Abstract

A fundamental question in developmental biology is how spatial patterns are self-organized from homogeneous structures. In 1952, Turing proposed the reaction-diffusion model in order to explain this issue. Experimental evidence of reaction-diffusion patterns in living organisms was first provided by the pigmentation pattern on the skin of fishes in 1995. However, whether or not this mechanism plays an essential role in developmental events of living organisms remains elusive. Here we show that a reaction-diffusion model can successfully explain the shoot apical meristem (SAM) development of plants. SAM of plants resides in the top of each shoot and consists of a central zone (CZ) and a surrounding peripheral zone (PZ). SAM contains stem cells and continuously produces new organs throughout the lifespan. Molecular genetic studies using Arabidopsis thaliana revealed that the formation and maintenance of the SAM are essentially regulated by the feedback interaction between WUSHCEL (WUS) and CLAVATA (CLV). We developed a mathematical model of the SAM based on a reaction-diffusion dynamics of the WUS-CLV interaction, incorporating cell division and the spatial restriction of the dynamics. Our model explains the various SAM patterns observed in plants, for example, homeostatic control of SAM size in the wild type, enlarged or fasciated SAM in clv mutants, and initiation of ectopic secondary meristems from an initial flattened SAM in wus mutant. In addition, the model is supported by comparing its prediction with the expression pattern of WUS in the wus mutant. Furthermore, the model can account for many experimental results including reorganization processes caused by the CZ ablation and by incision through the meristem center. We thus conclude that the reaction-diffusion dynamics is probably indispensable for the SAM development of plants.

Introduction

A major subject of developmental biology is how stationary patterns are generated from homogeneous fields. In 1952, in order to account for this issue, Turing proposed the reaction-diffusion model in which stable patterns are self-organized by diffusible components interacting with each other [1]. Whereas this Turing model has been extensively studied by mathematical biologists [2]–[4], until recently it has not been widely accepted by experimental biologists. However, following the description in 1995 of a Turing pattern in the skin pigmentation of marine angelfish [5], the Turing model has attracted attention from developmental and molecular biologists. However, as most of morphogenetic events of animals are irreversible, the patterns that we can observe have been completed and are fixed. Therefore, it would be difficult to verify whether or not the reaction-diffusion pattern plays essential roles in morphogenesis processes in animals [6], [7].

The shoot apical meristem (SAM) of plants resides in the top of the shoot and repetitively produces leaves, branches, and flowers. Whereas many morphogenetic events in animals are completed during embryogenesis, SAM continuously forms new organs throughout the lifespan. SAM is spatially restricted to a small area with an almost constant cell population despite active cell division. The SAM consists of a central zone (CZ) and a surrounding peripheral zone (PZ), which are distinct from an outer differentiated region named the organ zone (OZ) [8]. Stem cells in the SAM are located in the outermost cell layers of the CZ region, and are positively controlled by a group of cells, termed the organizing center (OC), located beneath the stem cells. Many genes show variable levels of expression in different zones of the SAM [9]. Molecular genetic studies in Arabidopsis thaliana revealed that many genes are involved in SAM formation and that a feedback interplay between WUSCHEL (WUS) and CLAVATA (CLV) is central to the regulation of the SAM [10]–[13]. Mutation of WUS or CLV results in opposite phenotypes: clv mutants have enlarged meristems and frequently generate fasciated and bifurcated shoots [14]–[16]; wus mutants initially form a flat shoot apex without leaf primordia, in contrast to the dome-shaped structure of the wild type, suggesting that WUS is a positive regulator of SAM [17]. Interestingly, the wus mutant initiates ectopic secondary shoot meristems across the flattened apex, resulting in the formation of a bushy plant with a number of shoots and leaves. It is unclear why and how weakened WUS activity in the SAM leads to the production of so many ectopic meristems. A small peptide derived from CLV3 is perceived as a ligand by the leucine-rich repeat receptor-like kinase CLV1, and possibly by CLV2-CORYNE (CRN) complex and RECEPTOR-LIKE PROTEIN KINASE 2 (RPK2) to restrict WUS expression [18]–[22]. In contrast, the homeodomain transcription factor WUS promotes the CLV3 expression in a non-cell-autonomous manner [19], [24], and also activates its own expression [25], [26].

To date, three mathematical models for the SAM pattern formation using reaction-diffusion system have been proposed based on WUS-CLV dynamics [27]–[29]. These models can explain autonomous pattern formation in the SAM, for example, the expression of WUS is stably established at the meristem center in the wild type, is enlarged by defects of CLV, and is regenerated following CZ ablation. However, these models do not take into account effects of cell division and spatial restrictions of the meristem and, accordingly, cannot explain the derivation of morphological features such as homeostatic control despite cell proliferation in the wild type and drastic morphological changes in clv and wus mutants. Therefore, we developed an alternative mathematical model to describe the mechanism underlying SAM proliferation and patterning by integrating cell division and spatial restrictions of the meristem into the reaction-diffusion dynamics based on WUS-CLV regulation.

Results

Basic Model for SAM Dynamics

We developed as simple a mathematical model as possible because we aimed to understand the essential dynamics that underlie the proliferation and patterning of the SAM in plants. Our SAM model is based on WUS-CLV dynamics and the spatial restrictions of these dynamic interactions.

(I) WUS-CLV dynamics

Pattern formation by a Turing system has been extensively studied, especially

the activator-inhibitor system. In this system, the activator enhances its

own production and also production of the inhibitor, while the inhibitor

represses activator synthesis [2]–[4]. Here,

we modeled WUS-CLV dynamics by reference to the activator-inhibitor system,

because the two systems have very similar regulatory interactions (Fig. 1A). Thus, in our

model, WUS and CLV equate to the activator and inhibitor, respectively. In

more detail, the diffusible peptide CLV3 corresponds to the inhibitor, and

CLV1, CLV2-CRN, and RPK2 are involved in its downstream pathway for

repressing the activator. On the other hand, as it is not known whether WUS

moves between cells, we assume that WUS is involved in the self-activation

pathway of the activator, a hypothetical diffusible molecule distinct from

WUS in the model. It should be noted that the model has two distinct

feedback loops centering on the activator: the positive feedback loop

depending on WUS and the negative feedback loop via CLV signaling (Fig. 1D). The basic

dynamics of the activator ( ) and inhibitor

(

) and inhibitor

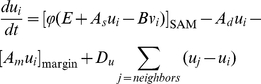

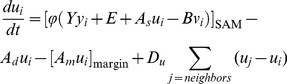

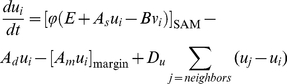

( ) in the i-th cell is described by

the following form of equations:

) in the i-th cell is described by

the following form of equations:

| (1a) |

| (1b) |

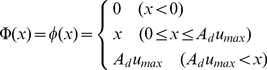

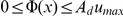

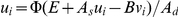

with the constraint condition in the activator synthesis (Fig. 1B),

|

(2a) |

or

|

(2b) |

where

,

,  ,

,

,

,  ,

,

,

,  ,

,

,

,  ,

,

, and

, and  are positive

constants, and

are positive

constants, and  is the

equilibrium value of the activator (

is the

equilibrium value of the activator ( ) in a

simplified form by Equations (3) without space.

) in a

simplified form by Equations (3) without space.

is a sigmoidal function ranged between 0 and

is a sigmoidal function ranged between 0 and

(Fig.

1B). The constraint on the activator synthesis

(Fig.

1B). The constraint on the activator synthesis

results in that on the activator concentration

results in that on the activator concentration

, because the equilibrium condition in Equation (1a)

without space leads to the equation

, because the equilibrium condition in Equation (1a)

without space leads to the equation  . Three terms

of the right hand side of Equation (1a) or (1b) represent the synthesis,

degradation, and diffusion of the activator or inhibitor, respectively. That

is, the activator is induced by itself in the strength

. Three terms

of the right hand side of Equation (1a) or (1b) represent the synthesis,

degradation, and diffusion of the activator or inhibitor, respectively. That

is, the activator is induced by itself in the strength

, is repressed by the inhibitor in the intensity of

, is repressed by the inhibitor in the intensity of

, decays at the rate

, decays at the rate  , and diffuses

between adjacent cells with the diffusion coefficient

, and diffuses

between adjacent cells with the diffusion coefficient

. On the other hand, the inhibitor is induced by the

activator in the strength

. On the other hand, the inhibitor is induced by the

activator in the strength  , decays at the

rate D, and diffuses with the diffusion coefficient

, decays at the

rate D, and diffuses with the diffusion coefficient

. Therefore, the functional strength of WUS is

represented by

. Therefore, the functional strength of WUS is

represented by  in the model,

because the activator and WUS positively regulate each other, in other

words, the activator is self-induced via WUS (Fig. 1A). On the other hand, mutations in

CLV can result in the change of

in the model,

because the activator and WUS positively regulate each other, in other

words, the activator is self-induced via WUS (Fig. 1A). On the other hand, mutations in

CLV can result in the change of

or

or  .

