SL30a. (B) Identification of hBRF domains that mediate interactions with TBP. hBRF domains were translated in vitro (lanes 1–6) mixed with TBP and immunoprecipitated with SL30a (lanes 8–14). The different domains are indicated above the lanes: Rep.1, repeat 1; Rep.2, repeat 2; Rep1 + 2, repeat 1 and 2 together; hBRF1,3 sp., C-terminal domain of hBRFs 1 and 3; hBRF2 sp., C-terminal domain unique to hBRF2; hBRF4 sp., C-terminal domain unique to hBRF4.

To determine which hBRF domains are required for complex formation with TBP (Figure 2B), repeat 1 (lane 2), repeat 2 (lane 3), the two repeats together (lane 4), the C-terminal domain common to hBRFs 1 and 3 (lane 5), and the unique regions of hBRF2 (lane 6) and hBRF4 (lane 7) were translated, mixed with TBP and immunoprecipitated with SL30a (lanes 8–14). Except for the unique region of hBRF2 (Figure 2B, lane 13), all of these truncations (lanes 9–12 and 14) were co-immunoprecipitated detectably with TBP under our conditions. When the assay was performed in the presence of 0.5% NP-40, only the C-terminal region of hBRFs 1 and 3 was brought down with TBP (not shown). This robust interaction may account for the increased strength of association of hBRFs 1 and 3 with TBP.

hBRF variants can reconstitute at least basal levels of transcription from various pol III promoters

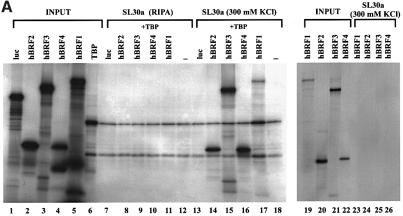

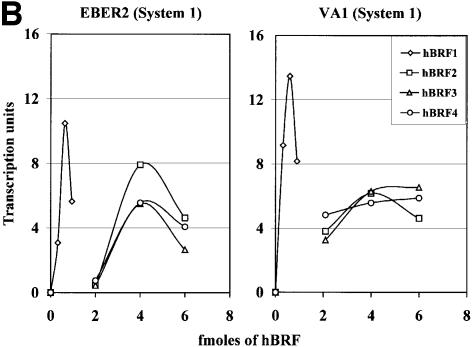

The ability of the hBRF variants to form complexes with TBP raises the possibility that, like hBRF1 and yeast BRF, they may function in transcription by pol III. To examine this possibility, increasing amounts of each variant or the luc control were used in combination with constant amounts of recombinant TBP and the phosphocellulose C fraction to transcribe pol III templates (reconstitution system 1; Figure 3A). In vitro translated hBRF proteins were used, as some of the variants are poorly expressed or insoluble when produced in bacteria. The amounts of hBRFs 2, 3 and 4 used were equalized by phosphoimager analysis. As hBRF1 translates poorly and its transcriptional activity is saturating at lower concentrations, less of this protein (0.3, 0.6 or 0.9 fmol) as compared with the other variants (2, 4 or 6 fmol) was added. Combining phosphocellulose B and C fractions reconstitutes high levels of EBER2 and VA1 transcription (Figure 3A, lane 5) and serves as a positive control. When the B fraction was replaced by hBRF1 and TBP, levels of activity comparable to that of the positive control were obtained from both genes (Figure 3A, compare lanes 9–11 and lane 5). Surprisingly, hBRFs 2, 3 and 4 also stimulate transcription above background levels (Figure 3A, compare lanes 12–14, 15–17, 18–20 and 6–8) but below those obtained with hBRF1 (lanes 9–11). These results are summarized in Figure 3B, in which transcription units (determined by densitometric analysis of the transcripts, with background luc transcription subtracted) are plotted as a function of the amount of hBRF added. Thus, in system 1, activity peaked at 0.6 fmol for hBRF1 whereas addition of higher amounts (4–6 fmol) of the other hBRFs did not stimulate transcription to the same extent as hBRF1. Similar results were obtained with the 7SL gene (J.Grams and V.McCulloch, not shown).

Fig. 3. Reconstitution of pol III transcription using in vitro translated hBRFs, TBP and phosphocellulose fraction C. (A) Transcription of VA1 and EBER2 genes. Transcription was assayed using fraction C alone (lane 4), C + TBP (lane 1), C + luc (lane 2), luc + TBP (lane 3), the phosphocellulose B and C fractions (lane 5) and increasing amounts of luc (lanes 6–8) or each in vitro translated hBRF (lanes 9–20) with 0.1 µl of TBP and the C fraction. The amounts of hBRFs or luc added (in fmoles) are indicated above the lanes. (B) Graphical representation of the results from (A).

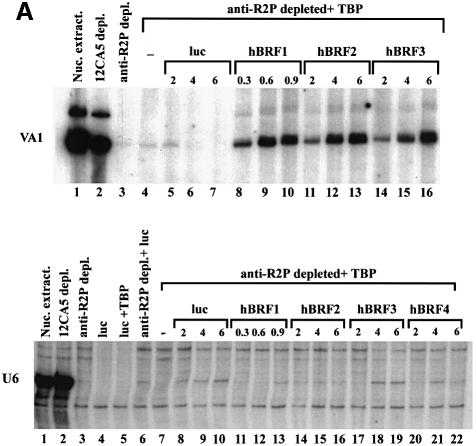

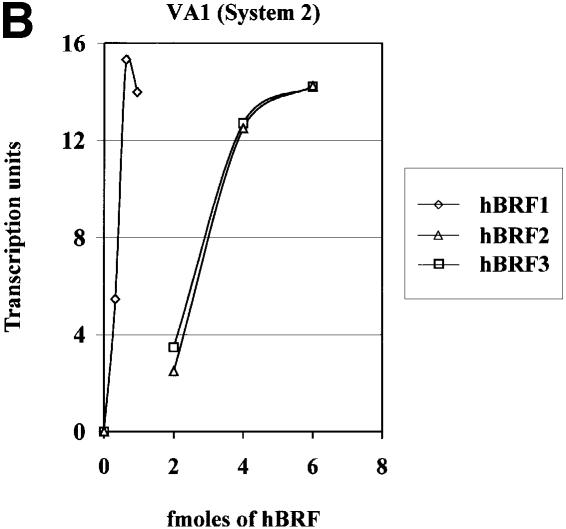

The hBRF variants were also tested in the same way on the human U6 template, but none was able to reconstitute transcription (not shown). As this could be due to a requirement for multiple components of the B fraction, we tried a second approach. HeLa nuclear extracts contain several proteins that are recognized in immunoblots by anti-R2P antibodies (Figure 7B, lane 7), and are removed by depletion with these antibodies (not shown), resulting in inhibition of VA1 and U6 transcription (Figure 4A, compare lane 3 with lane 1 in each panel). Increasing amounts of hBRFs 1, 2 or 3 were then added in combination with TBP to the depleted extract (reconstitution system 2; Figure 4A). In system 2, as in system 1, hBRF1 is the most active variant on the VA1 promoter (Figure 4A, lanes 8–10) while hBRFs 2 and 3 showed lower levels of activity per fmole (lanes 11–16). The results are shown graphically in Figure 4B. However, U6 transcription was not reconstituted in system 2 (Figure 4A, U6 panel, compare lanes 11–22 with lane 1). All possible combinations of the hBRF variants were tested, with additive effects, at best, on VA1 transcription; however, U6 transcription was not reconstituted (not shown). Our results suggest that a modified version of one of the cloned hBRFs, additional components or an unidentified repeat 2-containing hBRF may be required for U6 transcription.

