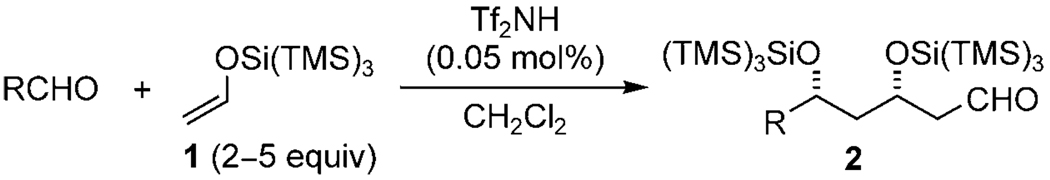

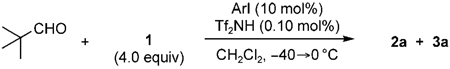

Polyketides have long provided synthetic organic chemists with a variety of complex architectures to construct and develop new chemical tools for, and provided medicine with, many useful drugs. About 1% of polyketides display drug activity, which is five times the average for natural products.[1] A common strategy in the synthesis of polyketides is the cross-aldol reaction, although it can be complicated by uncontrolled oligomerization and dehydration reactions.[2] There has been significant advances in the development of the asymmetric aldol and allylation reactions of aldehydes.[3,4] However, further manipulations, such as alcohol protection or redox reactions, are often required before the next iteration can proceed. Therefore, there has been increasing interest in one-pot cascade aldol reactions;[5, 6] however, only one example successfully proceeded to the third aldol iteration, and in low yields.[5a] Inspired by the seminal work of Mukaiyama et al.,[2a] our research group reported an aldol cascade reaction using tris(trimethylsilyl)silyl enol ethers, such as the easily prepared 1,[7] to give versatile aldehyde products 2 (Scheme 1). Moreover, these aldehydes can be treated with Grignard or polyhalomethyllithium reagents in the same reaction pot to generate mono-protected diols.[8] The formation of these compounds is highly diastereoselective because of the extreme steric bulk of the tris(trimethylsilyl) silyl group.[7a, 8a, 9] Significantly, further addition of 1 to 2 is strictly prevented, because of the steric bulk of the (TMS)3SiNTf2·2 complex.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of 3,5-disilyloxyaldehydes utilizing silyl enol ether 1. TMS=trimethylsilyl; Tf=trifluoromethanesulfonyl.

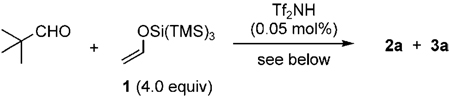

We set out with the challenging aim of extending this aldol cascade reaction to three or more additions of 1 to an aldehyde for the construction of polyketides in a minimal number of steps. Despite several attempts, treatment of dimethylpropanal with 1 (4.0 equivalents) and Tf2NH in dichloromethane gave only the double-aldol product 2a (R=tBu), without the formation of any triple-aldol product 3a (Table 1, entry 1). Heating the reaction mixture also failed to produce the desired triple aldol adduct. Evidently, a new approach was required. Simple solvent screening had interesting effects on the reaction: performing the reaction in hexane or toluene gave only the mono-aldol adduct (Table 1, entries 2 and 3), whilst when chlorobenzene or perfluorooctane were used, 2a was obtained in 60 and 20% yields, respectively, with little or no formation of 3a (Table 1, entries 4 and 5).

Table 1.

Optimization of the triple aldol reaction.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Solvent |