.

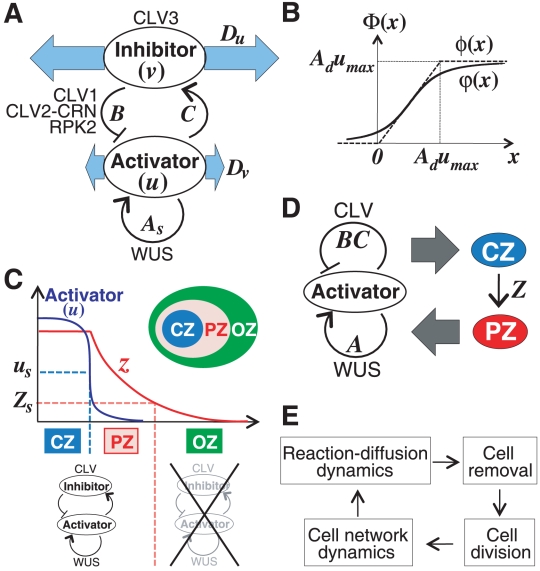

Figure 1. Model framework.

(A) Schematic representation of the WUS-CLV dynamics with respect to

the activator-inhibitor system. (B)  (solid

line, Equation (2a); n = 2.0)

and

(solid

line, Equation (2a); n = 2.0)

and  (dashed line, Equation (2b)) are constraint functions ranged between

0 and

(dashed line, Equation (2b)) are constraint functions ranged between

0 and  . (C)

Schematic representation of a spatially restricted SAM. While

. (C)

Schematic representation of a spatially restricted SAM. While

is the

threshold of the activator (blue line) for the CZ differentiation,

Zs is the threshold of

diffusible molecule z (red line) for the SAM

differentiation. (D) The SAM is regulated by the interaction between

WUS-CLV dynamics at the molecular level and CZ-PZ relationship at

the tissue level. (E) The procedure of numerical calculations is

divided into four steps (for details, see Materials and Methods).

is the

threshold of the activator (blue line) for the CZ differentiation,

Zs is the threshold of

diffusible molecule z (red line) for the SAM

differentiation. (D) The SAM is regulated by the interaction between

WUS-CLV dynamics at the molecular level and CZ-PZ relationship at

the tissue level. (E) The procedure of numerical calculations is

divided into four steps (for details, see Materials and Methods).

We also examined a simplified version written by

| (3a) |

| (3b) |

with the constraint condition of

;

;  if

if

and

and  if

if

. Equation (3a) can be obtained from Equation (1a) by

linearizing the activator synthesis and imposing the constraint condition on

the activator concentration instead of its synthesis. A theoretical analysis

indicates that the positive and negative feedback strengths are associated

with

. Equation (3a) can be obtained from Equation (1a) by

linearizing the activator synthesis and imposing the constraint condition on

the activator concentration instead of its synthesis. A theoretical analysis

indicates that the positive and negative feedback strengths are associated

with  and

and  , respectively,

in this simplified dynamics (Fig. 1D, see Methods S1).

, respectively,

in this simplified dynamics (Fig. 1D, see Methods S1).

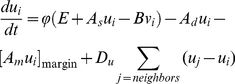

(II) Spatial restrictions on WUS-CLV dynamics

The SAM in plants is usually limited in its size, indicating that there must

be a mechanism for its spatial restriction. In A. thaliana,

the CZ is known to induce formation of the PZ, but the detailed molecular

mechanism is still unclear [11], [30]. In order to incorporate this feature in our

model, we have assumed that a diffusible factor

( ) is present. The CZ is defined as the cells in which

the activator is expressed at levels greater than the threshold

concentration of

) is present. The CZ is defined as the cells in which

the activator is expressed at levels greater than the threshold

concentration of  (Fig. 1C, blue broken

line). In CZ cells, the diffusible factor z is synthesized

at the rate of

(Fig. 1C, blue broken

line). In CZ cells, the diffusible factor z is synthesized

at the rate of  ; diffusion of

the factor generates a gradient (Fig. 1C, red solid line) and induces

formation of the PZ. The PZ and OZ are differentiated by having a

z concentration higher or lower, respectively, than a

fixed threshold value (

; diffusion of

the factor generates a gradient (Fig. 1C, red solid line) and induces

formation of the PZ. The PZ and OZ are differentiated by having a

z concentration higher or lower, respectively, than a

fixed threshold value ( ) (Fig. 1C, red broken line).

Accordingly, parameter

) (Fig. 1C, red broken line).

Accordingly, parameter  represents the

strength of PZ induction (Fig.

1D). The dynamic interaction of WUS and CLV is spatially

restricted to the CZ and PZ and does not occur in the OZ, by limiting the

activator synthesis to the CZ and PZ. Thus, in PZ cells, the activator is

synthesized but remains at very low levels (Fig. 1C). The basic dynamics including

the spatial restriction is described by the following

equations:

represents the

strength of PZ induction (Fig.

1D). The dynamic interaction of WUS and CLV is spatially

restricted to the CZ and PZ and does not occur in the OZ, by limiting the

activator synthesis to the CZ and PZ. Thus, in PZ cells, the activator is

synthesized but remains at very low levels (Fig. 1C). The basic dynamics including

the spatial restriction is described by the following

equations:

| (4a) |

| (4b) |

| (4c) |

with

| (5a) |

| (5b) |

where

,

,  ,

,

,

,  , and

, and

are positive constants. Note that, in this model,

the SAM is controlled by the interaction between two regulations: WUS-CLV

dynamics at the molecular level and CZ-PZ relationship at the tissue level

(Fig. 1D). That is,

WUS-CLV dynamics induces the CZ and subsequent PZ, and in turn the SAM

spatially defines WUS-CLV activity.

are positive constants. Note that, in this model,

the SAM is controlled by the interaction between two regulations: WUS-CLV

dynamics at the molecular level and CZ-PZ relationship at the tissue level

(Fig. 1D). That is,

WUS-CLV dynamics induces the CZ and subsequent PZ, and in turn the SAM

spatially defines WUS-CLV activity.

The numerical simulations were performed by a repeated sequence of all or subsets of the four steps: cell network dynamics, reaction-diffusion dynamics, cell removal, and cell division (Fig. 1E). In the steps of the cell network dynamics and reaction-diffusion dynamics, numerical calculations were carried out until an almost steady state. Detailed conditions and parameter values of each numerical analysis are described in Material and Methods, Methods S1, and Table S1.

Effect of Expressional Separation Between WUS and CLV3

The expression pattern of WUS-CLV dynamics is spatially regulated in a

two-dimensional manner, because its expression domain changes drastically in the

lateral direction by defects in the dynamics but does not longitudinally across

cell layers [18]–[20], [23], [30]. We therefore modeled SAM pattern formation in

two-dimensional space. CLV3 is, however, exclusively expressed

in the outermost cell layers, while WUS is expressed in the

underlying layers [10]–[13], [18], [24]. We examined the effect of this expressional

separation using a simplified two-layered cell network. This analysis indicated

that while stable patterns develop in the absence of any expressional

restrictions (Fig. S1A), they are completely disrupted by introducing expressional

separation in which the activator and inhibitor are synthesized only in the

lower or upper layers, respectively (Fig. S1B). We presume that this disappearance

of patterning results from the retardation of signal transition from the

activator to the inhibitor, because activator synthesized in the lower layer

cannot induce the inhibitor until after reaching the upper layer. In fact,

stable patterns are restored by adding another diffusible factor

( ) into the signaling pathway from the activator to

inhibitor (Fig.

S1C). Furthermore, the patterns depended on the diffusion coefficient

of this factor (Fig. S1D). That is, pattern restoration requires that the diffusion

coefficient of

) into the signaling pathway from the activator to

inhibitor (Fig.

S1C). Furthermore, the patterns depended on the diffusion coefficient

of this factor (Fig. S1D). That is, pattern restoration requires that the diffusion

coefficient of  (

( ) is sufficiently larger than that of the activator

(

) is sufficiently larger than that of the activator

( ) (Fig. S1D). This evidence suggests that the

CLV3 induction pathway involves an unknown diffusible

signal molecule other than the activator. These results indicate that pattern

formation caused by WUS-CLV dynamics in the SAM is essentially governed by the

activator-inhibitor mechanism. Therefore, for simplification, we performed the

numerical analyses described below using a conventional activator-inhibitor

system in Fig. 1A, with

single-layered cell networks.

) (Fig. S1D). This evidence suggests that the

CLV3 induction pathway involves an unknown diffusible

signal molecule other than the activator. These results indicate that pattern

formation caused by WUS-CLV dynamics in the SAM is essentially governed by the

activator-inhibitor mechanism. Therefore, for simplification, we performed the

numerical analyses described below using a conventional activator-inhibitor

system in Fig. 1A, with

single-layered cell networks.