Fig. 4. Reconstitution of pol III transcription using in vitro translated hBRFs, TBP and anti-R2P antibody-depleted extract. (A) Transcription of the VA1 and U6 genes. VA1 and U6 transcription were assayed in nuclear extract (lane 1), 12CA5 mAb-depleted extract (lane 2), anti-R2P antibody-depleted extract (lane 3) or in anti-R2P antibody-depleted extract complemented with the indicated proteins. The numbers above the lanes indicate the fmoles of luc or hBRF added. (B) Graphical representation of the results from the upper panel in (A).

Isolation of complexes containing hBRF variants

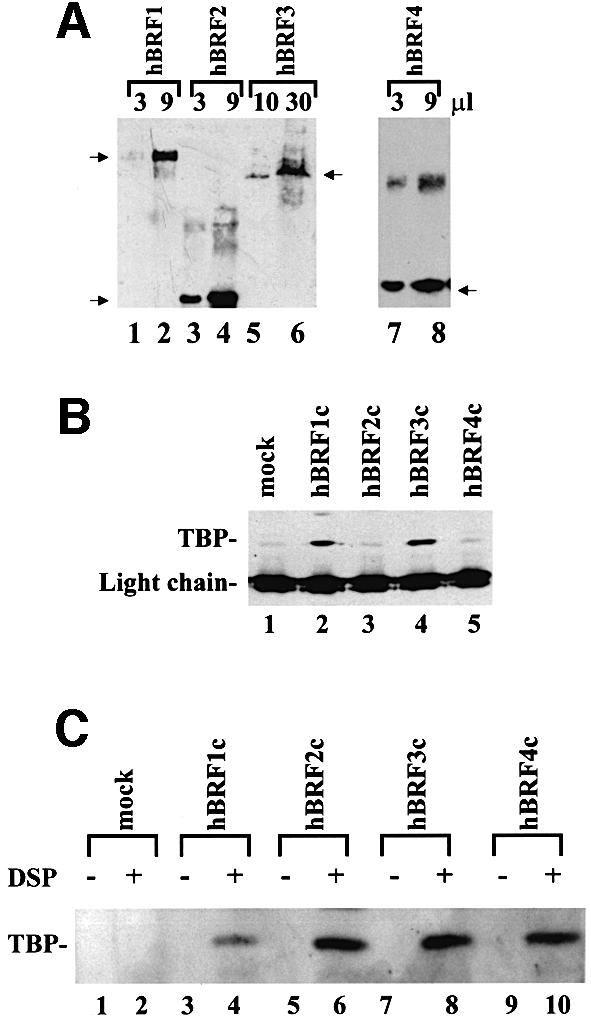

We next examined the possibility that complexes containing hBRFs 1, 2 or 3 may be involved in U6 transcription. An N-terminally hemagglutinin (HA) epitope-tagged version of each hBRF was introduced into the human embryonal kidney cell line BOSC 23 (Pear et al., 1993) by transient transfection. hBRF complexes were immunopurified from these cells, eluted with HA-peptide and immunoblotted with 12CA5 mAb to verify the expression of each hBRF (Figure 5A). Immunoblotting with anti-R2P antibodies (not shown) detected only the transfected hBRF in each complex, suggesting that multiple repeat 2-containing hBRFs are not present within a single complex. Since hBRF4 is incomplete and we do not have antibodies against it, the possibility that it may co-exist with a repeat 2-containing hBRF in a complex cannot be excluded. To detect associated TBP, hBRF complexes were immunoblotted with a mixture of three anti-TBP mAbs, SL2a, SL26a and SL30a (Ruppert et al., 1996). TBP was co-immunoprecipitated with hBRFs 1 and 3 (Figure 5B, lanes 2 and 4). A background band of the approximate size of TBP is seen in the HA eluates derived from cells transfected with vector alone (Figure 5B, lane 1) or with hBRFs 2 and 4 (lanes 3 and 5). However, if the extracts are treated with the protein cross-linking reagent dithiobis[succinimidylpropionate] (DSP) prior to incubation with 12CA5 mAb, then TBP is brought down with all the hBRFs under denaturing conditions (Figure 5C, lanes 4, 6, 8 and 10).

Fig. 5. Characterization of hBRF complexes assembled in human cells. (A) Detection of purified HA epitope-tagged hBRFs transiently expressed in human cells. Increasing amounts of each hBRF complex were immunoblotted with 12CA5 mAb. Arrows indicate the location of the hBRF variants on the gel. (B) TBP is present in hBRF1 and hBRF3 complexes. hBRF complexes were immunoblotted with anti-TBP mAbs. The light chain of the 12CA5 mAb and TBP are indicated. (C) Cross-linking of TBP to hBRFs expressed in human cells. Extracts from BOSC 23 cells transiently transfected with vector alone (lanes 1 and 2) or HA epitope-tagged hBRF variants (lanes 3–10) were either treated with the cross-linking agent DSP or not (indicated by + or – above the lanes) and immunoprecipitated with 12CA5 mAb under denaturing conditions. The immunoprecipitated proteins were immunoblotted with anti-TBP mAbs.

