Abstract

Sodium channels play an essential role in generating the action potential in eukaryotic cells, and their transcripts, especially those in insects, undergo extensive A-to-I RNA editing. The functional consequences of RNA editing of sodium channel transcripts, however, have yet to be determined. We characterized 20 splice variants of the German cockroach sodium channel gene BgNav. Functional analysis revealed that these variants exhibited a broad range of voltage-dependent activation and inactivation. Further analysis of two variants, BgNav1-1 and BgNav1-2, which activate at more depolarizing membrane potentials than other variants, showed that RNA editing events were responsible for variant-specific gating properties. Two U-to-C editing sites identified in BgNav1-1 resulted in a Leu to Pro change in segment 1 of domain III (IIIS1) and a Val to Ala change in IVS4. The Leu to Pro change shifted both the voltage dependence of activation and steady-state inactivation in the depolarizing direction. Two A-to-I editing events in BgNav1-2 resulted in a Lys to Arg change in IS2 and an Ile to Met change in IVS3. The Lys to Arg change shifted the voltage dependence of activation in the depolarizing direction. Moreover, these RNA editing events occurred in a tissue-specific and development-specific manner. Our findings provide direct evidence that RNA editing is an important mechanism generating tissue-/cell type-specific functional variants of sodium channels.

The voltage-gated sodium channel is responsible for the rising phase of the action potential in the membranes of neurons and other excitable cells (1). At least nine different mammalian sodium channel α-subunits (Nav1.1 to Nav1.9) have been identified (2, 3). These sodium channel isoforms exhibit distinct expression patterns in the nervous system and skeletal and cardiac muscle (4). Differences in electrophysiological properties have been observed among different mammalian sodium channel α-subunit isoforms, which likely contribute to their specialized functional roles in various tissues/cell types (4–6). In contrast to multiple sodium channel genes in mammals, there appears to be only one functional sodium channel gene in insects. For example, para is the only gene that encodes a functional sodium channel in Drosophila melanogaster (7–9). Orthologs of the para gene, house fly Vssc1 and cockroach BgNav (formerly paraCSMA), have been cloned and characterized in Xenopus oocytes (10–12).

Alternative splicing and developmental regulation of alternative splicing have been documented in both mammalian and insect sodium channel genes (12–21). Conservation of splicing sites among mammalian and insect sodium channel strongly suggests the biological importance of alternative splicing. Indeed, significant modifications of functional properties of sodium channels by alternative splicing have been demonstrated (12, 19).

RNA editing is another important post-transcriptional modification that could significantly change protein functions by introducing site-specific alterations in gene transcripts, including the conversion of one base to another, or the insertion and deletion of nucleotides (22–24). Originally discovered in yeast tRNAs, A-to-I RNA editing has since been found in almost a dozen transcripts encoding ion channels and neurotransmitter receptors in the nervous system and also in multiple viral RNA transcripts (22). The best studied transcripts are subunits of mammalian glutamate-gated ion channels, a mammalian serotonin receptor (25, 26), and squid voltage-gated potassium channels (27, 28). In these cases, edited channels or receptors exhibit distinct functional and/or pharmacological properties. Ten A-to-I editing sites are found in the para transcript in D. melanogaster (29). However, the impact of RNA editing on sodium channel function remains elusive.

Here, we showed that tissue-specific RNA editing in the cockroach sodium channel mRNA modulates sodium channel gating properties, providing the first direct evidence for the involvement of RNA editing in post-transcriptional modification of sodium channels.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cockroach Tissues

Ovary, gut, and leg and nerve cord tissues were isolated from insecticide-susceptible German cockroaches (CSMA). Nerve cords include thoracic ganglia, abdominal ganglia, and the connectives. For the analysis of developmental profile of BgNav transcripts, embryonic and immature stages were divided into the following five: embryonic stages I, II, and III, and nymph stages I and II. Embryos in embryonic stage I had uniform yolk and no obvious segmentation; stage II embryos had segmentation in abdomen and legs, but no eye coloration; and stage III embryos had very distinct eye color and well formed appendages and antennae. These three embryonic stages correspond to stages 1–5, stages 6–12, and stages 16–18, respectively, defined by Bell (30). The first and second nymphal instars were designated as nymph I and the last instar (6th) as nymph II.

Molecular Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from cockroach tissues, including head/thorax, leg, ovary, gut, and nerve cord, using TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen). Methods for first-strand cDNA synthesis, reverse transcription-PCR, cloning, and PCR amplification of genomic DNA were identical to those described by Tan et al. (12). Primers used for the PCR analysis of optional exons and RNA editing sites are listed in Table I. Total RNA from heads and thoraces of four cockroaches (about 90 mg of tissue) was used to isolate partial cDNA clones for identification of RNA editing sites. The nucleotide sequences were determined at the Genomic Technology Service Facility at Michigan State University.

TABLE I. Oligonucleotide primers used for this study.

| Primera | Nucleotide sequence (5′–3′) | Amino acid positionb | Exon or editing site |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | acgactcgtcctcaatctcag (→) c | 3–9 | J |

| 2 | aaaggccttgcattcggacag (←) | 74–80 | J |

| 3 | ctaccacaaccagagaac (→) | 97–102 | K |

| 4 | gcatgccagttctcatcattca (←) | 302–309 | K |

| 5 | gccatgtcctacgatgagttg (→) | 417–423 | I |

| 6 | cactagattttcctggtatg (←) | I | |

| 7 | gcaagtttgagtctacc (→) | 535–540 | A |

| 8 | gctccatcatcactgtctgctgac (←) | 674–681 | A |

| 9 | gggtgcaggcaacaaatctca (→) | 640–646 | B |

| 10 | gggaaataatagatggagac (←) | 728–734 | B |

| 11 | ctatgtgggattgtatgcttgttg (→) | 968–975 | E |

| 12 | ccaactggaggagggtc (←) | E | |

| 13 | acacggaccttgacctcac (→) | 1068–1074 | F |

| 14 | cttttcctccccatccatagtc (←) | 1180–1186 | F |

| 15 | aatcaagcgaagatgtgagattgcgccac | 3′-UTRd | |

| 16 | tgaggacgtcatgatgtcag (→) | 1221–1228 | P/L |

| 17 | tgacagtgaagatacgatcc (←) | 1308–1313 | P/L |

| 18 | atcgtcatcttcagttccg (→) | 1628–1633 | V/A; L/M |

| 19 | tttcaccagacgcaggactcg (←) | 1692–1698 | V/A; L/M |

| 20 | ttcaacccgattcgacgggttgc (→) | 127–134 | K/R |

| 21 | aaggtacgtgaatggctgaag (←) | 192–198 | K/R |

Primers 1–14 were used to amplify alternative exons. Most of them correspond to sequences flanking these optional exons, except primers 6 and 12 designed based on alternative exon-specific sequences. Primer 15 was used in reverse transcription. Primers 16–21 were used in the analysis of RNA editing sites.

The amino acid positions refer to those in the published sequence of BgNav(GenBank accession number: U73583).

The sense and antisense primers are marked with → and ←, respectively.

UTR, untranslated region.