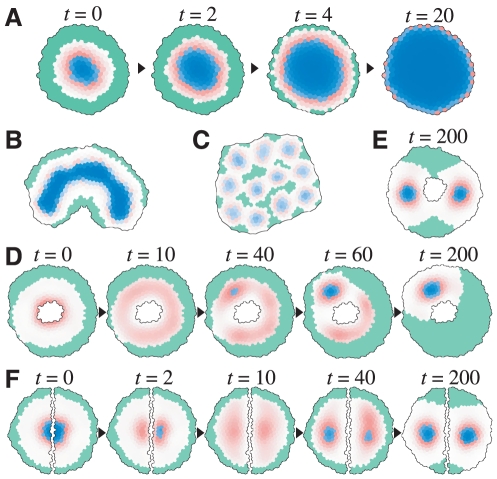

Stem Cell Proliferation Mode

(I) Pattern evolution caused by area expansion

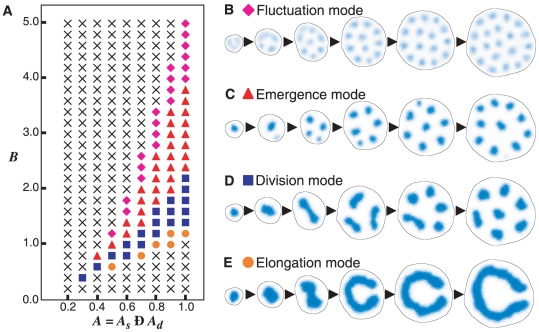

Since the SAM has the potential for continuous growth due to active cell division, we first investigated the effect of cell division in the absence of any spatial restrictions. This analysis showed that pattern evolution could be classified into four modes:

Elongation mode: an initial spot with high activator concentrations continues to elongate to form stripes as the meristem grows (Fig. 2E and Movie S4).

Division mode: spots continue to multiply by binary fission after their elongation (Fig. 2D and Movie S3).

Emergence mode: spots multiply by the appearance of new spots from areas free of these (Fig. 2C and Movie S2). These three modes generate stable patterns with strong expression of the activator.

Fluctuation mode: spots with weak activator levels continuously move and also elongate, increase by division, and merge with neighboring spots (Fig. 2B and Movie S1).

Figure 2. Stem cell proliferation modes.

(A) The proliferation mode clearly depends on parameters

and

and

.

(B–E) Pattern evolution of the reaction-diffusion system in

relation to cell division is classified into four proliferation

groups: the fluctuation mode (B), emergence mode (C), division mode

(D), and elongation mode (E). See also Movies

S1, S2, S3, S4 (B–E, respectively). The

intensity of the blue indicates the activator concentration

(B–E).

.

(B–E) Pattern evolution of the reaction-diffusion system in

relation to cell division is classified into four proliferation

groups: the fluctuation mode (B), emergence mode (C), division mode

(D), and elongation mode (E). See also Movies

S1, S2, S3, S4 (B–E, respectively). The

intensity of the blue indicates the activator concentration

(B–E).

These proliferation patterns during area expansion are similar to those

identified in previous numerical studies [4], [31], [32].

Since the region with high activator concentrations corresponds to the CZ or

the stem cells, the proliferation mode represents the growth pattern of stem

cells in the absence of spatial restrictions. The proliferation mode is

affected by the dynamic balance between the positive and negative feedback

loops. Thus, the mode shifts sequentially from elongation, to division, then

to emergence, and finally to the fluctuation mode as the negative feedback

increases in strength compared with the positive feedback by decreasing

or increasing

or increasing  (Fig. 2A). The effect of

(Fig. 2A). The effect of

on the proliferation mode is the same as that of

on the proliferation mode is the same as that of

(compare with Fig.

S2). This fact is consistent with a theoretical analysis (see Methods

S1). In addition, a similar effect on the proliferation mode is

obtained in the simplified dynamics expressed by Equations (3) (Fig.

S3). This result indicates that the proliferation mode is not

qualitatively affected by the nonlinearity of the dynamics.

(compare with Fig.

S2). This fact is consistent with a theoretical analysis (see Methods

S1). In addition, a similar effect on the proliferation mode is

obtained in the simplified dynamics expressed by Equations (3) (Fig.

S3). This result indicates that the proliferation mode is not

qualitatively affected by the nonlinearity of the dynamics.

(II) Effect of constraint condition of the dynamics

It is known that the constraint condition has a crucial effect on pattern formation in reaction-diffusion systems. For example, while the activator-inhibitor system can generate spotted, striped, or reverse spotted patterns on a fixed two-dimensional plane [2]–[4], [33], these patterns are responsive to the ratio of distances from the equilibrium to the upper and lower limitations of the activator [33]. That is, the spotted pattern, the reverse spotted pattern, and the striped pattern are generated when the equilibrium is closer to the lower limitation, or closer to the upper limitation, or equally distant from the both limitations, respectively.

Our model dynamics explicitly includes the constraint condition of the

activator, and it is shown that this constraint has crucial effects on the

proliferation mode during cell division (Fig.

S4A). When the equilibrium of the activator is situated at the

exact middle between the upper and lower limitations (Fig.

S4A,  ), regions with

high and low activator concentrations cover almost equivalent areas,

resulting in the stripe mode (Fig. S4B). As the upper limitation

becomes high by increasing

), regions with

high and low activator concentrations cover almost equivalent areas,

resulting in the stripe mode (Fig. S4B). As the upper limitation

becomes high by increasing  , the region

with high concentrations becomes small compared to that with low

concentrations, and accordingly becomes to generate spots rather than

stripes. Resultantly the pattern shifts to the elongation mode, division

mode, fluctuation mode, and emergence mode (Fig.

S4A,

, the region

with high concentrations becomes small compared to that with low

concentrations, and accordingly becomes to generate spots rather than

stripes. Resultantly the pattern shifts to the elongation mode, division

mode, fluctuation mode, and emergence mode (Fig.

S4A,  ). In contrast,

as the upper limitation becomes low by decreasing

). In contrast,

as the upper limitation becomes low by decreasing

, the pattern shifts to the reverse elongation mode

(Fig.

S4C), reverse division mode (Fig.

S4D), reverse fluctuation mode (Fig.

S4E), and reverse emergence mode (Fig.

S4F). In these cases, spots with low concentrations grow

according to each proliferation mode. The SAM of plants probably has the

condition that can generate the spotted pattern, because the expression of

WUS-CLV system usually results in a spot-like appearance. Therefore, we used

a large value of

, the pattern shifts to the reverse elongation mode

(Fig.

S4C), reverse division mode (Fig.

S4D), reverse fluctuation mode (Fig.

S4E), and reverse emergence mode (Fig.

S4F). In these cases, spots with low concentrations grow

according to each proliferation mode. The SAM of plants probably has the

condition that can generate the spotted pattern, because the expression of

WUS-CLV system usually results in a spot-like appearance. Therefore, we used

a large value of  in the

numerical simulations in this article.

in the

numerical simulations in this article.

SAM Patterns Generated by the Model

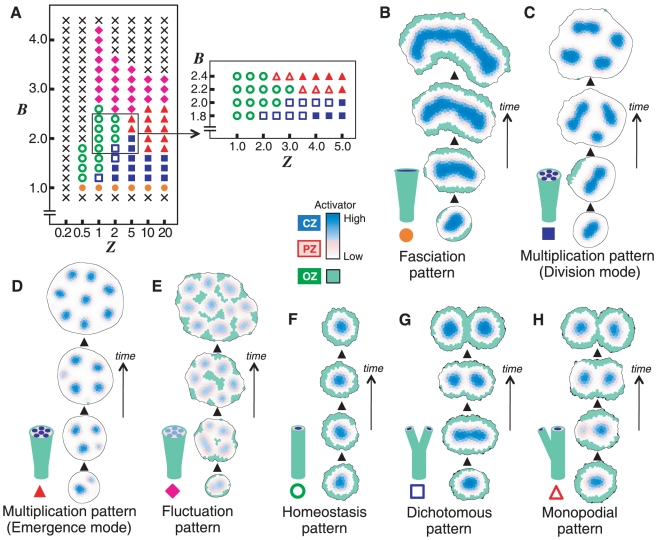

The SAM in plants usually does not proliferate indefinitely but is strongly limited to a small area. Accordingly, we investigated the effect of spatial restriction. In this analysis, the SAM patterns that developed from an initial CZ spot are divided into six groups according to their structure and proliferation (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. SAM patterns generated by the model.

(A) The model generates different SAM patterns by varying

(WUS-CLV

dynamics) and

(WUS-CLV

dynamics) and  (the

spatial restriction). Crosses indicate situations where no patterns are

generated. (B–H) SAM patterns can be divided into six groups

according to their structure and proliferation mode. See also Movies

S5, S6, S7,

S8, S9, S10, S11 (B–H, respectively). Blue

and red indicate the activator concentration in the CZ and PZ,

respectively. The green area indicates the OZ.