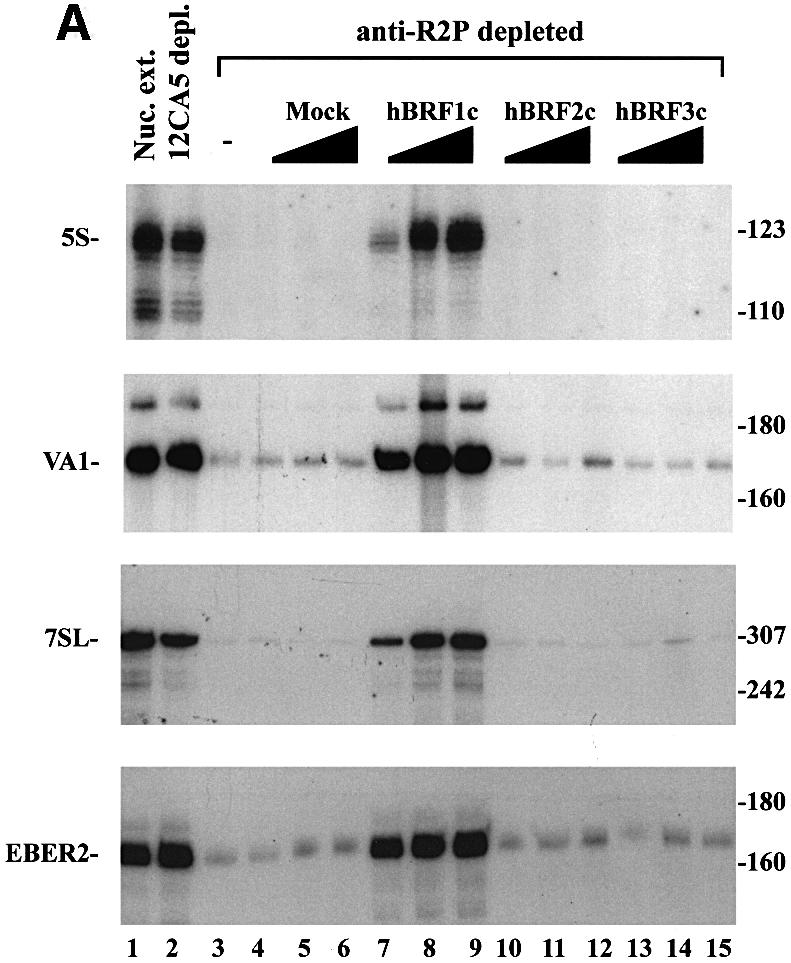

Reconstitution of transcription from the 5S, 7SL, VA1, EBER2 and U6 promoters using hBRF complexes

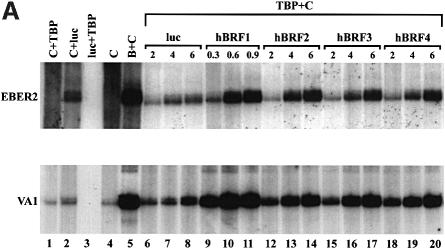

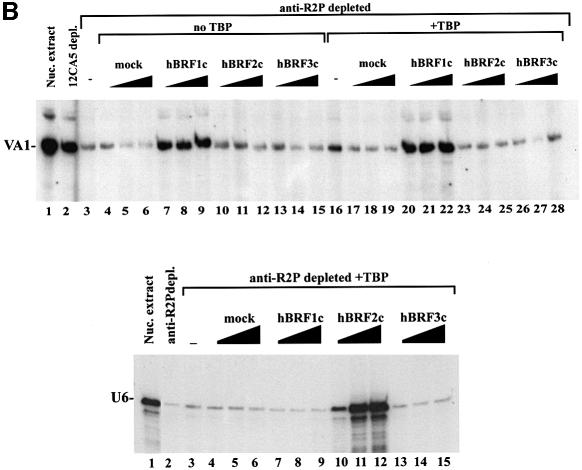

Complexes containing HA-tagged hBRFs were isolated from transfected cells, immunoblotted with 12CA5 mAb, quantitated by densitometry, and the concentrations of the hBRFs were equalized. Transcription was assayed by adding increasing amounts of each complex to a HeLa nuclear extract depleted with anti-R2P antibodies. This depletion debilitates transcription of the 5S, VA1, 7SL and EBER2 genes (Figure 6A, compare lanes 3 and 1), while depletion with 12CA5 mAb does not (compare lanes 2 and 1). hBRF1-containing complexes restore transcription from these promoters (Figure 6A, lanes 7–9), whereas proteins isolated from mock-transfected cells (lanes 4–6) or complexes that contain hBRFs 2 or 3 (lanes 10–15) do not. Loss of TBP during complex purification does not account for the inability of hBRFs 2 and 3 to reconstitute transcription. hBRF1-containing complexes restore transcription from the VA1 promoter either with or without exogenous TBP (Figure 6B, lanes 7–9 and 20–22, VA1 panel), but exogenous TBP does not allow hBRF2- or hBRF3-containing complexes to support VA1 transcription (Figure 6B, compare lanes 10–15 and 23–28). The addition of luc-programmed reticulocyte lysate, TBP and hBRF complexes to anti-R2P antibody-depleted extract (not shown) gave essentially the same results with VA1 as with the complexes alone. In contrast, when anti-R2P antibody-depleted extract was complemented with in vitro translated hBRFs 2 or 3 and TBP (system 2, Figure 4A) VA1 transcription was restored. A likely explanation is that component(s) present in the hBRF 2 and 3 complexes prevent them from functioning at this promoter.

Fig. 6. Reconstitution of pol III transcription using hBRF complexes assembled in human cells. (A) Reconstitution of 5S, VA1, 7SL and EBER2 transcription. HeLa nuclear extract (lane 1) was depleted with either 12CA5 mAb (lane 2) or anti-R2P antibodies (lanes 3–15). Increasing amounts of complexes isolated from cells transfected with vector (lanes 4–6) or epitope-tagged hBRFs (lanes 7–15) were added to anti-R2P-depleted nuclear extract. The sizes (in bp) of molecular weight markers are indicated on the right. (B) Reconstitution of VA1 transcription using anti-R2P antibody-depleted extract and hBRF complexes in the presence (lanes 16–28) or absence (lanes 3–15) of exogenous TBP. Reconstitution of U6 transcription in anti-R2P antibody-depleted extracts. In the lower panel, U6 transcription was assayed in nuclear extract (lane 1), depleted extract (lane 2), depleted extract + TBP (lane 3) or with depleted extract, TBP and increasing amounts of the indicated hBRF complexes (lanes 4–15).

We next assayed the complexes for their ability to restore U6 transcription to an extract depleted with anti-R2P antibodies (Figure 6B, U6 panel). In the absence of exogenous TBP, none of the hBRF complexes restored U6 transcription (not shown). However, when TBP was also added, hBRF2 complexes restored U6 transcription to a level comparable to that of undepleted extract (Figure 6B, compare lanes 10–12 and lane 1), whereas TBP alone (lane 3), or complexes from mock-transfected cells (lanes 4–6) or from cells expressing hBRFs 1 or 3 (lanes 7–9 and lanes 13–15) did not. Exogenous TBP is required because it may be depleted with hBRF2 from the extract by the anti-R2P antibodies, and subsequently lost by washing during purification. These results show that at the VA1, 5S, 7SL and EBER2 promoters, in which gene-internal elements that can potentially bind TFIIIC have been identified (reviewed in Willis et al., 1993), hBRF1 is required for transcription. In contrast, at the human U6 promoter, which does not require TFIIIC (Reddy, 1988; Waldschmidt et al., 1991; Kuhlman et al., 1999), hBRF2 is used preferentially.