Site-directed mutagenesis was performed using the Altered Sites II in vitro Mutagenesis System (Promega, Madison, WI). BgNav1-1 has four amino acid changes: R502G, L1285P, V1685A, and I1806L (e.g. for R502G, Arg in the available sequence (GenBank accession number U73583) and Gly in BgNav1-1). BgNav1-2 also has four amino acid changes: R45G, K184R, I1663M, and N1787D. To determine which amino acid residue(s) contributed to the unique gating properties of BgNav1-1 and BgNav1-2, we replaced these residues individually with the corresponding residues in the published BgNav sequence. Briefly, a 0.9-kb KpnI/SphI fragment containing Gly502 in BgNav1-1, Gly45 and Arg184 in BgNav1-2, a 1.4-kb Eco47III fragment containing Pro1285 and Ala1685 in BgNav1-1 and Met1663 in BgNav1-2, and a 1.7-kb HindIII fragment containing Leu1806 in BgNav1-1 and Asp1787 in BgNav1-2 were used for site-directed mutagenesis. We also generated BgNav1-1A from BgNav1-1 by changing all four amino acid resides to the corresponding ones in the published BgNav sequence.

Expression of BgNav Sodium Channels in Xenopus Oocytes

The procedures for oocyte preparation and cRNA injection are identical to those described by Tan et al. (12). For robust expression of the cockroach BgNav sodium channel, BgNav cRNA (0.2–2 ng) was coinjected into oocytes with D. melanogaster tipE cRNA (0.2–2 ng), which is known to enhance the expression of insect sodium channels in oocytes (8, 9).

Electrophysiological Recording and Analysis

Methods for electrophysiological recording and data analysis are similar to those described previously (12). The voltage dependence of sodium channel conductance (G) was calculated by measuring the peak current at test potentials ranging from −80 mV to +65 mV in 5-mV increments and divided by (V − Vrev), where V is the test potential and Vrev is the reversal potential for sodium ion. Peak conductance values were normalized to the maximal peak conductance (Gmax) and fitted with a two-state Boltzmann equation of the form

| (Eq. 1) |

in which V is the potential of the voltage pulse, V½ is the half-maximal voltage for activation, and k is the slope factor.

The voltage dependence of sodium channel inactivation was determined using 200-ms inactivating pre-pulses from a holding potential of −120 mV to 0 mV in 5-mV increments, followed by test pulses to −10 mV for 20 ms. The peak current amplitude during the test depolarization was normalized to the maximum current amplitude and plotted as a function of the pre-pulse potential. The data were fitted with a two-state Boltzmann equation of the form

| (Eq. 2) |

in which Imax is the maximal current evoked, V is the potential of the voltage pulse, V½ is the half-maximal voltage for inactivation, and k is the slope factor.

To determine the recovery from fast inactivation, sodium channels were inactivated by a 200-ms depolarizing pulse to −10 mV and then repolarized to −120 mV for an interval of variable durations followed by a 20-ms test pulse to −10 mV. The peak current during the test pulse was divided by the peak current during the inactivating pulse and plotted as a function of duration time between the two pulses. To determine the time constant for recovery, the curve was fitted using double exponential function

| (Eq. 3) |

where A1 and A2 are the relative proportions of current recovering with time constants τ1 and τ2, and t is recovery interval.

RESULTS

Identification of 20 Splice Types of the Cockroach Sodium Channel Gene

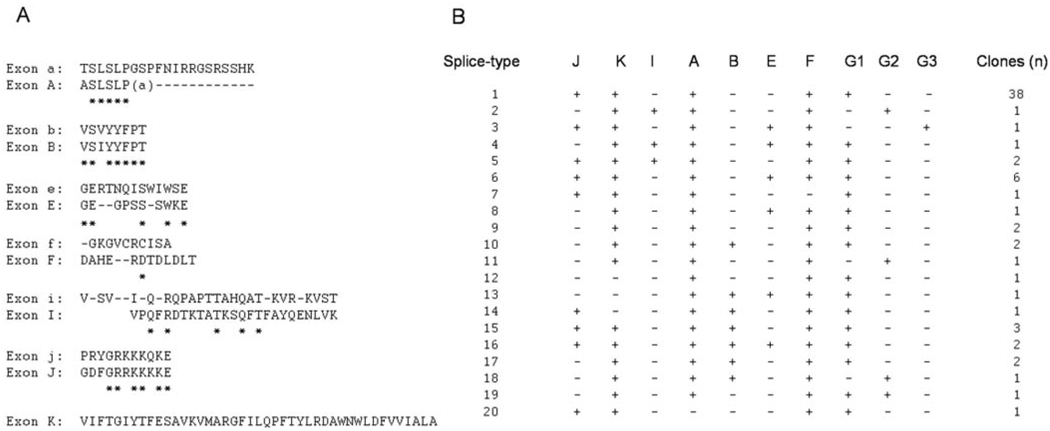

In a previous study, we reported the isolation and functional characterization of three cockroach BgNav variants, KD1, KD2, and KD3 (12). These variants exhibit distinct gating and pharmacological properties (12). To elucidate the full complement of the BgNav sodium channel diversity, we isolated 66 more full-length cDNA clones using the same cloning strategy in this study. Extensive restriction enzyme digestion of these clones revealed sequence polymorphism in several regions. Subsequent PCR sequencing analysis of these regions using PCR primers in Table I confirmed deletions or insertions of short segments, ranging from 19 to 129 bp in size. Because the locations and sequences of most insertions or deletions are homologous to the optional exons identified in the Drosophila para transcripts (16–18), these cockroach alternative exons are designated with the same letters, except in capitals (Fig. 1A). Most optional exons are located in the first or second intracellular linkers connecting domains I and II or domains II and III. High degrees of sequence homology are evident between Drosophila optional exons a and b and the corresponding cockroach exons A and B. Because exon A contains 19 nucleotides, exclusion of exon A results in frameshift, introducing a premature stop codon downstream in the first linker connecting domains I and II. Optional exon K is found only in cockroach and encodes 43 amino acid residues in IS2-3.1

FIG. 1. Identification of 20 splice types of BgNav.

A, alignments of the deduced amino acid sequences encoded by alternative exons between para (top) and BgNav (bottom). The exon sequence alignment was performed using the DNAStar program. The asterisks underneath the sequences represent the sequence identity, and gaps introduced to obtain optimal alignments are indicated as dashes. Exon A contains 19 nucleotides (ggcaagtttgagtctacca). The last nucleotide “a” is presented in parentheses. B, usage of alternative exons in 69 full-length cDNA clones. The + and − symbols represent the presence and absence of an optional exon, respectively. Exons G1/G2/G3 are mutually exclusive, encoding IIIS3–4 (12). The variants are named according to the splice types. For example, the variants in splice type 1 are designated as BgNav1, and variants belonging to this splice type are named BgNav1-1 to BgNav1-38.

Examination of the presence or absence of each alternative exon in the 69 full-length clones, including KD1, KD2, and KD3, revealed 20 splice types (Fig. 1B), which are far less than the possible random combinations of the identified alternative exons. This observation strongly suggests biased inclusion and exclusion of certain exons in sodium channels. In fact, 38 clones, including KD1, had the same splice type (Fig. 1B), which represents the most prevalent sodium channel splice type in the German cockroach. Hereinafter, we refer to the variants according to their splice types. For example, variants that belong to splice type 1 are named BgNav1-1, BgNav1-2, and so on. Therefore, KD1, KD2, and KD3 are renamed BgNav1-1, BgNav2, and BgNav3, respectively.