(the

spatial restriction). Crosses indicate situations where no patterns are

generated. (B–H) SAM patterns can be divided into six groups

according to their structure and proliferation mode. See also Movies

S5, S6, S7,

S8, S9, S10, S11 (B–H, respectively). Blue

and red indicate the activator concentration in the CZ and PZ,

respectively. The green area indicates the OZ.

(I) Runaway proliferation

When there is strong induction of the PZ due to a large Z component, the resulting patterns of proliferation produce an enlarged SAM with spots or stripes of the CZ. (i) The fasciation pattern produces an enlarged SAM with a strikingly elongated CZ by the elongation mode (Fig. 3B and Movies S5). (ii) The multiplication pattern generates multiple CZ spots by the division mode (Fig. 3C and Movie S6) or by the emergence mode (Fig. 3D and Movie S7). (iii) The fluctuation pattern forms multiple weak CZ spots that proliferate by the fluctuation mode (Fig. 3E and Movie S8). In these patterns, runaway proliferation of stem cells is caused by a chain reaction between PZ expansion and CZ growth.

(II) SAM breakdown

In contrast to runaway proliferation, when there is weak PZ induction due to

a small Z, the PZ area induced by the CZ is too small to

maintain the CZ cells, leading to the disappearance of the CZ and subsequent

breakdown of the SAM (Fig.

3A,  ).

).

(III) Homeostasis pattern

Under the intermediate condition between runaway proliferation and SAM breakdown, (iv) a homeostasis pattern appears in which the SAM keeps an almost constant cell population with a single CZ spot at its center (Fig. 3F and Movie S9). This results from a balance between cell multiplication by division and cell loss from the SAM. In other words, through the homeostasis pattern, the plant prevents runaway proliferation of the stem cells by constricting the size of the meristem. We named this effect “stem cell containment”. Whether or not containment occurs will depend on the proliferation mode: containment readily occurs in the division and emergence modes, but is difficult in the elongation and fluctuation modes (Fig. 3A).

(IV) Branching-related patterns

The intermediate condition between the homeostasis pattern and runaway proliferation produces patterns related to shoot branching, in which each CZ spot develops into a separate independent SAM (Fig. 3A). These patterns fall into two classes according to their proliferation mode: (v) dichotomous pattern by the division mode (Fig. 3G and Movie S10) and (vi) monopodial pattern by the emergence mode (Fig. 3H and Movie S11). The two patterns respectively resemble dichotomous branching and monopodial branching in plant shoots.

(V) Effect of relative frequency of cell division between CZ, PZ, and OZ

It is known that cell division rate in the SAM is distinct between the CZ and PZ, that is, the PZ shows a more rapid rate of cell division than the CZ [34], [35]. Thus we investigated the effect of relative frequency of cell division on the SAM pattern formation. A variety of relative frequencies does not affect the homeostasis pattern formation, with the exception that extremely high division rates in the PZ compared to the CZ generate the dichotomous pattern (Fig. S5). This result suggests that spatial heterogeneity of cell division activity does not have a large effect on the SAM patterning.

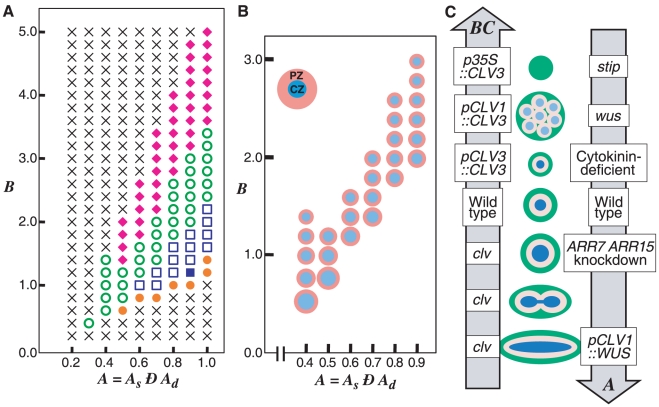

Regulation of SAM Patterns in Plants

SAM patterning with regard to the WUS and CLV

genes (which are associated with  and

and

, respectively, in our model) has been intensively

studied in A. thaliana

[10]–[13]. Thus, the effect of

, respectively, in our model) has been intensively

studied in A. thaliana

[10]–[13]. Thus, the effect of  ,

,

and

and  was investigated

in detail under an intermediate containment condition that induces the

homeostasis pattern. As

was investigated

in detail under an intermediate containment condition that induces the

homeostasis pattern. As  increases or

increases or

is reduced, the SAM pattern shifts from SAM breakdown,

to the fluctuation pattern, then to the homeostasis pattern, then to the

dichotomous pattern and finally to the fasciation pattern (Fig. 4A and Fig. S6).

That is,

is reduced, the SAM pattern shifts from SAM breakdown,

to the fluctuation pattern, then to the homeostasis pattern, then to the

dichotomous pattern and finally to the fasciation pattern (Fig. 4A and Fig. S6).

That is,  and

and  parameters have

opposite effects (Fig.

4C).

parameters have

opposite effects (Fig.

4C).

Figure 4. Effect of WUS and CLV on SAM patterning.

(A) As  increases or

increases or  decreases,

the SAM pattern shifts sequentially from the fluctuation pattern (filled

diamonds), to the homeostasis pattern (open circles), then to the

dichotomous pattern (open squares), and finally to the fasciation

pattern (filled circles). Crosses indicate situations where no patterns

are generated, and filled square indicates the multiplication pattern by

the division mode. (B) The SAM area in the homeostasis pattern expands

as

decreases,

the SAM pattern shifts sequentially from the fluctuation pattern (filled

diamonds), to the homeostasis pattern (open circles), then to the

dichotomous pattern (open squares), and finally to the fasciation

pattern (filled circles). Crosses indicate situations where no patterns

are generated, and filled square indicates the multiplication pattern by

the division mode. (B) The SAM area in the homeostasis pattern expands

as  increases or

increases or  decreases.

The blue and red areas indicate the relative sizes of the CZ and PZ,

respectively. (C) The effect of

decreases.

The blue and red areas indicate the relative sizes of the CZ and PZ,

respectively. (C) The effect of  and

and

on the SAM

patterning is summarized schematically. The predictions of our model

agree with many experimental results (for details, see text). The blue,

red, and green areas indicate the CZ, PZ, and OZ, respectively.

on the SAM

patterning is summarized schematically. The predictions of our model

agree with many experimental results (for details, see text). The blue,

red, and green areas indicate the CZ, PZ, and OZ, respectively.

(I) Wild type

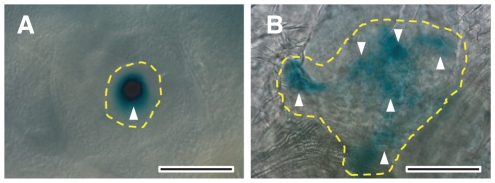

It is evident that development of the wild type is morphologically related to the homeostasis pattern because the both keep a constant SAM size despite active cell division. In order to prove this relationship, we examined the expression pattern of a pWUS::GUS reporter that reflected the activity of the activator. As has been reported in many studies [19]–[26], strong expression of the reporter is detected as a single spot at the center of the SAM (Fig. 5A). This finding confirms that the wild-type SAM of A. thaliana corresponds to the homeostasis pattern of our model (Fig. 4C).

Figure 5. Expression patterns of the pWUS::GUS reporter construct.

Top view of the SAM in wild type Ler (A) and wus-1 (B) plants. Wild-type plants show strong β-glucuronidase (GUS) activity as a single spot at the center of the SAM (A, arrowhead). In contrast, wus-1 plants have an enlarged SAM with multiple foci of expression at very weak levels (B, arrowheads). Ten-day-old seedlings were stained with GUS overnight. The broken lines indicate the extent of the SAM. Scale bars, 10 µm.

(II) SAM size

SAM size in the homeostasis pattern can be expanded by increasing

or decreasing

or decreasing  (Fig. 4B). It is generally

believed that the SAM size in plants is controlled by two separate effects:

first, the CZ restricts its own domain by preventing transition of PZ cells

into the CZ; in addition, the CZ restricts overall SAM size by preventing

differentiation of PZ cells into OZ [11], [30]. The former effect is

obviously derived from the property that Turing pattern has its intrinsic

spatial scale (Methods S1) [4]. On the other hand, the

latter is rather related to stem cell containment, namely, PZ induction. The

cooperation of the two effects determines overall SAM size.