Anti-TBP antibodies deplete hBRF1–TBP complexes but disrupt hBRF2–TBP complexes

TBP alone is sufficient to restore U6 transcription to a nuclear extract immunodepleted of TBP, whereas a TBP-containing fraction, 0.38M TFIIIB, is required to reconstitute transcription from the VA1, 5S and 7SL promoters (Lobo et al., 1992). If hBRF2 does indeed function in U6 transcription, then depletion of an extract with anti-TBP mAbs would be expected to disrupt its interaction with TBP, leaving it behind, whereas hBRF1 would be depleted with TBP. To test this prediction, we depleted a HeLa nuclear extract with a mixture of three anti-TBP mAbs, SL2a, SL33b and SL35a (Ruppert et al., 1996), resulting in reduced U6 and VA1 transcription (Figure 7A, compare lanes 1 and 2). Addition of increasing amounts of recombinant TBP restored U6 but not VA1 transcription (Figure 7A, compare lanes 3 and 4 with lane 2). Addition of hBRF1 (Figure 7A, lanes 5 and 6) had no effect on transcription of either gene, nor did the addition of hBRF1 and TBP increase U6 transcription beyond the level obtained with TBP alone (compare lanes 7 and 4). In contrast, addition of hBRF1 and TBP stimulated VA1 transcription to levels comparable to undepleted extract (Figure 7A, compare lanes 7 and 1), consistent with the results of Mital et al. (1996). The undepleted and depleted extracts were immunoblotted with anti-R2P (Figure 7B, lanes 7 and 8) and anti-hBRF2sp (lanes 3 and 4) anti bodies. A band the size of hBRF1 that is present in the undepleted extract disappears upon depletion with anti-TBP mAbs, whereas a band of the size of hBRF2 is unaffected (Figure 7B, compare lanes 7 and 8). Immunoblotting with anti-R2P antibodies also detects a protein that corresponds in size to hBRF3 and two unknown proteins, indicated by asterisks (Figure 7B, lane 7). The anti-hBRF2sp antibodies detect a band of the size of hBRF2 in the depleted and the undepleted extracts (Figure 7B, lanes 3 and 4). None of these proteins is detected by pre-immune serum (Figure 7B, lanes 1 and 2) or when the anti-hBRF2sp and anti-R2P antibodies were pre-incubated with their cognate peptides prior to immunoblotting (lanes 5, 6, 9 and 10). Therefore, anti-TBP mAbs co-deplete hBRF1 from a nuclear extract but disrupt the hBRF2–TBP complex.

Discussion

Distinct hBRF complexes are required at different pol III promoters

Several observations suggest that multiple versions of TFIIIB, defined minimally as an hBRF and TBP, may exist in human cells. First, we have cloned three variant hBRFs, and immunoblotting with anti-R2P antibodies shows that multiple hBRFs are expressed in human cells (Figure 7B, lane 7). Secondly, all of our variants can enter into complexes with TBP (Figure 5C) and, thirdly, the hBRF1- and hBRF2-containing complexes function in transcription (Figure 6). We did not detect multiple repeat 2-containing hBRFs in a single complex, suggesting that hBRFs 1, 2 and 3 may form independent complexes with TBP. A cloned human homolog of yeast B′′ is required for transcription of the 7SK and VA1 genes in vitro (Teichmann et al., 1999) and, like TBP, may be a shared component of the hBRF1 and hBRF2 complexes.

Our demonstration that hBRF2 is used preferentially at the U6 promoter, whereas hBRF1 functions at the VA1, 5S, EBER2 and 7SL promoters, is consistent with published data. Wang and Roeder (1995) showed that the addition of both hBRF1 and TBP could restore the ability of a HeLa extract immunodepleted with polyclonal anti-hBRF1 antibodies to transcribe the VA1 and tRNA genes. However, U6 transcription could not be reconstituted in this way. A likely explanation is that the polyclonal anti-hBRF antibodies used in these studies cross-reacted with hBRF2 and depleted it from the extract. Mital et al. (1996) used an antibody directed against a C-terminal peptide of hBRF1 to deplete a HeLa extract and found that while VA1 transcription was abolished, U6 transcription was unaffected. As hBRF2 does not contain this epitope, it would not be depleted in this experiment, leaving U6 activity intact.

That hBRF1–TBP complexes are more stable than hBRF2–TBP complexes is consistent with the published properties of the different forms of TFIIIB required at the VA1 and U6 promoters. Both repeats, as well as the C-terminal half of hBRF1, can interact with TBP (Wang and Roeder, 1995), whereas the complex between hBRF2 and TBP appears to be mediated only by repeat 2 (Figure 2B). The hBRF2–TBP complex is disrupted by 0.5% NP-40; the interaction of hBRF1 with TBP is not. TBP can only be detected in hBRF2 complexes by cross-linking with DSP, but it can be found in hBRF1 complexes without this treatment (Figure 5). Furthermore, anti-TBP mAbs disrupt hBRF2–TBP complexes but not hBRF1–TBP complexes (Figure 7). This explains why addition of 0.38M TFIIIB (Lobo et al., 1992) or hBRF1 plus TBP to a TBP-depleted extract (Figure 7A; Mital et al., 1996) restores VA1 activity, whereas reconstitution of U6 transcription requires only TBP.

Consistent with the roles of hBRFs 1 and 2 in the transcription of ubiquitously expressed genes, immunoblotting with anti-R2P antibody detects bands corresponding in size to these variants in every human cell line that we examined. These included the HeLa (cervical carcinoma; Figure 7B, lane 7), BOSC 23 (embryonal kidney), 19LU (lung epithelium), HepG2 (hepatoma), K562 (erythroleukemia), Hawkins (melanoma), MCF7 (breast carcinoma) and LoVo (colorectal cancer) cell lines (not shown).