Sodium Channel Variants Exhibit Different Gating Properties

Variants BgNav1-1, BgNav2, and BgNav3 were characterized previously in oocytes, revealing distinct gating and pharmacological properties (12). In this study, we performed functional analysis of eighteen new variants including two type 1 variants (BgNav1-2 and BgNav1-3) and 16 variants each representing a unique splice type (BgNav5 to BgNav20). The electrophysiological properties of these variants were examined using two-electrode voltage clamp. 9 of 18 variants produced sufficient sodium currents for functional analysis (Table II), whereas the remaining 9 variants produced little or no sodium currents, possibly representing nonfunctional channels or channels that require additional cellular signals for robust expression. Sodium currents were completely blocked by tetrodotoxin at 10 nm for all functional splice variants except for BgNav11. BgNav11 exhibited a low level of resistance to TTX. At 10 nm, 60% of BgNav11 peak current was inhibited, and a concentration of 50 nm was required to block it completely.

TABLE II. Functional properties of nine splice variants.

The voltage dependence of activation and inactivation was fitted with two-state Boltzmann equations, as described under “Experimental Procedures,” to determine V1/2, the voltage for half-maximal conductance or inactivation, and k, the slope factor for conductance or inactivation. Each value represents the mean ± S.D. for at least five oocytes.

| Activation |

Fast inactivation |

Recovery from inactivation |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V1/2 | k | V1/2 | k | τ1 | A1 | τ2 | A2 | |

| mV | mV | ms | % | ms | % | |||

| BgNav1-2 | −24.9 ± 1.4 | 4.9 ± 0.4 | −49.0 ± 0.7 | 4.8 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 86 ± 2 | 49 ± 9 | 14 ± 2 |

| BgNav5 | −25.5 ± 0.9 | 4.8 ± 0.4 | −45.5 ± 0.9 | 4.3 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 90 ± 2 | 28 ± 7 | 10 ± 2 |

| BgNav6 | −27.4 ± 6.2 | 4.0 ± 1.0 | −38.7 ± 1.8 | 4.2 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 93 ± 3 | 38 ± 4 | 7 ± 3 |

| BgNav7 | −29.2 ± 3.8 | 4.1 ± 0.5 | −44.9 ± 1.8 | 4.4 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 90 ± 4 | 18 ± 5 | 10 ± 4 |

| BgNav8 | −30.1 ± 4.4 | 5.4 ± 0.5 | −54.4 ± 1.4 | 5.6 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.0 | 89 ± 1 | 35 ± 6 | 11 ± 1 |

| BgNav9 | −30.6 ± 3.9 | 4.2 ± 0.7 | −49.3 ± 0.6 | 4.1 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 90 ± 2 | 24 ± 8 | 10 ± 2 |

| BgNav1-3 | −34.1 ± 4.4 | 4.3 ± 0.4 | −48.4 ± 0.8 | 4.6 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 89 ± 3 | 26 ± 3 | 11 ± 3 |

| BgNav10 | −36.7 ± 3.4 | 1.9 ± 0.6 | −37.2 ± 0.9 | 3.7 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.0 | 95 ± 1 | 24 ± 5 | 5 ± 1 |

| BgNav11 | −43.9 ± 3.0 | 4.7 ± 0.8 | −54.0 ± 1.5 | 4.5 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 94 ± 1 | 70 ± 12 | 6 ± 1 |

All 9 functional variants activated rapidly in response to depolarization and then inactivated rapidly and nearly completely, similar to that reported for BgNav1-1 (12). To determine whether different variants exhibit different gating properties, the voltage dependence of activation, voltage dependence of steady-state inactivation, and recovery from fast inactivation were determined using the protocols described under “Experimental Procedures.” The voltage for half-maximal activation ranged from −25 to −44 mV (Table II). BgNav11 activated at a more hyperpolarizing membrane potential, and BgNav1-1 and BgNav1-2 required larger membrane depolarization for activation. The remaining variants exhibited properties intermediate between these two extremes. A broad voltage range for half-maximal inactivation, from −37 to −54 mV, was evident among the variants (Table II). BgNav8 and BgNav11 inactivated at more negative membrane potentials than the others. There was no significant difference in kinetics of recovery from inactivation among the variants (Table II).

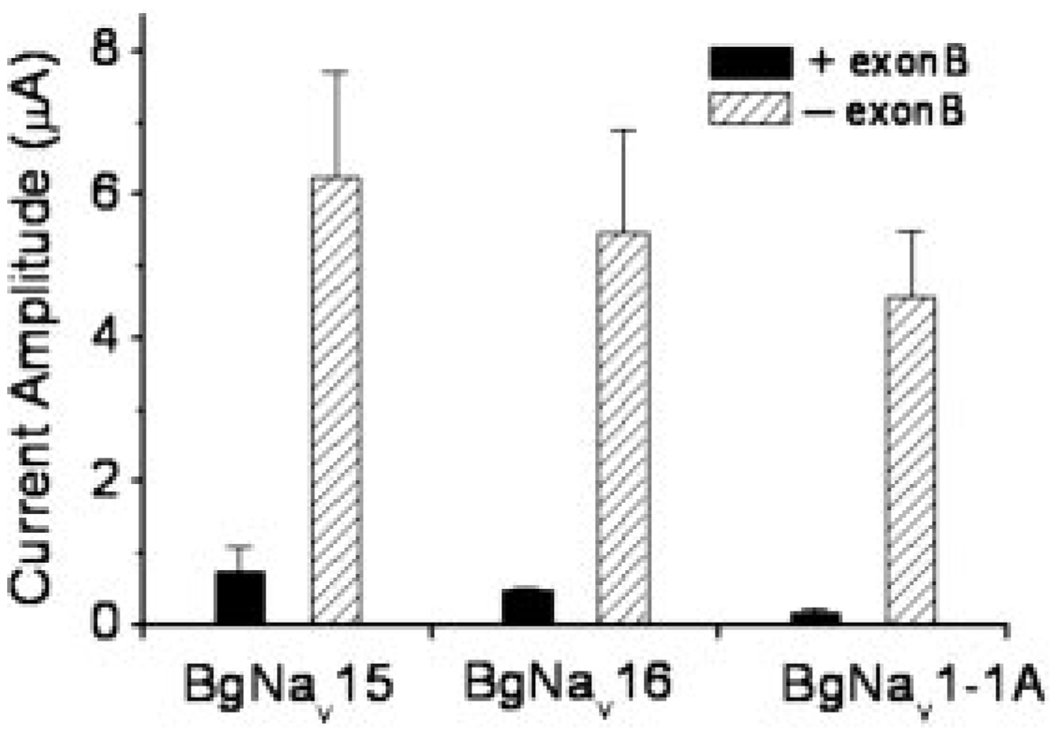

Optional Exon B Modulates Sodium Current Expression

9 of the 18 variants could not be functionally analyzed because they did not conduct sufficient sodium currents. 5 variants did not generate any sodium current in oocytes. Among them, BgNav20 contained a premature stop codon caused by the exclusion of optional exon A. BgNav12, BgNav13, and BgNav14 lacked exon K (encoding IS2-3). BgNav19 contained two mutually exclusive exons, G1 and G2. It is likely that introduction of a premature stop codon in BgNav20, missing part of transmembrane segment IS2-3 (exon K) in BgNav12, BgNav13, and BgNav14, or having an extra transmembrane segment (exons G1 and G2) in IIIS3-4 in BgNav19 are responsible for nonfunctional channels in oocytes. The remaining four variants, BgNav15, BgNav16, BgNav17, and BgNav18, however, did not have any stop codon or missing transmembrane segments, but the peak current amplitude for these variants was less than 0.5 µA 1 week after injection of 2 ng of cRNA/oocyte, which was not sufficient for functional analysis. Comparison of alternative exon usage revealed that all four variants contained exon B, which encodes an 8-amino acid sequence in the first linker connecting domains I and II (Fig. 1A).