(Fig. 4B). It is generally

believed that the SAM size in plants is controlled by two separate effects:

first, the CZ restricts its own domain by preventing transition of PZ cells

into the CZ; in addition, the CZ restricts overall SAM size by preventing

differentiation of PZ cells into OZ [11], [30]. The former effect is

obviously derived from the property that Turing pattern has its intrinsic

spatial scale (Methods S1) [4]. On the other hand, the

latter is rather related to stem cell containment, namely, PZ induction. The

cooperation of the two effects determines overall SAM size.

(III) wus mutant

The model predicts that a decrease in parameter

will change the wild-type homeostasis pattern to the

fluctuation pattern or SAM breakdown (Fig. 4C). This prediction is supported by

the similar morphological features of the wus mutant and

the fluctuation pattern, namely, an enlarged SAM and secondary meristems

initiated ectopically across the SAM (Fig. 3E) [17]. Furthermore, because

expression pattern of WUS in wus mutant

has not been investigated in detail, we examined in a null allele

wus-1. We found that the expression pattern of a

pWUS::GUS reporter in the wus-1 mutant

showed a patchy pattern at very weak levels compared to the wild type (Fig. 5B). These

morphological and expressional similarities confirm the relationship between

the wus mutant and the fluctuation pattern.

will change the wild-type homeostasis pattern to the

fluctuation pattern or SAM breakdown (Fig. 4C). This prediction is supported by

the similar morphological features of the wus mutant and

the fluctuation pattern, namely, an enlarged SAM and secondary meristems

initiated ectopically across the SAM (Fig. 3E) [17]. Furthermore, because

expression pattern of WUS in wus mutant

has not been investigated in detail, we examined in a null allele

wus-1. We found that the expression pattern of a

pWUS::GUS reporter in the wus-1 mutant

showed a patchy pattern at very weak levels compared to the wild type (Fig. 5B). These

morphological and expressional similarities confirm the relationship between

the wus mutant and the fluctuation pattern.

(IV) stip mutant

Mutation of STIP (also known as WOX9), which encodes a WUS homolog, produces a phenotype that is similar to but more severe than strong wus mutants [36]. That is, secondary shoots are never formed due to failure of growth of the vegetative SAM in the stip mutant. In addition, the SAM of stip lacks WUS expression. This indicates that a drastic reduction in the positive feedback causes the elimination of WUS expression and subsequent SAM breakdown in stip.

(V) WUS overexpression

Our model predicts that an intensified positive feedback will lead to the dichotomous or fasciation pattern (Fig. 4C). An enlarged fasciated SAM, similar to that of the clv mutant, is caused by strong ectopic expression of WUS under the CLV1 promoter in the OC and the surrounding region [19], [23]. This morphological defect can be generated by numerical simulations using similar conditions (Figs. 6B and Fig. S7A).

Figure 6. Numerical simulations for experiments affecting SAM patterning.

(A) Conditional knockdown of CLV3 causes a gradual expansion of the CZ area. (B–C) Ectopic expression of pCLV1::WUS (B) or pCLV1::CLV3 (C) causes clv-like and wus-like SAM morphologies, respectively. (D–E) CZ spots reform after ablation of the CZ cells. CZ foci reform as either a single (D) or two spots (E). (F) As a result of the incision through the meristem center, the two halves reorganize into two new meristems. See also Fig. S2A (B), S2B (C), and Movies S12, S13, S14, S15 (A, D, E and F, respectively). Blue and red indicate the activator concentration in the CZ and PZ, respectively. The green area indicates the OZ.

(VI) Cytokinin effect

The plant hormone cytokinin stimulates the positive feedback pathway

involving WUS, and thereby causes expansion of the

WUS expression domain [26]. Knockdown of the

ARR7 and ARR15 genes, negative

regulators of cytokinin signaling, causes both increase of

WUS expression and enlarged meristems [37]. On the

other hand, SAM size is diminished by decreasing cytokinin levels [38], [39] and

by defects in its signal transduction [40], [41]. In addition,

WUS expression is also reduced by the defect of AHK2, a

cytokinin receptor [26]. These experimental results are consistent with

the outcome of changing parameter  in the model

(Fig. 4C). The

relatively weak effects of cytokinin compared to those of

wus mutation suggest that cytokinin has a limited

involvement in the feedback regulation.

in the model

(Fig. 4C). The

relatively weak effects of cytokinin compared to those of

wus mutation suggest that cytokinin has a limited

involvement in the feedback regulation.

(VII) clv mutants

Defects in clv cause morphological abnormalities such as

enlarged, fasciated, or bifurcated SAMs [14]–[16]. In

addition, these structural changes are correlated strongly with the

expression pattern of WUS. That is, WUS

expression is expanded in enlarged SAMs and is elongated in fasciated SAMs

[19],

[20],

[26].

These results also agree with the predictions of the model as

CLV defects cause a reduction in parameter

(Fig.

4C).

(Fig.

4C).

(VIII) CLV3 knockdown

The conditional knockdown of CLV3 results in a gradual expansion of the pCLV3::GFP expression area [30]. This observation is consistent with the expectations of our model (Fig. 6A and Movie S12).

(IX) CLV3 overexpression

Reinforcement of the negative feedback is expected to produce a diminished homeostatic SAM, or the fluctuation pattern, or SAM breakdown (Fig. 4C). The introduction of multiple copies of CLV3, under its own promoter, reduces both the WUS-expressing domain and SAM size [23]. The relatively weak effect in this case may be due to buffering by the WUS-CLV system [23]. In addition, ectopic expression of CLV3 under the CLV1 promoter resulted in a wus-like SAM, which is closely associated with the fluctuation pattern [23]. This change in the SAM can also be produced by numerical simulations under similar conditions (Figs. 6C and Fig. S7B). Moreover, the SAM of many p35S::CLV3 transgenic plants ceases to initiate organs after the emergence of the first leaves [20]. This is due to strong inhibition against the activator that precludes pattern formation, resulting in SAM breakdown.

(X) pt mutant

The mutant defective in PT (also known as AMP1, COP2, and HPT) forms an enlarged SAM with discrete spots of CLV3 expression and a subsequent excess of shoots [42], [43]. These results strongly indicate that pt is related to the multiplication pattern in the model.

(XI) Meristem reorganization

In tomato, the CZ can be regenerated following laser ablation of CZ cells [44]. Our model can also produce this regeneration process (Fig. 6DE and Movies S13, S14). After CZ ablation, the activator is transiently induced in a ring-shaped region of the PZ (Fig. 6D, t = 10). Then, the high activator region is gradually restricted to a few spots (Fig. 6D, t = 40), each of which develops a stable CZ spot if the activator level exceeds the threshold for CZ (Fig. 6D, t = 100). This modeled regeneration process is similar to that observed in the ablation experiments [44].

In addition, the incision through the meristem center by laser ablation causes reorganization into two new meristems in tomato [45]. This experimental observation is also consistent with a model prediction (Fig. 6F and Movie S15). That is, after the incision, the activator expression is transiently reduced and dispersed (Fig. 6F, t = 10), but is then gradually reorganized at the center of each meristem half (Fig. 6F, t = 40). Finally, stable CZ spots are regenerated (Fig. 6F, t = 200).

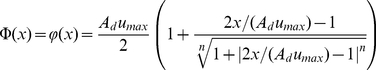

Discussion

We show here that SAM patterning is essentially governed by only two parameters: the proliferation mode and stem cell containment (Fig. 7). The proliferation mode is defined by the dynamics of a molecular network, such as WUS-CLV interaction in A. thaliana. We also show that the proliferation mode has only four groups, and this is a common property of Turing systems [4], [31], [32]. Accordingly, the summary of our results in Fig. 7 is applicable not only to A. thaliana but also to all other plant species. However, since the dynamics of each regulatory network may favor particular proliferation modes, it is likely that each plant species also show preferred patterns. On the other hand, stem cell containment is achieved through a spatial restriction mechanism. Under conditions of overly strong containment, a plant will die because of SAM breakdown; however, with weak containment, the plant loses control over the SAM resulting in excessive shoots. By contrast, under intermediate containment conditions, a plant can control the cell populations in the SAM. It is likely that this homeostasis pattern is present in most plant species including A. thaliana. This result also provides an insight into why and how most plant species have a main shoot axis with a constant diameter.

Figure 7. Model for SAM patterning.

SAM pattern essentially depends on the proliferation mode and stem cell containment strength. The proliferation mode can be sub-divided into four groups, depending on the molecular dynamics regulating the SAM, such as WUS-CLV dynamics of A. thaliana. On the other hand, stem cell containment is associated with the spatial restriction of the dynamics. The blue, red and green areas indicate the CZ, PZ and OZ, respectively.

The branching of plant shoots is classified into two types: dichotomous or monopodial. Dichotomous branching, as is observed in Psilotum, appears to be the equivalent of the dichotomous pattern in our model. In contrast, it is likely that the lateral branches observed in many plant species are not associated with the monopodial pattern but rather are controlled by the distinct dynamics of auxin and its carrier, PIN1, because shoots in the pin1 mutant of A. thaliana elongate normally but fail to generate lateral branches [46]. Our model also provides an insight into how shoot structures of plants has evolved between monopodial shoot axis and dichotomous shoot branching.

