Abstract

Fission yeast ste9/srw1 is a WD-repeat protein highly homologous to budding yeast Hct1/Cdh1 and Drosophila Fizzy-related that are involved in activating APC/C (anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome). We show that APCste9/srw1 specifically promotes the degradation of mitotic cyclins cdc13 and cig1 but not the S-phase cyclin cig2. APCste9/srw1 is not necessary for the proteolysis of cdc13 and cig1 that occurs at the metaphase–anaphase transition but it is absolutely required for their degradation in G1. Therefore, we propose that the main role of APCste9/srw1 is to promote degradation of mitotic cyclins when cells need to delay or arrest the cell cycle in G1. We also show that ste9/srw1 is negatively regulated by cdc2-dependent protein phosphorylation. In G1, when cdc2–cyclin kinase activity is low, unphosphorylated ste9/srw1 interacts with APC/C. In the rest of the cell cycle, phosphorylation of ste9/srw1 by cdc2–cyclin complexes both triggers proteolysis of ste9/srw1 and causes its dissociation from the APC/C. This mechanism provides a molecular switch to prevent inactivation of cdc2 in G2 and early mitosis and to allow its inactivation in G1.

Keywords: APC/C/cell cycle/cyclin/proteolysis/ste9/srw1

Introduction

Ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis plays an important role in the control of cell cycle progression. Targeted protein degradation is necessary for multiple processes in mitosis and at the G1–S transition (reviewed in Krek, 1998; Peters, 1998; Morgan, 1999; Zachariae and Nasmyth, 1999). Proteolysis of Cut2/Pds1, which triggers sister chromatid separation, is required for the metaphase–anaphase transition, and degradation of mitotic cyclins is essential to exit from mitosis (Glotzer et al., 1991; Holloway et al., 1993; Irniger et al., 1995; Cohen-Fix et al., 1996; Funabiki et al., 1996).

Ubiquitin is transferred to target substrates through several enzymatic reactions involving the E1, E2 and E3 enzymes. The ubiquitin ligase or E3 interacts with both the substrate and the E2 and determines the substrate specificity and the timing of degradation. Anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C) is the cell cycle-regulated ubiquitin ligase or E3 that mediates the degradation of Cut2/Pds1 and mitotic cyclins. APC/C is a multiprotein complex that it is activated at the metaphase–anaphase transition and remains active until late G1 (Amon et al., 1994; Brandeis and Hunt, 1996). APC/C activity and substrate specificity are regulated by its association with highly conserved regulatory activators that are part of the subfamilies of the WD40 repeat proteins, called Cdc20 and Hct1/Cdh1 in budding yeast (Schwab et al., 1997; Visintin et al., 1997), slp1 and ste9/srw1 in fission yeast (Yamaguchi et al., 1997; Kim et al., 1998; Kitamura et al., 1998), Fizzy and Fizzy-related in Drosophila and Xenopus (Dawson et al., 1995; Sigrist et al., 1995; Sigrist and Lehner, 1997; Lorca et al., 1998) and p55CDC/CDC20 and HCT1/CDH1 in humans (Weinstein et al., 1994; Fang et al., 1998; Kramer et al., 1998). The APCCdc20 (APCslp1 in fission yeast) complex promotes sister chromatid separation by ubiquitylating the anaphase inhibitor (or securin) Pds1 (cut2 in Schizosaccharomyces pombe) and by liberating the separin Esp1 (cut1 in S.pombe), which in turn causes either cleavage or modification of the cohesin subunit Scc1 (rad21 in S.pombe) (Michaelis et al., 1997; Ciosk et al., 1998; Uhlmann et al., 1999; see Yanagida, 2000 for a review). APCHct1/Cdh1 (APCste9/srw1 in S.pombe) triggers mitotic exit by targeting mitotic cyclins for destruction (Schwab et al., 1997; Sigrist and Lehner, 1997; Visintin et al., 1997; Yamaguchi et al, 1997; Kitamura et al., 1998; Kramer et al., 1998). Hct1 interaction with APC/C is negatively regulated by Cdk1–cyclin-dependent phosphorylation (Zacchariae et al., 1998; Jaspersen et al., 1999; Kramer et al., 2000) and activated by Cdc14 protein phosphatase (Visintin et al., 1998, 1999; Jaspersen et al., 1999; Shou et al., 1999). APCCdc20 activation controls not only Pds1 degradation but also that of Clb5 and Clb2 (Shirayama et al., 1999; Baümer et al., 2000; Yeong et al., 2000). Recently it has been proposed that degradation of the mitotic cyclin Clb2 occurs in two steps. First, a fraction of Clb2 is degraded by APCCdc20 at the metaphase–anaphase transition and later, in telophase, APCHct1/Cdh1 degrades the rest of Clb2 (Baümer et al., 2000; Yeong et al., 2000).

Fission yeast ste9/srw1 (ste9 from here on) has been proposed to be involved in the degradation of cdc13 B-type cyclin (Yamaguchi et al., 1997; Kitamura et al., 1998). Here we show that the main role of APCste9 is to target the mitotic cyclins cdc13 and cig1 for degradation in G1. ste9 interacts with APC/C only in G1. Cdk-dependent phosphorylation of ste9 in S-phase and G2 has a dual effect: it triggers the proteolysis of ste9 and also causes its dissociation from APC/C.

Results

cdc13 and cig1 cyclins are targets for APCste9

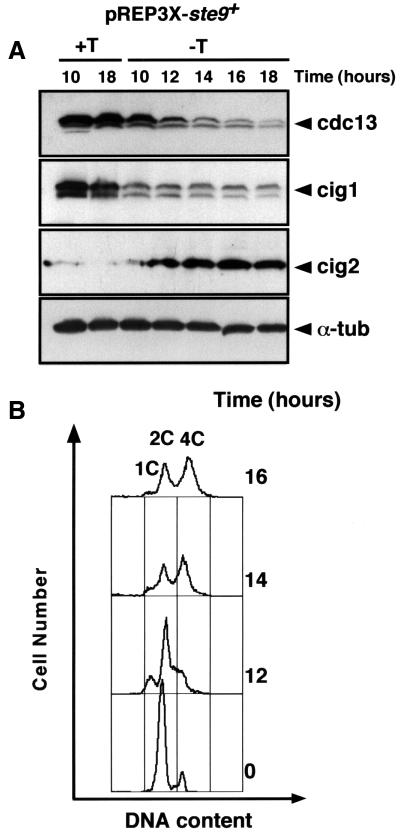

Previous studies have shown that overexpression of ste9 promotes cdc13 degradation and induces multiple rounds of S-phase in the absence of mitosis (Yamaguchi et al., 1997; Kitamura et al., 1998), equivalent to deletion of the cdc13+ gene (Hayles et al., 1994). To test whether ste9 induces degradation of other B-type cyclins in addition to cdc13, we overexpressed the ste9+ gene from the nmt1 promoter and measured the levels of cig1, cig2 and cdc13 cyclins in S.pombe. As shown in Figure 1A, ste9 overexpression promotes proteolysis of cdc13 and cig1 but not of cig2. In fact, cig2 levels increased in these cells in agreement with previous observations showing that down-regulation of cdc2/cdc13 allows accumulation of cig2 (Jallepalli and Kelly, 1996; C.Martín-Castellanos and S.Moreno, unpublished data). This result provides an explanation for the endoreplication phenotype induced by overproduction of the ste9+ gene (Yamaguchi et al., 1997; Kitamura et al., 1998; Figure 1B) as inactivation of cdc2/cdc13 will prevent mitosis while activation of cdc2/cig2 will trigger multiple rounds of S-phase.

Fig. 1. Overproduction of ste9+ promotes degradation of cdc13 and cig1 cyclins but not of cig2. An S.pombe leu1-32 strain was transformed with the plasmid pREP3X-ste9+. Transformants were selected on plates containing minimal medium with thiamine. Cells were grown in the presence (+T, repressed conditions) or absence of thiamine (–T, derepressed conditions) and samples were taken at the indicated times. (A) Extracts were prepared from these samples and the amounts of cdc13, cig1, cig2 and α-tubulin were determined. (B) FACS analysis of the cells.