To determine whether inclusion of exon B is responsible for poor expression of sodium current in these variants, we deleted exon B from variants BgNav15 and BgNav16. The resultant recombinant construct produced robust expression of sodium currents (Fig. 2). Furthermore, when we inserted exon B into functional BgNav1-1A, which is identical in sequence to published BgNav (accession number U73583), the amplitude of peak current of the recombinant channels was greatly reduced (Fig. 2). These complementary results demonstrated that exon B modulates sodium channel expression and/or function. However, one exon B-containing variant, BgNav10, produced sufficient sodium currents (greater than 0.5 µA in amplitude) for functional analysis. We hypothesize that an unidentified sequence(s) in BgNav10 counteracted the negative regulation of sodium current expression by exon B.

FIG. 2. Optional exon B modulates sodium current expression.

Both BgNav15 and BgNav16 contain exon B. Deletion of exon B in BgNav15 and BgNav16 increases the amplitude of peak current. BgNav1-1A lacks exon B. Addition of exon B into BgNav1-1A reduces the amplitude of peak current. The peak current was measured by a 20-ms depolarization to −10 mV from the −120-mV holding potential at day 4 after injection of 0.2 ng of cRNA for BgNav1-1A and its recombinant, and 2 ng of cRNA for BgNav15, BgNav16, and their recombinants.

L1285P in BgNav1-1 Alters the Voltage Dependence of Activation and Steady-state Inactivation

In addition to different alternative exon usage, sequence analysis of the 9 functional variants revealed on average five scattered amino acid changes compared with the published BgNav sequence (31; GenBank accession number U73583) (Table III). We next examined a possible contribution of these amino acid differences to the observed differences in gating properties among variants.

TABLE III. Scattered amino acid changes in BgNavvariants.

The amino acid positions refer to those in the published sequence of BgNav(GenBank accession number U73583).

| BgNav1-1 | R502G | L1285P | V1685A | I1806L | ||||

| BgNav1-2 | R45G | K184R | I1663M | N1798D | ||||

| BgNav1-3 | L453V | F396L | V1223A | M1637V | I1663M | I1899T | ||

| BgNav5 | R45G | V106M | K425R | Q694R | S1143G | I1663M | ||

| BgNav6 | M955V | S1143G | I1488M | I1663M | V1693A | |||

| BgNav7 | F143L | F821S | N1019D | F1028S | I1663M | T1915A | ||

| BgNav8 | R45G | F157S | H554Y | I630R | A823T | G1162R | E1649G | R1686G |

| BgNav9 | V75A | A414T | N795D | F820S | A1288P | L1348H | K1674R | D2030N |

| BgNav10 | R564G | D688G | S1032P | N1485S | I1663M | S1633A | ||

| BgNav11 | H635L | F1627L | P1679S | G1842S |

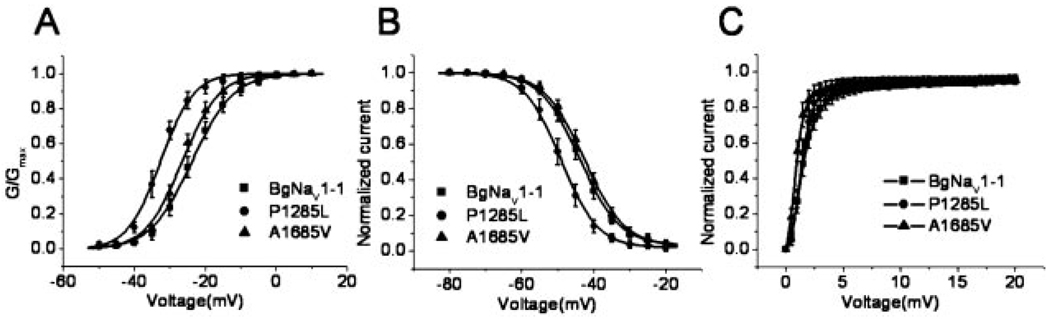

Both BgNav1-1 and BgNav1-2 activate at about 10 mV more depolarizing potentials than other variants. BgNav1-1 possesses four amino acid changes compared with the published sequence (Table III). Using site-directed mutagenesis, we individually changed these four residues in BgNav1-1 to the corresponding residues in the published BgNav sequence, producing four recombinant channels, G502R, P1285L, A1685V, and L1806I (e.g. for G502R: changing Gly in BgNav1-1 to Arg in the published sequence). Compared with the parental channel BgNav1-1, P1285L reverted the voltage dependence of activation by about 10 mV in the hyperpolarizing direction (Fig. 3 and Table IV). It also caused a 5-mV hyperpolarizing shift in the voltage dependence of steady-state inactivation (Fig. 3 and Table IV). The other three substitutions caused a subtle (3–4-mV) hyperpolarizing shift in activation but no effect on inactivation (Fig. 3 and Table IV). Therefore, Pro1285 in BgNav1-1 appears to be responsible for the large depolarization-required activation of the BgNav1-1 channel.

FIG. 3. P1285L shifted the voltage dependence of activation and inactivation in the hyperpolarizing direction.

The voltage dependence of activation (A), steady-state inactivation (B), and recovery from fast inactivation (C) were compared between BgNav1-1 and its two recombinant channels, P1285L (i.e. from Pro in BgNav1-1 to Leu in the available sequence) and A1685V. The recording protocols are described under “Experimental Procedures.” Symbols represent means; error bars represent S.D. values from at least nine oocytes.

TABLE IV. Gating properties of BgNav1-1 and its mutants.

The voltage dependence of conductance and inactivation was fitted with two-state Boltzmann equations, as described under “Experimental Procedures,” to determine V1/2, the voltage for half-maximal conductance or inactivation, and k, the slope factor for conductance or inactivation. Each value represents the mean ± S.D. for at least six oocytes.

| Activation |

Inactivation |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| V1/2 | k | V1/2 | k | |

| mV | mV | |||

| BgNav1–1 | −23.7 ± 1.8 | 5.4 ± 0.7 | −43.7 ± 1.2 | 5.2 ± 0.2 |

| G502R | −27.4* ± 1.1 | 5.3 ± 0.3 | −43.7 ± 0.7 | 4.8 ± 0.4 |

| P1285L | −32.6** ± 1.3 | 4.1 ± 1.0 | −48.9** ± 1.4 | 4.7 ± 0.2 |

| A1685V | −26.4* ± 1.8 | 4.7 ± 0.9 | −42.4 ± 1.1 | 5.3 ± 0.3 |

| L1806I | −26.6* ± 1.9 | 5.5 ± 0.6 | −44.5 ± 0.9 | 5.2 ± 0.2 |

Statistically significant difference compared with BgNav1-1 (p < 0.05).