For extending the model of this article to explain the pattern of a three-dimensional shoot, it is first required to introduce a three-dimensional cell network system that is capable of cell division. Furthermore, in order to generate the correct three-dimensional pattern of WUS-CLV expression, it seems to need spatial restrictions according to cell layer. As described in the above, spatial expressions of WUS and CLV3 are strongly limited to the outermost cell layers and the underlying layers, respectively. It is likely that these spatial restrictions are not regulated by WUS-CLV dynamics itself but rather depend on an unknown upstream signaling pathway associated with cell layer differentiation. Therefore, these expressional limitations according to cell layer are required for simulating a three-dimensional meristem.

Over half a century ago, Turing first proposed the reaction-diffusion mechanism as the basis for self-organization and pattern formation in biological systems [1]. In several developmental events of animals, candidate molecules that play a central role in pattern formation by the reaction-diffusion mechanism have been proposed [6], [7]. However, it would be difficult to demonstrate reaction-diffusion activity in these cases, because morphogenetic processes in most of them are irreversible and experimental perturbations may be lethal. By contrast, the SAM of plants repetitively produces new organs throughout the lifespan. In order to demonstrate the reaction-diffusion pattern in living systems, it is thought that two lines of evidence are required [6], [7]. One is the identification of elements of interactive networks that fulfill the criteria of short-range positive feedback and long-range negative feedback. By a number of experimental studies, WUS-CLV dynamics clearly satisfies the criteria in the SAM pattern formation [10]–[13]. The other requirement is to show that a reaction-diffusion wave exists, that is, we need to identify dynamic properties of the reaction-diffusion pattern that is predicted by the computer simulation. In the case of the SAM, results of earlier studies suggest that WUS-CLV dynamics satisfies this requirement [27]–[29]. Furthermore, the findings of this article strongly reinforce this argument. Accordingly, it appears that WUS-CLV dynamics fulfills the requirement for demonstrating the reaction-diffusion pattern in the SAM. We thus conclude that the reaction-diffusion mechanism is probably indispensable for the SAM development of plants.

Materials and Methods

GUS Staining Analysis

The pWUS::GUS reporter line [47] was crossed with wus-1/+ heterozygous plants to produce pWUS::GUS+ wus-1/+ F1 plants. pWUS::GUS expression was analyzed in wus-1 homozygotes in the F2 generation. β-glucuronidase (GUS) staining of whole mount SAMs was performed largely as previously described [19], except for use of 10 mM potassium-ferricyanide as the staining buffer. Samples were cleared in 70% ethanol and mounted in chloral hydrate. The expression pattern of pWUS::GUS was analyzed using a Zeiss AxioPlan2 microscope.

Numerical Calculations

The numerical calculations were implemented in C, and the cell network dynamics and reaction-diffusion dynamics were integrated using the Euler method. The graphics of cell networks was made in Mathematica ver.4.2 (Wolfram Research Inc.).

The numerical simulations were performed by a repeated sequence of all or subsets

of the four steps: cell network dynamics, reaction-diffusion dynamics, cell

removal, and cell division (Fig.

1F). In the steps of the cell network dynamics and reaction-diffusion

dynamics, numerical calculations were carried out until an almost steady state.

That is, the step of the cell network dynamics was carried out with the total

time 10.0 and the time step  , while the step of

the reaction-diffusion dynamics was done with the total time

, while the step of

the reaction-diffusion dynamics was done with the total time

and the time step

and the time step  .

.

As the shoot lengthens, cells become increasingly distant to the SAM with

downward move. To accommodate this fact, cells leave the cell networks after

becoming sufficiently distant from the SAM. That is, in the cell removal step,

we remove cells from the cell network if  is lower than a

threshold level,

is lower than a

threshold level,  , that is smaller

than

, that is smaller

than  . In the cell division step, the largest cell divides in

a random direction with the exception of Fig S5.

. In the cell division step, the largest cell divides in

a random direction with the exception of Fig S5.

The initial value of variables was given as their equilibrium with a random fluctuation of 1.0%, and numerical simulations of the reaction-diffusion dynamics were imposed on the boundary condition of zero flux. Steps and parameter values used in each numerical simulation are summarized in Table S1.

Numerical Condition in Figure S1

A two-layered lattice was obtained by the periclinal division of a single-layered lattice with 1,000 cells generated by cell division from an initial lattice with four cells. We examined three spatial restriction conditions by varying activator and inhibitor syntheses. In Fig. S1A, the activator and inhibitor are synthesized in all the cells using Equations (1) and (2a). By contrast, in Fig. S1B, they are synthesized separately in the upper and lower layers with the equations of

| (6a) |

| (6b) |

with

| (7a) |

| (7b) |

In

Fig. S1C and

D, a diffusible molecule  was introduced

into the dynamics of Equations (6); this molecule is active in the signal

transduction pathway from the activator to the inhibitor. Then the set of

differential equations used is given by

was introduced

into the dynamics of Equations (6); this molecule is active in the signal

transduction pathway from the activator to the inhibitor. Then the set of

differential equations used is given by

| (8a) |

| (8b) |

| (8c) |

where  is a constant.

Thus

is a constant.

Thus  is induced by the activator, diffuses with the diffusion

coefficient

is induced by the activator, diffuses with the diffusion

coefficient  , and stimulates the inhibitor.

, and stimulates the inhibitor.

Numerical condition in Figures 2 and S2, S3, S4

Cell number increased from 10 to 1,000 cells without cell removal. We used Equations (1) and (2a) in Fig. 2A and S2, Equations (3) in Fig. S3, and Equations (1) and (2b) in Fig. S4. In Fig. 2B–E, we used the following modified version from Equations (1);

|

(9a) |

| (9b) |

with

| (10) |

where  is a positive

constant. Thus the activator has a higher rate of degradation in marginal cells

than in non-marginal cells, and this condition prevents CZ spots from migrateing

to the edge of the cell network.

is a positive

constant. Thus the activator has a higher rate of degradation in marginal cells

than in non-marginal cells, and this condition prevents CZ spots from migrateing

to the edge of the cell network.

Numerical Condition in Figures 3, 4, and S6

We used the following form modified from Equations (4);

|

(11a) |

| (11b) |

| (11c) |

where positive constant

is introduced in order to prevent CZ spots from

migrating to the edge of the cell network as in the case of Equations (9).

Pattern development by a Turing system requires a minimal area size that depends

on dynamics parameters [4]. Accordingly, in the previous step, the activator is

synthesized in all cells and cell number is increased without cell removal,

until a CZ spot emerges and is maintained stably in the center of the SAM. Then,

the dynamics expressed by Equations (11) was applied until the cell population

reach 1000 cells together with removal cells. The resultant SAM patterns were

subjected to pattern classification. The dominant pattern for each set of

parameter conditions was determined after at least ten independent numerical

simulations.

is introduced in order to prevent CZ spots from

migrating to the edge of the cell network as in the case of Equations (9).

Pattern development by a Turing system requires a minimal area size that depends

on dynamics parameters [4]. Accordingly, in the previous step, the activator is

synthesized in all cells and cell number is increased without cell removal,

until a CZ spot emerges and is maintained stably in the center of the SAM. Then,

the dynamics expressed by Equations (11) was applied until the cell population

reach 1000 cells together with removal cells. The resultant SAM patterns were

subjected to pattern classification. The dominant pattern for each set of

parameter conditions was determined after at least ten independent numerical

simulations.

Numerical Condition in Figure S5

Numerical simulations were carried out as in Fig. 3F except for the cell division step.

Cell division occurs in the cell with the largest value of multiplying its cell

volume by a constant factor;  in CZ,

in CZ,

in PZ, or

in PZ, or  in OZ. Therefore,

the activity of cell division becomes high according to the increase in this

factor. The dominant pattern for each set of parameter conditions was determined

after at least ten independent numerical simulations.

in OZ. Therefore,

the activity of cell division becomes high according to the increase in this

factor. The dominant pattern for each set of parameter conditions was determined

after at least ten independent numerical simulations.

Numerical condition in Figure 6A

The homeostasis pattern was initially generated as in Fig. 3F, and then the synthesis of the inhibitor was interrupted by reducing parameter C to zero.

Numerical Condition in Figures 6BC and S7

CLV1 is strongly expressed in the OC and its surrounding region;

however, the regulatory mechanism of this expression pattern has not yet been

clarified. We, therefore, assumed a diffusible signal molecule

( ) that is induced by the activator, and diffuses at the

rate

) that is induced by the activator, and diffuses at the

rate  to stimulate the CLV1 promoter with an

intensity of

to stimulate the CLV1 promoter with an

intensity of  (see Fig. S7). Consequently, sets of equations

under the condition overexpressed by the CLV1 promoter are

described by

(see Fig. S7). Consequently, sets of equations

under the condition overexpressed by the CLV1 promoter are

described by

|

(12a) |

| (12b) |

| (12c) |

| (12d) |

for pCLV1::WUS (Figs. 6B and S7A) and

|

(13a) |

| (13b) |

| (13c) |

| (13d) |

for pCLV1::CLV3 (Figs. 6C and S7B). The dominant pattern for each set of parameter conditions was determined after at least ten independent numerical simulations.