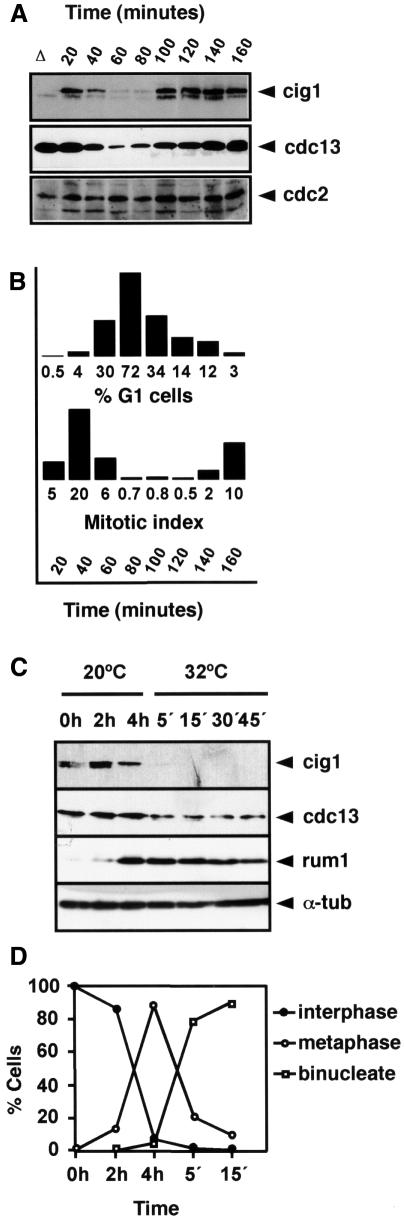

This experiment also suggests that cig1 cyclin is another target of APCste9. In contrast to cdc13 or cig2, analysis of the cig1 amino acid sequence reveals no obvious destruction box (Bueno et al., 1991) or KEN box (Pfleger and Kirschner, 2000). We examined cig1 protein levels during the mitotic cell cycle in cells synchronized by centrifugal elutriation and found that cig1 protein is destroyed in mitosis with similar kinetics to cdc13 (Figure 2A). For this experiment, we used the temperature-sensitive wee1-50 mutant where the G1 phase of the cell cycle is extended when incubated at the restrictive temperature of 36°C (Nurse, 1975). To confirm this result, we performed an additional experiment using the cold-sensitive nda3-KM311 β-tubulin mutants that arrest the cell cycle in metaphase. nda3-KM311 cells were pre-synchronized in early G2 by centrifugal elutriation. The resulting culture was incubated at the restrictive temperature of 20°C for 4 h and then released to 32°C. Samples were taken at 0, 2 and 4 h during the block and at 5, 15, 30 and 45 min during the release to measure cdc13, cig1 and rum1 protein levels. As shown in Figure 2C, cig1 was completely degraded during mitosis. Degradation of cig1 occurred slightly earlier than that of cdc13. Interestingly, in metaphase cells, cig1 levels started to decrease while cdc13 levels were still high (Figure 2C, t = 4 h); at this time point, the rum1 cdk inhibitor (a target for cdc2/cig1 phosphorylation) is already present at high levels (Figure 2C). This is consistent with previous observations indicating that cdc2/cig1 promotes phosphorylation and degradation of rum1 (Correa-Bordes et al., 1997; Benito et al., 1998). Taken together, these results indicate that cig1 cyclin is destroyed in mitosis and that cig1 may be an additional target of APCste9.

Fig. 2. Cig1 oscillates during the mitotic cell cycle. (A) Cig1 protein levels were measured in a synchronous culture of the temperature-sensitive wee1-50 strain. A homogeneous population of cells in early G2 was selected by centrifugal elutriation of the wee1-50 strain at 25°C. This culture was incubated for 20 min at 25°C and then shifted up to 36°C. Samples were taken every 20 min to determine cig1, cdc13 and cdc2 protein levels. Both cig1 and cdc13 protein levels decreased in anaphase and increased at the end of G1. A cig1 deletion (Δ) cell extract was used as a negative control. (B) Percentage of G1 cells and mitotic index of the synchronous culture. (C) Cig1 is degraded during mitosis. Early G2 cells of nda3-KM311 were isolated by centrifugal elutriation at 32°C and blocked in metaphase for 4 h at 20°C. The culture was then released at 32°C. Samples were taken at the indicated times to determine cig1, cdc13, rum1 and α-tubulin protein levels. (D) Percentage of cells in interphase, metaphase and anaphase determined by DAPI staining.

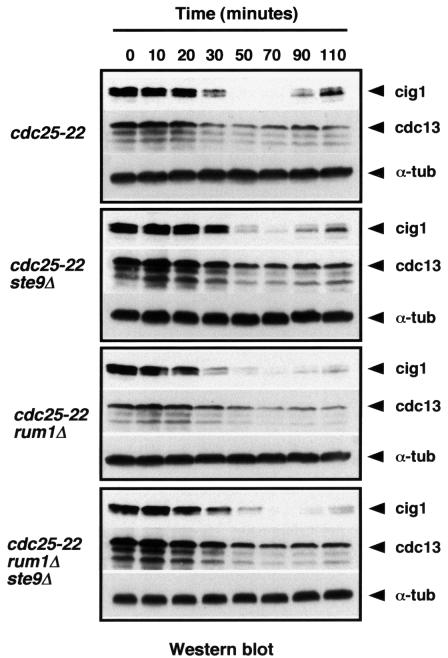

APCste9 is required for the degradation of mitotic cyclins in G1

Next, we wanted to test if ste9 was required in every cell cycle to degrade cdc13 and cig1 in mitosis, in G1 or both. In yeast, inactivation of cdc2–cyclin complexes in mitosis and G1 is thought to depend on two mechanisms: cyclin proteolysis by APC/C and cdk inhibition. Budding yeast cells lacking Hct1 and Sic1 are not viable, presumably because Cdc28/Clb2 cannot be down-regulated at the end of mitosis (Schwab et al., 1997). In contrast, fission yeast cells deleted for ste9 and rum1 are viable. We have found that the double mutant ste9Δ rum1Δ is wild-type in size and, like the single mutants ste9Δ and rum1Δ, is unable to arrest the cell cycle in G1 in response to nitrogen starvation and sterile (data not shown). We compared wild-type, ste9Δ, rum1Δ and ste9Δ rum1Δ cells synchronized in G2 using a cdc25-22 mutant and determined levels of cdc13 and cig1 protein as these cells proceeded through mitosis. As shown in Figure 3, degradation of cdc13 and cig1 took place with similar kinetics in wild-type, in the single mutants ste9Δ and rum1Δ and in the double mutant ste9Δ rum1Δ, suggesting that degradation of cdc13 and cig1 at the metaphase–anaphase transition can occur through a ste9-independent mechanism. However, ste9 is absolutely required for the degradation of cdc13 and cig1 in cells arrested in G1 using the cdc10-129 mutant (Kitamura et al., 1998; see Figure 7A, lanes 2–3 and 5–6). These experiments indicate that ste9 is not the only APC/C activator necessary for the proteolysis of mitotic cyclins as cells exit mitosis but it plays a fundamental role in G1. Perhaps APCslp1 contributes to the degradation of fission yeast mitotic cyclins during anaphase like in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, where APCCdc20 can also target Clb2 for degradation (Baümer et al., 2000; Yeong et al., 2000). We propose that the main role of APCste9 in fission yeast is to target mitotic cyclins for degradation in G1.

Fig. 3. Degradation of cdc13 and cig1 in mitosis does not require ste9 or rum1. Wild-type, ste9Δ, rum1Δ and ste9Δ rum1Δ cells were synchronized in G2 using the cdc25-22 mutant. After 4 h at 36°C, the cultures were release to 25°C and samples were taken to measure cig1, cdc13 and α-tubulin levels.