Statistically significant difference compared with BgNav1-1 (p < 0.01)

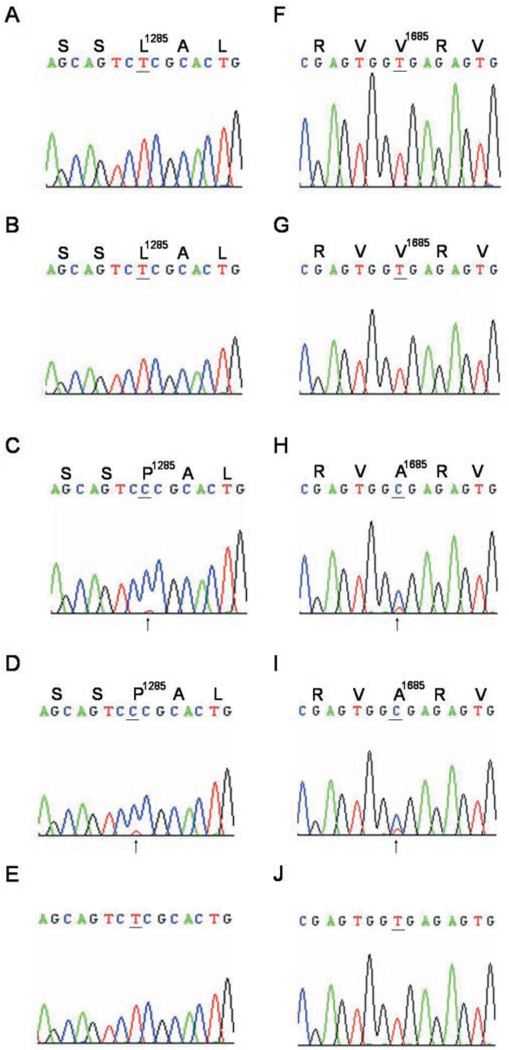

L1285P and V1685A Are the Result of Tissue-specific U-to-C Editing

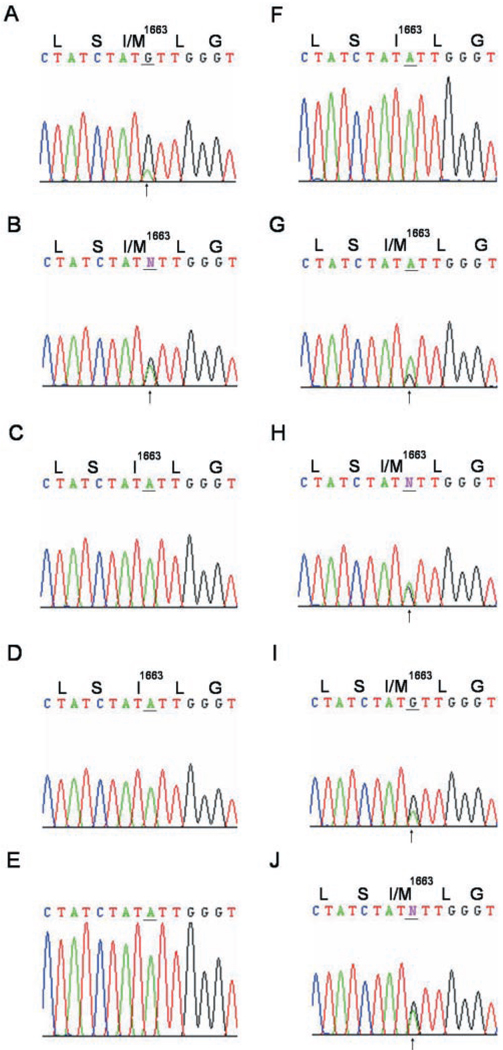

The L1285P change in BgNav1-1 resulted from a nucleotide change from T3854 to C3854. To examine whether this change is the result of RNA editing, we amplified an ~300-bp cDNA, which contains the L1285P change, using primers 16 and 17 and cDNA from heads/thorax, ovary, or gut (Fig. 4). Because the Leu (CTC) to Pro (CCC) change created a recognition site, CCCGC(N)4, for restriction enzyme FauI, we were able to determine the presence of T or C in the isolated clones by restriction enzyme digestion. All 46 clones isolated from head/thorax had a T at nucleotide 3854. However, we identified two types of clones from ovary and gut. Although most of the clones contain a T, 6 of 28 clones from ovary and 3 of 20 clones from gut contained a C at nucleotide 3854. An ~2.8-kb PCR fragment was amplified using the same PCR primer pair (primers 16 and 17) and genomic DNA as the template. Sequencing of the 2.8-kb fragment revealed a T at the corresponding position. Therefore, the Leu to Pro change in IIIS1 resulted from a U-to-C editing event, and this editing occurs only in ovary and gut. By convention, this editing site is designated as Leu/Pro site. Previous studies showed that when both edited and unedited transcripts were produced, direct sequencing of the reverse transcription-PCR products could sometimes result in mixed sequence signals in the chromatogram (29). We used direct sequencing of the reverse transcription-PCR product and found a double peak signal at the Leu/Pro site in ovary and gut but a single peak in nerve cord and leg of the same cockroach individuals (Fig. 5, A–D), further confirming that the Leu/Pro editing event is tissue-specific.

FIG. 4. Tissue-specific editing of Leu/Pro and Val/Ala sites.

Sequence analysis reveals single or double peak signals at the editing sites (underlined) in four tissues: nerve cord (A and F), leg (B and G), ovary (C and H), and gut (D and I) at the Leu/Pro and Val/Ala sites. Deduced amino acid sequences and the locations of the editing sites are indicated above the nucleotide sequences. The nucleotide sequences from genomic DNA are shown in E and J. The double peaks T and C (indicated by arrowheads) are detected in ovary and gut for both Leu/Pro and Val/Ala sites.

FIG. 5. Tissue-specific and development-specific editing of the Ile/Met site.

Sequence analysis reveals single or double peak signals at the Ile/Met site in four tissues: nerve cord (A), leg (B), ovary (C), and gut (D), and five developmental stages: embryonic I (F), II (G) and III (H); nymphal I (I) and II (J). Deduced amino acid sequences and the locations of the editing sites are indicated above the nucleotide sequences. The nucleotide sequence from genomic DNA is shown in E. The double peaks A and G are indicated by arrows.