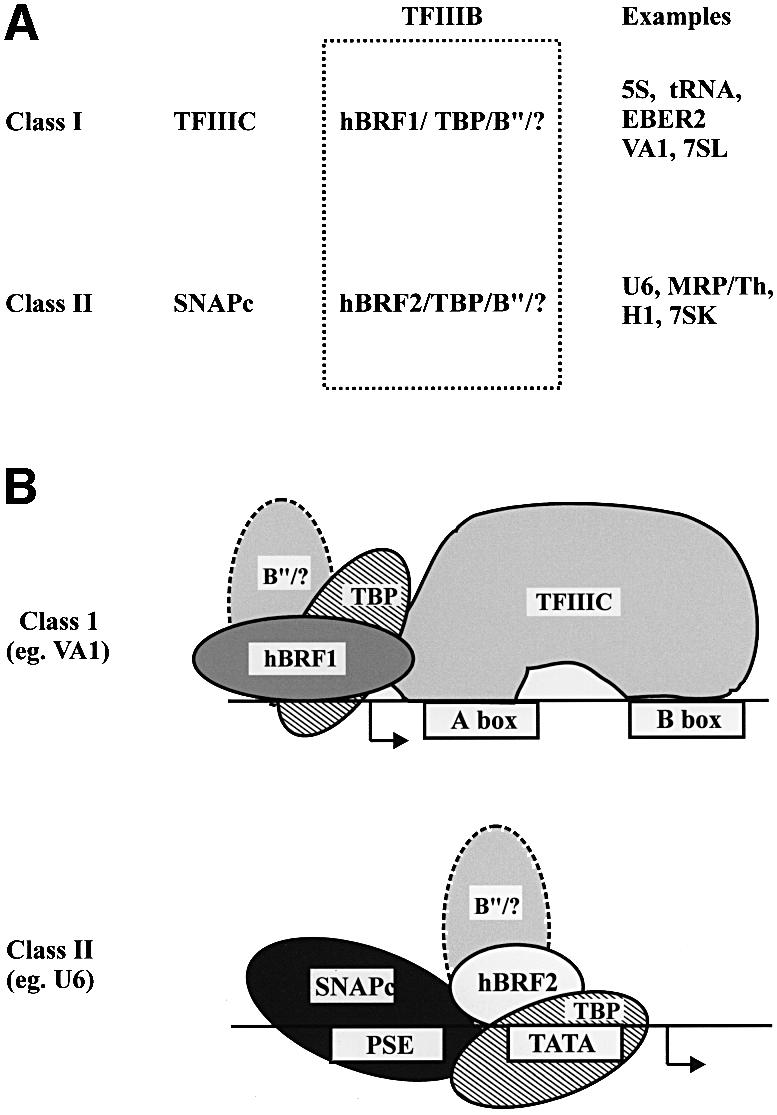

Two major classes of RNA pol III promoter

We propose the model shown in Figure 8, similar to that of Mital et al. (1996), which is consistent with a role for the hBRFs as molecular adaptors between factors that bind to different pol III promoters and RNA pol III. The VA1, 5S, tRNA and 7SL genes require TFIIIC for transcription in vitro, and the EBER2 gene contains functional A and B boxes (reviewed in Willis, 1993; Muller and Benecke, 1999). hBRF1, which is required at these promoters, interacts with the 90, 63 and 102 kDa subunits of human TFIIIC (Hsieh et al., 1999a,b) and thus serves as an adaptor between TFIIIC and pol III.

Fig. 8. Schematic showing putative transcription initiation complexes assembled on class I and class II RNA pol III promoters. B′′/? indicates the involvement of B′′ and unidentified factors.

In contrast, TFIIIC is not required for transcription of the human U6 gene (Reddy, 1988; Waldschmidt et al., 1991; Kuhlman et al., 1999). The PSE and the TATA box direct basal U6 transcription (Das et al., 1988; Kunkel and Pederson, 1988, 1989; Lobo and Hernandez, 1989) and the spacing between these elements is critical (Lobo et al., 1991; Goomer and Kunkel, 1992), suggesting that the corresponding binding factors may interact directly. SNAPc binds to the PSE and recruits TBP to the U6 TATA box in a cooperative manner in vitro (Mittal and Hernandez, 1997). When purified from cells, SNAPc contains sub-stoichiometric amounts of TBP (Henry et al., 1995, 1996; Yoon and Roeder, 1996), and the 43 and 45 kDa subunits bind TBP in vitro (Henry et al., 1995; Sadowski et al., 1996; Yoon and Roeder, 1996). We hypothesize that recruitment of an hBRF2-containing complex to the U6 promoter may occur via multiple interactions with SNAPc and is stabilized by the binding of TBP to the TATA box. hBRF2 may then serve as an adaptor between SNAPc and pol III.

What is the evidence for interaction between the BRF variants and pol III? First, yeast BRF was shown to contact the 34 and 17 kDa yeast pol III subunits via the repeat region (Werner et al., 1993; Khoo et al., 1994; Ruth et al., 1996; Kassavetis et al., 1998). Secondly, hBRF1 associates with the hRPC39 subunit of human pol III (Wang and Roeder, 1997), but the interaction domains have not been mapped. Finally, in transcriptions reconstituted with in vitro translated hBRFs, all the variants stimulate VA1 and EBER2 transcription above background levels (Figures 3 and 4), suggesting that they can all recruit pol III, perhaps via their repeat regions.

We suggest the division of pol III genes into two classes (Figure 8) based on their promoter structure and the nature of the factors they recruit. Genes that use TFIIIC and hBRF1 constitute class I, whereas genes that require SNAPc and hBRF2 comprise class II. The vault RNA and the tRNAser sec promoters contain upstream PSEs and TATA boxes as well as gene-internal sequences (Lee et al., 1989; Carbon and Krol, 1991; Meissner et al., 1994; Park et al., 1995), and cannot be assigned unambiguously to either class. Carbon and Krol (1991) have reported that the tRNAser sec gene requires both the upstream and gene-internal A box for transcription, whereas Park et al. (1995) mutated the A and B boxes without abolishing transcription. These results may reflect the availability of different factors in the systems used in the two laboratories, and such hybrid promoters could recruit either the hBRF1- or hBRF2-containing TFIIIB moieties, depending upon their availability in the cell.

Possible functions for hBRFs 3 and 4

As hBRF3 is identical to part of hBRF1, it may be able to interact with TFIIIC in addition to pol III. Because it is less active in transcription, it could serve a regulatory role at class I promoters by competing with hBRF1 for limiting factors. hBRF4 could function in concert with hBRF2 at the U6 promoter, a possibility that does not conflict with published data. It is also possible that hBRFs 3 and 4 are required at novel promoters.

Materials and methods

Isolation of hBRF cDNAs

A total of 500 000 plaques of a human breast cancer cDNA library (Foster et al., 1999) were screened with a probe corresponding to nucleotides 243–588 of hBRF (Mital et al., 1996). Eight plaques were isolated; the pBKCMV phagemids were excised and sequenced.

Constructs

hBRFs 2, 3 and 4 were excised from pBKCMV and cloned into pCITE 4 (Novagen). hBRF1 was PCR amplified, using 5′ BRF1-cgggatcccttatgacgggccgcgtgtg and 3′ BRF1-cgggatcctcagtagccgtcgtcctcatcgcc, and cloned into pCITE 4a.

The HA sequence was amplified with Pfu polymerase from the pCGN vector (Tanaka and Herr, 1990), using the oligonucleotides 5′ HA-tcccccggggacgccatggcttctagctatcc and 3′ HA-gctctagaaggtcctcccaggc, and ligated into pUC119 to generate pUC-HA. The hBRF1 insert was ligated into pUC-HA in-frame with the HA sequence. hBRFs 2 and 3 were PCR amplified using 2BRF 5′-gctctagaatgactgccctgaggct and the M13 forward primer, and ligated into pUC-HA. The hBRF4 insert was excised from pCITE and ligated into pUC-HA.

hBRFs 1-, 3- and 4-HA inserts were cloned into pLTRpoly (Makela et al., 1992). As the expression of hBRF2-HA was low in pLTRpoly, the hBRF2-HA fragment was placed under the control of the more powerful CMV promoter in pCMVβ (Clonetech) to generate hBRF2-HA/CMV.