Fig. 7. ste9 associates with APC/C only in G1. (A) Extracts from cdc10-129, cdc10-129 cut9⋅HA ste9Δ and cdc10-129 cut9⋅HA mutants grown at 25 or 36°C were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibodies (IP α-HA) and then western blotted with anti-HA or anti-ste9 antibodies. Total cell extracts were separated on an SDS–polyacrylamide gel, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and probed with anti-HA, anti-ste9, anti-cdc13, anti-cig1 and anti-α-tubulin antibodies. (B) ste9 phosphorylation mutants associate with APC/C in G2. Extracts from cdc25-22, cdc25-22 cut9⋅HA and cdc10-129 cut9⋅HA mutants grown at 36°C for 4 h were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibodies (IP α-HA) and then western blotted with anti-HA and anti-ste9 antibodies. Total cell extracts were separated on an SDS–polyacrylamide gel, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and probed with anti-HA, anti-ste9 and anti-α-tubulin antibodies.

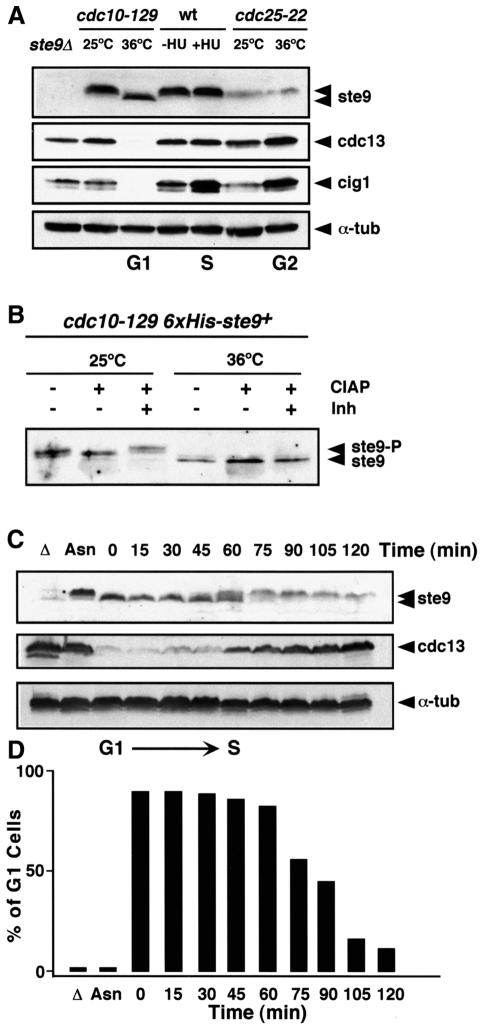

ste9 is regulated by protein phosphorylation

We raised specific antibodies to ste9 and measured ste9 protein levels in extracts of cells blocked at different points during the mitotic cell cycle. Extracts were made from cells blocked in G1 using the cdc10-129 mutant, in S-phase with the DNA synthesis inhibitor hydroxyurea (HU) and in G2 using the cdc25-22 mutant. We observed that ste9 migrated more rapidly in protein extracts from cells blocked in G1 (cdc10-129 at 36°C) than in S-phase (wt + HU) or G2 (cdc25-22 at 36°C) (Figure 4A). Treatment with alkaline phosphatase converted the upper bands into the lower band, indicating that ste9 is phosphorylated in vivo (Figure 4B). Phosphorylation of ste9 was then analysed in cells synchronized in G1 by blocking the cdc10-129 mutant during 4 h at 36°C and then releasing these cells to 25°C. ste9 was completely dephosphorylated in G1 (Figure 4C, t = 0) and became phosphorylated ∼60 min after the release as cells were undergoing S-phase (Figure 4C and D). Cdc13 cyclin, one of the targets of APCste9, began to accumulate in these cells at the time when ste9 became phosphorylated. These experiments suggest that, similarly to Hct1/Cdh1 in S.cerevisiae, ste9 is negatively regulated during S-phase and G2 by phosphorylation.

Fig. 4. ste9 is phosphorylated in S-phase and G2 but not in G1. (A) ste9, cdc13 and cig1 protein levels in cells arrested in G1 with the cdc10-129 mutant, in S-phase with hydroxyurea and in G2 with the cdc25-22 mutant. As a negative control, we used an extract prepared from the ste9Δ mutant and α-tubulin as loading control. (B) A His6-ste9 allele introduced by gene replacement into the ste9 locus was purified on an Ni2+-NTA column from cdc10-129 cells growing at 25°C or after 4 h at 36°C. The purified His6-ste9 was treated with calf intestine alkaline phosphatase (CIAP) in the absence (–) or presence (+) of phosphatase inhibitors (Inh). (C) ste9 phosphorylation occurs at the G1–S transition. A cdc10-129 culture grown at 25°C to mid-exponential phase in minimal medium was shifted to 36°C for 4 h and then released at 25°C. Samples for western blot and flow cytometry were taken before the shift to 36°C (Asn), 4 h after the shift to 36°C (t = 0 min) and every 15 min after the release to 25°C. The levels of ste9, cdc13 and α-tubulin were determined. ste9 was unphosphorylated at the block point (t = 0 min) and became phosphorylated at the onset of S-phase (t = 60 min). Cdc13 protein levels were low in G1 cells while ste9 was unphosphorylated and started to accumulate when ste9 became phosphorylated and the cells initiated S-phase. Δ is a negative control from ste9Δ and Asn is an extract from the asynchronous culture of cdc10-129 at 25°C. (D) Percentage of cells in G1 during the course of the experiment.

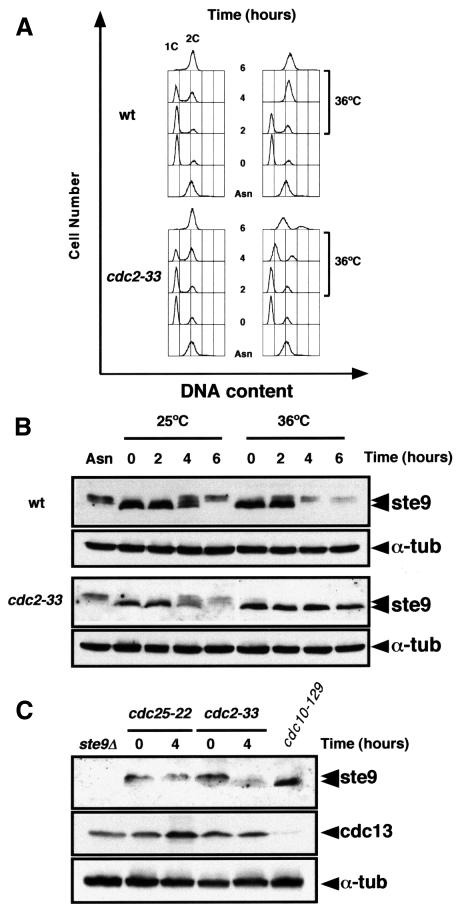

Cdc2–cyclin phosphorylates ste9 at multiple sites

ste9 phosphorylation occurs in S-phase and G2 when the cdc2–cyclin kinase activity is high. In order to study whether ste9 phosphorylation is dependent on cdc2–cyclin activity, we synchronized the wild-type and the cdc2-33 mutant in G1 by nitrogen starvation at 25°C for 12 h. Nitrogen was then added back and the cultures were divided into two. Half of the cells were incubated at the permissive temperature (25°C) and the other half at the restrictive temperature (36°C) for the cdc2ts mutant. Wild-type and cdc2-33 cells incubated at 25°C underwent S-phase ∼4 h after the addition of nitrogen (Figure 5A). At 36°C, wild-type cells completed S-phase after 4 h whereas the cdc2-33 mutant remained in G1 for up to 6 h (Figure 5A). As shown in Figure 5B, ste9 phosphorylation in the cdc2-33 mutant was detected after 4 h at 25°C but not at 36°C, suggesting that phosphorylation of ste9 is dependent on the activation of cdc2–cyclin kinase at G1/S. We also observed that ste9 protein levels decreased at least 4-fold as it became phosphorylated (Figure 5B); expression of the ste9+ gene is constant under this experimental condition (data not shown), suggesting that phosphorylation of ste9 reduces its stability. We consistently found a reduction in ste9 protein levels in G2 cells compared with cells in G1 (see also Figure 4A, compare levels in cdc25ts with levels in cdc10ts).