In BgNav1-1, V1685A is also caused by a T5054 to C5054 change. To determine whether V1685A also resulted from U-to-C editing, we amplified a 213-bp fragment encoding IVS2–IVS4 using primers 18 and 19. We found a double peak signal, C5054 and T5054, in a fragment amplified from ovary and gut (Fig. 5, F and G). However, a single sequence signal (T) was found in nerve cords and legs of the same cockroach individuals (Fig. 5, H and I). Furthermore, a T corresponding to T5054 was found in a 7-kb genomic DNA amplified using the same PCR primer pair (Fig. 5J). Therefore, we identified a second U-to-C editing site, resulting in a Val to Ala change in IVS4, designated as the Val/Ala site. Both the L1285P and V1685A changes were detected in ovary and gut, but not in the nerve cord or leg. Therefore, BgNav1-1 is an ovary- and gut-specific variant.

Identification of Two A-to-I Editing Sites in BgNav

BgNav1-2 possesses four amino acid changes, R45G, K184R, I1663M, and N1787D, compared with the available sequence (Table III). I1663M, resulting from an A4989 to G4989 change, was found in 6 of the 9 sequenced full-length cDNA clones (Table III). PCR analysis of the remaining clones using a sequence-specific primer revealed that 49 of 69 clones contain G4989 and the remaining 20 possess A4989. To determine whether I1663M is caused by RNA editing, we amplified a 213-bp fragment encoding IVS2–IVS4, where A4989 is located, using primers 18 and 19 and RNA isolated from head/thorax. Sequencing of the PCR fragment revealed the mixed A and G signal at nucleotide 4989 (Fig. 5A). To determine whether the mixed A and G signal was present in BgNav transcripts expressed in various tissues, we amplified the same region using RNA from nerve cord, leg, ovary, and gut and sequenced the PCR products. A double A and G signal was detected in nerve cord and leg (Fig. 5, A and B), but a single G was found in ovary and gut (Fig. 5, C and D). Furthermore, genomic DNA sequencing revealed an A at the corresponding position (Fig. 5E). Collectively, these results demonstrated that the A4989 to G4989 change was caused by an A-to-I RNA editing, resulting in an amino acid change from an Ile1663 to an Met1663 in IVS3. We designated this site as the Ile/Met site, the first A-to-I RNA editing site in the German cockroach sodium channel.

In addition to its tissue-specific regulation, this A-to-I RNA editing event was also regulated developmentally. We examined the developmental profile of edited and unedited transcripts in five developmental stages, three embryonic stages (I, II, and III) and two immature stages (nymph I and II). Sequencing analysis showed that the unedited transcript (carrying A4989), but not the edited one (carrying G4989), was found in the embryonic stage I, during which no cellular differentiation had occurred yet (Fig. 5F). Both unedited and edited transcripts were present in the rest of the development stages (Fig. 5, G–J). These results indicate the A4989 to G4989 editing event is initiated in the embryo, probably concurrent with the development of the nervous system.

To determine whether K184R is the result of RNA editing, we amplified a 216-bp fragment encoding IS1 to IS2 using primers 20 and 21. A total of 70 cDNA clones were isolated and the inserts sequenced. One of 70 clones contained a G551, which resulted in a Lys (AAG) to Arg (AGG) change in the amino acid sequence. The remaining 69 clones contain an A551. We sequenced the corresponding genomic PCR fragment amplified using the same primer pair. The nucleotide A was present in the genomic DNA. No alternative exon containing T was found. Therefore, we identified a possibly second A-to-I editing resulting in the K184R change in the cockroach sodium channel transcript. This editing site is designated as the Lys/Arg site. This RNA editing appears to occur at a low frequency compared with the Ile/Met editing site.

The remaining two amino acid changes, R45G and N1787D, in BgNav1-2 are both caused by an A to G change. For N1787D, we isolated 75 partial cDNA clones from head and thorax tissues. Sequence analysis revealed an A in all 75 partial cDNA clones. Therefore, whether N1787D is caused by an A-to-I editing event could not be ascertained. It could be because of a PCR error in the amplification of full-length cDNA clones. On the other hand, R45G was present not only in BgNav1-2 but also in variant BgNav5 with a completely different exon usage. Therefore, it is likely caused by an A-to-I editing. Thus, we identified two A-to-I editing events in BgNav1-2, which resulted in Ile to Met and Lys to Arg changes. We suggest that R45G is also generated from an A-to-I editing. Because of low frequencies of K184R and R45G, future larger scale analysis may be needed to substantiate the conclusion of the generation of these two changes by A-to-I RNA editing.

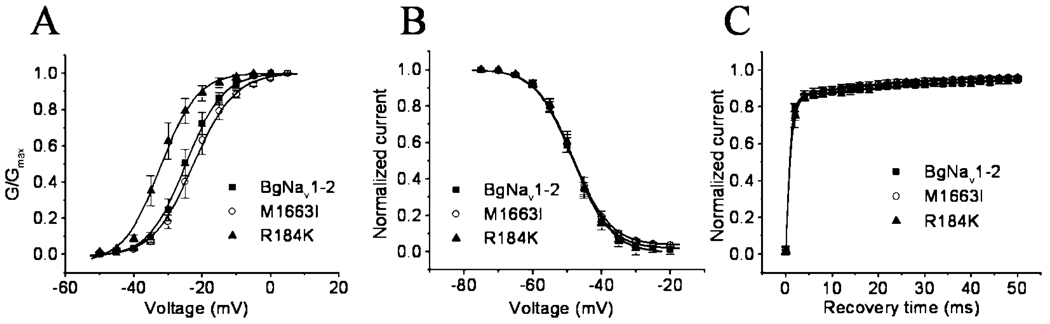

K184R Is Responsible for the Distinct Gating Properties of BgNav1-2

To determine which amino acid change is responsible for the requirement of more membrane depolarization for activation of BgNav1-2, we individually changed the amino acid residues and examined the mutant channel gating properties. The Arg to Lys substitution reverted the voltage dependence of activation by 7 mV in the hyperpolarizing direction, indicating that Arg184 is responsible for the more depolarization-required activation of the BgNav1-2 channel. None of the other mutations altered the gating properties, including voltage-dependent activation, steady-state inactivation, and recovery from fast inactivation (Fig. 6 and Table V).

FIG. 6. R184K shifted the voltage dependence of activation in the hyperpolarizing direction.

The voltage dependence of activation (A), steady-state inactivation (B), and recovery from fast inactivation (C) were compared between BgNav1-2 and its two single-amino acid substitutions derivatives, R184K (i.e. from Arg in BgNav1-2 to Lys in the available sequence) and M1663I. The recording protocols are described under “Experimental Procedures.” Symbols represent means; error bars represent S.D. values from at least eight oocytes.

TABLE V. Gating properties of BgNav1-2 and its mutants.