Generation of hBRF truncations for transcription/translation

hBRFs 1, 2 and 3 were used in PCRs to generate a series of templates for in vitro transcription/translation as previously described for TBP (Lobo et al., 1992) using the following oligonucleotides: repeat 1, 5′-ctatttaggtgacactatagaaacagacaccatgatccaccacctggggaa and 3′-tcatgccaagagaagaaac; repeat 2, 5′-gtaatacgactcactatagggc and 3′-tcacttccgcagcgtgga; and hBRF 1/3 specific, 5′-ctatttaggtgacactatagaaacagacaccatgagcaggctcacggaatttg.

The unique regions of hBRFs 2 and 4 were cloned in-frame with an AUG codon and the S-tag of pCITE 4c. The pCITE clones were linearized and transcribed with T7 RNA polymerase. The PCR templates were transcribed with Sp6 polymerase and translated in either the rabbit reticulocyte or wheat germ systems (Promega) as per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Transfection and immunoprecipitation of tagged variants

Thirty micrograms of hBRFs 1, 3 or 4 in HA-LTRpoly or hBRF2-HA/CMV were transfected into BOSC 23 cells at 40% confluence as previously described (Pear et al., 1993). After 18 h, the medium was replaced, and the cells were harvested 40 h after transfection. Extracts were made from these cells (Andrews and Faller, 1991) and incubated for 90 min with 0.5 µl/10 cm plate of 12CA5 ascites at 4°C with nutation. Then 10 µl of a 1:1 slurry of protein A–Sepharose (Pierce) in buffer D (Dignam et al., 1983) were added and incubated for 30 min. The beads were washed five times with buffer D and eluted with 1 mg/ml HA peptide and 1.8 µg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA) in buffer D (Field et al., 1988) for 30 min at 25°C with mixing. The eluates were used in transcriptions.

Immunodepletions

HeLa nuclear extract (Dignam et al., 1983) diluted 1:1 with buffer D was incubated for 1 h at 4°C with either anti-R2P or 12CA5 antibodies bound to protein A–Sepharose beads or anti-TBP mAbs bound to protein G–beads, with mixing. The beads were pelleted and the supernatant was used in transcriptions.

Transcriptions

HeLa nuclear extracts were prepared and fractionated on P11 (Whatman) columns as previously described (Lobo et al., 1991). The concentrations of in vitro translated hBRF variant proteins were equalized by phosphoimager analysis. The proteins were diluted with unprogrammed lysate to 1 fmol/µl for hBRFs 2, 3 and 4, and 0.15 fmol/µl for hBRF1. An aliquot of either 2, 4 or 6 µl of each hBRF was used in combination with the C fraction and 0.1 fpu (footprinting units; Promega) of TBP. VA1 transcriptions (Figure 3A) were performed in 10 µl using 300 ng of template as previously described (Lobo et al., 1992) and 3 µl of the B and C fractions. EBER2 transcriptions were as for VA1 except that 200 ng of template, 3 mM MgCl2 and 4 µl of the B and C fractions were used (Figure 3A). In Figure 4A, 6 µl of anti-R2P antibody-depleted extract was complemented with the amounts of hBRFs indicated in a 20 µl volume and U6 transcripts were detected by RNase T1 protection as described (Lobo et al., 1992).

The reactions in Figure 6A contained 6 µl of anti-R2P antibody-depleted HeLa extract and 2, 6 or 10 µl of eluted complexes containing 0.18 fmol/µl of each hBRF in 20 µl reactions. 5S transcriptions were performed as for VA1 using 30 ng/µl template. 7SL transcriptions were as for VA1 except that 200 ng of template pT3/T7 7SL and 1 mM MgCl2 were used. In Figure 6B, VA1 transcriptions were as in Figure 6A except that 0.1 fpu of TBP (Promega) were added as indicated. U6 transcriptions were performed using 6 µl of depleted extract, 2 µg of pU6/Hae/RA.2 template, 4, 8 or 12 µl of eluted complex and 0.1 fpu of TBP. Transcriptions in Figure 7 were done in 20 µl volumes containing 6 and 10 µl of depleted extract for VA1 and U6, respectively. TBP was used at 0.66 and 0.2 fpu together with 2 or 5 µl of hBRF1.

Immunoprecipitations

In Figure 1C, 30 µg of each affinity-purified antibody were used with the same amount of each in vitro translated hBRF (five times that shown in the corresponding input lane) in buffer D containing 0.1% Tween-20. In Figure 2A, twice the amount of each hBRF shown in the input lanes ± 2 µl of in vitro translated TBP were incubated in buffer D + 300 mM KCl, or in RIPA buffer [10 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.5% Tween-20, 0.5% NP-40 and 0.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF)], containing100 µg/ml ethidium bromide at 30°C for 15 min, and then on ice for 10 min. A 2 µl aliquot of SL30a ascites (Ruppert et al., 1996) was added, and the volume adjusted to 1 ml with the same buffers. After 1 h at 4°C with nutation, 25 µl of a 1:1 protein G–Sepharose slurry (Pharmacia) were added, and the samples were incubated for 30 min at 4°C. The beads were washed five times with 1 ml of the reaction buffers, Laemmli buffer was added and the samples were electrophoresed. In Figure 2B, buffer D containing 40 µg/ml ethidium bromide was used and the input lanes show one-sixth the amount of protein present in the immunoprecipitation reactions. In Figures 1 and 2, proteins were detected by autoradiography.

For immunoprecipitations using cross-linked proteins, extracts were made from transfected cells as before, incubated for 2 h on ice with 1.5 mM DSP (Pierce), treated for 20 min at 4°C with 10 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, and immunoprecipitated with 12CA5 mAbs in RIPA buffer.

Generation of anti-peptide antibodies and immunoblotting

R2P and hBRF2sp peptides (Figure 1B) were synthesized at the UAB protein core facility, conjugated to keyhole limpet hemocyanin (Pierce) and used to immunize rabbits at Rockland Inc., Gilbertsville, PA. Antibodies were affinity purified using the same peptides conjugated to Sulfolink columns (Pierce). Immunoblot detection was as described (Lobo et al., 1992).

Accession numbers

The sequences reported here have been deposited in the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank (Accession Nos AJ297406, AJ297407 and AJ297408).