Fig. 5. ste9 phosphorylation depends on cdc2 function. Wild-type and cdc2-33 cells were nitrogen starved for 12 h at 25°C. NH4Cl was added to the culture and half of the cells were incubated at 25°C and the rest at 36°C. Samples were taken for flow cytometry (A) and for western blots (B) at 0, 2, 4 and 6 h after the addition of NH4Cl to determine ste9 and α-tubulin protein levels. Asn corresponds to a sample taken from the asynchronous culture before nitrogen starvation. (C) ste9 mobility in cdc25-22 and cdc2-33 extracts prepared from cells growing exponentially at 25°C (t = 0) and then shifted to 36°C for 4 h (t = 4). The levels of cdc13, cdc2 and α-tubulin in these extracts are also shown. As a control, we used an extract from cdc10-129 cells incubated at 36°C for 4 h.

To confirm that phosphorylation of ste9 depends on cdc2 kinase activity, we performed an additional experiment. cdc2-33 and cdc25-22 mutant cells growing at 25°C were shifted to 36°C and samples were taken at 0, 2 and 4 h after the shift. ste9 became dephosphorylated in cdc2-33 cells incubated at the restrictive temperature but not in cdc25-22 cells (Figure 5C), indicating that active cdc2 kinase is needed to maintain ste9 in its phosphorylated form.

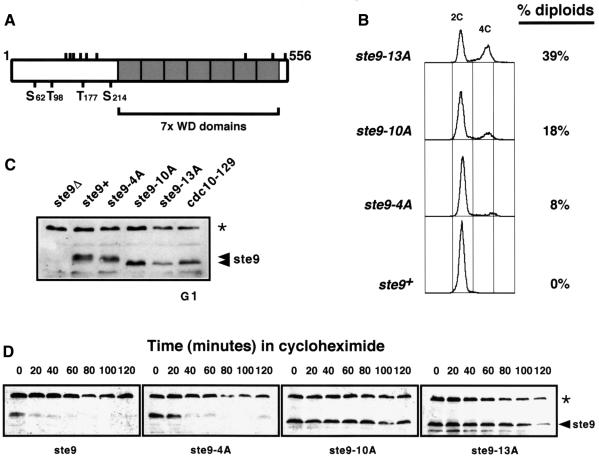

Examination of the ste9 amino acid sequence revealed the presence of four putative cdc2 phosphorylation sites (S62, T98, T177 and S214) with the consensus S/T-P-X-K/R (where X represents any amino acid). There are nine additional sites (S130, T134, T143, T159, T174, S187, S425, S513 and S547) with the sequence S/T-P of which six are located at the N-terminus and three at the C-terminus of the protein within the seven WD repeats (Figure 6A). We generated three mutant alleles of ste9+ by site-directed in vitro mutagenesis where these putative phosphorylation sites were mutated to alanine. ste9-4A contained the four putative phosphorylation sites with the strict consensus sequence, ste9-10A contained in addition the six S/T-P sites at the N-terminus and ste9-13A has all the sites mutated to alanine. The three mutant alleles were introduced into the ste9+ locus by gene replacement. Expression of these mutant forms of ste9 were able to rescue fully the sterility defect of ste9-deleted cells (data not shown). Cells expressing ste9-10A and ste9-13A were elongated compared with wild-type cells and, when they were streaked onto YES plates containing phloxin B, many dark red colonies were observed, suggesting that these cells were undergoing diploidization at high frequency. To confirm this observation, we measured the DNA content of these cells by flow cytometry and found that 8% of the cells were diploids in ste9-4A, 18% in ste9-10A and 38% in ste9-13A (Figure 6B). There was a direct correlation between the number of phosphorylatable residues mutated to alanine and the ability of the ste9 mutants to induce diploidization. This result indicates that cdk phosphorylation of ste9 is important to down-regulate ste9 in S-phase and G2. If ste9 is not phosphorylated in G2, it can promote cdc13 degradation and, as a consequence, the cells endoreduplicate their DNA. We have also found that the electrophoretic mobility of ste9-10A and ste9-13A was similar to that of unphosphorylated ste9 from cells arrested in G1 with cdc10-129 at 36°C (Figure 6C). Thus, ste9 is phosphorylated at multiple sites in vivo and this phosphorylation results in its inactivation.

Fig. 6. Expression of ste9 phosphorylation mutants induces diploidization. Three mutants, ste9-4A, ste9-10A and ste9-13A, containing four, 10 and the 13 putative cdk phosphorylation sites were mutated to alanine by site-directed in vitro mutagenesis. These mutant alleles were introduced into the fission yeast genome by gene replacement. (A) Schematic representation of the ste9 protein with the seven WD repeats and the position of the 13 putative cdk phosphorylation sites. (B) FACS profile of cells replaced with the different ste9 mutant alleles. (C) Electrophoretic mobility of the different ste9 alleles. The asterisk corresponds to a non-specific band recognized by the anti-ste9 antibody that it is also detected in ste9Δ. (D) Half-lives of ste9, ste9-4A, ste9-10A and ste9-13A in exponentially growing cultures after the addition of 100 µg/ml of cycloheximide. The asterisk corresponds to a non-specific band recognized by the anti-ste9 antibody that it is also detected in ste9Δ and serves as loading control.

As shown in Figure 5B, phosphorylation of ste9 by cdc2–cyclin complexes correlates with a significant decrease in ste9 protein levels. To investigate the possibility that cdc2 phosphorylation regulates ste9 stability, we compared the half-life of wild-type ste9 with that of ste9-4A, ste9-10A and ste9-13A mutant proteins. Cultures of wild-type and the three mutant strains generated by gene replacement with the ste9 mutant alleles were grown to mid-exponential phase and the half-lives of ste9, ste9-4A, ste9-10A and ste9-13A were measured after the addition of the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide. Figure 6D shows that ste9 is short-lived (half-life <10 min) under these conditions. The half-lives of the mutant proteins increased considerably, particularly in the case of the ste9-10A mutant (half-life >120 min) (Figure 6D). This result confirms that ste9 protein levels are down-regulated in vivo by cdc2-dependent phosphorylation.

ste9 phosphorylation prevents its interaction with APC/C

Previous reports have shown that cdk phosphorylation of Hct1/Cdh1 in budding yeast and animal cells prevents its association with APC/C (Zacchariae et al., 1998; Jaspersen et al., 1999; Lukas et al., 1999; Kramer et al., 2000). To test whether ste9 associates with APC/C, we used a strain where one of the APC/C subunits cut9 was epitope tagged with three copies of haemagglutinin (HA) (Berry et al., 1999). ste9 co-precipited with cut9-HA in extracts prepared from cells arrested in G1 with the cdc10-129 mutant (Figure 7A and B, lanes 6). In contrast, ste9 was not associated with APC/C in extracts from cells arrested in G2 with the cdc25-22 mutant (Figure 7B, lane 3). Thus ste9 interacts with APC/C only in G1 when it is not phosphorylated and it does not interact with APC/C in G2 when it becomes phosphorylated. We then analysed whether the mutant proteins ste9-10A and ste9-13A were able to interact with APC/C in G2 as this may be the reason for the diploidization phenotype observed in these mutants. To test this, we prepared extracts from cells arrested in G2 with the cdc25-22 mutant and then immunoprecipitated APC/C using anti-HA antibodies. ste9 co-precipitated with APC/C in extracts expressing ste9-10A and ste9-13A but not in extracts expressing wild-type ste9+ (Figure 7B, lanes 3–5), suggesting that phosphorylation of ste9 causes its dissociation from APC/C in G2.