The voltage dependence of conductance and inactivation was fitted with two-state Boltzmann equations, as described under “Experimental Procedures,” to determine V1/2, the voltage for half-maximal conductance or inactivation, and k, the slope factor for conductance or inactivation. Each value represents the mean ± S.D. for at least five oocytes.

| Activation |

Inactivation |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| V1/2 | k | V1/2 | k | |

| mV | mV | |||

| BgNav1-2 | −24.9 ± 1.4 | 4.9 ± 0.4 | −49.0 ± 0.7 | 4.8 ± 0.2 |

| G45R | −24.8 ± 2.4 | 4.9 ± 0.4 | −47.1 ± 1.5* | 5.0 ± 0.2 |

| R184K | −31.8 ± 2.4* | 4.2 ± 0.5 | −48.3 ± 1.0 | 4.7 ± 0.1 |

| M1663I | −23.4 ± 1.8 | 5.2 ± 0.4 | −49.0 ± 1.5 | 4.9 ± 0.1 |

| D1798N | −22.3 ± 1.9 | 5.4 ± 0.7 | −48.2 ± 1.1 | 4.8 ± 0.3 |

Statistically significant difference compared with BgNav1-2 (p < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we identified 20 splice types of the cockroach sodium channel BgNav. The electrophysiological characterization of these variants in Xenopus oocytes revealed an impressive spectrum of differences in the level of sodium current expression and the voltage-dependent activation and/or inactivation among cockroach sodium channel variants. We found that exclusion or inclusion of an optional exon, exon B, modulates the sodium current expression. We identified two A-to-I RNA editing sites and two U-to-C editing sites, each resulting in amino acid changes in transmembrane segments. Two of these editing events significantly alter the voltage dependence of activation and/or inactivation. Furthermore, these RNA editing events occur only in specific tissues, generating tissue-specific insect sodium channels. Thus, this study not only represents a comprehensive functional characterization of sodium channel variants in insects, but also provides the first direct evidence for the involvement of RNA editing in modification of sodium channel gating properties.

Functional Complexity of Insect Sodium Channel Variants

Results presented here clearly suggest that a high level of functional plasticity of a sodium channel can be generated from a single gene via post-transcriptional modifications. For example, BgNav11 activates at more negative membrane potentials, e.g. −60 mV, whereas others require more membrane depolarization, such as −45 mV, for channel activation. Similarly, the half-maximal voltages for the voltage dependence of steady-state inactivation range from −37 to −60 mV. BgNav7 has a significant overlap between the voltage dependence of activation and the voltage dependence of steady-state inactivation, with V½ values of −36.7 and −37.2 mV for activation and inactivation, respectively. Consequently, this variant produces a large window current over a range of −45 mV to −25 mV, which could lead to membrane depolarization at subthreshold potentials, resulting in oscillatory activities, summation of synaptic input, or controlling firing frequency, and so on (32). Thus, even though insects carry only a single sodium channel gene, a combination of alternative splicing and RNA editing of the primary transcript can apparently produce a full complement of functionally diverse sodium channels. It is therefore likely that mammals have evolved to rely on multiple sodium channel genes to produce functionally distinct isoforms, whereas insects must depend on extensive alternative splicing and RNA editing of a single sodium channel gene to fulfill specialized roles of sodium channel activity in different cell types/tissues.

Alternative Exon B Modulates Sodium Current Expression

Significant variation in the amplitude of peak current was recorded from sodium channels in Drosophila embryonic neurons (33). Single cell reverse transcription-PCR and recording analysis by O’Dowd and associates (19) showed that exon a in Drosophila para is necessary but not sufficient for the expression of sodium current in cultured embryonic neurons. However, Warmke et al. (9) reported no significant difference in sodium current expression and gating properties between para splice variants with or without exon a. In this study, we observed poor sodium current expression of variants containing exon B (equivalent to exon b in Drosophila para) (Fig. 3). Exon swapping experiments showed that exclusion of exon B is critical for robust expression of sodium currents in oocytes. Considering that the location and sequence of this exon are highly conserved in Drosophila para (Fig. 1A) and also in house fly Vssc1 (21), the role of exon b/B in regulating insect sodium current expression may be universal. Down-regulation of sodium current expression by protein kinases has been documented for mammalian sodium channels (34–38). Because exon B is located in the first intracellular linker and contains a consensus sequence for phosphorylation, this exon could serve as a regulatory on-or-off switch regulating the neuronal excitability by responding to second messengers or G protein-coupled modulation signals to meet unique physiology in given tissues or cell types. Interestingly, we found that one splice variant, BgNav7-1, also contains exon B yet produced detectable sodium currents in oocytes, suggesting the involvement of additional sequences in modulating sodium current expression.

Both A-to-I and U-to-C RNA Editing Contributes to Sodium Channel Functional Diversity

Among all RNA editing types, A-to-I editing is the most prevalent one found in the nervous system (see below), whereas U-to-C editing is reported only in a very few transcripts in animals (39–41). About a dozen transcripts encoding ion channels, neurotransmitter receptors, or G protein-coupled receptors are substrates of A-to-I editing. The well characterized examples include A-to-I editing in mammalian glutamate-gated receptor channels, which mediate excitatory synaptic transmission in the central nervous system (42 and refs. therein), mammalian serotonin 2C receptor (25, 26), and squid voltage-gated potassium channels (27, 28). In each case, edited channels or receptors exhibit distinct functional and/or pharmacological properties. For example, A-to-I editing at a Gln/Arg site of the Glu receptor subunit B RNA results in a drastic decrease in the Ca2+ permeability of subunit B-containing Glu receptor (43). Editing at an Arg/Glu site, by contrast, results in faster recovery rates from Glu receptor channel desensitization (44). A-to-I editing in serotonin 2C receptor transcripts reduces the affinity of the receptor for its G protein (25). Extensive A-to-I editing of potassium channel mRNAs generates functionally distinct channels and regulates subunit tetramerization (27, 28). A-to-I editing has also been reported in several transcripts in the nervous system of D. melanogaster: a Ca2+ channel α1 subunit (45), a glutamate-gated Cl− channel (46), the para sodium channel (47, 48), and subunits of a putative nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (49). 10 A-to-I editing sites have been reported in the para transcript (47, 48). However, the functional consequences of A-to-I editing in para remain elusive prior to this study.

Here, we identified two novel U-to-C editing sites, Leu/Pro and Val/Ala, in BgNav1-1 causing the L1285P change in IIIS1 and the V1685A change in IVS4. We also identified two novel A-to-I editing sites in BgNav1-2, Lys/Arg and Ile/Met, resulting in the K184R change in IS2 and the I1663M change in IVS3. Both BgNav1-1 and BgNav1-2 activate at about 10 mV more depolarizing potentials than other variants. Furthermore, BgNav1-1 also inactivates at about 10 mV more depolarizing potentials than other variants. Our site-directed mutagenesis results showed that eliminating the U-to-C editing at the Leu/Pro site rendered BgNav1-1 to activate and inactivate at more hyperpolarizing membrane potentials. Similarly, abolishment of the A-to-I editing at the Lys/Arg site shifted the voltage dependence of activation of BgNav1-2 a more hyperpolarizing potential. Clearly, these editing events are responsible for more-depolarization-required activation of BgNav1-1 and BgNav1-2. The modification of sodium channel gating properties by RNA editing supports the notion that one major role of RNA editing is the fine tuning of the neuronal activity (23).

RNA editing at the Ile/Met and Val/Ala sites did not alter any sodium channel gating properties. However, both editing events were regulated in a tissue-specific manner. In fact, RNA editing at the Ile/Met site occurs in a high frequency. The importance of these two editing events remains unclear. It is possible that the effects of these RNA editing events require additional cellular signals present only in specific tissues/cell type, but absent in Xenopus oocytes.