T [°C] |

Additive [mol%] |

Yield of 2a [%][a] |

Yield of 3a [%][a,b] |

| 1 | CH2Cl2 | 0 to 40 | none | 75 | 0 |

| 2 | hexanes | 23 to 65 | none | <5 | 0 |

| 3 | toluene | −78 to 80 | none | <5 | 0 |

| 4 | PhCl | 0 to 50 | none | 60 | <5 |

| 5 | C8F18 | 0 to 60 | none | 20 | <5 |

| 6 | CH2Cl2 | 0 to 23 | ICH2CH2I (10) | 37 | 31 |

| 7 | CH2Cl2 | −78 to 23 | MeI (10) | 71 | 13 |

| 8 | CH2Cl2 | −40 to 0 | PhI (10) | 30 | 52 |

| 9 | CH2Cl2 | −40 to 23 | 1,2-C6H4I2 (10) | 49 | 27 |

| 10 | CH2Cl2 | −40 to 23 | 2-I-py (10) | <5 | 0 |

| 11[c] | CH2Cl2 | −40 to 23 | I2 (5.0) | 65 | 7 |

| 12[c] | CH2Cl2 | −40 to 23 | PhI (10) | <5 | 85 |

| 13[c] | CH2Cl2 | −40 to 0 | PhI (10) | 64 | 32 |

| 14[c] | CH2Cl2 | 0 | PhI (10) | 29 | 51 |

| 15[c] | CH2Cl2 | 23 | PhI (10) | 15 | 47 |

| 16[c] | CH2Cl2 | −40 to 0 | PhI (2.0) | 12 | 77 |

| 17[c] | CH2Cl2 | −40 to 0 | PhI (0.5) | 46 | 26 |

Yield of combined isolated diastereomers.

d.r.=87:10:2:<1 as determined by crude 1H NMR spectroscopic and HPLC analyses.

5.0 equivalents of 1.

Because the solvent seemed to be playing a critical role in affecting the active catalytic species, different additives were then screened. The use of a substoichiometric amount of 1,2-diiodoethane, which was chosen because 3a was formed in low yield when 1,2-dichloroethane was used as the reaction solvent, gave 2a and 3a in 37 and 31% yields, respectively (Table 1, entry 6). Surprised by the large effect that the iodine-containing additive had on the reaction, other iodides were screened. Iodomethane gave 2a and 3a in 71 and 13% yields, respectively, and iodobenzene afforded the products in 30 and 52% yields, respectively (Table 1, entries 7 and 8). The use of two other aryl iodides, 1,2-diiodobenzene and 2-iodopyridine, were less successful (Table 1, entries 9 and 10). Finally, the use of I2 as an additive proved ineffective in forming 3a (Table 1, entry 11). Therefore, iodobenzene was chosen to be the optimal additive for our investigation.

This reaction was optimized using iodobenzene as an additive and dichloromethane as the solvent. Gratifyingly, 3a was obtained in a remarkable 85% yield when the reaction was performed at −40 to 0°C, using 5.0 equivalents of 1 (Table 1, entry 12). The temperature played a critical role in the generation of 3a. Too low a reaction temperature did not allow the third aldol reaction to occur, whereas too high a temperature caused decomposition of 1, 2a, and 3a (Table 1, entries 13–15). Although, the amount of iodobenzene could be lowered (Table 1, entries 16 and 17), it caused a decrease in the yield of 3a.

With our optimized triple-aldol reaction conditions in hand, the aldehyde substrate scope was then investigated (Table 2). Octanal and cyclohexanecarboxaldehyde were good substrates for the triple-aldol reaction, giving 3b and 3c along with their minor diastereomers in 84 and 87% yields, respectively (Table 2, entries 1 and 2). This reaction was tolerant of different functionalities on the aldehyde. Benzyloxyacetaldehyde and 3-tert-butyldimethylsilyloxypropanal gave 3d and 3e in 75 and 87% yields, respectively (Table 2, entries 3 and 4). Furthermore, 3-nitropropanal produced 3f and its minor diastereomers in 89% yield (Table 2, entry 5). Chiral aldehydes 2-phenylpropanal and 3-triisopropylsilyloxybutanal afforded 3g and 3h in 54% and 57% yields, respectively, as a mixture of easily separated diastereomers (Table 2, entries 6 and 7).

Table 2.