Discussion

In this study, we provide biochemical evidence for a role for ste9 as a negative regulator of cell cycle progression in G1. ste9 is a member of a highly conserved family of proteins containing seven WD repeat domains of which the prototypes are Hct1/Cdh1 of budding yeast and Fizzy-related of higher eukaryotes (Schwab et al., 1997; Sigrist and Lehner, 1997; Visintin et al., 1997; Kramer et al., 1998). These proteins function as activators of APC/C to promote polyubiquitylation and degradation of mitotic cyclins in mitosis and G1. Here we show that in fission yeast: (i) APCste9 promotes degradation of the mitotic cyclins cdc13 and cig1 but not of the S-phase cyclin cig2. The fact that cig2 levels are high in cells overexpressing ste9 provides an explanation for the re-replication phenotype associated with these cells. (ii) APCste9 is not necessary for the proteolysis of mitotic cyclins at the end of mitosis because in cells lacking ste9, degradation of cdc13 and cig1 still occurs. However, ste9 is absolutely required to degrade mitotic cyclins completely when cells need to delay or to stop the cell cycle in G1. This is important for small cells that had to lengthen the G1-phase until they reach the minimum cell size required to initiate DNA replication or to prevent entry into mitosis from G1. (iii) ste9 is phosphorylated by the cdc2 kinase in vivo at multiple sites. Cdk phosphorylation of ste9 in G2 has two effects. First, to promote the degradation of ste9 and secondly, to prevent ste9 association with APC/C. APC/C–ste9 interaction occurs only in G1 when ste9 is in its dephosphorylated form. In S-phase and G2, ste9 becomes phosphorylated and it does not interact with APC/C.

Two APC complexes are involved in the degradation of mitotic cyclins

We have found that cdc13 and cig1 are targets for APCste9 in G1. Two observations support this idea: first cdc13 and cig1 protein levels decrease when ste9 is overproduced. In addition, cig1 and cdc13 are not degraded when a cdc10-129 ste9Δ mutant is incubated at the restrictive temperature. The fact that both cyclins are destroyed during mitosis in cells lacking ste9 suggests that another APC complex is responsible for the degradation of cig1 and cdc13 at the metaphase–anaphase transition. Perhaps slp1, the fission yeast homologue of Cdc20, in association with APC/C may trigger the degradation of cig1 and cdc13 as cells exit mitosis. This is reminiscent of the situation in budding yeast where proteolysis of Clb2 by the APC/C occurs in two stages. First, a fraction of Clb2 is destroyed during anaphase by APCCdc20 and the rest is degraded at the end of mitosis by APCHct1 (Baümer et al., 2000; Yeong et al., 2000). It is interesting to note that cig1 does not have a clear destruction box sequence as is the case with cdc13, nor does it have a KEN box (Pfleger and Kirschner, 2000). However, cig1 is destroyed in mitosis a bit earlier than cdc13. Future experiments will address the existence of a non-canonical destruction box in cig1.

Inhibition of Cdk–cyclin B in G1 and cell differentiation

In fission yeast, down-regulation of cdk activity is important for the G1 arrest upon nitrogen starvation or after treatment with mating pheromone (Moreno and Nurse, 1994; Stern and Nurse, 1997; Yamaguchi et al., 1997; Kitamura et al., 1998). APCste9 and rum1 play a pivotal role in decreasing levels and activities of the cdc2–cdc13 complex during G1 below a threshold level, which allows cells to initiate the differentiation programmes such as mating or meiosis. Therefore, APCste9 and rum1 provide the molecular switch between cell proliferation and cell differentiation (Yamaguchi et al., 1997; Kitamura et al., 1998; Stern and Nurse, 1998). We have observed an increase in rum1+ and ste9+ mRNA and protein levels in cells that exit the mitotic cell cycle because of nutrient limitation (Martín-Castellanos et al., 2000; M.A.Blanco and S.Moreno, unpublished results). There are a number of reports in the literature suggesting that mitotic cyclins need to be kept under tight control in differentiating cells. For example, fission yeast cells lacking rum1 or ste9 are unable to undergo cell differentiation (Moreno and Nurse, 1994; Yamaguchi et al., 1997; Kitamura et al., 1998; Stern and Nurse, 1998). In budding yeast, hct1 mutants are resistant to mating pheromone, suggesting that APCHct1 is important for the mating response (Schwab et al., 1997). Drosophila fizzy-related (fzr) is expressed and required at specific stages of embryogenesis when cells stop proliferating (Sigrist and Lehner, 1997). In animal cells, HCT1/CDH1 is highly expressed in tissues composed predominantly of differentiated cells, such as adult brain where APCHct1/Cdh1 is very active (Gieffers et al., 1999). In the plant Medicago sativa, expression of the ste9 homologue ccs52 is turned on when nodule primordium differentiates and for the formation of large differentiated cells that polyploidize (Cebolla et al., 1999). This is consistent with results in Drosophila and fission yeast where down-regulation of mitotic cyclins caused by high levels of fzr or ste9+ expression induces endoreduplication (Sigrist and Lehner, 1997; Yamaguchi et al., 1997; Kitamura et al., 1998; Figure 1B). All these findings suggest that mitotic cyclins need to be destroyed in G1 to allow cell differentiation, and abnormal degradation of mitotic cyclins in G2 will lead to re-replication.

Phosphorylation of ste9 promotes its proteolysis and dissociation from APC/C

ste9 is phosphorylated in all phases of the cell cycle except in G1. Low Cdk–cyclin activity in G1 is generated by the combined effects of cyclin proteolysis (through APCste9) and cdk inhibition (through rum1). Cdc2–cyclin complexes negatively regulate both ste9 and rum1 (Benito et al., 1998 and this study). In early G1, ste9 and rum1 are dephosphorylated and active. As the cell grows during G1, cig1, cig2 and cdc13 cyclins begin to accumulate. Cdk activity eventually predominates during S-phase resulting in the phosphorylation of both ste9 and rum1. Phos- phorylation of ste9 causes its dissociation from APC/C and also affects its stability. In S.cerevisiae and animal cells, it has been reported that Hct1/Cdh1 is a very stable protein and phosphorylation of Hct1/Cdh1 only affects its association with APC/C (Kramer et al., 1998; Prinz et al., 1998; Zacchariae et al., 1998; Jaspersen et al., 1999; Lukas et al., 1999). This is based on experiments showing that Hct1/Cdh1 protein levels do not change throughout the cell cycle. However, no half-life experiments using wild-type levels of Hct1 and mutant proteins expressed under its own promoter, like that described in Figure 6D, has been performed. In fission yeast, we find that ste9 is an unstable protein. ste9 protein levels decrease in G2, specially in cells re-entering the mitotic cell cycle from starvation conditions (Figure 5B). We have observed an increase in ste9+ mRNA and protein levels in cells arrested in G1 after nitrogen starvation (M.A.Blanco and S.Moreno, unpublished data). This might provide a mechanism to supply plenty of ste9 protein in cells that arrest the cell cycle in G1 because of nutrient limitation and to reduce the ste9 protein levels in proliferating cells.

A mutant strain expressing a ste9 allele where 10 putative Cdk phosphorylation sites were mutated to alanine (ste9-10A) showed a very clear gain-of-function phenotype. This mutant protein is very stable and associates with APC/C in G2. These cells showed a high frequency of diploidization. This phenotype could be explained if unregulated association of the mutant protein with APC/C in G2 reduces the level of the cdc2/cdc13 activity below a certain threshold level required to prevent initiation of another round of S-phase within the same cell cycle (Hayles et al., 1994). Thus, the APCste9 complex, which normally is present only in G1, could induce extra rounds of S-phase when present in S-phase or G2.

Cdc2–cyclin complexes and their inhibitors (rum1 and APC/C) antagonize each other’s activity during the cell cycle. Phosphorylation of ste9 and rum1 at G1/S by cdc2–cyclin provides a molecular switch to prevent inactivation of cdc2 during S-phase and early mitosis. A key unresolved issue in fission yeast cell cycle research is which is the protein phosphatase that reactivates ste9 and rum1 during mitosis. Very recently, a fission yeast protein with significant homology to budding yeast Cdc14 has been deposited in the fission yeast sequencing project (A.Bueno and V.Simanis, personal communication). Functional analysis of this protein will be necessary in order to determine its role at the metaphase–anaphase transition or in cell cycle exit.