Tissue-specific RNA Editing

We show that the Leu/Pro and Val/Ala editing events occur only in ovary and gut. Tissue-specific regulation of RNA editing events suggests a more specialized role of edited channels in specific tissues or cell types. BgNav1-1, edited at both Leu/Pro and Val/Ala sites, therefore represents an ovary- and gut-specific variant. BgNav1-1 may be expressed in neurons that innervate the ovary and gut. Because BgNav1-1 and BgNav1-2 activate at more depolarizing potentials than other variants, neurons expressing these variants would have a higher threshold for firing action potentials and a decrease in neuronal excitability compared with neurons expressing the unedited variants.

In summary, we demonstrated here the extraordinary ability of a single insect sodium channel gene to produce a wide array of sodium channels with distinct functional properties. We found that, in addition to alternative splicing, RNA editing is a major mechanism for increasing sodium channel functional plasticity. Understanding the physiological roles of different alternatively spliced and/or RNA-edited sodium channel variants in insects and the mechanisms by which tissue-/cell type-specific splicing and RNA editing are controlled is clearly important for future research.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Dalia Gordon, Noah Koller, and Vincent Salgado for critical review of an early version of this manuscript and Michelle Carlson for editorial assistance.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Science Foundation Grants IBN98081 and IBN0224877.

Domains are designated with Roman numerals and segments within the domains with Arabic numbers; for example IS2-3 is domain I, segment 2–3.

REFERENCES

- 1.Catterall WA. Neuron. 2000;26:13–25. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81133-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldin AL, Barchi RL, Caldwell JH, Hofmann F, Howe JR, Hunter JC, Kellen RG, Mandel G, Meisler MH, Netter YB, Noda M, Tamkun MM, Waxman SG, Wood JN, Catterall WA. Neuron. 2000;28:365–368. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Catterall WA, Goldin AL, Waxman SG. Pharmacol. Rev. 2003;55:575–578. doi: 10.1124/pr.55.4.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldin AL. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2001;63:871–894. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.63.1.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dib-Hajj SD, Black JA, Cummins TR, Waxman SG. Trends Neurosci. 2002;25:253–259. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(02)02150-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu FH, Catterall WA. Genome Biol. 2003;4:207.1–207.7. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-3-207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loughney K, Kreber R, Ganetzky B. Cell. 1989;58:1143–1154. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90512-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feng G, Deak P, Chopra M, Hall LM. Cell. 1995;82:1001–1011. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90279-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Warmke JW, Reenan RAG, Wang P, Qian S, Arena JP, Wang J, Wunderler D, Liu K, Kaczorowski GJ, Van Der Ploeg LHT, Ganetzky B, Cohen CJ. J. Gen. Physiol. 1997;110:119–133. doi: 10.1085/jgp.110.2.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith TJ, Lee SH, Ingles PJ, Knipple DC, Soderlund DM. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1997;27:807–812. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(97)00065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tan J, Liu Z, Tsai T-D, Valles SM, Goldin AL, Dong K. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2002;32:445–454. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(01)00122-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tan J, Liu Z, Nomura Y, Goldin AL, Dong K. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:5300–5309. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-13-05300.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sarao R, Gupta SK, Auld VJ, Dunn RJ. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:1873–1879. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.20.5673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schaller KL, Krzemien DM, McKenna NM, Caldwell JH. J. Neurosci. 1992;12:1370–1381. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-04-01370.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gustafson TA, Clevinger EC, O’Neill TJ, Yarowsky PJ, Krueger BK. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:18648–18653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thackeray JR, Ganetzky B. J. Neurosci. 1994;14:2569–2578. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-05-02569.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thackeray JR, Ganetzky B. Genetics. 1995;141:203–214. doi: 10.1093/genetics/141.1.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Dowd DK, Gee JR, Smith MA. J. Neurosci. 1995;15:4005–4012. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-05-04005.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dietrich PS, McGivern JG, Delgado SG, Koch BD, Eglen RM, Hunter JC, Sangameswaran L. J. Neurochem. 1998;70:2262–2272. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70062262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Plummer NW, McBurney MW, Meisler MH. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:24008–24015. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.38.24008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee SH, Ingles PJ, Knipple DC, Soderlund DM. Invert. Neurosci. 2002;4:125–133. doi: 10.1007/s10158-001-0014-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bass BL. RNA Editing. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seeburg PH. Neuron. 2000;25:261–263. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80891-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seeburg PH. Neuron. 2002;35:17–20. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00760-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burns CM, Chu H, Rueter SM, Hutchison LK, Canton H, Sanders-Bush E, Emeson RB. Nature. 1997;387:303–308. doi: 10.1038/387303a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Niswender CM, Copeland SC, Herrick-Davis K, Emeson RB, Sanders-Bush E. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:9472–9478. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.14.9472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patton DE, Silva T, Bezanilla F. Neuron. 1997;19:711–722. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80383-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenthal JJC, Bezanilla F. Neuron. 2002;34:743–757. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00701-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palladino MJ, Keegan LP, O’Connell MA, Reenan RA. Cell. 2000;102:437–449. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00049-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bell WL. The Laboratory Cockroach. New York: Chapman and Hall; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dong K. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1997;27:93–100. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(96)00082-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crill WE. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1996;58:349–362. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.58.030196.002025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Byerly L, Leung H. J. Neurosci. 1988;8:4379–4393. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-11-04379.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Numann R, Catterall WA, Scheuer T. Science. 1991;254:115–118. doi: 10.1126/science.1656525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.West JW, Numann R, Murphy BJ, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Science. 1991;254:866–868. doi: 10.1126/science.1658937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith RD, Goldin AL. J. Neurosic. 1996;16:1965–1974. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-06-01965.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith RD, Goldin AL. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:6066–6093. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith RD, Goldin AL. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2000;278:C638–C645. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.278.4.C638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nagalla SR, Barry BJ, Spindel ER. Mol. Endocrinol. 1994;8:943–951. doi: 10.1210/mend.8.8.7997236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sharma PM, Bowman M, Madden SL, Rauscher FJ, III, Sukumar S. Genes Dev. 1994;8:720–731. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.6.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Villegas J, Muller I, Arredondo J, Pinto R, Burzio L. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:1895–1901. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.9.1895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seeburg PH, Higuchi M, Sprengel R. Brian Res. Rev. 1998;26:217–229. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(97)00062-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sommer B, Kohler M, Sprengel R, Seeburg PH. Cell. 1991;67:11–19. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90568-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lomeli H, Mosbacher J, Melcher T, Hoger T, Geiger JR, Kunker T, Monyer H, Higuchi M, Bach A, Seeburg PH. Science. 1994;266:1709–1713. doi: 10.1126/science.7992055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith LA, Peixoto AA, Hall JC. J. Neurogenet. 1998;12:227–240. doi: 10.3109/01677069809108560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Semenov EP, Park WL. J. Neurochem. 1999;72:66–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0720066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reenan RA, Nanrahan CJ, Ganetzky B. Neuron. 2000;25:139–149. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80878-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hanrahan CJ, Palladino MJ, Ganetzky B, Reenan RA. Genetics. 2000;155:1149–1160. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.3.1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grauso M, Reenan RA, Culetto E, Sattelle DB. Genetics. 2002;160:1519–1533. doi: 10.1093/genetics/160.4.1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]