Scope of the aldehyde substrate in the triple-aldol reaction with 1.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Product | Yield [%][a] | d.r.[b] | |

| 1 | 3b | 84 | 79:10:9:<2 | |

| 2 | 3c | 87 | 81:9:8:<2 | |

| 3 | 3d | 75 | 81:9:8:<2 | |

| 4 | 3e | 87 | 71:14:12:2 | |

| 5[c] | 3f | 89 | 87:8:3:2 | |

| 6 | 3g | 54 | –[d] | |

| 7[e] | 3h | 57 | –[d] | |

Yield of combined isolated diastereomers, unless otherwise noted.

The diastereomeric ratios were determined by crude 1H NMR spectroscopic and HPLC analyses.

0.2 mol% Tf2NH was used.

this yield is for the diastereomer shown only;

10 mol% 1-iodo-3,3-dimethyl-1-butyne was employed in this reaction. Cy=cyclohexyl, Bn=benzyl, TBS=tert-butyldimethylsilyl, TIPS=triisopropylsilyl.

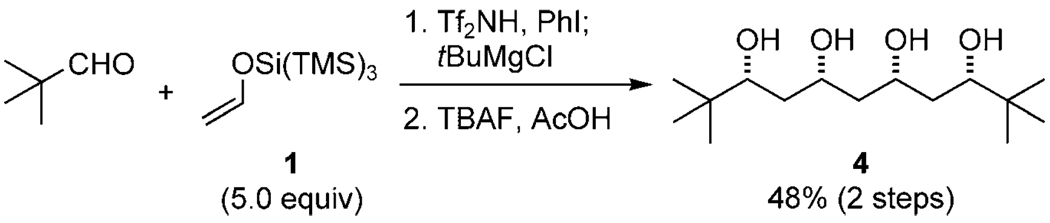

The relative configurations for aldehydes 3 were elucidated from their reduction and subsequent deprotection with TBAF or UV light,[10] utilizing the powerful NMR spectroscopy method described by Kishi and Kobayashi (for full details, see the Supporting Information).[11] Furthermore, 3a could be treated with tBuMgCl in the same reaction vessel to generate a meso tetraol (4) after deprotection (Scheme 2). This method is able to create four C–C bonds and four stereocenters in high efficiency in a one-pot operation.

Scheme 2.

One-pot preparation of tetraol 4. TBAF=tetrabutylammonium fluoride.

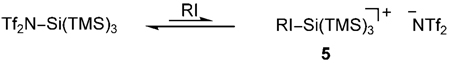

Intrigued by the critical role of iodobenzene in the promotion of the third aldol reaction in this cascade, the following experiments were designed. With the hypothesis in mind that iodobenzene is acting as a Lewis base towards (TMS)3SiNTf2, the steric and electronic environments of iodobenzene were varied. Somewhat sterically more-hindered aryl iodides had little effect on the synthesis of 3a (Table 3, entries 2 and 3), whereas a very bulky aryl iodide gave diminished reactivity (Table 3, entry 5). The electronically less-Lewis-basic 1-iodo-3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)benzene was also less effective as an additive (Table 3, entry 4). Indeed, the mass spectra of (TMS)3SiNTf2 in the presence of iodobenzene showed signals at m/z 536 and 656, which correspond to [(TMS)3Si + IPh + CH2Cl2]+ and [(TMS)3Si + (IPh)2]+, respectively. These results are supported by the previously reported crystal structure of 1,2-dichlorobenzene and iPr3Si+ [CHB11Cl11]−.[12] Although 29Si NMRspectroscopy experiments with (TMS)3SiNTf2 did not show a significant difference on addition of iodobenzene (Δδ=0.4 ppm of the central silicon atom), this could be due to the rapid equilibration or a screening effect of the multiple TMS groups.

Table 3.

Perturbation of the aryl iodide.

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yield [%][a] | |||

| Entry | ArI | 2a | 3a |

| 1[b] | iodobenzene | 29 (<5) | 51 (85) |

| 2 | 1,3-dimethyl-2-iodobenzene | 73 | 24 |

| 3 | 3,5-dimethyl-1-iodobenzene | 52 | 40 |

| 4 | 1-iodo-3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)benzene | 78 | 12 |

| 5 | 1-iodo-2,4,6-triisopropylbenzene | 87 | 7 |

Yield of combined isolated diastereomers.