Materials and methods

Fission yeast strains and methods

The S.pombe strains used in this study are listed in Table I. Growth conditions and strain manipulations were as described by Moreno et al. (1991). The h+ cut9::cut9-HA/Kanr strain was described by Berry et al. (1999). The srw1/ste9Δ::ura4+ ura4d18 leu1-32 h– strain was described by Yamaguchi et al. (1997), and involves deletion of the entire open reading frame. Since deletion of ste9+ causes sterility, all the crosses involving a deletion of ste9+ were done by transforming with pREP3X-ste9+, so that ste9+ is expressed from a plasmid, and the double mutants were checked subsequently to ensure that the plasmid had been lost. Protoplast fusion and tetrad analysis was performed to construct double rum1Δ ste9Δ mutants, and the identity of these mutants was confirmed by Southern blotting. Yeast transformation was carried out using the lithium acetate transformation protocol (Norbury and Moreno, 1997).

Table I. Schizosaccharomyces pombe strains.

| Strain | Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| PN1 | 972 h– | P.Nurse |

| PN22 | leu1-32 h– | P.Nurse |

| PN7 | cdc25-22 h– | P.Nurse |

| PN8 | cdc2-33 h– | P.Nurse |

| S391 | wee1-50 cig2-HA h– | S.Moreno |

| S18 | nda3-KM311 leu1-32 h+ | S.Moreno |

| S683 | cig2HA leu1-32 h+ | S.Moreno |

| S627 | ste9Δ::ura4+ leu1-32 ura4d18 h– | H.Okayama |

| S10 | cdc25-22 leu1-32 h– | P.Nurse |

| S11 | cdc10-129 leu1-32 h– | P.Nurse |

| S868 | cdc25-22 rum1Δ::ura4+ leu1-32 ura4d18 | this study |

| S869 | cdc25-22 ste9Δ::ura4+ leu1-32 ura4d18 h– | this study |

| S870 | cdc25-22 ste9Δ::ura4+ rum1Δ::ura4 leu1-32 ura4d18 | this study |

| S871 | cdc10-129 ste9::His6-ste9 leu1-32 ura4d8 h– | this study |

| S872 | ste9::ste9-4A leu1-32 ura4d18 h– | this study |

| S873 | ste9::ste9-10A leu1-32 ura4-d18 h– | this study |

| S874 | ste9::ste9-13A leu1-32 ura4-d18 h– | this study |

| KGY1365 | cut9::cut9-HA/Kanr h+ | K.Gould |

| S875 | cdc10-129 cut9::cut9-HA/Kanr leu1-32 ura4d18 | this study |

| S876 | cdc10-129 cut9::cut9-HA/Kanr ste9Δ::ura4+ leu1-32 ura4d18 | this study |

| S877 | cdc25-22 cut9::cut9-HA/Kanr leu1-32 ura4d18 | this study |

| S878 | cdc25-22 cut9::cut9-HA/Kanr ste9Δ::ura4+ leu1-32 ura4d18 | this study |

| S879 | cdc25-22 cut9::cut9-HA/Kanr ste9::ste9-10A leu1-32 ura4d18 | this study |

| S880 | cdc25-22 cut9::cut9-HA/Kanr ste9::ste9-13A leu1-32 ura4d18 | this study |

All experiments in liquid culture were carried out in essential minimal medium (EMM) containing the required supplements, starting with a cell density of 2–4 × 106 cells/ml, corresponding to mid-exponential phase growth. Temperature shift experiments were carried out using a water bath at 36.5°C.

To induce expression from the nmt1 promoter, cells were grown to mid-exponential phase in EMM containing 5 µg/ml thiamine, then spun down and washed four times with minimal medium lacking thiamine at a density calculated to produce 4 × 106 cells/ml at the time of peak expression from the nmt1 promoter.

Synchronous cultures

wee1-50 h– cells were grown at 25°C in EMM. Cells were synchronized at 25°C using a JE-5.0 elutriation system (Beckman Instruments, Inc.) and then shifted to 36°C, resulting in entry into mitosis at a reduced cell size. Samples were taken every 20 min for making protein extracts and for flow cytometry analysis.

ste9 phosphorylation site mutants

A 4.6 kb genomic fragment containing the ste9+ gene was cloned into pTZ18R. This plasmid was used to obtain the different ste9 mutants by site-directed mutagenesis using the Muta-gene phagemid in vitro mutagenesis kit (Bio-Rad).

All three mutants, pTZ18R-ste9-4A (S62, T98, T177 and S214), pTZ18R-ste9-10A (S62, T98, S130, T134, T143, T159, T174, T177, T187 and S214) and pTZ18R-ste9-13A (S62, T98, S130, T134, T143, T159, T174, T177, T187, S214, S425, S513 and S547) were sequenced after the mutagenesis. The 4.6 kb genomic fragments containing these mutations were then transformed into a ste9Δ::ura4+ ura4d18 strain, and 5-fluoro-orotic acid (5-FOA) was used to select ura– colonies (Boeke et al., 1984). PCR analysis and Southern blotting of DNA isolated from these colonies confirmed that the ste9Δ::ura4+ locus had been replaced specifically with ste9 mutant alleles by homologous recombination. To make the constructions in pREP3X and pREP81X, the coding region of ste9+ was amplified by PCR using the Expand High Fidelity PCR System (Roche) and sense (TGAAGTCAGGGATCCTAACG) and antisense (GAGTGAATGGGATCCATTAC) oligonucleotide primers. To facilitate cloning, BamHI sites (underlined sequence) were introduced upstream of the initiation codon and downstream of the termination codon. The 1.67 kb PCR products were digested with BamHI and subcloned into pREP3X and pREP81X vectors.

His6 tagging of ste9

pTZ18R-ste9+ plasmid containing the 4.6 kb genomic fragment was used to introduce a His6 tag just after the initiation codon by site-directed mutagenesis using the Muta-gene phagemid in vitro mutagenesis kit (Bio-Rad) and the oligonucleotide 5′-GGGCCTAACGTGAAATTATGC ATCACCATCACCATCACGAATTTGATGGGTTTACTAG-3′ (where the initiation codon and His6-encoding codons are underlined). The 4.6 kb genomic fragment containing His6-ste9 was then transformed into a ste9Δ::ura4+ ura4d18 strain, and 5-FOA used to select ura– colonies (Boeke et al., 1984). Southern blotting, PCR analysis of DNA isolated from these colonies and sequencing of the PCR products confirmed that the ste9Δ::ura4+ locus had been replaced specifically with the His6-ste9 allele by homologous recombination. In order to demonstrate that His6-ste9 is functional, we checked the ability of the His6-ste9 strain to conjugate and sporulate. Whilst ste9Δ cells are sterile, His6-ste9 cells are fertile to the same extent as the wild-type.

Preparation of rabbit polyclonal antibodies against ste9

A peptide spanning the C-terminal 14 residues of ste9 (CSTMSS PFDPTMKIR) was coupled to keyhole limpet haemocyanin (KLH) and injected into a rabbit with Freund’s adjuvant followed by standard procedures for raising polyclonal antibodies (Harlow and Lane, 1988).

Preparation of rabbit polyclonal antibodies against Cig1

A 471 bp DNA fragment encoding the first 157 residues of cig1 protein was subcloned into pGEX-KG (Pharmacia). The GST–cig1-157N fusion protein was produced in Escherichia coli, purified with glutathione–Sepharose 4B (Pharmacia Biotech) and used to raise anti-cig1 polyclonal antibodies as indicated above.