Numerical Condition in Figure 6D–F

After SAM in the homeostasis state was initially generated as in Fig. 2F, the CZ cells (Fig. 6DE) or a line of cells through the meristem center (Fig 6F) was removed from the cell network. Then the calculations were carried out in the same way as before the cell ablation.

Supporting Information

Effect of expressional separation between the activator and inhibitor in a two-layered cell network. (A) Stable patterns are developed without any spatial restrictions under the Turing condition (inside the dashed lines, see Methods S1). (B) However, stable patterns are completely eliminated by introducing expressional separation in which the activator and inhibitor are synthesized only in the lower and upper cell layers, respectively. (C) In contrast, stable patterns are restored by introducing another diffusible signal molecule (x) into the signaling pathway from the activator to the inhibitor. (D) Pattern restoration requires that the diffusion coefficient of x (Dx) is sufficiently larger than that of the activator (Du = 0.25). Filled circles and crosses indicate stable patterns and no stable patterns, respectively. In A–C, the area enclosed by the dashed lines indicates the Turing condition of Equations (3) (see Methods S1).

(EPS)

Effect of

C

on the

proliferation mode. Parameter  has the same

effect as

has the same

effect as  on the proliferation mode (compare with Fig. 2A).

on the proliferation mode (compare with Fig. 2A).

(EPS)

Effect of a simplified dynamics on the proliferation mode. The simplified activator-inhibitor dynamics described by Equations (3) shows a similar result to that by Equations (1) (compare with Fig. 2A).

(EPS)

Effect of the upper limitation of the activator on the proliferation

mode. (A) Patterns are responsive to the ratio of distances from

the equilibrium of the activator ( ) to the upper

limitation (

) to the upper

limitation ( ) and lower

limitation (

) and lower

limitation ( ). (B–F)

Pattern evolutions of the stripe mode (B, double circles), reverse

fluctuation mode (C, open diamonds), reverse emergence mode (D, open

triangles), reverse division mode (E, open squares), and reverse elongation

mode (F, open circles). Filled diamonds, filled triangles, filled squares,

and filled circles indicate the fluctuation mode, emergence mode, division

mode, and elongation mode, respectively.

). (B–F)

Pattern evolutions of the stripe mode (B, double circles), reverse

fluctuation mode (C, open diamonds), reverse emergence mode (D, open

triangles), reverse division mode (E, open squares), and reverse elongation

mode (F, open circles). Filled diamonds, filled triangles, filled squares,

and filled circles indicate the fluctuation mode, emergence mode, division

mode, and elongation mode, respectively.

(EPS)

Effect of relative frequency of cell division between CZ, PZ, and OZ on

the homeostasis pattern formation. Cell division frequency is

varied by changing parameters  and

and

(for detail see Materials and Methods). Blue, magenta, and green in bar graphs

indicate relative frequency of cell division in CZ, PZ, and OZ,

respectively. Open circles and open squares indicate the homeostasis pattern

and dichotomous pattern, respectively.

(for detail see Materials and Methods). Blue, magenta, and green in bar graphs

indicate relative frequency of cell division in CZ, PZ, and OZ,

respectively. Open circles and open squares indicate the homeostasis pattern

and dichotomous pattern, respectively.

(EPS)

Effect of

C

on SAM pattern

formation.

has the same effect as

has the same effect as

on the SAM pattern formation (compare with Fig. 4A) as in the case of

the proliferation mode.

on the SAM pattern formation (compare with Fig. 4A) as in the case of

the proliferation mode.

(EPS)

Effect of ectopic expression of

WUS

or

CLV3

driven by the

CLV1

promoter. We

assumed a signal molecule ( ) that is

induced by the activator, diffuses with the diffusion coefficient

) that is

induced by the activator, diffuses with the diffusion coefficient

, and stimulates the CLV1 promoter

with the strength

, and stimulates the CLV1 promoter

with the strength  . (A) Ectopic

expression of pCLV1::WUS induces morphological alteration

from the wild-type homeostasis pattern (open circles) to a

clv-like dichotomous (open squares) or fasciation

(filled circles) pattern. (B) On the other hand, ectopic expression of

pCLV1::CLV3 causes the fluctuation pattern (filled

diamonds) that is similar to the phenotype of the wus

mutant. Crosses indicate conditions where no patterns are generated, and

filled square indicates the multiplication pattern by the division mode

proliferation.

. (A) Ectopic

expression of pCLV1::WUS induces morphological alteration

from the wild-type homeostasis pattern (open circles) to a

clv-like dichotomous (open squares) or fasciation

(filled circles) pattern. (B) On the other hand, ectopic expression of

pCLV1::CLV3 causes the fluctuation pattern (filled

diamonds) that is similar to the phenotype of the wus

mutant. Crosses indicate conditions where no patterns are generated, and

filled square indicates the multiplication pattern by the division mode

proliferation.

(EPS)

The steps and parameter values used in the numerical simulations.

(XLS)

Theoretical background of the reaction-diffusion system and numerical condition of the cell network dynamics.

(DOC)