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank R.Mital, N.Hernandez, R.Roeder, E.Ullu, M.Matthews, R.Little and G.Howe for providing constructs, K.Pandya, H.Grennett, M.Olman, J.Kudlow and E.Benveniste for cell lines, K.Pandya for technical advice and J.Harrison for secretarial support. This work was supported by the Marie and Emmett Carmichael Fund for students in the Biosciences to V.M. and by NIH grants RO1GM51908 to S.M.L.-R. and CA65686 to J.M.R.

References

- Andrews N.C. and Faller,D.V. (1991) A rapid micropreparation technique for extraction of DNA-binding proteins from limiting numbers of mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res., 19, 2499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brow D.A. and Guthrie,C. (1990) Transcription of a yeast U6 snRNA gene requires a polymerase III promoter element in a novel position. Genes Dev., 4, 1345–1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buratowski S. and Zhou,H. (1992) A suppressor of TBP mutations encodes an RNA polymerase III transcription factor with homology to TFIIB. Cell, 71, 221–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbon P. and Krol,A. (1991) Transcription of the Xenopus laevis selenocysteine tRNA(Ser)Sec gene: a system that combines an internal B box and upstream elements also found in U6 snRNA genes. EMBO J., 10, 599–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colbert T. and Hahn,S. (1992) A yeast TFIIB-related factor involved in RNA polymerase III transcription. Genes Dev., 6, 1940–1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das G., Henning,D., Wright,D. and Reddy,R. (1988) Upstream regulatory elements are necessary and sufficient for transcription of a U6 RNA gene by RNA polymerase III. EMBO J., 7, 503–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dignam J.D., Lebovitz,R.M. and Roeder,R.G. (1983) Accurate transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II in a soluble extract from isolated mammalian nuclei. Nucleic Acids Res., 11, 1475–1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eschenlauer J.B., Kaiser,M.W., Gerlach,V.L. and Brow,D.A. (1993) Architecture of a yeast U6 RNA gene promoter. Mol. Cell. Biol., 13, 3015–3026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field J., Nikawa,J., Broek,D., MacDonald,B., Rodgers,L., Wilson,I.A., Lerner,R.A. and Wigler,M. (1988) Purification of a RAS-responsive adenylyl cyclase complex from Saccharomyces cerevisiae by use of an epitope addition method. Mol. Cell. Biol., 8, 2159–2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster K.W. et al. (1999) Oncogene expression cloning by retroviral transduction of adenovirus E1A-immortalized rat kidney RK3E cells: transformation of a host with epithelial features by c-MYC and the zinc finger protein GKLF. Cell Growth Differ., 10, 423–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlach V.L., Whitehall,S.K., Geiduschek,E.P. and Brow,D.A. (1995) TFIIIB placement on a yeast U6 RNA gene in vivo is directed primarily by TFIIIC rather than by sequence-specific DNA contacts. Mol. Cell. Biol., 15, 1455–1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goomer R.S. and Kunkel,G.R. (1992) The transcriptional start site for a human U6 small nuclear RNA gene is dictated by a compound promoter element consisting of the PSE and the TATA box. Nucleic Acids Res., 20, 4903–4912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry R.W., Sadowski,C.L., Kobayashi,R. and Hernandez,N. (1995) A TBP–TAF complex required for transcription of human snRNA genes by RNA polymerase II and III. Nature, 374, 653–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry R.W., Ma,B., Sadowski,C.L., Kobayashi,R. and Hernandez,N. (1996) Cloning and characterization of SNAP50, a subunit of the snRNA-activating protein complex SNAPc. EMBO J., 15, 7129–7136. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh Y.J., Kundu,T.K., Wang,Z., Kovelman,R. and Roeder,R.G. (1999a) The TFIIIC90 subunit of TFIIIC interacts with multiple components of the RNA polymerase III machinery and contains a histone-specific acetyltransferase activity. Mol. Cell. Biol., 19, 7697–7704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh Y.J., Wang,Z., Kovelman,R. and Roeder,R.G. (1999b) Cloning and characterization of two evolutionarily conserved subunits (TFIIIC102 and TFIIIC63) of human TFIIIC and their involvement in functional interactions with TFIIIB and RNA polymerase III. Mol. Cell. Biol., 19, 4944–4952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huet J. and Sentenac,A. (1992) The TATA-binding protein participates in TFIIIB assembly on tRNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res., 20, 6451–6454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huet J., Conesa,C., Manaud,N., Chaussivert,N. and Sentenac,A. (1994) Interactions between yeast TFIIIB components. Nucleic Acids Res., 22, 2282–2288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joazeiro C.A., Kassavetis,G.A. and Geiduschek,E.P. (1994) Identical components of yeast transcription factor IIIB are required and sufficient for transcription of TATA box-containing and TATA-less genes. Mol. Cell. Biol., 14, 2798–2808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassavetis G.A., Braun,B.R., Nguyen,L.H. and Geiduschek,E.P. (1990) S.cerevisiae TFIIIB is the transcription initiation factor proper of RNA polymerase III, while TFIIIA and TFIIIC are assembly factors. Cell, 60, 235–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassavetis G.A., Joazeiro,C.A., Pisano,M., Geiduschek,E.P., Colbert,T., Hahn,S. and Blanco,J.A. (1992) The role of the TATA-binding protein in the assembly and function of the multisubunit yeast RNA polymerase III transcription factor, TFIIIB. Cell, 71, 1055–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassavetis G.A., Nguyen,S.T., Kobayashi,R., Kumar,A., Geiduschek,E.P. and Pisano,M. (1995) Cloning, expression and function of TFC5, the gene encoding the B′′ component of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae RNA polymerase III transcription factor TFIIIB. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 92, 9786–9790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassavetis G.A., Kumar,A., Ramirez,E. and Geiduschek,E.P. (1998) Functional and structural organization of Brf, the TFIIB-related component of the RNA polymerase III transcription initiation complex. Mol. Cell. Biol., 18, 5587–5599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoo B., Brophy,B. and Jackson,S.P. (1994) Conserved functional domains of the RNA polymerase III general transcription factor BRF. Genes Dev., 8, 2879–2890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlman T.C., Cho,H., Reinberg,D. and Hernandez,N. (1999) The general transcription factors IIA, IIB, IIF and IIE are required for RNA polymerase II transcription from the human U1 small nuclear RNA promoter. Mol. Cell. Biol., 19, 2130–2141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A., Grove,A., Kassavetis,G.A. and Geiduschek,E.P. (1998) Transcription factor IIIB: the architecture of its DNA complex and its roles in initiation of transcription by RNA polymerase III. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol., 63, 121–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunkel G.R. and Pederson,T. (1988) Upstream elements required for efficient transcription of a human U6 RNA gene resemble those of U1 and U2 genes even though a different polymerase is used. Genes Dev., 2, 196–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunkel G.R. and Pederson,T. (1989) Transcription of a human U6 small nuclear RNA gene in vivo withstands deletion of intragenic sequences but not of an upstream TATA box. Nucleic Acids Res., 17, 7371–7379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai J.S. and Herr,W. (1992) Ethidium bromide provides a simple tool for identifying genuine DNA-independent protein associations. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 89, 6958–6962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B.J., Kang,S.G. and Hatfield,D. (1989) Transcription of Xenopus selenocysteine tRNA Ser gene is directed by multiple 5′-extragenic regulatory elements. J. Biol. Chem., 264, 9696–9702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobo S.M. and Hernandez,N. (1989) A 7 bp mutation converts a human RNA polymerase II snRNA promoter into an RNA polymerase III promoter. Cell, 58, 55–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobo S.M., Lister,J., Sullivan,M.L. and Hernandez,N. (1991) The cloned RNA polymerase II transcription factor IID selects RNA polymerase III to transcribe the human U6 gene in vitro. Genes Dev., 5, 1477–1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobo S.M., Tanaka,M., Sullivan,M.L. and Hernandez,N. (1992) A TBP complex essential for transcription from TATA-less but not TATA-containing RNA polymerase III promoters is part of the TFIIIB fraction. Cell, 71, 1029–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-De-Leon A., Librizzi,M., Puglia,K. and Willis,I.M. (1992) PCF4 encodes an RNA polymerase III transcription factor with homology to TFIIB. Cell, 71, 211–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makela T.P., Partanen,J., Schwab,M. and Alitalo,K. (1992) Plasmid pLTRpoly: a versatile high-efficiency mammalian expression vector. Gene, 118, 293–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner W., Wanandi,I., Carbon,P., Krol,A. and Seifart,K.H. (1994) Transcription factors required for the expression of Xenopus laevis selenocysteine tRNA in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res., 22, 553–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mital R., Kobayashi,R. and Hernandez,N. (1996) RNA polymerase III transcription from the human U6 and adenovirus type 2 VAI promoters has different requirements for human BRF, a subunit of human TFIIIB. Mol. Cell. Biol., 16, 7031–7042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal V. and Hernandez,N. (1997) Role for the amino-terminal region of human TBP in U6 snRNA transcription. Science, 275, 1136–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller J. and Benecke,B.J. (1999) Analysis of transcription factors binding to the human 7SL RNA gene promoter. Biochem. Cell Biol., 77, 431–438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J.M., Choi,I.S., Kang,S.G., Lee,J.Y., Hatfield,D.L. and Lee,B.J. (1995) Upstream promoter elements are sufficient for selenocysteine tRNA[Ser]Sec gene transcription and to determine the transcription start point. Gene, 162, 13–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pear W.S., Nolan,G.P., Scott,M.L. and Baltimore,D. (1993) Production of high-titer helper-free retroviruses by transient transfection. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 90, 8392–8396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy R. (1988) Transcription of a U6 small nuclear RNA gene in vitro. Transcription of a mouse U6 small nuclear RNA gene in vitro by RNA polymerase III is dependent on transcription factor(s) different from transcription factors IIIA, IIIB and IIIC. J. Biol. Chem., 263, 15980–15984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts S., Miller,S.J., Lane,W.S., Lee,S. and Hahn,S. (1996) Cloning and functional characterization of the gene encoding the TFIIIB90 subunit of RNA polymerase III transcription factor TFIIIB. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 14903–14909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruppert S.M., McCulloch,V., Meyer,M., Bautista,C., Falkowski,M., Stunnenberg,H.G. and Hernandez,N. (1996) Monoclonal antibodies directed against the amino-terminal domain of human TBP cross-react with TBP from other species. Hybridoma, 15, 55–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruth J., Conesa,C., Dieci,G., Lefebvre,O., Dusterhoft,A., Ottonello,S. and Sentenac,A. (1996) A suppressor of mutations in the class III transcription system encodes a component of yeast TFIIIB. EMBO J., 15, 1941–1949. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadowski C.L., Henry,R.W., Lobo,S.M. and Hernandez,N. (1993) Targeting TBP to a non-TATA box cis-regulatory element: a TBP-containing complex activates transcription from snRNA promoters through the PSE. Genes Dev., 7, 1535–1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadowski C.L., Henry,R.W., Kobayashi,R. and Hernandez,N. (1996) The SNAP45 subunit of the small nuclear RNA (snRNA) activating protein complex is required for RNA polymerase II and III snRNA gene transcription and interacts with the TATA box binding protein. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 4289–4293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka M. and Herr,W. (1990) Differential transcriptional activation by Oct-1 and Oct-2: interdependent activation domains induce Oct-2 phosphorylation. Cell, 60, 375–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teichmann M. and Seifart,K.H. (1995) Physical separation of two different forms of human TFIIIB active in the transcription of the U6 or the VA1 gene in vitro. EMBO J., 14, 5974–5983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teichmann M., Wang,Z., Martinez,E., Tjernberg,A., Zhang,D., Vollmer,F., Chait,B.T. and Roeder,R.G. (1999) Human TATA-binding protein-related factor-2 (hTRF2) stably associates with hTFIIA in HeLa cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 13720–13725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldschmidt R., Wanandi,I. and Seifart,K.H. (1991) Identification of transcription factors required for the expression of mammalian U6 genes in vitro. EMBO J., 10, 2595–2603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z. and Roeder,R.G. (1995) Structure and function of a human transcription factor TFIIIB subunit that is evolutionarily conserved and contains both TFIIB- and high-mobility-group protein 2-related domains. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 92, 7026–7030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z. and Roeder,R.G. (1997) Three human RNA polymerase III-specific subunits form a subcomplex with a selective function in specific transcription initiation. Genes Dev., 11, 1315–1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner M., Chaussivert,N., Willis,I.M. and Sentenac,A. (1993) Interaction between a complex of RNA polymerase III subunits and the 70-kDa component of transcription factor IIIB. J. Biol. Chem., 268, 20721–20724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehall S.K., Kassavetis,G.A. and Geiduschek,E.P. (1995) The symmetry of the yeast U6 RNA gene’s TATA box and the orientation of the TATA-binding protein in yeast TFIIIB. Genes Dev., 9, 2974–2985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis I.M. (1993) RNA polymerase III. Genes, factors and transcriptional specificity. Eur. J. Biochem., 212, 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon J.B. and Roeder,R.G. (1996) Cloning of two proximal sequence element-binding transcription factor subunits (γ and δ) that are required for transcription of small nuclear RNA genes by RNA polymerases II and III and interact with the TATA-binding protein. Mol. Cell. Biol., 16, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon J.B., Murphy,S., Bai,L., Wang,Z. and Roeder,R.G. (1995) Proximal sequence element-binding transcription factor (PTF) is a multisubunit complex required for transcription of both RNA polymerase II- and RNA polymerase III-dependent small nuclear RNA genes. Mol. Cell. Biol., 15, 2019–2027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]