Protein extracts and western blots

Total protein extracts were prepared from 3×108 cells collected by centrifugation, washed in Stop buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM NaF, 10 mM EDTA, 1 mM NaN3 pH 8.0) and resuspended in 25 µl of RIPA buffer (10 mM sodium phosphate, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, 10 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl pH 7.0) containing the following protease inhibitors, 10 µg/ml leupeptin, 10 µg/ml aprotinin, 10 µg/ml pepstatin, 10 µg/ml soybean trypsin inhibitor, 100 µM 1-chloro-3-tosylamido-7-amino-l-2-heptanone (TLCK), 100 µM N-tosyl-l-phenyalanine chloromethyl ketone (TPCK), 100 µM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 1 mM phenanthroline and 100 µM N-acetyl-leu-leu-norleucinal. Cells were boiled for 5 min, broken using 750 mg of glass beads (0.4 mm Sigma) for 15 s in a Fast-Prep machine (Bio101 Inc.), and the crude extract was recovered by washing with 0.5 ml of RIPA buffer. Protein concentration was determined by the BCA protein assay kit (Pierce).

For western blots, 50 µg of total protein extract was run on a 10% SDS–polyacrylamide gel, transfered to nitrocellulose and probed with rabbit affinity-purified anti-ste9-C-terminus (1:200), SP4 anti-cdc13 (1:250) or anti-cig1 (1:250) polyclonal antibodies, or with the monoclonal anti-HA antibody 12CA5 (0.15 µg/ml). Goat anti-rabbit or goat anti-mouse antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP; Amersham) (1:3500) was used as secondary antibody. Mouse TAT1 anti-tubulin monoclonal antibodies (1:500) and HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody (1:2000) as secondary antibody were used to detect tubulin as loading control. Immunoblots were developed using the ECL kit (Amersham) or Super Signal (Pierce).

Alkaline phosphatase treatment

His6-ste9 protein was purified from total protein extracts as described by Shiozaki and Russell (1997). Briefly, 3 × 108 cells were lysed in 6 M guanidine hydrochloride, 0.1 M sodium phosphate, 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0. The lysate was clarified by centrifugation for 10 min at room temperature, and the supernatant was mixed with Ni2+-NTA–agarose (Qiagen) and incubated in a rotating wheel for 60 min at room temperature. The Ni2+-NTA–agarose beads were washed with an 8–0.5 M urea reverse gradient in 0.1 M sodium phosphate, 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0. After washing twice with alkaline phosphatase buffer (5 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 0.5 mM MgCl2), beads were incubated with 50 U of alkaline phosphatase (Roche) for 30 min at 37°C in the presence or absence of phosphatase inhibitors. The final concentrations of phosphatase inhibitors were 1 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 5 mM EDTA and 0.1 mM orthovanadate. The reactions were stopped by boiling for 3 min after the addition of 2× SDS sample buffer, and samples were run on a 10% SDS–polyacrylamide gel, followed by western blot analysis.

Co-immunoprecipitation of ste9 and cut9-HA

Total protein extracts were prepared from 3×108 cells using HB buffer (Moreno et al., 1991). Cell extracts were spun at 4°C in a microcentrifuge for 15 min, and the protein concentration was determined by the BCA protein assay kit (Pierce). A 3 mg aliquot of total protein extracts was subjected to immunoprecipitation by consecutive incubation with the monoclonal anti-HA 12CA5 (2 µg) for 1 h in ice and protein A–Sepharose (Phrmacia-Biotech) for 30 min at 4°C in a rotating wheel. Immunoprecipitates were washed six times with 1 ml of HB buffer. Lysates and immunoprecipitates were separated on a 10% SDS–polyacrylamide gel, followed by western blot analysis as above.

Flow cytometry and microscopy

About 107 cells were spun down, washed once with water, fixed in 70% ethanol and processed for flow cytometry or 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining, as described previously (Sazer and Sherwood, 1990; Moreno et al., 1991). A Becton-Dickinson FACScan was used for flow cytometry. To estimate the proportion of G1 cells, we determined the percentage of cells with a DNA content less than a value midway between 1C and 2C. The mitotic index was determined by counting the percentage of anaphase cells (cells with two nuclei and without a septum) after DAPI staining.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

M.A.B. dedicates this paper to his grandfather for his continuous support. We would like to thank Kathy Gould and Hiroto Okayama for the cut9-HA and the srw1/ste9 deletion strains, Susana R.Echeverría and Jaime Correa for their help in the experiment showed in Figure 2C, and Laetitia Pelloquin and Viesturs Simanis for valuable comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by funding from the Comision Interministerial de Ciencia y Tecnología (CICYT) and the European Union.