Acknowledgments

We thank T. Laux and Y. Iwasa for providing pWUS::GUS line and critical reading of the manuscript, respectively.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Funding: This work was supported by Grant-in-Aid Science Research on Priority Areas (Grant No. 21027011) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Turing AM. The chemical basis of morphogenesis. Philos Trans R Soc London Ser B. 1952;237:37–72. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2014.0218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meinhardt H. Models of Biological Pattern Formation. London: Academic Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meinhardt H. Algorithmic Beauty of Sea Shells. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murray JD. Mathematical Biology II: Spatial Models and Biomedical Applications. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kondo S, Asai R. A reaction-diffusion wave on the skin of the marine angelfish Pomacanthus. Nature. 1995;376:765–768. doi: 10.1038/376765a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kondo S, Iwashita M, Yamaguchi M. How animals get their skin patterns: fish pigment pattern as a live Turing wave. Int J Dev Biol. 2009;53:851–856. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.072502sk. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kondo S, Miura T. Reaction-diffusion model as a framework for understanding biological pattern formation. Science. 2010;329:1616–1620. doi: 10.1126/science.1179047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clark SE. Organ formation at the vegetative shoot meristem. Plant Cell. 1997;9:1067–1076. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.7.1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yadav RK, Girke T, Pasala S, Xie M, Reddy GV. Gene expression map of the Arabidopsis shoot apical meristem stem cell niche. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:4941–4946. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900843106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sablowski R. The dynamic plant stem cell niches. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2007;10:639–644. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reddy GV. Live-imaging stem-cell homeostasis in the Arabidopsis shoot apex. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2008;11:88–93. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2007.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rieu I, Laux T. Signaling pathways maintaining stem cells at the plant shoot apex. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2009;20:1083–1088. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2009.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stahl Y, Simon R. Plant primary meristems: shared functions and regulatory mechanisms. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2010;13:53–58. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark SE, Running MP, Meyerowitz EM. CLAVATA1, a regulator of meristem and flower development in Arabidopsis. Development. 1993;119:397–418. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.2.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clark SE, Running MP, Meyerowitz EM. CLAVATA3 is a specific regulator of shoot and floral meristem development affecting the same processes as CLAVATA1. Development. 1995;121:2057–2067. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chuang CF, Meyerowitz EM. Specific and heritable genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;25:4985–4990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.060034297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laux T, Mayer KF, Berger J, Jürgens G. The WUSCHEL gene is required for shoot and floral meristem integrity in Arabidopsis. Development. 1996;122:87–96. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fletcher JC, Brand U, Running MP, Simon R, Meyerowitz EM. Signaling of cell fate decisions by CLAVATA3 in Arabidopsis shoot meristems. Science. 1999;283:1911–1914. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5409.1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schoof H, Lenhard M, Haecker A, Mayer KF, Jürgens G, et al. The stem cell population of Arabidopsis shoot meristems is maintained by a regulatory loop between the CLAVATA and WUSCHEL genes. Cell. 2000;100:635–644. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80700-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brand U, Fletcher JC, Hobe M, Meyerowitz EM, Simon R. Dependence of stem cell fate in Arabidopsis on a feedback loop regulated by CLV3 activity. Science. 2000;289:617–619. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5479.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Müller R, Bleckmann A, Simon R. The receptor kinase CORYNE of Arabidopsis transmits the stem cell-limiting signal CLAVATA3 independently of CLAVATA1. Plant Cell. 2008;20:934–946. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.057547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kinoshita A, Betsuyaku S, Osakabe Y, Mizuno S, Nagawa S, et al. RPK2 is an essential receptor-like kinase that transmits the CLV3 signal in Arabidopsis. Development. 2010;137:3911–3920. doi: 10.1242/dev.048199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lenhard M, Laux T. Stem cell homeostasis in the Arabidopsis shoot meristem is regulated by intercellular movement of CLAVATA3 and its sequestration by CLAVATA1. Development. 2003;130:3163–3173. doi: 10.1242/dev.00525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mayer KF, Schoof H, Haecker A, Lenhard M, Jürgens G, et al. Role of WUSCHEL in regulating stem cell fate in the Arabidopsis shoot meristem. Cell. 1998;95:805–815. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81703-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leibfried A, To JP, Busch W, Stehling S, Kehle A, et al. WUSCHEL controls meristem function by direct regulation of cytokinin-inducible response regulators. Nature. 2005;438:1172–1175. doi: 10.1038/nature04270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gordon SP, Chickarmane VS, Ohno C, Meyerowitz EM. Multiple feedback loops through cytokinin signaling control stem cell number within the Arabidopsis shoot meristem. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:16529–16534. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908122106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jönsson H, Heisler M, Reddy GV, Agrawal V, Gor V, et al. Modeling the organization of the WUSCHEL expression domain in the shoot apical meristem. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:Suppl. i232–i240. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nikolaev SV, Penenko AV, Lavreha VV, Mjolsnes ED, Kolchanov NA. A model study of the role of proteins CLV1, CLV2, CLV3, and WUS in regulation of the structure of the shoot apical meristem. Russ J Dev Biol. 2007;38:383–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hohm T, Zitzler E, Simon R. A dynamic model for stem cell homeostasis and patterning in Arabidopsis meristems. PLoS One. 2010;12:e9189. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reddy GV, Meyerowitz EM. Stem-cell homeostasis and growth dynamics can be uncoupled in the Arabidopsis shoot apex. Science. 2005;310:663–667. doi: 10.1126/science.1116261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Madzvamuse A, Wathen AJ, Maini PK. A moving grid finite element method applied to a model biological pattern generator. J Comp Phys. 2003;190:478–500. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holloway DM. The role of chemical dynamics in plant morphogenesis (1). Biochem Soc Trans. 2010;38:645–650. doi: 10.1042/BST0380645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shoji H, Iwasa Y, Kondo S. Stripes, spots, or reversed spots in two-dimensional Turing systems. J Theor Biol. 2003;224:339–350. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5193(03)00170-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steeves TA, Sussex IM. Patterns in Plant Development. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lyndon RF. The Shoot Apical Meristem: Its Growth and Development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu X, Dabi T, Weigel D. Requirement of homeobox gene STIMPY/WOX9 for Arabidopsis meristem growth and maintenance. Curr Biol. 2005;15:436–440. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.12.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao Z, Andersen SU, Ljung K, Dolezal K, Miotk A, et al. Hormonal control of the shoot stem-cell niche. Nature. 2010;465:1089–1092. doi: 10.1038/nature09126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Werner T, Motyka V, Laucou V, Smets R, Van Onckelen H, et al. Cytokinin-deficient transgenic Arabidopsis plants show multiple developmental alterations indicating opposite functions of cytokinins in the regulation of shoot and root meristem activity. Plant Cell. 2003;15:2532–2550. doi: 10.1105/tpc.014928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miyawaki K, Tarkowski P, Matsumoto-Kitano M, Kato T, Sato S, et al. Roles of Arabidopsis ATP/ADP isopentenyltransferases and tRNA isopentenyltransferases in cytokinin biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:16598–16603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603522103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Higuchi M, Pischke MS, Mähönen AP, Miyawaki K, Hashimoto Y, et al. In planta functions of the Arabidopsis cytokinin receptor family. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:8821–8826. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402887101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nishimura C, Ohashi Y, Sato S, Kato T, Tabata S, et al. Histidine kinase homologs that act as cytokinin receptors possess overlapping functions in the regulation of shoot and root growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2004;16:1365–1377. doi: 10.1105/tpc.021477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mordhorst AP, Voerman KJ, Hartog MV, Meijer EA, van Went J, et al. Somatic embryogenesis in Arabidopsis thaliana is facilitated by mutations in genes repressing meristematic cell divisions. Genetics. 1998;149:549–563. doi: 10.1093/genetics/149.2.549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vidaurre DP, Ploense S, Krogan NT, Berleth T. AMP1 and MP antagonistically regulate embryo and meristem development in Arabidopsis. Development. 2007;134:2561–2567. doi: 10.1242/dev.006759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reinhardt D, Frenz M, Mandel T, Kuhlemeier C. Microsurgical and laser ablation analysis of interactions between the zones and layers of the tomato shoot apical meristem. Development. 2003;130:4073–4083. doi: 10.1242/dev.00596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reinhardt D, Frenz M, Mandel T, Kuhlemeier C. Microsurgical and laser ablation analysis of leaf positioning and dorsoventral patterning in tomato. Development. 2005;132:15–26. doi: 10.1242/dev.01544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Okada K, Ueda J, Komaki MK, Bell CJ, Shimura Y. Requirement of the auxin polar transport system in early stages of Arabidopsis floral bud formation. Plant Cell. 1991;3:677–684. doi: 10.1105/tpc.3.7.677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gross-Hardt R, Lenhard M, Laux T. WUSCHEL signaling functions in interregional communication during Arabidopsis ovule development. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1129–1138. doi: 10.1101/gad.225202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Effect of expressional separation between the activator and inhibitor in a two-layered cell network. (A) Stable patterns are developed without any spatial restrictions under the Turing condition (inside the dashed lines, see Methods S1). (B) However, stable patterns are completely eliminated by introducing expressional separation in which the activator and inhibitor are synthesized only in the lower and upper cell layers, respectively. (C) In contrast, stable patterns are restored by introducing another diffusible signal molecule (x) into the signaling pathway from the activator to the inhibitor. (D) Pattern restoration requires that the diffusion coefficient of x (Dx) is sufficiently larger than that of the activator (Du = 0.25). Filled circles and crosses indicate stable patterns and no stable patterns, respectively. In A–C, the area enclosed by the dashed lines indicates the Turing condition of Equations (3) (see Methods S1).

(EPS)

Effect of

C

on the

proliferation mode. Parameter  has the same

effect as

has the same

effect as  on the proliferation mode (compare with Fig. 2A).

on the proliferation mode (compare with Fig. 2A).

(EPS)

Effect of a simplified dynamics on the proliferation mode. The simplified activator-inhibitor dynamics described by Equations (3) shows a similar result to that by Equations (1) (compare with Fig. 2A).

(EPS)

Effect of the upper limitation of the activator on the proliferation

mode. (A) Patterns are responsive to the ratio of distances from

the equilibrium of the activator ( ) to the upper

limitation (

) to the upper

limitation ( ) and lower

limitation (

) and lower

limitation ( ). (B–F)

Pattern evolutions of the stripe mode (B, double circles), reverse

fluctuation mode (C, open diamonds), reverse emergence mode (D, open

triangles), reverse division mode (E, open squares), and reverse elongation

mode (F, open circles). Filled diamonds, filled triangles, filled squares,

and filled circles indicate the fluctuation mode, emergence mode, division

mode, and elongation mode, respectively.

). (B–F)

Pattern evolutions of the stripe mode (B, double circles), reverse

fluctuation mode (C, open diamonds), reverse emergence mode (D, open

triangles), reverse division mode (E, open squares), and reverse elongation

mode (F, open circles). Filled diamonds, filled triangles, filled squares,

and filled circles indicate the fluctuation mode, emergence mode, division

mode, and elongation mode, respectively.

(EPS)

Effect of relative frequency of cell division between CZ, PZ, and OZ on

the homeostasis pattern formation. Cell division frequency is

varied by changing parameters  and

and

(for detail see Materials and Methods). Blue, magenta, and green in bar graphs

indicate relative frequency of cell division in CZ, PZ, and OZ,

respectively. Open circles and open squares indicate the homeostasis pattern

and dichotomous pattern, respectively.

(for detail see Materials and Methods). Blue, magenta, and green in bar graphs

indicate relative frequency of cell division in CZ, PZ, and OZ,

respectively. Open circles and open squares indicate the homeostasis pattern

and dichotomous pattern, respectively.

(EPS)

Effect of

C

on SAM pattern

formation.

has the same effect as

has the same effect as

on the SAM pattern formation (compare with Fig. 4A) as in the case of

the proliferation mode.

on the SAM pattern formation (compare with Fig. 4A) as in the case of

the proliferation mode.

(EPS)

Effect of ectopic expression of

WUS

or

CLV3

driven by the

CLV1

promoter. We

assumed a signal molecule ( ) that is