Yields in parentheses refer to when 5.0 equivalents of 1 are employed.

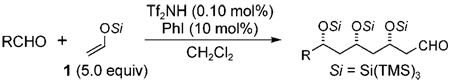

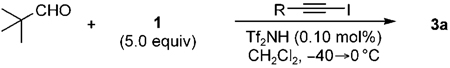

In the search for a better co-catalyst for the triple-aldol cascade reaction, we required a smaller yet electronically stabilized organoiodide. Towards this end, a 1-iodo-2-phenylacetylene was prepared, and it proved to be a more effective additive than iodobenzene for the production of 3a, effective as low as 0.1 mol% (Table 4, entries 1–4). 1-Iodo-3,3-dimethyl-1-butyne further improved the production of 3a to 85 and 77% yields, when employed in 0.5 and 0.1 mol%, respectively. These results showed little drop-off in the yield of 3a, as compared to the yields in Table 2, and clearly demonstrate the power of using organoiodides in this reaction.

Table 4.

Improved organoiodide co-catalysts.

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Entry | R [mol%] | Yield [%][a] |

| 1 | Ph (10) | 80 |

| 2 | Ph (2.0) | 71 |

| 3 | Ph (0.5) | 65 |

| 4 | Ph (0.1) | 56 |

| 5 | tBu (0.5) | 85 |

| 6 | tBu (0.1) | 77 |

Yield of combined isolated diastereomers.

We propose that organoiodides (RI) can react with (TMS)3SiNTf2, to afford the cationic and sterically less-demanding complex 5 [Eq. (1)], in analogy with the crystal structure reported by Reed and co-workers.[12] This more-reactive complex is able to promote the reaction of 1 and 2.

|

(1) |

In summary, we have developed an efficient triple-aldol cascade reaction for the preparation of 3,5,7-trisilyloxy aldehydes in high diastereoselectivities from a diverse set of simple aldehydes. This method can produce these complex structures with unprecedented ease. The key to allowing the triple-aldol reaction to proceed efficiently was the addition of iodobenzene or 1-iodoalkynes, which generated a more reactive catalytic system. However, as an asymmetric version of this reaction is not yet available, simple chiral aldehydes can be employed in this reaction to generate enantiopure complex aldehydes 3 with unmatched speed.

Experimental Section

Representative procedure for the triple aldol condensation of aldehydes and silyl enol ether 1: A stirred solution of 1 (729 mg, 2.50 mmol), PhI (5.6 µL, 0.050 mmol), and dimethylpropanal (55 µL, 0.50 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (2.5 mL) was cooled to −40°C before Tf2NH (0.010m in CH2Cl2, 50 µL, 0.50 µmol) was added to the mixture. The reaction mixture was stirred for 30 minutes at the same temperature, then warmed to 0°C. After an additional 30 minutes at the same temperature, the reaction was quenched by the addition of a pH 7 buffer (5 mL). The layers were separated, and the aqueous phase was extracted with dichloromethane (3 mL). The combined organic layers were dried over Na2SO4, filtered through cotton, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The resulting residue was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel (50 mL) eluting with dichloromethane/hexanes (1:19→1:4) to give 3a (409 mg, 85%) as a white foam.

Footnotes

This work was made possible by the generous support of NIH (P50 GM086 145-01) and the University of Chicago. We would additionally like to thank Antoni Jurkiewicz for his NMR expertise and Prof. V. V. Fokin for insightful discussions.

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/anie.200907076.

Contributor Information

Brian J. Albert, Department of Chemistry, The University of Chicago, 5735 South Ellis Avenue, Chicago, IL 60635 (USA)

Hisashi Yamamoto, Department of Chemistry, The University of Chicago, 5735 South Ellis Avenue, Chicago, IL 60635 (USA).