References

- Amon A., Irniger,S. and Nasmyth,K. (1994) Closing the cell cycle circle in yeast: G2 cyclin proteolysis initiated at mitosis persits until the activation of G1 cyclins in the next cycle. Cell, 77, 1037–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baümer M., Braus,G.H. and Irniger,S. (2000) Two different modes of cyclin Clb2 proteolysis during mitosis in Saccharomyces cerevisae. FEBS Lett., 468, 142–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benito J., Martín-Castellanos,C. and Moreno,S. (1998) Regulation of the G1 phase of the cell cycle by periodic stabilization and degradation of the p25rum1 Cdk inhibitor. EMBO J., 17, 482–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry L.D., Feoktistova,A., Wright,M.D. and Gould,K.L. (1999) The Schizosaccharomyces pombe dim1+ gene interacts with the anaphase-promoting complex or cyclosome (APC/C) component lid1+ and is required for APC/C function. Mol. Cell Biol., 19, 2535–2546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeke J.D., LaCroute,F. and Fink,G.R. (1984) A positive selection for mutants lacking orotidine-5′-phosphate decarboxylase activity in yeast: 5-fluoro-orotic acid resistance. Mol. Gen. Genet., 197, 345–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandeis M. and Hunt,T. (1996) The proteolysis of mitotic cyclins in mammalian cells persists from the end of mitosis until the onset of S-phase. EMBO J., 15, 5280–5289. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bueno A., Richardson,H., Reed,S.I. and Russell,P. (1991) A fission yeast B-type cyclin functioning early in the cell cycle. Cell, 66, 149–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cebolla A., Vinardell,J.M., Kiss,E., Olah,B., Roudier,B., Kondorosi,A. and Kondorosi,E. (1999) The mitotic inhibitor ccs52 is required for endoreduplication and ploidy-dependent cell enlargement in plants. EMBO J., 18, 4476–4484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciosk R., Zacchariae,W., Michaelis,C., Shevchenko,A., Mann,M. and Nasmyth,K. (1998) An Esp1/Pds1 complex regulates loss of sister chromatid cohesion at the metaphase to anaphase transition in yeast. Cell, 93, 1067–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Fix O., Peters,J.-M., Kirschner,M.W. and Koshland,D. (1996) Anaphase initiation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is controlled by the APC-dependent degradation of the anaphase inhibitor Pds1p. Genes Dev., 10, 3081–3093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correa-Bordes J., Gulli,M.P. and Nurse,P. (1997) p25rum1 promotes proteolysis of the mitotic B-cyclin p56cdc13 during G1 of the fission yeast cell cycle. EMBO J., 16, 4657–4664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson I.A., Roth,S. and Artavanis,T.S. (1995) The Drosophila cell cycle gene Fizzy is required for normal degradation of cyclins A and B during mitosis and has homology to the CDC20 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Biol., 129, 725–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang G., Yu,H. and Kirschner,M.W. (1998) The checkpoint protein Mad2 and the mitotic regulator Cdc20 form a ternary complex with the anaphase promoting complex to control anaphase initiation. Genes Dev., 12, 1871–1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funabiki H., Yamano,H., Kumada,K., Nagao,K., Hunt,T. and Yanagida,M. (1996) Cut2 proteolysis required for sister-chromatid separation in fission yeast. Nature, 381, 438–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gieffers C., Peters,B.H., Kramer,E.R., Dotti,C.G. and Peters,J.M. (1999) Expression of the Cdh1 associated form of the anaphase promoting complex in postmitotic neurons. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 11317–11322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glotzer M., Murray,A.W. and Kirschner,M.W. (1991) Cyclin is degraded by the ubiquitin pathway. Nature, 349, 132–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlow E. and Lane,D. (1988) Antibodies: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Hayles J., Fisher,D., Woollard,A. and Nurse,P. (1994) Temporal order of S-phase and mitosis in fission yeast is determined by the state of the p34cdc2/mitotic B cyclin complex. Cell, 78, 813–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloway S.L., Glotzer,M., King,R.W. and Murray,A.W. (1993) Anaphase is initiated by proteolysis rather than by the inactivation of maturation-promoting factor. Cell, 73, 1393–1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irniger S., Piatti,S., Michaelis,C. and Nasmyth,K. (1995) Genes involved in sister chromatid separation are needed for B-type cyclin proteolysis in budding yeast. Cell, 81, 269–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jallepalli P.V. and Kelly,T.J. (1996) rum1 and cdc18 link inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinase to the initiation of DNA replication in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genes Dev., 10, 541–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaspersen S.L., Charles,J.F. and Morgan,D.O. (1999) Inhibitory phosphorylation of the APC regulator Hct1 is controlled by the kinase Cdc28 and the phosphatase Cdc14. Curr. Biol., 9, 227–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.H., Lin,D.P., Matsumoto,S., Kitazono,A. and Matsumoto,T. (1998) Fission yeast Slp1: an effector of the Mad2-dependent spindle checkpoint. Science, 279, 1045–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura K., Maekawa,H. and Shimoda,C. (1998) Fission yeast Ste9, a homolog of Hct1/Cdh1 and fizzy-related, is a novel negative regulator of cell cycle progression during G1-phase. Mol. Biol. Cell, 9, 1065–1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer E.R., Gieffers,C., Hölzl,G., Hengstschläger,M. and Peters,J.M. (1998) Activation of the human anaphase promoting complex by proteins of the Cdc20/Fizzy family. Curr. Biol., 8, 1207–1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer E.R., Scheuringer,N., Podtelejnikov,A.V., Mann,M. and Peters,J.-P. (2000) Mitotic regulation of the APC activator proteins CDC20 and CDH1. Mol. Biol. Cell, 11, 1555–1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krek W. (1998) Proteolysis and the G1–S transition: the SCF connection. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev., 8, 36–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorca T., Castro,A., Martinez,A.M., Vigneron,S., Morin,N., Sigrist,S., Lehner,C.F., Doree,M. and Labbé,J.C. (1998) Fizzy is required for activation of the APC cyclosome in Xenopus egg extracts. EMBO J., 17, 3565–3575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukas C., Sørensen,C.S., Kramer,E., Santoni-Rugiu,L., Lindeneg,C., Peters,J.M., Bartek,J. and Lukas,J. (1999) Accumulation of cyclin B1 requires E2F and cyclin-A-dependent rearrangement of the anaphase-promoting complex. Nature, 401, 815–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Castellanos C., Blanco,M.A., de Prada,J.M. and Moreno,S. (2000) The puc1 cyclin regulates the G1 phase of the fission yeast cell cycle in response to cell size. Mol. Cell. Biol., 11, 543–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaelis C., Ciosk,R. and Nasmyth,K. (1997) Cohesins: chromosomal proteins that prevent premature separation of sister chromatids. Cell, 91, 35–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno S. and Nurse,P. (1994) Regulation of progression through the G1 phase of the cell cycle by the rum1+ gene. Nature, 367, 236–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno S., Klar,A. and Nurse,P. (1991) Molecular genetic analysis of fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Methods Enzymol., 194, 795–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan D.O. (1999) Regulation of the APC and the exit from mitosis. Nature Cell Biol., 1, E47–E53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norbury C. and Moreno,S. (1997) Cloning cell cycle regulatory genes by transcomplementation in yeast. Methods Enzymol., 283, 44–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurse P. (1975) Genetic control of cell size at cell division in fission yeast. Nature, 256, 547–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters J.M. (1998) SCF and APC: the Yin and Yang of the cell cycle regulated proteolysis. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol., 10, 759–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfleger C.M. and Kirschner,M.W. (2000) The KEN box: an APC recognition signal distinct from the D box targeted by Cdh1. Genes Dev., 14, 655–665. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinz S., Huang,E.S., Visintin,R. and Amon,A. (1998) The regulation of Cdc20 proteolysis reveals a role for the APC components Cdc23 and Cdc27 during S-phase and early mitosis. Curr. Biol., 8, 750–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sazer S. and Sherwood,S.W. (1990) Mitochondrial growth and DNA synthesis occur in the absence of nuclear DNA replication in fission yeast. J. Cell Sci., 97, 509–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab M., Lutum,A.S. and Seufert,W. (1997) Yeast Hct1 is a regulator of Clb2 cyclin proteolysis. Cell, 90, 683–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigrist S.J. and Lehner,C.F. (1997) Drosophila fizzy-related down regulates mitotic cyclins and is required for cell proliferation arrest and entry into endocycles. Cell, 90, 671–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigrist S.J., Jacobs,H., Stratmann,R., and Lehner,C.F. (1995) Exit from mitosis is regulated by Drosophila Fizzy and the sequential destruction of cyclins A, B and B3. EMBO J., 14, 4827–4838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiozaki K. and Russell,P. (1997) Strees-activated protein kinase pathway in cell cycle control of fission yeast. Methods Enzymol., 283, 506–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirayama M., Toth,A., Galova,M. and Nasmyth,K. (1999) APCCdc20 promotes exit from mitosis by destroying the anaphase inhibitor Pds1 and cyclin Clb5. Nature, 402, 203–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shou W. et al. (1999) Exit from mitosis is triggered by Tem1-dependent release of the protein phosphatase Cdc14 from nucleolar RENT complex. Cell, 97, 233–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern B. and Nurse,P. (1997) Fission yeast pheromone blocks S-phase by inhibiting the G1 cyclin B–p34cdc2 kinase. EMBO J., 16, 534–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern B. and Nurse,P. (1998) Cyclin B proteolysis and the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor rum1p are required for pheromone-induced G1 arrest in fission yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell, 9, 1309–1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlmann F., Lottspeich,F. and Nasmyth,K. (1999) Sister-chromatid separation at anaphase onset is promoted by cleavage of the cohesin subunit Scc1. Nature, 400, 37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visintin R., Prinz,S. and Amon,A. (1997) CDC20 and CDH1: a family of substrate-specific activators of APC dependent proteolysis. Science, 278, 460–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visintin R., Craig,K., Hwang,E.S., Prinz,S., Tyers,M. and Amon,A. (1998) The phosphatase Cdc14 triggers mitotic exit by reversal of Cdk-dependent phosphorylation. Mol. Cell, 2, 709–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visintin R., Hwang,E.S. and Amon,A. (1999) Cfi1 prevents exit from mitosis by anchoring Cdc14 phosphatase in the nucleolus. Nature, 398, 818–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein J., Jacobsen,F.W., Hsu-Chen,J., Wu,T. and Baum,L.G. (1994) A novel mammalian protein, p55CDC, present in dividing cells is associated with protein kinase activity and has homology to the Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell division cycle proteins Cdc20 and Cdc4. Mol. Cell. Biol., 14, 3350–3363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi S., Murakami,H. and Okayama,H. (1997) A WD repeat protein controls the cell cycle and differentiation by negatively regulating cdc2/B-type cyclin complexes. Mol. Biol. Cell, 8, 2475–2486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagida M. (2000) Cell cycle mechanisms of sister chromatid separation; roles of cut1/separin and cut2/securin. Genes Cells, 5, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeong F.M., Lim,H.H., Padmashree,C.G. and Surana,U. (2000) Exit from mitosis in budding yeast: biphasic inactivation of the Cdc28/Clb2 mitotic kinase and the role of Cdc20. Mol. Cell, 5, 501–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacchariae W. and Nasmyth,K. (1999) Whose end is destruction: cell division and the anaphase promoting complex. Genes Dev., 13, 2039–2058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacchariae W., Schwab,M., Nasmyth,K. and Seufert,W. (1998) Control of cyclin ubiquitination by CDK-regulated binding of Hct1 to the anaphase promoting complex. Science, 282, 1721–1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]