References

- 1.a) Rohr J. Angew. Chem. 2000;112:2967. [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2000;39:2847–2849. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20000818)39:16<2847::aid-anie2847>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Rychnovsky SD. Chem. Rev. 1995;95:2021–2040. [Google Scholar]; c) Koskinen AMP, Karisalmi K. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2005;34:677–690. doi: 10.1039/b417466f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Mukaiyama T, Narasaka K, Banno K. Chem. Lett. 1973:1011–1014. [Google Scholar]; b) Kato J, Mukaiyama T. Chem. Lett. 1983:1727–1728. [Google Scholar]; c) Kohler BAB. Synth. Commun. 1985;15:39–42. [Google Scholar]

- 3.For cross-aldol reactions, see: Mukaiyama T. Organic Reactions. Vol. 28. New York: Wiley; 1982. pp. 203–331. Heathcock CK, Kim BM, Williams SF, Masamune S, Rathke MW, Weipert P, Paterson I. Comprehensive Organic Synthesis. Vol. 2. Oxford: Pergamon; 1991. pp. 133–319. Nelson SG. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 1998;9:357–389. Mahrwald R. Chem. Rev. 1999;99:1095–1120. doi: 10.1021/cr980415r. Denmark SE, Ghosh SK. Angew. Chem. 2001;113:4895–4898. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001;40:4759–4762. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20011217)40:24<4759::aid-anie4759>3.0.co;2-g. Northrup AB, MacMillan DWC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:6798–6799. doi: 10.1021/ja0262378. Denmark SE, Bui T. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:10190–10193. doi: 10.1021/jo0517500. Iwata M, Yazaki R, Suzuki Y, Kumagai N, Shibasaki M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:18244–18245. doi: 10.1021/ja909758e..

- 4.For the allylation of aldehydes, see: Fleming I. In: Comprehensive Organic Synthesis. Trost BM, editor. Vol. 2. Oxford: Pergamon; 1991. pp. 563–593. Yamamoto Y, Asao N. Chem. Rev. 1993;93:2207–2293. Denmark SE, Fu J. Chem. Rev. 2003;103:2763–2793. doi: 10.1021/cr020050h..

- 5.a) Gijsen HJM, Wong C-H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:7585–7591. [Google Scholar]; b) Yun S-S, Suh I-H, Choi S-S, Lee S. Chem. Lett. 1998:985–986. [Google Scholar]; c) Haeuseler A, Henn W, Schmittel M. Synthesis. 2003:2576–2589. [Google Scholar]; d) Casas J, Engqvist M, Ibrahem I, Kaynak B, Córdova A. Angew. Chem. 2005;117:1367–1369. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:1343–1345. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Wang X, Meng Q, Perl NR, Xu Y, Leighton JL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:12806–12807. doi: 10.1021/ja053593s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.For selected recent preparations of similar products by non-iterative processes, see: Li DR, Murugan A, Falck JR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:46–48. doi: 10.1021/ja076802c. and references therein; Li F, Roush WR. Org. Lett. 2009;11:2932–2935. doi: 10.1021/ol9009877., and references therein.

- 7.a) Boxer MB, Yamamoto H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:48–49. doi: 10.1021/ja054725k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Boxer MB, Yamamoto H. Nat. Protoc. 2006;1:2434–2438. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.a) Boxer MB, Yamamoto H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:2762–2763. doi: 10.1021/ja0693542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Boxer MB, Yamamoto H. Org. Lett. 2008;10:453–455. doi: 10.1021/ol702825p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akakura M, Boxer MB, Yamamto H. ARKIVOC. 2007;10:337–347. [Google Scholar]

- 10.a) Brook MA, Gottardo C, Balduzzi S, Mohamed M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:6997–7000. [Google Scholar]; b) Brook MA, Balduzzi S, Mohamed M, Gottardo C. Tetrahedron. 1999;55:10027–10040. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kobayashi Y, Tan CH, Kishi Y. Helv. Chim. Acta. 2000;83:2562–2571. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoffmann SP, Kato T, Tham FS, Reed CA. Chem. Commun. 2006:767–769. doi: 10.1039/b511344j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]